The coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic resulted in rapid and widespread interruption to health care, impacting national, regional, and local health care systems and practices. Postponement of nonurgent care was recommended at a national level and across all major medical professional societies.1 , 2 Decisions to postpone or cancel hundreds of thousands of nonurgent and elective surgeries and procedures were aimed to slow the spread of COVID-19 and preserve resources, including ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE). In addition, most states implemented stay-at-home orders, further prompting patients to defer care. In a matter of days, the COVID-19 pandemic abruptly dismantled one of health care’s top priorities, namely, access to high-quality care, pursuant to competing public health priorities.

The Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system, the largest integrated health system in the United States, can serve as a powerful model to assess the impact of COVID-19 on access to care. Composed of 170 medical centers and 1074 outpatient sites, the VA serves >6 million veterans annually. Hundreds of thousands of procedures and surgeries are performed annually across the VA, providing critical health services for veterans. Gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures are among the most common ambulatory procedures performed, accounting for approximately 400,000 veteran visits annually. Herein, we describe the process, timeline, and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gastrointestinal endoscopy in the VA and suggest potential opportunities to address access challenges in the COVID-19 era.

Process and Timeline

The VA acted swiftly to provide official guidance on elective endoscopy procedures, reflecting the urgency to conserve PPE, protect veterans and providers, prepare for a possible COVID surge, and flatten the curve of incident infections.3 The rapid response underscores both the pace of the COVID-19 pandemic and the need for communication across the VA health care system to ensure staff, physician and patient safety:

-

•

3/15/20 Deputy Undersecretary for Health for Operations and Management Guidance for Elective Gastroenterology and Hepatology Procedures. 3 Facilities were directed to cease all nonurgent and elective procedures no later than Wednesday, March 18.

-

•

3/18/20 Primary Care memo “Guidance for COVID-19 Pandemic response.”4 Primary care providers were issued guidance to order nonendoscopic colorectal cancer screening (eg, fecal immunochemical testing [FIT]) rather than refer veterans for average-risk screening colonoscopy due to postponement of elective procedures.

-

•

4/2/20 Guidance for Prioritization of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Consults from the National Gastroenterology Program Office. 5 The National Gastroenterology Program Office provided guidance on procedure postponement, including clinical indications that are generally nonurgent or elective, and to offer FIT to veterans who were awaiting screening colonoscopy.3 The guidance recommended prioritization of procedures based on the indication and time sensitivity (Figure 1 ). For example, urgent procedures that should be performed despite the active COVID-19 pandemic (eg, acute gastrointestinal bleeding) are deemed Priority 1. Routine cases that are not particularly time sensitive, such as an average risk screening colonoscopy due this year, should be classified as Priority 4.

-

•

4/20/20 Consult Prioritization Toolbox was implemented across VA. The Consult Toolbox, which is embedded within the electronic health record and assists VA providers with consult management, was modified to facilitate documentation of a clinical priority score on each consult (Supplementary Figure 1). This tool was paired with a secure website application to produce reports for clinical service departments. These reports were designed to facilitate tracking of all patients awaiting clinical care, including sorting by priority and the clinically indicated date for care. This electronic tool was developed by VA informatics leaders and was deployed to >350,000 VA computers over a period of several days in April 2020. The framework of the toolbox offered individual services the flexibility to define priority levels.

-

•

5/18/2020 VHA Guidance for Resumption of Procedures for Nonurgent and Elective Indications. 5 This guidance on when and how to resume elective procedures, including endoscopy, outlined a process for risk stratifying patients and procedures to facilitate appropriate use of preprocedure viral testing, use of PPE and environment of care processes (eg, room downtime and cleaning).

-

•

6/5/20 The National Average Risk Colorectal Screening Reminder was updated with an option for sites to disable colonoscopy / sigmoidoscopy ordering. Owing to the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on elective procedures, increased focus on nonendoscopic screening was encouraged. Therefore, VA facilities were allowed to remove the quick order option for ordering a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy in the average risk CRC reminder and preferentially use FIT testing in veterans for CRC screening. Screening colonoscopy could still be ordered outside of the quick order functionality.

Figure 1.

Recommended prioritization and suggested indications for Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) endoscopy referrals during the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) consult toolbox screenshot for prioritizing consults during the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic.

On June 9, 2020,6 the VA initiated a phased reopening process whereby 1–2 facilities that met prespecified COVID-19 epidemiology criteria in each VA network were authorized to resume limited face-to-face care. This phased process includes careful monitoring of the impact of reopening on COVID epidemiology, availability of PPE, and other resources.

