Abstract

Institutional barriers in HIV primary care settings can contribute substantially to disparities in retention in HIV treatment and HIV-related outcomes. This qualitative study compared the perceptions of clinic experiences of persons living with HIV (PLWH) in a Veterans Affairs HIV primary care clinic setting who were retained in care with the experiences of those who were not retained in care. Qualitative data from 25 in-depth interviews were analyzed to identify facilitators and barriers to retention in HIV care. Results showed that participants not retained in care experienced barriers to retention involving dissatisfaction with clinic wait times, low confidence in clinicians, and customer service concerns. For participants retained in care, patience with procedural issues, confidence in clinicians, and interpersonal connections were factors that enhanced retention despite the fact that these participants recognized the same barriers as those who were not retained in care. These findings can inform interventions aimed at improving retention in HIV care.

Keywords: HIV, Qualitative analysis, Veterans, Retention, Barriers, Clinic

Introduction

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the main provider of HIV treatment for U.S. veterans, caring for 25,271 veterans living with HIV (VLWH) in 2011 (Department of Veteran’s Affairs [Dept. V.A.], 2012). Across the HIV care continuum, VLWH are susceptible to similar structural, psychological, socioeconomic, and health-related barriers to retention in care as the general U.S. population (Kramarov & Pastor, 2012; Dept. V.A., 2014). Within the clinic setting, suboptimal scheduling systems, inadequate provider communication, complexities in health system navigation, and negative perceptions of healthcare institutions may adversely affect HIV care retention (Bradford et al., 2007; Giordano, 2011; Kalichman et al., 2002).

Despite these challenges, evidence suggests that HIV+ veterans have better retention (73%) than the general U.S. HIV+ population (between 36.7% and 39.3%) (Mangal et al., 2014; Gardner et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2014). Prior military training, increased “social capital” within the VA, the VA’s universal healthcare access model, and the lack of traditional institutional barriers found in other U.S. clinics are posited to partially explain this pattern (Mangal, et al., 2014; Guest, et al., 2013; Backus, et al., 2015). However, poor retention accounts for the most significant decline along the care continuum for VLHIV, impacting both survival and HIV transmission (Skarbinski et al., 2015).

This study aimed to analyze qualitative interview data from VLWH enrolled in HIV care at the VA IDC and compare the clinic perceptions for those who were retained in care with those who had fallen out of care.

Methods

Participants

VLWH, who were enrolled in care at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) Infectious Diseases Clinic (IDC) of a large metropolitan southeastern city, were included in this study (Table 1, n=25). Sixteen out-of-care (OC) participants who previously attended ≥2 IDC appointments for ≥6 months but had not attended an appointment in the eight months prior to screening, were identified using electronic health records (EHR) and recruited based on time since their last clinic appointment. Nine in-care (IC) participants who had attended ≥2 IDC appointments for ≥6 months and ≥1 in the prior eight months were recruited based on demographic criteria matched to those OC participants after all OC interviews were conducted.

Table 1:

Demographic Data for IC and OC Participants

| Race/Ethnicity | Sex | Age (Years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC Participants | Number (Percentage) | Number (Percentage) | |||

| African American | 6 (24%) | Male | 8 (32%) | Range | 41–65 |

| White | 2 (8%) | Female | 1 (4%) | Average | 53.5 |

| Hispanic-White | 1 (4%) | ||||

| OC Participants | Race | Sex | Age | ||

| Number (Percentage) | Number (Percentage) | ||||

| African American | 11 (44%) | Male | 15 (60%) | Range | 41–67 |

| White | 4 (16%) | Female | 1 (4%) | Average | 52.3 |

| Hispanic-White | 1 (4%) | ||||

| Total | Race/Ethnicity | Sex | Age | ||

| Number (Percentage) | Number (Percentage) | ||||

| African American | 17 (68%) | Male | 23 (92%) | Range | 41–67 |

| White | 6 (24%) | Female | 2 (8%) | Average | 52.4 |

| Hispanic-White | 2 (8%) | ||||

This is the descriptive data about the participants in each group. The table depicts the race, sex, age range, and average age of IC and OC participants.

