Abstract

Background

Preventing severe complications of influenza such as hospitalization is a public health priority; however, estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) against influenza-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) hospitalizations are limited. We examined influenza VE against influenza-associated LRTIs in hospitalized adult patients.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed data from a randomized trial of oseltamivir treatment in adults hospitalized with LRTI in Louisville, Kentucky, from 2010 to 2013. Patients were systematically tested for influenza at the time of enrollment. We estimated VE as 1 – the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of antecedent vaccination in influenza-positives vs negatives × 100%. Vaccination status was obtained by patient self-report. Using logistic regression adjusting for age, sex, season, timing of illness, history of chronic lung disease, and activities of daily living, we estimated VE against hospitalized influenza-associated LRTIs and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) with radiographic findings of infiltrate.

Results

Of 810 patients with LRTI (median age, 62 years), 184 (23%) were influenza-positive and 57% had radiographically confirmed CAP. Among influenza-positives and -negatives, respectively, 61% and 69% were vaccinated. Overall, 29% were hospitalized in the prior 90 days and >80% had comorbidities. Influenza-negatives were more likely to have a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease than influenza-positives (59% vs 48%; P = .01), but baseline medical conditions were otherwise similar. Overall, VE was 35% (95% CI, 4% to 56%) against influenza-associated LRTI and 51% (95% CI, 13% to 72%) against influenza-associated radiographically confirmed CAP.

Conclusions

Vaccination reduced the risk of hospitalization for influenza-associated LRTI and radiographically confirmed CAP. Clinicians should maintain high rates of influenza vaccination to prevent severe influenza-associated complications.

Keywords: hospitalization, influenza, lower respiratory tract infection, pneumonia, vaccine effectiveness

Influenza is a cause of significant morbidity and mortality in the United States, resulting in 140 000–810 000 hospitalizations and 12 000–61 000 deaths annually [1]. Although most influenza infections result in self-limited upper respiratory symptoms, infection can result in more serious lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs), including pneumonia [2, 3]. Pneumonia is the most common serious respiratory complication of influenza virus infection [4–6], and in the United States, influenza and pneumonia are the leading causes of infection-related mortality [7].

Unlike other respiratory viral infections, influenza is preventable through vaccination, and the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends yearly vaccination against influenza for all people aged ≥6 months in the United States [8]. Each year, influenza vaccination is estimated to prevent 700 000–3 500 000 medical visits, 39 000–100 000 hospitalizations, and 3700–12 000 deaths in the United States [9]; however, specific estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) may vary depending on the season. The most common sources for VE estimates in the United States are research platforms built from medically attended influenza virus infections in the outpatient setting. Although annual research activities for VE in the United States have now expanded to the inpatient setting [10], little is known about the effectiveness of influenza vaccine for prevention of influenza-associated LRTI. Among studies that have examined this question, most have relied upon nonspecific International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes to identify LRTI diagnoses [11–15]. Use of all-cause diagnoses may result in underestimation of the true influenza-specific VE estimates, as only a fraction of cases are associated with influenza [16, 17].

In our study, we used prospectively identified patients with LRTI who were systematically tested for influenza. We estimated VE against laboratory-confirmed influenza in hospitalized adults with LRTI in the primary analysis and calculated VE for specific LRTI diagnoses, including community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (aeCOPD). We further explored whether VE against LRTI was different in those with vs without chronic lung disease.

METHODS

Study Design, Setting

We retrospectively analyzed data from a randomized clinical trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of oseltamivir treatment vs standard of care alone in adults aged ≥18 years hospitalized with LRTIs from 2010 to 2013 (Rapid Empiric Treatment with Oseltamivir Study [RETOS]; clinicaltrials.gov #NCT01248715) [18]. Patients eligible for the trial presented with symptoms of acute LRTI (Supplementary Figure 1) and were admitted to hospitals in Louisville, Kentucky. Trial enrollment occurred at 4 hospitals during 2010–2011, 8 hospitals during 2011–2012, and 9 hospitals during 2012–2013. Patients qualified for the study if they were enrolled within 48 hours of hospital admission, did not receive an admission order for oseltamivir or zanamivir, and had no known allergy to oseltamivir. Individuals were excluded from enrollment if they were pregnant or incarcerated. Patients were categorized into mutually exclusive acute LRTI groups based on standardized diagnostic criteria used by the RETOS principal investigators: CAP [19], aeCOPD [20], or acute bronchitis [21]. Hospital-acquired pneumonia was not included in this study. Study staff obtained nasopharyngeal swabs from all participants. Specimens were tested for 12 respiratory viral pathogens using a molecular assay, Luminex xTAG [22]. Patients were categorized into acute LRTI groups before availability of influenza testing results.

Consented patients were interviewed by trained study officers, and data were prospectively collected on patient demographic characteristics (including age and sex), social history (including smoking status and whether the patient was a current nursing home resident), history of present illness (including recent hospitalizations and self-reported ability to complete activities of daily living [ADLs]), and influenza vaccination status. Study officers performed medical record abstractions to gather information on underlying medical conditions, medical imaging, and clinical outcomes.

