Abstract

Purpose of the Review:

Partnerships between academia and the community led to historic advances in HIV and paved the way for ongoing community engagement in research. Three decades later, we review the state of community engagement in HIV research, discuss best practices as supported by literature, explore innovations and identify ongoing gaps in knowledge.

Recent Findings:

The community of people living with and at risk for HIV remains actively involved in the performance of HIV research. However, the extent of participation is highly variable despite long standing and established principles and guidelines of Good Participatory (GPP) and Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR). Current literature reveals that known barriers to successful community engagement continue to exist such as power differences, and poor scientific or cultural competency literacy. Several high quality studies share their experiences overcoming these barriers and demonstrate the potential of CBPR through reporting of qualitative and quantitative outcomes.

Summary:

Greater time and attention should be placed on the development of community engagement in HIV research. A large body of literature, including innovative cross-cutting approaches, exists to guide and inform best practices and mitigate common barriers. However, we recognize that true growth and expansion of CBPR within HIV and in other fields will require a greater breadth of research reporting qualitative and quantitative outcomes.

Keywords: Community engagement, HIV research, Community Based Participatory Research, Good Participatory Practices

Introduction

“We condemn attempts to label us as ‘victims’, a term which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally ‘patients,’ a term which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are ‘People with AIDS.’” Statement from the advisory committee of the People with AIDS (The Denver Principles)1

The accomplishments achieved in the field of HIV/AIDS are nothing short of remarkable. A fatal diagnosis is now a chronic disease, with estimates suggesting people living with HIV today may achieve a near normal lifespan2. Rapid advancements in the lifesaving combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) occurred largely because vocal, credible and effective community and patient advocates demanded it and collaborated with researchers, and industry to achieve it3. Initially, HIV researchers were siloed from the community, and relationships were contentious4. Faced with the suffering and deaths of friends and family, activists refusing to be passive “victims” of AIDS embraced self-empowerment and effectively organized. The Denver Principles formed in 1983, served as the foundation of the activist movement and detailed how PLWH expect to be treated, how PLWH should respond to the AIDS crisis and the human rights they demand (Table 1)1,5,6.

Table 1:

The Denver Principles1

| Statement from the advisory committee of the People with AIDS | We condemn attempts to label us as “victims,” a term which implies defeat, and we are only occasionally “patients,” a term which implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are “People With AIDS.” |

| Recommendations for all people |

|

| Recommendations for people with AIDS |

|

| Rights of people with AIDS |

|

To address the ongoing outcry of activists, the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) recommended including community members at AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) meetings7. Formalized community involvement in HIV research began soon after that with the first federally funded and mandated community advisory boards (CABs) in 19898,9. Notable contributions that community members drove were elimination of a placebo arm in indinavir efficacy studies (ACTG 320), the insistence that only combination therapy with three drugs be evaluated rather than comparisons to one or two drugs (ACTG 343), and the development of the ACTGs participant’s bill of rights, a distinct document separate from the informed consent form9. The role of the community in HIV research continued to expand with the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study that welcomed community involvement in the planning and implementation of research10. Community participation in HIV research culminated with the early vaccine trials for HIV prevention. Researchers truly embraced the community and partnered with their CABs to identify potential study problems, inform recruitment practices, monitor research and ultimately disseminate study findings11,12. It is widely perceived that without CAB involvement, participant recruitment and the overall quality of the research would have been compromised9. Today CABs are an essential component of most clinical trial networks (HIV Vaccine Trials Network, HIV Prevention Trials Network and the ACTG).

Despite this history and experience, the effectiveness of community involvement in research may be limited based on the relationship of the research team with the study’s CAB and by common misconceptions about CBPR (Table 2). Some researchers may view CABs in clinical trials as “window-dressing” or a box to be checked, or may not have the resources or training to allocate to CAB development and management9. Premature closure of several large-scale International biomedical HIV prevention trials13 due to concerns about exploitation of vulnerable persons14 demonstrated the necessity of community involvement at all stages of research to improve ethical practices around cultural, language and literacy differences15. This experience also re-demonstrated the power of advocacy16 and the importance of transparent and effective communication between researchers, participants and the community17,18. As a direct result, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) developed a systematic framework of Good Participatory Practice (GPP) that includes principles of community based participatory research (CBPR) and training for research teams performing biomedical HIV prevention work 19-22. Over a decade has passed since those events and the development of GPP, yet recent community voices (particularly in the area of aging with HIV23) suggests principles of GPP and CBPR may not be widely embraced (Table 3)19,24. The purpose of this review is to a) characterize the current state of community involvement in research involving people living with and at risk for HIV, b) identify best practices towards meaningful, diverse and effective community involvement in HIV research, c) highlight innovative approaches to advance CBPR and c) identify current gaps in the literature.

