Abstract

Purpose

The COVID-19 outbreak is affecting people worldwide. Many infected patients have respiratory involvement that may progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome. This pilot study aimed to evaluate the clinical efficacy of low-dose whole-lung radiation therapy in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Methods and Materials

In this clinical trial, conducted in Iran, we enrolled patients with COVID-19 who were older than 60 years and hospitalized to receive supplementary oxygen for their documented pneumonia. Participants were treated with whole-lung irradiation in a single fraction of 0.5 Gy plus the national protocol for the management of COVID-19. Vital signs (including blood oxygenation and body temperature) and laboratory findings (interleukin-6 and C-reactive peptide) were recorded before and after irradiation.

Results

Between May 21, 2020 and June 24, 2020, 5 patients received whole-lung irradiation. They were followed for 5 to 7 days to evaluate the response to treatment and toxicities. The clinical and paraclinical findings of 4 of the 5 patients (patient 4 worsened and died on day 3) improved on the first day of irradiation. Patient 3 opted out of the trial on the third day after irradiation. The mean time to discharge was 6 days for the other 3 patients. No acute radiation-induced toxicity was recorded.

Conclusions

With a response rate of 80%, whole-lung irradiation in a single fraction of 0.5 Gy had encouraging results in oxygen-dependent patients with COVID-19 pneumonia.

Introduction

Since the end of 2019, the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been a major health issue all over the world. It is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and has led to more than 500,000 deaths as of July 2020, with an estimated crude mortality rate of 3% to 4%.1, 2, 3 Four phases have been proposed for the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2, including suppression of interferon type 1 production, blockage of interferon type 1 signaling, massive inflammatory response (so-called cytokine storm), and immune exhaustion.4 The lethality of COVID-19 mainly stems from cytokine storm–induced thrombotic dysregulation and multiorgan failure.5 During the cytokine storm, monocytes and macrophages mainly recruit, which may explain elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6).5 Suppression of cytokine storm can potentially reduce the morbidity and mortality of COVID-19. Recently, the preliminary results of the RECOVERY trial demonstrated that dexamethasone 6 mg given once daily for up to 10 days significantly reduced the 28-day mortality among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia receiving invasive mechanical or noninvasive ventilation.6 Experimental studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effect of low-dose radiation therapy (LD-RT) by modulating the function of a variety of inflammatory cells, including endothelial cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and macrophages.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Therefore, LD-RT is considered to afford an opportunity to block the deadly cytokine storm and save patients’ lives. Herein, we report the outcomes of the first 5 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who were treated with low-dose whole-lung irradiation at Imam Hossein Educational Hospital, Tehran, Iran.

Methods and Materials

Ethical consideration

Before commencing the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethical Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Ethical code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1399.073). Before assigning the patients to radiation therapy, written informed consent was obtained.

Trial design and participants

This pilot clinical trial was conducted at Imam Hossein Educational Hospital to examine the safety and efficacy of single-fraction low-dose whole-lung irradiation in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia (Clinical Trial Registration Number NCT04390412). Individuals were enrolled who were more than 60 years old who had clinical manifestations of COVID-19 with a positive polymerase chain reaction of the nasopharyngeal swab, antibody test, or radiographic pneumonic consolidations that required oxygen supplementation (with SpO2 ≤93% and/or PaO2/FiO2 ≤300 mm Hg). For patients who had stable vital signs, we used SpO2 to estimate PaO2.13 A designated research collaborator used a pulse oximeter (Riester, Germany) to measure SpO2 within 1 hour before patients were transported to the radiation therapy department. The patients were kept on room air for 3 minutes to record the SpO2 at the resting position. After irradiation, SpO2 was recorded once a day between 8 and 10 a.m. by the same researcher using the same protocol.

The exclusion criteria were patients with hemodynamic instability or requiring mechanical ventilation, a history of malignancy or heart failure, contraindication for radiation therapy, septic shock or end-organ failure, or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (with PaO2/FiO2 ≤100 mm Hg).

