Abstract

Complete interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency is a monogenic primary immunodeficiency caused by IFNGR1 germline defects, with autosomal dominant or recessive inheritance, which results in invasive mycobacterial diseases with varying degrees of severity. Most of the autosomal recessive IFNGR1 mutations are homozygous loss-of-function single-nucleotide variants, whereas large genomic deletions and compound heterozygosity have been very rarely reported. Herein we describe the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and successful treatment with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation of a child with disseminated Mycobacterium avium infection due to compound heterozygosity for a subpolymorphic copy number variation and a novel splice-site variant.

Keywords: IFNGR1 gene , compound heterozygosity, copy number variation

Introduction

Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease (MSMD) is a group of rare primary immunodeficiency diseases affecting both the cellular network (macrophage, T cells, and natural killer [NK]) and the interferon-γ (IFN-γ)/interleukin-12 (IL-12) signaling pathway, which play a key role in innate immune defense against intracellular pathogens. MSMD patients typically show disseminated infections due to bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG), M. tuberculosis , environmental nontuberculous atypical mycobacteria, other intramacrophagic bacteria ( Listeria monocytogenes , Salmonella spp.), fungi ( Candida spp.), parasites, and few viruses. 1 2 3 Since 1996, when the genetic etiology of a case of disseminated infection with BCG was first reported in a child, 4 5 various forms of germline mutations (single-nucleotide variations, small deletions, duplications, insertions, indels, and copy number variations [CNVs]) in 11 genes have been shown to cause 21 different forms of MSMDs. Moreover, numerous new mutations associated with 18 disorders have been recently reported, and it is very likely that the knowledge of MSMDs is far to be complete. 6 INF-γ receptor 1 (IFN-γR1) deficiency (OMIM: 107470) is a rare (8%) 1 subtype of MSMD caused by biallelic or monoallelic mutations in the IFNGR1 gene (chromosome 6q23.3), 7 mostly resulting in stop codons, which can be inherited either in an autosomal recessive (AR; immunodeficiency 27A, IMD27A; MIM# 209950) or autosomal dominant (AD; immunodeficiency 27B, IMD27B; MIM# 615978) manner. 8 Forty-one IFNGR1 mutations have been identified so far. All AD monoallelic mutations ( n = 8) and one AR biallelic mutation recently reported 9 have been identified in exon 6, whereas the remaining 32 AR mutations (complete n = 28; partial n = 4) are distributed across all the other exons. 1 8 The genetic pattern of IFNGR1 defines the clinical features of IFN-γR1 deficiency in terms of disease severity and treatment approach because recessive and dominant IFN-γR1 deficiencies share clinical phenotypes but have different severity in terms of age at onset, dissemination, and clinical course of mycobacterial diseases. Complete AR absence of IFN-γR1, which is the most severe form of the disease, is characterized by early onset, serious infections (usually disseminated and recurrent BCG or low-virulent mycobacterial infections), and extremely poor prognosis, with high mortality in early childhood. 1 10 11 Patients with partial deficiency (AD or AR partial) have a milder clinical presentation, with later onset, less severe infections responsive to antibiotic therapy, and better survival rates. 10 12 Regardless of the genetic pattern, IFNGR1 mutations lead to a lack of expression or function of the IFN-γR1 receptor. 13 As a result, macrophages fail to be activated on exposure to IFN-γ stimulation from T- and NK cells, and the host becomes highly susceptible to mycobacterial and intramacrophagic pathogens. 1 13 Impaired cytokine production, such as IL-12 or tumor necrosis factor-α, leads to high levels of circulating IFN-γ, particularly during the acute phase of infection, whereas IFN-γ is usually undetectable in the serum of healthy individuals. 14 The overall prognosis of patients with complete IFN-γR1 deficiency remains tremendously dismal, and three cases of malignancy (lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, and pineal germinoma) have also been reported. 15 16 17 Because of the lack of IFN-γR1, in complete AR IFNGR1 deficiency, recombinant IFN-γ therapy is inefficient. Although the feasibility of hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for IFN-γR1 deficiency has been recently proven in mice, supporting its possible use in humans, 18 the only current curative option for complete IFN-γR1 deficiency is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). Nevertheless, the prognosis remains poor even after HSCT. Due to the high concentrations of circulating IFN-γ, the rate of graft rejection is extremely high even for transplants from a human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-identical relative. 19 20 21 Together with the circulating levels of IFN-γ before HSCT, optimal control of mycobacterial infection, type of donor, and myeloablative conditioning are reported as the most important factors associated with a favorable outcome. 22 23 24 25 Herein we describe the clinical presentation, diagnostic approach, and successful treatment with HSCT from matched unrelated donor (MUD) of a child with complete IFN-γR1 deficiency due to compound heterozygosity for a novel acceptor splice-site variant and a whole gene deletion diagnosed through a combination of molecular and cytogenetic techniques.

