Abstract

Background

Involving adults lacking capacity (ALC) in research on end of life care (EoLC) or serious illness is important, but often omitted. We aimed to develop evidence-based guidance on how best to include individuals with impaired capacity nearing the end of life in research, by identifying the challenges and solutions for processes of consent across the capacity spectrum.

Methods

Methods Of Researching End of Life Care_Capacity (MORECare_C) furthers the MORECare statement on research evaluating EoLC. We used simultaneous methods of systematic review and transparent expert consultation (TEC). The systematic review involved four electronic databases searches. The eligibility criteria identified studies involving adults with serious illness and impaired capacity, and methods for recruitment in research, implementing the research methods, and exploring public attitudes. The TEC involved stakeholder consultation to discuss and generate recommendations, and a Delphi survey and an expert ‘think-tank’ to explore consensus. We narratively synthesised the literature mapping processes of consent with recruitment outcomes, solutions, and challenges. We explored recommendation consensus using descriptive statistics. Synthesis of all the findings informed the guidance statement.

Results

Of the 5539 articles identified, 91 met eligibility. The studies encompassed people with dementia (27%) and in palliative care (18%). Seventy-five percent used observational designs. Studies on research methods (37 studies) focused on processes of proxy decision-making, advance consent, and deferred consent. Studies implementing research methods (30 studies) demonstrated the role of family members as both proxy decision-makers and supporting decision-making for the person with impaired capacity. The TEC involved 43 participants who generated 29 recommendations, with consensus that indicated. Key areas were the timeliness of the consent process and maximising an individual’s decisional capacity. The think-tank (n = 19) refined equivocal recommendations including supporting proxy decision-makers, training practitioners, and incorporating legislative frameworks.

Conclusions

The MORECare_C statement details 20 solutions to recruit ALC nearing the EoL in research. The statement provides much needed guidance to enrol individuals with serious illness in research. Key is involving family members early and designing study procedures to accommodate variable and changeable levels of capacity. The statement demonstrates the ethical imperative and processes of recruiting adults across the capacity spectrum in varying populations and settings.

Keywords: Palliative care, Terminal care, Decision-making, Consent, Methods, Ethics, Systematic review, Consensus

Background

There is an urgent need for evidence on best practice in palliative care. The projected increases in global serious health-related suffering demand immediate action. By 2060, an estimated 48 million people will die globally with serious related-suffering, representing an 87% increase from the 26 million in 2016 [1]. Failing to respond will see 80% of people globally with little or no access to palliative care services and treatment [2]. A major barrier in research on palliative care is ethical concerns about the perceived vulnerability of adults with serious illness and including them in research, particularly if the person also has impaired mental capacity [3]. Exclusion of adults with impaired capacity to consent for themselves impedes evidence-based care and treatment that is applicable across the illness trajectory and end of life (EoL) [4]. New interventions require robust evaluation to examine benefit and potential of harm for the population intending to benefit [5, 6]. Studies, especially clinical trials in palliative care, are often compromised by insufficient sample size to detect change [7–13], and impaired understanding of legislation governing research involving adults with impaired capacity [14]. The ethical challenges of recruiting individuals with impaired capacity are examined across fields involving adults with serious illness including palliative care [15], dementia [16–18], mental health [19], and intensive care [20]. Systematic reviews have considered consent processes in specific conditions (e.g. dementia [21], schizophrenia [22]) and aspects of involving adults lacking capacity in research (e.g. capacity assessment [22], enhancing informed consent with older people [23, 24], and strategies for designing research studies [25] and increasing the recruitment rate in palliative care [26]). But, in palliative care, intervention studies are few and often exclude adults lacking capacity, for example in the dying phase [27]. There is literature from both within and outside the field of palliative care that could inform much needed guidance on best practice on processes of consent across the capacity spectrum in serious illness. This study aimed to determine how best to include individuals with impaired capacity in research on EoLC by identifying challenges for and solutions to processes of consent across the capacity spectrum. This paper reports the integrated results from a systematic review and transparent expert consultation to form the MORECare_Capacity statement on processes of consent in research on EoLC. This furthers the Methods Of Researching End of Life Care (MORECare) statement on evaluating complex circumstances in EoLC [28] by giving detailed consideration on processes of consent for adults with serious illness across the capacity trajectory. The MORECare statement omitted this area, focusing on outcome measurement, response shift and attrition, integrating mixed methods and economic evaluation.

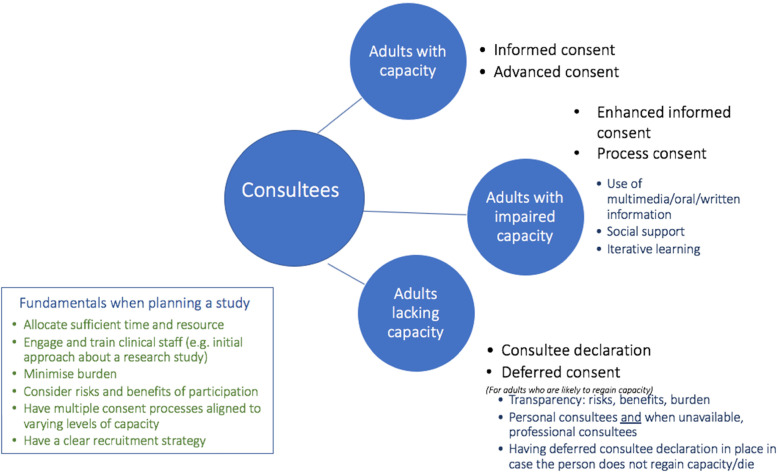

In this paper, ‘capacity’ refers to mental capacity to make an informed decision regarding research participation. ‘The spectrum of capacity’ of individuals ranges from potentially impaired, and anticipated to have impaired capacity, to lacking capacity. The legislation governing involvement of adults lacking capacity in research and terminology is jurisdiction specific. In this paper, the term ‘consultee’ (someone who has capacity) is used to encompass the different terms used in respective jurisdictions including but not limited to proxy-decision maker, personal consultee and nominated consultee. A distinction is made between a personal consultee (e.g. family member) and a nominated consultee (e.g. health professional) [29]. ‘The process of consent’ refers to the steps taken to ensure that an eligible research participant is sufficiently informed about the purposes, content, affiliations of the study, and their right to withdraw from the study at any point, enabling them or their consultee to decide freely about research participation [30].

Methods

Study design

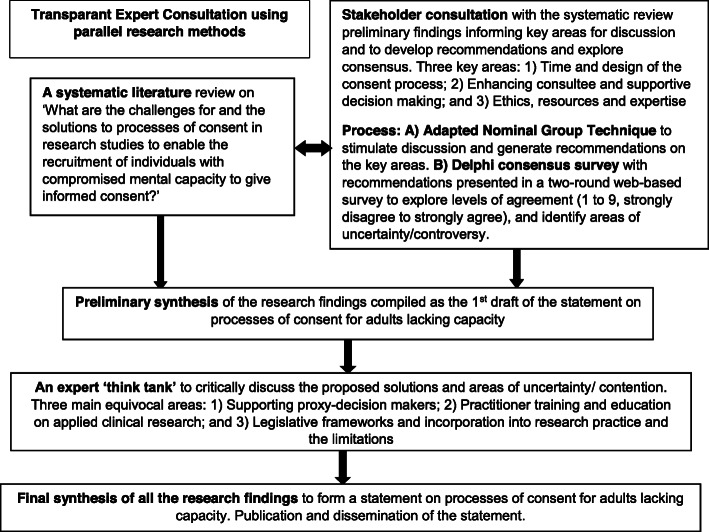

We used a parallel iterative research design detailed in Fig. 1. We used methods of systematic literature review to identify and map the challenges and solutions for processes of consent for adults with impaired capacity, and the MORECare transparent expert consultation (TEC) to debate key areas [28] of uncertainty/contention. The TEC involved expert stakeholder consultations using consensus methods of modified nominal group technique to generate recommendations [31], and then presenting the recommendations in an online Delphi survey to explore levels of agreement [32]. We held a final expert think-tank to explore areas of contention/uncertainty and synthesise the findings to develop the statement. King’s College London Research Ethics Committee approved the TEC component (ref no. BDM/10/11-90).

Fig. 1.

