Abstract

Background

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has rapidly become a global pandemic, with over 1.8 million confirmed cases worldwide to date. Preliminary reports suggest that the disease may present in diverse ways, including with neurological symptoms, but few published reports in the literature describe seizures in patients with COVID-19.

Objective

The objective of the study was to characterize the risk factors, clinical features, and outcomes of seizures in patients with COVID-19.

Methods

This is a retrospective case series. Cases were identified through a review of admissions and consultations to the neurology and neurocritical care services between April 1, 2020 and May 15, 2020.

Setting

The study setting was in a tertiary care, safety-net hospital in Boston, MA.

Participants

Patients presenting with seizures and COVID-19 during the study period were included in the study.

Results

Seven patients met inclusion criteria (5 females, 71%). Patients ranged in age from 37 to 88 years (median: 75 years). Three patients had a prior history of well-controlled epilepsy (43%), while 4 patients had new-onset seizures, including 2 patients with prior history of remote stroke. Three patients had no preceding symptoms of COVID-19 prior to presentation (57%), and in all cases, seizures were the symptom that prompted presentation to the emergency department, regardless of prior symptoms of COVID-19.

Conclusions

Provoking factors for seizures in patients with COVID-19 may include metabolic factors, systemic illness, and possibly direct effects of the virus. In endemic areas with community spread of COVID-19, clinicians should be vigilant for the infection in patients who present with seizures, which may precede respiratory symptoms or prompt presentation to medical care. Early testing, isolation, and contact tracking of these patients can prevent further transmission of the virus.

Keywords: Epilepsy, COVID-19, Neuroinfectious diseases, SARS-CoV-2, Seizure

1. Background

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has rapidly become a global pandemic, with over 5 million confirmed cases worldwide to date [1]. Early diagnosis is critical to the consideration of specific treatment and implementation of appropriate infection control measures. However, preliminary reports suggest that the disease may present in diverse ways, and diagnosis may be delayed in atypical cases.

In addition to respiratory symptoms, COVID-19 has been described in association with a host of neurologic complications, including acute cerebrovascular events, impaired consciousness, and skeletal muscle injury [2,3], but minimal literature exists on seizures in patients with COVID-19 [[4], [5], [6]]. Here, we describe the clinical course of 7 patients who presented with seizures as an early manifestation of COVID-19.

2. Methods

This observational case series was approved by the Boston University Medical Center IRB. Cases were identified through a review of admissions and consultations to the neurology and neurocritical care services between April 1, 2020 and May 15, 2020.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

Of 1043 admitted patients with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19, 7 patients (0.7%) presented with seizures (5 females, 71%), ranging in age from 37 to 88 years (median: 75 years) (Table 1 ). Three patients had a prior history of well-controlled epilepsy (43%) with a last seizure between 10 and 17 months prior to presentation, including one with poststroke epilepsy and one patient with epilepsy following cardiac arrest. Four patients had new-onset seizures, including 2 patients with prior history of remote stroke, one patient with Parkinson's disease, and one with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Home antiepileptic medications included valproic acid, phenytoin, levetiracetam, and zonisamide prescribed for epilepsy, and lorazepam prescribed for anxiety in one patient without epilepsy.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and pertinent laboratory and radiographic studies (reference ranges are included in square brackets, HD = hospital day, AED = antiepileptic drug, MCA = middle cerebral artery, GTC = generalized tonic–clonic seizure, NCHCT: noncontrasted head computed tomography, CTA = computed tomography angiogram, EEG = electroencephalography, LEV = levetiracetam, PHT = phenytoin, LOR = lorazepam, MDZ = midazolam, ZNS = zonisamide, PPF = propofol, LCM = lacosamide, GRDA = generalized rhythmic delta activity, PCR = polymerase chain reaction).

| Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 | Patient 6 | Patient 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), gender | 75, male | 50, male | 88, female | 88, female | 37, female | 81, female | 61, female |

| History of prior epilepsy | Y, last seizure 17 months prior to presentation | Y, last seizure 10 months prior to presentation | N | N | N | Y, last seizure 15 months prior to presentation | N |

| Home AEDs (medications with subtherapeutic levels indicated in bold) | LEV, PHT | VPA, PHT, LEV | N/A (prescribed LOR for anxiety) | N/A | N/A | LEV, ZNS | N/A |

| Additional prior seizure risk factors | Remote left MCA infarct, traumatic brain injury | Subtherapeutic VPA levels | Idiopathic Parkinson's disease | Remote left MCA infarct | Remote infarct secondary to sickle cell disease, developmental delay | History of cardiac arrest | End-stage renal disease on hemodialysis, intellectual disability |

| Presenting symptoms of COVID-19 | Fatigue, coffee-ground emesis | Cough, shortness of breath | None | None | Dry cough, ageusia, fatigue | None | Cough, fatigue, fever |

| Duration of COVID-19 symptoms at the time of seizure (days) | 2 | 7 | N/A | N/A | 5 | N/A | 18 |

| Seizure semiology on presentation | GTC | GTC | GTC | GTC | Focal, unawareness, leftward gaze deviation, and tonic right arm movement followed by postictal confusion | Rightward gaze deviation, rightward head version, rhythmic left arm and leg twitching | GTC |

| Number of seizures and seizure duration | One, unknown duration | One, 20 min | Two, lasting 1–2 min | One, lasting 1 min | Two, lasting 3–5 min | Three, lasting 3–5 min | Multiple focal onset events lasting 3–5 min |

| Treatments administered for seizures | LOR, LEV, PHT | MDZ, VPA | LOR, LEV | LEV | LEV | MDZ, LEV, and ZNS | LEV, LCM, PPF, MDZ |

| Other neurologic deficits | Aphasia, right gaze preference, right-sided hemiplegia; (resolved to baseline aphasia and right hemiparesis) | Leftward gaze deviation and right-sided hemiparesis (resolved to baseline nonfocal examination) | Leftward gaze deviation, increased tone in left leg compared with right leg (resolved to baseline examination with extrapyramidal findings) | Aphasia, right-sided hemiparesis (baseline examination) | Spastic left hemiparesis and left nasolabial fold flattening (baseline examination) | Generalized weakness with no lateralizing sign (baseline examination) | Rightward gaze deviation (resolved) |

| Brain imaging findings on admission | NCHCT with encephalomalacia in left MCA territory, consistent with prior infarct | NCHCT: no acute abnormalities CTA head and neck: no large-vessel occlusion | NCHCT: no acute abnormalities | NCHCT with encephalomalacia in left frontal, parietal, and temporal lobes | NCHCT: confirmed previously known bifrontal and left temporal encephalomalacia | CTA head and neck: no large-vessel occlusion | CTA head and neck: no large-vessel occlusion CT venogram: No sinus thrombosis MRI brain with and without contrast: extensive leukoencephalopathy, gyriform diffusion restriction (Fig. 1) |

| EEG findings | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | Moderately slow background, frequent sharp waves and focal epileptiform discharges (right parieto-occipital region), occasional independent sharp waves (right posterior temporal region), frequent bifrontal generalized sharp waves with triphasic morphology | Moderate to severe encephalopathy, with frequent short runs of GRDA |

| Cerebrospinal fluid analysis: protein [15–45 mg/dL], glucose [40–70 mg/dL] | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | Not obtained | < 1 total nucleated cell/μL, 2 red blood cells/μL, protein 19 mg/dL, glucose 92 mg/dL; negative meningitis and encephalitis PCR panel |

| Illness severity | Intubated, required ICU care | Intubated, required ICU care | Hospitalized, no intubation or ICU care required | Hospitalized, no intubation or ICU care required | Hospitalized, no intubation or ICU care required | Intubated, required ICU care | Intubated, required ICU care |

| Temperature °F, initial (max) |

98.4 (102.2) | 99.3 (100.6) | 103.4 (103.4) | 98 (99.1) | 98 | 99.2 (100.6) | 100.6 (102.9) |

