Abstract

This article describes the development of a framework for the Spanish language adaptation of an evidence-based intervention. A systematic literature search of language adaptation of interventions highlighted most published research focuses on the translation of assessment tools rather than interventions. In response, we developed the Participatory and Iterative Process Framework for Language Adaptation (PIPFLA), a descriptive step-by-step example of how to conduct the language adaptation of an intervention that is grounded in principles of good practice and facilitates transparency of the process. A bilingual team composed of project staff, translators, and two small panels of local community experts—composed of Latino community-based clinicians and Latino immigrant parents—participated in the language adaptation of the intervention. The panels reviewed the translated materials and offered their independent emic perspectives; the intervention represented the etic perspective. Both perspectives informed and were integrated into the 11-step iterative process that comprises the PIPFLA framework.

Keywords: language translation, Spanish language adaptation, back translation, community experts

Disparities in the provision and receipt of health care among ethnic and racial minority groups in the United States are longstanding (Cook, McGuire, & Miranda, 2007). The heterogeneity of groups experiencing this disparity has generated concerns about the generalizability of evidence-based treatments (EBTs) to ethnic-racial minorities (Castro, Barrera, & Holleran Steiker, 2010) and efforts to adapt EBTs to meet their needs and diverse experiences (e.g., Bernal, 2006; Bernal & Scharró-del-Río, 2001; Lau, 2006). A common adaptation with language minority populations is the translation of intervention materials to clients’ native language. Language serves as a social determinant that influences access to care and functions as a barrier to both the provision of services and to service use by individuals with none to limited English proficiency (LEP; Fiscella, Franks, Doescher, & Saver, 2002; Sentell, Shumway, & Snowden, 2007). Data on the foreign born in the United States indicate that this population increased 30% from 2000 to 2012, and that 26.8% of children and 51.5% of adults are not English-proficient (Patten, 2012). Although the availability of interventions in clients’ native language is one of numerous factors contributing to mental health care disparities (e.g., insurance status, expenditure, poverty, stigma, acculturation, and cultural adaptation needs), addressing language contributes to narrowing the gap between need and access to services (Bauer, Chen, & Alegría, 2010; Cook et al., 2007; Sentell et al., 2007). Moreover, because mental health assessment, treatment, and monitoring heavily depend on direct communication with clients as compared with other health disciplines (i.e., blood tests, blood pressure, x-rays, medication, etc.), language barriers may pose greater challenges to service provision, engagement, and use (Keyes et al., 2012; Saechao et al., 2012; Sentell et al., 2007).

Language adaptation,1 rather than a simple word-by-word replacement exercise, is an interpretation of meaning in the source language that moves translation beyond the confines of grammatical rules and writing conventions to interpretation that is informed by socio-cultural and contextual factors (e.g., Alegria et al., 2004; Bravo, Woodbury-Fariña, Canino, & Rubio-Stipec, 1993). Hence, language adaptation requires the use of a combined emic (within-culture/insider’s perspective) and etic (similarities across cultures/outsider’s perspective) paradigm to inform and guide the process (Berry, 1999; Matías-Carrelo et al., 2003).

The objective of this article is twofold. First, we describe the method and results of a systematic search conducted of the published literature on language adaptation of interventions to identify standard recommended best practices and a language adaptation framework for interventions to inform our work with Latino immigrant families. Second, reflecting limitations in this literature, we describe the participatory and iterative process framework we developed for the language adaptation of the Helping the Noncompliant Program, an efficacy-based behavior parent training program (HNC; McMahon & Forehand, 2003), including the intervention manual, training materials, and parent handouts.

