Abstract

Cell death and inflammation are interdependent host responses to infection. During pyroptotic cell death, interleukin-1β (IL-1β) release occurs through caspase-1 and caspase-11–mediated gasdermin D pore formation. In vivo, responses to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) result in IL-1β secretion. In vitro, however, murine macrophages require a second “danger signal” for the inflammasome-driven maturation of IL-1β. Recent reports have shown caspase-8–mediated pyroptosis in LPS-activated macrophages but have provided conflicting evidence regarding the release of IL-1β under these conditions. Here, to further characterize the mechanism of LPS-induced secretion in vitro, we reveal an important role for cellular FLICE-like inhibitory protein (cFLIP) in the regulation of the inflammatory response. Specifically, we show that deficiency of the long isoform cFLIPL promotes complex II formation, driving pyroptosis, and the secretion of IL-1β in response to LPS alone.

Inflammatory responses to infection are mediated via nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades downstream of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and are crucial for host survival. These responses up-regulate various effectors, including cytokines, chemokines, and prosurvival factors (1). Many pathogens have evolved to block host signaling cascades, promoting pathogen survival (2). The Yersinia species bacteria rely on the effector protein YopJ to block activation of the level 3 MAPK TAK1 (transforming growth factor β–activated kinase) (3, 4). In response, host cells limit infection via initiation of cell death pathways (5), such as pyroptosis, which is accompanied by interleukin-1β (IL-1β) release.

Pyroptosis is mediated via the inflammasome-driven activation of caspase-1 (CASP1) and caspase-11 (CASP11), resulting in cleavage of the pore-forming protein gasdermin D (GSDMD) (6–8). In macrophages, IL-1β maturation requires two signals to up-regulate pro-IL-1β and to induce NOD, LRR and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3)–mediated maturation of IL-1β (9). Interaction of NLRP3 with apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) recruits pro-CASP1, which cleaves and releases mature IL-1β via pores formed by GSDMD (10).

Recently, we and others reported caspase-8 (CASP8)–mediated pyroptosis in response to Yersinia infection. Pyroptosis was dependent on YopJ and could be mimicked with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and the small-molecule inhibitor of TAK1, 5Z-7-oxozeaenol (5z7) (11, 12). Cell death required the kinase activity of receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIP1) and GSDMD (Fig. 1A) but was accompanied by low IL-1β levels (fig. S1A), likely owing to the inhibition of MAPK- and NF-kB–mediated pro-IL-1β production.

