Abstract

Paranemic crossover DNA (PX-DNA) is a four-stranded multicross-over structure that has been implicated in recombination-independent recognition of homology. Although existing evidence has suggested that PX is the DNA motif in homologous pairing (HP), this conclusion remains ambiguous. Further investigation is needed but will require development of new tools. Here, we report characterization of the complex between PX-DNA and T7 endonuclease I (T7endoI), a junction-resolving protein that could serve as the prototype of an anti-PX ligand (a critical prerequisite for the future development of such tools). Specifically, nuclease-inactive T7endoI was produced and its ability to bind to PX-DNA was analyzed using a gel retardation assay. The molar ratio of PX to T7endoI was determined using gel electrophoresis and confirmed by the Hill equation. Hydroxyl radical footprinting of T7endoI on PX-DNA is used to verify the positive interaction between PX and T7endoI and to provide insight into the binding region. Cleavage of PX-DNA by wild-type T7endoI produces DNA fragments, which were used to identify the interacting sites on PX for T7endoI and led to a computational model of their interaction. Altogether, this study has identified a stable complex of PX-DNA and T7endoI and lays the foundation for engineering an anti-PX ligand, which can potentially assist in the study of molecular mechanisms for HP at an advanced level.

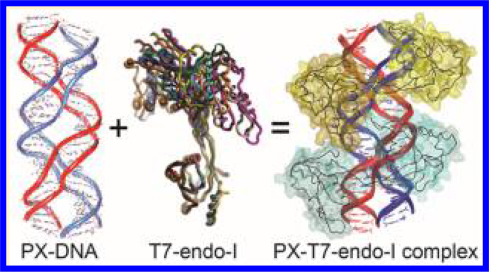

Graphical Abstract

It has been documented that pairing of chromosomal regions with similar or identical DNA sequence occurs in the absence of DNA breakage and recombination. This so-called recombination-independent homologous pairing (abbreviated HP herein) exists in a variety of cellular contexts1,2 and is found to play vital roles in many important biological processes. To name a few, HP is involved in repeat-directed DNA modification in fungi3,4 and in transient association of homologous loci in mammalian somatic nuclei,5 where it proceeds without recombination, yet the homologues still pair and segregate with great regularity. HP also materializes in vegetative, somatic, and germline mitotic cells of Dipteran insects.6,7 In plants, recognition of DNA/DNA HP plays an important role in detecting DNA segments8 present with an inappropriate number of copies before and during meiosis. Moreover, it is known that errors in HP-guided chromosome segregation will normally lead to aneuploidy,9 which may have dramatic effects on infertility and birth defects. Previous studies10–14 have uncovered the presence of higher-order DNA structures when two homologous DNA duplexes associate under physiological conditions in vitro, yet these studies have not provided much insight into the underlying mechanism of these observations due to the lack of an identified motif in such DNA structures. Recently, PX-DNA has been implicated as the DNA motif in HP.15 This notion is supported by experiments that demonstrate that the fusion of two DNA duplexes carrying the sequence feature of PX-DNA can generate a higher-order structure with the predicted length and position after the duplexes are incorporated into a negatively supercoiled plasmid.15

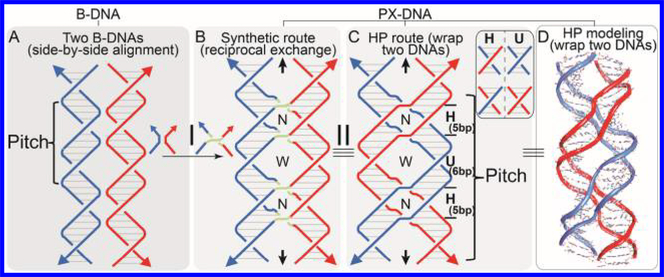

Structurally, PX is a four-stranded coaxial DNA complex in which every nucleotide is paired via Watson–Crick interactions.16,17 From a synthetic standpoint, PX-DNA is created by reciprocal exchange between strands of the same polarity at every possible point where two juxtaposed DNA duplexes, placed side by side, come close to each other (transition from panel A to B of Figure 1). Different variations of PX-DNA have been created.16 Among them, PX-6:5 (major:minor-groove bases) has been widely used in the field of structural DNA nanotechnology18–26 because half of its 22-base helical pitch, 11 bp, is close to that of canonical B-form DNA with 10.5 bp/turn.27,28 Sequences of synthetic PX-DNA in an oligonucleotide system are designed using a sequence symmetry minimization strategy.29,30 Without an external source of energy (described below), Mg2+ ions were proven to be necessary to stabilize the DNA base pairing in a synthetic PX-DNA complex by counteracting the repulsion force resulting from negatively charged DNA phosphate backbones. The strong experimental evidence supporting the formation of DNA crossovers in a synthetic PX-DNA is provided by nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and hydroxyl radical footprinting analysis.16,31,32 The latter is an established and high-resolution method33 used to meticulously demonstrate the formation of DNA crossovers in various DNA motifs (schematically illustrated in Figure S1).31,32,34–40 Thus, when footprinting is combined with base pairing, phosphodiester stereochemistry, and circular dichroism16 derived constraints, the degree of uncertainty in relative atomic positions is believed to be comparable to that of an X-ray crystal structure.

Figure 1.

Formation of PX-DNA from two B-DNAs. (A) Schematic of two side-by-side aligned DNA duplexes, with a blue or red backbone. (B) Synthetic route to PX-DNA formation via reciprocal exchange (I), indicated by light green crossing lines. (C) HP route to PX-DNA formation via wrapping two continuous DNA homologues without the need for a strand break. H (5 bp long) indicates the interhelix regions (blue–red or red–blue strands) that need homology to form PX structure, while U (6 bp long) indicates the intrahelix regions (blue–blue or red–red strands) do not require complementarity for PX formation. (C) The same PX molecule as in panel B with different color coding. Step II indicates the color exchange. (D) MOE modeling of a PX like that in panel C. In panels A–C, horizontal lines indicate DNA base pairs, the 3′ end of a DNA is indicated by an arrow, and the dyad axis of PX is indicated as a pair of black arrows.

Panels C and D of Figure 1 further emphasize that PX-DNA has a paranemic character41,42 because the backbones of the two component duplexes (colored red or blue in the figures) are not linked. Thus, they can be separated from each other without the need for a strand break. In PX, the two double strands interweave with each other in a manner similar to the wrapping of two strands of a double helix (transition from panel A to C of Figure 1), which represents the exact nature of fusing two homologous DNAs into one piece in the absence of DNA breakage. Furthermore, the strands in PX cross each other within the double helices via the blue–blue and red–red intrahelix strand crossings and the blue–red and red–blue interhelix unit tangles. These partial turns within each helix are termed either a major-groove (W) or a minor-groove (N) tangle. To form a PX structure, the PX regions denoted by U (or 6-base intrahelix pairing shown in Figure 2A) (Figure 1C) do not necessarily require complementarity while those half-turn regions labeled H (or 5-base interhelix pairing shown in Figure 2A) require “minimal” homology if the sequences are not designed to minimize sequence symmetry as in synthetic PX-DNA.16 Hence, two DNA double helices are so-called “PX-homologous” if they contain identical sequence in the half-turns labeled H but not necessarily in the half-turns labeled U. It should be noted that because PX homology is a subset of full homology, fully homologous double-stranded DNAs (dsDNAs) should establish PX structure, as well.

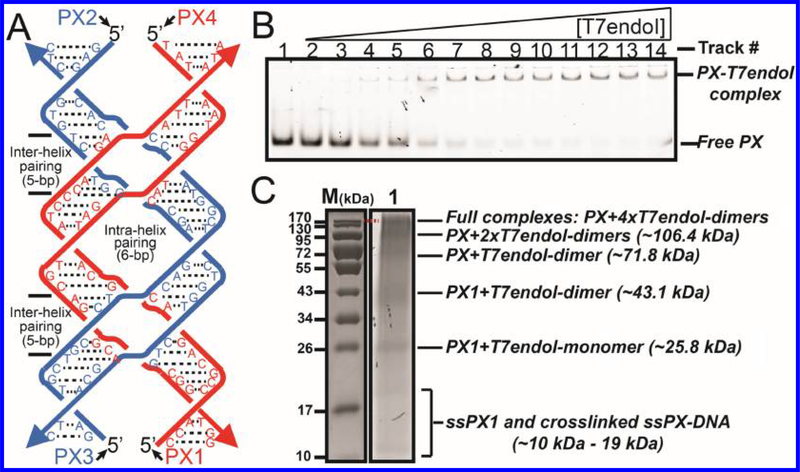

Figure 2.

