Abstract

This study evaluated the effect of phytase treatment on the bioavailability of iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), zinc (Zn), and myo-inositol phosphate fractions in sorghum flour; and characterized its macronutrients and minerals. The proximate composition and mineral content indicated that, sorghum flour has a nutritional potential superior to wheat and maize. The results obtained in the solubility and dialysis assays indicated that, naturally occurring minerals (without phytase treatment) in sorghum flour, presented considerable bioaccessibility; reaching 32, 47 and 67% of dialyzable Fe, Zn, and Ca respectively. The use of phytase had a positive influence on the reduction of myo-inositol phosphates, mainly the IP6 fraction, present in sorghum flour samples, and an increase in the soluble percentage (Fe 52% for one sample, for Zn higher than 266%) and dialyzed minerals (Fe 7.8–150%; Zn 19.7 for one sample; and Ca 5–205%) for most samples. Therefore, the essential minerals naturally occurring in sorghum have an absorption potential; and the use of phytase reduced the IP6 fraction and improved the availability of the minerals evaluated.

Keywords: Iron, Zinc, Calcium, In vitro tests, Myo-inositol phosphate fractions, Sorghum flour

Introduction

Sorghum grains have been used as an alternative to maize and wheat crops in human nutrition (Dicko et al. 2006). Apart from being an easily adaptable cultivar for hot areas such as, semi-arid and tropical environments, sorghum has lower production costs, higher market availability and a nutritional value comparable to maize and wheat. Therefore, sorghum was considered as economically advantageous for food use (Kayodé 2006). Sorghum is also gluten-free, and an alternative for wheat in food production for gluten intolerant people (Schober et al. 2007).

Sorghum is also considered a good source of essential minerals, such as iron (Fe), calcium (Ca), and Zinc (Zn) (Afify et al. 2011). Thus, it can contribute to increased iron intake in human nutrition and reduce the risk of diseases, such as iron deficiency anemia, which is considered a public health problem. Furthermore, Zn and Ca (considered essential minerals) have also been reported in sorghum grains. The deficiency in these minerals is related to growth retardation, cognitive decline, and bone mass loss (Pereira and Hessel 2009).

The evaluation of mineral contribution of sorghum grains to human diet/intake and possible effects for proper organism function require further studies; not only on total mineral content, but also knowledge of the absorption estimate in the gastrointestinal tract.

Mineral absorption capacity (availability) can be estimated by determining the phytate to mineral molar ratio present in food or by in vivo (bioavailability) or in vitro (bioaccessibility) tests. However, for ethical reasons, cost, and practicality, in vitro methods are being proposed and used in several matrices to evaluate the bioaccessibility of elements (Afify et al. 2011; Hunt 2003; Ma et al. 2005). Moreover, there are studies which associate low mineral absorption to the presence of antinutritional factors, such as phytate (Ma et al. 2005; Schons et al. 2011).

Phytate is the main form of phosphorus storage in plants, cereal grains, and legumes. Phytate effects in the human body are related to their interaction with proteins, vitamins, and minerals (Afify et al. 2011). They are capable of chelating polyvalent cations, forming insoluble and non-digestible complexes, and consequently, the bioavailability of cations is reduced (Ries 2010). Studies demonstrated that, the myo-inositol phosphate fractions IP5 and IP6 are the only ones which have a negative effect on mineral absorption, the other fractions have less capacity to complex with minerals (Ries 2010).

Studies have been carried out aiming at reducing phytate levels in food, since the presence of antinutritional factors in grains and cereals affects the absorption of essential minerals. Published works have already employed different processing techniques in an attempt of minimizing the phytate effect, and consequently, improve the bioaccessibility of minerals. Treatments include; heat treatment, fermentation and germination (Afify et al. 2012; Tizazu et al. 2011). In addition, the use of phytase in cereal grains may be an alternative to reduce the antinutritional effects of phytate and improve the availability of minerals in plant foods (Wu et al. 2016). Phytase (myo-inositol hexakisphosphate phosphohydrolases) is a specific mono-ester phosphatase (Schons et al. 2011) initiating hydrolysis of phytate to inorganic phosphate, partially phosphorylated myo-inositol phosphate fractions and minerals (Ries 2010).

Norhaizan and Nor Faizadatul Ain (2009) determined phytate, iron, zinc, and calcium contents and their molar ratios in commonly consumed raw and prepared food in Malaysia (rice and rice products, wheat and wheat products, oat and chocolate). Towo et al. (2006) studied the fermentation and enzyme treatment of tannin sorghum gruels effect on phenolic compounds, phytate and in vitro accessible iron. Enzymatic dephosphorylation of phytic acid by measuring inositol tri- to hexakisphosphate (InsP3-6) degradation and iron and zinc release during microbial phytase action on wheat bran, rice bran and sorghum under simulated gastric conditions (soluble mineral analyses) were studied by Nielsen and Meyer (2016). However, scientific publications which evaluate the effects of phytase addition on the bioavailability of minerals (Fe, Zn, and Ca) in sorghum were not found.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of enzymatic treatment on mineral bioavailability (Fe, Ca, and Zn), using phytase on sorghum flour samples. Moreover, determination of myo-inositol phosphate fractions (IP6, IP5 and IP4) in sorghum flour was carried out before and after enzymatic treatment as well as the characterization of macronutrients and minerals.

