Abstract

Objective

It has been hypothesised that the use of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) might either increase or reduce the risk of severe or lethal COVID-19. The findings from the available observational studies varied, and summary estimates are urgently needed to elucidate whether these drugs should be suspended during the pandemic, or patients and physicians should be definitely reassured. This meta-analysis of adjusted observational data aimed to summarise the existing evidence on the association between these medications and severe/lethal COVID-19.

Methods

We searched MedLine, Scopus and preprint repositories up to 8 June 2020 to retrieve cohort or case–control studies comparing the risk of severe/fatal COVID-19 (either mechanical ventilation, intensive care unit admission or death), among hypertensive subjects treated with: (1) ACE inhibitors, (2) ARBs and (3) both, versus untreated subjects. Data were combined using a random-effect generic inverse variance approach.

Results

Ten studies, enrolling 9890 hypertensive subjects were included in the analyses. Compared with untreated subjects, those using either ACE inhibitors or ARBs showed a similar risk of severe or lethal COVID-19 (summary OR: 0.90; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.26 for ACE inhibitors; 0.92; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.12 for ARBs). The results did not change when both drugs were considered together, when death was the outcome and excluding the studies with significant, divergent results.

Conclusion

The present meta-analysis strongly supports the recommendation of several scientific societies to continue ARBs or ACE inhibitors for all patients, unless otherwise advised by their physicians who should thus be reassured.

Keywords: cardiac risk factors and prevention, hypertension, meta-analysis

Introduction

With the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic, evidence is rapidly accumulating on the risk factors of severe COVID-19 and death. In the wake of some preliminary, unadjusted reports,1–4 individuals with pre-existing comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases have been identified as those highly vulnerable.5 Notably, such chronic conditions frequently require prescription of ACE inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs).6 Animal studies showed that ACE inhibitors and ARBs upregulate ACE2 expression7 and, as coronaviruses bind their target cells through ACE2, concerns have been expressed that these therapies might facilitate infection with SARS-CoV-2 and increase the risk of severe or fatal COVID-19.6 8 In contrast, it has been suggested that ACE inhibitors and ARBs could benefit infected patients, as ACE2 converts angiotensin II (with known vasoconstrictive, proinflammatory and fibrotic effects) into angiotensin 1–7, which may protect lungs from acute injury, and upregulating ACE2 through therapy may enhance this process.9

In this uncertain scenario, some observational studies with multivariable analyses found no association between use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors and COVID-19 severity,10–16 a few studies found a significant reduction in the risk of death or severe disease17 18 and one study found a increased risk of mechanical ventilation and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).19 The magnitude of the association also varied across studies, which differed for patients’ characteristics, setting (inpatient or outpatient), population targeted by serological testing protocols and extent of measured confounding.

Summary estimates are urgently needed to elucidate whether these drugs, that are prescribed to tens of millions patients worldwide,20 should be suspended during the pandemic, or patients and physicians should be definitely reassured.7 We thus carried out a meta-analysis to summarise the existing evidence from adjusted analyses on the association between RAAS inhibitors and COVID-19.

Methods

Bibliographic search, data extraction and quality assessment

We searched MEDLINE and Scopus databases, up to 11 May 2020, for studies evaluating the risk of severe and/or fatal COVID-19 among ACE inhibitors and/or ARBs users versus non-users. The following search strategy was adopted, without language restrictions: COVID-19 [Title/Abstract] OR Coronavirus [Title/Abstract] OR SARS-CoV-2 [Title/Abstract] AND angiotensin* [Title/Abstract]. The reference lists of reviews and retrieved articles was also screened for additional pertinent papers. In the context of a public health emergency, there is urgency to make research findings available,21 and several relevant clinical data have been shared in public preprint repositories: we thus extended the search to include any relevant manuscript posted in MedRxiv. Inclusion criteria were: (A) cohort or case–control design; (B) laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection status through PCR assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens; (C) available information on underlying comorbidities and pharmacological treatments at the time of COVID-19; and (D) data available to compare COVID-19 severity by RAAS treatment among hypertensive patients. Each included article was independently evaluated by two reviewers (MEF and CAM) who extracted the study characteristics and measures of effect. In case of discrepancies in data extraction, a third author was contacted (LM), and consensus was achieved through discussion.