Table 2:

Countering Common Misconceptions in Community Engagement

| Community engagement is not recruitment for clinical research | Community engagement and recruitment are fundamentally activities and serve different purposes. Recruitment is about engaging populations of interest, screening for eligibility, and enrolling participants based on inclusion and exclusion criteria |

| Community engagement and community advisory boards serve related but different purposes | CABs provide input into the research process, as a sounding board, for protocol review and represent a critical safeguard in research. |

| Community engagement and education is not merely community service | Community engagement and education is more than community service and should be properly valued. Community engagement involves managing expectations, sharing information, meaningful dialogue and mutual literacy and understanding. Community engagement is about intentionally shifting power to the community. |

| Community engagement is not research or ethics | Research is systematic work that involves methods and informed consent. Ethics is the study of what ought to be done. |

CABs – community advisory boards

Table 3:

Principles of Community Based Participatory Research and Good Participatory Practices

| Community Based Participatory Research21 | Good Participatory Practices16 |

|---|---|

|

|

Progress, but room for improvement

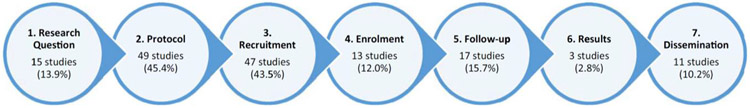

A recent systematic review sought to examine stakeholder (defined as an individual or group affected by the outcomes of a project) engagement in HIV clinical trials25. Of 917 citations generated by literature review, 108 were included in the analysis. Most of the studies were performed in high (44.4%) and middle income (27.8%) countries. Reasons for engagement were predominantly associated with study performance (to understand factors affecting recruitment) but also included identification of barriers and facilitators to trial participation, to inform the ethical conduct of the trial, and to develop trial tools. Based on engagement by research stage, stakeholders were primarily utilized to inform trial protocol development (45.5%) and trial recruitment (43.5%). Only 13.9% of studies engaged stakeholders to participate in generating research questions, 12% in study enrollment, 15.7% in follow-up, 2.8% in interpreting results and 10.2% in trial results dissemination (Figure 1, reproduced with permission). Overall, this review revealed that the community engagement standard outlined by GPP guidelines continues to be inconsistently and incompletely applied19-22.

Figure 1.

Summary of the purpose of stakeholder engagement by clinical research stage. Reproduced with permission 22

Moving beyond conventional (top-down) approaches to community engagement 25

Power inequities due to expert knowledge and training as well as differences in circumstances often lead to top-down engagement with the community26,27. That is, an expert develops an idea, tests the idea in the community (i.e. focus groups) and ultimately implements the research. Bottom-up approaches start with the community to identify the problem (e.g., include persons living with HIV, patient advocates, clinicians and researchers), involves the community in iterative development of solutions or approaches and engages the community in the performance of research28. When these approaches are blended, through a) academic and community flexibility and power sharing, b) training in community developed cultural competency and/or c) in the intentional identification of scientific leadership who are also part of the community, engagement as defined by CBPR principles can be successful 29. Although top-down engagement remains the predominant approach25, several high quality studies were recently published that demonstrate the impact of true collaborative work30-32. One such study evaluated a bottom up approach to improving maternal and child health services utilization in the Greater Accra and Western regions of Ghana33. The authors engaged community groups and associations to identify gaps in service delivery in healthcare facilities across Ghana. The intervention began with recruitment and training of facilitators that were assigned one per community group. Second, healthcare quality proxies assessed by members of the partnering community groups were gathered. These included satisfaction or disappointment with non-technical components of service delivery (i.e. staff attitude towards clients, staff punctuality etc.). Review of these scores with heath managers, and other authorities to develop action plans was then regularly followed up by community quality care champions to ensure implementation of action plans. Finally, health facilities that were perceived by community members to have improved were recognized for their efforts. Ultimately this approach, compared to control facilities with no intervention, resulted in greater increases in child immunizations and HIV testing of women33.