Method

Systematic Literature Search

The second and third authors conducted a systematic search to identify peer-reviewed literature that involved translations, specifically language adaptations of interventions, using eight online medical and social science databases: PsycInfo, PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, Academic Search, PsychArticles, CQ Researcher, and ERIC. Inclusion criteria required that manuscripts be English-language and in a peer-reviewed journal resulting in a total of 135 relevant articles. The following seven search terms were selected and searched individually and in combination in the title, abstract, and keywords: language translation, foreign language translation, intervention translation, adaptation, mental health, Spanish adaptation, and model of language adaptation. Relevance was determined by reading the abstracts of each paper. In order to be included, manuscripts had to describe a translation or language adaptation process. Our greatest yield came from PsycInfo, the first search, which resulted in 464 publications, 87 of which described a translation or adaptation process. Our search using PubMed resulted in 140 publications, 15 of which were relevant and not previously identified via PsycInfo. The following search engines lead us to 33 relevant and not previously identified articles: Medline (n = 24), Google Scholar (n = 7), and Academic Search (n = 2). Searches using CQ Researcher, PsychArticles, and ERIC resulted in no new articles. Articles describing a cultural adaptation without a language component were not included in the final list.

A closer look at the 135 articles revealed that the large majority described the translation of research measures (n = 108) rather than intervention or prevention programs (n = 13). Others offered guidelines and advice on how to effectively translate measures (n = 5) and how to effectively make use of interpreters during treatment (n = 2), and guidelines for cultural adaptations of treatments (n = 5). One article provided a review of translations of psychological measures, and another was an adaptation for Native Americans that did not include a language component. For our final selection, translations of assessment tools were excluded. Cultural adaptations not involving a translation (e.g., cultural adaptation for an English-speaking population) were also excluded. This resulted in 13 articles on the adaptation of intervention or prevention programs with a language component.

Coding Procedures

Thirteen manuscripts describing language adaptation of an intervention were reviewed and coded independently by the second and third authors. Coding consisted of identifying whether or not each manuscript detailed a number of translation and adaptation strategies. These strategies were as follows: (1) forward translation, (2) back translation, (3) cultural considerations, (4) community or expert consultation, (5) translation or adaptation of manuals, (6) translation or adaptation of client handouts, and (7) whether authors provide details about the adaptation and or translation process. Definitions for each criterion are provided in Table 1. Following independent review, coders compared ratings, and only two discrepancies were identified. The discrepancies were resolved by consulting the manuscript again and with the first author, who acted as the final decision-maker.

Table 1.

Coding Criteria for Intervention Translations.

| Code | Definition | Number and percentage of interventions meeting criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Translation | Literal translation of intervention from one language to another. | 11, 85% |

| Back translation | Translation of target language version back to the original language version. | 5, 45%a |

| Cultural considerations | Cultural considerations were taken into account during translation process, by changing expressions and even content of intervention. | 11, 77% |

| Community or expert consultation | Use of experts or community members to inform translation and adaptations. | 13, 92% |

| Manual translated | Actual intervention manual was translated into target language. | 8, 73%a |

| Client handouts translated | Translation of handouts and other therapeutic materials that are given to the clients. | 10, 91%a |

| Details of translation provided | The extent to which authors provided sufficient detail about the processes used for adaptation and translation. | 8, 54% |

Percentages calculated out of total interventions that were translated (n = 11).

Results

Eighty-five percent of programs proceeded with a translation, with 45% of those also utilizing a back translation. Most programs went beyond conceptual and semantic translations and incorporated cultural adaptations (77%), including expressions, dialects, and content adaptations. In order to develop responsive cultural adaptations, experts and/or community members often were involved as consultants (92%) through focus groups or interviews. Of the 11 programs that proceeded with a translation, 73% translated the manual and 91% translated clients’ handouts. However, it is important to note that only 54% of programs provided details about the adaptation and translation process; although these programs incorporated a systematic or a priori approach—in varying degrees—to inform their language adaptation process, only three of the 13 manuscripts cited their source. This suggests that perhaps the percentage of strategies used may in reality be higher, but manuscripts may not have described them with enough detail to code for them. Table 2 presents all 13 interventions and their use of specific translation and adaptation strategies.

