Left-right (L-R) asymmetric intraciliary calcium transient at the node is the determinant of L-R axis in mice.

Abstract

Immotile cilia sense extracellular signals such as fluid flow, but whether Ca2+ plays a role in flow sensing has been unclear. Here, we examined the role of ciliary Ca2+ in the flow sensing that initiates the breaking of left-right (L-R) symmetry in the mouse embryo. Intraciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were detected in the crown cells at the node. These Ca2+ transients showed L-R asymmetry, which was lost in the absence of fluid flow or the PKD2 channel. Further characterization allowed classification of the Ca2+ transients into two types: cilium-derived, L-R-asymmetric transients (type 1) and cilium-independent transients without an L-R bias (type 2). Type 1 intraciliary transients occurred preferentially at the left posterior region of the node, where L-R symmetry breaking takes place. Suppression of intraciliary Ca2+ transients delayed L-R symmetry breaking. Our results implicate cilium-derived Ca2+ transients in crown cells in initiation of L-R symmetry breaking in the mouse embryo.

INTRODUCTION

Primary cilia are antenna-like organelles that are several micrometers in length and extend from the apical surface of most vertebrate cells. They respond to a variety of extracellular signals including low molecular weight chemicals, proteins, light, and mechanical stimuli (1–3). Primary cilia play essential roles in development and physiology, their importance underscored by the existence of a group of diseases known as ciliopathies that include cystic kidney disease as well as metabolic and neurodevelopmental disorders that are caused by ciliary dysfunction (4).

The establishment of left-right (L-R) asymmetry of the human body also depends on primary cilia. Breaking of L-R symmetry takes place at the L-R organizer region, and it requires cilia in many vertebrates including zebrafish, frog, and mouse (5). At the ventral node of the mouse embryo, motile cilia rotate in a clockwise direction and thereby generate a leftward fluid flow (nodal flow). This unidirectional flow is sensed by immotile (primary) cilia on crown cells located at the periphery of the node (6). However, how the embryo senses this fluid flow has remained unknown. Whereas Ca2+ signaling is required for establishment of L-R asymmetry, its precise action has not been revealed. In particular, whether Ca2+ contributes to flow sensing by immotile cilia is not clear (7, 8). Although Ca2+ transients have been detected in cilia at Kupffer’s vesicle of zebrafish embryos (9), they have not been detected in those at the node of the mouse embryo (8).

To shed light on whether Ca2+ plays a role in the sensing of fluid flow by immotile cilia at the node of the mouse embryo, we have now examined the dynamics of ciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ in the sensor cells using improved experimental methods. We detected L-R asymmetric Ca2+ transients in the cilia and cytoplasm of crown cells, and these transients were found to be required for L-R symmetry breaking.

RESULTS

L-R asymmetric Ca2+ transients in immotile cilia at the node of the mouse embryo

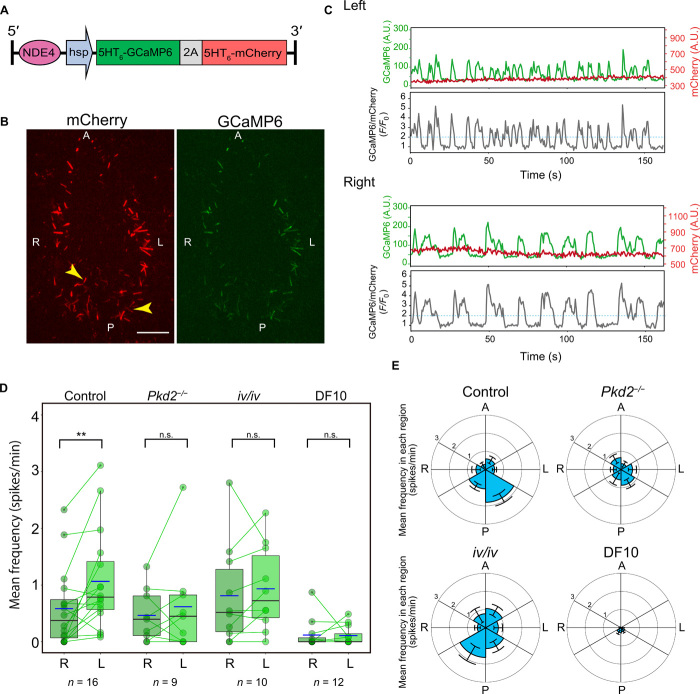

To visualize Ca2+ in cilia of crown cells at the node of the mouse embryo, we established a transgenic mouse line that expresses a genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator, GCaMP6 (10), in these cells. Expression of the transgene, NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-5HT6-mCherry (Fig. 1A), was controlled by the node crown cell–specific enhancer (NDE) of the mouse Nodal gene (6, 11). Both GCaMP6 and the fluorescent marker protein mCherry were fused to a ciliary targeting sequence derived from 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor isoform 6 (5HT6) (12). 5HT6-mCherry was conjugated to 5HT6-GCaMP6 by the 2A peptide so as to allow posttranslational cleavage (13). This transgene was thus designed to label cilia with both 5HT6-GCaMP6 and 5HT6-mCherry at an equimolar stoichiometry, with the latter protein serving as an internal control to allow correction for motion artifacts. Expression of the ciliary Ca2+ sensor did not affect organ laterality (fig. S1, A and B), ciliary length, or density (fig. S1, D and E).

Fig. 1. L-R asymmetric ciliary Ca2+ transients at the node of the mouse embryo.

(A) Transgene designed to monitor Ca2+ in immotile cilia at the node. The crown cell–specific enhancer of the mouse Nodal gene (NDE) drives expression of 5HT6-GCaMP6 and 5HT6-mCherry in crown cells of the node. (B) Simultaneous observation of GCaMP6 fluorescence and mCherry fluorescence in immotile cilia of the node. Arrowheads indicate the cilia analyzed in (C). A, anterior; P, posterior; L, left; R, right. Scale bar, 25 μm. (C) Representative Ca2+ transients in immotile cilia on the left or right side of the node. Fluorescence intensity values of GCaMP6 and mCherry in arbitrary units (A.U.) and the GCaMP6/mCherry F/F0 ratiometric values are shown. The threshold for analysis (F/F0 = 2.0) is indicated by the blue dotted line. (D) Mean frequency of ciliary Ca2+ transients on the left or right side of the node of the control (wild type and heterozygous), Pkd2−/−, and iv/iv embryos and embryos cultured in DF10 medium for 1 hour. Each dot indicates the mean frequency value for the left or right side of a single embryo, with the two values for each embryo being connected with a line. Box plots are also shown, and the blue line indicates the mean value. The n values indicate the numbers of embryos analyzed. **P < 0.01; n.s., not significant (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). (E) Circular plots of the mean spike frequency in cilia of the embryos are shown in (D). The node region is divided into six areas according to the A-P and L-R axes.

As expected, 5HT6-GCaMP6 and 5HT6-mCherry specifically labeled immotile cilia of crown cells at the node of the mouse embryo (Fig. 1B). Live imaging of the node with spinning disc confocal microscopy revealed fluctuations in the fluorescence intensity of GCaMP6 but not in that of mCherry, suggestive of the occurrence of Ca2+ transients in cilia of the crown cells (Fig. 1C and movie S1). To avoid photobleaching and phototoxicity, Ca2+ imaging was limited to the duration of ~2 min. Although cilia on both sides of the node showed Ca2+ transients, the frequency of these transients in many cells was higher on the left side than on the right (Fig. 1C). Quantitative analysis showed that the mean frequency of ciliary Ca2+ spikes per cells was higher on the left side of the node, with mean ± SEM values of 1.1 ± 0.2 spikes/min on the left versus 0.60 ± 0.2 spikes/min on the right (P = 0.003) (Fig. 1D). We also examined the distribution of cilia showing Ca2+ transients by dividing the node region into six areas and determined the mean Ca2+ spike frequency for each area. The left posterior area of the node showed the highest frequency (Fig. 1E). Coincidentally, the left posterior area of the node is the region where the velocity of nodal flow is highest when the flow develops at the node (14). The percentage of cilia exhibiting Ca2+ transients was also higher on the left side than on the right side (29 ± 5% versus 19 ± 4%; P = 0.023) (fig. S2, A and F). In addition, the total number of spikes on the left side was also higher than that on the right (19 ± 5 versus 12 ± 4 spikes/min; P = 0.009) (fig. S2B). Other parameters such as the mean peak intensity and the mean peak duration of Ca2+ transients did not differ significantly between left and right sides (fig. S2, C and D). Ca2+ transients in cilia with lower spike frequencies (<4 spikes/min) manifested a range of durations, whereas those in cilia with higher spike frequencies tended to be of shorter duration (fig. S2E).