Overview of the study design

Systematic review

Design

We used systematic review method of narrative synthesis to systematically identify, appraise, and synthesise quantitative and qualitative literature [33]. Methods of analysis and inclusion criteria were pre-defined in the study protocol. Reporting followed the PRISMA guidance [34] (see Additional file 1: Table S1).

Eligibility criteria

Population

Adults (≥ 18 years old) with impaired capacity encompassing declining capacity (e.g. mild to moderate dementia), fluctuating capacity (e.g. delirium), and lack of capacity (e.g. dying, advanced dementia) are included.

Context

The scoping of the literature identified areas recruiting adults lacking capacity with serious illness in research. We included studies from palliative care, mental health (delirium, dementia, learning disabilities), or emergency medicine/critical care.

Interest

Studies discussing consent in its various forms (e.g. informed, advanced, proxy) and impaired mental capacity are included. We did not restrict by health or behaviour outcome. We focused on research studies investigating either of the following: (i) methods for involving adults with impaired capacity in research, (ii) implementing research methods to enable recruitment, or (iii) exploring public attitudes and ethical issues on involvement in research.

Design

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental, mixed method, or observational qualitative or quantitative designs are included. We included published study protocols that reported the methods of consent to enhance understanding for the main study. We excluded systematic reviews but used relevant systematic reviews for reference chaining by screening the cited publications for eligibility. We excluded opinion pieces and commentaries and non-English language papers. Studies concerning treatment/clinical decision-making or bioethics were out of scope.

Search strategy

We developed search strategies for each of the population groups—palliative care, mental health (including dementia), and emergency medicine/critical care. MeSH terms for the palliative care group included ‘Terminally ill’ or ‘Palliative Care’ AND ‘Decision making’ or ‘Mental Competency’ AND ‘Informed consent’ or ‘Third-party consent’. Key search terms were used as free-text, and with use of truncation symbol to retrieve variations in the terminology. Search terms were piloted pre-study and mapped to assess their relevance and specificity, and refined working with a specialist librarian (see Additional file 2: Table S2 - electronic search terms). We searched four electronic databases: MEDLINE (1966–Present), EMBASE (1947–Present), PsychINFO (1887–Present), and CINAHL (1937–Present), and supplemented with referencing chain, grey literature electronic survey, and expert recommendations. The last search was run on 30 October 2018.

Quality appraisal

Study risk of bias was assessed using the validated QualSyst review tool suitable for quantitative and qualitative studies [35] by one reviewer (EY, IT, CJE), and a random 10% sample checked by a second author (CJE). Scores that diverged by > 10% were discussed within the research team. A single quality appraisal was undertaken for studies reported in multiple publications (e.g. protocol paper and a main trial results paper). The QualSyst assessment criteria include 14 items for quantitative studies and 10 items for qualitative studies. Each item is scored from 0 to 2 (0, not present; 1, partial; 2, yes; or not applicable). The percentage of the total possible score indicates the quality grade: < 50%, low; > 50 and < 70%, medium; or > 70%, high. Study designs were categorised using the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) grade system [36] (see Additional file 2: Table S3).

Data screening, extraction, and analysis

Referencing software (Endnote version x8) [37] was used to manage a database of search findings and remove duplicates. Title and abstract screen by one reviewer (EY/KS) and second independent review of 20% to test the application of the eligibility criteria (CJE). Titles/abstracts that met the review criteria, or if insufficient information to determine eligibility, were subject to full-text screening. Full-text articles were single-screened by three reviewers (EY/KS/CJE). Full-text papers with uncertain eligibility were reviewed by two reviewers and eligibility agreed (EY/KS with CJE). A standardised data extraction form was developed and piloted based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Revie Group’s data extraction template (see Additional file 2: Table S4). Data included the study design and aim, the population and context, method(s) of consent, recruitment rate, and challenges and solutions. Study data were extracted by one reviewer (CJE, EY, KS) and checked by a second reviewer (CJE, EY, KS). We contacted two authors to check availability of the publications in English. Using narrative synthesis [33], textual descriptions from extracted data for all studies were mapped to form matrices for studies innovating research method, studies using innovative methods, or considered ethics, legislation, or public attitudes. Each matrix was analysed and coded in Microsoft Excel using thematic analysis to explore prominent themes. Higher quality studies were valued with a greater strength in the final synthesis.

Transparent expert consultation

The TEC aimed to enhance the systematic review findings by exploring the application of the findings in research studies and areas little considered or uncertain in the evidence. The TEC explored researchers’ and service users’ perspectives on recruiting individuals with impaired capacity in research on EoLC. The TEC sought to generate recommendations on processes of consent to enable recruitment and explore the level of consensus.

Setting and participants

Participants were purposively sampled based on their expertise in conducting research involving adults with impaired capacity (including ethicists), caring for patients with advanced disease, or a service user/carer (e.g. palliative care services), or a voluntary sector representative (e.g. Alzheimer’s Society). Participants were invited to the workshops held in the Cicely Saunders Institute, King’s College London. Eligible participants included members of the project’s expert panel (project applicants), Project Advisory Group (invited experts in, for example, ethics, and PPI and voluntary sector representatives) [see the “Acknowledgements” section], respondents in the systematic review grey literature survey and invited ethicists, clinicians, commissioners, researchers, members of ethical committees, policymakers, and service user and lay voluntary sector representatives. Identified professional participants received email invitations for the workshop. Service user and lay voluntary sector representatives were recruited via voluntary sector groups including, for example, Alzheimer’s Society and Independent Cancer Patients’ Voice. The respective organisations circulated the invitation letter to their members targeting those known to have an interest/experience of either a carer for an adult with impaired capacity, being a patient with progressive illness, or supporting research involving adults with impaired capacity.

The TEC used four stages:

Stage I: Identifying critical issues. The initial workshop focused on critical issues identified from the systematic review preliminary findings and expert opinion (e.g. areas with limited empirical evidence and relevance in the processes of consent for adults across the capacity spectrum).

Stage II: Stakeholder workshop. Participants received a pre-workshop briefing pack detailing the aim, critical issues, and workshop format. The workshop comprised presentations on the critical areas overviewing findings from the systematic review followed by structured group discussion involving 10–14 participants focusing on one of the critical areas. Group discussions were digitally recorded. We used a structured nominal group process facilitated by a member of the research team. The facilitator guided participants through a structured process of (1) a brief discussion, (2) individual writing of recommendations and ranking, and (3) participants in turn stating their highest ranked recommendations until individual lists were exhausted (or time exceeded) [31]. Scribes wrote the recommendations and ranking on a flipchart, and each small group discussed and agreed on the final priority order, then presented and discussed with the whole group. Participants individually listed and ranked recommendations from one to five (highest to lowest) on structured A4 sheets detailing the respective group question, ranking scale and boxes to list recommendations, rank, and detail rationale.

Stage III: Delphi online consensus exercise. This is a two-round online consensus exercise [32]. Recommendations generated in the workshop were posted online to the workshop participants, members of the expert panel and Project Advisory Group, and respondents to the grey literature survey. Participants received a personalised email invitation and reminder after 2 weeks. The online participants anonymously ranked, from one to nine (strongly disagree to strongly agree), the extent they agreed with a recommendation and used free-text spaces to comment on each recommendation. Findings from round 1 informed requirements to revise recommendations where comments suggested ambiguity. Round 2 re-presented the revised recommendations and the median score for each recommendation from round 1. Participants again indicated their level of agreement ranked from one to nine and provided free-text commentary on, for example, rationale for ranking score.

Stage IV: Expert ‘think-tank’. The expert ‘think tank’ workshop aimed to aid data synthesis and inform the solutions and recommendations in the statement by critically considering areas of contention/uncertainty identified in the consensus exercise and systematic review findings. The think-tank aimed to understand the debates surrounding these areas, the strengths and limitations of the evidence, and the solutions for practice. Participants were purposively selected from the workshop participants based on expertise, e.g. ethicists, lay voluntary sector representative, researcher, and clinician. Think-tank participations received a briefing report that summarised for the respective area the systematic review findings on the challenges and solutions identified in the evidence base, and the recommendations and level of agreement from the consensus exercise. The think-tank used a format of presentations and debate, drawing on structured nominal group process to facilitate participant agreement on the top two or three key solutions for each area, and commentary on their thinking. Participants discussed and debated these areas in groups of 6–7. Discussions were digitally recorded, and scribes recorded on flipchart the key debates.

