Abstract

Objective

The influx of management ideas into healthcare has triggered considerable debate about if and how managerial and medical logics can coexist. Recent reviews suggest that clinician involvement in hospital management can lead to superior performance. We, therefore, sought to systematically explore conditions that can either facilitate or impede the influence of medical leadership on organisational performance.

Design

Systematic review using thematic synthesis guided by the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the synthesis of Qualitative research statement.

Data sources

We searched PubMed, Web of Science and PsycINFO from 1 January 2006 to 21 January 2020.

Eligibility criteria

We included peer-reviewed, empirical, English language articles and literature reviews that focused on physicians in the leadership and management of healthcare.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction and thematic synthesis followed an inductive approach. The results sections of the included studies were subjected to line-by-line coding to identify relevant meaning units. These were organised into descriptive themes and further synthesised into analytic themes presented as a model.

Results

The search yielded 2176 publications, of which 73 were included. The descriptive themes illustrated a movement from 1. medical protectionism to management through medicine; 2. command and control to participatory leadership practices; and 3. organisational practices that form either incidental or willing leaders. Based on the synthesis, the authors propose a model that describes a virtuous cycle of management through medicine or a vicious cycle of medical protectionism.

Conclusions

This review helps individuals, organisations, educators and trainers better understand how medical leadership can be both a boon and a barrier to organisational performance. In contrast to the conventional view of conflicting logics, medical leadership would benefit from a more integrative model of management and medicine. Nurturing medical engagement requires participatory leadership enabled through long-term investments at the individual, organisational and system levels.

Keywords: human resource management, organisational development, quality in health care, qualitative research, health services administration and management, medical education and training

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Previous literature reviews have established a correlation between physicians in leadership roles and organisational performance, this study seeks to explore what contributes to that link.

The review expands on the typically quantitative focus of systematic reviews by providing a thematic synthesis of 63 empirical studies and 10 literature reviews.

The synthesis depicts a virtuous cycle of management through medicine and a vicious cycle of medical protectionism.

This review is limited by the quality and heterogeneity of the included studies.

While plausible correlations between conditions and performance outcomes are explored, to establish causality requires study designs that determine the strength of the relationships.

Introduction

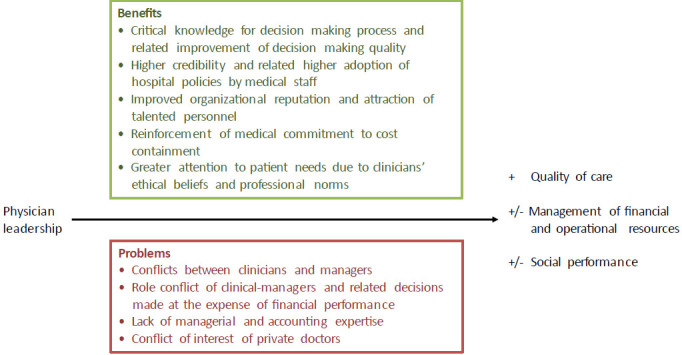

Organisational research has established a link between leadership practices and performance.1 As healthcare searches for its success formula, the impact of medical leadership on performance has become an increasingly relevant research objective. The two most recent systematic reviews on the subject suggest that clinician involvement in hospital leadership can be linked to superior performance.2 3 The inclusion of clinical leaders (primarily physicians) in senior management roles has a positive impact on care quality, management of financial and operational resources, and social performance, although a few studies showed a negative impact on the latter two.2 Additional reviews have found effects on staff satisfaction, retention, performance and burn-out4–6; psychological safety, respect and shared goals7; approval and support of political reforms8; and the adoption of information technology.9

While the reviews describe the challenge to discern why medical leadership makes a difference, Sarto and Veronesi,2 hypothesise about possible mediating mechanisms (figure 1).

Figure 1.

An explanatory model of factors that mediate the positive and negative effects of physician leadership (adapted from Sarto and Veronesi 2016).2

The core explanation proffered is centred on the individual’s credibility and competence generated by a medical degree.2 However, two observations can be made, both of which warrant further qualitative exploration. The first is that the mediating mechanisms are drawn from authors’ discussions of their quantitative results rather than research designed to specifically explore the mechanisms behind the connections. The second is that mediating mechanisms exist within a context,10 that is, there are conditions that influence to what extent medical competence and credibility can benefit organisational performance. The aim of this study is, therefore, to systematically explore the conditions that can either facilitate or impede the influence of medical leadership on organisational performance.

Methods

Review protocol

This systematic literature review is a thematic synthesis of empirical studies and literature reviews. Thematic synthesis was chosen in order to expand the traditionally quantitative focus of systematic reviews with a method that accommodates a diversity of study designs, provides policy-makers and practitioners more nuanced evidence for a complex question,11 and enables the development of insights beyond those of the original studies through an higher-order thematic structure.11 12 Given its qualitative nature, it was guided by the ENhancing Transparency in REporting the synthesis of Qualitative research statement (online supplementary appendix 1).13

bmjopen-2019-035542supp001.pdf (63KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Search strategy

The strategy was developed with assistance from a professional research librarian. We conducted a comprehensive search for scientific articles published between 1 January 2006 and 21 January 2020. We limited the search timeline to capture contemporary evidence in the light of recently established correlations between medical leadership and performance.2 We defined this as the last decade of publications. As the study originally commenced in 2016, we updated the search on 12 August 2018 and on the 21 January 2020. Boolean searches were performed in Medline/PubMed, Web of Science and PsycINFO. As the focus was on physicians, other healthcare databases such as CINAHL were excluded. To identify a wide range of studies, all possible truncated combinations of keywords and MeSH terms such as ‘clinical/medical/physician/doctor’, ‘management/leadership’, ‘organisation and management’, ‘physician executive’, ‘performance’, and ‘quality of healthcare’ were used (online supplementary appendix 2). The search was complemented with additional articles from the reference lists of the articles selected for full-text review.

bmjopen-2019-035542supp002.pdf (34.2KB, pdf)

Study selection

Aggregated search results were imported to the Mendeley reference management system where duplicates were removed. Remaining records were subjected to three rounds of screening. Inclusion criteria were that articles were peer-reviewed, empirical studies or literature reviews, and in the English language, published between January 2006 and January 2020, and which focused on physicians in the leadership and management of healthcare. We included literature reviews to capture patterns across a wide span of studies, that is, we did not use these to assess the relative importance of individual factors, but rather to identify relevant themes in the literature.

