Abstract

Background

In women with congenital heart defects (CHD), changes in blood volume, heart rate, respiration, and edema during pregnancy may lead to increased risk of adverse outcomes and conditions. The American Heart Association (AHA) recommends providers of pregnant women with CHD assess cardiac health and discuss risks and benefits of cardiac-related medications. We described receipt of AHA-recommended cardiac evaluations, filled potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic (Food and Drug Administration pregnancy category D/X) cardiac-related prescriptions, and adverse conditions among pregnant women with CHD compared to those without CHD.

Methods and Results

Using 2007–2014 U.S. healthcare claims data, we ascertained a retrospective cohort of women with and without CHD ages 15–44 years with private insurance covering prescriptions during pregnancy. CHD was defined as ≥1 inpatient code or ≥2 outpatient CHD diagnosis codes >30 days apart documented outside of pregnancy and categorized as severe or non-severe. Log-linear regression, accounting for multiple pregnancies per woman, generated adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) for associations between presence/severity of CHD and stillbirth, preterm birth, and adverse conditions from last menstrual period (LMP) to 90 days postpartum. We identified 2,056 women with CHD (2,334 pregnancies) and 1,374,982 women without (1,524,077 pregnancies). During LMP to 90 days postpartum, 56% of women with CHD had comprehensive echocardiograms and, during pregnancy, 4% filled potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac-related prescriptions. Women with CHD, compared to those without, experienced more adverse conditions overall (aPR=1.9, 95% CI:1.7–2.1) and, specifically, obstetric (aPR=1.3, 95% CI:1.2–1.4) and cardiac conditions (aPR=10.2, 95% CI:9.1–11.4); stillbirth (aPR=1.6, 95% CI:1.1–2.4); and preterm delivery (aPR=1.6, 95% CI:1.4–1.8). More women with severe CHD, compared to non-severe, experienced adverse conditions overall (aPR=1.5, 95% CI:1.2–1.9).

Conclusions

Women with CHD have elevated prevalence of adverse cardiac and obstetric conditions during pregnancy, 4 in 100 used potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic medications, and only half received an AHA-recommended comprehensive echocardiogram.

Due to improvements in survival, approximately 1.4 million U.S. adults are living with congenital heart defects (CHD).1, 2 With more U.S. women with CHD reaching reproductive age, their delivery hospitalizations increased by 35% from 1997–2007.3,4 However, pregnancy intensifies the physiological demands on the heart. In women with CHD, increases in blood volume, edema, increased heart rate, and respiratory changes during pregnancy may increase the risk of adverse experiences,5, 6 including heart failure, cerebrovascular events, and preterm delivery, compared to women without CHD.5, 7–10 Therefore, the American Heart Association (AHA), American College of Cardiology (ACC), and American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) recommend providers assess cardiac health of pregnant women with CHD, including performing a comprehensive echocardiogram and reviewing benefits and risks of cardiac-related medications.11, 12

Several hospital-based studies described incidence of adverse pregnancy conditions among women with heart disease, but findings combine congenital and acquired heart disease, lack a comparison group without CHD, are not stratified by CHD severity, and may not be generalizable outside those center(s) specializing in cardiac care.13–16 A few studies using national inpatient data have compared women with CHD to those without, but only describe adverse conditions recorded at delivery hospitalization, likely missing information on conditions occurring before or after delivery.7–10, 17 Therefore, using healthcare claims data from a large, convenience sample of privately-insured individuals, we compared the prevalence of adverse conditions, pregnancy outcomes, receipt of cardiac care, and potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic (Food and Drug Administration pregnancy category D or X) cardiac-related prescriptions filled among pregnant women with CHD compared to those without CHD.

METHODS

The IBM Marketscan® Commercial Database provides individual-level healthcare claims data including enrollment, inpatient and outpatient medical, pharmaceutical, and limited sociodemographic (age, sex, U.S. Census region of residence) data on a large, convenience sample of about 50 million individuals with employer-sponsored insurance and their dependents per year. Using 2007–2014 data from the IBM MarketScan® Commercial Database, we identified privately-insured women ages 15–44 years with and without CHD who had ≥1 pregnancy lasting >20 weeks gestation and had prescription drug coverage. Women could contribute more than one pregnancy to the sample. Pregnancies were excluded if the woman was not continuously enrolled (i.e. missing >30 days of enrollment from LMP to 90 days postpartum). The authors cannot make data and study materials available to other investigators for purposes of reproducing the results because of licensing restrictions. Interested parties, however, could obtain and license the data by contacting Truven Health Analytics Inc.

CHD algorithm

Women with CHD were ascertained using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes from inpatient admission and outpatient service claims. Similarly to other studies, CHD was defined as ≥2 outpatient CHD ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes separated by >30 days or ≥1 inpatient CHD ICD-9-CM diagnosis code documented anytime between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2014.18–22 The positive predictive value of singular outpatient CHD coding in administrative data can be as low as 50%, so women with only one outpatient CHD were excluded.23 CHD was categorized as severe or non-severe based on a published algorithm integrating hemodynamic severity and basic anatomy.24 Because CHD is present at birth and a lifelong condition, women were classified as having CHD regardless of whether the diagnoses were coded before, during, or after pregnancy; however, to prevent misclassification of fetal CHD as maternal CHD,23 we required that CHD ICD-9-CM codes be documented before the 15th week of pregnancy or after 90 days postpartum. Our comparison group had no CHD codes between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2014. Because Down syndrome is associated with CHD and women with CHD and Down syndrome have greater risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes than those without Down syndrome, we excluded women with ≥1 Down syndrome diagnosis code at any time between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2014.25

Pregnancy algorithm

We implemented a published algorithm that uses pregnancy-related procedure and diagnostic codes indicating end of a pregnancy to assign birth outcome, estimate gestational age at end of pregnancy, and used estimated gestational age to calculate date of LMP.26 Multiple births were included, but, due to the limitations of claims data, we could not distinguish a multiple birth from a singleton birth unless the birth outcomes differed between the multiples (e.g. combination of live birth(s) and stillbirth(s)). Pregnancies occurring between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2013, including pregnancies conceived in 2007 and ending in 2008 or conceived in 2013 and ending in 2014, were included in the analytic sample.

