Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic value of combining the quantitative parameters of shear wave elastography (SWE) and superb microvascular imaging (SMI) to breast ultrasound (US) to differentiate between benign and malignant breast masses.

Materials and Methods

A total of 200 pathologically confirmed breast lesions in 192 patients were retrospectively reviewed using breast US with B-mode imaging, SWE, and SMI. Breast masses were assessed based on the breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) and quantitative parameters using the maximum elasticity (Emax) and ratio (Eratio) in SWE and the vascular index in SMI (SMIVI). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) value, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, negative predictive value, and positive predictive value of B-mode alone versus the combination of B-mode US with SWE or SMI of both parameters in differentiating between benign and malignant breast masses was compared, respectively. Hypothetical performances of selective downgrading of BI-RADS category 4a (set 1) and both upgrading of category 3 and downgrading of category 4a (set 2) were calculated.

Results

Emax with a cutoff value of 86.45 kPa had the highest AUC value compared to Eratio of 3.57 or SMIVI of 3.35%. In set 1, the combination of B-mode with Emax or SMIVI had a significantly higher AUC value (0.829 and 0.778, respectively) than B-mode alone (0.719) (p < 0.001 and p = 0.047, respectively). B-mode US with the addition of Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI had the best diagnostic performance of AUC value (0.849). The accuracy and specificity increased significantly from 68.0% to 84.0% (p < 0.001) and from 46.1% to 79.1% (p < 0.001), respectively, and the sensitivity decreased from 97.6% to 90.6% without statistical loss (p = 0.199).

Conclusion

Combining all quantitative values of SWE and SMI with B-mode US improved the diagnostic performance in differentiating between benign and malignant breast lesions.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Shear wave elastography, Superb microvascular imaging, Breast, Neoplasm

INTRODUCTION

Breast ultrasound (US) elastography is an imaging technique for tissue characterization that aims to determine the stiffness of a target lesion. A close association between cancer and the extracellular matrix has been described, and increased stiffness in the extracellular cancer matrix was observed in breast cancer (1). Shear wave elastography (SWE) uses acoustic radiation via a focused US beam to induce mechanical vibrations and quantifies the stiffness of the tissue by capturing propagating shear waves (2). Tissue elasticity is quantitated in kilopascals (kPa) or meters per second (m/s) (2,3,4). By setting the focal areas in the region of interest (ROI), a variety of quantitative elasticity values can be obtained by SWE. Mean stiffness (Emean) and maximum elasticity (Emax) represent the general stiffness of the mass, and the elasticity ratio (Eratio) shows the relative stiffness of the mass to the fat tissue, which has a coherent elasticity value. The standard deviation represents the internal heterogeneity of the mass (5,6). Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy and diagnostic accuracy of SWE in the diagnosis of solid breast masses, and the combination of B-mode US with SWE was considered beneficial in the assessment of breast lesions using different quantitative parameters and cutoff values of SWE (2,3,4,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22).

An emerging technique of Doppler ultrasonography called superb microvascular imaging (SMI) has been applied to determine microvascular blood flow due to the close association between microvascularity and malignancy. Conventional color Doppler technique uses a single-dimensional wall filter to remove signals from tissue motion (clutter), and it cannot visualize significantly low-velocity blood flows. However, SMI technology can detect both low-velocity and high-velocity blood flows using a multidimensional filter, which preserves slow flow signals separating from the clutter (23). Recently, SMI evaluation using quantitative measurements of Doppler signals, called the vascular index in SMI (SMIVI), has been introduced. SMIVI is the percentage ratio between the pixels for the Doppler signal and those for the total lesion (23,24). Studies investigating the diagnostic value of SMIVI in differentiating benign and malignant breast masses are relatively few (25,26). However, studies assessing the cutoff values of the quantitative parameters derived from both SWE and SMI and the diagnostic performance of combining these quantitative parameters and B-mode US-based breast imaging reporting and data system (BI-RADS) have not been conducted yet. Our study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic value of combining the quantitative parameters of SWE and SMI to breast US to differentiate benign and malignant breast masses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Ethical Issues in Clinical Research. From November 2018 to May 2019, B-mode US, SWE, and SMI were performed on 217 consecutive women aged 19 years or older who planned a US-guided core needle biopsy or vacuum-assisted excision. Twenty-five patients were excluded from the study. Four patients with mammoplasty implants, complex masses, or calcified masses and eight patients with non-mass lesions were excluded because they had factors affecting the accurate measurement of SWE and SMI (vascular index) of solid components. Thirteen patients for whom all three quantitative parameters were not available were excluded. Eight patients who underwent biopsies of two masses were included. Finally, 200 solid breast masses in 192 consecutive women (mean age, 49.0 ± 13.5 years [range, 19–82 years]) were included in this study. Breast US examinations were performed, including B-mode imaging, SWE measurement, and SMI measurement, within 1 month of the patient's biopsy.

