The current pathologic criteria for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (iPD) require both neuronal loss in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) and alpha-synuclein–containing Lewy bodies (LBs)[1-3]. These strict criteria highlight the importance of synuclein in the pathophysiology of PD; however, autopsies of genetic forms of PD and specifically LRRK2 PD may challenge these criteria. Here, we present a case of a LRRK2 G2019S PD patient without Lewy body pathology.

The patient was of Ashkenazi Jewish descent and had a family history significant for a father with PD and a paternal aunt with parkinsonism. His first symptoms arose at the age of 68, with decreased left arm swing, intermittent left hand rest tremor and reduced walking speed. At 71 he saw a movement disorders neurologist who also noted gait asymmetry, mild to moderate increased tone in all extremities and impairment of finger and leg agility. All were more prominent on the left side. He was diagnosed with PD and improved with selegiline (5mg bid). Eight years after symptom onset, at the age of 76, the patient had his first fall while walking on uneven terrain. The following year, at the age of 77, he was started on carbidopa-levodopa (total daily levodopa dose of 250mg). Dyskinesia of his head presented for the first time at the age of 85. His first episode of freezing of gait was at 86, 18 years after symptom onset. His total daily levodopa dose had increased to 600mg. At this time, he enrolled in genotype-phenotype studies after signing informed consent. The protocols were approved by Columbia University IRB (AAAE0748 and AAAF3108). Among the assessments done, neuropsychological testing was performed annually between ages 87 and 91. Assessments indicated non-amnestic Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) at baseline, characterized by average encoding, low average delayed recall on memory testing, low average semantic fluency in the context of average phonemic fluency, average visuospatial performance, and severely impaired set-shifting, suggesting significant executive dysfunction. His neuropsychological performance progressed to consistent with dementia over the four years, with scores declining across domains. Specifically, he demonstrated severely impaired delayed recall, semantic fluency, visuospatial functioning, and set-shifting. Smell testing was measured using the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), which demonstrated severe hyposmia for his age (raw score range: 22/40-24/40). The available Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part II and III scores are presented in Table 1. He was found to carry the LRRK2 G2019S mutation. He was fully sequenced for GBA mutations but was not a carrier. At the age of 88, he experienced a marked decline in balance and walking, which resulted in two significant falls and required the use of a walker. The patient also reported having intermittent hallucinations and confusion, presumably due to diphenhydramine in an attempt to help alleviate excessive salivation. He required the use of an aide at the age of 90 due to difficulties with ambulation. The patient died 23 years after symptom onset at the age of 91.

Table 1:

Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) Part II and III Scores From Ages 86-91

| Age (years) | 86 | 86 | 87 | 87 | 88 | 88 | 89 | 90 | 90 | 91 | 91 |

| Part II | 14 | 18 | 16 | 16 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 24 | 27 | 25 |