Exclusion criteria were publication prior to 2006, non-English language, not empirical or literature reviews, non-peer-reviewed, did not include physicians as study participants, and were reports on care and treatment planning for specific medical conditions. These inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied when the first author screened all titles and key words, and then the remaining abstracts. Then, all authors screened the records eligible for full-text review and applied further exclusion criteria: full text not available; purely quantitative reports on organisational performance outcomes; studies on attributes and competencies or leadership development evaluations; or do not address physicians in the leadership and management of healthcare (ie, not about their role in quality improvement, coordination of care, resource management, team leadership, change management, policy reform or descriptions of their individual experiences in such roles). Any discrepancies regarding inclusion were resolved through consensus. All included studies were then subjected to a critical appraisal performed by the first author (online supplementary appendix 3). Qualitative studies were assessed using the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research.14 For literature reviews, a 14-item checklist was developed informed by Smith et al15 and Shea et al.16 Mixed-methods and quantitative studies were subjected to a Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool.17 The appraisals primarily assessed the quality of reporting and no articles were excluded based on the appraisal.18

bmjopen-2019-035542supp003.pdf (165.1KB, pdf)

Data extraction and analysis

Data on general characteristics included type of study design, country of origin, setting and study participants. Data extraction and analysis followed an inductive approach. The results sections were read line-by-line to identify meaning units describing the conditions (ie, situations, settings, circumstances, behaviours, contextual factors, etc) that influenced medical leadership and organisational performance. The first author summarised these as codes, which were then organised into descriptive themes by all authors.12 Data extraction and analysis was performed in NVivo qualitative data analysis software; QSR International. V.10, 2012.

Given the interpretative nature of thematic synthesis, its primary output is a high-order theoretical structure.11 Therefore, based on descriptive themes, the authors developed a preliminary model (analytical themes) to depict conditions that facilitate or impede the impact of medical leadership.12 The model was presented and refined after discussions with practising clinicians and managers in our graduate and continuing professional development courses and at conferences in Sweden and Europe.

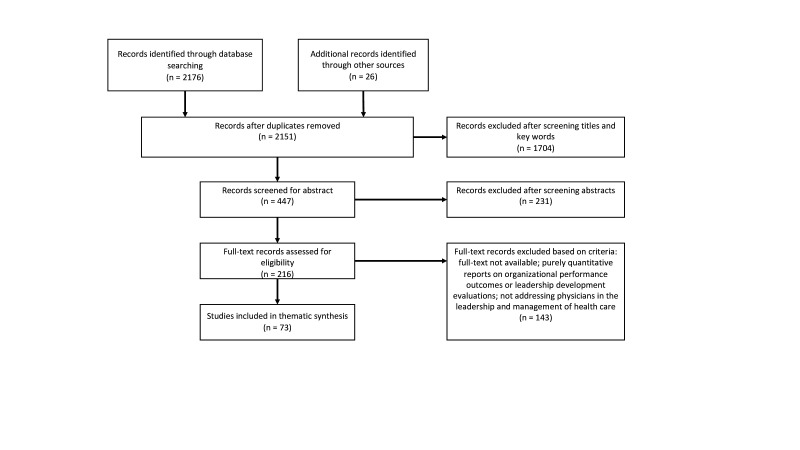

Results

The search identified 2176 records (PubMed 723, Web of Science 1119 and PsycINFO 353). After removing duplicates and adding 26 records identified from reference lists, the tally was 2151 records. Titles and key words were screened which yielded 447 records. After abstracts were screened, 216 articles remained. After a full-text screening, 73 articles were included in the thematic synthesis (figure 2). Of these, 63 were empirical articles (qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods designs) and 10 literature reviews.

Figure 2.

Study selection flow chart.

General characteristics

Most studies were conducted in the UK (n=17) and the USA (n=16), in-hospital settings (n=45), and focused on senior managers (n=19). Qualitative designs were used in 29 studies, followed by 13 surveys and 11 case studies (figure 3). The empirical studies together reported on 1006 hours of observations, 1697 interviews and 24 744 survey responses. A detailed overview of the included studies is provided in online supplementary appendix 4.

Figure 3.

General characteristics of included studies.

bmjopen-2019-035542supp004.pdf (98.3KB, pdf)

Conditions that can either facilitate or impede the influence of medical leadership on organisational performance

Three themes were identified that described a movement from 1. medical protectionism to management through medicine; 2. command and control to participatory leadership practices; and 3. organisational practices that form incidental versus willing leaders (table 1). References to the relevant articles are provided in the text.

Table 1.

Descriptive themes, categories and subcategories identified through the thematic synthesis

| Impeding conditions |

Facilitating conditions |

|

| Theme 1 | From medical protectionism to management through medicine | |

| Category Subcategory |

Medical protectionism | Management through medicine |

| Motivation to lead | Safeguard physicians’ role, identity and influence | Ensure that management decisions have a positive impact on care and clinical outcomes |

| Perception of management | Going over to the ‘dark side’, concerns about losing credibility among clinical peers | A collective decision-making process where expert knowledge is integrated through openness, trust, respect, and cooperation |

| View of oneself as a manager | Heroes ‘working against the odds’ or righteous victims ‘struggling in the face of adversity’ | Knowledge brokers who see the opportunity for management to enhance clinical identities |

| Role of managerial strategies | To protect autonomy and avoid control, that is, modernised professionalism | Productivity as individualised professional duty that builds on physicians’ inner drive to improve care, that is, new professionalism |

| Outcome of managerial strategies | Disengagement from difficult interactions with colleagues and patients | Engagement across professions that mediates status differences and facilitates knowledge-sharing |

| Theme 2 | From ‘command and control’ to participatory leadership practices | |

| Category Subcategory |

Command and control | Participatory leadership practices |

| Organisational attributes | Bureaucratic, policy driven and hierarchical; poor communication, lack of support, incompetence | Inclusive, solicit input, participatory decision making, shared vision |

| Performance measurement | Externally imposed performance measures with no authority, staff, budget or time | Codesigned performance measures to align quality and safety agendas |

