Abstract

We report the outcome of hematopoietic cell transplantation for 52 patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) transplanted between 2000 and 2017. The median age at transplant was 11 years with a median follow-up of 60 months. Transplant indication was bone marrow failure (BMF; cytopenia or aplastic anemia) in 39 patients and myelodysplasia or acute myeloid leukemia in 13 patients. Eighteen patients received grafts from HLA-matched siblings, 6 from HLA-matched or mismatched relatives and 28 from HLA-matched or mismatched unrelated donors. Preparative regimens for BMF were myeloablative (n=13) and reduced intensity (n=26). Twenty-nine of 39 patients with BMF are alive and the 5-year overall survival was 72% (95% CI; 57–86%). Graft failure and graft-versus-host disease were the predominant causes of death. Preparative regimens for myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia were myeloablative (n=8) and reduced intensity (n=5). Only 2 of 13 patients are alive (15%) and relapse was the predominant cause of death. Survival after transplantation for SDS related BMF is better compared to historical reports but strategies are needed to overcome graft failure and graft-versus-host disease. For SDS related myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia, transplantation does not extend survival. Rigorous surveillance and novel treatments for leukemia are needed urgently.

Introduction

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by bone marrow failure (BMF; cytopenia or aplastic anemia), exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, and skeletal abnormalities, with a predisposition to myelodysplasia (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) (1). Although most individuals with SDS have some hematologic manifestations of their disease, the majority of them do not require transplantation. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), however, remains the only curative therapy for 19–36 % of patients with SDS who develop BMF or transformation to myeloid malignancy. Historically survival after transplantation using a myeloablative preparative regimen for BMF or myeloid malignancy, with an HLA-matched sibling or unrelated donor, is approximately 60% (2, 3). Although many deaths can be explained by recurrent myeloid malignancy deaths were also attributed to cardiac, pulmonary and neurologic toxicity (2–7). Recently, case series reports of transplantation with reduced-intensity preparative regimens have recorded overall survival 67–100% (8–10). Nevertheless, published reports on outcomes after transplantation for SDS are limited. Thus, the current analysis includes 52 patients with SDS transplanted for BMF or myeloid malignancy in the United States between 2000 and 2017.

Methods

Data Source

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research is a voluntary network of transplant centers that report all allogeneic and autologous transplants consecutively. Patients are followed longitudinally until death or loss to follow-up Patients or their legal guardians provided written informed consent for research participation. The Institutional Review Board of the National Marrow Donor Program approved this study.

Patients

Patients who received an allogeneic transplantation for SDS as diagnosed by their treating physician transplanted between 2000 and 2017. Indications for transplantation included BMF, (n=39), and myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia (n=13).

Transplant Conditioning regimen

Regimen intensity was classified as myeloablative or reduced intensity. Myeloablation was defined as busulfan dose >8 mg/kg or melphalan dose >140 mg/m2 or thiotepa dose >10mg/kg or total body irradiation (fractionated) ≥1000 cGy. All other regimens were considered reduced intensity.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was survival, death from any cause was considered an event and surviving patients were censored at last follow-up. Neutrophil recovery was defined as the first of 3 consecutive days with absolute neutrophil count ≥ 0.5 × 109 /L, and platelet recovery, ≥ 20 × 109/L without transfusion for 7 days. Graft failure was defined as failure to achieve neutrophil recovery or decline in neutrophils following initial recovery and without subsequent recovery or a subsequent allogeneic HSCT. Acute and chronic graft versus host disease (GVHD) was established on published criteria (11, 12). When the indication for transplantation was myeloid malignancy, relapse was defined as morphologic, cytogenetic or molecular recurrence of disease.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival probability was calculated using the Kaplan Meier estimator (13). Probability of neutrophil recovery, platelet recovery, acute and chronic GVHD were calculated using the cumulative incidence estimator to accommodate for competing risks (14).