Binding of T7endoI (E65K) to a PX-6:5 DNA. (A) Sequences of four DNA strands (PX1, −2, −3, and −4) used to assemble the PX-6:5 DNA. The 5 bp interhelix or 6 bp intrahelix pairing (corresponding to H or U in Figure 1C) is indicated. (B) Gel retardation study of PX-T7endoI (E65K) interaction. A fixed concentration (30 nM) of PX-DNA, assembled from 5′-6-fluorescein (FAM)-labeled PX2 and unlabeled PX1, PX3, and PX4, was incubated with 14 different concentrations of the T7endoI homodimer: track 1 (1.27 μM), track 2 (2.54 μM), track 3 (3.81 μM), track 4 (5.08 μM), track 5 (6.35 μM), track 6 (8.89 μM), track 7 (10.16 μM), track 8 (11.43 μM), track 9 (12.70 μM), track 10 (13.97 μM), track 11 (15.24 μM), track 12 (16.51 μM), track 13 (17.78 μM), and track 14 (19.05 μM). The DNA-protein complexes were analyzed on a 6% nondenaturing PAGE gel containing 1× TAE/Mg2+ (10.5 μM). The complex migrates as a well-resolved discrete single band that runs slower than free PX-DNA. (C) Determination of the full PX-T7endoI dimer complex molecular weight (MW) (top band in Figure 2B) using formaldehyde cross-linking on a 10% SDS–PAGE gel. Lane M indicates protein standards (with molecular weights in kilodaltons) on the gel after Coomassie (protein) staining. The same prestaining gel (right gel) was imaged on the basis of the fluorescence signal of PX-DNA. Lane 1 contained the partial and full PX-DNA and T7endoI complexes post-formaldehyde cross-linking. A component of each species is indicated with the calculated MW. The mixture was prepared like that of track 14 in panel B.

As it is still not definitive that PX is the motif found in HP, previous work to this end has demonstrated the fusion of two dsDNAs into a shaftlike structure with a predicted length and position. This was achieved by inserting the dsDNAs carrying a sequence of PX or full homology into a negatively supercoiled plasmid. The fusion is believed to be activated by the Gibbs free energy43 (associated with the negatively supercoiled DNA44 that exists in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes). Such fusion is then driven by the relaxation of DNA supercoiling by forming PX structure in the presence of DNA homology [the formation of PX structure can untwist B-DNA (Figure S2)]. Thus, formation of PX structure in a physiological environment does not require Mg2+ ions. This observation also agrees with the conclusion that every functional output of DNA is shaped by mechanical properties conferred by DNA topology and supercoiling.45 Formation of shaftlike structure was first verified by two-dimensional (2D) gel electrophoresis, an established method used to demonstrate a structural transition from B-DNA to a noncanonical DNA structure, including H-form and Z-DNA, to relax the supercoiled plasmid;46–48 the result excludes the possibility that the shaft structure resulted from a bare DNA-DNA juxtaposition, as predicted by an electrostatic model, because the formation of a regular B-form DNA juxtaposition cannot relax the supercoiled plasmid. Furthermore, AFM (atomic force microscopy) imaging results show that the shafts form in exact regions of the plasmids where PX or fullly homologous DNA segments were inserted. Additionally, DNA psoralen cross-linking data, obtained from both in vitro and in vivo experiments, demonstrate that strands of homology need to interact with each other by forming DNA crossovers like those in PX rather than by establishing a bare DNA-DNA backbone juxtaposition.

Although the observed shaft15 is believed to have a PX structure, such a conclusion has not been validated unambiguously in vivo. Therefore, further investigation is needed but will require development of improved or new molecular and genetic tools. A critical prerequisite for such tool development is the acquisition of a molecular ligand that can specifically recognize PX structure. One solution is to generate anti-PX monoclonal antibodies, which are typical molecular “tags” frequently used in biology and medicine to recognize various entities with high affinity and specificity.49,50 However, as pairing of homologous DNAs is a conserved biological process, it is very hard to raise an effective anti-PX/HP antibody based on an immune response generated from the animal body.

A recent study has shown that the PX motif of DNA can bind to Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Pol-I) based on a whole cell pull-down experiment.51 Because the initiation and main recommendation/repair-independent HP event is a protein-free process, Pol-I should not be an endogenous HP binder. Instead, we speculate that Pol-I may interact with the PX motif via three-way junction-like motifs carried at both ends of a PX-DNA, similar to the structure at the DNA replication fork. However, such interaction is weak, and three-way junctions cannot fully represent the structural signature of PX-DNA. In this study, we seek an alternative strategy for creating a specific anti-PX ligand, starting with rationally selecting a protein prototype targeting the PX structural signature and then characterizing their interaction. As a PX structure is a string of multiple four-way Holliday junctions (HJs) and the crystal structure of the HJ and its selective binding partner, T7endoI protein (BPT7, UniProtKB entry P00641), has been thoroughly investigated previously,52,53 we demonstrated that T7endoI may bind to PX in a defined manner and therefore serve as a protein prototype for engineering an anti-PX ligand with high specificity and affinity. Such a ligand, once obtained, can in turn be used to validate whether the previously observed shaft structure15 is indeed PX structure, which is one motivation for the work presented here.

Specifically, we utilize a one-turn PX-6:5 DNA and nuclease-inactive T7endoI to demonstrate a robust (a 1:4 one-turn PX:dimeric T7endoI molar ratio) and strong [an apparent dissociation constant (KD) for the DNA-protein complex of 7.56 μM4] interaction between PX and T7endoI. The strength of the PX-T7endoI interaction is ~100 times weaker than that of the HJ-T7endoI complex obtained in a previous report,54 which leaves more room to engineer a T7endoI-based anti-PX ligand with a higher specificity and affinity. By coupling the cleavage pattern of PX-DNA by wild-type (WT) T7endoI with the previously reported T7endoI-dimer-HJ crystal structure,53 we performed computational modeling of the PX-T7endoI complex, which enabled us to suggest a detailed model for such a DNA-protein complex structure with atomic resolution. In summary, this report brings us closer to rationalizing the regions of T7endoI that can be mutated to engineer an anti-PX ligand. Future ligand engineering can be achieved through a combinatory approach involving rational protein design55 and direct protein evolution56 (e.g., yeast surface display57).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of DNA Oligonucleotides

All DNA oligonucleotides, unmodified and 5′-6-FAM (fluorescein)labeled, were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The full-length DNA strands were purified using denaturing PAGE. Concentrations of the DNA strands were quantified by using optical density (OD) measurements at 260 nm. Sequences of all of the DNA oligonucleotides used in this report are listed in the Supporting Information.

Denaturing Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) Purification

A denaturing PAGE gel contains 20% acrylamide [19:1 acrylamide:bis(acrylamide) ratio], 8.3 M urea, and 1× TBE buffer [89 mM Tris-HCl, 89 mM boric acid, and 2 mM EDTA (pH 8.0)]. DNA samples subjected to gel purification were first dissolved in a denaturing loading buffer [10 mM NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, 0.25% (w/v) bromophenol blue, and 0.25% (w/v) xylene cyanol FF] and then run on a Hoefer SE-600 vertical electrophoresis unit at 25 V/cm using 1× TBE as the running buffer.

Formation of PX-DNA Structures

Purified single-stranded DNAs (ssDNAs) used to construct PX were mixed in an equal stoichiometric ratio with 1× TAE/Mg2+ [40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 20 mM acetic acid, 2 mM EDTA, and 12.5 mM magnesium acetate]. The formation of half-turn PX-6:5 DNA requires 12.5 mM magnesium acetate in 1× TAE buffer. The mixture was then heated to 90 °C and gradually cooled to 22 °C over 2 h using a TProfessional TRIO Thermocycler.

