Abstract

Mucinous carcinoma (MC) is a rare breast cancer characterized by the presence of large extracellular mucin amount. Two main subtypes can be distinguished: pure (PMC) and mixed (MMC).

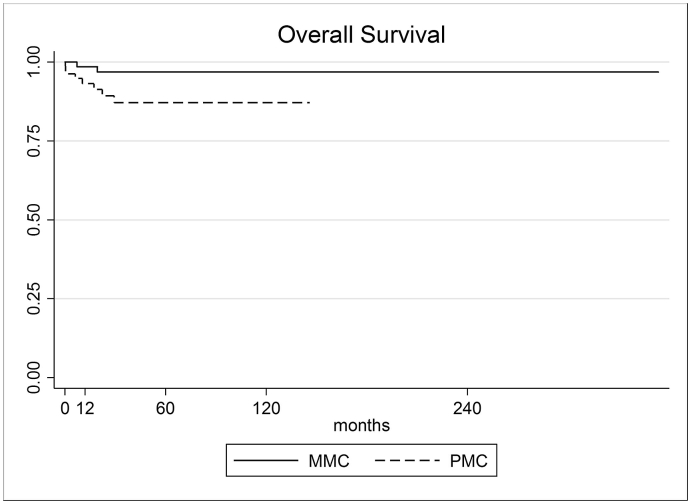

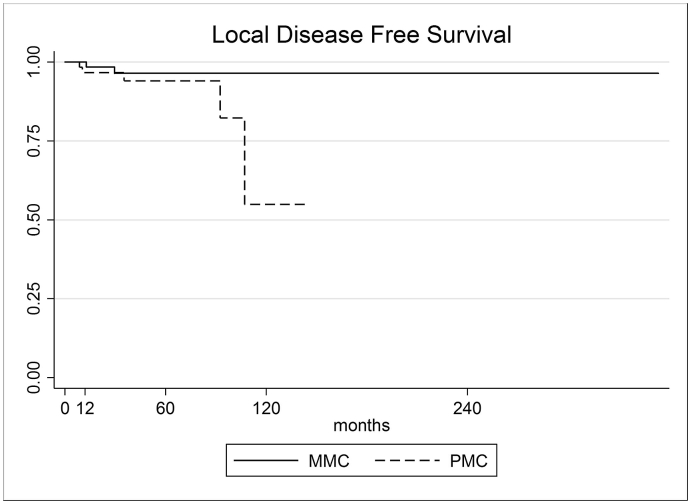

We conducted a retrospective MC analysis in our prospective maintained database, calculating disease-free survival (DFS) and 5-year overall survival (OS). We found a global 92.1% OS (higher in MMC group and statistically significative) and a DFS of 95.3% (higher in MMC group but not statistically significative).

Keywords: Mucinous carcinoma, Breast, Breast cancer, Breast surgery, Breast conserving surgery, Mastectomy, Invasive breast cancer, Breast neoplasms, Adenocarcinoma. background, Epidemiology

Highlights

-

•

Mucinous carcinoma (MC) is a rare breast cancer characterized by the presence of large extracellular mucin amount.

-

•

We conducted a literature review and conducted a retrospective analysis in our database, finding 157 cases of MC.

-

•

Our findings are consistent with those published in literature, showing fundamental differences between PMC and MMC management and outcomes.

We reviewed literature and our data to find out mucinous breast cancer's overall survival (OS), disease free survival (DFS) and if there are differences between pure mucinous breast cancer and mixed mucinous breast cancer in terms of OS and DFS.

1. Background

1.1. Epidemiology

Mucinous carcinoma (MC) represents about 4% of all invasive breast cancers [7] and results in being more common in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. It has a better prognosis compared to other breast malignant neoplasia such as ductal or lobular variants [6].

