Abstract

Objectives:

Geriatric depression often presents with memory and cognitive complaints that are associated with increased risk for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). In a parent clinical trial of escitalopram combined with memantine or placebo for geriatric depression and subjective memory complaints, we found that memantine improved executive function and delayed recall performance at 12 months ( NCT01902004). In this report, we used positron emission tomography (PET) to assess the relationship between in-vivo amyloid and tau brain biomarkers to clinical and cognitive treatment response.

Design:

In a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, we measured 2-(1-{6-[(2-[F18]fluoroethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-naphthyl}ethylidene) malononitrile ([18F]FDDNP) binding at baseline, and assessed mood and cognitive performance at baseline, post-treatment (6 months) and naturalistic follow-up (12 months).

Participants:

Twenty-two older adults with major depressive disorder and subjective memory complaints completed PET scans and were included in this report.

Results:

Across both treatment groups, higher frontal lobe [18F]FDDNP binding at baseline was associated with improvement in executive function at 6 months (corrected p=.045). This effect was no longer significant at 12 months (corrected p=.12). There was no association of regional [18F]FDDNP binding with change in mood symptoms (corrected p=.2).

Conclusions:

[18F]FDDNP binding may predict cognitive response to antidepressant treatment. Larger trials are required to further test the value of [18F]FDDNP binding as a biomarker of potential for cognitive improvement with antidepressant treatment in geriatric depression.

Keywords: Geriatric Depression, Alzheimer’s Disease, [18F]FDDNP Positron Emission Tomography, Executive Function, Neuroimaging, Cognitive Impairment, amyloid and tau, memantine, escitaltopram, clinical trial

Introduction

Late-life depression (LLD) affects about 5 to 10% of individuals over the age of 60 years and is associated with reduced remission rates compared to depression in younger adults (Ismail et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2005). Depression in older adults often presents with cognitive symptoms including executive dysfunction and memory impairment (Wilkins et al., 2009; Singh-Manoux et al., 2017) that are associated with poor treatment response (Carpenter et al., 2014; Tunvirachaisakul et al., 2017). Both objective cognitive impairment and subjective memory complaints increase the risk of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias (Singh-Manoux et al., 2017; Diniz et al., 2013; Vega et al., 2016). As such, the development of effective treatments targeting both mood and cognition in LLD with comorbid subjective memory complaints is urgently needed.

We conducted a 6-month randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial to investigate the efficacy and tolerability of escitalopram combined with memantine (a cognitive enhancer) or placebo in 95 adults with geriatric depression (Lavretsky et al., 2019). Both treatment groups improved significantly in depressive symptoms severity. The combination of escitalopram and memantine resulted in significantly greater improvement in executive function and delayed recall at 12 months compared to the escitalopram and placebo group. Given the 12-month latency period prior to detection of cognitive improvement, improving prediction of which patients are likely to respond to memantine treatment has the potential to provide personalized treatment options.

Brain amyloid and tau deposits are associated with AD pathology, and positron emission tomography (PET) markers of amyloid and tau can be detected years before a diagnosis of cognitive impairment (Rosen et al., 2013; Sperling et al., 2011). Brain amyloid imaging demonstrates slow and steady increases amyloid binding, especially in medial temporal, parietal and frontal lobes, during the prodromal phase of AD (Cho et al., 2016a; Palmqvist et al., 2017) and plateaus once dementia is diagnosed (Villemagne et al., 2013).

Several ligands have been developed for use with positron emission tomography (PET) as biomarkers that measure brain amyloid and tau deposits. In contrast to the [11C]Pittsburgh Compound-B (PIB) and [18F]Florbetaben that are primarily reported to bind to amyloid but not tau (Klunk et al., 2004; Shin et al., 2008), or [18F]MK-6240, a more recent tracer, which appears to mainly bind to tau (Hostetler et al., 2016), 2-(1-{6-[(2-[fluorine18]fluoroethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-naphthyl}-ethylidene)malononitrile ([18F]FDDNP) has a high binding affinity to both amyloid and tau (Murugan et al., 2018). Binding of [18F]FDDNP in the medial temporal lobe has been associated with subjective memory complaints and objective measures of memory decline prior to the diagnosis of MCI or dementia (Merrill et al., 2012; Small et al., 2012). [18F]FDDNP binding is increased and more widespread in later stages of dementia (Palmqvist et al., 2017; Bejanin et al., 2017). Limited data are available on [18F]FDDNP binding in LLD, and no studies to date have investigated the relationship between [18F]FDDNP binding and antidepressant treatment response (Eyre et al., 2017; Lavretsky et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2011).