Nondenaturing Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

Nondenaturing PAGE gels containing 6% or 8% acrylamide [19:1 acrylamide:bis(acrylamide) ratio] were prepared in 1× TAE/Mg2+ buffer as described above. One volume of nondenaturing loading buffer [1× TAE/Mg2+ buffer, 50% glycerol, 0.25% (w/v) bromophenol blue, and 0.25% (w/v) xylene cyanol FF] was added to the annealed PX-DNA samples. The gels were run on a Bio-Rad Mini-PROTEAN Tetra Cell vertical electrophoresis unit at 16 V/cm for 45 min with 1× TAE/Mg2+ as the running buffer. The gel box was cooled in a slurry ice container.

Expression, Purification, and Characterization of Mutant T7 Endonuclease I (E65K)

The genetic code of nuclease-inactive T7endoI, carrying an E65K point mutation,52,53 was optimized using the OptimumGene Codon (GenScript). The DNA segment for the gene was ligated between the NcoI and XhoI restriction sites of protein expression vector pET-19b.58 E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) was transformed to contain the cloned pET-19b plasmid. Expression cultures of transformed BL21 (DE3) cells were grown at 37 °C to an OD of 0.6 at 600 nm and then induced with 0.2 mM IPTG at 22 °C and 200 rpm overnight. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in lysis buffer [50 mM phosphate (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole]. Cells were then lysed with a French press cell disrupter (Thermo Fisher), and cell debris was removed by high-speed centrifugation (4000 rpm for 30 min). The supernatant containing the protein of interest was loaded onto a HisPur Ni-NTA affinity column (Thermo Fisher) precharged with NiSO4. T7endoI (E65K) with the 62-amino acid linker was eluted from the column with elution buffer containing 50 mM phosphate (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 250 mM imidazole. The protein solution was further digested with TEV protease to remove the 62-amino acid linker used to assist in T7endoI protein expression and purification. The cleaved protein product was again loaded onto a Ni-NTA column to remove the linker. The flow-through containing T7endoI was finally dialyzed, at 4 °C for 24 h, against T7endoI storage buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 0.1 mM EDTA]. The molecular weight of the purified protein was verified, in comparison with the protein standards (Thermo Fisher), using 15% SDS–PAGE. The protein solution was further concentrated using a Microcon 10 kDa centrifugal filter unit (EMD Millipore), and its concentration was measured with a Qubit 2.0 fluorometer (Invitrogen).

SDS–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

Uncleaved protein and TEV-cleaved protein were analyzed via 15% SDS– PAGE. Samples were prepared by mixing 12 μL of the respective protein sample with 4 μL of 4× Laemmli Loading Buffer (Amresco) and incubating the mixture for 5 min at 90 °C. The gel was run for 60–90 min at 14 V/cm in 1× TGS buffer (1% SDS, 25 mM Tris base, and 192 mM glycine). Postrun, the gel was stained for 1 h with Coomassie brilliant blue protein stain (0.02% Coomassie blue in 10% aqueous acetic acid). The gel was destained overnight in aqueous methanol (5%) and acetic acid (10%) and then imaged on a Bio-Rad Gel Doc XR+ System using the default protein gel imaging protocol.

Nondenaturing Gel Electrophoresis Shift (retardation) Study of PX-T7endoI (E65K) Interaction

Various amounts of T7endoI (E65K) were incubated with a fixed concentration (30 nM) of 5′-6-FAM-labeled PX-DNA at room temperature for 2 min in 1× TAE/Mg2+. One volume of the nondenaturing loading buffer that contains 1× TAE/Mg2+ buffer, 50% glycerol, 0.25% (w/v) bromophenol blue, and 0.25% (w/v) xylene cyanol FF was added to the PX-T7endoI complex samples before they were loaded onto a nondenaturing PAGE gel. The gels were run on a Bio-Rad Mini-PROTEAN Tetra Cell vertical electrophoresis unit at 22 °C for 3 h (16 V/cm) in 1× TAE/Mg2+ buffer. The gel images were obtained using a GE Typhoon Trio+ instrument. To obtain the apparent KD of the PX-T7endoI-dimer complex, fractions of T7endoI-bound PX-DNA versus the total amount of PX-DNA were calculated on the basis of the quantification of band intensities using ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Formaldehyde Cross-Linking of PX or the PX-T7endoI Complex

Four-stranded PX-DNA that contains 5′-6-FAM-labeled PX1, −2, −3, and −4 was obtained using the thermal annealing protocol described above. To cross-link PX or the PX-T7endoI complex, a formaldehyde solution (2% final concentration) was added to the samples and the samples were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Excess formaldehyde from the PX-DNA or PX-T7endoI cross-linking samples was cleaned up using a Microcon 10 kDa centrifugal filter unit (EMD Millipore) before they were loaded onto a 10% SDS–PAGE gel for analysis.

Maxam–Gilbert (A-G) Sequencing

Each of the 5′-6-FAM-labeled PX-DNA strands (10 pmol of PX1*, PX2*, PX3*, or PX4*, dissolved in 20 μL of water) was kept at 0 °C for 1 h and then treated with 50 μL of formic acid (≈99%) at room temperature for 4 min. After treatment, 180 μL of the HZ-stop solution (0.1 mg/mL tRNA, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.3 M NaAc) was added to the solution, and DNA samples were recovered by ethanol precipitation. After the samples were dried, each was incubated with 100 μL of a 1 M piperidine solution at 90 °C for 20 min. Postreaction, each sample was washed several times with water before it was fully dried, dissolved in denaturing loading buffer, and loaded onto a 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea sequencing gel as a sizing ladder for the hydroxyl radical DNA footprinting assay and PX-DNA cleavage by WT-T7endoI.

Hydroxyl Radical DNA Footprinting

Each of 5′-6-FAM-labeled PX-DNA strands (10 pmol of PX1*, PX2*, PX3*, or PX4*) was treated with A-G sequencing reagents as described above or annealed either with an excess of its unlabeled complementary strand to form a DNA double helix or with the other three unlabeled PX strands to form a PX complex. To anneal, the mixture was heated to 90 °C and gradually cooled to 22 °C over 2 h using a TProfessional TRIO Thermocycler before incubation at 4 °C for 10 min. Hydroxyl radical cleavage of the dsDNA, PX-DNA, and PX-T7endoI complex samples took place at 4 °C for 2 min, as described by Tullius and Dombroski33 with modifications noted by Churchill et al.59 The reaction was quenched by the addition of thiourea. The samples were dried, dissolved in denaturing loading buffer, and loaded onto a 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea sequencing gel. The gel images were obtained using a GE Typhoon Trio+ instrument and quantified using Image Quant (Molecular Dynamics).

Cleavage of PX-DNA by WT-T7endoI

Annealed 5′-6-FAM-labeled PX-DNA structures were incubated with 10 units of WT-T7endoI (New England BioLabs Inc.) at 37 °C for 5 min in 1× reaction buffer [50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT]. The cleavage reaction was terminated by adding an EDTA solution. The samples were then electrophoresed on a 20% polyacrylamide/8 M urea sequencing gel at 80 W for 90 min. The gel images were obtained using a GE Typhoon Trio+ instrument.

Modeling PX-DNA

Atomic coordinates for PX-DNA were generated by using the following procedure in MOE (Molecular Operating Environment, CCG, Montreal, QC). B-DNA double helices were generated for PX1:PX4 and PX3:PX2. The two helices were placed with the helical axes of PX1 and PX3 parallel and with the 5′-phosphates PX1:G12 and PX3:C11 superimposed. The helical pitch for the region (PX1, C6–A22; PX2, T7–G22; PX3, T6–C21; PX4, G7–A22) was adjusted to 11 bases from the standard 10.5-base pitch of B-DNA by applying restrained energy minimization while manually superimposing the projections of the 5′-phosphates of PX2:C12, PX4:G12, PX2:G23, and PX4:C23 on a plane normal to the helical axes. With this as the starting position, the following coordinates were swapped using least-squares superposition of sugar phosphate backbone atoms: PX1:12-GCAATCCCAGA-22 ←→ PX3:11-CAGTCGGTACC-21; PX2:12-CGACTGGTCTG-22 ←→ PX4:12-GATTGCAGGCA-22. All base pairs were energy minimized to convergence using the Amber ff12 force field60 with all hydrogen bond donor–proton distances restrained to 1.8 Å. Special attention was given to the crossover regions using manual modeling, where necessary, to obtain good stereochemistry of the backbone atoms. Other backbone atoms were constrained to their starting positions until convergence of the bases and crossover regions. Finally, all atoms were energy minimized to convergence. As shown in Figure S3, little distortion of the double helix was observed.

