Abstract

Rationale and Objectives

To assess the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology education, and to propose measures to preserve and augment trainee education during future crises.

Materials and Methods

Diagnostic Radiology (DR) studies and Interventional Radiology (IR) procedures at a single tertiary-care teaching institution between 2015 and 2020 were reviewed. DR was divided by section: body, cardiothoracic, musculoskeletal (MSK), neuroradiology, nuclear medicine, pediatrics, and women's imaging. IR was divided by procedural types: arterial, venous, lymphatic, core, neuro, pediatrics, dialysis, cancer embolization or ablation, noncancer embolization, portal hypertension, and miscellaneous. Impact on didactic education was also assessed. ANOVA, t test, and multiple comparison correction were used for analysis.

Results

DR and IR caseloads decreased significantly in April 2020 compared to April of the prior 5 years (both p < 0.0001). Case volumes were reduced in body (49.2%, p < 0.01), MSK (54.2%, p < 0.05), neuro (39.3%, p < 0.05), and women's imaging (75.5%, p < 0.05) in DR, and in arterial (62.6%, p < 0.01), neuro IR (57.6%, p < 0.01) and core IR (42.6%, p < 0.05) in IR. IR trainee average caseload in April 2020 decreased 51.9% compared to April of the prior 5 years (p < 0.01). Utilization of online learning increased in April. Trainees saw significant increases in overall DR didactics (31.3%, p = 0.02) and no reduction in IR didactics, all online. Twelve major national and international DR and IR meetings were canceled or postponed between March and July.

Conclusion

Decreases in caseload and widespread cancellation of conferences have had significant impact on DR/IR training during COVID-19 restrictions. Remote learning technologies with annotated case recording, boards-style case reviews, procedural simulation and narrated live cases as well as online lectures and virtual journal clubs increased during this time. Whether remote learning can mitigate lost opportunities from in-person interactions remains uncertain. Optimizing these strategies will be important for potential future restricted learning paradigms and can also be extrapolated to augment trainee education during unrestricted times.

Keywords: Education, IR/DR Residency, Quality Improvement, Virtual training, COVID

INTRODUCTION

On March 11th, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the novel SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic (1). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) first issued guidance for healthcare professionals and institutions in the US on February 28th, 2020, urging healthcare facilities to reschedule nonurgent outpatient visits, consider accelerating the timing of high priority screening and intervention needs for the short-term in anticipation of an influx of COVID-19 patients in the following weeks, reschedule elective surgeries and shift elective urgent inpatient diagnostic and surgical procedures to outpatient settings when feasible (2). With minor variability due to state guidelines and local availability of personal protective equipment (PPE), almost all healthcare institutions adopted the CDC guidelines (3, 4, 5).

In terms of Radiology practice, many institutions resorted to categorizing diagnostic imaging appointments and interventional radiology procedures into three general categories: non-urgent, semi-urgent, and urgent. A majority of nonurgent appointments, including elective screening appointments and imaging studies, were rescheduled to a later date. Semiurgent cases were processed on a case-by-case basis. Urgent appointments or appointments where delays would significantly compromise patient health were kept as planned. Some institutions elected to proceed with all cancer-related appointments and therapies as semi-urgent or urgent (6,7). At academic medical centers, diagnostic radiologists were able to work remotely using home work-stations. Some Interventional Radiology practices created teams of physicians, trainees, nurses and technologists to minimize cross-contamination of a potential exposure event (8, 9, 10, 11).

The dramatic changes in case volume and variety resulting from restricted scheduling may have significant impact on trainee exposure and education. Measures to minimize cross-contamination and workplace exposure could also negatively impact trainee participation in clinical care and in-person teaching. Furthermore, the duration of such restrictions is hard to predict, and the likelihood of needing to readdress this issue during future times of restricted scheduling seems both imminent for COVID-19 should a “second wave” occur, as well as probable for future pandemics.

