Abstract

Background:

Kinship foster caregivers often face serious challenges but lack adequate parenting capacities and resources. The importance of parenting interventions for kinship foster caregivers has been recognized, and researchers have assessed the effect of various parenting interventions on the caregivers and children. However, no systematic review has been conducted to summarize findings related to parenting interventions targeting kinship care.

Objectives:

This study systematically summarizes the effect of parenting interventions on kinship foster caregivers and their cared for children, and examines the intervention strategies and research methods used in order to provide a context in which to better understand effects of interventions.

Methods:

From six academic databases, 28 studies were identified for review. A data template was used to extract the following information from each study: intervention targets, research design, settings, intervention description, outcome measures, and main results for each study.

Results:

Various parenting interventions targeting kinship foster care families have been developed to improve parenting capacities and reduce parental stress. Most of the interventions had a positive impact on the outcomes of both caregivers and children, although the assessed outcomes often differed across studies. Parenting interventions improve caregivers’ parenting competency, reduce parental stress, and advance child wellbeing. However, some interventions appear less promising in achieving targeted goals.

Discussion:

The findings suggest that promoting evidence-based parenting interventions with a special focus on kinship care is important for child welfare. Future directions for research are also discussed in this study.

Keywords: Kinship care, parenting intervention, parenting outcome, child outcome, systematic review

1. Introduction

Kinship care occurs when children are removed from their homes and placed with relatives or someone considered close to the family (fictive kin). In the United States, there were about 2.3 million (3.1%) children in 2016 being raised by their relatives while no biological parents were present (Census Bureau, U.S., 2016). Further, according to Child Welfare Information Gateway (2017), among the 427,910 children in foster care in 2015, 30% were placed with kin families. The major reasons for children entering kinship care include child maltreatment, parental substance abuse, incarceration, mental illness, military deployment, and young age of parents (Gleeson et al., 2009; Vandivere et al., 2012).

Kinship care is currently the preferred placement type for children, because it is considered the “least-restrictive, most family-like placement” and in the child’s best interest (Hegar & Scannapieco, 2005; Wu, White, & Coleman, 2015). It helps preserve family relationships and maintain family connections, so it is beneficial for children’s safety and stability (Bunch, Eastman, & Griffin, 2007; Coleman & Wu, 2016; Frame, Berrick, & Brodowski, 2000) Children in kinship care have fewer placement disruptions (Koh, 2010; Strozier & Krisman, 2007; Testa, 2001, 2002; Winokur, Crawford, Longobardi, & Valentine, 2008; Zinn, DeCoursey, Goerge, & Courtney, 2006), and lower rates of physical and mental health problems than children in non-kin foster care (Keller et al., 2001; Rosenthal & Curiel, 2006; Tarren-Sweeney & Hazell, 2006; Winokur, Holtan, & Valentine, 2009).

Kin caregivers differ in important ways from non-kin caregivers; they are less educated, have a lower income, and are more likely to live in a single person household and to be older, such as a grandparent. They are also often in poorer health, and receive less financial support and parental training (Cuddeback, 2004; Cuddeback & Orme, 2001; Ehrle & Geen, 2002; Leder, Grinstead, & Torres, 2007). This presents challenges because the children involved often exhibit psychosocial problems, including poor mental health, antisocial behavioral, substance abuse, and academic failure (Blome, Shields, & Verdieck, 2009; Hussey & Guo, 2003; Markinkovic & Backovic, 2007; Massinga & Pecora, 2004; Stovall-McClough & Dozier, 2004), and separation from the parents exacerbates their issues (Wu, White, & Coleman, 2015). There is also a concern that those who have had difficulty raising their own children will have difficulty raising their grandchildren or relative’s children (Gibson, 2005). Therefore, kin caregivers need training and services, but their use of services is limited (Coleman & Wu, 2016). The unmet needs of kinship caregivers may negatively affect the well-being of children in their care (Coleman & Wu, 2016).

It is important that kinship caregivers receive parenting interventions. It is equally important that we systematically examine existing parenting interventions and their impacts on caregiver and child outcomes. This would provide a solid evidence base for the selection and application of interventions, as well as their development and advancement. However, little systematic review has been conducted on parenting interventions that target kinship caregivers. The current study fills this gap.

1.1. Formal and Informal Kinship Care

Most kinship care is “informal”, with children living with relatives and no child welfare agency involved. “Formal kinship care” refers to children placed with kin, in the custody of the state, so the child welfare system is involved (Child Welfare League of America, 1994). The ratio of children in informal to formal kinship care is about 6:1 (Goodman & Silverstein, 2001). Formal kin and non-kin caregivers can receive reimbursement, or they can receive the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) child-only grants (Goodman et al., 2004).

Formal kin caregivers may face more challenges than informal kin caregivers. In their literature review, Swann and Sylvester (2006) found that formal kin caregivers are older, less educated, less likely employed, and more likely to have been in a welfare system than informal caregivers, although they are less likely to live in poverty or experience food insecurities. Goodman, Potts, Pasztor & Scorzo (2004) found that grandmothers in formal kinship care situations are less likely to be married, have more children to care for, and are more likely to take care of children with behavioral problems. Children in formal kinship care are more likely to have more behavioral (Starr, Dubowitz, Harrington & Feigelman, 1999), school, and physical health problems than those in informal kinship care (Dubowitz & Sawyer, 1994).

1.2. Parenting Stress

The challenges of kinship care may increase caregivers’ parenting stress (N’zi, Stevens, & Eyberg, 2016), which is manifested in negative psychological feelings and reactions (Deater-Deckard, 1998). Such negative feelings may affect caregiver functioning, children’s well-being, or the parent/kin caregiver-child relationship. Foster parents, including kin caregivers, have higher levels of parenting stress compared to parent caregivers (Kortenkamp & Ehrle, 2002; Lee, Clarkson-Hendrix, & Lee, 2016).

Kin caregivers are at an elevated risk of stress compared with non-kin caregivers, because of their poorer physical and mental health (Kelley, Whitley, Sipe, & Yorker, 2000; Leder, Grinstead, & Torres, 2007), financial difficulties (Waldrop & Weber, 2001), and lack of social supports (Gleeson, Hsleh, & Cryer-Coupet, 2016; Harden, Clyman, Kriebel, & Lyons, 2004). Kin caregivers may also have role conflicts with the birth parents, which can further increase their stress levels (Leathers & Testa, 2006). Given that the majority of kinship caregivers are African American (N’zi, Stevens, & Eyberg, 2016), cultural and systemic barriers can elevate their parenting stress (Washington, Gleeson, & Rulison, 2013). In addition, although children and caregivers in informal kinship situations need services and support, they are usually left out of the public assistance system (Lin, 2018; Wu, 2017).

Children in kinship care situations also contribute to elevated parenting stress. For example, they are older than children in non-kinship care (Beeman, Kim, & Bullerdick, 2000). They are also less likely to receive public assistance, including Medicaid, even though they are qualified (Ehrle & Geen, 2002), and they receive fewer healthcare services than those in non-kinship care (Morse, 2005). It is not surprising that kinship caregivers that take care of older children report higher level of stress (Kelley, 1993), as do those caring for children with health problems (Gerard, Landry-Meyer, & Guzell Roe, 2006). Further, parenting stress and child behavioral problems exacerbate each other. Parenting stress is positively associated with negative disciplining patterns, which increase child behavior problems (Kelley, Whitley, & Campos, 2011). Therefore, parenting intervention is important to help kinship caregivers address their stress and improve parenting skills.

1.3. Parenting Intervention and a Research Gap

Given the challenges faced by kinship foster caregivers, improving their parenting competency should be an integral component of kinship foster care promotion. Parenting interventions are defined as having a central focus on parenting which offers a structured set of activities to engage parents and enhance their parenting behaviors, such as nurturing, teaching, monitoring, and discipline (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), 2015). Parenting interventions may aim to decrease the stress of caregivers and to reduce caregivers’ reactivity to child behavior (Fisher & Stoolmiller, 2008), but most address risk factors for caregivers’ health and social support rather than parenting stress (N’zi et al., 2016; Strozier, 2012).

