Abstract

This article is an update of the requirements of a specialist breast centre, produced by EUSOMA and endorsed by ECCO as part of Essential Requirements for Quality Cancer Care (ERQCC) programme, and ESMO.

To meet aspirations for comprehensive cancer control, healthcare organisations must consider the requirements in this article, paying particular attention to multidisciplinarity and patient-centred pathways from diagnosis, to treatment, to survivorship.

-

•

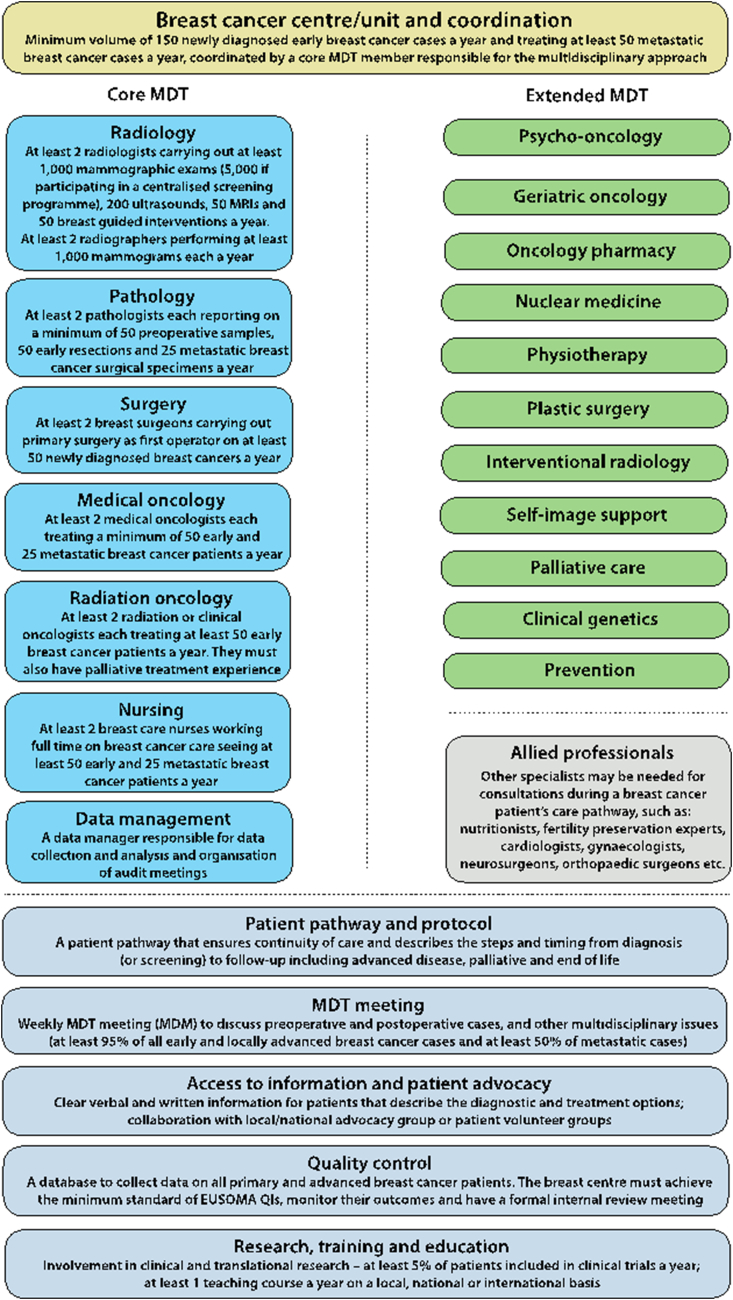

The centrepiece of this article is the requirements section, comprising definitions; multidisciplinary structure; minimum case, procedure and staffing volumes; and detailed descriptions of the skills of, and resources needed by, members and specialisms in the multidisciplinary team in a breast centre.

-

•

These requirements are positioned within narrative on European breast cancer epidemiology, the standard of care, challenges to delivering this standard, and supporting evidence, to enable a broad audience to appreciate the importance of establishing these requirements in specialist breast centres.

1. Introduction: The need for quality frameworks

There has been a growing emphasis on driving up quality in cancer organisations in order to optimise patients outcomes. The European Cancer Concord (ECC), a partnership of patients, advocates and cancer professionals, has recognised major disparities in the quality of cancer management and in the degree of funding in Europe, and has launched a European Cancer Patient’s Bill of Rights, a patient charter that underpins equitable access to optimal cancer control, cancer care and research for Europe’s citizens [1].

It follows an assessment of the quality of cancer care in Europe as part of the first EU Joint Action on Cancer, the European Partnership for Action Against Cancer (EPAAC, http://www.epaac.eu), which reported in 2014 that there are important variations in service delivery between and within countries, with repercussions in quality of care. Factors such as waiting times and provision of optimal treatment can explain about a third of the differences in cancer survival, while lack of cancer plans, for example a national cancer plan that promotes clinical guidelines, professional training and quality control measures, may be responsible for a quarter of the survival differences.

The EU Joint Action on Cancer Control (CANCON), which replaced EPAAC from 2014, also focused on quality of cancer care and in 2017 published the European Guide on Quality Improvement in Comprehensive Cancer Control. [2] This recognised that many cancer patients are treated in general hospitals and not in comprehensive cancer centres (CCCs) and explores a model of ‘comprehensive cancer care networks’ that can integrate expertise under a single governance structure. Research also shows that care provided by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) result in better clinical and organisational outcomes for patients [3].

Countries have been concentrating expertise for certain tumour types in such networks and in dedicated centres, or units, such as for childhood and rare cancers, and all CCCs have teams for the main cancer types. For common adult tumours, however, at the European level there has been widespread effort to establish universal, dedicated units only for breast cancer, following several European declarations that set a target of the year 2016 for care of all women and men with breast cancer to be delivered in specialist multidisciplinary centres. While this target was not met, as detailed in a European Breast Cancer Council manifesto calling for universal breast unitsa [4], the view of the ERQCC expert group is that healthcare systems must strive to adopt the principles of such dedicated care for all types of cancer.

1.1. Breast cancer

There is a 20-year history in Europe of calling for, and developing, specialist breast cancer units. In the year 2000, the European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) published a position paper, ‘The requirements of a specialist breast unit’, which was the first to set out standards for establishing high-quality breast cancer centres or units across Europe [5]. The paper followed a consensus statement drawn up at the first European Breast Cancer Conference in Florence in 1998 that demanded that, ‘Those responsible for organising and funding breast cancer care ensure that all women have access to fully equipped multidisciplinary and multiprofessional breast clinics based on population numbers of around 250,000.’ [6] The statement was based on a growing body of evidence that optimal care for breast cancer patients can only be obtained by an MDT, preferably based at one location.

In the following years, European Parliament resolutions and declarations have called for universal breast cancer units or centres in Europe [7,8], while a number of papers and documents have developed quality standards and EUSOMA has refined the requirements [9], which were also included in the European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis [10].

This paper is an update of the EUSOMA requirements paper, endorsed by the European CanCer Organisation (ECCO) as part of its Essential Requirements for Quality Cancer Care (ERQCC) programme, and by the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO).

This update has a wider quality context, adding narrative on epidemiology, challenges in breast cancer care, and quality and audit processes and examples, in addition to the components of a breast centre. It is based on the changes in organisation and care over the past 5 years as detailed by representatives of the disciplines working in breast cancer care.

The definition of the breast centre (or unit) that applies throughout this paper is: The place where breast cancer is diagnosed and treated; it has to provide all the services necessary, from genetics and prevention, through the treatment of the primary tumour, to care of advanced disease, supportive and palliative care and survivorship, and psychosocial support.

