Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) has been reported to be associated with excess risks of death, kidney disease progression and cardiovascular events although previous studies have important limitations. To further examine this, we prospectively studied adults from four clinical centers surviving three months and more after hospitalization with or without AKI who were matched on center, pre-admission CKD status, and an integrated priority score based on age, prior cardiovascular disease or diabetes mellitus, preadmission estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and treatment in the intensive care unit during the index hospitalization between December 2009-February 2015, with follow-up through November 2018. All participants had assessments of kidney function before (eGFR) and at three months and annually (eGFR and proteinuria) after the index hospitalization. Associations of AKI with outcomes were examined after accounting for pre-admission and three-month post-discharge factors. Among 769 AKI (73% Stage 1, 14% Stage 2, 13% Stage 3) and 769 matched non-AKI adults, AKI was associated with higher adjusted rates of incident CKD (adjusted hazard ratio 3.98, 95% confidence interval 2.51-6.31), CKD progression (2.37,1.28-4.39), heart failure events (1.68, 1.22-2.31) and all-cause death (1.78, 1.24-2.56). AKI was not associated with major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events in multivariable analysis (0.95, 0.70-1.28). After accounting for degree of kidney function recovery and proteinuria at three months after discharge, the associations of AKI with heart failure (1.13, 0.80-1.61) and death (1.29, 0.84-1.98) were attenuated and no longer significant. Thus, assessing kidney function recovery and proteinuria status three months after AKI provides important prognostic information for long-term clinical outcomes.

Keywords: acute kidney injury, acute renal failure, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, mortality

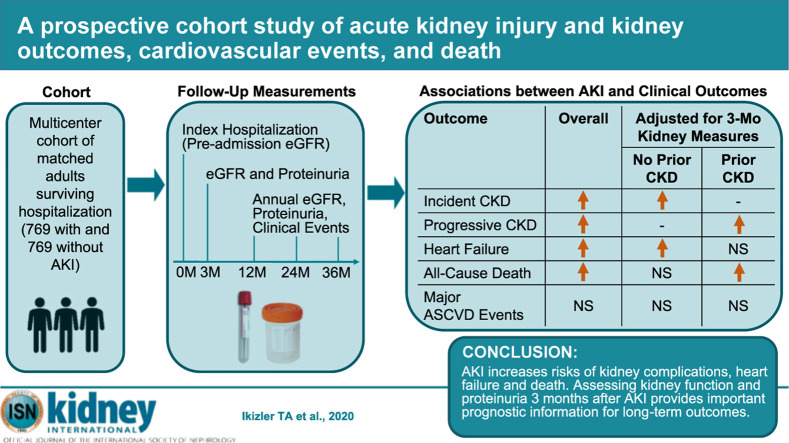

Graphical abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) reflects an abrupt decline in kidney function that occurs frequently among hospitalized adults and has been reported to be associated with excess risks of death, kidney disease progression, and cardiovascular events.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 The potential importance of AKI has been further highlighted during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic.9

However, there are important limitations of many existing studies examining clinical complications after AKI. These include primarily retrospective designs that are susceptible to multiple biases, lack of systematic assessment of kidney function before and after the AKI episode, use of varying definitions of AKI, lack of adjudication of potential cardiovascular events, and inclusion of study populations with limited demographic diversity. In addition, hospitalized patients, who may be at increased risk for these events, are not always compared with similar hospitalized patients without AKI. Furthermore, the limited number of existing prospective studies have primarily focused on selected populations (e.g., coronary angiography,10 cardiac surgery,11, 12, 13 or myocardial infarction14) and have not examined heart failure separately with atherosclerotic cardiovascular events.

Given the global burden of AKI and the need for additional evidence-based clinical guidance, we addressed these issues by prospectively examining the associations among AKI with subsequent kidney-related consequences, heart failure, major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events (MACE), and death among matched adults surviving a hospitalization with or without AKI. We hypothesized AKI would be independently associated with higher risks of each of these events in the presence or absence of preexisting chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Results