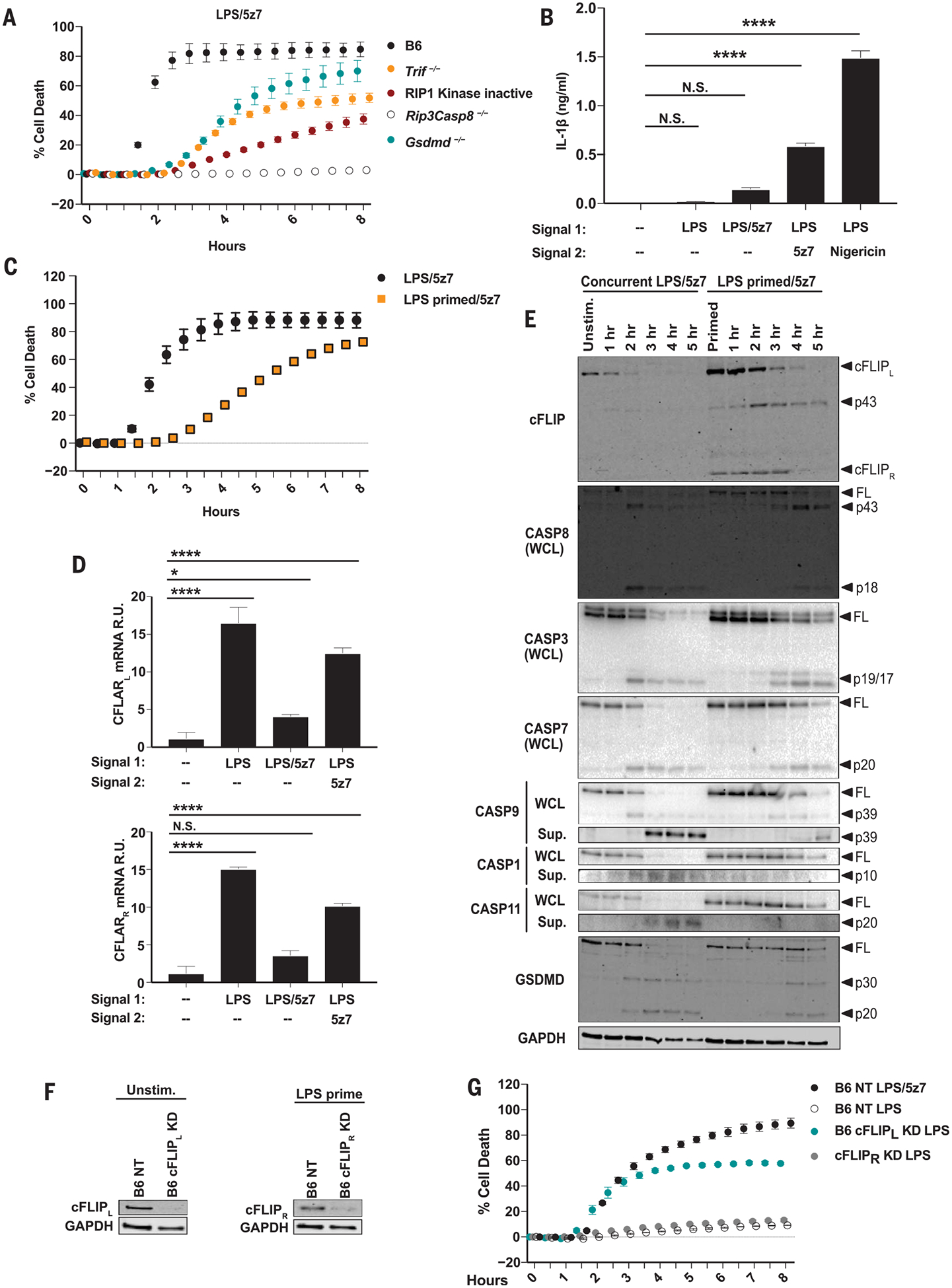

Fig. 1. LPS priming before TAK1 inhibition drives IL-1β release, inhibits cell death, and regulates cFLIP levels.

(A) Cell death in BMDMs from B6, RIP1 kinase-inactive (RIP1Ki), Trif−/−, Rip3−/−Casp8−/−, and Gsdmd−/− mice treated concurrently with LPS/5z7. (B) IL-1β release from B6 BMDMs 6 hours after indicated treatments. LPS pre-priming (10 or 100 ng/ml) occurred 4 hours before the addition of 5z7 or nigericin, respectively. (C) Cell death in B6 BMDMs stimulated concurrently with LPS/5z7 or LPS–pre-primed/5z7. (D) Relative Cflar mRNA levels, normalized to Gapdh (glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase) after 1 hour of treatment with LPS, LPS/5z7, or LPS–pre-primed/5z7 treatment in B6 BMDMs. R.U., relative units. (E) Full-length (FL) and cleaved products of cFLIP, GSDMD, and indicated caspases from whole-cell lysates (WCL) or precipitated from the supernatant (Sup.) of B6 BMDMs treated concurrently with LPS/5z7 or LPS–pre-primed/5z7 for indicated times. Unstim., unstimulated; hr, hours. (F) cFLIP protein levels in B6 BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or cFLIPR or transduced with a nontargeting (NT) control. (G) Cell death in B6 BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or cFLIPR and stimulated as indicated [extent of KD shown in (F)]. Data from cell death assays and immunoblots are representative of three or more independent experiments, and cell death data are presented as the mean ± SD of triplicate wells. IL-1β release data are presented as the mean ± SD for triplicate wells from three or more independent experiments. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison between groups: N.S., nonsignificant (P > 0.05); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01;***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs) pre-primed with LPS before 5z7 treatment produced significantly higher levels of IL-1β compared with cells concurrently treated with LPS and 5z7 (Fig. 1B). IL-1β release in LPS–pre-primed BMDMs was dependent on TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-b (TRIF), RIP1 kinase activity, and CASP8 (fig. S1B). Notably, LPS-induced pro-IL-1β production was entirely dependent on TRIF. Additionally, at later time points, pro-IL-1β levels were dependent on CASP8 and RIP1 kinase activity (fig. S1C). IL-1β production was independent of GSDMD, suggesting an alternate mechanism for IL-1β release (fig. S1B). Finally, IL-1β secretion in LPS–pre-primed BMDMs was mediated by NLRP3 inflammasome components (fig. S1D).