Individual study quality was assessed using an adapted version of the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale, assessing the comparability across groups for confounding factors, the appropriateness of outcome assessment, length of follow-up and missing data handling and reporting.22

Data analysis

Data were combined using a random-effect generic inverse variance approach23 in order to account for between-study heterogeneity. Missing SEs were computed from 95% CIs following standard Cochrane methodology. If a paper reported the results of different multivariable models, the most stringently controlled estimates (those from the model adjusting for more factors) were extracted. If different models controlled for the same number of covariates, the model containing the most clinically meaningful covariates was used for the analysis.24

Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistic. Potential publication bias was assessed graphically, using funnel plots (displaying the Relative Risks from individual comparisons versus their precision (1/SE). Given that the total number of publications included for each outcome was <10, we could not use formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry: in such cases, the power is too low to distinguish chance from real asymmetry.

The units of the meta-analysis were single comparisons of: (A) ACE inhibitors, (B) ARBs users and (C) both ACE inhibitors and ARBs users, versus non users, in predicting: (1) severe/lethal COVID-19 (presence of either ICU admission, mechanical ventilation or death) and (2) lethal COVID-19. When a study only reported separate estimates for ACE inhibitors or ARBs users, or for the different outcomes included in the definition of severe/lethal COVID-19 (eg, ICU admission and mechanical ventilation separately), the overall estimate of risk was computed from the separate relative risks using the fixed-effect model for generic inverse variance outcomes.24

All meta-analyses were performed using RevMan software, V.5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2019).

Ethics

The informed consent was not required, as the study did not enrol human subjects.

Results

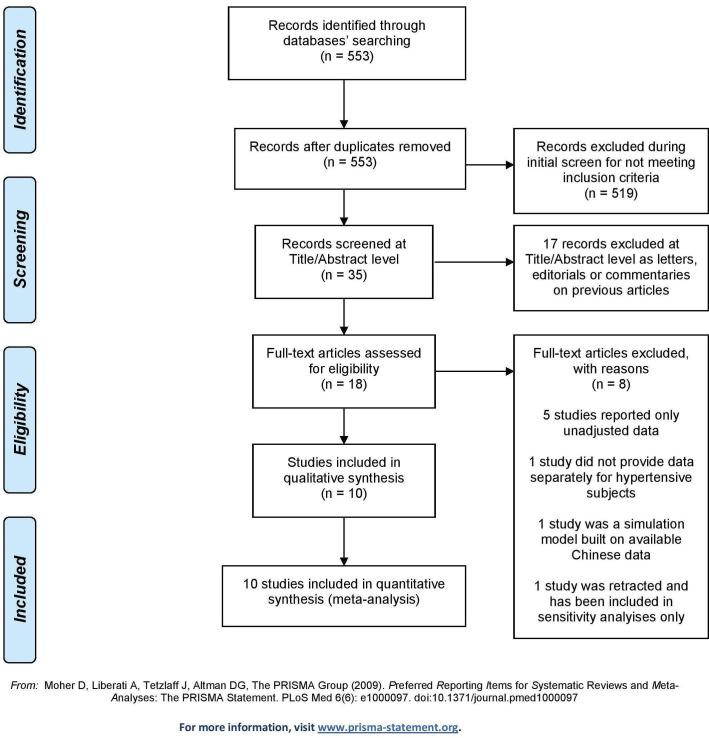

Of the 553 papers initially retrieved, five case–control and five cohort studies were included in the analyses10–19 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 flow diagram. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Overall, the studies included 9890 hypertensive subjects; four studies included only COVID-19 symptomatic patients requiring hospitalisation13 16–18 (table 1). Six studies were carried out in Europe,10–12 14 16 17 two in the USA15 19 and two in China.13 18 The mean age ranged from 58 to 69 years, and the sample size ranged from 20517 to 6272.14

