Abstract

For the past three decades, the coordination-driven self-assembly of three-dimensional structures has undergone rapid progress; however, parallel efforts to create large discrete two-dimensional architectures—as opposed to polymers—have met with limited success. The synthesis of metallo-supramolecular systems with well-defined shapes and sizes in the range of 10–100 nm remains challenging. Here we report the construction of a series of giant supramolecular hexagonal grids, with diameters on the order of 20 nm and molecular weights greater than 65 kDa, through a combination of intra- and intermolecular metal-mediated self-assembly steps. The hexagonal intermediates and the resulting self-assembled grid architectures were imaged at submolecular resolution by scanning tunnelling microscopy. Characterization (including by scanning tunnelling spectroscopy) enabled the unambiguous atomic-scale determination of fourteen hexagonal grid isomers.

The spontaneous self-assembly of multiple distinct building blocks is ubiquitous in nature and underlies the biosynthesis of numerous functional proteins and protein complexes1,2.

Inspired, perhaps, by the precision of nature, in recent years supramolecular chemists have exploited the highly directional and predictable features of metal coordination to construct an impressive variety of metallo-supramolecular structures3–18. We note, however, that these bottom-up approaches have mainly given rise to either discrete assemblies smaller than 10nm (refs.8,9,19,20) or infinite coordination-based polymers21,22. Meso-sized (10–100nm) discrete architectures with specific sizes and shapes are rare13,23,24, probably due to the challenges associated with the fact that they are difficult to design and reliably synthesize, the intricate self-assembly processes required for their synthesis and difficulties in their characterization. Here we describe discrete two-dimensional (2D) ensembles in the 20-nm-size domain that have been produced by coordination-driven self-assembly.