Polycystin-2 (PKD2) is a cation channel essential for L-R determination (6, 15). Pkd2 mutant mouse embryos also showed ciliary Ca2+ transients (movie S2), but the mean spike frequency (Fig. 1, D and E), the percentage of cilia with Ca2+ transients (fig. S2, A and F), and the total number of spikes (fig. S2B) did not differ significantly between the left and right sides. Similarly, iv/iv embryos, which lack motile cilia and nodal flow (16, 17), did not show L-R differences in these parameters (Fig. 1, D and E; fig. S2, A, B, and F; and movie S3). L-R asymmetry of ciliary Ca2+ transients was thus lost in the absence of the PKD2 channel or nodal flow.

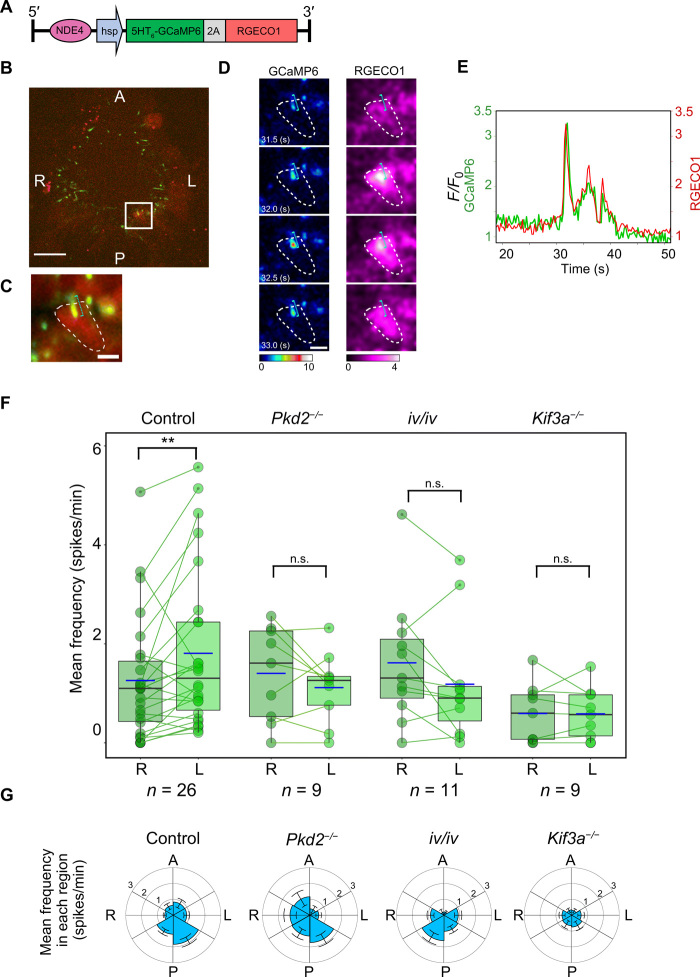

Bias of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients toward the left posterior region of the node

We next examined cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in node crown cells using an NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-RGECO1 transgenic mouse (Fig. 2A). This transgene encodes the RGECO1 protein without a ciliary targeting sequence as a cytoplasmic Ca2+ sensor and 5HT6-GCaMP6 as a ciliary Ca2+ sensor (18). This transgene did not affect L-R asymmetry of internal organs (fig. S1, F to H) or morphology of node cilia (fig. S1, I and J). Both cilia and the cytoplasm of crown cells at the node of transgenic mouse embryos showed Ca2+ transients (Fig. 2, B and E, and movie S4). Cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were detected on both sides of the node, but again, there was significant L-R asymmetry. The average spike frequency in each cell was thus 1.8 ± 0.3 spikes/min on the left side and 1.3 ± 0.2 spikes/min on the right (P = 0.004) (Fig. 2F). The percentage of cells showing cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (P = 0.028) (fig. S3A) and the total number of Ca2+ spikes (P = 0.024) (fig. S3B) were also significantly higher on the left side of the node. Peak intensity did not show an L-R difference (fig. S3C), whereas peak duration was shorter on the left side (7.5 ± 0.9 s versus 10.2 ± 0.7 s; P = 0.005) (fig. S3D), which may reflect the higher frequency of Ca2+ spikes in left crown cells. The relation between peak duration and spike frequency for cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (fig. S3E) was similar to that for ciliary Ca2+ transients (fig. S2E). Distribution of crown cells with cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients was also analyzed for the mean frequency and the percentages of cells with Ca2+ transients. Both parameters were highest in the left posterior area of the node (Fig. 2G and fig. S3F).

Fig. 2. Cytoplasm of crown cells also shows L-R asymmetric Ca2+ transients.

(A) Transgene designed to detect ciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients. (B) Image of ciliary 5HT6-GCaMP6 (green) and cytoplasmic RGECO1 (red) in crown cells at the node of an iv/+ embryo at the one-somite stage. The cell in the box was analyzed in (C) to (E). Scale bar, 25 μm. (C) Time-averaged fluorescence image of the cell shown in (B). The cell body and the cilium are indicated by the white dotted line and the blue dotted line, respectively. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Images of ciliary (GCaMP6) and cytoplasmic (RGECO1) Ca2+ transients. Color scales indicate the F/F0 value. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Time course of ciliary (GCaMP6) and cytoplasmic (RGECO1) Ca2+. (F) Mean frequency of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in crown cells on the left or right side of the node of control (wild type and heterozygous), Pkd2−/−, iv/iv, and Kif3a−/− embryos. Mean frequency is shown by the dots and connecting lines, as in Fig. 1D. The n values indicate the numbers of embryos analyzed. *P < 0.05; n.s. (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). (G) Circular plots of mean spike frequency (mean ± SEM values) in the cytoplasm of crown cells in the indicated embryos.

To examine the relation between ciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients, we simultaneously observed intraciliary Ca2+ and cytoplasmic Ca2+ in NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-RGECO1 transgenic mouse embryos (Fig. 2, B to E). Many of the crown cells showing ciliary Ca2+ transients also manifested cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (Fig. 2, B and E, and movie S4), although some cells showed ciliary Ca2+ transients without cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (fig. S4, E to H, and movie S5). In cells showing both types of Ca2+ transients, the changes in the fluorescence intensity of ciliary GCaMP6 and cytoplasmic RGECO1 were highly synchronized (Fig. 2, B to E, and fig. S4, A to D). Increases in cytoplasmic Ca2+ have been shown to spill over into cilia (19), suggesting that the ciliary Ca2+ transients observed in NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-5HT6-mCherry mice (Fig. 1, C to E) may include those derived from cytoplasmic Ca2+ and those independent of cytoplasmic Ca2+ (see below).

Determinants of L-R asymmetry in cytoplasmic Ca2+ spikes

Consistent with previous observations (20), cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were detected in crown cells of Pkd2−/− embryos and iv/iv embryos. However, these spikes occurred randomly on the left and right sides of the node, with no bias apparent for the left posterior region of the node (Fig. 2, F and G; fig. S3, A, B, and F; and movie S6). We also detected cytoplasmic Ca2+ spikes, albeit at a reduced frequency, in Kif3a−/− embryos (Fig. 2, F and G; fig. S3, A, B, and F; movie S6), which lack cilia (21), suggesting that some of the cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients observed in crown cells of control mice (wild type and heterozygous) are cilia independent. The L-R bias in spike number and frequency was also lost in Kif3a−/− embryos, suggesting that cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in control embryos include both cilium-independent transients, which are L-R symmetric, as well as cilium-dependent transients, which are L-R asymmetric (Fig. 3F).

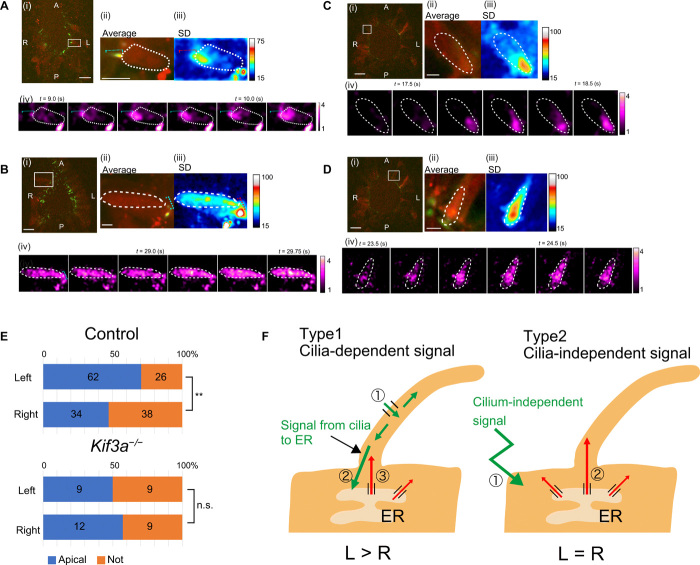

Fig. 3. Preferential restriction of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients to the apical region of crown cells on the left side of the node.