Results:

Bone marrow failure

Thirty-nine patients received transplantation for SDS associated BMF and their characteristics are shown in Table 1. Nineteen of 39 patients (49%) were tested for SDS genetic mutation. Fourteen of 19 (74%) patients were confirmed to have biallelic SDS mutation, 1 patient had a heterozygous mutation and in the remaining 4 patients did not have biallelic mutation. Information on Genetic testing was done for 4 patients and testing information was not available for 16 patients. Their median age at transplantation was 7 years (range 0.4 – 51). 33 patients had performance scores 90–100 and 21 patients had HCT-CI score ≤2. HCT-CI score was not recorded for the 12 transplantations before 2007. Preparative regimens were myeloablative (n=13) and reduced intensity (n=26). Sixteen patients received grafts from an HLA-matched sibling, 4 from mismatched relative, 9 from HLA-matched unrelated and the remaining 10 from HLA-mismatched unrelated donors. Twenty-seven patients received bone marrow, 6, peripheral blood and 6, umbilical cord blood. Most patients received calcineurin inhibitor with methotrexate or mycophenolate for GVHD prophylaxis (n=30/39).

Table 1.

Patient and transplant characteristics: Bone marrow failure

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Number | 39 | |

| Age at transplant - no. (%) | ||

| Median (min-max) | 7 (0.4–51) | |

| 0–9 | 23 | |

| 10–19 | 11 | |

| ≥20 | 5 | |

| Performance score - no. (%) | ||

| 90–100% | 33 | |

| < 90% | 3 | |

| Not reported | 3 | |

| HCT-Comorbidity Index - no. (%) | ||

| 0–2 | 21 | |

| ≥3 | 6 | |

| Not collected before 2007 | 12 | |

| Donor type – no. (%) | ||

| HLA-matched sibling | 16 | |

| Haploidentical relative | 4 | |

| 8/8 matched unrelated bone marrow/peripheral blood | 9 | |

| 7/8 matched unrelated bone marrow/peripheral blood | 6 | |

| 6/6 matched unrelated cord blood | 1 | |

| 5/6 matched unrelated cord blood | 3 | |

| Graft type - no. (%) | ||

| Bone marrow | 27 | |

| Peripheral blood | 6 | |

| Umbilical cord blood | 6 | |

| Conditioning intensity - no. (%) | ||

| Myeloablative | 13 | |

| Busulfan/cyclophosphamide ± fludarabine ± anti-thymocyte globulin | 4 | |

| Busulfan + fludarabine + anti-thymocyte globulin | 1 | |

| Busulfan + melphalan ± fludarabine ± anti-thymocyte globulin | 2 | |

| Busulfan + thiotepa + fludarabine + anti-thymocyte globulin | 2 | |

| Total body irradiation 1000 cGy + cyclophosphamide | 1 | |

| Treosulfan + fludarabine ± anti-thymocyte globulin | 3 | |

| Reduced-intensity | 26 | |

| Busulfan + fludarabine ± anti-thymocyte globulin | 3 | |

| Cyclophosphamide + fludarabine + anti-thymocyte globulin | 1 | |

| Melphalan + anti-thymocyte globulin | 1 | |

| Melphalan + fludarabine + anti-thymocyte globulin | 3 | |

| Melphalan + fludarabine + alemtuzumab | 14 | |

| Total body irradiation 200 cGy + cyclophosphamide + fludarabine + anti-thymocyte globulin | 2 | |