Bi-directional commitment, flexibility, and power sharing remain key to success

Many community members and organizations engaged by academia may be motivated by generativity or service34. However at some point to be effective, the community needs to move beyond this and become engaged in research35. This involves ensuring that community members are well funded and supported, understand research ethics, are able to identify potential harms to their community and are willing and able to provide feedback to researchers36. Achieving this requires flexibility, power sharing (shared decision making), and education to improve science and ethics literacy for the community and CBPR and cultural competency for research teams.27,37 Switzer et al communicated the impact of bi-directional commitment, flexibility, and power sharing in a recent case study of substance users participating in CBPR38. Feedback from the community revealed that participation in research sometimes leads to stress that results in unintended consequences for health and contributes to inconsistent engagement, prompted the researcher to seek out novel approaches to CBPR 39. Through collaboration, the research team provided flexibility in involvement via a “drop-in” approach and opportunities to socialize and participate in fun activities38. Specifically, the research team employed diverse facilitated activities that were arts-based to guide discussion of research rather than the traditional meeting format. This ultimately resulted in expansion of opportunities for greater diversity of involvement and deeper connections between community advisors and the research team.

There is value in having difficult conversations to improve effectiveness and foster growth

As in any relationship, tensions may arise between members of the community and the research team. Several publications shared their experiences embracing “productive tensions” and their approaches to dealing with conflict and fostering difficult conversations between the community and research teams. HEADS up!, a CBPR study exploring the lived experience of HIV AIDS Neurocognitive Disease (HAND) 40 included teams of researchers, HIV providers, nurses, social workers and peer research associates. Peer research associate recruitment occurred within the clinic sites in which they received care. Tensions within the team arose, around the candid experiences of peer research associates and the clinical services they received. Tensions also arose around the diagnosis of unintended real-world consequences of a HAND diagnosis in a participant (i.e. loss of driver’s license). A separate study in South Africa relayed issues of tension around cultural differences between practices in the home and research center, and miscommunication between staff and participants 26. In both studies, recognizing and addressing tensions through meaningful conversations enabled the community and the research teams to move forward with stronger dynamics and relationships. The performance of CBPR may be accompanied by tensions between team members but the pursuit of meaningful dialogue based on mutual literacy and understanding may improve research effectiveness and foster growth.

Innovative approaches to enhance CBPR

Several published studies introduced innovative approaches to CBPR to improve reach to difficult to engage populations and overcome some of the innate difficulties of CBPR. Active community engagement is considered essential in the performance of culturally competent research specifically when targeting vulnerable and hard to reach persons. As such, novel approaches such as use of mobile and social media outreach are actively being explored41. Establishment of a virtual panel is one innovative way to include difficult to reach populations. The University of New South Wales (UNSW) developed a community reference panel that exists as a virtual network of persons across Australia to be engaged in research design. This panel, originally established to improve the uptake of testing and treatment of sexually transmitted infections among Aboriginal Australians, now exists to support community involvement in research that embraces populations that are difficult to engage such as persons who inject drugs, are incarcerated, and sex workers. Researchers desiring to engage with these populations use panel coordinators with established relationships with the community to engage the community42. Another novel approach is implementing crowdsourcing (the process where a group rather than an individual finds a solution, solves a problem, or completes a task) as bottom-up approach to facilitate research engagement43. Integrating principles of CBPR with crowdsourcing recently resulted in the participation of a wide range of ages and significant representation from Black and White participants to better understand public perspectives of HIV cure-related research44.

Innovations are also being developed around improving trust and understanding in the performance of CBPR in HIV research. One proven approach to overcoming power dynamics between researchers and the community is through enhancing understanding of the community experience using arts-based methods (digital storytelling, photography, drawing, poetry writing, or performance) or participatory visual method (PVM)45. PVM is a collaborative process where participants and facilitators use visual methods, like art or video production, to communicate personal and potentially sensitive stories and represents a way to involve marginalized communities and enhance inclusivity46,47. Utilization of this approach to impact ART adherence effectively engaged PLWH in clinic to stimulate dialogue around the treatment of HIV in South Africa48. These examples demonstrate the importance in pursuing ongoing innovation to enhance CBPR.