2. Breast cancer: Key facts and challenges

2.1. Key facts

2.1.1. Epidemiology

-

•

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in the European Union and a rare cancer in men. It comprises a wide range of histopathological subtypes, the most common being invasive carcinoma of no special type (NST), previously named invasive ductal carcinoma, and invasive lobular carcinoma [11]. Much less common are all the other histological subtypes. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), where cancer cells are only in the glandular tree, is a pre-malignant condition that may lead to invasive breast cancer. Nowadays, breast cancer is also classified into molecular subtypes, namely luminal A and B, HER2-positive and basal. Due to logistical and financial reasons, surrogate subtypes are mainly used in clinical practice – hormone receptor and HER2 receptor status, and a proliferation measure (usually Ki67). Oestrogen-positive (ER+)/HER2-negative breast cancer is the most common subtype, comprising about 70% of cases.

-

•

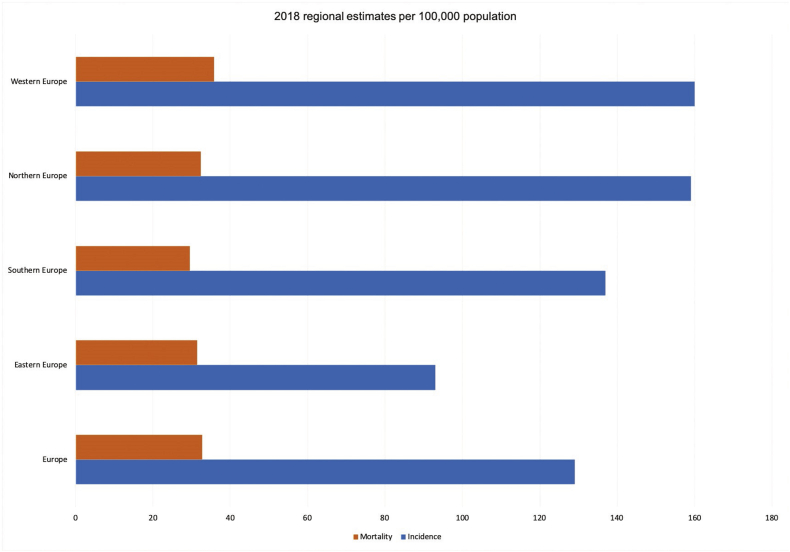

Breast cancer incidence varies across European countries but overall the lifetime risk is about 1 in 10 for women. Breast cancer is a substantial health burden on society, and has been estimated to cost about 13% of the total cancer healthcare costs in the EU, the highest of any cancer, and second in overall economic burden after lung cancer [12]. The estimated incidence of breast cancer in 2018 in Europe (EU 28 + European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries) was about 416,000 with a European age standardised rate of 145/100,000) [13]. Estimated incidence was highest in Belgium (204/100,000), Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the lowest in Romania (90/100,000) and Poland; generally, incidence is lower in Southern and Eastern Europe, but data from these countries might be incomplete due to issues with cancer registries. Estimated mortality in 2018 was about 100,000, with the highest European age standardised rates in Croatia (43/100,000), Iceland and Ireland, and the lowest in Spain (23/100,000), Finland and Norway (see Fig. 1).

-

•

There are high survival rates for breast cancer in Europe. The EUROCARE-5 study, the latest in the series, reports the 5-year relative survival rate in 2000–2007 at 82%, ranging from 74% (Eastern Europe) to 85% (Northern Europe), and survival increased during the study period [14]. Survival was uniformly higher for women in countries with population breast cancer screening. The 5-year relative survival was highest in the 45–54 and 55–64 year age groups and declined in older patients.

-

•

Breast cancer mortality rates have declined in the European Union and are predicted to fall further, with the largest falls in young women (20–49 years, −22% between 2002 and 2012) [15]. The fall in mortality is said to be mainly due to improvements in the management and treatment of breast cancer, although early diagnosis and screening are also important. Improving breast cancer management in Central and Eastern Europe is a particular priority [15].

-

•

It is important to note that there has been little progress in extending the median survival of patients with advanced or metastatic (stage 4) breast cancer, which remains at about 3 years, although longer survival may be seen particularly in the HER2-positive subtype [[16], [17], [18]].

Fig. 1.

European breast cancer mortality and incidence

Source: European Cancer Information System. European age standardised rates.

2.1.2. Risk factors

-

•

Risk factors for breast cancer in women include older age, family history, previous benign breast disease, and a previous breast cancer diagnosis. In addition, several hormonal factors, particularly those that expose women to more menstrual cycles, play a role in increasing risk, including early menstrual periods, late menopause, less (and later) childbirths and less breast feeding.

-

•

Pathological germline variants in the BRCA1/2 genes can greatly increase risk; other gene variants can also add variable risk. Women with dense breasts are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer.

-

•

Preventable risk factors include overweight/obesity, lack of physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption. Hormonal replacement therapy increases risk. Women who have had radiation therapy to the chest or breast as treatment for other cancers (i.e. lymphoma) are also at increased risk.

-

•

Risk factors for breast cancer in men include older age, family history, BRCA1/2 variants (especially in BRCA2), gynecomastia, heavy alcohol intake, liver disease, obesity and radiation exposure.

2.1.3. Diagnosis and treatment

Note key ESMO and ESO-ESMO guideline references for diagnosis, treatment and care of early breast cancer [19] and advanced breast cancer. [20].

-

•

Breast cancer is one of only three cancers where there is robust evidence for the benefit of population screening (cervical and colorectal are the other two) and most European countries have introduced mammographic screening programmes, most commonly screening women between the ages of 50 and 70 at 2 year intervals to primarily detect small tumours that cause no symptoms. However, about an equivalent number of breast cancers are detected by self-examination for breast lumps and other symptoms including a change in the size or shape of a breast, dimpling of skin, inverted nipple, nipple rash and discharge, and a swelling or lump in the armpit. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which is a non-invasive pre-malignant condition, may be asymptomatic or associated with a lump and is detected by mammography (usually through the presence of abnormal microcalcifications).

-

•

Diagnosis should be made by a ‘triple assessment’, comprising clinical assessment (patient history and physical examination), mammography and/or ultrasound imaging, and a biopsy (a core needle biopsy is necessary; a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is insufficient and should not be performed in the breast, since it has a high rate of false results and does not allow for adequate biomarker characterisation). Ultrasound is also used to image the axilla (armpit area) for affected lymph nodes, as a common site of spread are ipsilateral axillary nodes, and a biopsy/FNA taken if involvement is suspected; if not suspected, to rule out spread to the nodes, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is a surgical procedure that has become the standard of care to identify the first node(s) that could be involved in early breast cancer. Breast cancer is commonly staged according to the TNM system and graded for cell differentiation (nuclear atypia and proliferation) and tubule formation. All invasive breast cancer should be assessed for ER, progesterone (PgR) and HER2 receptor status. The distinction between low and high-grade DCIS and invasive cancer is also important.

-

•

Genetic testing for the BRCA 1/2 mutations is recommended in certain cases as it has implications for clinical management [21].

-

•

Early invasive and locally advanced breast cancer are treated with curative intent. Local treatments include surgery (breast-conserving surgery (BCS) or mastectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection) and radiation therapy. Systemic therapy options include chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, HER2 targeted therapy and bisphosphonates, according to risk of relapse and receptor status, and can be offered before (primary systemic therapy, also known as neoadjuvant or preoperative) and/or after surgery (adjuvant therapy).

-

•

Primary systemic therapy is being used increasingly in higher risk biological subtypes (e.g. triple negative and HER2-positive) even in cases where BCS would be possible upfront, since this strategy enables personalisation of therapy based on response and facilitates prediction of prognosis for individuals based on pathological response. Primary systemic therapy is the recommended strategy for locally advanced breast cancer and inflammatory breast cancer. For locally advanced disease, surgical treatment varies depending on characteristics at diagnosis and response to therapy, while for inflammatory breast cancer, mastectomy and axillary dissection, followed by radiation therapy, is usually necessary even in the presence of a good response to primary systemic therapy.

-

•

Tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors are approved endocrine agents for ER + early breast cancer. Ovarian ablation (removal of the ovaries) or suppression of oestrogen with drugs may also be offered to some premenopausal women with ER + cancer.