Data analysis

Individual recommendations from the workshop and their ranking were entered in Excel spreadsheets with assigned participant identification numbers. Two researchers (CJE, KS) coded and arranged recommendations by themes, duplicates were combined, and recommendations arranged by priority ranking (1 highest to 5 lowest). Free-text comments were collated. Digital recordings were reviewed to inform understanding on the recommendations and debates presented, with key points noted on the Excel spreadsheet for the respective recommendation. The recommendations retained participants’ original language where possible with amendments guided by the expert panel to enhance clarity and avoid repetition. The final recommendations were those ranked the highest (≤ 3) and reviewed and agreed by the expert panel and piloted (e.g. for clarity), and then posted on the online consensus survey. Analysis of the consensus survey-scaled data used descriptive statistics (frequencies and medians) and plots (box and whisker plots) of interquartile ranges to analyse and interpret levels of agreement. We used a conventional categorisation to interpret agreement (indicated, equivocal, or not indicated) and strength of agreement (strict or broad) used in previous consensus studies [28]. Table 1 details the categories by the respective median region and IQR [38]. Narrative comments were collated by recommendation, and themes identified to understand the issues raised and provide illustrative examples [32].

Table 1.

Levels of consensus and agreement by median regions and IQR [38]

| Median regions and IQR | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 7–9 | Recommendation indicated |

| 4–6 | Recommendation equivocal |

| 1–3 | Recommendation not indicated |

| IQR inoneregion | Strict agreement for recommendation |

| IQR inanythree-point region | Broad agreement for recommendation |

IQR interquartile range

Results

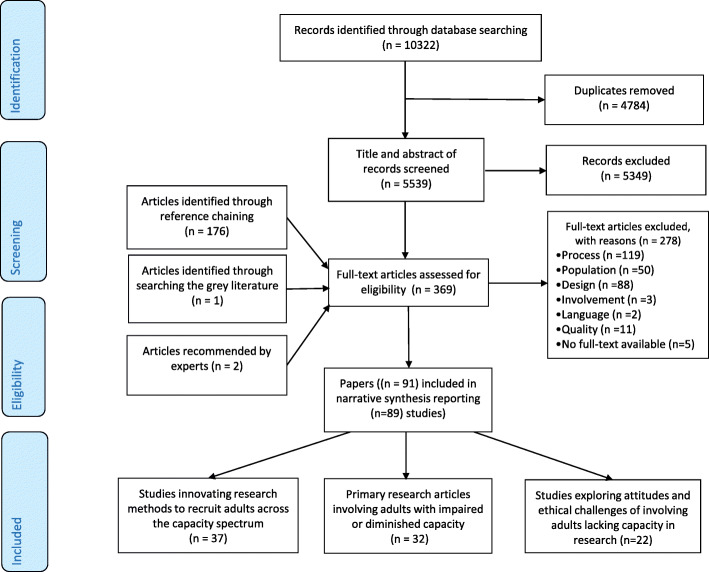

Systematic review search results

The electronic database searches identified 5539 abstracts after removal of duplicates with a further 179 publications identified from other sources (see Fig. 2). Ninety-one publications met the eligibility criteria, reporting 89 studies. Two studies included a protocol and main results papers [39–42]. Studies were conducted mainly in dementia (n = 23), palliative care (n = 16), and intensive care (n = 15) (Table 2). Publications increased over time with the majority published after 2010 (n = 54). Studies were conducted mainly in the USA (n = 35), UK (n = 29), or Canada (n = 9) (see Table 2 and Table 3, and Additional file 3: Table S8). The studies formed three main areas of (1) innovating research methods to recruit adults across the capacity spectrum, (2) applying consent processes across the capacity spectrum in studies on serious illness, and (3) public attitudes on involving adults lacking capacity in research.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flow diagram

Table 2.

Population of interest categorised by the study focus

| Patient population of interest | Study focus on processes of consent | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovating research methods (n = 37) | Applying research methods (n = 30) | Attitudes and ethical considerations (n = 22) | Total studies (n = 89)* | |

| Palliative care/cancer | 6 [43–48] | 8 [49–56] | 2 [57, 58] | 16 |

| Dementia | 13 [59–71] | 10 [40, 42, 72–79] | 1 [80] | 24 |

| Geriatric care | 2 [81, 82] | 3 [83–85] | 0 | 5 |

| Parkinson’s disease | 1 [86] | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Cerebral ischaemic stroke | 2 [87, 88] | 0 | 1 [89] | 3 |

| Mental health | 6 [90–95] | 2 [96, 97] | 1 [98] | 9 |

| Delirium | 2 [99, 100] | 2 [101, 102] | 0 | 4 |

| Intensive care | 5 [103–107] | 5 [108–112] | 4 [113–116] | 14 |

| General population | 0 | 0 | 13 [117–129] | 13 |

Table 3.

Studies innovating research methods to recruit adults across the capacity trajectory (grouped by solutions) (n = 37 studies)

| Authors, country, EPOC grade | Year | Study design and aim | Setting | Sample description | Consent process for adults across the capacity spectrum | No. patients/eligible (%) | Key findings, challenges, and solutions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced informed consent processes | |||||||

| Dobratz et al. [43], USA, B3 | 2003 | Retrospective research study with a vulnerable population to describe issues and dilemmas related to non-participation, attrition, and need for assistance in research with vulnerable home hospice participants. | Home or preferred setting of home hospice agency recipients from two metropolitan settings | Palliative care: home hospice agency recipients |

Informed consent: study was explained to all participants over the phone. Participants provided ‘telephone consent’. During the study visit, participants provided informed consent. Adults with declining capacity |

97/113 (86%) |

Key findings: five people who agreed to take part unable to provide informed consent due to distress; five other participants with cognitive impairment precluded informed consent. Solutions: participants require regular monitoring of their physical and psychological symptoms, oversampling to anticipate and plan for withdrawals, and cognitive assessment tool for all potential participants regardless of diagnosis (e.g. brain metastases), and careful screening of psychological behaviours to reduce distress. Participant positive feedback about the study. |

| Siminoff et al. [71], the Netherlands, C1 | 2004 | Qualitative study examining the factors that were important in making research participation decisions among patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD), cancer, critically ill children. | Unclear | Dementia: patients with Alzheimer’s disease with cognitive impairment |

Informed consent: potential subjects were given information about the study by phone. During the conversation, if patients met initial eligibility criteria and expressed continued interest in participation, attended the clinic for formal informed consent procedure. The consent form was read to the subjects and questions were addressed throughout and at the end of reviewing the written consent form. Adults with declining capacity |

46 AD patients, mean age 72, 91.3% white, 61% female, 78.3% married, 63.6% more than a high school education, 65.6% income > $25,000 |

Key findings: key elements of informed consent. Information—the AD (mean = 1.78) group received more information about voluntary participation than the paediatric (mean = 1.27) group (F = 4.1; p < .05). Confidentiality—were most likely discussed with the AD group (87%) versus the cancer (22%) and paediatric (9.2%) groups (χ2 = 85.24; p < .001). Discussion of ‘no treatment’ as a viable option occurred most often in the AD group (58.7%) versus the adult cancer (41.6%) and paediatric (3.9%) subjects (χ2 = 46.38; p < .001). AD subjects received the most information about voluntary participation and confidentiality, and no treatment option. Challenge: lack of discussions about confidentiality and no treatment as an option. |

| Buckles et al. [59], USA, B3 | 2003 | Longitudinal study of healthy ageing and dementia to evaluate understanding of informed consent by older participants across a range of dementia severity using a brief test on the elements of informed consent for a low-risk study. | Not stated | Dementia: 415 participants, 165 without dementia, 250 with dementia |

Informed consent and assessment dementia severity with Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR), MMSE Adults with declining capacity |

415 |

Key findings: after adjusting for education, performance on the test varied with dementia severity in mean differences and by correlation. All non-demented and very mildly demented participants and 92% of mildly demented participants provided correct answer for at least 8 of 10 true-false items, whereas only 67% of the moderately demented participants achieved this level of accuracy. Solutions: by moderate dementia stage, involvement of a responsible caregiver in consent process should be mandatory. |

| Mangset et al. [103], Norway, C1 | 2008 | Qualitative study to explore critically ill patients’ experience with the principle of informed consent in a clinical trial and their ability to give valid informed consent. | 2 Norwegian hospitals | Stroke: stroke patients who were invited to take part in an international stroke trial |

