Abstract

Purpose

Pathogenic variants affecting MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 cause Lynch syndrome and result in different but imprecisely known cancer risks. This study aimed to provide age and organ-specific cancer risks according to gene and gender and to determine survival after cancer.

Methods

We conducted an international, multicenter prospective observational study using independent test and validation cohorts of carriers of class 4 or class 5 variants. After validation the cohorts were merged providing 6350 participants and 51,646 follow-up years.

Results

There were 1808 prospectively observed cancers. Pathogenic MLH1 and MSH2 variants caused high penetrance dominant cancer syndromes sharing similar colorectal, endometrial, and ovarian cancer risks, but older MSH2 carriers had higher risk of cancers of the upper urinary tract, upper gastrointestinal tract, brain, and particularly prostate. Pathogenic MSH6 variants caused a sex-limited trait with high endometrial cancer risk but only modestly increased colorectal cancer risk in both genders. We did not demonstrate a significantly increased cancer risk in carriers of pathogenic PMS2 variants. Ten-year crude survival was over 80% following colon, endometrial, or ovarian cancer.

Conclusion

Management guidelines for Lynch syndrome may require revision in light of these different gene and gender-specific risks and the good prognosis for the most commonly associated cancers.

Keywords: Lynch syndrome, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2

INTRODUCTION

Lynch syndrome (LS) results from pathogenic variants in the mismatch repair (MMR) genes and is the most common hereditary cancer syndrome, affecting an estimated 1 in 300 individuals. Pathogenic variants in each of the MMR genes path_MLH1, path_MSH2, path_MSH6, and path_PMS2 result in different risks for cancers in organs including the colorectum, endometrium, ovaries, stomach, small bowel, bile duct, pancreas, and upper urinary tract. Accurate estimates of these risks are essential for planning appropriate approaches to the prevention or early diagnosis of cancers but the robustness of previous studies has been limited by factors including retrospective design,1,2 lack of validation in independent cohorts,3–5 and inconsistent classification of genetic variants. Unexpected findings from previous studies have included path_MLH1 and path_MSH2 carriers appearing to have a lifetime risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) of approximately 50%, despite surveillance colonoscopy,6–8 and that shorter intervals between colonoscopies do not seem to reduce the incidence of CRC in LS.9,10 These findings challenge the assumptions that CRC in LS usually develops from a noninfiltrative adenoma precursor and that CRC can be prevented by colonoscopic detection and removal of adenomas in the colon and rectum. Additionally, previous studies in the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database (PLSD) have shown no increase in cancer risk in path_PMS2 carriers before 40 years of age and, although observation years were limited in older path_PMS2 carriers, LS-associated cancers other than endometrial and prostate were not observed.6–8

In this study we collected prospective data from a new large cohort of path_MMR carriers to validate previous findings from PLSD. We also updated information on the original cohort to ensure consistent classification of pathogenicity of MMR gene variants. We then combined both data sets, providing larger numbers that allowed us to derive more precise risk estimates for cancers in LS categorized by gene and gender.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Recruitment and follow-up

The PLSD database design and its inclusion criteria have been described previously in detail.6–8 This study was a prospective observational study without a control group in which we counted cancers detected during follow-up in 6350 carriers of path_MMR variants.

Carriers, including probands and their relatives, were recruited for prospective follow-up in each participating center. Genetic variants were assumed to be inherited and were found by genetic testing either prior to, at, or after inclusion for follow-up. Inclusion was from the first prospectively planned and completed colonoscopy and all recruits had subsequent follow-up of one year or more. Any cancers that were diagnosed before or at the same age as the first prospectively planned and completed colonoscopy were scored as previous cancers. Time to first cancer after inclusion was calculated for each organ or groups of organs. For example, when calculating time to colon cancer, only cases without previous colon cancer were included and the first colon cancer after inclusion was scored as an event. When calculating the time to any cancer (penetrance), only patients without any cancer prior to or at inclusion were counted. For each calculation, each patient was censored at the first event or last observation, whichever came first. Thus, there is no information in this report on synchronous or metachronous cancer(s) in the same organ or group of organs.

The independent cohort of path_MMR carriers used for validation were recruited from newly participating centers and also included a small number of additional patients from previously contributing centers. Only carriers of variants confirmed as class 4 or 5 (clinically actionable) in the International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) database (https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes) were included and used for validation by comparison with the previously published cohort.

Before merging the previous and validation cohorts, all variants in the previous cohort were reassessed and only cases with variants now scored as class 4 or class 5 were included. Follow-up data for these cases were also updated, adding more follow-up years when possible.

All patients were followed up prospectively according to local clinical guidelines (summarized in Table S1). Follow-up protocols, compliance and stage of cancers at diagnosis were not study parameters for this report but will be the focus of future studies proposed for PLSD. Each patient was censored at the age at which the last information was available, which might have been a colonoscopy, any other clinical examination, a report from an examination done by others, or information that the patient had died, whichever came last. Observation time was censored at organ removal (therapeutic or prophylactic) when calculating incidences for cancer in specific organs.

The following information was used for analyses: gender, path_MMR variant, age at inclusion, age at last update, age at any cancer, type of cancer as indicated by the first three positions in the International Classification of Diseases version 9 (ICD-9) diagnostic system and age at death. All cancer diagnoses, including cancers identified prior to or at inclusion, were based upon clinical and histopathological reports at the collaborating centers and were recorded for each carrier.