Table 2.

Intervention Details.

| Citations | Language | Name of intervention | Target | Translation | Back translation | Cultural considerations | Community or expert consultation | Manual translated | Client handouts translated | Details provided of adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bauermeister et al. (2006) | Arabic, Hebrew Portugeuese | Behavioral therapies for children and adolescents | Internalizing and externalizing behaviors of children | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Borrego, Anhalt, Terao, Vargas, and Urquiza (2006) | Spanish | Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) | Parent training | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Cohen and Flaskerud (2008) | Spanish | Stress management | Stress | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Collado, Castillo, Maero, Lejuez, and Macpherson (2014) | Spanish | Brief Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression (BATD) | Depression | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| D’angelo et al. (2009) | Spanish | Preventive Intervention Program for Depression | Depression prevention | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Dumas, Arriaga, Begle, and Longoria (2010) | Spanish | Parenting our Children to Excellence (PACE) | Parent training | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Erkoboni, Ozanne-Smith, Rouxiang, and Winston (2010) | Chinese | Injury prevention | Use of booster seats | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NA – TV ad | No |

| Kopelowicz (1998) | Spanish | Social and indep. living skills | Social skills in persons with schizophrenia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lintvedt, Griffiths, Eisemann, and Waterloo (2013) | Norwegian | MoodGym and BluePages | Depression prevention | Yes | No | No | Yes | NA - internet-based | Yes | No |

| Matos, Torres, Santiago, Jurado, and Rodríguez (2006) | Spanish | Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) | Parent training | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| McCabe, Yeh, Garland, Lau, and Chavez (2005) | Spanish | Guiando a ninos activos (GANA; PCIT) | Parent training | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Ortega, Giannotta, Latina, and Ciairano (2012) | Italian | The Strengthening Families Program (SFP) | Family skills training | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pekmezi et al. (2012) | Spanish | Seamos Saludables | Physical activity | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | 5 | 10 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 7 | ||||

| Overall percentage | 85 | 38 | 77 | 92 | 62 | 77% | 54% | |||

| Percentage of translated interventions (out of 11) | 45 | 73 | 91% | |||||||

Discussion

The limited number of articles available on this topic revealed different approaches to language adaptation and inconsistent terminology (Wild et al., 2005) highlighting a need for a framework for the language adaptation of interventions grounded in current recommended best practices. Although language adaptation procedures vary, they have several key components in common including a multi-step or stage process that includes generally at least two translations (forward and back), reviews of the translation by a panel of experts, incorporation of feedback into a revised version of the translated document, and coming to consensus on the final version. Their common goal is at minimum a final translated product that is semantically and conceptually equivalent to the constructs in the original document. The remaining sections describe the development of a framework for the language adaptation of an evidence-based intervention, HNC (McMahon & Forehand, 2003).

Language Adaptation Team

A nine-person bilingual team composed of project staff, translators and local community experts (eight Latinos, one European American: first and fourth authors, two translators, and a five-member panel of local experts) participated in the language adaptation of the HNC. The first and fourth authors had extensive experience working with Latino immigrants. The first author was a member of the Spanish language adaptation team for two editions of another parent training program (Gross, Julion, Garvey, Breitenstein, Maríñez-Lora, & Ordaz, 2011; Gross, Julion, Garvey, Maríñez-Lora, & Ordaz, 2008). One translator had prior experience translating research measures for Latino immigrant adolescents. The second translator (back translator) had several years’ experience translating research, medical, and consent documents for low-income Latino immigrants. Translators were recommended by colleagues of the first author. Two small panels of local experts were recruited: One panel was composed of three local community-based clinicians, and the second panel was composed of three Latino immigrant parents (see Table 3 for more details on members of the adaptation team). Clinical panel members were recruited from a pool of bilingual community-based Latino clinicians who had worked with the first and second authors in the past. Parent panel members were recruited from a pool of Latino immigrant parents who had worked with the first author in the past. Both panels were consulted on the semantic, conceptual, and experiential equivalence of all materials and, specifically, on the appropriateness and readability of the translated parent handouts (Beaton, Bombardier, Guillemin, & Ferraz, 2000). Providers received a copy of the English version of all intervention materials and their corresponding Spanish counterparts; parents received a copy of the Spanish translation of the parent handouts.