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| N | First author | Journal | Country | Study design | No. of infected patients (with severe/lethal COVID-19) |

No. of hypertensive patients (under ACEi/ARBs) | Mean age (SD) |

% males | Follow -up |

Extracted outcome(s) | Method for adjustment |

| 1 | Bean17 | Submitted (MedRxiv) |

UK | Cohort | 205 (53) | 105 (38) | 63.0 (20.0) | 51.7 | 7 days | Severe/lethal COVID-19 (ICU and death). |

Logistic regression adjusted for age, gender and comorbidities. |

| 2 | Bravi10 | Submitted | Italy | Case–control | 1603 (192) | 543 (450) | 58.0 (20.9) | 47.3 | 24 days | (1) Severe/lethal COVID-19 (mech. ventilation, ICU and death); (2) death. | Logistic regression adjusted for age, gender and comorbidities |

| 3 | de Abajo11 | The Lancet | Spain | Case–control | 1139 (393) * | 6261 (3950)* | 69.1 (15.4) | 61.0 | – | Severe COVID-19 (hospital admission). | Logistic regression adjusted for age, gender, region (matching variables) and comorbidities. |

| 4 | Giorgi Rossi12 | Submitted (MedRxiv) |

Italy | Cohort | 2653 (217) | 430 (108) | 63.2 | 50.1 | 14 days | Death. | Cox proportional hazard analysis adjusted for age, gender and Charlson Index. |

| 5 | Liu13 | Submitted (MedRxiv) |

China | Case-control | 511 (38†) | 78 (22) | 65.2 (10.7) | 55.2 | NR | Severe/lethal COVID-19 (dyspnoea, resp. rate ≥30/min, SaO2 ≤93%, mech. ventilation). |

Logistic regression adjusted for gender and medications. |

| 6 | Mancia14 | NEJM | Italy | Case–control | 6272 (617) | 3586 (1844) | 68.0 (13.0) | 63.2 | – | Severe/lethal COVID-19 (ICU and death), |

Logistic regression adjusted forage, gender and comorbidities. |

| 7 | Mehra‡25 |

NEJM

(Retracted) |

Multicountry | Cohort | 8910 (515) | 2346 (1326) | 49.0 (16.0) | 60.0 | 40 days | Death. | Logistic regression adjusted for age, race, comorbidities and medications. |

| 8 | Mehta19 |

JAMA

Cardiol |

USA | Cohort | 1735 (272) | 682 (202) | 64.0 (14.0) | 58.5 | NR | Severe/lethal COVID-19 (ICU and mech. ventilation). |

Logistic regression adjusted for age, gender and comorbidities. |

| 9 | Reynolds15 | NEJM | USA | Case-control | 5894 (1002) | 2573 (2141) | 64.0 (15.6) | 50.8 | – | Severe/lethal COVID-19 (mech. ventilation, ICU and death). | Analysis propensity score-matched for age, gender, race, BMI, smoke, comorbidities and medications. |

| 10 | Tedeschi16 |

Clin Infect

Dis |

Italy | Cohort | 609 (179) | 311 (175) | 68.0 (18.5) | 68.0 | 6 days | Death. | Cox proportional hazard analysis adjusted for age, gender and comorbidities. |

| 11 | Zhang18 | Circ Res | China | Cohort | 1128 (99) | 1128 (188) | 64.0 (9.0) | 53.3 | 28 days | Death. | Analysis propensity score-matched for age, gender, comorbidities and in-hospital therapy. |

*Cases were COVID-19 patients; controls were SARS-CoV-2 negative subjects extracted from primary healthcare databases: as such, the number of hypertensive subjects includes both cases and controls and is higher than the number of COVID-19 patients.

