Summary

Solid tumors reside in harsh tumor microenvironments (TMEs) together with various stromal cell types. During tumor progression and metastasis, both tumor and stromal cells undergo rapid metabolic adaptations. Tumor cells metabolically coordinate or compete with their “neighbors” to maintain biosynthetic and bioenergetic demands while escaping immunosurveillance or therapeutic interventions. Here, we provide an update on metabolic communication between tumor cells and heterogeneous stromal components in primary and metastatic TMEs, and discuss emerging strategies to target metabolic communications for improved cancer treatments.

Keywords: Metabolic communication, tumor microenvironment, metabolism, stromal cells, metabolic symbiosis, nutrient competition, signaling molecule, immunomodulation, metastasis, antitumor immunity, combination therapy

Growing solid tumors consist of malignant cancer cells and heterogeneous stromal cell components. This Review from Simon and Li provides an updated overview of metabolic communication between tumor cells and stromal cells in primary and metastatic tumor microenvironments, and discusses emerging strategies to target metabolic interactions for improved cancer therapies.

Introduction

Growing primary solid tumors consist of malignant cancer cells harboring genetic alterations and heterogeneous non-malignant stromal cell components (Egeblad et al., 2010; Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Disease progression is strongly influenced by metabolic stress imposed by the local microenvironments, due to limited oxygen and nutrient supply, accumulation of metabolic waste and unfavorable pH (De Berardinis and Chandel, 2016; Gouirand et al., 2018). A majority of cancer-related deaths result from the spread of primary tumor cells to distal metastatic sites, a multi-step and highly inefficient process (Mehlen and Puisieux, 2006; Valastyan and Weinberg, 2011). To execute progression and metastasis, cancer cells undergo metabolic evolution to maximize nutrient utilization for bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands, survive harsh tumor microenvironments (TMEs) and escape immunosurveillance. This metabolic evolution, dictated by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Faubert et al., 2020), constitutes a hallmark of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Previous studies from isolated tumors and cell lines have uncovered important cancer cell-intrinsic metabolic remodeling controlled by oncogenic signaling and oncometabolites (De Berardinis and Chandel, 2016; Gouirand et al., 2018; Pavlova and Thompson, 2016) (Vander Heiden and DeBerardinis, 2017; Lehúede et al., 2016). The field has also begun to explore metabolic communications between tumor cells and TMEs (Gupta et al., 2017; Lyssiotis and Kimmelman, 2017), and to exploit these for therapeutic interventions (Li et al., 2019). In this review, we will summarize recent key findings that improve our understanding of metabolic crosstalk mechanisms in primary and metastatic TMEs.

Metabolic Crosstalk among Solid Tumor Compartments

Significant metabolic heterogeneity exists within solid tumors, which stems largely from vascular integrity and proximity to the vasculature that create oxygen and nutrient gradients. Consequently, regional tumor cells exhibit distinct metabolic profiles. For example, in human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), well-vascularized tumor subdomains utilize multiple nutrients, while less-perfused regions use glucose as their main carbon source (Hensley et al., 2016). Importantly, lactate (once considered simply metabolic waste) is preferred over glucose to fuel the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle in NSCLC (Faubert et al., 2017). In this context, lactate and glucose are utilized in parallel, as lactate can be directly channeled into the TCA cycle by mitochondrial LDH activity (Chen et al., 2016). Lactate metabolism via LDHA may also impact cytosolic redox status and redirect glucose into the pentose phosphate pathway and hexosamine biosynthesis. Alternatively, lactate as a signaling molecule potentially changes intracellular signaling pathways and/or gene expression to impact glucose uptake and catabolism.

Cancer cells within tumor compartments cooperate to form metabolic “symbiosis”. The lactate shuttle is one example, where cancer cells in hypoxic regions consume glucose through anaerobic glycolysis and release lactate, lactate is then used as a fuel for TCA cycle by cancer cells in adjacent oxygenated tumor regions (Nakajima and Van Houten, 2013; Sonveaux et al., 2008). Acute hypoxia induced by anti-angiogenic therapy drives pancreatic neuroendocrine and breast cancer cells to produce excessive lactate, which is then used by cancer cells in proximity to blood vessels (Allen et al., 2016; Pisarsky et al., 2016). Similar metabolic symbiosis has also been described in lung and colon cancers, indicating that it may represent a general crosstalk pathway. The lactate shuttle likely results from differential expression of appropriate monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs): hypoxic cancer cells express high MCT4 levels that function as major lactate exporter, whereas oxygenated cancer cells express MCT1 as lactate importer (Figure 1). It is currently unclear to what extent hypoxic tumor-derived lactate contributes to oxidative metabolism in general, as well-oxygenated cancer cells can readily metabolize glucose and other circulating nutrients including lactate. Furthermore, the precise function(s) and mechanism (s) of lactate in this regard remain to be fully understood.

Figure 1. Metabolic Heterogeneity and Symbiosis among Solid Tumor Compartments.

Vascular integrity and proximity to vasculature create oxygen and nutrient gradients leading to intratumoral metabolic heterogeneity. In hypoxic regions, cancer cells increase glucose uptake and preferentially convert it to lactate; lactate is exported through MCT4, and then imported through MCT1 by cancer cells in more oxygenated regions. In addition to glucose and lactate, oxygenated cancer cells also use alternative fuels for oxidative metabolism, and potentially provide amino acids (AAs) and lipids to hypoxic cancer cells.

In a study by Pan et al, tumor cores were found to have much lower levels of amino acids than peripheral regions, including glutamine, arginine, asparagine, serine and aspartate (Pan et al., 2016). It’s tempting to speculate that peripheral tumor cells can release these amino acids for more internal cancer cells. Hypoxic cancer cells increasingly uptake exogenous unsaturated fatty acid to maintain lipid homeostasis (Ackerman et al., 2018; Young et al., 2013), and may benefit from oxygenated cancer cells undergoing fatty acid synthesis (Figure 1). Interestingly, acetate can be generated de novo from pyruvate (Liu et al., 2018a); since acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma (Mashimo et al., 2014), it’s possible that well-perfused glioblastoma cells can synthesize acetate for hypoxic counterparts in this context. Alanine is one major carbon source for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) cells (Sousa et al., 2016), so oxygenated PDAC cells could provide alanine for hypoxic cells locally. Additionally, metabolic recycling of ammonia via glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) has been shown to support breast cancer biomass (Spinelli et al., 2017), raising the possibility of utilizing ammonia by GDH-expressing cancer cells to synthesize glutamine for neighboring cancer cells with high demand of glutamine catabolism.

Depending on cancer type and local nutrient pool, it will be interesting to identify other biomass, energy and antioxidants that can be transferred within solid tumor compartments, and define the underlying cross-feeding pathways. The metabolic heterogeneity can further be uncovered through unbiased metabolic profiling and molecular characterization of tumor subdomains. Ultimately, the corresponding functional links of intratumoral metabolic crosstalk to tumor growth warrant careful investigation.