Case Report

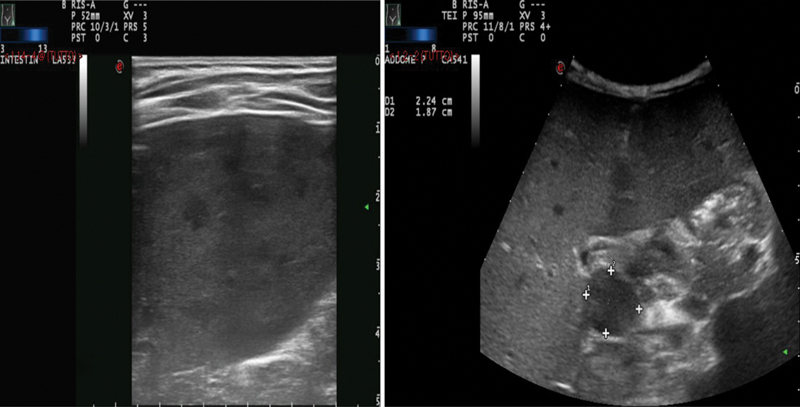

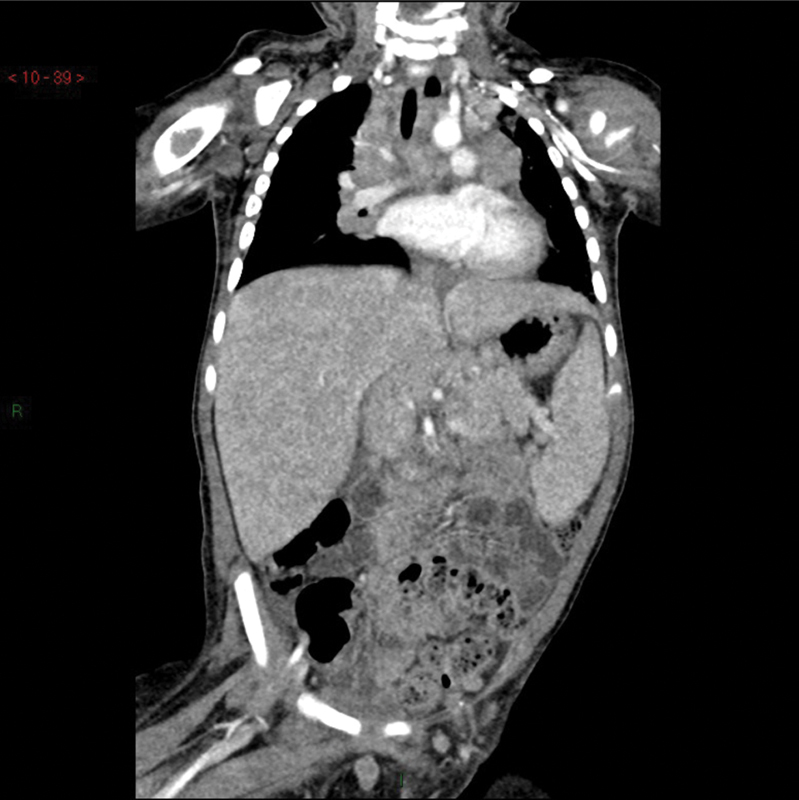

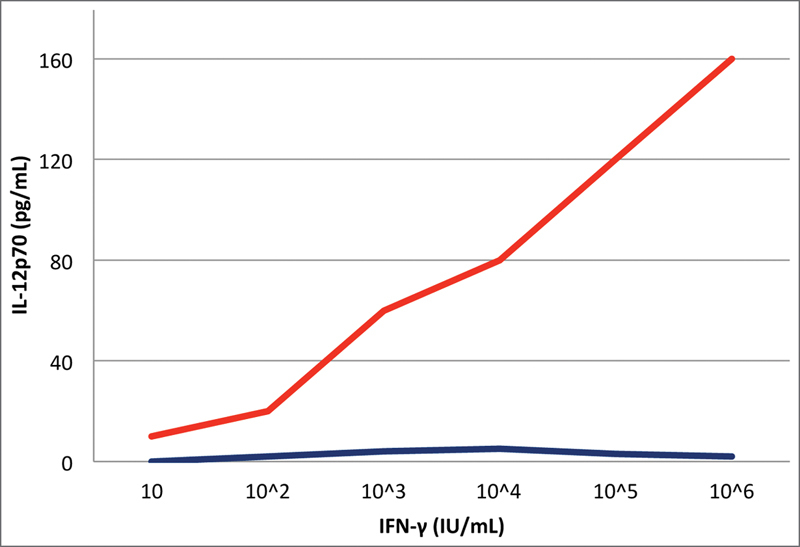

An 18-month-old male patient, born to healthy nonconsanguineous Italian parents, was referred to our hospital for prolonged fever resistant to antibiotics, weight loss, and hepatosplenomegaly suspected for a lymphoproliferative disease. His personal and family medical history was unremarkable until the age of 15 months. On admission, the child was febrile (38°C), pale, and severely wasted, and his liver and spleen were enlarged to 5 cm below the rib cage. Laboratory examination findings revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin: 6.1 g/dL), hyperleukocytosis (white blood cell count: 34.650/mm 3 ) with neutrophilia (19.400/mm 3 ) and eosinophilia (8.100/mm 3 ), high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (80 mm/hour; normal value: < 10), high C-reactive protein (17.57 mg/dL; normal value < 0.6), and high LDH (lactate dehydrogenase, 479 mU/mL; normal value: 125–220). Serum hepatic enzymes ALT (aminotransferase) and AST (aspartate aminotransferase) were normal, whereas GGT (gamma-glutamyl transferase) was 216 mU/mL (normal value: 11–53) and albumin:globulin ratio was inverted (albumin: 2.1 g/dL; gamma-globulin: 1.9 g/dL) with high immunoglobulin G (IgG: 2010 mg/dL). Infective work-up excluded Brucella, Leishmania, Rickettsia, Bartonella, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein–Barr virus, fungi, and HIV infections. The abdominal ultrasound (US) examination showed the presence of multiple focal hypoechoic lesions in the spleen and multiple lymphadenopathies. US and computed tomography (CT) imaging studies confirmed massive hepatosplenomegaly (liver: 12 cm, spleen: 9 cm) and the presence of multiple focal hypoechoic lesions in the spleen, along with multiple enlarged lymph nodes ( Figs. 1 and 2 ). Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT showed liver and spleen hypercaptation, with multiple intensely hypermetabolic lymph nodes at the mediastinal and abdominal sites. T-cell subset distribution, T-cell response to mitogens, and serum immunoglobulin levels were all normal (except for IgG). Perforin ( PRF1 ) expression on NK cells at flow cytometry was very low (3–7%), suggesting the possible diagnosis of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis type 2, which was excluded by the molecular analysis of PRF1 . Neutrophil respiratory burst test with dihydrorhodamine flow cytometry was normal, excluding chronic granulomatous disease. Mesenteric lymph node and liver biopsies were performed, showing nonspecific reactive