†Number of patients with severe COVID-19 among only those with hypertension.

‡Included only in sensitivity analyses.

ARBs, Angiotensin receptor blockers; ICU, intensive care unit; mech., mechanical; NR, not reported; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The methodological characteristics of the included studies are summarised in table 2: the selection of the cohort of patients, the ascertainment of the exposure and the evaluation of the comparability of subjects were adequate in all studies, while 8 out of 10 adequately addressed the items pertaining to outcome assessment and follow-up (length and missing data). One study had a high risk of misclassification bias, as the proportions of hypertensive subjects treated with ACE inhibitors (16.4%) or ARBs (13.2%) were particularly low.19

Table 2.

Methodological quality of the included studies according to the Newcastle Ottawa Scale

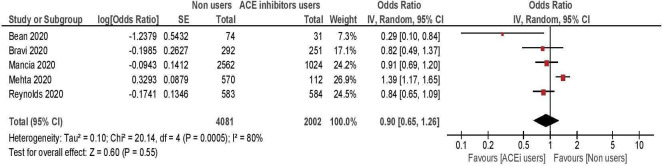

Risk of severe/lethal COVID-19

A total of five studies, enrolling 7489 hypertensive patients, were included in the meta-analysis comparing the risk of severe/lethal COVID-19 between ACE inhibitors users versus non-users10 14 15 17 19 (table 3, figure 2). Overall, the risk of severe or lethal disease was comparable among treated and untreated patients (summary OR: 0.90; 95% CI 0.65 to 1.26). Two studies showed significant results, with opposite direction. The first included 682 hypertensive subjects and showed an increased risk of severe illness among the 112 patients treated with ACE inhibitors.19 The second enrolled 105 hypertensive subjects and reported a lower risk among the 38 treated patients.17 Excluding one or both of these studies did not change the results, which remained non-significant (all p>0.05).

Table 3.

Risk of severe/fatal COVID-19 or death among hypertensive subjects treated with RAAS inhibitors versus untreated subjects, overall and by drug class

| Outcomes | No. of studies (sample) |

Pooled OR (95% CI) |

P value | I2, % |

| 1. Severe/fatal COVID-19* (in users vs non users): | ||||

| ACE inhibitors only10 14 15 17 19 | 5 (7489) | 0.90 (0.65 to 1.26) | 0.6 | 80 |

| ARBs only10 13–15 19 | 5 (7462) | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.12) | 0.4 | 25 |

| ARBs/ACE inhibitors10 11 14 15 19 | 5 (11 334) | 1.00 (0.84 to 1.18) | 0.9 | 50 |

| 2. Death from COVID-19 (in users vs non users): | ||||

| a. Main analysis: | ||||

| ARBs/ACE inhibitors10 12 16 18 | 4 (2412) | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.14) | 0.3 | 24 |

| b. Sensitivity analysis:† | ||||

| ARBs/ACE inhibitors10 12 16 18 25 | 5 (4758) | 0.85 (0.71 to 1.03) | 0.10 | 12 |

All meta-analyses are based on a generic inverse variance approach.

*Including admission into intensive care unit, need for mechanical ventilation or death.

†Including one retracted study.25 26

ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers; RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone.

Figure 2.

Risk of severe/lethal COVID-19 among ACE inhibitors users versus non-users.

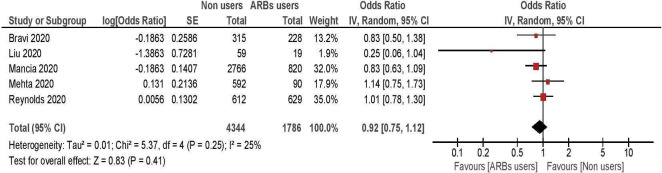

Five studies, enrolling 7462 hypertensive subjects, were included in the meta-analysis comparing the risk of severe illness between ARBs users and non-users10 13–15 19 (table 3, figure 3). All of them showed non-significant differences between treated and untreated patients, with a summary OR of 0.92; 95% CI 0.75 to 1.12.