Table 3.

Language Adaptation Team.

| Project staff and translation team | |

| Project staff | Translators |

| First author: Dominican immigrant, PhD. More than a decade working with Latino immigrants and parent training. | Translator: BS, Latino female, educated in Puerto Rico, attending graduate school in the United States; prior experience translating research measures for Latino immigrant adolescents. |

| Fourth author: Ecuadorian American, MSW. Prior work history working with Latino immigrant families and also advocating for undocumented Latino youth. | Back translator: BS, European American, male, degree in Spanish/linguistics, lived in Spain and Latin America, prior experience translating research, medical and consent documents for low-income Latino immigrants in Chicago. |

| Panel of local experts | |

| Clinical members | Parent members |

| MSW, Puerto Rican, female: trained in Puerto Rico, working in the United States, and familiar with parent training program. | Mexican immigrant, female: experience being a Latino family advocate and a leader.a |

| Bilingual school counselor, Columbian immigrant, female: trained in Columbia and the United States, familiar with using a similar parent training program with Latino immigrant parents.b | Mexican immigrant, male: ESL teacher to Latino adults in a community center serving immigrant families. |

| BS social worker, female, Mexican immigrant: trained in the United States. | Colombian immigrant, female: also a school counselor in a predominantly Latino serving school.b |

Note. ESL = English as a second language.

Parent reviewed translated parent handouts with three friends from church.

One local expert was both an immigrant parent and a clinician, and served on both panels.

The decision to translate the entire manual and the training materials rather than only the parent handouts was influenced by the clinician population serving potential participants (i.e., Latino immigrant parents) in the three participating community mental health agencies: clinicians of Latino background with diverse generational status and varying degrees of fluency and formal education in Spanish, and non-Latino clinicians with a combination of formal education in Spanish and years of experience working with monolingual Spanish speaking Latino clients, both abroad and in the United States. All the clinicians were English-trained bilingual therapists. Hence, the translation of all intervention materials was an effort to (1) further standardize the delivery of the intervention by providing clinicians with the language or vocabulary to deliver the intervention to parents, (2) provide training in the intervention that compensated for clinicians’ lack of professional training and possible unfamiliarity with therapeutic terms and concepts in Spanish (Castaño, Biever, González, & Anderson, 2007), (3) minimize the allocation of cognitive resources and cognitive demands placed on clinicians to translate terms and concepts ad lib during the therapy session (e.g., Dong & Lin, 2013), and (4) relatedly—given that clinicians were themselves novices with the intervention—maximize the allocation of their attention and memory resources to the actual content of the intervention and to engaging families.

Participatory and Iterative Process Framework for Language Adaptation (PIPFLA)

We modified the 10-step process explicated in the Principles of Good Practice: The Cross-Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures, developed by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR). ISPOR conducted an extensive review of current methods and guidelines for the translation and cultural adaptation of patient-reported outcome measures (for detailed descriptions of these principles, see Wild et al., 2005) and presented 10 steps for language adaptation that included multiple opportunities for translation, back translation, cognitive debriefing, and harmonization. We applied and modified these steps to language adaptation for interventions. Specifically, some of the ISPOR recommendations were impractical due to time and resource constraints (e.g., multiple forward and backward translations), and others were revised to meet the unique needs of intervention versus measurement (e.g., additional harmonization steps). Additionally, cognitive debriefing was renamed Review by Panel of Local Experts, and the ISPOR review of cognitive debriefing results and finalization was combined with harmonization. The result was the PIPFLA presented here.

