Abstract

Background

In the absence of a vaccine or treatment, the most pragmatic strategies against an infectious disease pandemic are extensive early detection testing and social distancing. This study aimed to summarize public and workplace responses to Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) and show how the Korean system has operated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method

Daily briefings from the Korean Center for Disease Control and the Central Disaster Management Headquarters were assembled from January 20 to May 15, 2020.

Results

By May 15, 2020, 11,018 COVID-19 cases were identified, of which 15.7% occurred in workplaces such as health-care facilities, call centers, sports clubs, coin karaoke, and nightlife destinations. When the first confirmed case was diagnosed, the Korean Center for Disease Control and Central Disaster Management Headquarters responded quickly, emphasizing early detection with numerous tests and a social distancing policy. This slowed the spread of infection without intensive containment, shut down, or mitigation interventions. After entering the public health blue alert level, a business continuity plan was distributed. After entering the orange level, the Ministry of Employment and Labor developed workplace guidelines for COVID-19 consisting of social distancing, flexible working schedules, early identification of workers with suspected infections, and disinfection of workplaces. Owing to the intensive workplace social distancing policy, workplaces remained safe with only small sporadic group infections.

Conclusion

The workplace social distancing policy with timely implementation of specific guidelines was a key to preventing a large outbreak of COVID-19 in Korean workplaces. However, sporadic incidents of COVID-19 are still ongoing, and risk assessment in vulnerable workplaces should be continued.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health, Public health surveillance, Social distance, Workplace

1. Introduction

After the World Health Organization declared Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) a global pandemic on March 11, 2020, the confirmed cases exceeded 430,000 patients with what approached 300,000 deaths in more than 200 countries by May 15, 2020 [1]. Owing to the lack of a vaccine or treatment, the most plausible strategies against COVID-19 might be extensive early detection testing and increased physical distancing between susceptible people [2,3], also known as social distancing along with appropriate hygiene (washing hands, proper coughing etiquette). Although social distancing policies raise important ethical issues and questions, they are regarded as one of the principal successful measures against COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea (Korea).

The COVID-19 pandemic has been the biggest public health challenge since the Middle East respiratory disease (MERS) outbreak in 2015, and it poses a challenge to workplace safety and health in Korea. By May 15, 2020, 11,018 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 260 deaths were detected [4]. Rapid spread among a religious group was the first and toughest challenge faced until alert level changed to “red” on February 23, after which various group infections were diagnosed in workplaces such as health-care facilities, sports clubs, call centers, and coin karaoke and nightlife locations [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. Taking rapid, intrusive measures against COVID-19, Korea has slowed the spread of the virus and flattened the curve of new infections [13] with quick and numerous tests for early detection.

Most workplace group infections in Korea developed in dense, narrow-spaced environments which can aggravate aerosol transmission. Social distancing is one of the most important national prevention measures in Korea, with personal sanitation, cough etiquette, and sick leave information in public spaces and workplaces providing updates and guidelines to minimize contact in daily life.

It is not surprising that workplaces pose a high risk of infection in a pandemic situation. In China, seafood and wet animal wholesale markets in Wuhan might have started the outbreak, which then spread to health-care workers exposed to patients with COVID-19. Along with the movement of patients with COVID-19, various workers such as tour guides, jewelry store workers, company staff, taxi drivers, security officers, casino workers, and construction site workers were infected at their workplaces in Singapore [14]. Because a considerable number of group infections occur in workplaces, the guidelines against infection prevention need to include protocols for workplace sanitation and social distancing.

When MERS occurred in Korea at 2015, it was the second largest outbreak after Saudi Arabia. All 186 cases were linked to health-care settings [15], and health-care workers were the most affected (21% of confirmed cases), of whom 39 lost their lives [16]. The MERS outbreak sent a wake-up call to the unprepared quarantine system in large hospitals and the public health system in Korea. Through social and political discussions, the Korean government endeavored to reform the infection prevention system, and the Korean Center for Disease Control (KCDC) developed stronger system controls for future epidemics of infectious disease [17].

Since January 20, 2020, when the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 were diagnosed, the Korean government made a timely systemic response in public spaces and workplaces emphasizing a social distancing policy. Because most of the prepared workplace guidelines against infectious disease were focused on the health-care workers, when the group infection in workplaces expanded to various industries and occupations, Korean society was apprehensive for a while. Based on the framework made after the MERS outbreak, essential policies and detailed distancing measures were provided and distributed through daily broadcasts by the KCDC.

Despite the importance, the experience of workplace policy response to COVID-19 has not been reported before. In Korea, workplace policies have been developed and revised which reflected the actual reality of COVID-19 in workplace. Summarizing these efforts would be critical for other societies where the similar situation might be happening. This study describes the social and workplace distancing policies in response to COVID-19 with an overview of workplace outbreaks in Korea. We summarize the guidelines for social life and workplaces by the alert level to show how the Korean system operated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Material and method

Daily briefings from the KCDC, Central Disaster Management Headquarters (CDMH), and local governments [4] were collected from January 20, 2020 to May 15, 2020. Local governments from which we obtained the briefing data were Seoul city, 6 metropolitan cities (Incheon, Busan, Daejeon, Daegu, Ulsan, and Guangju), and 9 provinces (Kyongki-do, Kangwon-do, Chungcheong buk-do, Chungcheong nam-do, Jeollabuk-do, Jeollanam-do, Kyongsangnam-do, Kyongsangbuk-do, and Jeju-do). The briefings reported all the newly found COVID-19 cases on a daily basis, including the patients' moving path, if any, industry, and job. We counted all the cases reported from workplaces.