Data Sources and Variables

We defined a laboratory-confirmed case of influenza as detection of influenza by molecular assay; participants who tested negative for influenza were enrolled as controls (controls could have tested positive for another pathogen). We considered a patient vaccinated if they self-reported influenza vaccination for the current influenza season. Date of vaccination and validation were not available, and self-reported vaccination was not verified. Among patients with a clinical diagnosis of CAP, we defined radiographically confirmed pneumonia as chest x-ray or chest computed tomography (CT) findings of a new pulmonary infiltrate within 48 hours of admission, as determined by a board-certified radiologist [4, 23].

To assess frailty, 6 subjective questions were asked during the enrollment interview assessing the patients’ ability to complete ADLs, including bathing, dressing, eating, getting in or out of chairs, walking, and using the toilet; responses ranged from 1 (able to do activity with no difficulty) to 3 (unable to do this activity) (Supplementary Figure 2). We created a mean frailty score by calculating the average responses across the 6 questions.

Statistical Analysis

For analysis, we included enrollees who were admitted within 10 days of symptom onset and excluded patients who were missing data for age or vaccination status. We used the Rao-Scott χ 2 or the 2-tailed Fisher exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables to compare baseline characteristics of influenza-positive and influenza-negative patients and vaccinated and unvaccinated patients.

We calculated VE against influenza-associated LRTIs by comparing odds of antecedent vaccination among those who tested influenza positive compared with those who tested negative using logistic regression models [24], where VE = 100 × (1 – adjusted odds ratio). We excluded influenza-negative controls enrolled before the first and last influenza-positive specimen for the season.

All models were adjusted a priori for season, age in years, sex, timing of illness (using tertiles of admission date), and mean frailty score. We also adjusted for variables with P < .20 in either of the univariate analyses involving influenza or vaccination status. These variables were included in the final model if they changed the odds ratio for vaccination by >10%. The final models included the a priori variables, hospitalization for ≥2 days in the last 90 days, and chronic lung disease, defined as either a history of COPD or home oxygen use (documented by the clinical team in the patient’s medical chart). We chose to include chronic lung disease in the model in place of smoking status, as the 2 variables were collinear and chronic lung disease is on the causal pathway between smoking and acute LRTI. Chronic lung disease was not included in the subgroup analysis model where patients were stratified by history of chronic lung disease.

Our primary VE analysis included all influenza-associated hospitalized LRTI as the outcome. In secondary analysis, we assessed VE using influenza-associated radiographically confirmed CAP and aeCOPD as outcomes. Lastly, we performed an exploratory analysis stratified by history of chronic lung disease in those with radiographically confirmed CAP and LRTI. We evaluated the difference of VE in these 2 groups for any statistical significance by including an interaction term between chronic lung disease and receipt of influenza vaccination in the model.

We considered P values <.05 to be statistically significant. We analyzed data using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA). Before enrollment of subjects, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and participating research institution and hospital obtained institutional review board approval for the study.

RESULTS

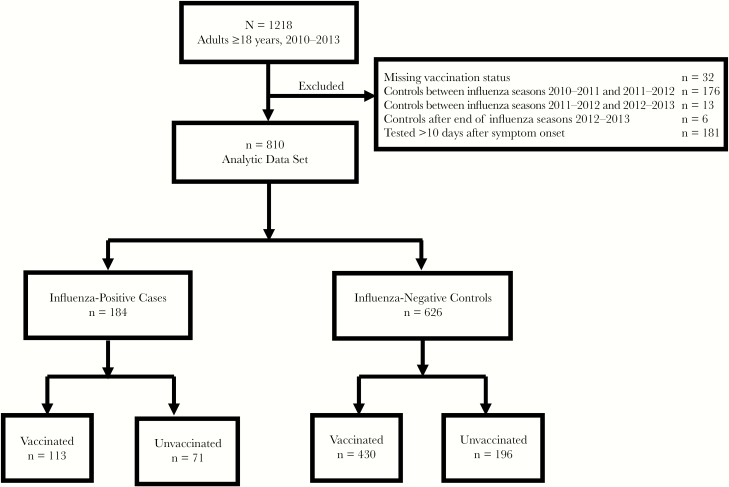

Between 2010 and 2013, staff enrolled 1218 adults aged ≥18 years admitted with LRTI: 242 (20%) in 2010–2011, 493 (41%) in 2011–2012, and 483 (40%) in 2012–2013. After excluding patients for missing influenza vaccination status (n = 32), influenza-negative controls outside the local influenza season (n = 195), and patients whose swab for respiratory virus testing was taken >10 days after symptom onset (n = 181), we had 810 patients in the analytic data set (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study participant flow diagram—Rapid Empiric Treatment with Oseltamivir Study, 2010–2013.

Among 810 patients with LRTI, 509 (63%) were diagnosed with CAP, 223 (28%) with aeCOPD, and 78 (10%) with acute bronchitis. Among those with CAP, 465 (91%) were radiographically confirmed. Overall, 184 (23%) patients tested influenza-positive and were considered cases; 626 (77%) patients tested influenza-negative and were considered controls. The cases included 154 (84%) influenza A virus infections—25 (16%) with A(H1N1)pdm09, 115 (75%) with A(H3N2), and 14 (9%) influenza A that were not subtyped—and 30 (16%) influenza B virus infections.

