Abstract

Patients with atrial fibrillation who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention are at increased risk for both coronary and cerebral thrombotic events. As a result, antithrombotic therapy continues to pose a significant challenge for this patient population. In this review, we discuss the development of warfarin triple therapy as the standard of care during the last century, the transition to dual therapy with warfarin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, the advent of NOACs, recent clinical trials and new regimens with a NOAC and a P2Y12 inhibitor. We also discuss our current clinical practice, based on the available data.

Keywords: Percutaneous Coronary Intervention, Atrial Fibrillation, Anticoagulation, Non-Vitamin K Oral Anticoagulants, Antiplatelet Therapy

Introduction

There are an estimated 33 million people with atrial fibrillation worldwide and approximately 5 million in the United States. In an aging population, the incidence of atrial fibrillation is expected to increase over time. The selection of antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) remains a challenge due to the competing priorities of bleeding prevention, stroke prevention, reduction of stent thrombosis and myocardial infarction. Patients with atrial fibrillation have an indication for oral anticoagulation (OAC) in order to prevent cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) and patients who have undergone PCI have had an indication for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in order to prevent stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, and the need for urgent repeat revascularization.

Warfarin

In the previous century, there were clinical trial data showing the superiority of OAC (warfarin) vs DAPT for the prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation and the superiority of DAPT vs OAC for the prevention of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) after PCI (1). This led to the development of triple anticoagulant therapy (TAT), comprising of warfarin, aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor, which became the standard of care for patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI.

This, however, led to an excess of bleeding, and in real-world practice, there were many patients who were unable to tolerate triple therapy because of bleeding complications or perceived contraindications, leading to under-treatment in nearly half of all patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI (2). At the same time, many patients treated with triple therapy have been exposed to excessive bleeding risk. In the What is the Optimal antiplatElet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with oral anticoagulation and coronary StenTing (WOEST) trial, patients treated with warfarin, aspirin and clopidogrel after PCI had an alarming 44.4% risk of major bleeding at 12 months. This risk was reduced to 19.4% by treating the patients with warfarin and clopidogrel without aspirin—and importantly, there was no increase in MACE events (3). Though WOEST was a small trial, it raised a very interesting question to physicians about whether dual antithrombotic therapy with oral anticoagulation plus a P2Y12 inhibitor might provide the same antithrombotic efficacy with improved bleeding, when compared with classical triple therapy. Even today, dual antithrombotic therapy with warfarin (and a carefully monitored INR) plus a P2Y12 inhibitor is preferred over triple therapy with warfarin, aspirin and a P2Y12 inhibitor.

Replacement of Warfarin with NOACs

At the same time as WOEST, the non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants (NOACs) were being approved for the prevention of stroke in atrial fibrillation. Apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban are highly selective direct reversible/competitive inhibitors of factor Xa. Dabigatran reversibly binds to the active site of thrombin. These medications quickly became attractive alternatives to warfarin because of their daily or twice daily dosing schedules, lack of need for monitoring, and improved interaction profiles. Further, in clinical trials of patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI, dabigatran 110 mg, and edoxaban were similar with respect to efficacy and superior with respect to bleeding, when compared with warfarin; dabigatran 150 mg was superior with respect to efficacy and similar with respect to bleeding; rivaroxaban was non-inferior with respect to bleeding and efficacy; and apixaban was superior with respect to both efficacy and bleeding (4). Moreover, previous concerns about the lack of reversal agents have been mitigated by the advent of andexanet alpha (apixaban, rivaroxaban) and idarucizumab (dabigatran).

With these favorable bleeding profiles, it was important to compare combinations of NOACs and antiplatelets vs warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI. In the past three years, there have been four separate clinical trials to address the question of whether bleeding can be reduced with NOACs and antiplatelets vs warfarin dual or triple therapy (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Trials comparing warfarin triple therapy with dual antithrombotic therapy.

| Trial | Year | Groups | Bleeding | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WOEST | 2013 | • Warfarin+ clopidogrel • Warfarin Triple Therapy |

Any bleeding at one year: 19.4% vs. 44.4%; HR 0.36; 95% CI 0.26–0.50; P<0.0001 | Death, MI, target vessel revasc, stroke or ST: 11.1% vs. 17.6%; HR 0.60; 95% CI 0.38–0.94; P=0.025 |

| PIONEER-AF-PCI | 2016 | • Group 1: rivaroxaban 10–15 mg+ clopidogrel • Group 2: Rivaroxaban 2.5 mg + DAPT • Group 3 warfarin triple therapy |