Baseline characteristics and follow-up

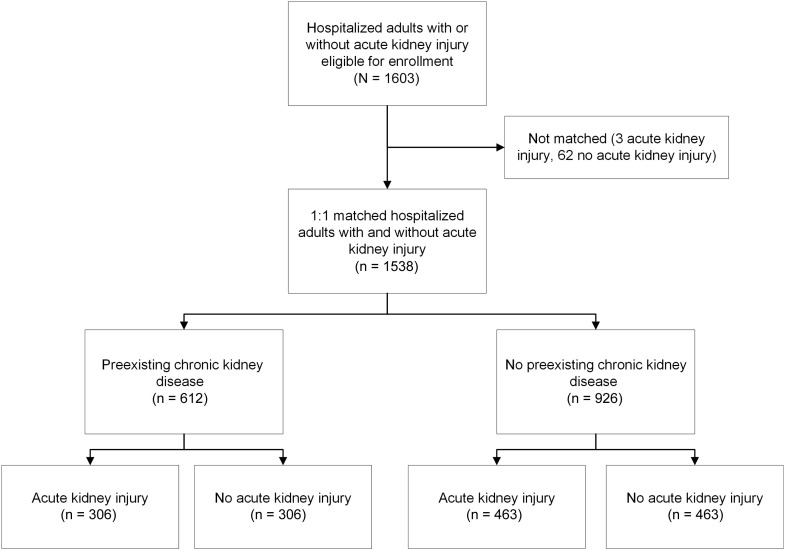

We enrolled and individually matched 769 adults with AKI and 769 adults without AKI, with 39.8% having preexisting CKD (Supplementary Appendix S1 and Figure 1 ). The distribution of matched pairs enrolled by center was 156 (20.3%) from Kaiser Permanente Northern California, 251 (32.6%) from Vanderbilt University, 154 (20.0%) from the Translational Research Investigating Biomarker Endpoints for Acute Kidney Injury (TRIBE-AKI) Consortium, and 208 (27.1%) from the University of Washington. Among participants with AKI, 561 (73%), 111 (14%), and 97 (13%) had stages 1, 2, and 3 AKI, respectively, with only 26 (1.7%) of participants with AKI who were receiving acute renal replacement therapy. Furthermore, 48% of AKI episodes were of brief duration, 22% were of medium duration, 12% were of long duration, and 18% were of very long duration. Regardless of CKD status, compared with participants classified as non-AKI, those with AKI were modestly younger, had slightly lower preadmission estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and were more likely to have prior cardiovascular disease, have diabetes, receive care in an intensive care unit, be diagnosed with sepsis during the index hospitalization, and have higher baseline study visit levels of plasma cystatin C and proteinuria. In contrast, there were no significant differences in Hispanic ethnicity, smoking status, or baseline study visit measures of body mass index or systolic or diastolic blood pressure (Table 1 ). Among participants without preexisting CKD, the proportion of women was lower in those with AKI, but there was no significant difference in self-reported race. In participants with preexisting CKD, there was no significant difference in sex between groups, but those with AKI were less likely to be White (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Assembly of matched cohort of adults surviving a hospitalization with and without acute kidney injury.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of adults with and without AKI, stratified by the presence or absence of CKD at study entry

| Characteristic | No preexisting CKD |

Preexisting CKD |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AKI (n = 463) | No AKI (n = 463) | P Value | AKI (n = 306) | No AKI (n = 306) | P Value | |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | ||||||

| Preadmission | 0.94 (0.20) | 0.87 (0.17) | <0.0001 | 1.69 (0.60) | 1.47 (0.48) | <0.0001 |

| Inpatient | 2.14 (1.71) | 0.90 (0.20) | <0.0001 | 2.94 (1.76) | 1.43 (0.44) | <0.0001 |

| 3-mo baseline | 1.02 (0.47) | 0.86 (0.20) | <0.0001 | 1.71 (0.78) | 1.37 (0.50) | <0.0001 |

| Estimated GFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | ||||||

| Preadmission | 83.8 ± 17.8 | 86.1 ± 16.1 | 0.003 | 42.0 ± 12.1 | 46.0 ± 10.2 | <0.0001 |

| Inpatient | 41.6 ± 17.2 | 84.0 ± 17.5 | <0.0001 | 24.3 ± 9.6 | 47.7 ± 12.3 | <0.0001 |

| 3-mo baseline | 79.8 ± 22.5 | 86.9 ± 17.9 | <0.0001 | 44.3 ± 17.3 | 51.2 ± 14.7 | <0.0001 |

| Age, yr | 60.7 ± 12.9 | 61.7 ± 13.1 | 0.02 | 68.1 ± 11.2 | 71.1 ± 9.4 | <0.0001 |

| Women | 129 (27.9) | 191 (41.3) | <0.0001 | 121 (39.5) | 133 (43.5) | 0.39 |

| Race | 0.27 | 0.02 | ||||

| White | 378 (81.6) | 394 (85.1) | 229 (74.8) | 259 (84.6) | ||

| Black | 65 (14.0) | 47 (10.1) | 52 (17.0) | 31 (10.1) | ||

| Other | 20 (4.4) | 22 (4.8) | 25 (8.2) | 16 (5.3) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 13 (2.8) | 10 (2.2) | 0.68 | 8 (2.6) | 7 (2.3) | 0.99 |

| Smoking status | 0.10 | 0.48 | ||||

| Never | 176 (38.0) | 209 (45.1) | 132 (43.1) | 117 (38.2) | ||

| Former | 199 (43.0) | 188 (40.6) | 145 (47.4) | 157 (51.3) | ||

| Current | 87 (18.8) | 61 (13.2) | 25 (8.2) | 29 (9.5) | ||

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 5 (1.1) | 4 (1.3) | 3 (1.0) | ||

| Prior cardiovascular disease | 200 (43.2) | 147 (31.8) | <0.0001 | 172 (56.2) | 146 (47.7) | <0.0001 |

| Prior diabetes mellitus | 201 (43.4) | 147 (31.8) | <0.0001 | 186 (60.8) | 127 (41.5) | <0.0001 |

| Treated in ICU during index admission | 340 (73.4) | 307 (66.3) | <0.0001 | 205 (67.0) | 166 (54.2) | <0.0001 |

| Sepsis during index admission | 89 (19.2) | 14 (3.0) | <0.0001 | 29 (9.5) | 12 (3.9) | 0.006 |

| 3-mo baseline measurements | ||||||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 31.4 ± 8.5 | 30.5 ± 7.2 | 0.07 | 32.0 ± 8.1 | 30.6 ± 6.8 | 0.07 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 128 ± 22 | 126 ± 19 | 0.27 | 129 ± 23 | 127 ± 20 | 0.36 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 73 ± 13 | 74 ± 13 | 0.42 | 68 ± 14 | 69 ± 14 | 0.55 |

| Plasma cystatin C, mg/l | 1.2 (1.0, 1.5) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.2) | <0.0001 | 2.0 (1.6, 2.6) | 1.7 (1.4, 1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.2) | 0.03 | 0.2 (0.1, 0.7) | 0.1 (0.1, 0.3) | <0.0001 |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; ICU, intensive care unit.