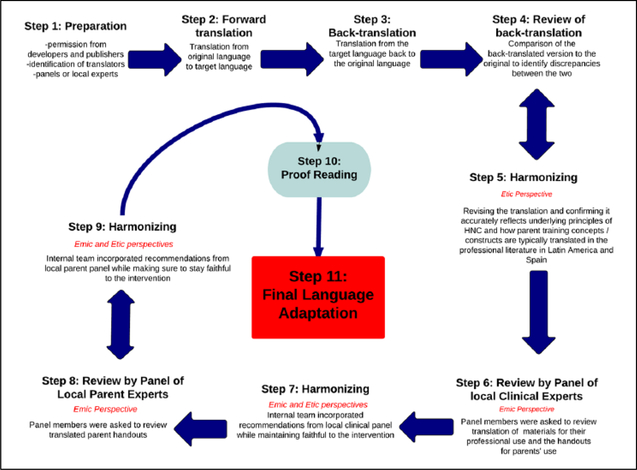

The PIPFLA is an 11-step process: (1) preparation, (2) forward translation, (3) back translation, (4) back-translation review, (5) harmonizing, (6) review by panel of local clinical experts, (7) harmonizing, (8) review by panel of local parent experts, (9) harmonizing, (10) proof reading, and (11) final version. Each step is described in detail in Figure 1. Behling and Law’s (2000) four criteria for evaluating methods used to prepare language adaptations in a target language were used to identify and evaluate the steps in the PIPFLA: Informativeness, Source Language Discrepancy, Security, and Practicality. Specifically, the iterative process of forward translation/back translation provided rich information about the semantic and conceptual equivalence of the language adaptation (Informativeness) and the discrepancies and translation ambiguities that needed to be addressed (Source Language Discrepancy) in order to retain the original meaning. The back translation, harmonizing steps, and reviews by local expert panels were the built-in mechanisms to increase confidence in the quality, usability, and experiential equivalence of the language adaptation (Security). Feasibility and affordability (Practicality) were evaluated at the beginning of the language adaptation and at each step of the process.

Figure 1.

Participatory and iterative process framework for language adaptation.

Balancing Etic and Emic Perspectives

In this language adaptation, mental health providers and parents offered independent emic (local and within-culture) perspectives, and the intervention (i.e., the HNC) represented the etic (outsider) perspective. The integration of both perspectives informed the iterative process (Berry, 1999) inherent to the PIPFLA framework. For example, during the first Harmonizing step, the first and fourth authors and the back translator evaluated the documents for Spanish language that strayed from the original English source language meaning and used their expertise, knowledge of other Spanish language adaptations of parenting programs, and examples in the professional literature on parent training from Latin America and Spain as guides to resolve discrepancies. During the second and third Harmonizing steps, the first and fourth authors incorporated recommendations from the panels of local experts while remaining faithful to the intervention. This process helped to ensure that the language adaptation of the HNC maintained its original, unmodified content and methods of presentation. Table 4 illustrates how the etic and emic perspectives were reflected in the language adaptation of the HNC.

Table 4.

Language Adaptation Examples of the HNC.

| Strategies and terms | ||||

| OK and not OK behaviors | Time out | Social rewards | Standing rules | Incorporating geographic differences |

| Conductas OKAY & NO OKAY | Tiempo Fuera | Elogios | Reglas Firmes y Constantes | Fósforos y cerillos (for matches) |

| HNC developer recommended keeping the OK and not OK (instead of conducta buena y conducta no buena) to reflect | Was translated to its conceptual and technical equivalent: Tiempo fuera. | Elogios was selected over alabanzas because alabanzas is used often in religious contexts | No Equivalent phrase in Spanish. Translation provided further clarification of strategy and concept | Automóvil was used instead of coche or carro (for car) because it was assumed to be a commonly known word across different Spanish speaking groups. |