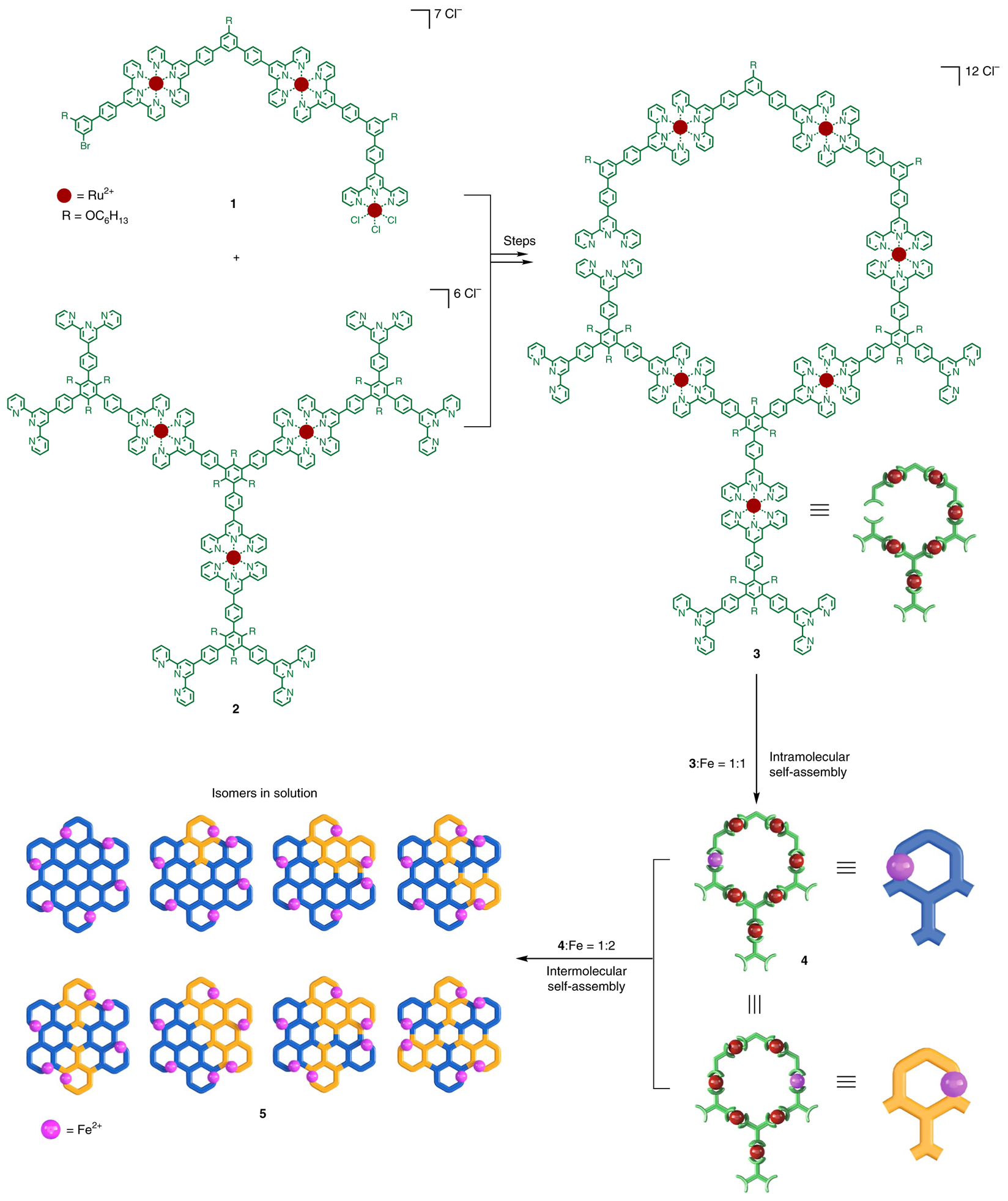

In an effort to address the challenge of constructing large synthetic systems with well-defined sizes and shapes, we have combined intra- and intermolecular self-assembly to prepare a 20-nm-wide metallo-supramolecular hexagonal grid, 5, with its eight isomers based on different substructure orientations (Fig. 1). The initial intramolecular self-assembly process, which is reminiscent of the folding process of peptides or proteins25,26, occurs on complexation with Fe2+ metal ions. Subsequent intermolecular self-assembly (also governed by complexation with Fe2+ ions) leads to the formation of discrete 2D grids. As detailed below, the underlying intra- and intermolecular self-assembly processes were studied using several characterization techniques including high-resolution, ultrahigh-vacuum, low-temperature scanning tunnelling micros-copy (UHV–LT–STM)13,27 and scanning tunnelling spectroscopy (STS). This has allowed us to characterize and identify these synthetic isomeric constructs at the atomic level.

Fig. 1 |. The synthetic strategy of ligand followed by intra- and intermolecular self-assembly of supramolecular hexagonal grids with Fe(II).

The synthesis and chemical structure of building block 3, which self-assembles into 5 via 4 through intra- and intermolecular coordination, is shown. The eight isomers resulting from the unpredictable orientation of the terpyridine-metal(II)-terpyridine (<tpy-metal(II)-tpy>) junction during the intermolecular self-assembly process are schematically shown. All of the detailed isomeric structures can be found in Supplementary Scheme 3.

Results and discussion

Synthesis of supramolecular hexagonal grid.

We first prepared the building block 3 in a stepwise manner combining a capping strategy6,13 and Suzuki coupling20,28,29 with a metal-free terpyridine (tpy) (Supplementary Figs. 4–6). It is the presence of open coordination sites in 3 that permits the Fe(ii)-mediated intra- then intermolecular self-assembly steps to occur in a programmable manner; for instance, the addition of the first equivalent of Fe(ii) favours metal-mediated intramolecular self-assembly and formation of 4 in almost quantitative yield. The relatively rigid nature of 4 then permits further self-assembly in the presence of two equivalents of Fe(ii). This was found to produce the targeted meso-scale 2D construct 5, which contains 13 hexagons as well as 18 Fe(ii) and 36 Ru(ii) metal centres and 108 counterions.

As illustrated schematically in Fig. 1, 4 can flip over during self-assembly, leading to different arrangements of the Ru(ii) and Fe(ii) centres within 5 and in turn to the unpredictable order of Ru(ii) and Fe(ii) within the outer rims. We believe that this limited programmable ambiguity is somewhat reminiscent of so-called fuzzy protein complexes in nature that are likewise characterized by a level of structural ambiguity or multiplicity30,31. In theory, eight isomers (Fig. 1) could exist in solution. As a result, we faced considerable challenges in characterization and were unable to identify each isomer in a mixture using conventional solution-phase approaches such as NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry; however, as detailed below, this system proved amenable to characterization when placed on a solid support.

Characterization in solution.