The aim of this study was to assess the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on major aspects of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology education, and to propose measures to preserve or augment the trainee educational experience during similar crises.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Diagnostic Radiology (DR) studies and Interventional Radiology (IR) procedures at a single tertiary-care teaching institution between 2015 and 2020 were reviewed using a locally-developed institutional Radiology database search engine. The program has 25 diagnostic radiology residents, 10 diagnostic radiology fellows, and 5 interventional radiology fellows. There are 35 diagnostic radiology attending faculty members at the teaching hospital, 10 diagnostic radiology attending faculty members at the affiliated VA hospital, and 10 interventional radiology attending faculty members. DR was divided by section: body imaging, cardiothoracic imaging, musculoskeletal (MSK) imaging, neuroradiology, nuclear medicine, pediatrics, and women's imaging. IR was divided by procedural types: arterial, venous, lymphatic, core IR, neuro IR, pediatrics IR, dialysis, cancer embolization or ablation, noncancer nonhemorrhagic embolization, portal hypertension, and miscellaneous. Core IR included the following procedures: central venous catheter placement, drainage procedures, enteral tube placement, and biopsies.

Number and type of didactic learning activities, interdisciplinary clinical work conferences and tumor boards within the institution were compared prior to and after the outbreak. Cancellations of major national and international Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology meetings that were originally scheduled between March and June of 2020 were reviewed.

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Case volume percentage change was calculated by comparing with the average case volume in the same month of the last 5 years. Statistical analysis including Mann-Whitney nonparametric t-test, two-way ANOVA, and multiple t-tests using Holm-Sidak multiple comparison significance level adjustment were performed using Prism (GraphPad, Version 7.00, San Diego, CA). A two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Linear regression, high-order polynomial as well as exponential equations (decay and growth) and one-phase association decay were used to model the observed changes in IR caseload. Upper and lower 95% confidence bands of these fitted curves were examined to make short-term extrapolations. The best-fitted model was also used to assess the impact of a future pandemic with similar restricted social and hospital operational policies.

RESULTS

Changes in Caseload and Case Variety

Examination of overall caseload demonstrated significant differences in caseload trend from January through April of 2020 in DR and IR compared with that observed in the previous 5 years (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively). Additional analysis showed significant decreases in DR and IR caseloads specifically for April 2020 compared with caseloads in the other months of 2020 (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively) as well as with caseloads in April of the past 5 years (p < 0.001 and p < 0.01, respectively).

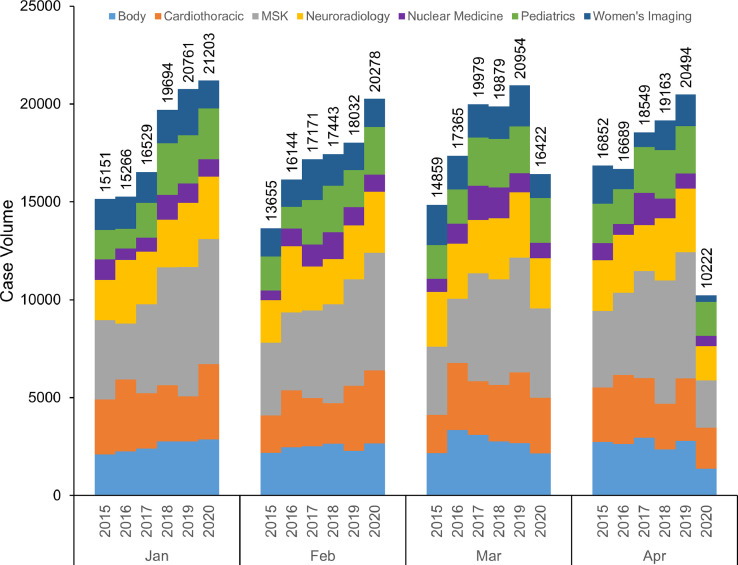

DR cases were divided into 7 categories based on section assignment ( Fig 1, Supplemental Table 1). Body imaging (49.2% decrease, p < 0.01), MSK (54.2% decrease, p < 0.05), neuroradiology (39.3% decrease, p < 0.05), and women's imaging (75.5% decrease, p < 0.05) demonstrated significant case volume decreases when compared with the same month in the past 5 years. The other 3 sections (cardiothoracic, nuclear medicine, and pediatrics with 29.3%, 44.7%, and 21.7% reduction, respectively) showed large percentage decreases in case volume; however, these numbers did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 1.