In the current pilot study, we investigated whether baseline [18F]FDDNP binding can serve as a biomarker of clinical and cognitive response to escitalopram and memantine or placebo in older depressed adults. Specifically, we tested whether [18F]FDDNP binding in the medial temporal, parietal and frontal lobes at baseline is associated with changes in mood, delayed recall performance, and executive functioning at post-treatment (i.e., 6 months) and naturalistic follow-up (12 months).

Methods

Participants

Twenty-two participants with LLD (>60 years, mean age=72.32, SD=6.92; 14 male/8 female) who participated in the 6-month RCT ( NCT01902004) underwent PET imaging at baseline at the University of California Los Angeles Ahmanson & Lovelace Brain Mapping Center (Table 1). Of the 22 participants, 11 received escitalopram and memantine, and the remaining 11 received escitalopram and placebo. Eligibility criteria included: 1) age 60 or older, 2) diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD; DSM-5, American Psychiatric Association, 2013), 3) 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1967) score of 16 or higher, 4) absence of dementia as indicated by a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE; Folstein et al., 1975) score of 23 or higher; and 4) endorsement of subjective memory complaints (affirmative response to the question, “Have you experienced memory problems over the past 6 months?” during phone screening). Exclusion criteria were: 1) lifetime history of any psychiatric disorder except MDD, co-morbid anxiety, or insomnia; 2) recent or current unstable medical or neurological disorders; 3) diagnosis of moderate or severe neurocognitive impairment; or 4) known allergic reaction to escitalopram or memantine. Contra-indications to MRI or CT scanning accompanying the PET scan further excluded potential participants, as well as refusal of the PET scan. All participants were free from cognitive enhancers at baseline. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of California Los Angeles. Participants signed written informed consent prior to in-person evaluation.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic, clinical test scores, and regional [18F]FDDNP binding.

| Variable | Escitalopram + Memantine (n=11) | Escitalopram + placebo (n=11) | Statistic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (range) | Median (range) | Kruskal-Wallis Test | |

| Age (years) | 65 (63-83) | 75 (63-82) | χ2 (1) = 1.57, p = .2 |

| Education | 14 (12-18) | 16 (13-25) | χ2 (1) = 1.02, p = .3 |

| Age of onset | 55 (13-77) | 63.5 (8-80) | χ2 (1) = 1.12, p = .3 |

| Number of episodes | 2 (1-12) | 6 (1-25) | χ2 (1) = 1.38, p = .2 |

| MMSE | 28 (25-30) | 28 (23-30) | χ2 (1) = 0.88, p = .4 |

| HAM-D | 18 (16-21) | 16 (16-19) | χ2 (1) = 2.88, p = .09 |

| Z-scores | |||

| Delayed recall | 0.19 (−0.78-1.42) | -0.13 (−1.47-.99) | χ2 (1) = 0.57, p = .5 |

| Executive function | 0.21 (−1.39-0.71) | -0.02 (−1.29-0.79) | χ2 (1) = 0.01, p = .9 |

| [18F]FDDNP DVRs | |||

| Frontal | 1.15 (1.06-1.22) | 1.15 (1.06-1.26) | χ2 (1) = 0.002, p = 1.0 |

| Parietal | 1.08 (1.03-1.16) | 1.09 (1.0-1.15) | χ2 (1) = 0.001, p = 1.0 |

| MTL | 1.22 (1.02-1.35) | 1.22 (1.03-1.42) | χ2 (1) = 0.67, p = .4 |

| Treatment groups | |||

| N (%) | N (%) | Fisher’s exact | |

| Male | 8 (73) | 6 (55) | p = .7 |

| Female | 3 (27) | 5 (45) | |

| MCI | 1 (9) | 1 (9) | p = 1.0 |

Diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI)

MCI was diagnosed according to the following criteria: 1) a Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) score of 0.5 (Hughes et al., 1982), indicating the stage between normal cognition and dementia; 2) subjective cognitive decline reported by the participant; 3) lack of significant functional impairment, and 4) objective impairment on neurocognitive tests. Objective impairment on neurocognitive testing was defined as scoring one standard deviation (SD) below age- and education-specific norms on at least two screening memory tests (Hopkins Verbal Learning Test, Revised, [either Total or Delayed scores] and Wechsler Memory Scale Third Edition, WMS-III, verbal paired associates, [either Total or Delayed scores]). Participants who met these criteria were classified as amnestic MCI (either single or multiple domains; Winblad et al., 2004).