Data Collection

Data were obtained from 25 qualitative in-depth interviews conducted over a five-month period (24 in-person at the IDC, 1 via telephone, each lasting about one hour) by interviewers trained in qualitative research who had a medical background and were experienced with the VAMC. At the time of their interview, participants were unaware of their group classification, but confirmed EHR information by reporting the date of their last attended IDC appointment. Data were collected using a semi-structured interview guide that included open-ended questions to elicit their experience at the IDC. Consented participants were compensated 20 dollars for their time. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified to maintain patient anonymity.

Data Analysis

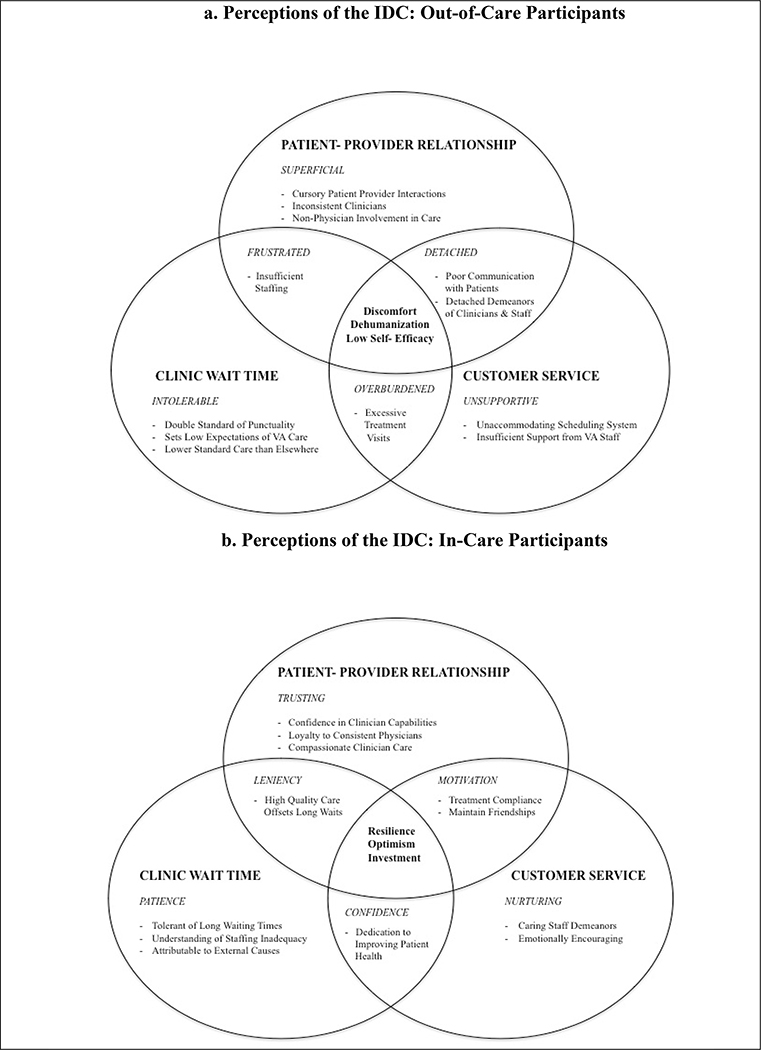

An adapted Grounded Theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, 2015) was used. Data were coded using MaxQDA11 software by common themes in participant narratives. Repeated readings and comparisons of coded data revealed complex connections in participant perceptions and core differences between participant groups, which are represented in 2 explanatory frameworks shown in Figures 1a and 1b. Each framework demonstrates how patient perceptions of care influenced their retention in HIV care. This study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and the VAMC Research and Development Committee.

Figure 1. Perceptions of the IDC by In-Care and Out-of-Care Participants.

The above frameworks depict three spheres of influence on IC and OC participants. The headings in each sphere indicate the broad themes described by IC and OC participants. The italicized sub-headings describe the corresponding attitudes that were implicit in IC participants’ responses. The areas of overlap indicate how the experiences related to each thematic category influenced the experiences in other spheres. The central area of overlap indicates the culminating attitudes and feelings that IC and OC participants expressed regarding the clinic experience.

Results

Our results revealed differences in how participants in each group perceived and approached their HIV care. Figures 1a and 1b shows the conceptual frameworks derived from the data. Table 2 includes quotes from the data that support our findings.

