Highlights

-

•

Nine studies intervened on vaccination in racial/ethnic and sexual and gender minorities.

-

•

Education and reminders increased HPV vaccine series initiation and completion.

-

•

Lack of high-quality, adequately powered studies warrants further investigation.

Keywords: Papillomavirus vaccine, Cancer prevention, Minority population, Health disparities, Intervention studies, Systematic review

Abstract

Minority youth represent a unique population for public health interventions given the social, economic, and cultural barriers they often face in accessing health services. Interventions to increase uptake of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in minority youth have the potential to reduce disparities in HPV infection and HPV-related cancers. This systematic review assesses the effectiveness of interventions to increase HPV vaccine uptake, measured as vaccine series initiation and series completion, among adolescents and young adults, aged 9–26 years old, identifying as a racial and ethnic minority or sexual and gender minority (SGM) group in high-income countries.

Of the 3013 citations produced by a systematic search of three electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science) in November 2018, nine studies involving 9749 participants were selected for inclusion. All studies were conducted in the United States and were published from 2015 to 2018. Interventions utilized education, vaccine appointment reminders, and negotiated interviewing to increase vaccination. Participants were Black or African American (44.4%), Asian (33.3%), Hispanic or Latinx (22.2%), American Indian or Alaska Native (11.1%), and SGM (22.2%). Studies enrolled parent–child dyads (33.3%), parents alone (11.1%), and youth alone (55.6%). Vaccine series initiation ranged from 11.1% to 84% and series completion ranged from 5.6% to 74.2% post-intervention. Educational and appointment reminder interventions may improve HPV vaccine series initiation and completion in minority youth in the U.S. Given the lack of high quality, adequately powered studies, further research is warranted to identify effective strategies for improving HPV vaccine uptake for minority populations.

1. Introduction

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted disease. An estimated 80–90% of individuals will contract HPV at some point in their lives (HPV Fast Facts, 2018, Human Papillomarivus: HPV Fact Sheet, 2019). Despite introduction of multivalent vaccines in 2006 that protect against infection with the most common HPV types, HPV was associated with 43,300 new cases of cancer in the United States in 2015 including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, penile, and head and neck cancers (Meites et al., 2019, Van Dyne et al., 2018).

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends HPV vaccination as part of routine preventive health care for all adolescents aged 11 and 12 years old, ideally before sexual activity is initiated (Human Papillomarivus: HPV Fact Sheet, 2019). Vaccination can be initiated as early as age nine, with continued vaccination through age 21 for males and age 26 for females, men who have sex with men, transgender people, and immunocompromised persons not adequately vaccinated previously (Human Papillomarivus: HPV Fact Sheet, 2019). The HPV vaccine is administered in a series, with two or 3 doses required for immunization, depending on patient age at initiation and vaccine schedule (Human Papillomarivus: HPV Fact Sheet, 2019).

HPV vaccination rates remain sub-optimal. In 2017, 66% of adolescents aged 13–17 years started the vaccine series and 49% completed the series in the U.S., with disparities in vaccine uptake for some populations like racial and ethnic minority groups in the U.S. and other high-income countries (Van Dyne et al., 2018, Musselwhite et al., 2016, Jeudin et al., 2014). Some studies have found that Black, Hispanic, and Asian adolescents were more likely to initiate the HPV vaccine series than their white counterparts, however, were less likely to complete the series (Spencer et al., 2019, Jeudin et al., 2014, Cook et al., 2010, Widdice et al., 2011). Documented barriers to HPV vaccination of minority youth include knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among parents, geographic location, distance to vaccination centers, immigrant or foreign-born status, acculturation levels, socioeconomic status, insurance status, and high cost of the vaccine (Ojeaga et al., 2019, Kepka et al., 2010, Tsui et al., 2013, Perkins et al., 2013, Perkins et al., 2010, Davlin et al., 2015, Bastani et al., 2011, Schluterman et al., 2011, De and Budhwani, 2017). Sexual and gender minorities also experience inequity in vaccine uptake and face barriers such as lack of identity-affirming care, identity-specific dosing and vaccination timelines, and lack of representation in marketing and health campaigns (Apaydin et al., 2018).

Interventions to promote vaccine uptake for minority groups and equitable distribution of HPV vaccination have the potential to mitigate disparities in HPV infection and HPV-related cancers (Saadeh et al., 2020). While there is some evidence to suggest between-group vaccination disparities may be decreasing over time, additional interventions are warranted to increase overall vaccination across racial and ethnic groups (Burdette et al., 2017). A 2014 systematic review of educational interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake noted a lack of participant diversity and called for future studies of culturally-competent interventions (Fu et al., 2014). Similarly, Rodriguez et al. called for future studies assessing the effectiveness of interventions in reaching diverse populations and reducing missed opportunities for HPV vaccination (Rodriguez et al., 2019). This systematic review, therefore, summarizes and critically appraises evidence of intervention studies to increase uptake of HPV vaccination among minority adolescents and young adults in high-income countries.

2. Methods

A systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases, as well as the first 50 Google Scholar engine search results was conducted to query intervention studies to increase HPV vaccine uptake by minority populations. The database identification and search strategy were developed through literature review, in consultation with a Medical Librarian in October and November 2018 (Bramer et al., 2017). The search used database-specific controlled vocabulary and natural terms/keywords for the “topic (HPV vaccine)” AND “outcomes (vaccine uptake)” AND “population (minority participants)”. A detailed search strategy for the PubMed search is provided in Appendix A with the full search strategy available upon request from the authors. No date or language restrictions were applied. Grey literature citations (i.e. unpublished or non-peer-reviewed data sources including conference proceedings, abstracts, and dissertations) indexed by any of the databases searched were screened with all other peer-reviewed publications using the same inclusion and exclusion criteria to reduce the risk of publication or dissemination bias (Song et al., 2013, Higgins et al., 2019). No hand-searching was performed for high-yield journals or conferences.