| Outcome | Lack of ownership and trust, values conflict, sense of powerlessness, focus on compliance | Autonomy, meaning, local improvement, better management of clinician relationships, managerial job engagement and self-efficacy |

| Theme 3 | Organisational practices that form incidental versus willing leaders | |

| Category Subcategory |

Practices that form incidental leaders | Practices that form willing leaders |

| Recruitment | Informal networks, ad hoc processes, persuasion, lack of explicit selection criteria or expectations | Formalised, with explicit expectations to match strategic context, early identification of leadership potential, considers demographics and self-efficacy |

| Top management support | Remind of responsibilities by nagging and arguing, crowd agendas with operational matters | Acknowledge and engage medical expertise and academic competence, foster collaborative relationships, effective communication and proactive decision making, remove barriers such as lack of reward and recognition |

| Strategic leadership development | Expected to learn management on their own and on-the-fly. Leader development focused on individuals, divorced from everyday challenges and rarely followed up with opportunities for practice | Starts early, occurs on all levels, benefits patient care and system level challenges not just individuals, and is integral to strategic development |

From medical protectionism to management through medicine

The movement from medical protectionism to management through medicine can be described in terms of motivation to lead, perceptions of management, view of oneself as a manager and the role and outcomes of managerial strategies.

Motivation to lead

While some studies describe physicians’ motivation to be involved in leadership as a way to safeguard their autonomy, identity, status, influence and to resist changes tied to their specialty independent of the organisation’s needs and goals,6 19–24 others emphasise physicians’ drive to make a difference, improve and innovate, and their desire to be engaged, and become good leaders.25 26

Perceptions of management

Managerial and clinical logics are challenging for physicians to reconcile.27–30 Management, perceived as an administrative domain, and the medical domain have distinct cultural differences.31 Physicians are socialised into a specialty with a focus on individual excellence, whereas administrators are team players with diverse backgrounds; clinical decision making has a short time horizon with a single course of action whereas administrative decision-making results in multiple alternatives.31 When clinicians take on managerial roles, they are perceived to occupy a no-mans-land,32 often not meeting the expectations and authority vested in them.33 Many are concerned with losing their credibility among their peers and becoming outsiders,34 with management referred to as the ‘dark side’.27 29 35

Other studies suggest an opportunity to move beyond an adversarial view of management and medicine where management is intertwined with expert knowledge through openness, trust, respect and cooperation, and understood through its impact on clinical practice.20 28–30 36 37

View of oneself as a manager

Medical leaders perceive themselves either as heroes ‘working against the odds’ or as righteous victims ‘struggling in the face of adversity’.27 The heroic narrative is about assuming individual responsibility for achieving one’s vision of the future of healthcare and seeing others, primarily physician-colleagues, in opposition as they are ‘unwilling to change’, ‘pursuing different interests’ and ‘bad communicators’.24

In contrast, other medical leaders see themselves as knowledge brokers who can enhance their physician identities by bridging management and medicine.35 Clinicians and non-clinicians act as partners where understanding is built through communication and presence.31

While some leaders feel it is inappropriate to retain clinical commitments due to a risk of being seen as partisan in relation to a specialty or service,35 most choose to continue clinical practice to maintain a sense of belonging, enhance legitimacy and provide inspiration and insights into daily work, as well as to keep open the option of returning to clinical work in case of failure as a leader.26 35 37 38

Role of managerial strategies

Medical leaders adopt or adapt managerial practices and accept managerial roles as a custodial strategy, referred to as ‘paradigm freeze’.6 19–22 This ‘modernised professionalism’ creates new forms of self-regulation and self-management, such as resisting managers’ attempts to control patient safety programmes; focusing on minimum necessary reporting; selectively participating in managerial meetings; sending out last minute meeting agendas to limit managers’ participation or concealing the significance of certain decisions.20 39 Such behaviours have been characterised as a clinical narrative in medical leaders’ identity where the primary focus is on the exclusive nature of caring for patients, that is, healthcare needs to be safeguarded from non-clinicians.24 Any collaboration with non-clinicians is thought of as ‘making them understand’ or ‘getting them on board’.31

On the other hand, managerial strategies can follow a ‘professional path’, that is, build on medical leaders’ inner drive, resonate with their mental models and be anchored in quality improvement.30 Collaborative leaders surpass organisational and disciplinary boundaries to co-produce care with high quality and cost efficiency, that is, they see the context as a resource that can be collectively adjusted as opposed to individually shaped (heroic leaders).24

As a support, there has been a conscious move to replace the managerial discourse with a leadership discourse.38 40 41 The term ‘medical leadership’ resonates better with professional groups, can remove tensions between operational requirements and visionary aspirations, and potentially influence new work practices.40 41

Outcome of managerial strategies

As clinical managers appear to adhere to managerial control, their clinical identity and professional objectives remain unaffected, that is, loyalty to the profession trumps loyalty to the organisation.20 32 These dynamics result in personal struggles, causing clinicians to disengage from difficult interactions with colleagues and patients, and medical decision-making suffers.42 When ignoring as opposed to engaging with these aspects of professional cultures, professional resistance to change can be triggered.43

When medical leaders choose engagement in management over adherence to managerial control by defining their own and other’s roles, connecting staff, and focusing on goal attainment, they make way for a ‘new professionalism’.30 41 44–46 This has been strengthened by new physician roles (eg, pathway coordinators and hospitalists), which allow physicians to engage in managerial work earlier in their careers,33 and thereby improve their managerial capabilities, including building their social capital and developing different perspectives on problems and solutions.28 30 In addition, the increasingly multiprofessional, team-based service delivery approaches mediate status differences and facilitate knowledge-sharing across professions.25 28 47 48

From ‘command and control’ to participatory leadership practices

The movement from management through ‘command and control’ to participatory leadership practices can be described in terms of differences in organisational attributes, strategies in performance measurement and their outcomes.