changes, without signs of malignancy, granulomas, or hemophagocytosis. Bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were negative. The detection of Mycobacterium avium infection (MAI) in cultures of liver and mesenteric lymph nodes led to clinical suspicion of MSMD. Functional assays revealed a high level of IFN-γ in the plasma of the patient (1,900 pg/µL; normal value < 10), as typically observed in MSMD patients' sera, whereas IFN-γ levels were in the normal range in both parents. To determine whether the IFN-γ pathway was functional, we stimulated a sample of whole blood of our patient with increasing doses of IFN-γ and lipopolysaccharide showing that IL-12p70 production in vitro response was completely abolished ( Fig. 3 ). The genetic analysis showed that the child had compound heterozygosity for a subpolymorphic CNV and a novel splice-site variant (see below). On the basis of the diagnosis of disseminated MAI infection in complete IFN-γR1 deficiency, the child was put on empiric antimycobacterial treatment with four intravenous agents: clarithromycin, ethambutol, rifabutin, and amikacin. When the results of the susceptibility tests became available, clarithromycin, ethambutol, and rifabutin were continued and amikacin was replaced with moxifloxacin. Treatment was well tolerated without side effects; visual and hearing functions were strictly monitored, and no impairment was detected. Treatment was effective: the clinical condition dramatically improved, fever gradually disappeared, and oral feeding replaced parenteral nutrition. Hepatosplenomegaly progressively reduced with reversal of the intrasplenic hypoechoic lesions evident at US. The hematological parameters and the acute phase reactants returned to normal values. Plasma IFN-γ concentration dramatically decreased to undetectable levels. To reduce the mycobacterial load and prevent the stem cell trapping into the spleen, splenectomy was performed 1 month before the HSCT. Spleen tissue culture was negative for mycobacteria. Five months after the diagnosis and the start of antimycobacterial therapy, HSCT was performed. The bone marrow graft came from a 10/10 antigens (A, B, C, DRB1, and DQB1) MUD at high-resolution HLA typing. The conditioning regimen included thiotepa (5 mg/kg × 2 on day 7), treosulfan (14 g/m 2 on days 6, 5, 4), fludarabine (40 mg/m 2 on days 6, 5, 4, 3), and rabbit antithymocyte globulin (Grafalon; 5 mg/kg on days 5, 4, 3). Antimycobacterial therapy was continued for approximately 9 months after HSCT. At the time of writing, 33 months after HSCT, the child is well, with no signs of active mycobacterial infection and full donor chimerism.