| HNC’s de-emphasizing behaviors as bad/bueno or good/malo. | ||||

| Panel of local experts agreed that the term OKAY is a term Latino immigrants in the United States hear and use frequently. | Other Spanish translation of parenting programs and relevant professional literature from Latin America and Spain informed decision | Panel of local experts endorsed the choice of elogios over alabanzas. | Panel of local experts endorsed the more descriptive translation. | Obedece y Desobedece (for complying and not complying) instead of cumplir. Panel of experts suggested cumplir was seldom used in relation to children’s behavior but referred more to meeting responsibilities. |

| Description of the attending strategy | ||||

| Attending | Prestar Atención | |||

| Follows, rather than leads, the child’s activity (by a running verbal commentary, like a sportscaster narrates a game). | Seguir en vez de conducir o dirigir la actividad del niño (a través de comentarios continuos, como un locutor de deportes narrando un juego). | |||

| Used only to reinforce “OK” behaviors. | Se usa únicamente para reforzar el comportamiento “OK.” | |||

| Describe overt behavior (“You just put the red block on top of the green block.”) | Describir la conducta que se observa (“Estás poniendo el bloque rojo encima del bloque verde.”) | |||

| Emphasize desired prosocial behavior (“You’re talking in a regular voice.”) | Se usa para enfatizar la conducta prosocial deseada (“Estas hablando con un tono de voz normal”). | |||

| “Volume control” feature allows parents to raise or lower the intensity and frequency of the positive attention. | La característica de “control de volumen” permite al padre subir o bajar la intensidad y frecuencia de la atención positiva. | |||

Note. HNC = Helping the Noncompliant Child.

Clinician and Parental Response

Clinicians and parent participants in the research project—for which the PIPFLA was developed—participated in semi-structured interviews when they completed the parenting program. In these somewhat parallel interviews, participants were asked to describe what they liked, did not like, found helpful, not helpful, and what components or pieces of the intervention should be changed to best meet the needs of Latino immigrant parents. The quality of the language adaptation of the intervention was not identified as an area of concern in any of the 33 interviews conducted.

Logistics

Logistically, the language adaptation of the intervention—including manual, training materials, and handouts—required the translation (and back translation) of 100 pages consisting of 44,207 words. Time and resource constraints precluded multiple translations and back translations. Step 1 of the framework took about three months. The turnaround time for one translation and one back translation (Steps 2–5) of the intervention was four months. The turnaround time for the remaining six steps was two months. Also, due to considerable scheduling challenges, the two panels of experts never met as a group. Instead, the first and fourth authors identified areas of consensus across panel members and incorporated recommended changes into the materials at each step of the process. In addition, experiential equivalence in the language adaptation was limited to experiences that did not change the content or presentation of the intervention.

The language adaptation of interventions is not a panacea that will independently address health disparities; there are multiple factors that contribute to disparities in the provision and receipt of health care among ethnic and racial minority groups. However, given the large percentage of foreign-born adults, and children to a lesser extent, who are not English-proficient and given that language barriers are a persistent contributor to service inequities, language adaptation provides the practitioner and the researcher with materials and language to facilitate the delivery of services to underserved and poorly served populations. To this end, we hope that the PIPFLA will serve as a guide for the language adaptation of other interventions, or as the first phase in the cultural adaptation of an intervention with the ultimate goal of reducing health disparities by providing information and treatment that are delivered in clients’ native language.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Jacobita Alonso, Alexander Ayala, Paul Cella, Rosario Guereca, José Mosqueda, Liliana Ramirez Pedraza, Melissa Santana Rivera, and Malilia Santiago Nuñez.

Funding

The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The primary support for this article was provided by a National Institute of Mental Health Grant, K23 MH083049 (Ané M. Maríñez-Lora, principal investigator).