LPS pre-priming delayed cell death (Fig. 1C), which hinted at a mechanism in which LPS stimulation drives the expression of prosurvival factors that are inhibited by 5z7. We identified these factors by comparing genome-wide mRNA levels in BMDMs treated with LPS or both LPS and 5z7 (fig. S2A). Among many differentially expressed transcriptional modulators, we identified Cflar, a gene encoding the enzymatically inactive ho-molog of CASP8, cFLIP (fig. S2A). The 25-kDa short isoform cFLIPR blocks CASP8 activation entirely, and the 55-kDa long isoform cFLIPL blocks it partially (13, 14). LPS–pre-primed BMDMs maintained Cflar mRNA levels after the addition of 5z7 (Fig. 1D). Both cFLIPL and cFLIPR protein levels were elevated in LPS–pre-primed BMDMs (Fig. 1E). In LPS/5z7- activated BMDMs, cFLIPL was cleaved within 2 hours, whereas in LPS–pre-primed BMDMs this loss was delayed. cFLIPL cleavage coincided with the kinetics of CASP8 cleavage and the onset of cell death (Fig. 1, C and E). In agreement with the protective role of the partially active CASP8-cFLIPL heterodimer, we observed enhanced CASP8 cleavage to the locally active p43 fragment in LPS–pre-primed BMDMs, whereas cleavage to p18 was nearly abolished (Fig. 1E). LPS pre-priming delayed the activation of CASP1, CASP3, CASP7, CASP9, and CASP11, and the cleavage of GSDMD, suggesting that cellular stores of cFLIP, regulated by TAK1, determine the rate and extent of LPS/5z7-induced death (Fig. 1E).

Notably, a knockdown (KD) of cFLIPL but not cFLIPR sensitized cells to death after stimulation with LPS alone (Fig. 1, F and G), with comparable kinetics of LPS/5z7-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 1G). The silencing effect was gene-specific and dependent on TRIF but not on myeloid differentiation primary response protein MyD88, reinforcing the role of cFLIPL as a regulator of cell death downstream of TAK1 inhibition (fig. S2, B to F).

Ablation of TRIF and RIP1 kinase activity reversed the effect of cFLIPL KD (Fig. 2A and fig. S3A). Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) co-staining revealed the early appearance of exclusively PI+ cells in LPS-activated cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 2B and fig. S3B), which suggested that the mechanism of cell death in LPS-activated cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs differed from LPS/5z7-driven death. Unlike LPS/5z7-induced cell death, cFLIPL deficiency–mediated cell death lacked CASP3, CASP7, or CASP9 activation (fig. S3, C and D). Instead, CASP1 and CASP11 were fully activated in LPS-stimulated cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 2C and fig. S3C). cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs stimulated with LPS exhibited robust CASP8 activation, and CASP1 and CASP11 cleavage was completely dependent on CASP8 (Fig. 2C and fig. S3, C, E, and F). Inhibition of CASP3 and CASP7 delayed death after LPS/5z7 treatment, but not in LPS-activated cFLIPL-KD BMDMs (Fig. 2E and fig. S3G).Furthermore, LPS-driven death required CASP8 and GSDMD but not NLRP3, CASP1, or CASP11 (Fig. 2, E to G, and fig. S3, H to J). This suggests that cFLIPL deficiency strictly promotes pyroptosis upon LPS activation. By contrast, both apoptosis and pyroptosis are activated in the context of LPS/5z7 (11, 12).