Statistical methods

Annual incidence rates (AIRs) by age were calculated in 5-year cohorts from 25 to 75 years of age. Cumulative incidence, denoted by Q, was computed starting at age 25, assuming zero incidence rate before age 25, using the formula Q(age) = Q(age − 1) + [1 − Q(age − 1)] × AIR(age) where AIR(age) is the annual incidence rate as estimated from the corresponding 5-year interval. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using the Lagrange multiplier test (details in online supplementary information S6). P values for differences between cumulative incidences were computed assuming standard normal distribution of Zdiff = Qdiff/SEQdiff. The results are the observed cumulative incidences of cancers. These may be considered as risks for cancers, and are described below as risks.

Survival after cancer was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier survival function as crude survival from age at diagnosis until last observation or death. Crude survival is influenced by many factors in old age, and inclusion for survival calculations was restricted to cases diagnosed before 65 years of age. This limited the numbers included when calculating survival for late onset cancers. Because of the serious prognosis for less frequent gastric, small intestine, bile duct, and pancreatic cancers, crude survival for earlier onset, more frequent cancers was right censored when such cancers were diagnosed to avoid underestimation of survival.

Ethics

The study adhered to the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Oslo University Hospital ethical committee ref. S-02030 and its data governance rules by the Norwegian Data Inspectorate ref. 2001/2988-2. Genetic testing was performed with informed consent according to local and national requirements and all reporting centers exported only de-identified data to PLSD.

RESULTS

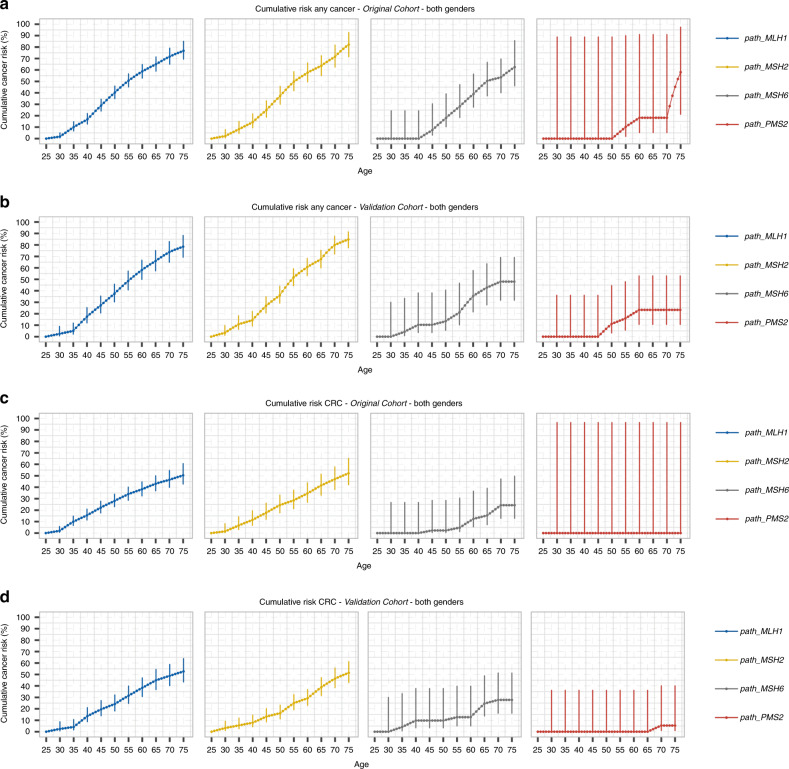

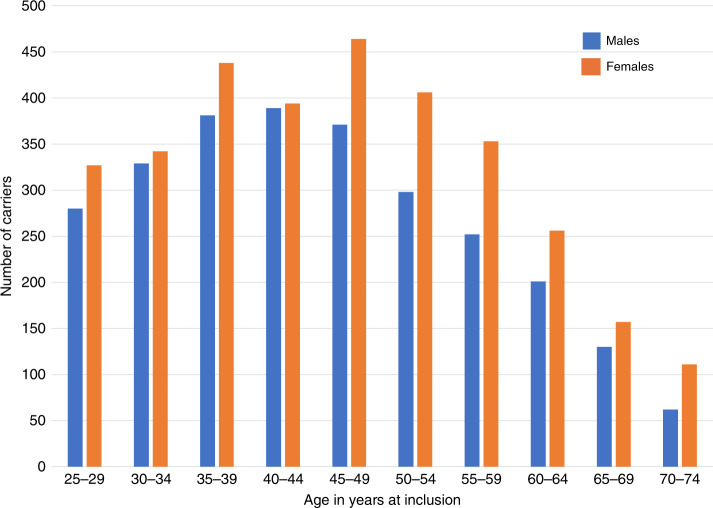

The newly recruited validation cohort included 3527 path_MMR carriers and 26,682 observation years while the original cohort included 2823 path_MMR carriers and 24,964 follow-up years after updating. In the validation cohort, neither cumulative risk for any cancer (penetrance) nor cumulative risk for CRC for each MMR gene differed significantly from those in the original PLSD cohort6–8 (P > 0.05 at all ages, see Fig. 1 and Table S2). Upon merger of the new and original cohorts, the combined data set comprised 6350 path_MMR carriers, 3480 females and 2870 males, who were included from a mean age of 46.8 years (range 25–74 years, Fig. 2) providing 51,646 observation years. There were 2607 (41.1%) path_MLH1 carriers, 2495 (39.3%) path_MSH2, 841 (13.2%) path_MSH6, and 407 (6.4%) path_PMS2 (Table S3).