A total of 726,747 real-time reverse transcription (polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) assays were tested up until May 15, 2020. Upper respiratory tract specimens are required. Lower respiratory tract specimens are also collected if the patient has sputum [4,18]. The criteria for PCR testing were suspected case and patient under investigation. Definition of a suspected case is a person exhibiting fever (37.5 degree or above) or respiratory symptoms (cough, shortness of breath) or in contact within 14 days with patients with confirmed COVID-19 during the confirmed patients' symptom-exhibiting period. Definition of a patient under investigation is (1) a person suspected of COVID-19 according to a physician's opinion, (2) a person exhibiting fever (37.5 degrees or above) or respiratory symptoms (coughs, shortness of breath, and so on) within 14 days of entering Korea after visiting another country, and (3) a person exhibiting fever (37.5 degrees or above) or respiratory symptoms (coughs, shortness of breath, and so on) with an epidemiological link to a domestic COVID-19 cluster. Sometimes, the KCDC applied exceptions for certain high-risk groups [18].

The four colors of alert system for COVID-19 followed the Infectious Disease Crisis Management Standard Manual (ICM): Blue - case(s) abroad with no immediate threat of importation to Korea, Yellow - domestic importation of case(s) from abroad, Orange - confined spread of case(s) within the country, Red - spread of case(s) in communities across the country [19].

We analyzed group infection in workplaces to illustrate the overall trend of workplace infections. The confirmed cases were classified by the place where individuals supposedly contacted the virus. Workplace cases consisted of workers, customers, patients, and students. Important responses by the CDMH and Ministry of Employment and Labor (MOEL) were evaluated and compared.

3. Results

3.1. COVID-19 prevalence in workplaces

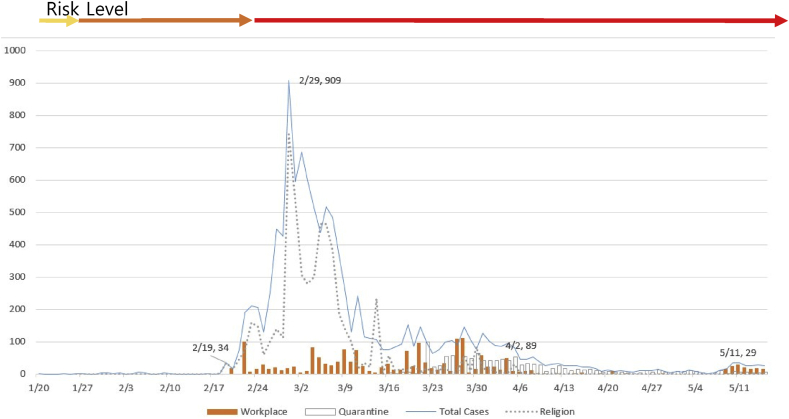

In total, 11,018 COVID-19 cases and 244 deaths were diagnosed from 726,747 tests, representing a 2.2% case fatality rate [4]. Since the first COVID-19 case was confirmed on January 20, 2020, the incidence of COVID-19 was relatively contained with quarantine until a super spreader case from a religious group was identified; and the daily confirmed COVID-19 cases rapidly increased, surging on February 29. With comprehensive, nationwide PCR testing, the number of new cases dropped to under 100 cases in 5 weeks and flattened the curve of incidence (Fig. 1) [20,21]. Despite an additional small surge on May 10, the incidence curve was sustained without a serious 2nd wave increase to date.

Fig. 1.

Daily confirmed cases of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19).

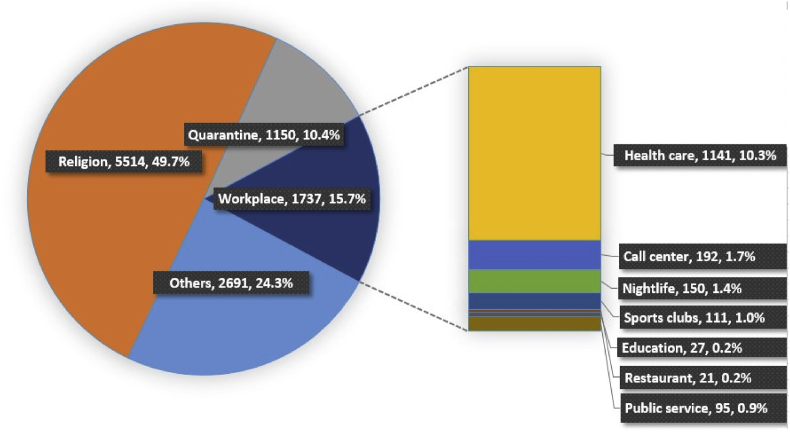

Major group infections reported by central and local authorities belonged to religious groups (49.7%) and workplaces (15.7%). Health-care facilities showed the highest number (10.3%) of COVID-19 cases, followed by call centers (1.7%), nightlife locations, sport clubs, public services, education facilities, and restaurants (Fig. 2). All cases from call centers and public services were employees. However, cases from health-care facilities, nightlife locations, sport clubs, education facilities, and restaurants consisted of workers, customers, patients, and students.