The median age of cases and controls (interquartile range [IQR]) was 63 (52–75) years and 62 (52–72) years, respectively. Cases were more likely than controls to be female (59% vs 47%; P = .004) and to have never smoked (32% vs 18%; P < .001). Controls were more likely to have a history of COPD than cases (59% vs 48%; P = .01) but otherwise had similar baseline medical conditions as cases (Table 1). In the 90 days before admission, fewer cases than controls were hospitalized for ≥2 days (20% vs 31%; P = .002) (Table 1). In-hospital outcomes, including intensive care unit (ICU) admission, use of invasive mechanical ventilatory support, and in-hospital mortality, were similar between cases and controls. Mean frailty scores were similar in cases and controls (1.2 and 1.3; P = .08).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized With Lower Respiratory Tract Infection, by Influenza Status—Rapid Empiric Treatment With Oseltamivir Study, 2010–2013

| Total | Influenza+ | Influenza- | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 810 | n = 184 | n = 626 | |||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | P Value | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | <.001 | ||||||

| Community-acquired pneumonia, radiographically confirmed | 465 | 57.4 | 79 | 42.9 | 386 | 61.7 | |

| Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 223 | 27.5 | 46 | 25.0 | 177 | 28.3 | |

| Other acute LRTIa | 122 | 15.1 | 59 | 32.1 | 63 | 10.0 | |

| Influenza season | <.001 | ||||||

| 2010–2011 | 155 | 19.1 | 34 | 18.5 | 121 | 19.3 | |

| 2011–2012 | 271 | 33.5 | 22 | 12.0 | 249 | 39.8 | |

| 2012–2013 | 384 | 47.4 | 128 | 69.6 | 256 | 40.9 | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| Overall, median (IQR), y | 62 (52–72) | 63 (52–75) | 62 (52–72) | .36 | |||

| 18–49 y | 162 | 20.0 | 34 | 18.5 | 128 | 19.3 | .81 |

| 50–64 y | 304 | 37.5 | 69 | 37.5 | 235 | 39.8 | |

| ≥65 y | 344 | 42.5 | 81 | 44.0 | 263 | 40.9 | |

| Sex | .004 | ||||||

| Male | 411 | 50.7 | 76 | 41.3 | 335 | 53.5 | |

| Female | 399 | 49.3 | 108 | 58.7 | 291 | 46.5 | |

| BMI | n = 808 | n = 184 | n = 624 | .72 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 41 | 5.1 | 11 | 6.0 | 30 | 4.8 | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 205 | 25.4 | 42 | 22.8 | 163 | 26.1 | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 212 | 26.2 | 54 | 29.4 | 158 | 25.3 | |

| Obesity class 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m2) | 166 | 20.5 | 40 | 21.7 | 126 | 20.2 | |

| Obesity class 2 (35.0–39.9 kg/m2) | 90 | 11.1 | 19 | 10.3 | 71 | 11.4 | |

| Obesity class 3 (≥40 kg/m2) | 94 | 11.6 | 18 | 9.8 | 76 | 12.2 | |

| Social history | |||||||

| Smoking tobacco history | n = 809 | n = 184 | n = 625 | <.001 | |||

| Current | 333 | 41.2 | 62 | 33.7 | 322 | 43.4 | |

| Previous | 304 | 37.6 | 63 | 34.2 | 271 | 38.6 | |

| Never | 172 | 21.3 | 59 | 32.1 | 241 | 18.1 | |

| Current nursing home resident | 40 | 5.0 | 7 | 3.8 | 33 | 5.3 | .42 |

| Medical historyb | |||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 242 | 29.9 | 52 | 28.3 | 190 | 30.4 | .59 |

| Essential arterial hypertension | 576 | 71.1 | 131 | 71.2 | 445 | 71.1 | .98 |

| Congestive heart failure | 229 | 28.3 | 42 | 22.8 | 187 | 29.9 | .06 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 80 | 9.9 | 24 | 13.0 | 56 | 9.0 | .10 |

| HIVc | 14 | 1.7 | 3 | 1.6 | 11 | 1.8 | .91 |

| Cancer | 89 | 11.0 | 19 | 10.3 | 70 | 11.2 | .74 |

| Hepatic diseased | 49 | 6.1 | 8 | 4.4 | 41 | 6.6 | .27 |

| Renal diseasee | 160 | 19.8 | 38 | 20.7 | 122 | 19.5 | .73 |

| COPD | 457 | 56.4 | 89 | 48.4 | 368 | 58.8 | .01 |

| Home oxygen use | 181 | 22.4 | 34 | 18.5 | 147 | 23.5 | .15 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 308 | 38.0 | 71 | 38.6 | 237 | 37.9 | .86 |

| Previous hospitalizations | |||||||

| Hospitalized ≥2 d in the prior 90 d | 232 | 28.6 | 36 | 19.6 | 196 | 31.3 | .002 |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||||||