Author Biographies

Ané M. Maríñez-Lora is a research assistant professor in the Institute for Juvenile Research at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research focuses on mental health services research with underserved populations, cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions for Latino immigrant children and families, parental school involvement, and the use of evidence-based practices by community-based clinicians and teachers.

Maya Boustani is an advanced doctoral candidate in the clinical science in child and adolescent psychology program at Florida International University. Her research focuses on the prevention of adolescent risky behaviors among low-income, minority youth, including substance abuse, juvenile justice, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and pregnancy prevention through community-based research. Her work also focuses on actively collaborating with community partners to enhance adolescents’ outcomes.

Cristina T. del Busto is an advanced doctoral candidate in the clinical science child and adolescent psychology program at Florida International University. Her research interests include youth anxiety disorders, culturally competent assessment and treatment of ethnic minority youth, and the role of culture in the development and treatment of anxiety. Her work also focuses on mental health disparities and ways to increase the availability of services to ethnic minorities.

Christine Leone is an advanced doctoral candidate at the School of Social Service Administration at the University of Chicago. Her research pertains to Latino families, children, and undocumented immigration status. Currently, her work is focused on undocumented pregnant women and their access to formal and informal sources of support to make ends meet during pregnancy and the post-partum period.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Language adaptation is preferred over the term translation. Adaptation of an intervention takes place on a continuum from no adaptation to adaptation of most or all content. Language adaptation generally includes more than literal translation and is typically one of the first stages on this continuum.