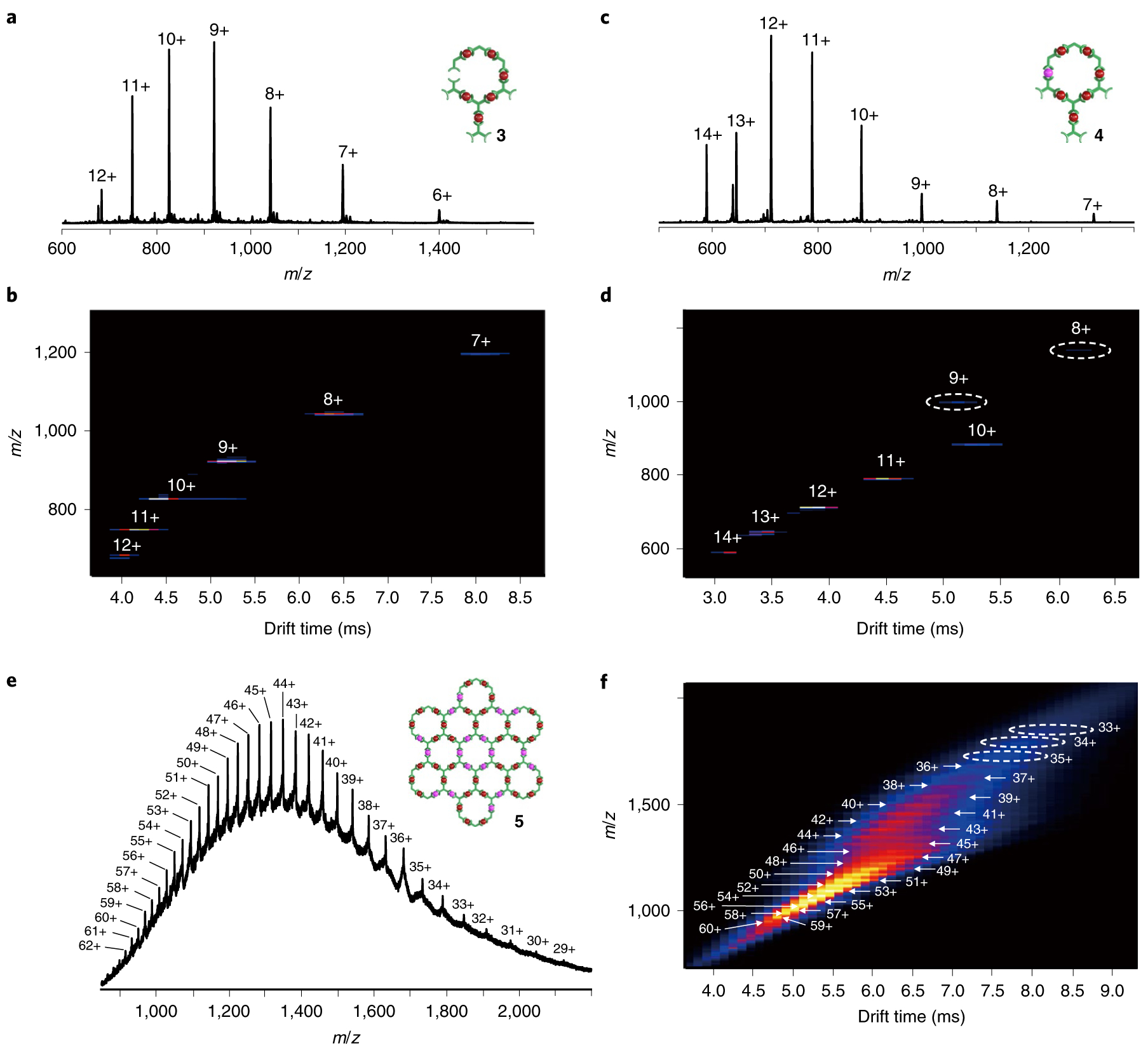

Electrospray ionization–mass spectrometry (ESI–MS), travelling wave ion mobility–mass spectrometry (TWIM–MS)32 and NMR spectroscopy were used to characterize the intra- and intermolecular and self-assembly processes leading to 5. After exposure of 3 to one equivalent of Fe(ii), complex 4 was obtained in almost quantitative yield without the need for purification. A downfield shift was seen for the H3′,5′ resonance of the terpyridine, whereas an upfield shift was seen for the H6,6″ signal in the 1H NMR spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 9). Such findings provide support for the suggestion that the first equivalent of Fe(ii) is selectively coordinated as would be expected for the formation of 4; ESI–MS and TWIM–MS spectra (Fig. 2a–d) further confirmed the molecular composition. On the basis of these combined findings, it was concluded that no other assemblies were formed at detectable levels during the intermolecular complexation process leading to 4.

Fig. 2 |. Mass spectrometry for characterization of the intra- and intermolecular self-assembly processes leading to 5.

a,b, The characterization of 3 by ESI–MS (a) and a TWIM–MS plot (m/z versus drift time) (b). c,d, The characterization of 4 by ESI–MS (c) and a TWIM–MS plot (d). e,f, The characterization of 5 by ESI–MS (e) and a TWIM–MS plot (f). In the ESI–MS spectra, the peaks with continuous charge states were achieved by losing different numbers of counterions (Cl− for 3 and PF6− for 4 and 5), which confirmed the molecular weights of 3, 4 and 5 with single chemical composition. In the TWIM–MS plots, each charge state signal showed one single band, which excluded formation of conformers during the intra- and intermolecular complexation process. The dashed ovals in d and f highlight the weak signals in TWIM–MS.

As noted above, treatment of 4 with an additional two equivalents of Fe(ii) led to grid 5. This construct, with a calculated molecular weight of 65,790 Da, is to our knowledge one of the largest 2D discrete metallo-supramolecules prepared so far13,23,24. ESI–MS analysis revealed a series of peaks from 29+ to 66+ (Fig. 2e), each of which agreed with the calculated mass-to-charge ratio for the corresponding charge state. A TWIM–MS analysis of 5 gave one set of signals, as would be expected for such a highly rigid system (Fig. 2f). The 1H NMR spectrum of 5 was characterized by the presence of broad signals (presumably the result of structural isomerism), which only permits coordination between the terpyridine and a complexed Fe(ii) ion to be inferred from the downfield shift in the H3′,5′ signals of the terpyridine relative to 4. A diffusion ordered spectroscopy33 study of 5 revealed one single band with diffusion coefficient (D) value at 7.08×10−11, corresponding to log D = −10.15 (Supplementary Figs. 71 and 72). Such a finding is consistent with the formation of a single discrete species and rules out the presence of substantial quantities of random coordinated polymers34.

Characterization on surface.