| Length of stay, median (IQR), d | 4 (3–7) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–7) | .06 | |||

| Intensive care unit admission | 133 | 16.4 | 23 | 12.5 | 110 | 17.6 | .10 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 28 | 3.5 | 8 | 4.4 | 20 | 3.2 | .45 |

| In-hospital mortality | 23 | 2.8 | 7 | 3.8 | 16 | 2.6 | .37 |

| Influenza vaccine for corresponding season | 543 | 67.0 | 113 | 61.4 | 430 | 68.7 | .07 |

| Oseltamivir use during hospitalization | 444 | 54.8 | 145 | 78.8 | 299 | 47.8 | <.001 |

| Mean frailty score (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.2) | 1.3 (1.0–1.3) | .08 | |||

Percentages are listed as column percentages.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection.

aIncludes diagnoses of acute bronchitis and clinically diagnosed CAP.

bPatients may have >1 condition.

cAmong enrollees with a history of HIV, 10 (1.2%) were on highly active antiretroviral therapy.

dAmong enrollees with liver disease, 9 (1.1%) had a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

eAmong enrollees with renal disease, 117 (14.4%) had a diagnosis of renal failure and 18 (2.2%) had chronic renal dialysis within the prior 30 days.

A total of 543 (67%) patients self-reported receiving influenza vaccination for the corresponding season (Table 2). Compared with unvaccinated patients, vaccinated patients were older (median age, 65 vs 56 years; P < .001) and were more likely to have a history of coronary artery disease (35% vs 19%; P < .001), essential arterial hypertension (76% vs 61%; P < .001), congestive heart failure (32% vs 21%; P = .002), renal disease (23% vs 13%; P < .001), history of COPD (61% vs 48%; P < .001), home oxygen use (27% vs 12%; P < .001), and diabetes mellitus (42% vs 31%; P = .003). Vaccinated patients were more likely to have been hospitalized for ≥2 days in the 90 days before admission compared with unvaccinated patients (34% vs 18%; P < .001). Vaccination status did not significantly differ by in-hospital outcomes or mean frailty score.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients Hospitalized With Lower Respiratory Tract Infection, by Influenza Vaccine Status—Rapid Empiric Treatment With Oseltamivir Study, 2010–2013

| Total (n = 810) | Vaccinated (n = 543) | Unvaccinated (n = 267) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | P Value | |

| Lower respiratory tract infection | .84 | ||||||

| Community-acquired pneumonia, radiographically confirmed | 465 | 57.4 | 306 | 56.4 | 159 | 59.6 | |

| Acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 223 | 27.5 | 153 | 28.2 | 70 | 26.2 | |

| Other acute LRTIa | 122 | 15.1 | 84 | 15.4 | 38 | 14.2 | |

| Influenza season | .06 | ||||||

| 2010–2011 | 155 | 19.1 | 100 | 18.4 | 55 | 20.6 | |

| 2011–2012 | 271 | 33.5 | 170 | 31.3 | 101 | 37.8 | |

| 2012–2013 | 384 | 47.4 | 273 | 50.3 | 111 | 41.6 | |

| Age groups | |||||||

| Overall, median (IQR), y | 62 (52–72) | 65 (55–75) | 56 (48–64) | <.001 | |||

| 18–49 y | 162 | 20.0 | 88 | 16.2 | 74 | 27.7 | <.001 |

| 50–64 y | 304 | 37.5 | 177 | 32.6 | 127 | 47.6 | |

| ≥65 y | 344 | 42.5 | 278 | 51.2 | 66 | 24.7 | |

| Sex | .83 | ||||||

| Male | 411 | 50.7 | 277 | 51.0 | 134 | 50.2 | |

| Female | 399 | 49.3 | 266 | 49.0 | 133 | 49.8 | |

| BMI | n = 809 | n = 542 | n = 266 | .54 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 41 | 5.1 | 29 | 5.4 | 12 | 4.5 | |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 205 | 25.4 | 143 | 26.4 | 62 | 23.3 | |

| Overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) | 212 | 26.2 | 142 | 26.2 | 70 | 26.3 | |

| Obesity class 1 (30.0–34.9 kg/m2) | 166 | 20.5 | 112 | 20.7 | 54 | 20.3 | |

| Obesity class 2 (35.0–39.9 kg/m2) | 90 | 11.1 | 61 | 11.3 | 29 | 10.9 | |

| Obesity class 3 (≥40 kg/m2) | 94 | 11.6 | 55 | 10.2 | 39 | 14.7 | |

| Social history | |||||||

| Smoking tobacco history | n = 809 | n = 543 | n = 266 | <.001 | |||

| Current | 333 | 41.2 | 195 | 35.9 | 138 | 51.9 | |

| Previous | 304 | 37.6 | 232 | 42.7 | 72 | 27.1 | |

| Never | 172 | 21.3 | 116 | 21.4 | 56 | 21.1 | |

| Current nursing home resident | 40 | 4.9 | 30 | 5.5 | 10 | 3.8 | .27 |

| Medical historyb | |||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 242 | 29.9 | 191 | 35.2 | 51 | 19.1 | <.001 |