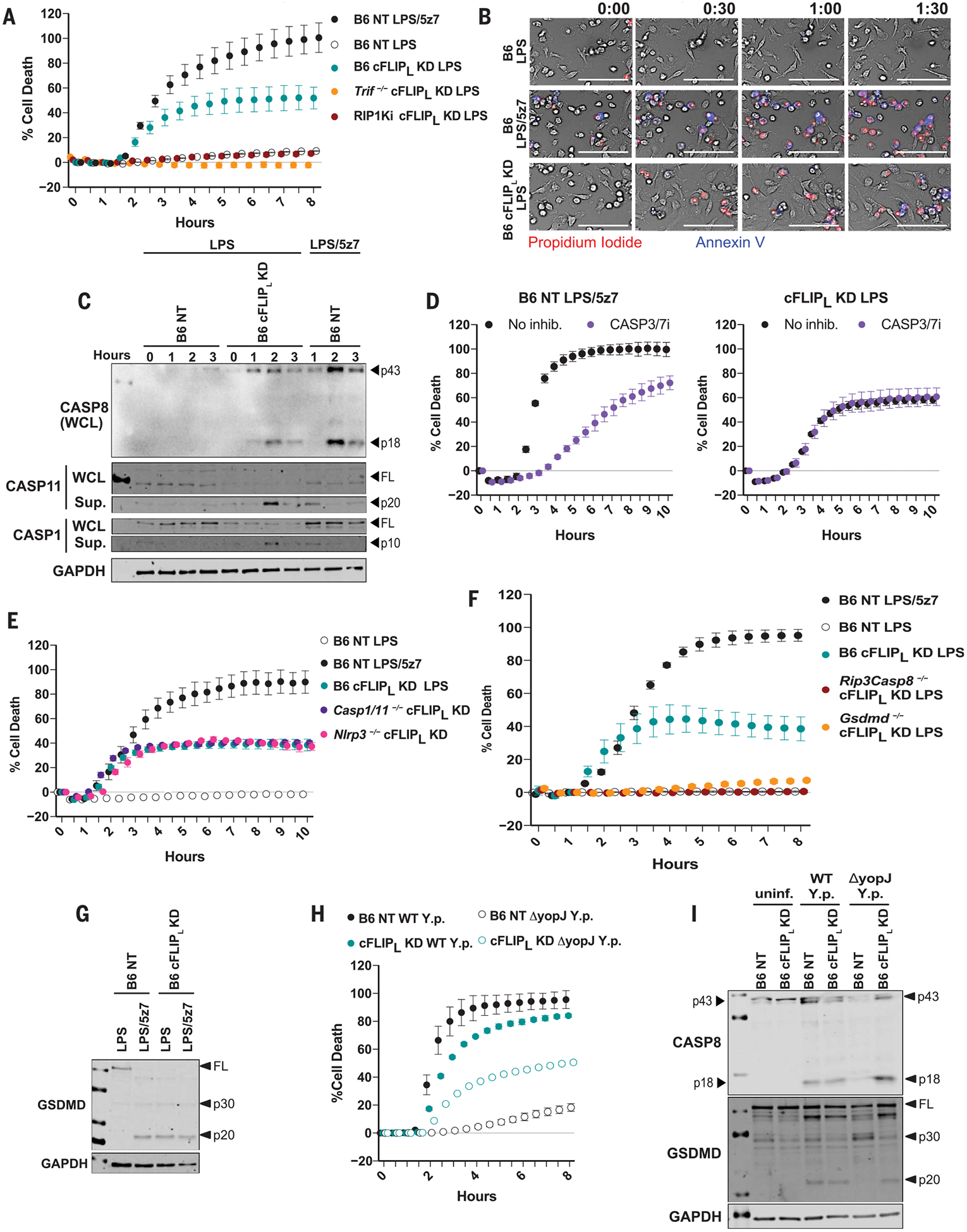

Fig. 2. LPS induces caspase-8–mediated pyroptosis in the absence of cFLIPL.

(A) Cell death in B6, Trif−/−, and RIP1Ki BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL and stimulated as indicated (extent of KD shown in fig. S3A). (B) Kinetic 20× magnification imaging of PI incorporation and annexin V staining in B6 and B6 cFLIPL-KD BMDMs stimulated with LPS or LPS/5z7 for up to 1 hour and 30 min (extent of KD shown in fig. S3B). Scale bars: 100 mm. (C) Full-length and cleaved products of indicated caspases from whole-cell lysates (WCL) or precipitated from the supernatant of B6 NT control or B6 cFLIPL-KD BMDMs (extent of KD shown in fig. S3C). (D) Inhibition of cell death with CASP3/7 inhibitor in LPS/5z7-stimulated B6 macrophages or LPS-treated cFLIPL-KD BMDMs (extent of KD shown in fig. S3G). (E) Cell death in B6, Nlrp3−/−, and Casp1−/−Casp11−/− macrophages stimulated with LPS or LPS/5z7 (extent of KD shown in fig. S3H). (F) Cell death in B6, Rip3−/−Casp8−/−, and Gsdmd−/− BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL and stimulated as indicated (extent of KD shown in fig. S3I). (G) Full-length and cleaved GSDMD from B6 NT control or B6 cFLIPL-KD BMDMs stimulated as indicated (extent of KD shown in fig. S3J). (H) Cell death and (I) cleavage of CASP8 and GSDMD in B6 NT and B6 cFLIPL-KD BMDMs stimulated with WT or YopJ deficient (DyopJ) Y. pseudotuberculosis (extent of KD shown in fig. S3L). uninf., uninfected. All immunoblots and cell death data are representative of three or more independent experiments. Cell death data are presented as the mean ± SD of triplicate wells.