(A to D) Crown cells at the node of control [wild type in (A) and iv/+ in (B)] or Kif3a−/− (C and D) embryos showing Ca2+ transients restricted to the apical region of the cell (A and C) or a Ca2+ increase throughout the cytoplasm (B and D). Panels (i) show a representative image of ciliary 5HT6-GCaMP6 (green) and cytoplasmic RGECO1 (red), with the white box indicating the cell analyzed. Panels (ii) show a time-averaged image of the cell. Panels (iii) show the SD of intensity (F/F0) changes, reflecting their variation. A high SD is apparent at the base of the cilium in (A). Panels (iv) show images of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients, with an interval between consecutive frames of 0.25 s. The blue (ii) or red (iii) dotted line in (A) and (B) indicates the cilium. Scale bars, 20 μm (i) and 5 μm (ii). See movies S7 to S10. (E) Percentages of cells with apically restricted or nonrestricted Ca2+ transients. The numbers of cells showing each pattern (obtained from 18 control and 7 Kif3a−/− embryos) are also indicated. **P < 0.01; n.s. (χ2 test). (F) Two types of Ca2+ transients at the node. See the text for details.

The increase in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration during cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in crown cells on the left side of the node in control embryos was detected preferentially in the apical region of the cell, close to the base of the cilium (Figs. 2D and 3, A and E, and movie S7), although it was not limited to the apical region in all such cells (Fig. 3, B and E, and movie S8). No such difference in the number of cells showing these two patterns was apparent for cells on the right side of the node. In Kif3a−/− embryos, the numbers of cells showing apically restricted (Fig. 3C and movie S9) and nonrestricted (Fig. 3D and movie S10) Ca2+ increases were similar on the left and right sides of the node (Fig. 3E). In addition, the mean frequency of apically restricted Ca2+ transients was higher than that of nonrestricted Ca2+ transients on both left and right sides of control embryos, and Kif3a−/− embryos showed no such difference (fig. S5A). Together, these results suggested that L-R asymmetric, cilium-dependent cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients are preferentially localized to the apical region of crown cells and that cilia are required for the generation of high-frequency Ca2+ transients.

To determine whether the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which stores intracellular Ca2+, is present in the apical region of crown cells, we stained live embryos with ER-Tracker Red. Pronounced staining was apparent at the apical region of crown cells (fig. S5, B and C, and movie S11). In addition, immunostaining with antibodies to protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), an ER protein, as well as with those to acetylated tubulin (Ac-tubulin), a cilia marker, revealed that ER was localized to the apical region of crown cells (fig. S5D). Furthermore, focused ion beam (FIB)–scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of the node showed ER to be present in the apical region of crown cells near the base of the cilium (fig. S5, E to J and K to P, and movie S12). Together, these results thus suggested that the apical region of crown cells, at the base of the primary cilium, is the site of intracellular Ca2+ release.

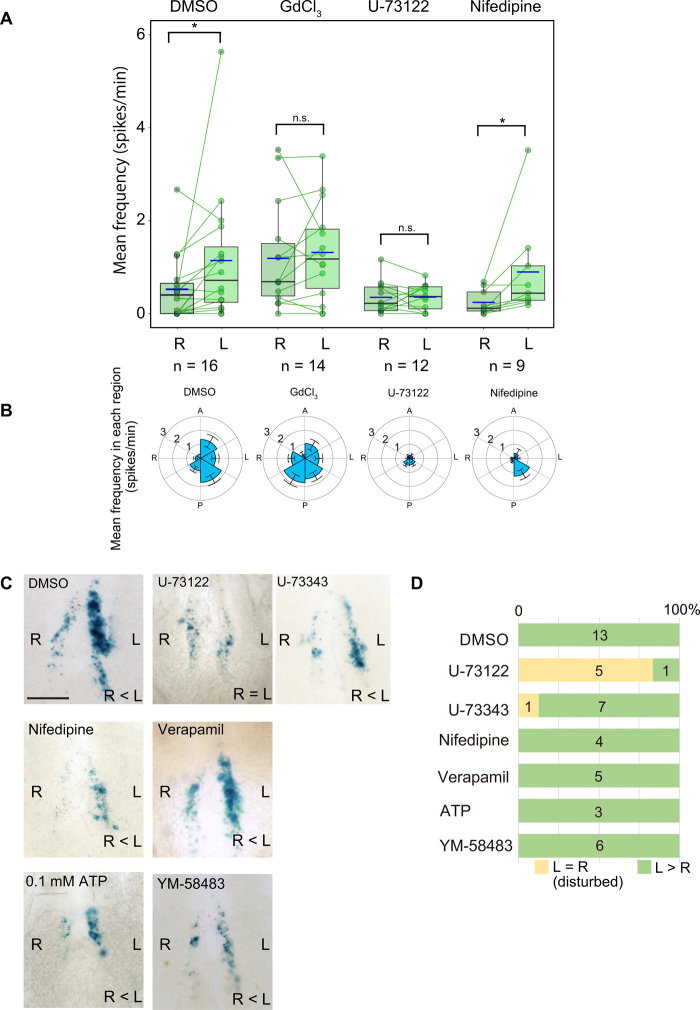

We examined various Ca2+ blockers for their effects on cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients. Whereas control embryos treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle maintained the L-R asymmetry in mean spike frequency, the total number of spikes, and the percentage of cells showing Ca2+ spikes, those treated with GdCl3, a blocker of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family of cation channels, did not (Fig. 4, A and B; fig. S6, A, B, and E; and movie S13), suggesting that a member of the TRP family, which includes PKD2, may contribute to the L-R asymmetry of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients. We also tested the effects of U-73122, an inhibitor of phospholipase C, given that the generation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) by this enzyme, which triggers the release of Ca2+ from the ER, has been implicated in the breaking of L-R symmetry at the L-R organizer in mouse and Xenopus (6, 22). Treatment with U-73122 markedly reduced the mean spike frequency, the total number of spikes, and the percentage of cells showing Ca2+ spikes, but it also abolished the L-R asymmetry in cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (Fig. 4, A and B; fig. S6, A and B; and movie S13). L-R asymmetry in Nodal activity at the node, as revealed with a LacZ transgene under the control of the upstream region of human Lefty1 (ANE-LacZ) (23), was also disrupted by treatment of embryos with U-73122. Whereas ANE-LacZ was expressed on the left side of the node in DMSO-treated embryos, it thus showed symmetric expression in embryos treated with U-73122 (Fig. 4, C and D). On the other hand, U-73343, an inactive analog of U-73122, did not substantially affect the pattern of ANE-LacZ expression (Fig. 4, C and D). GdCl3 and U-73122 suppressed asymmetric Nodal expression in the left lateral plate mesoderm (LPM), while U-73343 did not significantly affect (fig. S6, G and H). Neither GdCl3 nor U-73122 impaired the leftward nodal flow (fig. S6F), suggesting that motility of motile cilia was not affected by these reagents. Collectively, our results thus suggested that nodal flow, the PKD2 channel, cilia, and the IP3 pathway are required for the generation of L-R asymmetry in cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in crown cells at the node of mouse embryos.

Fig. 4. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients related to L-R determination depend on TRP cation channels and the IP3 pathway.

(A) Mean frequency of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (as revealed by RGECO1 fluorescence) in crown cells on the left or right side of the node of mouse embryos treated with DMSO vehicle, GdCl3 (500 μM), U-73122 (25 μM), or nifedipine (10 μM). Each dot indicates the mean frequency value for the left or right side of a single embryo, with the two values for each embryo being connected with a line. The n values indicate the numbers of embryos analyzed. *P < 0.05; n.s. (Wilcoxon signed-rank test). (B) Circular plots of mean spike frequency for cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in embryos treated as in (A). The node region was divided into six areas according to the A-P and L-R axes. Data are means ± SEM. (C) Embryos harboring the ANE-LacZ transgene were cultured in the presence of DMSO (control), U-73122 (10 μM), U-73343 (10 μM), nifedipine (10 μM), verapamil (10 μM), ATP (0.1 mM), or YM-58483 (20 μM) and subsequently stained with the LacZ substrate X-gal. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Percentages of embryos showing asymmetric (L > R) or bilaterally equal (L = R) patterns of ANE-LacZ expression at the node. The numbers of embryos examined are also indicated.

The L-R asymmetry in cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients was unaffected by treatment of embryos with nifedipine, a blocker of L-type Ca2+ channels. Treatment with nifedipine at 10 or 100 μM thus resulted in a slight decrease in the mean frequency of Ca2+ spikes, but the L-R asymmetry remained (Fig. 4, A and B; fig. S6, C and D; and movie S13). The L-R asymmetry in the percentage of cells with Ca2+ spikes and the total spike number was also unaffected by nifedipine (fig. S6, A and B). Furthermore, the expression of ANE-LacZ remained asymmetric at the node of embryos treated with nifedipine or verapamil, another L-type Ca2+ channel blocker (Fig. 4, C and D). We also generated two different lines of knockout mice lacking the Cav1.2 subunit of L-type Ca2+ channels. These Cacna1c−/− mice did not show any obvious L-R defects (fig. S7). In addition, asymmetric expression of ANE-LacZ in crown cells was not affected by 0.1 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP) or YM-58483, an inhibitor of store-operated Ca2+ channels (Fig. 4, C and D). Together, these results suggested that L-type Ca2+ channels, purinergic calcium signaling, or store-operated Ca2+ channels are not essential for the generation of L-R asymmetry in cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in crown cells at the node.