Stacked bar graph of Diagnostic Radiology (DR) caseload and varieties of January to April of 2020 in comparison with the previous 5 years (2015–2019). MSK, musculoskeletal.

IR procedures were also further characterized in sub-categories ( Fig 2, Supplemental Table 2). Neuro (57.6% decrease, p < 0.01), arterial (62.6% decrease, p < 0.01), and core IR procedures (42.6% decrease, p < 0.05) showed significant case volume decrease when compared with the same month in the past 5 years. Overall cancer-related interventions did not experience significant case volume reduction (21.4% decrease with p > 0.05). Dialysis (41.2% decrease), Miscellaneous (35.5% decrease), and Pediatrics (49.7% decrease) demonstrated large percentage reduction in case volume; however, these changes did not demonstrate statistical significance. Lymphatic, noncancer nonhemorrhagic embolization, venous and portal hypertension case volume did not vary significantly in April 2020 compared to the previous 5 years (p > 0.05).

Figure 2.

Stacked bar graph of Interventional Radiology (IR) caseload and varieties of January to April of 2020 in comparison with the previous 5 years (2015–2019). Misc, miscellaneous; PHTN, portal hypertension; Peds, pediatrics. Core IR included the following procedures: central venous catheter placement, drainage procedures, enteral tube placement, and biopsies.

At the trainee level, average IR fellow caseload decreased significantly in April 2020, amounting to a 51.9% reduction in April 2020 compared to the same month in the past 5 years and a 47.8% reduction compared to the first three months of 2020 (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively).

Educational Activities

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, DR residents at this institution typically had 8 ± 0.8 hours per week of in-person teaching didactics. In April 2020, DR residents had 12.8 ± 1.6 hours per week of teaching didactics, representing a 31.3% overall increase (p < 0.05) all via remote web-based applications and conferencing. Most interdisciplinary clinical work conferences, such as tumor boards, continued to be held through virtual platforms, with similar amounts of trainee exposure and participation (approximately 2 hours per week). There was no interruption in IR-related didactics, also administered through a virtual platform. These included didactic lectures, “hot-seat” boards-style sessions, journal clubs and morbidity and mortality conferences. In addition, multiple sections established dedicated case-of-the-day online repositories with regularly updated cases and teaching points. National web-based live conferences and recorded lecture series were widely shared by faculty members and residents.

National and International Conferences

Between March and June of 2020, 14 major national and international Radiology meetings were canceled or postponed as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

List of Major National and International Radiology Meetings That Have Been Impacted by COVID-19, As of May 2020

| Conference/Event | Original Venue | Original Dates | Action Taken |

|---|---|---|---|

| Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) 2020 Annual meeting | Seattle, WA | 3/28/2020-4/2/2020 | Will be offered as a virtual meeting only |

| Society of Skeletal Radiology (SSR) 2020 Annual Meeting | Huntington Beach, CA | 3/29/2020-4/1/2020 | Canceled |

| Canadian Association of Radiologists (CAR) 2020 Annual Meeting | Montreal, Canada | 4/16/2020-4/19/2020 | Canceled |

| The 18th Clinical Nuclear Medicine 2020 | Las Vegas, NV | 4/23/2020-4/24/2020 | Will be offered as a live webinar only |

| Artificial intelligence and machine learning in Cardiovascular CT meeting | New York, NY | 4/24/2020-4/26/2020 | Rescheduled to April 2021 |

| European Conference on Interventional Oncology (ECIO) 2020 | Niece, France | 4/26/2020-4/29/2020 | Rescheduled to 11/2/2020 to 11/5/2020 |