| Part III “ON” | 37 | 43 | 39 | 35 | 32 | 32 | 44 | 38 | 38 | 38 | 43 |

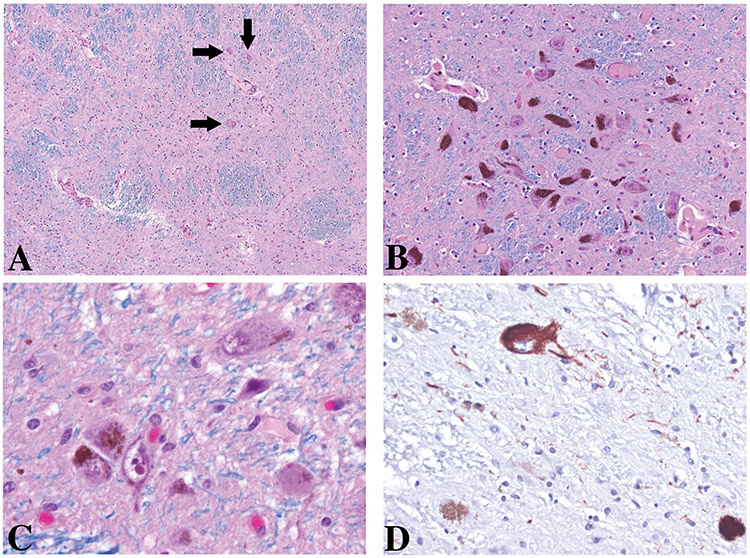

On autopsy, the brain was grossly found to have mild to moderate atrophy, predominantly in the fronto-temporal areas with moderate widening of the lateral ventricles. There was mild arteriolosclerosis with up to 40% luminal stenosis. In addition, scattered, patent leptomeningeal and cortical vessels contained moderate amounts of β-amyloid-labeled deposits in the media. There was severe loss of pigmented neurons in the SNpc (see Figure).

FIGURE: Substantia Nigra.

Uneven loss of pigmented neurons: subtotal loss within the lateral third at the level of the decussation of the superior cerebellar peduncle of the pars compacta (A), rare residual neurons are present (arrows). Relative spared areas within the intermediate third (B) and lateral third (C and D) of the pars compacta at the level of the red nucleus. Among the residual pigmented neurons a few are labeled with AT8 antibodies (D). No Lewy body-containing neurons are present throughout the sections.

A, B, and C: Luxol-Hematoxylin and Eosin; D, tau antibodies (AT8) Original magnification 100X, 200X, 630X, and 400X.

Microscopically, only two LBs were identified; a single one within the temporal claustrum and one within the cingulate cortex, which were without Lewy neurites (to detect alpha synuclein we used NCL-L-ASYN (1:40) antibodies from Leica). The uneven loss of pigmented neurons was severe rostrally, but mild caudally. In contrast to idiopathic PD autopsies [1], the locus coeruleus (LC) was normal with no Lewy bodies, as were the dorsal nucleus of the vagus, reticular formation, mesencephalon including the pars compacta of the SN, hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampal formation, thalamus, basal forebrain, or the olfactory bulb. Among the pigmented neurons of the SNpc, few were positive for AT8 antibodies (which recognizes phosphorylated tau protein), as were rare threads. Similar mild tauopathic changes were found within the fourth cranial nerve nucleus (but none in the third), raphe, subthalamic nucleus, and within the neostriatum. The paleostriatum showed rare AT8 labeled neuropil threads; however, no AT8-labeled neurons were found. Alzheimer’s disease changes were minimal and focal, and thus considered to be consistent with usual ageing. Indeed, neocortical neuritic plaques were rare, argyrophilic neuronal tangles were absent and AT8-labeled neurons and threads were confined to parahippocampal gyrus, and the occipitotemporal gyrus.

In summary, the case presented highlights that synuclein burden is not necessary for a clinical syndrome of PD that meets Movement Disorder Society (MDS) clinical criteria [4]. He had both motor (rest tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and gait impairment) and non-motor (impaired sense of smell and cognition; possibly hallucinations) symptoms without LB. While likely representing a small minority of PD cases, this and other LRRK2 cases with SN atrophy and parkinsonism, challenge the concept that synuclein pathology is necessary for PD diagnosis.

ACKNOLWEDGEMENT

Research data was available on this participant through the AJ-LRRK2 Study, which was funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation (Marder, PI). The autopsy was funded by the Parkinson’s Foundation.

REFERENCES

- [1].Dickson DW, Braak H, Duda JE, Duyckaerts C, Gasser T, Halliday GM, Hardy J, Leverenz JB, Del Tredici K, Wszolek ZK, Litvan I, Neuropathological assessment of Parkinson's disease: refining the diagnostic criteria, Lancet Neurol 8(12) (2009) 1150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Daniel SE, Lees AJ, Parkinson's Disease Society Brain Bank, London: overview and research, J Neural Transm Suppl 39 (1993) 165–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S, Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease, Archives of neurology 56(1) (1999) 33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, Poewe W, Olanow CW, Oertel W, Obeso J, Marek K, Litvan I, Lang AE, Halliday G, Goetz CG, Gasser T, Dubois B, Chan P, Bloem BR, Adler CH, Deuschl G, MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson's disease, Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 30(12) (2015) 1591–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]