Abstract

Objectives

To assess if mammographic density (MD) changes during neoadjuvant breast cancer treatment and is predictive of a pathological complete response (pCR).

Methods

We prospectively included 200 breast cancer patients assigned to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in the NeoDense study (2014–2019). Raw data mammograms were used to assess MD with a fully automated volumetric method and radiologists categorized MD using the Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS), 5th Edition. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratios (OR) for pCR comparing BI-RADS categories c vs. a, b, and d as well as with a 0.5% change in percent dense volume adjusting for baseline characteristics.

Results

The overall median age was 53.1 years, and 48% of study participants were premenopausal pre-NACT. A total of 23% (N = 45) of the patients accomplished pCR following NACT. Patients with very dense breasts (BI-RADS d) were more likely to have a positive axillary lymph node status at diagnosis: 89% of the patients with very dense breasts compared to 72% in the entire cohort. A total of 74% of patients decreased their absolute dense volume during NACT. The likelihood of accomplishing pCR following NACT was independent of volumetric MD at diagnosis and change in volumetric MD during treatment. No trend was observed between decreasing density according to BI-RADS and the likelihood of accomplishing pCR following NACT.

Conclusions

The majority of patients decreased their MD during NACT. We found no evidence of MD as a predictive marker of pCR in the neoadjuvant setting.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Mammography, Breast density, Neoadjuvant therapy

Highlights

-

•

A prospective study of breast cancer patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

-

•

Study patients with dense breasts often had positive axillary lymph nodes.

-

•

Volumetric breast density decreased for most patients after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

-

•

We found no evidence of mammographic density as a predictive marker of pCR.

Abbreviations

- MD

mammographic density

- BC

breast cancer

- BI-RADS

Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NACT

neoadjuvant chemotherapy

- pCR

pathological complete response

- FEC

fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide

- EC

epirubicin and cyclophosphamide

- HER2

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2

- ALN

axillary lymph node

- ER

estrogen receptor

- PR

progesterone receptor

- VBD%

volumetric breast density percentage

- FGV

fibroglandular volume

- IQR

interquartile range

- OR

odds ratio

- BMI

body mass index

- DCIS

ductal carcinoma in situ

1. Introduction

Mammographic density (MD) has gained significant interest and publicity in breast cancer (BC) screening. This is because women within the highest density categories have up to a 4- to 6-fold increased risk of primary BC in comparison to women with non-dense breasts [1]. The role of MD as a predictive marker in terms of response to diverse oncological treatments is less studied although it has been shown that a decrease in MD during tamoxifen treatment—both in the primary and secondary preventive setting—is associated with risk reduction for BC and recurrence hereof [2,3].

As a complement or alternative to the subjective Breast Imaging-Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) categorization [4], assessment of MD can be estimated by one of many software products operating on both digital vendor-processed and unprocessed mammograms. Validated against BI-RADS and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [5,6], Volpara™ is robust and consistent across manufacturers [7,8] for measurement of volumetric MD.

On the tissue level, high MD represents a proliferative and pro-inflammatory environment [9,10]. It is plausible that the same biological mechanisms associated with tumor initiation and tumor growth in dense breasts may be responsible for a poorer treatment response. Previous studies including one from our group [11,12], have shown that patients with high MD are less responsive to neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) in terms of pathological complete response (pCR)—a surrogate marker for long-term survival [13,14]. However, both previous studies were retrospective and used only a qualitative method for MD assessment (Wolfe categorization [15] and BI-RADS, respectively). Biomarkers, including imaging biomarkers, are needed for more personalized oncological treatment. This study aimed to investigate whether MD assessed with a volumetric quantitative method or a change in MD during NACT for BC is a predictive marker for pCR.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Cohort and clinical parameters

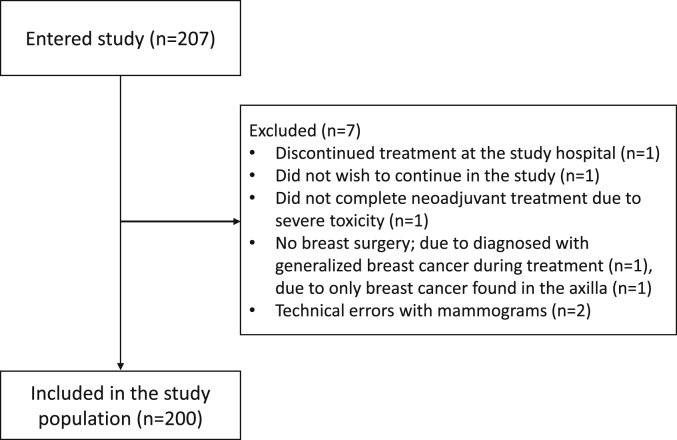

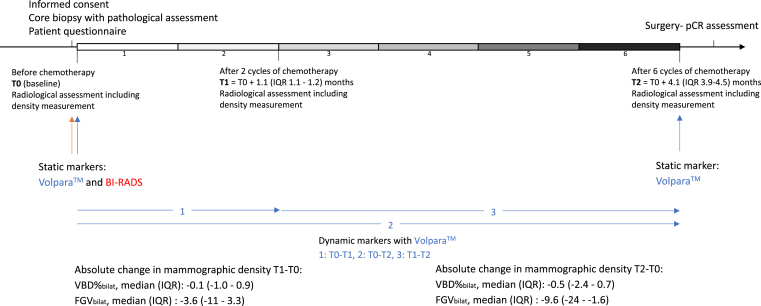

From 2014 to 2019, we included 207 BC patients assigned to NACT within the ongoing SCAN-B trial (Clinical Trials ID NCT02306096) at Skåne University Hospital, Sweden [16,17]. Patients were enrolled at their first visit to the Department of Oncology following their BC diagnosis. The inclusion criteria were female, age ≥18 years, accepting NACT, and ability to give informed written consent. Reasons for exclusion (N = 7) are presented in Fig. 1. Bilateral mammograms and unilateral ultrasound of the cancerous breast and axilla were performed at baseline and after two and six cycles of chemotherapy, respectively (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Patient flow chart.

Fig. 2.

Study timeline.

Patients received NACT according to the same guidelines and standard treatment included three series of fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC) or epirubicin and cyclophosphamide (EC) followed by three series of docetaxel. HER2 double-blockade (trastuzumab and pertuzumab) was provided for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-overexpression concomitantly with NACT. Ninety-seven percent of the patients received standard NACT, and 3% (N = 6) of the patients received a taxane-only NACT-regimen, and one patient received EC only. Among the patients with HER2-overexpressing tumors (N = 48), 94% received a double HER2-blockade whereas the remainder received only trastuzumab.