The primary objectives included change from baseline blood oxygenation (in terms of O2 saturation), the number of hospital/intensive care unit stay days, and the number of intubations performed after radiation treatment. The secondary objectives were changes in laboratory results (including C-reactive peptide [CRP] and IL-6). Clinical recovery was defined as the first day a patient was discharged or weaned from supplemental oxygen with SpO2 ≥93% in room air. Five of 40 eligible patients signed the consent form and entered the study between May 2020 and June 2020. Almost all (33 of 35) patients who declined to receive low-dose whole-lung irradiation were worried about radiation-induced malignancy. The other 2 patients were pessimistic about the efficacy of irradiation. This clinical trial was approved by the institutional review board.

Radiation therapy and follow-up

The treatment protocol was low-dose whole-lung irradiation in conjunction with the standard national guideline for the management of COVID-19. So far, 7 editions of the national protocol for the management of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia have been published. The sixth and seventh edition were used for our trial. Its principles to manage patients with moderate pulmonary involvement (SpO2 ≤93% on room air or respiratory rate >30) were as follows: (1) supplemental oxygen (preferably) via high-flow nasal cannula, (2) unfractionated heparin 5000 units subcutaneously every 8 hours or enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously once daily, (3) antibiotics (if clinically indicated; eg, community-acquired pneumonia), (4) basic supportive care, (5) careful monitoring of patients for clinical indices, and (6) dexamethasone 8 mg daily for up to 10 days (at the physician’s discretion).14 , 15

All participants were allocated to receive single-fraction 0.5 Gy to the whole lungs. Radiation therapy planning was done on patients’ diagnostic computed tomography (CT) scans with patients in a supine position using a multislice spiral CT scanner without intravenous contrast. Both lungs were defined as the clinical target volume, and 1 cm was added to create planning target volume (including the internal target volume). Treatment planning was done with ISOgray treatment planning system (DOSIsoft SA), which calculates dose using the collapsed cone algorithm (with heterogeneity correction). The prescribed dose to the treatment isocenter (located in the middle of mediastinum) was 0.5 Gy delivered via 2 opposed anteroposterior and posteroanterior open portals. At least 95% and 100% of the prescribed dose covered the planning target volume and clinical target volume, respectively. Considering the extremely low dose prescribed, no restriction was considered for the hot points and the organs at risk, including heart, liver, stomach, esophagus, and thyroid gland. The Varian Clinac 2300 CD with 18 MV photon beams, not equipped with multileaf collimator, was used to deliver the dose. To decrease the treatment time, no block was considered for the thyroid gland; however, for the last 3 patients, the radiation oncologist placed the midline block on the optical field over the upper part of the portals (matched with the lower neck) before the patient entered the treatment room to better protect the thyroid gland. The correction was done for block tray in the fourth and fifth patients for both portals.

Vital signs, consciousness, performance status, blood oxygenation, CRP, and IL-6 were assessed at baseline and then daily after the irradiation. The body temperature of patients was measured by the ward nurse at 6:00 a.m. using tympanic membrane thermometry.

Results

From May 21, 2020 to June 24, 2020, 40 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia were asked to participate in the trial. Five (4 male and 1 female) signed the consent form and received low-dose whole-lung irradiation at the Clinical Oncology Department of Imam Hossein Hospital. All participants except 1 (patient 3) were positive on polymerase chain reaction based on a nasopharyngeal swab. Patient 3 was admitted for a loss of consciousness, typical findings of COVID-19 pneumonia in a chest CT scan, and an elevated CRP level.

