Abstract

In deciding when to help, individuals reason about whether prosocial acts are impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory. This research examined judgments and reasoning about prosocial actions at three to five years of age, when explicit moral judgments and reasoning are emerging. Three-to five-year-olds (N = 52) were interviewed about prosocial actions that varied in costs/benefits to agents/recipients, agent-recipient relationship, and recipient goal valence. Children were also interviewed about their own prosocial acts. Adults (N = 56) were interviewed for comparison. Children commonly judged prosocial actions as obligatory. Overall, children were more likely than adults to say that agents should help. Children’s judgments and reasoning reflected concerns with welfare as well as agent and recipient intent. The findings indicate that 3-to 5-year-olds make distinct moral judgments about prosocial actions, and that judgments and reasoning about prosocial acts subsequently undergo major developments.

Keywords: moral development, prosocial acts, reasoning, judgments, preschoolers

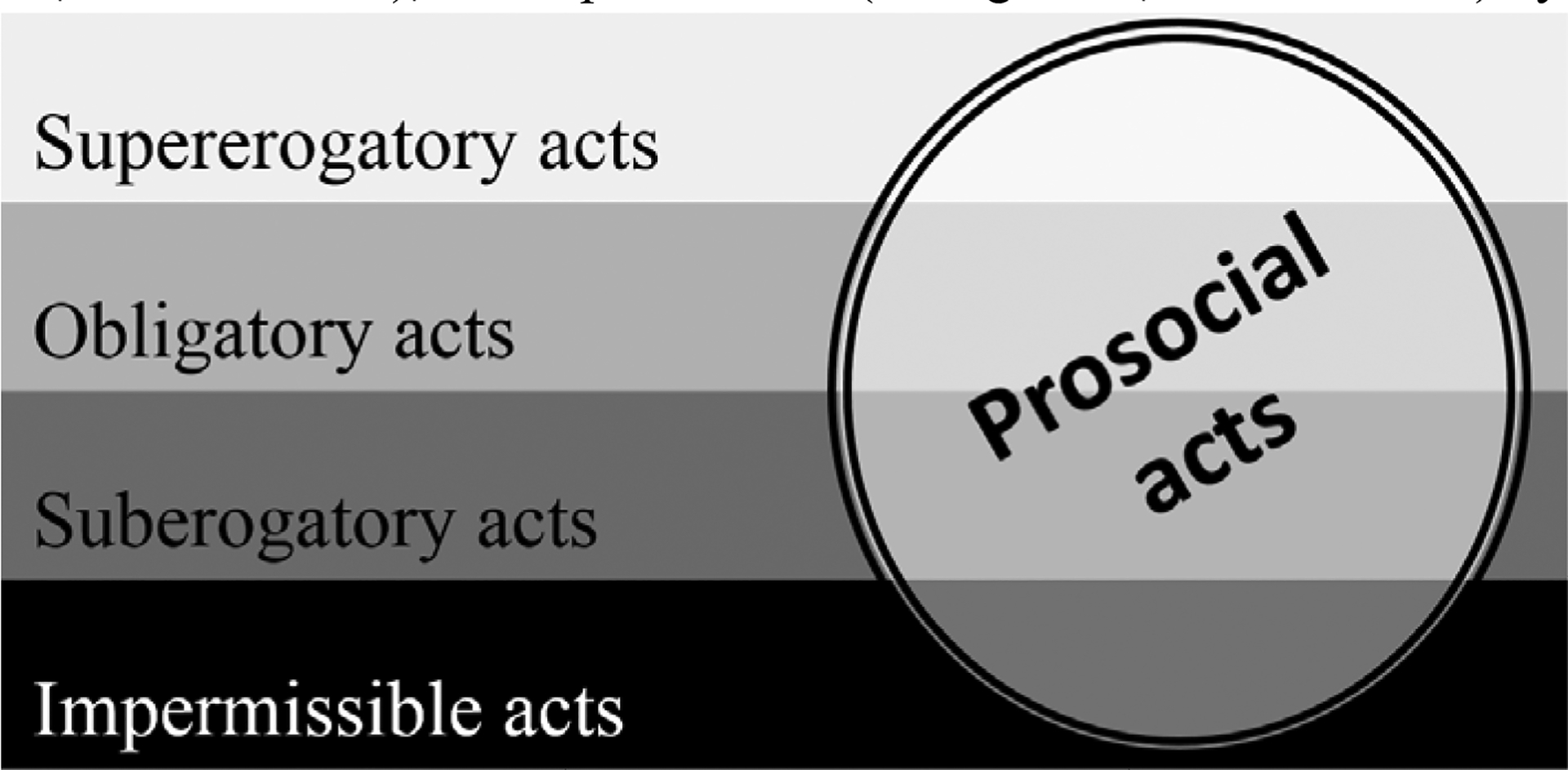

Over development, children come to weigh the pros and cons of prosocial acts—acts that promote the goals or welfare of others. In the eyes of most adults, a prosocial act can be impermissible (i.e., wrong to do, should refrain), suberogatory (okay to do, should refrain), obligatory (wrong to refrain, should do), or supererogatory (okay to refrain, should do, Figure 1; see e.g., Chisholm, 1963; McNamara, 2011; Miller et al., 1990).1 For instance, most adults deem it impermissible to help someone harm or steal from another (Killen, 2016; Miller et al., 1990; Rosen, 1984). In other contexts, helping a victim is judged as obligatory, as illustrated by public outcry against bystanders who refrain from saving a human life (Eddy, 2017; Hyman, 2005; Manning et al., 2007; Weinrib, 1980). Moral judgments about right and wrong, evident by three years of age, are integral to developed decisions about helping (Dahl, in press; Turiel, 2015). The present research examined whether 3-to 5-year-olds distinguished among impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, and supererogatory prosocial acts.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of intersection among prosocial acts and acts judged as supererogatory, obligatory, suberogatory, or impermissible. The subset of actions that are prosocial are expected to intersect with the subsets of actions that are deemed supererogatory (i.e., okay to refrain, should do), obligatory (wrong to refrain, should do), suberogatory (okay to do, should refrain), and impermissible (wrong to do, should refrain) by most or all people.

The present research builds on the proposition that children and adults construct categorical social judgments based on distinct moral, conventional, and other considerations (Dahl, Waltzer, et al., 2018; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Turiel, 2015). Several such considerations likely inform judgments about prosocial acts (Dahl, Gingo, et al., 2018; Nucci et al., 2017; Turiel, 2015). Prosocial acts can promote the welfare of the recipient, but also impose a cost on the welfare of the helpful agent (e.g., a hungry person giving away all their food to someone else); prosocial acts may be required by familial or contractual relationships (e.g., a child helping a parent); yet other prosocial acts may violate moral concerns by helping a recipient accomplish something of negative moral valence (e.g., a child helping a peer steal from another). Some complex conflicts about prosocial acts even spark debates among philosophers and legal scholars, for instance about whether refraining from a low-cost, life-saving act should be illegal (Hyman, 2005; Kamm, 2007; McIntyre, 1994; Weinrib, 1980).

The preschool years are a crucial period for the development of judgments and reasoning about prosocial acts. By age three, most children have already been helping at home for about two years (Dahl, 2015; Dahl, Waltzer, et al., 2018). Building on their prosocial tendencies, children have to decide whom and when to help based on—among other factors—judgments about prosocial acts (Dahl, in press; Dahl & Paulus, 2019; Eisenberg et al., 2016). Even though past research has demonstrated moral and social judgments and reasoning about hitting, stealing, or other social violations by age three (Dahl & Turiel, 2019; Schmidt et al., 2012; Smetana et al., 2012; Smetana, Jambon, et al., 2018), there is minimal research on young children’s judgments about prosocial acts (Dahl, Waltzer, et al., 2018; Dahl & Paulus, 2019). Young children may find it particularly challenging to form judgments about prosocial acts insofar as such judgments requires incorporation of multiple considerations about agent and recipient welfare, social relationships, and the valence of recipient goals. In early childhood, children struggle to incorporate competing considerations into a social judgment; young children often sidestep the conflict by focusing on a single consideration, such equality or welfare (Damon, 1975; Killen et al., 2018; Nucci et al., 2017).

This paper examines judgments and reasoning about hypothetical and experienced events involving prosocial acts among 3-to 5-year-olds. This research interviewed children about hypothetical prosocial events that varied in the costs and benefits to the agent and recipient, the relationship between agent and recipient, and the moral valence of the recipient goal (e.g., stealing something). To validate our assumption that adults’ judgments are sensitive to these considerations, a sample of undergraduates were interviewed about the same situations. To examine whether children applied similar judgments and reasoning to events in their everyday lives, children were also asked to judge and reason about their own experiences with helping parents, teachers, and friends (Dahl, 2017; Turiel, 2008a).