Clinical data and information on potential confounders were retrieved from patient questionnaires regarding anthropometrics, lifestyle factors, reproductive and hormonal history, previous breast disorders, and current and previous use of prespecified pharmaceuticals. Menopausal status at the time of diagnosis was defined according to self-reported menstrual history and patients with more than 1 year since the last period (secession of periods not caused by birth control, i.e., intrauterine hormonal contraceptive, or recent pregnancy/breastfeeding) were considered postmenopausal. Information on tumor characteristics was retrieved from clinical pathology reports. A pCR was defined as the absence of any residual invasive cancer in the resected breast after surgery as well as all sampled axillary lymph nodes (ALN) following completion of NACT [18]. For the four patients with bilateral BC, the breast with the largest tumor/tumors was followed and evaluated. The Research Electronic Data Capture application was used for secure data entry [19]. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (committee’s reference numbers: 2014/13, 2014/521, and 2016/521).

2.2. Digital mammography

Through prospectively collected radiological study forms (Supplementary Material 1), detailed radiological tumor characteristics were retrieved and noted in real-time at the examination. Clinical bilateral digital mammograms in three views were acquired on different machines: GE Senographe Pristina (3%), Philips MammoDiagnost DR (17%), Philips MicroDose (2%), and Siemens Mammomat Inspiration (77%). All images were saved in their raw, unprocessed format, and MD was estimated with the computerized fully-automatic software Volpara™ (version 1.5.4.0, Volpara Solutions Limited, Wellington, New Zealand) for which technical details are described elsewhere [20]. Briefly, the volumetric estimate is derived from a 2-dimensional digital mammogram that creates an artificial volume based on assumptions of the anatomy of the breast, knowledge of the breast thickness, and image processing [20]. Volumetric breast density percentage (VBD%) is a continuous variable calculated as the ratio of absolute dense tissue volume [fibroglandular volume (FGV)] to total breast volume. At each time point, the craniocaudal view and the mediolateral oblique view in both breasts and the contralateral healthy breast only, respectively, were used to calculate MD (VBD% and FGV). In line with a previous study showing good concordance in MD between the ipsilateral tumorous breast and the contralateral healthy breast [21], a simplified validation was performed showing no large difference in volumetric MD in cancer affected and non-affected breast supporting the use of the average VBD%bilat in the descriptive statistics. Experienced breast radiologists, in direct connection to the examination, assessed the MD of the contralateral breast according to BI-RADS 5th edition [4].

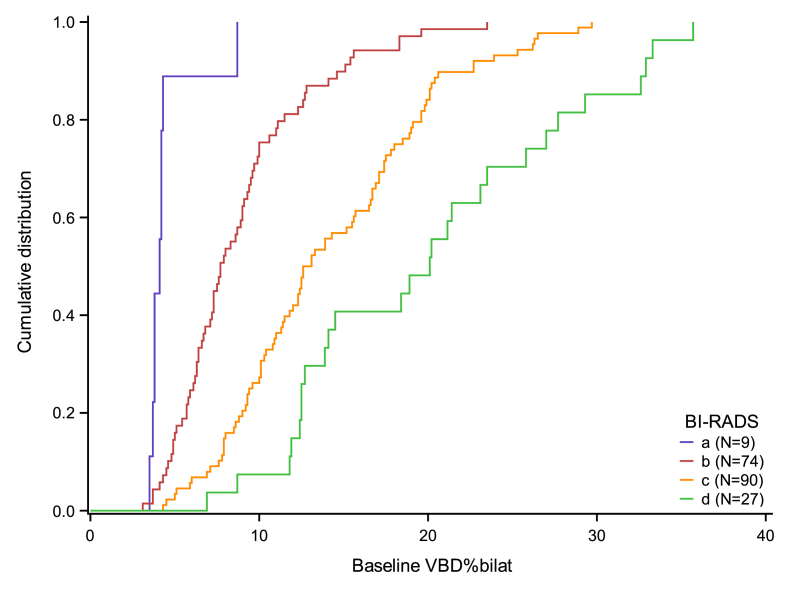

2.3. Statistical analysis

We first plotted the cumulative distribution of the mean of the VBD% in both breasts (VBD%bilat) within each BI-RADS level. We also plotted the change in VBD%bilat from baseline to T1 (after 2nd chemotherapy cycle) and from baseline to T2 (after 6th chemotherapy cycle) versus baseline VBD%bilat; equivalent plots were made with the mean of FGV in both breasts (FGVbilat) instead of VBD%bilat.

Next, patient characteristics were summarized by the BI-RADS level at baseline. Categorical variables were described by counts and percentages whereas continuous variables were described by their median and interquartile range (IQR). For categorical variables, we furthermore assessed the median and IQR of baseline VBD%bilat within each level of the variable. Finally, we described the baseline characteristics and VBD%bilat at T1 and T2 of the patients by pCR status at the end of the follow-up.

We then set up logistic regression models including either VBD%bilat, the VBD% of the contralateral non-cancer affected breast only (VBD%contra), FGVbilat, or BI-RADS as the independent variable. pCR was the dependent (outcome) variable. We also considered dynamic models, i.e., models in which absolute change in MD from T0 to T1 [i.e., VBD% (at T1) minus VBD% (at T0)], T0 to T2, and T1 to T2, respectively, served as independent variables. For both VBD%bilat and VBD%contra, we established models with an odds ratio (OR) corresponding to a 0.3, 0.5, and 2.0 percentage point change in VBD%, respectively. In addition, models based on relative change (OR corresponding to 5% change) in VBD%bilat as the independent variable were established. For FGVbilat, we built the models with an OR corresponding to a 1- and 3-unit change, respectively. In the logistic regression models, we used generalized estimating equations to consider within-hospital site correlations. We set up both crude models and partially- and fully adjusted models. In the partially adjusted models, we included age, body mass index (BMI), menopausal status, parity and hormone replacement therapy; in the fully adjusted models, we also included ER, Ki67, HER2, ALN status, and tumor size at diagnosis. In the dynamic models, we also adjusted for MD at baseline and T1 because a decrease in MD was mostly seen in patients with high MD at baseline. Finally, similar logistic regression models were used to analyze the cohorts within subgroups defined by ALN, ER, and menopausal status. All analyses were carried out in SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Version 9.4, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

The distribution of baseline characteristics according to BI-RADS and VBD%bilat is presented in Table 1 for the 200 BC patients receiving NACT (Fig. 1). For the whole cohort, the median age was 53.1 years (IQR 45.9 to 62.5), the median BMI was 25.6 (IQR 22.4 to 28.7), median VBD%bilat at diagnosis was 11.0 (IQR 7.5 to 17.1), and median FGVbilat was 73.5 cm3 (IQR 52.4 to 100).

Table 1.