Fig. 1.

Abdominal ultrasound showing hepatosplenomegaly with multiple focal hypoechoic lesions in the spleen (left) and multiple lymphadenopathies (right).

Fig. 2.

Computed tomography scan showing liver and spleen enlargement with parenchymal inhomogeneity, multiple massive intra-abdominal, and intrathoracic lymph nodes.

Fig. 3.

In vitro IL-12p70 production in response to stimulation with lipopolysaccharide plus various concentrations of interferon γ (IFN-γ) in our patient ( blue ) and a healthy control ( red ).

Materials and Methods

Molecular Karyotyping

Array-CGH (comparative genomic hybridization) was performed on DNA samples extracted from peripheral blood (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) using a whole-genome 244K Agilent array (Human Genome CGH Microarray, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, California, United States) according to manufacturer's protocol. Data were analyzed using the Agilent Genomic Workbench Standard Edition 6.5.0.58. All genomic positions are reported according to the human genome reference sequence (GRCh37/hg19).

IFNGR1 Molecular Analysis

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed with the AmpliTaq Gold Polymerase Kit (Life Technologies, Foster City, California, United States) in a final volume of 25 μL containing 50 ng of genomic DNA using primers specifically designed with Primer3Plus. Sequencing reactions were performed using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit on an automated sequencer (3730 DNA Analyzer, Applied Biosystems).

Complementary DNA Analysis

Peripheral blood was collected in Tempus Blood RNA Tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rodano, Italy) containing a specific stabilizing reagent that inactivates cellular RNases and selectively precipitates RNA. Before RNA purification, stabilized blood samples were processed as recommended by the manufacturer. RNA was extracted from 3 mL of peripheral blood samples using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's specifications and including on-column DNase treatment. After Nanodrop's quantification and quality-check, 500 ng of purified RNA were reverse-transcribed into single-stranded complementary DNA (cDNA) using the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, California, United States) in a final volume of 20 µL according to the manufacturer's instructions. Thereafter, cDNA concentration was measured using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PCR amplification and sequencing of the cDNA region containing the IFNGR1 germline mutation as well as the housekeeping gene (ACTB) were performed as for genomic DNA analysis.

