Abstract

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is a potentially lethal infection that affects mostly immunocompromised patients caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Echinocandins are a second-line therapy against IA, used as a salvage therapy as well as for empirical or prophylactic therapy. Although they cause lysis of growing hyphal tips, they are considered fungistatic against molds. In vivo echinocandins resistance is uncommon; however, its wide clinical use could shortly lead to the emergence of A. fumigatus resistance. The aims of the present work was to assess the development of reduced echinocandins susceptibility phenotype by a A. fumigatus strain and to unveil the molecular mechanism underlying such phenotype. We induced in vitro cross-resistance to echinocandins following exposure of A. fumigatus to anidulafungin. Stability of the resistant phenotype was confirmed after removal of anidulafungin pressure. The FKS1 gene was partially sequenced and a E671Q mutation was found. A computational approach suggests that it can play an important role in echinocandin resistance. Given the emerging importance of this mechanism for clinical resistance in pathogenic fungi, it would be prudent to be alert to the potential evolution of this resistant mechanism in Aspergillus spp infecting patients under echinocandins therapeutics.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Medical research

Introduction

Invasive aspergillosis (IA) is a potentially lethal infection afflicting mostly immunocompromised patients, the majority of cases caused by Aspergillus fumigatus. Early appropriate therapy is critical for the successful management. Echinocandins are clinically used in salvage therapy of IA as well as for empirical or prophylactic therapy1,2. Moreover, combination of voriconazole and anidulafungin (AFG) have been shown to be effective against azole-susceptible and azole-resistant A. fumigatus isolates3. The mechanism of action of echinocandins involves noncompetitive inhibition of (1,3)-β-D-glucan synthase, an essential enzyme involved in fungal cell wall synthesis. Echinocandins has been shown to cause lysis of growing hyphal tips but are considered fungistatic against moulds4. Elevated echinocandin Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values for a variety of Candida clinical isolates were linked with genetic mutations in the hot spot regions of FKS1 and FKS2 genes5,6. Echinocandin resistance mechanisms are not yet clearly elucidated for Aspergillus spp. as in case of Candida spp.7.

The aim of the present work was to assess the development of reduced echinocandin susceptibility by an A. fumigatus clinical isolate exposed repeatedly in vitro to AFG and unveil the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Results and discussion