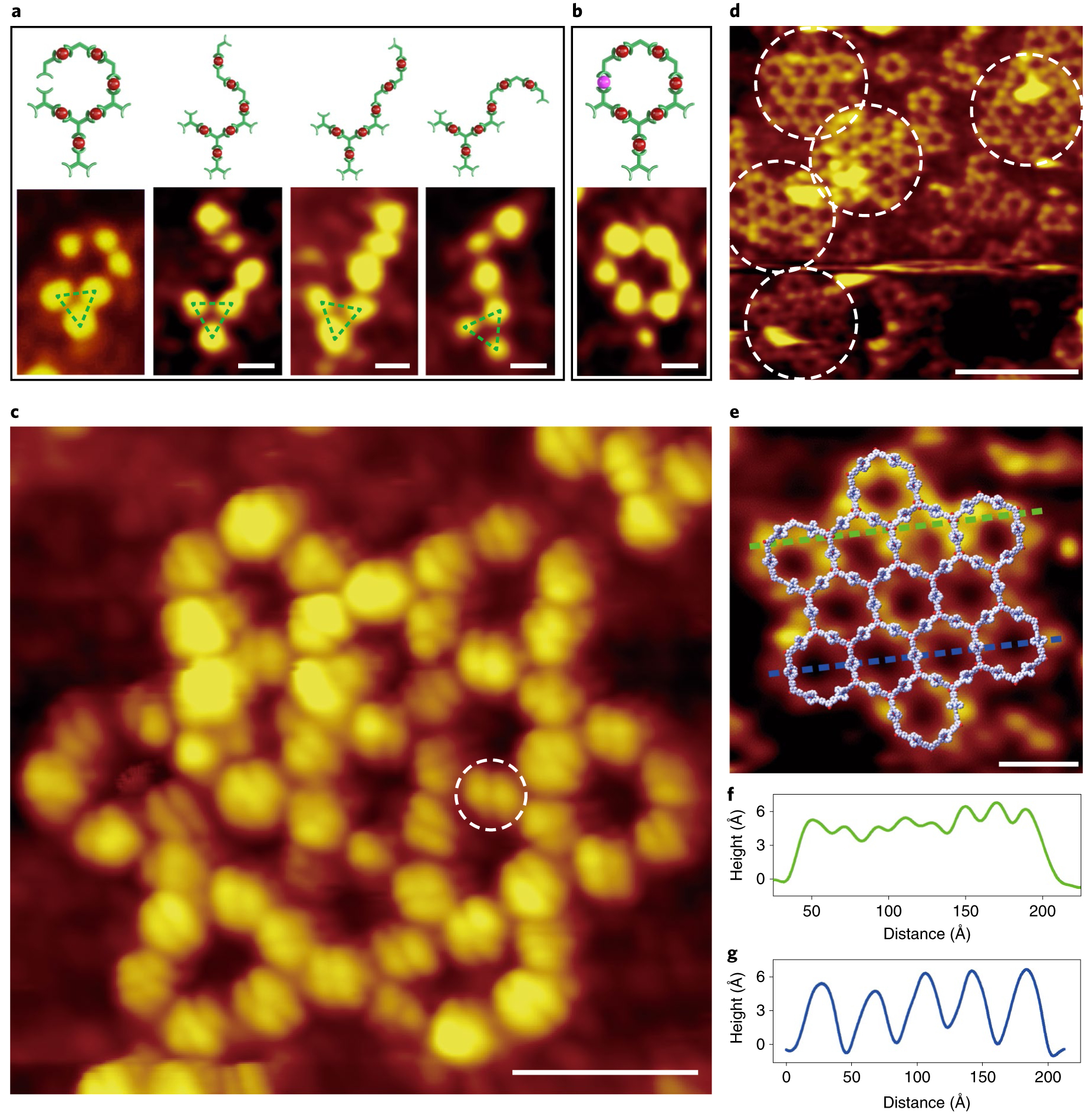

UHV–LT–STM was then used in an effort to further characterize grid 5. The goal was to obtain insights into this class of supramolecular grids on two levels: (1) imaging the constituent intra- and intermolecular self-assembled structures and (2) ascertaining the presence of isomers. It was expected that the low temperature (5K) used in these UHV–LT–STM studies would reduce thermal motion and permit high-resolution imaging. In the first study, the flexible ligand 3 was dissolved in MeCN and dropcast onto an Ag(111) surface. Due to the octahedral coordination structure and higher electron density around the metal ions, the <tpy-Ru(ii)-tpy> units gave rise to a relatively strong signal in the form of a bright lobe when compared with the organic portions (Fig. 3). It is also possible for 3 to generate conformations on the surface due to the free rotation about the C–C single bonds. These conformations were detected in STM images (Fig. 3a). In all conformers, the triangle pattern made up of three <tpy-Ru(ii)-tpy> linkages that define the branching point in 3 were easily identified. By sharp contrast to 3, only one conformation was observed for the hexagon ring 4 (Fig. 3b), which was formed by adding one equivalent of Fe(ii) into a solution of 3. In the case of 5, each <tpy-metal(ii)-tpy> was observed as a bright lobe with a pistachio-shaped morphology in the STM images (Fig. 3c–e). Importantly, 13 uniform hexagonal rings were seen as expected on the basis of our design (Fig. 3d). Moreover, the entire construct was found to have a diameter of ~20nm and a height of ~6Å (Fig. 3e–g); these values agree well with those expected on the basis of theoretical modelling (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Fig. 3 |. STM imaging of the intra- and intermolecular self-assembled structures on Ag (111) surface.