| TBI 300cGy + cyclophosphamide + fludarabine | 1 | |

| TBI 200 cGy + fludarabine | 1 | |

| Graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis - no. (%) | ||

| CD34+ selection | 1 | |

| T-cell depletion | 2 | |

| Tacrolimus/methotrexate | 7 | |

| Tacrolimus/mycophenolate mofetil | 3 | |

| Tacrolimus alone | 1 | |

| Cyclosporine/methotrexate | 13 | |

| Cyclosporine/mycophenolate mofetil | 7 | |

| Cyclosporine alone | 5 | |

| Year of transplant - no. (%) | ||

| 2000–2004 | 5 | |

| 2005–2008 | 9 | |

| 2009–2012 | 13 | |

| 2013–2017 | 12 | |

| Follow-up - median (min-max) | 60 (6–170) | |

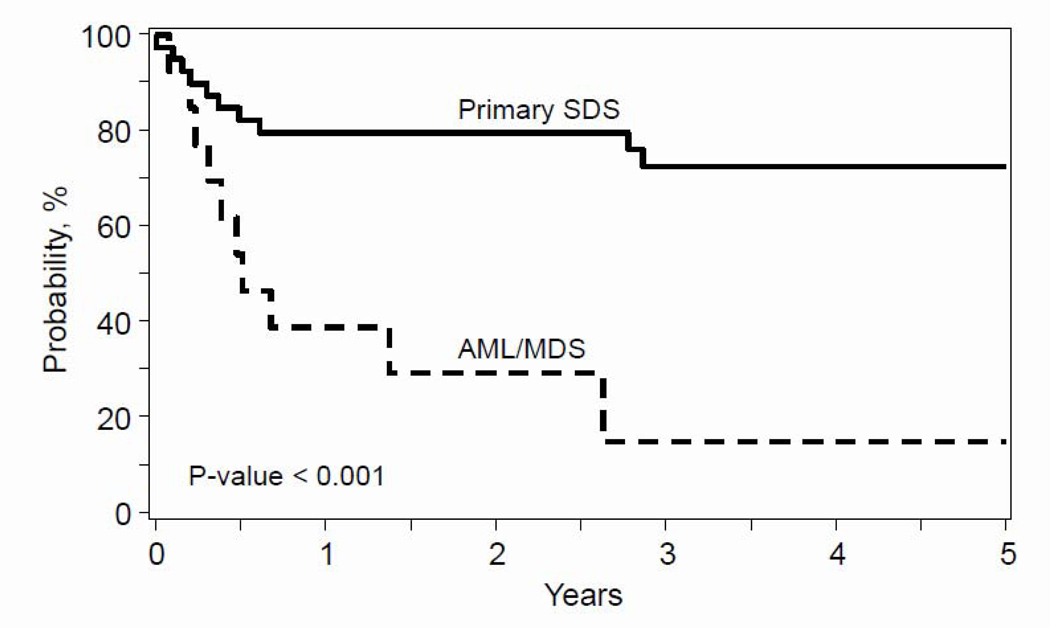

The median time to neutrophil and platelet recovery was 15 and 26 days, respectively. The day-28 cumulative incidence of neutrophil recovery was 95% (95% CI 84–99.8) and day-100 platelet recovery, 89% (95% CI 74–98). One patient had primary graft failure and 2 patients, secondary failure. The patient who experienced primary graft failure received a 5/6 HLA-matched unrelated umbilical cord blood graft, with a reduced intensity regimen (melphalan/fludarabine/anti-thymocyte globulin). Of the two patients with secondary graft failure, one received peripheral blood from a haploidentical relative and myeloablative regimen (busulfan/thiotepa/fludarabine/anti-thymocyte globulin) and the other, HLA-matched unrelated bone marrow, and reduced intensity regimen (TBI 200cGy/ cyclophosphamide/fludarabine/anti-thymocyte globulin). All three patients received a second transplant from a different donor and died from graft failure after their second transplant. Seven patients developed grade II and three patients grade III-IV acute GVHD. The day-100 cumulative incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was 26% (95% CI 13 – 41). Five patients developed chronic GVHD (n=2 limited and n=3 extensive). The 1- and 5-year incidence of chronic GVHD was 11% (95% CI 3 – 22) and 13% (95% CI 4 – 26). The 1- and 5-year overall survival was 79% (95% CI 65 – 91) and 72% (95% 7 CI 57 – 86), Figure 1. Most deaths occurred within 8 months after transplantation; graft failure (n=2), graft-versus-host disease (n=2), infection (n=2), veno-occlusive disease (n=1), and organ failure (n=1). Among these early deaths, 4 patients received myeloablative conditioning regimens, and the other 4 received reduced-intensity regimens. There were two late deaths, one at 33 months from graft failure after a second transplant and the other at 34 months from GVHD. Both of these late deaths were patients receiving reduced-intensity conditioning.

Figure 1:

Overall Survival

The 5-year probability of overall survival after transplantation for bone marrow failure (cytopenia/aplastic anemia) was 72% and after transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome 15% (p<0.0001).

Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia

Thirteen patients were transplanted for myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia. Transplantations occurred between 2010 and 2016. Five of thirteen patients were confirmed to have biallelic SDS mutation. Testing information was not available for 8 patients. Patient, disease and transplant characteristics are shown in Table 2 and outcomes after transplantation in Table 3. The median age at transplant was 18 years (range 11 – 50). Twelve patients underwent transplantation within 6 months and 1 patient, 108 months after diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukemia. 6 patients had performance score 90–100 and 7 patients reported HCT-CI ≤2. Among the 5 patients transplanted for acute myeloid leukemia, 3 were in primary induction failure and 2 were in first complete remission at the time of transplant. Among the 8 patients transplanted for myelodysplastic syndrome, 1 had refractory anemia, 1 refractory anemia with excess blasts-1, 1 refractory anemia with excess blasts-2, 1 refractory cytopenia with multilineage dysplasia and ringed sideroblast, 1 5q-syndrome, and the remaining 3 unspecified myelodysplastic syndrome. Conditioning regimen intensity was myeloablative (n=9) and reduced intensity (n=4). Three patients received grafts from an HLA-matched sibling, 1 from a haploidentical relative, 4 from an HLA-matched unrelated donor and the remaining 5 from an HLA-mismatched unrelated donor. Eight patients received bone marrow, and the other 5 received peripheral blood. Most patients received calcineurin inhibitor with methotrexate or mycophenolate for GVHD prophylaxis.

Table 2.

Patient and transplant characteristics: acute myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome

| UPN | Age years | Performance score | HCT-CI | Indication | Disease status | Donor | Graft | Conditioning intensity | Conditioning regimen | GVHD prophylaxis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | 90 | 0 | AML | CR1 | 7/8 matched unrelated | BM | Myeloablative | Bu/Mel/Flud/ATG | T-cell depletion |

| 2 | 21 | 70 | 4 | AML | Induction failure | HLA-matched sibling | PB | Reduced-intensity | Mel/Cladribine/ATG | CSA |

| 3 | 14 | 90 | 1 | AML | CR1 | 7/8 matched unrelated | BM | Myeloablative | Bu/Thiotepa/Flud/Alemtuzumab | CSA/MMF |

| 4 | 20 | 70 | 6 | AML | Induction failure | HLA-matched sibling | PB | Myeloablative | Bu/Clofarabine | TAC/MMF |

| 5 | 40 | 80 | 2 | AML | Induction failure | 8/8 matched unrelated | PB | Reduced-intensity | Flud/Mel/Alemtuzumab | CSA |

| 6 | 13 | 100 | 0 | MDS | RAEB-2 | 8/8 matched unrelated | BM | Reduced-intensity | Flud/Mel/Alemtuzumab | CSA/MTX |

| 7 | 18 | 80 | 3 | MDS | RA | 7/8 matched unrelated | BM | Myeloablative | Flud/Cy/Thiotepa/ATG | T-cell depletion |

| 8 | 13 | 100 | 0 | MDS | RCMD | 8/8 matched unrelated | BM | Myeloablative | Bu/Flud/ATG | CSA/MTX |

| 9 | 20 | 100 | 2 | MDS* | 5q-syndrome | HLA-matched sibling | BM | Myeloablative | Bu/Flud | TAC/MTX |

| 10 | 25 | 90 | 3 | MDS* | MDS,NOS | 8/8 matched unrelated | BM | Myeloablative | Flud/Mel/Thiotepa/Alemtuzumab | TAC/MTX |

| 11 | 50 | 70 | 3 | MDS | MDS,NOS | 8/8 matched unrelated | PB | Reduced-intensity | TBI 200 cGy/Cy/Flud | TAC/MMF |

| 12 | 11 | __ | 1 | MDS* | RAEB-1 | Mismatched relative | PB | Myeloablative | Bu/Flud/ATG | __ |

| 13 | 14 | 80 | 4 | MDS | MDS,NOS | 7/8 matched unrelated | BM | Myeloablative | Bu/Mel | CSA/MTX |