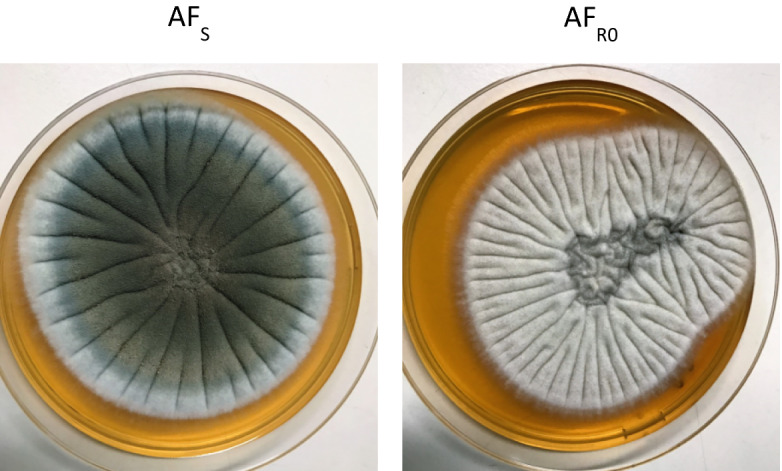

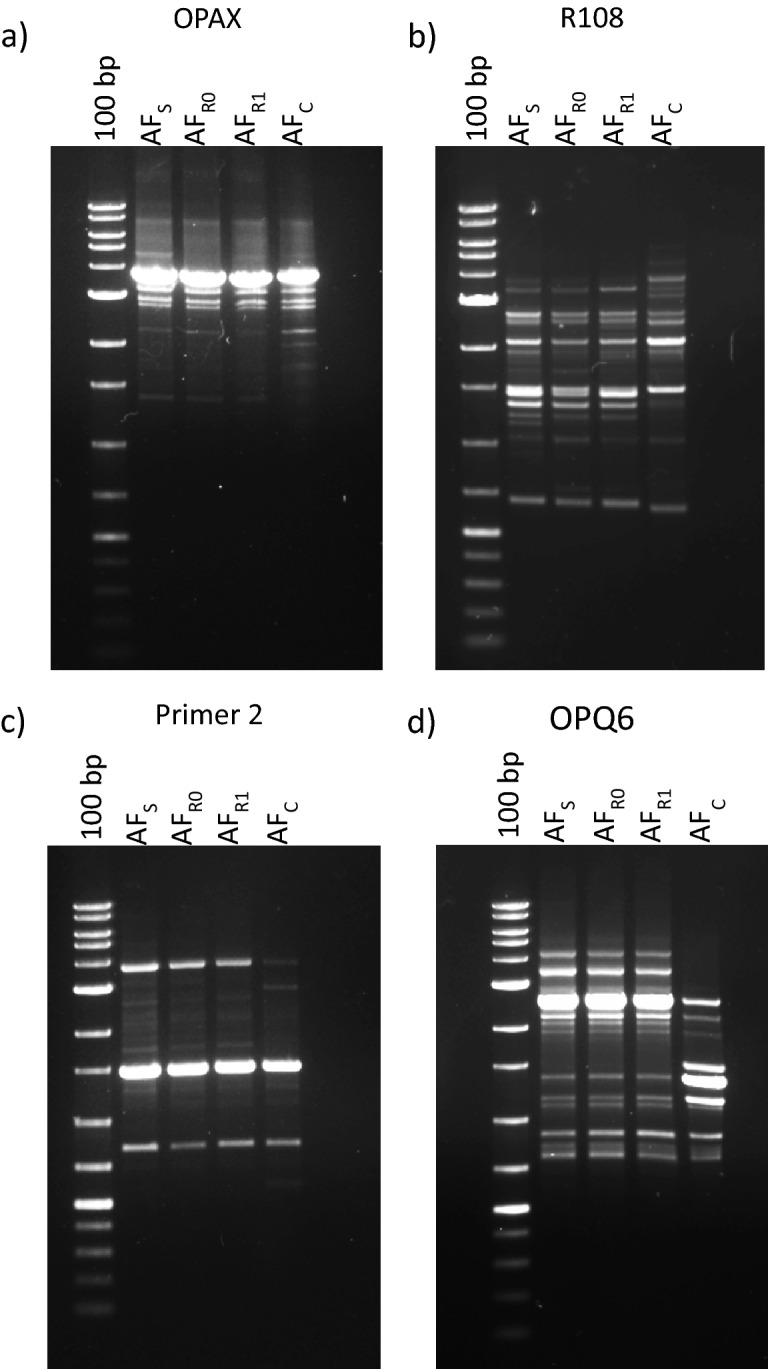

Dynamics of in vitro acquisition of resistance by A. fumigatus exposed to AFG is detailed in Table 1. After 30 days of exposure, resistance to AFG and cross-resistance to caspofungin (CAS) and micafungin (MFG) was developed. Exposure to AFG triggered macroscopic modification of morphology of A. fumigatus colonies, changing from the original green blue color to white (Fig. 1), becoming notably smaller. Microscopy showed absence of conidiation (data not shown). AFR0 and AFR1 showed the same macroscopic and microscopic phenotype. Similar changes have been reported in A. fumigatus exposed to antifungals during long periods8–10. RAPD analysis exhibits high discriminatory power for analysis of A. fumigatus strains when using this set of primers11. RAPD patterns obtained were 100% identical for the three strains (Fig. 2). A point mutation was found in AFR0 corresponding to replacement of glutamine by glutamate at position 671 of Fks1p (E671Q); similar mutation was found in AFR1. Since the resistant phenotype emerged abruptly, remaining stable following antifungal removal, it is highly plausible that this hot spot FKS1 mutation E671Q might be responsible for the reduced susceptibility of AFR0 and AFR1. A mutation in A. fumigatus FKS1 gene with potential to reduce echinocandin susceptibility is hereby described. Such mutation was never reported among Candida spp. An S678P amino acid change, equivalent to a mutation found in a resistant Candida isolate was described in a laboratory mutant of A. fumigatus and associated with resistance to CAS12,13. A mutation resulting in a F675S amino acid change was found in a chronic pulmonary aspergillosis isolate from a patient in whom micafungin treatment failed10. Point mutations in FKS1 genes are the main mechanism that is implicated in decreased echinocandin susceptibility, however, Arendrup and colleagues found no mutations in FKS1 gene in two clinical isolates of A. fumigatus with MIC > 32 µg/mL to CAS14. Instead, an increased in FKS1 gene expression was observed14. This mechanism may be implicated in tolerance to echinocandin therapy.

Table 1.