Modeling the PX-T7endoI Complex

T7-endoI is a domain-swapped dimer of 2–5–3 αβα three-layered α/β sandwich domains with mostly parallel strand ordering 1–2–3–4–5, with only strand 2 antiparallel to the rest. The domain crossover occurs between strands 1 and 2. The template coordinates for the T7endoI dimer were derived from the crystal structure of the protein bound to the Holliday junction (Protein Data Bank entry 2PFJ).53 Chains A and B of 2PFJ were split into two domains by splicing I45 of chain A to P46 of chain B and vice versa. A single domain was docked to each 5′-phosphate in PX using PyRosetta (script provided in the Supporting Information), conserving the phosphate position and relative orientation of the crystal structure. The resulting pose energies were used to exclude sterically impossible poses. Pairs of poses capable of forming a dimer were identified by the conservation of a 35–40 Å phosphate–phosphate distance that was consistent with the distance between T7endoI active sites. Modeling the symmetrical 2-β-stranded linking region 2×(40-KVPYVIPASNHTYTP-54) was carried out manually in MOE using interactive energy minimization, exploring all sterically allowed β-sheet curvatures.61 Eight dimer poses were energetically possible, but only four of those eight dimers could be bound at any one time due to steric hindrance.

RESULTS

Expression of Mutant T7endoI (E65K)

To analyze the interaction between T7endoI and PX-DNA in the presence of the Mg2+ ion (a key component for stabilizing the four-stranded PX complex with the sequences designed to minimize sequence symmetry16), we have introduced a previously verified amino acid mutation, E65K,52–54 to produce a nuclease-inactive form of T7endoI from WT T7endoI. As illustrated in Figure S4A, the N-terminal domain of the expressed protein contains a TEV protease recognition site, a 62-amino acid linker (see the Supporting Information), and a terminal 10-His affinity tag that allows purification of the overexpressed protein by affinity chromatography on a nickel column. TEV protease was used to cleave off the His tag (which may interfere with T7endoI-PX interaction as suggested in the T7endoI-HJ crystallization study53) of the protein product purified by nickel columns. The 62-amino acid linker was used to help distinguish the His tag-containing protein product from the one cleaved by TEV protease via SDS–PAGE based on their largely distinguishable molecular weights (MWs) (Figure S4B,C). The long amino acid linker can further facilitate the molecular separation between the TEV-cleaved and uncleaved T7endoI by using high-through-put protein purification methods (e.g., FPLC) when a large amount of T7endoI is needed (e.g., for PX-T7endoI co-crystallization).

Formation of the Four-Stranded PX-DNA Complex

As demonstrated previously,16,23 formation of the four-stranded PX-DNA (or half-turn PX) complex in Mg2+containing buffer was first characterized by nondenaturing PAGE analysis. As shown in Figure S5A (Figure S11B for half-turn PX), four ssPX-DNAs can be annealed to form a single DNA species in the presence of 12.5 mM Mg2+ ions, which can fully counteract the repulsion force that resulted from the negatively charged phosphates on the DNA backbone. As a comparison, the presence of the Ca2+ ion at the same concentration is not sufficient to hold the four-stranded PX-DNA complex together (Figure S5B displays partial products). This indicates the necessity of the Mg2+ ion for stabilizing the synthetic PX-DNA complex. Furthermore, hydroxyl radical DNA footprinting was used to further confirm proper formation of the PX-DNA complex because it is an established and high-resolution method33 used to meticulously demonstrate the formation of DNA crossovers in various DNA motifs (schematically illustrated in Figure S1).16,31,32,34–40 More specifically, in the absence of protein, regions of protection were clearly observed at the two DNA bases (indicated by black arrows) flanking each of the PX crossovers when compared with those of dsDNA post-hydroxyl radical cleavage (Figures S1 and S6). This is consistent with the previous observations,16,31,32 which demonstrate that a topologically larger DNA junction can protect the “crossover” DNA bases from the hydroxyl radical attack.

Complex between Nuclease-Inactive T7endoI (E65K) and PX-DNA

As expected, the T7endoI with the E65K mutation was inactive in the cleavage of PX-DNA in the presence of the T7endoI cofactor, Mg2+ ions (data not shown). The protein was further assayed for its ability to bind to the one-turn PX-6:5-DNA (Figure 2A) using the gel retardation (shift) assay. As illustrated in Figure 2B, T7endoI (E65K) was shown to bind to PX-DNA very well by forming a well-defined retarded DNA-protein species on a nondenaturing, Mg2+-containing PAGE gel. To determine the MW of the PX-T7endoI complex and consequently the molar ratio of PX-DNA to T7endoI in such a complex, we used a protein standard and denaturing gel condition. Specifically, we used formaldehyde to cross-link the full PX-T7endoI complex (the DNA-protein complex species shown in lane 14 of Figure 2B) and ran the cross-linked sample side by side with a protein standard on an SDS–PAGE gel (a denaturing gel electrophoresis). Lane 1 in Figure 2C shows six well-resolved species post-formaldehyde cross-linking, which correspond to the fully or partially cross-linked DNA-protein complexes. The top species resolved in the gel (Figure 2C) runs slightly slower than the 170 kDa protein standard species. This indicates that the MW measured by using a protein standard is close to the calculated MW (175.77 kDa) of a PX-T7endoI complex if the complex contains one PX-6:5-DNA (37106.6 Da) and eight T7endoI monomers (8 × 17333.01 Da) [the equivalent of four T7endoI dimers (see the Discussion)]. The result is also corroborated by the computational modeling of the interaction between PX and T7endoI (explicated in the Discussion). To exclude the possibility that the gel species shown in Figure 2C contains only PX-DNA strands, we used formaldehyde to cross-link the PX molecule itself and run it on an SDS–PAGE gel. As shown in Figure S7, cross-linking of the four-stranded PX-DNA did not produce any higher-MW species like those shown in Figure 2C. Furthermore, fractions of T7endoI-bound PX-DNA (see the quantification summary of three trials of the gel retardation assay in Table S1) versus a series of T7endoI (E65K) concentrations were plotted (based on the equation in Table S1) to estimate an average apparent KD for the PX-T7endoI complex of 7.56 μM.4

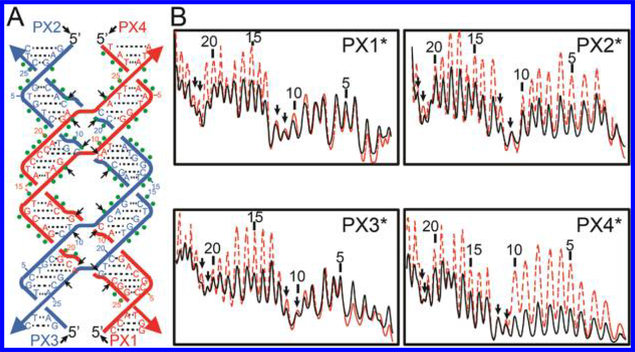

Protection of PX against Hydroxyl Radical Cleavage upon Binding T7endoI

As T7endoI binds to PX-6:5-DNA with a high affinity, we expected that it is plausible to use hydroxyl radicals to attack PX-DNA when it is bound to T7endoI for the protein “footprinting” on PX-DNA. To this end, we incubated PX-DNA (0.5 μM) with a selective 5′-6-FAM label on one of the four PX strands (denoted by PX1*, PX2*, PX3*, or PX4* in Figure 3) with T7endoI (E65K) using the DNA:protein molar ratio determined by the gel retardation (shift) assay (lane 14 in Figure 2B). That ratio confirmed that the PX-DNA in the mixture predominantly stays in the PX-T7endoI complex. The respective DNA double helix (a control that was not included in Figure 3 for the simplification of our data presentation), free PX-DNA, and PX-T7endoI complex were each subjected to hydroxyl radical cleavage for 100 s in the presence of divalent magnesium ions. The cleaved DNA samples were then loaded onto a 20% sequencing gel containing 8 M urea for electrophoresis (Figure S6). Beyond the DNA nucleotides protected by the DNA crossovers (described above), we observed new regions of protection on all four strands (marked by green dots in Figure 3A) upon addition of T7endoI. As summarized in Table S2, the extent of protection of each PX-DNA nucleotide was calculated on the basis of the percent (%) decrease in PX-DNA band intensity in the presence of T7endoI protein (compared to that in the absence of T7endoI).