Patient and tumor characteristics according to mammographic density at diagnosis.

| BI-RADS a (N = 9) | BI-RADS b (N = 74) | BI-RADS c (N = 90) | BI-RADS d (N = 27) | VBD%bilat median (IQR) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | Median (IQR) | 62 (58–67) | 56 (46–65) | 51 (44–62) | 47 (43–60) | ||

| BMI | Median (IQR) | 34.0 (28.7–36.8) | 26.5 (22.4–28.7) | 24.8 (22.3–28.7) | 23.9 (22.1–25.6) | ||

| Age at menarche | Median (IQR) | 13 (11–14) | 13 (12–14) | 13 (12–14) | 13 (12–13) | ||

| Missing | N = 5 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 4 (4.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal | N = 95 | 0 (0) | 28 (37.8) | 51 (56.7) | 16 (59.3) | 14.0 (10.0–19.6) |

| Postmenopausal | N = 105 | 9 (100) | 46 (62.2) | 39 (43.3) | 11 (40.7) | 8.3 (5.7–12.6) | |

| Number of pregnancies | None | N = 19 | 0 (0) | 6 (8.1) | 10 (11.1) | 3 (11.1) | 12.0 (6.0–20.1) |

| 1 | N = 28 | 1 (11.1) | 11 (14.9) | 10 (11.1) | 6 (22.2) | 10.7 (8.5–17.8) | |

| 2 | N = 76 | 0 (0) | 26 (35.1) | 40 (44.4) | 10 (37.0) | 12.4 (7.7–17.8) | |

| 3+ | N = 77 | 8 (88.9) | 31 (41.9) | 30 (33.3) | 8 (29.6) | 9.8 (6.9–15.0) | |

| Any live birth | No | N = 31 | 1 (11.1) | 9 (12.2) | 15 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | 12.8 (7.1–18.5) |

| Yes | N = 169 | 8 (88.9) | 65 (87.8) | 75 (83.3) | 21 (77.8) | 11.0 (7.6–16.7) | |

| Age first birth (years) | No children | N = 31 | 1 (11.1) | 9 (12.2) | 15 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | 12.8 (7.1–18.5) |

| <20 | N = 10 | 2 (22.2) | 4 (5.4) | 4 (4.4) | 0 (0) | 8.6 (5.8–10.0) | |

| 20–29 | N = 90 | 6 (66.7) | 33 (44.6) | 40 (44.4) | 11 (40.7) | 10.1 (6.6–16.9) | |

| 30–34 | N = 44 | 0 (0) | 15 (20.3) | 22 (24.4) | 7 (25.9) | 13.3 (9.6–19.0) | |

| 35+ | N = 21 | 0 (0) | 11 (14.9) | 7 (7.8) | 3 (11.1) | 10.0 (8.7–15.6) | |

| Missing | N = 4 | 0 (0) | 2 (2.7) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 8.5 (6.9–10.4) | |

| Number of biological children | None | N = 31 | 1 (11.1) | 9 (12.2) | 15 (16.7) | 6 (22.2) | 12.8 (7.1–18.5) |

| 1 | N = 34 | 0 (0) | 16 (21.6) | 14 (15.6) | 4 (14.8) | 9.5 (7.9–12.7) | |

| 2 | N = 96 | 3 (33.3) | 33 (44.6) | 47 (52.2) | 13 (48.1) | 11.7 (7.7–17.4) | |

| 3+ | N = 39 | 5 (55.6) | 16 (21.6) | 14 (15.6) | 4 (14.8) | 9.6 (6.4–16.7) | |

| Alcohol use once a week or more often | Yes | N = 92 | 3 (33.3) | 34 (45.9) | 42 (46.7) | 13 (48.1) | 11.2 (7.7–18.0) |

| No | N = 107 | 6 (66.7) | 40 (54.1) | 47 (52.2) | 14 (51.9) | 10.4 (7.2–16.5) | |

| Missing | N = 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 17.1 (17.1–17.1) | |

| Exercise | More than 4 h/week | N = 64 | 2 (22.2) | 23 (31.1) | 31 (34.4) | 8 (29.6) | 12.0 (7.9–15.7) |

| Less than 4 h/week | N = 100 | 5 (55.6) | 34 (45.9) | 44 (48.9) | 17 (63.0) | 11.8 (7.6–18.9) | |

| Nothing | N = 34 | 2 (22.2) | 16 (21.6) | 14 (15.6) | 2 (7.4) | 8.9 (6.1–11.8) | |

| Missing | N = 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 10.0 (5.7–14.3) | |

| Smoking | Current | N = 19 | 2 (22.2) | 8 (10.8) | 8 (8.9) | 1 (3.7) | 8.7 (5.8–10.8) |

| Former | N = 67 | 3 (33.3) | 24 (32.4) | 30 (33.3) | 10 (37.0) | 10.1 (6.4–16.6) | |

| Never | N = 114 | 4 (44.4) | 42 (56.8) | 52 (57.8) | 16 (59.3) | 12.3 (8.3–17.5) | |

| Ever hormone replacement therapy | Yes | N = 18 | 0 (0) | 7 (9.5) | 8 (8.9) | 3 (11.1) | 11.0 (8.6–18.4) |

| No | N = 182 | 9 (100) | 67 (90.5) | 82 (91.1) | 24 (88.9) | 11.1 (7.4–16.9) | |

| Oral contraceptives | Current | N = 5 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.2) | 2 (7.4) | 14.1 (13.1–14.3) |

| Former | N = 146 | 5 (55.6) | 50 (67.6) | 72 (80.0) | 19 (70.4) | 12.3 (7.9–18.0) | |

| Never | N = 48 | 4 (44.4) | 22 (29.7) | 16 (17.8) | 6 (22.2) | 8.7 (5.9–12.0) | |

| Missing | N = 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5.7 (5.7–5.7) | |

| Tumor size at diagnosis (mm)a | Median (IQR) | 34 (26–40) | 27 (21–38) | 30 (21–40) | 36 (23–42) | ||

| Missing | N = 3 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Estrogen receptor status | Positive (≥10%) | N = 121 | 5 (55.6) | 45 (60.8) | 52 (57.8) | 19 (70.4) | 11.2 (7.6–16.7) |

| Negative (<10%) | N = 79 | 4 (44.4) | 29 (39.2) | 38 (42.2) | 8 (29.6) | 10.9 (7.3–18.3) | |

| Progesterone receptor status | Positive (≥10%) | N = 103 | 6 (66.7) | 38 (51.4) | 43 (47.8) | 16 (59.3) | 10.8 (7.5–16.6) |

| Negative (<10%) | N = 96 | 3 (33.3) | 36 (48.6) | 46 (51.1) | 11 (40.7) | 12.0 (7.3–18.3) | |

| Missing | N = 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 10.1 (10.1–10.1) | |

| HER2 receptor statusb | Positive | N = 48 | 4 (44.4) | 19 (25.7) | 19 (21.1) | 6 (22.2) | 10.0 (6.8–17.4) |