Genetic Results

Genetic Analysis

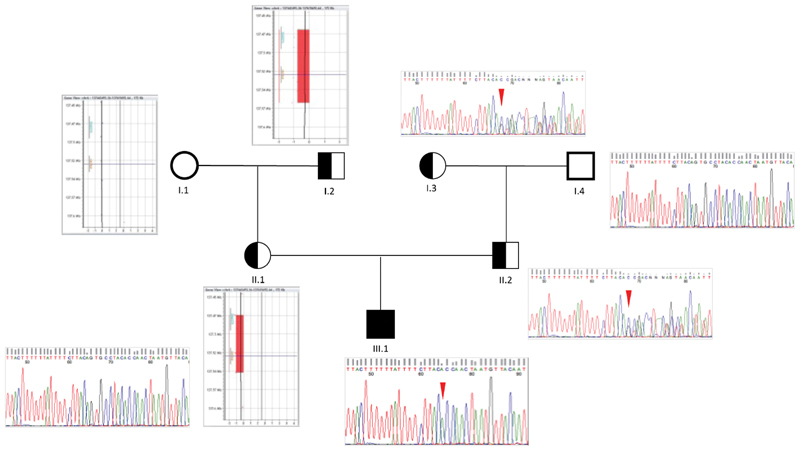

We detected a INFGR1 homozygous 9-bp deletion (NM_000416.2:c.86–1_93del) involving the splice acceptor site at the 5′ end of exon 2. This variant is reported in dbSNP (rs753213766) and gnomAD with a frequency in the non-Finnish European population of 1/111,592 (0.0008961%). However, SNP-CGH array (180K) detected a 77.6-Kb heterozygous deletion (chr6:137,474,623–137,552,245; GRCh37/hg19) entirely spanning INFGR1 and part of IL22RA2 and accounting for the c.86–1_93del loss-of-heterozygosity. A similar-sized CNV loss (chr6:137,459,528–137,573,338) is reported in DGV (Database of Genomic Variants; esv2759473), with a frequency of 1/270 (0.37%). Segregation analysis in the family revealed that the splice-site variant was inherited from the father and was also present in the paternal grandmother, whereas the microdeletion was detected in both the mother's and maternal grandfather's DNAs ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Segregation analysis of the identified variations (copy number variation and single-nucleotide variant) in the family. Electropherograms show the apparent homozygous IFNGR1 c.86–1_94del in the proband (III.1; red arrowhead ) due to the presence of a IFNGR1 deletion on the maternal allele (II.1), as revealed by array-CGH (comparative genomic hybridization): arr[hg19]6q23.3 (137,446,059 × 2, 137,474,623–137,552,245 × 1, 137,598,684 × 2), which converts a heterozygous variant to the homozygous state. Pedigree segregation showed that the IFNGR1 c.86–1_94del was paternally inherited (II.2; red arrowhead ), being also detectable in the paternal grandmother (I.3), whereas the whole IFNGR1 deletion was detected in the maternal grandfather's DNA (I.2).