Abbreviations:

HCT-CI: hematopoietic cell transplant-comorbidity index; AML: acute myeloid leukemia; MDS: myelodysplastic syndrome; CR: complete remission; RAEB: refractory anemia with excess blast; RA: refractory anemia; RCMD: refractory anemia with multilineage dysplasia; NOS: not otherwise specified; BM: bone marrow; PB: peripheral blood; Bu: busulfan; Mel: melphalan; Flud: fludarabine; ATG; anti-thymocyte globulin; Cy: cyclophosphamide; TBI: total body irradiation; CSA: cyclosporine; MMF: mycophenolate; TAC: tacrolimus; MTX: methotrexate

Cytogenetic abnormality: deletion 5q (UPN 9), deletion 20q (UPN 10), monosomy 7 (UPN 12)

Table 3.

Outcomes: AML or MDS

| UPNh | Neutrophil recovery | Platelet recovery | Acute GVHD | Chronic GVHD | Relapse | Survival status | Time to death/follow-up | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 days | 46 days | No | No | No | Dead | 5 months | Organ failure |

| 2 | 10 days | 17 days | No | No | No | Dead | 3 months | Infection |

| 3 | 21 days | 31 days | Grade II | No | Yes, 13 months | Dead | 16 months | Recurrent disease |

| 4 | 13 days | 16 days | No | Extensive | Yes, 3 months | Dead | 8 months | Recurrent disease |

| 5 | 14 days | 11 days | Grade III | Yes Limited | Yes, 5 months | Dead | 6 months | Recurrent disease |

| 6* | 48 days | 48 days | Grade IV | No | Yes, 9 months | Dead | 32 months | Recurrent disease |

| 7 | 15 days | 19 days | No | No | No | Alive | 65 months | __ |

| 8 | 15 days | 26 days | Grade III | No | No | Dead | 6 months | Veno-occlusive disease |

| 9 | 25 days | 79 days | No | Extensive | No | Alive | 23 months | __ |

| 10 | 17 days | No | Grade IV | No | Yes, 2 months | Dead | 2 months | Recurrent disease |

| 11 | 15 days | No | No | No | No | Dead | 4 months | Organ failure |

| 12* | No | No | No | No | Yes, 10 months | Dead | 17 months | Recurrent disease |

| 13 | 8 days | No | Yes Grade IV | No | No | Dead | 0.9 months | Organ failure |

Second transplant (UPN 6: 14 months after the first transplant; UPN 12: 2 months after the first transplant) GVHD: graft-versus-host disease

The median time to neutrophil and platelet recovery was 15 and 26 days, respectively. Twelve of 13 patients achieved neutrophil recovery and 9 of 13 patients achieved platelet recovery. One patient had primary graft failure and another secondary graft failure. The patient with primary graft failure received peripheral blood from a haploidentical relative, with reduced intensity regimen (busulfan/fludarabine/anti-thymocyte globulin). This patient received a second transplant from a different haploidentical donor but died from recurrent disease (myelodysplastic syndrome). The patient with secondary graft failure received an HLA-matched unrelated bone marrow graft and reduced-intensity conditioning regimen (melphalan/fludarabine/alemtuzumab). This patient had a second transplant using the same donor 14 months after the first and died 17 months later from graft-versus-host disease.

One patient developed grade II and 5 patients grade III-IV acute GVHD. Three patients developed chronic GVHD (n=1 limited and n=2 extensive). Eleven patients died, with the remaining two surviving (15%), Figure 1. Most deaths occurred within 8 months after transplantation; recurrent/persistent disease (n=3), organ failure (n=3), veno-occlusive disease (n=1), infection (n=1). There were three late deaths, two of them at 17 months from recurrent/persistent disease and the other at 32 months from recurrent disease.