Impact

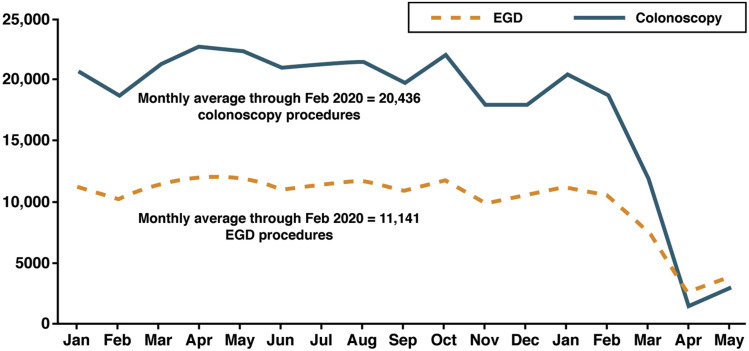

Across the VA health care system, gastrointestinal endoscopy procedure volume decreased precipitously in accordance with the policy requirements and guidance described elsewhere in this article (Figure 1). Compared with a historical (January 2019–February 2020) monthly national average of 11,141 upper gastrointestinal endoscopies per month, there was a 33% and 78% decrease in esophagogastroduodenoscopy volume in March and April, respectively (Figure 2 ). Compared with a historical average of 20,436 colonoscopies per month, there was a 42% and 93% decrease in colonoscopy volume in March and April 2020, respectively. There was a slight increase in May procedure volume, likely owing to implementation of the prioritization process.

Figure 2.

Impact of the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic. and subsequent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) policies on endoscopy procedure volume.

The rapid deferral of procedures was operationalized at the local level with assistance of the Consult Toolbox. As of July 7, 2020, a total of 54,441 gastrointestinal endoscopy consults have been given a priority score based on the guidance provided by the GI National Program office. Overall, 9300 consults were categorized as Priority 1 (17.1%), 19,253 as Priority 2 (35.4%), 14,565 as Priority 3 (26.8%), and 11,323 as Priority 4 (20.8%). From a national sample of 22,783 prioritized colonoscopy consults with an annotated indication, 39.0% of the diagnostic colonoscopy consults are Priority 1 and 47.4% are Priority 2, whereas 30.0% of the surveillance colonoscopy consults are Priority 2, 36.4% Priority 3, and 30.0% are Priority 4. Among screening colonoscopies, 30.7% are Priority 2, 24.7% are Priority 3, and 41.8% are Priority 4.

The ability to quickly produce these reports allows sites to identify and schedule patients in need of care according to their triaged priority. The prioritization process, which includes clinical review of the electronic health record, also provides an opportunity to assess if colonoscopic surveillance can be safely deferred based on new polyp surveillance guidelines from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer.7

Discussion and Conclusions

The impact of COVID-19 on health care systems across the United States is unprecedented in modern history. Appropriately, the initial focus was on preparation for the expected surge of patients infected with COVID-19 likely to need care across the United States and in VA hospitals. These efforts not only focused on securing PPE, staffing, and resources (eg, ventilators), but also required cancellation and deferral of elective procedures and surgeries. Gastroenterology services are performed at a very high volume across the VA health care system. In addition to potential exposure of patients and staff to the severe acute respiratory syndrome associated with coronavirus-2 through the performance of aerosol-generating procedures like endoscopy, these procedures also require a large quantity of PPE for admission, procedure, and recovery room staff, as well as the staff who are responsible for the reprocessing of the endoscopes. For many endoscopy indications (eg, diagnostic procedures for symptoms), urgency can be difficult to stratify. National guidance was critical in providing the impetus to rapidly implement triage and postponement of nonurgent endoscopy procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The VA reacted swiftly, but at the same time there are sweeping repercussions, both immediate and delayed, in such a massive postponement of procedures. Unlike ambulatory clinic visits, which can be converted to telephone or video telehealth visits, endoscopic procedures require the physical presence of the patient within the health care facility. Studies have documented significant COVID-19–related concerns of patients and health care staff alike that will have lasting impacts on endoscopy.8 , 9 Contrary to the precipitous decrease in procedure volume, the VA saw a 1025% increase in telehealth video appointments since March 1, 2020.10