Organisational attributes

Healthcare organisations are frequently characterised as bureaucratic, policy driven and hierarchical workplaces with poor organisational communication practices, lack of support for innovation, conflicts and incompetence.25 49–51 Matrix organisations and distributed leadership are presented as solutions, yet medical leaders still believe that the real decision-making power lies outside of care environments, is externalised and hierarchical.27 52

Instead, physicians can be given the opportunity to exhibit inclusive leadership behaviours such as explicitly soliciting team input, engaging in participatory decision-making, working with a shared vision, demonstrating compassion, establishing accountability for key outcomes, transparent communication, nurturing an open space for feedback and good working relations.3 25 51 53–56

Performance measurement

Clinicians on different management levels in hospitals and primary care are held accountable for performance measures and organisational issues with neither the authority, staff, budget, time, nor support to actually implement change or to improve.25 27 34 52 57 58 They find the channels to contribute to policy-making processes inaccessible or exclusionary or with an intention to get buy-in as opposed to improve.59 Executives develop a hostile relationship with policy-makers and a protectionist attitude to their work which spills over to the organisation and is reflected in the disengagement of care delivery staff.59 The positive potential of performance measurement, particularly in terms of monitoring quality data, does not materialise due to a lack of ownership over the indicators and also because of problems with access to data and insufficient resources for data collection.34 57 The time-delay between patient safety incidents and quality reports undermine clinicians’ confidence in the data60 and impede accountability for outcomes.42

Instead of being externally imposed, performance measures can be co-designed through continual dialogue to align agendas for quality and safety34 48 61 and through the design of service delivery. 3 27 Similarly, budgetary participation supports accountability through autonomy as it positively correlates with budget goal commitment, use of budget information, and therefore, budgetary performance.62 Tools, such as managerial accounting could co-exist with clinical practice as they are often seen as technical tools without threat to professional autonomy.20

These practices can be described as medical engagement, that is, the ability to (1) decide how work is done, (2) make suggestions for improvement, (3) set goals, (4) plan and (5) monitor performance in activities targeted at the micro (patient), meso (organisation) and/or macro (health system) levels.63

Outcomes of management through ‘command and control’ versus participatory leadership practices

Organisational culture that relies primarily on management through command and control, hamper physician engagement and contribute to a sense of powerlessness.25 27 34 49–52 57 58 The overwhelming number of performance targets and guidelines that are externally imposed conflict with professional values and interests,22 60 and are so demanding that managers tend to focus on compliance, rather than the proactive development of new solutions, and interest in knowledge creation and innovation diminishes.28 60 A lack of internal support makes medical leaders feel that they are alone with their managerial challenges with limited opportunities to discuss and develop ideas for improvement.34 51 This leads them to rely on personality, status and hierarchy—all insufficient for complex tasks.42 64

When given the opportunity to participate in policy-making, clinicians feel their expertise and contribution are valued and that policies are rooted in practice realities.59 Having physicians act as champions of a policy change, can help to get buy-in from other clinicians and thereby facilitate the implementation of a policy reform.65

Participatory leadership practices motivate, provide autonomy, make performance measurement more accurate and meaningful, enable local improvement and can reinforce professionalism in ways that improve the manager–clinician relationship.20 41 47 48 57 66–68 Anchoring quality improvement in professional practice develops a sense of common responsibility in the organisation, and combining it with education and research nurtures positive views on further improvement initiatives.3 21 25 34 41 43 47 48 59 68 69 Budgetary participation improves overall managerial job engagement as it affects managerial self-efficacy, helps to identify with organisational goals, and, along with role clarity, promotes constructive managerial work attitudes.54 62 70 71 Such positive leadership experiences are associated with managerial job engagement, performance and participation in leadership activities.25 51 54–56 Medical engagement results in increased use of quality-of-care feedback reports, improved data quality, efficiency, innovation, job satisfaction and patient satisfaction.63 72

Organisational practices that form incidental versus willing leaders

Organisational practices that form either incidental or willing leaders can be described in terms of recruitment of medical leaders, top management support and strategic leadership development.

Recruitment of medical leaders

Healthcare organisations require a large number of clinically trained leaders at all levels of the organisation, in particular high quality first-line management.6 32 Despite that interest in leadership can arise from boredom with clinical routine, a desire to take on new challenges,19 or aptitude and energy,73 62% of executive positions in teaching hospitals are filled by external hires, which suggests a failure to identify, develop and promote emerging leaders from within the organisation.38 74 Recruitment of medical leaders most often occurs through informal networks and succeeds through practical reasons such as availability or the persuasive ability of the current managers, without explicit selection criteria or expectations related to performance objectives, goals or measures of success.19 23 26 51 52 When formal recruitment procedures are followed, the process still tends to be ad hoc and lessons learnt by search committees are neither captured nor shared. The consequence of these coercive or ad hoc approaches that generate ‘incidental’ leaders instead of ‘willing’ leaders can be seen early in leadership development, where the latter are more able to ‘absorb’ or construct managerial expertise.38 54 75

To avoid ‘incidental’ medical leaders, recruitment should be formalised with clear financial incentives, identification of leadership potential should start at an early stage by engaging in conversations with front-line physicians, and these future physician leaders should be supported and moulded through opportunities to lead new initiatives.2 19 25 38 51 63 In that process, assessment of professionals’ self-efficacy as a predictor of motivation to lead is recommended.58 Selection of leaders should be part of the overall talent management system74 and the position should have a clear job description that matches the strategic, structural and political contexts.23 34 52 76 Demographics should be considered to avoid management by the ‘old boys’ club’.25 The recruitment process should set clear expectations on what is acceptable professional behaviour as a medical leader, in order to be able to enforce these behaviours in case of a mismatch.76 While the most frequently displayed and among the most valued leadership attributes among physicians is being inspirational, it has the least impact on staff satisfaction.4 Those physicians who demonstrate interest in quality, patient safety, and overall leadership aptitude should be sought.34 52 76 Backgrounds as general internists and practising hospitalists (or other holistic specialisations) seem favourable.28 34

Top management support

Senior leadership teams, particularly Chief Executive Officers (CEO), manage physicians by nagging, arguing and reminding them of their responsibilities, that is, they fail to meaningfully engage medical leaders.50 77 78 CEOs and senior leadership teams tend to crowd medical leaders’ agendas with numerous committees or ‘strategic’ meetings that are filled with operational, not strategic matters.34 40 51