-

•

BCS followed by breast irradiation (plus endocrine therapy in some cases) is the preferred treatment for most DCIS patients, though widespread DCIS may well require treatment by mastectomy. Radiotherapy may be avoided in selected cases, i.e. low grade DCIS.

-

•

Mastectomy or BCS with sentinel lymph node biopsy or axillary dissection and a similar range of medical and radiation therapy options are used for male breast cancer. Aromatase inhibitors alone should not be used for early breast cancer in male patients [22].

-

•

Systemic therapy with endocrine therapy, chemotherapy and targeted therapy is the strategy of choice in advanced/metastatic breast cancer. The choice of systemic therapy depends on many factors, including the biology of the tumour, the burden of metastatic disease, symptoms, performance status, comorbidities, socioeconomic factors and patient preferences. Early and continuous appropriate supportive, palliative and psychosocial support are indispensable throughout the management of advanced/metastatic disease.

-

•

Surgery, radiation therapy and interventional radiology are important to treat certain conditions, such as brain or bone metastases, to prevent bone fractures and relieve pain. In highly selected de novo (i.e. diagnosed already as stage 4) metastatic cases, locoregional therapy of the primary tumour, with surgery and/or radiation therapy, may also be performed.

2.2. Challenges in breast cancer care

2.2.1. Screening and detection

-

•

Mammography screening services are often separate from breast treatment centres, missing opportunities for multiprofessional working in assessment and diagnosis.

-

•

There has been wide publicity given to controversy about the benefits and harms of population-based mammography screening, which is one of the flagship health screening programmes in many countries. Women must be given information that allows them to make informed choices about participation in these programmes.

-

•

Education on breast health awareness is often lacking in countries and should target girls at school as well as adult women.

-

•

In view of exponential increase in cancer incidence, primary care physicians must be involved in many steps of the cancer journey, starting with screening and early diagnosis [23]. It is essential to promote close collaboration between these specialists and breast centres for a fast referral.

2.2.2. Staging and grading

-

•There are concerns about the quality of breast cancer pathology services in Europe:

-

–They can vary to a considerable extent in the accuracy of assessing parameters important for treatment decision-making; few countries are monitoring and assessing this variability

-

–Most pathology departments are general and may lack pathologists experienced in the increasingly complex area of breast pathology and may also lack sufficient volume of cases to develop and maintain expertise

-

–In many countries there is a shortage of pathologists.

-

–Availability of intra-operative pathology assessment is crucial to substantially decrease the rate of re-interventions.

-

–

A manifesto by the European Breast Cancer Council addressed these concerns [24].

2.2.3. Early breast cancer – treatment and support

-

•A wide range of shortcomings and challenges in care result from a lack of multidisciplinary breast centres:

-

–Overtreatment in all areas (surgery, radiation and medical therapies), often related to outdated reimbursement rules

-

–Underuse of treatments such as primary systemic therapy

-

–Lack of surgical expertise and experience has led to too many mastectomies, too many axillary dissections and too many re-interventions

-

–Lack of expertise and experience in breast radiation and medical therapies

-

–Lack of oncoplastic/reconstructive expertise.

-

–

-

•

Choosing the right treatment among an increasingly complex range of options has become a major challenge for patients and it is important that balanced advice is given by all breast specialists.

-

•

There is a lack of dedicated breast nurses and patient navigators who can help guide patients through this complex care pathway. Breast care nurses are in place in only a few European countries at present. Developing breast care nursing is important to offer optimised care for patients [25,26] and studies have shown that specialist nurses improve patient outcomes [27,28]. They are essential members of the core MDT.

-

•

There is a lack of adequate supportive and psychological support. About one third of breast cancer patients experience high levels of emotional distress [[29], [30], [31]], and about half report increased levels of depression and anxiety in the year after diagnosis [32].

-

•

Side-effects from treatments are often not adequately managed.

-

•

There is a lack of data on treatment of older patients and very young patients. Although about 20% of breast cancer occurs in patients 75 years old or older, there is a lack of data on management of older patients, especially those who are frail and vulnerable. Chronological age alone must not be used to withhold effective therapies [33].

2.2.4. Advanced breast cancer (includes inoperable locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer) – treatment and support

-

•

In Europe, most advanced breast cancer patients are still treated outside of MDTs, by medical oncologists alone. Treating advanced disease in specialised breast units/centres increases access to treatment according to international guidelines, loco-regional management of certain types of metastases, correct management of symptoms and side-effects of therapies, inclusion in clinical trials, and early links to psychosocial supportive and palliative care, all of which are associated with higher quality of care and improved outcomes.

-

•

Treatment is complex, can be costly, and often involves multiple lines of therapy with periods of good quality of life between treatment spells, with several agents approved in recent years. Issues of accessibility to optimal treatment options (e.g. cancer medicines, radiation therapy) are crucial and access is highly uneven between countries and within each country (see 2.2.7 Inequalities, below). Management of advanced disease in breast centres can centralise and optimise access in a cost-effective manner.

2.2.5. Support services and survivorship

-

•

Many breast cancer patients are of working age or have dependants or children and may suffer financial loss as a result of treatment related incapacity. Social support to aid in financial and other difficulties may be required but hard to obtain.

-

•

Services are often also required to help manage secondary effects from treatments that affect quality of life, such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy (rehabilitation), nutritional counselling and psycho-oncology, but there may be gaps in provision, particularly when these services are best delivered in the community in partnership with breast centres.

-

•

As more patients are being diagnosed at a fertile age, and before they have completed their families, fertility preservation is crucial and should be part of the breast centre’s services.

-

•

Advanced breast cancer patients face a range of survivorship issues such as isolation, lack of information and financial hardship.

2.2.6. Genetic testing

-

•

There are well-established protocols for testing women at high risk of breast cancer, such as Ashkenazi Jews or those with many affected family members for variants of the BRCA1/2 genes, but there is rapidly developing research on lesser risk genes and also in the most common genetic variants, SNPs [21,34]. The rapid rise in commercial tests and in research on genetic breast cancer risk is placing pressure on clinical genetics services and on the knowledge base of other health professionals.

-

•

In particular, there is a major challenge in uncontrolled and sub-standard tests that can raise anxiety and raise demand for counselling, and even lead to unnecessary treatment, as set out in the 2018 European Breast Cancer Council manifesto [35].

2.2.7. Inequalities

-

•

Women with higher socioeconomic status in Europe have a higher breast cancer incidence but lower mortality than women in lower status groups [36]. While higher incidence is linked to reproductive factors, hormonal replacement therapy and higher use of opportunistic screening, lower fatality seems to be explained by earlier stage of diagnosis, and access to optimal treatment. A report from England also shows that socio-economically advantaged women are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer, and finds that there are geographical variations, as women living in disadvantaged areas are more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage with a lower chance of survival [37].

-

•

The same report from England also found inequalities related to black and ethnic minority status, which are also likely to be seen in other parts of Europe [37].

-

•

There is evidence than many older women (over 70) are not offered the same standard of care as younger patients despite being eligible for treatment (see for example the National Audit for Breast Cancer in Older Patients (NABCOP) on services in England and Wales – (https://www.nabcop.org.uk). They are also more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage.

-

•

There is also evidence that quality of care for male patients with breast cancer is lower than for their female counterparts [38].

-

•

There are substantial inequalities in access to treatment among and within European countries. Some Eastern European countries, especially, have shortcomings in radiation therapy and drug availability, including inexpensive breast cancer drugs such as tamoxifen as well as expensive new therapies, some of which are listed by WHO as essential medicines, although lack of access could be due to organisational and not only financial constraints. The use of international guidelines (which recommend cost-effective therapies) and new tools to objectively evaluate benefit and prioritise effective therapies (such as the ESMO Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale) [39] are potential solutions. The shortage of cancer medicines was highlighted in a report from the Economist Intelligence Unit in collaboration with ESMO, and needs to be urgently tackled [40].

