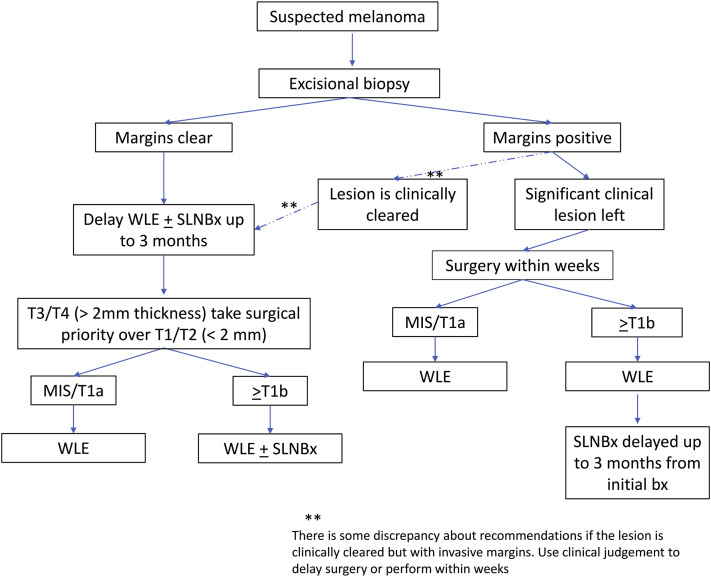

To the Editor: During the COVID-19 shutdown, the standard of care for melanoma treatment has been temporarily modified. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and Society of Surgical Oncology recommended that excisional biopsies be performed whenever possible and that wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy be deferred for up to 3 months for lesions with clear histologic margins (Fig 1).1 , 2 This decision was justified by the claim that “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay,” but the supporting evidence has not been clearly presented.

Fig 1.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network and Society of Surgical Oncology's short-term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during the COVID-19 pandemic. MIS, melanoma in situ; SLNBx, sentinel lymph node biopsy; WLE, wide local excision.

We performed a literature review and identified 7 studies that address surgical delay and melanoma survival (see Supplementary Materials for references and study details; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/wyx96j2pcj.2). Of these, 5 studies examined outcomes related to 1 month or longer melanoma surgical delay, which was the relevant timeframe for COVID-19 recommendations. Of the 5 publications, 3 reported no decrease in survival. McKenna et al. showed no survival effects for delaying surgery 30 to 90 days (15-28 d: hazard ratio [HR], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.54-1.39; 29-42 d: HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.55-1.54; 43-91 d: HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.54-1.56), using a study design that included only melanomas with excisional biopsies.3 Carpenter et al. and Crawford et al. similarly did not find any association between delayed melanoma surgery and mortality. Eight of 9 studies also showed that delayed sentinel lymph node biopsy did not increase mortality.

In contrast, Conic et al. and Basnet et al. concluded that delayed wide local excision increases mortality, but they provide only a single counterexample, as both studied the same data set (the National Cancer Database).4 , 5 These studies had a large sample size and showed a consistent pattern of association: as more time passed, survival decreased. Unlike investigators in other studies, Conic et al. stratified their analysis by melanoma stage and followed patients for 3 years instead of 5. They found a significant risk in patients with stage I disease (30-50 d: HR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01-1.1) 60-89 d: HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.07-1.25). Similar to other studies, they did not find increased mortality when all stages were combined (30-59 d: HR, 1.02; 95% CI, 0.99-1.04; 60-89 d: HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.99-1.08 or when patients were followed up for 5 years instead of 3 (stage 1, 30-59 d: P = .06; 60-89 d: P = .09; Supplemental Reference Conic et al; available via Mendeley at https://doi.org/10.17632/wyx96j2pcj.2). Basnet et al.'s findings are currently only available as an abstract publication, limiting comprehensive review of study details.

In summary, 1 large retrospective study reported a significant association of mortality with surgical delay in patients with stage I melanoma, but several other smaller studies did not detect any significant hazards. There is insufficient evidence to definitively conclude that delayed wide resection after gross removal of the primary melanoma is without harm. Like many of the COVID-19 policy decisions, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network/Society of Surgical Oncology guidelines were not strictly evidence-based and were drafted expeditiously when resources were limited and COVID-19 mortality was mounting. Patients with melanoma are typically older (average age, 65 y), often have medical comorbidities, and may have increased all-cause mortality if they contract COVID-19. The contradictory evidence cannot be resolved until a sufficiently powered prospective trial that measures harms from surgical delay and controls for factors such as the effect of patient concern is published.

Footnotes

Funding sources: None.

Conflicts of interest: None disclosed.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

Reprints not available from the authors.

References

- 1.Society of Surgical Oncology Resource for management options of melanoma during COVID-19. 2020. https://www.surgonc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Melanoma-Resource-during-COVID-19-3.23.20.pdf 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. Available at:

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Short term recommendations for cutaneous melanoma management during COVID-19 pandemic. Accessed July 13, 2020. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/Melanoma.pdf

- 3.McKenna D.B., Lee R.J., Prescott R.J., Doherty V.R. The time from diagnostic excision biopsy to wide local excision for primary cutaneous malignant melanoma may not affect patient survival. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:48–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conic R.Z., Cabrera C.I., Khorana A.A., Gastman B.R. Determination of the impact of melanoma surgical timing on survival using the National Cancer Database. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basnet A., Wang D., Sinha S., Sivapiragasam A. Effect of a delay in definitive surgery in melanoma on overall survival: a NCDB analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(15 suppl):e21586. [Google Scholar]