| Negative | N = 152 | 5 (55.6) | 55 (74.3) | 71 (78.9) | 21 (77.8) | 11.3 (7.6–16.7) | |

| Ki67c | High | N = 157 | 8 (88.9) | 60 (81.1) | 69 (76.7) | 20 (74.1) | 10.6 (7.3–16.9) |

| Intermediate | N = 30 | 1 (11.1) | 7 (9.5) | 15 (16.7) | 7 (25.9) | 14.7 (9.2–19.6) | |

| Low | N = 11 | 0 (0) | 6 (8.1) | 5 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 10.1 (9.0–14.6) | |

| Missing | N = 2 | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 8.8 (7.5–10.1) | |

| Axillary lymph node status | Positive | N = 143 | 6 (66.7) | 52 (70.3) | 61 (67.8) | 24 (88.9) | 10.8 (7.3–17.1) |

| Negative | N = 57 | 3 (33.3) | 22 (29.7) | 29 (32.2) | 3 (11.1) | 11.7 (7.6–17.1) | |

Tumor size (largest diameter) was retrieved from study specific radiological protocols and when the size assessments varied between the modalities, the largest measurement was used.

If the tumor was assessed as 3+ with immunohistochemistry and/or amplified with in situ hybridization.

Tumors were considered as low, intermediate or highly proliferative according to laboratory specific cutoffs (site 1: low 0–20%; intermediate 21–30%; high 31–100%, site 2: low 0–14%; intermediate 15–24%; high 25–100%) for proportion of cells staining positive for Ki67.

Patients being younger, premenopausal, leaner (a lower BMI), nulliparous and/or having a history of oral contraceptive use had higher median VBD%bilat at baseline in comparison to their opposites (for age and BMI, respectively, visual assessment was done of boxplot for two groups divided by the median).

In comparison to patients with less dense breasts, patients with very dense breast (BI-RADS d, N = 27) were more likely to have ER-positive tumors and to have a positive ALN status at diagnosis (89%), but VBD%bilat was similar regardless of ER expression and ALN status. In total, only a few tumors had low proliferation [Ki67, (N = 11)]. None of the patients categorized as BI-RADS d (N = 27) had low proliferative tumors. Except for BI-RADS a, there was a trend in that denser breasts implied larger tumors.

Patients with pCR following NACT (N = 45) compared to patients without pCR (N = 155) had similar VBD%bilat at all three time points (Table 2). Patients with ER-negative, PR-negative, and/or HER2-overexpressing tumors, negative ALN status, or high proliferation (Ki67) were more likely to obtain pCR irrespective of MD.

Table 2.

Patient and tumor characteristics at diagnosis according to pathological complete response (pCR).

| pCR (N = 45) | Non-pCR (N = 155) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| VBD%bilat diagnosis | Median (IQR) | 12.4 (7.1–17.1) | 11.0 (7.7–16.9) |

| Missing | 2 (4.4) | 5 (3.2) | |

| VBD%bilat at T1 | Median (IQR) | 10.9 (7.1–17.0) | 10.7 (7.8–15.9) |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 7 (4.5) | |

| VBD%bilat at T2 | Median (IQR) | 11.2 (7.3–15.3) | 9.7 (7.7–14.7) |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 6 (3.9) | |

| BI-RADS at baseline | a | 3 (6.7) | 6 (3.9) |

| b | 19 (42.2) | 55 (35.5) | |

| c | 17 (37.8) | 73 (47.1) | |

| d | 6 (13.3) | 21 (13.5) | |

| Age at diagnosis | Median (IQR) | 53 (46–62) | 53 (46–63) |

| BMI | Median (IQR) | 25.5 (22.9–28.7) | 25.6 (22.4–28.7) |

| Age at menarche | Median (IQR) | 13 (12–14) | 13 (12–14) |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Menopausal status | Premenopausal | 20 (44.4) | 75 (48.4) |

| Postmenopausal | 25 (55.6) | 80 (51.6) | |

| Number of pregnancies | None | 3 (6.7) | 16 (10.3) |

| 1 | 9 (20.0) | 19 (12.3) | |

| 2 | 13 (28.9) | 63 (40.6) | |

| 3+ | 20 (44.4) | 57 (36.8) | |

| Any live birth | No | 6 (13.3) | 25 (16.1) |

| Yes | 39 (86.7) | 130 (83.9) | |

| Age first birth (years) | No children | 6 (13.3) | 25 (16.1) |

| <20 | 4 (8.9) | 6 (3.9) | |

| 20–29 | 18 (40.0) | 72 (46.5) | |

| 30–34 | 11 (24.4) | 33 (21.3) | |

| 35+ | 6 (13.3) | 15 (9.7) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 4 (2.6) | |

| Number of biological children | None | 6 (13.3) | 25 (16.1) |

| 1 | 9 (20.0) | 25 (16.1) | |

| 2 | 19 (42.2) | 77 (49.7) | |

| 3+ | 11 (24.4) | 28 (18.1) | |

| Alcohol use once a week or more often | Yes | 18 (40.0) | 74 (47.7) |

| No | 26 (57.8) | 81 (52.3) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Exercise | More than 4 h/week | 11 (24.4) | 53 (34.2) |

| Less than 4 h/week | 26 (57.8) | 74 (47.7) | |

| Nothing | 8 (17.8) | 26 (16.8) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Smoking | Current | 4 (8.9) | 15 (9.7) |

| Former | 16 (35.6) | 51 (32.9) | |

| Never | 25 (55.6) | 89 (57.4) | |

| Ever hormone replacement therapy | Yes | 2 (4.4) | 16 (10.3) |

| No | 43 (95.6) | 139 (89.7) | |

| Oral contraceptives | Current | 0 (0) | 5 (3.2) |

| Former | 35 (77.8) | 111 (71.6) | |

| Never | 10 (22.2) | 38 (24.5) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Tumor size at diagnosis (mm)a | Median (IQR) | 29 (22–38) | 30 (21–40) |

| Missing | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Estrogen receptor status | Positive (≥10%) | 10 (22.2) | 111 (71.6) |

| Negative (<10%) | 35 (77.8) | 44 (28.4) | |

| Progesterone receptor status | Positive (≥10%) | 5 (11.1) | 98 (63.2) |

| Negative (<10%) | 40 (88.9) | 56 (36.1) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | |

| HER2 receptor statusb | Positive | 20 (44.4) | 28 (18.1) |

| Negative | 25 (55.6) | 127 (81.9) | |

| Ki67c | High | 40 (88.9) | 117 (75.5) |

| Intermediate | 5 (11.1) | 25 (16.1) | |

| Low | 0 (0) | 11 (7.1) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Axillary node status | Positive | 25 (55.6) | 118 (76.1) |

| Negative | 20 (44.4) | 37 (23.9) | |

Tumor size (largest diameter) was retrieved from study specific radiological protocols and when the size assessments varied between the modalities, the largest measurement was used.