Fig. 1.

Cummulative risk of any cancer and of colorectal cancer in orginal and validation cohorts. Cumulative risk of any cancer: a original cohort,6 b validation cohort; and cumulative risk of colorectal cancer (CRC): c original cohort6 and d validation cohort. There were no significant differences between original and validation cohorts. Center values are means and error bars show 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Fig. 2.

Age and sex of patients at inclusion in the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database (PLSD).

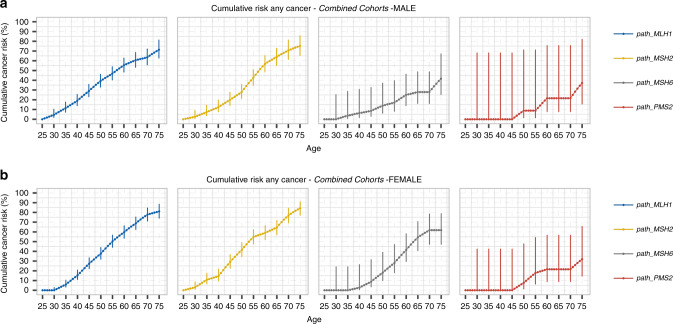

During prospective observation, 1808 cancers were diagnosed (Table S4). Cancers of the colon (n = 580, 32.1% of all cancers), skin (n = 215, 11.9%), endometrium (n = 173, 9.6%), and rectum (n = 127, 7.0%) were most frequent. Skin cancers were not systematically reported the same way by all centers and skin cancers were not included in the results presented below. The combined data set included sufficient observation years and events to calculate precise AIRs (Table S5) by gender from 25 to 75 years of age and cumulative incidences of cancers by age and gender, for organ groups or each organ separately (Table 1). The cumulative incidence of any first cancer (penetrance) by gene and gender is presented in Fig. 3. The highest cancer risks were found in path_MLH1 and path_MSH2 carriers. The overall penetrance for path_MSH6 variants was significantly lower in males than females (p < 0.0001 at 70 years of age): both genders had similar, modestly increased risks for CRC, while females had high risks for gynecological cancers. Thus, path_MSH6 variants caused a sex-limited trait with high penetrance in females but only an 18% lifetime risk for CRC in males, limiting the utility of family history for identification of path_MSH6-associated LS. Notably, the risk of cancer for path_PMS2 carriers was not increased at all before 50 years of age, and only nonsignificantly increased at older ages. Breast cancer risks were very similar across all four genes, with cumulative risks to age 60 and 75 years of 7.0–8.1% and 12.3–15.1% representing only a marginal increase compared with reported general population risks.

Table 1.

Cumulative cancer incidences stratified by age, path_MMR variant, and gender (except path_PMS2 where cancer other than gynecological and prostate are combined for both genders)

| Cumulative incidence at age (% [95% CI]) | |||||||||

| path_MLH1 | path_MSH2 | path_MSH6 | path_PMS2 | ||||||

| ICD-9 | Organ | Age | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Both |