Materials and methods

Sample treatment

Four varieties of sorghum were provided by EMBRAPA (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária) corn and sorghum, Brazil. They were transformed into two samples based on proximate composition similarity and mineral content and named A (composed of experimental hybrid, 1,169,026 and 1,167,026 white sorghum) and B (composed of the varieties SC-725 and BRS-310, red sorghum).

The sorghum grains were washed in running water, then dried in an oven at 50° C for 4 h. Grains were ground in a knife mill and sieved in a 20-mesh sieve. The flour was stored in plastic pots with a sanitized lid, labelled and kept in a freezer at − 18 °C according to Schons et al. (2011).

Sorghum flour samples were then divided into sorghum flour (SF) and phytase-treated sorghum flour (SF + phytase). For SF samples, proximate composition characterization, mineral (Ca, Fe, and Zn) and myo-inositol phosphates quantitation (IP6, IP5, IP4), and mineral bioavailability studies were carried out.

The phytase (NATUPHOS® 10,000 G) used was donated by BASF. Phytase treatment of sorghum flour (SF + phytase) was performed according to Ramos et al. (2012). The sorghum flour was weighed, mixed with the solution of acetic acid:sodium acetate 0.1 mol/L, pH 5.5 and 400 U of phytase/Kg of sorghum flour was applied. The samples were kept under stirring conditions at 37° C for 6 h. After, the vials were boiled for 10 min in order to cease the enzymatic reaction. The contents were transferred to petri dishes, frozen, lyophilized, ground in a knife mill and stored in a freezer in plastic pots.

Macronutrient and mineral characterization of sorghum flour

The proximate composition characterized were: moisture content (%) (method 44–10.01, AACC 2010); protein content (%) (method 46–13.01, AACC 2010); lipid content (%) (method 920.39, AOAC 1997); ash content (%) (method 08–01.01, AACC 2010), and carbohydrate content (%) by difference.

For quantification of total minerals (Fe, Zn and Ca), 0.6 g of each sample type was weighed into digestion tubes, 4 mL of nitric acid added and the tubes heated for 2 h at 100° C. Small funnels were positioned on the tube to maintain a reflux. After cooling, 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (30%) was then added. The tubes were then heated for 2 h at 130 °C. After cooling, 5 mL of water was added to the tubes and subjected to an ultrasonic bath for 5 min. The tube contents were then transferred to 25 mL volumetric flasks, and filled to maximum volume with water. The samples were filtered through filter paper (Nalgon, 9 cm diameter) and stored in a polypropylene vial for quantification of mineral content using Flame Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (FAAS) and external calibration. The calibration curves were constructed with 5 equidistant points and the concentrations varied for Fe from 0.25 to 3.0 mg/L, for Zn from 0.05 to 0.5 mg/L, and for Ca from 0.5 to 5.0 mg/L. For the determination of Ca, lanthanum oxide (final concentration of 0.5%) was used.

The myo-inositol phosphate fractions were extracted according to Sandberg et al. (1989) and quantification was carried out according to method n° 986.11, AOAC (2006).

In vitro digestion assays and effect on bioaccessibility of minerals

In order to study the bioaccessibility of minerals (Fe, Zn and Ca), the sorghum flour samples (SF, SF + phytase) were submitted to solubility and dialysis tests according Rebellato et al. (2015).

For the solubility method; five grams of each sorghum flour sample were homogenized with 30 mL of deionized distilled water, and the pH was adjusted to 2.0 with 6 M HCl. In order to develop the pepsin-HCl digestion, 0.65 mL of pepsin solution [1.6 g of pepsin, P-7000, from porcine stomach, (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, USA) in 10 mL of HCl (0.1 M)] was added. The mixture was then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in a shaking water bath. To stop intestinal digestion, the sample was maintained for 10 min in an ice bath. Prior to the intestinal digestion step, the pH of the gastric digests was raised to 5 by drop-wise addition of 1 M NaHCO3. Then 6.5 mL of the pancreatin–bile salt mixture (0.4 g of pancreatin, P-7545, from porcine pancreas and 2.5 g of bile salt porcine, B-8631, (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, USA) in 100 mL of 0.1 M NaHCO3) was added and incubation was continued for up to 2 h. To stop the intestinal digestion the sample was kept for 10 min. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 by drop-wise addition of 1.0 M NaHCO3. Of the digested sample were transferred to polypropylene centrifuge tubes (50 mL) and centrifuged at 3.500 g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatants (solubilized fraction) were lyophilized and stored for mineral content determination.

