Highlights

-

•

Shared emotions can establish emotional attachment with tourists.

-

•

Emotional attachment increases intentions to visit after the current pandemic ends.

-

•

This can be crucial for tourism recovery after COVID-19 ends.

Keywords: COVID-19, Crisis communication, Experimental studies, Risk perception

By 27th April 2020, coronavirus has spread to 185 countries, infecting over 3 million people (BBC, 2020). As a result, hotels such as Four Seasons and Hilton all emphasize their commitment to cleanliness to reduce tourist's perceptions of health risk (Four Seasons, 2020; Hilton, 2020). Such approach mirrors the risk perception literature in tourism research which treats risk as a set of negative outcomes to be avoided (Williams & Balaz, 2015). However, such approach only focuses on cognitive aspects of risk perceptions but ignores emotional responses to risks (Chien, Sharifpour, Ritchie, & Watson, 2017). During COVID-19, both tourists and the hotel sector have common feelings of fear and anxiety (hereafter shared emotions). Tourists have fear and anxiety towards the health risks of COVID-19 and the hotel sector also feel fear and anxiety about the uncertainty they face. We argue crisis communication focusing on shared emotions during the current coronavirus pandemic is very important, as it can establish emotional attachment with tourists. This can be crucial for tourism recovery, because emotional attachment can increase tourists' intentions to visit when the outbreak ends.

Crisis communication on shared emotions

In one of the most cited crisis management models, Ritchie (2004) points out effective crisis communication is crucial for tourism to survive and recover from global crisis. However, recent reviews suggest crisis and disaster management research in tourism mainly focuses on recovery after crisis but offer little insights on communication during in a sustained global crisis such as the coronavirus pandemic (Aliperti et al., 2019; Ritchie & Jiang, 2019). In the general crisis management literature, Coombs (2007) highlights the importance of focusing on stakeholders' emotions in crisis communication, as emotions determine stakeholders' crisis responsibility attribution and their behavioural intentions. But emotions receive scant attention in extant crisis management literature in tourism.

The lack of attention to emotions is also evident in the extant tourism risk perceptions literature, which assumes tourists' risk evaluations are cognitive and consequentialist. However, Chien et al. (2017) demonstrate that tourists' emotions such as worry can also influence their perceptions of risks. Thus, we argue shared emotions crisis communication strategy can increase tourists' intentions to visit after COVID-19. This effect is mediated by brand humanization and emotional attachment. We discuss these arguments in detail below.

First, previous research suggests the feelings of fear and anxiety can trigger a desire for affiliation, increasing consumers' emotional attachment to a brand when consumers and the brand share the same emotional experiences (Dunn & Hoegg, 2014). In other words, Dunn and Hoegg (2014) suggest shared emotional experience is a necessary condition for consumers to feel emotionally attached to a brand and such attachment does not require actual consumption. Thus, we argue that crisis communication on shared emotions such as fear and anxiety can establish emotional attachment with tourists. Extant literature also suggests when depicting brands with human-like minds (e.g. experiencing emotions), it makes consumers anthropomorphize them as humans (MacInnis & Folkes, 2017). Thus, we further argue emotional attachment is the result of tourists' anthropomorphising hotels to establish affiliation with them for reassurance. In other words, brand humanization mediates the impact of shared emotions on emotional attachment. Thomson, MacInnis, and Park (2005) argue emotional attachment can lead to favourable brand attitudes and increased behavioural intentions. Thus, we further argue shared emotions crisis communication can increase tourists' intentions to visit when COVID-19 ends. This effect is mediated by their emotional attachment, which, in turn, is mediated by brand humanization. Put formally:

H1

Shared emotions crisis communication leads to higher emotional attachment than cognitive crisis communication and control (no crisis communication).

H2

Brand humanization mediates the impact of crisis communication on emotional attachment.

H3

Shared emotions crisis communication leads to higher intentions to visit than cognitive crisis communication and control (no crisis communication).

H4

Brand humanization and emotional attachment sequentially mediate the impact of crisis communication on intentions to visit.

Research method

We recruited 430 American participants whose travel plan was disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic via Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). We focused on this group of sample because they are the main target of hotels' current crisis communication (e.g. cancelation policy and commitment to cleanliness). However, 25 participants failed our attention-check questions (hotel name and location), leaving an effective sample size of 405 (178 females, 227 males, M age = 40.6, SD = 11.58).