References

- Alegría M, Vila D, Woo M, Canino G, Takeuchi D, Vera M, …Shrout P (2004). Cultural relevance and equivalence in the NLAAS instrument: Integrating etic and emic in the development of cross-cultural measures for a psychiatric epidemiology and services study of Latinos. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13, 270–288. doi: 10.1002/mpr.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer AM, Chen C-N, & Alegría M (2010). English language proficiency and mental health service use among Latino and Asian Americans with mental disorders. Medical Care, 48, 1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f80749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JJ, So CYC, Jensen PS, Krispin O, El Din AS, & Integrated Services Program Task Force. (2006). Development of adaptable and flexible treatment manuals for externalizing and internalizing disorders in children and adolescents. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatría, 28(1), 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, & Ferraz MB (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25, 3186–3191. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behling O, & Law KS (2000). Translating questionnaires and other research instruments: Problems and solutions: Vol. 133 Quantitative applications in the social sciences. Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G (2006). Intervention development and cultural adaptation research with diverse families. Family Process, 45, 143–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00087.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal G, & Scharró-del-Río MR (2001). Are empirically supported treatments valid for ethnic minorities? Toward an alternative approach for treatment research. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 328–342. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1999). Emics and etics: A symbiotic conception. Culture & Psychology, 5, 165–171. doi: 10.1177/1354067X9952004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borrego J, Anhalt K, Terao SY, Vargas EC, & Urquiza AJ (2006). Parent-child interaction therapy with a Spanish-speaking family. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 13, 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo M, Woodbury-Fariña M, Canino GJ, & Rubio-Stipec M (1993). The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 17, 329–344. doi: 10.1007/BF01380008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaño MT, Biever JL, González CG, & Anderson KB (2007). Challenges of providing mental health services in Spanish. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38, 667–673. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.667 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M Jr., & Holleran Steiker LK (2010). Issues and challenges in the design of culturally adapted evidence-based interventions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-033109-132032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JI, & Flaskerud JH (2008). Lost in translation: Adapting a stress intervention program for use with an ethnic minority population. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29, 1237–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado A, Castillo SD, Maero F, Lejuez CW, & Macpherson L (2014). Pilot of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression in Latinos with limited English proficiency: Preliminary evaluation of efficacy and acceptability. Behavior Therapy, 45, 102–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook B, McGuire T, & Miranda J (2007). Measuring trends in mental health care disparities, 2000–2004. Psychiatric Services, 58, 1533–1540. Retrieved from 10.1176/ps.2007.58.12.1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’angelo EJ, Llerena-Ouinn R, Shapiro R, Colon F, Rodriguez P, Gallagher K, & Beardslee W (2009). Adaptation of the Preventive Intervention Program for depression for use with predominantly low-income Latino families. Family Process, 48, 269–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, & Lin J (2013). Parallel processing of the target language during source language comprehension in interpreting. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 16, 682–692. Retrieved from 10.1017/S1366728913000102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Arriaga X, Begle AM, & Longoria Z (2010). “When will your program be available in Spanish?” Adapting an early parenting intervention for Latino families. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 17, 176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkoboni D, Ozanne-Smith J, Rouxiang C, & Winston FK (2010). Cultural translation: Acceptability and efficacy of a U.S.-based injury prevention intervention in china. Injury Prevention, 16, 296–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P, Doescher MP, & Saver BG (2002). Disparities in health care by race, ethnicity, and language among the insured: Findings from a national sample. Medical Care, 40, 52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Julion W, Garvey C, Breitenstein S, Maríñez-Lora AM, & Ordaz I (2011). El programa para padres de Chicago: Manual para líderes de grupo [Spanish adaptation of the Chicago Parent Program’s Group Leader manual] (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: Rush University College of Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Gross D, Julion W, Garvey C, Maríñez-Lora AM, & Ordaz I (2008). El programa para padres de Chicago de la Universidad de Rush: Manual para líderes de grupo [Spanish adaptation of the Chicago Parent Program]. Chicago, IL: Rush University College of Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Martins S, Hatzenbuehler M, Blanco C, Bates L, & Hasin DS (2012). Mental health service utilization for psychiatric disorders among Latinos living in the United States: The role of ethnic subgroup, ethnic identity, and language/social preferences. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47, 383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0323-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopelowicz A (1998). Adapting social skills training for Latinos with schizophrenia. International Review of Psychiatry, 10, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 13, 295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lintvedt OK, Griffiths KM, Eisemann M, & Waterloo K (2013). Evaluating the translation process of an Internet-based self-help intervention for prevention of depression: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(1), 43–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matías-Carrelo LE, Chávez LM, Negrón G, Canino G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, & Hoppe S (2003). The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of five mental health outcome measures. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 27, 291–313. doi: 10.1023/A:1025399115023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Torres R, Santiago R, Jurado M, & Rodríguez I (2006). Adaptation of parent-child interaction therapy for Puerto Rican families: A preliminary study. Family Process, 45, 205–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Lau AS, & Chavez G (2005). The GANA program: A tailoring approach to adapting parent-child interaction therapy for Mexican Americans. Education & Treatment of Children, 28(2), 111–129. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, & Forehand RL (2003). Helping the noncompliant child: Family-based treatment for oppositional behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega E, Giannotta F, Latina D, & Ciairano S (2012). Cultural adaptation of the strengthening families program 10–14 to Italian families. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41, 197–212. [Google Scholar]

- Patten E (2012). Statistical portrait of the foreign-born population in the United States, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. [Google Scholar]

- Pekmezi D, Dunsiger S, Gans K, Bock B, Gaskins R, Marquez B, …Marcus B. (2012). Rationale, design, and baseline findings from Seamos Saludables: A randomized controlled trial testing the efficacy of a culturally and linguistically adapted, computer- tailored physical activity intervention for Latinas. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 33, 1261–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saechao F, Sharrock S, Reicherter D, Livingston JD, Aylward A, Whisnant J, …Kohli S. (2012). Stressors and barriers to using mental health services among diverse groups of first-generation immigrants to the United States. Community Mental Health Journal, 48, 98–106. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9419-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentell T, Shumway M, & Snowden L (2007). Access to mental health treatment by English language proficiency and race/ethnicity. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22, 289–293. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0345-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, & Erikson P (2005). Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: Report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health, 8, 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]