The cFLIPL KD removed the requirement for TAK1 inhibition for the induction of pyroptosis. Similarly, YopJ was not required for Yersinia-induced death. YopJ-deficient Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (DyopJ) induced cell death and the cleavage of CASP8 and GSDMD in cFLIPL-KD BMDMs alone (Fig. 2, H and I, and fig. S3L). Thus, silencing of cFLIPL recapitulates the effects of TAK1 inhibition (either by YopJ or 5z7 treatment), implicating cFLIPL as one of the main regulators of pyroptosis in response to LPS.

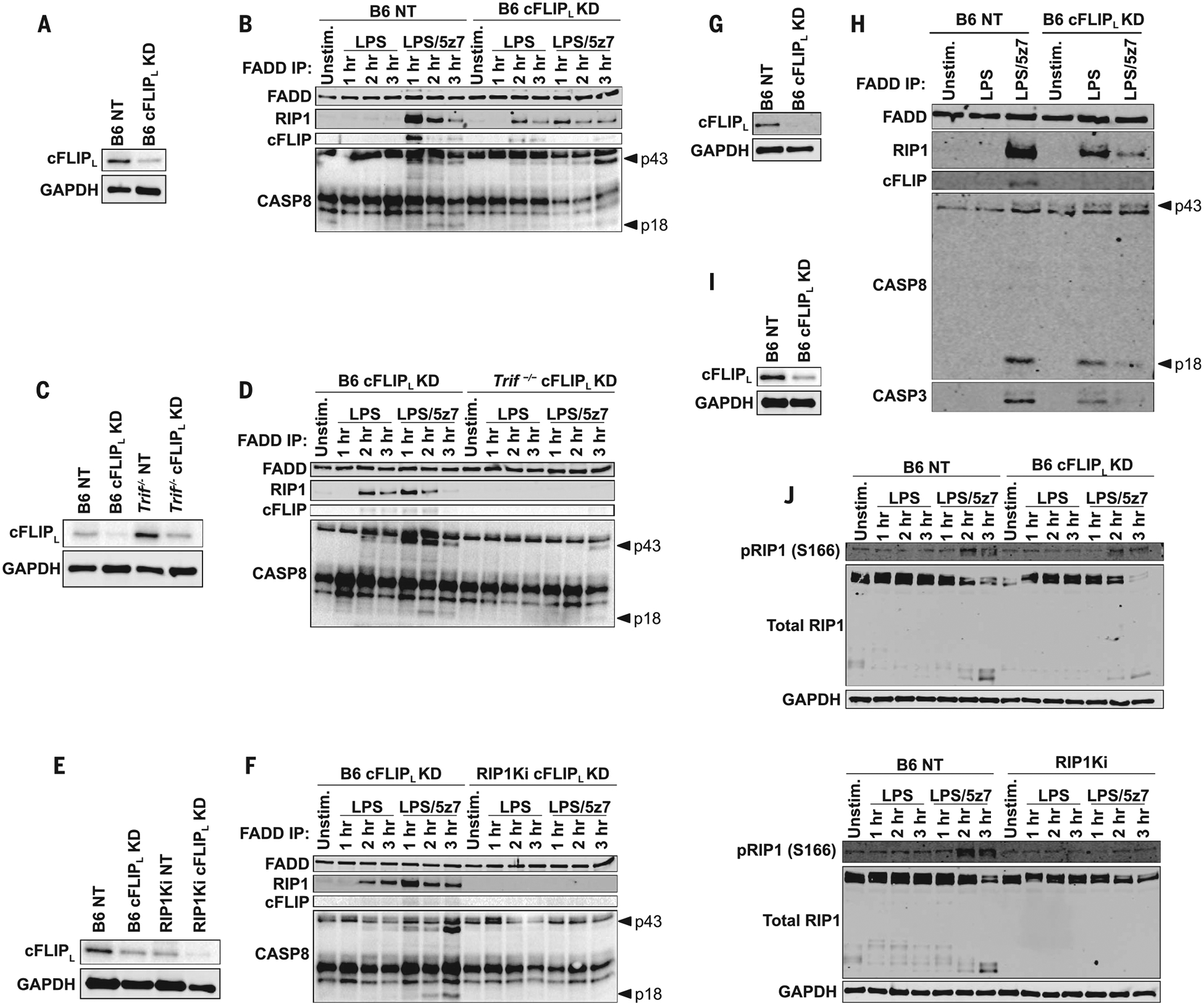

cFLIPL deficiency was sufficient to drive complex II formation in response to LPS. RIP1 and CASP8 recruitment to the FAS-associated death domain (FADD) occurred as early as 2 hours after LPS addition (Fig. 3, A and B). Notably, LPS/5z7 also drove complex II formation, and cFLIPL was detected in the complex at early time points. LPS-induced complex II formation in cFLIPL-KD cells was dependent on TRIF and RIP1 kinase activity (Fig. 3, C to F).LPS/5z7 induced phosphorylation of RIP1 at Ser166 (S166) and promoted CASP3 binding in complex II. However, these modifications were not required for complex II formation and LPS-induced cell death in cFLIPL-KD cells (Fig. 3, G to J). Thus, cFLIPL and the kinase activity of RIP1 regulate complex II formation downstream of TRIF signaling and determine the extent and mode of cell death.

Fig. 3. cFLIPL deficiency promotes complex II formation downstream of TRIF in response to LPS.

(A) cFLIPL protein levels in B6 BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or transduced with a NT control. (B) FADD immuno-precipitation (IP) in B6 NT and B6 cFLIPL-KD BMDMs stimulated as indicated and probed for complex II components [extent of KD shown in (A)]. (C) cFLIPL protein levels in B6 and Trif−/− BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or transduced with a NT control. (D) FADD IP in B6 and Trif−/− BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL, stimulated as indicated, and probed for complex II components [extent of KD shown in (C)]. (E) cFLIPL protein levels in B6 and RIP1Ki BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or transduced with a NT control. (F) FADD IP in B6 and Trif−/− BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL, stimulated as indicated, and probed for complex II components [extent of KD shown in (E)]. (G) cFLIPL protein levels in B6 BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or transduced with a NT control. (H) FADD IP in B6 NT and B6 cFLIPL-KD stimulated for 2 hours as indicated and probed for complex II components [extent of KD shown in (G)]. (I) cFLIPL protein levels in B6 BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL or transduced with a NT control. (J) Total and pRIP1 (S166) levels in LPS- and LPS/5z7-stimulated cFLIPL silenced or NT control B6 and RIP1Ki BMDMs [extent of KD shown in (I)]. All immunoblots are representative of three or more independent experiments.