Pure mucinous breast cancer (PMC) represents about 2% of all malignant breast tumours. In a retrospective series of 11.400 PMC cases, the median age at diagnosis was 71 years versus 61 years observed in patients with infiltrative ductal carcinomas [15]. Metastatic disease rate ranges between 12% and 14% in the largest case series reported [15]. Prognosis is better than no special type breast carcinomas [10]. The 10-year survival rate is about 90.4% [16]. From a histological point of view, it is important to differentiate PMC from mixed types of ductal carcinoma with mucinous component (mixed mucinous breast cancer - MMC), which occur in only 2% of breast tumours. Interestingly, the latter have an identical prognosis compared to non-mucinous tumours [16,17]. Axillary lymph nodes are rarely involved; nevertheless, a nodal metastatic disease can worsen the survival rates and it is considered as one of the most important prognostic factors [17].

1.2. Pathology of MC

Mucinous breast carcinoma is characterized by a large amount of extracellular mucin. There are two main subtypes of MC: pure (PMC), which is more frequent, and mixed (MMC) [1]. To be defined as PMC, a carcinoma must be made up of at least 90% of mucin (intracellular or extracellular). In most cases such a cancer is both ER- and PR-positive, but AR-negative [5].

Furthermore, PMC may be classified as hypocellular (PMC-A) and hypercellular (PMC-B). The difference between these two subtypes lays in their growth pattern. Despite the hypocellular variant may have different growth patterns (tubular, cribriform, cord-like, papillary or micropapillary), the hypercellular type shows only a single pattern, spreading outward in solid nests3. The mean metastatic rate is 15% [14] and prognosis is better compared to no special type breast cancer [15]. Even if PMC has a slow growth rate, it is often diagnosed when large diameters have been reached [18]. Some Authors presume the large amount of mucin is responsible for hiding the neoplasm until large volume is reached [28].

MMC contains less than 90% of mucin with the expression of other architectures such as lobular or ductal breast cancer-like (both in situ and invasive) [2]. Lei et al. proposed that MMC may be subdivided into two groups based on the amount of mixed mucinous component [10]. According to these authors, it is possible to distinguish a partial mixed mucinous breast carcinoma or pMMC (containing < 50% of mucin) and a mixed mucinous breast carcinoma or mMMC (containing from 50% to 90% of mucin) as below detailed (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subtypes of Mucinous Breast cancer (MC).

| SUBTYPE | CHARACTERISTICS | |

|---|---|---|

| PMC | >90% OF MUCINOUS COMPONENTS | |

| PMC-A | Growth pattern: papillary, micropapillary, tubular, cord-like or cribriform | |

| PMC-B | Growth pattern: solid nests | |

| MMC | 30–90% of mucinous components | |

| pMMC | 30–50% of mucinous components | |

| mMMC | 50–90% of mucinous components | |

1.3. Diagnostic procedures

During the diagnostic phase, MC appearance may resemble a benign lesion. It usually presents with clear margins, as a round shaped mass at mammography and at ultrasound examination with a tricking isoechoic appearance alike the surrounding subcutaneous fat. For all these reasons, differential diagnosis could be challenging.

In most cases MC appears at mammography as a low-density, round or oval shaped mass, with clear edges. Tumour borders could vary from microlobulated (high mucin content) to irregular or spiculated (low mucin content). Consequently, the mucin content is correlated with peripheral characteristics [11]. In some cases, MC could be mammographically occult or showing non-mass mammographic findings, such as calcifications, occultation or focal asymmetries [12].

At ultrasound, MC appears as a round or oval mass, isoechoic or hypoechoic compared to the surrounding subcutaneous fat, often with posterior acoustic enhancement and internal echoes, with cystic or solid components [12]. Usually PMC shows heterogeneous internal echoes more frequently compared to MMC. In some cases, PMC could present sound attenuation.

At MRI MC appears as a circumscribed mass with high signal intensity in T2-weighted sections, low intensity in DWI phases, gradual and persistent enhancement and benign-appearing kinetics. Despite that, some MRI characteristics, such as the presence of internal enhancing septations and higher apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC), could help to differentiate MC from benign lesions, such as fibroadenomas and low-grade phylloides tumours [13].