The dialysis method comprised of a gastric step common to that of the solubility method, followed by an intestinal step where dialysis is included (dialysis bag: molecular weight cut-off from 12,000 to 16,000 and porosity of 25 angstroms, Inlab, São Paulo, Brazil). The dialysis bag (containing 25 mL of water and an amount of NaHCO3 equivalent to the titrable acidity (previously measured)) was placed in the flasks, together with 35 g aliquots of the pepsin digest. Incubation was continued for 30 min, the pancreatic-bile salt mixture (6.5 mL) was added, and incubation was continued up to 2 h. After incubation, the segments of dialysis bag were removed from the flasks, washed and lyophilized. The remaining material in the flask (insoluble) was also stored. The minerals content, solubilized fraction and dialysate were analyzed by FAAS, as described above.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s test (p < 0.05), was conducted on obtained results, using the program Statistica 7.0 (Statsoft, USA).

Results and discussion

Samples characterization

Results of the proximate composition and mineral content (Fe, Zn, and Ca) of sorghum flours are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Proximate composition and mineral content (Fe, Zn and Ca) in sorghum flours

| Parameters | SF A | SF B | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 11.90 ± 0.90a | 11.50 ± 0.65a | |

| Ash (%)a | 1.32 ± 0.23b | 2.06 ± 0.11a | |

| Protein (%)a | 8.01 ± 1.02b | 13.43 ± 1.06a | |

| Lipids (%)a | 3.44 ± 0.28b | 5.06 ± 0.68a | |

| Carbohydratesb | 87.23 | 79.45 | |

| Fe (mg/100 g)a | 6.04 ± 0.31b | 8.67 ± 0.20a | |

| Zn (mg/100 g)a | 2.58 ± 0.03b | 4.62 ± 0.09a | |

| Ca (mg/100 g)a | 10.81 ± 0.24b | 19.99 ± 1.31a | |

Mean ± standard deviation. SF A: Sorghum flour composed of experimental hybrid, 1,169,026 and 1,167,026 white sorghum and SF B: sorghum flour composed of the varieties SC-725 and BRS-310, red sorghum. Fe iron, Zn zinc, Ca calcium

aResults expressed on dry basis

bCarbohydrates by difference. Mean with different letters in the same line indicate significant difference between samples (p < 0.05)

A significant difference in the composition of the two varieties studied was observed. Sample B presented higher contents of ash, proteins, and lipids compared to sample A. Those differences are due to different cultivation conditions, such as soil, climate, variety and cultivar of sorghum. The values obtained are close to the ones reported by Kayodé (2006).

Sample B presented the highest levels of Fe, Zn, and Ca, which corroborates the higher ash content. The concentrations of Fe and Zn obtained for samples A and B are close to data already reported in other studies. Afify et al. (2011) obtained Fe and Zn contents ranging from 5.54 to 7.65 mg/100 g and from 3.99 to 5.02 mg/100 g, respectively, for sorghum samples. Kayodé (2006) reported Fe contents in sorghum grains ranging from 3.00 to 11.30 mg/100 g and for Zn from 1.10 to 4.4 mg/100 g. Tizazu et al. (2011) evaluated two varieties of sorghum and found Fe contents between 7.19 and 8.21 mg/100 g, Zn contents between 1.86 and 1.97 mg/100 g, and Ca contents between 17.49 and 20.99 mg/100 g. There is a greater variation in Ca level compared to the other two minerals in sorghum and is also reported in the scientific literature. Silva et al. (2012) reported Ca content varying from 1 to 4 mg/100 g and Hamad (2006) reported Ca values varying from 5.17 to 11.26 mg/100 g, lower than the values found for the samples used in our study. Conversely, Amalraj and Pius (2015) reported Ca contents of 26.3 mg/100 g, higher than those obtained in the present study.

Furthermore, the levels of Fe and Zn obtained in sorghum flours evaluated in our study were higher than those reported for corn (2.6 and 0.7 mg/100 g, respectively) and wheat flours (1.1 and 0.9 mg/100 g, respectively) (NEPA-UNICAMP 2011). Fe content, present in iron-fortified flours (4.2 mg/100 g) marketed in Brazil and other countries, is lower when compared to the mineral content naturally present in sorghum flours. Ca content obtained was superior to the one commonly obtained for corn flour (1.1 mg/100 g) and close to the Brazilian wheat flour (20.7 mg/100 g) (NEPA-UNICAMP 2011). However, there is a greater variation in Ca level compared to the other two minerals in sorghum and is also reported in the scientific literature. Silva et al. (2012) reported Ca content varying from 1 to 4 mg/100 g and Hamad (2006) reported Ca values varying from 5.17 to 11.26 mg/100 g, lower than the values found for the samples used in our study. Conversely, Amalraj and Pius (2015) reported Ca contents of 26.3 mg/100 g, higher than those obtained in the present study.