Ultrasound Examinations

US examination was obtained using a Aplio i800 (Canon Medical Systems Corporation), equipped with an 18- to 7-MHz linear array transducer. The examinations were performed by one of the two board-certified radiologists (with 17 and 2 years' experience in breast imaging, respectively). The radiologists were well informed of the clinical information or mammographic findings of the patient before the US examinations. After the conventional B-mode US, SWE, and SMI were performed by the radiologist who performed the B-mode US, SWE images were obtained by applying the linear transducer significantly lightly to the skin above the targeted lesion with a generous amount of transducer gel. The probe was held still for a few seconds to allow the SWE image to stabilize, and adequate quality SWE images were saved. Images of the B-mode US, color map, variance map, and propagation map of SWE were simultaneously displayed by a splitscreen mode of a single screen. The quality of shear wave propagation is displayed by variance and propagation map that visualize shear wave arrival time. The operator repeatedly obtained SWE images per lesion, and the image with best quality of shear wave propagation showing homogeneous variance map was selected for the analysis. The maximum elasticity was set to display up to 180 kPa. The quantitative elasticity values were measured using 2-mm round ROIs, one at the stiffest area of the mass, including immediately adjacent stiff tissue, and the other at the normal subcutaneous fat tissue within the ROI box. The system automatically calculated and visualized the Emax. The Eratio, which is the ratio of the normal subcutaneous fat tissue, was also obtained and recorded for analysis. Vascularity in the breast mass was quantitatively assessed using SMI. In each lesion, the ROI was manually drawn along the margin of the mass at the plane with richest Doppler signal within the mass among the two to three times of repeated measurements. The quantitative SMIVI was automatically calculated using dedicated Canon system software. The image parameters for SMI were as follows: velocity scale, 2.5 cm/sec; dynamic range, 21 dB; and frame rate, 13 frames/sec. All quantitative parameters were measured at least two or more times for each breast lesion. The data acquisition procedure for SWE and SMI was approximately performed 3–5 minutes per case.

Image Analysis

The conventional B-mode US findings were categorized using the American College of Radiology BI-RADS lexicon, 5th edition (27). The final assessments of the 200 breast masses were categorized as follows: category 3 (probably benign), category 4a (low suspicion for malignancy), category 4b (moderate suspicion for malignancy), category 4c (high suspicion for malignancy), and category 5 (highly suggestive of malignancy). Regarding statistical analysis, BI-RADS category 3 on conventional B-mode US masses was considered benign, and BI-RADS category 4a and higher masses were considered malignant. The US images including B-mode, SWE, and SMI were analyzed, in consensus, by two board-certified radiologists, with 17 and 2 years' experience in breast imaging, respectively. The readers were blinded to the histopathological results. For each lesion, BI-RADS category assessment based on B-mode US was performed without knowledge of the SWE and SMI. For SWE and SMI images, the representative images to be used for analysis were selected by a consensus of two readers among the repeated measurement images.

Statistical Analyses

For the comparison of size, Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI between the benign and malignant groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used as the continuous variables were not normally distributed. A retrospective review of the quantitative Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI values was performed, and the cutoff values were determined by comparison to the pathological results. Pathological results from US-guided core needle biopsies or surgery were used as the reference standards. To evaluate the diagnostic performance of each quantitative parameter, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were analyzed. The optimal cutoff values for differentiation of benign and malignant masses were calculated as the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity using Youden's index. To summarize each method's overall performance, areas under the ROC curves (AUCs) were calculated and compared. Statistically significant differences in the AUC values were reported as 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy of the quantitative parameters were obtained using the calculated cutoff values.

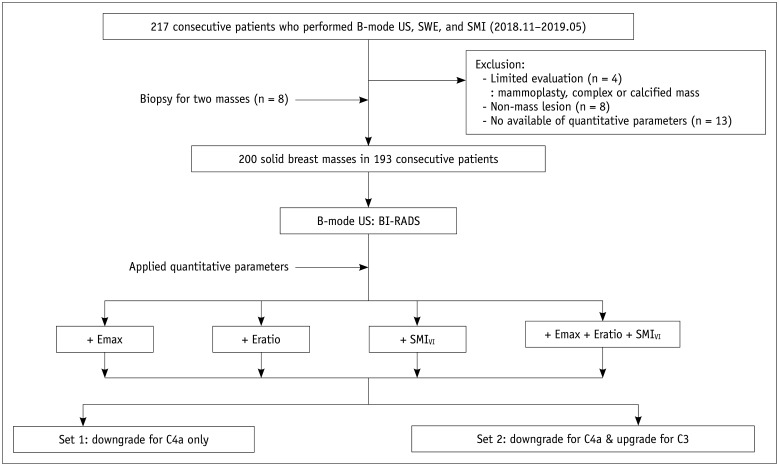

Hypothetical performance of downgrading or upgrading of B-mode US classification based on SWE and SMI was evaluated. Two sets groups for BI-RADS category 3 and 4a lesions were compared by applying the cutoff values for Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI. For set 1, selective downgrades were performed for only BI-RADS category 4a lesions when each value was lower than the respective cutoff value. For set 2, reassessment of the BI-RADS category was performed for both category 3 and 4a lesions. Selective downgrade for category 4a was performed when each value was lower than the respective cutoff value, and selective upgrades for category 3 lesions were performed when the quantitative values were higher than the respective cutoff values. In applying all combinations of quantitative values for Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI to assess category 3 and 4a lesions, the mass was selectively downgraded to benign if one or none of the parameters exceeded the cutoff values. The mass was considered to be malignant or selectively upgraded if all three parameters exceeded the cutoff values (Fig. 1). When B-mode US and each quantitative parameter were combined, the AUC values were used to evaluate the hypothetical effects of set 1 and set 2 compared to the AUC values of B-mode US alone. Additionally, sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, PPV, and NPV were compared between B-mode US alone versus the combination of quantitative parameters showing significant differences in the ROC. Statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0 (IBM Corp.) and Rex 3.1.2 version (rexsoft.org). P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Fig. 1. Study flow diagram.