The endoscopic procedure data presented reveal a massive care de-escalation intervention of historic proportions that would have been previously unthinkable in a national health care system serving 6 million people. Based on historic trends and the change from the historical monthly average procedure volume, we can estimate that after 3 months of de-escalation, approximately 64,000 gastroenterology procedures have been deferred in VA. The number of veterans with postponed and deferred endoscopic care will undoubtedly continue to increase for many months to come, despite plans to resume some nonurgent procedural care. The VA Moving Forward Plan11 and recently issued guidance on resuming nonurgent and elective procedures,5 establish recommendations for preprocedure screening and testing, PPE, and additional postprocedural environmental cleaning, as well as maintaining surge capacity that will result in decreased endoscopy productivity compared with pre-COVID levels.

Adhering to the mantra “Do no harm,” the VA’s priority is ensuring that deferred care does not lead to adverse patient outcomes (eg, delayed diagnosis of colorectal cancer). The prioritization framework allows sites to quickly track those cases that should be performed as soon as possible (Priority 2). However, prioritization status is not static, because a previously nonurgent procedure may transition to a higher priority over time. For example, updated VA prioritization guidance classifies abnormal FIT results as Priority 2 within 3 months of the test result, but as Priority 1 after 3 months, reflecting published studies of the association between time from FIT-positive results to diagnostic colonoscopy with advanced colorectal cancer.12 , 13 Fortunately, sites will be able to monitor the duration of postponement and reprioritize those with significant wait times. The resumption of procedures will involve balancing risk, resources and the uncertain trajectory of the ongoing pandemic.14

We have also witnessed multiple opportunities to increase future access to endoscopic care for veterans. The recently updated colorectal polyp surveillance guidelines extended the time interval for follow-up colonoscopy in many situations, based on updated data on risk of cancer.7 For example, whereas a patient previously found to have 1–2 small adenomas would have been recommended to have another colonoscopy in 5–10 years, with most patients receiving a 5-year surveillance recommendation, the new guidelines have extended this interval to 7–10 years. Thus, patients now due for a 5-year colonoscopy can be deferred until 2022 or even as late as 2025. During the pandemic, the National Gastroenterology Program Office has encouraged gastroenterology providers to take this opportunity to review all pending consults to determine which patients can have their procedure postponed. At the VA Puget Sound Health Care System, for example, 62 of 458 referrals (13.5%) were able to be closed without endoscopy or postponed for ≥1 year as a result of clinical review, largely owing these new guidelines.

In addition to adopting new surveillance recommendations and shifting patients from screening colonoscopy to noninvasive colorectal cancer screening approaches, future capacity for endoscopic procedures can be increased through careful review of referrals to avoid overuse of these high-demand services. Prior research has demonstrated significant overuse both in non-VA and VA settings.15, 16, 17 Many VA facilities use a “direct access” endoscopy, whereby patients are directly scheduled for endoscopy after reviewing the referral and the patient chart. During the lull in face-to-face clinical activity, many VA providers conducted telephone visits with patients awaiting endoscopy to explain the current situation. During some of these telephone visits, the endoscopist uncovered additional information either from the patient or from prior non-VA procedures that resulted in an alternative course of action that did not include endoscopy. Our anecdotal experience highlights the trade-offs inherent in open access or direct access endoscopy, where the determination of the need for endoscopy is primarily based on the information provided by the referring provider. Given the clear excess in demand for endoscopy relative to supply at this time, it is more important than ever to carefully review each referral for endoscopy to ensure that the procedure is indicated.

Our hope is that the intense focus on triage and prioritization of consults during COVID-19 will help sites optimize the timing of procedures. This would also help relieve the backlog of procedures needed to be performed more urgently. As shown in Figure 2, there has been a mild increase in procedure volume during May, suggesting some sites are slowly increasing endoscopic procedure volume based on VA guidance.5

A review of the VA Colorectal Cancer Screening and Surveillance Report demonstrates that there are approximately 405,000 veterans that appear to be due for average risk screening and an additional 107,000 patients due for surveillance and/or diagnostic colonoscopy. Over the next 3 months, an additional 168,000 veterans will become due for average risk screening and 94,000 will be due for surveillance colonoscopy. These numbers do not include those patients who develop signs or symptoms that warrant colonoscopy or who do not have surveillance recommendations currently entered into the reminder system. Thus, it is imperative that the VA optimize its supply of endoscopic resources while continuing to work to shape the demand, as discussed. As a part of that effort to shape the demand, some VA facilities are building infrastructure to support programmatic noninvasive colorectal cancer screening, such as through mailed FIT,18, 19, 20 which has been shown to be associated with significant benefits in the Kaiser Permanent system.21