Washington, et al. (2018) conducted a systematic review describing psychosocial factors associated with the behavioral health of children in foster care. They identified almost 50 psychosocial factors, including the most frequently examined factors of caregivers’ parenting practices. However, they did not evaluate intervention outcomes. Lin’s (2014) systematic review of thirteen studies evaluating kinship care services and programs indicates a focus on financial assistance, support services, and training or education. Even though some latter interventions were intended to target grandparents in kinship care, parenting education was missing in their interventions. In their systematic review, McLaughlin, Ryder, and Taylor (2017) focused on psychosocial and physical health interventions to caregiving grandparents, which were about cognitive-behavioral or skills-based training, psychoeducation, or the development of support groups. It is important to note that many parenting interventions targeted foster parents rather than kinship caregivers specifically, despite substantial differences between kin and non-kin care situations (Chamberlain et al., 2008).

Although kinship parenting interventions are important and widely adopted, little systematic review has been done to summarize the outcomes of intervention directed toward kin caregivers. Such a review is required for the selection, development, and application of evidence-based practice designed to improve kinship caregiver’s parenting abilities and alleviate their parenting stress. To fill this gap in the literature, the current study systematically reviews studies that assessed the effect of parenting interventions on both kinship caregivers and their children.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Search Strategies

The following inclusion/exclusion criteria were used to identify relevant studies. First, studies had to focus on parenting intervention for foster care families. The intervention followed the definition provided by the U.S. DHHS (2015), and the intervention aimed to improve parenting outcomes for caregivers and/or children. Second, some studies broadly mentioned that they provided interventions to foster families without mentioning kinship families specifically. Studies were included in this review if they clearly stated that they included kinship families as the participants, otherwise studies were excluded. Third, only quantitative studies were included in the review. Finally, all studies must have been published in peer-reviewed journals in English.

Articles were identified by searching the following six academic databases: PsychINFO, PubMed, Social Services Abstracts, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, Sociological Abstracts, and Web of Science Web. Search terms were defined based on the suggestions from social work experts and similar systematic reviews. The following terms were searched in a conceivable combination in all the databases: ((treatment OR program OR training OR intervention OR therapy OR support OR counseling) AND ((kinship foster care) OR (kinship care) OR (kin* caregiver) OR (kin* placement) OR (relative care*) OR grandparent*) AND PEER(yes)) AND parenting.

2.2. Review Process

After articles were identified using these search terms, the titles and abstracts were reviewed to identify those that may meet the inclusion criteria, then the full-text articles were retrieved. To ensure reliability of this review, two members of the research team read abstracts and full texts independently. When there was a disagreement, the authors discussed the article in relation to inclusion criteria. To achieve consistency in the review process, the two researchers reviewed all studies using a data retrieving template developed by the research team. The extracted information included target of intervention, research design, settings of interventions, intervention descriptions, description of samples, statistical tests, measures taken, and key findings.

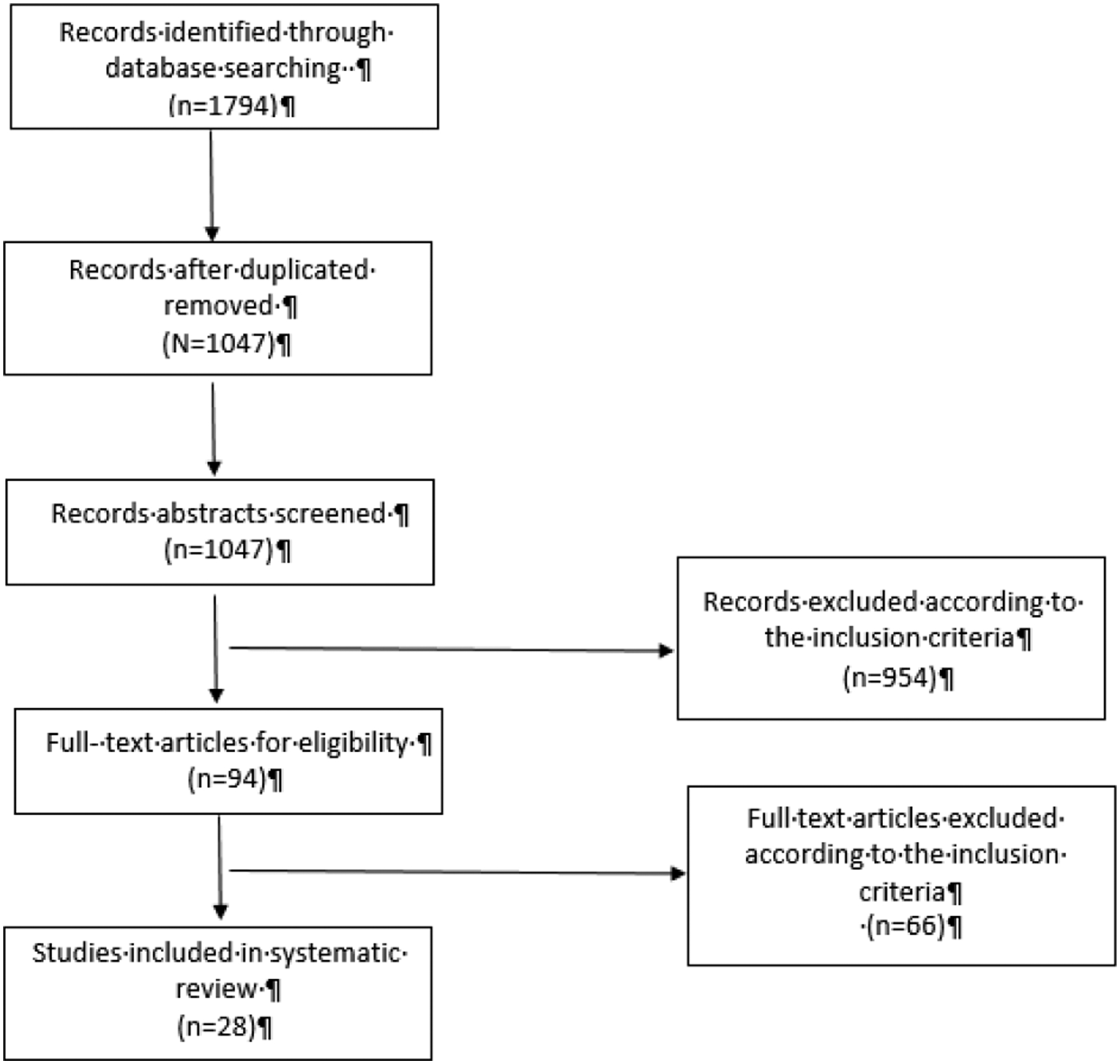

Figure 1 shows that 1794 potentially relevant citations were identified from the database search. After checking for duplications, 1047 citations were retained for closer review. The abstract review excluded 953 citations which did not meet inclusion criteria. Most of these studies were excluded because they lacked empirical data, the interventions did not mention kinship caregivers as participants, or the studies were qualitative. Finally, full-text review excluded 66 studies, resulting in 28 studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Of the 28 studies reviewed, 15 focused on kin caregivers, and 13 on kin and non-kin caregivers. Of the 13, two separated kin from non-kin in their analyses, while 11 did not. Therefore, data specific to kin caregivers are available for 17 studies. A summary of the 28 studies and the results of the sub-sample of 17 studies are presented in this paper. Table 1 summarizes pertinent information on the 28 studies, and is arranged according to such data separation.

Figure 1.

Study Identification Flow Chart

Table 1.