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was change on the 24-item Hamilton Depression Rating scale. Composite cognitive scores representing delayed recall and executive function performance served as secondary measures. These scores were computed from the means of domain-specific tests derived from a complete neuropsychological test battery administered at baseline, post-treatment (6 months) and at follow-up (12 months) (Lezac et al., 2004). Our measure of delayed recall consisted of the means of the California Verbal learning Test (CVLT; Delis, 2000) for long delayed free recall, the delayed recall score of the Verbal Paired Associates test (VPA; Wechsler, 1997), and the 30-minute delayed recall of the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (Meyers and Meyers, 1995). The executive function score was composed of the Trail-making Test part B (time to completion; (Reitan et al., 1988)), the Stroop interference score (time to completion; Golden et al., 1975) and the raw score of the F.A.S. for verbal fluency (Benton et al., 1983). Raw scores were transformed to z-scores for each individual test score of interest, and subsequently averaged. For variables in which better performance was represented by lower values (e.g., Trail Making Test), z-scores were reversed so that higher z-scores represented better performance for all measures.

Treatment Protocol

Participants received a daily dose of 10 mg of escitalopram for the first month along with co-administered memantine or placebo. Within the first four weeks, memantine and a matched placebo dose were increased over time, starting with 5 mg a day and titrated up to 20 mg a day. The Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI; Guy, 2000) was administered at baseline and follow-up visits to assess overall severity and improvement of depression. In cases where improvement was “minimal” or less (i.e., CGI score ≧3) at 4 weeks, the escitalopram dose was increased to 20 mg. The dose of the study drugs was lowered as needed depending on tolerability (minimum doses were 5 mg daily for memantine and 10 mg daily for escitalopram). Both participants and study staff (including the prescribing study physician) were blinded to treatment for at least 6 months (for additional details, Lavretsky et al., 2019).

Neuroimaging Protocol

A PET scan was performed for each patient at baseline. At the University of California Los Angeles Ahmanson & Lovelace Brain Mapping Center (UCLA ALBMC), participants concomitantly underwent either an anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or a computer tomography (CT) scan to map [18F]FDDNP to individual neuroanatomy. A bolus of [18F]FDDNP (320-550 MBq) was injected via indwelling intravenous catheters and subsequent 1-hour scans were performed using a Siemens-CTI system (Siemens CTI, Knoxville, TN). [18F]FDDNP was prepared as described previously (Liu et al., 2007). Decay correction and reconstruction were performed using filtered back-projection (Hann filter, 5.5mm full-width half maximum). Final images involved 63 contiguous sections with a 2.42mm (EXACT HR+) intra-plane distance. Logan graphical analysis for determination of brain local distribution volume ratios (DVR) was applied with the cerebellum as a reference region. High-resolution T1-weighted images were performed using either a 3T Siemens Tim Trio or Prisma system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) and a 32-channel head coil. The parameters, which were matched across scanners, were the following: a multi-echo MPRAGE scan 1mm3 with isotropic voxel dimensions, 176 slices, TR=2,150 ms, TE=1.74, 3.6, 5.46 and 7.32 ms, TI=1,260, FOV=256mm, matrix size= 256x256mm, and a flip angle=7 degrees. Coregistration with either MRI or CT was used to reconstruct regions of interest (ROIs). Based on the existing literature on the distribution and progression of amyloid and tau (Palmqvist et al., 2017; Cho et al., 2016b), we selected the frontal, parietal, and medial temporal lobes as ROIs (for detailed methods, see Small et al., 2006).

Statistical Analysis

Due to the small sample size, non-parametric methods were used for all analyses. As recommended by Conover et al. (Conover and Iman, 1981; Conover, 2012), we used a rank transformation on all of the variables and then estimated standard general linear models. Changes in depressive symptoms (HAM-D) and cognitive performance (delayed recall and executive function) were examined using rank-based general linear models, with treatment group (escitalopram plus memantine vs. escitalopram plus placebo) as the predictor, controlling for baseline scores, as well as age and sex. To examine the association of baseline [18F]FDDNP binding with changes in these outcome measures, similar general linear models were estimated, with regional [18F]FDDNP binding levels, treatment group, and the interaction of treatment group with [18F]FDDNP binding as predictors. Since each ROI (frontal, parietal and MTL) was examined with respect to three outcome measures (namely HAM-D, delayed recall and executive function), we set the level of significance at p < .05/3 i.e. .0167. Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r’s) are provided for all significant findings.