Prosocial Acts: Impermissible, Suberogatory, Obligatory, or Supererogatory

The broad category of prosociality includes actions such as aiding others in achieving practical goals, providing others with useful information, sharing valued resources, and comforting others in distress (Dahl & Paulus, 2019; Dunfield & Kuhlmeier, 2013; Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2016. For simplicity, we use the verb “help” to mean “acting prosocially.”). Different prosocial behaviors may recruit different motoric, cognitive, and emotional processes, and follow different developmental trajectories (Dunfield, 2014; Paulus, 2018). Still, by definition, all prosocial acts share a function with moral, societal, and evolutionary significance: promoting the goals and welfare of others (Hastings et al., 2015; Trivers, 1971; Turiel, 2015; Warneken, 2015). Without negating the psychological differences among prosocial actions, we here focus on types of evaluations and reasoning applicable to any prosocial act.

Scholars often note that “[a]ll human societies value prosocial actions” (Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2016, p. 3; see also Eisenberg et al., 2015; Hastings et al., 2015). The editors of a book on negative effects of altruism – a subset of prosociality – state that “[t]he benefits of altruism appear so obvious, and a high regard for altruism is so deeply ingrained in modern Western culture, that it seems almost heretical to suggest that altruism may have a dark side” (Oakley, Knafo, & McGrath, 2011, p. 3). Although this literature rarely distinguishes between obligatory and supererogatory prosociality, at least some scholars have argued that prosocial actions are by definition supererogatory (cf., Hawley, 2016): praiseworthy actions beyond the call of duty.

Despite the high scholarly regard for prosociality, people sometimes disapprove of prosocial actions (Bloom, 2016; Oakley, Knafo, Madhavan, et al., 2011; Worchel, 1984). Adolescents and adults often think it is wrong to help a thief or to save one life by sacrificing another (Dahl, Gingo, et al., 2018; Miller et al., 1990). Legal terminology even has a separate phrase, “aid and abet,” for assisting “the perpetrator of the crime” (Garner, 2011, p. 41). In 2015, a prison worker in New York received a seven-year sentence for helping two inmates escape (Morgenstein, 2015). As these examples suggest, people develop distinctions among approved and disapproved prosocial actions.

Philosophers have distinguished among impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, and supererogatory prosocial acts (Archer, 2018; Chisholm, 1963; Heyd, 2016; Kant, 1785; McNamara, 2011, 2018; Williams, 1985). In the present work, the four terms constitute an ordinal scale from most negative to most positive, but there are categorical distinctions among them. The terms are formed, and operationalized, by crossing questions about recommendations (e.g., “Should you help or refrain?”) and permissions (e.g., “Is it okay or wrong to help/refrain?” see Table 1). An act A is impermissible if you should refrain from A and it would be wrong to do A, suberogatory if you should refrain from A but it would be okay to do A, obligatory if you should do A and it would be wrong to refrain from A, and supererogatory if you should do A but also it would be okay to refrain from A (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Overview of Interview

| Initial evaluation | Should A help? | |||

| Yes | No | |||

| ↙ | ↘ | |||

| Reasoning | Why should A help? | Why should A not help? | ||

| Obligation/permission | Would it be okay if A did not help? | Would it be okay if A did help? | ||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Classification | Supererogatory | Obligatory | Suberogatory | Impermissible |

| Permission to act against rule | If there was a rule against helping, would it be okay for A to help then? | If there was a rule requiring helping, would it be okay not to help then? | ||

| Obligation to help a friend | If A and R were friends, would it be okay not to help then? | |||

Note. A = Agent; R = Recipient. Italicized words indicate participant responses. The question about obligation to help a friend was not asked for the relationship/no relationship events.

Past research suggests that these four concepts organize adults’ evaluations of prosocial acts. As noted, most adults deem it impermissible to help someone harm or steal from another (Miller et al., 1990). Less research has examined adult judgments about suberogatory acts, prosocial or otherwise. A recent study found that adults deemed some violations of social conventions to be suberogatory (Dahl & Waltzer, in press): For instance, participants said a protagonist should not be loud in a quiet restaurant, yet they said being loud would still be “okay.” In contrast, when the recipient of help does not have an immoral goal, adults frequently indicate that protagonists should help or that helping would be good (Kahn, 1992; Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990; Smetana et al., 2009). Some of these prosocial acts are deemed obligatory, especially when the recipient has a dire need and helping is not costly for the agent, or when the agent and recipient are family members or friends (Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990). Other positively evaluated prosocial actions have been viewed as supererogatory, for instance when the need of the recipient is low and helping is costly to the agent, or when the agent and recipient are strangers (Kahn, 1992; Miller et al., 1990; Smetana et al., 2009).

Moral judgments and prosocial actions both emerge during the first five years of life (Brownell, 2013; Dahl, Waltzer, et al., 2018; Dahl & Killen, 2018; Smetana, Jambon, et al., 2018; Warneken, 2015). Still, these two key elements of early moral development have largely been studied separately. Much research on early moral judgments and reasoning has focused on act of harming or stealing. Hence, as young children make decisions about prosocial actions, we do not know whether children can perceive these prosocial acts as impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory (Dahl, in press; Dahl & Paulus, 2019).

The Development of Judgments and Reasoning about Prosocial Actions

Distinctions among prosocial acts are relevant for children, not just for adults. The children’s poem Helping concludes that “some kind of help is the kind of help that helping’s all about / and some kind of help is the kind of help we can all do without” (Silverstein, 2008, p. 74). From an early age, children engage in helping that sometimes impede the goals of the recipient, for instance by throwing toys back on the floor during toy clean-up (Dahl et al., 2011; Hammond & Brownell, 2018). These events sometimes lead parents to try to prevent children from helping (Rheingold, 1982). By middle childhood, children in many communities encounter expectations that they help with chores and that it would bad not to help your family (Coppens et al., 2014). In response to social signals about their helping, children must come to form notions of whether helping is impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory.

The earliest acts of helping are evident by the first birthday, when children sometimes hand out-of-reach objects to others (Dahl, 2015; Sommerville et al., 2013; Warneken & Tomasello, 2007). During the second and third years, children become increasingly prone to assist, comfort, or share with others (Dahl, 2015; Svetlova et al., 2010; Warneken & Tomasello, 2006; Zahn-Waxler et al., 1992). At these early ages, however, children do not yet provide explicit judgments and reasoning about moral issues (Dahl & Paulus, 2019).

By age three, most children express moral judgments and reasoning about many perceived violations: They think that hitting others is impermissible because it causes harm and that stealing is impermissible because it violates property rights (Dahl, Waltzer, et al., 2018; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Tomasello, 2018). Children also say harming others would be wrong even if there were no rules against hitting, or even if the agent did not care about the victim’s welfare (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Dahl & Schmidt, 2018; Nucci & Weber, 1995; Smetana, 1985; Smetana et al., 2012). Hence, by 3-to 5 years of age, concerns with welfare and rights guide children’s judgments about permissibility.

Judging and reasoning about prosocial acts presents children with new challenges (Eisenberg et al., 1983). First, judgments that a prosocial act is impermissible requires coordination of the general valuing of prosocial acts with competing considerations about costs and benefits or the impermissibility of the recipient’s goal (e.g., stealing). Second, judgments that a prosocial act is obligatory requires children to negatively evaluate an omission (e.g., the failure to help), not a commission (e.g., an act of harm). Lastly, judging acts as supererogatory requires a nuanced distinction between good and obligatory acts; some philosophers have noted that there is no analogous distinction between bad and impermissible acts (for discussions, see Heyd, 2016; McNamara, 2011).

Only a handful of studies have investigated evaluations and reasoning about prosocial acts prior to seven years of age (see Dahl, in press; Dahl & Paulus, 2019). Initial investigations of judgments about prosocial acts relied on dilemmas, in which the needs of the agent were pitted against the needs of another person (Eisenberg et al., 1983, 1987). In these situations, helping usually required the agent to incur a substantial cost, for instance by giving up a valued resource. An early study of children’s responses to prosocial dilemmas found increases in reasoning about the recipient’s needs about prosocial acts from ages four to six (Eisenberg et al., 1983). Although this research yielded important insights, the use of dilemmas in moral development research tends to underestimate children’s capabilities (Turiel, 2008b). Moreover, this research focused on classifying children’s reasoning rather than their judgments of permissibility, obligation, and supererogation.