Therefore, in differential diagnosis process it is important to integrate mammographic, ultrasound and MRI findings with clinical characteristics. It is also important to distinguish between PMC and MMC, since PMC usually shows a better prognosis and a lower lymph node metastatic rate.

1.4. Genetics

Other than a peculiar histologic pattern, MC has a specific molecular identity different from invasive ductal carcinoma [9]. Furthermore, MC shows a lower genetic instability compared to ductal and lobular breast cancer [8].

In a recent study, the genomic profile of 59 breast cancer samples of 10 histological special types was evaluated [23]. It resulted some of special type neoplasia characterized for having the best prognosis (not only mucinous but also adenoid cystic and tubular carcinomas with neuroendocrine features) presented with the lowest levels of gene copy number changes. Specifically, these lacked 1q gains and 16q losses, which represent hallmark features of low-grade invasive ductal carcinomas, thus suggesting that the pathways driving the carcinogenesis of these rare subtypes may be unique. This hypothesis is supported by the lack of PIK3CA and AKT1 mutations in mucinous carcinomas, in contrast with the high frequency of PIK3CA mutations in luminal breast cancers [24]. However, these characteristics could lead to specific therapeutic implications, representing the starting point for genomic studies on MC aimed to specific therapies.

Toikkanen et al. [25] highlighted another difference between MC and common ductal carcinoma. They reported almost all MCs have a normal diploid stemline unlike common ductal carcinoma. In fact, aneuploidy correlate with higher tumour grade and stage. According to these findings, Jambal et al. developed a human breast cancer cell line (BCK4), as unique model for a clearer study of the phenotypic plasticity, hormonal regulation, optimal therapeutic interventions and metastatic patterns of MC.

1.5. Treatment

Mucinous breast cancer, like other “special histology” breast cancers, often presents unique clinical behaviours.

Unfortunately, the rarity of these entities has impaired the possibility of an extensive clinical evaluation.

Most of the information on outcome and treatments comes from small series and case reports. Therefore, clear recommendations concerning clinical management are still lacking. Assessing and planning the most appropriate procedure is nonetheless crucial.

The first guideline to describe a separate treatment for “special histologic types” comes from the 2013 St. Gallen consensus conference, in which endocrine therapy was recommended for endocrine-responsive “special histological types” (i.e. mucinous) while cytotoxic therapy for endocrine-nonresponsive special types.

The 2014 NCCN Guidelines includes specific treatment recommendations for favourable mucinous histotypes. In hormone receptor-positive tumour with absence of nodal involvement, adjuvant endocrine therapy can be avoided if tumour size is less than 1 cm. If T is between 1 and 3 cm, endocrine therapy should be considered, and it is recommended for T greater than 3 cm. However, with nodal involvement endocrine therapy is indicated with or without chemotherapy.

In the current guidelines there are no significant changes on this treatment point.

From mucinous carcinoma literature we reviewed, it results clear as PMC and MMC should be considered separate entities looking at nodal involvement point of view. Even though PMC tends to remain localized, the mixed forms have a greater capacity to metastasize to lymph nodes (25% Versus 10%17 with a mean of 12–14% [21,22]). Skotnicki, in his case series [17], reported a 63% rate of pN0 specimens in PMC patients versus 30% rate of pN0 specimens in MMC patients (p < 0,05).

Despite that, the Author did not find any differences in terms of primary tumour surgical treatment (proportion of radical mastectomies: 80% in MMCs vs 78,6% in PMCs).

For this reason, looking at surgical strategies, the mixed forms often require an axillary dissection. Unfortunately, there are no available data on the exact proportion of patients underwent to axillary dissection in the two subtypes of mucinous breast cancer.

MC tumours are more frequently estrogen receptor-positive, and in the most of cases neoadjuvant chemotherapy is not proposed. Despite that, some Authors have suggested administering neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) in selected patients. In fact, the rare HER-2 overexpressing MC may be successfully treated with neoadjuvant regimens containing trastuzumab, pertuzumab, or both [26]. However, data suggesting benefits on OS and DFS are not available, because of the rarity of these cases.