Fig. 2.

Incidence of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) in service industries except call centers and health-care.

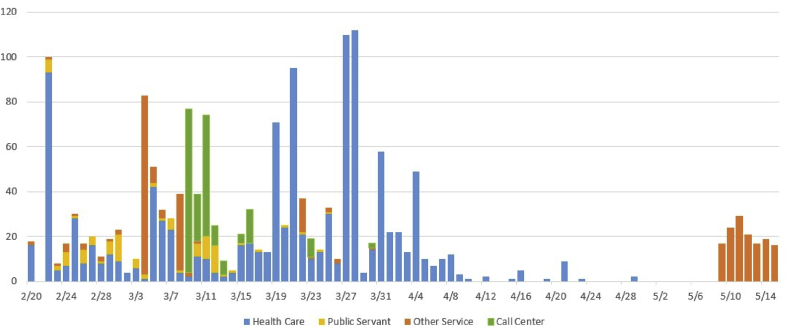

The proportion of the COVID-19 cases in hospitals/clinics and nursing facilities was similar (48.5% and 50.9%), and workers comprised 22% (Table 1). The specific jobs affected and infection course of COVID-19 cases in health-care institutions have not yet been reported. As of April 5, 2020, the KCDC reported that 2.4% (241) among a total of 10,062 confirmed COVID-19 cases were health-care workers, and 1.0% were infected in a work-related environment [9]. The health-care facility incidence started on February 20 was sustained until April 4 and decreased afterward with a small spike again on April 4 (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) cases in health-care facilities (February 20, 2020 ~ May 15, 2020)

| Facilities | Patients/residents | Workers | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital and clinics | 431 | 122 | 5531 | |

| Nursing facilities | Nursing home | 123 | 53 | 176 |

| Nursing hospitals | 323 | 46 | 369 | |

| Daycare center | 15 | 7 | 22 | |

| Visiting care | 1 | 8 | 9 | |

| Disabled facilities | 0 | 5 | 5 | |

| Nursing sum | 462 | 119 | 581 | |

| Others | 0 | 7 | 7 | |

| Total | 893 | 248 | 1,141 | |

Fig. 3.

Workplace incidence of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19).

The prevalence among call center workers was the second largest group of workplace infection (Fig. 2). Because all the call center cases affected only employees, it was the largest group of employee infection. Group infection at a call center was found on March 9 and decreased toward the end of the month (Fig. 3). Call center workers were situated in a highly dense work environment.

Participants in a leadership seminar held in a local sports club during the 6th week of the pandemic spread infection in several other local sports centers, resulting in 111 cases (Fig. 2). A physical activity and a close kinship during the seminar rendered them highly contagious. Most of the group infection cases were customers infected by their sports instructors [7].

The work burden of public service officers increased considerably during the emergency response period, resulting in exhaustion. This group included 95 workers in health departments, prisons, and fire and police stations (Fig. 2). Although the route of infection among them is not yet clear, the importance of public service officers during an emergency response needs to be emphasized.

No group infections were reported from manufacturing industries, possibly due to the presence of younger, asymptomatic cases.

3.2. Response system and relevant actions

The authorities in charge of infection control in Korea consisted of the Ministry of Health and Welfare of the central government and the health departments of local governments. Policies on worker's health fall under the MOEL. Infection spread via workplaces caused several issues related to customers, environments, and the education system. Therefore, COVID-19 prevention in workplaces needed the close interdepartmental collaboration.

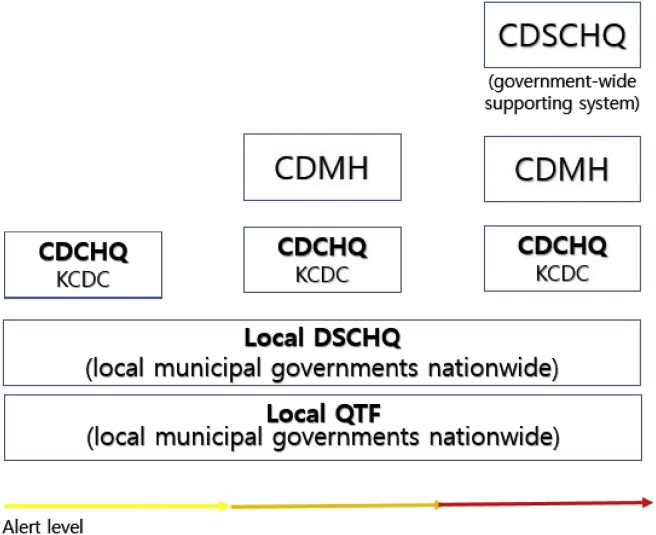

The basic acts formulated for emergency response in Korea were as follows [1]: the Framework Act on the Management of Disasters [22] and [2] the Infectious Disease Control and Prevention Act (IDPA) [23]. According to the IDPA, the basic plan for the prevention and management of infectious diseases (basic plan) should be reestablished every 5 years since 2013 [24]. Based on the Framework Act on the Management of Disasters, the KCDC developed the Information and Communications Technology (ICT). Based on the ICM, an alert system with four levels was developed: blue, yellow, orange, and red. Relevant authorities such as the Central Disease Control Headquarters, the CDMH, the Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters (CDSCHQ), the Local Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters, and the local quarantine task force were established (Fig. 4) [19].