The population of interest was minority populations living in high-income countries, as defined by the World Bank (The World Bank Country and Lending Groups, 2019). Minority populations are distinct racial or ethnic minority groups, or sexual and gender minority groups, with common interests or characteristics that distinguish them from the more numerous majority of the population of which they form a part or with whom they live in close proximity within a common political jurisdiction (Minorities, 2001). Minority groups are described in this review using the most descriptive language available to reviewers, as the population was described by the source authors when possible. For racial and ethnic minority groups, classifications from the U.S. Census Bureau were adopted to compare across studies: Black or African American; Hispanic or Latinx; Asian; Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander; and American Indian or Alaska Native (U.S. Census Bureau. About race, 2018). Sexual and gender minority populations include, but are not limited to, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, transgender, two-spirit, queer, and/or intersex, as defined by the National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. About SGMRO (2020). Minority groups are frequently more likely to experience health disparities that reduce access to and quality of healthcare and preventive services (National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. About SGMRO, 2020). The population age criteria for study inclusion were adolescents and young adults, from nine to 26 years old, in alignment with the CDC recommendations for HPV vaccination (Petrosky et al., 2015). Participants were youth, parents or guardians, or parent–child dyads. A liberal “all interventions” criteria for intervention types was established to capture a wide variety of approaches to increasing HPV vaccine uptake; this criteria included educational interventions, behavioral interventions, and promotional and communications interventions. The comparison was routine care or no intervention. The primary outcome was vaccine uptake, measured as vaccine series initiation, the proportion of the population with receipt of the first dose of HPV vaccine, and series completion or receipt of all recommended doses in the vaccine series. Secondary outcomes were: intention to receive HPV vaccine; vaccine acceptability; change in HPV/cervical cancer knowledge; and change in vaccine-related attitudes/beliefs. Eligible study designs included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort, and pre-post with a control arm. Studies were excluded if they did not present disaggregated vaccine uptake results that could be extracted for minority/majority groups.

Screening of citation titles and abstracts were performed in pairs, with discordant screening decisions resolved by a third reviewer (BEL, BOO, EJA, NK, MR). Then, full texts were obtained and screened using a Cochrane review eligibility form. Data extraction was performed by two authors independently (BEL, BOO, EJA, NK, MR) using a Cochrane Collaboration data extraction worksheet and then cross-checked for accuracy. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Data were extracted for pre-defined variables including the study dates, setting, size, and design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, population and participant characteristics, intervention, comparison, and outcomes. For dyads enrolled in studies, only the number of youth were extracted as they are the only participants for whom vaccine uptake was measured. Authors of eligible studies were contacted via email by the first author (BEL) for additional information as needed, such as when data were not disaggregated by minority group status or when conference abstracts did not contain sufficient information to make an informed screening decision. If we were unable to establish contact with study authors or did not receive the requested information within one month of the request and it was impossible to separate published data based on minority status, the study was excluded. If authors provided more complete data, the most complete data source was considered for inclusion.

Risk of bias was assessed for all included peer-reviewed studies, using Cochrane Collaboration tools for randomized controlled trials and non-randomized studies (Higgins et al., 2011, Sterne et al., 2016). Two review authors independently assessed the risk of bias for each study (BOO, NK, JE), compared assessments, and reached consensus on the final risk assessment for each bias domain. Heterogeneity of study design, populations, interventions, and outcomes precluded a meta-analysis. Narrative synthesis of the studies was conducted and is presented in text and tables. The protocol for this review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) prior to the start of the review process (CRD42018104490). All findings are reported according to PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al., 2009). As this study is a systematic review of published articles, no research ethics approval was sought.

3. Results

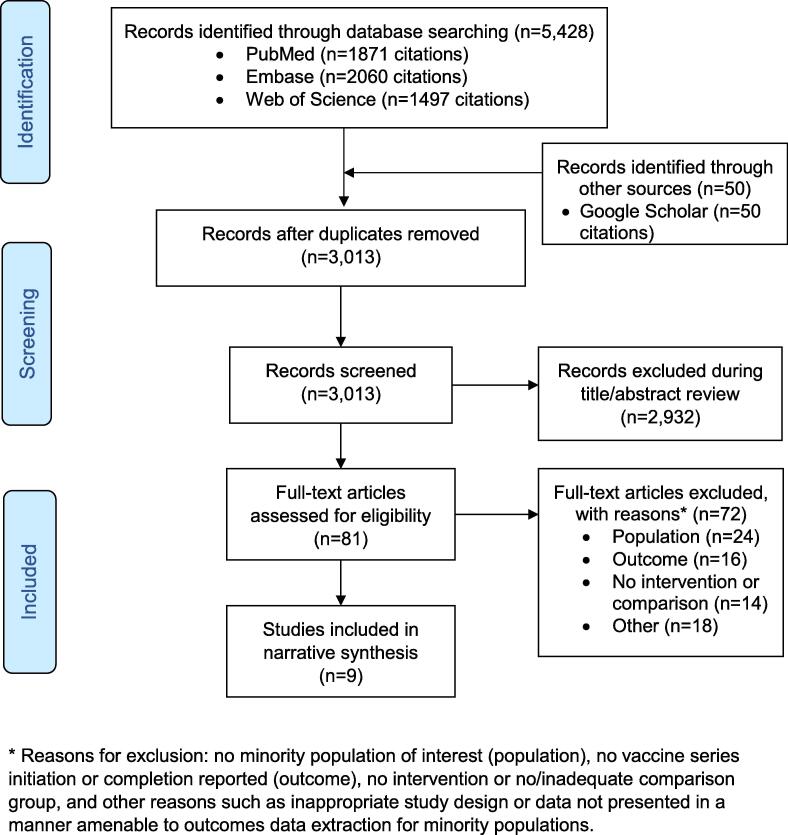

The systematic search conducted on November 12, 2018 yielded 3013 unique titles, from which 81 full texts were screened. Nine studies, eight peer-reviewed publications and one doctoral dissertation, involving 9749 participants were included (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016, Winer et al., 2016). For the doctoral dissertation, the full text was obtained through email contact with the author (Kim, 2017), after screening a related conference abstract returned in the systematic search (Kim et al., 2018). The study selection process is presented in Fig. 1. Full texts screened and deemed ineligible for inclusion are reported with reasons for exclusion in Appendix B. Included studies were published from 2015 to 2018 and all were conducted in the United States. The majority of studies employed a randomized study design (88.9%; n = 8/9) (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016, Winer et al., 2016). The target populations for HPV vaccination ranged in age from nine to 26 years. More than half of the interventions directly engaged adolescents/young adults (55.6%, n = 5/9) (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Kim, 2017, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016), while others used a parent–child dyad approach (33.3%, n = 3/9) (Joseph et al., 2016, Lee et al., 2018, Winer et al., 2016), or engaged parents of adolescents alone (11.1%, n = 11) (Parra-Medina et al., 2015). Most studies enrolled females only (77.8%, n = 7/9) (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Winer et al., 2016). Participant and study characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study selection process * Reasons for exclusion: no minority population of interest (population), no vaccine series initiation or completion reported (outcome), no intervention or no/inadequate comparison group, and other reasons such as inappropriate study design or data not presented in a manner amenable to outcomes data extraction for minority populations.

Table 1.