| American Rontgen Ray Society (ARRS) 2020 meeting | Chicago, IL | 5/3/2020-5/8/2020 | Canceled |

| Society of Pediatric Radiology 2020 Annual Meeting & Postgraduate Course | Miami, FL | 5/9/2020-5/15/2020 | Canceled |

| Global Embolization and Technologies (GEST) 2020 conference | New York, NY | 5/14/2020-5/17/2020 | Rescheduled to 9/2/2020 to 9/5/2020 |

| Medical Imaging Informatics and Teleradiology (MIIT) 2020 conference | Ontario, Canada | 5/15/2020 | Will be offered as a virtual meeting only |

| American College of Radiology (ACR) 2020 Annual meeting | Washington, DC | 5/16/2020-5/19/2020 | Will be offered as a virtual meeting only |

| Canadian Association for Interventional Radiology (CAIR) 2020 Annual meeting | Canada | 5/28/2020-5/30/2020 | Canceled |

| European Congress of Radiology (ECR) 2020 | Vienna, Austria | 6/15/2020-6/19/2020 | Will be offered as a virtual meeting only |

| Asian Oceanian Congress of Radiology (AOCR) 2020 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 6/23/2020-6/26/2020 | Rescheduled to July 2021 |

Prediction Models for IR Case Volume

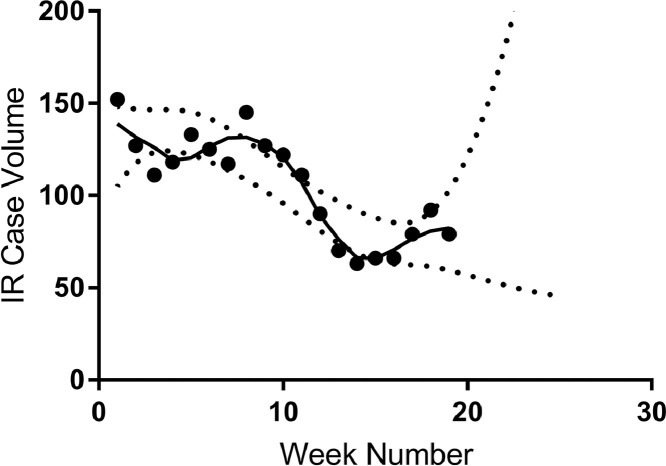

Modeling trends for IR case volume presented a wide variety of outcomes with the current COVID-19 pandemic. Case increases were noted in the latter half of May, coincident with easing of state government restriction policies on semi-elective case scheduling. Using the observed trends in case volume, the most optimistic model predicted a return to former IR case volume at week 21.6 of 2020, or the week of May 24th, 2020 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 20.8–22.4), approximately 12 weeks after the initial decline in caseload and 7 weeks after reaching the nadir at 56.9% of average weekly case volume in April compared to the past 5 years ( Fig 3). The best-fitted model (fourth-order polynomial) was additionally used to assess the impact of a possible future pandemic on IR case volume. Under similar social and hospital policies, the model estimated an initial 7.0-week (95%CI: 6.3–7.9) decline to a nadir of 50% of regular operational capacity.

Figure 3.

Interventional Radiology (IR) case volume in 2020 by week. Dashed lines represented the upper and lower 90% confidence intervals of a fitted fourth-order polynomial curve (R2 = 0.7767). Week number denotes the chronological week-by-week divide in 2020; i.e. week 1 represents Jan 5th, 2020 to Jan 11th, 2020.

DISCUSSION

Implications on DR Trainee Education

The significant decrease in case volumes observed during the COVID-19 pandemic is multifactorial. Overall, the impact of state-mandated reduction in elective procedures was likely a primary driver of volume reduction. Case volume reduction in Body and Neuroradiology possibly reflected an additional decrease in trauma cases, postponement of nonurgent clinical care, and patient reluctance to visit the emergency room. The decrease in MSK caseload likely reflected sequelae of the government implemented “stay-at-home" mandate with potential decrease in trauma, deferral of work-up for sports-related injuries and degenerative joint disease, and follow-up of rheumatologic disease. The significant decrease in caseload in Women's imaging may have stemmed from deferral of primary screening volume.