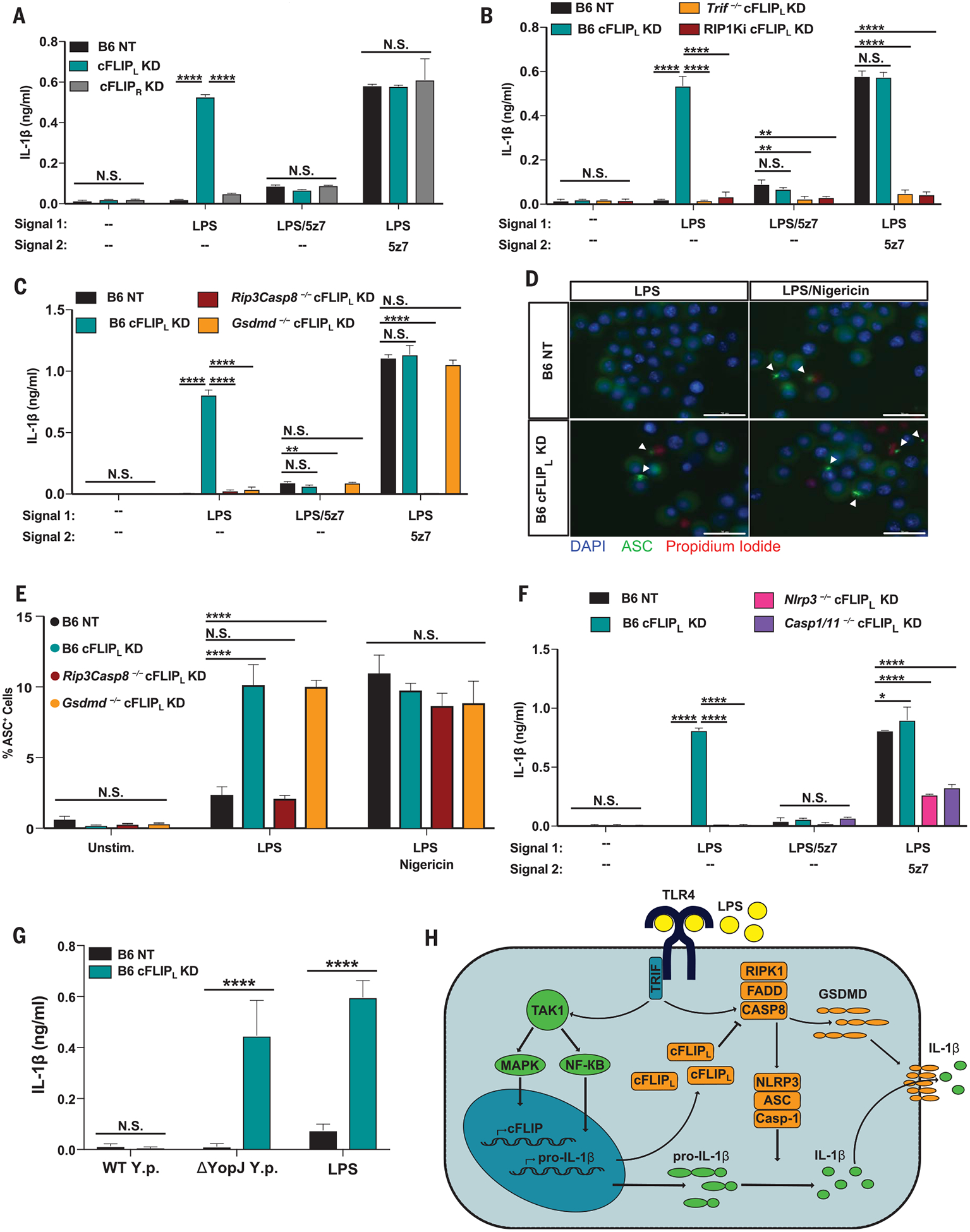

A single signal from LPS elicited robust IL-1β secretion in cFLIPL-KD BMDMs (Fig. 4A and fig. S4A). Similar to death, the effect of cFLIPL-silencing on IL-1β production was dependent on TRIF, CASP8, GSDMD, and the kinase activity of RIP1 (Fig. 4, B and C, and fig. S4, B and C). This implicates GSDMD as the sole effector of pyroptosis and IL-1β release in cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs. To confirm inflammasome activation in response to LPS, we observed a substantially higher percentage of ASC speck positive cells in cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs compared with wild-type (WT) (Fig. 4D and fig. S4, D and E). Furthermore, cFLIPL-deficiency-driven ASC speck formation was CASP8-dependent but GSDMD-independent (Fig. 4E and fig. S4F), and NLRP3 and CASP1/11 deficiency abrogated IL-1β release in cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs (Fig. 4F and fig. S4G). Thus, CASP8 plays a critical role in inflammasome activation and IL-1β maturation, whereas GSDMD is required for the release of IL-1β. Finally, LPS-induced IL-1β production in cFLIPL-deficient BMDMs required potassium efflux, as excess extracellular potassium inhibited ASC speck formation and IL-1β release (fig. S4, H to J). Confirming the specificity of the short hairpin RNA–based approach, small interfering RNA–induced silencing of cFLIPL resulted in death (fig. S3K) and IL-1β production (fig. S4K) in response to LPS alone, both of which were dependent on TRIF, CASP8, GSDMD, and the kinase activity of RIP1.