Functional Validation

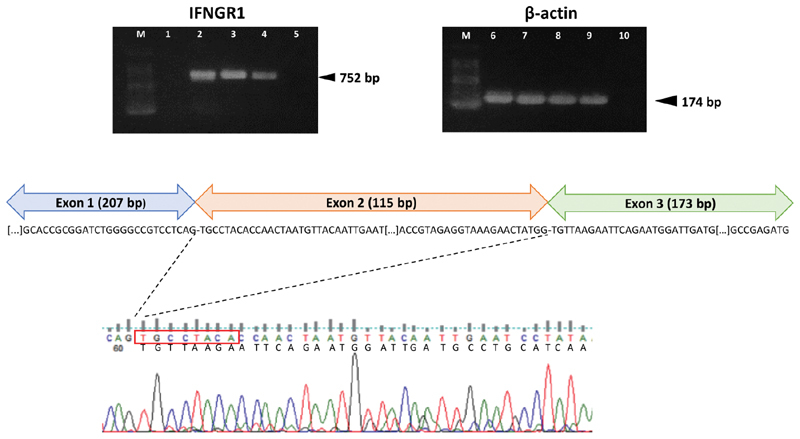

Analysis of messenger RNA (mRNA) derived from paternal peripheral blood demonstrated that the splice-site variant causes skipping of INFGR1 exon 2 ( Fig. 5 ). Reverse transcription PCR showed undetectable INFGR1 expression in the proband whole blood cells, as also confirmed by quantitative PCR. In the father's sample, the skipped variant mRNA form represents a small amount of total INFGR1 transcript. Therefore, it might be speculated that the combination of a deletion on the maternal allele and the splice-site variant on the paternal allele may synergistically result in an absent (or undetectable) INFGR1 expression. Accordingly, the skipped aberrant transcript, which is likely targeted by nonsense-mediated mRNA decay, only represents a small fraction of the entire INFGR1 mRNA in paternal blood. Compared with the full-length wild-type form (489 aa), the mutant mRNA is predicted to generate a shorter protein of 348 aa lacking the N-terminus containing the Ig-like fibronectin type III domain (pfam0004; aa 2–113), which is involved in IFN-γ binding.

Fig. 5.

Complementary DNA (cDNA) analysis on whole peripheral blood of the patient and parents. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) shows complete absence of IFNGR1 cDNA product (length: 752 bp) in the proband's blood (upper left panel). ACTB (β-actin; 174 bp) was used as the housekeeping gene ( upper right panel ). M: 100-bp allelic ladder; 1, 6: proband; 2, 7: father; 3, 8: mother; 4,9: positive control (blood pool of eight healthy individuals); 5, 10: RT-negative control. Sequencing of the amplicons revealed skipping of IFNGR1 exon 2 in the paternal blood sample ( bottom panel ). Importantly, the level of residual mutant transcript represents a small fraction of the entire INFGR1 messenger RNA (∼20%).

Discussion

We describe an 18-month-old child presenting with a clinical picture of suspected hemoproliferative disorder, in whom evidence of MAI, detected in cultures of liver and mesenteric lymph nodes, suggested the diagnosis of a form of MSMD despite the absence of family history or parental consanguinity. Functional assays (high plasma level of IFN-γ and completely abolished induction of IL-12) supported this diagnosis, subsequently confirmed by molecular analysis. Moreover, lack of disease manifestations and normal IFN-γ levels in parents, both carriers of monoallelic mutations, further confirmed loss of function (and the need for a double allelic hit) rather than dominant-negative as the leading pathogenic mechanism in our trio. According to the Leiden Open Variation Database ( https://databases.lovd.nl/shared/genes/IFNGR1 ) and Human Gene Mutation Database, most of the variants causing complete IFN-γR1 deficiency identified so far are single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small duplications, insertions, or deletions (the largest deletion being 22 nucleotides long) spread along the entire gene length; a single large genomic deletion, entirely removing IFNGR1 and causing complete IFN-γR1 deficiency, was reported in three related MSMD patients of Turkish origin. 26 As far as we know, this is the first case of compound heterozygosity due to an SNV plus a CNV. In a previous study of 2,000 consecutive primarily pediatric patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing, this mutational combination was reported in only 4 (2%) of 181 patients affected by an autosomal recessive disease compared with 104 (57%) of 181 cases with double SNVs. 27 The deletion removed the last five exons of IL22RA2 (*606648-Interleukin 22 Receptor Alpha-2: cytogenetic location. 6q23.3 OMIM: 606648), a gene encoding the α-2 subunit of IL-22 receptor. A previous report identified a homozygous deletion encompassing the entire IFNGR1 gene and terminating 117-bp upstream of the transcription start of IL22RA2 ; in that case, the authors proved that IL22RA2 transcription was not affected. 26 In animal model (homozygous knockout mice), large heterozygous deletion spanning IL22RA2 has been shown to cause colitis instead of immunological deficiency. This finding is in agreement with the fact that IL22RA2 is expressed in intestinal and lymphoid tissues and that IL-22 tightly influences susceptibility to Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in humans. 28 29 30 Although the combination of a CNV plus an SNV accounts for a minority of autosomal recessive diseases, it could be speculated that this condition is currently underestimated due to limitations of CNV detection by whole-exome sequencing caused both by the lack of efficient pipelines able to identify such anomalies and by the possible presence of noncoding CNVs altering the expression of the disease-associated gene, consequence of both position effect and TADs (topologically associated domains) disruption mechanisms. In our case, we describe the identification of a monoallelic variant in IFNGR1 , a gene whose mutations perfectly match the patient's clinical condition; thus, we hypothesize that a genomic alteration from a balanced translocation to a CNV had altered the expression of the second allele.