Such significant decreases in case volume may impede DR resident ability to fulfill graduation requirements. For example, residents are required to complete 12 weeks of clinical rotations in breast imaging including logging the supervised interpretation of at least 240 screening mammograms within a 6-month time block (12). Furthermore, programs offering an integrated IR residency are required to have at least 7,000 radiological examinations per year per resident in both the diagnostic radiology program and in the PGY-2–4 years of the integrated IR program (13). Although case volume in nuclear medicine did not demonstrate a statistically significant change, a 44.7% decrease in volume may still be detrimental given the required 700 hours of clinical training and 80 hours of laboratory training for graduation. Moreover, trainees may not be able to sufficiently log three supervised I-131 administrations in time to receive authorized user status as part of their residency experience. If long lasting impacts on imaging volume is observed, some programs might consider the option of allowing residents to interpret already finalized studies from case archives as a potential way of fulfilling graduation requirements (14). Compared to the considerable decrease in in-person supervision, feedback, and didactics, all of which are crucial components of Radiology education, utilization of web-based live conferences and recorded lectures experienced a notable increase. The effectiveness of virtual studying in the context of potentially inadequate actual case exposure and repetitive learning, however, remains unclear.

Implications on Hands-on Experience for IR Trainees

Analysis of IR case volume showed significant reductions impacting trainee experience. Case volume decrease in Neuro IR may have been attributed to a heavy dependence on general anesthesia services, and therefore, curtailing of elective cases. Significant caseload decreases in Arterial and Core IR may have been reflective of the general decrease in hospital operational capacity.

For current IR fellows, the reduction in hands-on training could have more dire consequences given the relatively more compressed educational time-frame and graduation requirement of 500 cases. For example, significant challenges may be encountered at programs with generally smaller volumes, and if restrictions were to last longer, or were to have happened earlier in the academic year. For residents with a typical monthly rotational schedule, this decrease in trainee involvement also significantly impacted their IR exposure; however, there is potentially more opportunity for residents to make-up this experience over the longer course of a multi-year residency. IR residents in the Early Specialization in Interventional Radiology (ESIR) training pathway are required to complete 11 IR-related rotations and a rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) (15). In addition, residents are expected to complete 500 cases during their diagnostic radiology residency. In response to COVID-19, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) is allowing residents in programs significantly impacted by the pandemic to enter independent interventional radiology residencies with fewer than 500 logged cases (14). Nevertheless, residents will still be expected to log a total of at least 1000 cases by the end of their interventional radiology residency. ESIR residents unable to complete their ICU rotation can also graduate with a requirement on the receiving Interventional Radiology Independent program to provide a one-month ICU rotation for such residents (14). Faced by similar, but potentially more significant, decrease in surgical trainee caseload, the American Board of Surgery (ABS) approved a 10% decrease in operative case numbers logged by chief residents completing training in 2020 as well as counting non-voluntary offsite time used for clinical or educational purposes as clinical time (16). Whether the drop in the IR trainee caseload is significant enough to warrant a similar step remains unclear.

Compared to the measurable effect on caseload and variety, the impact of limited faculty member exposure on hands-on learning cannot be precisely quantified. As a result of the team organization to minimize cross-exposure, trainees on their IR rotation have been exposed to the same teaching faculty members between March 23rd and June 1st. Faculty members are key pillars in fellowship and residency training through the transference of knowledge, skill, and behavior from the educator to the learner. While the ACGME did not state a minimum core teaching faculty number for DR programs, it delegated the task of specifying the minimum number of core faculty and/or core faculty-trainee ratio to the Review Committee, highlighting the importance of exposure to a diversified faculty profile for proper teaching experience (17). For IR programs, a minimum of at least two full-time equivalent interventional radiologists are required to run a program (13).