Figure 3.

Risk of severe/lethal COVID-19 among ARB inhibitors users, versus non-users. ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

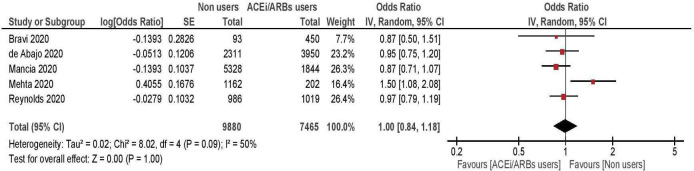

When the above antihypertensive treatments were considered together (five studies, enrolling 11 334 hypertensive patients),10 11 14 15 19 the risk of developing severe COVID-19 was again comparable between treated and untreated patients (summary OR: 1.00; 95% CI 0.84 to 1.18; figure 4).

Figure 4.

Risk of severe/lethal COVID-19 among ACE inhibitors/ARBs users versus non-users. ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

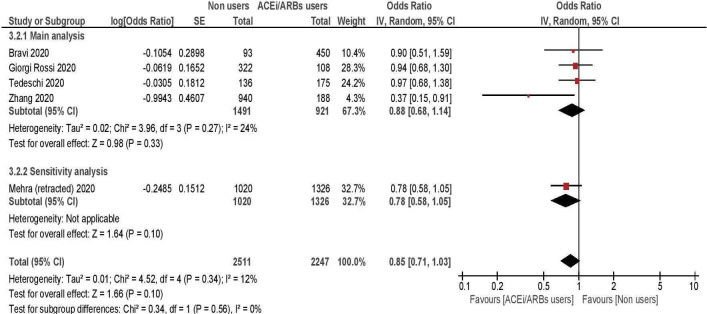

Risk of death from COVID-19

The risk of death among RAAS inhibitors users versus non-users was compared in four studies, including a total of 2412 hypertensive subjects.10 12 16 18 Overall, no differences in risk emerged between the two groups, with a summary OR of 0.88 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.14; table 3, figure 5). A single study from China, enrolling 1128 hospitalised hypertensive patients, showed a significant risk reduction among treated subjects18; when its results were excluded from the analyses, the overall estimates did not change (pooled OR 0.95; 95% CI 0.76 to 1.18). Another study25 assessed the risk of death among ACE inhibitors/ARBs users versus non users and was initially included in the meta-analysis. However, this study was later retracted26; thus, it was excluded from the main analyses and included into a sensitivity analysis: with or without the study, the summary estimate did not change (pooled OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.81 to 1.03).

Figure 5.

Risk of death among ACE inhibitors/ARBs users versus non-users. ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

Discussion

Two main findings emerge from the present meta-analysis, which included the adjusted estimates of 10 observational studies and almost 10 000 hypertensive subjects: first, no significant differences in the risk of developing severe or fatal COVID-19 were observed between the subjects treated with either ACE inhibitors or ARBs, as compared with non-users. Second, and importantly, the results did not change after the exclusion of the three studies, which reported either a significantly higher or lower risk of severe illness among treated patients.