Cancer-Fibroblast Metabolic Symbiosis

Bidirectional metabolic communications between tumor cells and stromal cells contribute to tumor growth while affecting therapeutic responses (Lyssiotis and Kimmelman, 2017). Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) constitute a major stromal component that critically modulates tumor initiation, progression and metastatic dissemination (Kalluri, 2016). Chronically activated from normal fibroblasts, CAFs exhibit increased proliferation rates, survival potential and undergo metabolic reprogramming (Chaudhri et al., 2013; Du et al., 2018; Sousa et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2015). Cancer cells and CAFs metabolically communicate through multiple mechanisms (Figure 2). A lactate shuttle, known as “reverse Warburg effect”, was described previously (Pavlides et al., 2009). Specifically, CAFs metabolize glucose through anaerobic glycolysis and export lactate, which is then taken up and utilized by oxidative cancer cells (Whitaker-Menezes et al., 2011). Indeed, intercellular contact triggers elevated glucose uptake and lactate production in prostate fibroblasts, potentially through upregulated GLUT1 and MCT4, respectively. Conversely, prostate cancer cells are reprogrammed toward aerobic metabolism, with GLUT1 downregulation and increased MCT1 expression and lactate uptake (Fiaschi et al., 2012). CAF-derived lactate may only contribute partly to cancer metabolism and growth, considering multiple lactate and other nutrient pools in vivo. Notably, the “reverse Warburg effect” does not apply to all CAF-cancer interactions, likely dictated by the cell/tissue of origin. For example, breast and colon cancer cells consume glucose and release lactate to surrounding fibroblasts (Koukourakis et al., 2006; Rattigan et al., 2012), whereas pancreatic and ovarian CAFs consume rather than release lactate (Sousa et al., 2016), which is due to low glycolytic activity (Sousa et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016).

Figure 2. Tumor-Stroma Metabolic Communications in the TME.

Heterogenous stromal cell populations metabolically cooperate with cancer cells directly or indirectly in the tumor microenvironment. Ovarian cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) provide cysteine (Cys) and reduced GSH to withstand oxidative stress. Ovarian CAFs also provide cancer cells with glutamine (Gln) and utilize cancer cell-derived glutamate (Glu) to regenerate Gln. Pancreatic CAFs provide cancer cells with alanine (Ala) through autophagy, with lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) to support phosphatidylcholine synthesis, and indirectly with collagen-derived proline (Pro) to support survival under nutrient limitation. Similarly, breast CAFs supply cancer cells with autophagy-derived dipeptides. Prostate and pancreatic CAF-derived exosomes provide nutrient cargo to cancer cells. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) shuttle mitochondria and/or mitochondrial DNA into leukemia, lung and breast cancer cells, and consume cystine to provide leukemic cells with Cys. Tumor cell-derived Lactate (Lac) stimulates CD4+ T cell differentiation into regulatory T cells (Tregs), promotes tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) polarization, but inhibits natural killer (NK) cells and effector T cells (Teffs). Similarly, tumor cell-derived kynurenine (kyu) facilitates Tregs differentiation but limits function of Teffs. Murine sarcoma-derived retinoid acid (RA) promotes intratumoral monocyte differentiation toward TAMs. TAMs promote tumor growth partly by providing metabolites such as polyamines. Adipocytes provide ovarian and breast cancer cells with fatty acids (FAs), pancreatic cancer cells with Gln, and engage in an arginine (Arg) cycling pathway using citrulline (Cit) to produce nitric oxide (NO).

In response to PDAC cells, activated pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) (a major type of pancreatic CAFs) secrete the amino acid alanine through augmented autophagy. By doing so, PSCs provide a major carbon source for PDAC cells, relieving dependency on glucose and glutamine, two essential but usually limited nutrients (Sousa et al., 2016). Collagen-derived proline promotes PDAC cell survival under nutrient limited conditions, providing another evidence of PSCs supporting PDAC metabolism and growth (Olivares et al., 2017). Interestingly, PSCs also secrete lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs) to support phosphatidylcholine synthesis and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) production by PDAC cells (Auciello et al., 2019). Under nutrient limitation, ovarian CAFs use branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and aspartate to synthesize glutamine for cancer cells; co-targeting glutamine synthetase and glutaminase in this case significantly reduces tumor growth and metastasis (Yang et al., 2016). Interestingly, ovarian CAFs induces glycogenolysis in co-cultured cancer cells, which is funneled into glycolysis, leading to increased proliferation and invasion (Curtis et al., 2019). In addition, CAFs release macromolecules to support cancer cells. As examples, lung CAFs increasingly secrete dipeptides via autophagy (Chaudhri et al., 2013), prostate and pancreatic CAFs release exosomes to deliver a spectrum of amino acids, fatty acids (FAs), and TCA cycle metabolites that are taken up and utilized by cancer cells (Richards et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2016). Moreover, even stromal cell organelles can be transferred to cancer cells to sustain the metabolism and growth. In the study by Spees et al, mitochondrial DNA was depleted in lung cancer cells leading to an inactive electron transport chain (ETC); these cells (called rho-zero cells, þ0) reacquire ETC activity through mitochondria transfer from co-cultured bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) (Spees et al., 2006).

Cancer cells are often challenged with intense redox stress, particularly when exposed to chemotherapies (Bansal and Simon, 2018). In these contexts, CAFs modulate redox homeostasis in neighboring cancer cells. Indeed, ovarian CAFs release glutathione (GSH) and cysteine to cancer cells, thereby maintaining redox balance and sustaining chemoresistance (Wang et al., 2016). Similarly, bone marrow stromal cells import cystine and convert it to cysteine, which is then released into the microenvironment and taken up for GSH synthesis by chronic lymphoid leukemia (Zhang et al., 2012). Collectively, these findings provide important metabolic connection between cancer cells and CAFs. A crosstalk between deregulated hepatocyte metabolism and hepatic stellate cells promotes liver tumorigenesis (Li et al., 2020), adding to another layer of metabolic links between CAFs and non-tumor cells in TMEs. While CAFs engage distinct feeding strategies to support corresponding tumor metabolism and growth, cancer cell-derived metabolite(s) that drive metabolic remodeling in CAFs remain to be determined in different tissue contexts.

Immunomodulation by Tumor Cell-derived Metabolites

Evasion from immune surveillance is a hallmark of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg, 2011). Tumor cells adopt several strategies to dampen immune system, including secreting metabolites to modulate the TME immune profiles (Figure 2) (Vinay et al., 2015). In hypoxic tumor regions, high concentrations of cancer cell-derived lactate impose pleotropic effects on immune cells. Lactate blocks monocyte and dendritic cell differentiation (Dietl et al., 2010; Fischer et al., 2007), blunts T cell activation and tumor immunosurveillance (Brand et al., 2016). On the other hand, lactate promotes differentiation and polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) toward an M2-like phenotype with elevated expression of Arginase-1 (ARG1) and mannose receptor C type 1 (CD206). In turn, M2-like TAMs produce immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g. IL10), and metabolites like polyamines, which are essential for cell division (Colegio et al., 2014). These findings support the hypothesis that reducing lactic acid production can enhance the efficacy of anticancer immunotherapy, which remains to be fully tested in vivo.