Recent investigations suggest that, around ages three to five, children do view some prosocial acts and agents positively (Van de Vondervoort & Hamlin, 2017; Weller & Lagattuta, 2014). These studies have shown that children tend to view helpful characters as nicer than unhelpful characters (Franchin et al., 2019; Van de Vondervoort & Hamlin, 2017). Around this age, children also endorse norms about how to distribute resources fairly (Rizzo & Killen, 2016; Smith et al., 2013; Wörle & Paulus, 2018). Rakokzy, Kaufman, and Lohse (2016) found that 3-to 5-year-olds often protested against unequal resource distributions, even when children were merely observing the distribution as third parties. However, several studies have found that children at these ages struggle to coordinate competing considerations, for instance balancing equality and equity in their judgments about fair distributions (Rizzo & Killen, 2016; Wörle & Paulus, 2018; for a discussion, see Killen et al., 2018). As noted, competing considerations about costs-benefit relations, social relationships, and the moral valence of the recipient goal are inherent to many prosocial actions.

Judgments and reasoning about impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, and supererogatory acts can inform children’s own decisions to help (Bar-Tal, 1982; Coppens et al., 2014; Dahl, in press; Eisenberg et al., 2016; Hardway & Fuligni, 2006; Hay & Cook, 2007; Recchia et al., 2015). Other things being equal, children help more often when they view helping as obligatory than when they view helping as impermissible (Bar-Tal, 1982; Martin et al., 2016; Paulus et al., 2018). Thus, studying judgments about prosocial acts will shed light on children’s motivations and decisions to help (see Discussion).

Prosocial behaviors increase in frequency and change in quality during the early years (Eisenberg et al., 2015). Separate bodies of research have examined the early development of prosocial behaviors and of moral judgments, but there is virtually no research on judgments and reasoning about impermissible and obligatory prosociality prior to seven years of age (Dahl & Paulus, 2019; Smetana, Jambon, et al., 2018; Thompson, 2012; Tomasello, 2018; Warneken, 2018). Lacking research about children’s judgments about obligatory and impermissible prosocial actions, scholars often attribute change and variability in children’s prosocial behaviors to empathic responsiveness, perspective taking, or concerns with others’ welfare (see Eisenberg et al., 2015).

Three Considerations Expected to Inform Judgments about Prosocial Acts

The present research focused on three considerations expected to inform judgments about whether prosocial acts are impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory: (1) the costs and benefits to agents and recipients, (2) the relationship between the agent and recipient, and (3) the valence of the recipient’s goal. The hypotheses, described below, were derived from past research on judgments and reasoning about prosocial actions among school-age children, adolescents, or adults (e.g. Dahl, Gingo, et al., 2018; Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990; Nucci et al., 2017; Weller & Lagattuta, 2014).

(1). Agent/recipient costs/benefits.

The relations between costs to the agent and benefits to the recipient are known to inform judgments about prosocial acts among older children. Prosocial acts that relieve a strong need for the recipient and that are not costly to the agent are more likely viewed as supererogatory or even obligatory (Kahn, 1992; Miller et al., 1990; Weller & Lagattuta, 2014). Thus, we hypothesized that 3-to 5-year-olds, and adults, would be more likely to say that the agent should help, and that it would be wrong not to help, when the prosocial act was more beneficial to the recipient and less costly to the agent. To maximize the effect of cost/benefit relations, and to reduce the number of situations presented to children, we contrasted situations involving low cost to the agent and high benefit to the recipient (low cost / high benefit events) with situations involving high cost to the agent and low benefit to the recipient (high cost / low benefit events).

(2). Agent-recipient relationships.

Some relationships entail interpersonal obligations, for instance to help others. Helping a friend or family member is judged as obligatory more often than helping a stranger (Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990). Correspondingly, we hypothesized that children and adults would be more likely to say that a child should help their parent than to say that a child should help someone else’s parent. Moreover, we expected that children would be more likely to say the agent would be obligated to help if the interactants were friends.

(3). Valence of recipient goal.

A third basis for evaluating prosocial acts is the valence of the recipient’s goal. Most children think it is generally wrong to steal or damage the property of others (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Rossano et al., 2011; Smetana et al., 2012). Older children and adults are less likely to judge helpful acts positively if the recipient is trying to engage in a moral violation, for instance stealing or harming someone (Miller et al., 1990; Turiel, 2015). In the present study, we expected that children and adults would typically say that it would be impermissible to help a child steal another child’s hat.

The Present Research

The present research examined judgments and reasoning about prosocial acts at 3 to 5 years of age, when explicit moral judgments and reasoning are emerging (Dahl & Paulus, 2019; Tomasello, 2018). To validate our assumption that the study manipulations would influence adults’ judgments, we also interviewed a sample of young adults about the same prosocial actions. For each consideration, we created a pair of situations that differed along the critical dimension. For instance, in one situation the recipient needed help stealing (retrieving someone else’s hat) and in the comparison situation the recipient needed help with a non-stealing goal (retrieving their own hat). Little research has examined young children’s judgments about prosocial actions: To reduce the concern that children would only make moral judgments about specific types of prosocial actions, situations represented a variety of prosocial actions (e.g., helping with practical goals, sharing food, or aiding someone in distress).

Structured interviews about each situation examined whether participants viewed the prosocial act as impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory. To assess these distinctions, participants were first asked whether the agent should help. If participants said the agent should not help, they were asked whether it would be okay for the agent to help; if participants said the agent should help, they were asked whether it would be okay to refrain from helping. Participant responses could then be classified as impermissible (should not help, not okay to help), suberogatory (should not help, okay to help), obligatory (should help, not okay to refrain from helping), and supererogatory (should help, okay to refrain from helping).

A second aim of the interview was to examine children’s evaluative reasoning. We expected that children’s judgments about prosocial acts would primarily be based on moral concerns with rights and welfare (Kahn, 1992; Recchia et al., 2015). However, we also expected that conventional considerations about authority commands, existing rules, and social relationships would inform children’s judgments. To address the basis for their judgments, participants were asked why the agent should or should not help, allowing us to code the content of participant reasoning. Moreover, the interview assessed whether participants’ judgments were sensitive to the presence of a rule (e.g., would it still be okay to help, even if there were a rule against helping). Lastly, the interview further probed the role of agent-recipient relationships by asking whether it would be okay to refrain from helping if the agent and recipient were friends (Killen & Turiel, 1998).

A final component of the interview explored children’s judgments and reasoning about their own acts of helping. It was expected that children would make moral judgments not only about hypothetical prosocial actions, but also about the kinds of prosocial actions they encountered in their everyday lives. Hence, we asked children to describe, judge, and reason about their own experiences with helping parents, teachers, and friends (Dahl, 2017; Turiel, 2008a).

Methods

Participants

Children were recruited from preschools in the western United States (N = 52, Mage = 4;4 [years;months], range: 3;0–5;11, 19 three-year-olds, 25 four-year-olds, 8 five-year-olds, 23 female, 29 male). This sample size was comparable to that of prior studies of preschoolers’ social judgments and reasoning (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Smetana, Ball, et al., 2018; Van de Vondervoort & Hamlin, 2017). Simulations based on expected patterns of judgments yielded statistical power of .85 for a sample size of 48. The reported race and ethnicity distribution of the sample was: 78% white non-Hispanic/Latinx, 4% Hispanic/Latinx, 2% Asian or Asian-American, 6% as other/mixed, and 10% not reported. Eight additional children were interviewed, but their data were not included due to data recording or errors, child refusal to participate, or teacher interference. Adult participants were recruited from a research participation pool at a large public university in the western United States (N = 56, Mage = 19;2, range: 18;0–22;0, 42 female, 14 male). The reported race and ethnicity distribution of the sample was: 38% Hispanic/Latinx, 36% white non-Hispanic/Latinx, 25% Asian or Asian-American, and 2% as other/mixed. Three additional adults were interviewed, but were excluded from the final sample because of interviewer error. Child interviews were conducted in preschools and adult interviews were conducted in a laboratory.

Materials and Procedures

Interviews about hypothetical events.

We created eight hypothetical stories in which an agent had the opportunity to help someone (see Appendix in the Supplementary Online Materials [SOM]). Situations were developed from a review of prior literature, a predecessor study with adults, and pilot interviews with eight preschool-age children. As mentioned, little was known about preschoolers’ judgments about prosocial acts; hence, we sought to include a broad range of prosocial events in this initial study. The interactants were described as children, except when the recipient was a parent. Two events were high-cost / low benefit events, in which the agent could help at a high cost to themselves and with limited benefit to the recipient (e.g., an agent on crutches helping another child get back on their feet after tripping). Two events were low-cost / high benefit events in which the agent could help at a low cost to themselves and with great benefit for the recipient (e.g., giving away food when agent was not hungry and the recipient is very hungry). One event was a relationship event, in which the agent had a particular relationship to the recipient and the task that could warrant helping (i.e., a child helping her mom cleaning the child’s room). This was contrasted with a no relationship event, in which there was no such relationship between the agent and the recipient. The stealing event involved helping the recipient steal the hat of another person. The no stealing event involved helping the recipient retrieving their own hat. Each story was accompanied by a picture depicting the agent and the recipient.