Fig. 4.

Response system to Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) by alert level. CDCHQ, Central Disease Control Headquarters; KCDC, Korean Centers for Disease Control; DSCHQ, Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters; DMH, Disaster Management Headquarters, QTF, quarantine task force.

To solve the problems revealed by loopholes during the MERS epidemic in 2015, the second basic plan (2018-2022) included guidelines and directions for future threatened infectious diseases, plus the establishment of a rapid and accurate monitoring system, and a next-generation infectious disease information system. In addition, the Korean government strengthened the competency of infectious disease crisis communication, developed a reasonable control tower system (emergency situation room), and also revised the basic plan [25].

3.3. Emergency responses and guidelines for the COVID-19 epidemic

At every alert level, authorities made prompt responses and provided relevant guidelines immediately (Table 2). On January 3, 2020, the KCDC raised the alert level for infectious diseases to blue in consideration of the pneumonia cases in China. At the same time, the KCDC began to monitor the risk signs, improve response capacity against COVID-19, and provide real-time immigration information to medical institutes to protect the health-care system from COVID-19 infection. The Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Energy recommended formulating a business continuity plan (BCP). After MERS in 2015, several large companies have been preparing their own BCP [26].

Table 2.

Emergency response and guidelines for Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19)

| Aler level | Public/workplace | Response | Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alert level blue Jan 3 |

National | Response team for infectious disease of KCDC operation | |

| Monitoring the crisis sign Improvement of response capacity Strengthening the quarantine stage |

|||

| Providing immigration information from the infected area in real time through the DUR system to medical institutes | |||

| Workplace | Guideline on developing BCP | ||

| Alert level yellow Jan 20 |

National | CDCHQ, local government task force team operation | |

| Expanding the case definition, strengthening the screening test | COVID-19 prevention code | ||

| Major large hospitals took measures to manage infections quickly, such as limiting inpatient visits and installing thermal sensors. | Detailed procedures of gate quarantine and confirmed case transfer | ||

| Military doctors and nursing officers were sent to quarantine stations in airports and ports across the country | |||

| Workplace | Guideline on developing BCP | ||

| Alert level orange Jan 27 |

National | CDMH operation | |

| Urgent talks for public–private partnerships: Development of diagnostic testing kit for COVID-19 | Guidelines for operation of screening clinics Drive-through screening test guidelines Interim standards for laboratory biosafety for new coronavirus |

||

| Operating intelligent transport system on patients' foreign travel information | Guidelines for Chinese visitors to multiuse facilities Guideline for responding in daycare centers |

||

| Conducting PCR tests in private medical institutions | Notice regarding the prohibition of selling for health masks and hand sanitizers | ||

| Appointing infectious disease hospitals | Guidelines for holding events, festivals, and qualification tests | ||

| Fire officials' mobilization order no. 1 | |||

| Workplace | Expansion of available items to occupational safety and health management expenses: personal masks, thermal imaging cameras, and hand sanitizers. | Preparation for operation of BCP Application of GWR to COVID-19: Social distancing in workplaces, deferment of the workers medical screening program |

|

| Supporting 720,000 masks at construction, manufacturing, and service sites which may be vulnerable to infectious diseases due to frequent employment of foreigners | Notice regarding support for paid vacation and living support due to the infectious disease | ||

| Alert level red Feb 23 |

National | CDSCHQ operation with government-wide support network. | |

| Ban on multiuse facilities (kindergartens, gyms), deferment of school opening | Revision of guidelines for events, multiuse facilities, disinfection | ||

| Relieving the burden of four social insurance payments and electricity | Guidelines for supporting and operating medical personnel dispatched for treatment of COVID-19 | ||

| Appointment of national safe hospitals | Standard operation guidelines for mobile screening clinic | ||

| Fire officials' mobilization order no. 2 | Guidelines for the implementation of flexible work for civil servants | ||

| Opening of residential treatment centers | Common response guidelines for maintaining social welfare services against COVID-19 | ||

| Recommendation to close religious facilities, gyms, clubs, and bars | Strategic supply and demand management plan of medical quarantine goods | ||

| COVID-19 management of medical institutions with confirmed cases | |||

| COVID-19 medical personnel prevention measures | |||

| COVID-19 self-quarantine prevention guidelines | |||

| Strengtheningadministrative orders for schools | |||

| COVID-19 reporting rules (Korea Journalist Association) | |||

| Workplace | Deferment of safety and health education | COVID-19 prevention code in workplace | |

| Financially supporting personal mask manufacturers | Upgrading of the GWR to COVID-19 in several foreign languages, operation of BCP | ||

| Deferment of the occupational accident insurance payment | Workplace distancing guidelines | ||

| Extension of foreign workers' working period | Guidelines for infection prevention at call centers | ||

| Online safety and health inspection | |||

DUR, drug utilization review; CDCHQ, Central Disease Control Headquarters; COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease-19; KCDC, Korean Centers for Disease Control; DSCHQ, Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters; CDMH, Central Disaster Management Headquarters; GWR, Guideline for Workplace Response; BCP, business continuity plan; CDSCHQ, Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters.