Informed consent Adults with declining capacity |

11 |

Key findings: the results challenge the validity of informed consent for an experimental trial obtained from critically ill patients, and the concept of the consent as a contract obtained on a rational basis between equal and autonomous parties. Challenges: most patients did not understand the purpose of randomisation or the concept of clinical equipoise. The main reasons for consent were patients’ dependency on the doctor, their need for a trustful relationship, and seeing study information as a recommendation. |

| Chouliara et al. [44], UK, C1 | 2004 | Individual interviews on some ethical and methodological challenges involved in conducting research with older people with cancer by referring to researchers’ experiences in an on-going research project. | Care of the elderly wards and a cancer centre | Cancer: people with cancer > 65 years old |

Informed consent: obtained after explaining the project verbally and written. Family members involved to assist patient decision-making. In instances where they felt like the patient was not understanding, they also involved. Adults with declining capacity |

37/50 (74%) |

Key findings: mean age 74.3 (SD = 7.5), MMSE 24.0 (4.1)—mild dementia. Involvement of vulnerable, elderly individuals was considered ethical in a low-risk qualitative study. Challenges: Fluctuating capacity, fatigue, frailty, physical and cognitive limitations. Solutions: a semi-structured interview schedule allowed patients to talk freely. A rigorous procedure to obtain valid consent, including the viewpoints of all the parties involved. |

| Mittal et al. [61], USA, B3 | 2007 | RCT comparing two processes of consent to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of two enhanced consent procedures for patients with Alzheimer’s disease or mild cognitive impairment that used either a PowerPoint presentation or printed consent form. | 2 medical centres | Dementia: referred patients with possible or probable Alzheimer’s disease (MMSE ≥ 19), mild cognitive impairment |

Enhanced informed consent. PowerPoint slideshow presentation (no written consent form) (SSP) or enhanced written consent procedure (researcher reads the information aloud, while the potential participant can follow from their own copy with large fonts). Followed with MacCAT-CR assessment of capacity, then repeat of either of the consent processes. MMSE ≥ 19 Adults with impaired capacity |

35 | Key findings: participants improved their understanding scores after verbal re-explanation of consent information. There were no significant differences in level of understanding among those in the SSP versus the EWCP conditions at either trial, but we found the SSP took significantly less time to administer. |

| Rubright et al. [63], USA, A3 | 2010 | RCT testing whether a memory and organisational aid improves AD patient performance on measures of capacity and competency to give informed consent. | Alzheimer’s disease centre | Dementia: patients with Alzheimer’s disease | Enhanced informed consent with memory and organisational aid or standardised informed consent: intervention group received the additional aid which summarised the key elements in the drug Z-298 informed consent form. It presented information in the same sequence and header titles as presented in the informed consent form. The text simplified important points from the consent form using language at a sixth grade reading level. All participants went through a capacity assessment. | 80/112 (71%) of potential AD patients, 30/33 (91%) of cognitively normal older adults |

Key findings: the intervention group was more likely to be judged competent than the control group (χ2 = 8.2, df = 1, p = 0.004) and had higher scores on MacCAT-CR measure of understanding (z = 2.86, p = 0.004). This RCT shows that a memory and organisational aid tailored to the distinctive cognitive patterns of AD patients can improve the ability of patients with very mild to early moderate AD to provide their own informed consent to enrol in an early-phase clinical trial. Challenge: this tool was designed specifically for AD patients and may not generalisable to other populations. Use of formal capacity assessments should not be treated with strict cut-off measurements. More challenging for high-risk trials. Solutions: for patients at an early phase of AD, capacity can be enhanced. |

| Ford et al. [86], USA, B2 | 2008 | RCT to evaluate the effects of social support on comprehension and recall of consent form information in a study of Parkinson’s disease patients and their caregivers. | Medical centre | Parkinson’s disease: Parkinson’s disease patients (mean age 71 (SD 8.6) years) and their caregivers |

Enhanced informed consent: in the social support group, patient-caregiver pair was asked to complete the consent form in the same room compared to the control group who completed the forms in separate rooms. Adults with impaired capacity |

136/143 (95%) |

Key findings: 1-week follow-up, no significant differences in Quality of Informed Consent (QuIC) scores between participants receiving the social support intervention and the control group. Regardless of the group allocation, participants scored approximately 50% of the QuIC questions. But the findings showed that comprehension of consent form information was increased through the social support intervention in a ‘real-world’ clinical setting. Challenge: initial comprehension was low and remained relatively consistent within the 1-month period. Solutions: informational support provided by family caregivers. Caregivers who scored high on correct QuIC were associated with patient participants who with high QuIC scores, e.g. understanding information. |

| Campbell et al. [94], South Africa, B3 | 2017 | Case-control study exploring if using iterative learning improves participants’ understanding of the research study and predictors of better understanding of the study at the initial screening. | Psychiatric hospitals and clinics | Mental health: patients with psychosis/schizophrenia |

Enhanced informed consent (with iterative learning): following explanation, University of California, San Diego Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent Questionnaire (UBACC) is administrated, if the person achieves > 14.5 demonstrating capacity to consent; informed consent is provided. Adults with impaired capacity |

1056 participants—528 matched cases and controls. (target was 181 pairs) |

Key findings: before iterative learning, 55% of cases and 33% of controls were scoring lower than the cut-off point for study participation. After iterative learning, only 7% of cases and 3% of the controls were unable to consent to participate. Iterative learning process improved decisional capacity and understanding of the study in both cases and controls. This process is repeated after iterative learning. Solutions: the study recruiters play a significant role in managing the quality of the informed consent process. |

| Palmer et al. [62], USA, A3 | 2018 | RCT to evaluate the efficacy of a multimedia-aided enhanced consent process incorporating corrective feedback, compared with routine consent, among individuals with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease and non-neuropsychiatric comparison (NC) subjects. | Unclear | Dementia: individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (mild to moderate) |

Enhanced informed consent: the enhanced consent procedure expanded on routine consent by adding a more structured, iterative process and by incorporating multimedia tools into the consent presentation. Participants were randomised to routine consent and enhanced consent procedures for participating in a hypothetical RCT lower risk (FDA-approved medication) or a high risk (phase 2 immunotherapy). Assessment of capacity using MacCAT-CR. Adults with impaired capacity |

248—134 control, 114 Alzheimer’s disease | Key findings: regardless of whether randomised to the lower or higher risk protocol type, participants who received the enhanced consent procedure did not demonstrate significantly better decisional capacity scores compared with those who received the routine consent procedure. Findings could be due to rapid forgetting. |

| Moser et al. [93], USA, B2 | 2006 | Quasi-experimental, pre-post study to determine whether a brief intervention could improve decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia. | Unclear | Mental health: individuals with schizophrenia |

Enhanced informed consent: a very brief (less than 30 min), semi-individualised intervention consisting of a computerised presentation of the hypothetical study information in a bulleted, simplified format, with one key point per slide. Participants viewed the presentation and read along as the examiner read aloud each slide. Following the educational remediation, the examiner reviewed with the participant all MacCAT- CR ‘understanding’ items for which the participant did not receive maximum credit. Participants received both a standardised intervention, individualised discussion, and corrective feedback regarding the aspects of the research protocol that they found confusing. The MacCAT-CR interview was then repeated to assess participants’ decisional capacity following the educational remediation. Finally, the examiner a briefer structured interview designed to assess the adequacy of participants’ understanding of the hypothetical study. Adults with fluctuating capacity |