Table 2:

Participant Quotes

| OC Participant Quotes | IC Participant Quotes |

|---|---|

|

Differences Between Groups in Attributions of Responsibility for HIV Care1 | |

|

I. “It’s- It’s, you know, it’s me helping them and they’re helping me but I’m not gonna put all the burden of them helping me on me. I gotta help myself too. So whatever they’re doing… it seem to be workin’. I help myself and theyhelp me when I can’t help myself but I’m not gonna put my whole… me trying to get better on them.” - Male, IC |

X. “… being responsible adults, responsible for your means, we should be able to be responsible for ourselves. … And I should be able to, no matter what the situation, make my appointments. … I should be able to do that, but I haven’t, but I haven’t. So, not tryin’ to, not to make up an excuse or to sidestep my responsibilities, but…, because I have a problem, help me. Help me with my problem. Help me, because I have a problem missing my, you know, keeping my appointments.” - Male, OC |

| Intolerable Wait Times2 | Patience with Wait Times3 |

|

II. “…It’s almost like, sometimes, people have the attitude that where, “Well you’re HIV positive, and we’re… we’re taking care of you, y-, you know, you, you… you, you gotta bow to our every word.” No, I don’t! No I don’t. I don’t have to! I don’t have to because, really, I, you know, I could just go to my civilian doctor and say, “To hell with you!” Get the same treatment. Civilian doctor’s gonna send me to a specialist. If he, my, if my civilian doctor doesn’t specialize in… you know, he’s gonna send me to… he’s gonna forward me to someone who does.” - Male, OC |

XI. “I mean they seem to have worked at trying to cut down on the wait time. You know, I’ve seen, like in the lab and places where they seem to have cut the wait time down for a while, but, you know, it seems to slowly work its way back, but. And I know that’s just the amount of people that they see. And I’m sure some of it’s budget cuts, you know, because of the economy that we’re going through, that they don’t have as many people working as they probably would like to have working.” - Male, IC |

|

III. “…I came in, I had an 11 o clock appointment, and I got- y’know runnin’ around the parking lot tryin’ to find a parking- I got in here about 12 o clock. “Oh, I’m sorry Mr. C, we’re not gonna be able to see you today. OK, we’re gonna have to…” But yet 99% of the time I come in for a 10 o clock appointment, they don’t see my dumb ass ‘til one. I mean, why is it OK for them to sit there and be two hours late but yet I get here fifteen minutes or an hour or whatever after my appointment is due and all of a sudden I get ostracized?” - Male, OC |

|

| Superficial Patient-Provider Relationship4 | Trusting Patient-Provider Relationship5 |

|

IV. “…I, I like to have somebody that is kind of familiar with what is going on. And that I don’t have to keep going over the same history every time … The same questions that you’ve answered a hundred times and everybody has different ideas about how to approach whatever is going on…Because, by that time, all they want to do then is, you know, treat you for HIV. You may have some other things going on. Like, I had some things going with my feet and my hip and stuff, and my back. I never get seen about those things because by the time we go through all this other stuff, our only thing on your mind is get her the anti-viruses and let her go.” - Female, OC |

XII. “I’ve got a fantastic doctor here. I absolutely love her to death. If she ever leaves, I’m gonna probably chain myself to the uh, desk out there and demand that they bring her back, ‘cause I love her. Um, she spends all the time in the world with me. If I need her for an hour, she’d spend an hour with me. And I’m sure the VA probably is not real happy with that, ya know, because of how bad, backed up she might get, but to me that’s the great part about it is I know that when I see her she’s gonna spend as much time as she needs to spend with me. She remembers everything about me. She knows what’s goin’ on in my life. She wants to know about everything that’s been going on in my life. Uh, I’ve just never had a doctor that cared that much, and that enough to remember everything and to ask me about it and see how things are, so. Uh, you know, if I could go to a place probably right next door to my house, if I couldn’t see her, I probably wouldn’t go.” - Male, IC |