Figure 3.

Hydroxyl radical footprinting of T7endoI (E65K) on a PX-6:5 DNA. (A) Schematic of the PX-DNA used in the hydroxyl radical footprinting study. Nucleotide positions from the 5′ end of each strand are numbered. Black arrows indicate the DNA nucleotides that flank DNA crossovers and are protected from hydroxyl radical cleavage by topologically larger DNA junctions in the absence of T7endoI. Green dots indicate the DNA nucleotides that are protected from hydroxyl radical cleavage by being bound to T7endoI. (B) Densitometer scans of footprinting gels. These are shown for the four 5′-6-FAM-labeled PX-DNA strands (indicated as PX1*, −2*, −3*, or −4*), where the left side is the 3′ end of the strand. These PX complexes were subjected to hydroxyl radical cleavage in the presence or absence of a stoichiometric quantity of T7endoI (E65K). The red dashed profiles are those of free PX itself, while the black profiles correspond to those of the PX-T7endoI (E65K) complex. Nucleotide positions from the 5′ end of each strand are numbered. Note for both PX and PX-T7endoI complex profiles, protection is seen at nucleotides flanking each PX crossover as indicated by downward-pointing arrowheads.

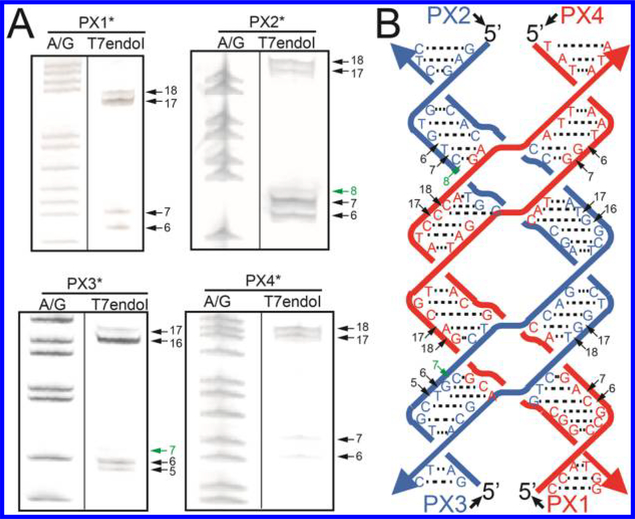

Cleavage of the Four Strands of a PX-6:5-DNA by WT-T7endoI

In this experiment, we incubated PX-DNA (0.5 μM) with one of the four PX strands selectively labeled with 5′-6-FAM (indicated by PX1*, PX2*, PX3*, or PX4* in Figure 4), with WT-T7endoI (10 units, NEB Inc.), and the reaction products were run on a sequencing gel containing 8 M urea. As summarized in Figure 4, all four strands of the PX complex are cleaved and the cleavage sites are predominantly at the fourth and fifth phosphodiester bonds 5′ to the crossover point (indicated by black arrows between G-C-A and C-C-C on PX1, G-T-C and G-G-T on PX2, C-T-G and G-G-T on PX3, and T-G-G and C-A-G on PX4). Note that a very minor cleavage (indicated by green arrows in Figure 4) was seen on the third phosphodiester bond 5′ to the first crossover point of PX2 or PX3. This cleavage pattern suggests a specific rather than a random interaction between PX and WT-T7endoI at its nuclease active site. This cleavage information and the previously reported T7endoI crystal structure52,53 lay a foundation for our computational modeling of the PX-T7endoI complex as discussed below.

Figure 4.

Cleavage of a PX-6:5 DNA by WT-T7endoI. (A) Gel evidence of the cleavage. PX-DNA was constructed by hybridizing the four PX-DNA strands, one of which carries a 5′-6-FAM label, indicated as PX1*, −2*, −3*, or −4*. Each of the four singly labeled PX-DNA molecules was incubated with WT-T7endoI, and the cleavage products were run on a 20% sequencing gel containing 8 M urea. Lane A/G indicates Maxam–Gilbert (A-G) sequencing of each 5′ end fluorescein-labeled PX strand. Positions of the major cleaved phosphodiester bonds on each PX-DNA strand are indicated by arrows as well as the numbers of bases counted from the 5′ end of each strand. Note that a very minor cleavage on PX2 or PX3 is seen (indicated by green arrows). (B) Schematic summary of the positions of major cleavage on the strands of PX-DNA. Phosphodiester bonds cleaved by WT-T7endoI are indicated by arrows as well as the numbers of bases counted from the 5′ end of each strand.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we have chosen a PX-DNA that contains one PX turn (the shortest length that was demonstrated to be sufficient to yield HP in our previous study15) with 6 bases on the major groove and 5 bases on the minor groove (PX-6:5) because half of its 22-base helical pitch, 11 bp, is close to that of canonical B-form DNA with 10.5 bp/turn.27,28 As T7endoI is a junction-resolving protein that is selective for the structure of branched DNA such as HJ53 and PX-DNA contains a series of back-to-back HJs, we hypothesized that a nuclease-inactive T7endoI may bind to PX-DNA in a defined manner. Hence, we have characterized the complex between T7endoI and PX-DNA in the presence of a four-stranded PX stabilizing reagent, Mg2+ ions, by using a previously identified mutant (E65K) of T7endoI.54 T7endoI (E65K) has been shown to be completely inactive as a nuclease but retains ability to bind to the crossover-containing structure. Our study shows that T7endoI (E65K) does not cleave PX-DNA (data not shown) but still binds to the PX-DNA by forming a well-resolved retarded species run on a nondenaturing PAGE gel (Figure 2B). The result is consistent with the conclusion drawn in the T7endoI-HJ complex study,54 which demonstrates the divisibility of the structure-selective binding and catalytic functions of the protein. On the contrary, T7endoI does not bind to dsDNA (Figure S8), indicating its specificity of binding to PX-DNA. Denaturing (formaldehyde cross-linking experiment) gel electrophoresis was used to determine the MW of the PX-T7endoI complex (top band in Figure 2B,C), which is equivalent to the MW of one PX-6:5-DNA plus eight T7endoI monomers. Because T7endoI always remains as a homodimer even in the absence of HJ,52 we conclude that the full PX-T7endoI complex comprises one PX-DNA molecule and four T7endoI dimers. In reference to HJ-T7endoI interaction,53 the dimeric T7endoI enzyme interacts with the backbones of HJ’s helical arms through two binding channels involving seven nucleotides on the two antiparallel arms and cleaves the two continuous noncrossover strands. After binding to T7endoI, the pairs of HJ helical arms are essentially coaxial, but with an interaxial angle of −80°. Compared with the free HJ in solution with an approximately +50° interaxial angle,62,63 the coaxial helical arm in HJ has rotated or been altered by −130° after binding to T7endoI. As each one-turn PX-DNA contains four HJ crossovers, theoretically it should be able to interact with four T7endoI dimers because one T7endoI dimer interacts with one HJ. Our experiments and calculation (Table S1) determined the molar ratio of one-turn PX-6:5 to T7endoI dimer (1:4) agrees with the assumption made above. However, one needs to consider (1) that the helical arms in PX crossovers are parallel and are not as flexible like those in HJ for free rotation and (2) that the two sets of back-to-back HJ-like crossovers within the one-turn PX motif are just a few nucleotides apart. Therefore, PX is not able to interact with dimeric T7endoI in the exact same manner as HJ does. Taking the cleavage pattern of PX-DNA by WT-T7endoI into consideration, we hypothesize that four T7endoI homodimers dock on a one-turn long PX-DNA with two T7endoI dimers on each side of PX, possibly making weak side chain contacts between the dimers at the N-terminal α-helix. This explains why four T7endoI dimers are able to be formaldehyde cross-linked through a bridging PX-DNA molecule. In Figure 2C, we also notice that cross-linking of the full PX-T7endoI complex generates a series of DNA-protein complex species with lower MWs. The observation is expected given that the extent of formaldehyde cross-linking of protein and DNA molecules can never be 100%.64–66 The binding affinity between T7endoI and PX-DNA (with a KD of 7.56 μM4) is relatively strong yet still ~100 times weaker than that of the T7endoI-HJ complex as measured by Duckett et al.54 The proposed tightly coiled conformation (discussed in Future Work) of the two-stranded β-sheet linker region (shown in Figure 5) may contribute strain energy to the bound complex, negatively affecting the affinity. This imperfect PX-T7endoI binding interaction allows us more flexibility and room for the future engineering of an anti-PX ligand that can distinguish itself from the WT T7endoI.