A questionnaire study among staff at the National Health Service concluded that effective leadership practice (eg, engaging staff and collaborators in achieving a compelling vision) is correlated with hospital performance.1 In addition, there is a correlation between how effectively boards work with quality of care and how well executive management teams as a consequence monitor quality and manage operations.61 67 79 Top-level teams should be stable and acknowledge physicians’ medical expertise and academic competence,55 78 and foster collaborative relationships, professional development, effective communication, diffusion of expert knowledge between managers and professionals, and demonstrate a proactive culture for decision making.20 25 60 66 76 80 They also need to remove barriers to medical leadership, for example, reduce the burden of administrative tasks related to information technology, performance analysis and financial management; lack of financial incentives; time commitment pressures; overall lack of support and challenges tied to the timing, location and process of managerial meetings.19 25 26 29 33 37 42 51 This can be done by setting clear expectations,51 introducing collective leadership32 or through hybrid organisations.81 The latter resonates well with the idea of professional bureaucracies where staff has greater influence on decision making than people in formal positions of authority.32

Strategic leadership development

Current undergraduate medical education programmes provide only limited opportunities for professional development and neglect strengthening the ethos and professionalism that would make physicians better fit for the purpose of their work.34 During their clinical careers, they are not sufficiently exposed to professionals who are able to develop their managerial mindset.33 Management skills are perceived to be in conflict with a medical case-orientation and interventionist professional action.43 Previous experiences of being a manager at the unit level are not enough either—physicians still have the tendency to be occupied with small-scale problem solving, which makes it difficult to develop the essential strategic hospital-wide perspective.33 Even if physicians enter management, they see this merely as an intermediate role.37 Medical leaders feel they are thrown into their roles and then expected to learn management on their own and on-the-fly.19 26 Traditional leadership development programmes tend to be offered postpromotion,73 and emphasise the difference between management and leadership, which adds to the problem of translating these to practical situations where they actually are intertwined.40 Leadership training is rarely followed up with concrete opportunities to engage in hospital strategy development.33

The introduction of management competencies needs to start early and focus on taking initiative, organisational and system understanding, becoming team players, communication and shared decision making.33 42 78 Leadership development provides four important opportunities to improve quality and efficiency in healthcare, by (1) increasing the calibre of the workforce, (2) enhancing efficiency in the organisation’s education and development activities, (3) reducing turnover and related expenses and (4) focusing organisational attention on specific strategic priorities.82 Training should improve leaders abilities to address system level challenges and benefit the service, not just the individual.32 83 84 Development initiatives create a space for informal conversations that shape attitudes towards teamwork, safety, management and working conditions.28 40 85 Investments in leadership development should be made at all organisational levels and be seen as part of the strategic development of an organisation.32

Teaching approaches should move from competency to capability development through integration with ongoing improvement efforts where the focus is on participants’ actual challenges as opposed to merely talking about problem solving.19 35 43 75 76 Everyday work practices can become opportunities to develop and test new approaches to service provision and to acquire management and leadership skills (eg, via efficient meetings, medical teamwork, joint decision making and the delegation of responsibilities).21 43 Interprofessional education and training are critical to improve managerial self-efficacy, interest and readiness to be involved in managerial work.25 38 47 58 Through mentoring, coaching and networks, medical leaders with similar roles can share experiences, tools and strategies.25 34 35 38

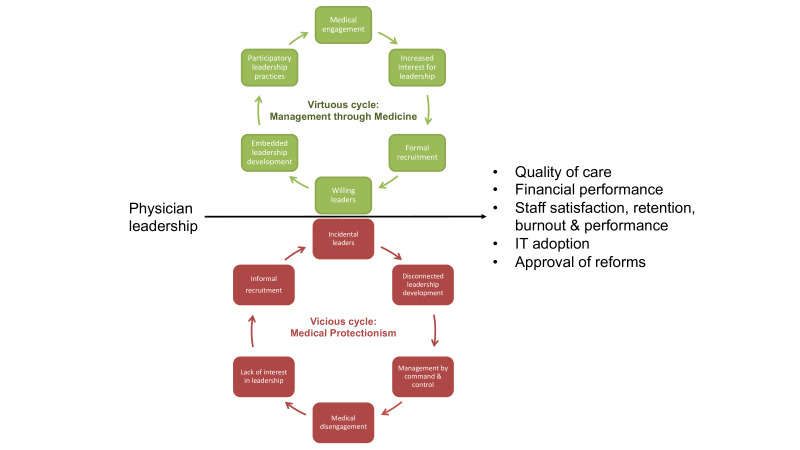

Synthesis

Based on the descriptive themes, we generated a hypothetical model, a critical component of thematic synthesis.12 The model illustrates two opposing schemata related to willing versus incidental leaders (figure 4).

Figure 4.

The virtuous and vicious cycles of medical leadership.

The virtuous cycle describes a set of interdependent strategies that help to anchor management in medicine. The pivotal point is to identify willing leaders who are committed to continually improve their own management and leadership competencies. They are nurtured by an embedded leadership development strategy that fosters participatory leadership practices. Participation cultivates medical engagement among staff and thereby increases interest in leadership roles and management positions. This, in turn, contributes to favourable conditions for formal recruitment and expands the recruitment pool of future willing leaders.

In the vicious cycle, managerial positions are filled by incidental leaders with little interest to improve their own leadership competencies. The lack of interest is reinforced by disconnected leadership development efforts that are perceived as irrelevant to the improvement of healthcare. Managers mimic historically dominant managerial approaches, that is, management through ‘command and control’, which leads to medical disengagement among staff. Disinterest in leadership roles encourages informal recruitment practices which perpetuates the risk for forming incidental leaders.

Discussion

This systematic literature review presents a thematic synthesis of the conditions that can either facilitate or impede the influence of medical leadership on organisational performance. The data suggest that it is the nurturing and engagement of willing leaders that facilitate and the safeguarding strategy of incidental leaders that impede a positive influence on organisational performance. This influence is summarised in a model that describes a virtuous cycle of management through medicine and a vicious cycle of medical protectionism.