While remote access to Radiology workstations and advances in telecommunications have enabled a remote learning environment in DR (7,18,19), the hands-on nature of IR training makes it more challenging in a virtual setting. There is currently no sufficient evidence in the literature to support the validity of remote and simulated training in IR and its effect on patient outcomes. Thus, these virtual modalities should be regarded as adjunct to conventional hands-on training (20).

Week-by-week IR case volume was used to model the trend of caseload during this pandemic and provide information for potential future crises. Assuming similar social guidelines and hospital policies, the best fitted model demonstrated a U shaped response with an initial 7 week decline to a nadir of approximately 50% of regular operational capacity and a total duration of 12 weeks of reduced capacity. Educators and administrators may use this information to anticipate the reduction in trainee educational experience and implement pre-emptive measures. Monthly rotation schedule may be adjusted to balance the caseload among trainees and to maximize the chances of meeting graduation requirements. Virtual learning may be planned with a multi-week longitudinal milestone design with interval assessment. Nonclinical, intermediate term, research may be an excellent measure to keep trainees engaged and help them progress academically. Upon reaching the nadir, faculties and trainees should prepare for a fast return to regular operational capacity. Re-orientation and mutual establishment of modified training objectives/priorities may be appropriate.

Local, National, and International Conferences

National and international conferences are integral for postgraduate medical education, career development and networking, which is particularly important for fellows in their final year of postgraduate medical training. Conferences provide diversified learning opportunities that might not be possible in the setting of conventional didactic education. Residents have previously relied on conferences to learn about practice at other institutions, network with mentors and help with job search (21,22). While 14 major national and international Radiology meetings have already been canceled or postponed between March and June 2020, the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) has announced plans to hold the 2020 Annual Meeting – originally planned for November 29 – December 5, 2020 in Chicago - as a virtual event. This move highlights the potential for a more long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on academic progress and events scheduled for the rest of the year, as well as a direction towards wider adoption of virtual meetings particularly for larger events. At the local level, institutional research meetings and multidisciplinary conferences continued to be held in many institutions remotely through video conferencing solutions (7,23).

Lessons Learned and Mitigation Planning

While the observations presented previously illustrate the fact that these are challenging times with serious implications on medical practice and training programs, it is important to recognize that grave circumstances and times of crisis have always inspired positive changes for postgraduate medical training in the US. In 1981, the ACGME itself was founded over concerns of lack of standardized quality in resident education and the emerging formalization of subspecialty education (24). Similarly, the introduction of duty hour limits in 2011 were implemented following growing awareness of resident fatigue and safety issues (25) and the overhaul of the accreditation system in 2013 occurred over concerns of lack of innovation within the residency programs and program director burnout related to administrative tasks (26).

Review of Successful Remote Learning Efforts During the Current Pandemic

Rules of social distancing and other exceptional measures introduced to minimize the spread of COVID-19 have negatively impacted scheduled group meetings and face-to-face educational activities nationwide. They have also mandated the transition towards virtual meetings and distance learning technologies. While the transition was largely rushed, some efforts have been carefully executed.

SIR Virtual Meeting and Digital Video Library

Building upon the digital video library (DVL) concept, which features digital audio and video recordings for meeting presentations for later viewing, the SIR shifted its 2020 annual scientific meeting, originally planned for March 28th to April 2nd, into a digital-only format. All poster presentations were converted into e-posters and participants with oral presentations were advised to use a web-based suite, Echo360 (Reston, VA), to capture their presentations with audio visual overlay to be included in the DVL with plans for a future online only meeting where these presentations can be live-streamed to an online audience.

RSNA Case Collection

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the RSNA accelerated the launch of a new collaborative educational tool called RSNA Case Collection. The service works as a peer-reviewed online library of educational cases where members can contribute cases organized by subspecialty. Trainees and radiologists can review and practice using the published cases.