The Results of Systematic Reviews

| Study | Location | Target of Intervention | Research Design | Setting/Format of Intervention | Intervention Description | Sample Size | Statistic Method | Outcomes | Key Findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | Length | Caregivers | Children | ||||||||

| Studies that focused on kin caregivers (n = 15) | |||||||||||

| Campbell, Carthron, Miles, & Brown (2012) | The United States | Grandparents | Pre-experimental design | Case management | The grandparenting program used the System of Care (SOC) case management model, a family- centered, strength- and empowerment-based program designed to enhance the wellbeing and successful functioning of custodial grandparents and their grandchildren. The goal of this program was develop their abilities to parent, and to find and use resources that would improve their health and well-being, as well as that of their grandchildren. | n/a | 68 families | Pre and post t-test | Quality of life | Behavioral and emotional functioning | Grandparents perceived their mental health improved after participating in the program. Perceptions about physical health were also improved. Grandparents reported fewer child external behavioral and emotional problems. There was little change from pretest to posttest in child internalized behaviors. |

| Duquin, McCrea, Fetterman, & Nash (2004) | The United States | Kinship caregivers | Pre-experimental design | Faith-based group setting | A faith-based setting and focused on education in (a) Health, Exercise, Nutrition, and Stress Management; (b) Parenting Education; and (c) Religious Practices (such as worship, scripture, and prayer) | 12 weeks | 12 participants | Basic descriptive analysis and focus group | Parenting and childrearing attitudes Stress Spiritual well-being |

n/a | The program has positive impacts on participants. |

| Feldman & Fertig, (2013). | The United States | Kinship caregivers | RCT | Case Management with families | The enhanced Kinship Navigation Program: The service includes assistance and referral to families based on their needs, parent support groups, education groups, and children’s groups to enhance social support. | 6 months | 437 caregivers (Intervention group: 210; control group: 217) | Chi-square, ANOVA, and t-test | Family needs Social support Caregiver stress |

Child behavior | Caregivers had many of their expressed needs met. However, no significant differences in social support, caregiver stress, child behavior problems between the two groups. |

| Foli et al.,(2018). | The United States | Kinship caregivers | Pre-experimental design and qualitative research design | Group sessions | Trauma-Informed Parenting Classes building on the strengths and acknowledging the challenges of kinship parenting, as well as recognizing the trauma that children have experienced, specialized information for traumatized children through the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. | Eight modules; approximately 15 hours of class time. | 16 parents | Paired t-test and fisher’ s exact test. | Family environment Strengths and difficulties Child Rearing practice Stress |

n/a | The quantitative data does not support expected changes in parenting stress, parent-to-child nurturing, perceptions of child strengths and difficulties, and the family environment (as measured by surveys), but qualitative data did support the overall positive impact of the intervention. |

| Kelley, Yorker, Whitley, & Sipe (2001) | The United States | Grandparents | Pre-experimental design | Home visits and group meetings | This multimodal, home-based intervention aimed to reduce psychological stress, improve physical and mental health, and increase the social support and resources of grandparents raising grandchildren. | 6 months | 24 participants | Paired t-test | Psychological stress Family resource Physical health Social support |

n/a | The intervention resulted in improved mental health scores, decreased psychological distress scores, and increased social support scores. |

| Kelley, Whitley, Campos (2010) | The United States | Grandparents | Pre-experimental design | Home-based: home visits and other support services | The intervention is designed to empower custodial grandparents by increasing their personal sense of competence and to help them gain a sense of control over their well-being, including their physical and mental health. | 12 months | 529 female caregivers | Paired t-test | Physical health | n/a | The mean scores of health attributes were significantly increased. No significant differences in mean scores for physical functioning, body pain, general health, and social functioning. |

| Kicklighter et al., (2009). | The United States | Grandparents | Pre-experimental design | Home-based: home visits | It is home-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. The primary goals were to increase grandparents’ knowledge and skills in selecting and preparing healthy foods and to increase the grandparents’ and grandchildren’s physical activity levels. | n/a | 5 female African America n Grandpa rents | Descriptive analysis | Nutrition and physical activity knowledge self-efficacy | n/a | Grandparents scored higher on nutrition and physical activity knowledge and their self-efficacy improved, although the most health status indicators remained unchanged. |

| Kirby& Sanders (2014) | Australia | Grandparents | RCT | Six group sessions and three telephone consultations | Grandparent Triple P program: It utilized inputs from grandparents to meet their needs. The needs which to be addressed in this intervention included the use of positive parenting strategies, building a positive-parenting team, and coping negative emotions. | 9 weeks; 6 groups lessons lasting 120 min; 3 telephone consultations lasting between 20–30 min | Intervention group: 28 families; control group: 26 families | Chi-square and ANOVA | Parenting style Parenting confidence Grandpa rent adjustment |

Child behaviors | Significant improvements were found on grandparent-reported child behavioral problems; parenting confidence; grandparent depression, anxiety, stress; and improved relationships with the parents. |

| Leung, Sanders, & Kriby (2014) | China | Kinship caregivers | RCT | Group sessions | See Kirby & Sanders (2014) | N/A | 56 caregivers (Intervention group: 29; control group: 27) | ANCOVA | Grandpa rent-adult parents relationship | Child behavior | Significant decrease in child behavioral problems and a significant increase in grandparent self-efficacy |

| Littlewood, Strozier & Whittington, (2014). | The United States | Kinship caregivers | Pre-experimental design | Home visits, developmental screening, resource networking, and group meetings. | Kin as Teachers (KAT) aim at meeting the special needs of relative caregivers raising children from birth to kindergarten entry. It addresses the areas of parent knowledge, parenting practices, detection of developmental delays and health issues, prevention of child abuse and neglect, and promotion of school readiness and success. | n/a | 83 caregivers | T-test | Home environment Parent knowledge of child development |

n/a | Improved age-appropriate family environment and an increase in caregivers’ knowledge of child development for families participating in KAT. |

| McCallion, Janicki & Kolomer (2004), | The United States | Grandparents | RCT | Group intervention for caregivers | Caregiver support group: address grandchildren’s needs and take care of themselves such as stress reduction and relaxation. | 6 group sessions; 90 minutes per session | 97 grandparents | T-test, chi-square, and random effect regression model | Depression Empowerment Sense of caregiving mastery |

n/a | Significant reductions in symptoms of depression and increases in the sense of empowerment and caregiving mastery |

| N’zi et al., (2016) | The United States | Kinship caregivers | RCT | Parent-child interaction | Child Directed Interaction Training: address both the mental health needs of young children in kinship care and the parenting needs of their caregivers. | 6 sessions | 14 kinship caregivers | ANCOVA | Depression Parenting stress | Child behavior; Child-parent relationship | Significant fewer child external behavioral problems, more positive interactions, lower total caregiver stress and repression, and positive changes in disciplining. Changes in child internalizing behavioral problems were not detected until 3-month follow-up assessment. |

| Smith, et al (2016) | The United States | Grandmothers | RCT | Group sessions | Project COPE (Caring for Others as a Positive Experience): provide information to help grandmothers get through the difficult job of caring for grandchildren in changing times. Three psychosocial interventions:(a) a behavioral parenting program (BPT), (b) a cognitive behavioral coping program (CBT), or (c) an information-only condition (IOC). | 10 two-hour group sessions | 343 grandmothers | Independent group t-tests, and logistic regression analysis | Depression: Positive affect Social Support Health | Mental health | Positive affect was the only significant enabling factor related to compliance, with compliant participants reporting less positive affect. |

| Smith, et al (2018) | The United States | Grandmothers | RCT | Group sessions | See Smith, et al (2016) | 10 two hour group sessions | 343 grandmothers | Multidomain second-order latent difference score models | Depression: Positive affect Social Support Health | Mental health | When comparing BPT to CBT, no significant differences. When comparing the BPT to IOC, significant reeducation in coercive discipline and ineffective discipline in BPT conditions. When comparing the CBT to IOC, reductions in both children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, coercive discipline and ineffective discipline were greater in the CBT. |

| Strozier, McGrew, Krisman, & Smith (2005) | The United States | Kinship caregivers | Pre-experimental design | School-based and case management program | Kinship Care Connection, an innovative school-based intervention designed to increase children’s self-esteem and to mediate kin caregiver burden. | 8 sessions; 18 weeks | 72 caregivers and 235 children | T-test | Self-efficacy | Self-esteem | Significant increase in caregiver’s self-efficacy and children’s self-esteem |

| Studies that separated kin and non-kin (n = 2) | |||||||||||

| Christenson & McMurtry (2007) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Pre-experimental design | Individual | Parent Resources for Information Development and Education (PRIDE) program is based on five competencies, including protecting and nurturing of children; meeting children’s developmental needs and addressing developmental delays; supporting relationships between children and their families; connecting children to safe, nurturing relationships intended to last a lifetime, and working as members of a professional team. | Two and a half months; nine three-hours sessions | 115 participants | Pre and post t-test | Five competencies for PRIDE program | n/a | Results indicated a significant difference in competencies between kinship and non-kinship participants. The training may not meet all the needs of kinship care providers. |