Obstetric, cardiac, and other conditions

We compiled a list of severe obstetric, cardiac and other conditions, which may be related to or result from CHD and can contribute to significant morbidity during pregnancy (Supplemental Table 1). We included 12 obstetric conditions such as gestational diabetes, hemorrhage, obstetric shock, and placental abruption; 7 cardiac conditions (defined as conditions that specifically relate to heart function or heart rhythm) such as atrial fibrillation, cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and myocardial infarction; and 12 other conditions such as acute renal failure, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary edema, and stroke. These conditions were identified for inclusion based on previous literature and clinician input (MG and NT). Conditions were identified by ICD-9-CM diagnostic codes and ICD-9-CM or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) procedure or Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes from LMP to 90 days postpartum per pregnancy; we did not assess whether the condition was first diagnosed during pregnancy. Similar to another study, for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, we required ≥1 inpatient diagnosis code or ≥1 anticoagulation outpatient prescription claim documented within 90 days of an outpatient diagnosis code.27 All other conditions, except CHD, were identified by ≥1 procedure or inpatient diagnosis code or ≥2 outpatient diagnosis codes separated by ≥1 day. Women with a diabetes diagnosis from 2007–2014 prior to a gestational diabetes code were not classified as having gestational diabetes; otherwise, the same algorithm applied despite other diabetes diagnoses.

Analyses

Descriptive and chi-square statistics were assessed for characteristics at delivery including maternal age group (15–19, 20–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, or 40–44 years), U.S. Census region of residence (Northeast, North Central, South, West, or missing), and year of delivery (2008–09, 2010–11, or 2012–14); obstetric, cardiac and other adverse conditions, individually, as well as cumulative number (0, 1 or ≥2); birth outcomes (live birth or stillbirth; multiple births identified as live birth and stillbirth contributed to both categories); and among live births, delivery by cesarean section (identified by ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes of 669.7X or ICD-9-CM procedure codes 74.0–74.2, 74.4, 74.99 or CPT codes 59514, 59620 within 14 days of estimated delivery date) and estimated gestational age at birth (preterm or full term; <37 weeks and ≥37 weeks based on diagnosis and procedure codes, respectively26). We assessed whether there was a documented comprehensive echocardiogram during pregnancy (CPT codes 93303, 93304, 93306, 93307, 93308). We additionally assessed whether women filled an outpatient prescription from LMP to end of pregnancy or date of delivery for potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac medications (defined as Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category D or X; listed in Supplemental Table 2).

We used the generalized estimating equation approach to log-linear regression with exchangeable correlation structure to account for clustering of multiple pregnancies per woman. We calculated adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all outcomes comparing pregnancies among 1) women with CHD (severe or non-severe) to those without CHD; 2) women with non-severe CHD to those without CHD; and 3) women with severe CHD to non-severe CHD. Estimates were adjusted for age, region, and year of delivery. Frequencies were provided for cells with >5 observations.

To account for cumulative effects of multiple pregnancies, we performed a sensitivity analysis limiting results to the woman’s first pregnancy in the study period. We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding women whose only CHD claims were ostium secundum type atrial septal defects (ASD) (ICD-9-CM 745.5), a diagnosis code with low specificity.28, 29

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4. Data are de-identified, administrative data and not considered human subjects research by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

RESULTS

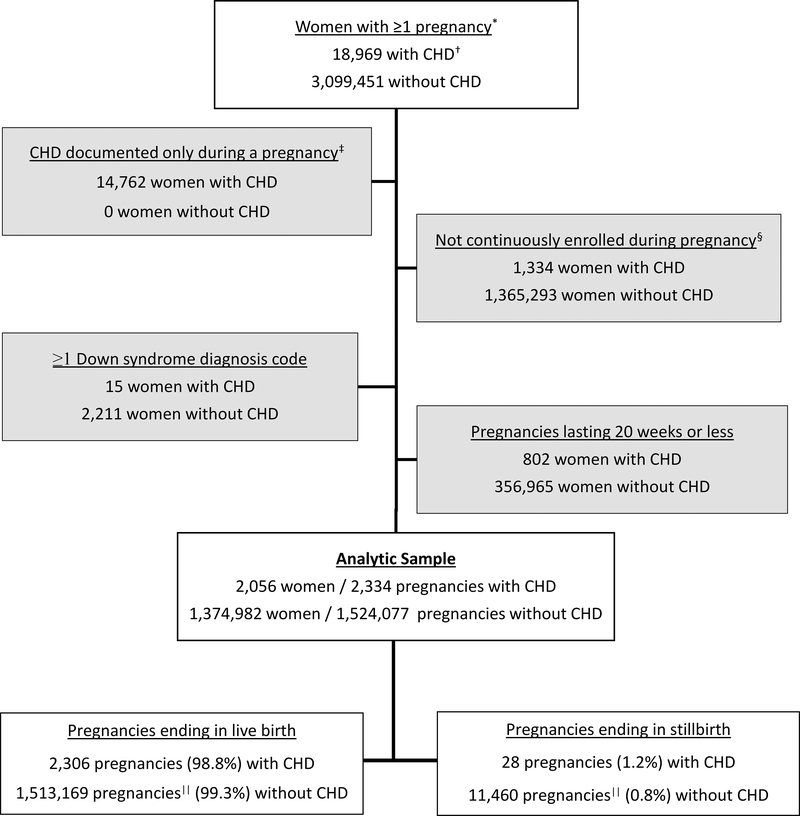

Between 2007 and 2014, there were 18,969 pregnant women with ≥1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient CHD claims separated by >30 days and 3,099,451 pregnant women without CHD claims. After implementing inclusion and exclusion criteria, there were 2,056 women with CHD claims contributing 2,334 pregnancies and 1,374,982 women without CHD claims contributing 1,524,077 pregnancies (Figure 1). About 12.6% of women with CHD and 10.2% of women without CHD contributed more than one pregnancy to the analysis.