In conclusion, except for HER-2 overexpressing MC, we consider surgery to be the main treatment strategy supported by adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy.

1.6. Clinical outcomes

Looking at clinical outcomes it appears clear that MC and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) could be considered as two separate entities. Overall, axillary lymph node involvement has been indicated as the most important prognostic factor. From an English literature review, several experiences elucidated this comparison in terms of DFS and OS, other than prognostic factors.

As shown by Bae et al. MC patients have better DFS than IDC patients even if OS seems to be quite similar. According to this study, adjuvant therapy and nodal status represent the most significant predictors of prognosis, more than histologic subtype [1].

MC patients, when compared to IDC ones, presented with a lower N stage, higher ER and PR expression and a more favourable histologic grade. PMC cases showed better DFS rates than those of IDC patients, but not significantly different from MMC. PMC has a better OS compared to both IDC and MMC.

On the other hand, considering the mixed-type MC patients alone, DFS compared to IDC was not significantly different. Moreover, in a stage-matched analysis for DFS and OS, MC patients showed a better survival than IDC patients [1].

Interestingly, Di Saverio et al. used tumour size as an independent prognostic factor, but it was considered a less valuable indicator when compared to nodal status and age in MC cases. In fact, according to the AJCC staging system, tumour size may not be a significant factor because of mucin, which comprises most of the tumour volume [20].

Looking at experiences reported in literature, the sample presented by Di Saverio et al. [15] may be regarded as the largest and the most relevant. In 11400 PMC patients retrospectively reviewed, the 5-year overall survival was established to be 94%, higher than IDC (82%) and the difference resulted statistically significant. In this review, the most significant prognostic factor was nodal status, followed by age, tumour size, progesterone receptors and nuclear grade. For this reason, N stage should be always assessed in patients affected by MC, except for patients with early breast cancer without expression of vascular or lymphatic invasion, in whom axillary surgical staging could be avoided [27].

In the Bae et al. [1] review, 268 patients with MC were collected and compared to 2455 patients with invasive ductal carcinoma. MC patients had a 5-year DFS rate of 95.2% (versus 92.0% of IDC), a 5-year OS of 98.9% (versus 94.9% of IDC) and overall, MC showed a better survival than IDC.

Cao et al., in 2012 [19] analysed 309 patients with PMC and found a 5-year DFS of 89%, a 5-year OS of 95%.

Tseng et al., in 2013, examined data of 93 patients with MC compared to 2674 IDC patients.

The 10-year MC overall survival rate was 94.5% versus 86.0% in IDC patients (p-value = 0.042), indicating that MC had a better long-term outcome than IDC [29].

From our literature review, OS and DFS are in line with different studies examined. When a comparison between studies is drawn, it results a mean OS of 92% and a mean DFS of 89% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of literature review in terms of 5-year DFS, 5-year OS, number of patients and median FUP

| Author | 5-year DFS | 5-year OS | No. of patients | Median FUP (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Di Saverio (2008) | NA | 94% | 11400 | NA |

| Bae SY (2011) | 95.2% | 98.9% | 268 | 49.7 |

| Cao AY (2012) | 85% | 95% | 309 | 43.3 |

| Tseng (2013) | NA | 94.5% (10years) | 93 | NA |

NA = Not Available.

Other than survival rates, it is fundamental differentiating MMC from PMC in terms of nodal involvement frequency (25% in MMC versus 10% in PMC according to Skotnicki [17]). The same group calculated ten-year DFS rates of 85.7% for PMBC and 65.0% with MMBC; the difference is statistically significant (log-rank test, p-value< 0.02).

2. Materials and methods

We retrospectively reviewed our prospectively maintained database of patients operated at Humanitas Research Hospital between 2008 and 2018 looking for the following diagnoses: pure breast cancer and mucinous breast cancer. The 5-year OS and DFS were then calculated by means of a log-rank test.