BI-RADS = breast imaging reporting and data system, Emax = maximum elasticity, Eratio = elasticity ratio, SMI = superb microvascular imaging, SMIVI = vascular index in SMI, SWE = shear wave elastography, US = ultrasound

RESULTS

Lesion Characteristics

Of the 200 breast lesions, 115 (57.5%) were benign and 85 (42.5%) were malignant. All lesions were pathologically confirmed with core needle biopsy, and some patients underwent additional vacuum-assisted biopsy or surgical excision. Detailed histological results of the lesions are shown in Table 1. The median size of malignant breast masses was significantly larger than that of the benign masses (p < 0.001). All median values of quantitative parameters were significantly higher in the malignant lesions than those of the benign lesions: Emax, 113.70 kPa (interquartile range [IQR], 47.25–138.70) and 21.30 kPa (IQR, 10.60–45.70); Eratio, 9.71 (IQR, 4.30–20.78) and 2.50 (IQR, 1.45–4.72); and SMIVI, 7.60% (IQR, 4.15–12.30) and 2.1% (IQR, 0.00–5.60) for malignant versus benign lesions, respectively (all p < 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of SWE and SMI Parameters between Benign and Malignant Masses and Histologic Diagnoses according to BI-RADS.

| Parameters | Benign (n = 115) | Malignant (n = 85) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size (mm) | 10.0 (7.0–14.0) | 13.0 (9.5–21.5) | < 0.001 |

| Emax (kPa)* | 21.30 (10.60–45.70) | 113.70 (47.25–138.70) | < 0.001 |

| Eratio* | 2.50 (1.45–4.72) | 9.71 (4.30–20.78) | < 0.001 |

| SMIVI (%)* | 2.10 (0.00–5.60) | 7.60 (4.15–12.30) | < 0.001 |

| BI-RADS† | |||

| Category 3 (55) | Benign breast tissue (24) | IDC (2) | NA |

| Duct ectasia (1) | |||

| Epidermoid cyst (1) | |||

| FA and fibroadenomatous hyperplasia (20) | |||

| Periductal inflammation (1) | |||

| Intraductal papilloma (2) | |||

| LCIS (1) | |||

| Lipoma (1) | |||

| Intramammary lymph node (1) | |||

| Sclerosing adenosis (1) | |||

| Category 4a (67) | FA and fibroadenomatous hyperplasia (25) | IDC (15) | NA |

| Benign breast tissue (13) | DCIS (7) | ||

| Granulomatous mastitis (1) | |||

| Intraductal papilloma (6) | |||

| Category 4b (34) | FA (4) | IDC (17) | NA |

| Benign breast tissue (7) | DCIS (5) | ||

| Apocrine metaplasia (1) | |||

| Category 4c (27) | FA (1) | IDC (18) | NA |

| Benign breast tissue (4) | DCIS (4) | ||

| Category 5 (17) | IDC (16) | NA | |

| DCIS (1) |

*Data are expressed as median (interquartile range), †Data are expressed as numbers. BI-RADS = breast imaging reporting and data system, DCIS = ductal carcinoma in situ, Emax = maximum elasticity, Eratio = elasticity ratio, FA = fibroadenoma, IDC = intraductal carcinoma, LCIS = lobular carcinoma in situ, NA = not applicable, SMI = superb microvascular imaging, SMIVI = vascular index in SMI, SWE = shear wave elastography

Comparison of Diagnostic Performance between Shear Wave Elastography versus Superb Microvascular Imaging

The diagnostic performance of the quantitative SWE and SMI parameters at various cutoff values is summarized in Table 2. The Emax values with the optimal cutoff set at 86.45 kPa had the highest AUC value (0.838 [95% CI, 0.779–0.898]) among the quantitative parameters, with a sensitivity of 71.8%, specificity of 91.3%, PPV of 85.9%, NPV of 81.4%, and accuracy of 83.0%. The optimal cutoff values for the Eratio and SMIVI were 3.57 and 3.35%, respectively.