Figure 1. Exclusion criteria and final sample of pregnant women with and without congenital heart defects (CHD), IBM Watson Health MarketScan® Commercial Database, 2007–2014.

*Pregnancies occurring between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2013, including pregnancies conceived in 2007 and ending in 2008 or conceived in 2013 and ending in 2014. †1 inpatient or ≥2 outpatient CHD diagnosis claims ≥ 30 days apart. ‡15 weeks gestation through 90 days postpartum. §Missing >30 days. ||Includes 552 that were live birth and still birth.

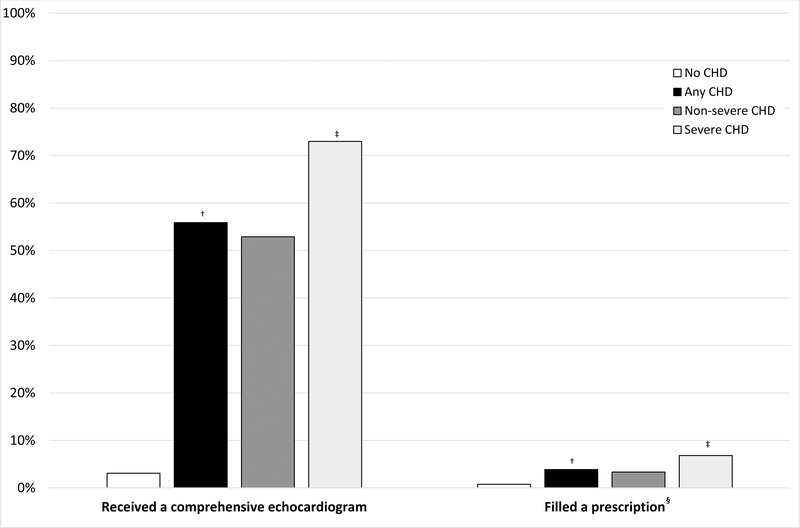

Distributions of age, region, and year at delivery were similar among women with and without CHD (Table 1). Only 1.2% of women included in the analysis were missing region of residence at delivery. Overall, 55.9% of women with CHD had a comprehensive echocardiogram during pregnancy, with a higher prevalence among pregnancies in women with severe (73.0%) compared to non-severe (52.9%) CHD (Figure 2). Overall, 4.0% of women with CHD filled a prescription for ≥1 potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac medication during pregnancy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnancies* among privately-insured women aged 15–44 with and without congenital heart defects (CHD), 2007–2014

| No CHD (n=1,524,077) | CHD | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (n=2,334) | Severe (n=352) | Non-severe (n=1,982) | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age at delivery (years)† | ||||||||

| 15–19 | 53,682 | 3.5 | 116 | 5.0 | 14 | 4.0 | 102 | 5.2 |

| 20–24 | 178,490 | 11.7 | 293 | 12.6 | 62 | 17.6 | 231 | 11.7 |

| 25–29 | 433,806 | 28.5 | 603 | 25.8 | 106 | 30.1 | 497 | 25.1 |

| 30–34 | 533,012 | 35.0 | 800 | 34.2 | 115 | 32.7 | 685 | 34.6 |

| 35–39 | 267,000 | 17.5 | 412 | 17.7 | 47 | 13.4 | 365 | 18.4 |

| 40–44 | 58,087 | 3.8 | 110 | 4.7 | 8 | 2.3 | 102 | 5.2 |

| Region of residence at delivery‡ | ||||||||

| Northeast | 207,706 | 13.6 | 357 | 15.3 | 68 | 19.3 | 289 | 14.6 |

| North Central | 379,289 | 24.9 | 605 | 25.9 | 78 | 22.2 | 527 | 26.6 |

| South | 610,221 | 40.0 | 775 | 33.2 | 120 | 34.1 | 655 | 33.1 |

| West | 308,254 | 20.2 | 574 | 24.6 | 82 | 23.3 | 492 | 24.8 |

| Year of delivery | ||||||||

| 2008–09 | 396,929 | 26.0 | 526 | 22.5 | 71 | 20.2 | 455 | 23.0 |

| 2010–11 | 458,653 | 30.1 | 783 | 33.6 | 116 | 33.0 | 667 | 33.7 |

| 2012–14 | 668,495 | 43.9 | 1,025 | 43.9 | 165 | 46.9 | 860 | 43.4 |

Pregnancies lasting more than 20 gestational weeks.

Severe CHD: Non-severe CHD χ2 p<0.05.

18,630 women missing region of residence at delivery.

Figure 2. Prevalence of echocardiograms and cardiac-related prescriptions filled during pregnancies* of privately insured women aged 15 to 44 y with and without congenital heart defects (CHDs), 2007 to 2014.

*From last menstrual period to 90 days postpartum in pregnancies lasting more than 20 gestational weeks. †Any: No CHD χ2 p<0.05. ‡Severe: Non-severe χ2 p<0.05. §Included medications are listed in Supplemental Table 2.