Values are n (%), mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range).

Mean follow-up was 4.5 ± 1.8 years overall, with mean follow-up of 4.3 ± 1.8 years in participants with AKI and 4.4 ± 1.8 years in participants classified as non-AKI. During follow-up, 82 participants with AKI and 82 who were non-AKI withdrew from the study.

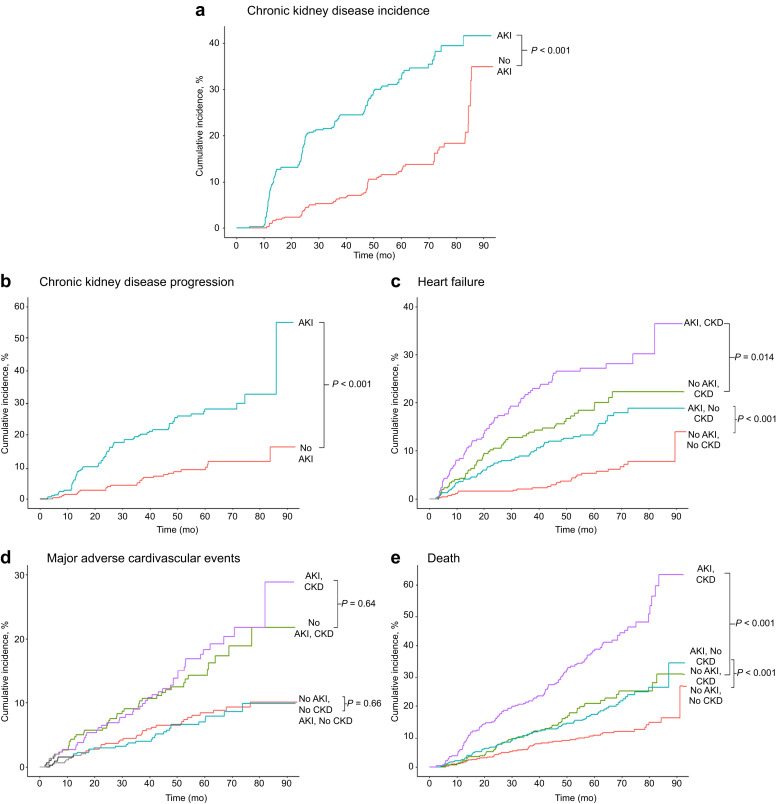

Kidney outcomes

During follow-up, CKD incidence was 4.1 per 100 person-years in participants with AKI compared with 1.8 per 100 person-years in matched adults who were non-AKI (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2 a). In participants with preexisting CKD, the rate of those experiencing CKD progression was 2.1 per 100 person-years in participants with AKI compared with 0.7 per 100 person-years in matched participants who were non-AKI (P < 0.0001) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of renal, heart failure, major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and all-cause death in patients with and without acute kidney injury (AKI), stratified by the presence or absence of preexisting chronic kidney disease (CKD). The results for (a) incident and (b) progressive CKD are shown. The results for (c) heart failure, (d) major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events, and (e) all-cause death are shown.

In multivariable analysis among matched participants without preexisting CKD, AKI was associated with a 3.4-fold higher adjusted rate of incident CKD (model 1, Table 2 ). Further adjustment for additional demographic characteristics, sepsis during the index admission and smoking, diabetes status, and body mass index at the baseline visit strengthened the association (adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 3.98; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.51–6.31) (model 2, Table 2). AKI was associated with a 2.3-fold higher adjusted rate of CKD progression in matched participants (model 1, Table 2), and the association with CKD progression increased after adjustment for additional potential confounders (adjusted HR: 2.37; 95% CI: 1.28–4.39) (model 2, Table 2). For both incident and progressive CKD, there was also a significant trend (P < 0.001 for linear trend) with more severe and longer AKI in multivariable analyses (Supplementary Appendices S2 and S3). In a sensitivity analysis among participants with AKI and those who were non-AKI exactly matched on each matching criteria, results were similar to the main analyses (Supplementary Appendix S4).

Table 2.

Association of AKI with development of incident CKD and progression of CKD

| Nested model | HR (95% CI) of AKI vs. no AKI on kidney outcomes |

|

|---|---|---|

| Incident CKD | CKD progression | |

| Model 1: matcheda cohort | 3.41 (2.35–4.95) | 2.30 (1.32–3.99) |

| Model 2: model 1 + sex; race/ethnicity; sepsis during index admission; 3-mo baseline visit smoking status, diabetes status, and body mass index | 3.98 (2.51–6.31) | 2.37 (1.28–4.39) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HR, hazard ratio.

Matching variables included clinical center, age, preindex admission estimated glomerular filtration rate, preindex admission diabetes status, prior cardiovascular disease, and intensive care unit stay during index admission.

Heart failure events

Among matched participants without prior CKD, the incidence of hospitalization for heart failure was higher in those with versus in those without AKI (3.0 vs. 1.1 per 100 person-years, respectively; P < 0.001). The pattern was similar in those with preexisting CKD, with a higher incidence in those with versus in those without AKI (5.9 vs. 3.9 per 100 person-years, respectively; P = 0.014) (Figure 2c).