a, A schematic representation and STM images of different conformations of building block 3. Imaging parameters: bias voltage Vt = 2 V and tunnelling current It = 120 pA; scale bars = 2 nm. b, Complex 4 produced by the addition of one equivalent of Fe(II) to 3. Imaging parameters: Vt = 2 V and It = 120 pA; scale bar, 2 nm. The bright lobes represent each <tpy-metal(II)-tpy> junction. c, A magnified image of a single supramolecular hexagon grid 5 produced by adding two equivalents of Fe(II) to 4. The <tpy-metal(II)-tpy> junctions were observed as bright lobes with a pistachio-shaped morphology. Scale bar, 5 nm. d, A large area STM image of 5 showing the presence of multiple hexagon grids. Imaging parameters: Vt = 2 V and It = 110 pA; scale bar, 20 nm. e, An STM image of the supramolecular grid 5 with a molecular modelling overlay. Imaging parameters: Vt = 3 V and It = 38 pA; scale bar, 5 nm. f,g, STM line profile measurements made along the green (f) and blue (g) dashed lines shown in e revealed the height and the size of the supramolecule 5.

Isomer identification.

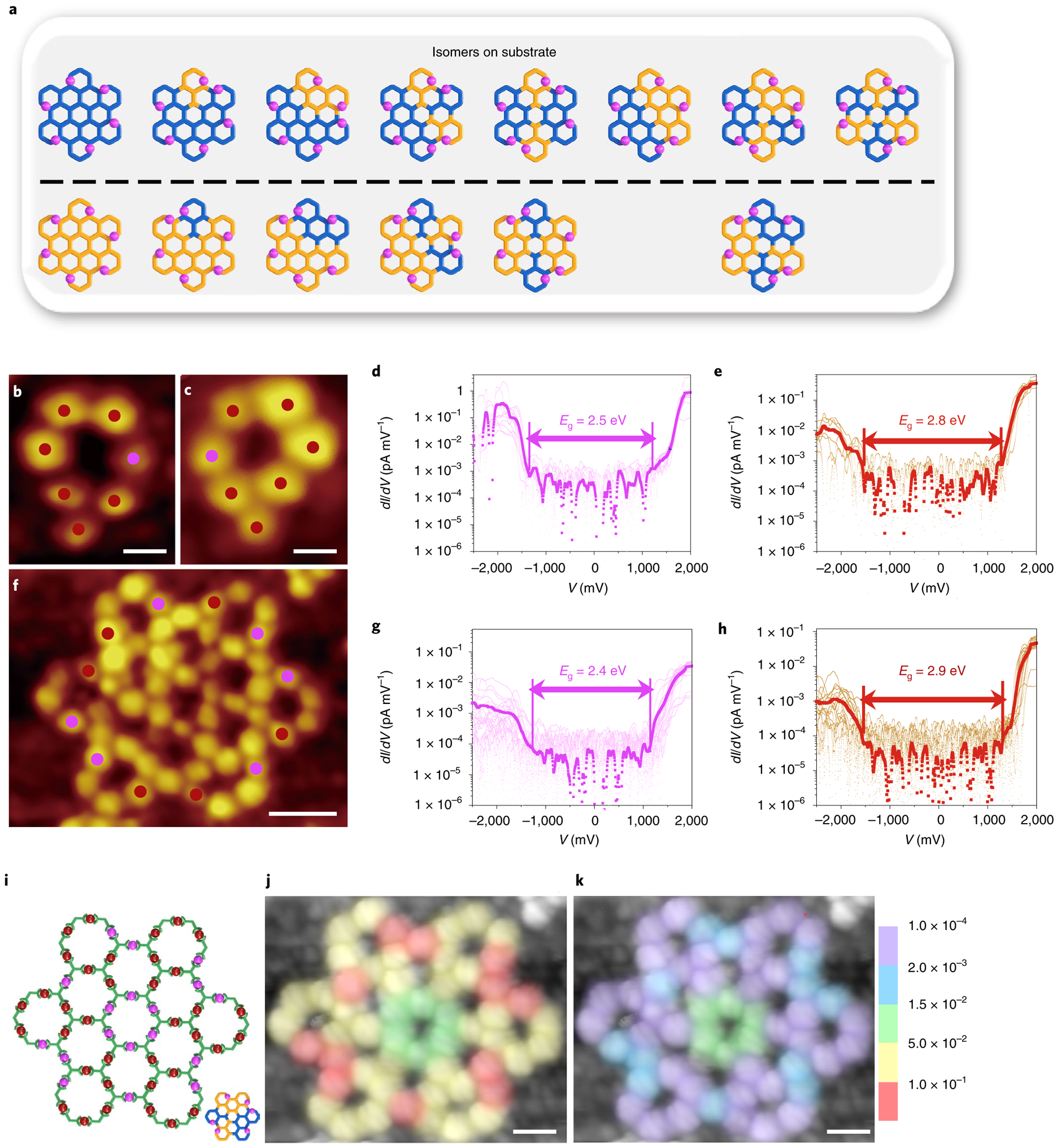

The presence of isomers with 5 was then studied by means of dI/dV-V STS35,36. This is a technique that probes the local density of states and thus may be used to identify the Fe(ii) and Ru(ii) ions, particularly in disordered domains. Tunnelling spectra were measured by positioning the STM tip above each lobe of a complex of 5 on the Ag(111) surface at a fixed height with a bias range of ±2V. The energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO can be directly obtained from dI/dV-V37. We were thus able to differentiate the Fe(ii) and Ru(ii) centres from the tunnelling spectroscopic measurements of each unit, which provide different energy gaps.