| Sullivan, Murray & Ake (2016). | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Pre-experimental design | Group sessions | Resource Parenting Curriculum educates parents about the impact of trauma on the development and behaviors of children with experience in foster care or out-of-home placement, and provides resource, knowledge, and skills needed to respond appropriately to their children’s challenging behaviors and emotions. | 7 sessions for up to 2 hours each | 159 participants | Repeated measure s ANOVA s and general linear model | Beliefs and attitudes related to parenting a traumatized child The Trauma-Informed Parenting Tolerance of misbehaviors Parenting efficacy |

n/a | Significant increase in the knowledge of trauma-informed parenting and perceived self-efficacy. Non-kinship caregivers increased on their willingness to tolerate difficult child behaviors, whereas kinship caregivers did not show a significant change. |

| Studies analyzed both kin and non-kin as whole (n = 11) | |||||||||||

| Chamberlain, Price, Reid, & Landsverk (2008) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | RCT | Group intervention for caregivers | Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC): a parenting management training-based approach: increase positive reinforcement; use non-harsh discipline methods. | 16 weeks; 90 minutes per session | 237 kinship caregivers, and 463 non-kin foster parents | T-test | Proportion positive reinforcement | Child behavior problems | Caregivers reported significantly increased positive reinforcement and fewer child behavior problems. |

| Christenson & McMurtry (2009) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Pre-experimental design | Individual | See Christenson & McMurtry (2007) | Two and a half months; nine three-hours sessions | 114 participants | Pre and post t-test | Five competencies for PRIDE program | n/a | Participants showed significant differences in the different competencies in pre-post/post survey and post-post/post evaluations indicated a decrease in competency 1 and 4. |

| Coard, Foy-Watson, Zimmer, & Wallace (2007) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | RCT | Group intervention for caregivers | Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies (BPSS) Program is a cultural adaptation of Parenting the Strong-Willed Child program. It teaches parents skills to deal and prevent problematic behaviors using strength-based methods and strategy specific to the environment of African American families. BPSS also focuses on increasing children’s confidence in school, developing children’s positive image of black children, promoting positive and developmentally appropriate discussions about race and enhancing children’s problem-solving skills. | 12 weeks; 1-hour per session per week | 30 foster families (15 families in the intervention group, and 15 families in the control group) | T-test | Parenting practice: | Children’s emotional, behavioral and social functioning | Families in the intervention group showed a significant increase in positive parenting, racial socialization score, responsibility, and they show decreased in hash discipline, parent-reported children externalizing behavior and cooperation. |

| DeGarmo et al. (2009) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Pre and Posttest for Experimental group in an RCT design | Group intervention for caregivers | Keeping Foster and Kinship Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP): increasing use of positive reinforcement, consistent use of non-harsh discipline methods, and teaching parents the importance of close monitoring of the youngster’s whereabouts and peer associations. In addition, strategies for avoiding power struggles, managing peer relationships, and improving success at school were also included. | 16 weeks | 337 caregivers nested in 59 intervention groups consisting of 3 to 10 foster parents | Hierarchical linear modeling | n/a | Child behavior problems: Negative placement disruption for children exiting the home | Caregiver engagement moderated the effects of the number of prior placements on the increase of child problem behaviors, and moderates the risks of negative placement disruption for Hispanics. |

| Greeno, et al (2016a) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Pre-experimental design | Group sessions | See DeGarmo (2009) | 16 weeks; 90 minutes per session | 75 participants | Paired t-test | Discipline techniques | Behavioral and emotional problem Permanency Placement stability | Child behavioral problems were significantly decreased, and placement stability was significantly increased. However, there were not many changes in parenting styles. |

| Greeno, et al (2016b) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Quasi-experimental design | Group sessions | See DeGarmo (2009) | 16 weeks; 90 minutes per session | 113 participants (Intervention group: 65; control group: 48) | Repeated measure s ANOVA s and independent t-test | Stress: Discipline techniques: | Behavioral and emotional problem Permanency | Child behavioral problems were significantly decreased and placement stability was significantly increased. However, there were not significant changes in parenting styles and permanency outcomes |

| Pasalich, Fleming, Oxford, & Zheng (2016) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | RCT | Home visits | Promoting First Relationship uses reflective practice principals to focus on the deeper emotional needs and the underlying difficulties in the parent and toddler relationship to help caregivers think about their toddler’s developing mind. | Ten weekly 60–75-minute-long home visit sessions | 210 toddlers and their caregive1rs | Conditional process analysis | n/a | Number of placement change Problem behavior Attachment security |

The significant negative association between placement changes and attachment security in the control condition (not in the intervention group); The conditional indirect effect of placement changes on externalizing problems via attachment security was significant in the control group (not in intervention group). |

| Price et al., (2008). | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | RCT | Group intervention | See DeGarmo (2009) | 16 weeks | 700 foster families | The positive exit hazard model | n/a | Placement status | The number of prior placement significantly predicted a higher negative exist hazard rate in the control group. The foster parent intervention mitigated the negative risk-enhancing effect of a history of multiple placements. |

| Price, Roesch, & Walsh (2012). | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | Quasi-experimental design | Group intervention | See DeGarmo (2009) | 16 weeks | Intervention group: 359 caregivers; control group: 341 caregivers | ANOVA, Chi-square analysis, Hierarchical linear regression, and simple slop analysis | n/a | Child behavior problems | Significant reduction in behavioral problems for children |

| Spieker, et al. (2012) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | RCT | Home visits | See Pasalich, Fleming, Oxford, & Zheng (2016) | Ten weekly 60–75-minute-long home visit sessions | 210 toddlers and their caregivers | ANCOV A, Hierarchical Linear Modeling | Sensitivity Support Commitment Parenting stress | Attachment security Engagement Competence and problem behavior |

Caregiver understanding of toddlers’ social-emotional needs and caregiver reports of child competence differed by intervention condition. Significant improvement in caregivers’ sensitivity and understanding of toddlers. |

| Spieker, Oxford, & Fleming (2014) | The United States | Kin and non-kin mixed | RCT | Home visits | See Pasalich, Fleming, Oxford, & Zheng (2016) | Ten weekly 60–75-minute-long home visit sessions | 210 toddlers and their caregivers | Logistic regression intent to treat models | n/a | Stability permanency | No significant differences in stability or permanency. A significant interaction between caregiver type and intervention group. More foster/kin caregivers who received the intervention provided stable, uninterrupted care and eventually adopted or became the legal guardians of the toddlers. |

3. Results

3.1. Research Methods

Research designs.

The identified studies used various research designs to examine intervention effects. As shown in Table 1, 13 (46.4%) studies used randomized control trials (RCT) to examine intervention effects. Two (7.2%) studies used quasi-experimental designs, and 13 (46.4%) studies used pre-experimental design (pre- and post-intervention surveys). Among the 17 studies that have data specific to kin caregivers, 10 (58.8%) studies used pre-experimental design, and seven (41.2%) studies used RCT to examine the intervention effect.

Sample sizes.

Sample sizes ranged from five to 700 participants. Seven studies (25%) had a sample of less than 50 participants, six studies (21.4%) had a sample size between 50 and 100 participants, seven studies (25%) had a sample of 100–300 participants, five studies (17.9%) had a sample size between 301–500 participants, and three studies (10.7%) had a sample size between 501–700 participants. Only one study (Kicklighter et al., 2009) limited its sample to African American caregivers. Four studies limited their samples to only female caregivers or grandmothers (Kelley et al., 2010; Kicklighter et al., 2009; Smith, Strieder, Greenberg, Hayslip, & Montoro-Rodriguez, 2016; Smith, Hayslip, Hancock, Strieder, & Montoro-Rodriguez, 2018).

Sample sizes were relatively small in the 17 studies in which kinship effects could be distinctly determined. Specifically, five studies (29.4%) had a sample of less than 50 participants, six studies (35.3%) had a sample size between 50 and 100, two studies (11.8%) had a sample of 100–300, two studies (11.8%) between 301–500, and only one study (5.9%) had a sample size between 501–700 (see Table 1).

Statistical methods.