Study and participant characteristics.

| Characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant characteristics | Minority group* | ||

| Black or African American | 1716 | 17.6 | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 6556 | 67.2 | |

| Asian | 1154 | 11.8 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 97 | 1.0 | |

| Sexual and Gender Minority | 173 | 1.8 | |

| Not specified/“Other” minority races | 53 | 0.5 | |

| Study characteristics | Minority group | ||

| Black or African American | 4 | 44.4 | |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 2 | 22.2 | |

| Asian | 3 | 33.3 | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Sexual and Gender Minority | 2 | 22.2 | |

| Not specified/”Other” minority races | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Genders enrolled | |||

| Female only | 7 | 77.8 | |

| Male only | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Female and male | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Intervention participants | |||

| Adolescents/young adults only | 5 | 55.6 | |

| Parents of Minors | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Parents and Minors | 3 | 33.3 | |

| Vaccination status at enrollment | |||

| Unvaccinated | 6 | 66.7 | |

| Received first dose of series | 2 | 22.2 | |

| Any number of doses, incomplete series | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Publication year | |||

| 2015-2016 | 6 | 66.7 | |

| 2017-2018 | 3 | 33.3 | |

| Study design | |||

| RCT | 8 | 88.9 | |

| Non-randomized | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Sample size | |||

| <100 | 2 | 22.2 | |

| 100-500 | 6 | 66.7 | |

| 500-1000 | 0 | 0 | |

| >1000 | 1 | 11.1 | |

*Minority groups are defined here using race and ethnicity classifications of the U.S. Census Bureau [22]. Sexual and gender minority populations include, but are not limited to, individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, asexual, transgender, two-spirit, queer, and/or intersex, as defined by the National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office [23].

3.1. Minority groups

The majority of studies included in this review reported on vaccine uptake among racial and ethnic minority groups (88.9%; n = 8/9) (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Richman et al., 2016, Winer et al., 2016). Participants were most likely to be Hispanic or Latinx (67.2%; n = 6556) followed by Black or African American (17.6%; n = 1716), though a greater number of the studies enrolled Black or African American populations (44.4%; n = 4/9) (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Richman et al., 2016) and Asian populations (33.3%; n = 3/9) (Chao et al., 2015, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018). Some studies enrolled participants from multiple minority groups (33.3%; n = 3/9) (Chao et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Richman et al., 2016), while others focused on creating interventions that were tailored to a specific minority group (66.6%; n = 6/9) like Korean American college students (Kim 2017), African American girls (DiClemente et al., 2015), or Hopi mother-daughter dyads (Winer et al., 2016). Two studies (22.2%) included sexual and gender minority (SGM) populations (Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016); one exclusively recruited young gay and bisexual men (Reiter et al., 2018) while the other enrolled homosexual and bisexual male and female students (Richman et al., 2016). Table 2 provides additional population information for each study such as nativity, language, and age of participants.

Table 2.

Description of minority populations, interventions, and study outcomes.

| Study ID | Study Design | Minority Sample Size | Setting | Population | Intervention | Outcomes and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chao et al., 2015 [29] | Randomized | 8436 | Southern California (USA) | Black (n = 1231), Hispanic (n = 6184), and Asian (n = 1048) girls and women, 9 to 26 years old (16.7 mean), in a large managed care organization with one dose of HPV vaccine | Reminder: Vaccine reminder letter, in English and Spanish, mailed every three months | Series completion within 12 months

|

| DiClemente et al., 2015 [30] | Randomized | 216 | Atlanta, Georgia (USA) | African American adolescent girls, 13 to 18 years old (16.5 mean), with no previous HPV vaccine, seeking family planning and STI services in health clinics | Education + Reminder: Multi-component, computer-delivered intervention including a culturally-appropriate video and promotional keychain as appointment reminder | Series initiation within seven months

|

| Joseph et al., 2016 [31] | Randomized | 200 | Not Reported (USA) | Haitian American (n = 100) and African American (n = 100) mothers with daughters aged 11 to 15 years old, with no previous HPV vaccine, English and Haitian-Creole speaking, U.S. born or immigrant status, attending primary care visits in a large, urban hospital | Brief Negotiated Interviewing (BNI) with mothers to address beliefs, attitudes, and readiness for behavior change, and to identify next steps for vaccination | Series initiation within one month

|

| Kim et al., 2018 [32] | Randomized | 87 | 6 states in the Northeast (USA) | Korean American female college students, aged 18 to 26 years old (mean = 21.7), having received no previous doses of HPV vaccine, recruited through Korean community sources | Education: A culturally-appropriate online educational story-telling intervention | Series initiation OR scheduled appointment to receive vaccine within two months

|

| Lee et al., 2018 [33] | Randomized | 19 | Massachusetts (USA) | Khmer American mother-daughter dyads with daughters, aged 14 to 17 years old (15.3 mean) with no previous HPV vaccine, English and Khmer speaking and/or reading, U.S. born or immigrant status, recruited through Khmer community sources | Education: Theory-guided, culturally grounded storytelling narrative video intervention, in English and Khmer delivered to mothers and daughters | Series initiation within one month

|

| Parra-Medina et al., 2015 [34] | Non-randomized | 372 | Texas (USA) | Hispanic mothers-daughter dyads, with girls aged 11 to 17 years old with no previous HPV vaccine history, living along the Texas-Mexico border, recruited by community health workers | Education + Other Services: Mother/daughter educational intervention and referral, navigation, and follow-up phone call services delivered by community health workers (CHWs) and undergraduate peer educators, in English and Spanish | Series initiation within six months

|

| Reiter et al., 2018 [35] | Randomized | 150 | 31 states and the District of Columbia (USA) | Males, aged 18 to 25 years old, self-identifying as gay (n = 124) or bisexual (n = 26), having never received any dose of HPV vaccine, recruited through Facebook | Education + Reminder: Population-targeted, individually-tailored content about HPV and HPV vaccine delivered online, plus monthly email or text HPV vaccination reminders | Series initiation within seven months

|

| Richman et al., 2016 [36] | Randomized | 145 | Southern USA | Black (n = 69) or “other” race (n = 53) and homosexual/bisexual (n = 23) English-speaking male and female students, 18 to 26 years old, attending a large university who were voluntarily initiating the first HPV vaccine dose from the campus health center | Education + Reminder: Series of 7 electronic messages with health education messages about HPV and HPV vaccine and appointment reminder messages | Series completion within seven months

|

| Winer et al., 2016 [37] | Randomized | 97 | Hopi Reservation (North America) | Hopi (American Indian) mothers-daughter dyads, with girls aged 9 to 12 years old, any number of previous HPV vaccine doses (unvaccinated and incompletely vaccinated), recruited through Hopi community sources | Education: Mother-daughter dinner events featuring educational presentations on HPV | Series initiation within 11 months

|

*p-value not reported.