Gaps in Knowledge and Key Research Priorities

Recent literature continues to demonstrate the value of academic and community partnerships but several gaps in knowledge still exist. The majority of publications on community engagement are narrative and summarize experiences and lessons learned27,40,49,50. Very few evaluate true effectiveness of academic-community partnerships in the delivery of project and public health relevant outcomes that clearly communicate the added value of these partnerships, especially to researchers, funders, and difficult to reach populations51. Empirically evaluated outcomes such as improved recruitment of persons historically difficult to engage, new funding opportunities that arose directly from partnerships, enhancement/growth of the workforce, mutual gain, and changes in public health outcomes such as reduced HIV incidence14,30 should be evaluated to enhance collective “buy-in” 32.

Researchers outside of the field of HIV are beginning to evaluate the role of human-centered design or HCD (also known as user-centered design) as a potential method to mitigate limitations of CBPR practices (specifically by optimizing the time required to build deep community trust and relationships and improving participation of minority opinions and voices)52. HCD originated from the field of human-computer interaction but the basic tenets embrace co-operative design (co-design), participatory design and “customer-centered design”.53 Given its origins in technology development, there may be specific value in its integration into innovations evaluating the impact of technology to enhance CBPR.53 Additionally, HCD acknowledges diversity in experiences and opinions of the community and as such utilizes methods (i.e. co-design workshops) that rapidly engage and target a wide-range of experiences and opinions to capture the varying experiences of PLWH. This approach may be particularly advantageous in highly heterogeneous populations such as persons aging with HIV54 to ensure research priorities are not just influenced by the most involved and vocal but reflect the greater community. For example, PLWH who aged with HIV were exposed to longer durations of HIV viremia, more toxic ART, and significant peer losses that contribute to multi-morbidity, polypharmacy, disability and loneliness55-58. PLWH that acquire HIV in later life when immediate and safer ART are standard of care may not experience similar morbidity. Additionally, many older PLWH may not be aware that the challenges they are facing as they age are related to HIV (multi-morbidity, social isolation, treatment fatigue) and thus may be most productively engaged with methods that incorporate education. HCD at its core is inclusive and iterative and as such welcomes diverse viewpoints and experiences to ultimately deliver a refined and nuanced research agenda or intervention59-61.

Lastly although principles of CBPR and GPP appear broadly embraced by the HIV prevention community, extension into other areas of HIV research is limited. We must remember that GPP were developed in the context of large-scale biomedical HIV prevention trials51. Specific areas that may benefit from greater community engagement include HIV cure-related research62-64, aging with HIV23,65 ending the epidemic66,67, and emerging technologies like long acting ART because they deal with sensitive topics, or potentially vulnerable populations that may not be well understood by research teams. For example, the Last Gift study at the University of California San Diego engaged the local community advisory board in elaborating ethical considerations for HIV cure-related research at the end of life63. They discovered that the community had highly differing opinions on their specific approach, but also acknowledged PLWH as true experiential experts. The Last Gift team is utilizing the differing opinions to inform the implementation of funded research68 and in the development of future studies specifically around controversial practices such as interruption of beneficial HIV treatment69. Other successful efforts within the ACTG have involved community representatives as co-investigators on clinical trial protocols to understand participants’ perspectives and lived experiences in HIV cure-related research and research around aging with HIV69. As the field of HIV research continues to grow and innovate, we will need to build the capacity of biomedical researchers to value community input and communicate scientific findings in community-friendly ways.

Conclusion

History has demonstrated to us that partnerships between academia and the community are capable of accomplishing tremendous positive change. While great strides are being made in the performance of CBPR and GPP, there remains room for improvement. To truly encourage comprehensive and expansive CBPR and GPP requires ongoing robust reporting of qualitative and quantitative outcomes directly attributed to community engagement and the development of innovative communication approaches (like PVM) 32,48. However, meaningful and effective academic and community partnerships take time, financial resources, training in community engagement and cultural competency, infrastructure building and institutional support 70. Thus advancement of CBPR and GPP in HIV research will require the development and integration of specific community engagement standards and requirements and support to do so from funders, conferences, research journals and institutions23,25,53.

Key points.

Partnerships between the community and academia has historically resulted in critical advances and ground-breaking outcomes in the field of HIV.

Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) and Good Participatory Practices (GPP) established decades ago continue to be embraced in HIV research, but are often partially or incompletely implemented.

Historical barriers to the implementation of CBPR and GPP continue to exist, and novel approaches should be pursued to overcome them.

Future work should embrace selection and reporting of quantitative and qualitative outcomes of community engagement to enhance “buy-in” from the HIV research community at large.

Acknowledgements

Financial Support and Sponsorship: This publication resulted in part from grant support for MYK from the NIA (R03 AG060183) and is supported by the San Diego Center for AIDS Research (SD CFAR), an NIH-funded program (P30 AI036214), which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, NHLBI, NIA, NIGMS, and NIDDK.

Dr. Moore is supported by P30 AG059299.

Disclosure of Funding: MYK receives research funding to the institution from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare and served on an advisory board for Gilead Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: MYK receives research funding to the institution from Gilead Sciences and ViiV Healthcare and served on an advisory board for Gilead Sciences.

References

- 1.Anonymous. The Denver Principles. (1983).

- 2.Prevention C.f.D.C.a. HIV Care Saves Lives Infographic. in Vital Signs, Vol. 2019 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epstein S The construction of lay expertise: AIDS activism and the forging of credibility in the reform of clinical trials. Science, technology & human values 20, 408–437 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacQueen KM & Auerbach JD It is not just about “the trial”: the critical role of effective engagement and participatory practices for moving the HIV research field forward. Journal of the International AIDS Society 21(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merson MH, O’Malley J, Serwadda D & Apisuk C The history and challenge of HIV prevention. The lancet 372, 475–488 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poindexter CC The human rights framework applied to HIV services and policy. Handbook of HIV and social work: Principles, practice, and populations, 59–73 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rubin R Collaboration and Conflict: Looking Back at the 30-Year History of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Jama 314, 2604–2607 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox LE, Rouff JR, Svendsen KH, Markowitz M & Abrams DI Community advisory boards: their role in AIDS clinical trials. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS. Health Soc Work 23, 290–297 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss RP, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. American journal of public health 91, 1938–1943 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senterfitt J Collaboration with constituent communities in the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS). in AHSR & FHSR Annual Meeting Abstract Book, Vol. 13 22–23 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanchard L Community assessment and perceptions: preparation for HIV vaccine efficacy trials. (Beyond Regulations: Ethics in Human Subjects Research; Chapel Hill, NC: …, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strauss R Community advisory board–investigator relationship in community-based research. (Beyond Regulations: Ethics in Human Subjects Research; Chapel Hill, NC: …, 1999). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haire BG Because we can: clashes of perspective over researcher obligation in the failed PrEP trials. Dev World Bioeth 11, 63–74 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacQueen KM, Eley NT, Frick M & Hamilton C Using theory of change frameworks to develop evaluation strategies for research engagement: results of a pre‐pilot study. Journal of the International AIDS Society 21, e25181 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allman D, Ditmore MH & Kaplan K Improving ethical and participatory practice for marginalized populations in biomedical HIV prevention trials: lessons from Thailand. PLoS One 9, e100058 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mills EJ, et al. Designing research in vulnerable populations: lessons from HIV prevention trials that stopped early. Bmj 331, 1403–1406 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh JA & Mills EJ The abandoned trials of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: what went wrong? PLoS medicine 2, e234 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack N, Robinson ET, MacQueen KM, Moffett J & Johnson LM The exploitation of “Exploitation” in the tenofovir prep trial in Cameroon: Lessons learned from media coverage of an HIV prevention trial. Journal of empirical research on human research ethics : JERHRE 5, 3–19 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.UNAIDS. Good participatory practice: guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention trials, (UNAIDS, 2007). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannah S, Warren M & Bass E Global implementation of Good Participatory Practice Guidelines for biomedical HIV prevention research: charting progress and setting milestones. Retrovirology 9, P240 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller L, et al. P15–24. Good participatory practice guidelines begin to take root. Retrovirology 6, P225 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guenter D, Esparza J & Macklin R Ethical considerations in international HIV vaccine trials: summary of a consultative process conducted by the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Journal of medical ethics 26, 37–43 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karris MY, et al. Encouraging Community Engagement in the Performance of Research at the Intersection of HIV and Aging. AIDS research and human retroviruses (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA & Becker AB Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual review of public health 19, 173–202 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **25.Day S, et al. Stakeholder Engagement for HIV Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review of the Evidence in JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL AIDS SOCIETY, Vol. 21 108–108 (JOHN WILEY & SONS LTD THE ATRIUM, SOUTHERN GATE, CHICHESTER PO19 8SQ, W: …, 2018).- Critically reviews HIV clinical trials and the extent of community engagement. Great resource for developing a birds eye view of the state of community engagement today.