TIMI Major or Minor Bleeding: Group 1 vs. 3: HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.47–0.76; P<0.001; Group 2 vs. 3: HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.50–0.80; P<0.001 | CV death, MI or stroke: Group 1 vs. Group 3: HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.69–1.68; P=0.75; Group 2 vs. Group 3: HR 0.93; 95% CI 0.59–1.48; P=0.76 |

| RE-DUAL PCI | 2017 | • Dabigatran 110 mg + P2Y12i • Dabigatran 150 mg +P2Y12i • Warfarin Triple Therapy |

ISTH major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding: Dabigatran 110 vs warfarin: 15.4% vs. 26.9%; HR 0.52; 95% CI 0.42–0.63; p < 0.001; Dabigatran 150 vs warfarin: 20.2% vs. 25.7%; HR 0.72; 95% CI 0.58–0.88; p = 0.002 | Death, thrombotic events or unplanned revasc: Dabigatran 110 vs warfarin: 15.2% vs. 13.4%; HR 1.13; 95% CI 0.90–1.43; p = 0.30; Dabigatran 150 vs warfarin: 11.8% vs. 12.8%; HR 0.89; 95% CI 0.67–1.19; p = 0.44 |

| AUGUSTUS | 2019 | 2×2 Factorial Design: • Warfarin vs Apixaban • Aspirin vs placebo (plus clopidogrel) |

ISTH major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding: Apixaban vs warfarin: 10.5% vs. 14.7%; HR 0.69; 95% CI 0.58–0.81; p < 0.001; Aspirin vs placebo: 16.1% vs. 9.0%; HR 1.89; 95% CI 1.59–2.24; p < 0.001 | Death or hospitalization: apixaban vs warfarin: 23.5% vs. 27.4%; HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.74–0.93; p = 0.002; aspirin vs placebo: 26.2% vs. 24.7%; HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.96–1.21; p = NS |

| ENTRUST-AF-PCI | 2019 | • Edoxaban + P2Y12i • Warfarin triple therapy |

ISTH major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding: 17% vs 20%; HR 0.83; 95% CI 0.65–1.05; p for non-inferiority 0.001 | CV death, stroke, SEE, MI or ST: 6% vs 7%; HR 1.06; 95% CI 0.71–1.69; p=NS |

In the Open-Label, Randomized, Controlled, Multicenter Study Exploring Two Treatment Strategies of Rivaroxaban and a Dose-Adjusted Oral Vitamin K Antagonist Treatment Strategy in Subjects with Atrial Fibrillation who Undergo Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PIONEER AF PCI), warfarin triple therapy for 1, 6, or 12 months was compared with low-dose rivaroxaban (15 mg, or 10 mg if low GFR) plus a P2Y12 inhibitor versus very low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg BID) plus DAPT. Both rivaroxaban groups had less bleeding than the warfarin group, without a significant change in cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or stroke (5).

Subsequently, the Randomized Evaluation of Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran versus Triple Therapy with Warfarin in Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (RE-DUAL PCI) trial compared dabigatran 110 mg or 150 mg plus a P2Y12 inhibitor with warfarin triple therapy for 60 or 90 days. The 150 mg dose of dabigatran resulted in a similar bleeding profile to warfarin and the 110 mg dose of dabigatran resulted in improved bleeding compared with warfarin, reminiscent of the RE-LY trial findings (6). It should be noted that in both PIONEER AF PCI and RE-DUAL PCI, there was a significant increase in bleeding with warfarin triple therapy vs NOACs, even with very brief durations of warfarin triple therapy. After RE-DUAL PCI, a meta-analysis compared dual antithrombotic therapy vs triple antithrombotic therapy in the previous trials, finding a 47% reduction in bleeding in the patients assigned to dual antithrombotic therapy without any increases in MACE (7).

Also, in these previous two trials, dual therapy with NOAC and P2Y12 inhibitor, or very low dose NOAC with DAPT had been compared with warfarin triple therapy—but none had been compared with WOEST-like warfarin dual therapy. Furthermore, it was not known the degree to which aspirin contributed to bleeding in warfarin vs NOAC antithrombotic regimens. Accordingly, in An Open-label, 2 × 2 Factorial, Randomized Controlled, Clinical Trial to Evaluate the Safety of Apixaban vs. Vitamin K Antagonist and Aspirin vs. Aspirin Placebo in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation and Acute Coronary Syndrome or Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (AUGUSTUS), patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI were randomized to receive apixaban vs warfarin and also randomized to P2Y12 inhibitor plus aspirin vs placebo. Patients receiving aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor experienced a striking increase in bleeding compared with a P2Y12 inhibitor alone (16.1% vs 9.0%, HR 1.89; 95% CI 1.59–2.24; p<0.001). Also, patients receiving warfarin vs apixaban exhibited a higher risk of bleeding (14.7% vs 10.5%, HR 1.45; 95% CI 1.23–1.72; p<0.001 for noninferiority and superiority). Of the combinations, the apixaban dual therapy group experienced the lowest bleeding, followed by warfarin dual therapy. Both triple therapy groups had significantly higher bleeding rates (Figure 1) (8).