Results

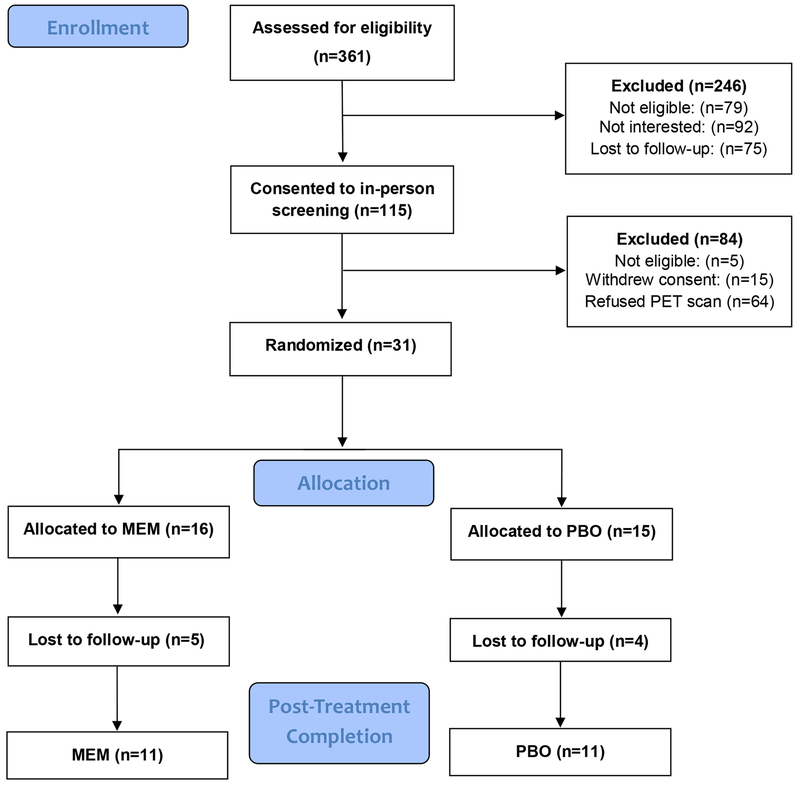

Of the 31 participants who completed baseline PET scans, 22 participants completed the 6-month follow-up and 13 completed the 12-month follow-up (please see CONSORT diagram, Figure 1). There were no differences in demographic and clinical variables at baseline between groups (Table 1). One participant in each group met criteria for MCI. The groups did not differ in the median dose of escitalopram (10 mg; range 10-20 mg). The memantine group received a median daily dose of memantine of 20 mg (range 5-20 mg). The groups did not differ in remission rates, defined as a HAM-D score of 6 or lower at follow-up (Fisher’s exact p=1.0). Sixteen of 22 patients achieved remission at 6 months, 8 in each treatment group, and 5 per group sustained remission at 12 months. HAM-D scores improved significantly within each group from baseline to 6 months (memantine: Signed rank statistic S=−33, p=.001; placebo: S=−33, p=.001), as well as from baseline to 12 months (memantine: S=−21, p=.01; placebo: S=−10.5, p=.03). Cognitive measures did not improve significantly within groups over time (S range = −12 - 7, p>.25; changes in scores from baseline are presented in Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram.