Data regarding patients and tumour characteristics, pre-operative and post-operative data were analysed with the SPSS software package. Continuous variables were presented as medians and ranges, dichotomic variables as percentages. Student's T-test was used for continuous variables, and the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Survival was estimated in terms of disease-free survival (DFS) calculated in months from surgery to recurrence and in overall survival (OS) from surgery to death or last follow-up. The two-sided significance test was used for statistical comparisons, with a p-value of ≤0.05 being considered as statistically significant. The log rank test was used to compare the survival distributions of the two groups.

3. Results

Data are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Clinicopathological characteristics of Pure Mucinous Carcinoma (PMC) and Mixed Mucinous Carcinoma (MMC) treated in Humanitas Research Hospital between 2008 and 2018.

| TOT | PMC | MMC | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 157 | 81 | 76 | |

| Age at diagnosis (mean ± DS) | 64.4 ± 15.2 | 69.1 ± 13.8 | 59.4 ± 15.0 | < 0.001 |

| Patients aged 80 or over | 18,47% | 24,69% | 11,84% | |

| Median follow-up (months) | 35 (0–353) | 29 (0–145) | 46 (0–353) | |

| OS 5-year | 92.07% (85.63%–95.70%) | 87.10% (75.39%–93.47%) | 96.84% (87.91%–99.20%) | 0.041 |

| DFS 5-year | 95.27% (88.83%–98.04%) | 94.05% (82.17%–98.10%) | 96.43% (86.31%–99.11%) | 0.182 |

| Local recurrence (number) | 8 | 5 | 3 | |

| Local recurrence (%) | 5.10% | 6.17% | 3.95% | 0.721 |

| SURGERY ON “T” |

TOT |

PMC |

MMC |

|

| BCS (num) | 123 | 72 | 51 | |

| BCS (%) | 78.34% | 88.89% | 67.11% | 0.001 |

| Mastectomy (number) | 34 | 9 | 25 | |

| Mastectomy (%) | 21.66% | 11.11% | 32.89% | 0.001 |

| Tumour diameter (mm) | 20.55 ± 16.88 | 18.75 ± 11.88 | 22.46 ± 20.85 | 0.691 |

| SURGERY ON “N” |

TOT |

PMC |

MMC |

|

| SLNB (number) | 107 | 55 | 52 | |

| SLNB (%) | 68.15% | 67.90% | 68.42% | 0.944 |

| ALND (number) | 45 | 12 | 33 | |

| ALND (%) | 28.66% | 14.81% | 43.42% | < 0.001 |

| No axillary surgery (number) | 27 | 18 | 9 | |

| No axillary surgery (%) | 17.20% | 22.22% | 11.84% | 0.095 |

| Lymph node metastases (number) | 33 | 9 | 24 | |

| Lymph node metastases (%) | 21.02% | 11.11% | 31.58% | |

| Number of examined lymph nodes (mean + range) | 16.97 (1–31) | 16.7 [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26], [27]] | 15.67 (1–31) | |

| Number of metastatic lymph nodes (mean + range) | 2.80 (1–31) | 2.7 [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]] | 2.91 [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]] | |

| OTHER TREATMENTS |

TOT |

PMC |

MMC |

|

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (n) | 30 | 6 | 24 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (%) | 19.11% | 7.41% | 31.58% | < 0.001 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (n) | 10 | 4 | 6 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (%) | 6.37% | 4.94% | 7.89% | 0.525 |

| Adjuvant hormone therapy (n) | 134 | 72.00 | 62.00 | |

| Adjuvant hormone therapy (%) | 85.35% | 88.89% | 81.58% | |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy (n) | 132 | 68 | 64 | |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy (%) | 84.08% | 83.95% | 84.21% | 0.891 |

| BIOLOGICAL PROFILE |

TOT |

PMC |

MMC |

|

| Luminal A-like (n) | 77 | 50 | 27 | |

| Luminal A (%) | 49.04% | 61.73% | 35.53% | 0.001 |

| Luminal B-like (n) | 78 | 31 | 47 | |

| Luminal B (%) | 49.68% | 38.27% | 61.84% | 0.004 |

| Her2-enriched (n) | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Her2-enriched (%) | 0.64% | 0.00% | 1.32% | 0.484 |

| Triple-negative (n) | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Triple-negative (%) | 0.64% | 0.00% | 1.32% | 0.484 |

Bold indicates Statistically significative.