The findings of this review resonate with the emerging field of research tied to physician or medical engagement. Medical engagement is defined as a reciprocal relationship between the individuals and the organisational system: ‘the active and positive contribution of doctors, within their normal working roles, to maintaining and enhancing the performance of the organisation, which itself recognises this commitment, in supporting and encouraging high-quality care’.55

While Spurgeon et al76 ask if it is medical leadership or medical engagement that is needed for better performance, we suggest that medical engagement is intimately dependent on the quality of medical leadership. The virtuous cycle of medical leadership illustrates how medical leadership can intervene at the individual, organisational and system levels to enhance medical engagement. At the individual level, medical leaders can explicitly use their medical knowledge to interpret and explain the medical consequences of managerial decisions.86 This would demonstrate commitment to improve healthcare, model an integrative view of management and medicine, and subsequently, enhance professional identities. At the organisational level, medical leaders should formalise recruitment processes, get top management teams to acknowledge and engage medical expertise and academic competence, and embed leadership development in medical practice through quality improvement. Finally, the highest level of medical leadership, including political decision-makers, need to develop an inclusive and collaborative culture characterised by openness, trust and respect, by engaging health professionals in the design and monitoring of performance measures. These combined efforts will not only cultivate medical engagement and by that improve the performance of individual healthcare organisations. They will also enable a shift to new leadership paradigms suitable to the complexity of healthcare,87 and establish conditions favourable for large-system transformation and healthcare reform.88

Implications for research

In terms of future research, the field of medical leadership would benefit from studies conducted in primary care, that include leaders at other than senior managerial levels, and from non-Anglo-American settings. While we came across a few studies on gender balance and internationalisation of the clinical workforce, perspectives on the consequences for medical leadership are lacking. Qualitative studies could further deepen our understanding of the relationship between management and medicine in everyday clinical practice in order to inform leadership development and human resource management efforts. Finally, this review alludes to a need to design and evaluate medical leadership development programmes that are theory based, evidence informed and organisationally embedded.

Limitations

This review is limited by the quality and heterogeneity of included studies. The critical appraisal shed light on the variation of the quality of reporting, primarily in qualitative studies. Similar to a sensitivity analysis, studies which scored below average (n=22) were revisited in terms of their contribution to the synthesis.18 We found that these studies: (1) did not strengthen nor disprove the presented synthesis; (2) made no conceptual contributions, but were relevant for the transferability of the synthesis findings due to their country of origin, setting or study participants; (3) made conceptual contributions, but originated from different disciplines or methods; or (4) made conceptual contributions, but originated from key researchers in the field who prioritised new insights over detailed accounts of their extensive research efforts. Therefore, excluding these studies would not improve the synthesis, but would potentially risk relevant contributions.18 Since the search was timebound to capture contemporary evidence and limited to three databases, we cannot guarantee that all relevant articles were found. While plausible correlations between conditions and performance outcomes are explored, to establish causality requires other approaches to test and determine the strength of the relationships.

Conclusion

The identification of the virtuous or vicious cycles of medical leadership can help us better understand how medical leadership can be both a boon or a barrier to the positive impact that healthcare organisations desire for their patients, staff and society. We can choose to either create willing leaders through medical engagement or accept incidental leaders through medical protectionism. This complex challenge involves questioning conventional wisdom on management and medicine in favour of more participative practices that require long-term investments at the individual, organisational and system levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Karolinska Institutet University Library for their help with the search strategy and access to articles, the Swedish Medical Association for their continued inquiries into physician leadership, and the reviewers for their grounded and insightful feedback.

Footnotes

Twitter: @SavageCarl

Contributors: MS, CS, MB and PM designed the study. MS conducted the search with support from a professional research librarian. MS screened titles, key words and abstracts for inclusion. All authors screened full texts for inclusion. MS extracted data and performed line-by-line coding of the included studies. Based on codes, all authors collectively developed descriptive and analytic themes. MS drafted the manuscript. All authors read, revised, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was commissioned by the Swedish Medical Association. Additional financial support for MS came from AFA Insurance (#150162). PM was funded by the Strategic Research Area Health Care Science, Karolinska Institute/Umeå University during the project period.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: An ethical vetting was deemed unnecessary.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplementary information.