Initial studies were conducted using 4, which has only one coordinated Fe(ii) ion. Due to symmetry breaking on the surface, complex 4 forms two separate isomers on the Ag(111) surface that are characterized by different Fe(ii) locations (Fig. 4b,c). Among the seven sites, one site in each isomer (Fig. 4b,c) gives a HOMO– LUMO gap of 2.5eV (Fig. 4d) whereas the remaining six sites in each isomer provide a gap value of 2.8eV (Fig. 4e). We could thus assign the site with a smaller gap (2.5eV) as Fe(ii) and that of the larger gap (2.8eV) as the Ru(ii) site. This assignment was further confirmed by density functional theory (DFT) calculations, which revealed that the projected density of states for the Fe(ii) and Ru(ii) centres match the experimental results (Supplementary Fig. 74). The band gap for Fe(ii) is 2.4eV, whereas that for Ru(ii) is 2.8eV. In addition, a Kondo effect was also detected for several Fe(ii) centres (Supplementary Fig. 75). A Kondo effect originated from many body interactions between the magnetic moment of Fe(ii) and free electrons from the substrate38. As Fe(ii) typically has a higher magnetic moment in comparison with Ru(ii), a stronger Kondo effect is expected for the Fe(ii) centres present in 4 for further differentiation (Fig. 4b–e).

Fig. 4 |. Isomeric forms of 5 on substrate and their characterization by STS.

a, A schematic representation of the 14 possible isomers that were considered likely to be present on Ag (111) surface. b,c, UHV–LT–STM images of 4 in two different orientations on the supporting Ag(111) surface. Imaging parameters: Vt = 2 V and It = 120 pA; scale bars, 2 nm. d,e, Local conductance-voltage (dI/dV-V) tunnelling spectroscopy data for Fe(II) (purple, d) and Ru(II) (red, e) that correspond to different electronic features in 4. f, An STM image of supramolecular grid 5 that shows 12 metal ions subject to analysis. Imaging parameters: Vt = 2 V and It = 110 pA; scale bar, 5 nm. g,h, dI/dV-V tunnelling spectroscopy analyses for Fe(II) (purple, g) and Ru(II) (red, h) that correspond to the hexagonal grid shown in f. i, A model of the hexagonal grid 5 shown in f. j,k, The intensities of single-point STS data measured over each lobe in f at tunnelling electron energies of +1,650 meV (j) and −1,600 meV (k) are shown. Scale bars, 3 nm. The uncoloured original version can be found in Supplementary Fig. 73, together with colour-gradient versions of panels j and k. This analysis shows the contrast between the higher local density of states in the case of iron (shown in red) relative to ruthenium with lower density of states (yellow) at +1,650 meV (j). At −1,600 meV (k), the six Fe(II) centres within the inner ring are characterized by the highest density of states (green). A reduced density of states is seen for the six Fe(II) cations present in the intermediate region have (blue) as is true for the Ru(II) centres (purple).

Based on the above predicative studies involving 4, an effort was made to characterize the disordered domain within grid 5. There are 14 possible limiting isomers for this supramolecular construct on the surface (Fig. 4a). Being able to distinguish the Fe(ii) and Ru(ii) centres was considered to be the key in identifying these isomers. STS measurements were performed on metal sites in the disordered domain of 5; this was done by collecting multiple tunnelling spectra and then comparing the results to the averaged values obtained in 4. Among the twelve data points obtained in this way, half of them provided a band gap of 2.9eV, whereas another six sites were characterized by a lower band gap of 2.4eV. The metal centres with the higher energy gap are therefore assigned as Ru(ii) and the ones with the lower energy gap are assigned to Fe(ii). This particular complex is one specific isomer (Fig. 4i). Using a similar procedure, atomic-scale STS analyses were carried out on a total of 63 molecules, allowing us to collect data for all 14 isomers (Supplementary Figs. 76–89). A statistical analysis of the results allowed us to confirm that the probability of occurrence for each isomer matches well with what would be predicted based on theory (Supplementary Figs. 90–93). This concordance leads us to suggest that self-assembly of each intramolecular self-assembled building block constitutes an independent event and that the orientation of Fe(ii) in the intramolecular intermediate does not affect the formation of the final product.

In the above study, we observed slight differences in the energy gaps for the same type of metal ions in 4 and 5 (that is, 2.8eV versus 2.9eV and 2.5eV versus 2.4eV for Ru(ii) and Fe(ii), respectively). Such a small difference in energy is attributed to the differences in the chemical environment produced as the result of self-assembly. Moreover, a given metal cation within the hexagonal grid 5 might be characterized by different electronic density of states. Based on the chemical environment, the entire grid 5 was categorized into six domains (see Supplementary Fig. 94). Among the four domains featuring Ru(ii), the innermost one (domain 5) exhibits a distinct difference with a smaller band gap, possibly due to the close distance to the inner Fe(ii) domain 6, whereas the other three (domains 1, 2 and 4) are found to be similar (Supplementary Figs. 95 and 96). Among the three domains with Fe(ii) (domains 2, 3, 6), the innermost domain (6) is characterized by the smallest energy gap.