In multivariable analysis among matched participants, AKI was associated with a nearly 2-fold higher adjusted rate of heart failure events (model 1, Table 3 ) that was attenuated after additional adjustment for potential confounders (adjusted HR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.22–2.31) (model 2, Table 3). However, further adjustment for eGFR, cystatin C, and proteinuria measured at the 3-month postdischarge baseline visit markedly attenuated the association of AKI with subsequent heart failure hospitalization that was no longer significant (model 3, Table 3). The relative strength of association was weaker in those with versus in those without preexisting CKD, but the patterns with multivariable adjustment were similar (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of AKI with subsequent heart failure, MACEs, and death, overall and stratified by preexisting CKD

| Nested model | HR (95% CI) of AKI vs. no AKI |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heart failure |

MACE |

Death from any cause |

|||||||

| Overall | No preexisting CKD | Preexisting CKD | Overall | No preexisting CKD | Preexisting CKD | Overall | No preexisting CKD | Preexisting CKD | |

| Model 1: matcheda cohort | 1.83 (1.37–2.44) | 2.70 (1.73–4.21) | 1.24 (0.89–1.72) | 1.01 (0.75–1.34) | 0.95 (0.64–1.40) | 1.07 (0.73–1.56) | 1.89 (1.35–2.63) | 1.67 (1.08–2.58) | 2.13 (1.36–3.34) |

| Model 2: model 1 + sex, race/ethnicity, sepsis during index admission, 3-mo baseline visit smoking status, diabetes status, and body mass index | 1.68 (1.22–2.31) | 2.47 (1.54–3.96) | 1.14 (0.79–1.66) | 0.95 (0.70–1.28) | 0.90 (0.59–1.37) | 1.00 (0.65–1.52) | 1.78 (1.24–2.56) | 1.38 (0.85–2.26) | 2.29 (1.41–3.71) |

| Model 3: model 2 + 3-mo baseline visit estimated glomerular filtration rate, plasma cystatin C, and urine protein-to-creatinine ratio | 1.13 (0.80–1.61) | 1.48 (0.94–2.33) | 0.87 (0.55–1.38) | 1.20 (0.85–1.70) | 0.99 (0.63–1.55) | 1.46 (0.92–2.30) | 1.29 (0.84–1.98) | 1.34 (0.75–2.39) | 1.24 (0.70–2.18) |

AKI, acute kidney injury; CI, confidence interval; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HR, hazard ratio; MACE, major atherosclerotic cardiovascular event.

Matching variables included clinical center, age, preindex admission estimated glomerular filtration rate, preindex admission diabetes status, prior cardiovascular disease, and intensive care unit stay during index admission.

In addition, after accounting for matching variables and potential confounders, there was a significant association of more severe AKI with heart failure hospitalization in those without preexisting CKD (P = 0.022 for linear trend) but not in those with preexisting CKD (P = 0.62 for linear trend). The association in those without preexisting CKD was notably attenuated and no longer significant after further adjustment for baseline visit measures of kidney function and proteinuria (Supplementary Appendix S2). Longer AKI duration was associated with higher adjusted rate of heart failure hospitalization in a fully adjusted model (Supplementary Appendix S3). In a sensitivity analysis of exactly matched participants with AKI and without AKI, results were similar to the main analysis except that there remained a 2-fold higher adjusted risk of heart failure events associated with AKI and no preexisting CKD, even after additionally accounting for 3-month postdischarge measures of kidney function and proteinuria (Supplementary Appendix S4).

Major atherosclerotic cardiovascular events

In those without underlying CKD, the incidence of MACE was 1.5 per 100 person-years in participants with AKI compared with 1.6 per 100 person-years in matched participants classified as non-AKI (P = 0.66). There was also no significant difference in MACE incidence between those with CKD with AKI and those without AKI (3.6 vs. 3.1 per 100 person-years, respectively; P = 0.64) (Figure 2d). Results were unchanged in multivariable analyses (Table 3). There was also no significant association between AKI severity and MACE (Supplementary Appendix S2). Results were similar to the main analysis in a sensitivity analysis among the subset of participants—AKI and non-AKI—that were exactly matched on all matching criteria (Supplementary Appendix S4).

Mortality

All-cause mortality was higher in those with versus in those without AKI and in the presence or absence of preexisting CKD (Figure 2e). After accounting for matching and additional confounders, AKI was associated with a 78% higher rate of death (model 2, Table 3) that was markedly attenuated and no longer significant after further accounting for degree of renal recovery and proteinuria status at 3 months postdischarge (model 3, Table 3). Results were similar in fully adjusted models regardless of the presence of preexisting CKD (Table 3). There was a significant trend of more severe AKI with excess mortality that was attenuated and no longer significant after adjustment for 3-month postdischarge kidney function and proteinuria, while longer AKI duration was independently associated with higher mortality (Supplementary Appendices S2 and S3). In sensitivity analyses in the subset of participants—AKI and non-AKI—that were exactly matched on all matching criteria, results were similar to the main analyses, except that AKI was independently associated with a nearly 2-fold higher rate of death in those with preexisting CKD even after additional adjustment for 3-month postdischarge kidney function and proteinuria (Supplementary Appendix S4).

Discussion

In a prospective cohort of matched hospital survivors, AKI was independently associated with higher subsequent risks of both incident CKD and progressive CKD. In the overall matched cohort, AKI was also associated with excess risks of heart failure hospitalization and all-cause death—regardless of the presence or absence of preexisting CKD—but these associations were substantially attenuated and no longer statistically significant after accounting for residual kidney function and proteinuria measured 3 months after discharge. In fully adjusted models stratified by preexisting CKD status, we also found that AKI remained significantly associated with an excess risk of heart failure events in patients without preexisting CKD, while there was a significantly higher risk of all-cause death in those with preexisting CKD. However, AKI was not significantly associated with MACE, overall or in those with or without preexisting CKD.