To reduce the duration of the child interviews, we limited the number of hypothetical events per participant to four. Since we were the most confident that children would distinguish the high-cost / low-benefit events from the low-cost / high-benefit events, each participant was interviewed about one high-cost / low-benefit event and one low-cost / high-benefit event. In addition, each participant was interviewed about either one relationship event or one no relationship event, and either one stealing event or one no stealing event. The order of presentation was counterbalanced using a Latin square design.

For each event, children were first asked a comprehension question (e.g., “Whose hat was it?” in the stealing/no stealing events). As shown in Table 1, the interview procedure was devised to determine whether participants viewed the helping as impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory. All participants were asked whether the participant should help. Subsequent questions depended on whether the participant had said that the agent should help. Participants who said the agent should help were asked whether it would be okay for the agent not to help, to assess whether they viewed helping as obligatory. They were then asked whether it would still be okay to help if there were a rule against helping, to assess whether their evaluations were sensitive to conventional considerations. Participants who said the agent should not help were asked whether it would be okay for the agent to help, and whether it would be okay not to help even if there were a rule saying you have to help. Lastly, all participants were asked whether it would be okay to refrain from helping if the agent and recipient were friends, to assess whether participants were more likely to view helping as obligatory in friendships. (The friendship question was not asked about the relationship and no relationship events, in which the recipient was the mother of one of the interactants.)

Interviews about own experiences with helping.

After interviews about hypothetical events, child participants were asked about their own experiences with helping. They were asked about helping in three contexts: helping parents at home, helping teachers at school, and helping friends. For each context, the child was asked whether they liked to help and what kinds of things they helped with. For the first example they mentioned in each context, children were then asked whether all kids should help with this, why or why not, and whether it would be okay if other children did not help in this way. We did not assess impermissibility of helping for children’s own experiences, as we expected that almost no children would say that others should not help the way they helped (see Results). Data on adults’ descriptions, judgments, and reasoning about their own experiences with helping will be reported in a separate manuscript.

Coding

Recordings of the children’s responses were video or audio recorded, and then transcribed and coded by trained research assistants. For the purposes of graphing, participants’ judgments about prosocial acts were classified as supererogatory (should help, okay to refrain), obligatory (should help, not okay to refrain), suberogatory (should not help, okay to help), and impermissible (should not help, not okay to help. See Table 1). Justifications were coded using the coding scheme shown in Table 2, which was developed from prior research on children’s social reasoning and well as a review of a subset of the data (Dahl & Kim, 2014; Kahn, 1992; Killen & Turiel, 1998). Children’s examples of helping at home, in school, or friends were coded as either chores (e.g., “helping water plants”), clean up (e.g., “put toys away”), kindness (e.g., “hug mom”), kitchen (e.g., “help make food”), play (e.g., “do puzzles with them”), other (e.g., “feeding my fish”), or none (e.g., “I don’t know”). For assessment of reliability, a second coder coded 20% of the data. Agreement, as measured by Cohen’s κ, was .80 for justification and 1.00 for helping categories.

Table 2.

Coding Scheme for Justifications

| Code | Definition | Justifications |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | References to what a persons’ rights and responsibilities for taking care of themselves and their own things | “She should clean her own room” |

| Evaluation | Valenced statement about action or outcome | “It’s kind” “That’s a nice thing to do” |

| Material order | Reference to consequences of act for physical order/disorder | “The room was messy” |

| Others’ interest/welfare | Reference to what benefits the recipient or others | “She’s hungry” “She needs help” |

| Agent interest/welfare | Reference to what benefits the agent | “She needs to eat the food herself” “If he doesn’t help he’ll get in trouble” |

| Social organization | References to rules, roles, or authority | “You’re supposed to help your parents” |

| Other | Statement not fitting into above categories | “It’s cleaning time” |

| None | No justification provided | “I don’t know” |

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Generalized Linear Mixed Models, which can model within-subjects design, non-normal distributions of dependent variables, and non-linear relations (Hox, 2010). Models had logistic link function and binomial error distribution since the dependent variables of interest were all dichotomous: should judgments (yes/no), okay to help (yes/no), not okay to help (yes/no), and presence of each justification type (present/absent). Models included random intercepts for participants and fixed effects of situation type, child age, and gender. Except when noted, two-way interactions were not statistically significant, ps > .05. Hypotheses were first tested using likelihood ratio tests. If the overall situation effect were significant, we carried out the three planned comparisons using McNemar tests (for high-cost / low-benefit vs. low-cost high-benefit) or Fisher tests (for relationship vs. no relationship, stealing vs. no stealing).

Results

For clarity, only the theoretically most important analyses are reported here. For data on children’s judgments about hypothetical situations, the analyses are organized around the following questions: (A) Did children think the protagonist should help? Among children who said the protagonist should help: (B1) Why should the protagonist help? (B2) Was helping supererogatory or obligatory (i.e., was it okay or not okay to refrain from helping)? Among those who said the protagonist should not help: (C1) Why should the protagonist not help? (C2) Was helping suberogatory or impermissible (i.e., was it okay or not okay to help)? Analyses of children’s responses regarding rules and helping a friend, and complete analyses of justification data, are provided in the SOM. For adults, only analyses on judgments about whether the protagonist should help are reported below; the remaining analyses of adult data are reported in the SOM.

Reporting on children’s judgments and reasoning about their own helping events mirrored reporting on children’s judgments and reasoning about hypothetical events, addressing the following questions: (A) Did children think another child should help in this situation? (B1) If yes, why should the child help? (B2) Was helping supererogatory or obligatory? (C1) If no, why should the child not help? Finally, we calculated relations between children’s judgments about hypothetical helping events and children’s judgments about their own helping events.

Child Responses to Hypothetical Events

Children correctly answered the comprehension question in 98% of cases. Data for scenarios in which children answered the comprehension question incorrectly were removed before analysis.

(A). Should agent help?

In 85% of cases, children said the agent should help. Judgments varied significantly by situation type, D(5) = 21.45, p < .001. Two of the planned comparisons were significant: Children were more likely to say that the agent should help in the low-cost / high-benefit situations (92%) than in the high-cost / low-benefit situations (75%), McNemar test: p = .035. Moreover, children were more likely to say that the agent should help in the no stealing (96%) than in the stealing (64%) condition, Fisher test: p = .007. The difference between the relationship (96%) and no relationship (89%) conditions was not significant, p = .61. Girls were more likely to say that the agent should help (92%) than were boys (79%), D(1) = 6.15, p = .013. There was no significant effect of child age, D(1) = 0.06, p = .80.