- 26.de Wet A, et al. The trouble with difference: Challenging and reproducing inequality in a biomedical HIV research community engagement process. Global public health, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *27.Ivey KD, Murry K, Dragan D & Campbell M “All Voices Matter”: Perspectives on Bridging the Campus-to-Community Gap. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 10, 12 (2018).- Narrative article that describes the experiences of a comprehensive community engagement program that demonstrates the progress that can be achieved when these principels are embraced and supported by institutions.

- 28.Fraser ED, Dougill AJ, Mabee WE, Reed M & McAlpine P Bottom up and top down: Analysis of participatory processes for sustainability indicator identification as a pathway to community empowerment and sustainable environmental management. Journal of environmental management 78, 114–127 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheeler DP, et al. Building effective multilevel HIV prevention partnerships with Black men who have sex with men: experience from HPTN 073, a pre‐exposure prophylaxis study in three US cities. Journal of the International AIDS Society 21(2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *30.Lippman SA, et al. Village community mobilization is associated with reduced HIV incidence in young South African women participating in the HPTN 068 study cohort. J Int AIDS Soc 21 Suppl 7, e25182 (2018).- Work out of the HPTN is important because this group at large are expets in CBPR and GPP. This study specifically connects public health outcomes (i.e. lower HIV incidence) with community mobilization.

- 31.Milnor JR, Santana CS, Martos AJ, Pilotto JH & Souza CTVd. Utilizing an HIV community advisory board as an agent of community action and health promotion in a low-resource setting: a case-study from Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Global health promotion, 1757975919854045 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron D, et al. Collateral benefits: how the practical application of Good Participatory Practice can strengthen HIV research in sub‐Saharan Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society 21, e25175 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **33.Alhassan RK, et al. Impact of a bottom-up community engagement intervention on maternal and child health services utilization in Ghana: a cluster randomised trial. BMC public health 19, 791 (2019).- An example of the use of quantitative measurement of the impact of community engagement on public health outcomes.

- 34.Boyd N, Nowell B, Yang Z & Hano MC Sense of community, sense of community responsibility, and public service motivation as predictors of employee well-being and engagement in public service organizations. The American Review of Public Administration 48, 428–443 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhodes SD, et al. Community-engaged research as an approach to expedite advances in HIV prevention, care, and treatment: A call to action. AIDS Education and Prevention 30, 243–253 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyirenda D, et al. ‘We are the eyes and ears of researchers and community’: Understanding the role of community advisory groups in representing researchers and communities in Malawi. Developing world bioethics 18, 420–428 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Weger E, Van Vooren N, Luijkx K, Baan C & Drewes H Achieving successful community engagement: a rapid realist review. BMC health services research 18, 285 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Switzer S, Chan Carusone S, Guta A & Strike C A Seat at the Table: Designing an Activity-Based Community Advisory Committee With People Living With HIV Who Use Drugs. Qual Health Res 29, 1029–1042 (2019).- An excellent example of the research team listening to the needs and requests of the community and collectively developing solutions to enhance inclusivity and trust.

- 39.Attree P, et al. The experience of community engagement for individuals: a rapid review of evidence. Health & social care in the community 19, 250–260 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **40.Ibáñez-Carrasco F, et al. Creating Productive Tensions: Clinicians Working with Patients as Peer Researchers in a Community-Based Participatory Research Study of the Lived Experience of HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder (HAND). The Canadian Journal of Action Research 19, 53–72 (2018).- Describes challenges and successes based on the reearch teams experiences and provides recommendations to sustain peer engagement from peer research associates and others on the research team.