These results indicate that sorghum flour can be considered a gluten free alternative; and as an important complement to daily essential mineral intake, where a large part of the Brazilian population and of other countries have consumptions below the recommended minimum (Pereira and Hessel 2009; Afify et al. 2011).

Phytate to mineral molar ratio and mineral availability estimation

One way of estimating the availability of minerals in plant matrices is based on phytate to mineral molar ratio. Studies report that values of phytate to Fe molar ratio above 1 indicate low iron availability absorption (Al Hasan et al. 2016; Norhaizan and Nor Faizadatul Ain 2009). Phytate to Zn molar ratios between 5 and 10 are linked to moderate Zn availability and values above 15 correspond to low Zn availability (Hunt 2003). Furthermore, phytate to Ca molar ratio above 0.24 are reported to indicate low Ca availability (Al Hasan et al. 2016). Table 2 shows the values obtained for phytate to mineral molar ratios (Fe, Zn, and Ca) in sorghum samples.

Table 2.

Phytate to mineral molar ratio in sorghum flours

| Samples | Phytate (%) | Phytate: Fe | Phytate: Zn | Phytate: Ca |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF A | 1.73 | 24.2 | 66.4 | 9.7 |

| SF B | 4.01 | 39.1 | 85.9 | 12.2 |

SF A Sorghum flour, SF B sorghum flour. Fe Iron, Zn zinc, Ca calcium

Thus, the phytate to mineral (Fe, Zn and Ca) molar ratio calculated in this study indicate low availability of these minerals from the sorghum flours evaluated. It was found that sample B presented higher total phytate content compared to sample A. Afify et al. (2011) evaluated 3 varieties of white sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) from Egypt and found phytate values ranging from 0.56 to 0.61%.

Ma et al. (2005) calculated the molar ratio Ca, Fe and Zn availability through phytate to mineral molar ratio in 60 samples of food widely consumed in China. The authors reported values of 38.6, 103.21 and 3.99 for phytate:Fe, phytate:Zn, and phytate:Ca molar ratios, respectively in sorghum samples, indicating low absorption of these minerals in the intestine. Kayodé (2006) evaluated 76 sorghum varieties and found variation from 5.0 to 56.3 in phytate to Fe molar ratios and variation from 17.1 to 127.6 in phytate to Zn molar ratios within sorghum varieties, also indicating a low availability of these minerals.

Effect of phytase treatment to sorghum flour: myo-inositol phosphate fractions and bioaccessibility of minerals

Table 3 shows the percentages of myo-inositol phosphate fractions (IP6, IP5, and IP4) in sorghum flours without and after treatment with phytase enzyme. It was observed that the sample B presented an IP6 percentage higher than sample A. Sample B contained a small percentage of IP5, which was not detected in sample A. As our study involves sorghum samples composed of different cultivars, the results of the myo-inositol phosphates could be explained by these differences proposed by Kayodé (2006).

Table 3.

Fractions of myo-inositol phosphate fractions in sorghum flours

| Samples | Treatment | IP6 | IP5 | IP4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | (%) | (%) | ||

| A | SF | 1.73 | nd | nd |

| SF + phytase | nd | nd | nd | |

| B | SF | 4.01 | 0.05 | nd |

| SF + phytase | 1.42 | nd | nd |

SF Sorghum flour. SF + phytase Sorghum flour after phytase enzyme treatment. Results expressed on dry basis. nd Not detected. Detection limit = 8 × 10–9 mol/L

A significant decrease in the myo-inositol phosphate fractions of phytase-treated sorghum flour was also verified. Sample A had a decrease in concentration to levels below the threshold of quantification of the applied analytical method; and in sample B a 65% reduction was observed after phytase treatment. Baye et al. (2015) evaluated the effect of phytase (Aspergillus niger) on the IP6 content in two samples. One sample was composed by the mixture of a kind of cereal (teff) and white sorghum in a proportion of 1:1, and the other mixture was composed by wheat and red sorghum in a proportion of 4:1.5. The authors verified that the use of phytase reduced the IP6 content present in the samples by 90%.

Phytate is considered an antinutritional factor in regards to the absorption of minerals, mainly Fe, Zn, and Ca (Wu et al. 2016). In this context, the bioaccessibility of these nutrients were evaluated; and the results are significant in estimating the effects of phytase on minerals naturally present in sorghum flours.