GEST Online Webinar Series

The Global Embolization Symposium and Technologies (GEST) conference was originally scheduled for May 15th, 2020 but was postponed to September. Alternatively, GEST hosted a successful series of online webinars bringing panelists from all over the world to discuss their experience running an IR practice during a pandemic. Their first webinar titled “Learning from Global Experience” had more than 500 virtual attendees (27). Two more webinars streamed online in April 2020 covering topics related to COVID-19 including experience with personal protective equipment (PPE), patient selection and testing, as well as a panel on prostate artery embolization.

Study Limitations

This study has some limitations. Only one tertiary-care teaching institution is included in the study. While a degree of variation will certainly exist between different institutions, the general concepts, implications and mitigation efforts are likely to be generalizable. In addition, the study examines only short-term implications on Radiology education, between March and July. Other long-term future implications are likely and should be the target for future studies. Furthermore, the utility of the beforementioned online educational efforts remain challenging to accurately assess given the early time point in this experience.

CONCLUSION AND POTENTIAL FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR AUGMENTED DR/IR TRAINEE EDUCATION

The rate of change and adaptation within the healthcare system to the COVID-19 pandemic has been unprecedented. However, with many unknowns and the potential of recurrent pandemic waves, it is important to proactively devise ways to preserve medical education to ensure optimal trainee experience. It will be imperative for a concerted effort to begin at a national level inclusive of major stakeholders in DR/IR trainee education to collaboratively address how best to meet educational standards. Innovative ways to use existing technologies for virtual experiences could be leveraged to support this effort. Potential thoughts and suggestions include the following:

-

•

Recorded/live cases to share with trainees both intra-institutionally and inter-institutionally, potentially through a coordinated effort by national societies such as the RSNA, SIR and the American College of Radiology (ACR).

-

•

Online lecture series with live and on-demand streaming to trainees within the same institution or for multi-institutional virtual educational meetings.

-

•

Establishment of a digital repository for educational cases, particularly for rare cases, to guarantee trainee exposure.

-

•

Digital ‘case of the day’ with verbal breakdown by staff and recorded for archiving.

-

•

Regularly scheduled virtual journal clubs.

-

•

Regularly scheduled self-testing/evaluation to monitor trainee education progress during times of restricted operations.

-

•

Wider adoption of standardized online tools for formative assessment of resident education. One example is RadExam, a collaborative effort of the Association of Program Directors in Radiology (APDR) and the ACR, which provides a versatile set of psychometrically validated, peer-reviewed examinations based on the American Board of Radiology (ABR) study guides.

-

•

Potential innovations around simulator-based training and assessment. Simulator training and assessment can also be expanded to assess progress in clinical skills, akin to the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) platform implemented by medical schools.

It remains unclear whether these remote learning strategies can mitigate lost opportunities from direct in-person interactions. Optimizing these strategies, however, will be important for potential future restricted learning paradigms, and would ideally be extrapolated to augment trainee education during unrestricted times.

Footnotes

Institution where the work originated: Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd, Portland, OR 97239, USA.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.acra.2020.07.014.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.WHO. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020 [Internet]. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020. Accessed March 11, 2020.

- 2.CDC. Interim Guidance for Healthcare Facilities: Preparing for Community Transmission of COVID-19 in the US | CDC [Internet]. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/guidance-hcf.html. Accessed February 29, 2020.