The baseline characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1 . The patients were between 60 and 84 years old (mean: 71.8 years). All patients had comorbidities, including hypertension in 3 patients, a history of ischemic heart disease in 2 patients, and heart failure in 1 patient. At the time of admission, the median Karnofsky performance score and Glasgow Coma Scale were 60 (range, 50-80) and 15 (range, 10-15), respectively. LD-RT was delivered 1 to 3 days after the admission day (median 2 days).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Male | Male |

| Age, y | 60 | 69 | 82 | 84 | 64 |

| Comorbidities | Heart failure | HTN, IHD | IHD | HTN | HTN |

| KPS at admission | 80 | 80 | 60 | 50 | 60 |

| GCS at admission | 15 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 15 |

| Presenting symptom(s) | Shortness of breath | Fever and cough | Depressed level of consciousness | Fever and cough | Shortness of breath and cough |

| Vital signs at admission | |||||

| Pulse rate (per min) | 75 | 88 | 90 | 82 | 90 |

| Respiratory rate (per min) | 12 | 16 | 20 | 12 | 15 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 110 | 130 | 110 | 140 | 120 |

| Temperature (°C) | 37.5 | 38.1 | 37.6 | 37 | 39 |

| O2 saturation (%) | 87 | 86 | 75 | 89 | 74 |

| P/F ratio | 192 | 126.7 | 160 | 101.4 | 110 |

| Time from onset of symptoms to RT, d | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Diagnosis of COVID-19 | Clinical findings and PCR | Clinical findings and PCR | Clinical and imaging findings | Clinical findings and PCR | Clinical and imaging findings and PCR |

| O2 supplementation | Facial mask | Nasal cannula | Facial mask with reservoir bag | Facial mask | Facial mask with reservoir bag |

| Length of stay at hospital after RT, d | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Outcome | Discharged | Discharged | Opted out of trial | Died | Discharged |

Abbreviations: GCS = Glasgow coma scale; HTN = hypertension; IHD = ischemic heart disease; KPS = Karnofsky performance scale; PCR = polymerase chain reaction; P/F ratio = PaO2/FiO2; RT = radiation therapy.

Of the 5 initially enrolled patients, 4 (80%) showed initial improvement in O2 saturation and body temperature within 1 day after irradiation. Of these, 1 patient (patient 3) chose to opt out of the trial on the third day of irradiation. The mean time to discharge was 6 days for 3 patients (patients 1, 2, and 5). Patient 4’s O2 saturation and body temperature began to deteriorate on the first day of irradiation, and the patient died on the third day after irradiation.

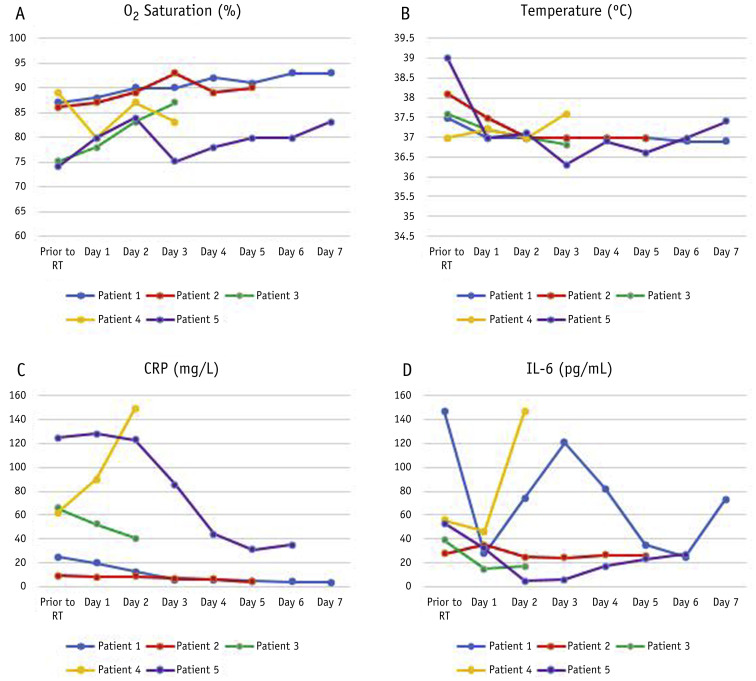

The laboratory findings (IL-6 and CRP) were in line with the clinical findings. Regarding IL-6, although a fluctuation was documented in patient 1, the overall trendline was as per clinical findings. Figure 1 demonstrates the change in clinical and laboratory findings after irradiation. During the observation, no acute skin, cardiac, pulmonary, or gastric toxicities were detected. Patient 5 experienced SpO2 ≥94% while receiving O2 but 83% ≤ SpO2 < 87% in room air. At the discretion of his physician and due to the limitation of ventilation facilities, he was discharged on the seventh day after irradiation with medical advice to receive O2 at home.