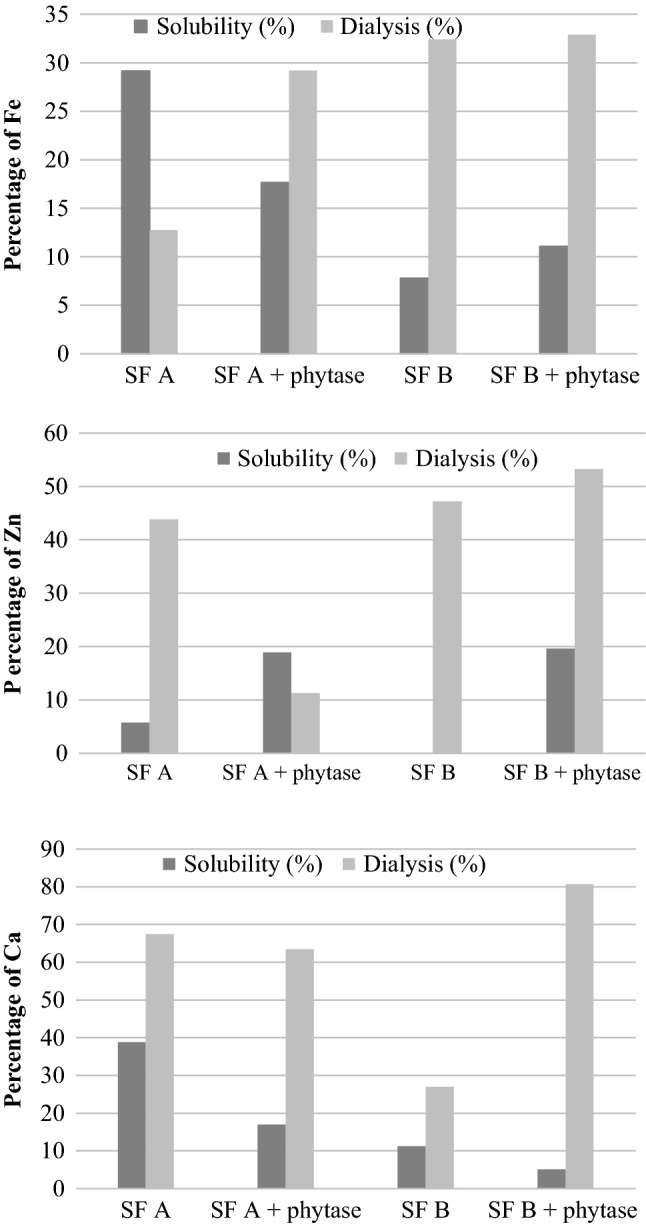

Table 4 shows the bioaccessibility of minerals (Fe, Zn and Ca) in sorghum flours before and after phytase treatment and Fig. 1 shows the percentages these minerals obtained in solubility and dialysis tests.

Table 4.

Bioaccessibility of Fe, Zn and Ca in sorghum flours

| Sorghum | Treatment | Soluble Fe | Dialyzed Fe |

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/100 g) | (mg/100 g) | ||

| A | SF | 1.76 ± 0.08a | 0.77 ± 0.14b |

| SF + phytase | 1.17 ± 0.07b | 1.93 ± 0.07a | |

| B | SF | 0.67 ± 0.07b | 2.81 ± 0.25a |

| SF + phytase | 1.02 ± 0.10a | 3.03 ± 0.18a |

| Sorghum | Treatment | Soluble Zn | Dialyzed Zn |

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/100 g) | (mg/100 g) | ||

| SFA | SF | 0.15 ± 0.02b | 1.13 ± 0.07a |

| SF + phytase | 0.55 ± 0.05a | 0.33 ± 0.03b | |

| B | SF | Nd | 2.18 ± 0.25b |

| SF + phytase | 0.96 ± 0.11 | 2.61 ± 0.18a |

| Sorghum | Treatment | Soluble Ca | Dialyzed Ca |

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/100 g) | (mg/100 g) | ||

| A | SF | 4.20 ± 0.48a | 7.29 ± 0.25a |

| SF + phytase | 2.05 ± 0.20b | 7.66 ± 0.15a | |

| B | SF | 2.24 ± 0.18a | 5.39 ± 0.85b |

| SF + phytase | 1.04 ± 0.06b | 16.45 ± 0.22a |

Mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). Fe Iron, Zn zinc, Ca calcium. SF sorghum flours. SF + phytase: sorghum flours after phytase enzyme treatment. nd Not detected. Results expressed on dry basis. Mean with different letters in the same column indicate significant difference between treatments (p < 0.05)

Fig. 1.

Percentage of Fe (iron), Zn (zinc) and Ca (calcium) obtained in solubility and dialysis tests, in sorghum flour before and after phytase treatment. SF A: sorghum flour. SF A + phytase: sorghum flour after phytase enzyme treatment. SF B: sorghum flour. SF B + phytase: sorghum flour after phytase enzyme treatment

Results show that the soluble content of Fe, Zn and Ca, and the solubility percentage, varied between the samples. Sorghum flour A presented the highest values of soluble Fe, Zn, and Ca, which corresponded to 29.14, 5.75 and 38.80% of solubility, respectively.