2.2.8. Research

-

•

Conducting research, in particular clinical research, is associated with better outcomes for patients and should be included in the services provided by the breast centre. Currently, clinical research in some European countries is oriented towards industry sponsored studies, especially those funded by pharmaceutical companies, and academic research must be supported by independent sources of funding, as called for by the Clinical Academic Cancer Research Forum [41].

-

•

Evidence suggests that clinical research in Europe is not oriented towards investigation of antineoplastic drugs effect on endpoints that are most important to patients (i.e. improvements in quality of life, reduction of risk of recurrence for the early stages of the disease, and life prolongation for advanced disease) [42]. Therefore, a cornerstone of research should be to investigate the impact of intervention on endpoints that are patient oriented. In addition, clinical research should provide evidence of interventions’ efficacy and safety from real life data, to confirm/question results from clinical trials.

-

•Important research topics in breast cancer include [43].

-

–Earlier diagnosis, apart from screening

-

–Novel methodology with adaptive trial designs within platforms and validation of novel biomarkers of early response

-

–Predictive factors and therapy individualisation

-

–Escalation and de-escalation of therapy in early breast cancer

-

–Identification of treatment strategies that optimise patients’ quality of life without loss of quantity.

-

–

-

•

There is an urgent need to increase research in patient groups that are under-represented and under-researched in breast cancer studies, particularly older and young women, and men.

-

•

There is a pressing need for the development and incorporation of patient reported outcomes/measures (PROs/PROMs), and research on quality of life and survivorship.

-

•

Patient advocacy groups are valuable partners in all aspects of breast cancer research, from epidemiology to treatments to survivorship, and should be involved in all stages of research.

2.2.9. Cancer registration and data availability

-

•

Cancer registration practice, coverage and quality are highly unequal across Europe [44]. Consequently, basic epidemiological data on incidence, mortality and survival are not uniformly available for all countries. Also, only a minority of cancer registries can provide sufficient data for the calculation of parameters necessary for the assessment of outcomes and quality of care [45].

-

•

A particular shortcoming in breast cancer is that few cancer registries collect data on recurrences, including distant, which means that there are only estimates of the number of patients living with incurable disease. This makes it hard for healthcare services and wider society to allocate resources for one of the largest populations of advanced cancer patients.

-

•

There is a need to find ways of improving quality of nationally/internationally collected routine data so it can be embedded within clinical trials as outcome data.

-

•

Cancer registries in Europe should be compatible with each other to analyse data collectively.

-

•

Registries and/or other forms of real-world data should include data on the effects on treatment outcomes of the use of OTC (over the counter) medicines or CAM (complementary alternative medicines), which are commonly used by cancer patients [46].

-

•

In addition, registries and/or other forms of real-world data should allow for the assessment of the true benefit of cancer therapies, evaluating whether results from clinical trials are translated into the real-life setting for efficacy and safety. This could also benefit the evaluation of efficacy and safety profile of the population unrepresented in randomised clinical trials.

3. Breast centre: Definitions

Breast centre: The place where breast cancer is diagnosed and treated. It has to provide all the services necessary, from genetics and prevention, through the treatment of the primary tumour, to care of advanced disease, supportive and palliative care, survivorship and psychosocial support.

The breast centre comprises a group of dedicated breast cancer specialists working together as a multidisciplinary team (MDT) with access to all the facilities required to deliver high-quality care throughout the breast cancer pathway.

Preferably, all services should be in the same facility, limiting to a minimum the need for the patient to travel between locations. Therefore breast centres are encouraged to be organised in one location. However, when for organisational reasons this is not possible, some services may be based at different locations but must be in the same geographical area, and protocols must be in place for the optimal integration of care, guaranteeing multidisciplinary work and timely access, and all sites must share the same database for quality assurance and research.

Protocols: Official procedures or systems of rules, including local organisational aspects, for the diagnosis and management of breast cancer at all stages, including surveillance and long-term follow-up.

Breast data audit: Evaluation of quality indicators to identify corrective actions through multidisciplinary discussion.

Formal internal review meeting: Evaluation of performance on quality indicators, organisational and clinical aspects, audit results, identification and implementation of corrective actions.

Breast multidisciplinary meeting (MDM): Where the core MDT meets to evaluate and plan patient care at any step of the diagnostic and treatment process.

Breast clinic: A session at which a number of breast patients are seen for clinical examination and/or investigations, counselling, etc.

Breast specialist: A person certified in her/his own discipline and fully trained in management of breast cancer.

Breast core MDT members: Breast specialists who are essential for diagnosis and care of breast cancer, who spend the majority of their working time in breast cancer and who must participate in MDM (except for radiographers, who are part of core team but are not requested to attend the MDM). These specialisms are detailed in the essential requirements in section 5:

-

•

Breast radiologist: board-certified specialist in imaging with expertise in breast cancer diagnosis (including diagnostic interventional procedures), further assessment and follow-up

-

•

Breast radiographer: technician specialised in breast imaging examination

-

•

Breast pathologist: board-certified pathologist with expertise in breast disease

-

•

Breast surgeon: board-certified surgeon with expertise in breast surgery including oncoplastic procedures. In some centres this role may be shared by a breast cancer surgeon and a reconstructive surgeon working together.

-

•

Breast medical oncologist: board-certified medical oncologist with expertise in breast cancer. In some countries (e.g. Germany), systemic therapy for breast cancer patients is currently delivered by organ specialists such as gynaecologists, but the goal is that, in the near future, systemic therapy is only delivered by medical oncologists. It is crucial that any specialist who now delivers systemic therapy has training defined by the ESMO-ASCO Global Curriculum for Medical Oncology [47].

-

•

Breast radiation oncologist: board-certified radiation oncologist with expertise in breast cancer or

Breast clinical oncologist: in some countries (such as the Nordics and the UK) clinical oncologists are professionals who are board-certified in both radiation and medical treatments, but must be dedicated to breast cancer.

-

•

Breast care nurse: a nurse with specialist training in breast care nursing

-

•

Breast data manager: person responsible for breast cancer data management (detailed in section 4.10).

Extended MTD members: Specialists who are consulted during breast cancer care and treatment, but are not routinely involved in breast cancer care for every patient. These specialisms are detailed in the essential requirements in section 6:

-

•

Psycho-oncologist: professional who identifies distress and psychological morbidity and provides psychological interventions to breast cancer patients and their families

-

•

Geriatric oncologist/geriatrician: geriatrician with cancer expertise who applies geriatric assessment for appropriate treatment

-

•

Oncology pharmacist: pharmacist with expertise in cancer medicines

-

•

Nuclear medicine physician: board-certified nuclear medicine specialist with expertise in the management of breast cancer patients, including sentinel lymph-node technique, molecular imaging and theranostics

-

•

Physiotherapist: professional who provides physical support of patients after breast cancer therapies (breast surgery and radiotherapy)

-

•

Plastic surgeon: board-certified plastic surgeon with expertise in breast reconstruction techniques

-

•

Interventional radiologist: board certified specialist who carries out interventional radiology techniques, such as biopsies of metastatic lesions and local management of some types of breast cancer metastases such as bone metastases

-

•

Self-image professional: a specialist in breast or hair prosthesis

-

•

Palliative care specialist: specialist who provides physical, psychosocial and spiritual care to patients who have, or may soon have, severe symptoms and distress from advanced disease

-

•

Clinical geneticist: medical specialist concerned with the assessment of genetic risk and counselling for individuals and families with increased risk of breast cancer

-

•

Primary prevention professionals: specialists with expertise in physical exercise, diet and lifestyle counselling.

All members of the breast centre should have knowledge and skills to provide basic psychological care and screen for distress. Qualified care providers other than nurses (e.g. radiation technologists) also provide links between patients and the breast team.

To guarantee the availability of other specialists who may be needed for consultations during a breast cancer patient’s care pathway, such as nutritionists, fertility preservation experts, cardiologists, gynaecologists, neuro-surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons etc., the breast centre must have established working arrangements which allow immediate and effective consultation.