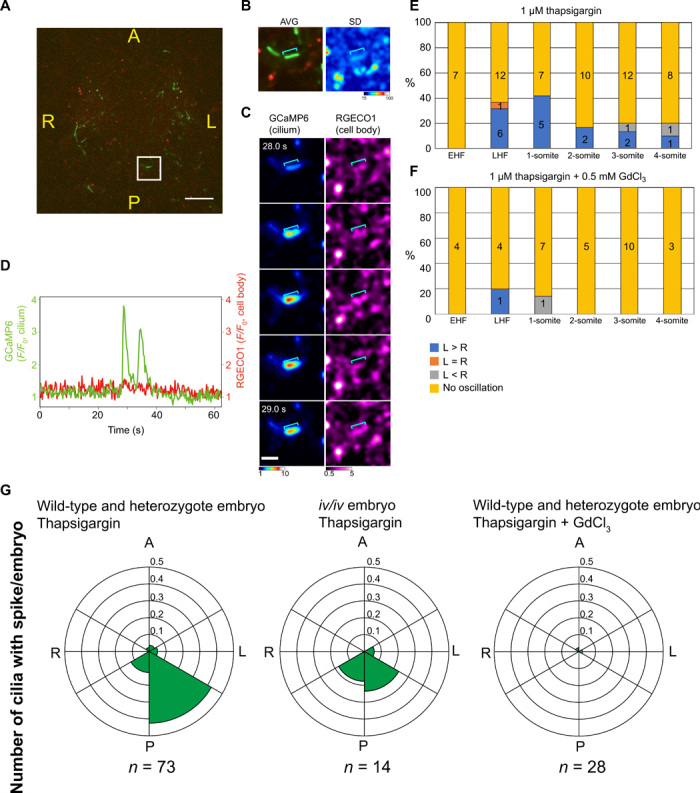

Thapsigargin-resistant intraciliary Ca2+ transients at the left posterior region of the node

To detect changes in the intraciliary Ca2+ concentration in the absence of leakage of Ca2+ from the cytoplasm, we treated embryos harboring the NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-RGECO1 transgene with thapsigargin, a Ca2+–adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) inhibitor that blocks the release of Ca2+ from ER. Exposure of embryos to 1 μM thapsigargin for 1 hour abolished cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in crown cells at the node (fig. S8A and movies S14 and 15). A similar effect was also apparent in embryos harboring an NDE4-hsp-tau-GCaMP6-IRES-LacZ transgene, which confers expression of GCaMP6 in the cell body of crown cells (movie S16), indicating that the failure to detect cytoplasmic Ca2+ spikes in thapsigargin-treated NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-RGECO1 embryos was not due to the difference between RGECO1 (~480 nM) (18) and GCaMP6 (~158 nM) (10) in the dissociation constant for Ca2+.

Whereas cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were abolished in the presence of 1 μM thapsigargin, ciliary Ca2+ transients were still detected in embryos expressing ciliary GCaMP6 (Fig. 5, A and D, and movies S17 and 18), although the number of cilia showing such transients was reduced (fig. S8B). Thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ transients were detected preferentially at the late headfold and one-somite stages only with ~40% of the embryos examined (Fig. 5E), which may be due to the short duration (~2 min) of Ca2+ imaging. Those cilia showing thapsigargin-resistant Ca2+ transients were preferentially located at the left posterior side of the node (Fig. 5G and movies S17 and S18). The velocity of the nodal flow is highest in the left posterior region of the node (14), and this region is where L-R symmetry breaking is first evident (23).

Fig. 5. Localization of cilia showing thapsigargin-resistant Ca2+ transients to the left posterior region of the node.

(A) Image of ciliary 5HT6-GCaMP6 (green) and cytoplasmic RGECO1 (red) in the node region of a wild-type mouse embryo at the late headfold stage treated with 1 μM thapsigargin. The cell within the boxed region was analyzed in (B) to (D). Scale bar, 20 μm. (B) Time-averaged fluorescence image (AVG) and SD of RGECO1 fluorescence intensity for the cell analyzed in (C) and (D). The blue line indicates the cilium. (C) Images of ciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations in a thapsigargin-treated embryo. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Time course of ciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations in the thapsigargin-treated embryo. (E and F) Percentage of embryos showing ciliary Ca2+ spikes at the indicated developmental stages, treated with either 1 μM thapsigargin (E) or 1 μM thapsigargin plus 0.5 mM GdCl3 (F). The L-R distribution of the Ca2+ spikes and the numbers of embryos studied are also indicated. EHF and LHF, early and late headfold stages, respectively. (G) Circular plots of the number of cilia showing Ca2+ transients/embryo in control (wild type and heterozygous) or iv/iv embryos at the late headfold to three-somite stage exposed to 1 μM thapsigargin with or without 0.5 mM GdCl3. The number of embryos examined (n) is indicated.

The duration of ciliary Ca2+ transients was significantly reduced by thapsigargin treatment (fig. S8C). The relation between the duration and mean frequency of ciliary Ca2+ transients also differed between DMSO- and thapsigargin-treated embryos, with Ca2+ transients of longer duration no longer being apparent in the latter embryos (fig. S8, D and E). These results suggested that ciliary Ca2+ transients detected in the absence of thapsigargin (Fig. 1) include those with an origin in the cytoplasm and those independent of the cytoplasm, the former of which are eliminated by thapsigargin treatment (Fig. 3F).

Thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ spikes were found to be dependent on the developmental stage (Fig. 5E). At the early headfold stage, no thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ spikes were detected. At the late headfold and one-somite stages, when L-R symmetry breaking takes place (23, 24), 30 to 40% of embryos had immotile cilia showing thapsigargin-resistant Ca2+ transients, with most of these cilia being found on the left side of the node (based on observation of the node for several minutes). Fewer thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ spikes were apparent at the two- or three-somite stages compared with the one-somite stage (Fig. 5F). Left-sided thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ spikes were also sensitive to GdCl3 (Fig. 5, F and G), and they were dependent on nodal flow, as revealed by their attenuation in iv/iv embryos (Fig. 5G). Their specific localization to the left posterior region of the node as well as their dependence on developmental stage, nodal flow, and TRP channels collectively suggested that thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ transients are closely associated with L-R symmetry breaking at the node.

Effects of embryo culture conditions on Ca2+ transients

While we were able to detect L-R asymmetric intraciliary Ca2+ transients at the node, such Ca2+ transients were not detected in the previous report (8). The difference in the culture condition used may account for the discrepancies between the previous work and the present study: Mouse embryos were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 75% rat serum (DR75) in our study, whereas they were cultured in DMEM-F12 (1:1) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (DF10) in the previous report (8).

Culture conditions influenced Ca2+ transients at the node and L-R patterning of mouse embryos. First, cytoplasmic and intraciliary Ca2+ transients at the node were examined after embryos between the late headfold stage and three-somite stage were cultured in DF10 medium for 1 hour. Ciliary Ca2+ transients were significantly reduced (Fig. 1D and fig. S9, A and B) and lost L-R asymmetry (Fig. 1, D and E). Cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were not detected in embryos cultured in DF10 (movie S19). Second, embryos were unable to establish molecular L-R asymmetry when they were cultured in DF10. When mouse embryos at the early headfold stage were cultured in DR75 for 16 hours, they developed to the six- to seven-somite stage and exhibited asymmetric Nodal expression in the LPM (fig. S9, C and D). However, when embryos at the early headfold stage were cultured in DF10 for 16 hours, embryos are arrested at the early headfold stage or remained at the one- to two-somite stage (fig. S9, F and G). Furthermore, they failed to establish asymmetric Nodal expression in the LPM (fig. S9, F and G). These results indicate that DF10 is not suitable for culturing mouse embryos between the early headfold and early somite stages or for observing Ca2+ transients.