Table 2. Diagnostic Performance of SWE and SMI in Distinguishing Malignant from Benign Masses.

| Variables | Cutoff Values | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emax (kPa) | 86.45 | 71.8 (61/85) | 91.3 (105/115) | 83.0 (166/200) | 85.9 (61/71) | 81.4 (105/129) | 0.838 (0.779–0.898) |

| Eratio | 3.57 | 82.4 (70/85) | 69.6 (80/115) | 75.0 (150/200) | 66.7 (70/105) | 84.2 (80/95) | 0.813 (0.752–0.873) |

| SMIVI (%) | 3.35 | 84.7 (72/85) | 63.5 (73/115) | 72.5 (145/200) | 63.2 (72/114) | 84.9 (73/86) | 0.766 (0.700–0.833) |

Data are expressed as percentage (numbers). AUC = area under receiver operating characteristic curve, CI = confidence interval, NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value

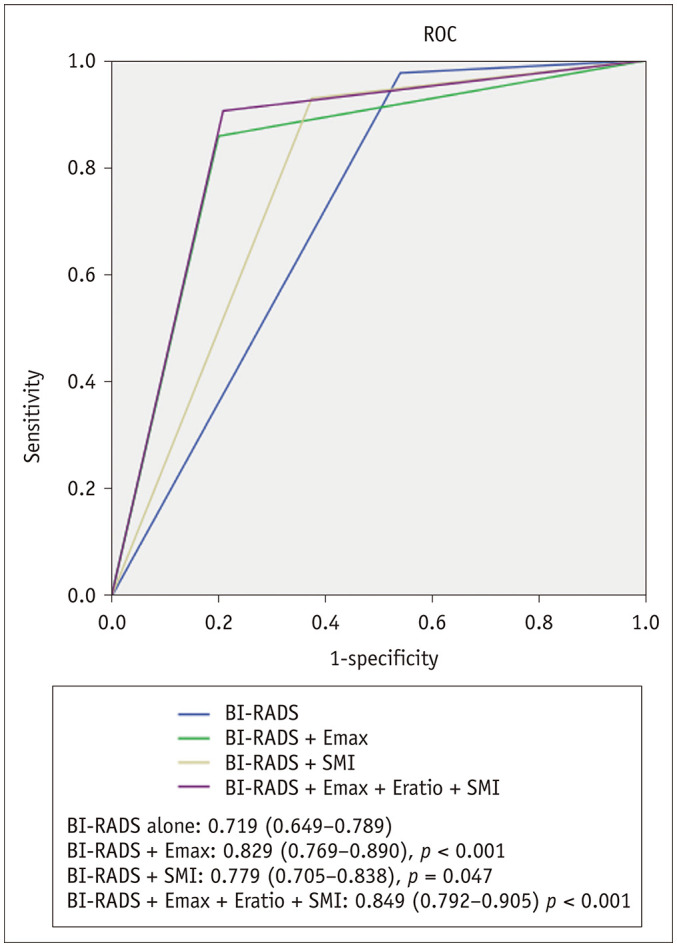

In set 1 (selective downgrading only for category 4a lesions), the combination of B-mode US with Emax or SMIVI resulted in significantly higher AUC values at 0.829 (95% CI, 0.769–0.890; p < 0.001) and 0.778 (95% CI, 0.713–0.843; p = 0.047) than B-mode US alone, with an AUC value of 0.719 (95% CI, 0.649–0.789). In set 2 (selective downgrading for category 4a and selective upgrading for category 3), there was no significant difference between the combination of each quantitative SWE and SMI parameter with B-mode US and B-mode US alone (Table 3). For all combinations of B-mode US and the quantitative values of SWE and SMI, no category 3 lesions were upgraded. Therefore, the results for set 1 and set 2 were the same when all combinations of B-mode US and quantitative parameters of SWE and SMI were analyzed. B-mode US with the addition of all Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI had significantly higher AUC than BI-RADS alone (Fig. 2). The AUC increased from 0.719 (95% CI, 0.649–0.789) to 0.849 (95% CI, 0.792–0.905; p < 0.001). All combinations of B-mode US with Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI showed the best diagnostic performance with 84.0% accuracy (p < 0.001). The specificity significantly increased from 46.1% to 79.1% (p < 0.001). There was a slight loss of sensitivity from 97.6% to 90.6%, but it was not statistically significant (p = 0.199) (Table 4). Figure 3 demonstrates a case of correct downgraded after combining all quantitative parameters, which was pathologically confirmed as fibroadenoma.

Table 3. Diagnostic Performance of Combined Use of Quantitative Parameters of SWE and SMI with B-Mode US in Differentiating Malignant from Benign Masses.

| Variables | AUC | 95% CI | P§ |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-mode US alone | 0.719 | 0.649–0.789 | NA |

| Set 1* (selective downgrade of category 4a) | |||

| B-mode + Emax | 0.829 | 0.769–0.890 | < 0.001 |

| B-mode + Eratio | 0.772 | 0.705–0.838 | 0.092 |

| B-mode + SMIVI | 0.778 | 0.713–0.843 | 0.047 |

| Set 2† (reassessment of both category 3 & 4a) | |||

| B-mode + Emax | 0.742 | 0.671–0.813 | 0.894 |

| B-mode + Eratio | 0.685 | 0.611–0.760 | 0.167 |

| B-mode + SMIVI | 0.687 | 0.613–0.761 | 0.424 |

| Set 1 and Set 2‡ | |||

| B-mode + Emax + Eratio + SMIVI | 0.849 | 0.792–0.905 | < 0.001 |

*Selective downgrade for only BI-RADS category 4a lesion when each value was lower than respective cutoff value, †Reassessment of BI-RADS category for both category 3 and 4a. Selective downgrade for category 4a when each value was lower than respective cutoff values and selective upgrade for category 3 when quantitative values higher than respective values, ‡Selective downgrade if one or no parameter for exceeding cutoff values, selective upgrade if all three parameters for exceeding cutoff values, §p values indicate comparison of diagnostic performance of between BI-RADS alone and addition of quantitative parameters. US = ultrasound

Fig. 2. ROC curve for BI-RADS alone and combined with quantitative parameters for set 1.