4. Breast centre requirements

4.1. Breast centre

There must be a formal document (that complies with any national regulations) which describes organisation of the breast centre and which could include its relationship within the wider cancer infrastructure such as the cancer centre and regional cancer network (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Breast cancer centre schematic.

4.2. Critical mass

-

•

A breast centre must be of sufficient size to manage at least 150 [[48], [49], [50]] newly diagnosed cases of early breast cancer (all ages, based on surgery) coming under its care each year [6]. The breast centre must also treat at least 50 cases of metastatic breast cancer a year, independently from the line of treatment.

-

•

The minimum number is necessary to ensure a caseload sufficient to maintain expertise for each team member and to ensure cost-effective working of the breast centre [[50], [51], [52]]. There is good quality data that shows that breast cancer survival is related to the number of cases treated per annum (see also supporting evidence in Appendix 1, section 1.1.).

-

•Minimum caseload for core MDT members:

- Breast radiologist: 1000 mammographic exams (5000 for breast radiologists participating in a centralised screening programme), 200 breast ultrasounds and 50 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies and 50 breast guided interventions per year

- Breast radiographer: 1000 mammograms per year

- Breast pathologist: 50 preoperative samples and 50 primary breast cancer resections per year; should report on 25 metastatic breast surgical specimens (biopsy performed for suspicious metastasis) per year

- Breast surgeon: 50 primary breast surgeries per year

- Breast medical oncologist: 50 early and 25 metastatic breast cancer patients treated per year

- Breast radiation oncologist: 50 early breast cancer patients treated per year

- Breast nurse: 50 early and 25 metastatic breast cancer patients cared for per year.

4.3. Screening

-

•

Where a population-based breast cancer screening programme exists, the breast centre and the screening programme should coordinate the assessment of screen-positive cases to ensure quality and continuity of care and optimisation of resources.

-

•

It is recommended that diagnostic assessment of screen-detected imaging findings is done in the breast centre.

-

•

The breast centre should contribute to improving protocols and professional expertise at screening centres.

4.4. Patient pathway and protocol

-

•

The breast centre must develop a patient pathway that ensures continuity of care and describes the steps and their timing from diagnosis (or screening) to follow-up including advanced disease, palliative care and end of life. This pathway must be backed up by evidence-based protocols between care providers which guarantee the continuity of care.

-

•

The breast centre must identify the guidelines (national and/or international) from which to develop the patient pathway and internal protocols must be formally reviewed at least on an annual basis at the formal internal review meeting.

-

•

The patient pathway must be agreed at least by the core MDT members but preferably also by extended team members.

4.5. MDT meeting (MDM)

The breast centre must hold at least weekly a multidisciplinary case management meeting (MDM) to discuss diagnostic preoperative and postoperative cases, as well as any other issues related to breast cancer patients that requires multidisciplinary discussion. Advanced breast cancer cases must also be discussed.

-

•

At least 95% of all early and locally advanced breast cancer cases and at least 50% of metastatic cases must be discussed at the meeting (but in future the goal is that all cases, early and metastatic, are discussed at the MDM). At pre-operative stage, the MDM must consider patient-related factors, tumour-related factors, and treatment options.

-

•Team members who must be present:

-

–Discussion of pre-operative breast cancer cases: radiologist, pathologist, medical oncologist, surgeon, radiation oncologist, breast nurse and breast data manager

-

–Discussion of post-operative cases: pathologist, surgeon, medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, breast nurse and breast data manager

-

–Discussion of metastatic breast cancer cases: medical oncologist, radiation oncologist, breast nurse, radiologist, pathologist, nuclear medicine physician (mandatory if the breast centre performs and uses positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) and recommended if the nuclear medicine service is not inside the hospital), palliative care specialist and breast data manager.

-

–

-

•

Other team members must be encouraged to attend and must be available for consultation.

-

•

Other specialists must be involved if necessary to discuss the clinical situation of patients.

-

•

Radiological images must be available at the MDM. A photograph of the breast should be available to decide the best surgical strategy. Macroscopic pictures or the histology of special cases preferably from slides (video microscope or scanned slide) should be shown to support understanding of difficult histopathological reports.

-

•

Evidence on decisions taken for each patient at the meeting must be formally recorded. The name of all team members participating in each meeting must be formally recorded.

-

•

As the patient is usually not present at the MDM and patient preferences must always be taken into account, and because the available clinical documents could miss key information, an MDM decision might, in some cases, be modified at the time of communication with the patient. For this reason, it is important that the breast care nurse present knows the patient’s wishes and expectations to ensure they can be shared at the MDM. The clinician who informs and discusses with the patient must have the competence to understand why the patient wants a change of the recommendation. The reason for change must be documented in the patient chart and the MDM must be informed.

4.6. Breast centre coordinator

The breast centre must have a nominated breast centre coordinator, who can be a healthcare professional from any specialty within the core team, responsible for the multidisciplinary approach and the full involvement of breast experts from the core disciplines and their regular participation in the MDM. The coordinator must ensure there is training and continuing medical education of MDT members; ensure the centre has certain breast related research; and ensure the centre’s performance is based on high quality data collection and indicators.

4.7. Communication of diagnosis, treatment plan and waiting times

-

•

A diagnosis must be given to the patient in a face to face meeting as soon as possible and must not be given by letter or on the telephone, unless there are exceptional circumstances. A preliminary communication on the diagnosis can be given to the patient by each specialist according to their competence.

-

•

The MDT recommendation for the treatment plan should be communicated and discussed with the patient by the clinician who has initially seen the patient and/or the clinician who will take primary responsibility for providing the first treatment modality. This discussion with the patient is crucial to arrive at a shared decision which includes the patient’s wishes.

-

•

Healthcare professionals who deal with cancer patients and their families are recommended to have training in and knowledge about communication skills.

-

•

A breast care nurse must be available to discuss and give any additional information to the patient regarding treatment and to give emotional support. A private room should be available. A psycho-oncologist should also be available to provide more advanced support, when needed, to the patient and family.

-

•

Each patient must be fully informed about each step in the diagnostic and therapeutic pathway and must be given adequate time to consider the options and make an informed decision.

-

•

Patients must be allowed to ask for a second opinion [53], without being penalised in any way.

-

•

Patients must start primary treatment within a maximum of 4–6 weeks from the first diagnostic examination in the breast centre [54]or first consultation at the breast centre if diagnosed elsewhere.

-

•

Follow-up should be done within the breast centre according to the local organisation and patient preference.

-

•

The breast centre should offer to plan imaging investigation procedures at the same visit.

-

•

The breast centre must give advice and support to the patient with symptoms and complaints due to hormonal therapy (osteoporosis, gynaecological problems, etc.), referring the patient to the appropriate specialist.

-

•

If the patient does not attend the breast centre for follow-up, the centre should collect follow-up information from elsewhere at least yearly for its database.

4.8. Patient information

-

•

Patients must be offered clear verbal and written information (leaflets) that describe the diagnostic and treatment options. Leaflets should be personalised for the breast centre in all the main languages spoken by the population served.

-

•

The leaflets should inform patients about diagnostic and treatment options not offered by the breast centre if they are covered in current guidelines.

-

•

The centre should provide information on local support groups and national advocacy organisations and the availability of group and/or individual psychological support in the centre.

-

•

Patients should be provided with a copy of their rights as outlined in the breast cancer resolution of the European Parliament [7].

4.9. Advocacy group/patient volunteer group

It is recommended that the breast centre collaborates with a local/national advocacy group or patient volunteer group. This group should collaborate with the centre to offer activities and projects dedicated to breast centre patients.

4.10. Quality control

-

•

The breast centre must have a database to collect data on all primary and advanced breast cancer patients it treats.

-

•

Data collection is essential to monitor compliance with national and/or international quality indicators, standards and guidelines, and it is also a basis for scientific research at the breast centre.