Colour-coded versions of the STM image shown in Fig. 4f were constructed using the averaged dI/dV curves of each coordination site to gain more detailed structural insight (Fig. 4j,k). The colour bar is defined in terms of the changes in the dI/dV signal. At +1,650meV (Fig. 4j), all <tpy-Fe(ii)-tpy> units except the innermost Fe(ii) domain exhibited higher DOS values (displayed with red). Meanwhile, all <tpy-Ru(ii)-tpy> units are characterized by lower DOS values (shown in yellow). At −1,600meV (Fig. 4k), all of the Ru(ii) domains produce a lower DOS values and are coloured purple; also, the Fe(ii) centres within the disordered domain and the middle domain give higher DOS values and are shown in blue. By contrast, the innermost Fe(ii) domains show the lowest DOS values at +1,650meV, but the highest DOS values at −1,600meV; both of which are coloured in green. The uncoloured original version can be found in Supplementary Fig. 73, together with colour-gradient versions of Fig. 4j,k.

Conclusions

Compared with the self-assembly of metallo-supramolecules characterized by a single well-defined structure, our design strategy led to the construction of many structural isomers both in solution and on a supporting metal surface. Submolecular resolution is achieved using UHV–LT–STM along with atomic-scale STS characterization. We hope that by introducing other metal ions, such as Co(ii) instead of Fe(ii), it should prove possible to produce hexagonal grids that can act as single molecule information storage devices, through, for example, manipulation of the underlying spin states39. More broadly, we believe that the present demonstration of the bottom-up preparation of 20-nm-sized molecules with precisely controlled shapes and structures will advance our understanding of the design principles governing the preparation of discrete 2D self-assembled constructs and allow access to meso-sized materials with as-yet unprecedented functions and properties.

Methods

TWIM–MS.

The TWIM–MS experiments were performed under a Waters Synapt G2 mass spectrometer under the following conditions: ESI capillary voltage, 3kV; sample cone voltage, 30V; extraction cone voltage, 3.5V; source temperature, 100°C; desolvation temperature, 100°C; cone gas flow, 10lh−1; desolvation gas flow, 700lh−1 (N2); source gas control, 0mlmin−1; trap gas control, 2mlmin−1; helium cell gas control, 100mlmin−1; ion mobility cell gas control, 30mlmin−1; sample flow rate, 5μlmin−1; ion mobility travelling wave height, 25V; and ion mobility travelling wave velocity, 1,000ms−1

Molecular modelling.

Energy minimization of the supramolecular hexagon grids was conducted with Materials Studio v.4.3, using the Anneal and Geometry Optimization tasks in the Forcite module (Accelrys Software)20. The effects of the counterions (if any) were omitted in the modelling. Geometry optimization was conducted using a universal force-field with atom-based summation and cubic spline truncation for both the electrostatic and van der Waals parameters.

DFT calculations.

Spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package code40–42 and the core electrons are described by the projected augmented-wave method43. Exchange correlation was treated in the generalized gradient approximation as implemented by Perdew et al.44 The plane wave basis was expanded to a cutoff of 600eV and the Brillouin zone was sampled using Γ point (that is, the centre of the Brillouin zone) only. Due to the giant size of Hexagonal Grid molecule, which is composed of repeated 13 hexagonal rings, calculations were performed on a single ring composed of 540 atoms.

STM.

UHV–LT–STM experiments were performed at 5K using a Createc GmbH type STM scanner. The Ag(111) sample was cleaned by repeated cycles of sputtering and annealing up to 1,000K. An electrochemically etched polycrystalline tungsten wire was used for the STM tip. The tip apex was prepared by using a controlled tip-crash procedure. The hexagon grid was deposited onto the cleaned Ag(111) surface at 25°C and then cooled to 5K inside of the STM system.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health (grant no. R01GM128037 to X.L.). Use of the Center for Nanoscale Materials, an Office of Science user facility, was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under contract no. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Support from Shanghai University is also gratefully acknowledged. T.R and A.T.N acknowledge the computing resources provided on Bebop, a high-performance computing cluster operated by the Laboratory Computing Resource Center at Argonne National Laboratory. This work was supported in part by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) under the Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI) programme. We also acknowledge partial support through University of South Florida Nexus Initiative (UNI) Award and the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (grant no. 2019A1515011358 to Z.Z.).