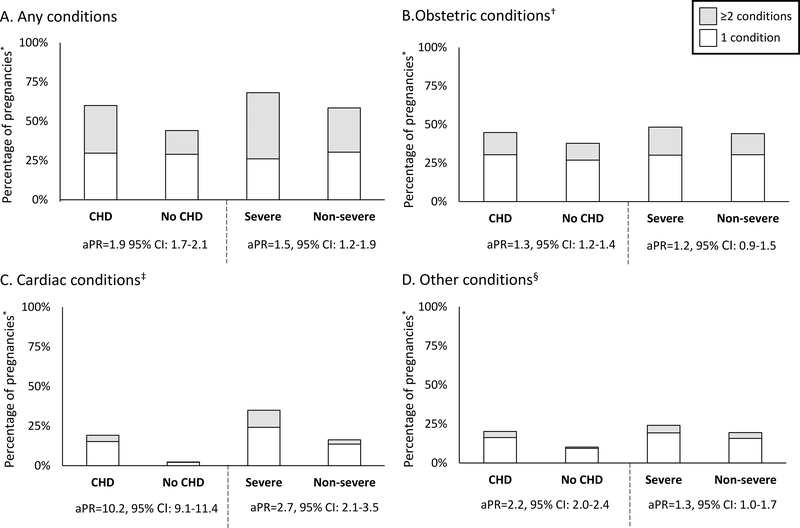

The prevalence of any, obstetric, cardiac, and other conditions in women with CHD was 60%, 45%, 19%, and 20%, respectively (Figure 3). APRs comparing women with CHD to those without were elevated for any (aPR=1.9, 95% CI: 1.7–2.1), obstetric (aPR=1.3, 95% CI: 1.2–1.4), cardiac (aPR=10.2, 95% CI: 9.1–11.4), and other conditions (aPR=2.2, 95% CI: 2.0–2.4). Overall, 60% of women with CHD had ≥1 adverse conditions compared to 45% of women without, and of those, more than twice as many women with CHD experienced ≥2 conditions compared to those without CHD (30.3% vs. 15.1%).

Figure 3. Prevalence and adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) for adverse conditions in pregnancies of privately-insured women aged 15–44 with and without congenital heart defects (CHD) 2007–2014.

aPR: Prevalence ratio for ≥1 complication vs. none adjusted for age, region of residence and year at delivery; CI: Confidence interval; *Pregnancies lasting more than 20 gestational weeks. †Obstetric conditions include gestational diabetes; gestational hypertension, eclampsia or preeclampsia; hemorrhage; hysterectomy; infections including chorioamnionitis, endocarditis, endometritis, endomyometritis, metritis, pyelonephritis, and sepsis; maternal death; obstetric shock; placental abruption; placenta previa; premature rupture of membranes; preterm labor or preterm birth; and transfusion. ‡Cardiac conditions include atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter or supraventricular tachycardia; cardiomyopathy; conduction disorders; coronary dissection; heart failure; incident ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, or sudden cardiac arrest; and myocardial infarction or ischemia. §Other conditions include acute renal failure; acute respiratory distress syndrome; anemia; deep vein thrombosis; disseminated intravascular coagulation; mechanical ventilation; pulmonary disease; pulmonary edema; pulmonary embolism; pulmonary hypertension; seizure disorders; stroke or cerebrovascular disorders; and thrombocytopenia.

Pregnancies in women with severe CHD, compared to non-severe CHD, had elevated aPRs for any (aPR=1.5, 95% CI: 1.2–1.9) and cardiac conditions (aPR=2.7, 95% CI: 2.1–3.5) (Figure 3). Among those who experienced ≥1 adverse conditions, more women with severe CHD experienced ≥2 conditions in pregnancy (any, obstetric only, cardiac only, or other) than women with non-severe CHD. Women with non-severe CHD had 1.8 times (95% CI: 1.6–2.0) the prevalence of any conditions compared to women without CHD.

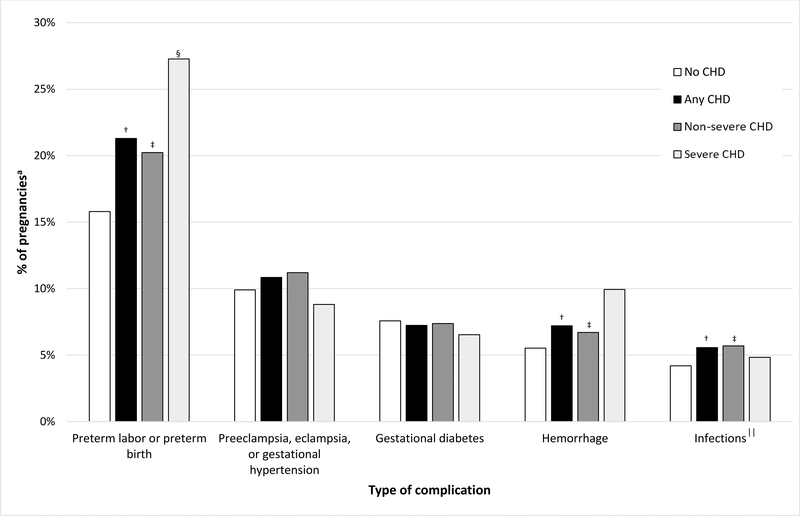

Among women with CHD, the most common conditions were preterm labor/preterm birth; preeclampsia, eclampsia, or gestational hypertension; gestational diabetes; hemorrhage; and infections. Prevalence of preterm labor/preterm birth differed by both CHD presence (any or non-severe CHD vs. none) and severity (severe vs. non-severe CHD). Prevalence of hemorrhage and infections differed only by CHD presence (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Top five most prevalent obstetric conditions in pregnancies* of privately-insured women aged 15–44 with and without congenital heart defects (CHD), 2007–2014.

*Among pregnancies lasting more than 20 gestational weeks. †Any: No CHD χ2 p<0.05. ‡Non-severe: No CHD χ2 p<0.05. §Severe: Non-severe χ2 p<0.05. ||Chorioamnionitis, endocarditis, endometritis, endomyometritis, metritis, pyelonephritis, or sepsis

Comparing women with CHD to those without, aPRs were elevated for 7 of 12 obstetric conditions and were highest for obstetric shock and transfusion (Table 2). Results were similar comparing women with non-severe CHD to women without CHD. Comparing women with severe CHD to non-severe CHD, aPRs were elevated for placental abruption and preterm labor/preterm birth.