| Essential arterial hypertension | 576 | 71.1 | 412 | 75.9 | 164 | 61.4 | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 229 | 28.3 | 172 | 31.7 | 57 | 21.4 | .002 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 80 | 9.9 | 60 | 11.1 | 20 | 7.5 | .11 |

| HIVc | 14 | 1.7 | 9 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.9 | .83 |

| Cancer | 89 | 11.0 | 65 | 12.0 | 24 | 9.0 | .20 |

| Hepatic diseased | 49 | 6.1 | 28 | 5.2 | 21 | 7.9 | .13 |

| Renal diseasee | 160 | 19.8 | 125 | 23.0 | 35 | 13.1 | <.001 |

| COPD | 457 | 56.4 | 329 | 60.6 | 128 | 47.9 | <.001 |

| Home oxygen use | 181 | 22.4 | 148 | 27.3 | 33 | 12.4 | <.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 308 | 38.0 | 226 | 41.6 | 82 | 30.7 | .003 |

| Previous hospitalizations | |||||||

| Hospitalized ≥2 d in the prior 90 d | 232 | 28.6 | 184 | 33.9 | 48 | 18.0 | <.001 |

| In-hospital outcomes | |||||||

| Length of stay, median (IQR), y | 4 (3–7) | 4 (3–7) | 4 (3–6) | .02 | |||

| Intensive care unit admission | 133 | 16.4 | 88 | 16.2 | 45 | 16.9 | .82 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 28 | 3.5 | 19 | 3.5 | 9 | 3.4 | .93 |

| In-hospital mortality | 23 | 2.8 | 18 | 3.3 | 5 | 1.9 | .25 |

| Influenza positive tests | 184 | 22.7 | 113 | 20.8 | 71 | 26.6 | .07 |

| Oseltamivir use during hospitalization | 444 | 54.8 | 291 | 53.6 | 153 | 57.3 | .32 |

| Mean frailty score (IQR) | 1.3 (1.0–1.3) | 1.3 (1.0–1.3) | 1.2 (1.0–1.2) | .001 | |||

Percentages are listed as column percentages.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection.

aIncludes diagnoses of acute bronchitis and clinically diagnosed CAP.

bPatients may have >1 condition.

cAmong enrollees with a history of HIV, 10 (1.2%) were on highly active antiretroviral therapy.

dAmong enrollees with hepatic disease, 9 (1.1%) had a diagnosis of cirrhosis.

eAmong enrollees with renal disease, 117 (14.4%) had a diagnosis of renal failure and 18 (2.2%) had chronic renal dialysis within the prior 30 days.

All patients in the study received a chest x-ray, and 231 (29%) received a chest CT scan within 48 hours of admission (Supplementary Table 1). Among 509 patients with a diagnosis of CAP, 424 (83%) had radiographic evidence of new infiltrate by chest x-ray alone, while 465 (91%) had radiographic findings of new infiltrate by chest x-ray or chest CT reviewed by a physician. In our study population, 58% of patients had chronic lung disease based on history of COPD or home use of oxygen. Comparing patients with chronic lung disease with those without, patients with chronic lung disease were older, had higher mean frailty scores, and were more likely to have used tobacco, to have a history of heart disease or diabetes, and to self-report having received influenza vaccination (Supplementary Table 2). These findings were similar among patients diagnosed with radiographically confirmed CAP alone (Supplementary Table 3).

Vaccine Effectiveness Against Influenza-Associated Pneumonia and Other Acute LRTIs

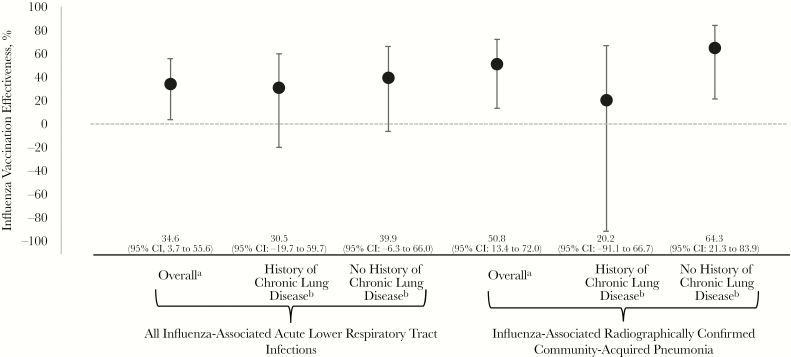

Pooled across the 2010–2013 influenza seasons, adjusted VE was 35% (95% CI, 4% to 56%) against acute influenza-associated LRTI, 51% (95% CI, 13% to 72%) against radiographically confirmed influenza-associated CAP, and 48% (95% CI, –10% to 76%) against influenza-associated aeCOPD (Figure 2). In exploratory subgroup analysis, VE against any acute influenza-associated LRTI did not significantly differ (interaction P = .6) among those with (31%; 95% CI, –20% to 60%) and without chronic lung disease (40%; 95% CI, –6% to 66%). VE against radiographically confirmed influenza-associated CAP was 20% (95% CI, –91% to 67%) in patients with chronic lung disease compared with 64% (95% CI, 21% to 84%) in those without (interaction P = .4).