Regarding the effects of phytase on the bioaccessibility of minerals, based on the data obtained for solubility, it was observed that, for different samples and different minerals there was no standard behavior and for some samples and minerals, even with the reduction of myo-inositol phosphates, mainly IP6, no increase in the solubility of minerals was observed. For the soluble iron present in sample B and soluble zinc (sample A and B), phytase had a positive effect; that is, a higher solubility of minerals occurred, whereas for soluble iron in sample A and for soluble calcium in samples A and B, no increase in mineral solubility was observed.

The solubility percentages for Fe (sample A) and calcium (samples A and B) were lower after enzyme treatment. These observations are probably due to the formation of insoluble complexes of these elements with other components present in the samples, such as fibers. Sanz-Penella et al. (2012) studied the application of Bifidobacterial phytase in two samples of infant cereals and verified the effect on phytate content and bioaccessibility of minerals (Fe, Ca, and Zn). The authors verified that, the use of phytase did not significantly increase the percentage of solubility for Fe and Ca, however there was an increase in solubility percentage of zinc. Similar behavior was noted in this study. Baye et al. (2015) studied the effect of different enzymes (phytase, xylanase, cellulase, and polyphenyl oxidase) on the bioaccessibility of iron in mixtures of cereal meal (sorghum, wheat, and teff). The authors verified that phytase removal was not sufficient to improve iron solubility and dialysis percentage, since the presence of other compounds, such as polyphenols and fibers present in the matrix, had an inhibitory effect on the bioaccessibility of iron. Positive effects on iron bioaccessibility was only verified when the authors used a mixture of enzymes (phytase, xylanase, and cellulase) in the samples studied.

Afify et al. (2011) studied the percentage of Fe and Zn solubility in three varieties of white sorghum. They used washing and germination treatments for the release of minerals and compared them with the untreated sample. The authors verified that the percentage of Fe solubility varied from 8.02 to 20.75% and for Zn from 7.35 to 16.94%, depending on the treatment employed. Amalraj and Pius (2015) evaluated the effect of cooking on the bioaccessibility of calcium in several cereals, including sorghum. The authors presented soluble calcium content of 8.4 mg/100 g in raw sorghum and 9.0 mg/100 g in cooked sorghum.

For the dialysis test, it was possible to verify that sorghum flour B had the highest levels of dialyzed Fe and Zn, corresponding to 32.41 and 47.19% of dialysis, respectively. Sorghum flour A, however, presented a higher content of dialyzed Ca (67.42%). Thus, sample B presents the best bioaccessibility for Fe and Zn and sample A for Ca.

It was also found that, the concentration of dialyzable Ca present in sample A and the dialyzable iron content in sample B did not differ significantly (p > 0.05), before and after the phytase treatment. As for the other samples, a positive effect was observed when phytase was used, since the release of minerals (Fe, Zn, and Ca) occurred; that is, these minerals became more available for absorption after the use of the enzyme. Although sample A showed the lowest dialyzed iron content, the enzymatic treatment increased bioaccessibility about 1.8 times. Based on the results, enzymatic treatment was efficient for mineral availability, mainly in sample B. The enzymatic treatment has proven to be more effective for increasing solubility and dialysis of Fe and Zn in sample B, possibly due to the higher IP6 content present. For calcium, phytase addition did not generate a gain in solubility. However, there was a considerable increase in the dialyzable mineral. These observations indicate that IP6 influences the dialysis test results more and less on the solubility of minerals. It is important to note that the dialysis assay results in more representative data, as it is based on the human gastrointestinal system; however, phytase treatment can cause improvement on bioaccessibility of these minerals. Furthermore, Fe and Zn seem to be more prone to lower solubility in the presence of high IP6 content, than Ca, a factor that, we believe, should be related to the binding force of phytate with the mineral, which is lower for calcium. The levels of dialyzed Fe and Zn obtained in our study were higher than those reported by Tripathi and Platel (2013) which evaluated Fe and Zn bioaccessibility in sorghum flour and obtained values of 0.39 and 0.43 mg/100 g, respectively. Tripathi and Chetana (2010) also evaluated the bioavailable Zn content in sorghum flour and obtained the value of 0.37 mg/100 g. Amalraj and Pius (2015), when studying calcium bioaccessibility, reported values of dialyzed calcium and its percentage in sorghum samples, raw and cooked, of 6.8 and 7.1 mg/100 g, corresponding to 26 and 26.5%, respectively. Similar contents of dialysate Ca were obtained in this study for the samples of sorghum flour A and B. Wu et al. (2016) studied the influence of six different genotypes on sorghum samples, on tannin levels, phytate, minerals (Fe, Ca, P and Zn) and bioaccessibility of iron (as a percentage of dialysis). The results obtained for total phytate content varied from 1.06 to 1.74% and for Fe, Ca, and Zn, the values within the genotypes varied from 1.47 to 4.78, 5.08–9.45 and 1.23–2.44 mg/100 g, respectively, and the dialysis percentage for Fe varied from 0.87 to 5.94%. The authors conclude that, the genotype had a significant effect on the evaluated parameters of sorghum samples. Sanz-Penella et al. (2012) applied Bifidobacterial phytase in two samples of infant cereals and studied the effect on the phytate content and dialysis of Fe, Ca and Zn. The authors verified that phytase treatment did not increase significantly dialysis percentages of the minerals in comparison to the samples that did not received any treatment.