|

V. “…It wasn’t like I wasn’t telling ‘em. It wasn’t like I wasn’t saying, “there’s something going on here” and, ya know, “I think it needs to be looked at.” They would say, “oh it’s just something you have to deal with” and “just take this medication,” and, ya know, it just, it just wasn’t. They really, really need to realize that when you’re taking care of somebody with a life, you know, a life changing disease like that, that there’s other problems.” - Male, OC |

|

|

VI. “…I have been with some; they don’t even look up at you. They’re…they’re in that thing, putting it in there. They ask you a few questions. They never look at you. They never identify with you. You know, um, I-I don’t like a doctor like that. I…I want one to at least treat me like I’m human.” - Male, OC |

|

|

VII. “...I don’t trust the [pause]… the care here. The, uh, the undetailed care. I don’t think that they’re specialists. I think that it’s just a bunch of frickin’ students from [organization] that come over here and they’re making major life-changing choices on people’s lives. And I’m not gonna put my life in that care of a… of a 20 year old that is… has no frickin’ idea what HIV is doing to our nation, or to our world.” - Male, OC |

|

| Unsupportive Customer Service6 | Nurturing Customer Service7 |

|

VIII. “…the other thing too is- and-and this is the main reason too, why I quit comin’ here, is I’m tired comin’ down here and sittin there sayin I’m on a three month schedule. Give me an appointment three months out. “Well we can’t give you an appointment three months out, uhh, our-our computers won’t go out that far…” What do you mean your computers don’t go out that far? Computers go out indefinitely. I mean I don’t see the same doctor, so who gives a shit. Pick a date.” - Male, OC |

XIII. “Um, the staff here has been my biggest support staff. When I was I graduated from the University of South Carolina, Columbia, and that it was new to everyone so I can’t really blame anyone, but the [other] VA staff was not as friendly and open and receiving as this one was” - Male, IC |

|

IX. “…And, and basically, it, it was, uh, that we’ll give you this next one, and, uh, you know, uh, uh, we hope that, you know, you get an appointment. Well, you just made me fall through the cracks. You just made me discouraged, to tell me to call back. And I’m trying to manage my healthcare. But you guys are so busy that, you know… I mean, do I have to walk in and, and sit here all day just to get an appointment, just to get my meds?” - Male, OC |

|

These are examples from the qualitative data related to how IC and OC participants expressed their sense of responsibility for HIV care. The first quote is an excerpt from an IC participant describing the importance of personal responsibility in managing their HIV care. The second quote is an excerpt from an OC participant who initially acknowledges the importance of personal responsibility, but then undermines the acknowledgement by describing an inability to maintain that level of responsibility. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, these quotes were selected because they best captured the overall themes expressed by participants in each group.

These are examples from the qualitative data related to how OC participants describe the influence of clinic wait times on their retention in HIV care. The first quote is an excerpt from an OC participant criticizing the perceived inequity of patients being required to wait beyond the appointment time, but being punished under a strictly enforced rescheduling policy in the event of patient tardiness. The second quote is an excerpt afrom an OC participant describing the perceived indifference as evidence that the IDC took advantage of patients who have limited alternatives for HIV providers. The figure is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, these quotes were selected because they a

This is an example from the qualitative data related to how IC participants describe the influence of clinic wait times on their retention in HIV care. The first quote is an excerpt from an IC participant describing the perception that the IDC is proactively addressing the issue of long clinic wait times and the perception that long wait times are attributable to issues beyond the control of the IDC. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, this quote was selected because they best captured the overall themes expressed by participants in each group.

These are examples from the qualitative data related to how OC participants described the influence of the patient-provider relationship on their retention in HIV care. The first quote is an excerpt from an OC participant describing how the brevity of interactions with clinicians, combined with being asked the same basic health questions at each appointment, leaves little time to address other health concerns. The second and third quotes are from OC participants who are describing the perception that clinicians show little concern for participants during their interactions. The fourth quote is from an OC participant describing how interactions with individuals involved in research projects reinforce the perception that participants are not receiving the attention that they feel they deserve from clinicians. The figure is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, these quotes were selected because they best captured the overall themes expressed by participants in each group.

This is an example from the qualitative data related to how IC participants describe the influence of the patient-provider relationship on their retention in HIV care. The second quote is an excerpt from an IC participant who received care from a consistent clinician and perceived a close relationship that motivated them to remain in care and fostered a sense of loyalty to that clinician. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, this quote was selected because they best captured the overall themes expressed by participants in each group.