As shown in Table 1, the most commonly used statistical method for assessing effect was the t-test for both the entire sample of 28 studies (n = 14; 50%) and the sub-sample of 17 studies in which kinship effects were separately assessed (n = 9; 52.9%). T-test was used in five out of 13 (38%) RCT studies, in one out of two quasi-experimental studies with a comparison group, and in nine out of 13 pre-experimental design studies. Other common statistical methods used in the 28 studies were ANOVA or repeated measures ANOVA (n = 5), Chi-square (n = 4), Hierarchical Linear Modeling (n = 3), and ANCOVA (n = 3). In addition, the following statistical methods were used: Positive Exit Hazard Model (Price et al., 2008), Random Effect Regression Model (McCallion et al., 2004), Logistic Regression (Spieker, Oxford, & Fleming, 2014), Conditional Process Analysis (Pasalich, Fleming, Oxford, Zheng, & Spieker, 2016), and Multidomain Second-order Latent Difference Score Models (Smith et al., 2018). Two studies used only descriptive analysis because of small sample sizes (Duquin et al., 2004; Kicklighter et al., 2009).

3.2. Overview of Interventions

Targets and characteristics of interventions.

In terms of the target population of the interventions, about half of the 28 studies focused (n=13) on both kinship and non-kinship foster parents, and the other half (n=15) on kinship parents only. Eight of the 15 studies that only targeted kinship parents focused on grandparents. Two studies targeted both kin and non-kin, but in a manner in which the two were separated. The number of intervention sessions ranged from six (Kirby & Sanders, 2014; McCallion et al., 2004; N’zi et al., 2016) to 10 (Smith et al., 2018), and the length of the interventions ranged from 9 weeks (Kriby & Sanders, 2014) to 12 months (Kelley et al., 2010) (See Table 1).

As to intervention settings or formats, 17 (61%) studies examined those delivered via group sessions/meetings, seven (25%) delivered through family home visits, and three in the form of case management programs. In addition, Christenson and his colleagues (Christenson & McMurtry, 2007; Christenson & McMurtry, 2009) examined interventions targeting individual caregivers, and N’zi et al. (2016) examined an intervention that focused on parent-child interactions. Some studies (Kelley et al., 2001; Kelley et al., 2010; Kriby & Sanders, 2014; Littlewood et al., 2014) examined interventions delivered in a combination of group meetings, home visits, and support services (See Table 1). The 17 kinship studies that have data specific to kin caregivers showed a similar pattern of intervention format: group session is the most common (n = 8), following by case management (n = 3), home visit (n = 2), combination of home visits and group sessions (n = 2), parent and child interaction (n = 1), and individual session (n = 1).

Contents of intervention.

A summary of contents of the interventions can be found in Table 1. Overall, the identified interventions aimed to improve caregivers’ parenting skills and their relationship with the cared for children. Interventions were developed from various perspectives, such as building parenting skills, facilitating access to resources and supports, promoting trauma-focused interventions, and improving caregivers’ health and nutrition. The most commonly used intervention strategy (n= 5) was Keeping Foster and Kinship Parents Trained and Supported (KEEP; DeGarmo, 2009; Greeno et al., 2016a; Greeno et al., 2016b; Price et al., 2008; Price et al., 2012). It was developed to help improve foster caregivers’ parenting skills so that they can better manage the child’s challenging behavior problems, reduce parenting stress, and prevent placement disruptions (Greeno et al., 2016b; Price et al., 2008). Similarly, Kelley and colleagues (Kelley et al., 2001; Kelley et al., 2010) developed a home-based intervention aimed to increase caregivers’ parenting competence and reduce their psychological stress. Project COPE (Caring for Others as a Positive Experience) is a knowledge-based intervention to help grandparents take care of grandchildren in their transition by building their parenting skills (Smith et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2018). Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care (MTFC) is another intervention strategy that focuses on specific parenting skills, such as positive reinforcement and non-harsh discipline methods (Chamberlain et al., 2008). Kin as Teachers (KAT) more specifically focused on educating kin caregivers in parenting knowledge and skills to raise children from birth to kindergarten (Littlewood et al., 2014).

Some interventions tried to alleviate caregivers’ burdens through improving child capacities. For example, Kinship Care Connection was a school-based intervention that focuses on promoting child self-esteem as a strategy to reduce caregiver stress (Strozier et al., 2005). Some interventions (Pasalich et al., 2016; Spieker et al., 2012; Spieker et al., 2014), such as the Promoting First Relationship program, focused on improving the relationship between caregivers and the cared for children.

Several interventions focused on meeting the needs of caregivers, such as facilitating access to relevant services, or strengthening social support systems. These interventions included, 1) Kinship Navigation Program (Feldman & Fertig, 2013), which provides assistance and referral to families based on their needs, parent support and education groups, and children’s groups to enhance social support; 2) Grandparent Triple P program (Kriby & Sanders, 2014; Leung et al., 2014), which includes the use of positive parenting strategies, building a positive-parenting team, and coping with negative emotions. 3) Caregiver Support Group (McCallion et al., 2004), which addresses grandchildren’s needs, and helps them with stress reduction and relaxation; 4) Parent Resources for Information Development and Education (PRIDE) program (Christenson & McMurtry, 2007; Christenson & McMurtry, 2009), which includes protecting and nurturing children; meeting children’s developmental needs and addressing developmental delays; supporting relationships between children and their families; connecting children to safe, nurturing relationships intended to last a lifetime; and working as members of a professional team; 5) System of Care Case Management Model (Campbell et al., 2012), which is a family-centered, strength- and empowerment-based program designed to enhance the well-being and successful functioning of custodial grandparents and their grandchildren; and 6) Child Directed Interaction Training (N’zi et al., 2016), which addresses the mental health needs of young children and the parenting needs of their caregivers.

Two studies examined parenting interventions that adopted a trauma-informed perspective. Foli et al. (2018) examined an intervention which used trauma-informed parenting classes to educate caregivers about child trauma experiences so that they could provide care that better meets the child’s needs. Sullivan et al. (2016) used the Resource Parenting Curriculum to educate caregivers about the impact of trauma on children’s behaviors and development so that caregivers were better equipped to respond to child’s challenging behaviors and emotions.

Two interventions (Duquin et al., 2004; Kicklighter et al., 2009) included information on health, exercise, or nutrition to meet the needs of the developing child. Many social risk factors related to child development are overrepresented among African Americans families. The Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies Program, described by Coard et al. (2007), is a cultural adaptation of the Parenting the Strong-Willed Child Program to address the unique strengths, needs, and strategies in African American foster care families.

3.3. Effectiveness of the Interventions

The studies presented below review the effectiveness of parenting interventions on caregivers’ parental and child outcomes. More detailed information regarding the measures of outcomes and study findings can be found in Table 1.

3.3.1. Caregiver Outcomes

Twenty-two out of 28 identified studies (79%) examined a total of more than 20 parenting related caregiver outcomes, such as positive reinforcement, parenting practice, family needs, social support, stress, parenting confidence, depression, grandparent-parent communication or relationship adjustment, sensitivity, commitment, health, discipline techniques, quality of life, competencies, knowledge of child development, strengths and difficulties, self-efficacy or parenting efficacy, nutrition and physical activity knowledge, belief and attitudes related to parenting a traumatized children, and the tolerance of misbehavior. The 17 studies in which kinship effects were separately assessed also covered all the above caregiver outcomes. One study (Smith et al., 2016) examined the factors associated with the intervention compliance and satisfaction, but it also assessed caregiver outcomes.

Among the 22 studies that examined intervention effects on caregivers’ outcomes, 15 studies reported that participants showed significant improvement in parenting skills (Chamberlain et al., 2008; Coard et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2018), an increase on parenting knowledge (Littlewood, Strozier, & Whittington, 2014; Spieker et al., 2012), an increase in self-confidence or efficacy (Kirby & Sanders, 2014; Strozier et al., 2005), and a decrease in parenting stress or depression (Campbell et al., 2012; Kelley et al., 2001; Kirby & Sanders, 2014; Leung et al., 2014; McCallion et al., 2004; N’zi et al., 2016). Among the 17 studies in which kinship was distinguished in analysis, 11 studies showed positive intervention effects (see Table 1).

Four studies that targeted kin caregivers found mixed results in caregiver outcomes. Specifically, Kelley et al (2010) found that the mean scores of health attributes for intervention participants increased significantly, but there was no effect on physical functioning, general health, and social functioning. Sullivan et al (2016) reported that the Resource Parenting Curriculum significantly improved caregiver knowledge of trauma-informed parenting and self-efficacy, but it had no effect on caregivers’ toleration of difficult child behaviors. Foli et al (2018) used both quantitative and qualitative analysis to examine outcomes. The quantitative data did not support the improvement of caregiver outcomes, but the qualitative data supported the overall positive impact of the intervention. Kicklighter et al (2009) found that grandparent’s nutrition, physical activity knowledge, and self-efficacy were improved after participating in the intervention, but most health status indicators remained unchanged.