The present findings provide solid evidence from properly adjusted estimates across different countries on the absence of risk from RAAS inhibitors treatment during the pandemic, strongly supporting the statements of several experts27 28 and scientific societies, including the European Medicines Agency,29 the European Society of Cardiology30 and the American Heart Association,31 who recommend continuation of ARBs or ACE inhibitors medication. Although the present findings do not support the hypothesis of a beneficial effect from therapy during the necessary time required for randomised data to come, patients and physicians can be reassured.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the present findings. First, two meta-analyses showed an intermediate-to-high level of heterogeneity. However, a certain degree of heterogeneity across studies was inevitable, given the large variation in terms of setting and baseline patients characteristics. Also, when the analyses were repeated adopting a fixed approach, none of the results substantially differed (except for CIs, which were typically tighter). Second, although all studies (with a single exception)13 provided analyses at least adjusted for age, gender and several underlying comorbidities, some extent of residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out, as for any observational study.32 Third, as shown in the funnel plots in the supplementary online Figures S1-S4, no meta-analysis included more than five studies, thus it was not possible to perform a meaningful evaluation of publication bias. However, given the public health relevance of these data, it is unlikely that non-significant findings—with reassuring implications—have been withheld. Rather, it is certain that large dataset will be available soon. Given the urgency for millions of patients, we decided not to wait, but the present meta-analysis will have to be updated as new adjusted analyses are published. Finally, the risk of selective inclusion bias, due to the presence of multiple effect estimates that can be extracted from individual studies,33 is likely to be low, as only one of the included studies reported more than an adjusted estimate,18 and the results of the meta-analysis including the alternate estimate of effect were unchanged (pooled OR of death 0.88; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.13).

heartjnl-2020-317336supp001.pdf (98.9KB, pdf)

Acknowledging these caveats, the present meta-analysis, based on 10 studies and almost 10 000 hypertensive subjects, did not find any association between COVID-19 severity or mortality and treatment with ARBs, ACE inhibitors or both, strongly supporting the recommendation of several scientific societies to continue ARBs or ACE inhibitors medication for all patients, unless otherwise advised by their physicians, who should thus be reassured.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject?

Some preliminary, unadjusted reports on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 positive subjects showed an increased mortality and morbidity among hypertensive patients, who were frequently treated with ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs). Recently, some observational studies with multivariable analyses found no association between these medications and COVID-19 severity, a few studies found a significant reduction in the risk of death or severe disease and one study found a increased risk of mechanical ventilation and admission to the intensive care unit. The magnitude of the association also varied across studies, which differed for patients’ characteristics, setting (inpatient or outpatient), population targeted by serological testing protocols and extent of measured confounding.

What might this study add?

This meta-analysis is based on 10 adjusted observational studies (enrolling almost 10 000 hypertensive subjects), from different countries, and provides the first summary estimate on the association between ACE inhibitors or ARBs use and COVID-19 severity or mortality. All analyses showed a comparable risk of severe or fatal illness among treated and untreated subjects, either considering ACE inhibitors or ARBs separately, or combined.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Given that ACE inhibitors and ARBs are prescribed to tens of millions patients worldwide, summary estimates were strongly needed to elucidate whether these drugs should be suspended during the pandemic, or patients and physicians should be definitely reassured. These findings strongly support the recommendation of several scientific societies to continue ARBs or ACE inhibitors medication for all patients, unless otherwise advised by their physicians.

Footnotes

MEF and CAM contributed equally.

Contributors: The following authors have contributed to the planning (MEF, CAM, RC, LGM and LaM), conduct (MEF, CAM, FB, GP, RC, AM, RM, LGM) and reporting (MEF, FB, GP, AM, RM, LGM and LM) of the present work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki. As a meta-analysis, the protocol and study did not require the approval from Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. All data are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