Figure 1.

AUGUSTUS main results. 6-month risk of ISTH Major Bleeding or Clinically Relevant Non-Major Bleeding (MB or CRNM) in patients taking apixaban vs VKA and aspirin vs placebo. For apixaban vs VKA HR=0.69, 95% CI (0.58–0.81), p<0.0001 for noninferiority and superiority, for aspirin vs placebo HR= 1.89, 95% CI (1.59–2.24), p<0.0001.

Most recently, the Evaluation of the Safety and Efficacy of an Edoxaban-based Compared to a Vitamin K Antagonist-based Antithrombotic Regimen in Subjects With Atrial Fibrillation Following Successful Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) With Stent Placement (ENTRUST AF PCI) trial compared edoxaban dual therapy with warfarin triple therapy. Edoxaban dual therapy was non-inferior to warfarin triple therapy, without any significant increase in thrombotic events (9).

In a meta-analysis of clinical trials comparing various VKA vs NOAC and antiplatelet regimens, NOAC plus P2Y12 inhibitors significantly out-performed the reference warfarin triple therapy with respect to trial-defined bleeding, TIMI major and minor bleeding, and intracranial bleeding. All of the combinations of NOAC plus P2Y12 inhibitor or DAPT had similarly low rates of trial-defined MACE, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, stent thrombosis, and hospitalization (10).

Current Clinical Practice

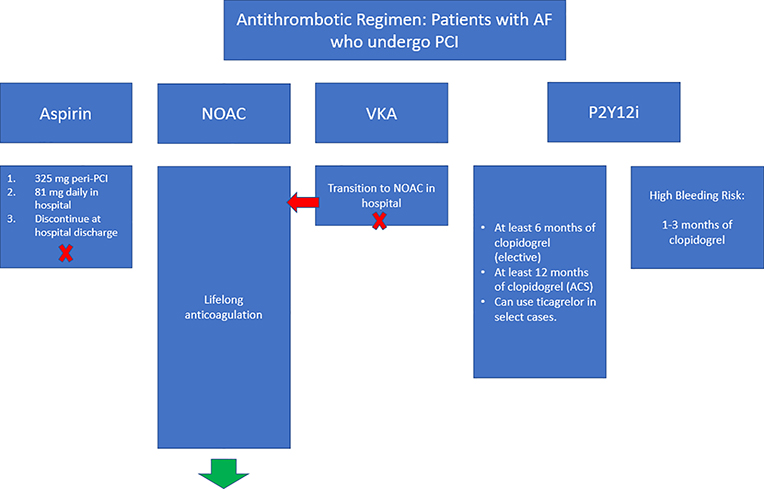

It has been our practice to discharge patients with atrial fibrillation who have undergone PCI on a NOAC plus a P2Y12 inhibitor without aspirin. Typically, a clopidogrel loading dose of 600 mg is given at the time of PCI, followed by 75 mg daily the next day and thereafter. In patients perceived to be at low bleeding risk and high ischemic or stent thrombosis risk, ticagrelor 180 mg followed by 90 mg BID is sometimes used. However, the numbers of patients on ticagrelor included in the previously mentioned trials was relatively small, with even smaller numbers on prasugrel.

Each of the NOAC clinical trials has included peri-procedural aspirin in the NOAC plus P2Y12 inhibitor groups, but the duration of aspirin therapy has differed. Patients receive full-dose aspirin (324 mg) peri-PCI, and then 81 mg daily while in the hospital. Subsequently, upon discharge, no further aspirin is given. The patients continue their therapy with clopidogrel and a NOAC.

The duration of therapy with dual antithrombotic therapy in clinical trials has been generally 6–12 months at a minimum. Accordingly, patients are treated with a NOAC plus P2Y12 inhibitor for one year following their PCI if they came in with an ACS or 6 months if elective, and then switched back to their NOAC without any antiplatelet agents. Some patients with bleeding events or higher bleeding risk have been transitioned to NOAC monotherapy after 1–3 months (Figure 2). The HAS-BLED, PRECISE-DAPT, PARIS and ATRIA scores have all been validated in this patient population and could help guide this decision, reserving shortened durations of antiplatelet therapy to those with the highest bleeding risk.

Figure 2.