Role of intraciliary Ca2+ in L-R symmetry breaking at the node

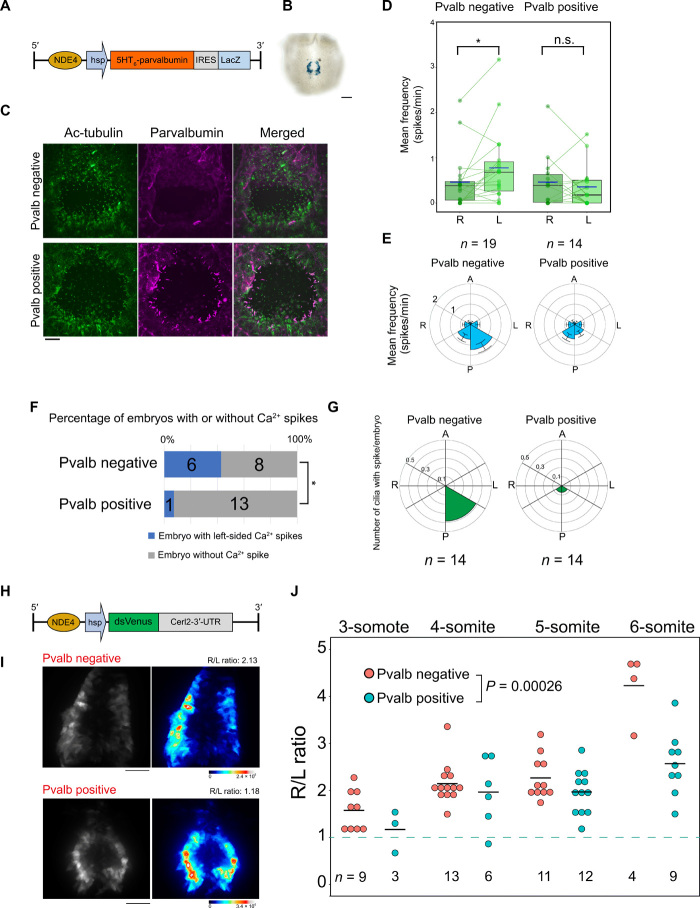

Last, we examined the role of intraciliary Ca2+ in L-R symmetry breaking using parvalbumin, which functions as a Ca2+ sink (25). Overexpression of parvalbumin has been shown to suppress Ca2+ signaling (26), and its forced expression in cilia of Kupffer’s vesicle impaired L-R patterning in zebrafish embryos (9). We established a transgenic mouse line harboring NDE4-hsp-5HT6-Parvalbumin-IRES-LacZ (Fig. 6A), which confers expression of mouse parvalbumin in cilia of crown cells at the node (Fig. 6, B and C, and fig. S10D). Examination of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients in embryos expressing cytoplasmic RGECO1 revealed that the preferential localization of these transients to the left posterior region of the node evident in the absence of parvalbumin was lost in the presence of parvalbumin (Fig. 6, D and E). Ciliary Ca2+ transients were also affected by parvalbumin. Thus, a percentage of embryos showing thapsigargin-resistant, left-sided ciliary Ca2+ transients was significantly reduced by ciliary parvalbumin (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, preferential distribution of such Ca2+ transients to the left posterior area was lost in the presence of ciliary parvalbumin (Fig. 6G). These data suggested that ciliary and cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were suppressed by ciliary parvalbumin.

Fig. 6. Suppression of Ca2+ transients in crown cell cilia disturbs L-R determination.

(A) Transgene that confers expression of ciliary parvalbumin and LacZ in crown cells. (B) Staining of a parvalbumin transgenic embryo with X-gal. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Immunohistofluorescence staining of transgenic (Pvalb positive) and nontransgenic (Pvalb negative) embryos for acetylated tubulin and parvalbumin. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Mean spike frequency for cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients on the left and right sides of the node in transgenic and nontransgenic embryos expressing RGECO1 in the cytoplasm. The n values indicate the numbers of embryos analyzed. *P < 0.05. (E) Circular plots of the mean spike frequency in the cytoplasm of crown cells of embryos shown in (D). (F) Percentages of transgenic or nontransgenic embryos showing thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ spikes. The numbers of embryos analyzed are shown.*P < 0.05 (χ2 test). (G) Circular plots of the numbers of cilia showing thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ transients, in transgenic and nontransgenic embryos. (H) Transgene designed to monitor the level of Cerl2 mRNA. The 3’-UTR of Cerl2 mRNA, which is responsible for the decay of Cerl2 mRNA, is linked to the coding sequence of Venus. (I) Live imaging of dsVenus in crown cells of transgenic and nontransgenic embryos at the five-somite stage. Raw intensity images (left) and pseudocolor sum-projection images (right) are shown. The R/L ratio of fluorescence intensity is indicated. Scale bar, 50 μm. (J) Quantitative analysis of the R/L ratio of dsVenus fluorescence intensity at the node of transgenic or nontransgenic embryos at the indicated developmental stages. The n values indicate the numbers of embryos analyzed, and black horizontal lines indicate average values. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used.

We then examined the effect of ectopic expression of parvalbumin in crown cilia on L-R symmetry breaking at the node. L-R asymmetry of Cerl2 mRNA at the node is not apparent at the three-somite stage or earlier but becomes obvious at the four-somite stage and is maintained until the six-somite stage (fig. S10A) (23). However, in the presence of ciliary parvalbumin, this asymmetry was not obvious at the four-somite stage and less apparent at the five-somite stage (fig. S10A), suggesting that the establishment of Cerl2 mRNA asymmetry at the node is delayed by ciliary parvalbumin. To monitor molecular L-R asymmetry at the node more quantitatively, we adopted another transgene, NDE4-hsp-dsVenus-Cerl2-3′-UTR, which confers expression of destabilized Venus protein (dsVenus) under the control of the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of Cerl2 mRNA (Fig. 6H) (27). Given that the level of dsVenus protein reflects that of Cerl2 mRNA, dsVenus fluorescence shows L-R asymmetry in a manner dependent on developmental stage. It is thus bilaterally equal at the early headfold stage but then gradually becomes right sided (27). Embryos without the parvalbumin transgene showed right-sided dsVenus fluorescence at the five-somite stage (Fig. 6I). Quantitation of the R/L ratio of dsVenus fluorescence revealed it to be ~1.0 at the early-somite stage and then to increase gradually as development proceeded until it reached >4.0 at the six-somite stage (Fig. 6J). However, in embryos harboring the parvalbumin transgene, the fluorescence signal was often bilateral at the five-somite stage (Fig. 6J). Quantitative analysis also showed that the developmental stage–dependent increase in the R/L ratio of dsVenus fluorescence was suppressed in the presence of parvalbumin, with this effect being especially pronounced at the six-somite stage (Fig. 6J). Asymmetric expression of Nodal in LPM at later stages was maintained in parvalbumin transgenic embryos (fig. S10), suggesting that suppression of Cerl2 mRNA decay on the left side of the node was later compensated for by other mechanisms known to amplify the small difference between the left and right sides of the node (24). It is also possible that Cerl2 is translationally repressed by a Ca2+-independent mechanism. Nonetheless, these results suggested that ectopic expression of parvalbumin in crown cell cilia suppressed ciliary Ca2+ transients and delayed the establishment of molecular L-R asymmetry at the node.

DISCUSSION

We have here detected L-R asymmetric Ca2+ transients in crown cells at the node of mouse embryos, consistent with previous observations of mouse embryos (20, 28) and zebrafish embryos (9), but inconsistent with a recent study that failed to detect ciliary Ca2+ transients at the node of mouse embryos (8). The major reason for this discrepancy relates to the culture medium for mouse embryos: DR75 containing 75% rat serum in our study, whereas DF10 in the discrepant previous study (8). Mouse embryos at the stage of L-R symmetry breaking require culture in the presence of 50 to 75% rat serum for establishment and maintenance of correct L-R asymmetry (29). Another possible contributing factor to the discrepancy between our study and the previous study relates to the difference in the dissociation constant for Ca2+ between GCaMP6 (~158 nM) (10) used in our study and G-GECO1.2 (0.45 to 1.1 μM) (8, 18) used in previous studies. In addition, GCaMP6 and mCherry were expressed as separate proteins in our study, whereas G-GECO1.2 and mCherry were expressed as a fusion protein in previous studies.

L-R asymmetric ciliary Ca2+ transients have been observed at the Kupffer’s vesicle in zebrafish embryo (9), but there are differences in Ca2+ dynamics. Ca2+ transients at the Kupffer’s vesicle are longer with a duration of ~40 s, whereas thapsigargin-resistant Ca2+ spikes at the mouse node are shorter with a duration of 2 to 3.5 s. Mean frequency at the Kupffer’s vesicle is 0.2 to 0.3 spikes/min, smaller than that at the mouse node (3 to 4 spikes/min). The reason for such differences remains unknown, but it may relate to properties of the fluid flow at the L-R organizer. For example, the fluid flow at the Kupffer’s vesicle is whirling and slower with the speed of 5 to 10 μm/s (30), while the fluid flow at the mouse node is largely linear and is faster with the speed of 15 to 20 μm/s (21). Another difference is that intraciliary Ca2+ spikes were biased toward the left anterior area of the Kupffer’s vesicle (9), while they were biased toward the left posterior area of mouse node (Figs. 1E and 5G). This may relate to differences in the geometry of the L-R organizer between two animals.

Our data suggest that crown cells at the node of mouse embryos show at least two types of Ca2+ transients: cilium-dependent, L-R asymmetric Ca2+ transients (type 1) and cilium-independent, bilaterally equal Ca2+ transients (type 2) (Fig. 3F). Type 1 ciliary Ca2+ transients are thapsigargin resistant, are dependent on nodal flow and PKD2, and take place predominantly in crown cells in the left posterior region of the node. These features suggest that these Ca2+ transients are the ones that contribute to L-R symmetry breaking at the node. Given that thapsigargin-resistant ciliary Ca2+ transients were sensitive to Gd3+, which blocks nonselective TRP channels that conduct Ca2+, they are likely attributable to Ca2+ influx via such a channel present in the ciliary membrane. PKD2 is the most likely candidate for such a channel. Although PKD2 is a nonselective cation channel present in both the ciliary membrane and ER, its presence in the ciliary membrane is essential for L-R asymmetry in mouse embryos (6, 31) as well as for preventing polycystic kidney disease in kidney epithelial cells (32).