| Any cancer | 30 |

0 [0–2.8] |

4.5 [1.9–10.2] |

3.0 [1.0–8.5] |

2.6 [0.7–9.0] |

0 [0–24.0] |

0 [0–25.3] |

0 [0–32.0] |

|

| 40 |

15.3 [11.1–20.8] |

18.9 [13.9–25.5] |

14.6 [9.7–21.6] |

12.3 [7.7–19.7] |

2.7 [0.5–26.3] |

6.3 [1.7–30.6] |

0 [0–32.0] |

||

| 50 |

37.7 [32.0–43.9] |

39.2 [33.0–46.1] |

41.5 [34.7–49.1] |

27.8 [21.3–35.8] |

18.2 [10.0–39.0] |

14.0 [6.2–37.0] |

8.2 [2.3–38.3] |

||

| 60 |

59.7 [53.5–66.1] |

55.4 [48.5–62.7] |

59.0 [51.9–66.3] |

56.7 [48.6–65.3] |

41.4 [29.6–58.0] |

25.0 [14.0–46.2] |

21.7 [11.1–48.2] |

||

| 70 |

77.8 [71.1–84.5] |

63.5 [55.9–72.1] |

76.9 [69.3–84.3] |

70.6 [61.4–81.3] |

61.8 [47.3–78.3] |

27.9 [16.2–48.7] |

21.7 [11.1–48.2] |

||

| 75 |

81.0 [74.1–88.4] |

71.4 [62.8–81.3] |

84.3 [77.1–91.0] |

75.2 [65.6–85.7] |

61.8 [47.3–78.3] |

41.7 [25.4–67.1] |

34.1 [19.0–59.6] |

||

| 153, 154 | Colorectal | 30 |

0 [0–2.8] |

4.5 [1.9–10.1] |

1.9 [0.5–6.7] |

2.6 [0.7–9.0] |

0 [0–23.7] |

0 [0–25.3] |

0 [0–32.0] |

| 40 |

11.8 [8.2–16.9] |

16.4 [11.8–22.9] |

6.9 [3.8–12.5] |

9.9 [5.8–17.0] |

2.5 [0.4–25.9] |

6.3 [1.7–30.6] |

0 [0–32.0] |

||

| 50 |

20.8 [16.2–26.4] |

33.6 [27.6–40.5] |

16.9 [12.2–23.3] |

18.1 [12.7–25.6] |

4.4 [1.2–27.4] |

6.3 [1.7–30.6] |

0 [0–32.0] |

||

| 60 |

32.2 [26.7–38.6] |

45.2 [38.5–52.6] |

26.2 [20.6–33.0] |

34.1 [26.8–42.9] |

8.9 [3.9–31.0] |

8.9 [3.1–32.8] |

0 [0–32.0] |

||

| 70 |

44.1 [37.4–51.8] |

52.8 [45.2–61.6] |

41.9 [34.9–49.7] |

46.3 [36.9–58.8] |

20.3 [11.8–40.5] |

11.7 [4.7–35.2] |

3.4 [0.6–34.5] |

||

| 75 |

48.3 [40.9–57.4] |

57.1 [48.7–67.9] |

46.6 [39.1–55.4] |

51.4 [41.0–65.0] |

20.3 [11.8–40.5] |

18.2 [7.9–43.2] |

10.4 [2.9–40.8] |

||

| 182 | Endometrium | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–22.6] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||

| 40 |

1.9 [0.8–4.8] |

2.3 [0.9–6.2] |

2.3 [0.4–24.6] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||||

| 50 |

14.7 [11–19.5] |

17.5 [12.8–23.7] |

12.6 [6.3–33.1] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||||

| 60 |

27.3 [22.1–33.6] |

38.0 [30.9–46.2] |

28.3 [18.2–46.5] |

9.3 [3.3–47.3] |

|||||

| 70 |

35.2 [28.8–43.4] |

46.5 [38.3–56.3] |

41.1 [28.6–57.9] |

12.8 [5.2–49.5] |

|||||

| 75 |

37.0 [30.1–46.5] |

48.9 [40.2–60.7] |

41.1 [28.6–61.5] |

12.8 [5.2–49.5] |

|||||

| 183 | Ovaries | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–22.6] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||

| 40 |

2.0 [0.9–5.0] |

2.2 [0.9–6.0] |

2.3 [0.4–24.6] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||||

| 50 |

6.1 [3.8–9.8] |

10.5 [6.9–15.7] |

2.3 [0.4–24.6] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||||

| 60 |

10.1 [6.8–15.1] |

12.6 [8.5–18.4] |

2.3 [0.4–24.6] |

3.0 [0.5–43.3] |

|||||

| 70 |

11.0 [7.4–17.1] |

17.4 [11.8–27.3] |

10.8 [3.7–32.9] |

3.0 [0.5–43.3] |

|||||

| 75 |

11.0 [7.4–19.7] |

17.4 [11.8–31.2] |

10.8 [3.7–38.6] |

3.0 [0.5–43.3] |

|||||

| 151, 152, 156, 157 | Stomach, small bowel, bile duct, gallbladder and pancreas | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

| 40 |

1.2 [0.4–4.0] |

0.8 [0.2–4.0] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 50 |

1.8 [0.7–4.7] |

2.1 [1.0–5.4] |

2.2 [1.0–5.7] |

1.2 [0.4–5.5] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

2.0 [0.4–32.4] |

||

| 60 |

4.5 [2.7–7.8] |

5.1 [3.1–8.8] |

5.4 [3.3–9.3] |

7.1 [4.5–11.9] |

0 [0–22.4] |

4.0 [1.1–26.2] |

2.0 [0.4–32.4] |

||

| 70 |

8.4 [5.5–13.0] |

15.7 [11.2–22.0] |

9.8 [6.7–14.5] |

15.9 [11.3– 22.4] |

1.7 [0.3– 23.8] |

4.0 [1.1–26.2] |

3.6 [1.0–33.5] |

||

| 75 |

11.0 [7.4–16.9] |

21.8 [16.0–29.9] |

12.8 [8.8–19.3] |

19.5 [14.0–27.6] |

4.2 [1.2–26.0] |

7.9 [2.7–30.0] |

3.6 [1.0–33.5] |

||

| 189 | Ureter and kidney | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

| 40 |

0.4 [0.1–3.0] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 50 |

0.6 [0.2–3.3] |

1.0 [0.3–4.2] |

2.2 [1.0–5.7] |

2.4 [1.1–6.8] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 60 |

0.9 [0.3–3.7] |

1.7 [0.7 –5.0] |

5.1 [3.1–8.9] |

8.3 [5.5–13.1] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

1.7 [0.3–24.3] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 70 |

2.9 [1.4–6.3] |

3.7 [1.9–7.9] |

13.3 [9.4–18.8] |

16.2 [11.6–22.6] |

5.5 [2.2–26.9] |

1.7 [0.3–24.3] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 75 |

3.8 [1.9–8.4] |

4.9 [2.5–10.6] |

18.7 [13.5–26.5] |

17.6 [12.6–25.3] |

5.5 [2.2–26.9] |

1.7 [0.3–24.3] |

3.7 [0.7–33.8] |

||

| 188 | Urinary bladder | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

| 40 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0.6 [0.1–4.1] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 50 |