-

•

The breast centre must achieve the minimum standard for EUSOMA’s mandatory quality indicators (as described in EUSOMA’s quality indicators in breast cancer care, 2017, and future updates) [54]. If a minimum standard is not achieved the breast centre must put in place corrective actions and re-evaluate measures at an agreed date.

-

•

Data must include source of referral, clinical and pathological diagnosis, treatment, follow-up and clinical outcomes.

-

•

The breast centre must also collect in the database, or in a separate register, data on all surgical operations performed on benign disease (with the exclusion of inflammatory disease, operations for cosmetic reasons or prophylactic surgery).

-

•

The breast centre must have a data manager who works in the core team under the supervision of a medical doctor designated by the clinical coordinator. The data manager is responsible for data collection and analysis and for the organisation of audit meetings. Data should preferably be collected during the patient management process. The data manager must inform the breast centre team about performance quality according to indicators and about any emerging criticality.

-

•

The breast centre should participate in external benchmarking activities (comparison of results with those of other centres).

-

•

Breast centres should yearly monitor their outcomes at least on the following items: local recurrence rate, distant recurrence rate, sequelae (surgical, radiation and systemic therapy) aesthetic outcomes, functional outcomes.

-

•

Breast centres are strongly advised to collect and analyse validated patient reported outcomes (PROs) using validated measurements (patient reported outcome measures, PROMs).

-

•

The centre must have a formal internal review meeting at least once a year to discuss all performance aspects, i.e. audit results, continuity of care, organisational and clinical aspects, critical issues, results of corrective actions, new projects, etc. Core team members must participate in this meeting, and extended members should participate. Minutes of the meeting and the list of participants must be kept.

4.11. Education

The breast centre should provide teaching on a local, national or international basis. Some breast centres may have expertise in teaching certain subjects, such as reconstruction, screening, pathology/molecular biology, systemic therapies, radiation oncology, etc. The breast centre should organise at least one teaching course per year at local, regional, national or international level.

4.12. Research

Research is an essential part of training specialists and underpins every aspect of clinical practice, and breast centres should be involved in both clinical (i.e. clinical trials) and translational research. The breast centre should record the numbers of patients participating in clinical trials and collect details of any other research activities, such as evaluation of newly introduced techniques. The breast centre should aim to include at least of 5% of patients in clinical trials each year.

5. Core MDT members

All core MDT members should comply with EUSOMA’s guidelines on standards for training specialised health professionals who deal with breast cancer [55]. All specialists must work according to protocols and national/international guidelines. All specialists working in the core team must comply with all specialist related requirements indicated in the sections below.

5.1. Breast radiology

Breast radiologists.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 dedicated breast radiologists.

-

•

To be considered a breast specialist, a radiologist must spend at least 50% of their working time on breast imaging.

-

•

Breast radiologists must be involved in the full assessment of breast patients, including invasive procedures (core biopsy, ultrasound guided, stereotactic vacuum assisted biopsy, etc.).

-

•

Breast radiologists should participate in national or regional radiology quality assurance schemes.

-

•

Where possible, radiologists involved in the assessment of breast patients should participate in both breast screening and symptomatic breast imaging.

-

•

Breast radiologists must read a minimum of 1000 mammography cases per year and conduct and read a minimum of 200 breast ultrasound studies (targeted, diagnostic or screening) per year, and a minimum of 50 breast MRI studies per year.

-

•

Breast radiologists participating in a centralised screening programme must have a workload of at least 5000 cases per year [10].

-

•

Breast radiologists must attend at least one diagnostic clinic per week for symptomatic patients or further assessment of breast screening recall.

-

•

Each breast radiologist must perform a minimum of 50 breast guided interventions per year.

-

•

Double reading of mammograms is encouraged both for screening and symptomatic mammography when the breast centre workload is less than 3000 per year; double reading of breast MRI studies is encouraged when the MRI workload is less than 200 per year.

-

•

All imaging studies taken outside the centre must be reviewed by breast centre radiologists.

Examinations.

-

•The breast radiology team must perform:

-

◊Clinical examination

-

◊Mammography

-

◊Ultrasound and Doppler ultrasound of the breast and axilla

-

◊Breast MRI

-

◊Core biopsy – free-hand, ultrasound guided, mammography guided

-

◊Vacuum-assisted biopsy under mammographic or breast MRI guidance. If this is not available within the breast centre, there must be a formal agreement with a local diagnostic service

-

◊Lesion localisation and bracketing under ultrasound, mammography, and MRI guidance. If this is not available within the breast centre, there must be a formal agreement with a local diagnostic service

-

◊Multidisciplinary working should allow all standard investigations for triple assessment (clinical examination, mammography and/or ultrasound and biopsy) to be completed in one visit (but respecting patient’s preferences) and maximum within 5 working days

-

◊

-

•

Non-surgical diagnosis by needle biopsy of both benign and malignant disease is the required standard.

-

•

Palpable lesions must be examined via ultrasound and where there is an ultrasound correlate, needle biopsy must be done under ultrasound guidance.

-

•

Needle biopsy must be image-guided for all non-palpable lesions.

-

•

Image-guided biopsy of non-palpable lesions must be done under the guidance of an appropriate imaging method; usually, the same imaging method that was used to establish the diagnosis should be used to guide biopsy.

-

•

MRI-guided and mammography guided biopsy can be replaced by ultrasound guided biopsy; however, in these cases, the radiologist must ensure that the target identified on ultrasound corresponds to the target seen on the other imaging method.

-

•

Primary diagnosis using open surgical biopsy is not recommended and only acceptable in exceptional cases.

-

•

Core or vacuum assisted biopsy is the preferred technique for sampling the breast.

-

•

Core biopsy is also considered the preferred technique for sampling axillary lymph nodes. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) may also be used but requires the availability of a pathologist who is experienced in interpreting cytology of FNAC specimens.

-

•

The breast centre must use a single formal imaging risk classification (e.g. BI-RADS or the European classification).

-

•

The breast centre must collaborate with board certified imaging experts who carry out interventional radiology techniques, such as biopsy of metastatic lesions in breast cancer patients.

Imaging equipment.

The breast centre must have:

-

•

Digital mammography

-

•

Stereotactic biopsy attachment and/or dedicated prone biopsy table

-

•

Methods for mammography guided stereotactic lesion localisation and bracketing (wire or clip)

-

•

Ultrasound equipped with a small parts probe ≥12 MHz and including Doppler function

-

•

Methods for ultrasound guided core biopsy

-

•

Methods for ultrasound guided lesion localisation and bracketing procedures

-

•

Breast MRI with ≥1.5 T, dedicated bilateral breast coil; dedicated equipment for breast immobilisation is strongly encouraged

-

•

Access to MRI-guided vacuum-assisted biopsy and MRI-guided lesion localisation or bracketing, either in-house or by formal agreement with an affiliated diagnostic service

-

•

Digital storage of all images (mammograms, ultrasound documentation, MRI studies)

-

•

Equipment no older than 10 years, unless carefully maintained and complying with national and/or international standards

-

•

Routine quality control of all equipment used for breast imaging, according to national protocols and/or European guidelines [10]. If the centre follows a national protocol, this must include essential points such as assessment of image quality of the monitors and estimate of the maximum average of glandular dose.

Breast radiographers.

-

•

Radiographers must have training in breast diagnosis to perform mammography.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 breast radiographers, each performing at least 1000 mammograms a year.

-

•

Radiographers should also attend refresher courses at least every 3 years.

-

•

The breast centre must have protocols on the periodical review of the technical performance of radiographers.

-

•

Radiographers should participate in regular audit of their technical performance.

-

•

Breast centres must have protocols on quality control on a daily basis and must follow guidelines on equipment quality control as detailed in European guidelines.

5.2. Breast pathology

Breast pathologists.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 dedicated breast pathologists (1 of whom should be nominated as the breast pathology lead for the MDT). A pathologist at the breast centre must spend at least 50% of their working time on breast disease.