30 individuals with schizophrenia and 30 healthy comparison participants |

Key findings: at follow-up, the schizophrenia group had improved significantly on understanding (t [27] = 2.85, p = .008) and was no longer significantly different from the comparison group on any of the four dimensions of decisional capacity on the MacCART-CR scale (p = .13–.33). Follow-up analyses also showed a significant effect of the intervention on a sub-set of the schizophrenia group who had performed most poorly at baseline, from a baseline mean of 18.0 (SD = 4.7) to 20.6 (SD = 4.9; t [7] = 2.59, p = .029). The effect size for this change is moderate in size (Cohen’s d = 0.6). Participants with schizophrenia earned significantly lower scores than those in the comparison group across multiple neuropsychological domains. Challenge: unable to determine what aspect of the intervention used was most helpful (active ingredients), as all participants in the schizophrenia group received both the standardised computer presentation and the individualised corrective feedback components. Had healthy comparisons, not other schizophrenia patients. Solutions: those individuals who initially lacked decisional capacity may benefit significantly from enhanced consent procedures. Further research is needed to unpick which components of the intervention are those causing the improvements. |

| Jeste et al. [92], USA, A3 | 2009 | RCT to evaluate the effectiveness of a multimedia versus routine consent procedure (augmented with a 10-min control video presentation) to enhance understanding among adults with schizophrenia and healthy comparison subjects. | Outpatient clinics of an older mental health service | Mental health: older patients with schizophrenia |

Enhanced informed consent: multimedia consent; the research assistant (RA) provided participants with the printed consent form. Subjects watched a DVD that explained the protocol. Multiple representation and contiguity principles were present throughout the DVD by presenting consent-relevant information through a narrator explaining key points, with simultaneous visual presentation using graphics, pictures, animations, and summary text (bullet-pointed). Subjects were encouraged to ask the RA to stop the DVD and repeat any segments that were unclear. Participants were encouraged to discuss and clarify issues with the RAs. Such discussion is important for multimedia consent aids to aid person-to-person interaction not to substitute. Adults with impaired capacity |

128 middle-aged and older persons with schizophrenia and 60 healthy comparison subjects |

Key findings: outpatients with schizophrenia provided with a multimedia-aided consent procedure demonstrated better comprehension of a research protocol and were more likely to be categorised as being capable of consent under three different standards examined, compared with those presented with an enhanced routine consent procedure. MacCAT-CR understanding subscale for outpatients with schizophrenia trial 1 (d = 0.6384, p = 0.0055, 95% CI 0.54, 0.74), trial 2 (d = 0.6108, p = 0.0237, 95% CI 0.52, 0.71), trial 3 (d = 0.6117, p = 0.0169, 95% CI 0.52, 0.70), UBACC total (d = 0.6795, p = 0.0003, 95% CI 0.59, 0.77). There were few differences between the two (routine and multimedia) consent conditions among the healthy controls. Challenge: comprehension can be improved with simple procedures such as corrective feedback/iterative learning. Hence, considering the additional resources, whether a full-multimedia presentation is needed is questionable. Solutions: multimedia consent procedures may be a valuable consent aid that should be considered for use when enrolling participants at risk for impaired decisional capacity, particularly for complex and/or high-risk research protocols. |

| Harmell et al. [91], USA, A3 | 2012 | RCT to evaluate the preliminary feasibility and potential effectiveness of a web-media approach to consent, i.e. to determine whether development of such web-media based tools warrants further pursuit. | Unclear | Mental health: patients with schizophrenia |

Enhanced informed consent: participants allocated to web-media consent reviewed the study information on a web-media prototype, which involved video clips, static images/graphics, and bullet-pointed text to explain the consent form. The printed consent form was presented on the screen in sections covering: e.g. study introduction, a timeline with study visits, description of procedures, risks/discomforts, possible benefits, action if injured, and voluntary participation. The tool included questions with corrective feedback after each section to check understanding. Participants could ask questions at any point and replay the presentation. Adults with impaired capacity |

19 patients with schizophrenia and 16 normal comparison |

Key findings: relative to those receiving the routine consent procedure, those receiving the web-media consent evidenced better UCSD Brief Assessment of Capacity to Consent (UBACC) scores, U = 19, z = − 2.15, p = 0.03 (d = 0.94; ‘large’ effect size). Participants rated the quality of the enhanced consent procedure as ‘better’, and no participant reported worse experience. Challenge: increased length of administration and that computer-based approaches may intimidate people with less computer literacy. Solutions: incorporating audio-visual materials on a computer/web platform to enable a more interactive and flexible presentation is feasible and more acceptable than presentation on a DVD. Such presentation may enable researchers to capitalise on the benefits of audio-visual learning, while circumventing the limitations of a DVD presentation. |

| Sudore et al. [82], USA, B3 | 2006 | Observational nested in a trial of two advance directives to describe a modified research consent process, and determine whether literacy and demographic characteristics are associated with understanding consent information. | Hospital | Geriatric care/older patients: ethnically diverse subjects, aged ≥ 50, consenting for a trial to improve the forms used for advance directives | Enhanced informed consent: a modified consent process—consent form (written at a sixth grade level) read to participants, combined with 7 comprehension questions and targeted education, repeated until comprehension achieved (teach-to-goal). | 329 potential participants. Twenty participants refused to participate, 39 excluded due to scheduling issues, 61 did not meet the eligibility criteria, and data were missing for 1 participant, leaving 208 participants. 208/329 (63.2%) |

Key findings: despite significant consent modifications (improving readability of the consent form, having bilingual research assistants read the consent form to participants, and allowing time for discussion), few participants (28%) had complete comprehension and required only 1 pass through the consent process. However, further use of a teach-to-goal strategy was successful in achieving complete comprehension in 98% of all participants who engaged in the consent process, including those with literacy or language barriers. Challenge: the comprehension statements could have addressed all of the required elements of informed consent, making our results more generalisable. Solutions: for the majority of these participants, little additional education was required. |

| Rikkert et al. [81], Netherlands, C1 | 1997 | Pre- and post-test study of a step-wise consent process to determine the effects of research experience on the capacity to consent. | Hospital | Geriatric care: geriatric patients |

Step-wise consent: (1) Eligibility screening. (2) Research experience was given by a try-out period of a week. Verbal and written information about the try-out was given to all eligible subjects (n = 78). For 40% of potential subjects, the family members were willing to accompany them when they received information. 70 subjects (90%) provided verbal consent to participate in the try-out. (3) After the try-out, written informed consent was requested. The verbal information was repeated. Assessment of the capacity to consent was conducted before and after experiencing research by testing comprehension and ability to weigh risks and inconveniences. Adults with impaired capacity |

53/78 (68%) |

Key findings: the try-out effect on the comprehension scores could be tested in 53 subjects who provided written informed consent. Initially, the subjects answered only 5.0 of the ten questions correctly, this number increased to 7.0 after the try-out. This step-wise consent procedure resulted in a participation rate of 68% (53/78) of all eligible subjects. During the try-out, seven subjects withdrew consent. Ten subjects refused informed consent to continue research following the try-out. Solutions: research experience seems to improve the capacity to consent in demented and depressed subjects as well as in subjects without psychogeriatric illnesses. |

| Processes to enable adults lacking capacity to participate in research | |||||||

| Advance and process consent | |||||||

| Olazaran et al. [64], Spain, C1 | 2012 | Research protocol to provide an overview of the clinical research protocol of the ACRSF (Alzheimer Center Reina Sofia Foundation), to analyse the adequacy of the assessment instruments, and to report on changes to the protocol. | ACRSF research centre | Dementia: patients with Alzheimer’s or other dementia and their relatives who agreed to receive treatment from the ACRSF (MMSE 6.7 (6.1)—nursing home to 9.1 (7.6)—day-care centre) |

Advance consent upon arrival to the facility; legal representative to provide informed consent: upon admission, one or two ACRSF research physicians introduced the patient and family caregivers to the ACRSF research programme and invited the legal representative to sign consent to participate. The consent form included separate boxes for agreement to specifically participate in the clinical, biochemical, genetic, MRI, and neuropathological programmes. Adults with impaired or diminished capacity |

180 (80% of the total) |

Informed consent was obtained from 180 patients. Those patients represented approximately 80% of all patients admitted at the ACRSF during that period. Demographics: the two groups of patients studied were old (outpatients) or very old (inpatients), had very low educational achievement, and were predominantly women. Solutions: multidisciplinary action. |

| Gysels et al. [45], UK, C1 | 2013 | Consultation workshop and TEC to present the processes and outcomes of a workshop and consensus exercise on agreed best practice to accommodate ethical issues in research on palliative care. | N/A | Palliative care |