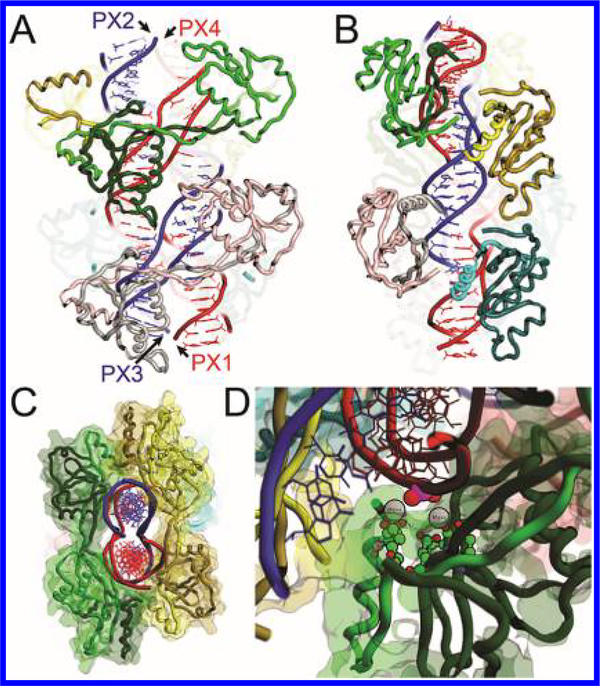

Figure 5.

Molecular models of the PX-T7endoI dimer complex with four dimers (salmon, green, yellow, and cyan) bound to opposite helices: (A) front and (B) side view. The four PX-DNA strands are color-coded as in previous figures. The α-carbon backbones of T7endoI are represented as ribbons. (C) Cut-away image of two T7endoI dimers (light/dark green, light/dark yellow) bound to PX-DNA strands (red and blue). (D) Active site showing carboxylate side chains (E37, D55, and E65) coordinating Mg2+ ions that activate the phosphate oxygens.

To further predict the structure of PX-T7endoI dimer complex in the natural situation, where WT-T7endoI is active in the cleavage of PX-DNA, we have computationally modeled the DNA-protein complex structure using the cleavage pattern of PX-DNA by T7endoI (shown in Figure 4). This modeling study was aided by the previously elucidated crystal structure of the HJ-T7endoI dimer complex.53 Docking of PX and T7endoI was carried out using PyRosetta67 with a customized script (see the Supporting Information), and further modeling was carried out using the interactive molecular modeling tool MOE.68 The cleavage sites on individual PX strands were paired by discovery of a single phosphate–phosphate distance (35–39 Å) that was consistent with the range of flexibility of the T7endoI dimer. These pairs bridge PX1 positions 18, 19, 7, and 8 and PX4 positions 8, 7, 19, and 18, respectively, and PX3 positions 6, 7, 17, and 18 and PX2 positions 19, 18, 8, and 7, respectively. Docking of a “single-head” model using PyRosetta showed that only the observed cleavage sites are sterically possible, due to collisions between the protein and the DNA in all other positions (Figure S9). In modeling the dimer, we found that by altering the curvature of the connecting linker between the two domains of the enzyme, it was possible to bridge two of the cleavage sites without steric hindrance. In all, eight possible poses for the manually altered T7endoI dimer were found by automated docking and manual modeling. This model agrees with the MW determined by the formaldehyde-cross-linked PX-T7endoI complex from the SDS–PAGE gel (Figure 2C) and with the locations of the predominant cleavage points obtained in the PX cleavage assay (Figure 4). The sterically allowable poses are consistent with cleavage sites on the same helix at the first and second positions 3′ to the crossover, specifically, at the 5′-phosphates of PX1 (C7, A8, C18, and C19), PX2 (T7, C8, G18, and T19), PX3 (T6, G7, G17, and T18), and PX4 (G7, G8, A18, ans G19). The cleavage pattern produced by a single T7endoI dimer would be a four-base 5′ overhang. Four T7endoI dimers, binding as shown in Figure 5 and with complete digestion at all sites, would produce four double-stranded breaks, each with a four-base 5′ overhang and with the loss of the 12- or 13-base intervening segment in each chain, where the precise lengths depend on which of the alternative poses is present.

Note that this computationally derived model is used in lieu of a crystal structure with full awareness of the weaknesses in nucleic acid force fields and in vacuo energy minimization.69 For instance, force fields for nucleic acids do not model the electrostatic effects of dynamic electronic polarization between stacked bases. The implicit solvent model of Amber ff1260 corrects for the decay of electrostatic repulsion between the highly charged phosphate backbones using a distance-dependent dielectric constant but does not adequately model the particle nature of solvent and its influence on stacking geometry. Dihedral angle energies are a rough approximation based on a truncated Fourier series with its associated assumptions of parametric independence and sinusoidal symmetry and were optimized only on canonical A- and B-DNA,70 whereas we are modeling a double helix with an 11-base pitch, halfway between B-DNA and A-DNA. Despite these caveats, we argue that the constraints on the structure imposed by the crossovers and the assumption of Watson–Crick base pairing throughout leave little room for alternative conformations of the DNA. Our model and our conclusions with regard to the docking of the enzyme T7endoI do not depend on the reasoned small degrees of structural uncertainty in the DNA structure, because the protein has its own range of motion that may accommodate those uncertainties. The flexible linker region, residues 40–54, may adopt a range of bend angles and curvatures as seen in crystal structures of close homologues of T7endoI (Figure S10), giving the head-to-head relative orientation a range of as much as 180° and 30 Å.

To further validate the model, we have assembled a half-turn PX-6:5 DNA (see the Supporting Information) and then tested binding with T7endoI via the gel retardation assay using the same DNA and protein concentrations as demonstrated sufficiently for producing stable PX-T7endoI in Figure 2B. In comparison with the half-turn PX itself (lane 1 of Figure S11C), no mobility shift of the mixture containing half-turn PX-DNA and T7endoI protein with proper protein:DNA ratios was observed. The absence of binding to the half-turn PX and the presence of four bound dimers to the one-turn PX suggest that dimer binding is cooperative. This is the basis for choosing a Hill equation and/or plot71 to determine the KD of the PX-(T7endoI-dimer)4 complex. Half-turn PX presents binding sites for only two dimers, with minimal contacts between them (Figure 5C). We propose that, in one-turn PX-DNA (the same applies to longer PX-DNA), T7endoI dimers stack along the axis of the double helix as shown in panels A and B of Figure 5. The stacking of dimers presents a mechanism for cooperative binding through interactions between residues 98–104 on the third α-helix and the C-terminal segment of residues 140–145 on an adjacent dimer, also between the regions surrounding E83 and K103.