The experiment was a one-factor (crisis communication strategy: control vs. cognitive vs. shared emotions) between-subject design. We first collected participants' travel plan details (purpose and destination), perceived severity, susceptibility and emotions (fear, anxious, worry, uneasy) towards current coronavirus pandemic. Then participants were randomly allocated to one of the three experimental conditions. Participants in all conditions were exposed to the same experimental stimulus – a fictitious middle-market international hotel chain (XYZ) to control participants' pre-existing knowledge of existing hotels. Participants in the control condition were not exposed to any crisis communication message. In the other two conditions, the hotel's crisis communication focused on the same areas – commitment to cleanliness and cancelation policy but they differed on why the hotel wanted to do this. In the cognitive condition, consistent with many hotels' current response (e.g. Four Seasons), the crisis communication explained the hotel's commitment to cleanliness was to reduce health risk. In the shared emotions condition, the crisis communication explained the hotel's commitment to cleanliness was because it shared the same emotions as tourists: the hotel employees and their families are susceptible to coronavirus just like everyone else. The uncertainty surrounding the pandemic also makes the hotel anxious and worry because “it makes it hard for us to know how exactly we will’ be impacted or how bad things might get”. The rest of materials were identical across conditions. Participants then answered attention check questions and manipulation check question (to what extent the crisis communication focused on shared emotions). The 4-item 11-point scale in Aaker, Vohs, and Mogilner (2010) was used to measure brand humanization. Sample items in the scale were “XYZ feels like a person” and “I've been think about XYZ as a person”. Emotional attachment was gathered via the same items as in Dunn and Hoegg (2014) (also via 11-point scale). Intention to visit was gathered via a single-item 11-point multi-category ordinal answer format.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations are reported in Table 1 . Participants' emotions and perceived severity and susceptibility did not differ across conditions (all ps. > .05), and thus they were excluded from further analysis. Manipulation check suggested participants in the shared emotions condition were more likely to agree that crisis communications focused on shared emotions than the other two conditions (F (2, 404) = 22.86, p < .001), suggesting our manipulation was successful.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation.

| Correlations | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | ||

| 1 | Severity | 8.73 | 2.22 | 0.44*** | 0.36*** | 0.35*** | 0.5*** | 0.37*** | 0.19*** | 0.21*** | 0.24*** | |

| 2 | Susceptibility | 6.26 | 2.84 | 0.44*** | 0.42*** | 0.37** | 0.5*** | 0.4*** | 0.16** | 0.26*** | 0.07 | |

| 3 | Fear | 6.22 | 3.32 | 0.36*** | 0.42*** | 0.74*** | 0.7*** | 0.61*** | 0.21*** | 0.27*** | 0.04 | |

| 4 | Anxious | 6.67 | 3.06 | 0.35*** | 0.37*** | 0.74*** | 0.7*** | 0.71*** | 0.12** | 0.19*** | 0.03 | |

| 5 | Worry | 6.85 | 3.16 | 0.46*** | 0.45*** | 0.70*** | 0.74*** | 0.82*** | 0.14** | 0.21*** | 0.05 | |

| 6 | Uneasy | 6.56 | 3.23 | 0.37*** | 0.40*** | 0.61*** | 0.71*** | 0.8*** | 0.09* | 0.17*** | 0.05 | |

| 7 | Emotional attachment | 6.71 | 2.73 | 0.17*** | 0.16** | 0.21*** | 0.12** | 0.1** | 0.09* | 0.65*** | 0.44*** | |

| 8 | Brand humanization | 4.94 | 2.92 | 0.21*** | 0.26*** | 0.27*** | 0.19*** | 0.2*** | 0.17*** | 0.65*** | 0.34*** | |

| 9 | Intention to visit | 7.96 | 2.62 | 0.24*** | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 0.44*** | 0.34*** | |

Note: *p < .05(one-tailed), **p < .01 (one-tailed), ***p < .001 (one-tailed).

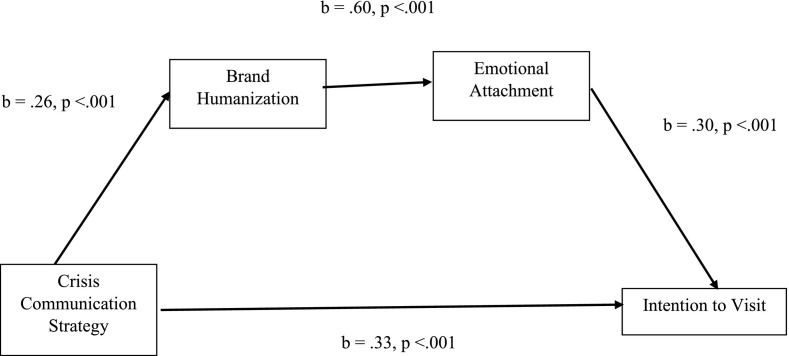

An ANOVA with crisis communication strategy as the independent variable and emotional attachment as the dependent variable suggested emotional attachment differed across conditions (F (2, 404) = 23.47, p < .001). Post-hoc contrast effects further suggested shared emotions condition (M = 7.85, SD = 2.48) led to higher emotional attachment than cognitive condition (M = 6.48, SD = 2.5, p < .001) and control (M = 5.72, SD = 2.8; p < .001), supporting H1. To test H2, we used a bootstrapping-based method (with 5000 resamples) and PROCESS macro (Model 4) with crisis communication strategy as the independent variable, brand humanization as the mediator and emotional attachment as the dependent variable. We found brand humanization had a significant indirect effect on the impact of crisis communication strategy on emotional attachment (coefficient = 0.1587, SE = 0.0298, 95% CI = 0.1003, 0.2160), supporting H2. Another ANOVA with crisis communication strategy as the independent variable and intention to visit as the dependent variable suggested intention to visit differed across conditions (F (2, 404) = 55.17, p < .001). Post-hoc contrast effects further suggested shared emotions condition (M = 9.08, SD = 1.68) led to higher intentions to visit than cognitive condition (M = 8.46, SD = 1.99, p < .01) and control (M = 6.22, SD = 3.13; p < .001), supporting H3. Finally, a bootstrapping-based method (with 5000 resamples) and PROCESS macro (Model 6) with crisis communication strategy as the independent variable, brand humanization and emotional attachment as mediators and intention to visit as the dependent variable suggested: brand humanization and emotional attachment had a significant indirect effect on the impact of crisis communication strategy on intention to visit (coefficient = 0.1549, SE = 0.0438, 95% CI = 0.0782, 0.2464), supporting H4 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Double mediation of brand humanization and emotional attachment.