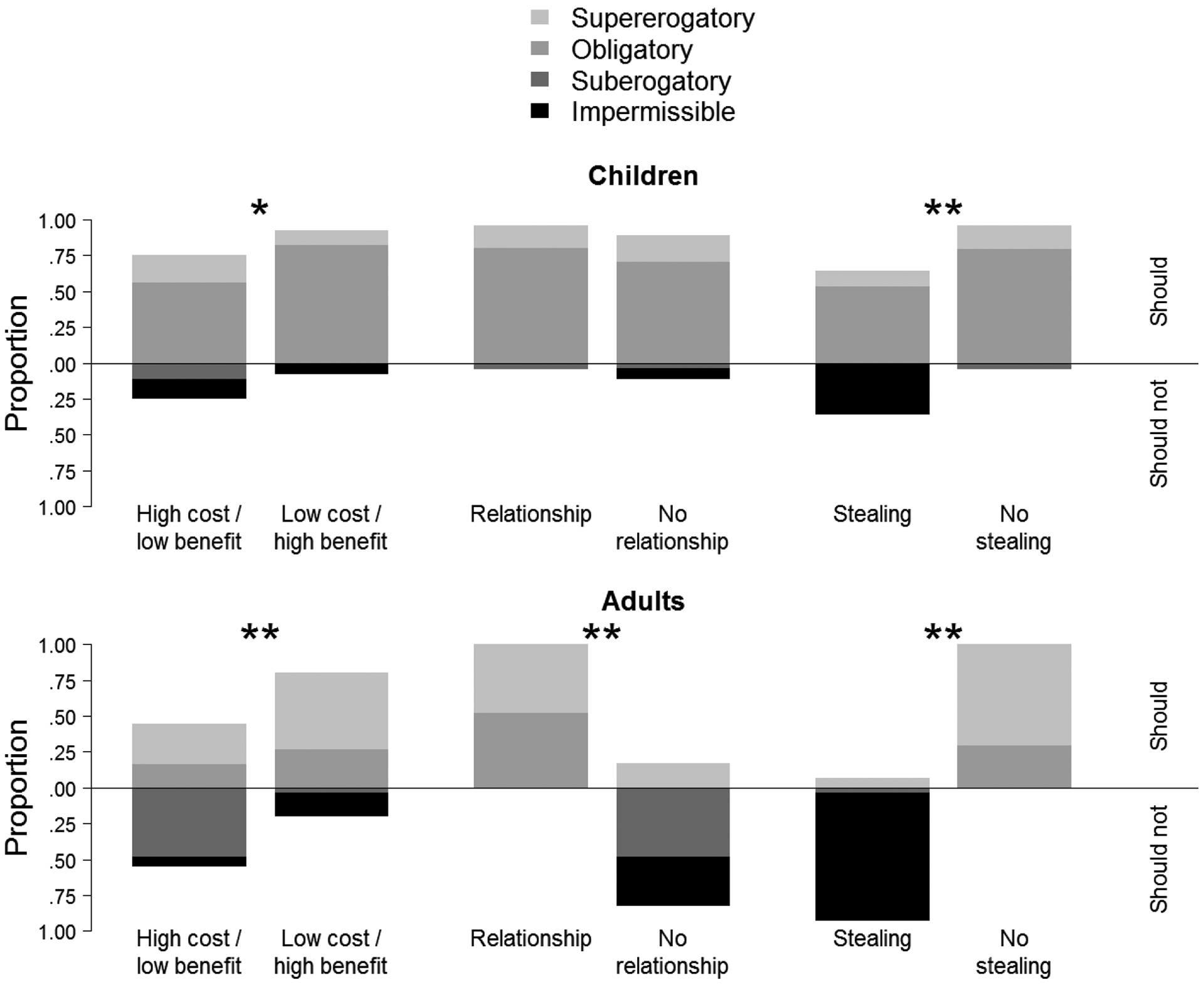

Figure 2 combines the judgment data to show the proportions of children and adults who indicated whether helping was impermissible (should not help and not okay to help), suberogatory (should not help but okay to help), obligatory (should help and not okay to refrain), or supererogatory (should help but okay to refrain).

Figure 2.

Children’s and adults’ judgments about helping. The bars show proportions of participants indicating that helping was impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, or supererogatory. (The same data are represented in Table S1.) The horizontal line separates judgments that the agent should help from judgments that the agent should not help. The horizontal axis indicates proportions of all participants responding to a given situation. Pairwise comparisons for propensities to say that the agent should help: *p <.01, **p <.001

Judgments and reasoning when children thought the agent should help (176 cases).

(B1). Why should the agent help?

Next, we analyzed children’s justifications for why the agent should help (Table 3). The most common justifications were references to others’ interest/welfare (43% of cases), evaluations (27%), and agent’s interest/welfare (11%). Children provided no codeable justifications in 15% of cases. The remaining justifications were used in less than 10% of cases, and where not analyzed (material order: 6%, rule/role: 1%, autonomy: 0%).

Table 3.

Justifications for Judgments that Agent Should Help

| Justification category | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Autonomy | Evaluation | Material | Others’ interest | Agent interest | Organization | Other | None |

| Children: Hypothetical events | ||||||||

| High cost / low benefit | .00 | .28 | .00 | .38 | .08 | .03 | .00 | .23 |

| Low cost / high benefit | .00 | .23 | .00 | .62 | .06 | .00 | .00 | .11 |

| Relationship | .00 | .29 | .13 | .21 | .25 | .04 | .04 | .08 |

| No relationship | .00 | .29 | .29 | .21 | .04 | .00 | .00 | .17 |

| Stealing | .00 | .17 | .00 | .56 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .33 |

| No stealing | .00 | .35 | .00 | .48 | .26 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Adults: Hypothetical events | ||||||||

| High cost / low benefit | .04 | .25 | .00 | .67 | .63 | .04 | .00 | .00 |

| Low cost / high benefit | .02 | .23 | .00 | .72 | .56 | .02 | .00 | .00 |

| Relationship | .48 | .04 | .04 | .16 | .68 | .04 | .00 | .00 |

| No relationship | .20 | .40 | .00 | .20 | .20 | .20 | .00 | .00 |

| Stealing | .00 | .00 | .00 | .50 | .50 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| No stealing | .00 | .24 | .00 | .52 | .84 | .00 | .00 | .00 |

| Children: Own events | ||||||||

| Home | .00 | .32 | .23 | .27 | .07 | .00 | .00 | .11 |

| Friends | .00 | .48 | .05 | .10 | .07 | .07 | .02 | .17 |

| School | .00 | .35 | .12 | .21 | .07 | .00 | .07 | .12 |

Note. Cells show proportions of participants saying the agent should act who used each justification category.

The use of evaluations (e.g., “it’s nice to help”) did not vary significantly by situation type, D(5) = 3.25, p = .66, child age, D(1) = 0.96, p = .33, or gender, D(1) = 0.59, p = .44.

References to others’ interests/needs (e.g., “She’s hungry”) varied significantly by situation type, D(5) = 20.59, p < .001. These justifications were used in 62% of low-cost / high benefit situations, 38% of high-cost / low-benefit situations, 56% of stealing situations, 48% of no stealing situations, and 21% in relationship and no relationship situations (none of the planned comparisons were significant, ps ≥ .064). There were no significant effects of child age, D(1) = 0.66, p = .42, or gender, D(1) = .078, p = .78.

The frequency of agent interest/welfare (e.g., “if he doesn’t help he’ll get in trouble”) justifications varied by situation type, D(5) = 14.52, p = .013. These justifications were more common in the no stealing situation (26%) than in the stealing situation (0%), p = .027. The difference was not significant between the relationship and no relationship events, p = .097, or between high-cost / low benefit and low-cost / high-benefit events, p = 1.00.

Lastly, younger children were more likely than older children to provide no justification, D(1) = 9.49, p = .002. There was also a significant effect of situation type, D(5) = 12.58, p= .028. Children were less likely to provide justifications in the stealing situation (67% provided justification) than in the no stealing situation (100% provided justification), p = .004. Differences were not significant between relationship (92%) and no relationship (83%) situations, p = .67, and between high-cost / low-benefit (78%) and low-cost / high-benefit (89%) situations, p = .34.

(B2). Obligatory vs. supererogatory helping.

When children said the agent should help, they judged helping as obligatory (not okay to refrain) in 82% cases and supererogatory in 18% of cases. There were no significant effects of situation type, age, or gender on judgments about obligation, ps > .30.

Judgments and reasoning when children thought the agent should not help (52 cases).

Because judgments that the agent should not help were so rare, no statistical hypothesis tests were performed. Below, we report descriptive statistics for these cases.

(C1). Why should the agent not help?

When asked why the agent should not help, children referenced others’ interest/welfare (34% of cases), agent interest/welfare (25%), evaluations (19%), or autonomy (6%), and provided no justification in 19% of cases.

(C2). Suberogatory vs. impermissible helping.

When children said the agent should not help, they judged helping as suberogatory in 32% of cases and impermissible in 68% of cases.

Adult Responses to Hypothetical Events

(A). Should agent help?

Adults said the agent should help in 58% of situations (Figure 2). The propensity to say the agent should help depended on situation type, D(5) = 123.46, p < .001. Adults were more likely to say that the agent should help in the low-cost / high-benefit (81%) than high-cost / low-benefit (45%) situations, p < .001, no stealing (100%) than stealing (7%) situation, p < .001, and the relationship (100%) than no relationship (18%) situation, p < .001. There was no significant effect of gender, D(1) = 1.65, p = .20. For analyses of adults’ reasoning and judgments about impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, and supererogatory helping, see SOM.

Comparison of child and adult judgments.

To compare children’s and adults’ judgments about prosocial acts, we fitted a model with data from both samples. This model revealed a significant interaction between study and situation type, D(5) = 16.89, p = .005. Children were significantly more likely than adults to say that the agent should help in the high-cost / low-benefit situation (children: 75%, adults: 45%), Fisher’s exact test: p = .002, stealing (children: 65%, adults: 7%), p < .001, and no relationship (children: 89%, adults: 17%), p < .001, situations. The differences for the low-cost, no stealing, and relationship situations were not significant, ps > .09.

Children’s Own Helping Events

Complete analyses of children’s reports and judgments about their own helping situations are reported in the SOM.