- 3.Meyer M, Prost S, Farah K. Spine surgical procedures during coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: is it still possible to take care of patients? Results of an observational study in the first month of confinement. Asian Spine J [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.31616/asj.2020.0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown TS, Bedard NA, Rojas EO. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on electively scheduled HIP and KNEE arthroplasty patients in the United States. J Arthroplasty [Internet] 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2020.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams AM, Kalra G, Commiskey PW. Ophthalmology practice during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic : the University of Pittsburgh experience in promoting clinic safety and embracing video visits. Ophthalmology and Therapy. 2020;2019:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s40123-020-00255-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavallo JJ, Forman HP. The economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on radiology practices. Radiology [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luker GD, Boettcher AN. Transitioning to a new normal after COVID-19: preparing to get back on track for cancer imaging. Radiol Imaging Cancer [Internet] 2020;2 doi: 10.1148/rycan.2020204011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mossa-Basha M, Meltzer CC, Kim DC. Radiology department preparedness for COVID-19: radiology scientific expert panel. Radiology [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mossa-Basha M, Medverd J, Linnau K. Policies and guidelines for COVID-19 preparedness: experiences from the University of Washington. Radiology [Internet] 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandy PE, Nasir MU, Srinivasan S. Interventional radiology and COVID-19: evidence-based measures to limit transmission. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2020;26:236–240. doi: 10.5152/dir.2020.20166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denys A, Guiu B, Chevallier P. Interventional oncology at the time of COVID-19 pandemic: Problems and solutions. Diagn Interv Imaging [Internet] 2020;101(6):347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2020.04.005. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32360351 S2211-5684(20)30100-5 Available at: Accessed April 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.FDA. Residency Letter for Residency Graduates of 2014 or Later | FDA [Internet]. 2018[cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/radiation-emitting-products/facility-certification-and-inspection-mqsa/residency-letter-residency-graduates-2014-or-later. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 13.ACGME. ACGME Program requirements for graduate medical education in interventional radiology (integrated and independent) [Internet]. 2019[cited 2020 Feb 7]. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/415-416_InterventionalRadiology_2019_TCC.pdf?ver=2019-06-05-131641-600. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 14.ACGME. Special communication to diagnostic radiology residents, interventional radiology residents, subspecialty radiology fellows, and program directors [Internet].2020 p. 1–4. Available at: www.acgme.org/COVID-19. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 15.ACGME. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in diagnostic radiology. 2014;1–24. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ReviewandComment/420_DiagnosticRadiology_2019-08-12_Impact.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- 16.Fong ZV, Qadan M, Jr RM, et al. Practical implications of novel coronavirus COVID-19 on hospital operations, board certification, and medical education in surgery in the USA. 2020; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.ACGME Common program requirements 2007. ACGME. 2007;58(12):7250–7257. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_04012007.pdf [Internet].Available at: Accessed April 15, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fefferman NR, Strubel NA, Prithiani C. Virtual radiology rounds: adding value in the digital era. Pediatr Radiol [Internet] 2016;46(12):1645–1650. doi: 10.1007/s00247-016-3675-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zember J, Saul D, Delgado J. Radiology rounds in the intensive care units through a telepresence model. J Am Coll Radiol [Internet] 2018;15(11):1655–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel R, Dennick R. Simulation based teaching in interventional radiology training: is it effective? Clin Radiol [Internet] 2017;72(3) doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2016.10.014. 266.e7-266.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homayounfar K, König S, Rabe C. Personalgewinnung und -entwicklung in viszeralchirurgischen Kliniken von Groβkrankenhäusern – derzeitiger Stand und Möglichkeiten der Optimierung aus Industrie und Dienstleistungsgewerbe [Recruiting and personal development in surgical departments of large referral centers – current practice and options for improvement from industry and service business] Zentralbl Chir. 2017;142(6):566–574. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-109562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mason BS, Landry A, Sánchez JP. How to find an academic position after residency: who, what, when, where, why, and how. MedEdPORTAL J Teach Learn Resour [Internet] 2018;14:10727. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10727. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30800927 Available at: Accessed April 15, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panel SE, Vagal A, Reeder SB, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the radiology research enterprise: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Benson J. Enhancing standards of excellence in internal medicine training. Ann Intern Med [Internet] 1987;107(5):775–778. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-5-775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Philibert I, Friedmann P, Williams WT. Hours for the members of the AWG on RD. New requirements for resident duty hours. JAMA [Internet]. 2002;288(9):1112–1114. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.9.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T. The next GME accreditation system — rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med [Internet] 2012;366(11):1051–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1200117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Interventional News. GEST COVID-19 webinar: lessons from the frontlines in Singapore [Internet]. 2020. Available at:https://interventionalnews.com/singapore-covid-19-gest/. Accessed April 15, 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.