Although the phytate to Fe molar ratio is equivalent within the samples and indicates low availability, the bioaccessibility of mineral was higher in sample B and the enzymatic treatment was not efficient for increasing dialyzed Fe. Similar results were obtained by Baye et al. (2015), the authors reported that, the phytase treatment in samples reduced the IP6 fraction by 90%, the molar fraction obtained from IP6:Fe was lower than 1. However, no improvement was observed in the bioaccessibility test of the evaluated mineral.

Although phytate:Ca molar ratio indicated low mineral availability, sorghum flour A presented a result of dialyzed Ca (> 65%) higher than sample B (27%). Once again, it was found that, the complexity of the in vitro digestion process simulation and the same type of food (different varieties), submitted to the same bioaccessibility simulation test, generated different results for dialysis percentages.

Samples A and B presented divergent results regarding phytase use and bioaccessibility of Ca. For sample A, there was no difference in phytase application in relation to calcium release, while for B sample; phytase application released higher quantity of Ca. It is probably due to the higher IP6 fraction present in the sample, before the enzymatic treatment.

Conclusion

The proximate composition indicates that, sorghum flour presents nutritional potential, similar or superior, to wheat and corn.

Regarding Fe, Zn, and Ca content, the consumption of gluten-free sorghum flour, may contribute to the recommended daily intake for these minerals, with values higher than those reported for corn and wheat found in the samples studied.

Estimates of mineral availability, based on the phytate to mineral molar ratio, indicated low availability for Ca, Fe, and Zn; and the percentage solubility data, for most of the samples and minerals studied, indicated, on average, solubility below 20%. However, the dialysis tests indicated that, minerals, naturally present in sorghum flour, had on average 40% of dialysate fraction, indicating satisfactory availability. Considering that the dialysis test is better for simulating the digestion process (compared with solubility), it is possible conclude that the minerals studied may have relevant absorption when the sorghum flour, after phytase treatment, is consumed.

The enzymatic treatment effect was efficient for reducing of myo-inositol phosphate fractions, mainly IP6 found in the samples, and provided an increase in the dialyzable fraction for all studied minerals. Thus, the use of phytase can be considered an alternative process to improve mineral availability.

Therefore, the use of phytase is an alternative for reducing the effects of antinutritional factors on the availability and absorption of minerals present in sorghum flour.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to FAPESP for financial support n° 2013/16643-8, Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel, Brazil (CAPES) Finance Code 001 for the financial support and the EMBRAPA (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária) corn and sorghum (Brazil) for donating the samples.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- AACC . Approved methods of analysis. 11. Saint Paul: AACC International; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Afify A-M, El-Beltagi H, Abd El-Salam S, Omran A. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, phytate and phytase activity during soaking and germination of white sorghum varieties. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25512. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afify AE-M, El-Beltagi H, El-Salam S, Omran A. Effect of soaking, cooking, germination and fermentation processing on proximate analysis and mineral content of three white sorghum varieties (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2012;40:92–98. doi: 10.15835/nbha4027930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al Hasan SM, Hassan M, Saha S, Islam M, Billah M, Islam S. Dietary phytate intake inhibits the bioavailability of iron and calcium in the diets of pregnant women in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nutr. 2016;2:24. doi: 10.1186/s40795-016-0064-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amalraj A, Pius A. Influence of oxalate, phytate, tannin, dietary fiber, and cooking on calcium bioavailability of commonly consumed cereals and millets in India. Cereal Chem J. 2015;92:389–394. doi: 10.1094/cchem-11-14-0225-r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . AOAC - Association of Official Analytical Chemists official methods of analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists. 16. Gaithersburg: AOAC International; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. Gaithersburg: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Baye K, Guyot J-P, Icard-Vernière C, Rochette I, Mouquet-Rivier C. Enzymatic degradation of phytate, polyphenols and dietary fibers in Ethiopian injera flours: effect on iron bioaccessibility. Food Chem. 2015;174:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva CS, Queiroz VAV, Simeone MLF, de Guimaraes CC, Schaffert RE, Rodrigues JAS, de Miguel RA (2012) Teores de minerais em linhagens de sorgo para uso na alimentação humana. In: CONGRESSO NACIONAL DE MILHO E SORGO, 29, Águas de Lindóia. Diversidade e Inovações Na Era Dos Transgênicos: Resumos Expandidos. Campinas: Instituto Agronômico; Sete Lagoas: Associação Brasileira de Milho e Sorgo, 6. http://ainfo.cnptia.embrapa.br/digital/bitstream/item/66110/1/Teores-minerais.pdf