Echinocandin Minimal Effective Concentration (MEC) values anidulafungin (AFG), caspofungin (CAS) and micafungin (MFG) distribution during in vitro induction assay with AFG of an A. fumigatus clinical isolate.

| Induction day | MEC value (µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AFG | CAS | MFG | |

| 0 | ≤ 0.015 | ≤ 0.015 | ≤ 0.015 |

| 5 | ≤ 0.015 | 0.06 | ≤ 0.015 |

| 10 | ≤ 0.015 | 0.125 | 0.03 |

| 15 | ≤ 0.015 | 0.125 | 0.06 |

| 20 | ≤ 0.015 | 0.125 | 0.125 |

| 25 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.125 |

| 30 | > 8 | > 8 | > 8 |

Figure 1.

Photographs of YEPD agar plates showing A. fumigatus colony morphology following exposure to anidulafungin. AFS, initial susceptible strain. AFR0, resistant induced strain.

Figure 2.

Random amplification of polymorphic DNA patterns, using primers (a) OPAX and (b) R108, (c) Primer 2 and (d) OPQ6, of Aspergillus fumigatus strains (AFS, initial susceptible strain, AFR0, resistant induced strain, and AFR1, resistant strain after 30 days without antifungal) obtained during in vitro induction assay. AFC represents a distinct A. fumigatus clinical strain, with a different pattern. 100 bp DNA ladder.

The E671Q mutation replaces an amino acid with a negatively charged side chain (glutamate) by an amino acid with a polar but uncharged side chain (glutamine). This position is conserved among several fungi (Fig. 3a). PROVEAN software considers an amino acid alteration at this position deleterious, suggesting that this region might have a relevant functional and/or structural role15. According to the three-dimensional (3D) structure obtained, E671 establishes polar contacts with K668 and T677 amino acids. Substitution by a glutamine would disrupt two of the three contacts with T677, which could distort conformation of the protein (Fig. 3b), given the proximity to a transmembrane domain (amino acids 679–699 in S. cerevisiae). Therefore, E671 may be necessary to maintain protein’s three-dimensional structure, supporting the assumption that such substitution could impair its function. Ultimately, two approaches might be taken: FKS1 gene deletion in resistant strain to determine whether reversion to the susceptible phenotype occurs and site-directed mutagenesis in wild-type strain to observe whether resistant phenotype arises. Nevertheless, other mechanisms might also be involved in the development of echinocandin resistance, such as remodeling of cell wall components namely chitin levels, production of reactive oxygen species, alteration of the composition of plasma membrane lipids or expression levels of echinocandin target enzyme genes16,17.

Figure 3.

Sequence and structure analysis of the E671Q substitution in Fks1p. (a) Multiple protein sequence alignment of fungal Fks1 orthologues. A potential structural and/or functional role is suggested by the conservation of E671 even in distantly related species. (b) In the predicted structural model for this domain of the Fks1 protein (amino acids 400–900), the E671Q substitution would result in the loss of polar contacts with T677, disrupting the contacts between α-helices. AFS, the initial susceptible strain is shown in green, and AFR0, the resistant induced strain is shown in blue.

Our results suggest that modification of Fks1p in A. fumigatus might confer echinocandins resistance. Given the emerging importance of clinical resistance among pathogenic fungi, it would be advisable to monitor the potential evolution of this mechanism in Aspergillus isolates from patients under echinocandin therapy.

Material and methods

A suspension of 5 × 104 conidia/mL of A. fumigatus (clinical brochoalveolar lavage isolate) was prepared in YEPD broth (0,3% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 2% dextrose) supplemented with sub-Minimal Effective Concentration (sub-MEC) (0.06 µg/mL) of AFG (Pfizer, Inc.) and incubated overnight, at 35 °C, 180 rpm. One mL was daily transferred to fresh YEPD supplemented with AFG. In parallel, 1 mL aliquot of was frozen (− 80 °C) but also cultured on YEPD agar at 35 °C for 72 h, to confirm viability and purity of culture. AFG concentration was increased to double whenever fungal growth was prominent, reaching a final concentration of 8 µg/mL. In vitro induction was carried out up to 30 days. Every 5 days, MEC values of the 3 echinocandin were determined according to CLSI18. A MEC value ≥ 1 µg/mL was considered resistance19. In order to assess the stability of echinocandin MEC values increments, the induced strain was daily sub-cultured for an additional 30 days in the absence of antifungal and MEC values re-determined. The resistant pattern remained stable. At the end of the assay, three strains were characterized: the initial susceptible strain (AFS), the induced strain (AFR0) and the strain obtained following additional 30 days without antifungal exposure (AFR1).

Genotyping by random amplification of polymorphic DNA (RAPD) of strains AFS, AFR0, AFR1 using primers R108 (5′-GTATTGCCCT-3′), OPAX (5′-AGTGCACACC-3′), OPQ6 (5′-GAGCGCCTTG-3′) and Primer 2 (5′-GCTGGTGG-3′) was performed11.