Fig. 1.

Evolution in time of (A) O2 saturation, (B) body temperature, (C) c-reactive peptide, and (D) IL-6 in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia after single-fraction whole-lung irradiation.

Discussion

Incidentally, none of the patients in our trial received dexamethasone, remdesivir, (hydroxy)chloroquine, or macrolides. Therefore, the effect of these factors was omitted in the findings. This pilot study had several important findings. First, for oxygen-dependent patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, whole-lung irradiation had a response rate of 80% in terms of clinical and paraclinical findings. Second, not including the 1 patient who opted out of the trial, the clinical condition of patients was evaluable in the remaining 4, of whom 3 were able to leave the hospital (1 still on supplemental oxygen) for a clinical recovery rate of 75%. Third, our results showed that LD-RT starts to demonstrate efficacy from the first day of irradiation. Fourth, CRP changes were consistent with the clinical findings; however, IL-6 fluctuated in 1 patient but followed the patient’s clinical condition. This may be due to the short-term release of IL-6 upon irradiation.16 Fifth, despite the clinical efficacy, no acute toxicity was reported with LD-RT.

To the best of our knowledge, 3 other ongoing clinical trials are applying LD-RT in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. The summary of these trials is presented in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Overview of clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of low-dose whole-lung irradiation in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia

| Clinical trial | RESCUE 1-19 | COLOR-19 | Present trial | VENTED |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT number | NCT04366791 | NCT04377477 | NCT04390412 | NCT04427566 |

| Start date | April 29, 2020 | May 6, 2020 | May 15, 2020 | June 11, 2020 |

| Country of origin | United States | Italy | Iran | United States |

| Current status | Preliminary results are published in a non–peer reviewed journal | Recruiting patients | Pilot study (published) | Recruiting patients |

| Participants | ||||

| Sex | Male and female | Male and female | Male and female | Male and female |

| Age, y | ≥18 | ≥50 | >60 | ≥18 |

| Clinical presentation | Receiving O2 with NIV | Receiving O2 with NIV | Receiving O2 with NIV | Receiving O2 with MV |

| No. of participants | 5 | 30 | 5 (for pilot study) | 24 |

| Treatment plan | Single-fraction whole-lung irradiation | Single-fraction whole-lung irradiation | Single-fraction whole-lung irradiation + national guideline | Single-fraction whole-lung irradiation |

| Radiation dose, Gy | 1.5 | 0.7 (on average) | 0.5 (+ an additional 0.5 if needed) | 0.8 |

| Primary objectives | Safety Clinical recovery |

Length of hospital stay No. of ICU admissions |

Change in blood oxygenation Length of hospital/ICU stay |

Mortality rate after 30 d of ICU-based MV initiation |

Abbreviations: ICU = intensive care unit; MV = mechanical ventilation; NIV = noninvasive ventilation.

The only available results are from the RESCUE 1-19 trial that was recently published in a non–peer-reviewed journal.8 The study is summarized in Table 2. In this pilot study, 5 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia received whole-lung irradiation with a single-fraction of 1.5 Gy. Four of the patients recovered rapidly and were weaned from supplemental oxygen at a mean time of 1.5 days. In all patients, no acute toxicity was reported.

Similar findings were reached by our trial in terms of response rate and safety. However, we obtained these results with lower radiation doses. This finding supports the hypothesis that radiation doses as low as 0.5 Gy can modify the immune reaction to COVID-19 pneumonia by activation of macrophages with M2 phenotype.9 We also included the national protocol for the management of COVID-19 in the treatment plan, which may have affected the results. We went beyond the RESCUE 1-19 trial by examining the body temperature, IL-6, and CRP of patients after irradiation.