The Assessment, Serial Evaluation, and Subsequent Sequelae of Acute Kidney Injury (ASSESS-AKI) study is unique as it represents the largest prospective cohort study of a broad population of carefully matched adults who survived ≥3 months after hospital discharge to examine the association of AKI with kidney and cardiovascular events over a long follow-up period. This population is highly relevant clinically as an increasingly common scenario that physicians encounter in the outpatient setting of posthospitalization AKI survivors. Two additional key features of ASSESS-AKI compared with previous studies are the prespecified availability of a preindex hospitalization serum creatinine (7 to 365 days before admission) and completion of a 3-month postdischarge study visit as entry criteria. The true preindex hospitalization “baseline” serum creatinine concentration allowed us to diagnose AKI and its severity with greater precision using currently recommended criteria.15 The systematic measurement of eGFR, plasma cystatin C, and proteinuria at 3 months postdischarge was also critical, as we demonstrated that the overall associations of AKI with excess risks of heart failure and death were notably attenuated after accounting for residual kidney function and damage. This finding has significant clinical practice implications because evaluation of kidney function and proteinuria 3 months after discharge, which can be readily obtained through primary care, would yield important long-term prognostic information. Our study had several additional strengths beyond the prospective design and structured protocol among a matched cohort that helps overcome many biases that can affect retrospective studies. We had systematic, long-term follow-up measurements of postdischarge kidney function and identification and validation of heart failure events and MACE using standardized criteria. Our cohort also included a geographically diverse set of patients recruited from intensive care unit (ICU) and non-ICU hospitalized settings.

Our study also has several limitations. Information was not available on the presence and severity of proteinuria before the index hospitalization. Data were also unavailable on preadmission eGFR slope, as well as etiology of the AKI episode, although we note there is no generally acceptable approach to adjudicate accurately the true etiology of AKI.16 Information on preadmission blood pressure was also unavailable. Given our cohort was based in North American clinical centers and enriched with patients undergoing cardiac surgery or treated in an ICU, our results may not fully generalize to all hospitalized patients, practice settings, or geographic areas. As an observational study, we cannot prove causal relationships between an episode of AKI and subsequent clinical outcomes, as we cannot rule out residual or unmeasured confounding.

The population of survivors of AKI is growing in parallel with the number of patients experiencing sepsis or cardiovascular diseases, including heart failure.17 , 18 Our findings that suggest AKI, even its mildest form, may contribute to long-term adverse outcomes have important implications.6 , 19 , 20 While previous studies have examined the association of AKI on kidney and cardiac complications in hospitalized patients, many suffer from several limitations. Nearly all studies were retrospective in design with their accompanying biases, and several relied only on administrative codes to assign AKI status rather than objective preadmission and in-hospital serum creatinine results. Our study materially expands on a recent prospective study of 968 adults undergoing cardiac surgery that found that AKI was associated with a higher adjusted rate of the composite outcome of death or hospitalization for acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, or receipt of coronary revascularization.21

Mechanisms by which AKI drives development and progression of CKD, as well as excess heart failure complications, are not fully elucidated.22 AKI is associated with increased levels of inflammatory cytokines,23 endothelial dysfunction,24 dysregulation in mineral metabolism,25 , 26 and myocardial damage.27 Yet, shared risk factors among AKI, CKD, and cardiovascular disease (e.g., age, diabetes, hypertension) and lack of mechanistic studies have raised some skepticism about a causal relationship between AKI and future adverse outcomes.22 One potential explanation is that the kidney plays a critical role in sodium handling and subsequent volume status and blood pressure control. Tubular injury sustained during AKI, especially in severe forms, could lead to impaired natriuresis that can predispose to subclinical vascular congestion during high sodium intake.22 , 28, 29, 30 This would, in turn, result in subtle tubular dysfunction whose effects on vulnerable kidneys may accumulate over time leading to a vicious cycle of recurrent AKI episodes, heart failure, and progressive CKD.

In summary, we found that AKI independently associated with higher rates of incident and progressive CKD, as well as subsequent heart failure events and death among survivors of a recent hospitalization. However, after additionally accounting for degree of renal recovery and proteinuria status 3 months after discharge, the associations of AKI with heart failure and death were not significant. More severe and longer AKI duration may also be associated with worse clinical outcomes. Our study provides new data to support systematically evaluating level of kidney function recovery and proteinuria 3 months after an episode of AKI to provide relevant prognostic information that may help guide clinical decision making. Furthermore, definitive randomized trial evidence is needed to determine whether strategies to prevent AKI or interventions early in the course of AKI can reduce the risks of future adverse renal and cardiovascular outcomes.22

Methods

Study population

The ASSESS-AKI study, sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, is a prospective, matched cohort study of hospitalized persons who did or did not experience an episode of AKI and survived to complete an in-person baseline study visit 3 months after discharge. Details of the design and methods have been previously described.31 Briefly, 769 hospitalized adults who experienced an episode of AKI were enrolled between December 1, 2009, and February 28, 2015, from 4 North American clinical centers involving various hospital settings (general medical and surgical wards, ICUs, and post–cardiac surgery wards), with eligibility confirmed at the baseline visit 3 months after discharge. Briefly, Kaiser Permanente Northern California recruited participants hospitalized in medical and surgical wards as well as ICUs at 4 Kaiser Permanente medical centers (Oakland, Walnut Creek, Hayward, and San Francisco, CA). Vanderbilt University recruited participants from the Validation of Acute Lung Injury Biomarkers for Diagnosis (VALID) study of critically ill patients32 as well as patients hospitalized at Vanderbilt Medical Center (Nashville, TN) in ICUs and medical and surgical ward settings. TRIBE-AKI investigators enrolled adult participants in the TRIBE-AKI Consortium33 during preoperative evaluation for cardiac surgery at Yale University (New Haven, CT) and London Health Sciences Center (Ontario, Canada). The University of Washington enrolled participants from the ICU as well as medical and surgical wards at Harborview Medical Center (Seattle, WA).