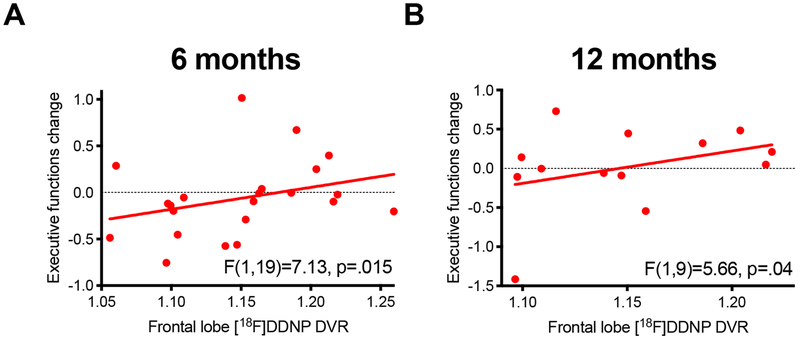

There was no between-group difference in regional [18F]FDDNP binding at baseline. Baseline [18F]FDDNP binding was not associated with change in HAM-D or change in delayed recall. However, greater frontal [18F]FDDNP binding was associated with greater improvement in executive function across groups at 6 months (F(1,19)=7.13, p=.015, corrected p=.045, r=.53) (Figure 2A). This association was not significant at 12 months after correction for multiple comparisons (F(1,9)=5.66, p=.04, corrected p=.12, r=.59; Figure 2B). The association of frontal [18F]FDDNP binding with change in executive function at 6 months continued to be significant, controlling for change in HAM-D in the model (F(1,18)=7.70, p=.01). No other interaction or main effects were significant.

Figure 2. Higher [18F]FDDNP binding predicts improvement in executive function.

A) Frontal lobe [18F]FDDNP DVR binding was associated with improvement in executive function at 6 months across treatment groups (corrected p=.045). B) At 12 months, this effect was no longer statistically significant after correction for multiple comparisons (corrected p=.12).

Discussion

Our study is the first to examine the role of in-vivo amyloid/tau PET binding as a biomarker of heterogeneity of antidepressant response in LLD. In this pilot study, we examined the relationship between baseline [18F]FDDNP binding and change in mood and cognition in older adults with major depression in a 6 month double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT comparing escitalopram and memantine to escitalopram and placebo with 12 month follow-up. We found that higher frontal lobe [18F]FDDNP binding at baseline was associated with greater improvement in executive function across groups at 6-month follow-up; this association was no longer significant at 12-months after correcting for multiple comparisons, possibly due to additional dropout.

In the parent RCT, we demonstrated that combined escitalopram and memantine therapy resulted in improved cognitive function at 12 months compared to escitalopram and placebo (Lavretsky et al., 2019). In this report of a smaller subsample with baseline PET imaging, we did not find group differences in cognitive or mood outcomes, which may be a consequence of reduced statistical power. However, we observed an association between increased baseline frontal lobe [18F]FDDNP binding and subsequent improvement in executive function, which may indicate improved cognitive resilience with antidepressant treatment, especially in those with greater accumulation of amyloid and tau markers at baseline. This observed association may be attributable to improvement in depressive symptoms. However, controlling for change in HAM-D score did not change the results, suggesting that the association between higher baseline binding and subsequent cognitive improvement is independent of improvement in depressive symptoms. Our findings are also consistent with studies of younger adults with MDD in which antidepressant treatment has been associated with improvement in executive function (Wagner et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2016).

Previous studies suggested that [18F]FDDNP binding may serve as a biomarker of cognitive decline (Jack et al., 2013; Cole et al., 2018; Merrill et al., 2012; Small et al., 2012). The use of [18F]FDDNP in predicting clinical and cognitive outcomes in LLD is also supported by our prior studies demonstrating regionally increased [18F]FDDNP in LLD compared to healthy controls, relationships between regional [18F]FDDNP binding affinity and symptoms of depression, anxiety and subjective memory problems, as well as a relationship between increased [18F]FDDNP binding over a two-year period with memory decline across healthy older adults and those with MCI (Kumar et al., 2011; Lavretsky et al., 2009; Small et al., 2012). In our prior study, depression correlated with medial temporal lobe [18F]FDDNP binding in cognitively healthy older adults but not those with MCI (Lavretsky et al., 2009). Frontal, parietal and medial temporal [18F]FDDNP binding at baseline has also been associated with decline in executive functions two years later in older adults with MCI or AD (Small et al., 2012). The same study found no associations between frontal, parietal or medial temporal lobe [18F]FDDNP binding with changes in memory. Similar to these results, we did not find any associations between parietal and medial temporal [18F]FDDNP binding and executive functions or memory in our LLD sample. However, our results demonstrated that baseline [18F]FDDNP binding in frontal lobes at baseline was associated with improvement in executive functions over time. Because we are first to report this relationship of greater neuropathology in the frontal lobe at baseline to greater cognitive improvement, this finding will require replication. Nevertheless, our findings are suggestive that [18F]FDDNP binding may be useful for identifying those who are at greater risk for AD or related dementias and those who might derive a cognitive benefit from antidepressant treatment.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the small sample size restricted our ability to detect group differences in clinical and cognitive outcomes. Second, our sample was a fairly homogeneous group of mostly Caucasian and college-educated adults with a relatively preserved cognition (only one participant per group met the criteria for MCI). Additional dropout of 9 subjects from 6 to 12 months reduced the power to detect significant effects at 12 months, though the magnitude of the observed association was similar at 6 and 12 months. Although our approach was hypothesis-driven basing a-priori hypotheses on previous findings of associations between the [18F]FDDNP binding in three specific ROIs with clinical and cognitive scores, our correction for multiple comparisons was lenient given the number of tests we performed. This may lead to an inflation of Type I error and should be interpreted with caution. Lastly, the ideal design of the study examining the role of in-vivo PET markers of amyloid and tau- should also include blood and CSF markers to fully the role of amyloid and tau in predicting antidepressant and cognitive response in LLD.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that [18F]FDDNP can serve as a biomarker to identify those candidates who are likely to experience improvement in executive functioning with antidepressant treatment. Larger trials are needed to further test the value of [18F]FDDNP binding as a biomarker of heterogeneity of treatment response in geriatric depression. Future longitudinal studies can provide more insight into the utility of [18F]FDDNP binding as a biomarker of cognitive decline in older adults with major depression by including the measures of the plasma and CSF biomarkers of tau and amyloid, and ideally, followed by post-mortem neuropathological confirmation studies. Continued investigation of biomarkers of brain aging will be useful for identifying those most likely to benefit from treatments targeting both depression and cognition. Research in this area is essential to advancing the field of personalized medicine and increasing the quality of available treatments for depressed older adults at high risk of cognitive decline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Jie Liu for the synthesis of [18F]FDDNP for these studies, to Dr. KP-Wong who performed data processing and quantitative DVR analysis of the PET images and to John Williams at the UCLA Nuclear Medicine Clinic who performed the [18F]FDDNP PET scans.