-

•

A breast centre pathologist must report on at least 50 early breast cancer resections per year and should report on at least 100 pre-operative samples (with a mandatory minimum of 50) and 25 metastatic breast surgical specimens per year.

-

•

Breast pathologists must take part in regional, national and/or European breast cancer quality assurance schemes.

-

•

Breast pathologists must be familiar with their national and/or European quality standards and guidelines.

Procedures.

-

•

Breast pathology reports must include histological type (according to the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Breast), grading (according to WHO and EU guidelines: Elston and Ellis modified Bloom-Richardson grading system), immunohistochemistry (IHC) for diagnosis and for oestrogen, progesterone and HER2 receptors status. In situ hybridisation (ISH) analyses of HER2 must be obtained from reference laboratories. Reports should also include evaluation of proliferation.

-

•

Ki67 is the preferred marker to assess proliferation [56] but is not mandatory. Caution is needed about the reproducibility of IHC for Ki67. If used, the St Gallen International Breast Cancer Conference has suggested calibrating a common scoring method to achieve high inter-laboratory reproducibility in Ki67 on centrally stained tissue microarray slides [56].

-

•

For reporting core biopsies, breast pathologists must use the B1-5 classification as described in European guidelines [10]. Reporting by 2 pathologists of core biopsies is encouraged.

When the patient is treated in an institution different from that performing the pathological diagnosis, the tumour blocks and slides must be requested for revision by the breast pathologist.

-

•

Breast tissue samples must be kept as long as possible because the patient can relapse more than 20 years after the first diagnosis. At least 1–2 FFPE blocks most representative of the lesion must be stored in perfect conditions (controlled temperature, humidity and parasites) and kept for at least 20 years or according to the national law, whichever is longer [57]. An archive of digital slides should be considered.

Equipment.

-

•

The pathology laboratory must be equipped with microscopes, cryocut, histoprocessors, microtome staining machines and immunostainers, and a system for obtaining surgical sample and slide pictures.

-

•

The equipment must be replaced every 10 years unless carefully maintained and complying with national and/or international standards.

5.3. Breast surgery

Breast surgeons.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 dedicated breast surgeons with training in breast surgery.

-

•

Breast surgeons must spend at least 50% of their working time on breast disease.

-

•

Any breast surgeon at the breast centre must carry out primary surgery as first operator on at least 50 newly diagnosed breast cancers a year. If the centre has surgeons in training, those responsible for supervising trainees might perform fewer than 50 primary cases as first operator. In this case documentation on their role as second operator supervising trainees must be available.

-

•

Breast surgeons must be able to perform sentinel lymph node biopsy in all settings (adjuvant, neoadjuvant, recurrence), all types of mastectomy (nipple sparing, skin sparing, simple) and guided surgery for non-palpable tumours, and breast conserving surgery.

-

•

Breast surgeons must be able to perform risk-reducing techniques for high-risk patients.

-

•

Breast surgeons should advise and where necessary treat women with benign disease, e.g. cysts, fibroadenoma, mastalgia, inflammatory conditions.

-

•

The breast surgical team should be able to offer level I and II oncoplastic techniques; breast surgeons should have additional training in oncoplastic procedures to offer the patient surgical options.

5.4. Breast medical oncology

Breast medical oncologists.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 breast medical oncologists dedicated to breast cancer. Any breast medical oncologist at the breast centre must spend 50% of their working time on breast cancer.

-

•

Breast medical oncologists must treat a minimum of 50 early and 25 metastatic breast cancer patients per year.

-

•

Breast medical oncologists must supervise systemic therapy and all decision-making processes for its use.

-

•

Follow-up information on all patients treated with systemic therapy must be collected, even if patients are treated outside the breast centre.

5.5. Breast radiation oncology

Breast radiation oncologists.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 radiation oncologists dedicated to breast cancer. Any breast radiation oncologist at the breast centre must spend at least 50% of their working time on breast cancer.

-

•

Breast radiation oncologists must treat a minimum of 50 early breast cancer patients per year. They must also have experience with palliative treatments.

-

•

Breast radiation oncologists must be competent to determine the need for techniques such as intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), image guided radiotherapy (IGRT), cardiac-sparing radiotherapy, brachytherapy, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) and stereotactic radiosurgery.

-

•

Radiation oncologists must be adequately trained in breast cancer contouring, including regional nodes, and use international guidelines such as those developed by the European Society for Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO).

-

•

Radiation oncology units must develop and work to an evidence-based breast radiation therapy clinical protocol that is reviewed and updated regularly: this should include dose objectives and constraints for each breast radiation technique.

-

•

It is recommended that all radiation oncology units have a dedicated breast radiation planning and treatment MDT with radiation oncologists, radiotherapy physicists, dosimetrists and therapy radiographers to review and manage challenging cases including those who cannot be treated within the standard clinical protocols.

-

•

If the radiation oncology unit is not available within the hospital, the breast centre must have an agreement with a radiation oncology unit and breast radiation oncologists must attend the MDM at the breast centre. In all situations, breast radiation oncologists must have full access to all patient data regarding diagnosis and treatment and must be involved in the patient management plan.

-

•

Follow-up information on all patients treated with radiation therapy must be collected, even if patients are treated and/or followed-up outside the breast centre.

Breast radiation technicians.

-

•

It is strongly recommended that the breast centre has dedicated radiotherapy physicists, dosimetrists and therapy radiographers. At least 1 medical physicist and 2 radiation therapists/dosimetrists should have breast cancer as a main interest.

Equipment and techniques.

-

•

The staffing and technical platform should fulfil the requirements described by the EORTC Radiation Oncology Group [58]. Therefore, the minimum equipment in a radiation oncology unit must include at least 2 megavoltage units, a CT scanner dedicated to treatment preparation, and a 3D treatment planning system. Treatment machines must be equipped with IGRT tools to verify accurateness of treatment delivery. Equipment must be no older than 12 years, unless carefully maintained, upgraded and complying with national and/or international standards.

-

•

Radiation therapy planning must be carried out according to optimised (3D) procedures based on anatomically defined volumes, with treatments individualised to 3D target volume definitions and contouring. Field-based treatments must be abandoned.

-

•

The evaluation must be done using tools such as dose volume histograms, taking into account predefined objectives for the dose distribution for the target volumes and dose constraints for organs at risk (including as a minimum the heart and lungs). Respiratory control should be available and used according to predefined indications including patient risk factors and doses to heart and lungs.

-

•

Experience is essential especially in techniques aimed at optimising the homogeneity of dose distribution, including IMRT and IGRT, partial breast irradiation, and cardiac sparing techniques such as breath-hold.

-

•

Access to 3D brachytherapy is highly recommended.

-

•

SBRT and radiosurgery must be available for treatment of oligometastases and brain metastases.

-

•

The breast centre must have a quality assurance programme for the entire radiation oncology process, including for the machines/infrastructure. If specific equipment or working procedures are in place for treating breast cancer patients, they must be included in the quality assurance programme. Sufficient ongoing education for all healthcare professionals is essential.

-

•

Clinical and translational radiation therapy research is encouraged.

5.6. Breast cancer nursing

Breast care nurses.

-

•

The breast centre must have at least 2 breast care nurses dedicating all their working time to breast cancer.

-

•

Breast care nurses must see a minimum of 50 early and 25 metastatic breast cancer patients per year.

-

•Breast care nurses must be available:

-

◊Throughout the patient pathway from diagnosis through treatment and follow-up, to offer practical advice, emotional support, explanation of the treatment plan and information on side-effects [27].

-

◊At the time of communication of recurrent or metastatic disease

-

◊At follow-up clinics.

-

◊

-

•Breast care nurses must also:

-

◊Help to develop protocols, patient pathways, information and implementation of nursing research [27].

- ◊

-

◊

6. Extended MDT and other services

6.1. Psychological support/psycho-oncology

-

•

Basic psychological counselling and emotional support must be provided by a breast nurse or another professional trained in the psychological aspects of breast cancer care. If psychological morbidity cannot be dealt with effectively by them, patients must be referred to a psycho-oncologist or psychiatrist.