From a total of 157 mucinous carcinoma cases, 81 were classified as PMC and 76 as MMC. The median follow-up was 35 months (range 1–353). The total 5-year OS was 92.1%, higher in MMC group (96.8% versus 87.1% in PMC, p-value < 0.05). The overall 5-year DFS was 95.3%, slightly higher in MMC group, but non-statistically significant (96.4% versus 94.0% in PMC group, p value = 0.182) (Fig. 1, Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Overall Survival rate of PMC and MMC.

Fig. 2.

Disease Free Survival rate of PMC and MMC.

The mean age at diagnosis was 64.4 years with PMC affecting patients earlier than MMC (69.1 versus 59.4 p-value< 0.001).

Regarding surgical treatment, most patients underwent breast conserving surgery (78.3%). Mastectomy was performed more in MMC compared with PMC patients (32.9% versus 11.1% p-value< 0.001). Data on tumour diameter showed a greater mass for MMC group (22.5 mm versus 18.7 mm), even though the difference was not statistically significant (p-value = 0.691). Focusing on axillary surgery, 68.1% of all patients underwent SLNB with almost equal percentages in the two groups (67.9% in PMC versus 68.4% in MMC) while 28.5% of the patients underwent ALND (primary or secondary to SLNB). MMC patients underwent more ALND compared with PMC patients (43.4% versus 41.8%). This reflects on the percentage of axillary metastases, which was greater in MMC patients (31.6% versus 11.1%).

Looking at adjuvant treatments, MMC patients received adjuvant chemotherapy more than PMC ones (31.6% versus 7.4%, p < 0.001). However, there was no difference between the two groups in terms of adjuvant radiotherapy received (83.9% in PMC versus 84.2% in MMCs).

Finally, for what concerns biological profile, we found almost no distinctive assessment between the two groups in terms of triple-negative or Her2-enriched types, but statistically significant difference emerged considering luminal-A profile (the majority of PMCs 61.8%, versus 35.5% of MMCs) and luminal-B one (the majority of MMCs 61.8%, versus 38.3% of MMCs).

4. Discussion

Data obtained from our caseload showed a lower 5-year OS and DFS rate compared to other clinical studies. We found a 92.0% 5-year survival rate in MC patients, probably influenced by the age of our patients. In fact, in our database the median age was 64.4 years, 18.5% of the patients were aged 80 or above (29 cases) and 18 of them (62,0%) died due to other causes. Considering subgroups, we found a better OS in MMCs list compared to PMCs one, with a statistically significant difference (p-value< 0.05). Anyway, this OS was influenced by age at diagnosis, higher in PMC patients (69.1 versus 59.4 years), particularly by the percentage of patients aged 80 or above (24.7% in PMC group and 11.8% in MMC one).

Our overall 5-year DFS was in line with data obtained by Bae et al. Between the two groups there were small, non-statistically significant differences (p-value = 0.182).

This proves once more as such a tumour presents low percentage of local recurrence: only three cases of local recurrence have been found in the MMC population (3.9%) and five cases in the PMC one (6.2%).

Regarding surgical strategies, breast conserving surgeries were the most used techniques (78.3% of all operation), particularly in PMC patients (88.9% versus 67.1%). This, mainly due to greater MMC diameters at diagnosis (22.5 mm versus 18.7 mm of PMCs) and patients age at time of diagnosis.