Fig. 4. cFLIPL deficiency drives IL-1β maturation and release in response to a single signal from LPS.

(A to C) IL-1β release from (A) B6 NT control, B6 cFLIPL-KD, and B6 cFLIPR-KD BMDMs; (B) RIP1Ki and Trif−/− BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL; and (C) RIP3/CASP8 and GSDMD-deficient BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL after 6 hours of indicated treatments (extent of KD shown in fig. S4, A to C). (D) Representative 60× images of ASC specks in B6 NT control and B6 cFLIPL-KD BMDMs stimulated for 4 hours with LPS, or 2 hours with LPS/nigericin (extent of KD shown in fig. S4D). Scale bar: 30 mm. (E) Percentage of ASC+ cells in B6, Rip3−/−Casp8−/−, and Gsdmd−/− BMDMs knocked down for cFLIPL (extent of KD shown in fig. S4F). (F) IL-1β release in B6, Nlrp3−/−, and Casp1−/−Casp11−/− macrophages silenced for cFLIPL and stimulated as indicated (extent of KD shown in fig. S4G). (G) B6 BMDMs silenced for cFLIPL and stimulated with WT or YopJ-deficient (DyopJ) Y. pseudotuberculosis for 6 hours (extent of KD shown in fig. S4L). (H) Model of LPS-driven pyroptosis and IL-1β production, as regulated by cFLIPL. IL-1β release and ASC percentage data are presented as the mean ± SD for triplicate wells from three or more independent experiments. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparison between groups: N.S., nonsignificant (P > 0.05); *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

BMDMs deficient in cFLIPL released IL-1β in response to DyopJ but not WT Yersinia (Fig. 4G and fig. S4L), further supporting LPS-induced IL-1β production (Fig. 2H). Notably, the same titer of DyopJ Yersinia elicited both IL-1β secretion (Fig. 4G) and cell death (Fig. 2H). These data show a crucial role for cFLIPL in regulating CASP8 activation and complex II formation, protecting macrophages against LPS-induced pyroptosis. Indeed, skewing toward the increased production of cFLIPL confers resistance to LPS cytotoxicity in vivo (15). This underscores the importance of cFLIPL as a key regulator of cell death and inflammation.

In macrophages, and perhaps in other cells, if levels of cFLIPL are sufficiently high, CASP8 activation and pyroptosis are inhibited (Fig. 4H).When cFLIPL levels are low, CASP8 homo-dimers form readily. Fully active CASP8 cleaves and activates distant targets, and LPS-activated macrophages rapidly undergo pyroptosis and secrete IL-1β. CASP3, CASP7, and CASP9 are dispensable for CASP8-driven pyroptosis in the absence of cFLIPL. Instead, CASP8 likely directly activates GSDMD to drive pyroptosis and the NLRP3 inflammasome to drive IL- 1β maturation and release.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Fitzgerald and A. Degterev for sharing various mouse strains for this study. We thank A. Tai and the Tufts University Genomics Core for help with RNA sequencing and data analysis. We thank S. Bunnell for access to and advice for confocal imaging and K. Munger for access to the Amaxa Nucleofector System.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants AI135369 and AI056234 to A.P.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data are available in the main text or the supplementary materials.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

science.sciencemag.org/content/367/6484/1379/suppl/DC1

Materials and Methods

Figs. S1 to S4

MDAR Reproducibility Checklist

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.O’Neill LA, Golenbock D, Bowie AG, Nat. Rev. Immunol 13, 453–460 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reddick LE, Alto NM, Mol. Cell 54, 321–328 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mukherjee S et al. , Science 312, 1211–1214 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paquette N et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 109, 12710–12715 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park JM, Greten FR, Li ZW, Karin M, Science 297, 2048–2051 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT, Nat. Rev. Microbiol 7, 99–109 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aglietti RA et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 7858–7863 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He WT et al. , Cell Res. 25, 1285–1298 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vince JE, Silke J, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 73, 2349–2367 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X et al. , Nature 535, 153–158 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarhan J et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 115, E10888–E10897 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orning P et al. , Science 362, 1064–1069 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuchiya Y, Nakabayashi O, Nakano H, Int. J. Mol. Sci 16, 30321–30341 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fu TM et al. , Mol. Cell 64, 236–250 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ram DR et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 113, 1606–1611 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.