0.3 [0.1–2.9] |

0.6 [0.2–3.8] |

2.1 [0.9–5.7] |

1.6 [0.6–5.9] |

0 [0–22.4] |

4.3 [1.2–26.5] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 60 |

1.0 [0.3–3.7] |

2.2 [1.0–5.6] |

3.2 [1.6–6.9] |

6.1 [3.7–10.8] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

4.3 [1.2–26.5] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 70 |

2.7 [1.2–6.2] |

4.6 [2.5–8.7] |

6.8 [4.2–11.3] |

8.7 [5.5–13.8] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

4.3 [1.2–26.5] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 75 |

5.4 [2.8–10.9] |

6.8 [3.8–13.0] |

7.9 [4.8–13.6] |

12.8 [8.3–21.0] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

8.0 [2.7–30.0] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 185 | Prostate | 30 |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–65.9] |

|||

| 40 |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–65.9] |

|||||

| 50 |

0.3 [0.1–3.5] |

0.8 [0.2–5.1] |

0 [0–22.9] |

4.6 [0.8–67.5] |

|||||

| 60 |

3.2 [1.6–6.8] |

6.3 [3.8–11.0] |

0 [0–22.9] |

4.6 [0.8–67.5] |

|||||

| 70 |

7.0 [4.2–11.9] |

15.9 [11.2–22.5] |

4.8 [1.3–27.0] |

4.6 [0.8–67.5] |

|||||

| 75 |

13.8 [8.8–21.7] |

23.8 [17.2– 33.2] |

8.9 [3.1–31.0] |

4.6 [0.8–67.5] |

|||||

| 174 | Breast | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||

| 40 |

0.4 [0.1–3.0] |

1.1 [0.3–4.6] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||||

| 50 |

2.4 [1.2–5.3] |

3.3 [1.7–7.1] |

1.7 [0.3–23.7] |

0 [0–41.4] |

|||||

| 60 |

7.0 [4.6–10.5] |

7.3 [4.7–11.5] |

6.7 [2.9–27.9] |

8.1 [2.8–46.5] |

|||||

| 70 |

10.5 [7.4–15.1] |

12.6 [8.9–17.8] |

11.1 [5.8–31.5] |

8.1 [2.8–46.5] |

|||||

| 75 |

12.3 [8.6–17.9] |

14.6 [10.3– 21.1] |

13.7 [7.4–33.8] |

15.2 [5.9- 51.5] |

|||||

| 191 | Brain | 30 |

0 [0–2.6] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0 [0–3.3] |

0 [0–4.3] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

| 40 |

0.4 [0.1–3.0] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0.6 [0.1–4.1] |

0.7 [0.1–5.1] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 50 |

0.6 [0.2–3.3] |

0 [0–3.1] |

0.6 [0.1–4.1] |

1.1 [0.3–5.5] |

0 [0–22.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 60 |

0.9 [0.3–3.7] |

0 [0–3.1] |

1.4 [0.5–4.9] |

1.9 [0.8–6.4] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

0 [0–22.9] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 70 |

1.6 [0.6–4.6] |

0.7 [0.1–4.2] |

1.8 [0.7–5.4] |

3.7 [1.8–8.4] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

1.8 [0.3–24.4] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

| 75 |

1.6 [0.6–5.3] |

0.7 [0.1–5.2] |

2.9 [1.2–7.9] |

7.7 [4.1–15.2] |

1.2 [0.2–23.4] |

1.8 [0.3–24.4] |

0 [0–30.9] |

||

CI confidence interval, ICD-9 International Classification of Diseases version 9 diagnostic system.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative risk for any cancer (penetrance) of path_MMR gene variants causing Lynch syndrome by gender. a cumulative risk of any cancer for each LS gene in males, b cumulative risk of any cancer for each LS gene in females. Path_MSH6 had significantly higher penetrance in females compared with males. Center values are means and error bars show 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The risks of colon, stomach, small bowel, bile duct, gallbladder, and pancreatic cancers were higher for male than female path_MLH1 carriers. In early adult life, path_MSH2 carriers of both genders had the same high risk for CRC. At older ages, carriers of path_MSH2 variants (including survivors of early cancers) were at relatively high risk of upper urinary tract cancers, prostate cancer, upper gastrointestinal cancer, and brain tumors.

Five- and 10-year crude survival after cancers in different organs that were diagnosed after inclusion and before 65 years of age in path_MLH1, path_MSH2, and path_MSH6 carriers are presented in Table 2. Most patients survived ten years or more following cancers of the colon (88%), rectum (70%), endometrium (89%), ovary (84%), prostate (70%) breast (82%), upper urinary tract (67%), or urinary bladder (68%), but not after pancreatic (29%), bile duct (42%), or brain (15%) cancers.

Table 2.