Intervention failed to have a significant impact on specific caregiver outcomes in the following five studies: the enhanced Kinship Navigation Program and social support and stress (Feldman & Fertig, 2013), the KEEP program and parenting styles (Greeno et al., 2016a; 2016b), and the PRIDE program and parenting competence (Christenson & McMurtry, 2007; 2009). Two of the five studies (Christenson & McMurty, 2007; Feldman & Fertig, 2013) focused on kin caregivers. In total, six out of 17 (35.3%) kinship studies showed mixed results or non-significant intervention impact.

3.3.2. Child Outcomes

Eighteen (64%) of the studies examined the impact of parenting interventions on the following child outcomes: child behavior problems (e.g, Chamberlain et al., 2008; Feldman & Fertig, 2013; Kirby & Sanders, 2014), child-parent relationships (N’zi et al., 2016), placement stability (DeGarmo, 2009; Greeno et al., 2016a; Pasalich et a., 2016; Price et al., 2008; Spieker et al., 2014), permanency (Greeno et al., 2016a; Greeno et al., 2016b; Spieker et al., 2014), and self-esteem (Strozier et al., 2005). The most common child outcomes were child behavior problems (n = 13), while only one study (Strozier et al., 2005) examined child self-esteem, and it noted a significant positive impact of parenting intervention.

Although most of the interventions in the reviewed studies showed a positive effect on child outcomes, several interventions showed partial or less promising outcomes (see Table 1). For the System of Care case management model, children in the intervention group reported fewer child external behavioral and emotional problems, but not internalized behaviors (Campbell et al., 2012). The enhanced Kinship Navigation Program showed no significant differences in child behavior problems between the intervention and comparison groups (Feldman & Fertig, 2013). The Promoting First Relationship program also did not show an impact on placement stability and permanency (Spieker et al., 2014).

Among the 17 studies in which kinship effects were distinguishable, about half (n = 9) did not examine the intervention impacts on child outcomes. Among the eight studies that examined child outcomes, five studies looked at the impacts on child behavior problems, but they showed different findings. For example, two studies found that the parenting interventions resulted in a significant decrease in child behavior problems (Kirby & Sanders, 2014; Leung, Sanders, & Kriby, 2014). However, two studies found that although the interventions had impacts on child externalized behaviors, they did not show an impact on child internalized behaviors (Campbell et al., 2012; N’zi et al., 2016). Feldman & Fertig (2013) found that their parenting intervention did not have a significant impact on child behavior problems. Two studies (Smith et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2018) found significant intervention effects on mental health, and one (Strozier et al., 2005) on self-esteem.

3.4. Results from the RCT studies

Most (n = 12; 92.3%) of the RCT studies (i.e., studies with the most rigorous designs) reported significant results regarding improvements in child behavior problems and placement stability, and caregiver parenting and functioning. RCT studies with positive child and caregiver outcomes involved group interventions (n = 8; 66.7%), home visits (n = 3; 25%), and parent-child interaction (n = 1; 8.3%). However, the RCT study conducted by Feldman and Fertig (2013) found no significant improvements in caregivers’ social support, stress, or child behavior problems comparing kinship caregivers who received enhanced case management plus referral services to kinship caregivers who received services-as-usual.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results

This systematic review of studies evaluating kinship parenting interventions on both caregiver and child outcomes should help practitioners to improve the outcomes of child welfare-involved children and their families. Given that kin caregivers usually have a high level of stress compared to parent caregivers (Lee, Clarkson-Hendrix, & Lee, 2016) or non-kin caregivers (Leder, Grinstead, & Torres, 2007), one of the important aims for parenting intervention is to decrease parenting stress (Fisher & Stoolmiller, 2008). The identified studies in this review examined the intervention effects on parenting stress and other related parenting outcomes, such as parenting knowledge and attitude, mental and physical health, and social support. The majority of the identified studies found that intervention has significant positive effects on these parenting outcomes.

Several studies had multiple and varied parenting outcomes, so intervention could be effective on one outcome, but not on others (e.g. Kelley et al., 2010; Sullivan et al., 2016). For example, the PRIDE program shows significant impacts on particular caregiver competencies, but the training may not meet all the needs of kin caregivers (Christenson & McMurty, 2007; 2009). In addition, two studies (Kelley, Whitley, Campos, 2010; Kicklighter et al., 2009) provided interventions to grandparents and found significant improvement on nutrition and self-efficacy. However, both of the studies found their general health remained unchanged, perhaps because grandparents are usually older than other kin caregivers and multiple factors affect their health condition. These findings indicate that meeting all the needs of kin caregivers, or improving all the parenting related outcomes, is challenging for parent interventions. Results may also differ due to the use of different methods. For example, the results in Foli et al’ study (2018) differed depending on whether quantitative data or qualitative data were used in analysis. We should understand the results of a given study in a more comprehensive way, rather than simply conclude that an intervention is effective or not.

Although interventions are generally designed for caregivers, several studies examined intervention effects on child outcomes, with child behavior being the most common. Caregiver functioning and child behavioral health are interrelated. Behavior problems may increase caregiver stress making it difficult to positively parent, and this may negatively affect child behavioral health (Washington et al., 2018). For example, several of the studies in our review, as in Washington et al’s (2018), indicate that the KEEP intervention effectively decreases child behavior problems, although it has mixed results in terms of affecting parenting style.

4.2. Limitations of the literature and future directions

Overall, the identified studies showed promising intervention effects on caregiver and child outcomes. However, several limitations of the literature should be noted, which could point out the future directions for research. First, of the 1,047 articles captured in our search, we identified only 28 (2.67%) studies meeting the inclusion criteria, and most of these (93%) were conducted in the United States. By conducting more international intervention studies, researchers will have to design and evaluate interventions in a culturally adapted manner, which should advance our overall understanding of intervention effectiveness. Several studies were considered as not meeting inclusion criteria because they focused on kinship caregiver’s stress, simply described an intervention, and/or used qualitative methods. The small percentage of articles meeting our inclusion criteria suggests a need for additional rigorous empirical research examining the impact of kinship parenting interventions. More research using RCT would generate data with greater strength of inference, and thus further our understanding of whether and which kinship parenting interventions are effective in producing their desired outcomes.

Second, two of the eight grandparent studies focused solely on grandmothers, but none focused on grandfathers. Relatedly, none of the studies distinguished whether outcomes varied depending on caregivers’ gender. Although female caregivers or grandmothers are likely the primary kinship caregivers in a household (Denby et al., 2014), those in the father role (e.g., grandfathers and uncles) should not be ignored. Kinship caregivers in the role of a father may have to deal with different parenting challenges than those in the role of a mother. For example, prior studies have found significant differences between grandfathers and grandmothers, including depressive symptoms (Kolomer & McCallion, 2005; Okagbue-Reaves, 2006), physical health, income, and length of time living with grandchildren (Okagbue-Reaves, 2006). Thus, researchers should determine if the outcomes of current interventions targeting kinship caregivers differ by caregivers’ gender. If so, it may be necessary to adapt such interventions to meet the different needs of male and female kinship caregivers.

Third, very few studies were race/ethnicity specific. We found only one reviewable study that targeted kinship caregivers based on their race/ethnicity (Coard, Foy-Watson, Zimmer, & Wallace, 2007). This study, which examined the BPSS Program for African American grandparents, found significant improvements in parenting and child behavior outcomes, as well as racial socialization. Race-specific parenting interventions for African American kinship caregivers are important because they are disproportionately involved with child welfare. African American children made up 14% of the United States population in 2018 (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2019), and they represented 23% of children in foster care (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). Further, most kinship caregivers are African American (N’zi, Stevens, & Eyberg, 2016). Although the BPSS program is promising, there is a need for more parenting interventions that are race and culture focused, as minority face unique risks and challenges.