Conclusion

In our experience, when dealing with a child with a clinical picture that strongly suggests a lymphoproliferative disease not confirmed by immunohistochemical tests, it is important to consider the possibility of a form of primitive immunodeficiency (PID). MSMD is a small subgroup of PID affecting the IFN-γ signaling pathway, which plays a key role in innate immune defense against intracellular pathogens. In case of a child with a lymphoproliferative clinical presentation in whom a form of PID is suspected, it is advisable to subject the histological samples for microbiological test and culture for intracellular pathogens, especially mycobacteria. MSMDs are very rare forms of PID, usually with autosomal recessive inheritance, and as such are reported more frequently among children born to consanguineous parents, but, as our experience clearly shows, in case of very suggestive clinical features, this group of diseases must be taken into consideration even in the absence of family history or parental consanguinity.

Diagnostic confirmation of MSMD requires functional assays (high plasma level of IFN-γ and completely abolished induction of IL-12). Molecular analysis is crucial to better characterize the specific genotype variants and must be extended to parents and siblings. Our patient was affected by a complete IFN-γR1 deficiency and the sequencing of the IFNGR1 gene of the child showed a rare compound heterozygosity for a subpolymorphic CNV and a novel rare splice-site variant resulting in complete IFN-γR1 deficiency. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of compound heterozygosity due to an SNV plus a CNV.

Although a rapid diagnosis is essential before promptly starting an adequate and prolonged antimycobaterial therapy, HSCT still remains the only current curative option. An optimal control of mycobacterial infection before HSCT and the pretransplant normalization of plasma IFN-γ circulating levels, as well as the type of myeloablative conditioning, proved to be the most important factors for a successful of the HSCT and long-term survival of the patients. The significant decrease in circulating IFN-γ concentration, undetectable before HSCT, was one of the crucial factors for the success of HSCT in our patient. As reported in the literature, pretransplant normalization of IFN-γ is a fundamental prerequisite for the graft because IFN-γ is known to inhibit stem cell proliferation and hematopoiesis. For this reason, it is hoped that the monoclonal antibody to IFN-γ, emapalumab, currently only approved for the treatment of primary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, 31 could be soon available also for patients with complete IFN-γR1 deficiency who are candidates for HSCT.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. Maurizio Aricò, Meyer Pediatric Hospital, Firenze, Italy, for his valuable inputs; Dr. Chiara Azzari, Professor, Pediatric Immunology, University of Firenze, Firenze, Italy; and Dr. Elena Sieni, Pediatric Oncoematology, Meyer Pediatric Hospital, Firenze, Italy, for performing molecular analysis of the PRF1 gene. We also extend special thanks to Dr. Michaela Allen and Miss Sofia Barana for the linguistic revision.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.Bustamante J, Boisson-Dupuis S, Abel L, Casanova J L. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: genetic, immunological, and clinical features of inborn errors of IFN-γ immunity. Semin Immunol. 2014;26(06):454–470. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Filipe-Santos O, Bustamante J, Chapgier A et al. Inborn errors of IL-12/23- and IFN-gamma-mediated immunity: molecular, cellular, and clinical features. Semin Immunol. 2006;18(06):347–361. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vankayalapati R, Wizel B, Samten B et al. Cytokine profiles in immunocompetent persons infected with Mycobacterium avium complex . J Infect Dis. 2001;183(03):478–484. doi: 10.1086/318087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jouanguy E, Altare F, Lamhamedi S et al. Interferon-γ-receptor deficiency in an infant with fatal bacille Calmette-Guérin infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(26):1956–1961. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newport M J, Huxley C M, Huston S et al. A mutation in the interferon-gamma-receptor gene and susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(26):1941–1949. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612263352602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosain J, Kong X F, Martinez-Barricarte R et al. Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease: 2014-2018 update. Immunol Cell Biol. 2019;97(04):360–367. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The NCBI Gene Database; National Library of Medicine (US).IFNGR1 Interferon Gamma Receptor 1, Gene ID: 3459Available at:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3459. Accessed October 14, 2016