The eventual target of type 1 intraciliary Ca2+ transients is likely Cerl2 mRNA in the cytoplasm (24, 33). The intraciliary Ca2+ may thus enter the cell body, where it may trigger the release of Ca2+ from ER in a manner dependent on the IP3 receptor. This secondary increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ would then eventually lead to the degradation of Cerl2 mRNA in crown cells on the left side of the node. The observation that treatment of mouse embryos with thapsigargin impairs L-R patterning at the node (6) suggests that the release of Ca2+ from the ER into the cytoplasm is essential for L-R asymmetry. We found that ectopic expression of a Ca2+ sink (parvalbumin) in the crown cell cilia and consequent inhibition of type 1 Ca2+ transients impaired the development of L-R asymmetry at the node. In the presence of thapsigargin, we were able to detect Ca2+ transients in cilia but not in the cytoplasm, most likely because of the huge (10,000- to 30,000-fold) difference in volume between these compartments (8, 12). The diffusion of Ca2+ from the cilium into the cytoplasm would thus not be expected to immediately result in a large increase in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration (19).

Type 2 transients were detected even in cells lacking cilia, and they did not show an L-R bias. The Ca2+ transients apparent in mutant embryos that lack either nodal flow or the PKD2 channel are thus likely type 2. The origin of type 2 Ca2+ transients is unknown, but some may originate from Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane via voltage-dependent cation channels. Whereas the precise nature of type 2 transients remains unclear, they are unlikely to contribute to L-R symmetry breaking because they do not show L-R asymmetry. We found that Cacna1c−/− mice, which lack the Cav1.2 subunit of L-type Ca2+ channels, the major voltage-dependent cation channels expressed in the mouse embryo (34), did not manifest any obvious L-R defects and that inhibitors of these channels did not disrupt L-R patterning.

The increase in the cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration associated with both type 1 and 2 Ca2+ transients would be expected to eventually lead to the degradation of Cerl2 mRNA in crown cells on the left side of the node. A relatively small L-R difference in the total extent of cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients (types 1 and 2) may be sufficient to serve as an initial asymmetric cue. Alternatively, crown cells may distinguish between type 1 and 2 Ca2+ transients. In this regard, cilium-dependent, L-R asymmetric (type 1) cytoplasmic Ca2+ transients were found to take place preferentially in the apical region of crown cells, whereas type 2 Ca2+ transients did not show such a bias. Furthermore, ER was found to be abundant in the apical region of crown cells. Given that Cerl2 mRNA is also located at the apical side of crown cells (24), it may be degraded as a result of the occurrence of apically generated type 1 Ca2+ transients.

Our data suggest that crown cells may respond to oscillatory Ca2+ transients rather than to a steady level of Ca2+. Several proteins related to Ca2+ signaling are expressed in crown cells and play an essential role in L-R asymmetry. For example, calmodulin-dependent kinase II, which senses the differential frequency of Ca2+ spikes, is required for establishment of L-R asymmetry in zebrafish (35). Inversin, mutation of which gives rise to laterality defects in the mouse, encodes a protein of unknown function with calmodulin binding motifs (36). It remains to be determined whether such proteins link Ca2+ transients to Cerl2 mRNA degradation, as well as how Cerl2 mRNA might undergo degradation in response to Ca2+ transients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Pkd2−/− and iv/iv mice were described previously (15, 16). Kif3a+/− mice (strain B6.129-Kif3a<tm1Gsn>/J) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. A DNA fragment encoding the 5HT6 sequence was provided by T. Inoue (Johns Hopkins University) (14). GCaMP6 was described previously (10). CMV-R-GECO1 was a gift from R. Campbell (Addgene plasmid #32444; http://n2t.net/addgene:32444; RRID:Addgene_32444) (18), and the 2A sequence (equine rhinitis A virus 2A peptide) (13) was synthesized as oligomer. For expression in crown cells, transgenes were placed under the control of the NDE of the mouse Nodal gene and the Hsp68 gene promoter (6, 11). The open reading frames for GCaMP6 and mCherry were each linked to DNA encoding the 5HT6 sequence for targeting to cilia, and the DNA sequence for the 2A peptide was inserted between them to yield the NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-5HT6-mCherry transgene. 5HT6-GCaMP6 and RGECO1 were also connected via the 2A peptide in a similar manner (NDE4-hsp-5HT6-GCaMP6-2A-RGECO1). For expression of parvalbumin, the mouse parvalbumin complementary DNA (cDNA) was linked to an IRES-LacZ sequence (an internal ribosome entry site linked to the β-galactosidase gene). For observation of GCaMP6 signal in cell body, NDE4-hsp-tau-GCaMP6-IRES-LacZ, in which GCaMP6 is tagged with tau (37). A transgenic mouse harboring ANE-LacZ, the 7.5-kb upstream region of the human Lefty1 gene linked to IRES-LacZ, was described previously (23). Transgenic mouse harboring a mouse Nodal-LacZ (BAC) transgene is described previously (38). For generation of transgenic mice, each transgene was microinjected into the pronucleus of fertilized eggs obtained by crossing C57BL/6J females with C57BL/6J males. Expression of the LacZ transgenes was detected by staining with X-gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-d-galactoside) (11). Two different Cacna1c mutant alleles were generated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Exon 2 of the gene was deleted with the small guide RNAs ΔEx2 gRNA1 (5′-ACATCACCAGCTCCAGTCTATGG-3′) and ΔEx2 gRNA2 (5′-AGAGAAGACAACAGTTACTATGG-3′), whereas exons 14 and 15 were deleted with ΔEx14–15 gRNA1 (5′-CATGCACGGCACTGTGCTAAAGG-3′) and ΔEx14–15 gRNA2 (5′-GCGGGTCCAGTACATAGCTCCGG-3′). Cas9 mRNA and small guide RNAs were generated by in vitro transcription with an SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (AM1340, Ambion), with minor modifications to the manufacturer’s protocol, and they were injected into fertilized eggs obtained from C57BL/6 mice. The genotypes of Cacna1c mutant pups were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the primers Cacna1c_ex2_F (5′-GGTTCAGGGATGCTTGTGAT-3′), Cacna1c_ex2_WT_R (5′-TGCTGTGTCTGACCCTGAAG-3′), and Cacna1c_ex2_MT_R (5′-ATGCGTGCTTCTCACCTCTT-3′) for ΔEx2 and Cacna1c_ex15_F (5′- CGAAATTGAACTTCCCTCCA-3′), Cacna1c_ex15_WT_R (5′-AACGCTGTGTCCCTTATTGG-3′), and Cacna1c_ex14_MT_R (5′-CCAGAAGTGTCCGCGGTAAT-3′) for ΔEx14_15. Sequences were confirmed by subsequent analysis. Cacna1c mutant mice harboring ANE-LacZ were obtained by mating. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of RIKEN Kobe Branch.

Mouse embryo culture

Embryos at ~E7.5 were collected in Hepes-buffered DMEM (pH 7.2). Those at the early headfold to early somite stages were selected and cultured by the roller culture method under 5% CO2 at 37°C in 50-ml tubes containing DMEM supplemented with 75% rat serum. Drugs were added to the medium at final concentrations of 500 μM for GdCl3 (16506-71, Nacalai Tesque), 10 or 25 μM for U-73122 (AB120998, Abcam), 10 μM for U-73343 (U6881, Sigma), 10 or 100 μM for nifedipine (N7634, Sigma), 10 μM for verapamil (V4629, Sigma), 20 μM for YM-58483 (Y4895, Sigma), 0.1 mM for ATP (A9187, Sigma), and 1 μM for thapsigargin (T9033, Sigma). For X-gal staining of ANE-LacZ embryos, the embryos were maintained in medium containing nifedipine or verapamil from the early headfold to the four- to six-somite stage, whereas they were cultured with U-73122 or U-73343 for 3 hours and then without drug until they reached the four- to six-somite stage. For Nodal-LacZ embryos, GdCl3, U-73122, and U-73343 were included in the culture medium from the early headfold stage to the four- to six-somite stage. Drug treatment for live imaging is described below.