Fourth, although promising results were present among studies that focused on both kinship and non-kinship foster parents, it is often impossible to disentangle kinship caregiver outcomes from those of non-kinship caregivers. Further, we found only two studies (Christenson & McMurtry, 2009; Sullivan et al., 2016) that separated the results by caregiver type (kinship vs. non-kinship caregivers). Both studies found improvements in parenting outcomes, but only among non-kinship caregivers. Therefore, this suggests there may be a need to create separate interventions for kinship versus non-kinship caregivers. Although these two groups may share similar parenting challenges, kinship caregivers face unique challenges. They are subjected to additional stress related emotional conflict with the birth parent(s) over custody and level of parental involvement (Kelly & Danato, 1995; Leathers & Testa, 2006). These challenges may vary even more depending on whether the kinship placement arrangement is formal or informal. Additional research is warranted to understand such nuances, so future research should design and evaluate parenting interventions specific for formal or informal kin caregivers.

4.3. Limitations of the Current Study

The findings of this systematic review should be interpreted with several limitations in mind, including potential publication bias, reviewer bias, and overlapping samples and authors among studies. First, this review included only research published in peer-reviewed journals. It is possible that there is an over-reporting of positive results, as studies with more negative results are less likely to be published. Future systematic reviews on this topic should assess the grey literature. Second, although efforts, such as cross-validation in study inclusion and data extraction by two researchers, were taken to reduce selection and appraisal bias, these risks still exist. It is also possible that we missed relevant articles due to the selected search terms and databases. However, based on the extensiveness of the searched databases as well as study identification through references of included papers, we believe the chance of missing relevant articles is minimal. Third, the interventions (e.g., contents, formats, and session durations) and measured outcomes varied substantially across the reviewed studies. Although this suggests a flexibility in designing specialized parenting interventions, it made the effects less comparable across studies. Given the complexity of intervention contexts and targeting goals, we cannot determine which intervention may be most effective. However, we provide a great deal of information regarding each intervention (see Table 1) which should be useful when considering the application and development of parenting intervention.

5. Conclusion

This study systematically reviewed the research methods and findings concerning the effects of parenting interventions related to kinship foster care families. It provides meaningful information about the outcomes of evidence -based parenting intervention for kinship caregivers. We found a small percentage of articles meeting inclusion criteria and most studies were conducted in the United States. Thus, additional research examining the impact of kinship parenting interventions is warranted, particularly in countries outside of the United States. Additionally, findings from this study highlight the need for future research that targets male kinship caregivers (e.g., grandfathers), and for research that is designed for specific ethnic/racial groups. Evaluation studies with more rigorous research design (e.g. RCT) should be conducted in the future as well. Researchers studying kinship parenting interventions should also distinguish between effects of interventions on kinship versus non-kinship foster caregivers. Addressing these gaps in knowledge will advance our knowledge of intervention outcomes, and aid in guiding child welfare policy and practice decisions. Nonetheless, overall results of findings included in this review revealed positive child and kinship caregiver outcomes. Thus, there are promising parenting interventions for kinship caregivers. Child welfare policies and programs should aim to improve parenting and caregiver and child functioning using these promising evidence-based interventions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

* Asterisks indicate studies that were included in the systematic review.

- Adoption and Safe Families Act. (1997). Pub. L. No. 105–89. [Google Scholar]

- Annie E Casey Foundation. (2012). Kids count data book. Retrieved from http://www.aecf.org/*/media/Pubs/Initiatives/KIDS%20COUNT/123/2012KIDSCOUNTDataBook/KIDSCOUNT2012DataBookFullReport.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Annie E Casey Foundation. (2019). Kids count data book. Retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/103-child-population-by-race#detailed/1/any/false/37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38/68,69,67,12,70,66,71,72/423,424 [Google Scholar]

- Beeman SK, Kim H, & Bullerdick SK (2000). Kinship family foster care: A methodological and substantive synthesis of research. Children and Youth Services Review, 22(1), 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Blome W, Shields J, & Verdieck M (2009). The association between foster care and substance abuse risk factors and treatment outcomes: An exploratory secondary analysis. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 18, 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Bunch SG, Eastman BJ, & Griffin LW (2007). Examining the perceptions of grandparents who parent in formal and informal kinship care. Journal of Human Behavior and in the Social Environment, 15(4), 93–105. [Google Scholar]

- *Campbell L, Carthron DL, Miles MS, & Brown L (2012). Examining the effectiveness of a case management program for custodial grandparent families. Nursing Research and Practice, 2012, 124230 10.1155/2012/124230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau US (2016). America’s families and living arrangements: 2016: Children (C table series). Washington, DC: Author; Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2016/demo/families/cps-2016.html. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve L, Heidemarie L, Landsverk J, & Reid J (2008). Prevention of behavior problems of children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science, 9, 17–27. 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, & Landsverk J (2008). Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare, 87(5), 27–48. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19402358 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Child Welfare League of America. (1994). Kinship care: A natural bridge. Washington, D.C.: Child Welfare League of America. [Google Scholar]

- *Christenson B, & McMurtry J (2007). A comparative evaluation of preservice training of kinship and nonkinship foster/adoptive families. Child Welfare, 86(2), 125–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Christenson BL, & McMurtry J (2009). A longitudinal evaluation of the preservice training and retention of kinship and nonkinship foster/adoptive families one and a half years after training. Child Welfare, 88(4), 5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Coard S, Foy-Watson S, Zimmer C, & Wallace Amy (2007). Considering culturally relevant parenting practices in intervention development and adaptation: A randomized controlled trial of the Black Parenting Strengths and Strategies (BPSS) Program. Counseling Psychologist, 35(6), 797–820. Retrieved from http://10.0.4.153/0011000007304592 [Google Scholar]

- Cuddeback GS (2004). Kinship and family foster care: A methodological substantive synthesis of research. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 623–639. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddeback GS, & Orme JG (2001). Training and services for kinship and non-kinship foster families. Child Welfare, 81(6), 879–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *DeGarmo DS, Chamberlain P, Leve LD, & Price J (2009). Foster parent intervention engagement moderating child behavior problems and placement disruption. Research on Social Work Practice, 19(4), 423–433. 10.1177/1049731508329407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332. [Google Scholar]

- Denby R, Brinson J, Cross C, & Bowmer A (2014). Male kinship caregivers: Do they differ from their female counterparts? Children and Youth Services Review, 46, 248–256. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, & Sawyer R (1994). School behavior of children in kinship care. Child Abuse and Neglect, 18, 899–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Duquin M, McCrea J, Fetterman D, & Nash S (2004). A faith-based intergenerational health and wellness program. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 2(3/4), 105–118. http://10.0.5.20/J194v02n03_09 [Google Scholar]

- Ehrle J, & Geen R (2002). Kin and non-kin foster care – Findings from a national survey. Children and Youth Services Review, 24(1/2), 15–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RR, & Simmons T (2014). Coresident grandparents and their grandchildren: 2012. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, Bureau of the Census. [Google Scholar]

- *Feldman LH, & Fertig A (2013). Measuring the impact of enhanced kinship navigator services for informal kinship caregivers using an experimental design. Child Welfare, 92(6), 41–62. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26030980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, & Stoolmiller M (2008). Intervention effects on foster parent stress: Associations with child cortisol levels. Development and Psychopathology, 20(03), 1003–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoption Act (2008). Pub. L. No. 110–351. [Google Scholar]

- Frame L, Berrick JD, & Brodowski ML (2000). Understanding reentry to out-of-home care for reunified infants. Child Welfare, 79(4), 339−369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Foli KJ, Woodcox S, Kersey S, Zhang L, & Wilkinson B (2018). Trauma-informed parenting classes delivered to rural kinship parents: A pilot study. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 24(1), 62–75. 10.1177/1078390317730605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geen R (2003a). Kinship care: Paradigm shift or just another magic bullet? In Geen R (Ed.), Kinship care: Making the most of a valuable resource (pp. 231–260). Washington, DC: Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard JM, Landry-Meyer L, & Roe JG (2006). Grandparents raising grandchildren: The role of social support in coping with caregiving challenges. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 62(4), 359–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JP, Wesley JM, Ellis R, Seryak C, Talley GW, & Robinson J (2009). Becoming involved in raising a relative’s child: Reasons, caregiver motivations and pathways to informal kinship care. Child & Family Social Work, 14, 300–310. 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00596.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson JP, Hsieh CM, & Cryer-Coupet Q (2016). Social support, family competence, and informal kinship caregiver parenting stress: The mediating and moderating effects of family resources. Children and Youth Services Review, 67, 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CC, & Silverstein M (2001). Grandmothers who parent their grandchildren: An exploratory study of close relations across three generations. Journal of Family Issues, 22, 557–578. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman CC, Potts M, Pasztor EM, & Scorzo D (2004). Grandmothers as kinship caregivers: Private arrangements compared to public child welfare oversight. Children and Youth Services Review, 26, 287–305. [Google Scholar]