According to the national protocol for the management of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, patients who had SpO2 <90% using noninvasive ventilation with FiO2 >50% were indicated for intensive care unit admission, intubation, and mechanical ventilation. However, due to the limited ventilation facilities, we had to apply the basic ventilation support with a facial mask ± reservoir bag. This limitation may affect the clinical results of patient 4. We wish to circumvent this effect in the next recruitment of patients by improving the required facilities of our hospital.

Conclusions

Notwithstanding the small sample size, the interim results of the RESCUE 1-19 trial and ours demonstrate that LD-RT may be a successful treatment to save patients with severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Longer follow-up with more patients is needed to confirm this notion. Given the encouraging results of this pilot trial, the Ethical Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences allowed continuation of the trial using 1.0 Gy whole-lung irradiation.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mr Jabbari, MS, Dr Azadeh, MD, Dr Motlagh, MD, Dr Manafi, MD, Dr Haghighi, MD, and Mrs Khoshbakht for their kind support. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the staff of Imam Hossein Hospital, Tehran, and to all physicians and nurses all around the world who are doing their best to treat patients with COVID-19.

Footnotes

Clinical trial registration number: NCT04390412

Disclosures: none.

Data sharing: Research data are stored in an institutional repository and will be shared upon request to the corresponding author

References

- 1.Our World in Data. Mortality risk of COVID-19. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus Available at:

- 2.Shankar A., Saini D., Roy S. Cancer care delivery challenges amidst coronavirus disease–19 (COVID-19) outbreak: Specific precautions for cancer patients and cancer care providers to prevent spread. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21:569–573. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.3.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 46. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200306-sitrep-46-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=96b04adf_4 Available at:

- 4.Taghizadeh-Hesary F., Akbari H. The powerful immune system against powerful COVID-19: A hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2020;140:109762. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soy M., Keser G., Atagündüz P. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: Pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:2085–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P., Lim W.S. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—Preliminary report. N Engl J of Med. 2020 https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arenas M., Sabater S., Hernández V. Anti-inflammatory effects of low-dose radiotherapy. Strahlenther Onkol. 2012;188:975–981. doi: 10.1007/s00066-012-0170-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hess CB, Buchwald ZS, Stokes W, et al. Low-dose whole-lung radiation for COVID-19 pneumonia: Planned day-7 interim analysis of a registered clinical trial [e-pub ahead of print]. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.06.03.20116988. Accessed August 28, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Lara P.C., Burgos J., Macias D. Low dose lung radiotherapy for COVID-19 pneumonia. The rationale for a cost-effective anti-inflammatory treatment. Clin Transl Radiat Oncol. 2020;23:27–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ctro.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kefayat A., Ghahremani F. Low dose radiation therapy for COVID-19 pneumonia: A double-edged sword. Radiother Oncol. 2020;147:224–225. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkby C., Mackenzie M. Is low dose radiation therapy a potential treatment for COVID-19 pneumonia? Radiother Oncol. 2020;147:221. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell E.V. Roentgen therapy of lobar pneumonia. JAMA. 1938;110:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gadrey S.M., Lau C.E., Clay R. Imputation of partial pressures of arterial oxygen using oximetry and its impact on sepsis diagnosis. Physiol Meas. 2019;40 doi: 10.1088/1361-6579/ab5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health The flowchart for diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 in outpatient and inpatient settings [in Persian language], 7th edition. http://treatment.sbmu.ac.ir/uploads/7__dastoor_flochart_treatment_covid_19.pdf Available at:

- 15.Ministry of Health The flowchart for diagnosis and treatment of COVID-19 in outpatient and inpatient settings [in Persian language], 6th edition. http://treatment.sbmu.ac.ir/index.jsp?pageid=63989&p=1 Available at:

- 16.De Sanctis V., Agolli L., Visco V. Cytokines, fatigue, and cutaneous erythema in early stage breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant radiation therapy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/523568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]