Immunofluorescence analysis

E7.5 mouse embryos were recovered in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 1 hour at 4°C in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde. Fixed embryos were dehydrated and permeabilized in 1 ml of methanol for 10 min at −20°C and were then exposed for 1 hour at room temperature to TNB blocking buffer consisting of 0.1 M tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl, and 0.5% TSA blocking reagent (FP1020, PerkinElmer). The embryos were incubated for 2 hours at room temperature first with primary antibodies and then with secondary antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer. Primary antibodies included those to parvalbumin (1:200 dilution; MAB1572, Merck), to acetylated tubulin (1:200 dilution; rabbit: #3971S, Cell Signaling Technology; mouse: T6793, Sigma), to PDI (1:500 dilution; 11245-1-AP, Proteintech), and to green fluorescent protein (GFP) (1:250 dilution; ab13970, Abcam). The primary antibodies were detected with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 dilution; anti-rabbit; A11034, Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor 568 (1:500 dilution; anti-mouse; A11004, Invitrogen), or Alexa Fluor 488 (1:500 dilution; anti-chick; ab150173, Abcam). After incubation with secondary antibodies, embryos were washed five times (5 min each time) with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. A portion of each embryo including the node was excised and mounted in the wash buffer on a glass slide that was fitted with a silicone rubber spacer and covered with a coverslip for observation with an Olympus IX83 microscope equipped with a spinning disc confocal unit (CSU-W1, Yokogawa) and a 60× lens [UPLSAPO 60XW 1.2 numerical aperture (NA), Olympus]. For observation of ER structures in crown cells, embryos stained for PDI and ZO-1 were observed with Zeiss LSM 880 with an Airyscan confocal microscope equipped with 63× (Plan-Apochromat 63× Oil for SR 1.4 NA) and 100× (alpha Plan-Apochromat 100× Oil for SR 1.46 NA) lenses. For observation of ER in live embryo, embryos were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 75% rat serum with addition of 1 μM ER-Tracker Red (E34250, Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 hours at 37°C, washed with PBS for several times, and observed with CSU-W1/IX83 with 60× lens (UPLSAPO 60XW 1.2 NA, Olympus) in 75% rat serum/DMEM.

Ca2+ imaging

Embryos were collected at E7.5 in Hepes-buffered DMEM (pH 7.2) supplemented with 10% FBS and then maintained in DMEM supplemented with 75% rat serum (pH 7.2) until use. Embryos between the late headfold stage and three-somite stage were used unless otherwise mentioned. A distal portion of each embryo including the node was excised, placed into a chamber consisting of a glass slide fitted with a silicone rubber spacer (thickness of 200 μm) and covered with a coverslip, and incubated under 5% CO2 at 37°C in DMEM supplemented with 75% rat serum in the absence or presence of either 0.5% DMSO vehicle or 1 μM thapsigargin, 500 μM GdCl3, 25 μM U-73122, or 10 or 100 μM nifedipine. The duration of drug treatment was at least 30 min but not more than 1 hour. Ca2+ imaging at the node was performed with an Olympus IX83 microscope equipped with a spinning disc confocal unit (CSU-W1, Yokogawa). GCaMP6 was detected with a laser (wavelength of 488 nm) and a 520/35 filter set. mCherry and RGECO1 were detected with a laser (wavelength of 561 nm) and a 617/73 filter set. Observation of ciliary GCaMP6 and mCherry was performed with a water immersion objective (UPLSAPO 60XW, Olympus), whereas that of ciliary GCaMP6 and cytoplasmic RGECO1 was performed with a silicone immersion objective (UPLSAPO 40XS, Olympus). Embryos were allowed to adjust to the observation chamber for at least 10 min before observation. Images were recorded simultaneously with two synchronized electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) cameras (iXon Ultra 888, Andor). Exposure time was set to 200 ms, and XYT images were obtained at a rate of 4 frames/s. The duration of observation was ~2 min, and movies were obtained from several depths within the range of 15 to 25 μm from the base of the node. If necessary, XYZT images were obtained with a piezo actuator (Physik Instrumente), with a Z depth of 1.5 μm and with seven or eight sections. Time resolution for XYZT images was adjusted to ~800 ms, with a 50-ms exposure for each plane. All supplementary movies were processed with a Gaussian filter (σ = 2 for cytoplasmic RGECO1, σ = 1 for ciliary GCaMP6, tau-GCaMP6, ER-Tracker Red) for denoising.

Analysis of Ca2+ transients

Sixteen-bit multi-tiff images were analyzed with Fiji/ImageJ [version 1.52e; National Institutes of Health (NIH)]. For the analysis of ciliary Ca2+ transients, the fluorescence intensity of 5HT6-GCaMP6 or 5HT6-mCherry in the cilium was corrected by subtraction of the background signal outside of the cilium. A region of interest (ROI) was set for each cilium, and the fluorescence intensity at a given time was obtained from filtered images as the mean value for all pixels in the ROI. XYT images were analyzed unless indicated otherwise. For ratiometric analysis, the GCaMP6/mCherry ratio was calculated for each time point. F0 was measured in the resting state and was used to estimate F/F0. An F/F0 ratiometric change of >2.0 was defined as a peak. The mean frequency denotes the number of spikes per minute, and the peak intensity is the maximum F/F0 value of each peak. The percentage of cilia showing Ca2+ spikes was calculated from the number of ROIs showing peaks and the total number of ROIs examined. Peak duration was estimated with Igor Pro 7 (WaveMetrics). Each peak was fitted to an exponentially modified Gaussian distribution with the multipeak fitting package, and the peak duration was defined as the width (time) at the position corresponding to 25% of the maximal peak height. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ was analyzed similarly. The F0 value was measured in the resting state, and F/F0 values were determined from RGECO1 intensity changes calculated from the mean value of all pixels in the ROI. Intensity changes with an F/F0 value of >1.6 were defined as cytoplasmic peaks. Peak parameters such as frequency, intensity, and duration were analyzed in a similar manner as for ciliary Ca2+.

Imaging and analysis of dsVenus

The node region of embryos harboring NDE4-hsp-dsVenus-Cerl2-3′-UTR was observed with an Olympus IX83/CSU-W1 microscope equipped with a UPLSAPO 40XS lens. Images were obtained by laser excitation at a wavelength of 488 nm and detection with a 520/35 filter unit. Z depth was set to 0.20 μm per section, and the dsVenus signal was obtained for the entire region of the node with 200-ms exposures with an Andor iXon Ultra 888 EMCCD camera (depth of ~50 μm, ~200 sections). The sum of XYZ images was obtained with Fiji/ImageJ (version 1.52e; NIH) as a 32-bit image. ROIs were set so as to include all crown cells on the left or right side of the node, and cells with fluorescence were selected. The mean signal intensity was measured for the left and right sides of the node, and the L/R ratio of the mean intensity was then determined.

PIV analysis

Nodal flow was observed with an IX83/CSU-W1 microscope equipped with UPLanSAPO 60× Oil lens and EMCCD camera as mentioned above, and particle image velocimetry (PIV) analysis was performed as described previously (14). The excised node region was treated with 75% rat serum/DMEM containing 0.2-μm fluorescence beads (505/515; F8811, Invitrogen), and the nodal cavity was filled with the medium containing the beads. The motion of the beads was monitored in planes of ~10 μm above the surface of node pit cells.