| White blood cell count K/μL, initial (nadir) [4.0–11.0 K/μL] |

8.8 (1.6) | 20.2 (13.2) | 6.3 (5.6) | 4.7 (4.7) | 4.9 | 6.7 (5.0) | 5.9 (5.1) |

| Absolute lymphocyte count K/μL, initial (nadir) [1.1–3.5 K/μL] |

1.3 (0.3) | 11.9 (3.7) | 0.4 (0.2) | 1.1 (1.1) | 2.5 | 1.9 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.2) |

| D-dimer ng/mL, initial (peak) [< 243 ng/mL] |

912 (1595) | 1079 (2013) | 752 (823) | 303 (303) | 1495 | 260 (1032) | 915 (4186) |

| CRP mg/L, initial (peak) [0–5 mg/L] |

67.2 (353.2) | 6.4 (198) | 188 (188) | Not obtained | 5.6 | 302.6 (441.5) | 27.3 (382.8) |

| Ferritin ng/mL, initial (peak) [10–109 ng/mL] |

126 (1969) | 175 (260) | 644 (720) | 183 (183) | 302 | 860 (907) | 2754 (17,178) |

| Fibrinogen mg/dL, initial (peak) [180–460 mg/dL] |

190 (> 800) | 304 (648) | 752 (795) | 624 (624) | 277 | 480 (> 800) | 453 (590) |

| Procalcitonin ng/mL, initial (peak) [< 0.50 ng/mL] |

2.6 (11.9) | 0.03 (0.17) | 1.6 (11.6) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.13 | 0.86 (0.86) | 0.25 (2.13) |

| Additional laboratory derangements | Hyponatremia (108 mEq/L) | Subtherapeutic VPA level ( ) | Elevated blood urea nitrogen (67 mg/dL) | None | None | None | Baseline renal dysfunction |

| Chest X-ray | HD1: Increased interstitial markings. HD2: New hazy airspace opacities. | HD1: Left basilar airspace opacities. HD3: Resolved. | HD1: Bilateral lower lung hazy opacities. | HD1: Subsegmental atelectasis in left lung base, no focal consolidation. | HD1: Curvilinear bibasilar opacities suggestive of scarring. | HD1: Opacity in left lung base. |

HD1: Focal nodular density. |

| Chest CT | HD1: Dense consolidation with air bronchograms HD2: Dense dependent consolidative opacities suggestive of worsening pneumonitis or pneumonia. | Not obtained. | Not obtained. | Not obtained. | Not obtained. | Not obtained. | HD8: Bilateral ground-glass/consolidative opacities, worse in lung bases. |

| Outcome at the time of manuscript submission | Deceased | Discharged home, no recurrent seizures | Discharged to nursing home where she lives at baseline, no recurrent seizures | Discharged home, no recurrent seizures | Discharged home, no recurrent seizures | Extubated, transferred to floor, awaiting rehab, no recurrent seizures | Remains intubated on pressure support |

3.2. Features of COVID-19

Presenting symptoms of COVID-19 included cough, fatigue, ageusia, fever, shortness of breath, and emesis in 4 patients (57%). Symptoms began 2–18 days prior to presentation with seizure. Three patients had no preceding symptoms of COVID-19 prior to presentation (43%). In all cases, COVID-19 was identified based on characteristic clinical features and positive nasopharyngeal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for SARS-CoV-2. Fever was noted in 5 cases (71%), and lymphopenia was noted in 4 (57%). D-dimer, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were elevated in all 7 patients. Chest imaging was abnormal in all 7 patients, and 4 patients (57%) had severe respiratory failure requiring intubation. One patient is deceased, while a second patient remains intubated, requiring ongoing respiratory support. The remaining 5 patients (71%) have been discharged from the hospital and returned to baseline neurologic function without recurrent seizures.

3.3. Seizure onset and semiology

In all 7 patients, seizures prompted presentation to the emergency department in spite of prior symptoms of COVID-19. Five patients (71%) had generalized tonic–clonic seizures, while 2 patients had focal seizures characterized by gaze deviation, head version, and unilateral motor symptoms. Four patients developed focal postictal deficits that subsequently resolved.