Advance consent, process consent Adults with impaired or diminished capacity |

28 |

Key findings: 16 recommendations generated. The recommendations on obtaining and maintaining consent from patients and families were the most contentious. Challenge: fluctuating capacity, time, risks involved in participating. Solutions: informing all the patients/relatives on admission that the facility conducts research, minimises gatekeeping, and identifies people interested in research participation. The level of detail on the information sheets should be proportional to burden and risks. Advance consent (early informed consent when the patient still has capacity) for all research, not just CTIMPs. Contemporaneous assent should also be obtained for all trials. Consent should be a continuous process. Consent process < 24 h after approach with clear justification to avoid coercion. |

| Cowdell et al. [70], UK, B3 | 2008 | Ethnographic study exploring strategies that were used to enable older people with dementia to become actively engaged in research with them. | Hospital | Dementia: inpatients ≥ 65, with a dementia diagnosis at an advanced stage of the illness | Process consent: verbal or behavioural consent was taken from participants at the beginning of every period of observation to ensure they were willing to continue. This consent was negotiated between the person with dementia, the researcher, the staff on duty, and on occasion the next of kin. Participants were observed for any signs that they might wish to withdraw. For the interview part of the study, participants were asked to sign a consent form. | 125 h of observations and interviews (n unclear) in an inpatient setting |

Key findings: actively engaging older people with dementia even at advanced stages (e.g. instead of having a pre-defined MMSE cut-off) in research is possible. Researchers need to apply ethical principles and rules sensitively and flexibly. Challenge: ensuring the informed nature of the consent, without having a formal capacity assessment. |

| Dunning et al. [46], Australia, B3 | 2012 | Individual semi-structured interviews, field notes, philosophical framework to discuss the ethical and methodological issues encountered when undertaking research to develop guidelines for managing diabetes at the EoL. | Participants’ homes | Palliative care: semi-structured interviews with 14 men and women with diabetes and 10 spouses of the 14 participants |

Process consent: involved asking participants whether they wanted to continue the conversation during the interview. Process consent was used when a participant became physically or emotionally distressed (in addition to informed consent). Adults with impaired capacity |

Not known |

Key findings: qualitative research deemed to be the most effective data collection method. Solutions: attention to protecting participants’ privacy, ensuring they can give informed consent, being aware of their physical and mental state, and periodically checking their willingness to continue participating during interviews and focus groups, is essential. |

| Hughes et al. [65], UK, C1 | 2015 | Qualitative consultation aiming to develop an approach within the guidance of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) to meaningfully include people diagnosed with dementia in research endeavours. | Integrated dementia day care services | Dementia: people with a dementia diagnosis residing at residential care homes |

Process consent Adults with impaired capacity |

8/9 (one declined to participate due to unexpected housing issues) |

Consent process: first consent of participating service leads to allow identification of eligible patients. Then, the tested consent process was implemented, and patients’ consent was assessed and recorded. Consent reliability—not having a one-off consent and renewing consent at every encounter. Challenge: participants lost track of the purpose of the research. Important to attend to non-verbal cues. Gatekeeping from relatives and switch of decision-maker from patient to relative based on the context of the decision. Solutions: researchers should be trained in reflexive assessment of consent using verbal and behavioural cues. Initial approach to participate could be by a trained service user consultant to balance the power dynamics. Researchers should involve all parties not limit to, for example, family caregiver. |

| Carey et al. [95], Ireland, B3 | 2017 | Qualitative study to explore theoretical underpinnings of intellectual disability research, and to discuss the ethical and methodological considerations in recruiting and obtaining informed consent from adults with intellectual disabilities. | Intellectual disability service/participants’ preferred place and time | Mental health: adults with intellectual disability |

Process consent Adults with impaired capacity |

12/14 |

Consent process: ongoing informed consent—detail information session, option to have a support person present. Written consent. Six participants also wanted their consent to be recorded. Non-verbal cues were considered while assessing ongoing consent. Solution: the structure of these meetings facilitated discussions about the nature of the study. Key findings: making reasonable accommodations to support decision-making, making space for the development of empathic relationships with both the potential participants and with the structures and service supports. |

| Deferred consent | |||||||

| Adamis et al. [100], UK, B3 | 2010 | Prospective cohort to assess serum IGF-I in patients with delirium and the way in which results altered when including patients with delirium who lacked capacity. | Elderly care unit | Delirium: patients 70 years or more with the presence of delirium using Confusion Assessment Method–Fluctuating capacity |

Deferred consent: those who lacked capacity were entered (deferred) to study and their capacity were re-assessed to see if they gained capacity or proxy assent was obtained. Adults with diminished capacity |

164/233 (70%). 13/23 recruited lacked capacity and 151/210 recruited with capacity. |

Key findings: the inclusion of the more incapacitated subjects allowed a significant finding (lower serum IGF-I in prevalent delirium cases). Strengthened the evidence that IGF-I has a role to play in the pathophysiology of delirium. Solution: informal approach to capacity may allow for more representative results of the study population. |

| Honarmand et al. [104], Canada, B3 | 2018 | Prospective, pilot study to describe the feasibility of the deferred consent model in a low-risk, observational study of critically ill patients (Prognostic Value of Elevated Troponins in Critical Illness Study [PRO-TROPICS]) and to determine the factors associated with consent procurement. | Intensive care units at three study sites across Canada | Intensive care: critically ill patients |

Deferred consent: patients are enrolled to the study and then themselves or their surrogate decision-maker is approached for consent. Consent can be provided to ongoing study participation, use of data collected so far, or no consent for data to be used. Adults with diminished capacity |

214/267 (80%) |

Key findings: deferred consent model was feasible with 80% consent rate. Of 53 persons declining consent, 37 (70%) agreed to the use of the data collected to that point. One patient withdrew consent after it was provided by a proxy decision-maker. But, patients unlikely to recover were excluded. Consent rate did not differ based on who (patient/surrogate) was consenting. Challenge: exclusion of patients who might not recover/die and exclusion of patients who die early or cannot provide consent within the study timeframe lead to selection bias, reduced statistical power, and decreased external validity. |

| Consultee advice | |||||||

| Black et al. [60], USA, C1 | 2007 | Methodological paper focusing on three aspects of the consent process for dementia research: (1) providing information, (2) assessing understanding and capacity to consent, and (3) obtaining assent and informed consent. For each aspect, the differences between drug and non-drug studies in CDRS examined. | Six parent dementia studies | Dementia | Informed consent and/or personal consultee advice (dual consent) | Researchers (n = 11), patients, and their personal consultees from six dementia studies—46 consent process observations |

Key findings: study revealed wide variability in how informed consent was obtained. (1) Consents forms were provided to the patients and personal consultees prior to enrolment visits and often served as a guide for consent discussions; (2) consent discussions were more consistent and comprehensive for drug studies than non-drug studies; (3) study procedure explanations dominated the discussions, whereas the rights of research subjects were mentioned less frequently; (4) assessments of affected individuals’ understanding and capacity to consent occurred in a minority of cases but were more likely to occur on drug studies; (5) personal consultee advice was sought more often using an implicit rather than an explicit approach; (6) dual consent by both the affected individual and surrogate decision-maker was most common on both drug and non-drug studies; (7) personal consultees often played a major role in facilitating the consent process. Solutions: describing the purpose of the study; discuss the individual’s rights in detail; involving the personal consultees; explicitly ask the potential participants for their involvement; use a standardised way of assessing capacity; explain why a personal consultee advice is needed. |

| Agarwal et al. [69], UK, C1 | 1996 | Observational study examining the relevance of the Law Commission recommendations in accessing informed consent from early dementia patients and their carers subjected to a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of a potentially therapeutic agent. | Unclear | Dementia: patients and carers |

Personal consultee advice: two questionnaires (for patients and their carers) were designed to examine whether subjects fulfilled the criteria for a ‘cognitive’ or ‘function’ test of capacity to consent to participate in a research study. This was an attempt to establish whether consent was a ‘true choice’. Adults with impaired capacity |