AKI during the index hospitalization was defined using Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) criteria15 based on an increase of ≥50% or ≥0.3 mg/dl in serum creatinine concentration above an outpatient, non–emergency department baseline value within 7 to 365 days before the index admission. During the same period, a matched sample of 769 hospitalized adults without AKI at the same sites were enrolled. We aimed to have a wide range of AKI severity represented, with targeted enrollment of one-third of participants having stage 2 or 3 AKI.15 Patients were individually matched on clinical research center and preadmission CKD status, with additional matching to reduce confounding using an integrated, weighted priority score (0 to 100) based on prior cardiovascular disease (30 points), prior diabetes mellitus (25 points), preadmission level of eGFR category (15–29, 30–44, 45–59, 60–89, 90–150 ml/min per 1.73 m2) using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation34 (20 points), age category (18–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–89 years) (15 points), and receiving treatment within an ICU during the index hospitalization (10 points). Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in the protocol31 and Supplementary Appendix S1. Briefly, the main inclusion criteria included age 18 to 89 years and having a baseline outpatient, non–emergency department serum creatinine value within 365 days before enrollment. Major exclusion criteria included inability to provide consent; acute glomerulonephritis; hepatorenal syndrome; multiple myeloma, metastatic or actively treated malignancy; significant urinary tract obstruction; severe heart failure; death, receiving chronic dialysis, kidney, or other transplant before the 3-month postdischarge baseline visit; pregnant or breastfeeding; enrolled in an interventional study at the baseline study visit; or predicted survival of 12 months of less by a study physician.

The study was carried out in a clinical research facility. All the study participants were volunteers. Neither the study participants nor the public were involved in the development of research questions, study design and measures, or assessment of the time required to participate in the research. The study was approved by institutional review boards of the participating institutions, and written informed consent was obtained from participants. Results of the study will be shared with study participants.

Study visits

At the 3-month postdischarge baseline visit, we obtained information on sociodemographic characteristics; nephrotoxic exposures and complications occurring during the index hospitalization; cardiovascular, renal, and other medical history; tobacco use; and prescription and over-the-counter medication use.31 In addition, height, weight, blood pressure, and heart rate were measured using standardized methods.31 Blood samples for DNA, sera, and plasma were collected; a urine dipstick proteinuria test performed; and 12-lead electrocardiogram was obtained using standardized methods.

A follow-up visit was conducted 12 months after the index hospitalization and annually thereafter (with determination of eGFR), with interim phone contacts at 6-month intervals.31 Medical history, including interim hospitalizations, and medication use were updated at each contact.

Follow-up and outcome ascertainment

Follow-up occurred through November 30, 2018, with censoring due to withdrawal or end of study follow-up. Vital status was updated at each study contact and through medical records review. Kidney and cardiovascular events were a priori considered primary outcomes.

Kidney events included incident CKD and CKD progression. Incident CKD among participants without preexisting CKD at the index hospitalization was defined as the combination of ≥25% reduction in eGFR (compared with preindex admission eGFR) and achieving CKD stage 3 or worse.35 In participants with preexisting CKD at the index hospitalization (defined as preadmission eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), CKD progression was defined as ≥50% reduction in eGFR compared with baseline, reaching CKD stage 5 or receiving renal replacement therapy (chronic dialysis or kidney transplant).35

We ascertained potential heart failure events and MACE based on participant self-report, and by periodic searches of electronic medical records. For all hospitalizations, we initially obtained information on International Classification of Diseases, Ninth or Tenth Edition diagnostic codes for heart failure and MACE, including myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, and peripheral artery disease (codes available on request).31 For hospitalizations without a qualifying code, the discharge summary was reviewed by a study investigator to ensure no heart failure events or MACE were missed. The event adjudication committee, composed of trained physicians from each clinical center, centrally and locally adjudicated potential cardiovascular events based on a review of medical records using Framingham Heart Study clinical criteria36 for heart failure and standardized criteria37 , 38 for MACE.

Vital status was captured through protocol-driven phone-based surveillance complemented by proxy reporting by participants’ contacts, information from sites’ electronic medical record systems, and death certificate data, as available at each participating center.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics included age, sex, and self-reported race (White, Black, Other) and Hispanic ethnicity. We recorded self-reported tobacco use and prior cardiovascular disease (i.e., heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, or peripheral artery disease). Hypertension was based on self-report combined with receipt of antihypertensive agents or having a study visit systolic blood pressure >140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure >90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus was based on self-report, receipt of antidiabetic agents, or glycosylated hemoglobin ≥6.5%. At the baseline visit occurring at 90 days postdischarge, we measured serum creatinine using an isotope dilution mass spectrometry–traceable enzymatic assay (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), plasma cystatin C standardized against the international calibrator standard ERMDA471/IFCC (Gentian, Moss, Norway), and a random spot urine protein-to-creatinine ratio using a turbidimetric method (Roche).