**numbers and percentages not reported by authors due to a cell size < 5.

3.2. Intervention strategies

Educational interventions were used most frequently among included studies to effect change in vaccination behavior (77.8%; n = 7/9) (DiClemente et al., 2015, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016, Winer et al., 2016). Other intervention strategies, assessed alone or in combination with educational interventions, included vaccination appointment invitations and reminders (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016), referrals and patient navigation services (Parra-Medina et al., 2015), and brief negotiated interviews to identify and overcome barriers to vaccination (Joseph et al., 2016). Educational interventions were delivered virtually through computers and phones (DiClemente et al., 2015, Kim, 2017, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016), at community events (Winer et al., 2016), and through multimedia (Lee et al., 2018). Two used cultural storytelling (Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018). Education only interventions (33.3%, n = 3) achieved a 0 to 22.7% increase in series initiation (Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Winer et al., 2016) and a 4.4% increase in series completion for the only study that measured it (Winer et al., 2016). Appointment reminders were delivered as letters (Chao et al., 2015), phone calls (Parra-Medina et al., 2015), electronically as emails and text messages (Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016), and using promotional keychains (DiClemente et al., 2015). Only one study evaluated a reminder intervention alone and found a statistically significant increase of 9.9–14% in series completion for Asian, Hispanic, and Black participants (p < 0.01) (Chao et al., 2015). Studies that combined education with reminders demonstrated an increase of 0–19% in vaccine initiation and an increase of 3.7 to 37.4% in series completion when compared to controls (DiClemente et al., 2015, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016). The one study that used brief negotiated interviewing with mothers observed nonsignificant increases in series initiation and series completion (Joseph et al., 2016).

3.3. Outcomes and effectiveness of interventions

Five included studies (55.6%) measured both primary outcomes, HPV vaccine series initiation and completion (DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Winer et al., 2016), two studies (22.2%) measured series initiation only (Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018), and two (22.2%) measured series completion only (Chao et al., 2015, Richman et al., 2016). Series initiation ranged from 11.1% to 84% following intervention. Five of the seven studies (71.4%) reporting on series initiation, observed no change in vaccine uptake (DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Parra-Medina et al., 2015), however, two of those studies did observe increases in series completion (DiClemente et al., 2015, Parra-Medina et al., 2015). The two interventions that were associated with significant improvements in series initiation were an educational intervention for Hopi mother-daughter dyads delivered during community dinner events (50% initiation in the intervention group vs. 27.3% in the comparison group, relative risk [RR] = 1.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8–4.4) (Winer et al., 2016) and an educational intervention with tailored content for 18–25 year old gay and bisexual males delivered alongside monthly vaccination reminders (44.7% vs. 25.7%, p < 0.001) (Reiter et al. 2018).

Seven studies measured series completion which ranged from 5.6% to 74.2% in intervention groups at follow-up intervals of 6 to 12 months (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016, Winer et al., 2016). Richman et al. found that a series of seven electronic educational messages about HPV and vaccination was effective for improving series completion among male and female university students who voluntarily initiated the first dose (2016). The intervention was associated with increases in completion for Black (74.2% vs. 36.8%) and homosexual/bisexual students (38.9% vs. 20%) (Richman et al., 2016). Another study found that vaccination reminder letters alone, sent in English and Spanish every three months, improved series completion among Black (51.9% vs. 37.6%), Hispanic (56.9% vs. 45.9%), and Asian participants (63.2% vs. 53.3%) who had previously received one dose of the HPV series (p < 0.01) (Chao et al., 2015). Among studies where participants had previously received no doses of HPV vaccine, the most favorable improvements in series completion came from a non-randomized, multi-component intervention for Hispanic mothers with daughters aged 11–17 years old (72.2% vs. 42.5%, p < 0.001) (Parra-Medina et al., 2015). The bilingual intervention consisted of education, referral and patient navigation services, and follow-up phone calls, delivered by community health workers and peer educators (Parra-Medina et al., 2015).

Secondary outcomes were reported for five studies (55.6%) and included HPV and cervical cancer knowledge (DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Richman et al., 2016), HPV and vaccine-related beliefs such as perceived susceptibility (DiClemente et al., 2015, Kim, 2017), vaccine acceptability (DiClemente et al., 2015, Kim, 2017), and intent to receive HPV vaccination (Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018). Joseph et al. found that while brief negotiated interviewing with Haitian American and African American mothers did not improve vaccine series initiation or completion, it did improve HPV knowledge from a mean score of 6 (SD = 4.0) preintervention to 10 (SD = 2.0) postintervention (p < 0.0001) (2016). Similarly, DiClemente et al. observed that their intervention had no significant effect on series initiation or series completion but that perceived susceptibility to HPV (p = 0.04) and cervical cancer (p = 0.01) were significantly different between the intervention and control participants (2015). Even still, perceived susceptibility remained low; only 22.2% and 23.1% of intervention participants perceived themselves to be at risk of getting HPV or cervical cancer (DiClemente et al., 2015). In the same study, 63% of African American girls, aged 13 to 18 years old reported that they would be “likely to get the HPV vaccine if a healthcare provider offered it to them in the next 12 months”; vaccine acceptability was not reported by intervention/control condition (DiClemente et al., 2015). Two culturally-grounded storytelling intervention studies measured participants’ intent to receive HPV vaccine: one reported an increase in intention for the intervention group compared to the control group (44.4% vs. 11.1%) for Khmer American mother-daughter dyads (Lee et al., 2018), while the other reported no between-group difference for Korean American college students (Kim, 2017).

3.4. Quality assessment

Some risk of bias was found for all studies, as illustrated in Table 3. One grey literature source, a dissertation, was not assessed for quality (Kim, 2017). Selection bias, resulting from the random sequence generation, was unsatisfactory as reported by four of the seven randomized studies assessed (57.1%). Four studies (57.1%) were also determined to be at serious risk of attrition bias, resulting from incomplete outcome data. Selective reporting was not detected in any of the included studies. The only non-randomized study in our review was found to be at serious risk of bias due to confounding and bias in measurement of outcomes, and low risk of bias for all other domains.

Table 3.

Risk of bias summary for included studies.

|

Randomized studies were assessed as low, moderate, or serious risk of bias for each domain; non-randomized studies were assessed as low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias for each domain.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to assess HPV vaccine promotion interventions among minority adolescents and young adults. Given the importance of HPV vaccination and the significant impact uptake of HPV vaccine can have on cancer rates, it is concerning that only nine studies were identified.

4.1. Vaccine uptake by minority groups

With a wide range of minority groups and intervention types, our ability to compare across the studies was limited. Conflicting results exist across population groups. For example, Chao et al. found that reminder letters were effective for achieving a 51.9% series completion rate for Black girls and women, aged 9 to 26 years old, while the DiClemente et al. study of a multi-component educational intervention with reminder keychains yielded a much lower series completion rate of 5.6% for 13 to 18 year old African American adolescent girls (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015). One important difference between the studies was their inclusion criteria: one enrolled participants who had already received one dose of HPV vaccine while the other exclusively enrolled vaccine-naïve participants. From a health behavior perspective, initiating and then completing a vaccine series may be a different health behavior than simply completing an already initiated series, with different barriers and facilitators to series completion, such as differential vaccine-related attitudes and beliefs.