The occurrence of the first COVID-19 case in the Republic of Korea (January 20) raised the alert level to yellow and initiated operations in the Central Disease Control Headquarters, Local Disaster and Safety Countermeasure Headquarters, and local quarantine task force. The KCDC expanded the case definition to strengthen the screening testing for COVID-19. All patients or suspected cases were traced. Major health-care facilities quickly enforced infection control procedures according to the ICM. The COVID-19 prevention code and detailed quarantine steps were announced.

After raising the alert level to orange (Jan 27, 2020), the CDMH started to operate with a government-wide support system. The CDMH prepared a fast-track approval system to develop COVID-19 diagnostic testing kits by holding urgent private–public partnership talks. Medical practitioners were provided the travel information of patients through the intelligent transport system, and the number of screening stations and hospitals specialized to infectious diseases was expanded. At that moment, many guidelines covered for the screening test, health clinic, biosafety laboratory, daycare center, and incomer from abroad. Most of the guidelines included social distancing, isolation, and disinfection principles. Considering the limited supply, notice regarding the prohibition of accumulating and hoarding of face masks and hand sanitizers was announced. Postponement of social events such as festivals or qualification tests was recommended.

Workplace policies were determined by the CDMH and MOEL. The major policy for workplaces was notified on Feb 29, 2020, in the “Guidelines for the Workplace Response (GWR) to COVID-19 infection.” The important contents of the GWR included the following (1): Strengthening employee hygiene management and maintaining clean and disinfected workplaces (2), Social distancing and isolation (3), Establishment of a protocol to detect suspected or confirmed patients in the workplace (4), Establishment of a dedicated system and preparation of a response plan for large-scale absenteeism (5), Sick leave management for confirmed patients and contacts (6), and Postponement of special and preplacement health examinations that may increase respiratory droplets during examination, such as pulmonary function examination (pulmonary vitality test, maximum expiratory flow measurement during work, nonspecific hypersensitivity test), plus sputum cell testing among workers who have fever or respiratory abnormalities on the examination day.

In addition to the GWR, an important notice regarding support for paid vacation and living support due to the occurrence of new infectious disease was announced. Because sickness benefits from the national health insurance were not provided to most of the working population in Korea [27], this notice aimed to prevent the presenteeism of symptomatic workers.

The MOEL revised the rule regarding safety and health management expenses to be able to purchase items relating to infection control in workplaces (face masks, cameras, sanitizers). The Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency provided 720,000 masks to the high-risk workplaces.

When the alert level was raised to red, the CDSCHQ and the government-wide network were operationalized. Multiuse facilities, schools, religious facilities, gyms, and bars were recommended to close. Social insurance premium and electrical bill payments were postponed or waived. Guidelines applicable to each situation were distributed quickly. The CDSCHQ classified the social activities as business and daily life (moving, eating, studying, shopping, special days, religious life, and leisure) (Table 3) to develop an appropriate distancing guide. Guidelines for protection of medical personnel, health-care facilities, and the supply of medical goods were also announced. Continuation of social welfare service and flexible work plans was another important part of the guidelines. One remarkable guideline was the COVID-19 reporting rules amended by the Korea Journalists Association. It emphasized the safety of the reporters themselves, refraining from discrimination, and avoiding the spread of false information about COVID-19 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Specific activities need to have detailed guidelines

| Category I | Category II | Detailed activity |

|---|---|---|

| Business [4] | Working | Office (workplace), meeting, public complaint counter, post office |

| Daily [10] | Moving | Public transport |

| Eating | Restaurant and cafe (study cafe) | |

| Studying | Libraries, school/reading rooms, and so on | |

| Shopping | Large distribution facilities (department stores, marts, and so on), traditional markets, and small and medium supermarkets | |

| Special day | Family events such as weddings and funerals | |

| Religious life | Religious facilities | |

| Leisure | Outdoor activities, public restrooms, and so on |

Table 4.

Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) report rules by the Korean Journalist Association

| Korean journalist association 「COVID-19 report rules」 (2020.2.21.) |

|---|

|

|

|

Implementation of the GWR in workplaces was intensified to strengthen social distancing measures. Considering the outbreaks in call centers, the MOEL announced guidelines for call center work. Guidelines for call center workers included allowing home working, maintaining a minimum distance between workers, plastic protective shields between workers flexible working schedules, and detailed instructions for maintaining cleanliness in the workplace. In fact, the restricted working space was one of the most important reasons why the infection rate of COVID-19 was so high. Therefore, the guidelines strengthened regulations governing interpersonal space and flexible working schedules to minimize office congestion.

3.4. Workplace distancing guidelines

The workplace distancing policy in Korea was upgraded on February 23 when the alert level went up to red and returned to distancing in daily life on May 6 when the daily confirmed cases seemed to be stable (Table 5). The MOEL continuously revised the workplace distancing policy with reflection from on-site application. There are five components of workplace distancing guidelines: using a flexible working system, minimizing meetings and business trips, case monitoring, space management, and disinfection.

Table 5.