AUC were significantly different between BI-RADS alone for all combined quantitative parameters (Emax + Eratio + SMIVI) and Emax (p < 0.001). All combined quantitative parameters with BI-RADS had highest AUC values (0.849), (95% confidence interval, 0.792–0.905). AUC = area under ROC curve, ROC = receiver operating characteristic

Table 4. Effect of Downgrading BI-RADS Category 4a Lesions with Combined Use of Quantitative Parameters of SWE and SMI in Addition to B-Mode US (Set 1).

| Variables | Sensitivity (%) | P† | Specificity (%) | P† | Accuracy (%) | P† | PPV (%) | P† | NPV (%) | P† | AUC | P† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-mode* alone | 97.6 (83/85) | NA | 46.1 (53/115) | NA | 68.0 (136/200) | NA | 57.2 (83/145) | NA | 96.4 (53/55) | NA | 0.719 | NA |

| B-mode + Emax | 85.9 (73/85) | 0.037 | 80.0 (92/115) | < 0.001 | 82.5 (165/200) | 0.001 | 76.0 (73/96) | < 0.001 | 88.5 (92/104) | < 0.001 | 0.829 | < 0.001 |

| B-mode + SMIVI | 92.9 (79/85) | 1.000 | 62.6 (72/115) | 0.069 | 75.5 (151/200) | 0.567 | 64.8 (79/122) | 0.027 | 92.3 (72/78) | 0.497 | 0.778 | 0.047 |

| B-mode + Emax + Eratio + SMIVI | 90.6 (77/85) | 0.199 | 79.1 (91/115) | < 0.001 | 84.0 (168/200) | < 0.001 | 76.2 (77/101) | < 0.001 | 91.9 (91/99) | 0.002 | 0.849 | < 0.001 |

Data are expressed as percentage (numbers). *Assessment category of masses based on B-mode US according to BI-RADS, †Comparison of diagnostic performance of between BI-RADS alone and addition of quantitative parameters.

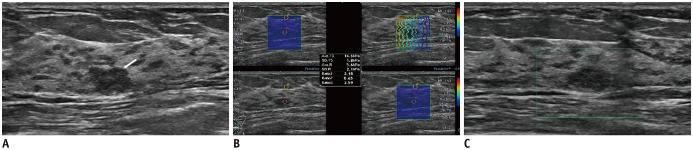

Fig. 3. 45-year-old woman with breast mass.

Conventional B-mode US (A) revealed 10-mm round, hypoechoic mass with microlobulated margin in left breast (arrow). Breast imaging reporting and data assessment of B-mode US categorized it as 4a. SWE parameters were as follows: Emax, 14.5 kPa; Eratio, 2.59 (B); and SMIVI, 0% (C). Considering that all quantitative parameters were less than cutoff values, final category was downgraded to 3. US-guided core needle biopsy revealed this lesion as fibroadenoma.

False-Negative Results in Selective Downgrading Category 4a Lesions

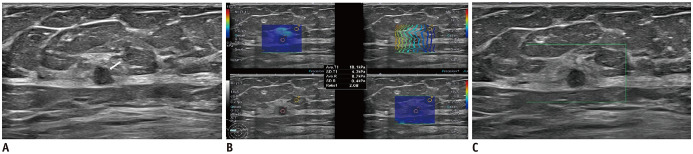

For all combinations of B-mode US and the quantitative parameters, the number of lesions downgraded from category 4a to 3 was 44 out of 67 (65.6%). Six cases of category 4a lesions, with pathological results of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (n = 3) and invasive ductal carcinomas (n = 3), were downgraded incorrectly. Except for one false-negative case with a 12-mm-diameter DCIS, five of the false-negative cases were small, measuring less than 10 mm in diameter, with a mean lesion size of 8 mm (range, 5–12 mm). Figure 4 demonstrates a case of incorrect downgrade after combining all quantitative parameters, which was pathologically confirmed as intraductal carcinoma. Among the 55 lesions assessed as category 3, only two masses with a mean diameter of 5 mm were incorrectly categorized as benign, none of which were upgraded when all of the quantitative parameters were applied. The pathological diagnoses were confirmed as invasive ductal carcinoma.

Fig. 4. 77-year-old woman with breast mass.

Conventional B-mode US (A) revealed 5-mm round, hypoechoic mass with microlobulated margin in right breast (arrow). Breast imaging reporting and data assessment of B-mode US categorized it as 4a. SWE parameters were as follows: Emax, 18.1 kPa; Eratio, 2.08 (B); and SMIVI, 0% (C). US-guided core needle biopsy and subsequent surgical excision confirmed this lesion as invasive ductal carcinoma.