Some populations exhibited higher overall vaccination behavior, while others showed lower overall uptake but more positive response to intervention. In the Chao et al. study, Asian girls and women reached 63.2% series completion in the intervention group, which was higher than the completion reached for Hispanic and Black women and girls, but represented the smallest improvement in uptake since Asian participants had higher completion than other minority groups amongst control participants (2015). Hispanic girls living along the Texas-Mexico border did not increase series initiation in the Parra-Medina et al. study but exhibited an already high series initiation rate of 84% without intervention and did increase series completion sizably from 42.5% to 72.2% (p < 0.001) (Parra-Medina et al., 2015).

Also making it difficult to determine any intervention’s effectiveness, is the wide variability that was observed in vaccine uptake between minority groups participating in the same interventions. An electronic health messaging and appointment reminder intervention resulted in 74.2% series completion for Black participants, but only 38.9% series completion for homosexual and bisexual participants (Richman et al., 2016). This finding supports the need for focused interventions that address population-specific barriers to vaccination; broad “catch-all” type interventions that are not specifically designed to meet the needs of any one participant group may not be as effective for some groups and may exacerbate vaccination inequities.

This review highlights the heterogeneity that exists within minority groups and the inadequacy of monolithic racial categories that are frequently used. Some of the included studies used umbrella terms like Asian to identify their participants, while others focused on more specific ethnic and cultural minority groups. Indeed, the studies by Lee et al. and Kim et al. found low rates of vaccine initiation for Khmer American mother-daughter dyads (22.2% initiation) (Lee et al., 2018) and Korean American college students (15.6% initiation) (Kim, 2017), suggesting these groups may have greater vaccine hesitancy or other barriers to vaccination than Asian participants from the Chao et al. study (63% completion) (2015). In a study of Haitian American and African American mothers, Joseph et al. faced recruitment challenges; 60% of eligible mothers declined to participate (2016). Joseph’s earlier research showed that Haitian mothers were least accepting of HPV vaccination for their daughters among Black women, citing concerns about vaccination at an early age (Joseph et al., 2012). Only one study in this review enrolled American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN) participants, who were Hopi (Winer et al., 2016). The findings from that study are in no way generalizable to other AI/AN populations. They estimated that 97% and 80% of girls aged 13–17 years old living on the Hopi reservation had initiated and completed the HPV vaccine series in 2013, respectively, rates much higher than the 73% and 43% initiation and completion rates that were reported for all AI/AN girls of the same age, in the same year (Winer et al., 2016, Elam-Evans et al., 2014).

4.2. Mother-daughter dyadic vs. Adolescent only or parent only approaches

Parental hesitancy has proved challenging for vaccinations in general and may be especially important to address for HPV vaccination. One reason for parental hesitancy of HPV vaccination is a belief that vaccinating against a sexually transmitted infection (STI) may promote earlier sexual debut of adolescents or increased promiscuity (Barnes et al., 2018, Waller et al., 2006). Most of the studies in this review approached youth as autonomous individuals, with considerable power over their own vaccination decisions. In some states, adolescents can access preventive services for STIs, including HPV vaccination, without parental consent. Other studies saw parents, particularly mothers, as gatekeepers and the ultimate decision-makers about their child’s vaccination. Due to the limited number of studies and heterogeneity of populations and interventions, we were not able to determine which approach yielded the greatest improvement in vaccine uptake. It is likely that parental involvement in adolescent HPV vaccination is a facilitator to improved vaccine uptake for some populations or dyads and a barrier for others, especially where there are strong cultural taboos around sexual initiation or communicating with children about sex or when an adolescent has not disclosed their sexual orientation or behavior to a parent (Nadarzynski et al., 2018, Wheldon et al., 2018). One consideration that might be used in parent–child dyadic approaches is “time alone” between the adolescent and the healthcare provider, since it has been shown to increase the likelihood that adolescents will discuss sensitive health matters, is considered an ethical best practice for serving adolescents, and is generally accepted by parents (Ford et al., 2004, McKee et al., 2011).

4.3. Intervention strategies

In this review, some evidence exists to support educational interventions and vaccination reminders to improve vaccine uptake for minority populations. Both strategies have been described by previous reviews as effective for increasing HPV vaccination in large and non-diverse populations (Smulian et al., 2016, Walling et al., 2016). However, one systematic review of educational interventions to increase HPV vaccine acceptance reported no change in vaccine uptake among populations with high education and health literacy (Fu et al., 2014). The authors attributed the lack of effectiveness to studies that were inadequately powered to detect meaningful change in vaccine uptake. This review similarly found that small studies, often intervention pilot studies, were inadequately powered to detect between group differences in vaccination. The majority of included studies had <220 participants (77.8%, n = 7/9) (DiClemente et al., 2015, Joseph et al., 2016, Kim, 2017, Lee et al., 2018, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016, Winer et al., 2016). The two largest studies in our review, a randomized study with 8436 minority participants, and a non-randomized study with 372 participants both reported significant improvement in series completion, achieving vaccine coverage of 51.9–72.2% in Black, Asian, and Hispanic participants (Chao et al., 2015, Parra-Medina et al., 2015). Many of the small pilot intervention studies reported that interventions were feasible and well-received by participants, that adequate numbers of hard-to-reach populations were recruited, and authors thought that larger well-designed studies of the same intervention may in fact yield significant changes in uptake. Several studies discussed how increased length of follow-up may allow them to observe greater change in vaccination rates, particularly for series completion. In addition to small samples, none of the included studies was evaluated as having high methodological quality.

A review on patient reminder and recall systems to improve immunization rates concluded that reminders were associated with an increase of 0.6–18% for adolescent immunization (Jacobson Vann et al., 2018). In this review, specific to the HPV vaccination series in minority adolescents, studies with a reminder component were associated with an increase of 0–19% in vaccine initiation and an increase of 3.7–37.4% in series completion (Chao et al., 2015, DiClemente et al., 2015, Parra-Medina et al., 2015, Reiter et al., 2018, Richman et al., 2016). Only one study evaluated a reminder system alone (Chao et al., 2015), while the others combined reminders with educational interventions, making it difficult to discern how influential the reminder component was in effecting behavior change. In one of the included studies, that used electronic messages as HPV education and vaccination reminders, no significant difference in HPV knowledge was detected between the intervention and control group, suggesting that the reminder component was responsible for the increase in vaccine series completion (Richman et al., 2016). Previous literature has shown that the primary determinant of HPV vaccination is a healthcare provider’s recommendation to vaccinate (Darden and Jacobson, 2014). This may be especially true for certain population groups. Interventions that aimed to increase contact between patients and providers, like Reiter et al. and Parra-Medina et al., may have been more effective than those aimed at providing educational information or addressing vaccine-related attitudes, without any regard for the actual medical appointment or provision of HPV vaccine. Another solution not explored in any of the studies included in this review, is community-based HPV vaccination. A few of the studies in this review attempted to address environmental barriers to accessing HPV vaccination by ensuring that the vaccine was available free of charge and by using patient navigation services. While the educational interventions may have been delivered in a community-based setting, the participants were still expected to go to a health facility for the vaccine, whereas community-based vaccination may have further reduced access issues and increased vaccination rates. Walling et al. described community-based HPV vaccine initiatives, such as school-based programs, as particularly effective at reaching large, diverse populations, regardless of health insurance status (2016).