-

•

Distress must be recognised, monitored, documented and treated promptly at all stages of disease. It must be assessed in all patients using a tool such as a distress thermometer [62].

-

•

A psycho-oncologist must be available throughout the disease continuum to patients and their families at the breast centre to help patients deal with common psychological issues in breast cancer such as fear of recurrence, body image disruption, sexual dysfunction, treatment-related anxieties, intrusive thoughts about illness, marital/partner communication, feelings of vulnerability, existential concerns regarding mortality, fertility, work-related issues, depression, and, in particular for advanced breast cancer patients, fear of dying, coping with an incurable disease and continuous treatment, and feelings of isolation and guilt.

-

•

A psychiatrist must also be available to patients.

6.2. Geriatric oncology

-

•

The breast centre must have access to geriatricians with oncology experience.

-

•

The role of the geriatric oncologist is to coordinate recommendations to other specialists about the need for personalised interventions for older patients with increased vulnerability to stressors.

-

•

All older patients (70+) and patients who appear frail or have severe comorbidity must be screened with a quick, simplified frailty screening tool, such as the adapted Geriatric-8 (G8) screening tool [63,64].

-

•

Frail patients as suggested by the screening tool should undergo a full geriatric assessment [65]. The assessment can be based on self-report combined with objective assessments that can be performed by the breast nurse in collaboration with a physician (geriatrician/internist/medical oncologist).

-

•

Cognitive impairment affects all aspects of treatment – ability to consent, compliance with treatment, and risk of delirium – and screening using tools such as Mini-Cog [66] is advised. A geriatrician, geriatric psychiatrist or neurologist should preferably be involved with impaired patients.

-

•

For frail patients, the geriatrician should be present in the MDT meeting, or easily available for consultation, to discuss treatment options aligned with the patient’s goals for care.

6.3. Oncology pharmacy

-

•

Oncology pharmacists must have experience with antineoplastic treatments and supportive care; interactions between drugs; drug dose adjustments based on age, liver and kidney function, and toxicity profile; utilisation and monitoring of pharmacotherapy; patient counselling and pharmacovigilance; and knowledge of complementary and alternative medicines.

-

•

Oncology pharmacists must liaise with medical oncologists to discuss cancer treatments, including interactions with other treatments.

-

•

Oncology pharmacists must be involved in the clinical trials research of the breast centre.

-

•

Oncology pharmacists must use the European QuapoS guidelines (European Society of Oncology Pharmacy) [67]. Oncology drugs must be prepared in the pharmacy and dispensing must take place under the supervision of the oncology pharmacist.

6.4. Nuclear medicine

-

•

The breast centre must have access to nuclear medicine specialists for procedures relevant to breast cancer care.

-

•

Sentinel node biopsy (SNB) is included in the standard of care and must be available. The nuclear medicine physician should oversee the procedure and identify the nodes in planar and single photon emission computerised tomography (SPECT) or SPECT/CT images (recommended if available), as well as marking the location on the skin, and may collaborate with the surgeon during surgery in locating the lesion with an intraoperative probe.

-

•

The nuclear medicine physician must oversee all aspects of PET/CT for patients who require this procedure either with 18F-FDG or with other radiotracers, including indications, multidisciplinary algorithms and management protocols [68], [69], [70], [71], [72].

-

•

There is evidence of the efficacy of 18F-FDG-PET/CT in selected clinical indications in breast cancer, such as staging of high-risk patients, treatment planning, response monitoring, and detection of recurrent disease [68], [69], [70], [71] 18F-FDG-PET/CT should not be used for surveillance for recurrent disease in asymptomatic patients.

-

•

Conventional nuclear medicine such as bone scan and cardiac multigated acquisition (MUGA) should also be available.

-

•

Equipment should preferably be onsite, be less than 10 years old, unless carefully maintained and complying with national and/or international standards, ready for radiation treatment planning, and have an integrated picture archiving and communication system/radiology information system (PACS/RIS) and updated workstations.

-

•

The nuclear medicine department must be able to perform daily verification of protocols and to react accordingly. Quality-assurance protocols must be in place. An option for ensuring the high quality of PET/CT scanners is provided by the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) through EARL accreditation.

6.5. Physiotherapy

-

•

There must be at least 2 physiotherapists with expertise in lymphatic drainage for the treatment of lymphoedema and its related sequelae, and to ensure good shoulder mobility.

-

•

Physiotherapists with expertise in rehabilitation of metastatic patients with sequelae of bone or brain metastases and their treatments must be available for breast centre patients.

-

•

A rehabilitation programme for cancer patients who require assistance in the recovery of functional status after treatment must be available.

-

•

Physiotherapists must collaborate with the palliative care service and with medical oncologists and breast nurses at the breast centre.

6.6. Breast plastic surgery

The role of breast plastic surgeons depends on the organisation of the breast centre. In most centres, microsurgery reconstruction techniques are performed by breast plastic surgeons as part of the breast surgical team. If necessary the breast centre must make arrangements with 1 or 2 breast plastic surgeons with a special interest in breast reconstructive and reshaping techniques.

6.7. Interventional radiology

The breast centre must have access to interventional radiologist expertise. Bone metastases carry an important risk of developing skeleton-related events that impact quality of life. Besides surgery and radiotherapy, percutaneous image-guided cementoplasties/closed internal fixation/thermal ablation have a growing role in the treatment of these metastases.

6.8. Self-image support

-

•

There must be a breast prosthesis fitting service within the breast centre or referral to a service outside the centre.

-

•

There must be counselling about hair prosthesis and referral to recommended services.

6.9. Palliative care

Palliative care, as defined by the World Health Organisation, applies not only at end of life but throughout cancer care. Palliative care means patient and family-centred care that enhances quality of life by preventing and treating physical, psychosocial and spiritual suffering early in the course of advanced disease [[73], [74], [75]].

Palliative care services include general palliative care provided by the oncology professionals at the breast centre who are responsible for breast cancer care and specialised palliative care provided by a multidisciplinary palliative care team [[76], [77], [78]]. Close collaboration between the breast centre and palliative care teams is crucial.

-

•There must be a specialist palliative care team that provides expert outpatient and inpatient care including specialist physicians and nurses, working with social workers, chaplains, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, pain specialists and psycho-oncologists. In practice:

-

◊The breast centre team, in particular medical oncologists and breast nurses, is usually responsible for basic palliative care such as symptom control and screening for disease and treatment related symptoms and suffering

-

◊Patients with severe symptom burden or unmet physical, psychosocial or spiritual needs must be referred to a specialist palliative care team, irrespective of the cancer-specific treatment plan [79].

-

◊

-

•

The most common physical, psychosocial and spiritual symptoms/problems and functional impairments must be assessed in all patients using tools such as the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) [80] or EORTC questionnaire on quality of life in palliative cancer care patients (QOL-C15-PAL – https://qol.eortc.org/questionnaire/qlq-c15-pal).

-

•

The palliative care team must have good knowledge of cancer disease and cancer treatments including adverse effects of treatment and rehabilitation needs to be able to offer holistic care in collaboration with other professionals. Early palliative care should be provided in conjunction with cancer specific treatments for treatment-related distressing symptoms such as pain and dyspnoea, and for psychosocial and spiritual care.

-

•

The palliative care team must support family members and carers, and have experience of taking care of younger patients and their families.

-

•

Palliative care specialists and oncologists must aspire to meet the standard of ESMO Designated Centres of Integrated Oncology and Palliative Care (http://www.esmo.org/Patients/Designated-Centres-of-Integrated-Oncology-and-Palliative-Care).

-

•

To ensure continuity of care at home, the palliative care team must work with primary or community care providers or be able to provide direct care at home, and must provide end-of-life care.

6.10. Clinical genetics

-

•

The breast centre must have a dedicated clinical geneticist responsible for a genetics clinic, or an agreement with a hospital where this service is available.

-