3.4. Imaging and CSF findings

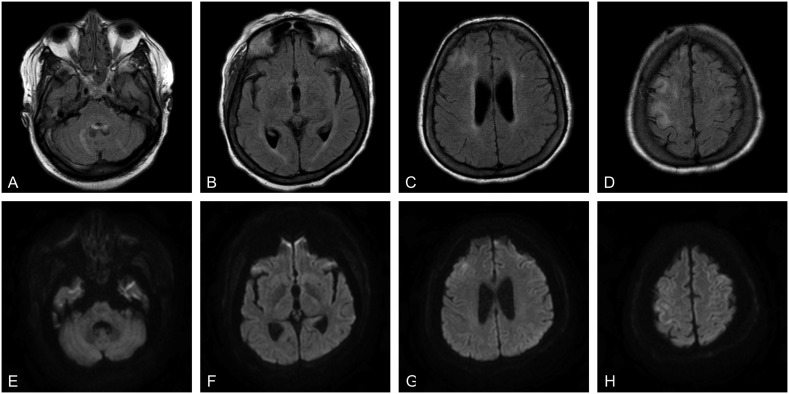

Noncontrast enhanced head computed tomography (CT) was obtained in all cases and showed no new abnormalities in any of the cases. Arterial or venous vessel imaging was obtained in 3 cases (43%) without cerebral venous sinus thrombosis or large-vessel occlusion in any of the cases. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain with and without contrast (Fig. 1 ) was obtained in just one case and revealed gyriform restricted diffusion in the cortex of the bilateral frontal lobes and extensive abnormal fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) signal hyperintensity involving the subcortical U-fibers, periventricular white matter, bilateral cerebellar white matter, and bifrontal cortices. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) studies were obtained for one patient (7) and demonstrated a normal protein and < 1 nucleated cell/μL.

Fig. 1.

Axial brain MRI for patient 7. A–D: T2-weighted fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences revealed prominent FLAIR hyperintensity involving the right frontal lobe and bilateral cerebellar hemispheres. E–G: Diffusion-weighted images revealed diffusion restriction involving the right frontal lobe without associated diffusion restriction of the cerebellum.

3.5. Electrographic findings

Twenty-four-hour electroencephalography (EEG) was obtained in 2 cases. One patient (patient 6) had moderately slow background activity, with frequent sharp waves and focal epileptiform discharges in the right parieto-occipital region and occasional independent sharp waves in the right posterior temporal region. There were also frequent generalized sharp waves with triphasic morphology and right greater than frontal predominance. The second patient (patient 7) had moderate to severe encephalopathy, with frequent short runs of generalized rhythmic delta activity (GRDA). Her clinical status epilepticus had resolved by the time of EEG.

4. Discussion

Although systemic infection may be a trigger for breakthrough seizures in patients with a history of epilepsy, to date, few cases in the literature describe seizures in patients with COVID-19, including one in a critically ill patient, one in a patient with a history of epilepsy after prior viral encephalitis, and 2 in patients with a COVID-19 encephalitis based on SARS-CoV-2 detection in the CSF [1,2,7,8]. One large cohort from China's Hubei Province found that of 304 patients with COVID-19, including 84 with brain insults or metabolic imbalances, none had seizures and 2 had “seizure-like symptoms” in the setting of hypocalcemia, concluding that the virus does not carry an increased risk of seizure [5]. Notably, no patients with underlying epilepsy were included in the cohort.

By contrast, the 7 patients here presented with either new-onset or breakthrough seizure as an early symptom of COVID-19. Although 4 of the patients presented had preceding respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms, 3 had no preceding symptoms to suggest a diagnosis of COVID-19. In all cases, seizure was the symptom that prompted presentation to the hospital. In endemic areas with community spread of COVID-19, clinicians should be vigilant for the infection in patients who present with seizures, as it may prompt presentation to the hospital in patients with or without preceding mild systemic symptoms, and early testing, isolation, and contact tracking can prevent further transmission of the virus.