5. Limitations

This review has several limitations. As already stated, the insufficiency of available literature on interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake in minority populations, the heterogeneity of participant and study characteristics, and varying quality of included studies limits our ability to conclude about the effectiveness of any type of intervention for minority populations. Additionally, we were challenged by data that was not disaggregated by minority status and that did not allow us to account for intersecting identities. Some intervention studies reported the overall intervention effect for intervention and control groups, described the minority/majority composition of their sample, and may have even modelled the effect of race or some minority status on vaccine uptake, but did not present the data in a way that we could extract uptake for each minority group. Among included studies that enrolled participants from multiple minority groups, such as Richman et al. who enrolled Black, “other” race, and homosexual and bisexual participants, we were unable to identify participants who may belong to multiple identity groups. If a participant was Black and homosexual, they were counted twice, separately for each minority group. In reality, intersecting identities will present unique contexts for HPV vaccination that are not a summative or multiplicative combination of the experiences of each identity.

While our search thoughtfully attempted to employ minority population terms that were relevant across countries and cultures, such as controlled vocabulary terms like “minority health” or “ethnic groups,” we recognize that as a U.S.-based research team we brainstormed more detailed terminology for American minority groups, such as “African American” or “Asian American” keywords. Limited knowledge of terms used to describe minority populations in non-U.S. settings, such as use of the word “aboriginal” to describe minority groups in Australia, may have biased the search results to produce more U.S.-based studies. A number of studies set outside of the U.S. in other high-income countries were returned in the search results, however, were excluded during the study selection process based on the review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. The fact that so few studies were ultimately selected for inclusion in this review and given that all studies included were set in the U.S., further research is warranted on interventions to increase HPV vaccination in minority populations.

6. Conclusions

In this review, we found limited evidence to suggest educational and reminder interventions may be effective for improving HPV vaccine series initiation and completion in minority populations. Further investigation into HPV vaccination promotion strategies for different minority groups is warranted, given the potential of HPV vaccination to reduce racial and ethnic-based and sexual and gender-based inequities in cancer-related outcomes and the lack of evidence, varying study quality, and inadequately powered studies identified in this review. This review underscores the need for better tailoring of interventions to specific minority populations in order to maximize effect and use of healthcare resources.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Breanne E. Lott: Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Project administration, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Babasola O. Okusanya: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Elizabeth J. Anderson: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft. Nidal A. Kram: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Melina Rodriguez: Methodology, Investigation. Cynthia A. Thomson: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Cecilia Rosales: Conceptualization, Supervision. John E. Ehiri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This review was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant award number 1R25CA217725 to support implementation of the Student Transformative Experiences to Progress Under-Represented Professional (STEP-UP). The funding agencies played no role in the study conception, design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report (Thomson C, PI). The assistance provided by D. Jean McClelland, liaison Medical Librarian for the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, University of Arizona, in the development of the search strategy is acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101163.

Appendix A Complete search strategy for one database (PubMed)

| Database | PubMed |

|---|---|

| Provider/Platform | United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) at National Institutes of Health (NIH) |

| Date of search | 12 November 2018 |

| Search results | 1871 citations |

| Search terms | |

| Subject terms (15,515 results) | Index terms: “Papillomavirus Vaccines”[Mesh] OR “Papillomavirus Infections/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “Uterine Cervical Neoplasms/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR |

| Key terms: “HPV vaccine” OR “Human papillomavirus vaccine” OR “HPV vaccination” OR “Human papillomavirus vaccination” OR “HPV vaccines” OR “Human papillomavirus vaccines” OR “HPV vaccinations” OR “Human papillomavirus vaccinations” OR “Papillomavirus vaccines” OR “Papillomavirus vaccine” OR “Papillomavirus recombinant vaccine” OR “Quadrivalent human papillomavirus” OR “Bivalent human papillomavirus” | |

| AND | |

| Outcome terms (888,789 results) | Index terms: “Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice”[Mesh] OR “Patient Acceptance of Health Care”[Mesh] OR “Patient Compliance”[Mesh] OR “Decision-Making”[Mesh] OR “Intention”[Mesh] OR |

| Key terms: Uptake OR “vaccination coverage” OR intent OR “intent to vaccinate” OR “series initiation” OR “series completion” OR “vaccination initiation” OR “vaccination completion” OR “vaccine initiation” OR “vaccine completion” OR “vaccine acceptability” OR “vaccine use” OR “vaccination refusal” OR “vaccine refusal” OR “vaccine attitudes” OR “vaccine hesitancy” OR “vaccination hesitancy” OR “vaccination delay” OR “vaccine delay” OR “vaccine compliance” | |

| AND | |

| Population terms (684,221 results) | Index terms: “Minority Groups”[Mesh] OR “Sexual and Gender Minorities”[Mesh] OR “Homosexuality”[Mesh] OR “Transgender Persons”[Mesh] OR “Minority Health”[Mesh] OR “Vulnerable Populations”[Mesh] OR “Emigrants and Immigrants”[Mesh] OR “Ethnic Groups”[Mesh] OR “African Americans”[Mesh] OR “Hispanic Americans”[Mesh] OR “Asian Americans”[Mesh] OR “Male”[Mesh] OR |

| Key terms: minorities OR minority OR ethnicity OR race OR “racial minority” OR “racial/ethnic minority” OR “racial and ethnic minority” OR transgender OR homosexuality OR homosexual OR bisexuality OR bisexual OR gay OR “men who have sex with men” OR lesbian OR LGBT OR LGBTQ OR LGBTQIA OR “minority groups” OR “minority health” OR “sexual and gender minorities” OR “sexual and gender minority” OR SGM OR “sexual minority” OR “sexual minorities” OR “gender minority” OR “gender minorities” OR “vulnerable populations” OR emigrant OR immigrant OR “Ethnic Groups” OR “African American” OR “African Americans” OR “Native American” OR “Native Americans” OR “American Indian” OR “American Indians” OR “Asian American” OR “Asian Americans” OR “Hispanic American” OR “Hispanic Americans” OR Latino OR Latina OR Hispanic OR Black OR indigenous |