If the tumor was assessed as 3+ with immunohistochemistry and/or amplified with in situ hybridization.

Tumors were considered as low, intermediate or highly proliferative according to laboratory specific cutoffs (site 1: low 0–20%; intermediate 21–30%; high 31–100%, site 2: low 0–14%; intermediate 15–24%; high 25–100%) for proportion of cells staining positive for Ki67.

The distribution of BI-RADS categories in relation to VBD%bilat measured with Volpara™ at baseline is visualized in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Agreement between BI-RADS and volumetric breast density percentage (VBD%bilat).

About half of the patients (47%) decreased their VBD%bilat between baseline and T1 and the corresponding percentage between baseline and T2 was 56%. Only a small temporal change in VBD%bilat was seen between baseline and T1 [median absolute decrease −0.1 (IQR -1.0 to 0.9)] whereas a slightly more pronounced change in VBD%bilat was seen between baseline and T2 [median absolute decrease −0.5 (IQR -2.4 to 0.7)]. A larger proportion of patients decreased their FGVbilat during NACT; a total of 61% of the patients decreased their FGVbilat between baseline and T1 [median absolute decrease −3.6 (IQR -11 to 3.3)] and 74% of the patients decreased their FGVbilat between baseline and T2 [median absolute decrease −9.6 (IQR -24 to −1.6)] (Supplementary Material 2).

No association was seen between MD measured with Volpara™ as a static marker at T0 and T2 (VBD%bilat, VBD%contra, and FGVbilat) or as a dynamic marker (ΔVBD%bilat, ΔVBD%contra, and ΔFGVbilat) and pCR using different logistic regression models, iteratively adjusted for increasing numbers of variables (Table 3, Supplementary Material 3, and Supplementary Material 4). Furthermore, no association was found between volumetric MD and pCR for OR corresponding to 0.3 and 2.0 percentage point change in VBD%, respectively, 5% change in VBD%bilat, and a 1-unit change in FGV. We did not find any association between ΔVBD%bilat, ΔVBD%contra, or ΔFGVbilat in the subgroup analyses based on menopausal status, ER expression, and ALN status. No trend was observed between decreasing BI-RADS categories and the likelihood of accomplishing pCR (Table 4). When using BI-RADS c as a reference, patients with both lower and higher BI-RADS categories had a higher likelihood of achieving pCR.

Table 3.

Associations between VBD%bilat and pathological complete response following neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

| VBD%bilat exposure type, OR correspond to a 0.5 unit change in VBD%bilat | N | Cases | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 adjusted for VBD%bilat at T0 OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Static T0 | 188 | 42 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 1.00 (0.97–1.03) | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | |

| Static T2 | 187 | 43 | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 1.00 (0.97–1.04) | 1.01 (0.97–1.06) | |

| Dynamic T0-T1 | 180 | 41 | 1.00 (0.91–1.09) | 1.00 (0.92–1.08) | 0.96 (0.87–1.06) | 0.97 (0.89–1.07) |

| Dynamic T0-T2 | 181 | 41 | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 1.00 (0.92–1.09) |

| Dynamic T1-T2 | 181 | 42 | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 1.02 (0.94–1.11) | 1.02 (0.93–1.12) | 1.05 (0.95–1.16)a |

Model 1: crude analysis.

Model 2: minimally adjusted (age, BMI, menopause, parity, HRT) analysis.

Model 3: fully adjusted (model 2 + ER, Ki67, HER2, axillary node status and tumor size at diagnosis) analysis.

Adjusted for VBD%bilat at T1.

Table 4.

Associations between BI-RADS at diagnosis and pathological complete response following neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

| BI-RADS | N | Cases | Model 1 OR (95% CI) | Model 2 OR (95% CI) | Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 9 | 3 | 2.22 (1.49–3.30) | 2.32 (1.09–4.94) | 1.56 (0.43–5.70) |

| b | 72 | 19 | 1.59 (1.46–1.73) | 1.57 (1.37–1.80) | 1.49 (1.45–1.52) |

| c | 87 | 16 | |||

| d | 27 | 6 | 1.27 (0.34–4.75) | 1.23 (0.37–4.11) | 2.37 (1.15–4.88) |

Model 1: crude analysis.

Model 2: minimally adjusted (age, BMI, menopause, parity, HRT) analysis.

Model 3: fully adjusted (model 2 + ER, Ki67, HER2, axillary node status and tumor size at diagnosis) analysis.

4. Discussion

In this study of 200 prospectively included BC patients, approximately three-quarters of the patients decreased their FGVbilat during NACT. We found no evidence of MD as a predictive marker in the neoadjuvant setting (neither with Volpara™ nor with BI-RADS). Two previous studies [11,12] found low MD at diagnosis associated with improved rates of pCR, however, both were retrospective and used a qualitative density method. Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics were comparable across the previous two studies as well as this work (besides the single HER2-blockade in contrast to the double HER2-blockade in the current study). Another retrospective study using BI-RADS for MD assessment did not find such an association [22]; however, it was based on a cohort that was different from many others—a low pCR rate (15%), suboptimal NACT (i.e., no anti-HER2 treatment to patients with HER2-overexpressing tumors), and a pCR definition that included patients with residual invasive tumor cells making comparison with other studies difficult. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between MD measured with a volumetric quantitative method and response to NACT, and investigate the rate and quantification of MD change during NACT.

It is of interest to look at the temporal association between MD and a certain intervention since changes in MD can modulate the risk, and recurrence, of BC [2,23]. While a larger group of studies [2,3,[24], [25], [26], [27], [28]] have explored the effect of endocrine treatment on MD, less is known about the association between treatment response to chemotherapy (with or without anti-HER2 therapy) and MD. A longitudinal study investigating the effect of antiestrogen treatment in the adjuvant BC setting on volumetric MD changes in a relatively large study cohort showed an annual decrease in VBD% of 0–2% [24]. The corresponding number for a small study using MRI was almost 4% [28].

Chen et al. further investigated the change in breast density measured with MRI during NACT in a small number of patients (N < 45 in both studies) and showed an 11–13% reduction in percent breast density measured with MRI [29,30]. Previous studies demonstrate a reduction in MD during adjuvant chemotherapy [[31], [32], [33]], however only one of them provided a quantitative measure of the change in MD (−2.9 percentage points %MD). In two studies, women, predominantly younger women, with ≥10% MD reduction had a reduced risk of contralateral BC compared to women with less reduced MD [31,33]. In our study, the median decline in MD during NACT was −0.5 percentage points (IQR -2.4 to 0.7) correlating to a mean decline of 4.5%. In this context, despite our relatively short period of time between first and last measurement (4.1 months, IQR 3.9–4.5 months), we should have been able to detect and quantify a potential association between density and outcome measure (pCR).