These are examples from the qualitative data related to how OC participants describe the influence of interactions with non-clinician staff at the AVAMC on their retention in HIV care. The first quote is an excerpt from an OC participant describing an example of how perceived issues with the scheduling contribute to difficulties involved in managing HIV care. The second quote is an excerpt from an OC participant describing how a perceived lack of commitment to patients’ health can contribute to OC participants’ feelings of frustration with the IDC. The figure is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, these quotes were selected because they best captured the overall themes expressed by participants in each group.

This is an example from the qualitative data related to how IC participants describe the influence of interactions with non-clinician staff at the AVAMC on their retention in HIV care. The third quote is an excerpt from an IC participant describing the perception that the IDC staff at the AVAMC play a crucial role in participants’ sense of support, especially compared to VAMC facilities in other cities. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list of the excerpts from the qualitative data. Instead, this quote was selected because they best captured the overall themes expressed by participants in each group.

Attributions of Responsibility for HIV Care

Participants were asked to identify who was “most responsible for managing their HIV treatment.” IC participants attributed primary responsibility for their treatment to themselves (Table 2, Quote I). Conversely, personal responsibility for HIV care was absent in the responses from OC participants. Even if OC participants recognized the benefits of personal responsibility, they perceived that the IDC should play a greater role in managing their HIV (Quote X)

Clinic Wait Time

OC participants (Figure 1a) perceived long wait times as indicating a lack of urgency in IDC services that they did not experience at private clinics and perceived the IDC was taking advantage of patients who have limited healthcare alternatives (Quote II). They also perceived a double-standard whereby punctuality was expected amongst patients, yet providers delayed appointments for hours (Quote III). These perceived inefficiencies led OC participants to begin questioning the value of attending clinic appointments.

IC participants (Figure 1b) articulated tolerance towards the long wait times, which they attributed to constraints beyond the control of the IDC (i.e. patient volume, economic factors). Some IC participants believed wait times had shortened and were comparable to other healthcare settings (Quote XI). For IC participants, an overarching perception of the clinic as a valued resource that does its best to care for patients buffered against potential negative experiences.

Patient-Provider Relationship

OC participants (Figure 1a) reported never having a consistent clinician and described their interactions with clinicians as brief, uninvolved, and not beneficial for addressing non-HIV related issues (Quote IV-VI). In addition, research activities were perceived as interfering with appointments, contributing to mistrust of clinicians (Quote VII). Ultimately, the perceived juxtaposition of fleeting clinician interactions and long wait times reinforced OC participants’ initial negative clinic perceptions.

Some IC participants (Figure 1b) reported having a consistent clinician, but many reported seeing a different provider at each appointment. Participants who received care from a consistent clinician perceived a close relationship that motivated them to remain in care and fostered a sense of loyalty to that clinician (Quote XII). IC participants reported confidence in the clinicians’ ability to address their health needs, even if they saw a different clinician at each appointment. Among IC participants, clinicians were generally viewed as compassionate, caring, knowledgeable, and good communicators.

Customer Service

The customer service sphere refers to policies, services, and non-clinician staff in the IDC. OC participants (Figure 1a) perceived customer service in the IDC as unsupportive and unaccommodating, particularly with the scheduling system which led to difficulties in coordinating their care (Quote VIII). OC participants perceived these difficulties as a lack of IDC commitment to patient health, and they felt isolated and helpless in managing their HIV (Quote IX). Overall, OC participants perceived that IDC staff more often gave reasons why they could not provide assistance rather than actively attempting to accommodate their needs.

IC participants (Figure 1b) perceived a sense of camaraderie with IDC staff that fostered successful retention. They described the IDC staff as having caring demeanors, and perceived them as providing emotional support that would offset provider inconsistency or occasional negative clinic experiences (Quote XIII). The perceived social component of clinic visits, therefore, further facilitated retention for IC participants.