- Dicko MH, Gruppen H, Traoré AS, Voragen AGJ, van Berkel WJH. Sorghum grain as human food in Africa: relevance of content of starch and amylase activities. Afr J Biotechnol. 2006;5:11. [Google Scholar]

- Hamad RME (2006) Preliminary Studies on the Popping Characteristics of Sorghum Grains [Al-Zaiem AI- Azhari University]. https://inis.iaea.org/collection/NCLCollectionStore/_Public/40/091/40091489.pdf

- Hunt JR. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78:633s–639s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.3.633S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayodé APP (2006) Diversity, users’ perception and food processing of sorghum: implications for dietary iron and zinc supply [Wageningen University. Promotor(en): Tiny van Boekel, co-promotor(en): Rob Nout; Anita Linnemann. - Wageningen]. https://edepot.wur.nl/26991

- Ma G, Jin Y, Piao J, Kok F, Guusje B, Jacobsen E. Phytate, calcium, iron, and zinc contents and their molar ratios in foods commonly consumed in China. J Agric Food Chem. 2005;53:10285–10290. doi: 10.1021/jf052051r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEPA-UNICAMP . Tabela Brasileira de Composição de Alimentos-TACO. 4. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas-UNICAMP Campinas; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen AV, Meyer AS. Phytase-mediated mineral solubilization from cereals under in vitro gastric conditions. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;96:3755–3761. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norhaizan MEJ, Nor Faizadatul Ain AW. Determination of phytate, iron, zinc, calcium contents and their molar ratios in commonly consumed raw and prepared food in malaysia. Malays J Nutr. 2009;15:213–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira TC, Hessel G. Deficiência de zinco em crianças e adolescentes com doenças hepáticas crônicas. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2009;27:7. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos GDM, Ascheri JLR, da Silva LG, Damaso MCT, de Sousa GF, Couri S. Estabilidade da fitase de Aspergillus niger 11T53A9 ao armazenamento e sua aplicação na hidrólise do ácido fítico na farinha de sorgo. Revista Brasileira de Agrociência Pelotas. 2012;18(2–4):95–106. doi: 10.18539/cast.v18i2.2499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rebellato AP, Pacheco BC, Prado JP, Lima Pallone JA. Iron in fortified biscuits: a simple method for its quantification, bioaccessibility study and physicochemical quality. Food Res Int. 2015;77:385–391. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ries EF (2010) Estudo da produção, caracterização e aplicação de nova fitase de Saccharomyces cerevisiae [Universidade Estadual de Campinas,]. http://repositorio.unicamp.br/jspui/handle/REPOSIP/256627

- Sandberg AS, Carlsson NG, Svanberg U. Effects of inositol Tri-, Tetra-, Penta-, and hexaphosphates on in vitro estimation of iron availability. J Food Sci. 1989;54:159–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1989.tb08591.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Penella JM, Frontela C, Ros G, Martinez C, Monedero V, Haros M. Application of bifidobacterial phytases in infant cereals: effect on phytate contents and mineral dialyzability. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60:11787–11792. doi: 10.1021/jf3034013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schober TJ, Bean SR, Boyle DL. Gluten-free sorghum bread improved by sourdough fermentation: biochemical, rheological, and microstructural background. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:5137–5146. doi: 10.1021/jf0704155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schons PF, Ries EF, Battestin V, Macedo GA. Effect of enzymatic treatment on tannins and phytate in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) and its nutritional study in rats. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2011;46:1253–1258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2011.02620.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tizazu S, Urga K, Belay A, Abuye C, Retta N. Effect of germination on mineral bioavailability of sorghum-based complementary foods. Afr J Food Agric Nutr Dev. 2011;11:5083–5095. doi: 10.4314/ajfand.v11i5.70438. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Towo E, Matuschek E, Svanberg U. Fermentation and enzyme treatment of tannin sorghum gruels: effects on phenolic compounds, phytate and in vitro accessible iron. Food Chem. 2006;94:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.11.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi B, Chetana PK. Fortification of sorghum (Sorghum vulgare) and pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) flour with zinc. J Trace Elem Med Biol Organ Soc Miner Trace Elem. 2010;24:257–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi B, Platel K. Feasibility in fortification of sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L. Moench) and pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) flour with iron. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2013;50:220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.05.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Johnson SK, Bornman JF, Bennett SJ, Singh V, Simic A, Fang Z. Effects of genotype and growth temperature on the contents of tannin, phytate and in vitro iron availability of sorghum grains. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:12. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]