MD changes throughout a woman’s life along with age and hormonal events [34] with a steep decline occurring around menopausal change [35]. In the NSABP B-30 trial [36], the vast majority of premenopausal patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for BC had at least a 6-month long period of amenorrhea, and it is reasonable to expect similar proportions in our neoadjuvant-treated cohort since the patients were treated with the same combination of chemotherapy agents [36]. There was a more pronounced association between MD reductions and chemotherapy in premenopausal patients in comparison to postmenopausal patients [29,32]: This is likely related to a change in the hormonal milieu. Also, lobular atrophies may contribute to a MD reduction during chemotherapy [37]. Thus, it is difficult to identify the underlying biological explanation for the small decline in MD seen in our study.

Bilateral and contralateral mammograms, respectively, were used for Volpara™-assessment in this study. Each Volpara™-output includes VBD%, FGV, and the absolute non-dense volume in the breast/breasts. Previous studies have shown a positive association between both FGV and VBD% and BC risk with a more pronounced association seen with VBD% [[38], [39], [40]]; these data indicate the importance of the microenvironment of the non-dense breast tissue in the BC etiology. Tumor characteristics as well as host factors influence the tumor response to treatment, e.g. triple negative subtypes are known to be highly responsive to NACT [41]. This motivates the adjustments in our logistic regression models. Representing the microenvironment of the surrounding breast tissue [22], MD is a host factor that influences the tumor response to treatment. In terms of MD and tumor characteristics, previous studies have shown associations between higher MD and positive ALN and larger tumor size [[42], [43], [44]]. In our study, approximately 70% of the patients had a positive ALN—the corresponding number for patients with very dense breasts (BI-RADS d, N = 27) was 89%. In our cohort, the median tumor size was 30.0 mm (IQR 22.0–40.0 mm) with a tendency for a larger tumor, the denser the breast. One plausible explanation contributing to the inconsistent results regarding MD as a predictive marker for pCR during NACT seen in our studies is that, in the current study, a high MD is seemingly associated with high proliferation (Ki67), which is in turn associated with a better response to NACT [[45], [46], [47]]. This dilutes the previously suggested association between MD and pCR.

Several systems for pathological evaluation of the complex post-NACT response exist, and the clinical importance of residual ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) only is not yet fully understood [48]. Regardless of whether residual DCIS only is considered as pCR or not, both definitions are associated with similar improved prognosis [14], but the pCR rates are lower in studies using the most conservative definition. In order to include all patients with favorable prognosis, in this study, patients with only residual DCIS were categorized as having accomplished pCR.

Our study has several strengths including the prospective cohort with detailed information on patient and tumor characteristics. We used both a fully-automated volumetric density method on raw digital mammograms as well as BI-RADS categorization of processed images. Previous studies have shown different degrees of agreement and correlation [49] between VBD% and BI-RADS ranging from poor to good [[50], [51], [52]]. Given the proportions of the displayed patient and tumor characteristics and the ratio of pCR, we suggest that our cohort is a good reflection of the general patient group as a whole and offers external validity.

The issue of lacking consistency regarding the vendor and model of the machines must be addressed. We made no adjustment for this variable because Volpara™ has been shown to offer a consistent measurement of volumetric MD across vendors [7,8]. The matter of alignment [53] of mammograms that makes the amount of breast tissue similar in each image must be brought to attention when dealing with a change in MD over time. To minimize error due to alignment, each technician was repeatedly instructed to similarly position the breast each time and to capture the entire breast and not just the tumor. Thus, we believe that the principally important concept of alignment will not affect our results on a group level. No subgroup analyses based on the St. Gallen BC subtype [54] were performed due to our limited number of patients. However, when stratifying on ER expression, no association was seen between volumetric MD and pCR. A larger dataset is needed to better understand the role of MD as a predictive marker during NACT in different subtypes of BC. This enables clinical applicability. Longer follow-up might be needed to demonstrate a consistent decline in MD.

5. Conclusion

In summary, a large proportion of the patients decreased their mammographic density during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. We found no evidence of mammographic density, assessed with both quantitative and qualitative methods, as a predictive marker for complete pathological response in the neoadjuvant setting. Future larger studies should examine whether mammographic density holds predictive value regarding treatment with chemotherapy.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

IS participated in designing the study, made the study protocols, coordinated the enrollment of patients, collected the data, wrote the statistical plan, interpreted the data, solely drafted the manuscript (except for “Statistical analyses”), and coordinated the revision of the manuscript. DF provided technical support during image collection, aided in density assessments, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. UH assisted in making the statistical plan, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, co-wrote the “Statistical analyses” part of the manuscript, and substantially revised the manuscript. HS intellectually contributed to decisions regarding density assessment and interpretation and revised the manuscript. PH participated in the design of the study, provided technical support during image collection, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. SZ participated in the general design of the study, interpreted the data, and contributed to the adjustment of the manuscript. SB was the main contributor to the initial design of the study, interpreted the data, and revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

IS: MD, Physician at Skåne University Hospital, Lund, PhD-student Oncology, Lund University, Skåne University Hospital Lund, Sweden.

DF: Medical Physicist, PhD, Medical Radiation Physics, Department of Translational Medicine, Lund University, Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden.

UH: MSc, PhD, Statistician in the Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark.

HS: MD, Specialist in Radiology, PhD, Associate Professor, Diagnostic Radiology, Department of Translational Medicine, Lund University, Skåne University Hospital Lund and Malmö, Sweden.

PH: MD, PhD, full professor at the Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden.

SZ: MD, PhD, Professor, Senior Consultant, Department of Imaging and Functional Medicine, Skåne University Hospital Malmö, and Diagnostic Radiology, Department of Translational Medicine, Lund University, Sweden.

SB: MD, PhD, Professor, Consultant, Department of Oncology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark. Visiting Professor, Division of Oncology and Pathology, Lund University, Sweden.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Breast Cancer Group (BRO) and the Governmental Funding of Clinical Research within National Health Services, Sweden (ALF-medel). The Volpara™ software was provided by the Volpara™ company. The funding resources had no role in the study design, data collection, analyses, data interpretation, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Lund, Sweden (committee’s reference number: 2014/13, 2014/521 and 2016/521).

Informed consent

Oral and written information was provided to the patients. Informed written consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Declaration of competing interest

SZ and HS have received speakers’ fees and travel support from Siemens Healthcare AG. SZ has received consultancy fees from Collective Minds Radiology AB. PH is a member of a scientific advisory board for: Cancer Research UK, iCAD and Atossa Genetics. SB has received speakers’ fees from Pfizer, is a member of a Pfizer advisory board, and has received travel support from Roche. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants in the study. The authors thank research nurse Lina Zander for excellent study coordination. We thank all personnel at Unilabs Malmö and Helsingborg for their good care of the study patients. We also thank Aki Tuuliainen at Karolinska Institute for technical help enabling raw data saving. We also express our gratitude to Volpara™ for providing access to the Volpara™ software.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2020.05.013.