Figure 2.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness against hospitalized influenza-associated acute lower respiratory tract infections in adults—Rapid Empiric Treatment with Oseltamivir Study, 2010–2013. aControlling for age, sex, season, seasonal tertile by admission date, chronic lung disease (history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or home oxygen use), mean frailty score, and hospitalization for 2 or more days in the last 90 days. bControlling for age, sex, season, seasonal tertile by admission date, mean frailty score, and hospitalization for 2 or more days in the last 90 days.

As most influenza was related to influenza A(H3N2) viruses in the study, we explored VE against influenza A(H3N2) virus infections. VE was 26% (95% CI, –19% to 54%) against any acute LRTI and 27% (95% CI, –46% to 64%) against radiographically confirmed CAP associated with influenza A(H3N2) viruses. In patients without chronic lung disease, influenza vaccination reduced the risk of hospitalization with radiographically confirmed A(H3N2)–associated CAP by 62% (95% CI, 7% to 85%). There were insufficient cases by subtype to estimate VE for influenza A(H3N2) in patients with chronic lung disease or for infections specific to influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and B-lineage viruses.

DISCUSSION

In this multihospital study of adult patients with severe influenza complications, we found that the odds of influenza vaccination were significantly lower in patients with influenza virus infection than those without, including hospitalizations related to acute lower respiratory tract infection, radiographically confirmed pneumonia, and acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive lung disease. Influenza vaccination during the current season was 35% effective against influenza-associated LRTI and 51% effective against influenza-associated, radiologically confirmed CAP. These findings suggest that influenza vaccination could reduce the occurrence of severe influenza-associated respiratory complications, which are among the most common diagnoses of hospitalized patients [5]. CAP alone contributes to >1.5 million hospitalizations and 100 000 in-hospital deaths in adult patients in the United States annually [4]. During the influenza season, some of these cases may be due to influenza virus infection, an important vaccine-preventable infection [5, 25].

Although there have been limited studies to date estimating VE against influenza-associated CAP, our findings are similar to 2 prior studies using a test-negative VE study design demonstrating a nonsignificant 42% reduction among hospitalized adults [26] and a significant 58% reduction in elderly patients aged ≥65 years [27]. The test-negative VE study design can present challenges in assessing the impact of influenza vaccination in CAP and may be 1 explanation for why varying results are reported. Influenza virus infection can lead to different presentations of pneumonia, including primary viral pneumonia and secondary bacterial pneumonia or pulmonary superinfections related to other infectious organisms [25, 28], some of which may occur after influenza viral shedding ends [29]. In an observational test-negative design, only patients with primary influenza viral pneumonia would be considered cases, while secondary bacterial pneumonia or other pulmonary infections that occur after influenza viral shedding has stopped would be considered influenza-negative controls, leading to outcome misclassification. Studies of VE against the different presentations of influenza-associated pneumonia, with attempts to classify whether pneumonia was associated with ongoing or recent influenza virus infection, could provide a better understanding of the complete benefits of influenza vaccination.

Vaccination coverage in the United States is estimated to be between 34% and 68% in adults, varying by age group [30], despite universal recommendation for annual influenza vaccination for people older than 6 months [8]. Among the most common reasons cited for influenza vaccine hesitancy are concerns about effectiveness [31], suggesting that tailored messaging of the preventative effects of vaccination against severe influenza-associated complications could have meaningful public health benefits. Acute LRTIs encompass a variety of respiratory diagnoses affecting a heterogeneous group of patients. Although our study found that influenza vaccination reduced the odds of influenza-associated LRTI by 35%, VE point estimates against specific complications such as CAP were higher. Our findings suggest that influenza vaccination may have varying effects on different subgroups of patients.

The stratified analysis of LRTI by chronic lung disease revealed higher VE point estimates in patients without underlying lung disease, although this difference was not statistically significant. This result could be due to chance or could be indicative of a biological effect or residual confounding arising from differences between people with and without chronic lung disease. Patients with underlying lung disease may have impaired immune responses to both influenza virus infection and vaccination. Impaired humoral and cellular responses in those with COPD compared with those without [32, 33] may lower the protective effects of influenza vaccination and increase the susceptibility of these patients to influenza virus infection. Furthermore, patients with COPD may be at higher risk for infection because of defects in natural airway defenses [34, 35], underlying immune changes [36], or chronic inflammation [34]. Other associated characteristics such as age or immunosuppression from chronic steroid use could further impair the immune response. However, this study was underpowered to detect true differences between these subgroups, and our findings are meant to be exploratory. Nonetheless, these results suggest that influenza VE may be modified by a history of COPD, an interplay that could be explored in future studies.