15 patients and carers |

Key findings: a single legal ‘test’, with stringent criteria, applied across the board for all treatment and research conditions, may impede future research activity as none of the subjects fulfilled the criteria for determining whether participation was a true choice. Challenge: implied consent (opt-out) could lead to exploitation of vulnerable patients. Solutions: the role and involvement of carers in the decision-making process need to be considered. Provided that they are acting in the patient’s best interests, that the patient has not actively expressed a desire not to participate, and that the research is potentially therapeutic, with the research drug having negligible side effects, this is unlikely to violate his fundamental rights. |

| Gainotti et al. [68], Italy, A3 (methods paper reporting RCT [79]) | 2010 | Methodological paper hypothesising that the requirement that informed consent for an incapacitated subject’s participation to research be given by a legal representative appointed by the courts slows down the recruitment process in research thus complicating the conduction of dementia research in Italy. | Outpatient clinic | Dementia: outpatients seeking medical advice for cognitive complaints |

Legally appointed consultee advice: the procedure to obtain informed consent in the study was quite elaborated. First, subject’s competence was evaluated by means of the MMSE. If the subject’s score was ≥ 20, then he/she underwent four additional neuropsychological tests. If the subject’s score to the four tests was higher than the established cut-offs, the subject was deemed able to give informed consent. If the subject’s MMSE score was < 20, adjusted for age and education, or if the subject’s score to the other four tests was lower than the established cut-offs, the subject was deemed unable to give informed consent and consent had to be given by a legally authorised representative. Adults with impaired capacity |

78/172 (46.2%) required legal consultee appointment, 55/78 (70.5%) received appointment |

Key findings: the requirement that the legal representative be appointed by the courts may impede a subject’s participation in research. It may cause embarrassment and conflicts among family members, it may have been received as a bureaucratic and burdensome task, and relatives may be reluctant to go to court due to stigma. This results in only a privileged selection of patients being involved in the studies. Solutions: Removal of legal procedure for the involvement of consultees or fastening the legal processes and reducing burden. |

| Adamis et al. [99], UK, A3 | 2005 | RCT to investigate whether different methods of obtaining informed consent affected recruitment to a study of delirium in older, medically ill hospital inpatients. | Acute medical service for older people at a hospital | Delirium: patients 70 years or older admitted to the unit within 3 days of hospital admission | Informed consent or proxy assent: both groups of patients were given routine same information (verbally and written). After a formal capacity assessment, assent was sought from a proxy (if available) if patient lacked capacity in group A, whereas in group B, an informal capacity assessment took place and those individuals who deemed to lack capacity were excluded. | 57 assessed in group A (43.8%), 25/57 (43.9%) entered the study. 73 assessed in group B (56.2%), 54/73 (74%) entered the study. 20 patients in each group were recorded as ‘case note delirium’. |

Key findings: implementing best ethical practice by a formal assessment of capacity to consent to a research project in an acute medical ward will lead to a considerable reduction in the proportion entering the study. A stringent assessment of capacity may lead to reduced generalisability of the study findings. In turn, this undermines the ethical justification of the study. Of the 20 patients in each of the initial randomised groups (A and B) with case note delirium, 7 (35%) in group A and 16 (80%) in group B (p = 0.004) entered the study (χ2 = 8.29, df = 1; p = 0.004). Challenge: researcher assessing the capacity was not blinded to group allocation. Many potential participants with delirium do not have formal capacity to consent. In this study, including almost all prospective patients admitted to an elderly care unit, 40% lacked capacity to give consent to this research when judged formally. The process of formal testing of capacity might have resulted in bias by inducing higher rates of declining to give consent. Solutions: the consent rate may be greater if a step-wise approach to consent during participation is used. In this approach, called ‘experienced consent’, verbal consent is accepted initially, and after the subject has experienced the project, written consent is sought. |

| Morán-Sánchez et al. [90], Spain, C1 | 2016 | Cross-sectional survey to evaluate the association between capacity to consent to research and the more prevalent psychiatric disorders, and to characterise factors associated with impairments in capacity across diagnostic groups. | Mental health care | Mental health: psychiatric patients |

Informed consent and legal guardian consent: capacity was assessed using MMSE and MacCAT-CR. Adults with impaired capacity |

139/235 (59%) |

Consent process: informed consent patients with capacity or from legal guardian if lacked capacity. Capacity: the level of understanding needed to provide meaningful consent to participate in this minimal-risk protocol was much lower than that required for a complex or higher-risk clinical trial, such as that described in the hypothetical protocol used to evaluate capacity in the study. MacCAT-CR used to assess capacity. Key findings: no subject was excluded because of a lack of capacity. 31% of the participants lacked decisional capacity to provide informed consent. Those lacking capacity were more likely to be older, with severe illness over a longer time. The number of psychiatric admissions was higher in the incapacitated group. They were more likely to have a psychotic or mood disorder and to score lower on the MMSE. Solutions: cognition must be considered in capacity assessment. Understanding can be improved through enhanced consent procedures. |

| Thomalla et al. [87], Germany, A3 | 2017 | RCT (baseline data only). Aim to determine if the manner of consent, i.e. informed consent by the participant or by proxy decision-maker, affected clinical characteristics of samples of acute stroke patients enrolled in clinical trials. | Hospital | Stroke: stroke patients |

Informed consent (written or oral) by patient, personal or legal proxy, consensus between the investigator and an independent clinician: six options give including written or oral consent by the patient, legal guardian consent, NoK consent, investigator’s decision (followed with consent from NoK as soon as possible). Adults with diminished capacity |

1005/1039 (ongoing trial) |

Key findings: in 646 (64%) patients, informed consent was given by the patients; in 359 (36%), consent was by a proxy. The relative frequency of the informed consent type used varied among countries (p < 0.001). In this analysis of baseline data of the first 1005 patients enrolled in the WAKE-UP trial, about 1 in 3 patients were enrolled by proxy consent. In these cases, consent was provided by the legal guardian, by next of kin, by an independent consultant, or by the investigator based on an emergency clause. Challenge: limited guidance around regulation of clinical research in patients lacking capacity to give informed consent, and the consequence of different approaches for informed consent used in different stroke trials, among countries or trial sites. |

| Kim et al. [66], USA, C1 | 2011a | To assess the extent to which persons with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) retain their capacity to appoint a research proxy. | Interview study | Dementia: people with Alzheimer’s disease (MMSE 18–23) |

Proxy consent Adults with diminished or impaired capacity |

700 |

Key findings: successful recruitment had the highest proportion (46.3%) of participants with MMSE score range of 18–23. Reliability of the judges’ determination of capacity was high. 61.7% of participants had the capacity to appoint a research proxy, 41.4% had capacity to consent to the drug RCT, and 15.6% had the capacity to consent to the neurosurgical RCT. A substantial proportion of AD subjects thought incapable of consenting to lower or to higher risk studies had capacity to appoint a research proxy. Solutions: providing for an appointed proxy even after the onset of AD may help address key ethical challenges to AD research. Appointing a proxy is advocated early in the disease trajectory. |

| Warren et al. [47], USA, C1 | 1986 | Qualitative interviews to examine the bases on which the proxies made their decision, to identify characteristics that distinguished proxies who refused consent from those who gave consent, and to determine reasons for refusal. | Nursing home | Palliative care: nursing home residents’ (those who were > 65 years old) proxies |

Proxy/surrogate consent Adults with diminished capacity |

90/168 (54%) |

Key findings: 54% (n = 90) of proxies approached consented to patients’ participation. 60% of proxies consulted other people about their decision; 27% consulted a clinician about advising participation (or not). No significant difference in the frequency of consent among those who decided alone, those who consulted others, and those who consulted a clinician. Most proxies were not opposed to research in general, but as beliefs and perceptions about research became more relevant to their own family members, their support for research, even in the abstract, declined. 96% thought research in general was important for medical care; 87% agreed for research to be undertaken in hospital; 83% thought that elderly people should participate in research; only 66% thought that research should be conducted in nursing homes. Solutions: broad educational effort to increase awareness of the relevance of research to the health of older people across care settings. To discuss participation in research with patients while they are competent and to include potential proxies in these early discussions. |

| Karlawish et al. [67], USA, C1 | 2008 | Companion study to an RCT placebo controlled of a potential Alzheimer’s disease treatment (drug) study to examine the views of Alzheimer’s disease patients and their study partners on the ethics of proxy consent for clinical research. | Universities | Dementia: patients with mild-to-moderate AD (MMSE 12 to 16), and their study partners (spouse or adult child) |