Statistical approach

Analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Characteristics were compared between matched participants with AKI and those without AKI using paired Student's t tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables and McNemar tests for categorical variables. Rates of each outcome (per 100 person-years) with associated 95% confidence limits were calculated for participants with AKI and those without AKI, and cumulative incidence curves compared using a log-rank test.

For each outcome, after confirming no violation of the proportional hazards assumption by examining log-log-survival curves, we performed nested Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard analyses39 accounting for individual matching and competing risk of death, with additional incremental adjustment for variables not included in the matching criteria that have been previously reported or hypothesized to be risk factors for kidney and cardiovascular events, or differing between participants with AKI and those without AKI at the baseline study visit. Based on an a priori hypothesis, prespecified overall and stratified analyses were performed to evaluate for a potential interaction between an episode of AKI and preexisting CKD status.31 For cardiovascular and death outcomes, the final model additionally adjusted for 3-month postdischarge measures of kidney function and proteinuria based on a priori hypotheses that levels of residual kidney function and damage may explain, at least in part, any observed excess risks for these clinical outcomes after an episode of AKI. Models were performed overall and stratified by pre-existing CKD status, as appropriate. Because outcomes were time-to-event with right-censoring due to death, study withdrawal, or end of study follow-up, we did not impose any procedure to account for potential missingness in the outcomes.

We separately examined the association of severity of the index AKI episode with outcomes of interest by modeling KDIGO stage of AKI (1, 2, or 3) as a linear term. We used a similar approach to separately examine the association of AKI episode duration (non-AKI, AKI ≤1 day [brief], 1 day < AKI duration ≤ 3 days [medium], 3 days < AKI duration ≤ 6 days [long], AKI duration > 6 days [very long]). Because our matching algorithm did not result in an exact match on all criteria in the 769 pairs of participants—AKI–non-AKI—we also conducted sensitivity analyses among 1375 patients placed within 328 strata who were exactly matched on all individual matching criteria within each stratum.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the ASSESS-AKI study participants, research coordinators, and support staff for making this study possible.

This study was supported by the supplemental American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds and research grants U01DK082223, U01DK082185, U01DK082192, U01DK082183, U01DK084012, and R01DK098233 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. This publication was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through University of California, San Francisco–Clinical and Translational Science Institute grant UL1RR024131. CRP is also supported by grant R01HL085757. JH is also supported by U2CDK114886, UG3TR002158, and U01DK099923. SGC is also supported by grants R01DK106085 and U01DK106962. AXG is also supported by the Dr. Adam Linton Chair in Kidney Health Analytics, and a Clinician Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. LBW is also supported by grants R01HL135849 and R01HL103836. KDL, C-yH, and ASG are also supported by grants R01DK101507, U01DK060902, R01DK101507, K24DK113381, and K24DK92291. EDS is also supported by grant 5K23DK088964.

The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services or the United States government.

Transparency Statement

The lead author (TAI) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as originally planned have been explained.

Author Contributions

TAI, CRP, JH, VMC, KDL, SGC, AXG, C-yH, EDS, MMW, GBF, TCT, JSK, PLK, and ASG conceived and designed the study. TAI, CRP, JH, VMC, KDL, SGC, AXG, C-yH, EDS, MMW, LBW, GBF, TCT, JSK, PLK, and ASG analyzed and interpreted data. TAI, VMC, and ASG drafted the manuscript. CRP, JH, KDL, SGC, AXG, C-yH, EDS, MMW, LBW, GBF, TCT, JSK, and PLK revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. ASG is the guarantor.

Footnotes

Appendix S1. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Appendix S2. Severity of acute kidney injury and adverse clinical outcomes.

Appendix S3. Category of duration of acute kidney injury and adverse clinical outcomes.

Appendix S4. Acute kidney injury and adverse clinical outcomes in 1375 patients with and without AKI that were exactly matched on all matching criteria.

Contributor Information

ASSESS-AKI Study Investigators:

Vernon M. Chinchilli, Alan S. Go, Jonathan Himmelfarb, T. Alp Ikizler, James S. Kaufman, Paul L. Kimmel, Chirag R. Parikh, John B. Stokes, Steven Coca, Amit Garg, Sijie Zheng, Leonid Pravoverov, Chi-yuan Hsu, Raymond K. Hsu, Kathleen D. Liu, W. Brian Reeves, Edward D. Siew, Julia B. Lewis, Lorraine Ware, Prasad Devarajan, Catherine Krawczeski, Michael Bennett, Michael Zappitelli, and Mark Wurfel

Appendix

ASSESS-AKI Study Investigators (listed alphabetically)

Vernon M. Chinchilli, Alan S. Go, Jonathan Himmelfarb, T. Alp Ikizler, James S. Kaufman, Paul L. Kimmel, Chirag R. Parikh, and John B. Stokes (in memoriam). Additional collaborators are as follows: Yale: Steven G. Coca; London, Canada: Amit X. Garg; Kaiser Permanente Northern California: Sijie Zheng and Leonid V. Pravoverov; University of California, San Francisco: Chi-yuan Hsu, Raymond K. Hsu, and Kathleen D. Liu; Penn State: Nasrollah Ghahramani; University of Texas San Antonio: W. Brian Reeves; Vanderbilt: Edward D. Siew, Julia B. Lewis and Lorraine Ware; Cincinnati: Prasad Devarajan, Catherine D. Krawczeski, and Michael R. Bennett; Montreal: Michael Zappitelli; and Seattle: Mark M. Wurfel.