The emerging model for the PX-(T7endoI-dimer)4 complex (Figure 5) is mostly consistent with our hydroxyl radical footprinting of PX-DNA on binding T7endoI (Figure 3) by providing protections of the DNA nucleotides (bases 13–26 on PX-1, 3–19 on PX-2, 12–25 on PX-3, and 1–25 on PX-4) from hydroxyl radical cleavage. Because the interaction between T7endoI and the PX motif depends on the presence of the junction structure of PX-DNA rather than specific DNA sequences and the four PX strands are structurally identical to each other in terms of DNA backbone, all four PX strands should have displayed the same protection pattern or a very similar one. However, we need to point out that our current model is a more static than dynamic interpretation of the DNA molecule. As in-solution DNA footprinting takes place under dynamic circumstances, one possible explanation for such a discrepancy is that PX segments along the axis may show different rigidity or, in other words, show different degrees of deformation after binding to T7endoI, which may be sequence-dependent and difficult to simulate. Therefore, we admit that our current model cannot correlate fully with the observed protection pattern. Nonetheless, after evolving and/or developing a specific anti-PX ligand, as one of our future research goals, we seek a DNA-protein crystal structure that can help us to gain more insight into this matter.

FUTURE WORK

One of the major driving motivations of these studies is to evolve an anti-PX ligand with high specificity and affinity. A preliminary modeling study shows that the hypothesized strain that was placed on the linker region of T7endoI (residues 43–51) could be relieved by shortening or lengthening the chain.72 A longer linker could possibly disfavor one of the poses (with a shorter intrasite distance) and favor the other, producing a blunt-end cut instead of a one-base 3′ overhang, and would allow a more relaxed curvature of the connecting β-sheet linker region. We propose that fusing the monomers by adding a short linker would possibly increase the affinity for the complex by decreasing the folding entropy and by spanning the major groove to interact with the sugar phosphate backbone of the next helical turn. We also propose that PX-DNA specificity may be enhanced by side chain remodeling of the N-terminal helices where they form a dimer/dimer interface that bridges opposite duplexes, as shown in Figure 5C, as this structure is present in PX-DNA but not in single-duplex DNA.72 Relevant to DNA nanotechnology, success in the development of an anti-PX ligand may open up a new research avenue for evolving novel protein ligands that can specifically recognize and therefore track other designer DNA motifs and/or nanostructures73 when they are used in in vitro or in vivo biological applications. Furthermore, such novel protein ligands can expand and diversify the number of DNA-motif binding proteins, enhancing the self-assembly capability of a recently developed molecular origami method74,75 that uses dsDNA scaffolds and protein staples to create hybrid nanostructures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are thankful for the valuable discussions and suggestions from the members in the research groups of C.B. and X.W.

Funding

This work was supported by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) start-up funds provided to X.W., a Slezak Memorial Fellowship to M.K., an RPI SURP fellowship to I.D.H., and National Institutes of Health Grant R01-GM099827 to C.B.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00057.

Illustration of a hydroxyl radical footprinting result displayed by a schematic sequencing gel (Figure S1), schematic of fusing two homologous duplexes into a shaftlike structure initiated by the free energy associated with the supercoiled plasmid (Figure S2), PX-DNA model colored by docking score (Figure S3), amino acid sequence of T7endoI (E65K) and gel evidence of protein production (Figure S4), characterization of PX-DNA formation using nondenaturing PAGE (Figure S5), gel image of hydroxyl radical footprinting of T7endoI on PX-6:5 DNA (Figure S6), formaldehyde cross-linking of PX-6:5-DNA (Figure S7), binding of dsDNA to T7endoI (Figure S8), summary of PyRosetta modeling results (Figure S9), superposed crystal structures of close homologues of T7endoI (Figure S10), binding of T7endoI (E65K) to half-turn PX-6:5-DNA (Figure S11), determination of dissociation constant (KD) of the PX-T7endoI dimer complex (Table S1), extents of protection of the PX-6:5-DNA by T7endoI against hydroxyl radical attack (Table S2), sequence of the 62-amino acid linker (Note-1), PX-DNA sequence used in this study (Note-2), PyRosetta script for the computational modeling of the PX-T7endoI complex (Note-3), a summary of PyRosetta modeling results (Note-4), and references (PDF)