Proxy consent Adults with diminished capacity |

59/73 (81%) patients, 60/75 (80%) study partners |

Key findings: study partners of patients judged incapable of giving informed consent reported the same degree of patient involvement in the decision to enrol as the study partners of patients capable of giving informed consent. Most study partners and patients supported proxy consent for the clinical trial, and nearly all patients chose their study partner and their proxy. Study partners generally made research enrolment aligned with maximising the patient’s well-being. Solution: pursue a process of shared decision-making between patient and study partner to recruit patients with impaired capacity. |

| Smith et al. [107], Canada, C1 | 2013 | Qualitative study with interactive focus groups to present strategies that may optimise the process of obtaining informed consent from substitute decision-makers for participation of critically ill patients in trials. | Intensive care unit | Intensive care: research coordinators working with critically ill patients |

Surrogate consent: informed consent from substitute decision-makers of critically ill patients Adults with diminished capacity |

71 | Key findings/solutions: (1) brand the trial with key messages, (2) train the local personnel, (3) promote a culture of research, (4) be familiar with patient family dynamics, (5) involve bedside staff—make them aware that you are interested in recruiting their patient, (6) introduce the idea of research in a professional manner—explain why you are approaching the surrogate decision-maker, (7) present the facts about the research problem and outcomes, (8) convey risks and benefits transparently, (9) describe alternatives to participation and support the consent decision, (10) explain all research-related activities, (11) Document the consent process, (12) provide thanks and ongoing study updates to all stakeholders, and (13) follow-up with the patient to ensure ongoing consent. Strategies reinforce requirements outlined in existing legislations and additional process to enhance the integrity of the consent process. |

| Bolcic-Jankovic et al. [105], USA, C1 | 2014 | Cross-sectional quantitative survey on (a) the determinants of confidence in a surrogate’s ability to make a decision for the patient, (b) the difference between surrogates’ and patients’ confidence, (c) if greater confidence increases agreement between the surrogate’s and patient’s response. | Intensive care unit | Intensive care: patients who required ICU and who had potential to regain capacity after recovery, and surrogate decision-makers. |

Surrogate consent Adults with diminished capacity |

445 surrogates, 214 patients |

Consent process: surrogate consent obtained during the patient’s ICU admission. Key findings: the research funder, knowledge about the study, and discussing with a trusted person were associated with surrogates’ confidence in advocating participation and attitudes towards research. Patients’ confidence in their surrogates’ decision was associated with a previous discussion about research participation (p < .001). Confident surrogates responded in agreement with patients’ wishes (80%). Most surrogates wanted to represent the person’s wishes. Solution: Early discussions between the proxy and patient about research participation. |

| Fowell et al. [48], UK, A3 | 2006 | Randomised crossover trial to explore the feasibility of two designs of consent for dying patients: randomised consent (aka Zelen’s design) and cluster consent to see which design is more effective for trials in palliative care. | One oncology and one palliative care unit | Palliative care/cancer: patients with a terminal cancer diagnosis who were on an integrated care pathway for the dying |

Cluster consent: consent at unit level for a group from a ‘cluster guardian’, and ‘cluster gatekeeper’ responsible for individual patient approach. Both guardian and gatekeeper must give written agreement for their cluster to participate in the trial. Randomised consent (Zelen’s design): seeks informed consent after randomisation but only if the patient is to receive the experimental treatment. Adults with declining, impaired, or diminished capacity |

20/50 (60%) |

Key findings: the initial request to abstract data was identical in both designs and significantly fewer Zelen patients in the larger unit consented to this. Zelen’s design reduces the burden of seeking consent for treatment allocation but did not improve recruitment. Solutions: cluster randomisation runs in the background, reducing burden on the patient, carer, and clinician. Consent to treatment allocation is at the unit level with individual patient consent for access to confidential medical data. This study illustrates how cluster randomisation exploits these natural advantages, particularly with dying patients. |

| Levine et al. [106], USA, C1 | 2017 | Expert consultation—electronic survey followed with Delphi rounds aiming to establish a broader consensus on the barriers to emergency care research globally and proposes a comprehensive array of new recommendations to overcome these barriers. | Global emergency medicine covering | Intensive care/emergency medicine: experts in global emergency medicine |

Community consent Adults with diminished capacity |

80 |

Solutions/suggestions: streamline data collection, identifying alternatives to local IRB approval and the use of community consent when appropriate where the individuals can choose to opt-out of the study later on. Key findings were divided into four categories. (1) Limited availability of research training. (2) Logistical issues and lack of data collection standardisation. (3) Ethical barriers regarding conducting research in low-income countries. (4) Dearth of funding for global emergency research. Key findings: need for ethical curriculums including important topics related to the ethics of acute care research internationally such as consent, loss to follow-up, coercion, and undue influence for enrolment was highlighted. |

| Boxall et al. [88], UK, B3 | 2016 | Qualitative focus groups and interviews exploring the barriers to recruiting stroke patients to clinical trials from the viewpoint of experienced nurse researchers. Secondary aims included exploring the factors affecting the recruitment of stroke patients, explore the main themes that influence recruitment, and determine if stroke research faces unique recruitment issues. | Hospitals | Stroke: stroke research nurses |

Surrogate consent, paramedic/early-on-scene consent, exception/delayed consent Adults with diminished capacity |

12 |

Challenges: restrictive inclusion/exclusion criteria, physician endorsement, and lack of clinical equipoise. Impairments affecting capacity to consent—lack of validated tools to help assess capacity. Acute time frame to recruit, paternalism of (especially less-experienced) nurse researchers. Solutions: engaging caregivers and, if possible, using surrogate consent. Finding a balance between giving patients the opportunity yet not coercing them. Consent process (suggestions): ■ Traditional, in-hospital consent with a clinician and written information. ■ Paramedics/early on-scene consent. ■ Exception or delayed consent. ■ Surrogate (relative, legal representative, or independent physician) consent. ■ Short or abbreviated written information. ■ Use of pictorial information sheets or videos to explain a study ■ Telephone or video consent. |

Quality appraisal

Overall, the quality of the included articles was medium to high. Most quantitative (95.8%, n = 71) and qualitative studies (88.9%, n = 17) were assessed as medium or high quality (see Additional file 2: Table S5 quantitative studies and Table S6 qualitative studies). The proportion of high-quality studies included was consistent across the three main areas (56.8% ‘innovating research methods’, 56.6% ‘applying consent processes’, and 59.1% ‘public attitudes’). However, in the area of ‘public attitudes on involving adults lacking capacity’, 9% were assessed as low quality, compared with 0% in ‘innovating research methods’ and 2% in ‘applying consent processes’. This reflected in part the methodological nature of the studies and poorer fit with the Qualsyst item criteria. The included studies were mainly descriptive (n = 36) categorised as ‘non-experimental, longitudinal, cohort, matched pairs, or cross-sectional, sound qualitative, or analytical studies’, with few experimental (n = 20) or quasi-experimental designs (n = 3) (see Additional file 3: Table S7).

Innovating research methods to recruit adults across the capacity spectrum

Thirty-seven studies were categorised as innovating research methods (Table 3). Studies focused on participation in research involving individuals with cancer/receiving palliative care (n = 6), dementia (n = 13), geriatric care (all settings) (n = 2), delirium and mental health services (n = 7), or intensive care (n = 5). While numerous studies used standardised capacity assessment tools, existing tools were often regarded as time-consuming, and administration of a formal capacity assessment reduced recruitment, for example in an observational study involving patients with delirium [99]. Formal capacity assessment was considered of little value unless aligned to the decisional requirements for study participation, notably the risks and the potential direct or indirect benefits of participation. Overall, studies incorporated multiple components of the processes of consent. These were tailored to individuals’ level of capacity from mild to moderate impairment with a focus on enhancing informed consent, through to lacking capacity requiring involvement of a consultee. For example, in populations such as psychiatric or stroke patients, where participants experienced varying levels of impaired capacity, studies incorporated processes of enhanced informed consent and consultee involvement [87, 90]. In both studies, consultee advice was sought for a third of participants (30.6% and 35.7%, respectively). The innovations broadly mapped onto two sub-categories of ‘maximise individuals’ autonomy and decisional capacity in the consent process’ and ‘processes of consent to enable adults across the capacity spectrum to participate in research’.

Maximise individuals’ autonomy and decisional capacity in the consent process