Disclosure

All authors have completed the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare the following: LBW has served on advisory boards for Bayer and CSL Behring and has received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and Global Blood Therapeutics. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Data Sharing

A complete deidentified patient data set can be made available through the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases data repository.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Mehta R., Pascual M., Soroko S. Spectrum of acute renal failure in the intensive care unit: the PICARD experience. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1613–1621. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palevsky P.M., Zhang J.H., O'Connor T.Z. Intensity of renal support in critically ill patients with acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:7–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellomo R., Cass A., Cole L. Intensity of continuous renal-replacement therapy in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1627–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chawla L.S., Amdur R.L., Shaw A.D. Association between AKI and long-term renal and cardiovascular outcomes in United States veterans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9:448–456. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02440213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.James M.T., Ghali W.A., Knudtson M.L. Associations between acute kidney injury and cardiovascular and renal outcomes after coronary angiography. Circulation. 2011;123:409–416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forman D.E., Butler J., Wang Y. Incidence, predictors at admission, and impact of worsening renal function among patients hospitalized with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Go A.S., Hsu C.Y., Yang J. Acute kidney injury and risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic events. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13:833–841. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12591117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalikias G., Serif L., Kikas P. Long-term impact of acute kidney injury on prognosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2019;283:48–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.01.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batlle D., Soler M.J., Sparks M.A. Acute kidney injury in COVID-19: emerging evidence of a distinct pathophysiology. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2020;31:1380–1383. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.James M.T., Samuel S.M., Manning M.A. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury and risk of adverse clinical outcomes after coronary angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:37–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.974493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen M.K., Gammelager H., Jacobsen C.J. Acute kidney injury and long-term risk of cardiovascular events after cardiac surgery: a population-based cohort study. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2015;29:617–625. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen M.K., Gammelager H., Mikkelsen M.M. Post-operative acute kidney injury and five-year risk of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke among elective cardiac surgical patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R292. doi: 10.1186/cc13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsson D., Sartipy U., Braunschweig F. Acute kidney injury following coronary artery bypass surgery and long-term risk of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:83–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.971705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh C.R., Coca S.G., Wang Y. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987–995. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.9.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Work Group KDIGO clinical practice guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Kidney Int Suppl. 2012;2:1–138. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koyner J.L., Garg A.X., Thiessen-Philbrook H. Adjudication of etiology of acute kidney injury: experience from the TRIBE-AKI multi-center study. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hsu C.Y. Where is the epidemic in kidney disease? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1607–1611. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin E.J., Muntner P., Alonso A. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2019 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e56–e528. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heywood J.T., Fonarow G.C., Costanzo M.R. High prevalence of renal dysfunction and its impact on outcome in 118,465 patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a report from the ADHERE database. J Card Fail. 2007;13:422–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fonarow G.C., Adams K.F., Jr., Abraham W.T. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: classification and regression tree analysis. JAMA. 2005;293:572–580. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parikh C.R., Puthumana J., Shlipak M.G. Relationship of kidney injury biomarkers with long-term cardiovascular outcomes after cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3699–3707. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2017010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chawla L.S., Eggers P.W., Star R.A. Acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease as interconnected syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:58–66. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1214243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoke T.S., Douglas I.S., Klein C.L. Acute renal failure after bilateral nephrectomy is associated with cytokine-mediated pulmonary injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:155–164. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ko G.J., Grigoryev D.N., Linfert D. Transcriptional analysis of kidneys during repair from AKI reveals possible roles for NGAL and KIM-1 as biomarkers of AKI-to-CKD transition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298:F1472–F1483. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00619.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christov M., Waikar S.S., Pereira R.C. Plasma FGF23 levels increase rapidly after acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2013;84:776–785. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leaf D.E., Waikar S.S., Wolf M. Dysregulated mineral metabolism in patients with acute kidney injury and risk of adverse outcomes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79:491–498. doi: 10.1111/cen.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song D., de Zoysa J.R., Ng A. Troponins in acute kidney injury. Ren Fail. 2012;34:35–39. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.623440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basile D.P., Donohoe D., Roethe K. Renal ischemic injury results in permanent damage to peritubular capillaries and influences long-term function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;281:F887–F899. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.5.F887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basile D.P., Leonard E.C., Tonade D. Distinct effects on long-term function of injured and contralateral kidneys following unilateral renal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;302:F625–F635. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00562.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pechman K.R., De Miguel C., Lund H. Recovery from renal ischemia-reperfusion injury is associated with altered renal hemodynamics, blunted pressure natriuresis, and sodium-sensitive hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1358–R1363. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.91022.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Go A.S., Parikh C.R., Ikizler T.A. The assessment, serial evaluation, and subsequent sequelae of acute kidney injury (ASSESS-AKI) study: design and methods. BMC Nephrol. 2010;11:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siew E.D., Ware L.B., Gebretsadik T. Urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin moderately predicts acute kidney injury in critically ill adults. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1823–1832. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parikh C.R., Coca S.G., Thiessen-Philbrook H. Postoperative biomarkers predict acute kidney injury and poor outcomes after adult cardiac surgery. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1748–1757. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010121302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levey A.S., Stevens L.A., Schmid C.H. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–612. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3:1–150. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McKee P.A., Castelli W.P., McNamara P.M. The natural history of congestive heart failure: the Framingham study. N Engl J Med. 1971;285:1441–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197112232852601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., Jaffe A.S. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1581–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hicks K.A., Tcheng J.E., Bozkurt B. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Data Standards (Writing Committee to Develop Cardiovascular Endpoints Data Standards) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:403–469. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fine J.P., Gray R.J. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.