Most children could provide an example of helping at home (88%), in school (73%), or with friends (79%). The situation types were distributed as follows: clean-up (45% of examples), play(14%), kitchen (14%), other (13%), kindness (9%), and chores (6%).

Judgments and reasoning about own helping.

(A). Should others help?

In 83% of cases, children said someone else should also help in the activity they described, even if they did not want to. There were no significant effects of context, D(1) = 0.46, p = .80, age, D(1) = 0.11, p = .74, or gender, D(1) = 1.43, p = .23.

(B1). Why should others help (129 cases)?

The most common justification categories were evaluations (38% of cases), others’ interest/welfare (19%), and material order (13%) justifications. In addition, 13% provided no codeable justification. Agent interest/welfare (7%), other (3%), rule/role (2%), and autonomy (0%) were used too rarely to be further analyzed (Table 3).

(B2). Obligatory vs. supererogatory helping.

In 79% of cases, children indicated that helping was obligatory. There were no significant effects of context, D(2) = 0.34, p = .84, age, D(1) = 1.22, p = .27, or gender, D(1) = 1.76, p = .18. (As expected, very few children said that others should not help the way they help, so impermissibility of helping was not assessed.)

(C1). Why should others not help (27 cases)?

When children said the agent should not help, they provided no justification (22%), or used agent interest/welfare (19%), other (4%), or others’ interest/welfare (4%) justifications.

Relation between judgments about obligation in hypothetical and own examples.

To assess whether children’s judgments about their own helping events related to judgments about hypothetical helping events related to, we correlated judgments about whether it would be okay not to help (i.e., whether helping was obligatory). For own events, we averaged across the home, school, and friends events (1 = not okay not to help, 0 = okay not to help). For hypothetical judgments, we averaged across the high-cost and low-cost events, since both children received one of each (for other helping events, only half of the children received each story).

There was a significant positive correlation between obligation judgments in hypothetical events (high-and low-cost) and own events, Spearman r = .41, p = .003. That is, children who were more likely to say it would be wrong not to help in their own examples of helping were more likely to say it would be wrong not to help in the hypothetical high-and low-cost events.

Discussion

Decisions about when to help rest on distinctions among impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, and supererogatory prosocial acts. Developing these distinctions involves reasoning about welfare and rights in the contexts of costs and benefits to the agent and recipient, social relationships, and the moral valence of the recipient’s goal (e.g., Dahl, Gingo, et al., 2018; Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990; Nucci et al., 2017; Turiel, 2015; Weller & Lagattuta, 2014). The present research investigated whether children make these distinctions by three to five years of age, when explicit moral judgments are emerging and children sometimes struggle to incorporate multiple considerations into social judgments (Dahl & Paulus, 2019; Killen et al., 2018; Tomasello, 2018).

Across a variety of situations, children commonly judged prosocial acts as obligatory. For both hypothetical situations and their own helping events, children said that that it would be wrong to refrain from helping in most cases. Children rarely deemed helping as supererogatory (agent should help, but it would be okay not to help). In contrast, adults viewed helping as obligatory in less than half of cases, and frequently viewed helping as supererogatory in response to the low-cost / high-benefit, relationship, and no stealing events.

Children were surprisingly likely to say the agent should help, and that helping was obligatory, even in the stealing scenario: About half of children said that it would be wrong not to help the recipient by retrieving a hat that belonged to another child. There was no indication that the finding simply reflected a lack of scenario comprehension, for instance about who owned the hat. In response to the comprehension questions (e.g., “Whose hat is this?”), virtually all children responded correctly; data for children who responded incorrectly (2%) were removed before analysis. A more likely explanation for why children so often judged helping as obligatory—more often than adults—is that young children struggle to balance competing consideration when they form social judgments (Killen et al., in press; Nucci et al., 2017; Turiel, 2008b). When young children encounter a situation that pertains to multiple principles (e.g., helping is good vs. stealing is bad), they sometimes focus on one principle (e.g., recipient welfare) and disregard others (e.g., agent welfare or property rights). In a study with even older children, Nucci and colleagues (2017) found that 8-year-olds were more likely than 11-and 14-year-olds to view helping as obligatory. Thus, children’s difficulties with coordinating competing considerations about right and wrong are evident during preschool age and beyond (Killen et al., 2018; Kohlberg, 1971; Turiel, 2008b).

Nevertheless, children’s judgments and reasoning about hypothetical and actual prosocial acts revealed several socio-moral considerations (Dahl, Gingo, et al., 2018; Nucci et al., 2017; Turiel, 2015). First, children were responsive to the welfare of the agent and recipient. Children were significantly more likely to say the agent should help when the cost to the agent was low and benefit to recipient was high, than when cost to the agent was high and benefit to the recipient was low (Nucci et al., 2017; Weller & Lagattuta, 2014). In explaining why an agent should help, children frequently referenced the welfare of the recipient or, less commonly, the agent (Killen & Turiel, 1998; Recchia et al., 2015). Second, children’s judgments were sensitive to the perceived valence of the agent and recipient intentions. Children were less likely to say that the agent should help the recipient steal a hat (vs. retrieving recipient’s own hat), and frequently explained why the agent should help using moral evaluative concepts such as “nice” or “kind.” They also invoked non-social, pragmatic considerations about how helping would create material order (Dahl & Kim, 2014). In contrast, the presence of rules did not appear to be a primary source of children’s judgments about prosocial acts. Children rarely referenced the existence of rules when explaining why the agent should help, and typically though helping would be okay even if there were a rule against helping. This suggests that young children tend to think about prosocial acts in moral, rather than conventional, terms (Turiel, 2015).

In contrast, relationship considerations had limited impact on children’s judgments about prosocial acts. Children typically said that the agent was obligated to clean up, irrespective of whether the agent was helping their own parent or another child’s parent. If the agent and recipient were friends, children were significantly more likely to say that the agent was obligated to help in the high cost / low benefit situations, but not in the other situations (the latter null findings may have been due to ceiling effects). The limited effects of relationship on children’s judgments were surprising, both given the present findings with adults and past findings with older children (Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990).

One limitation of the present study was the number of situations examined. A larger study investigating children’s judgments about a wider variety of hypothetical situations would be important for documenting additional contributors to children’s judgments about impermissible, suberogatory, obligatory, and supererogatory helping. For instance, it would be useful to manipulate agent cost and recipient benefit separately. Next, research is needed on a broader range of roles and relationships, as different roles and relationships may entail different obligations. For instance, if a child is assigned to help clean up after a mealtime in preschool, this role may entail specific obligations about cleaning up after mealtime, but not about cleaning up after playtime. Lastly, it is possible that children would have been even less likely to judge helping as obligatory in even simpler situations involving recipient goals with negative valence.

A second set of questions pertain to cultural variability. By middle childhood, if not before, there are substantial differences in children’s contributions to household work (Alcalá et al., 2014; Coppens et al., 2014; Rogoff et al., 1993; Telzer & Fuligni, 2009). Correspondingly, children and adults from different communities sometimes perceive different obligations to help (Miller et al., 1990). In the United States, Latinx youth from working-class communities often express responsibilities to provide financial or practical help to their families not expressed by their European American, middle-class peers (Covarrubias et al., in press; Hardway & Fuligni, 2006). The developmental sources of cultural variability judgments and decisions about prosocial actions toward family members constitute an exciting topic for future research.

An overarching question is how children gradually form more nuanced judgments and reasoning about prosocial acts. Children’s judgments and reasoning differed in many respects from adults’ judgments and reasoning, and also from the patterns of judgments and reasoning observed in past studies with older children (Kahn, 1992; Killen & Turiel, 1998; Miller et al., 1990). In particular, how do children come to view many acts of helping as supererogatory: good actions that are not obligatory (Kahn, 1992; Kant, 1785; Williams, 1985)? And how do children come to coordinate distinct considerations about helping situations so as to think it is wrong to help a recipient steal from or harm others? These developments are likely guided by advances in children’s socio-cognitive abilities as well as social experiences with helping and being helped (Dahl, Waltzer, et al., 2018; Hastings et al., 2015; Recchia et al., 2015).