Crude survival (%) after selected cancers diagnosed after initiation of colonoscopy surveillance and before age 65 years for path_MLH1, path_MSH2, and path_MSH6 carriers

| Cancer | Organ | n | 5-year survival (%) | 95% CI (%) | 10-year survival (%) | 95% CI (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectala | ||||||

| Colon | 274 | 95 | [90–97] | 88 | [81–93] | |

| Rectal and sigmoid | 62 | 75 | [61–85] | 70 | [52–82] | |

| Gynecologicala | ||||||

| Endometrium | 136 | 89 | [82–94] | 89 | [82–94] | |

| Ovarian | 41 | 84 | [68–93] | 84 | [68–93] | |

| Urinary tracta | ||||||

| Ureter and kidney | 53 | 86 | [71–94] | 67 | [41–84] | |

| Urinary bladder | 31 | 81 | [60–92] | 68 | [42–84] | |

| Others | ||||||

| Prostatea | 26 | 96 | [75–99] | 70 | [37–88] | |

| Breasta | 51 | 92 | [78–98] | 82 | [64–92] | |

| Stomach | 15 | 72 | [47–86] | 72 | [47–86] | |

| Small bowel | 24 | 81 | [59–92] | 71 | [41–87] | |

| Biliary tract | 8 | 42 | [15–67] | 42 | [15–67] | |

| Pancreas | 6 | 29 | [6–58] | 29 | [6–58] | |

| Brain | 2 | 15 | [2–37] | 15 | [2–37] | |

CI confidence interval.

aRight censored for International Classification of Diseases version 9 (ICD-9) diagnostic system 151, 152, 156, or 157.

DISCUSSION

This study first determined prospectively observed cancer risks and survival in cohort of 3527 path_MMR carriers newly recruited to PLSD. This validated findings reported previously in the similarly sized original PLSD cohort, allowing us to combine both sets of data, providing a series of 6350 genetically confirmed cases in which we calculated more precise cancer risks than have been available before by age, gene, and gender. Factors that might have reduced observed cancer risks in this series included colonoscopy with polypectomy and possible use of aspirin, including participation in clinical trials. As the series was censored for therapeutic or prophylactic organ removal, these measures are less likely to have impacted the findings. Partial colectomy or surgery for rectal cancer were demonstrated previously to have little effect on risk for subsequent colon cancer in the original cohort.7 Survivorship biases may also be present given the long follow-up of some cases. Conversely, the use of family and personal history of cancer to identify path_MMR carriers for follow-up could have selected for coexisting non-LS cancer predisposing genetic variants and/or environmental factors that may have increased observed cancer incidences. This study therefore provides averaged risk estimates for cancers in path_MMR carriers identified and followed up by expert centers in 18 countries. Although geography and differences in follow-up practices might impact cancer risks, no significant differences were identified between the original cohort recruited in Europe but excluding Germany and the validation cohort recruited mainly in Germany, the Americas, and Australasia. Neither did differences between countries in policy on colonoscopic surveillance interval impact colorectal cancer incidence in a previous PLSD study.9

Notably, in the current study no colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, or urinary tract cancers were observed before 50 years of age in path_PMS2 carriers, giving even lower point estimates than have been reported previously.6–8,11–13 We conclude that although path_PMS2 variants have been shown robustly to cause a rare recessively inherited cancer syndrome of childhood and adolescence termed constitutional mismatch repair deficiency (CMMRD) syndrome (https://www.omim.org/entry/276300), the cancer risk in heterozygotes is not increased in young to middle-aged adults and remains uncertain in older individuals. The relative lack of follow-up years for path_PMS2 carriers is a weakness of the current study and further expansion of this group in PLSD would be particularly helpful. Recent studies have suggested that path_PMS2 variants may not enhance initiation of CRC tumorigenesis but instead, PMS2 protein deficiency may favor progression of MMR proficient adenomas to CRC.14 If this is correct, surveillance and polypectomy could be more effective in preventing CRC in path_PMS2 carriers than in other LS patients and may be a factor in the low incidence of CRC in path_PMS2 carriers in this study, but cannot explain the low incidence of the other LS-associated cancers.

Our results confirmed that female path_MSH6 carriers are at high risk of cancer of the endometrium compared with other organs and that the CRC risk associated with path_MSH6 is lower than that in path_MLH1 and path_MSH2 carriers. As only a minority of males with path_MSH6 variants will develop LS-associated cancers, “skipped generations” will be common in path_MSH6 families and such families are not identified efficiently by current clinical criteria for LS that assume high penetrance in both genders.15 Testing of incident endometrial cancers for MMR deficiency, as has been adopted widely for CRC, may provide a more effective strategy to identify path_MSH6 families.16 Recently reported significant increases in breast cancer risk in MSH6- and PMS2-associated LS17 were not confirmed in this study.