Table 2.

Obstetric, cardiac, and other conditions associated with presence of congenital heart defects (CHD) in pregnancies* of privately-insured women aged 15–44, 2007–2014

| Type of Condition | No CHD (n=1,524,077) | CHD | Any: No CHD | Non-severe: No CHD | Severe: Non-severe | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (n=2,334) | Severe (n=352) | Non-severe (n=1,982) | ||||||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | aPR | (95% CI) | aPR | (95% CI) | aPR | (95% CI) | |

| Obstetric Conditions† | ||||||||||

| Obstetric shock | 778 (0.1) | 5 (0.2) | NR | NR | 4.3 | (1.8–10.3) | 4.0 | (1.5–10.7) | ---‡ | |

| Transfusion | 8,709 (0.6) | 30 (1.3) | 5 (1.4) | 25 (1.3) | 2.2 | (1.5–3.2) | 2.2 | (1.5–3.3) | --- | |

| Placental abruption | 16,106 (1.1) | 40 (1.7) | 14 (4.0) | 26 (1.3) | 1.6 | (1.2–2.2) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 3.0 | (1.5–6.0) |

| Preterm labor/preterm birth | 240,736 (15.8) | 497 (21.3) | 96 (27.3) | 401 (20.2) | 1.4 | (1.3–1.6) | 1.3 | (1.2–1.5) | 1.5 | (1.1–1.9) |

| Infections | 63,954 (4.2) | 130 (5.6) | 17 (4.8) | 113 (5.7) | 1.3 | (1.1–1.6) | 1.4 | (1.1–1.6) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.3) |

| Placenta previa | 37,730 (2.5) | 74 (3.2) | 12 (3.4) | 62 (3.1) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.6) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.6) | --- | |

| Hemorrhage | 84,100 (5.5) | 168 (7.2) | 35 (9.9) | 133 (6.7) | 1.3 | (1.1–1.5) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.4) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.3) |

| Cardiac Conditions§ | ||||||||||

| Conduction disorders | 1,094 (0.1) | 101 (4.3) | 47 (13.4) | 54 (2.7) | 63.0 | (50.8–78.2) | 39.2 | (29.5–52.2) | 5.5 | (3.6–8.4) |

| VT, VF or SCA | 555 (0.0) | 28 (1.2) | 7 (2.0) | 21 (1.1) | 34.4 | (23.4–50.5) | 30.1 | (19.4–46.9) | --- | |

| Heart failure | 2,330 (0.2) | 47 (2.0) | 16 (4.6) | 31 (1.6) | 14.0 | (10.4–18.9) | 10.7 | (7.5–15.4) | 3.0 | (1.5–5.8) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 1,908 (0.1) | 36 (1.5) | 7 (2.0) | 29 (1.5) | 13.1 | (9.4–18.4) | 12.6 | (8.5–17.8) | --- | |

| Myocardial infarction | 264 (0.0) | 5 (0.2) | NR | NR | 12.5 | (5.1–30.2) | 14.3 | (5.9–34.7) | --- | |

| AF, AFL or SVT | 32,091 (2.1) | 355 (15.2) | 97 (27.6) | 258 (13.0) | 8.5 | (7.6–9.5) | 7.1 | (6.2–8.1) | 2.5 | (1.9–3.2) |

| Other Conditions|| | ||||||||||

| Pulmonary hypertension | 544 (0.0) | 45 (1.9) | 12 (3.4) | 33 (1.7) | 57.2 | (41.6–78.8) | 48.6 | (33.4–70.6) | 2.3 | (1.1–4.6) |

| Stroke or cerebrovascular disorders | 2,380 (0.2) | 85 (3.6) | 10 (2.8) | 75 (3.8) | 24.5 | (19.5–30.7) | 25.4 | (20.0–32.3) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.5) |

| Pulmonary edema | 794 (0.1) | 8 (0.3) | NR | NR | 6.9 | (3.4–13.8) | 7.0 | (3.3–14.8) | --- | |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2,092 (0.1) | 19 (0.8) | 7 (2.0) | 12 (0.6) | 5.9 | (3.7–9.4) | 4.3 | (2.4–7.8) | 3.5 | (1.3–8.9) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 2,051 (0.1) | 17 (0.7) | 6 (1.7) | 11 (0.6) | 5.6 | (3.5–9.0) | 4.2 | (2.3–7.6) | 3.0 | (1.1–8.3) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 5,084 (0.3) | 36 (1.5) | NR | NR | 4.8 | (3.4–6.6) | 4.9 | (3.4–7.0) | --- | |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 4,728 (0.3) | 24 (1.0) | NR | NR | 3.4 | (2.2–5.1) | 3.8 | (2.5–5.8) | --- | |

| Acute renal failure | 1,365 (0.1) | 6 (0.3) | NR | NR | 2.9 | (1.3–6.4) | 2.6 | (0.8–6.1) | --- | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 2,513 (0.2) | 9 (0.4) | NR | NR | 2.4 | (1.2–4.6) | 1.5 | (0.6–3.7) | --- | |

| Pulmonary disease | 45,692 (3.0) | 137 (5.9) | 26 (7.4) | 111 (5.6) | 2.0 | (1.7–2.4) | 1.9 | (1.6–2.3) | 1.3 | (0.8–2.1) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18,783 (1.2) | 45 (1.9) | 10 (2.8) | 35 (1.8) | 1.6 | (1.2–2.2) | 1.4 | (1.0–2.0) | 1.8 | (0.9–3.8) |

| Anemia | 84,648 (5.6) | 160 (6.9) | 22 (6.3) | 138 (7.0) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.4) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.5) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.4) |

aPR: Prevalence ratio adjusted for age, region of residence and year at delivery; CI: Confidence interval; NR: not reported (N<5); AF: Atrial fibrillation; AFL: Atrial Flutter; SCA: Sudden cardiac arrest SVT: Supraventricular tachycardia; VT: Ventricular tachycardia; VF: Ventricular fibrillation.