Workplace distancing details

| Social distancing |

Enhanced social distancing |

Distancing in daily life |

|---|---|---|

| 1.29 - 2.22 | 2.23-5.5 | 5.6 ~ |

| Use sick leave and flexible work | ||

| Active use of flexible working system (telework, time off work, and so on) and vacation system (family care leave, annual leave, sick leave, and so on) | ||

| Meeting and business trips | ||

| Deferring or canceling domestic and overseas business trips, workshops, collective training, training, and so on. | Domestic and foreign business trips are carried out to a minimum, and masks are used in public transportation.Workshops, education, training, and so on can be conducted online or through video. If it is difficult to conduct online, it is carried out on a small scale, but checks for fever, requires masks, provides hand sanitizer, and keeps a sufficient distance between participants | |

| Small groups, in-house club activities, hobby gatherings, and drinking parties are prohibited. | Avoid small gatherings, club activities, and dinners, and return home early after work. | |

| Use the simple meeting room outside the office to receive outside visitors | ||

| Suspicious symptoms monitoring and action in case of symptomatic case | ||

| When commuting to work, body temperature is monitored using a noncontact thermometer or thermal imaging camera (more than twice a day). | Daily body temperature checks with a noncontact thermometer or thermal imaging camera | |

| Workers with fever or respiratory symptoms or who traveled abroad within the past 14 days should use telecommuting, sick leave, or annual leave (if necessary, reflected in employment rules.) | ||

| If you get fever or cough during work, inform the employer and wear a mask to leave the office immediately. | ||

| Management of office space, cafeteria, and rest area | ||

| Keep 2 m distance between workers (at least 1 m) by adjusting the position and orientation of the monitor, desk, and workbench. Install transparent bulkheads between the cafeteria seats or make them sit in a row or zigzag | ||

| Do not allow several people in the common room such as indoor lounges or changing rooms at the same time. Wear a mask when using indoor multiuse facilities | ||

| Disinfection, hygiene, and cleanliness | ||

| If natural ventilation is possible, keep the windows open at all times; if not, periodically ventilate at least twice a day considering the office and workplace area and personnel. | ||

| Commonly used objects (such as door handles) and surfaces are frequently disinfected more than once a day; use personal mugs, teaspoons, and other personal items. | ||

| Stop actions that increase respiratory droplets/contact (singing songs, shouting slogans, and so on) or physical contact (handshake, hugging, and so on) | ||

| Workers who respond directly to customers or work in indoor multiuse facilities should be provided with masks and sanitary items in accordance with the situation of the workplace when it is not possible to keep 2-m personal space. | ||

| When commuting by vehicle, passengers should use a mask and follow the coughing etiquette. Sterilize the commuting vehicle every day. | ||

After the red alert level, the CDSCHQ strongly encouraged a flexible work and the use of sick leave. In the majority of Korean private businesses, especially medium to small-sized enterprises, a paid sick leave is usually provided by neither employers nor the social security system. The COVID-19 crisis evoked a nationwide discussion on the situation that workers have to leave temporarily from the work due to sickness and provision of a paid sick leave. Nineteen percent of Korean workers reported presenteeism [7], which could be an important risk factor for a contagious disease. According to the IDPA, the employers should provide the paid sick leave to workers who needed to leave from the workplace for home quarantine or medical care of infectious diseases. Encouraging the sick leave use and flexible work plans has been sustained since the alert level orange was implemented.

Avoiding face-to-face meetings, business trips, and education and training were another critical component of preventing the spread of workplace infection. During the orange alert level, domestic and overseas trips were recommended to be deferred or canceled except unavoidable cases. Owing to an increase in the number of confirmed patients among civil servants, the government implemented a three-shift remote work system starting March 16 as part of the prevention effort. In this remote working environment, which was established based on a range of ICT technologies including Cloud Mobile, government officials have been working just as efficiently as if they were at the office. Moreover, the online educational system can enable students to continue their mandatory education at home [6]. The guideline restricts small group gatherings, club activities, and social dinner at workplaces and encourages a culture of ‘returning home right after work’.

Suspected signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and hygiene procedures were strictly monitored at the gates and front doors of meeting rooms in most public and private workplaces. The body temperature was recommended to check twice a day in the beginning and once a day after starting social distancing in the normal daily life. The recommendations stated that workers with fever or respiratory symptoms or those who traveled abroad within the past 14 days should take the telecommuting work, sick leaves, or annual leaves.

Management of office space, cafeteria, and other rest areas is an important key to preventing the workplace spread of virus. The guideline recommends keeping a 2-m distance between workers in any space. It also strongly recommends air exchange twice a day and disinfection of commonly used objects and surfaces. Workers at multi-use facilities are encouraged to use a face mask, keep a physical distance from others, and use sanitary items during commuting in the public transportation.

4. Discussion

Although there have been ongoing sporadic workplace outbreaks in areas that were unwatched work such as coin karaoke, nightlife destinations, and delivery works, Korea has slowed the spread of COVID-19 without intensive containment and mitigation interventions to date. This is because the infection control of Korea followed the traditional public health measures on infection outbreak, isolation and quarantine, social distancing, and community containment to prevent the person-to-person spread of disease [28]. In addition, it is reported that social distancing with proper hygiene may reduce incidence and severity [29], leading to economic benefits [30].

Except the most vulnerable spaces such as the religious group in which the super-spreader was found or nightlife locations, most work places in Korea allowed opening of offices and providing services to customers as long as they followed the guidelines for social distancing, wearing a face mask, and disinfection. Major workplace group infection such as in health-care facilities, call centers, sport clubs, and nightlife locations occurred because it was difficult to keep physical distancing in the crowded environment where close physical contacts frequently occurred. The call center was the typical example of a dense workplace. A recent report from a call center outbreak in Seoul revealed that 8.5% of the total workers (97 cases of 1,143) of the building were diagnosed with COVID-19, representing an infection rate of 43.5% of the workers on a specific floor in the building (i.e. 94 of 216) who were positive. This showed that crowded office settings such as call centers could be exceptionally contagious sources of further transmission [8].