Based on the differences in cancer risks associated with the four path_MMR genes, we propose that LS should now be considered as a generic term for four clinically distinct inherited cancer risk syndromes. Our findings suggest that carriers of path_PMS2 variants should not be grouped together with carriers of path_MLH1 and path_MSH2 for genetic counseling or clinical management, and the lower risk and later onset of CRC in path_MSH6 carriers may also justify specific guidelines for surveillance that are tailored to this genotype.16

If the goals of follow-up and surveillance in LS were to achieve good survival from CRC and gynecological cancers, our results might be viewed as evidence of success. However, as our study has no control group we cannot determine whether the apparently better survival of many cancers in LS patients than in patients with sporadic cancers reflects differences in cancer biology, cancer surveillance or treatment, or a combination of these factors. In a recent study in PLSD we found no association between colonoscopy interval and stage at diagnosis of CRC, suggesting that the traditional model of the adenoma–carcinoma sequence may not apply to all LS CRCs.18 In fact, the primary goal of surveillance in LS, as understood by most professionals and patients, has been to prevent CRC by removing visible precursor lesions in the colorectum. We have reported6–8 and now confirm that CRC continues to occur in LS even though the current surveillance guidelines are applied with preventive intention. The progressive development of colonoscopy techniques for detection of lesions that may have otherwise have been missed is a potential time trend confounder for our results, although it is not yet known whether these advances improve prevention of CRC in path_MMR carriers.

Gene and gender-specific risk estimates in LS are imperative for development of new clinical guidelines for stratified surveillance, management, and prevention of colorectal, endometrial, ovarian, and other cancers. The results of the current study provide a strong evidence base for developing such guidelines. Although we have shown previously that the occurrence of a first cancer in LS does not change significantly the risks for subsequent cancers,7 the excellent survival from the early onset and more frequent cancers in LS is leading to an increasing cohort of older path_MMR carriers who are at risk for cancers in other organs, some of which have worse prognoses. LS patients are therefore subject to competing cancer risks that may have impacted our results. By contrast, in previous generations, most LS patients died from their first cancer and an accurate picture of late onset cancers cannot be obtained from segregation analyses of historical data. The challenge of preventing or curing late onset cancers in LS must be addressed through prospective studies including interventional chemopreventive studies and new treatment modalities such as immunotherapy.

Available clinical approaches for identifying LS and criteria for the classification of pathogenicity of MMR gene variants were developed assuming that all pathogenic variants have high penetrance. This is neither the case for path_MSH6 variants in males nor for path_PMS2 carriers of either gender. The criteria used for inclusion in the current study—class 4 or 5 (i.e., clinically actionable) variants only—may have identified MSH6 and PMS2 variants with higher than “average” penetrance, and/or individuals and families with unidentified genetic or environmental modifiers that increase penetrance. We may need to develop different criteria for the identification and characterization of low-penetrance pathogenic variants.

In conclusion, the lifetime risk of CRC in path_MLH1 and path_MSH2 is approximately 50% despite attempted prevention by surveillance colonoscopy and polypectomy. Female path_MLH1, path_MSH2, and path_MSH6 carriers have a rapidly rising risk of gynecological cancers from 40 years of age. At older ages, path_MSH2 and path_MLH1 variants are associated with urinary tract and upper gastrointestinal cancers, and path_MSH2 carriers in particular are at increased risk for prostate cancer. The low incidence of CRC in path_MSH6 carriers causes a sex-limited trait with relatively low penetrance in males that will lead to families escaping detection by family history. Heterozygous carriers of path_PMS2 variants do not have increased risk for CRC, endometrial, or ovarian cancer before 50 years of age, and may have only marginally increased risks at older ages. International clinical guidelines for carriers of path_MMR variants should be revised in line with the cancer risks with which they are associated. The cancer risk algorithm at the PLSD website (www.plsd.eu) is based upon the results presented in this report and enables interactive calculation of remaining lifetime risks for cancer in any LS patient by giving their age, gender, and gene variant, thereby facilitating personalized medicine for path_MMR carriers. Future research should seek to address the reasons for continuing occurrence of CRC in LS despite supposedly preventive colonoscopy and the prevention and treatment of those LS cancers that continue to have a poor prognosis.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to Heikki Järvinen, Anna Lepistö, Beatriz Alcala-Repo, Teresa Ocaña, María Pellisé, Sabela Carballal, Liseth Rivero, Lorena Moreno, Gerhard Jung, Antoni Castells, Joaquin Cubiella, Laura Rivas, Luis Bujanda, Inés Gil, Jesús Bañales, Catalina Garau, Rodrigo Jover, María Dolores Picó, Xavier Bessa, Cristina Álvarez, Montserrat Andreu, Carmen Poves, Pedro Pérez Segura, Lucía Cid, Marta Carrillo, Enrique Quintero, Ángeles Pizarro, Marta Garzón, Adolfo Suárez, Inmaculada Salces, Daniel Rodriguez-Alcalde, Judith Balmaña, Adrià López, Nuria Dueñas, Gemma Llort, Carmen Yagüe, Teresa Ramón i Cajal, David Fisas Masferrer, Alexandra Gisbert Beamud, Consol López San Martín, Maite Herráiz, Pilar Pérez, Cristina Carretero, Maite Betés, Marta Ponce, Elena Aguirre, Nora Alfaro, Carlos Sarroca, and Marianne Haeusler for their efforts over the years. We also thank the Finnish Cancer Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, and the Norwegian Cancer Society, contract 194751–2017 for funding. D.G.E. and E.J.C are supported by the all Manchester National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215–20007). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under award number UM1CA167551 and through cooperative agreements with the following Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (CCFR) centers: Australasian Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health [NCI/NIH] U01 CA074778 and U01/U24 CA097735), Mayo Clinic Cooperative Family Registry for Colon Cancer Studies (NCI/NIH U01/U24 CA074800), Ontario Familial Colorectal Cancer Registry (NCI/NIH U01/U24 CA074783), Seattle Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (NCI/NIH U01/U24 CA074794), University of Hawaii Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (NCI/NIH U01/U24 CA074806 and R01 CA104132 to L.L.M.), University of Southern California (USC) Consortium Colorectal Cancer Family Registry (NCI/NIH U01/U24 CA074799). GC, MP and MN work was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and cofunded by FEDER funds -a way to build Europe- (grant SAF2015-68016-R), CIBERONC and the Government of Catalonia (grants 2017SGR1282 and PERIS SLT002/16/0037). The German Consortium for Familial Intestinal Cancer has been supported by grants from the German Cancer Aid. Data collection in Bonn was facilitated by the Center for Hereditary Tumor Syndromes, University of Bonn. F.B. is supported by grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI13/00719; PI16/00766) and from the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG). Data collection from Wales, UK was supported by the Wales Gene Park. This work was cofunded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). MN and StB were supported by a grant from the Dutch Cancer Society (DCS), grant number UL 2017-8223.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Julian R. Sampson, Mev Dominguez-Valentin, Toni T Seppälä.