Contributor Information

Ida Skarping, Email: ida.skarping@med.lu.se.

Daniel Förnvik, Email: daniel.fornvik@med.lu.se.

Uffe Heide-Jørgensen, Email: uhj@clin.au.dk.

Hanna Sartor, Email: hanna.sartor@med.lu.se.

Per Hall, Email: per.hall@ki.se.

Sophia Zackrisson, Email: sophia.zackrisson@med.lu.se.

Signe Borgquist, Email: signe.borgquist@auh.rm.dk.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.McCormack V.A., dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2006;15(6):1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J., Humphreys K., Eriksson L., Edgren G., Czene K., Hall P. Mammographic density reduction is a prognostic marker of response to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2249–2256. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shawky M.S., Martin H., Hugo H.J., Lloyd T., Britt K.L., Redfern A., Thompson E.W. Mammographic density: a potential monitoring biomarker for adjuvant and preventative breast cancer endocrine therapies. Oncotarget. 2017;8(3):5578–5591. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sickles E., D’Orsi C.J., Bassett L.W. ACR BI-RADS® Atlas, breast imaging reporting and data system. American College of Radiology; Reston, VA: 2013. ACR BI-RADS® mammography. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gubern-Merida A., Kallenberg M., Platel B., Mann R.M., Marti R., Karssemeijer N. Volumetric breast density estimation from full-field digital mammograms: a validation study. PloS One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang J., Azziz A., Fan B., Malkov S., Klifa C., Newitt D., Yitta S., Hylton N., Kerlikowske K., Shepherd J.A. Agreement of mammographic measures of volumetric breast density to MRI. PloS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damases C.N., Brennan P.C., McEntee M.F. Mammographic density measurements are not affected by mammography system. J Med Imaging. 2015;2(1) doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.2.1.015501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brand J.S., Czene K., Shepherd J.A., Leifland K., Heddson B., Sundbom A., Eriksson M., Li J.M., Humphreys K., Hall P. Automated measurement of volumetric mammographic density: a tool for Widespread breast cancer risk assessment. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 2014;23(9):1764–1772. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin L.J., Boyd N.F. Mammographic density. Potential mechanisms of breast cancer risk associated with mammographic density: hypotheses based on epidemiological evidence. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10(1):201. doi: 10.1186/bcr1831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huo C.W., Chew G., Hill P., Huang D., Ingman W., Hodson L., Brown K.A., Magenau A., Allam A.H., McGhee E. High mammographic density is associated with an increase in stromal collagen and immune cells within the mammary epithelium. Breast Cancer Res. 2015;17:79. doi: 10.1186/s13058-015-0592-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elsamany S., Alzahrani A., Abozeed W.N., Rasmy A., Farooq M.U., Elbiomy M.A., Rawah E., Alsaleh K., Abdel-Aziz N.M. Mammographic breast density: predictive value for pathological response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. Breast. 2015;24(5):576–581. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skarping I., Fornvik D., Sartor H., Heide-Jorgensen U., Zackrisson S., Borgquist S. Mammographic density is a potential predictive marker of pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. BMC Canc. 2019;19(1):1272. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6485-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Minckwitz G., Untch M., Ju Blohmer, Costa S.D., Eidtmann H., Fasching P.A., Gerber B., Eiermann W., Hilfrich J., Huober J. Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(15):1796–1804. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortazar P., Zhang L., Untch M., Mehta K., Costantino J.P., Wolmark N., Bonnefoi H., Cameron D., Gianni L., Valagussa P. Pathological complete response and long-term clinical benefit in breast cancer: the CTNeoBC pooled analysis. Lancet. 2014;384(9938):164–172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe J.N. Risk for breast cancer development determined by mammographic parenchymal pattern. Cancer. 1976;37(5):2486–2492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2486::aid-cncr2820370542>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saal L.H., Vallon-Christersson J., Hakkinen J., Hegardt C., Grabau D., Winter C., Brueffer C., Tang M.H., Reutersward C., Schulz R. The Sweden Cancerome Analysis Network - breast (SCAN-B) Initiative: a large-scale multicenter infrastructure towards implementation of breast cancer genomic analyses in the clinical routine. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0131-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryden L., Loman N., Larsson C., Hegardt C., Vallon-Christersson J., Malmberg M., Lindman H., Ehinger A., Saal L.H., Borg A. Minimizing inequality in access to precision medicine in breast cancer by real-time population-based molecular analysis in the SCAN-B initiative. Br J Surg. 2018;105(2):e158–e168. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin M.B., Greene F.L., Edge S.B., Compton C.C., Gershenwald J.E., Brookland R.K., Meyer L., Gress D.M., Byrd D.R., Winchester D.P. The Eighth Edition AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: Continuing to build a bridge from a population-based to a more "personalized" approach to cancer staging. Ca - Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(2):93–99. doi: 10.3322/caac.21388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Highnam R.B.S.M., Yaffe M.J., Karssemeijer N., Harvey J., vol . Robust breast composition measurement - VolparaTM. In: Martí J., Oliver A., Freixenet J., Martí R., editors. vol. 6136. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2010. (Digital mammography. IWDM 2010. Lecture notes in computer science). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Habel L.A., Dignam J.J., Land S.R., Salane M., Capra A.M., Julian T.B. Mammographic density and breast cancer after ductal carcinoma in situ. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(19):1467–1472. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castaneda C.A., Flores R., Rojas K., Flores C., Castillo M., Milla E. Association between mammographic features and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced breast carcinoma. Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Ther. 2014;7(4):149–156. doi: 10.1016/j.hemonc.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roman M., Sala M., Bare M., Posso M., Vidal C., Louro J., Sanchez M., Penalva L., Castells X., Bs group. Changes in mammographic density over time and the risk of breast cancer: an observational cohort study. Breast. 2019;46:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Engmann N.J., Scott C.G., Jensen M.R., Ma L., Brandt K.R., Mahmoudzadeh A.P., Malkov S., Whaley D.H., Hruska C.B., Wu F.F. Longitudinal changes in volumetric breast density with tamoxifen and Aromatase inhibitors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(6):930–937. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuzick J., Warwick J., Pinney E., Warren R.M., Duffy S.W. Tamoxifen and breast density in women at increased risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(8):621–628. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyante S.J., Sherman M.E., Pfeiffer R.M., Berrington de Gonzalez A., Brinton L.A., Aiello Bowles E.J., Hoover R.N., Glass A., Gierach G.L. Prognostic significance of mammographic density change after initiation of tamoxifen for ER-positive breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3) doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuzick J., Warwick J., Pinney E., Duffy S.W., Cawthorn S., Howell A., Forbes J.F., Warren R.M. Tamoxifen-induced reduction in mammographic density and breast cancer risk reduction: a nested case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(9):744–752. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J.H., Chang Y.C., Chang D., Wang Y.T., Nie K., Chang R.F., Nalcioglu O., Huang C.S., Su M.Y. Reduction of breast density following tamoxifen treatment evaluated by 3-D MRI: preliminary study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2011;29(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J.H., Nie K., Bahri S., Hsu C.C., Hsu F.T., Shih H.N., Lin M., Nalcioglu O., Su M.Y. Decrease in breast density in the contralateral normal breast of patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy: MR imaging evaluation. Radiology. 2010;255(1):44–52. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J.H., Pan W.F., Kao J., Lu J., Chen L.K., Kuo C.C., Chang C.K., Chen W.P., McLaren C.E., Bahri S. Effect of taxane-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy on fibroglandular tissue volume and percent breast density in the contralateral normal breast evaluated by 3T MR. NMR Biomed. 2013;26(12):1705–1713. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knight J.A., Blackmore K.M., Fan J., Malone K.E., John E.M., Lynch C.F., Vachon C.M., Bernstein L., Brooks J.D., Reiner A.S. The association of mammographic density with risk of contralateral breast cancer and change in density with treatment in the WECARE study. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):23. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0948-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eriksson L., He W., Eriksson M., Humphreys K., Bergh J., Hall P., Czene K. Adjuvant therapy and mammographic density changes in women with breast cancer. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;2(4):pky071. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandberg M.E., Li J., Hall P., Hartman M., dos-Santos-Silva I., Humphreys K., Czene K. Change of mammographic density predicts the risk of contralateral breast cancer--a case-control study. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(4):R57. doi: 10.1186/bcr3451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd N.F., Rommens J.M., Vogt K., Lee V., Hopper J.L., Yaffe M.J., Paterson A.D. Mammographic breast density as an intermediate phenotype for breast cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(10):798–808. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70390-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burton A., Maskarinec G., Perez-Gomez B., Vachon C., Miao H., Lajous M., Lopez-Ridaura R., Rice M., Pereira A., Garmendia M.L. Mammographic density and ageing: a collaborative pooled analysis of cross-sectional data from 22 countries worldwide. PLoS Med. 2017;14(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swain S.M., Land S.R., Ritter M.W., Costantino J.P., Cecchini R.S., Mamounas E.P., Wolmark N., Ganz P.A. Amenorrhea in premenopausal women on the doxorubicin-and-cyclophosphamide-followed-by-docetaxel arm of NSABP B-30 trial. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2009;113(2):315–320. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9937-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aktepe F., Kapucuoglu N., Pak I. The effects of chemotherapy on breast cancer tissue in locally advanced breast cancer. Histopathology. 1996;29(1):63–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1996.d01-485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eng A., Gallant Z., Shepherd J., McCormack V., Li J., Dowsett M., Vinnicombe S., Allen S., dos-Santos-Silva I. Digital mammographic density and breast cancer risk: a case-control study of six alternative density assessment methods. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(5):439. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Engmann N.J., Scott C.G., Jensen M.R., Winham S., Miglioretti D.L., Ma L., Brandt K., Mahmoudzadeh A., Whaley D.H., Hruska C. Combined effect of volumetric breast density and body mass index on breast cancer risk. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2019;177(1):165–173. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05283-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wanders J.O.P., van Gils C.H., Karssemeijer N., Holland K., Kallenberg M., Peeters P.H.M., Nielsen M., Lillholm M. The combined effect of mammographic texture and density on breast cancer risk: a cohort study. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-0961-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Houssami N., Macaskill P., von Minckwitz G., Marinovich M.L., Mamounas E. Meta-analysis of the association of breast cancer subtype and pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur J Canc. 2012;48(18):3342–3354. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertrand K.A., Tamimi R.M., Scott C.G., Jensen M.R., Pankratz V., Visscher D., Norman A., Couch F., Shepherd J., Fan B. Mammographic density and risk of breast cancer by age and tumor characteristics. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15(6):R104. doi: 10.1186/bcr3570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aiello E.J., Buist D.S., White E., Porter P.L. Association between mammographic breast density and breast cancer tumor characteristics. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2005;14(3):662–668. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moshina N., Ursin G., Hoff S.R., Akslen L.A., Roman M., Sebuodegard S., Hofvind S. Mammographic density and histopathologic characteristics of screen-detected tumors in the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Program. Acta Radiol Open. 2015;4(9) doi: 10.1177/2058460115604340. 2058460115604340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sueta A., Yamamoto Y., Hayashi M., Yamamoto S., Inao T., Ibusuki M., Murakami K., Iwase H. Clinical significance of pretherapeutic Ki67 as a predictive parameter for response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer: is it equally useful across tumor subtypes? Surgery. 2014;155(5):927–935. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshioka T., Hosoda M., Yamamoto M., Taguchi K., Hatanaka K.C., Takakuwa E., Hatanaka Y., Matsuno Y., Yamashita H. Prognostic significance of pathologic complete response and Ki67 expression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 2015;22(2):185–191. doi: 10.1007/s12282-013-0474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim K.I., Lee K.H., Kim T.R., Chun Y.S., Lee T.H., Park H.K. Ki-67 as a predictor of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients. J Breast Cancer. 2014;17(1):40–46. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2014.17.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bossuyt V., Provenzano E., Symmans W.F., Boughey J.C., Coles C., Curigliano G., Dixon J.M., Esserman L.J., Fastner G., Kuehn T. Recommendations for standardized pathological characterization of residual disease for neoadjuvant clinical trials of breast cancer by the BIG-NABCG collaboration. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(7):1280–1291. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bland J.M., Altman D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sartor H., Lang K., Rosso A., Borgquist S., Zackrisson S., Timberg P. Measuring mammographic density: comparing a fully automated volumetric assessment versus European radiologists’ qualitative classification. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(12):4354–4360. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4309-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gweon H.M., Youk J.H., Kim J.A., Son E.J. Radiologist assessment of breast density by BI-RADS categories versus fully automated volumetric assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(3):692–697. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seo J.M., Ko E.S., Han B.K., Ko E.Y., Shin J.H., Hahn S.Y. Automated volumetric breast density estimation: a comparison with visual assessment. Clin Radiol. 2013;68(7):690–695. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eriksson M., Li J., Leifland K., Czene K., Hall P. A comprehensive tool for measuring mammographic density changes over time. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2018;169(2):371–379. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4690-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldhirsch A., Wood W.C., Coates A.S., Gelber R.D., Thurlimann B., Senn H.J., Panel m. Strategies for subtypes--dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen international Expert Consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(8):1736–1747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.