There was no remarkable group infection in large manufacturing industries, despite the high reproduction number of COVID-19 (more than 1.5) [6]. Because of the possible spread by asymptomatic cases, COVID-19 could increase in large manufacturing industries as well. However, the MERS and SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) experience in 2015 urged large companies to prepare a BCP including an infection control plan. According to a study conducted to corporate health managers in large enterprises (more than 500 workers) which was performed 1.5 years after the MERS outbreak, 80.4% of the companies had an emergency response plan for an infectious disease outbreak [31]. Considering the major component of a workplace emergency response against infection outbreak is distancing and disinfection, conducting a distancing policy from the start of the orange alert level might be crucial for delaying infection transmission in large enterprises.

After the MERS outbreak in 2015, the Korean society came to realize the urgency of reinforcing the national prevention system: a traveler tracking system via ICT, strengthening the health-care delivery system, amending the Infectious Disease Prevention Act, and establishing bioethics guidelines [32]. This preparedness was one area of the confidence for the KCDC and responsible authorities when the time came to prepare an early detection tool kit for a newly found virus and produce several types of guidelines. In contrast to the MERS outbreak, health-care facilities were not the main site of infection for COVID-19. Because most of the prepared workplace guidelines were focused on health-care facilities, workplace guidelines expanded to various industries and occupations. However, the principle of infection control, isolation, early detection, distancing, and disinfection was not much different, and the response of the MOEL to workplaces was not delayed at all.

However, a false information could result in tragic consequences. Methanol poisoning cases caused by misunderstanding of the effect on COVID-19 was reported in Iran [33]. In this regard, the Korean Journalist Association declared the COVID-19 report rules to adhere to humanistic and sound scientific truth, which was valuable during the COVID-19 emergency response (Table 4).

The limitation of this study is that we could not evaluate the long-term consequences of workplace polices including social distancing to date. Although social distancing might result in effective protection in workplaces, there have been arguments from a psychopathological viewpoint, regarding mental health effects of isolated personnel [34], an aspect of which is not analyzed in this study.

To date, meeting workplace challenges due to COVID-19 has not been easy for workers or professionals. There may be more workplaces vulnerable to infection spread because dense, narrow spaces have not yet been recognized; a comprehensive risk evaluation to check the more vulnerable workplaces is needed. The COVID-19 pandemic is ongoing, and nobody can anticipate how the COVID-19 will be ended. In addition, in the future there, could be another infectious epidemic involving another transformed pathogen that is even more contagious. Therefore, risk assessment in terms of workplace infection is necessary in every workplace. Risk assessment items should include a flexible schedule, presenteeism, congestion of the workplace, personnel density, and a disinfection schedule; the same causes of infection that we observed in the COVID-19 workplace outbreaks. In occupational health, occupational infectious diseases should be treated as a more important part because it sometimes requires the national crisis response system.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . 2020. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard.https://covid19.who.int/ [Internet] cited 2020 May 29]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewnard J.A., Lo N.C. Scientific and ethical basis for social-distancing interventions against COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jun doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30190-0. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7118670/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 5];20(6):631–3. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wold Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

- 4.Korea Center for Disease Control Daily briefings from center for disease control head quarters. Daily Briefings. 2020 http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/tcmBoardList.do?brdId=3&brdGubun= [Internet] [cited 2020 May 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korean Society of Infectious Diseases Korean society of pediatric infectious diseases, Korean society of epidemiology, Korean society for antimicrobial therapy, Korean society for healthcare-associated infection control and prevention, Korea centers for disease control and prevention. Report on the epidemiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the Republic of Korea from january 19 to March 2, 2020. J Kor Med Sci. 2020 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e112. https://jkms.org/DOIx.php?id=10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e112 [Internet] [cited 2020 May 26];35(10):e112. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shim E., Tariq A., Choi W., Lee Y., Chowell G. Transmission potential and severity of COVID-19 in South Korea. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Apr 1 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.031. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971220301508 [Internet] [cited 2020 May 27];93:339–44. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jang S., Han S.H., Rhee J.-Y. vol. 26. Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC; August 2020. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/8/20-0633_article (Early release - cluster of coronavirus disease associated with fitness dance classes, South Korea). Number 8—. [cited 2020 May 26]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park S.Y., Kim Y.-M., Yi S., Lee S., Na B.-J., Kim C.B., Kim J.-I., Kim H.S., Kim Y.B., Park Y., Huh I.S., Kim H.K., Yoon H.J., Jang H., Kim K., Chang Y., Kim I., Lee H., Gwack J., Kim S.S., Kim M., Kweon S., Choe Y.J., Park O., Pakr Y.J., Jeong E.K. Early release - coronavirus disease outbreak in call center, South Korea. Emerg Infect Dis - CDC. August 2020;26(8) doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201274. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/8/20-1274_article [cited 2020 May 26]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang S.-K. COVID-19 and Middle East respiratory syndrome infections in health-care workers in Korea. Saf Health Work. 2020 May 7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7204702/ [Internet] [cited 2020 May 26]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang Y-J. Lessons learned from cases of COVID-19 infection in South Korea. Disaster Med Publ Health Preparedness [Internet]. undefined/ed [cited 2020 Jun 6];1–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32378503/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Herald T.K. 2020 May 7. COVID-19 patient went clubbing in Itaewon.http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200507000634 [cited 2020 Jun 22]; Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herald T.K. 2020. Seoul suspends “coin noraebang” to contain virus.http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20200522000675 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Issac A., Stephen S., Jacob J., Vijay V.R., Rakesh V.R., Krishnan N., Dhandapani M. The Pandemic league of COVID-19: South Korea vs United States, the preached lessons for entire world. J Prevent Med Publ Health [Internet] 2020 May 25 doi: 10.3961/jpmph.20.166. https://www.jpmph.org/journal/view.php?number=2089 [cited 2020 Jun 23]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh D. Occupational risks for COVID-19 infection. Occup Med. 2020 Mar doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqaa036. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7107962/ (Lond) [Internet] cited 2020 May 26];70(1):3–5. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon M.H., Kim T.H. Institutional preparedness to prevent future Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus-like outbreaks in Republic of Korea. Infect Chemother. 2016 Jun 1 doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.75. [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 5];48(2):75–80. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang C.H., Jung H. Topological dynamics of the 2015 South Korea MERS-CoV spread-on-contact networks. Sci Rep. 2020 Mar 9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61133-9. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-61133-9 [Internet] [cited 2020 May 29];10(1):4327. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y. Healthcare reform after MERS outbreak: progress to date and next steps. J Kor Med Assoc. 2016 https://synapse.koreamed.org/DOIx.php?id=10.5124/jkma.2016.59.9.668 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 5];59(9):668. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.KCDC. Frequently asked questions for KCDC on COVID-19 [Internet]. KCDC. [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: http://www.cdc.go.kr.