Conclusions

Our experimental results suggest during COVID-19, crisis communication emphasising on shared emotions can establish emotional attachment with tourists. This is because such approach makes tourists humanize the hotel to fulfil their desire for affiliation. Thus, our research extends extant tourism risk perception literature by highlighting the importance of focusing on tourists' emotional responses to risks. Our results further suggest crisis communication on shared emotions can increase tourists' intentions to visit when the outbreak ends. Thus, our research also contributes to tourism crisis management literature by providing unique insights on the impact of crisis communication during a crisis. This can complement extant literature that is dominated by crisis communication after a crisis. Finally, we theorize and empirically demonstrate brand humanization underlines the impact of shared emotions on emotional attachment. Thus, our research goes beyond Dunn and Hoegg (2014) to demonstrate the key reason shared emotions can trigger emotional attachment.

Practically, our research challenges the cognitive approach that dominates hotels' current COVID-19 communication. Instead, our research suggests hotels should emphasis on shared emotions to build emotional attachment. This can increase tourists' intentions to visit afterwards.

In terms of limitations, our research only measures tourists' behavioural intentions. Thus, future research could measure tourists' actual behaviour to test the robustness of our framework. In addition, we encourage future research to examine the impact of hotels showing empathy on tourists' emotional attachment and behavioural intentions.

Biographies

Lukman Aroean is Lecturer in Marketing and Consumer Behaviour at the University of East Anglia. Focusing on consumer experience and strategic marketing in social media, creative & tourism industry, he has published in the International Journal of Operations & Production Management, International Journal of Research in Marketing, Computers in Human Behavior, Qualitative Market Research, Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Consumer Behaviour, Advances in Consumer Research, Journal of Strategic Marketing and Kindai Management Review.

Zhifeng Chen is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) in Accounting and Finance at the University of the West of England in the UK. She got her PhD in Management from the University of Bath. Her work is cross-disciplinary by nature, characterized by the use of psychological theories and experimentation to gain insights into fundamental social and accounting issues, with a particular focus on tourism and retailing.

Haiming Hang is an Associate Professor in Marketing at the University of Bath. His main research areas are consumer psychology, tourism, retailing and corporate social responsibility. He has published in leading journals such as Journal of Consumer Psychology, Business Ethics Quarterly, Journal of Advertising Research and International Journal of Advertising. His research has been reported in different media such as BBC One Breakfast, Channel 4 News, Observer, Independent and Daily Telegraph (front page).

Associate editor: Viglia Giampaolo

References

- Aaker J., Vohs K.D., Mogilner C. Nonprofits are seen as warm and for-profits as competent: First stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research. 2010;37:224–237. [Google Scholar]

- Aliperti G., Sandholz S., Hagenlocher M., Rizzi F., Frey M., Garschagen M. Tourism, crisis, disaster: An interdisciplinary approach. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019;79:102808. [Google Scholar]

- BBC 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-51235105 (accessed on 27 April 2020)

- Chien M.P., Sharifpour M., Ritchie B.W., Watson B. Travelers’ health risk perceptions and protective behavior: A psychological approach. Journal of Travel Research. 2017;56:744–759. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs W.T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review. 2007;10:163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn L., Hoegg J. The impact of fear on emotional brand attachment. Journal of Consumer Research. 2014;41:152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Four Seasons 2020. https://www.fourseasons.com/landing-pages/corporate/covid_19_update/ (accessed on 2 April 2020)

- Hilton 2020. https://newsroom.hilton.com/corporate/news/statement-from-hilton-coronavirus (accessed on 2 April 2020)

- MacInnis D.J., Folkes V.S. Humanizing brands: When brands see to be like me, part of me, and in a relationship with me. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2017;27:355–374. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie B.W. Chaos, crises and disasters: A strategic approach to crisis management in the tourism industry. Tourism Management. 2004;25:669–683. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie B.W., Jiang Y. A review of research on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management: Launching the annals of tourism research curated collection on tourism risk, crisis and disaster management. Annals of Tourism Research. 2019;79:102812. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson M., MacInnis D.J., Park C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology. 2005;15:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- Williams A.M., Balaz V. Tourism risk and uncertainty: Theoretical reflections. Journal of Travel Research. 2015;54:271–287. [Google Scholar]