Among pregnancies lasting >20 gestational weeks.

Obstetric conditions not associated with presence/severity of CHD included: gestational diabetes; hemorrhage; hysterectomy; infections including chorioamnionitis, endocarditis, endometritis, endomyometritis, metritis, pyelonephritis, or sepsis; maternal death during admission; placenta previa; and preeclampsia, eclampsia, and gestational hypertension.

For certain outcomes with low prevalence by CHD severity, the aPRs could not be calculated.

No women with CHD experienced coronary dissection during pregnancy.

No women experienced seizure disorders during pregnancy.

The prevalence of individual cardiac conditions during pregnancy were 9 to 63 times higher among women with CHD compared to those without (Table 2), and 7 to 39 times higher among women with non-severe CHD compared to those without. Conduction disorders and ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), or sudden cardiac arrest had the largest aPRs. Comparing women with severe CHD to those with non-severe CHD, aPRs for conduction disorders, heart failure, and atrial flutter were elevated.

Comparing women with CHD to those without, aPRs were elevated for 12 of 13 other conditions and were highest for pulmonary hypertension and stroke or cerebrovascular disorders (Table 2). Women with non-severe CHD also had elevated aPRs for 8 of 13 other conditions compared to those without. Comparing women with severe CHD to non-severe CHD, aPRs were elevated for pulmonary hypertension, pulmonary embolism, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Stillbirths were more prevalent in pregnancies among women with CHD and women with non-severe CHD than those among women without (Table 3). Among pregnancies ending in live birth, preterm births were more prevalent in pregnancies among women with CHD and non-severe CHD compared to those without and among women with severe compared to non-severe CHD. Prevalence of cesarean delivery was elevated among women with CHD and non-severe CHD compared to those without and among women with severe compared to non-severe CHD. Results did not change appreciably when limiting analyses to the first pregnancy from 2008–2013 (excluding 149,373 pregnancies), nor when excluding 336 women with ostium secundum type ASD only.

Table 3.

Outcomes and characteristics of pregnancy* among privately-insured women aged 15–44 with and without congenital heart defects (CHD), 2007–2014

| No CHD (n=1,524,077) | CHD | Any: No CHD | Non-severe: No CHD | Severe: Non-severe | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any (n=2,334) | Severe (n=352) | Non-severe (n=1,982) | ||||||||||||||

| N | % | n | % | N | % | n | % | aPR | (95% CI) | aPR | (95% CI) | aPR | (95% CI) | |||

| Pregnancy Outcome | ||||||||||||||||

| Any live birth† | 1,513,169 | 99.3 | 2,306 | 98.8 | 348 | 98.9 | 1,958 | 98.8 | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||||

| Any stillbirth† | 11,460 | 0.8 | 28 | 1.2 | 4 | 1.1 | 24 | 1.2 | 1.6 | (1.1–2.4) | 1.6 | (1.1–2.5) | 1.1 | (0.4–3.3) | ||

| Delivery characteristics live births only) | n=1513169 | n=2306 | n= 348 | n=1958 | ||||||||||||

| Cesarean delivery | 533782 | 35.3 | 924 | 40.1 | 153 | 44.0 | 771 | 39.4 | 1.3 | (1.2–1.4) | 1.2 | (1.1–1.3) | 1.4 | (1.1–1.8) | ||

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks) | 128,912 | 8.5 | 294 | 12.8 | 61 | 17.5 | 233 | 11.9 | 1.6 | (1.4–1.8) | 1.5 | (1.3–1.7) | 1.6 | (1.2–2.3) | ||

aPR: prevalence ratio adjusted for age, region of residence and year at delivery; CI: confidence interval.

Pregnancies lasting more than 20 gestational weeks.

Includes 552 that were live birth and still birth.

DISCUSSION

Only about one in two privately insured women with CHD and 3 in 4 with severe CHD received AHA/ACC-recommended comprehensive echocardiograms during pregnancy. Additionally, 4% of pregnant women with CHD filled prescriptions for potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac-related medications. Women with CHD had higher prevalence of adverse pregnancy outcomes, including stillbirth and preterm birth, elevated prevalence of adverse conditions overall, and 34 to 63 times higher prevalence of pulmonary hypertension, conduction disorders, and VT, VF, or sudden cardiac arrest compared to women without CHD. Though women with severe CHD were most affected, pregnancies among women with non-severe CHD also had higher prevalence of adverse conditions than women without CHD.

Several AHA/ACC and ACOG statements for women with CHD recommend that obstetricians and adult CHD cardiologists collaboratively manage pregnancies among women with symptomatic or complex CHD; that pregnant or postpartum women with known or suspected CHD receive echocardiograms; and that clinicians review benefits and risks of medications known to be teratogenic or fetotoxic and make appropriate adjustments, as needed.11, 12, 30, 5 Yet, only slightly more than half of all pregnant women with CHD received comprehensive echocardiograms. Additionally, 4 out of 100 women filled prescriptions for potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac-related medications during pregnancy. Guidelines recommend evaluations of health risks begin before conception, but, in a similar sample of privately-insured women with CHD, <1% received all AHA/ACC-recommended preconception assessments in the year before conception.19 However, in that sample, 9% of women filled prescriptions for the same list of potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac-related medications in the year before pregnancy began, suggesting women with CHD may decrease their use of these medications during pregnancy. However, it is unknown whether women in our study population discussed their medication use with their provider prior to making any changes, in accordance with the AHA/ACC and ACOG recommendations.