REFERENCES

- (1).Barzel A, and Kupiec M (2008) Finding a match: How do homologous sequences get together for recombination? Nat. Rev. Genet 9, 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Zickler D, and Kleckner N (2015) Recombination, pairing, and synapsis of homologs during meiosis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol 7, a016626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Selker EU (1990) Premeiotic instability of repeated sequences in Neurospora crassa. Annu. Rev. Genet 24, 579–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Rossignol JL, and Faugeron G (1994) Gene inactivation triggered by recognition between DNA repeats. Experientia 50, 307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Apte MS, and Meller VH (2012) Homologue pairing in flies and mammals: gene regulation when two are involved. Genet. Res. Int 2012, 430587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Wolf KW (1994) How meiotic cells deal with non-exchange chromosomes. BioEssays 16, 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Joyce EF, Apostolopoulos N, Beliveau BJ, and Wu CT (2013) Germline progenitors escape the widespread phenomenon of homolog pairing during Drosophila development. PLoS Genet. 9, No. e1004013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Mlynarova L, Jansen RC, Conner AJ, Stiekema WJ, and Nap J-P (1995) The MAR-mediated reduction in position effect can be uncoupled from copy number dependent expression in transgenic plants. Plant Cell 7, 599–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hassold T, and Hunt P (2001) To err (meiotically) is human: the genesis of human aneuploidy. Nat. Rev. Genet 2, 280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Danilowicz C, Lee CH, Kim K, Hatch K, Coljee VW, Kleckner N, and Prentiss M (2009) Single molecule detection of direct, homologous, DNA/DNA pairing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 19824–19829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Strick TR, Croquette V, and Bensimon D (1998) Homologous pairing in stretched supercoiled DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 95, 10579–10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Inoue S, Sugiyama S, Travers AA, and Ohyama T (2007) Self-assembly of double-stranded DNA molecules at nanomolar concentrations. Biochemistry 46, 164–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Baldwin GS, Brooks NJ, Robson RE, Wynveen A, Goldar A, Leikin S, Seddon JM, and Kornyshev AA (2008) DNA double helices recognize mutual sequence homology in a protein free environment. J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 1060–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Nishikawa J-I, and Ohyama T (2013) Selective association between nucleosomes with identical DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 1544–1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wang X, Zhang X, Mao C, and Seeman NC (2010) Double-stranded DNA homology produces a physical signature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 107, 12547–12552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shen Z, Yan H, Wang T, and Seeman NC (2004) Paranemic crossover DNA: a generalized Holliday structure with applications in nanotechnology. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 1666–1674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wang X, Chandrasekaran AR, Shen Z, Ohayon YP, Wang T, Kizer ME, Sha R, Mao C, Yan H, Zhang X, Liao S, Ding B, Chakraborty B, Jonoska N, Niu D, Gu H, Chao J, Gao X, Li Y, Ciengshin T, and Seeman NC (2018) Paranemic crossover DNA: There and back again. Chem. Rev, DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chakraborty B, Sha R, and Seeman NC (2008) A DNA-based nanomechanical device with three robust states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 17245–17249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ding B, and Seeman NC (2006) Operation of a DNA robot arm inserted into a 2D DNA crystalline substrate. Science 314, 1583–1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gu H, Chao J, Xiao SJ, and Seeman NC (2009) Dynamic patterning programmed by DNA tiles captured on a DNA origami substrate. Nat. Nanotechnol 4, 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gu H, Chao J, Xiao SJ, and Seeman NC (2010) A proximity-based programmable DNA nanoscale assembly line. Nature 465, 202–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yan H, Zhang X, Shen Z, and Seeman NC (2002) A robust DNA mechanical device controlled by hybridization topology. Nature 415, 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zhang X, Yan H, Shen Z, and Seeman NC (2002) Paranemic cohesion of topologically-closed DNA molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 124, 12940–12941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Liao S, and Seeman NC (2004) Translation of DNA signals into polymer assembly instructions. Science 306, 2072–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Shen WL, Liu Q, Ding BQ, Shen ZY, Zhu CQ, and Mao CD (2016) The study of the paranemic crossover (PX) motif in the context of self-assembly of DNA 2D crystals. Org. Biomol. Chem 14, 7187–7190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Shen WL, Liu Q, Ding B, Zhu CQ, Shen Z, and Seeman NC (2017) Facilitation of DNA self-assembly by relieving the torsional strains between building blocks. Org. Biomol. Chem 15, 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Rhodes D, and Klug A (1980) Helical periodicity of DNA determined by enzyme digestion. Nature 286, 573–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Wang JC (1979) Helical repeat of DNA in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 76, 200–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Seeman NC (1982) Nucleic acid junctions and lattices. J. Theor. Biol 99 (2), 237–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Seeman NC (1990) De novo design of sequences for nucleic acid structure engineering. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn 8, 573–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lin C, Wang X, Liu Y, Seeman NC, and Yan H (2007) Rolling circle enzymatic replication of a complex multi-crossover DNA nanostructure. J. Am. Chem. Soc 129, 14475–14481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Lin C, Rinker S, Wang X, Liu Y, Seeman NC, and Yan H (2008) In vivo cloning of artificial DNA nanostructures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 17626–17631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Tullius TD, and Dombroski B (1985) Iron(II) EDTA used to measure the helical twist along any DNA molecule. Science 230, 679–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Kimball A, Guo Q, Lu M, Cunningham RP, Kallenbach NR, Seeman NC, and Tullius TD (1990) Construction and analysis of parallel and antiparallel holliday junctions. J. Biol. Chem 265, 6544–6547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Wang Y, Mueller JE, Kemper B, and Seeman NC (1991) Assembly and characterization of five-arm and six-arm DNA branched junctions. Biochemistry 30, 5667–5674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Du S, Zhang S, and Seeman NC (1992) DNA junctions, antijunctions, and mesojunctions. Biochemistry 31, 10955–10963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Fu T-J, and Seeman NC (1993) DNA double-crossover molecules. Biochemistry 32, 3211–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Zhang S, and Seeman NC (1994) Symmetric Holliday junction crossover isomers. J. Mol. Biol 238, 658–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).LaBean T, Yan H, Kopatsch J, Liu F, Winfree E, Reif JH, and Seeman NC (2000) Construction, analysis, ligation, and self-assembly of DNA triple crossover complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 122, 1848–1860. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wang X, and Seeman NC (2007) Assembly and characterization of 8-Arm and 12-Arm DNA branched junctions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 129, 8169–8176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).McGavin S (1971) Models of specifically paired like (homologous) nucleic acid structures. J. Mol. Biol 55, 293–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Wilson JH (1979) Nick-free formation of reciprocal heteroduplexes: a simple solution to the topological problem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 76, 3641–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Vologodskii AV, Lukashin AV, Anshelevich VV, and Frankkamenetskii MD (1979) Fluctuations in superhelical DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 6, 967–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Gilbert N, and Allan J (2014) Supercoiling in DNA and chromatin. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 25, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kleckner N (2016) Questions and assays. Genetics 204, 1343–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Gellert M, Mizuuchi K, O’Dea MH, Ohmori H, and Tomizawa J (1979) DNA gyrase and DNA supercoiling. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol 43, 35–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Rich A, Nordheim A, and Wang A-J (1984) The chemistry and biology of left-handed Z-DNA. Annu. Rev. Biochem 53, 791–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Mirkin SM, Lyamichev VI, Drushlyak KN, Dobrynin VN, Filippov SA, and Frank-Kamenetskii MD (1987) DNA H form requires a homopurine–homopyrimidine mirror repeat. Nature 330, 495–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Park K, Tomlins SA, Mudaliar KM, Chiu YL, Esgueva R, Mehra R, Suleman K, Varambally S, Brenner JC, MacDonald T, Srivastava A, Tewari AK, Sathyanarayana U, Nagy D, Pestano G, Kunju LP, Demichelis F, Chinnaiyan AM, and Rubin MA (2010) Antibody-based detection of ERG rearrangement-positive prostate cancer. Neoplasia 12, 590–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Huang RP, Huang RC, Fan Y, and Lin Y (2001) Simultaneous detection of multiple cytokines from conditioned media and patient’s sera by an antibody-based protein array system. Anal. Biochem 294, 55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gao X, Gethers M, Han S-P, Goddard WAI, Sha R, Cunningham RP, and Seeman NC (2019) The PX motif of DNA binds specifically to Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I. Biochemistry 58, 575–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Hadden JM, Convery MA, Déclais A-C, Lilley DM, and́ Phillips SE (2001) Crystal structure of the Holliday junction resolving enzyme T7 endonuclease I. Nat. Struct. Biol 8, 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Hadden JM, Declais AC, Carr SB, Lilley DM, and Phillips SE (2007) The structural basis of Holliday junction resolution by T7 endonuclease I. Nature 449, 621–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Duckett DR, Giraud Panis M-JE, and Lilley DM (1995) Binding of the junction-resolving enzyme bacteriophage T7 endonuclease I to DNA: separation of binding and catalysis by mutation. J. Mol. Biol 246, 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Wilson CJ (2015) Rational protein design: developing next-generation biological therapeutics and nanobiotechnological tools. Wires Nanomed. Nanobi 7, 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Packer MS, and Liu DR (2015) Methods for the directed evolution of proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet 16, 379–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Cherf GM, and Cochran JR (2015) Applications of yeast surface display for protein engineering. Methods Mol. Biol 1319, 155–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Studier FW, Rosenberg AH, Dunn JJ, and Dubendorff JW (1990) Use of T7 RNA-polymerase to direct expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 185, 60–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Churchill MEA, Tullius TD, Kallenbach NR, and Seeman NC (1988) A Holliday recombination intermediate is twofold symmetric. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 85, 4653–4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Zgarbova M, Luque FJ, Sponer J, Cheatham TE 3rd, Otyepka M, and Jurecka P (2013) Toward improved description of DNA backbone: Revisiting epsilon and zeta torsion force field parameters. J. Chem. Theory Comput 9, 2339–2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Max N, Hu C, Kreylos O, and Crivelli S (2009) BuildBeta–a system for automatically constructing beta sheets. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet 78, 559–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Ortiz-Lombardia M, Gonzalez A, Eritja R, Aymami J, Azorin F, and Coll M (1999) Crystal structure of a DNA Holliday junction. Nat. Struct. Biol 6, 913–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Eichman BF, Vargason JM, Mooers BH, and Ho PS (2000) The Holliday junction in an inverted repeat DNA sequence: sequence effects on the structure of four-way junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 97, 3971–3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Solomon MJ, and Varshavsky A (1985) Formaldehyde-mediated DNA-protein crosslinking: a probe for in vivo chromatin structures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 82, 6470–6474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Toth J, and Biggin MD (2000) The specificity of protein-DNA crosslinking by formaldehyde: In vitro and in drosophila embryos. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, No. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Lu K, Ye WJ, Zhou L, Collins LB, Chen X, Gold A, Ball LM, and Swenberg JA (2010) Structural characterization of formaldehyde-induced cross-links between amino acids and deoxynucleosides and their oligomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc 132, 3388–3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Chaudhury S, Lyskov S, and Gray JJ (2010) PyRosetta: a script-based interface for implementing molecular modeling algorithms using Rosetta. Bioinformatics 26, 689–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).MOE Molecular Operating Environment, 2013.08 (2017) Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Mackerell AD, Wiorkiewiczkuczera J, and Karplus M (1995) An all-atom empirical energy function for the simulation of nucleic-acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 117, 11946–11975. [Google Scholar]

- (70).Cheatham TE, and Case DA (2013) Twenty-five years of nucleic acid simulations. Biopolymers 99, 969–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Hill AV (1910) The possible effects of the aggregation of the molecules of haemoglobin on its dissociation curves. J. Physiol 40, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- (72).Hooper WF, Walcott BD, Wang X, and Bystroff C (2018) Fast design of arbitrary length loops in proteins using InteractiveRosetta. BMC Bioinf. 19, 337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Seeman NC (2001) DNA nicks and nodes and nanotechnology. Nano Lett. 1, 22–26. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Praetorius F, and Dietz H (2017) Self-assembly of genetically encoded DNA-protein hybrid nanoscale shapes. Science 355, No. eaam5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Douglas SM (2017) Bringing proteins into the fold. Science 355, 1261–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.