Discussion:

This study is one of the largest series reported to date of transplantations in SDS. A majority of patients transplanted for BMF survived. Although this is in keeping with another report from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplant (13), a 5-year survival of 70% leaves room for improvement. Outcomes in patients with SDS transplanted for MDS/AML, however, are quite poor due to both relapsed disease and mortality from transplant-related complications. Mild to moderate marrow failure with variable severity of neutropenia is quite common in SDS (14). However, only a subset of patients with SDS will progress to severe pancytopenia or transform into malignancy (15–17). Therefore, preemptive transplant is not recommended in SDS. Serial complete blood counts and bone marrows in patients with SDS are recommended 9 as surveillance for malignant transformation by the SDS draft consensus guidelines (18). This recommendation is based on expert opinion, as limited published data exists about the utility of surveillance in this and other populations at risk for leukemic transformation. True clinical practice regarding surveillance, however, likely varies significantly. The small numbers of MDS/AML subjects in this cohort do not allow for analysis based on the severity of AML or MDS. The recent retrospective study of 36 patients with MDS/AML through the SDS registry recorded a 3-year survival of 11% for AML and 51% for MDS (19). In the current analysis, the 2 patients who are alive were transplanted with early MDS (refractory anemia and 5q-syndrome). Our observations are consistent with the report from the SDS registry (19) and suggest that for those with transformation transplantation soon after onset of dysplasia or cytogenetic abnormality is desirable. Future prospective studies incorporating structured surveillance are needed to demonstrate whether early detection of progression of marrow disease and transformation does indeed confer a survival advantage. Novel therapeutic approaches or transplant strategies may be required for those with advanced disease to address resistant disease. Mortality from transplant complications remains the predominant cause of death in this cohort, which is consistent with the existing literature (2, 3). More recent, but small, single-institution series have suggested survival after transplant for SDS can be improved by the use of reduced-intensity preparative regimens (9, 10, 20). In the current analysis, among patients transplanted for BMF, 78% of patients who received myeloablative conditioning and 71% of patients who received reduced-intensity conditioning are alive (p=0.65). Although we failed to detect a difference in survival by conditioning regimen-intensity we acknowledge our modest sample size is insufficient to address this question. Interestingly, in our cohort death was predominantly infection or GVHD related rather than direct organ toxicity, which may reflect the higher number of reduced intensity regimens used. Of the 13 patients transplanted for AML/MDS, the 3 patients who are alive received myeloablative conditioning regimen. All patients with AML/MDS who received reduced-intensity regimens died. Better leukemia-control 10 and higher survival after myeloablative conditioning has been recorded by others and should be adopted for transplantation of patients with SDS transformed to AML/MDS (21, 22).

Overall bone marrow was the predominant graft (35 of 52 transplants). Eleven transplants used peripheral blood and 6 transplants, umbilical cord blood. The small sample size prohibits us from studying outcomes by graft type. The 6-month incidence of grade II-IV acute GVHD was 29% and 27% after transplantation of bone marrow and peripheral blood, respectively (p=0.89). However, the corresponding 5-year incidence of chronic GVHD was 14% and 27% (p=0.29). The incidence is twice as high with transplantation of peripheral blood and does not support the use of peripheral blood despite the lack of a significant difference (wide and overlapping confidence intervals because of the limited sample size). The use of peripheral blood grafts for transplantation for AML/MDS also failed to show a survival advantage. Taken together, peripheral blood should be avoided in this population.

The number of transplants taking place for SDS has increased over time, which may reflect improved disease recognition secondary to disease progression. The discovery of a causative gene, SBDS, in which biallelic mutations lead to disease in the majority of SDS individuals along with improved phenotypic understanding and higher index of suspicion has led to improved diagnosis (1, 23). This is reflected in recent work suggesting that young individuals in historical MDS cohorts may contain undiagnosed SDS individuals as demonstrated by Lindsley et al (24). Our study is limited by its lack of complete data on biallelic SBDS mutations and the more recent mutations for the SBDS-like phenotype (EFL1, DNAJC21 and SRP54). A high index of suspicion is warranted in young individuals with MDS less than 40 years of age to identify these individuals with cryptic SDS diagnoses to inform clinical care such as testing of related donors of mutation status before donor selection and tailoring of transplant preparative regimen. In summary, this analysis demonstrates important opportunities for improvement in transplantation for SDS. Firstly, outcomes are very poor in those with myeloid malignancy compared with marrow aplasia. These data support a standardized approach to blood and marrow screening to test the hypothesis that patients can be identified for transplant before the onset of myeloid malignancy and improve outcomes with earlier transplant. Secondly, patients with established myeloid malignancy should be considered for novel treatments and transplant strategies including myeloablative conditioning regimens that will improve disease control.