Change history

7/20/2020

The original version of this Article did not contain details of Dutch Cancer Society (DCS) funding (grant number UL 2017-8223) in the Acknowledgements section. This has now been corrected in both the PDF and HTML versions of the Article.

Change history

7/20/2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41436-020-0892-4

Contributor Information

Mev Dominguez-Valentin, Email: mev.dominguez.valentin@rr-research.no.

Julian R. Sampson, Email: sampson@cardiff.ac.uk.

Toni T. Seppälä, Email: toni.seppala@fimnet.fi.

Supplementary information

The online version of this article (10.1038/s41436-019-0596-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Bonadona V, Bonaiti B, Olschwang S, et al. Cancer risks associated with germline mutations in MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6 genes in Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2011;305:2304–2310. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Engel C, Loeffler M, Steinke V, et al. Risks of less common cancers in proven mutation carriers with Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4409–4415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson P, Vasen HFA, Mecklin JP, et al. The risk of extra-colonic, extra-endometrial cancer in the Lynch syndrome. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:444–449. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vasen HF, Stormorken A, Menko FH, et al. MSH2 mutation carriers are at higher risk of cancer than MLH1 mutation carriers: a study of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer families. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4074–4080. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.20.4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aarnio M, Sankila R, Pukkala E, et al. Cancer risk in mutation carriers of DNA-mismatch-repair genes. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:214–218. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990412)81:2<214::AID-IJC8>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moller P, Seppala TT, Bernstein I, et al. Cancer risk and survival in path_MMR carriers by gene and gender up to 75 years of age: a report from the Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database. Gut. 2018;67:1306–1316. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moller P, Seppala T, Bernstein I, et al. Incidence of and survival after subsequent cancers in carriers of pathogenic MMR variants with previous cancer: a report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. Gut. 2017;66:1657–1664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moller P, Seppala T, Bernstein I, et al. Cancer incidence and survival in Lynch syndrome patients receiving colonoscopic and gynaecological surveillance: first report from the prospective Lynch syndrome database. Gut. 2017;66:464–472. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seppala T, Pylvanainen K, Evans DG, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence in path_MLH1 carriers subjected to different follow-up protocols: a Prospective Lynch Syndrome Database report. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2017;15:18. doi: 10.1186/s13053-017-0078-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engel C, Vasen HF, Seppala T, et al. No difference in colorectal cancer incidence or stage at detection by colonoscopy among 3 countries with different Lynch syndrome surveillance policies. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1400–1409. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ten Broeke SW, Brohet RM, Tops CM, et al. Lynch syndrome caused by germline PMS2 mutations: delineating the cancer risk. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:319–325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.8088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Senter L, Clendenning M, Sotamaa K, et al. The clinical phenotype of Lynch syndrome due to germ-line PMS2 mutations. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:419–428. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ten Broeke SW, van der Klift HM, Tops CMJ, et al. Cancer risks for PMS2-associated Lynch syndrome. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:2961–2968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ten Broeke SW, van Bavel TC, Jansen AML, et al. Molecular background of colorectal tumors from patients with Lynch syndrome associated with germline variants in PMS2. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:844–851. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sjursen W, Haukanes BI, Grindedal EM, et al. Current clinical criteria for Lynch syndrome are not sensitive enough to identify MSH6 mutation carriers. J Med Genet. 2010;47:579–585. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.077677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology, Society of Gynecologic Oncology. ACOG practice bulletin no. 147: Lynch syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:1042–1054. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000456325.50739.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roberts ME, Jackson SA, Susswein LR, et al. MSH6 and PMS2 germ-line pathogenic variants implicated in Lynch syndrome are associated with breast cancer. Genet Med. 2018;20:1167–1174. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seppälä TT, Ahadova A, Dominguez-Valentin M, et al. Lack of association between screening interval and cancer stage in Lynch syndrome may be accounted for by over-diagnosis; a prospective Lynch syndrome database report. Hered Cancer Clin Pract. 2019;17:8. doi: 10.1186/s13053-019-0106-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.