- 8.van de Vosse E, van Dissel J T. IFN-γR1 defects: Mutation update and description of the IFNGR1 variation database. Hum Mutat. 2017;38(10):1286–1296. doi: 10.1002/humu.23302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shabani M, Aleyasin S, Kashef S et al. A novel recessive mutation of interferon gamma receptor 1 in a patient with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in bone marrow aspirate . J Clin Immunol. 2019;39(02):127–130. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00595-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorman S E, Picard C, Lammas Det al. Clinical features of dominant and recessive interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiencies Lancet 2004364(9451):2113–2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olbrich P, Martínez-Saavedra M T, Perez-Hurtado J M et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in a child with complete interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(11):2036–2039. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu U I, Holland S M. Host susceptibility to non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(08):968–980. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenzweig S D, Holland S M. Defects in the interferon-gamma and interleukin-12 pathways. Immunol Rev. 2005;203:38–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fieschi C, Dupuis S, Picard C, Smith C I, Holland S M, Casanova J L. High levels of interferon gamma in the plasma of children with complete interferon gamma receptor deficiency. Pediatrics. 2001;107(04):E48. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bax H I, Freeman A F, Anderson V L et al. B-cell lymphoma in a patient with complete interferon gamma receptor 1 deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2013;33(06):1062–1066. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9907-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Camcioglu Y, Picard C, Lacoste V et al. HHV-8-associated Kaposi sarcoma in a child with IFNgammaR1 deficiency. J Pediatr. 2004;144(04):519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taramasso L, Boisson-Dupuis S, Garrè M L et al. Pineal germinoma in a child with interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency. case report and literature review. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34(08):922–927. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hetzel M, Mucci A, Blank P et al. Hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy for IFNγR1 deficiency protects mice from mycobacterial infections. Blood. 2018;131(05):533–545. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-812859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rottman M, Soudais C, Vogt G et al. IFN-gamma mediates the rejection of haematopoietic stem cells in IFN-gammaR1-deficient hosts. PLoS Med. 2008;5(01):e26. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delisle J S, Gaboury L, Bélanger M P, Tassé E, Yagita H, Perreault C. Graft-versus-host disease causes failure of donor hematopoiesis and lymphopoiesis in interferon-gamma receptor-deficient hosts. Blood. 2008;112(05):2111–2119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Bruin A M, Voermans C, Nolte M A. Impact of interferon-γ on hematopoiesis. Blood. 2014;124(16):2479–2486. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-568451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reuter U, Roesler J, Thiede C et al. Correction of complete interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency by bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002;100(12):4234–4235. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roesler J, Horwitz M E, Picard C et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for complete IFN-gamma receptor 1 deficiency: a multi-institutional survey. J Pediatr. 2004;145(06):806–812. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chantrain C F, Bruwier A, Brichard B et al. Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a child with active disseminated Mycobacterium fortuitum infection and interferon-γ receptor 1 deficiency . Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(01):75–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moilanen P, Korppi M, Hovi L et al. Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation from an unrelated donor in a child with interferon gamma receptor deficiency. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(07):658–660. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318195092e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Vor I C, van der Meulen P M, Bekker V et al. Deletion of the entire interferon-γ receptor 1 gene causing complete deficiency in three related patients. J Clin Immunol. 2016;36(03):195–203. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0244-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y, Muzny D M, Xia F et al. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. JAMA. 2014;312(18):1870–1879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jinnohara T, Kanaya T, Hase K et al. IL-22BP dictates characteristics of Peyer's patch follicle-associated epithelium for antigen uptake. J Exp Med. 2017;214(06):1607–1618. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andoh A, Zhang Z, Inatomi O et al. Interleukin-22, a member of the IL-10 subfamily, induces inflammatory responses in colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(03):969–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin J C, Bériou G, Heslan M et al. IL-22BP is produced by eosinophils in human gut and blocks IL-22 protective actions during colitis. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9(02):539–549. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bracaglia C, Prencipe G, Insalaco Aet al. Emapalumab, an anti-interferon gamma monoclonal antibody in two patients with NLRC4-related disease and severe Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) [abstract]Arthritis Rheumatol201870(10). Available at:https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/emapalumab-an-anti-interferon-gamma-monoclonal-antibody-in-two-patients-with-nlrc4-related-disease-and-severe-hemophagocytic-lymphohistiocytosis-hlh/. Accessed October 31, 2019