- 41.Makila E, et al. Community Engagement in HIV Biomedical Prevention Research: Use of Mobile Technologies and the Asset Based Community Development Approach in AIDS RESEARCH AND HUMAN RETROVIRUSES, Vol. 34 198–198 (MARY ANN LIEBERT, INC 140 HUGUENOT STREET, 3RD FL, NEW ROCHELLE, NY 10801 USA, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker M, Beadman K, Griffin S, Beadman M & Treloar C Involving peers in research: the UNSW community reference panel. Harm reduction journal 16, 1–3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tang W, et al. Crowdsourcing to Improve HIV and Sexual Health Outcomes: a Scoping Review. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mathews A, et al. Crowdsourcing and community engagement: a qualitative analysis of the 2BeatHIV contest. Journal of virus eradication 4, 30 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Q, Coemans S, Siegesmund R & Hannes K Arts-based methods in socially engaged research practice: A classification framework. Art/Research International: A Transdisciplinary Journal 2, 5–39 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell CM & Sommer M Participatory visual methodologies in global public health. (Taylor & Francis, 2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gubrium AC, Fiddian-Green A, Jernigan K & Krause EL Bodies as evidence: Mapping new terrain for teen pregnancy and parenting. Global Public Health 11, 618–635 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Treffry-Goatley A, Lessells RJ, Moletsane R, de Oliveira T & Gaede B Community engagement with HIV drug adherence in rural South Africa: a transdisciplinary approach. Medical humanities 44, 239–246 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beard J, et al. Challenges of developing a district child welfare plan in South Africa: lessons from a community-engaged HIV/AIDS research project. Global health promotion, 1757975918774569 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newman PA, Slack CM & Lindegger G Commentary on “A Framework for Community and Stakeholder Engagement: Experiences From a Multicenter Study in Southern Africa”. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 13, 333–337 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **51.MacQueen KM, Bhan A, Frohlich J, Holzer J & Sugarman J Evaluating community engagement in global health research: the need for metrics. BMC Med Ethics 16, 44 (2015).- The authors provided potential indicators for evaluating contribution of community engagement to ethical goals

- 52.Norman D The design of everyday things: Revised and expanded edition, (Basic books, 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavery JV Building an evidence base for stakeholder engagement. Science 361, 554–556 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levin J & Montano M What Aging With HIV Means in the Year 2019. AIDS research and human retroviruses (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erlandson KMK, Maile Y HIV and Aging: Reconsidering the Approach to Management of Co-Morbidities. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Erlandson KM, Schrack JA, Jankowski CM, Brown TT & Campbell TB Functional impairment, disability, and frailty in adults aging with HIV-infection. Current HIV/AIDS Reports 11, 279–290 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greene M, et al. Geriatric syndromes in older HIV-infected adults. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 69, 161 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greene M, et al. Loneliness in older adults living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior 22, 1475–1484 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gee L Human-centered design guidelines. Learning spaces 10(2006). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cooley M Human-centered design. Information design, 59–81 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 61.IDEO. The Little Book of Design Research Ethics, (2016).

- 62.Dubé K, et al. Acceptability of Cell and Gene Therapy for Curing HIV Infection Among People Living with HIV in the Northwestern United States: A Qualitative Study. AIDS research and human retroviruses (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Dube K, et al. Ethical considerations for HIV cure-related research at the end of life. BMC Med Ethics 19, 83 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Danielson MM & Dube K Michael’s Testimonial. Ann Intern Med 170, 511–512 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marg LZ, et al. A Multidimensional Assessment of Successful Aging Among Older People Living with HIV in Palm Springs, California. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 66.Valdiserri RO & Holtgrave DR Ending HIV in America: Not Without the Power of Community. AIDS and behavior, 1–5 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saafir-Callaway B, et al. Longitudinal outcomes of HIV- infected persons re-engaged in care using a community-based re-engagement approach. AIDS Care, 1–7 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gianella ST, Jeff; Smith Davey. The Last Gift. Taking part in HIV cure research at the end of life in Positively Aware, Vol. 29 (Chicago, IL, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dube K, Barr L, Palm D, Brown B & Taylor J Putting participants at the centre of HIV cure research. Lancet HIV 6, e147–e149 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **70.Caron RM, Ulrich-Schad JD & Lafferty C Academic-community partnerships: Effectiveness evaluated beyond the ivory walls. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship 8, 14 (2019).- Qualitative evaluation to examine characteristics of partnerships between academia and the community. Provides insight into current cross-disciplinary challenges that exist.