Highlights.

5-year survival of 72% after transplantation for SDS related BMF is better compared to historical reports

Transplantation for SDS related MDS or AML does not extend survival

A standardized approach to screening may identify patients for transplant before onset of MDS or AML

Acknowledgments

Funding Source

The Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research is supported primarily by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); grants N00014–15-1–0848 and N00014–16-1–2020 from the Office of Naval Research. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donadieu J, Michel G, Merlin E et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: experience of the French neutropenia registry. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:787–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cesaro S, Oneto R, Messina C et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for Shwachman-Diamond disease: a study from the European Group for blood and marrow transplantation. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;131:231–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hsu J, Vogelsang G, Jones R, Brodsky R. Bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okcu F, Roberts W, Chan K. Bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: report of two cases and review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;21:849–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai P, Sahdev I, Herry A, Lipton J. Fatal cyclophosphamide-induced congestive heart failure in a 10-year-old boy with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and severe bone marrow failure treated with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1990;12:472–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleitz J RS, Goldman F, Ambruso D et al. Successful allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) for Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29:75–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vibhakar R, Radhi M, Rumelhart S, Tatman D, Goldman F. Successful unrelated umbilical cord blood transplantation in children with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;36:855–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sauer M, Zeidler C, Meissner B et al. Substitution of cyclophosphamide and busulfan by fludarabine, treosulfan and melphalan in a preparative regimen for children and adolescents with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatla D, Davies SM, Shenoy S et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning is effective and safe for transplantation of patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Przepiorka D, Weisdorf D, Martin P, et al. 1994 Consensus Conference on Acute GVHD Grading. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15:825–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cesaro S, Pillon M, Sauer M, et al. Long-term outcome after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant for Shwachman–Diamond Syndrome: a retrospective analysis and a review of the literature by the Severe Aplastic Anemia Working party of the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (SAAWP-EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020; doi 10.1038/s41409-020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Myers KC, Bolyard AA, Otto B et al. Variable Clinical Presentation of Shwachman–Diamond Syndrome: Update from the North American Shwachman–Diamond Syndrome Registry. J Pediatr. 2014;164:866–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donadieu J, Fenneteau O, Beaupain B et al. Classification and risk factors of hematological complications in a French national cohort of 102 patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Haematol. 2012; 97:1312–1319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dale DC, Bolyard AA, Schwinzer BG et al. The Severe Chronic Neutropenia International Registry: 10-Year Follow-up Report. Support Cancer Ther. 2006;3:220–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cada M, Segbefia CI, Klaassen R et al. The impact of category, cytopathology and cytogenetics on development and progression of clonal and malignant myeloid transformation in inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Haematol. 2015;100:633–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dror Y, Donadieu J, Koglmeier J et al. Draft consensus guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1242(1):40–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myers KC, Furutani E, Weller E et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome and myelodysplastic syndrome or acute myeloid leukaemia: a multicentre, retrospective, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020; 7:e238–246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burroughs LM, Shimamura A, Talano J-A et al. Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation Using Treosulfan-Based Conditioning for Treatment of Marrow Failure Disorders. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23:1669–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott BL, Pasquini MC, Logan BR, et al. Myeloablative versus reduced-intensity hematopoietic cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2017; 35: 1154–1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eapen M, Brazauskas R, Hemmer M, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplant for acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome: conditioning regimen intensity. Blood Adv. 2018; 2:2095–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myers KC, Bolyard AA, Otto B et al. Variable Clinical Presentation of Shwachman–Diamond Syndrome: Update from the North American Shwachman–Diamond Syndrome Registry. J Pediatr. 2013; 164:866–870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindsley RC, Saber W, Mar BG et al. Prognostic Mutations in Myelodysplastic Syndrome after Stem-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:536–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]