It will also be important to investigate relations between children’s own prosocial acts and children’s judgments about when individuals should help, when helping is obligatory, and when helping is wrong. Such relations between judgments and actions have been hypothesized by many authors (Blake et al., 2014; Dahl & Paulus, 2019; Hay & Cook, 2007; Paulus et al., 2018; Turiel, 2015). The present study provided preliminary evidence that children’s judgments about hypothetical events relate to their judgments about their own prosocial acts. Research is now needed to examine whether young children are more likely to help when they view helping as obligatory. As part of this research, it will be crucial to examine how children’s evaluative judgments and reasoning align with or conflict with other motives (Ball et al., 2016; Bloom, 2016). In recent years, researchers have made theoretical and methodological progress on studying children’s many different motivations to help, including from empathy and intrinsic desires to see others’ helped, concerns with punishments and rewards, and social affiliation (for overviews, see e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2016; Hepach et al., 2012; Paulus, 2014; Warneken, 2015). When children face an opportunity to help, they may experience little empathy yet perceive an obligation to help; or they may perceive a reward to helping someone steal, yet deem helping to be wrong. How children navigate such dilemmas of prosociality, integrating judgments with other motives, will be a key topic for future inquiry.

This research evidences that young children can judge prosocial acts as obligatory, impermissible, and – less commonly – supererogatory or suberogatory. Children’s judgments were primarily based on moral concerns with welfare and the intent of the persons involved. Comparisons with responses of adults in the present study and older children in past research indicate that judgments about prosocial acts undergo major transformations beyond five years of age. Most strikingly, in many situations children were more likely than adults to view the prosocial acts as obligatory. By contrast, adult participants made clear and hypothesized distinctions among different prosocial acts based on considerations about welfare, relationships, and valence of recipient goal. The subsequent transformations in judgments and reasoning about prosocial acts, implied by the present data, likely contribute to the development of individual and cultural differences in when and how to help.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Judgments about prosocial acts guide decisions about when to help

Such judgments incorporate several moral and non-moral considerations

Three-to five-year-olds and adults were interviewed about prosocial actions

Children judged prosocial acts as obligatory more often than adults

Children’s judgments were sensitive to the welfare and intent of interactants

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R03HD087590) to AD. We thank members of the Early Social Interaction Laboratory at the University of California, Santa Cruz, for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Philosophers have debated which terms to use for these four categories of acts, and how to define them. For lack of corresponding terms in everyday English, some philosophers have adopted the technical terms supererogation and suberogation. In this paper, our use of these two terms is based on, but not identical to, how the terms are used in philosophy (for discussions, see Heyd, 2016; McNamara, 2011).

Contributor Information

Audun Dahl, Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Cruz;.

Rebekkah L. Gross, Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Cruz;

Catherine Siefert, Department of Psychology, University of California, Santa Cruz..

References

- Alcalá L, Rogoff B, Mejía-Arauz R, Coppens AD, & Dexter AL (2014). Children’s initiative in contributions to family work in indigenous-heritage and cosmopolitan communities in Mexico. Human Development, 57, 96–115. 10.1159/000356763 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Archer A (2018). Supererogation. Philosophy Compass, 13(3), e12476 10.1111/phc3.12476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ball CL, Smetana JG, & Sturge-Apple ML (2016). Following my head and my heart: Integrating preschoolers’ empathy, theory of mind, and moral judgments. Child Development. 10.1111/cdev.12605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Tal D (1982). Sequential development of helping behavior: A cognitive-learning approach. Developmental Review, 2(2), 101–124. 10.1016/0273-2297(82)90006-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K, & Warneken F (2014). The developmental origins of fairness: The knowledge–behavior gap. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(11), 559–561. 10.1016/j.tics.2014.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom P (2016). Against empathy: The case for rational compassion. Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell CA (2013). Early development of prosocial behavior: Current perspectives. Infancy, 18(1), 1–9. 10.1111/infa.12004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm RM (1963). Supererogation and offence: A conceptual scheme for ethics. Ratio, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Coppens AD, Alcalá L, Mejía-Arauz R, & Rogoff B (2014). Children’s initiative in family household work in Mexico. Human Development, 57(2–3), 116–130. 10.1159/000356768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Covarrubias R, Valle I, Laiduc G, & Azmitia M (in press). “You never become fully independent”: Family roles and independence in first-generation college students. Journal of Adolescent Research, 074355841878840. 10.1177/0743558418788402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A (in press). When and how to help? Early developments in acts and evaluations of helping In Jensen LA (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of moral development: An interdisciplinary perspective. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A (2015). The developing social context of infant helping in two U.S. samples. Child Development, 86(4), 1080–1093. 10.1111/cdev.12361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A (2017). Ecological commitments: Why developmental science needs naturalistic methods. Child Development Perspectives. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Campos JJ, & Witherington DC (2011). Emotional action and communication in early moral development. Emotion Review, 3(2), 147–157. 10.1177/1754073910387948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Gingo M, Uttich K, & Turiel E (2018). Moral reasoning about human welfare in adolescents and adults: Judging conflicts involving sacrificing and saving lives. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, Serial No. 330, 83(3), 1–109. 10.1111/mono.12374 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, & Killen M (2018). A developmental perspective on the origins of morality in infancy and early childhood. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, & Kim L (2014). Why is it bad to make a mess? Preschoolers’ conceptions of pragmatic norms. Cognitive Development, 32, 12–22. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, & Paulus M (2019). From interest to obligation: The gradual development of human altruism. Child Development Perspectives, 13, 10–14. 10.1111/cdep.12298 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, & Schmidt MFH (2018). Preschoolers, but not adults, treat instrumental norms as categorical imperatives. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 165, 85–100. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, & Turiel E (2019). Using naturalistic recordings to study children’s social perceptions and evaluations. Developmental Psychology, 55, 1453–1460. 10.1037/dev0000735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl A, Waltzer TL, & Gross RL (2018). Helping, hitting, and developing: Toward a constructivist-interactionist account of early morality In Helwig CC (Ed.), New perspectives on moral development Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damon W (1975). Early conceptions of positive justice as related to the development of logical operations. Child Development, 46(2), 301–312. 10.2307/1128122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield KA (2014). A construct divided: Prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield KA, & Kuhlmeier VA (2013). Classifying prosocial behavior: Children’s responses to instrumental need, emotional distress, and material desire. Child Development, 84(5), 1766–1776. 10.1111/cdev.12075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy M (2017, December 22). German Court Fines 3 for Failing to Help Ailing Retiree in Bank. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/19/world/europe/germany-bank-pensioner.html [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Lennon R, & Roth K (1983). Prosocial development: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 19(6), 846–855. 10.1037/0012-1649.19.6.846 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Shell R, Pasternack J, Lennon R, Beller R, & Mathy RM (1987). Prosocial development in middle childhood: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 23(5), 712. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Spinrad TL, & Knafo-Noam A (2015). Prosocial development In Lamb ME& Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 3, pp. 610–656). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, VanSchyndel SK, & Spinrad TL (2016). Prosocial motivation: Inferences from an opaque body of work. Child Development, 87(6), 1668–1678. 10.1111/cdev.12638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchin L, Savazzi F, Neira-Gutierrez IC, & Surian L (2019). Toddlers map the word ‘good’ to helping agents, but not to fair distributors. Journal of Child Language, 46(1), 98–110. 10.1017/S0305000918000351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner BA (2011). Garner’s dictionary of legal usage (3rd ed). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SI, & Brownell CA (2018). Happily unhelpful: Infants’ everyday helping and its connections to early prosocial development. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardway C, & Fuligni AJ (2006). Dimensions of family connectedness among adolescents with Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 42(6), 1246–1258. http://dx.doi.org.oca.ucsc.edu/10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings PD, Miller JG, & Troxel NR (2015). Making good: The socialization of children’s prosocial development. (pp. 637–660). Guilford Press; (New York, NY, US: ). [Google Scholar]

- Hawley PH (2016). Evolution, prosocial behavior, and altruism: A roadmap for understanding where the proximate meets the ultimate In Padilla-Walker LM& Carlo G (Eds.), Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach (pp. 43–69). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, & Cook KV (2007). The transformation of prosocial behavior from infancy to childhood In C. A. Brownell& Kopp CB(Eds.), Socioemotional Development in the Toddler Years (pp. 100–131). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hepach R, Vaish A, & Tomasello M (2012). Young children are intrinsically motivated to see others helped. Psychological Science, 23(9), 967–972. 10.1177/0956797612440571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyd D (2016). Supererogation In Zalta Edward N.(Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2016/entries/supererogation/ [Google Scholar]