DISCUSSION

Our study investigated the diagnostic performance using the quantitative values of SWE and SMI in addition to B-mode US to differentiate benign from malignant breast masses. The combination of SWE with B-mode US has been reported to increase the diagnostic performance for differentiating breast masses. The quantitative parameters of SWE showing good diagnostic performance were reported to be Emax, Emean, and Eratio in previous studies (2,3,8,9,10,11,15,28,29). Our study showed that Emax showed the best performance, with an AUC of 0.838 (95% CI, 0.777–0.898) when a cutoff value of 86.45 kPa was applied, which was similar to the previously reported cutoff range of Emax (46.7–93.8 kPa) (2,6,12,21,30,31). Several previous studies have reported that the combination of Eratio and B-mode US had the best diagnostic performance among other shear wave parameters in the stratification of category 4 lesions, with a cutoff value of 3.56–5.14 (16,17). However, our study showed no statistically significant increase in the diagnostic performance by combining Eratio to B-mode US with the cutoff value of 3.57. Emax is a value obtained by setting the ROI on the stiffest part of the mass and is independent of the size of the ROI, different from Emean or standard deviation of elasticity values (2,6,12,21,30,31). Additionally, in our study, when the ROI was set at the stiffest part of the lesion with the best shear wave propagation quality by referring to the variance map, Emax values' less influence on precompression may have been obtained. This is possibly the reason why Emax has higher diagnostic performance than Eratio.

Regarding the color Doppler image, there are several studies showing that combined elastography and color Doppler images improves diagnostic performance (28,29,32,33,34). Most of the previous studies investigating SMI used qualitative features or subjective Adler's grading of vascularity (32,35,36,37,38,39). Recently, the quantitative assessment of SMI has become available by calculating the ratio of Doppler signals within the lesion, called the vascular index. A few studies have investigated the diagnostic performance of the quantitative parameters of SMI using the vascular index and have shown good diagnostic performance (25,26). In our study, SMIVI showed significant difference between benign and malignant lesions when a cutoff value was 3.35%. The optimal cutoff values of the SMIVI varied from 4.0% to 8.9% for differentiating benign and malignant breast masses (25,26). In both studies, an SMI image with the most abundant Doppler signal was retrospectively selected among the previously obtained images and drew the ROI for SMIVI using the post-processing software masses (25,26). In our study, each observer selected Doppler images and drew the ROI for the measurement of SMIVI in real time. Benign neoplasms such as fibroadenoma, intraductal papilloma, and adenosis with a rich vascularity and malignancies such as DCIS with little vascularity due to heterogeneous angiogenesis are possible causes of false-positive or false-negative results of SMIVI (25). Zhu et al. (32) reported that the combination of quantitative parameters of SWE and vascularity grading on SMI added to B-mode US presented a better diagnostic performance in differentiating malignant breast tumors. Previous studies used qualitative parameters and combined the use of quantitative and qualitative parameters of elastography and Doppler images. Our study first showed that SMIVI has an added value in distinguishing malignant from benign breast lesions when used alone and when used in combination with quantitative parameters of SWE.

There are a few studies that downgrade BI-RADS category 4a lesions and upgrade category 3 lesions using strain elastography or SWE (21,40). We compared the diagnostic performance of two case sets of BI-RADS category 3 and 4a lesions by combining the quantitative parameters of SWE and SMI. In our study, only the selective downgrade of category 4a lesion (set 1) showed significantly better diagnostic performance than B-mode US alone. There was no statistically significant improvement in diagnostic performance in selectively applying the criteria for category 3 and 4a (set 2). All quantitative parameters for Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI with B-mode US showed a statistically significant improvement in accuracy (84.0%) and specificity (79.1%) and no statistically significant loss of sensitivity (90.6%, p = 0.199) compared to B-mode US alone. The application of all quantitative values was not different between set 1 and set 2 because there were no false-positive cases in the selective upgrade of BI-RADS category 3 lesions. In our study, 65.6% (44/67) BI-RADS category 4a masses were downgraded to BI-RADS category 3 if one or none of the three parameters including Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI exceeded the cutoff values. Moreover, 38 of the 67 (56.7%) category 4a lesions were correctly downgraded to category 3 and could avoid unnecessary biopsies, consistent with prior studies comparing the additional value of elastography for reducing 46.0–85.7% of unnecessary benign biopsies (2,4,21,22). This represents the clinical utility of the combination of quantitative SWE and SMI values with B-mode US by reducing false-positives results. In our study, except for one false-negative case with a 12-mm-diameter DCIS, all false-negative cases including two cases of DCIS and three cases of invasive ductal carcinoma were less than 10 mm in diameter. Our results showed similar results with the previous study that reported that the false-negative results in the quantitative parameters of SWE were associated with pure DCIS and small-sized (< 10 mm) and low-grade invasive cancer (41). Considering that SWE and SMI have limitations in assessing small-sized, low-grade invasive cancers or pure DCIS, downgrading of lesions based on these quantitative parameters should be carefully applied.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study design that included a limited number of patients; hence, the possibility of selection bias cannot be excluded. Second, inter- or intra-observer variability was possibly attributed to the different SWE or SMI cutoff values. Third, since this study investigated only the quantitative values of SWE and SMI, there may be a difference in diagnostic performance compared to the use of a combination of qualitative features. A prospective study evaluating the diagnostic performance of the combined use of SWE and SMI quantitative parameters in addition to B-mode US is in progress, and a large-scale, multicenter prospective study is required.