Increased tryptophan catabolism by cancer cells produces kynurenine, a ligand of endogenous aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) (Opitz et al., 2011). Activation of a kynurenine-AHR signaling axis in CD4+ T cells favors their differentiation into immunosuppressive regulatory T cells (Mezrich et al., 2010; Munn et al., 1999; Nguyen et al., 2010). In a similar study, tumor-repopulating cells transfer kynurenine to induce PD-1 expression in CD8+ T cells, contributing to impaired effector functions (Liu et al., 2018b).

Murine sarcoma cells produce retinoic acid (RA) to polarize intratumoral monocyte differentiation toward TAMs and away from dendritic cells, resulting in immune suppression and tumor growth (Devalaraja et al., 2020). Additionally, lipid accumulation in tumour infiltrating myeloid cells, including myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and TAMs, has been shown to promote metabolic reprogramming and skew these immune cells towards immunosuppressive phenotypes (Al-Khami et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Niu et al., 2017). These lipids may come partly from neighboring cancer cells with enhanced fatty acid synthesis.

Together, tumor cell-derived metabolites create favorable immune microenvironment for disease progression. Some of these metabolites also function as signaling molecules, as discussed below. To identify more immunomodulatory metabolites, comprehensive metabolic profiling of cancer cell secretome followed by functional tests on specific immune cell subsets would be helpful.

Metabolic Communications between Tumor Cells and Adipocytes

Obesity is closely linked to increased risk and malignance of many types of cancer (Donohoe et al., 2017; Lengyel et al., 2018). It’s now appreciated that adipocytes and adipose tissue (AT) directly mediate some protumorigenic effects of obesity (Cao, 2019) (Figure 2). For example, adipocytes serve as a source of extracellular lipids for cancer cells (Woolthuis et al., 2016). Indeed, co-cultured adipocytes undergo lipolysis and provide FAs to increase breast cancer cell proliferation (Hoy et al., 2017). Human omental adipocytes also induce co-cultured ovarian cancer cells to overexpress CD36 (also known as FA translocase), which is responsible for enhanced FA uptake, cholesterol and lipid droplet (LD) accumulation, as well as tumor growth (Ladanyi et al., 2018). In these contexts, cancer cell-derived trigger(s) of adipocyte lipolysis need to be carefully characterized. Under hypoxia, cancer cells increase extracellular lipid utilization for bioenergetic and biosynthetic demands, as well as to maintain membrane homeostasis (Ackerman et al., 2018; Young et al., 2013). Specifically, HIF-1α induces the expression of FABP (fatty acid binding protein) 3 and 7 for lipid uptake, and adipophilin, a LD structural protein (Bensaad et al., 2014); HIF-2α promotes LD coat protein PLIN2 expression for lipid storage (Qiu et al., 2016). Given the fact that CAFs can deliver fatty acids to cancer cells via exosomes (Richards et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2016), and the hypothesis that albumin-bound lipids can be taken up via micropinocytosis (Recouvreux and Commisso, 2017), it’s quite possible that these endocytosis pathways are also involved in lipid transfer from adipocytes to cancer cells.

In addition to adipocytes, ovarian adipose stromal cells have also been shown to metabolically communicate with cancer cells, through arginine metabolism. In this regard, ovarian cancer cells metabolize arginine to produce nitric oxide and citrulline through inducible nitric oxide synthetase (iNOS). The nitric oxide promotes glycolysis and cancer cell proliferation, while citrulline is released and captured by stromal adipocytes to convert back to arginine; the arginine is further excreted into extracellular spaces and utilized by cancer cells, forming a symbiotic metabolic loop (Rizi et al., 2015).

Nutrient Competition between Cancer Cells and Immune Cells

To maximize nutrient utilization, cancer cells must compete with stromal cells for limited substrates, especially under metabolic stress (De Berardinis and Chandel, 2016; Nakazawa et al., 2016; Pavlova and Thompson, 2016). We focus on emerging cancer-immune cell nutrient competition (Figure 3), due to metabolic flexibility connected to functional activity of immune cell subsets (Buck et al., 2017; Kedia-Mehta and Finlay, 2019).

Figure 3. Nutrient Competition between Cancer Cells and Immune Cells.

Increased glucose (Glu), arginine (Arg), tryptophan (Trp), serine (Ser) and methionine (Met) uptake and catabolism by cancer cells directly limits their availability to effector T cells (Teffs). Tryptophan (Trp) catabolism by cancer cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) produces immunosuppressive kynurenine (kyu) to facilitate Tregs differentiation. Glucose (Glu) catabolism by cancer cells produces lactate (Lac) to promote macrophage polarization into TAMs.

Glucose abundance has strong impacts on cellular metabolism and growth (Lyssiotis and Kimmelman, 2017; Renner et al., 2017). Glucose utilization is increased in tumor cells, resulting in low extracellular levels and metabolically restrictive environments for infiltrating immune cells. For instance, glucose consumption by melanoma cells limits glucose availability for T cells, leading to decreased abundance of glycolytic intermediate phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP). PEP modulates T cell receptor-mediated Ca2+-NFAT signaling and effector functions by repressing sarco/ER Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) activity. Consequently, defective antitumor T cell responses allow for melanoma growth (Ho et al., 2015). Similarly, glucose consumption by murine sarcoma cells metabolically restricts T cells and limits their effector functions (Chang et al., 2015). In these contexts, antitumor T cell responses can be restored by blocking glucose uptake in cancer cells and redirecting more glucose to infiltrating T cells. Indeed, increased tumor glycolysis is associated with immune resistance to adoptive T cell therapy in melanoma, whereas inhibition of glycolysis enhances T cell-mediated antitumor immunity (Cascone et al., 2018).

Increased dependency of extracellular arginine has been observed in cancer (Patil et al., 2016). Several types of cancer also lack the urea cycle enzyme argininosuccinate synthetase 1 (ASS1), rendering them unable to synthesize endogenous arginine and exclusively dependent on exogenous supply (Keshet et al., 2018; Ochocki et al., 2018). Due to high levels of iNOS and ARG1 expression, arginine can also be rapidly catabolized by MDSCs and macrophages (Mondanelli et al., 2017). In these regards, arginine availability profoundly impacts effector T cells (Fletcher et al., 2015; Lamas et al., 2012). Indeed, arginine sufficiency induces global metabolic changes and promotes the generation of central memory-like cells, whereas arginine limitation conversely dampens T cell effector functions through direct amino acid deprivation (Geiger et al., 2016). Currently, replenishing arginine and preventing arginine degradation are attractive strategies to reinvigorate T cell effector function (Li et al., 2019).