Following PCR with primers 5-GCTGAAGGATGTCGTCTGGA and 5-CGGCAAGTGATGGTCTCGTG, hot spot regions (between 1,875 and 4,318 bp) of FKS1 gene (GenBank accession no. AFU79728) from AFS, AFR0 and AFR1 strains were amplified and sequenced were sequenced by Sanger method. The sequences were analyzed using BLAST Sequence Analysis Tool of NCBI.

The three-dimensional model for the Fks1 protein structure was obtained by modeling using the I-TASSER online server as previously described20,21. Structures were visualized in PYMOL v1.1r1.

Acknowledgements

A.P.S and J.B. are supported by the Portuguese Technology and Science Foundation (FCT), respectively Grants SFRH/BPD/102831/2014 and SFRH/BD/135883/2018. This work was supported by Astellas and Grupo de Infeção e Sepsis from Centro Hospitalar São João (Clinical Mycology Research grant). The authors would like to thank Isabel Santos for her excellent technical assistance.

Author contributions

S.C.O., A.P.S. and I.M.M. design the study and conceived the experiments; A.P.S., J.B., P.O., I.F.R. performed the experiments; S.C.O., A.P.S., R.M.S. and A.G.R. analyzed the results; S.C.O. and A.P.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Dockrell DH. Salvage therapy for invasive aspergillosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008;61(Suppl 1):i41–44. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh TJ, et al. Treatment of aspergillosis: clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008;46:327–360. doi: 10.1086/525258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seyedmousavi S, et al. In vitro interaction of voriconazole and anidulafungin against triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013;57:796–803. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00980-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowman JC, et al. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:3001–3012. doi: 10.1128/aac.46.9.3001-3012.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desnos-Ollivier M, et al. Mutations in the fks1 gene in Candida albicans, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei correlate with elevated caspofungin MICs uncovered in AM3 medium using the method of the European Committee on Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3092–3098. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00088-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa-de-Oliveira S, et al. FKS2 mutations associated with decreased echinocandin susceptibility of Candida glabrata following anidulafungin therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1312–1314. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00589-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiederhold NP. Antifungal resistance: current trends and future strategies to combat. Infect. Drug Resist. 2017;10:249–259. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S124918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varanasi NL, Baskaran I, Alangaden GJ, Chandrasekar PH, Manavathu EK. Novel effect of voriconazole on conidiation of Aspergillus species. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2004;23:72–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2003.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faria-Ramos I, et al. Development of cross-resistance by Aspergillus fumigatus to clinical azoles following exposure to prochloraz, an agricultural azole. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-14-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jimenez-Ortigosa C, Moore C, Denning DW, Perlin DS. Emergence of echinocandin resistance due to a point mutation in the fks1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus in a patient with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017 doi: 10.1128/AAC.01277-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menotti J, et al. Epidemiological study of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in a haematology unit by molecular typing of environmental and patient isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Hosp. Infect. 2005;60:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardiner RE, Souteropoulos P, Park S, Perlin DS. Characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus mutants with reduced susceptibility to caspofungin. Med. Mycol. 2005;43(Suppl 1):S299–305. doi: 10.1080/13693780400029023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocha EM, Garcia-Effron G, Park S, Perlin DS. A Ser678Pro substitution in Fks1p confers resistance to echinocandin drugs in Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4174–4176. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00917-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arendrup MC, et al. Establishing in vitro-in vivo correlations for Aspergillus fumigatus: the challenge of azoles versus echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:3504–3511. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00190-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walker LA, Lee KK, Munro CA, Gow NA. Caspofungin treatment of Aspergillus fumigatus results in ChsG-dependent upregulation of chitin synthesis and the formation of chitin-rich microcolonies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:5932–5941. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00862-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Satish S, et al. Stress-induced changes in the lipid microenvironment of beta-(1,3)-d-glucan synthase cause clinically important echinocandin resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. mBio. 2019 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00779-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute, C. A. L. S. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi. Approved Standard 2nd edn (2008).

- 19.Espinel-Ingroff A, et al. Wild-type MIC distributions and epidemiological cutoff values for amphotericin B and Aspergillus spp. for the CLSI broth microdilution method (M38–A2 document) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5150–5154. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00686-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J, et al. The I-TASSER Suite: protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:7–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Branco J, et al. Impact of ERG3 mutations and expression of ergosterol genes controlled by UPC2 and NDT80 in Candida parapsilosis azole resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017;23:575e571–575e578. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]