- Hox J (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman DA (2005). Rescue without law: An empirical perspective on the duty to rescue. Texas Law Review, 84, 653–738. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn PH (1992). Children’s obligatory and discretionary moral judgments. Child Development, 63(2), 416–430. 10.2307/1131489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamm FM (2007). Intricate ethics: Rights, responsibilities, and permissible harm. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kant I (1785). Groundwork of the metaphysics of morals (H. J. Paton, Trans.) Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M (2016). Morality: Cooperation is fundamental but it is not enough to ensure the fair treatment of others. Human Development, 59(5), 324–337. 10.1159/000454897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Elenbaas L, & Rizzo MT (in press). Morality: Children challenge unfair treatment of others. Human Development. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Elenbaas L, & Rizzo MT (2018). Young children’s ability to recognize and challenge unfair treatment of others in group contexts. Human Development, 61(4–5), 281–296. 10.1159/000492804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, & Smetana JG (2015). Origins and development of morality In Lamb M(Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (7th ed, Vol. 3, pp. 701–749). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, & Turiel E (1998). Adolescents’ and young adults’ evaluations of helping and sacrificing for others. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 8(3), 355–375. 10.1207/s15327795jra0803_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L (1971). From is to ought: How to commit the naturalistic fallacy and get away with it in the study of moral development In Mischel T (Ed.), Psychology and genetic epistemology (pp. 151–235). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Manning R, Levine M, & Collins A (2007). The Kitty Genovese murder and the social psychology of helping: The parable of the 38 witnesses. American Psychologist, 62(6), 555–562. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.6.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin A, Lin K, & Olson KR (2016). What you want versus what’s good for you: Paternalistic motivation in children’s helping behavior. Child Development, 87(6), 1739–1746. 10.1111/cdev.12637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre A (1994). Guilty bystanders? On the legitimacy of duty to rescue statutes. Philosophy & Public Affairs, 23(2), 157–191. 10.1111/j.1088-4963.1994.tb00009.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P (2011). Supererogation, inside and out: Toward an adequate scheme for common sense morality In Timmons M(Ed.), Oxford studies in normative ethics: Vol. Volume 1 (pp. 202–235). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McNamara P (2018). Deontic logic In Zalta EN (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab; https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/logic-deontic/ [Google Scholar]

- Miller JG, Bersoff DM, & Harwood RL (1990). Perceptions of social responsibilities in India and in the United States: Moral imperatives or personal decisions? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(1), 33–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstein M (2015, September 28). Joyce Mitchell sentenced for helping in prison break. CNN; https://www.cnn.com/2015/09/28/us/ny-prison-break/index.html [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, Turiel E, & Roded AD (2017). Continuities and discontinuities in the development of moral judgments. Human Development, 60, 279–341. 10.1159/000484067 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nucci LP, & Weber EK (1995). Social interactions in the home and the development of young children’s conceptions of the personal. Child Development, 66(5), 1438–1452. 10.2307/1131656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley B., Knafo A, Madhavan G, & Wilson DS (Eds.). (2011). Pathological altruism. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oakley B, Knafo A, & McGrath M (2011). Pathological altruism—An introduction In Oakley B, Knafo A, Madhavan G, & Wilson DS(Eds.), Pathological altruism (pp. 3–9). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, & Carlo G (Eds.). (2016). The study of prosocial behavior: Past, present, and future In Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M (2014). The emergence of prosocial behavior: Why do infants and toddlers help, comfort, and share? Child Development Perspectives, 8(2), 77–81. 10.1111/cdep.12066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M (2018). The multidimensional nature of early prosocial behavior: A motivational perspective. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 111–116. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M, Nöth A, & Wörle M (2018). Preschoolers’ resource allocations align with their normative judgments. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 175, 117–126. 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakoczy H, Kaufmann M, & Lohse K (2016). Young children understand the normative force of standards of equal resource distribution. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 150, 396–403. 10.1016/j.jecp.2016.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchia HE, Wainryb C, Bourne S, & Pasupathi M (2015). Children’s and adolescents’ accounts of helping and hurting others: Lessons about the development of moral agency. Child Development, 86, 864–876. 10.1111/cdev.12349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rheingold HL (1982). Little children’s participation in the work of adults, a nascent prosocial behavior. Child Development, 53(1), 114–125. 10.2307/1129643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, & Killen M (2016). Children’s understanding of equity in the context of inequality. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 34(4), 569–581. 10.1111/bjdp.12150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff B, Mistry J, Göncü A, Mosier C, & Chavajay P (1993). Guided participation in cultural activity by toddlers and caregivers. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 58(8), i–179. 10.2307/1166109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen S (1984). Some paradoxical status implications of helping and being helped In Development and Maintenance of Prosocial Behavior (pp. 359–377). Springer, Boston, MA: 10.1007/978-1-4613-2645-8_22 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rossano F, Rakoczy H, & Tomasello M (2011). Young children’s understanding of violations of property rights. Cognition, 121(2), 219–227. 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MFH, Rakoczy H, & Tomasello M (2012). Young children enforce social norms selectively depending on the violator’s group affiliation. Cognition, 124(3), 325–333. 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein S (2008). In Thomas M(Ed.), Free to Be… You and Me (p. 74). Running Press Book Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG (1985). Preschool children’s conceptions of transgressions: Effects of varying moral and conventional domain-related attributes. Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 18–29. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Ball CL, Jambon M, & Yoo HN (2018). Are young children’s preferences and evaluations of moral and conventional transgressors associated with domain distinctions in judgments? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 173, 284–303. 10.1016/j.jecp.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Jambon M, & Ball CL (2018). Normative changes and individual differences in early moral judgments: A constructivist developmental perspective. Human Development, 61(4–5), 264–280. 10.1159/000492803 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Rote WM, Jambon M, Tasopoulos-Chan M, Villalobos M, & Comer J (2012). Developmental changes and individual differences in young children’s moral judgments. Child Development, 83, 683–696. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Tasopoulos-Chan M, Gettman DC, Villalobos M, Campione-Barr N, & Metzger A (2009). Adolescents’ and parents’ evaluations of helping versus fulfilling personal desires in family situations. Child Development, 80(1), 280–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CE, Blake PR, & Harris PL (2013). I should but i won’t: Why young children endorse norms of fair sharing but do not follow them. PLoS ONE, 8(3), e59510 10.1371/journal.pone.0059510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommerville JA, Schmidt MFH, Yun J, & Burns M (2013). The development of fairness expectations and prosocial behavior in the second year of life. Infancy, 18(1), 40–66. 10.1111/j.1532-7078.2012.00129.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlova M, Nichols SR, & Brownell CA (2010). Toddlers’ prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Development, 81(6), 1814–1827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telzer EH, & Fuligni AJ (2009). A longitudinal daily diary study of family assistance and academic achievement among adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(4), 560–571. 10.1007/s10964-008-9391-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA (2012). Whither the preconventional child? Toward a life-span moral development theory. Child Development Perspectives, 423–429. 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00245.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello M (2018). The normative turn in early moral development. Human Development, 61, 248–263. [Google Scholar]

- Trivers RL (1971). The evolution of reciprocal altruism. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 46(1), 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (2008a). Thought about actions in social domains: Morality, social conventions, and social interactions. Cognitive Development, 23(1), 136–154. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2007.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (2008b). The development of children’s orientations toward moral, social, and personal orders: More than a sequence in development. Human Development, 51(1), 21–39. 10.1159/000113154 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E (2015). Morality and prosocial judgments and behavior In Schroeder DA & Graziano WG (Eds.), The oxford handbook of prosocial behavior (pp. 137–152). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vondervoort JW, & Hamlin JK (2017). Preschoolers’ social and moral judgments of third-party helpers and hinderers align with infants’ social evaluations. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 164, 136–151. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F (2015). Precocious prosociality: Why do young children help? Child Development Perspectives, 9(1), 1–6. 10.1111/cdep.12101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F (2018). How children solve the two challenges of cooperation. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 205–229. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, & Tomasello M (2006). Altruistic helping in human infants and young chimpanzees. Science, 311(5765), 1301–1303. 10.1126/science.1121448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, & Tomasello M (2007). Helping and cooperation at 14 months of age. Infancy, 11(3), 271–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrib EJ (1980). The case for a duty to rescue. The Yale Law Journal, 90(2), 247–293. 10.2307/795987 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weller D, & Lagattuta KH (2014). Children’s judgments about prosocial decisions and emotions: Gender of the helper and recipient matters. Child Development, 253–268. 10.1111/cdev.12238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BAO (1985). Ethics and the limits of philosophy. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worchel S (1984). The darker side of helping: The social dynamics of helping and cooperation In Staub E, Bar-Tal D, Karylowski J, & Reykowski J(Eds.), Development and maintenance of prosocial behavior (pp. 379–395). Plenum Press; http://link.springer.com.oca.ucsc.edu/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4613-2645-8_22 [Google Scholar]

- Wörle M, & Paulus M (2018). Normative expectations about fairness: The development of a charity norm in preschoolers. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 165, 66–84. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn-Waxler C, Radke-Yarrow M, Wagner E, & Chapman M (1992). Development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 28(1), 126–136. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data