We also attempted to highlight the benefits of influenza vaccination in reducing risk of influenza-associated hospitalizations for aeCOPD. COPD and its associated complications are leading causes of disability and mortality [37, 38] with major public health implications in the United States [39, 40]. Promoting the benefits of annual influenza vaccination in those most at risk for these complications may lead to meaningful disease-related health care cost reduction. Influenza is an important viral etiology of aeCOPD during the influenza season [41]. Findings from systematic literature reviews suggest that influenza vaccination can reduce the total number of COPD exacerbations [42, 43] while other studies have found that vaccination reduced the risk of influenza-associated hospitalizations in those with underlying COPD [44, 45]. Although COPD-specific VE estimates in this study were not statistically significant, it is likely that this assessment was limited by a small sample size. Additional studies focusing on this specific outcome could provide a better understanding of VE against influenza-associated aeCOPD.

Limitations

This study has limitations to consider. We conducted a secondary analysis of VE nested in a previously conducted trial in which vaccination status was defined by patient self-report. While self-reported vaccination has been a reasonable indicator of vaccination status in a variety of settings [10, 46, 47], misclassification of vaccine status in this study could exist and may have biased VE estimates toward the null [48–50]. Furthermore, we were unable to verify the date of influenza vaccination and unable to exclude patients vaccinated <2 weeks before hospital admission, who were likely unprotected by the vaccination at the time of their hospitalization. This study did not collect information on pneumococcal vaccination, which may lower the risk of influenza-associated bacterial pneumonia [51]. Our study also relied upon nasopharyngeal testing of influenza to identify cases of infection; however, patients who develop LRTI later in the course of infection may require lower respiratory tract samples to confirm influenza virus infection [52]. We were not able to account for confounding related to chronic steroid treatment among those with underlying COPD or other lung diseases. Steroid treatment may modify both the effect of the vaccine and the severity of influenza virus infection. Lastly, because of sample size limitations, we calculated a pooled VE estimate across several influenza seasons, which masks potentially important heterogeneity among seasons.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study of severe influenza-associated respiratory complications, the odds of influenza vaccination were lower in those with influenza virus infection than those without. VE studies including analyses of patients with different underlying conditions could further improve our understanding of the impact of influenza vaccination. These results could be helpful in achieving higher rates of vaccination by citing its benefits against severe complications of influenza and reducing the morbidity and mortality of influenza.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the RETOS team at the University of Louisville for their contributions to the study.

Financial support. The analysis and manuscript preparation were completed as part of official duties at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclaimer. The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Ferdinands reports nonfinancial support from the Institute for Influenza Epidemiology (funded in part by Sanofi Pasteur) outside the submitted work. The authors report no other disclosures. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease burden of influenza Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. Accessed 20 December 2019.

- 2. Collaborators GBDLRI. Estimates of the global, regional, and national morbidity, mortality, and aetiologies of lower respiratory infections in 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:1191–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Malosh RE, Martin ET, Ortiz JR, Monto AS. The risk of lower respiratory tract infection following influenza virus infection: a systematic and narrative review. Vaccine 2018; 36:141–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, et al. Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1806–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reed C, Chaves SS, Perez A, et al. Complications among adults hospitalized with influenza: a comparison of seasonal influenza and the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59:166–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fleming-Dutra KE, Taylor T, Link-Gelles R, et al. Effect of the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic on invasive pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis 2013; 207:1135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. Deaths: final data for 2017. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019; 68:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grohskopf LA, Sokolow LZ, Broder KR, Walter EB, Fry AM, Jernigan DB. Prevention and control of seasonal influenza with vaccines: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2018–19 influenza season. MMWR Recomm Rep 2018; 67:1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Past seasons burden averted estimates Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines-work/past-burden-averted-est.html. Accessed 20 December 2019.

- 10. Ferdinands JM, Gaglani M, Martin ET, et al. Prevention of influenza hospitalization among adults in the US, 2015–16: results from the US Hospitalized Adult Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness Network (HAIVEN). J Infect Dis 2019; 220(8):1265–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jackson ML, Nelson JC, Weiss NS, et al. Influenza vaccination and risk of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent elderly people: a population-based, nested case-control study. Lancet 2008; 372:398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nichol KL, Nordin JD, Nelson DB, et al. Effectiveness of influenza vaccine in the community-dwelling elderly. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:1373–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mangtani P, Cumberland P, Hodgson CR, et al. A cohort study of the effectiveness of influenza vaccine in older people, performed using the United Kingdom general practice research database. J Infect Dis 2004; 190:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nordin J, Mullooly J, Poblete S, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalizations and deaths in persons 65 years or older in Minnesota, New York, and Oregon: data from 3 health plans. J Infect Dis 2001; 184:665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster DA, Talsma A, Furumoto-Dawson A, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalization for pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 1992; 136:296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferdinands JM, Gargiullo P, Haber M, et al. Inactivated influenza vaccines for prevention of community-acquired pneumonia: the limits of using nonspecific outcomes in vaccine effectiveness studies. Epidemiology 2013; 24:530–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Belongia EA, Shay DK. Influenza vaccine for community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2008; 372:352–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramirez J, Peyrani P, Wiemken T, et al. A randomized study evaluating the effectiveness of oseltamivir initiated at the time of hospital admission in adults hospitalized with influenza-associated lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Infect Dis 2018; 67:736–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. ; Infectious Diseases Society of America ; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44(Suppl 2):S27–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187:347–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gonzales R, Sande MA. Uncomplicated acute bronchitis. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133:981–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mahony J, Chong S, Merante F, et al. Development of a respiratory virus panel test for detection of twenty human respiratory viruses by use of multiplex PCR and a fluid microbead-based assay. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:2965–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Prina E, Ranzani OT, Torres A. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet 2015; 386:1097–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jackson ML, Nelson JC. The test-negative design for estimating influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccine 2013; 31:2165–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Musher DM, Thorner AR. Community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2014; 371:1619–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Grijalva CG, Zhu Y, Williams DJ, et al. Association between hospitalization with community-acquired laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia and prior receipt of influenza vaccination. JAMA 2015; 314:1488–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Suzuki M, Katsurada N, Le MN, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated influenza vaccine against laboratory-confirmed influenza pneumonia among adults aged ≥65 years in Japan. Vaccine 2018; 36:2960–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rothberg MB, Haessler SD. Complications of seasonal and pandemic influenza. Crit Care Med 2010; 38:e91–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rothberg MB, Haessler SD, Brown RB. Complications of viral influenza. Am J Med 2008; 121:258–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Flu vaccination coverage, United States, 2018–19 influenza season Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/coverage-1819estimates.htm. Accessed 22 January.