Similar to arginine, tryptophan can be depleted by tumor cells and macrophages through increased uptake and catabolism. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), the first and rate-limiting enzyme of tryptophan catabolism through the kynurenine pathway, is usually highly expressed by tumor cells and macrophages (Munn et al., 1999; Platten et al., 2012). Tryptophan catabolism further produces immunosuppressive metabolite kynurenine, promoting regulatory T cell differentiation (Mondanelli et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2010). Consequently, inhibition of tryptophan catabolism together with immune checkpoint blockade is being tested in several ongoing clinical trials (Li et al., 2019).

Serine is a non-essential amino acid that can be taken up or synthesized de novo through the serine synthesis pathway (SSP) (Locasale, 2013; Yang and Vousden, 2016). Certain cancers such as breast cancer and melanoma show gene amplification of the SSP enzymes and depend on SSP for survival even under serine-fed conditions (Mattaini et al., 2016; Pacold et al., 2016). Many other cancer cells selectively consume exogenous serine, which is converted to intracellular glycine and one-carbon units for building nucleotides and maintaining mitochondrial redox homeostasis (Yang et al., 2020; Ye et al., 2014). Importantly, extracellular serine is required for optimal T cell expansion and effector functions. This occurs in a manner where serine supplies glycine and one-carbon units for de novo nucleotide biosynthesis in proliferating T cells (Ma et al., 2017).

Methionine is an essential amino acid that participates in protein synthesis and also produces S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) for all methylation reactions. MAT2A, the enzyme involved in methionine catabolism, has been identified as an oncogene overexpressed in cancer (Ramani and Lu, 2017). Methionine is rapidly taken up by activated T cells and serves as the major substrate to maintain the SAM pools. Methionine restriction reduces histone H3K4 trimethylation and expression of key genes involved in Th17 cell proliferation and cytokine production (Roy et al., 2020). Thus, methionine consumption by cancer cells potentially affects T cell activation and differentiation.

Overall, advantageous consumption of essential nutrients by cancer cells directly limits the availability to tumor-killing immune cells, especially the cytotoxic T cells, and also produces immunosuppressive metabolites (e.g. lactate and kynurenine), collectively leading to impaired antitumor immunity (Figure 3). In addition to rapid proliferation, cancer cells outcompete by overexpressing transporters for nutrient uptake and enzymes for nutrient catabolism, which are largely controlled by oncogenic signaling pathways and/or oncometabolites (Pavlova and Thompson, 2016).

Metabolites Mediate Intercellular Crosstalk in TMEs

Metabolites were traditionally considered as metabolic intermediates or end products involved in bioenergetics and macromolecule biosynthesis, but recent years have witnessed a great expansion in delineating their actions to regulate signal transduction and gene expression, through both cell autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms (Haas et al., 2016; Liu and Wellen, 2020). Cell autonomous mechanisms include direct interactions between metabolite and protein component of signaling pathways, modulating metabolite sensor pathways, modifications of protein stability/activity, and regulation of epigenome and epitranscriptome (Haas et al., 2016; Liu and Wellen, 2020). In a non-autonomous manner, metabolites released into the TME can signal to neighboring cells to mediate intercellular crosstalk. Here we highlight some metabolites that exhibit extracellular or new intracellular actions as signaling molecules.

Lactate exhibits pleotropic effects on various cell types in the TMEs, most of which are attributed to indirect mechanisms, such as affecting local pH, modulating cellular metabolism and/or redox status (Baltazar et al., 2020; de la Cruz-López et al., 2019). Recent studies provide new insights into how lactate directly regulates signal transduction and gene expression (Figure 4). In the study by Lee et al, lactate binds to and stabilizes NDRG3 (NDRG family member 3, a PHD2/VHL substrate), and mediates hypoxia-induced activation of the Raf-ERK pathway essential for angiogenesis and cell growth (Lee et al., 2015). These findings uncover a lactate-induced mechanism for cellular adaptation to hypoxia, which is different from those controlled by HIFs (Lee et al., 2020a). Glycolysis-derived lactate inhibits retinoic-acid inducible gene I (RIG-I)-like receptor (RLR) signaling by directly binding to a mitochondrial antiviral-signaling protein (MAVS) transmembrane domain and preventing MAVS aggregation, thereby limiting type I IFN response (Zhang et al., 2019b). More recently, lactate was shown to promote a new histone posttranslational modification termed lactylation in macrophages. Specifically, glucose-derived lactate produces lactyl-CoA that contributes a lactyl group to histone protein lysine tails through acetyltransferase enzyme p300, activating wound-healing genes and resulting in an M2-like phenotype (Zhang et al., 2019a).

Figure 4. Emerging Functions of Lactate in Regulating Signal Transduction and Gene Expression.

(1) Hypoxia-induced lactate binds to NRDG3 and prevents it from pVHL-dependent degradation; stabilized NDRG3 protein binds c-Raf to mediate activation of the Raf-ERK pathway. (2) Binding to lactate interrupts MAVS mitochondrial localization, RIG-I and MAVS interaction, subsequent MAVS aggregation, and attenuates downstream TBK1-IRF3 signaling. (3) Lactate accumulation produces lactyl-coA for histone lactylation that contributes to target gene expression in macrophages.

Accumulation of nucleoside adenosine has been detected in TMEs. Adenosine is generated in tumors and regulatory T cells through ectonucleotidases (CD39 and CD73) that convert extracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to adenosine. Adenosine binds to surface adenosine 2A receptor (A2AR) on cytotoxic T cells and NK cells, inhibiting antitumor immunity (Haskó et al., 2008). Accordingly, A2AR blockade has been shown as an immunotherapy for treatment-refractory renal cell cancer (Fong et al., 2020).

As described above (Figure 2), kynurenine and RA are two metabolites derived from cancer cells and function in immune cells; kynurenine promotes regulatory T cell differentiation and upregulates PD-1 in CD8+ T cells by AHR signaling, while RA polarizes intratumoral monocyte differentiation toward TAMs via RAR signaling (Devalaraja et al., 2020).

(R)-2-hydroxyglutarate (R-2-HG) and succinate are oncometabolites that act as epigenetic modifiers by interfering with α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)-dependent dioxygenases (Kaelin and McKnight, 2013; Liu and Wellen, 2020; Lu and Thompson, 2012). Apart from intracellular functions, they have recently been shown to mediate intercellular crosstalks. Interestingly, IDH1-mutant glioma-derived R-2-HG is taken up by T cells and perturbs NFAT transcriptional activity and polyamine biosynthesis, resulting in T cell activity suppression. In this context, antitumor immunity is improved by inhibition of the neomorphic enzymatic function of mutant IDH1 (Bunse et al., 2018). In another study, cancer cells release succinate and activate the succinate receptor (SUCNR1)-PI3K-HIF-1α axis to polarize macrophages into TAMs, functionally promoting tumor metastasis (Wu et al., 2020). These findings uncover non-tumor cell-autonomous roles of oncometabolites in shaping the TMEs.