Footnotes

Online content

Any Nature Research reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-020-0454-z.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the manuscript or the Supplementary Information.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-020-0454-z.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.He Y et al. Hierarchical self-assembly of DNA into symmetric supramolecular polyhedra. Nature 452, 198–201 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rappas M et al. Structural insights into the activity of enhancer-binding proteins. Science 307, 1972–1975 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehn J-M From supramolecular chemistry towards constitutional dynamic chemistry and adaptive chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev 36, 151–160 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakrabarty R, Mukherjee PS & Stang PJ Supramolecular coordination: self-assembly of finite two-and three-dimensional ensembles. Chem. Rev 111, 6810–6918 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook TR & Stang PJ Recent developments in the preparation and chemistry of metallacycles and metallacages via coordination. Chem. Rev 115, 7001–7045 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty S & Newkome GR Terpyridine-based metallosupramolecular constructs: tailored monomers to precise 2D-motifs and 3D-metallocages. Chem. Soc. Rev 47, 3991–4016 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olenyuk B, Whiteford JA, Fechtenkotter A & Stang PJ Self-assembly of nanoscale cuboctahedra by coordination chemistry. Nature 398, 796–7799 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita D et al. Self-assembly of tetravalent goldberg polyhedra from 144 small components. Nature 540, 563–566 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun Q-F et al. Self-assembled M24L48 polyhedra and their sharp structural switch upon subtle ligand variation. Science 328, 1144–1147 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mal P, Breiner B, Rissanen K & Nitschke JR White phosphorus is air-stable within a self-assembled tetrahedral capsule. Science 324, 1697–1699 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rizzuto FJ & Nitschke JR Stereochemical plasticity modulates cooperative binding in a CoII12L6 cuboctahedron. Nat. Chem 9, 903–908 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chichak KS et al. Molecular borromean rings. Science 304, 1308–1312 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Newkome GR et al. Nanoassembly of a fractal polymer: a molecular “Sierpinski hexagonal gasket”. Science 312, 1782–1785 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewandowski B et al. Sequence-specific peptide synthesis by an artificial small-molecule machine. Science 339, 189–193 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcos V et al. Allosteric initiation and regulation of catalysis with a molecular knot. Science 352, 1555–1559 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danon JJ et al. Braiding a molecular knot with eight crossings. Science 355, 159–162 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pluth MD, Bergman RG & Raymond KN Acid catalysis in basic solution: a supramolecular host promotes orthoformate hydrolysis. Science 316, 85–88 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKinlay RM, Cave GWV & Atwood JL Supramolecular blueprint approach to metal-coordinated capsules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5944–5948 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mohnani S & Bonifazi D Supramolecular architectures of porphyrins on surfaces: the structural evolution from 1D to 2D to 3D to devices. Coord. Chem. Rev 254, 2342–2362 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z et al. Supersnowflakes: stepwise self-assembly and dynamic exchange of rhombus star-shaped supramolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 8174–8185 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bauer T et al. Synthesis of free-standing, monolayered organometallic sheets at the air/water interface. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50, 7879–7884 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng Z et al. Synthesis of two-dimensional analogues of copolymers by site-to-site transmetalation of organometallic monolayer sheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 6103–6110 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song B et al. Self-assembly of polycyclic supramolecules using linear metal-organic ligands. Nat. Commun 9, 4575 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H et al. Supramolecular kandinsky circles with high antibacterial activity. Nat. Commun 9, 1815 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sawada T, Yamagami M, Ohara K, Yamaguchi K & Fujita M Peptide [4] catenane by folding and assembly. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 55, 4519–4522 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamagami M, Sawada T & Fujita M Synthetic β-barrel by metal-induced folding and assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc 140, 8644–8647 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y et al. Simultaneous and coordinated rotational switching of all molecular rotors in a network. Nat. Nanotech 11, 706–712 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu X et al. Probing a hidden world of molecular self-assembly: concentration-dependent, three-dimensional supramolecular interconversions. J. Am. Chem. Soc 136, 18149–18155 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lefter C et al. Charge transport and electrical properties of spin crossover materials: towards nanoelectronic and spintronic devices. Magnetochemistry 2, 18 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu H & Fuxreiter M The structure and dynamics of higher-order assemblies: amyloids, signalosomes, and granules. Cell 165, 1055–1066 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tompa P & Fuxreiter M Fuzzy complexes: polymorphism and structural disorder in protein–protein interactions. Trends. Biochem. Sci 33, 2–8 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan Y-T et al. Self-assembly and traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometry analysis of hexacadmium macrocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc 131, 16395–16397 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stejskal EO & Tanner JE Spin diffusion measurements: spin echoes in the presence of a time‐dependent field gradient. J. Chem. Phys 42, 288–292 (1965). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giuseppone N, Schmitt J-L, Allouche L & Lehn J-M DOSY NMR experiments as a tool for the analysis of constitutional and motional dynamic processes: implementation for the driven evolution of dynamic combinatorial libraries of helical strands. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 47, 2235–2239 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasegawa Y & Avouris P Direct observation of standing wave formation at surface steps using scanning tunneling spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett 71, 1071–1074 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li G, Luican A & Andrei EY Scanning tunneling spectroscopy of graphene on graphite. Phys. Rev. Lett 102, 176804 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess HF, Robinson RB, Dynes RC, Valles JM & Waszczak JV Scanning-tunneling-microscope observation of the abrikosov flux lattice and the density of states near and inside a fluxoid. Phys. Rev. Lett 62, 214–216 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y et al. Anomalous Kondo resonance mediated by semiconducting graphene nanoribbons in a molecular heterostructure. Nat. Commun 8, 946 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park J et al. Coulomb blockade and the Kondo effect in single-atom transistors. Nature 417, 722–725 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kresse G & Hafner J Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 48, 14251–14268 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kresse G & Furthmuller J Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mat. Sci 6, 15–50 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kresse G & Furthmuller J Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anisimov VI, Aryasetiawan F & Lichtenstein AI First-principles calculations of the electronic structure and spectra of strongly correlated systems: the LDA+U method. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 9, 767–808 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perdew JP, Burke K & Ernzerhof M Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett 77, 3865–3868 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.