Funding: NIH R01MH097892; AT009198

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Dr. Lavretsky reports grant funding from Allergan.

Drs. Small and Barrio are co-inventors of [18F]FDDNP, which UCLA has licensed to Ceremark Pharma. They are among the co-founders of and have equity interest in Ceremark Pharma. Dr. Small also reports having served as an advisor and/or lecturer for AARP, Acadia, Activis, Allergan, Avanir, Forum, Genentech, Gerontological Society of America, Herbalife, Janssen, Lilly, Lundbeck, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, and RB Health and received grant funding from The Wonderful Co.

REFERENCES

- Bejanin A, et al. 2017. Tau pathology and neurodegeneration contribute to cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain : a journal of neurology, 140, 3286–3300. doi: 10.1093/brain/awx243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benton A, Hamsher K, Varney RN & Spreen O 1983. Contribution to neuropsychological assessment: a clinical manual, New York, NY, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CR, et al. 2014. Predicting geriatric falls following an episode of emergency department care: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med, 21, 1069–82. doi: 10.1111/acem.12488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, et al. 2016a. In vivo cortical spreading pattern of tau and amyloid in the Alzheimer disease spectrum. Ann Neurol, 80, 247–58. doi: 10.1002/ana.24711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho H, et al. 2016b. Tau PET in Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Neurology, 87, 375. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole GB, et al. 2018. The Value of In Vitro Binding as Predictor of In Vivo Results: A Case for [(18)F]FDDNP PET. Mol imaging Biol doi: 10.1007/s11307-018-1210-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover WJ, The rank transformation—an easy and intuitive way to connect many nonparametric methods to their parametric counterparts. WIREs Comput Stat 2012, 4, 432–438. doi: 10.1002/wics.1216 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conover WJ and Iman RL, 1981. Rank transformations as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric statistics. The American Statistician, 35(3), 24–129. Doi: 10.2307/2683975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delis DC 2000. California verbal learning test: Adult version Manual San Anotnio, TX, Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Diniz BS, Butters MA, Albert SM, Dew MA & Reynolds CF 3rd 2013. Late-life depression and risk of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based cohort studies. Br J Psychiatry, 202, 329–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.118307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre HA, et al. 2017. Neural correlates of apathy in late-life depression: a pilot [(18) F]FDDNP positron emission tomography study. Psychogeriatrics: the official journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 17, 186–193. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE & Mchugh PR 1975. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res, 12, 189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ, Marsella AJ & Golden EE 1975. Cognitive relationships of resistance to interference. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43, 432–432. doi: 10.1037/h0076772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W 2000. Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale, Modified. In: RUSH JA (ed.) Task Force for the Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures 1ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M 1967. Development of a Rating Scale for Primary Depressive Illness. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 6, 278–296. doi:doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetler ED, et al. 2016. Preclinical Characterization of 18F-MK-6240, a Promising PET Tracer for In Vivo Quantification of Human Neurofibrillary Tangles. J Nucl Med, 57, 1599–1606. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.171678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA & Martin RL 1982. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry, 140, 566–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail Z, Fischer C & Mccall WV 2013. What characterizes late-life depression? Psychiatr Clin North Am, 36, 483–96. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2013.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, et al. 2013. Update on hypothetical model of Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers. Lancet neurology, 12, 207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klunk WE, et al. 2004. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol, 55, 306–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Kepe V, Barrio JR & et al. 2011. Protein binding in patients with late-life depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68, 1143–1150. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavretsky H, et al. 2019. A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Trial of Combined Escitalopram and Memantine for Older Adults With Major Depression and Subjective Memory Complaints. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019 August 22. pii: S1064-7481(19)30474-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavretsky H, et al. 2009. Depression and anxiety symptoms are associated with cerebral FDDNP-PET binding in middle-aged and older nondemented adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry, 17, 493–502. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181953b82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezac M, Howieson D & Loring D 2004. Neuropsychological Assessment, New York, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, et al. 2007. High-yield, automated radiosynthesis of 2-(1-{6-[(2-[18F]fluoroethyl)(methyl)amino]-2-naphthyl}ethylidene)malononitrile ([18F]FDDNP) ready for animal or human administration. Mol Imaging Biol, 9, 6–16. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0061-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill DA, et al. 2012. Self-reported memory impairment and brain PET of amyloid and tau in middle-aged and older adults without dementia. Int Psychogeriatr, 24, 1076–84. doi: 10.1017/s1041610212000051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers JE & Meyers KR 1995. Rey Complex Figure Test under four different administration procedures. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 9, 63–67. doi: 10.1080/13854049508402059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ & Subramaniam H 2005. Prognosis of depression in old age compared to middle age: a systematic review of comparative studies. Am J Psychiatry, 162, 1588–601. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan NA, Nordberg A & Ågren H 2018. Different positron emission tomography tau tracers bind to multiple binding sites on the tau fibril: insight from computational modeling. ACS Chemical Neuroscience, 9, 1757–1767. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmqvist S, et al. 2017. Earliest accumulation of β-amyloid occurs within the default-mode network and concurrently affects brain connectivity. Nature Communications, 8, 1214. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01150-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM & Wolfson D 1988. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery and REHABIT: A model for integrating evaluation and remediation of cognitive impairment. Cognitive Rehabilitation, 6, 10–17. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9820-3_4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen C, Hansson O, Blennow K & Zetterberg H 2013. Fluid biomarkers in Alzheimer’s disease - current concepts. Mol Neurodegener, 8, 20. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-8-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Lee SY, Kim SH, Kim YB & Cho SJ 2008. Multitracer PET imaging of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage, 43, 236–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux A, et al. 2017. Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms Before Diagnosis of Dementia: A 28-Year Follow-up Study. JAMA Psychiatry, 74, 712–718. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GW, et al. 2006. PET of brain amyloid and tau in mild cognitive impairment. N Engl J Med, 355, 2652–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GW, Siddarth P, Kepe V & et al. 2012. Prediction of cognitive decline by positron emission tomography of brain amyloid and tau. Archives of Neurology, 69, 215–222. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperling RA, et al. 2011. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Aizheimers Dement, 7, 280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, et al. 2016. Venlafaxine treatment reduces the deficit of executive control of attention in patients with major depressive disorder. Sci Rep, 6, 28028. doi: 10.1038/srep28028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunvirachaisakul C, et al. 2017. Predictors of treatment outcome in depression in later life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord, 227, 164–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vega JN, et al. Altered brain connectivity in early postmenopausal women with subjective cognitive impairment. Front Neurosci, 10. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villemagne VL, et al. 2013. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol, 12, 357–67. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70044-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner S, et al. 2018. Plasma brain-derived neurotrophic factor (pBDNF) and executive dysfunctions in patients with major depressive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/15622975.2018.1425478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D 1997. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, III Manual, San Antonio, The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins CH, Mathews J & Sheline YI 2009. Late life depression with cognitive impairment: evaluation and treatment. Clin Interv Aging, 4, 51–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, et al. 2004. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med, 256, 240–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01380.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.