Another notable metabolite is itaconate, which is synthesized from cis-aconitate in the TCA cycle specifically in activated macrophages (O’Neill and Artyomov, 2019). Itaconate was shown to mediate crosstalk between macrophage metabolism and peritoneal tumor growth in murine models. Specifically, tumor cells elicit metabolic reprogramming and itaconate accumulation in peritoneal tissue-resident macrophages, where inhibition of itaconate synthesis impairs MAPK activation and growth of tumors (Weiss et al., 2018). Future studies are required to further understand the functions and mechanisms of itaconate in TMEs.

Other metabolites including amino acids and fatty acids can be linked to intracellular signaling and gene expression. For example, amino acid abundance affects sensors like mTORC1 and GCN2-ATF4 pathways (Goberdhan et al., 2016; Saxton and Sabatini, 2017; Ye et al., 2010), and/or impact downstream metabolites like α-KG, ac-CoA and SAM that interplay with epigenetics (Haas et al., 2016; Liu and Wellen, 2020). Fatty acids are known to directly regulate gene expression by binding to specific transcription factors (Jump et al., 2013). Therefore, these metabolites can also function as signaling molecules through multiple mechanisms, depending on specific TME contexts.

Metabolic Adaptations and Communications in Metastatic TMEs

Metastasis is the leading cause of death in cancer patients (Mehlen and Puisieux, 2006; Valastyan and Weinberg, 2011), yet metabolic mechanisms controlling this highly inefficient and multi-step process are only beginning to be explored. Due to organic-specific features including structural/cellular composition, metabolic/immune profiles and nutrient availability, primary tumor cells accordingly undergo metabolic adaptions and communications in circulation and metastatic TMEs (Doglioni et al., 2019; Elia et al., 2018; Schild et al., 2018) (Figure 5).

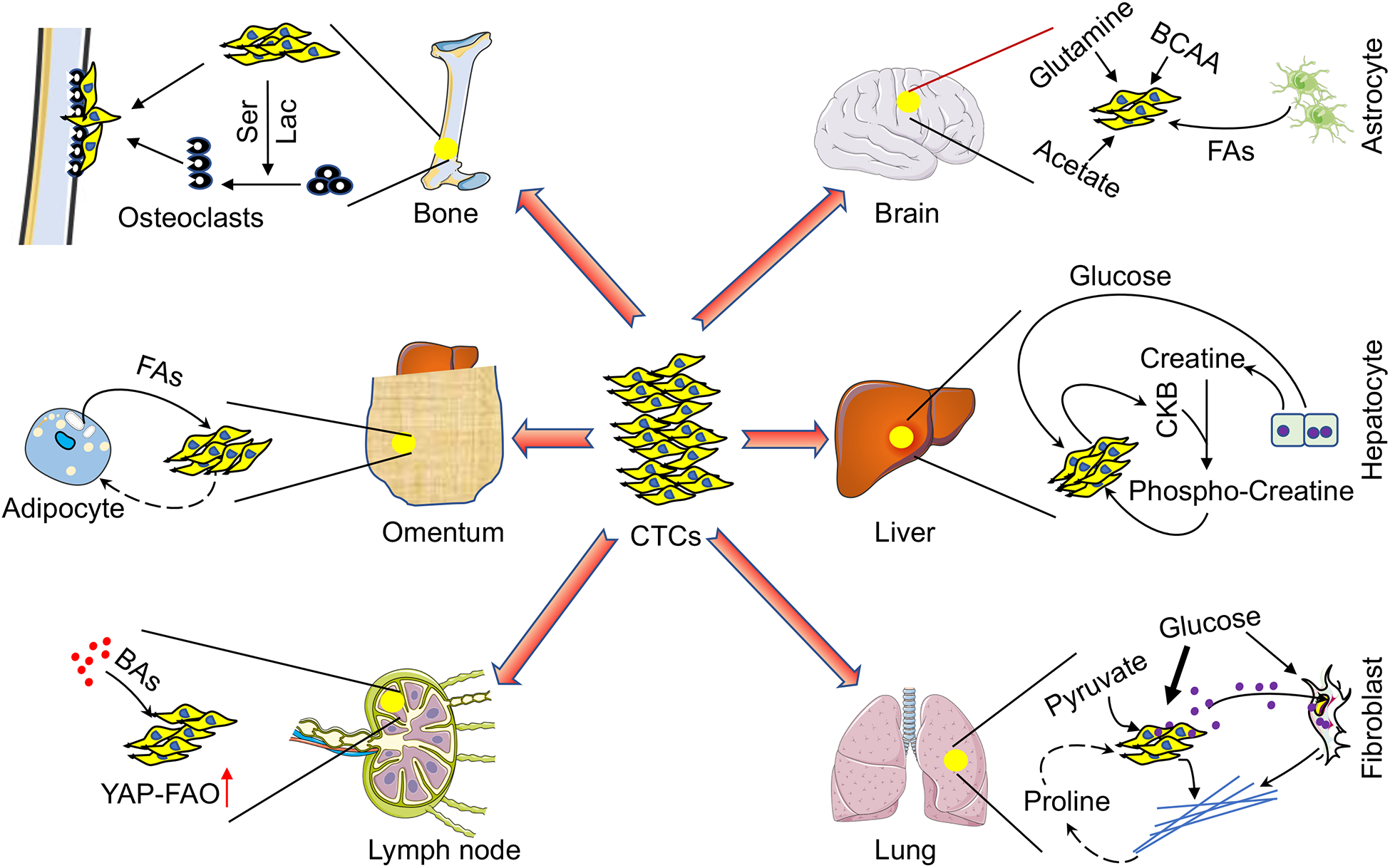

Figure 5. Organ-Specific Metabolic Communication in Metastatic TME.

Brain metastases use acetate, glutamine, branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (FAs) from astrocytes to fuel growth. In addition to glucose, liver metastases produce creatine kinase, brain-type B (CKB) to phosphorylate hepatocyte-derived creatine, and then import phosphocreatine for energy metabolism. Lung metastases preferentially metabolize pyruvate to create a collagen-rich niche which potentially provides proline (Pro) for metastatic growth. Lung metastases also release miR-122-containing exosomes to limit glucose access to fibroblasts. Bone metastases release serine (Ser) and lactate (Lac) to promote osteoclast differentiation and create an osteolytic niche for tumor growth. Adipocytes within the omentum potentially provide fatty acids (FAs) to fuel metastatic growth. Bile acids (BAs) accumulation in the lymph node facilitates metastatic tumor growth by activating the YAP-fatty acid oxidization (FAO) axis.