In summary, the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in rapid interruption of access to endoscopic care veterans receive across the United States. The VA response was strong and swift and provided a standardized approach for rapid implementation of a process to minimize harm and the collateral damage of postponed care owing to COVID-19. The impact was almost immediate across the entire health system, reflecting the effectiveness of the process. At the same time, the VA, like all health care systems, now has future challenges and potential opportunities to navigate during this historic time for our health care system. Addressing these challenges will require a similarly decisive effort to prevent adverse outcomes for patients resulting from postponement of clinical care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Charles Demosthenes, MD (Atlanta VA), and Yiwen Yao, MS (Salt Lake City VA) for their contributions to data collection and review of the manuscript. The contents of this work do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding Supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Salt Lake City VA, San Francisco VA, VA Puget Sound Health Care System, and the Atlanta VA.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Gastroenterology at www.gastrojournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2020.07.033.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Commins J. Health Leaders; Simplify Compliance, Brentwood: TN: 2020. Surgeon General urges providers to consider stopping all elective surgeries. hospitals push back. Available at: https://www.healthleadersmedia.com/clinical-care/surgeon-general-urges-providers-consider-stopping-elective-surgeries-hospitals-push. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bezerra J., El-Serag H., Pochapin M. COVID-19 clinical insights for our community of gastroenterologists and gastroenterology care providers. 2020. https://gi.org/2020/03/15/joint-gi-society-message-on-covid-19/ Available from:

- 3.Deputy Undersecretary for Health for Operations and Management . 2020. COVID 19: guidance for elective gastroenterology and hepatology procedures. [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Department of Veterans Affairs . 2020. Guidance for COVID-19 pandemic response. [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Veterans Affairs . 2020. VHA guidance for resumption of procedures for non-urgent and elective indications. [Google Scholar]

- 6.US Department of Veterans Affairs . 2020. Veterans Health Administration moving forward guidebook: safe care is our mission. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta S., Lieberman D., Anderson J.C. Recommendations for follow-up after colonoscopy and polypectomy: consensus update by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterol. 2020;158:1131–1153.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Podboy A., Cholankeril G., Cianfichi L. Implementation and Impact of Universal Pre-procedure testing of patients for COVID-19 prior to endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2020 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.022. Jun 17 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rex D.K., Vemulapalli K.C., Lahr R.E. Endoscopy staff are concerned about acquiring COVID-19 infection when resuming elective endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2020 May 16 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.038. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stone R. 2020. Message from the VHA Executive in charge - June 3. [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Veterans Affairs . 1–18. 2020. Veterans Health Administration moving forward plan. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y.C., Fann J.C.Y., Chiang T.H. Time to colonoscopy and risk of colorectal cancer in patients with positive results from fecal immunochemical tests. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1332–1340.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corley D.A., Jensen C.D., Quinn V.P. Association between time to colonoscopy after a positive fecal test result and risk of colorectal cancer and cancer stage at diagnosis. JAMA. 2017;317:1631–1641. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rouillard S., Liu V.X., Corley D.A. COVID-19: long-term planning for procedure-based specialties during extended mitigation and suppression strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020 May 18 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.047. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubenstein J.H., Pohl H., Adams M.A. Overuse of repeat upper endoscopy in the Veterans Health Administration: a retrospective analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:1678–1685. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pohl H., Robertson D., Welch H.G. Repeated upper endoscopy in the Medicare population. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:154–160. doi: 10.7326/M13-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson M.R., Grubber J., Grambow S.C. Physician non-adherence to colonoscopy interval guidelines in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:938–951. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castañeda S.F., Bharti B., Rojas M. Outreach and inreach strategies for colorectal cancer screening among Latinos at a federally qualified health center: a randomized controlled trial, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:587–594. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issaka R.B., Somsouk M. Colorectal cancer screening and prevention in the COVID-19 era. JAMA Health Forum. Epub ahead of print. May 13, 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta S., Coronado G.D., Argenbright K. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–sponsored summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:283–298. doi: 10.3322/caac.21615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin T.R., Corley D.A., Jensen C.D. Effects of Organized Colorectal Cancer Screening on Cancer Incidence and Mortality in a Large Community-Based Population. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1383–1391.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]