According to the published data, MMC has a greater capacity to metastasize to the lymph nodes. This was confirmed by our experience: 43.4% of MMC patients underwent ALND compared to 14.8% of PMC patients (p-value < 0.001) and in 31.6% we found axillary node metastases (compared to 11.1% of PMC patients, p-value< 0.001). However, the mean number of metastatic lymph nodes did not differ greatly between the two groups (2.9 in MMC patients and 2.7 in PMC patients).

Concluding with biological profiles, it is clear as the low percentage of Her2-enriched and triple-negative tumours influenced oncologic treatment. In fact, only 6.4% of the patients underwent neoadjuvant treatment. In the two groups, we found significant differences regarding luminal-A and luminal-B tumours: the former were more frequent in PMC cases (61.7% versus 35.5%, p-value < 0.001), the latter were more frequent in MMC patients (61.8% vs 38.3%, p-value < 0.05). This influenced therapeutic decisions: adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 31.6% of MMC patients but only to 7.4% of PMC patients. On the other hand, both PMCs and MMCs got hormone treatment in most cases (88.9% in the PMC group and 81.6% in the MMC group).

5. Conclusion

Our findings are consistent with those published in literature, showing fundamental differences between PMC and MMC management and outcomes. These characteristics influence prognosis and treatment strategies. Unfortunately, in such cases, no tailored therapies are present, but clinical MC behaviour often leads to effective treatment strategies. Even if genetic studies lead to some interesting differences between MC and no-special type breast cancer, these seem lacking specific therapeutic implications, even if further genomic studies could help developing targeted therapies in such rare breast cancer subtype.

Without any doubt, despite low incidence and information on MC, a deeper knowledge is needed to obtain better survival rates.

Declaration of interests

All contributing authors have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence or bias the current work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in relation to this work.