Central Themes

Overall, OC participants’ clinic perceptions (Figure 1a) culminated in negative attitudes towards the IDC, leaving patients with feelings of discomfort in the face of negative clinic experiences, perceived dehumanization resulting from clinic visits described as superficial, and low self-efficacy reflecting perceived attitudes of IDC towards HIV care. IC participants’ overall clinic perceptions (Figure 1b) reflected resilience in their ability to overcome barriers to healthcare, optimism expressed in positive attitudes in the face of clinic barriers, and their high investment in HIV care reflected in their personal responsibility for treatment and innate sense to prioritize clinic retention.

Discussion

In our study, we described how OC and IC participants perceived their experiences in the IDC clinical environment. All participants identified barriers within that environment, but participants in each group demonstrated different cognitive processes in their perceptions of and attitudes towards the role those barriers played in their retention in HIV care.

The IDC offers services aimed at improving retention in care, such as: online medication refills, secure patient messaging (MyHealthEVet), video-based telehealth services, a toll-free medication refill line, and appointment rescheduling. Continuing to improve system level changes, such as decentralizing care through primary care co-management or improving patient empowerment, could further improve patients’ capacity for retention.

A characterization of cognitive processing patterns showed that OC participants tended to attribute the responsibility for their care to external factors (i.e., the clinic environment and clinical staff) whereas IC participants tended to attribute responsibility to themselves. Consistent with the principles of attribution theory (Hilt, 2004), this pattern suggests that, along with making systems-level changes to the clinical care environment itself, a highly-impactful intervention could focus on cognitive attribution processes regarding locus of responsibility for maintaining engagement in HIV care.

This study is limited in that it focused on participants in HIV care within the VA system and may not reflect perceptions and barriers to retention in HIV care in patients outside the VA healthcare system. Although this study focused on the perceptions of VLWH, further research is warranted on cognitive processing of HIV care in other settings as a retention strategy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals: Hannah Wichmann, Carlos del Rio, MD, James Crowe, Susan Schlueter-Wirtz, MPH, Amanda Williams, Mark Nanes, MD, and Kelcie Landon, MPH. This study was funded by the Emory Center for AIDS Research (Grant P30 AI050409) and the Infectious Disease Society of America Medical Scholars Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Backus L, Czarnogorksi M, Yip G, Thomas BP, Torres M, Bell T, Ross D (2015). HIV care continuum applied to the US department of veterans affairs: HIV virologic outcomes in an integrated health care system. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 69(4), 474–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JB, Coleman S, Cunningham W (2007). HIV system navigation: an emerging model to improve HIV care access. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 21(1), 549–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2012). The State of Care for Veterans with HIV AIDS 2011 Summary Report. Retrieved from http://www.hiv.va.gov/provider/policy/2011-HIV-summary-report.asp.

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2014). Veterans Employment 2000 to 2013. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics; Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Employment_Rates_FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, and Burman WJ (2011). The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clinical Infectious Disease, 52(6), 793–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano TP (2011). Retention in HIV care: what the clinician needs to know. Journal of Tropical Medicine, 19(1), 12–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG & Strauss AL (1976). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co. [Google Scholar]

- Guest JL, Weintrob AC, Rimland D, et al. (2013). A Comparison of HAART Outcomes between the US Military HIV Natural History Study (NHS) and HIV Atlanta Veterans Affairs Cohort Study (HAVACS). PLOS One, 8(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Frazier EL, Rhodes P, et al. (2013) Differences in human immunodeficiency virus care and treatment among subpopulations in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 173(14), 1337–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM (2004). Attribution retraining for therapeutic change: theory, practice, and future directions. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 23(4), 289–307. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Graham J, Luke W, & Austin J (2002). Perceptions of health care among persons living with HIV/AIDS who are not receiving antiretroviral medications. AIDS Patient Care & STDs, 16(5), 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramarow EA, & Pastor PN (2012). The Health of Male Veterans and Nonveterans Aged 25–60. United States, 2007–2010. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief, 101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangal JP, Rimland D, & Marconi VC (2014). The continuum of HIV care in a Veterans’ Affairs clinic. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(00). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skarbinski J, Rosenburg E, Paz-Bailey G, Hall HI, Rose CE, Viall AH, Fagan JL, Lansky A, Mermin JH (2015) Human immunodeficiency virus transmission at each step of the care continuum in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 175(4), 588–596. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]