Schema of antithrombotic regimens for patients with atrial fibrillation who undergo PCI. NOAC = non-vitamin K oral anticoagulant, VKA = vitamin K antagonist, PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention, ACS = acute coronary syndrome, P2Y12i = P2Y12 inhibitor.

Occasionally, we have discovered that well-meaning physicians have started patients on aspirin after the completion of twelve months. Also, since aspirin is over the counter, and many patients have been told they should “always take it” based on prior guideline recommendations, we have made it a practice to very clearly articulate that aspirin should not be taken. Even still, some patients have unwittingly exposed themselves to the increased bleeding risk of taking triple therapy by taking aspirin even when prescribers thought they were not. Clear communication and patient education are essential in this high-risk and complex patient population.

Regarding NOAC selection, we tend to use apixaban because it was found to be superior to warfarin with respect to bleeding, whereas edoxaban and dabigatran 150 mg were non-inferior. Dabigatran 110 mg and the lower doses of rivaroxaban were also superior to warfarin but are not yet specifically approved by the FDA for this indication. Apixaban is also somewhat preferred among patients with renal insufficiency. However, patient preference, insurance coverage, access to care, cost, need for once daily dosing, prior NOAC therapy, and prescriber familiarity have guided therapy in many cases. With the recent generic availability of apixaban, that will likely further push preferential use of that agent in this setting. If patients with atrial fibrillation already on warfarin undergo PCI, we work with our clinical pharmacists to transition to a NOAC from warfarin in the days following their procedure.

Summary

In summary, patients with atrial fibrillation who undergo PCI require systemic anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy to prevent MACE and strokes. Based on clinical trial data from the last three years, there is no longer justification for using classical “triple therapy” with warfarin and dual antiplatelet therapy. It has been clearly demonstrated that oral anticoagulation plus a P2Y12 inhibitor is superior to triple therapy for any duration of time, even one month. Further, it has been shown that oral anticoagulation with a NOAC is superior to warfarin in this patient population in AUGUSTUS and in a comprehensive meta-analysis. In our practice, we most often discharge patients with atrial fibrillation who undergo PCI on apixaban and a P2Y12 inhibitor, most often clopidogrel and sometimes ticagrelor.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: None

Dr. Deepak L. Bhatt discloses the following relationships - Advisory Board: Cardax, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Medscape Cardiology, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo), Population Health Research Institute; Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Vice-Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Research Funding: Abbott, Afimmune, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, Synaptic, The Medicines Company; Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Svelte; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Takeda.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Disclosures

Dr. Peterson has no conflicts of interest

Compliance with Ethical Standards.

This is a review article, and thus there were no human or animal subjects studied, nor need for informed consent.

References

- 1.Peterson BE, Bhatt DL. Management of Anticoagulation in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI: Double or Triple Therapy? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018. September 26;20(11):110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruff CT, Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Gersh BJ, Alberts MJ, Hoffman EB, et al. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation and atherothrombosis in the REACH Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2014. January 1;170(3):413–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dewilde WJM, Oirbans T, Verheugt FWA, Kelder JC, De Smet BJGL, Herrman J-P, et al. Use of clopidogrel with or without aspirin in patients taking oral anticoagulant therapy and undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2013. March 30;381(9872):1107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson BE, Al-Khatib SM, Granger CB. Apixaban to prevent stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation: a review. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis. 2017. March;11(3):91–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibson CM, Mehran R, Bode C, Halperin J, Verheugt FW, Wildgoose P, et al. Prevention of Bleeding in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2016. 22;375(25):2423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon CP, Bhatt DL, Oldgren J, Lip GYH, Ellis SG, Kimura T, et al. Dual Antithrombotic Therapy with Dabigatran after PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2017. 19;377(16):1513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golwala HB, Cannon CP, Steg PG, Doros G, Qamar A, Ellis SG, et al. Safety and efficacy of dual vs. triple antithrombotic therapy in patients with atrial fibrillation following percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Eur Heart J [Internet]. 2018. April 13 [cited 2018 Apr 17]; Available from: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy162/4970508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopes RD, Heizer G, Aronson R, Vora AN, Massaro T, Mehran R, et al. Antithrombotic Therapy after Acute Coronary Syndrome or PCI in Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2019. March 17; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vranckx P, Lewalter T, Valgimigli M, Tijssen JG, Reimitz P-E, Eckardt L, et al. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of an edoxaban-based antithrombotic regimen in patients with atrial fibrillation following successful percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent placement: Rationale and design of the ENTRUST-AF PCI trial. Am Heart J. 2018. February;196:105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes RD, Hong H, Harskamp RE, Bhatt DL, Mehran R, Cannon CP, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Antithrombotic Strategies in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A Network Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JAMA Cardiol. 2019. June 19; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]