Metastatic tumor cells must survive the circulation, where oxygen/nutrient availability and cell-matrix interaction are significantly altered. Indeed, circulating melanoma cells experience significant oxidative stress that is a profound barrier for successful metastasis (Piskounova et al., 2015). To shed light on how circulating tumor cells (CTCs) survive, stress conditions have been modeled in vitro and several important metabolic mechanisms have been uncovered. Matrix-deprived metastatic fibrosarcoma cells prevent ROS-induced anoikis by promoting activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2)-induced heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression (Dey et al., 2015). Importantly, stabilization of BACH1 downstream of the NRF2-HO1 axis triggers metabolic remodeling and facilitates glycolysis-dependent metastasis of lung cancer cells (Lignitto et al., 2019; Wiel et al., 2019). The energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is activated in matrix-detached cancer cells to maintain NAPDH homeostasis, by decreasing NADPH consumption in fatty-acid synthesis and increasing NADPH generation via fatty-acid oxidation (FAO) (Jeon et al., 2012). Moreover, cancer cells combine mitochondrial oxidative decarboxylation with cytosolic reductive carboxylation to maintain redox balance and anchorage-independent growth (Jiang et al., 2016). Interestingly, matrix detachment allows cancer cells to form cell clusters and “hypoxia”, driving HIF-1α-mediated mitophagy to clear damaged mitochondria and limit ROS (Labuschagne et al., 2019). Additionally, CTCs increase PGC1α-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis to maintain redox and energetic homeostasis (Lebleu et al., 2014). Together, CTCs can employ several favorable metabolic programs to survive for distal metastasis.

Due to the brain’s unique metabolic rewiring capacity in response to varying nutrient availability, brain metastases display a remarkable metabolic adaptation by utilizing locally abundant non-glucose substrates, including acetate (Mashimo et al., 2014), glutamine and BCAAs (Chen et al., 2015). Additionally, polyunsaturated fatty acids released from astrocytes can activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) and enhance brain metastatic cancer cell proliferation, while systemic administration of PPARγ antagonists significantly reduces brain metastasis in vivo (Zou et al., 2019). Compared with patient-matched extracranial metastases, melanoma brain metastases exhibit enriched OXPHOS that can be therapeutically targeted with IACS-010759, a new complex I inhibitor (Fischer et al., 2019; Molina et al., 2018).

The liver is an integral metabolic organ for whole body energy balance, where metabolic zonation confers metastatic breast tumors the ability to preferentially engage in glycolytic metabolism in hypoxic regions. Here, breast cancer cells upregulate HIF-1α-dependent pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) to limit mitochondrial activity and favor a glycolytic phenotype (Dupuy et al., 2015). Metastatic colorectal cancer cells secret creatine kinase, brain-type B (CKB) to phosphorylate extracellular creatine released from hepatocytes, and then import phosphocreatine to replenish intracellular ATP pools (Loo et al., 2015).

As primary respiration organ in humans, the lungs are exposed to oxidative stress from high levels of oxygen and toxic compounds. Accordingly, lung metastases metabolically withstand oxidative damage, for example, through enhanced mitochondrial biogenesis by PGC1α upregulation (Andrzejewski et al., 2017), or through enhanced FAO by overexpressing aldo-keto reductase AKR1B10 (van Weverwijk et al., 2019). Consistently, fluorouracil-labeled RNA sequencing (Flura-seq) was developed to uncover specific oxidative stress and anti-oxidant gene signatures in murine breast cancer-derived lung micrometastases (Basnet et al., 2019). Intriguingly, due to the particular pyruvate availability in the lungs, metastatic tumors upregulate pyruvate carboxylase (PC) to utilize pyruvate over glutamine to fuel the TCA cycle (Christen et al., 2016); pyruvate metabolism through prolyl-4-hydroxylase (P4HA) creates a collagen-rich niche to support breast cancer-derived lung metastasis (Elia et al., 2019). Since proline catabolism critically supports lung metastases formation (Elia et al., 2017), this collagen-rich niche may also contribute to proline homeostasis in tumors. Moreover, breast tumors also release miR-122-containing exosomes to suppress glucose metabolism in resident lung fibroblasts, increasing the glucose availability for metastatic seeding (Fong et al., 2015).

Bone is a common metastatic site for prostate and breast cancers, where the latter release serine and lactate to promote differentiation and metabolic competency of osteoclasts and form osteolytic metastatic niches (Lemma et al., 2017). Ovarian cancer preferentially metastasizes to omentum, a metabolic organ mainly composed of adipocytes. Co-cultured ovarian cancer cells stimulate lipolysis in adipocytes to produce lipids that are utilized as energy source by cancer cells (Ladanyi et al., 2018; Nieman et al., 2011), suggesting a metabolic mechanism for omental metastatic growth. Finally, metastatic tumor growth in lymph nodes (LNs) relies on FAO driven by transcriptional coactivator yes-associated protein (YAP), which is activated by bile acids accumulated in LNs. Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of FAO suppresses LN metastasis in mice (Lee et al., 2019).

Targeting Metabolic Communications for Cancer Treatment

To exploit metabolic communications for therapeutic intervention, much attention has focused on cancer and immune cells, as deregulated cancer metabolism shapes TMEs that impose metabolic stress on tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, resulting in local immunosuppression and defective tumor surveillance. Therefore, multiple strategies have been avidly explored to target metabolic pathways that enhance antitumor immunity, which are subjects of several recent reviews (Buck et al., 2017; Li et al., 2019; Reina-Campos et al., 2017). Generally, these include targeting cancer-specific metabolic vulnerabilities, limiting immunosuppression and boosting effector functions by enhancing metabolic fitness in tumor specific immune cells. Ideally, a metabolic approach would synergize with immunotherapy to selectively and sustainably eliminate tumor cells. While significant progress has been made in this field, it should be noted that tumor metabolism is dictated by both intrinsic and extrinsic factors (Faubert et al., 2020). Tissue of origin and local microenvironment influence metabolic fitness and rewiring in cancer (Biancur et al., 2017; Davidson et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2020b; Mayers et al., 2016), while certain genetic or epigenetic modifiers and tumor plasticity confer differential sensitivity to metabolic interventions (Li et al., 2015; Lissanu Deribe et al., 2018; Shackelford et al., 2013). Therefore, in the future it’s necessary to stratify certain types of cancer into molecular and metabolic subtypes that are most suited to precision treatment. Along with this, cancer cells within single tumors undergo metabolic remodeling during progression and metastasis, as well as in response to treatment, which results in metabolic reprograming in TMEs, leading to different immune microenvironments. Similarly, immune cells can also develop strategies to adapt to treatments that target metabolism. Understanding these compensatory mechanisms will provide helpful insights to overcome potential resistance to metabolic interventions. Overall, targeting metabolic communication in TMEs should consider tumor type, stage, location and potential compensatory mechanisms.

Concluding Remarks

We present here recent findings on how tumor cells metabolically communicate with stromal cells predominantly in the primary TME. In comparison, metabolic adaptions and communications in the metastatic TME are less clear, partly attributed to metabolic plasticity in metastatic tumors together with complexity of organ-specific local microenvironment. Consequently, it will be imperative to dissect stage-specific metabolic communications along the metastatic cascade, such as those dictating CTC metabolism and survival (Tasdogan et al., 2020), pre-metastatic niche formation (Doglioni et al., 2019), and maintenance of established macro-metastatic microenvironment. Given the complexity of TMEs, the experimental models should not operate in isolation and instead should include both tumor cells and stromal cells, preferentially under conditions that can recapitulate certain metabolic aspects of TME, such as hypoxia and nutrient limitation. For this, experimental systems such as three-dimensional culture, organoid cultures, and co-cultures under stress conditions (hypoxia, low serum, low nutrients), will be helpful. Finally, the mechanisms identified from in vitro systems must be validated in clinically-relevant in vivo models. As we continue to explore the metabolic communications, particularly in the metastatic TME, we will be able to identify more actionable metabolic vulnerabilities, discover metabolic drugs with improved specificity and efficacy, and more precisely target metabolic communications as a single agent or combination therapy. Ultimately, these preclinical findings will be evaluated in clinic and benefit the patients.