References

- 1.Bae S.Y., Choi M.Y., Cho D.H., Lee J.E., Nam S.J., Yang J.H. Mucinous carcinoma of the breast in comparison with invasive ductal carcinoma: clinicopathologic characteristics and prognosis. J Breast Cancer. 2011;14:308–313. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2011.14.4.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanagiri T., Ono K., Baba T., So T., Yamasaki M., Nagata Y. Clinicopathologic characteristics of mucinous carcinoma of the breast. Int Surg. 2010;95:126–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kashiwagi S., Onoda N., Asano Y., Noda S., Kawajiri H., Takashima T. Clinical significance of the sub-classification of 71 cases mucinous breastcarcinoma. SpringerPlus. 2013;2:481. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komaki K., Sakamoto G., Sugano H., Morimoto T., Monden Y. Mucinous carcinoma of the breast in Japan. A prognostic analysis based on morphologic features. Cancer. 1988;61:989–996. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880301)61:5<989::aid-cncr2820610522>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lakhani S.R., Ellis I.O., Schnitt S.J., Tan P.H., van de Vijver M.J. World health organization classification of tumours. fourth ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2012. WHO classification of tumours of the breast; pp. 60–61. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C.I. Risk of mortality by histologic type of breast cancer in the United States. Horm. Cancer. 2010;1:156–165. doi: 10.1007/s12672-010-0016-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson W.F., Chu K.C., Chang S., Sherman M.E. Comparison of age-specific incidence rate patterns for different histopathologic types of breast carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2004;13:1128–1135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lacroix-Triki M., Suarez P.H., MacKay A., Lambros M.B., Natrajan R., Savage K. Mucinous carcinoma of the breast is genomically distinct from invasive ductal carcinomas of no special type. J Pathol. 2010;222:282–298. doi: 10.1002/path.2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujii H., Anbazhagan R., Bornman D.M., Garrett E.S., Perlman E., Gabrielson E. Mucinous cancers have fewer genomic alterations than more common classes of breast cancer. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2002;76:255–260. doi: 10.1023/a:1020808020873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lei L., Yu X., Chen B., Chen Z., Wang X. Clinicopathological characteristics of mucinous breast cancer: a retrospective analysis of a 10-year study. PLoS One. 2016;11(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memis A., Ozdemir N., Parildar M., Ustun E.E., Erhan Y. Mucinous (colloid) breast cancer: mammographic and US features with histologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2000;35:39–43. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(99)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu H., Tan H., Cheng Y., Zhang X., Gu Y., Peng W. Imaging findings in mucinous breast carcinoma and correlating factors. Eur J Radiol. 2010 Dec;80(3):706–712. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bitencourt A.G.V., Graziano L., Osório C.A.B.T., Guatelli C.S., Souza J.A., Mendonça M.H.S., Marques E.F. MRI features of mucinous cancer of the breast: correlation with pathologic findings and other imaging methods. Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206(2):238–246. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranade A., Batra R., Sandhu G., Chitale R.A., Balderacchi J. Clinicopathological evaluation of 100 cases of mucinous carcinoma of breast with emphasis on axillary staging and special reference to a micropapillary pattern. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:1043–1047. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.082495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Saverio S., Gutierrez J., Avisar E. A retrospective review with long term follow up of 11,400 cases of pure mucinous breast carcinoma. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2008;111:541–547. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9809-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Komaki K., Sakamoto G., Sugano H., Morimoto T., Monden Y. Mucinous carcinoma of the breast in Japan. A prognostic analysis based on morphologic features. Cancer. 1988;61:989–996. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880301)61:5<989::aid-cncr2820610522>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skotnicki P; Sas-Korczynska B; Strzepek L; Jakubowicz J; Blecharz P; Reinfuss M; Walasek T. Pure and mixed mucinous carcinoma of the breast: a comparison of clinical outcomes and treatment results. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Lannigan A.K. Mucinous breast carcinoma. Breast. 2002;11:359–361. doi: 10.1054/brst.2002.0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao A.-Y., He M., Liu Z.-B., Di G.-H., Wu J., Lu J.-S., …, Shao Z.-M. Outcome of pure mucinous breast carcinoma compared to infiltrating ductal carcinoma: a population-based study from China. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(9):3019–3027. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Komenaka I.K., El-Tamer M.B., Troxel A., Hamele-Bena D. Pure mucinous carcinoma of the breast. Am J Surg. 2004;187:528–532. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diab S.G., Clark G.M., Osborne C.K. Tumour characteristics and clinical outcome of tubular and mucinous breast carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1442–1448. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vo T., Xing Y., Meric-Bernstam F. Long-term outcomes in patients with mucinous, medullary, tubular, and invasive ductal carcinomas after lumpectomy. Am J Surg. 2007;194:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horlings H.M., Weigelt B., Anderson E.M. Genomic profiling of histological special types of breast cancer. Breast Canc Res Treat. 2013;142:257–269. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dieci MV; Orvieto E; Dominici M, Conte P, Guarnieri V. Rare breast cancer subtypes: histological, molecular, and clinical peculiarities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Toikkanen S., Eerola E., Ekfors T.O. Pure and mixed mucinous breast carcinomas: DNA stemline and prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:300–303. doi: 10.1136/jcp.41.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Didonato R., Shapiro N., Koenigsberg T., D'Alfonso T., Jaffer S., Fineberg S. Invasive mucinous carcinoma of the breast and response patterns after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) Histopathology. 2018;72(6):965–973. doi: 10.1111/his.13451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marrazzo A., Boscaino G., Marrazzo E., Taormina P., Toesca A. Breast cancer subtypes can be determinant in the decision making process to avoid surgical axillary staging: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;21:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.07.702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fentiman I.S., Mills R.R., Smith P., Ellul J.P., Lampejo O. Mucoid breast carcinomas: histology and prognosis. Br J Canc. 1997;75:1061–1065. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tseng H.-S., Lin C., Chan S.-E., Chien S.-Y., Kuo S.-J., Chen S.-T., …, Chen D.-R. Pure mucinous carcinoma of the breast: clinicopathologic characteristics and long-term outcome among Taiwanese women. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11(1):139. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]