FIB-SEM

Samples for FIB-SEM were prepared and observed as previously described (39). A mouse embryo at one-somite stage was collected in ice-cold PBS and fixed immediately at 4°C overnight in fresh 2% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). It was then incubated in ice-cold 2% OsO4 for 120 min and embedded in resin. After smoothing the surface of the embedding by ultramicrotome, the obtained specimen was observed with Helios G4 UC (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed, and graphs were drawn with R (version 3.6.1; www.R-project.org) and the ggplot2 package (40). The statistical tests adopted are described in the figure legends. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Iino, K. Kanemaru, and T. Kurahashi for reviewing our data on Ca2+ transients and for constructive comments. Funding: This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (no. 17H01435) and from Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (no. JPMJCR13W5) to H.H., as well as by a Grant-in-Aid (no. 17K15154) for Young Scientists (B) and a Grant-in-Aid (no. 19K06753) for Scientific Research (C) to K.Miz. from MEXT. This work was also supported by the National Institute for Basic Biology Individual Collaborative Research Program (19-333) to K.Miz. Author contributions: K.Miz. and H.H. designed the project and wrote the manuscript. K.Miz. performed most experiments and analyzed the data. K.S. performed the initial part of Ca2+ analysis. T.A.K. contributed to analysis of Ca2+ transient data. K.Min. analyzed the data obtained with dsVenus transgenic mice. J.N. analyzed early data for Ca2+ transients obtained with the GCaMP6 reporters. Y.I., H.N., and H.S. generated transgenic mice expressing Ca2+ reporters. K.T. generated Cacna1c mutant mouse. T.Id., T.It., and A.H.I. performed FIB-SEM. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript. Competing interests: J.N. is an inventor on a patent related to this work [Japanese Patent No. 5788160 (P5788160), filed on 10 October 2010, published on 7 August 2015]. The authors declare no other competing interests. Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in this paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/30/eaba1195/DC1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Anvarian Z., Mykytyn K., Mukhopadhyay S., Pedersen L. B., Christensen S. T., Cellular signalling by primary cilia in development, organ function and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 15, 199–219 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singla V., Reiter J. F., The primary cilium as the cell’s antenna: Signaling at a sensory organelle. Science 313, 629–633 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pala R., Alomari N., Nauli S. M., Primary cilium-dependent signaling mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2272 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fliegauf M., Benzing T., Omran H., When cilia go bad: Cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 880–893 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blum M., Feistel K., Thumberger T., Schweickert A., The evolution and conservation of left-right patterning mechanisms. Development 141, 1603–1613 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshiba S., Shiratori H., Kuo I. Y., Kawasumi A., Shinohara K., Nonaka S., Asai Y., Sasaki G., Belo J. A., Sasaki H., Nakai J., Dworniczak B., Ehrlich B. E., Pennekamp P., Hamada H., Cilia at the node of mouse embryos sense fluid flow for left-right determination via Pkd2. Science 338, 226–231 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norris D. P., Jackson P. K., Cell biology: Calcium contradictions in cilia. Nature 531, 582–583 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delling M., Indzhykulian A. A., Liu X., Li Y., Xie T., Corey D. P., Clapham D. E., Primary cilia are not calcium-responsive mechanosensors. Nature 531, 656–660 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan S. L., Zhao L., Brueckner M., Sun Z. X., Intraciliary calcium oscillations initiate vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Curr. Biol. 25, 556–567 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohkura M., Sasaki T., Sadakari J., Gengyo-Ando K., Kagawa-Nagamura Y., Kobayashi C., Ikegaya Y., Nakai J., Genetically encoded green fluorescent Ca2+ indicators with improved detectability for neuronal Ca2+ signals. PLOS ONE 7, e51286 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krebs L. T., Iwai N., Nonaka S., Welsh I. C., Lan Y., Jiang R., Saijoh Y., O’Brien T. P., Hamada H., Gridley T., Notch signaling regulates left-right asymmetry determination by inducing Nodal expression. Genes Dev. 17, 1207–1212 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su S., Phua S. C., DeRose R., Chiba S., Narita K., Kalugin P. N., Katada T., Kontani K., Takeda S., Inoue T., Genetically encoded calcium indicator illuminates calcium dynamics in primary cilia. Nat. Methods 10, 1105–1107 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J. H., Lee S.-R., Li L.-H., Park H.-J., Park J.-H., Lee K. Y., Kim M.-K., Shin B. A., Choi S. Y., High cleavage efficiency of a 2A peptide derived from porcine teschovirus-1 in human cell lines, zebrafish and mice. PLOS ONE 6, e18556 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinohara K., Kawasumi A., Takamatsu A., Yoshiba S., Botilde Y., Motoyama N., Reith W., Durand B., Shiratori H., Hamada H., Two rotating cilia in the node cavity are sufficient to break left-right symmetry in the mouse embryo. Nat. Commun. 3, 622 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennekamp P., Karcher C., Fischer A., Schweickert A., Skryabin B., Horst J., Blum M., Dworniczak B., The ion channel polycystin-2 is required for left-right axis determination in mice. Curr. Biol. 12, 938–943 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Supp D. M., Witte D. P., Potter S. S., Brueckner M., Mutation of an axonemal dynein affects left-right asymmetry in inversus viscerum mice. Nature 389, 963–966 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okada Y., Nonaka S., Tanaka Y., Saijoh Y., Hamada H., Hirokawa N., Abnormal nodal flow precedes situs inversus in iv and inv mice. Mol. Cell 4, 459–468 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao Y., Araki S., Wu J., Teramoto T., Chang Y.-F., Nakano M., Abdelfattah A. S., Fujiwara M., Ishihara T., Nagai T., Campbell R. E., An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science 333, 1888–1891 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delling M., DeCaen P. G., Doerner J. F., Febvay S., Clapham D. E., Primary cilia are specialized calcium signalling organelles. Nature 504, 311–314 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takao D., Nemoto T., Abe T., Kiyonari H., Kajiura-Kobayashi H., Shiratori H., Nonaka S., Asymmetric distribution of dynamic calcium signals in the node of mouse embryo during left-right axis formation. Dev. Biol. 376, 23–30 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nonaka S., Tanaka Y., Okada Y., Takeda S., Harada A., Kanai Y., Kido M., Hirokawa N., Randomization of left-right asymmetry due to loss of nodal cilia generating leftward flow of extraembryonic fluid in mice lacking KIF3B motor protein. Cell 95, 829–837 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatayama M., Mikoshiba K., Aruga J., IP3 signaling is required for cilia formation and left-right body axis determination in Xenopus embryos. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 410, 520–524 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawasumi A., Nakamura T., Iwai N., Yashiro K., Saijoh Y., Belo J. A., Shiratori H., Hamada H., Left-right asymmetry in the level of active Nodal protein produced in the node is translated into left-right asymmetry in the lateral plate of mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 353, 321–330 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakamura T., Saito D., Kawasumi A., Shinohara K., Asai Y., Takaoka K., Dong F., Takamatsu A., Belo J. A., Mochizuki A., Hamada H., Fluid flow and interlinked feedback loops establish left-right asymmetric decay of Cerl2 mRNA. Nat. Commun. 3, 1322 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwaller B., The continuing disappearance of “pure” Ca2+ buffers. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 275–300 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.John L. M., Mosquera-Caro M., Camacho P., Lechleiter J. D., Control of IP(3)-mediated Ca2+ puffs in Xenopus laevis oocytes by the Ca2+-binding protein parvalbumin. J. Physiol. 535, 3–16 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.K. Minegishi, B. Rothé, K. R. Komatsu, H. Ono, Y. Ikawa, H. Nishimura, E. Miyashita, K. Takaoka, K. Bando, H. Kiyonari, T. Yamamoto, H. Saito, D. B. Constam, H. Hamada, Fluid flow-induced left-right asymmetric decay of Dand5 mRNA in the mouse embryo requires Bicc1-Ccr4 RNA degradation complex. bioRxiv 2020.02.02.931477 [Preprint]. 3 February 2020.

- 28.McGrath J., Somlo S., Makova S., Tian X., Brueckner M., Two populations of node monocilia initiate left-right asymmetry in the mouse. Cell 114, 61–73 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.R. Behringer, M. Gertsenstein, K. V. Nagy, A. Nagy, Manipulating the Mouse Embryos: A Laboratory Manual (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, ed. 4, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampaio P., Ferreira R. R., Guerrero A., Pintado P., Tavares B., Amaro J., Smith A. A., Montenegro-Johnson T., Smith D. J., Lopes S. S., Left-right organizer flow dynamics: How much cilia activity reliably yields laterality? Dev. Cell 29, 716–728 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Field S., Riley K.-L., Grimes D. T., Hilton H., Simon M., Powles-Glover N., Siggers P., Bogani D., Greenfield A., Norris D. P., Pkd1l1 establishes left-right asymmetry and physically interacts with Pkd2. Development 138, 1131–1142 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walker R. V., Keynton J. L., Grimes D. T., Sreekumar V., Williams D. J., Esapa C., Wu D., Knight M. M., Norris D. P., Ciliary exclusion of Polycystin-2 promotes kidney cystogenesis in an autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease model. Nat. Commun. 10, 4072 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schweickert A., Vick P., Getwan M., Weber T., Schneider I., Eberhardt M., Beyer T., Pachur A., Blum M., The nodal inhibitor Coco is a critical target of leftward flow in Xenopus. Curr. Biol. 20, 738–743 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seisenberger C., Specht V., Welling A., Platzer J., Pfeifer A., Kühbandner S., Striessnig J., Klugbauer N., Feil R., Hofmann F., Functional embryonic cardiomyocytes after disruption of the L-type α1C (Cav1.2) calcium channel gene in the mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 39193–39199 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Francescatto L., Rothschild S. C., Myers A. L., Tombes R. M., The activation of membrane targeted CaMK-II in the zebrafish Kupffer’s vesicle is required for left-right asymmetry. Development 137, 2753–2762 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mochizuki T., Saijoh Y., Tsuchiya K., Shirayoshi Y., Takai S., Taya C., Yonekawa H., Yamada K., Nihei H., Nakatsuji N., Overbeek P. A., Hamada H., Yokoyama T., Cloning of inv, a gene that controls left/right asymmetry and kidney development. Nature 395, 177–181 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hadjantonakis A. K., Pisano E., Papaioannou V. E., Tbx6 regulates left/right patterning in mouse embryos through effects on nodal cilia and perinodal signaling. PLOS ONE 3, e2511 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takaoka K., Yamamoto M., Shiratori H., Meno C., Rossant J., Saijoh Y., Hamada H., The mouse embryo autonomously acquires anterior-posterior polarity at implantation. Dev. Cell 10, 451–459 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.T. M. Ichinose, A. H. Iwane, Cytological analyses by advanced electron microscopy, in Cyanidioschyzon merolae: A New Model Eukaryote for Cell and Organelle Biology, T. Kuroiwa, S. Miyagishima, S. Matsunaga, N. Sato, H. Nozaki, K. Tanaka, O. Misumi, Eds. (Springer, 2017), pp. 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- 40.D. E. Wickham, ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer-Verlag, 2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/6/30/eaba1195/DC1