Three of the patients described presented with significant metabolic derangements. One presented with hyponatremia, while the second was uremic, and a third developed seizures shortly after undergoing hemodialysis. Preliminary reports suggest that hyponatremia and early renal failure may be common features of COVID-19 [3]. Hyponatremia, uremia, and related metabolic derangements can both cause encephalopathy and lower the seizure threshold in susceptible patients. These cases demonstrate that COVID-19 should be considered in patients who present with seizure in the setting of metabolic derangements. In one case, a reactive leukocytosis in the setting of seizure also masked an underlying leukopenia that might otherwise have prompted testing for SARS-CoV-2 earlier in the course.

Three patients had a prior history of well-controlled epilepsy, while 4 patients had new-onset seizures, including 2 patients with prior history of remote stroke. In one case, valproic acid levels were found to be subtherapeutic, which may have precipitated seizures in conjunction with infection. Although the etiology for subtherapeutic levels was unclear, reports from prior coronavirus epidemics suggested that breakthrough seizures may occur at higher rates in the pandemic setting, as patients may avoid hospitals and pharmacies and have more difficulty obtaining their prescribed antiepileptic therapies [4]. Among patients with underlying epilepsy, respiratory infections can also be a frequent precipitant of breakthrough seizures, particularly in children [5].

Ancillary testing was limited in all cases, in part because of concerns regarding viral transmission to healthcare workers and other patients. Just one patient, who presented with status epilepticus following hemodialysis, had a brain MRI during her hospitalization. This study was markedly abnormal, with gyriform diffusion restriction and extensive leukoencephalopathy. Etiologic considerations included sequelae of her prolonged status epilepticus or possible viral encephalitis, although CSF studies showed no evidence of inflammation or infection. Electroencephalography was obtained in just 2 cases and revealed epileptiform discharges in one case and findings suggestive of encephalopathy in the other.

Experience with prior pandemic ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses suggests that both new-onset and breakthrough seizures may be a common presenting manifestation of viral illness [9]. In some cases, these may be a manifestation of encephalitis, while in others, they may reflect metabolic derangements, severe systemic illness, an inability to obtain medications, or gastrointestinal symptoms impeding absorption of oral medications. Because of prior reports regarding thromboembolic and hemorrhagic events in patients with COVID-19, seizures may also represent the presenting symptom of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis or intracerebral hemorrhage in some cases. Regardless of etiology, COVID-19 should be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients presenting with seizures during the pandemic, as early consideration may lead to earlier detection and appropriate precautions.

Ethical publication statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Declaration of competing interest

All authors report no disclosures in association with this work.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgement

Drs. Anand is supported by a 2020 Grinspoon Grant. Dr. Abdennadher is supported by a 2020 Grinspoon Grant.

References

- 1.WHO . 2020. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-61. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao L., Wang M., Chen S., He Q., Chang J., Hong C. Neurological manifestations of hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective case series study. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li M. Acute cerebrovascular disease following COVID-19: a single center, retrospective, observational study. Lancet. 2020;19 doi: 10.1136/svn-2020-000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moriguchi T., Harii N., Goto J., Harada D., Sugawara H., Takamino J. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaddumukasa M., Kaddumukasa M., Matovu S., Katabira E. The frequency and precipitating factors for breakthrough seizures among patients with epilepsy in Uganda. BMC Neurol. 2013;13:182. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu L., Xiong W., Liu D., Liu J., Yang D., Li N. New-onset acute symptomatic seizure and risk factors in corona virus disease 2019: a retrospective multicenter study. Epilepsia. 2020;61(6):e49–e53. doi: 10.1111/epi.16524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lau K.-K., Yu W.-C., Chu C.-M., Lau S.-T., Sheng B., Yuen K.-Y. Possible central nervous system infection by SARS coronavirus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:342–344. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vollono C., Rollo E., Romozzi M., Frisullo G., Servidei S., Borghetti A. Focal status epilepticus as unique clinical feature of COVID-19: a case report. Seizure. 2020;78:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asadi-Pooya A.A. Seizures associated with coronavirus infections. Seizure. 2020;79:49–52. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]