- 31. Schmid P, Rauber D, Betsch C, Lidolt G, Denker ML. Barriers of influenza vaccination intention and behavior - a systematic review of influenza vaccine hesitancy, 2005 - 2016. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0170550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Parpaleix A, Boyer L, Wiedemann A, et al. Impaired humoral and cellular immune responses to influenza vaccination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 140:1754–7 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nath KD, Burel JG, Shankar V, et al. Clinical factors associated with the humoral immune response to influenza vaccination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 9:51–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sanei F, Wilkinson T. Influenza vaccination for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: understanding immunogenicity, efficacy and effectiveness. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2016; 10:349–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sajjan US. Susceptibility to viral infections in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: role of epithelial cells. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2013; 19:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hsu AC, Starkey MR, Hanish I, et al. Targeting PI3K-p110α suppresses influenza virus infection in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 191:1012–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sullivan J, Pravosud V, Mannino DM, Siegel K, Choate R, Sullivan T. National and state estimates of COPD morbidity and mortality - United States, 2014–2015. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2018; 5:324–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McGrath R, Al Snih S, Markides K, et al. The burden of health conditions for middle-aged and older adults in the United States: disability-adjusted life years. BMC Geriatr 2019; 19:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jinjuvadia C, Jinjuvadia R, Mandapakala C, Durairajan N, Liangpunsakul S, Soubani AO. Trends in outcomes, financial burden, and mortality for acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the United States from 2002 to 2010. COPD 2017; 14:72–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Patel JG, Nagar SP, Dalal AA. Indirect costs in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review of the economic burden on employers and individuals in the United States. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2014; 9:289–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mohan A, Chandra S, Agarwal D, et al. Prevalence of viral infection detected by PCR and RT-PCR in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD: a systematic review. Respirology 2010; 15:536–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kopsaftis Z, Wood-Baker R, Poole P. Influenza vaccine for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 6:CD002733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bekkat-Berkani R, Wilkinson T, Buchy P, et al. Seasonal influenza vaccination in patients with COPD: a systematic literature review. BMC Pulm Med 2017; 17:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mulpuru S, Li L, Ye L, et al. ; Serious Outcomes Surveillance (SOS) Network of the Canadian Immunization Research Network (CIRN) Effectiveness of influenza vaccination on hospitalizations and risk factors for severe outcomes in hospitalized patients with COPD. Chest 2019; 155:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gershon AS, Chung H, Porter J, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing hospitalizations in older patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Infect Dis 2020; 221:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Irving SA, Donahue JG, Shay DK, et al. Evaluation of self-reported and registry-based influenza vaccination status in a Wisconsin cohort. Vaccine 2009; 27:6546–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. King JP, McLean HQ, Belongia EA. Validation of self-reported influenza vaccination in the current and prior season. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2018; 12:808–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mac Donald R, Baken L, Nelson A, Nichol KL. Validation of self-report of influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status in elderly outpatients. Am J Prev Med 1999; 16:173–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Skull SA, Andrews RM, Byrnes GB, et al. Validity of self-reported influenza and pneumococcal vaccination status among a cohort of hospitalized elderly inpatients. Vaccine 2007; 25:4775–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zimmerman RK, Raymund M, Janosky JE, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of patient self-report of influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccinations among elderly outpatients in diverse patient care strata. Vaccine 2003; 21:1486–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang YY, Tang XF, Du CH, et al. Comparison of dual influenza and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination with influenza vaccination alone for preventing pneumonia and reducing mortality among the elderly: a meta-analysis. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12:3056–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chow EJ, Doyle JD, Uyeki TM. Influenza virus-related critical illness: prevention, diagnosis, treatment. Crit Care 2019; 23:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.