Appendix B Studies excluded during full-text review and reason for exclusion

| Study ID | Reason for Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Alexander_2012 | Outcome |

| Aragones_2015 | Other |

| Audrey_2018 | Other |

| Berenson 2016 | No comparison |

| Berenson 2018 | Other |

| Bonafide_2015 | Outcome |

| Casey_2013 | Target population did not apply |

| Caskey_2017 | Results published was not in a usable format and authors did not respond to request |

| Cates_2017 | No intervention |

| Cates_2018 | Outcome |

| Chapman_2010 | Outcome |

| Chung_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Conroy_2009 | No intervention |

| Dempsey_2018 | Target population did not apply |

| Esposito_2018 | Target population did not apply |

| Farmar_2016 | No comparison |

| Fernandez_2017 | Abstract published. Authors did not respond to request |

| Garland_2011 | No intervention |

| Goleman_2018 | Outcome |

| Grandahl_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Groom_2017 | Target population did not apply |

| Henrikson_2017 | Target population did not apply |

| Hull_2016 | Abstract published. Authors did not respond to request |

| Hull_2010 | Outcome |

| Iqbal_2016 | Target population did not apply |

| Jacobs-Wingo_2017 | Other |

| Kalapurayil_2017 | Target population did not apply |

| Keeshin_2017 | Results published was not in a usable format and authors did not respond to request |

| Kempe_2012 | Target population did not apply |

| Kreuter_2012 | Outcome |

| Lee_2016 | No comparison |

| Liang_2017 | Outcome |

| Ma_2018 | Results published was not in a usable format and authors did not respond to request |

| McRee_2013 | No intervention |

| McRee_2018 | Other |

| McRee_2018 | Outcome |

| McSorley_2016 | No intervention |

| McSorley_2016 | Other |

| Merriel_2018 | Other |

| Meyer_2018 | Target population did not apply |

| Middleman_2016 | No comparison |

| Morales-Campo_2017 | Same study as another included study (Parra-Medina) |

| Morris_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Mortenson_2010 | Outcome |

| Navarrete_2014 | No intervention |

| Nguyen_2012 | Outcome |

| Paskett_2016 | Target population did not apply |

| Patel_2014 | Target population did not apply |

| Podolsky_2009 | No intervention |

| Rand_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Rand_2017 | Outcome |

| Rand_2018 | Target population did not apply |

| Rockliffe_2018 | Outcome |

| Rodriguez_2018 | Outcome |

| Rodriguez_2018 | No intervention |

| Roston_2012 | Outcome |

| Sanderson_2017 | Other |

| Spleen_2011 | Target population did not apply |

| Staras_2014 | Other |

| Staras_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Suh_2012 | Target population did not apply |

| Szilagyi_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Thomas_2018 | Outcome |

| Tiro_2015 | Results published was not in a usable format and authors did not respond to request |

| Tisi_2013 | No intervention |

| Underwood_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Vanderpool_2015 | Other |

| Varman_2018 | Target population did not apply |

| Wainwright_2015 | Target population did not apply |

| Warren_2018 | No comparison |

| Zimet_2018 | Results published was not in a usable format and authors did not respond to request |

| Zimmerman_2017 | Target population did not apply |

Appendix C. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Apaydin K.Z., Fontenot H.B., Shtasel D., Dale S.K., Borba C.P., Lathan C.S. Facilitators of and barriers to HPV vaccination among sexual and gender minority patients at a Boston community health center. Vaccine. 2018;36(26):3868–3875. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes K.L., VanWormer J.J., Stokley S., Vickers E.R., McLean H.Q., Belongia E.A. Determinants of human papillomavirus vaccine attitudes: an interview of Wisconsin parents. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):746. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5635-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastani R., Glenn B.A., Tsui J., Chang L.C., Marchand E.J., Taylor V.M. Understanding suboptimal human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among ethnic minority girls. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(7):1463–1472. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramer W.M., Rethlefsen M.L., Kleijnen J., Franco O.H. Optimal database combinations for literature searches in systematic reviews: a prospective exploratory study. Sytemat. Rev. 2017;6:245. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0644-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdette AM, Webb NS, Hill TD, & Jokinen-Gordon H. Race-specific trends in HPV vaccinations and provider recommendations: persistent disparities or social progress? Public Health. 2017;142: 167-176. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.fsu.edu/10.1016/j.puhe.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chao C., Preciado M., Slezak J., Xu L. A randomized intervention of reminder letter for human papillomavirus vaccine series completion. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015;56(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R.L., Zhang J., Mullins J., Kauf T., Brumback B., Steingraber H. Factors associated with initiation and completion of human papillomavirus vaccine series among young women enrolled in Medicaid. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;47(6):596–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden P.M., Jacobson R.M. Impact of a physician recommendation. Hum. Vacc. Immunotherapeut. 2014;10(9):2632–2635. doi: 10.4161/hv.29020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davlin S.L., Berenson A.B., Rahman M. Correlates of HPV knowledge among low-income minority mothers with a child 9–17 years of age. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 2015;28(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.01.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De P., Budhwani H. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine initiation in minority Americans. Public Health. 2017;144:86–91. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente R.J., Murray C.C., Graham T., Still J. Overcoming barriers to HPV vaccination: a randomized clinical trial of a culturally-tailored, media intervention among African American girls. Hum. Vacc. Immunotherapeut. 2015;11(12):2883–2894. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1070996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elam-Evans L.D., Yankey D., Jeyarajah J., Singleton J.A., Curtis R.C., MacNeil J. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13–17 years–United States, 2013. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2014;63(29):625–633. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford C., English A., Sigman G. Confidential health care for adolescents: position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. J. Adolesc. Health. 2004;35(2):160–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu L.Y., Bonhomme L.A., Cooper S.C., Joseph J.G., Zimet G.D. Educational interventions to increase HPV vaccination acceptance: a systematic review. Vaccine. 2014;32(17):1901–1920. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gøtzsche P.C., Jüni P., Moher D., Oxman A.D. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Unpublished and ongoing studies. John Wiley & Sons. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jacobson Vann C., Jacobson R.M., Coyne-Beasley T., Asafu-Adjei J.K., Szilagyi P.G. Patient reminder and recall interventions to improve immunization rates. Cochr. Database Systemat. Rev. 2018 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003941.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeudin P., Liveright E., Del Carmen M.G., Perkins R.B. Race, ethnicity, and income factors impacting human papillomavirus vaccination rates. Clin. Ther. 2014;36(1):24–37. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph N.P., Bernstein J., Pelton S., Belizaire M., Goff G., Horanieh N. Brief client-centered motivational and behavioral intervention to promote HPV vaccination in a hard-to-reach population: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Pediatr. 2016;55(9):851–859. doi: 10.1177/0009922815616244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph N.P., Clark J.A., Bauchner H., Walsh J.P., Mercilus G., Figaro J. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination: ethnic and cultural differences between African-American and Haitian immigrant women. Women's Health Issues. 2012;22(6):e571–e579. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kepka D., Coronado G., Rodriguez H., Thompson B. Acculturation and HPV infection among Latinas in the United States. Prev. Med. 2010;51(2):182–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. ‘I want to know more about the HPV vaccine’: stories by Korean American college women [dissertation]. Boston (MA): University of Massachusetts Boston; 2017.