- 19.Ministry of Health and Welfare . MOHW; 2016. Standard manual for infection disease risk management. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Government of Republic of Korea . 2020. Tackling COVID-19 health, quarantine and economic measures.https://ecck.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Tackling-COVID-19-Health-Quarantine-and-Economic-Measures-of-South-Korea.pdf [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Government of Republic of Korea . 2020. How Korea responded to a pandemic using ICT: flattening the curve on COVID-19.https://socialdigital.iadb.org/en/covid-19/technical-resources/4944 [Internet] [cited 2020 May 26]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Public Safety and Security . 2010. Framework act on the management of Disasters and safety.https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=46614&lang=ENG [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ministry of Health and Welfare . 2016. Infectious disease control and prevention act.https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=40184&lang=ENG [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Health and Welfare . 2018. Infectious disease prevention management basic plan. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee J.-S.A. Korea Legislation Research Institutue; Seoul, Korea: 2018. Study on improvement of infectious disease control and prevention act and system.http://www.klri.re.kr/kor/publication/1841/view.do [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 1]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D.J., Yang S.W., Choi D.J., Kim G.W., Jang H.M., Kim D.H., Eun M.G. A study on the establishment of business continuity management systems of the organization during a pandemic outbreak (focusing on the finance correspond case) J Kor Soc Disaster Security [Internet] 2016 http://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201608965832193.page [cited 2020 Jun 5];9(2):93–101. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jung H.W., Sohn M., Chung H. Designing the sickness benefit scheme in South Korea: using the implication from schemes of advanced nations. Health Pol Manage. 2019 https://www.koreascience.or.kr/article/JAKO201919867049154.j [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 6];29(2):112–29. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilder-Smith A., Freedman D.O. Isolation, quarantine, social distancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020 Mar 13 doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa020. https://academic.oup.com/jtm/article/27/2/taaa020/5735321 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 5];27(2). Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalton C., Corbett S., Katelaris A. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2020 Mar. Pre-emptive low cost social distancing and enhanced hygiene implemented before local COVID-19 transmission could decrease the number and severity of cases.https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3549276 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 6]. Report No.: ID 3549276. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenstone M., Nigam V. Social Science Research Network; Rochester, NY: 2020 Mar. Does social distancing matter?https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3561244 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 6]. Report No.: ID 3561244. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sook J.I., Jungok Y., Jeong and H.M. Workplace response system Against infectious Disasters based on the MERS outbreak in Korea. Kor J Occup Health Nurs. 2017 Nov 30 http://www.kjohn.or.kr/journal/view.html?doi=10.5807/kjohn.2017.26.4.207 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 6];26(4):207–17. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park C. MERS-CoV infection in South Korea and strategies for possible future outbreak: narrative review. J Glob Health Rep. 2019 Dec 30 https://www.joghr.org/article/12122-mers-cov-infection-in-south-korea-and-strategies-for-possible-future-outbreak-narrative-review [Internet] [cited 2020 May 29];3:e2019088. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delirrad M., Mohammadi A.B. New methanol poisoning outbreaks in Iran following COVID-19 pandemic. Alcohol Alcohol. 2020 May 13 doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agaa036. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7239215/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 6]; Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiorillo A., Gorwood P. European Psychiatry; 2020. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice.https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-psychiatry/article/consequences-of-the-covid19-pandemic-on-mental-health-and-implications-for-clinical-practice/E2826D643255F9D51896673F205ABF28 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 24];63(1). Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]