Two non-U.S. hospital-based studies examined pregnancy outcomes among women with congenital and acquired heart disease combined, but did not provide results specific to women with CHD nor to women outside of their cardiac patient population.13, 14 Nevertheless, our overall prevalence of 19% for ≥1 cardiac condition among women with CHD was comparable to 16% reported by the Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy Study (CARPREG) II Canadian study of 1,938 pregnancies of congenital or acquired heart disease patients at two large hospitals.13 Prevalence of cardiac conditions in our analysis was higher than 6.6% in the Neonatal and Maternal Outcomes of Pregnancy with Maternal Cardiac Disease (NORMANDY) French hospital-based study of 197 pregnancies of congenital or acquired heart disease patients. Additionally, more than 50% with CHD in our sample experienced obstetric events relative to 35% with heart disease in NORMANDY, but NORMANDY included a different, smaller subset of obstetric events.14

Our estimate that 19% of pregnant women with CHD experience cardiac conditions was greater than the 2.3–6.6% estimates from three National Inpatient Sample analyses on 10,000–40,000 pregnancies of women with CHD; however, these studies cannot examine events documented outside of the delivery hospitalization.7–9, 14 Similar to our findings, studies using inpatient data reported that women with CHD have increased risk of transfusion, arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, cerebrovascular disorders, preterm delivery, and stillbirth.7–10, 17 One found women with severe CHDs had more heart failure, conduction disorders, and rhythm disorders than women with mild-to-moderate CHDs, though adjusted estimates were not provided.10 Another reported elevated prevalence of preterm labor, infections, anemia, heart failure, and atrial and ventricular arrhythmias among women with non-complex CHD compared to women with no CHD.17

This is the first analysis, to our knowledge, examining receipt of AHA/ACC-recommended cardiac evaluations and filled prescriptions for potentially teratogenic or fetotoxic cardiac-related medications during pregnancy. Our analysis benefited from a large, nationwide sample of pregnancies with severe, non-severe, and no CHD linked to prescription drug data. We were able to assess rare conditions not included in previous studies, such as hysterectomy and obstetric shock. However, as a convenience sample of women continuously enrolled in private insurance with prescription drug coverage, results are likely not generalizable to all women in the U.S. We expect receipt of AHA/ACC-recommended cardiac evaluations to be lower among women covered by Medicaid and those who are not enrolled in health insurance continuously throughout pregnancy. Use of administrative data may result in misclassification of CHD status, pregnancy identification/timing, and adverse conditions. We implemented algorithms to help improve the positive predictive value for both CHD status and conditions (e.g. excluding women with CHD documented only during pregnancy possibly reflecting a fetal CHD, requiring ≥2 outpatient visits to define CHD).23 If excluded women are healthier than included cases, we could have overestimated prevalence of conditions in women with CHD. Alternatively, if women with CHD were incorrectly classified as not having CHD, we may have underestimated the prevalence of conditions among those with CHD. Information on the cardiac functional status or the full history of surgical repair was not available in our datasets and we were unable to use that information in the classification of CHD severity. Additionally, for some conditions, it was not possible to separate events incident to pregnancy from those chronic or pre-existing (e.g. deep vein thrombosis, heart failure). We also had no information on the indication for the medications prescribed during pregnancy or on counseling about medication risks and benefits.

Conclusions

We found women with CHD (any, severe only, and non-severe only) had higher prevalence of adverse pregnancy outcomes and conditions than women without CHD, yet only half received recommended comprehensive echocardiograms during pregnancy or up to 90 days postpartum. AHA/ACC and ACOG recommendations to assess cardiac health, including performing echocardiograms and reviewing medications for benefits and risks, in pregnant women with CHD may lead to early identification, prevention, or treatment of adverse conditions and improved pregnancy outcomes.11, 12, 30, 5

Supplementary Material

What is Known

Hemodynamic changes during pregnancy may lead to increased risk of adverse pregnancy conditions for women with severe and non-severe congenital heart defects (CHD).

American Heart Association and American College of Gynecology guidelines recommend that women with CHD consult with both obstetricians and cardiologists during pregnancy, receive comprehensive echocardiograms during pregnancy or postpartum, and review benefits and risks of medication use during pregnancy with a clinician.

What the Study Adds

Women with CHD, compared to without CHD, and severe CHD, compared to non-severe, had increased prevalence of obstetric, cardiac, and other adverse conditions and outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum.

Women with non-severe CHD also had increased prevalence of adverse conditions and outcomes during pregnancy and postpartum compared to women without CHD.

Approximately 4% of women with CHD used potentially teratogenic medications and only 56% of women with CHD received a comprehensive echocardiogram to evaluate cardiac health during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

The findings and conclusion in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This analysis has been replicated by C.J. Alverson and Regina Simeone.