- Kim M, Lee H, Aronowitz T, Sheldon LK, Kiang P, Allison J, Shi L. An online-based storytelling video intervention on promoting Korean American female college students' HPV vaccine uptake. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2018. Abstract presented at Tenth AACR Conference on The Science of Cancer Health Disparities in Racial/Ethnic Minorities and the Medically Underserved; September 25-28, 2017; Atlanta, GA. DOI: 10.1158/1538-7755.DISP17-C56.

- Layton-Henry Z. Minorities. International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; 2001:9894-8.

- Lee H., Kim M., Cooley M.E., Kiang P.N., Kim D., Tang S. Using narrative intervention for HPV vaccine behavior change among Khmer mothers and daughters: A pilot RCT to examine feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2018;40:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee M.D., Rubin S.E., Campos G., O’Sullivan L.F. Challenges of providing confidential care to adolescents in urban primary care: clinician perspectives. Ann. Family Med. 2011;9(1):37–43. doi: 10.1370/afm.1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E. Meites P.G. Szilagyi H.W. Chesson E.R. Unger J.R. Romero L.E. Markowitz Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 68 2019 698 702 http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3external. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151(4):264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musselwhite L.W., Oliveira C.M., Kwaramba T., de Paula P.N., Smith J.S., Fregnani J.H. Racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening and outcomes. Acta Cytol. 2016;60(6):518–526. doi: 10.1159/000452240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadarzynski T., Smith H., Richardson D., Bremner S., Llewellyn C. Men who have sex with men who do not access sexual health clinics nor disclose sexual orientation are unlikely to receive the HPV vaccine in the UK. Vaccine. 2018;36(33):5065–5070. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.06.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health Sexual and Gender Minority Research Office. About SGMRO, https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sgmro; 2020 [accessed 4 February 2020].

- Ojeaga A., Alema-Mensah E., Rivers D., Azonobi I., Rivers B. Racial disparities in HPV-related knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among African American and White women in the USA. J. Cancer Educ. 2019;34(1):66–72. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1268-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Medina D., Morales-Campos D.Y., Mojica C., Ramirez A.G. Promotora outreach, education and navigation support for HPV vaccination to Hispanic women with unvaccinated daughters. J. Cancer Educ. 2015;30(2):353–359. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0680-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins R.B., Pierre-Joseph N., Marquez C., Iloka S., Clark J.A. Why do low-income minority parents choose human papillomavirus vaccination for their daughters? J. Pediatr. 2010;157(4):617–622. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins R.B., Tipton H., Shu E., Marquez C., Belizaire M., Porter C. Attitudes toward HPV vaccination among low-income and minority parents of sons: a qualitative analysis. Clin. Pediatr. 2013;52(3):231–240. doi: 10.1177/0009922812473775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrosky E., Bocchini J.A., Jr, Hariri S., Chesson H., Curtis C.R., Saraiya M. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2015;64(11):300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter P.L., Katz M.L., Bauermeister J.A., Shoben A.B., Paskett E.D., McRee A.L. Increasing human papillomavirus vaccination among young gay and bisexual men: a randomized pilot trial of the outsmart HPV intervention. LGBT Health. 2018;5(5):325–329. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman A.R., Maddy L., Torres E., Goldberg E.J. A randomized intervention study to evaluate whether electronic messaging can increase human papillomavirus vaccine completion and knowledge among college students. J. Am. Coll. Health. 2016;64(4):269–278. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2015.1117466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez AM, Do TQN, Goodman M, Schmeler KM, Kaul S, Kuo YF. Human Papillomavirus Vaccine interventions in the U.S.: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2019;56(4):5911-602. Doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Saadeh K., Park I., Gargano J.W., Whitney E., Querec T.D., Hurley L., Silverberg M. Prevalence of human papillomavirus (HPV)-vaccine types by race/ethnicity and sociodemographic factors in women with high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN2/3/AIS), Alameda County, California, United States. Vaccine. 2020;38(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluterman N.H., Terplan M., Lydecker A.D., Tracy J.K. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine uptake and completion at an urban hospital. Vaccine. 2011;29(21):3767–3772. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smulian E.A., Mitchell K.R., Stokley S. Interventions to increase HPV vaccination coverage: a systematic review. Hum. Vacc. Immunotherapeut. 2016;12(6):1566–1588. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1125055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F., Hooper L., Loke Y. Publication bias: what is it? How do we measure it? How do we avoid it? Open Access J. Clin. Trials. 2013;5:71–81. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer J.C., Calo W.A., Brewer N.T. Disparities and reverse disparities in HPV vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2019;123:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J.A., Hernán M.A., Reeves B.C., Savović J., Berkman N.D., Viswanathan M. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. The World Bank country and lending groups, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups; 2019 [accessed 4 February 2020].

- Tsui J., Singhal R., Rodriguez H.P., Gee G.C., Glenn B.A., Bastani R. Proximity to safety-net clinics and HPV vaccine uptake among low-income, ethnic minority girls. Vaccine. 2013;31(16):2028–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human Papillomavirus (HPV): HPV fact sheet, https://www.cdc.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv.htm; 2019 [accessed 4 February 2020].

- U.S. Census Bureau. About race, https://www.census.gov/topics/population/race/about.html; 2018 [accessed 4 February 2020].

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. National healthcare quality and disparities report, https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/research/findings/nhqrdr/2018qdr-final.pdf; 2018 [accessed 4 February 2020]. AHRQ Pub. No. 19-0070-EF.

- Van Dyne EA, Henley SJ, Saraiya M, Thomas CC, Markowitz LE, Benard VB. Trends in Human Papillomavirus–Associated Cancers — United States, 1999–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018;67:918–924. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a2external. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Waller J., Marlow L.A., Wardle J. Mothers' attitudes towards preventing cervical cancer through human papillomavirus vaccination: a qualitative study. Cancer Epidemiol. Prevent. Biomark. 2006;15(7):1257–1261. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walling E.B., Benzoni N., Dornfeld J., Bhandari R., Sisk B.A., Garbutt J., Colditz G. Interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheldon C.W., Sutton S.K., Fontenot H.B., Quinn G.P., Giuliano A.R., Vadaparampil S.T. Physician communication practices as a barrier to risk-based HPV vaccine uptake among men who have sex with men. J. Cancer Educ. 2018;33(5):1126–1131. doi: 10.1007/s13187-017-1223-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widdice L.E., Bernstein D.I., Leonard A.C., Marsolo K.A., Kahn J.A. Adherence to the HPV vaccine dosing intervals and factors associated with completion of 3 doses. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):77–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer R.L., Gonzales A.A., Noonan C.J., Buchwald D.S. A Cluster-randomized trial to evaluate a mother-daughter dyadic educational intervention for increasing HPV vaccination coverage in american indian girls. J. Commun. Health. 2016;41(2):274–281. doi: 10.1007/s10900-015-0093-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.