Acknowledgement

We apologize to colleagues whose work could not be cited in this review due to space limitations and scope. Research in the Simon laboratory is supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant nos P01CA104838, R35CA197602 and P30CA016520 (to M.C.S.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Ackerman D, Tumanov S, Qiu B, Michalopoulou E, Spata M, Azzam A, Xie H, Simon MC, and Kamphorst JJ (2018). Triglycerides Promote Lipid Homeostasis during Hypoxic Stress by Balancing Fatty Acid Saturation. Cell Rep. 24, 2596–2605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khami AA, Zheng L, Del Valle L, Hossain F, Wyczechowska D, Zabaleta J, Sanchez MD, Dean MJ, Rodriguez PC, and Ochoa AC (2017). Exogenous lipid uptake induces metabolic and functional reprogramming of tumor-associated myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology. 6, e1344804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen E, Miéville P, Warren CM, Saghafinia S, Li L, Peng MW, and Hanahan D (2016). Metabolic Symbiosis Enables Adaptive Resistance to Anti-angiogenic Therapy that Is Dependent on mTOR Signaling. Cell Rep. 15, 1144–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski S, Klimcakova E, Johnson RM, Tabariès S, Annis MG, McGuirk S, Northey JJ, Chénard V, Sriram U, Papadopoli DJ, et al. (2017). PGC-1α Promotes Breast Cancer Metastasis and Confers Bioenergetic Flexibility against Metabolic Drugs. Cell Metab. 26, 778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auciello FR, Bulusu V, Oon C, Tait-Mulder J, Berry M, Bhattacharyya S, Tumanov S, Allen-Petersen BL, Link J, Kendsersky ND, et al. (2019). A stromal lysolipid-autotaxin signaling axis promotes pancreatic tumor progression. Cancer Discov. 9, 617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltazar F, Afonso J, Costa M, and Granja S (2020). Lactate Beyond a Waste Metabolite: Metabolic Affairs and Signaling in Malignancy. Front. Oncol 10, 231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bansal A, and Celeste Simon M (2018). Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. J. Cell Biol 217, 2291–2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basnet H, Tian L, Ganesh K, Huang YH, Macalinao DG, Brogi E, Finley LWS, and Massagué J (2019). Flura-seq identifies organ-specific metabolic adaptations during early metastatic colonization. Elife 8, e43627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensaad K, Favaro E, Lewis CA, Peck B, Lord S, Collins JM, Pinnick KE, Wigfield S, Buffa FM, Li JL, et al. (2014). Fatty acid uptake and lipid storage induced by HIF-1α contribute to cell growth and survival after hypoxia-reoxygenation. Cell Rep. 9, 349–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Berardinis RJ, and Chandel NS (2016). Fundamentals of cancer metabolism. Sci. Adv 2, e1600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biancur DE, Paulo JA, Małachowska B, Del Rey MQ, Sousa CM, Wang X, Sohn ASW, Chu GC, Gygi SP, Harper JW, et al. (2017). Compensatory metabolic networks in pancreatic cancers upon perturbation of glutamine metabolism. Nat. Commun 8, 15965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand A, Singer K, Koehl GE, Kolitzus M, Schoenhammer G, Thiel A, Matos C, Bruss C, Klobuch S, Peter K, et al. (2016). LDHA-Associated Lactic Acid Production Blunts Tumor Immunosurveillance by T and NK Cells. Cell Metab. 8, 657–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck MD, Sowell RT, Kaech SM, and Pearce EL (2017). Metabolic Instruction of Immunity. Cell. 169, 570–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunse L, Pusch S, Bunse T, Sahm F, Sanghvi K, Friedrich M, Alansary D, Sonner JK, Green E, Deumelandt K, et al. (2018). Suppression of antitumor T cell immunity by the oncometabolite (R)-2-hydroxyglutarate. Nat. Med 24, 1192–1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y (2019). Adipocyte and lipid metabolism in cancer drug resistance. J. Clin. Invest 129, 3006–3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascone T, McKenzie JA, Mbofung RM, Punt S, Wang Z, Xu C, Williams LJ, Wang Z, Bristow CA, Carugo A, et al. (2018). Increased Tumor Glycolysis Characterizes Immune Resistance to Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Cell Metab. 27, 977–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CH, Qiu J, O’Sullivan D, Buck MD, Noguchi T, Curtis JD, Chen Q, Gindin M, Gubin MM, Van Der Windt GJW, et al. (2015). Metabolic Competition in the Tumor Microenvironment Is a Driver of Cancer Progression. Cell. 162, 1229–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhri VK, Salzler GG, Dick SA, Buckman MS, Sordella R, Karoly ED, Mohney R, Stiles BM, Elemento O, Altorki NK, et al. (2013). Metabolic alterations in lung cancer-associated fibroblasts correlated with increased glycolytic metabolism of the tumor. Mol. Cancer Res 11, 579–592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Lee HJ, Wu X, Huo L, Kim SJ, Xu L, Wang Y, He J, Bollu LR, Gao G, et al. (2015). Gain of glucose-independent growth upon metastasis of breast cancer cells to the brain. Cancer Res. 75, 554–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YJ, Mahieu NG, Huang X, Singh M, Crawford PA, Johnson SL, Gross RW, Schaefer J, and Patti GJ (2016). Lactate metabolism is associated with mammalian mitochondria. Nat. Chem. Biol 12, 937–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christen S, Lorendeau D, Schmieder R, Broekaert D, Metzger K, Veys K, Elia I, Buescher JM, Orth MF, Davidson SM, et al. (2016). Breast Cancer-Derived Lung Metastases Show Increased Pyruvate Carboxylase-Dependent Anaplerosis. Cell Rep. 17, 837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegio OR, Chu NQ, Szabo AL, Chu T, Rhebergen AM, Jairam V, Cyrus N, Brokowski CE, Eisenbarth SC, Phillips GM, et al. (2014). Functional polarization of tumour-associated macrophages by tumour-derived lactic acid. Nature. 513, 559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M, Kenny HA, Ashcroft B, Mukherjee A, Johnson A, Zhang Y, Helou Y, Batlle R, Liu X, Gutierrez N, et al. (2019). Fibroblasts Mobilize Tumor Cell Glycogen to Promote Proliferation and Metastasis. Cell Metab. 29, 141–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson SM, Papagiannakopoulos T, Olenchock BA, Heyman JE, Keibler MA, Luengo A, Bauer MR, Jha AK, O’Brien JP, Pierce KA, et al. (2016). Environment impacts the metabolic dependencies of ras-driven non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Metab. 