In conclusion, the addition of all quantitative parameters for the Emax, Eratio, and SMIVI to B-mode US more significantly improved the diagnostic performance in differentiating benign from malignant breast lesions compared to B-mode US alone. Although careful application is required to small-sized (< 10 mm) mass, pure DCIS, or low-grade invasive cancer, the additional use of the quantitative values for SWE and SMI could increase specificity without significant sensitivity difference in diagnosing breast masses.

Footnotes

This work received Soonchunhyang University research funding (No. 20200017).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee EJ, Jung HK, Ko KH, Lee JT, Yoon JH. Diagnostic performances of shear wave elastography: which parameter to use in differential diagnosis of solid breast masses? Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1803–1811. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2782-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Au FW, Ghai S, Lu FI, Moshonov H, Crystal P. Quantitative shear wave elastography: correlation with prognostic histologic features and immunohistochemical biomarkers of breast cancer. Acad Radiol. 2015;22:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang JM, Moon WK, Cho N, Yi A, Koo HR, Han W, et al. Clinical application of shear wave elastography (SWE) in the diagnosis of benign and malignant breast diseases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1627-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gweon HM, Youk JH, Son EJ, Kim JA. Visually assessed colour overlay features in shear-wave elastography for breast masses: quantification and diagnostic performance. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:658–663. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans A, Whelehan P, Thomson K, McLean D, Brauer K, Purdie C, et al. Quantitative shear wave ultrasound elastography: initial experience in solid breast masses. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R104. doi: 10.1186/bcr2787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seo M, Ahn HS, Park SH, Lee JB, Choi BI, Sohn YM, et al. Comparison and combination of strain and shear wave elastography of breast masses for differentiation of benign and malignant lesions by quantitative assessment: preliminary study. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:99–109. doi: 10.1002/jum.14309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Youk JH, Gweon HM, Son EJ. Shear-wave elastography in breast ultrasonography: the state of the art. Ultrasonography. 2017;36:300–309. doi: 10.14366/usg.17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng WL, Rahmat K, Fadzli F, Rozalli FI, Mohd-Shah MN, Chandran PA, et al. Shearwave elastography increases diagnostic accuracy in characterization of breast lesions. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e3146. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu B, Zheng Y, Huang G, Lin M, Shan Q, Lu Y, et al. Breast lesions: quantitative diagnosis using ultrasound shear wave elastography—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi XQ, Li JL, Wan WB, Huang Y. A set of shear wave elastography quantitative parameters combined with ultrasound BI-RADS to assess benign and malignant breast lesions. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:960–966. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg WA, Mendelson EB, Cosgrove DO, Doré CJ, Gay J, Henry JP, et al. Quantitative maximum shear-wave stiffness of breast masses as a predictor of histopathologic severity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:448–455. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.13448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Youk JH, Son EJ, Gweon HM, Kim H, Park YJ, Kim JA. Comparison of strain and shear wave elastography for the differentiation of benign from malignant breast lesions, combined with B-mode ultrasonography: qualitative and quantitative assessments. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:2336–2344. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2014.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Chang JM, Kim WH, Bae MS, Seo M, Koo HR, et al. Added value of shear-wave elastography for evaluation of breast masses detected with screening US imaging. Radiology. 2014;273:61–69. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14132443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ko KH, Jung HK, Kim SJ, Kim H, Yoon JH. Potential role of shear-wave ultrasound elastography for the differential diagnosis of breast non-mass lesions: preliminary report. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:305–311. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-3034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Au FW, Ghai S, Moshonov H, Kahn H, Brennan C, Dua H, et al. Diagnostic performance of quantitative shear wave elastography in the evaluation of solid breast masses: determination of the most discriminatory parameter. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;203:W328–W336. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.11693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Youk JH, Gweon HM, Son EJ, Han KH, Kim JA. Diagnostic value of commercially available shear-wave elastography for breast cancers: integration into BI-RADS classification with subcategories of category 4. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:2695–2704. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2873-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ZL, Li JL, Li M, Huang Y, Wan WB, Tang J. Study of quantitative elastography with supersonic shear imaging in the diagnosis of breast tumours. Radiol Med. 2013;118:583–590. doi: 10.1007/s11547-012-0903-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Evans A, Whelehan P, Thomson K, McLean D, Brauer K, Purdie C, et al. Invasive breast cancer: relationship between shear-wave elastographic findings and histologic prognostic factors. Radiology. 2012;263:673–677. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans A, Whelehan P, Thomson K, Brauer K, Jordan L, Purdie C, et al. Differentiating benign from malignant solid breast masses: value of shear wave elastography according to lesion stiffness combined with greyscale ultrasound according to BI-RADS classification. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:224–229. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg WA, Cosgrove DO, Doré CJ, Schäfer FK, Svensson WE, Hooley RJ, et al. Shear-wave elastography improves the specificity of breast US: the BE1 multinational study of 939 masses. Radiology. 2012;262:435–449. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Athanasiou A, Tardivon A, Tanter M, Sigal-Zafrani B, Bercoff J, Deffieux T, et al. Breast lesions: quantitative elastography with supersonic shear imaging—Preliminary results. Radiology. 2010;256:297–303. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10090385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park AY, Seo BK. Up-to-date Doppler techniques for breast tumor vascularity: superb microvascular imaging and contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Ultrasonography. 2018;37:98–106. doi: 10.14366/usg.17043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park AY, Seo BK, Woo OH, Jung KS, Cho KR, Park EK, et al. The utility of ultrasound superb microvascular imaging for evaluation of breast tumour vascularity: comparison with colour and power Doppler imaging regarding diagnostic performance. Clin Radiol. 2018;73:304–311. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2017.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang XY, Zhang L, Li N, Zhu QL, Li JC, Sun Q, et al. Vascular index measured by smart 3-D superb microvascular imaging can help to differentiate malignant and benign breast lesion. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:5481–5487. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S203376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park AY, Kwon M, Woo OH, Cho KR, Park EK, Cha SH, et al. A prospective study on the value of ultrasound microflow assessment to distinguish malignant from benign solid breast masses: association between ultrasound parameters and histologic microvessel densities. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20:759–772. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.0515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendelson EB, Böhm-Vélez M, Berg WA, Whitman GJ, Feldman MI, Madjar H, et al. ACR BI-RADS ultrasound. In: D'Orsi CJ, Sickles EA, Mendelson EB, Morris EA, editors. ACR BI-RADS atlas, breast imaging reporting and data system. 5th ed. Reston: American College of Radiology; 2013. pp. 1–173. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee SH, Chung J, Choi HY, Choi SH, Ryu EB, Ko KH, et al. Evaluation of screening US-detected breast masses by combined use of elastography and color Doppler US with B-mode US in women with dense breasts: a multicenter prospective study. Radiology. 2017;285:660–669. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017162424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi JS, Han BK, Ko EY, Ko ES, Shin JH, Kim GR. Additional diagnostic value of shear-wave elastography and color Doppler US for evaluation of breast non-mass lesions detected at B-mode US. Eur Radiol. 2016;26:3542–3549. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-4201-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Youk JH, Gweon HM, Son EJ, Chung J, Kim JA, Kim EK. Three-dimensional shear-wave elastography for differentiating benign and malignant breast lesions: comparison with two-dimensional shear-wave elastography. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1519–1527. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2736-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SH, Chang JM, Kim WH, Bae MS, Cho N, Yi A, et al. Differentiation of benign from malignant solid breast masses: comparison of two-dimensional and three-dimensional shear-wave elastography. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:1015–1026. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu YC, Zhang Y, Deng SH, Jiang Q. Diagnostic performance of superb microvascular imaging (SMI) combined with shear-wave elastography in evaluating breast lesions. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:5935–5942. doi: 10.12659/MSM.910399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim GR, Choi JS, Han BK, Ko EY, Ko ES, Hahn SY. Combination of shear-wave elastography and color Doppler: feasible method to avoid unnecessary breast excision of fibroepithelial lesions diagnosed by core needle biopsy. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0175380. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho N, Jang M, Lyou CY, Park JS, Choi HY, Moon WK. Distinguishing benign from malignant masses at breast US: combined US elastography and color doppler US—Influence on radiologist accuracy. Radiology. 2012;262:80–90. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhan J, Diao XH, Jin JM, Chen L, Chen Y. Superb microvascular imaging—A new vascular detecting ultrasonographic technique for avascular breast masses: a preliminary study. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yongfeng Z, Ping Z, Wengang L, Yang S, Shuangming T. Application of a novel microvascular imaging technique in breast lesion evaluation. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao XY, Chen X, Guan XF, Wu H, Qin W, Luo BM. Superb microvascular imaging in diagnosis of breast lesions: a comparative study with contrast-enhanced ultrasonographic microvascular imaging. Br J Radiol. 2016;89:20160546. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park AY, Seo BK, Cha SH, Yeom SK, Lee SW, Chung HH. An innovative ultrasound technique for evaluation of tumor vascularity in breast cancers: superb micro-vascular imaging. J Breast Cancer. 2016;19:210–213. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2016.19.2.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma Y, Li G, Li J, Ren WD. The diagnostic value of superb microvascular imaging (SMI) in detecting blood flow signals of breast lesions: a preliminary study comparing SMI to color Doppler flow imaging. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1502. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barr RG, Nakashima K, Amy D, Cosgrove D, Farrokh A, Schafer F, et al. WFUMB guidelines and recommendations for clinical use of ultrasound elastography: part 2: breast. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2015;41:1148–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vinnicombe SJ, Whelehan P, Thomson K, McLean D, Purdie CA, Jordan LB, et al. What are the characteristics of breast cancers misclassified as benign by quantitative ultrasound shear wave elastography? Eur Radiol. 2014;24:921–926. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-3079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]