References

- 1.Shipton H, Armstrong C, West M, et al. The impact of leadership and quality climate on hospital performance. Int J Qual Health Care 2008;20:439–45. 10.1093/intqhc/mzn037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sarto F, Veronesi G. Clinical leadership and hospital performance: assessing the evidence base. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 Suppl 2:169. 10.1186/s12913-016-1395-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clay-Williams R, Ludlow K, Testa L, et al. Medical leadership, a systematic narrative review: do hospitals and healthcare organisations perform better when led by doctors? BMJ Open 2017;7:e014474. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menaker R, Bahn RS. How perceived physician leadership behavior affects physician satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:983–8. 10.4065/83.9.983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanafelt TD, Gorringe G, Menaker R, et al. Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:432–40. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lega F, Prenestini A, Spurgeon P. Is management essential to improving the performance and sustainability of health care systems and organizations? a systematic review and a roadmap for future studies. Value Health 2013;16:S46–51. 10.1016/j.jval.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wholey DR, Disch J, White KM, et al. Differential effects of professional leaders on health care teams in chronic disease management groups. Health Care Manage Rev 2014;39:186–97. 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3182993b7f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martinussen PE, Magnussen J. Resisting market-inspired reform in healthcare: the role of professional subcultures in medicine. Soc Sci Med 2011;73:193–200. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ingebrigtsen T, Georgiou A, Clay-Williams R, et al. The impact of clinical leadership on health information technology adoption: systematic review. Int J Med Inform 2014;83:393–405. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2014.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation. London: Sage Publications Ltd, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, et al. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:45–53. 10.1177/135581960501000110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008;8:1–10. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong A, Flemming K, McInnes E, et al. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:181. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations. Acad Med 2014;89:1245–51. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith V, Devane D, Begley CM, et al. Methodology in conducting a systematic review of systematic reviews of healthcare interventions. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:15. 10.1186/1471-2288-11-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2007;7:1–7. 10.1186/1471-2288-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong Q, Pluye P, bregues S F. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018: user guide, 2018: 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carroll C, Booth A. Quality assessment of qualitative evidence for systematic review and synthesis: is it meaningful, and if so, how should it be performed? Res Synth Methods 2015;6:149–54. 10.1002/jrsm.1128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spehar I, Frich JC, Kjekshus LE. Clinicians' experiences of becoming a clinical manager: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:421. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Numerato D, Salvatore D, Fattore G. The impact of management on medical professionalism: a review. Sociol Health Illn 2012;34:626–44. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waring J, Currie G. Managing expert knowledge: organizational challenges and managerial futures for the UK medical profession. Organization Studies 2009;30:755–78. 10.1177/0170840609104819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denis J-L, van Gestel N. Medical doctors in healthcare leadership: theoretical and practical challenges. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 Suppl 2:158–69. 10.1186/s12913-016-1392-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van de Riet MCP, Berghout MA, Buljac-Samardžić M, et al. What makes an ideal hospital-based medical leader? three views of healthcare professionals and managers: a case study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0218095. 10.1371/journal.pone.0218095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berghout MA, Oldenhof L, van der Scheer WK, et al. From context to contexting: professional identity un/doing in a medical leadership development programme. Sociol Health Illn 2020;42:359–78. 10.1111/1467-9566.13007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snell AJ, Briscoe D, Dickson G. From the inside out: the engagement of physicians as leaders in health care settings. Qual Health Res 2011;21:952–67. 10.1177/1049732311399780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ireri SK, Walshe K, Benson L, et al. A comparison of experiences, competencies and development needs of doctor managers in Kenya and the United Kingdom (UK). Int J Health Plann Manage 2017;32:509–39. 10.1002/hpm.2357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin G, Beech N, MacIntosh R, et al. Potential challenges facing distributed leadership in health care: evidence from the UK national health service. Sociol Health Illn 2015;37:14–29. 10.1111/1467-9566.12171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgess N, Strauss K, Currie G, et al. Organizational ambidexterity and the hybrid middle manager: the case of patient safety in UK hospitals. Hum Resour Manage 2015;54:s87–109. 10.1002/hrm.21725 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berghout MA, Fabbricotti IN, Buljac-Samardžić M, et al. Medical leaders or masters?-A systematic review of medical leadership in hospital settings. PLoS One 2017;12:e0184522. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Storkholm MH, Mazzocato P, Savage M, et al. Money's (not) on my mind: a qualitative study of how staff and managers understand health care's triple aim. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:98. 10.1186/s12913-017-2052-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller EJ, Giafaglione B, Chrisman HB, et al. The growing pains of physician-administration relationships in an academic medical center and the effects on physician engagement. PLoS One 2019;14:e0212014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ham C, Dickinson H. Engaging doctors in leadership: what can we learn from international experience and research evidence? London. NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lega F, Sartirana M. Making doctors manage… but how? recent developments in the Italian NHS. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16 10.1186/s12913-016-1394-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes C, Yousefi V, Wallington T, et al. Case study of physician leaders in quality and patient safety, and the development of a physician leadership network. Healthc Q 2010;13 Spec No:68–73. 10.12927/hcq.2010.21969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ham C, Clark J, Spurgeon P, et al. Doctors who become chief executives in the NHS: from keen amateurs to skilled professionals. J R Soc Med 2011;104:113–9. 10.1258/jrsm.2011.110042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leadership FL. Clinician managers and a thing called “ hybridity ”. J Health Organ Manag 2012;26:578–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johansen MS, Gjerberg E, management U. Multiple practices? J Health Organ Manag 2009;23:396–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dickinson H, Snelling I, Ham C, et al. Are we nearly there yet? A study of the English National health service as professional bureaucracies. J Health Organ Manag 2017;31:430–44. 10.1108/JHOM-01-2017-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waring J. Adaptive regulation or governmentality: patient safety and the changing regulation of medicine. Sociol Health Illn 2007;29:163–79. 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.00527.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bresnen M, Hyde P, Hodgson D, et al. Leadership talk: from managerialism to leaderism in health care after the crash. Leadership 2015;11:451–70. 10.1177/1742715015587039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berghout MA, Oldenhof L, Fabbricotti IN, et al. Discursively framing physicians as leaders: institutional work to reconfigure medical professionalism. Soc Sci Med 2018;212:68–75. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sorensen R, Iedema R. Redefining accountability in health care: managing the plurality of medical interests. Health 2008;12:87–106. 10.1177/1363459307083699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noordegraaf M, Schneider MME, Van Rensen ELJ, et al. Cultural complementarity: reshaping professional and organizational logics in developing frontline medical leadership. Public Management Review 2016;18:1111–37. 10.1080/14719037.2015.1066416 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moffatt F, Martin P, Timmons S. Constructing notions of healthcare productivity: the call for a new professionalism? Sociol Health Illn 2014;36:686–702. 10.1111/1467-9566.12093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waring J, Crompton A. A 'movement for improvement'? a qualitative study of the adoption of social movement strategies in the implementation of a quality improvement campaign. Sociol Health Illn 2017;39:1083–99. 10.1111/1467-9566.12560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lin BY-J, Hsu C-PC, Juan C-W, et al. The role of leader behaviors in hospital-based emergency departments' unit performance and employee work satisfaction. Soc Sci Med 2011;72:238–46. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clark KD, Miller BF, Green LA, et al. Implementation of behavioral health interventions in real world scenarios: managing complex change. Fam Syst Heal. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albert K, Sherman B, Backus B. How length of stay for congestive heart failure patients was reduced through six sigma methodology and physician leadership. Am J Med Qual 2010;25:392–7. 10.1177/1062860610371823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nzinga J, McGivern G, English M. Examining clinical leadership in Kenyan public hospitals through the distributed leadership lens. Health Policy Plan 2018;33:ii27–34. 10.1093/heapol/czx167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yanchus NJ, Carameli KA, Ramsel D, et al. How to make a job more than just a paycheck: understanding physician disengagement. Health Care Manage Rev 2020;45:245–54. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bharwani A, Kline T, Patterson M, et al. Barriers and enablers to academic health leadership. Leadersh Health Serv 2017;30:16–28. 10.1108/LHS-05-2016-0023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Epstein AL, Bard MA. Selecting physician leaders for clinical service lines: critical success factors. Acad Med 2008;83:226–34. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181636e07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howard J, Shaw EK, Felsen CB, et al. Physicians as inclusive leaders: insights from a participatory quality improvement intervention. Qual Manag Health Care 2012;21:135–45. 10.1097/QMH.0b013e31825e876a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Macinati MS, Bozzi S, Rizzo MG. Budgetary participation and performance: the mediating effects of medical managers' job engagement and self-efficacy. Health Policy 2016;120:1017–28. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spurgeon P, Mazelan PM, Barwell F. Medical engagement: a crucial underpinning to organizational performance. Health Serv Manage Res 2011;24:114–20. 10.1258/hsmr.2011.011006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Quinn JF. The affect of vision and compassion upon role factors in physician leadership. Front Psychol 2015;6:442. 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Damschroder LJ, Robinson CH, Francis J, et al. Effects of performance measure implementation on clinical manager and provider motivation. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29 Suppl 4:877–84. 10.1007/s11606-014-3020-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mascia D, Dello Russo S, Morandi F. Exploring professionals' motivation to lead: a cross-level study in the healthcare sector. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2015;26:1622–44. 10.1080/09585192.2014.958516 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jorm C, Hudson R, Wallace Am E. Turning attention to clinician engagement in Victoria. Aust Health Rev 2019;43:123–5. 10.1071/AH17100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Canaway R, Bismark M, Dunt D, et al. Medical directors' perspectives on strengthening Hospital quality and safety. J Health Organ Manag 2017;31:696–712. 10.1108/JHOM-05-2017-0109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiang HJ, Lockee C, Bass K, et al. Board oversight of quality: any differences in process of care and mortality? J Healthc Manag 2009;54:15–29. 10.1097/00115514-200901000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Macinati MS, Rizzo MG. Budget goal commitment, clinical managers' use of budget information and performance. Health Policy 2014;117:228–38. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Perreira TA, Perrier L, Prokopy M, et al. Physician engagement: a concept analysis. J Healthc Leadersh 2019;11:101–13. 10.2147/JHL.S214765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spehar I, Sjøvik H, Karevold KI, et al. General practitioners' views on leadership roles and challenges in primary health care: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care 2017;35:105–10. 10.1080/02813432.2017.1288819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McHugh S, Droog E, Foley C, et al. Understanding the impetus for major systems change: a multiple case study of decisions and non-decisions to reconfigure emergency and urgent care services. Health Policy 2019;123:728–36. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kerrissey M, Satterstrom P, Leydon N, et al. Integrating: a managerial practice that enables implementation in fragmented health care environments. Health Care Manage Rev 2017;42:213–25. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jones L, Pomeroy L, Robert G, et al. How do hospital boards govern for quality improvement? a mixed methods study of 15 organisations in England. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:978–86. 10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nelson MF, Merriman CS, Magnusson PT, et al. Creating a physician-led quality imperative. Am J Med Qual 2014;29:508–16. 10.1177/1062860613509683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kampstra NA, Zipfel N, van der Nat PB, et al. Health outcomes measurement and organizational readiness support quality improvement: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:1005. 10.1186/s12913-018-3828-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Macinati MS, Rizzo MG. Exploring the link between clinical managers involvement in budgeting and performance: insights from the Italian public health care sector. Health Care Manage Rev 2016;41:213–23. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Macinati MS, Cantaluppi G, Rizzo MG. Medical managers' managerial self-efficacy and role clarity: how do they bridge the budgetary participation-performance link? Health Serv Manage Res 2017;30:47–60. 10.1177/0951484816682398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ahnfeldt-Mollerup P, Søndergaard J, Barwell F, et al. The relationships between use of quality-of-care feedback reports on chronic diseases and medical engagement in general practice. Qual Manag Health Care 2018;27:191–8. 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyle TJ, Mervyn K. The making and sustaining of leaders in health care. J Health Organ Manag 2019;33:241–62. 10.1108/JHOM-07-2018-0210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mallon WT, Buckley PF. The current state and future possibilities of recruiting leaders of academic health centers. Acad Med 2012;87:1171–6. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826155f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Giri P, Aylott J, Kilner K. Self-determining medical leadership needs of occupational health physicians. Leadersh Health Serv 2017;30:394–410. 10.1108/LHS-06-2016-0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spurgeon P, Long P, Clark J, et al. Do we need medical leadership or medical engagement? Leadersh Health Serv 2015;28:173–84. 10.1108/LHS-03-2014-0029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lega F. Lights and shades in the managerialization of the Italian national health service. Health Serv Manage Res 2008;21:248–61. 10.1258/hsmr.2008.008007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.von Knorring M, de Rijk A, Alexanderson K. Managers' perceptions of the manager role in relation to physicians: a qualitative interview study of the top managers in Swedish healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:271. 10.1186/1472-6963-10-271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tsai TC, Jha AK, Gawande AA, et al. Hospital board and management practices are strongly related to hospital performance on clinical quality metrics. Health Aff 2015;34:1304–11. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Prybil LD, Size PLD. Size, composition, and culture of high-performing Hospital boards. Am J Med Qual 2006;21:224–9. 10.1177/1062860606289628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi S, Holmberg I, Löwstedt J, et al. Executive management in radical change—the case of the Karolinska university hospital merger. Scandinavian Journal of Management 2011;27:11–23. 10.1016/j.scaman.2010.08.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.McAlearney AS. Using leadership development programs to improve quality and efficiency in healthcare. J Healthc Manag 2008;53:319–31. 10.1097/00115514-200809000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nicol ED, Mohanna K, Cowpe J. Perspectives on clinical leadership: a qualitative study exploring the views of senior healthcare leaders in the UK. J R Soc Med 2014;107:277–86. 10.1177/0141076814527274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nieuwboer MS, van der Sande R, van der Marck MA, et al. Clinical leadership and integrated primary care: a systematic literature review. Eur J Gen Pract 2019;25:7–18. 10.1080/13814788.2018.1515907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kristensen S, Christensen KB, Jaquet A, et al. Strengthening leadership as a catalyst for enhanced patient safety culture: a repeated cross-sectional experimental study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010180. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Savage M, Storkholm MH, Mazzocato P, et al. Effective physician leaders: an appreciative inquiry into their qualities, capabilities and learning approaches. Leader 2018;2:95–102. 10.1136/leader-2017-000050 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lieff SJ, Yammarino FJ. How to lead the way through complexity, constraint, and uncertainty in academic health science centers. Acad Med 2017;92:614–21. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Best A, Greenhalgh T, Lewis S, et al. Large-system transformation in health care: a realist review. Milbank Q 2012;90:421–56. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00670.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2019-035542supp001.pdf (63KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035542supp002.pdf (34.2KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035542supp003.pdf (165.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2019-035542supp004.pdf (98.3KB, pdf)