Funding sources: The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial support, or acknowledgements to report.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Reller MD, Strickland MJ, Riehle-Colarusso T, Mahle WT and Correa A. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in metropolitan Atlanta, 1998–2005. The Journal of pediatrics. 2008;153:807–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffman JI and Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:1890–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oster ME, Lee KA, Honein MA, Riehle-Colarusso T, Shin M and Correa A. Temporal trends in survival among infants with critical congenital heart defects. Pediatrics. 2013;131:e1502–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Opotowsky AR, Siddiqi OK, D’Souza B, Webb GD, Fernandes SM and Landzberg MJ. Maternal cardiovascular events during childbirth among women with congenital heart disease. Heart. 2012;98:145–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canobbio MM, Warnes CA, Aboulhosn J, Connolly HM, Khanna A, Koos BJ, Mital S, Rose C, Silversides C, Stout K, American Heart Association Council on C, Stroke N, Council on Clinical C, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Y, Council on Functional G, Translational B, Council on Quality of C and Outcomes R. Management of Pregnancy in Patients With Complex Congenital Heart Disease: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e50–e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornette J, Ruys TP, Rossi A, Rizopoulos D, Takkenberg JJ, Karamermer Y, Opic P, Van den Bosch AE, Geleijnse ML, Duvekot JJ, Steegers EA and Roos-Hesselink JW. Hemodynamic adaptation to pregnancy in women with structural heart disease. International journal of cardiology. 2013;168:825–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karamlou T, Diggs BS, McCrindle BW and Welke KF. A growing problem: maternal death and peripartum complications are higher in women with grown-up congenital heart disease. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2011;92:2193–8; discussion 2198–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lima FV, Yang J, Xu J and Stergiopoulos K. National Trends and In-Hospital Outcomes in Pregnant Women With Heart Disease in the United States. The American journal of cardiology. 2017;119:1694–1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson JL, Kuklina EV, Bateman BT, Callaghan WM, James AH and Grotegut CA. Medical and Obstetric Outcomes Among Pregnant Women With Congenital Heart Disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:346–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schlichting LE, Insaf TZ, Zaidi AN, Lui GK and Van Zutphen AR. Maternal Comorbidities and Complications of Delivery in Pregnant Women With Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019;73:2181–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 212 Summary: Pregnancy and Heart Disease. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019;133:1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, Child JS, Connolly HM, Dearani JA, Del Nido P, Fasules JW, Graham TP Jr., Hijazi ZM, Hunt SA, King ME, Landzberg MJ, Miner PD, Radford MJ, Walsh EP and Webb GD. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines on the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease). Developed in Collaboration With the American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;52:e143–e263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silversides CK, Grewal J, Mason J, Sermer M, Kiess M, Rychel V, Wald RM, Colman JM and Siu SC. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women With Heart Disease: The CARPREG II Study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018;71:2419–2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonnet V, Simonet T, Labombarda F, Dolley P, Milliez P, Dreyfus M and Hanouz JL. Neonatal and maternal outcomes of pregnancy with maternal cardiac disease (the NORMANDY study) : Years 2000–2014. Anaesthesia, critical care & pain medicine. 2018;37:61–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Hagen IM, Roos-Hesselink JW, Donvito V, Liptai C, Morissens M, Murphy DJ, Galian L, Bazargani NM, Cornette J, Hall R and Johnson MR. Incidence and predictors of obstetric and fetal complications in women with structural heart disease. Heart. 2017;103:1610–1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pillutla P, Nguyen T, Markovic D, Canobbio M, Koos BJ and Aboulhosn JA. Cardiovascular and Neonatal Outcomes in Pregnant Women With High-Risk Congenital Heart Disease. The American journal of cardiology. 2016;117:1672–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayward RM, Foster E and Tseng ZH. Maternal and Fetal Outcomes of Admission for Delivery in Women With Congenital Heart Disease. JAMA cardiology. 2017;2:664–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson KN, Tepper NK, Downing K, Ailes EC, Abarbanell G and Farr SL. Contraceptive methods of privately insured US women with congenital heart defects. American heart journal. 2020;222:38–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farr SL, Downing KF, Ailes EC, Gurvitz M, Koontz G, Tran EL, Alverson CJ and Oster ME. Receipt of American Heart Association-Recommended Preconception Health Care Among Privately Insured Women With Congenital Heart Defects, 2007–2013. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2019;8:e013608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods GM, Boulet SL, Texter K, Yates AR and Kerlin BA. Venous thromboembolism in chronic pediatric heart disease is associated with substantial health care burden and expenditures. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3:372–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halasa NB, Shankar SM, Talbot TR, Arbogast PG, Mitchel EF, Wang WC, Schaffner W, Craig AS and Griffin MR. Incidence of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease among Individuals with Sickle Cell Disease before and after the Introduction of the Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2007;44:1428–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grosse SD, Boulet SL, Grant AM, Hulihan MM and Faughnan ME. The use of US health insurance data for surveillance of rare disorders: hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Genetics in medicine : official journal of the American College of Medical Genetics. 2014;16:33–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khan A, Ramsey K, Ballard C, Armstrong E, Burchill LJ, Menashe V, Pantely G and Broberg CS. Limited Accuracy of Administrative Data for the Identification and Classification of Adult Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2018;7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glidewell J, Book W, Raskind-Hood C, Hogue C, Dunn JE, Gurvitz M, Ozonoff A, McGarry C, Van Zutphen A, Lui G, Downing K and Riehle-Colarusso T. Population-based surveillance of congenital heart defects among adolescents and adults: surveillance methodology. Birth defects research. 2018;110:1395–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitra M, Parish SL, Clements KM, Cui X and Diop H. Pregnancy outcomes among women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015;48:300–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ailes EC, Simeone RM, Dawson AL, Petersen EE and Gilboa SM. Using insurance claims data to identify and estimate critical periods in pregnancy: An application to antidepressants. Birth defects research Part A, Clinical and molecular teratology. 2016;106:927–934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tepper NK, Boulet SL, Whiteman MK, Monsour M, Marchbanks PA, Hooper WC and Curtis KM. Postpartum venous thromboembolism: incidence and risk factors. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;123:987–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frohnert BK, Lussky RC, Alms MA, Mendelsohn NJ, Symonik DM and Falken MC. Validity of hospital discharge data for identifying infants with cardiac defects. Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association. 2005;25:737–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez FH 3rd, Ephrem G, Gerardin JF, Raskind-Hood C, Hogue C and Book W. The 745.5 issue in code-based, adult congenital heart disease population studies: Relevance to current and future ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM studies. Congenital heart disease. 2018;13:59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, Bozkurt B, Broberg CS, Colman JM, Crumb SR, Dearani JA, Fuller S, Gurvitz M, Khairy P, Landzberg MJ, Saidi A, Valente AM and Van Hare GF. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.