- 1. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2020;8:475–81. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guan WJ, ZY N, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA 2020. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities and its effects in coronavirus disease 2019 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020;94:91–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system inhibitors in patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zheng Y-Y, Ma Y-T, Zhang J-Y, et al. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:259–60. 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bavishi C, Maddox TM, Messerli FH. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection and renin angiotensin system blockers. JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bravi F, Flacco ME, Carradori T, et al. Predictors of severe or lethal COVID-19, including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers, in a sample of infected Italian citizens. Plos One 2020;15:e0235248 10.1371/journal.pone.0235248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Abajo FJ, Rodríguez-Martín S, Lerma V, et al. Use of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of COVID-19 requiring admission to hospital: a case-population study. Lancet 2020;395:1705–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giorgi Rossi P, Marino M, Formisano D, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of a cohort of SARS-CoV-2 patients in the province of Reggio Emilia, Italy. MedRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu Y, Huang F, Xu J, et al. Anti-Hypertensive angiotensin II receptor blockers associated to mitigation of disease severity in elderly COVID-19 patients. MedRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mancia G, Rea F, Ludergnani M, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system blockers and the risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:2431–40. 10.1056/NEJMoa2006923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reynolds HR, Adhikari S, Pulgarin C, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone system inhibitors and risk of Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tedeschi S, Giannella M, Bartoletti M, et al. Clinical impact of renin-angiotensin system inhibitors on in-hospital mortality of patients with hypertension hospitalized for COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bean D, Kraljevic Z, Searle T, et al. Treatment with ACE-inhibitors is associated with less severe disease with SARS-Covid-19 infection in a multi-site UK acute Hospital Trust [Unpublished work]. MedRxiv 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang P, Zhu L, Cai J, et al. Association of inpatient use of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with mortality among patients with hypertension hospitalized with COVID-19. Circ Res 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mehta N, Kalra A, Nowacki AS, et al. Association of use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor blockers with testing positive for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO COVID-19 and the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and receptor blockers - Scientific brief. WHO, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carr D. Sharing research data and findings relevant to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak. secondary sharing research data and findings relevant to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, 2020. Available: https://wellcome.ac.uk/coronavirus-covid-19/open-data

- 22. Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. secondary the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses, 2005. Available: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- 23. Manzoli L, Flacco ME, Boccia S, et al. Generic versus brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular diseases. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:351–68. 10.1007/s10654-015-0104-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Manfredini R, Fabbian F, Cappadona R, et al. Daylight saving time and acute myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2019;8. 10.3390/jcm8030404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mehra MR, Desai SS, Kuy S, et al. Cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 26. Mehra MR, Desai SS, Kuy S, et al. Retraction: cardiovascular disease, drug therapy, and mortality in Covid-19 2020. N Engl J Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 27. Kuster GM, Osswald S. Switching antihypertensive therapy in times of COVID-19: why we should wait for the evidence. Eur Heart J 2020;41:1857. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuster GM, Pfister O, Burkard T, et al. SARS-CoV2: should inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin system be withdrawn in patients with COVID-19? Eur Heart J 2020;41:1801–3. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. European Medicines Agency Ema advises continued use of medicines for hypertension, heart or kidney disease during COVID-19 pandemic, 2020. Available: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-advises-continued-use-medicines-hypertension-heart-kidney-disease-during-covid-19-pandemic [Accessed 20 Apr 2020].

- 30. European Society of Cardiology Position statement of the ESC Council on hypertension on ACE-inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers, 2020. Available: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-on-Hypertension-(CHT)/News/position-statement-of-the-esc-council-on-hypertension-on-ace-inhibitors-and-ang [Accessed 20 Apr 2020].

- 31. American Hearth Association Patients taking ACE-i and Arbs who contract COVID-19 should continue treatment, unless otherwise advised by their physician, 2020. Available: https://newsroom.heart.org/news/patients-taking-ace-i-and-arbs-who-contract-covid-19-should-continue-treatment-unless-otherwise-advised-by-their-physician?utm_campaign=sciencenews19-20&utm_source=science-news&utm_medium=phd-link&utm_content=phd03-17-20

- 32. Thomas LE, Bonow RO, Pencina MJ. Understanding observational treatment comparisons in the setting of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol 2020. 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Page MJ, Forbes A, Chau M, et al. Investigation of bias in meta-analyses due to selective inclusion of trial effect estimates: empirical study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011863. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

heartjnl-2020-317336supp001.pdf (98.9KB, pdf)