- *Greeno EJ, Uretsky MC, Lee BR, Moore JE, Barth RP, & Shaw TV (2016a). Replication of the KEEP foster and kinship parent training program for youth with externalizing behaviors. Children & Youth Services Review, 61, 75–82. Retrieved from http://10.0.3.248/j.childyouth.2015.12.003 [Google Scholar]

- *Greeno E, Lee B, Uretsky M, Moore J, Barth R, & Shaw T (2016b). Effects of a foster parent training intervention on child behavior, caregiver stress, and parenting style. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 25(6), 1991–2000. Retrieved from http://10.0.3.239/s10826-015-0357-6 [Google Scholar]

- Harden BJ, Clyman RB, Kriebel DK, & Lyons ME (2004). Kith and kin care: Parental attitudes and resources of foster and relative caregivers. Children and Youth Services Review, 26(7), 657–671. [Google Scholar]

- Harris MS, & Skyles A (2008). Kinship care for African American children: Disproportionate and disadvantageous. Journal of Family Issues, 29(8), 1013–1030. doi: 10.1177/0192513x08316543 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hegar RL, & Scannapieco M (2005). Kinship care: Preservation of the extended family In Mallon GP, & Hess PM (Eds.). Child welfare for the 21st century: A handbook of practices, policies, and programs (pp. 382–400). New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hussey DL, & Guo S (2003). Measuring behavior change in young children receiving intensive school-based mental health services. Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 629–639. [Google Scholar]

- Kolomer SR, & McCallion P (2005). Depression and caregiver mastery in grandfathers caring for their grandchildren. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 60, 283–295. doi:10.2190%2FK8RJ-X0AL-DU34-9VVH [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller T, Wetherbeck K, LeProhn NS, Payne V, Sim K, & Lamont E (2001). Competencies and problem behaviors of children in family foster care: Variations by kinship placement status and child race. Children and Youth Services Review, 23, 915–940. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ (1993). Caregiver stress in grandparents raising grandchildren. Image – The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 25(4), 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly SJ, & Danato EG (1995). Grandparents as primary caregivers. Maternal and Child Nursing, 20, 326–332. doi: 10.1097/00005721-199511000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kelley SJ, Yorker BC, Whitley DM, & Sipe TA (2001). A multimodal intervention for grandparents raising grandchildren: Results of an exploratory study. Child Welfare, 80(1), 27–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, Campos PE, SJ K, DM W, & PE C (2010). Grandmothers raising grandchildren: Results of an intervention to improve health outcomes. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42(4), 379–386. 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01371.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley DM, & Campos PE (2011). Behavior problems in children raised by grandmothers: The role of caregiver distress, family resources, and the home environment. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2138–2145. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.06.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley SJ, Whitley D, Sipe TA, & Yorker BC (2000). Psychological distress in grandmother kinship care providers: The role of resources, social support, and physical health. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(3), 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kicklighter JR, Whitley DM, Kelley SJ, Lynch JE, & Melton TS (2009). A home-based nutrition and physical activity intervention for grandparents raising grandchildren: A pilot study. Journal of Nutrition for the Elderly, 28(2), 188–199. 10.1080/01639360902950224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kirby JN, & Sanders MR (2014). A randomized controlled trial evaluating a parenting program designed specifically for grandparents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 52(1), 35–44. 10.1016/j.brat.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh E (2010). Permanency outcomes of children in kinship and non-kinship foster care: Testing the external validity of kinship effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(3), 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Kortenkamp K, & Ehrle J (2002). The well-being of children involved with the child welfare system: A national overview. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Leathers SJ & Testa MF (2006). Foster youth emancipating from care: Caseworker’ reports on needs and services. Child Welfare, 85, 463–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leder S, Grinstead LN, & Torres E (2007). Grandparents raising grandchildren: Stressors, social support, and health outcomes. Journal of Family Nursing, 13(3), 333–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee E, Clarkson-Hendrix M, & Lee Y (2016). Parenting stress of grandparents and other kin as informal kinship caregivers: A mixed methods study. Children and Youth Services Review, 69, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- * Leung C, Sanders M, Fung B, & Kirby J (2014). The effectiveness of the Grandparent Triple P program with Hong Kong Chinese families: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Family Studies, 20(2), 104–117. 10.1080/13229400.2014.11082000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C (2018). The relationships between child well-being, caregiving stress, and social engagement among informal and formal kinship care families. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- *Littlewood KA, Strozier AL, & Whittington D (2014). Kin as Teachers: An early childhood education and support intervention for kinship families. Children and Youth Services Review, 38, 1–9. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.11.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marinkovic JA, & Backovic D (2007). Relationship between type of placement and competencies and problem behavior of adolescents in long-term foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 29(2), 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Massinga R, & Pecora PJ (2004). Providing better opportunities for older children in the child welfare system. Children, Families, and Foster Care, 14(1), 151–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McCallion P, Janicki MP, & Kolomer SR (2004). Controlled evaluation of support groups for grandparent caregivers of children with developmental disabilities and delays. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 109(5 CC-SR-BEHAV CC-Child Health CC-Complementary Medicine), 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin B, Ryder D, & Taylor MF (2017). Effectiveness of interventions for grandparent caregivers: A systematic review. Marriage & Family Review, 53(6), 509–531. 10.1080/01494929.2016.1177631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse L (2005). Information packet: health care issues for children in kinship care. Retrieved November 30, 2013, from http://www.hunter.cuny.edu/socwork/nrcfcpp/downloads/information_packets/Health_Care_Issues_for_Children_in_Kinship_Care.pdf [Google Scholar]

- N’zi A, Stevens M, & Eyberg S (2016). Child Directed Interaction Training for young children in kinship care: A pilot study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 55, 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *N’zi AM, Stevens ML, Eyberg SM, N’zi AM, Stevens ML, Eyberg SM, … Eyberg SM (2016). Child Directed Interaction Training for young children in kinship care: A pilot study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 55, 81–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okagbue-Reaves J (2006). Kinship care: Analysis of the health and well-being of grandfathers raising grandchildren using the grandparent assessment tool and the medical outcomes trust SF-36 tm health survey. Journal of Family Social Work, 9, 47–66. doi: 10.1300/J039v09n02_03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (1996). Pub. L. No. 104–193. [Google Scholar]

- *Pasalich DS, Fleming CB, Oxford ML, Zheng Y, & Spieker SJ (2016). Can parenting intervention prevent cascading effects from placement instability to insecure attachment to externalizing problems in maltreated toddlers? Child Maltreatment, 21(3), 175–185. 10.1177/1077559516656398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Price JM, Chamberlain P, Landsverk J, Reid JB, Leve LD, & Laurent H (2008). Effects of a foster parent training intervention on placement changes of children in foster care. Child Maltreatment, 13(1), 64–75. 10.1177/1077559507310612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Price JM, Roesch S, Walsh NE, & Landsverk J (2012). Effects of the KEEP foster parent intervention on child and sibling behavior problems and parental stress during a randomized implementation trial. Prevention Science : The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 16(5), 685–695. 10.1007/s11121-014-0532-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal JA, & Curiel HF (2006). Modeling behavioral problems of children in the child welfare system: Caregiver, youth, and teacher perceptions. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 1391–1408. [Google Scholar]

- *Smith GC, Strieder F, Greenberg P, Hayslip B Jr, & Montoro-Rodriguez J (2016). Patterns of enrollment and engagement of custodial grandmothers in a randomized clinical trial of psychoeducational interventions. Family Relations, 65(2), 369–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Smith GC, Hayslip B, Hancock GR, Strieder FH, & Montoro-Rodriguez J (2018). A randomized clinical trial of interventions for improving well-being in custodial grandfamilies. Journal of Family Psychology : JFP : Journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 32(6), 816–827. 10.1037/fam0000457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]