23, 517–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devalaraja S, To TKJ, Folkert IW, Natesan R, Alam MZ, Li M, Tada Y, Budagyan K, Dang MT, Zhai L, et al. (2020). Tumor-Derived Retinoic Acid Regulates Intratumoral Monocyte Differentiation to Promote Immune Suppression. Cell. 180, 1098–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dey S, Sayers CM, Verginadis II, Lehman SL, Cheng Y, Cerniglia GJ, Tuttle SW, Feldman MD, Paul PJ, Fuchs SY, et al. (2015). ATF4-dependent induction of heme oxygenase 1 prevents anoikis and promotes metastasis. J. Clin. Invest 125, 2592–2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietl K, Renner K, Dettmer K, Timischl B, Eberhart K, Dorn C, Hellerbrand C, Kastenberger M, Kunz-Schughart LA, Oefner PJ, et al. (2010). Lactic Acid and Acidification Inhibit TNF Secretion and Glycolysis of Human Monocytes. J. Immunol 184, 1200–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doglioni G, Parik S, and Fendt SM (2019). Interactions in the (pre)metastatic niche support metastasis formation. Front. Oncol 9, 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donohoe CL, Lysaght J, O’Sullivan J, and Reynolds JV (2017). Emerging Concepts Linking Obesity with the Hallmarks of Cancer. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 28, 46–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du K, Hyun J, Premont RT, Choi SS, Michelotti GA, Swiderska-Syn M, Dalton GD, Thelen E, Dupuy F, Tabariès S, Andrzejewski S, Dong Z, Blagih J, Annis MG, Omeroglu A, Gao D, Leung S, Amir E, et al. (2015). PDK1-dependent metabolic reprogramming dictates metastatic potential in breast cancer. Cell Metab. 22, 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia I, Broekaert D, Christen S, Boon R, Radaelli E, Orth MF, Verfaillie C, Grünewald TGP, and Fendt SM (2017). Proline metabolism supports metastasis formation and could be inhibited to selectively target metastasizing cancer cells. Nat. Commun 8, 15267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia I, Doglioni G, and Fendt SM (2018). Metabolic Hallmarks of Metastasis Formation. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia I, Rossi M, Stegen S, Broekaert D, Doglioni G, van Gorsel M, Boon R, Escalona-Noguero C, Torrekens S, Verfaillie C, et al. (2019). Breast cancer cells rely on environmental pyruvate to shape the metastatic niche. Nature. 568, 117–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faubert B, Li KY, Cai L, Hensley CT, Kim J, Zacharias LG, Yang C, Do QN, Doucette S, Burguete D, et al. (2017). Lactate Metabolism in Human Lung Tumors. Cell. 171, 358–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faubert B, Solmonson A, and DeBerardinis RJ (2020). Metabolic reprogramming and cancer progression. Science. 368, eaaw5473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiaschi T, Marini A, Giannoni E, Taddei ML, Gandellini P, De Donatis A, Lanciotti M, Serni S, Cirri P, and Chiarugi P (2012). Reciprocal metabolic reprogramming through lactate shuttle coordinately influences tumor-stroma interplay. Cancer Res. 72, 5130–5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer GM, Jalali A, Kircher DA, Lee WC, McQuade JL, Haydu LE, Joon AY, Reuben A, de Macedo MP, Carapeto FCL, et al. (2019). Molecular profiling reveals unique immune and metabolic features of melanoma brain metastases. Cancer Discov. 9, 628–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K, Hoffmann P, Voelkl S, Meidenbauer N, Ammer J, Edinger M, Gottfried E, Schwarz S, Rothe G, Hoves S, et al. (2007). Inhibitory effect of tumor cell-derived lactic acid on human T cells. Blood. 109, 3812–3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher M, Ramirez ME, Sierra RA, Raber P, Thevenot P, Al-Khami AA, Sanchez-Pino D, Hernez C, Wyczechowska DD, Ochoa AC, et al. (2015). L-Arginine depletion blunts antitumor T-cell responses by inducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 75, 275–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong L, Hotson A, Powderly JD, Sznol M, Heist RS, Choueiri TK, George S, Hughes BGM, Hellmann MD, Shepard DR, et al. (2020). Adenosine 2A receptor blockade as an immunotherapy for treatment-refractory renal cell cancer. Cancer Discov. 10, 40–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong MY, Zhou W, Liu L, Alontaga AY, Chandra M, Ashby J, Chow A, O’Connor STF, Li S, Chin AR, et al. (2015). Breast-cancer-secreted miR-122 reprograms glucose metabolism in premetastatic niche to promote metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol 17, 183–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger R, Rieckmann JC, Wolf T, Basso C, Feng Y, Fuhrer T, Kogadeeva M, Picotti P, Meissner F, Mann M, et al. (2016). L-Arginine Modulates T Cell Metabolism and Enhances Survival and Anti-tumor Activity. Cell. 167, 829–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goberdhan DCI, Wilson C, and Harris AL (2016). Amino Acid Sensing by mTORC1: Intracellular Transporters Mark the Spot. Cell Metab. 23, 580–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouirand V, Guillaumond F, and Vasseur S (2018). Influence of the tumor microenvironment on cancer cells metabolic reprogramming. Front. Oncol 8, 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Roy A, and Dwarakanath BS (2017). Metabolic cooperation and competition in the tumor microenvironment: Implications for therapy. Front. Oncol 7, 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas R, Cucchi D, Smith J, Pucino V, Macdougall CE, and Mauro C (2016). Intermediates of Metabolism: From Bystanders to Signalling Molecules. Trends Biochem. Sci 41, 460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, and Weinberg RA (2011). Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144, 646–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G, Linden J, Cronstein B, and Pacher P (2008). Adenosine receptors: Therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 7, 757–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, and DeBerardinis RJ (2017). Understanding the Intersections between Metabolism and Cancer Biology. Cell. 168, 657–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensley CT, Faubert B, Yuan Q, Lev-Cohain N, Jin E, Kim J, Jiang L, Ko B, Skelton R, Loudat L, et al. (2016). Metabolic Heterogeneity in Human Lung Tumors. Cell. 164, 681–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PC, Bihuniak JD, MacIntyre AN, Staron M, Liu X, Amezquita R, Tsui YC, Cui G, Micevic G, Perales JC, et al. (2015). Phosphoenolpyruvate Is a Metabolic Checkpoint of Anti-tumor T Cell Responses. Cell 162, 1217–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy AJ, Balaban S, and Saunders DN (2017). Adipocyte-Tumor Cell Metabolic Crosstalk in Breast Cancer. Trends Mol. Med 23, 381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SM, Chandel NS, and Hay N (2012). AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature. 485, 661–665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Shestov AA, Swain P, Yang C, Parker SJ, Wang QA, Terada LS, Adams ND, McCabe MT, Pietrak B, et al. (2016). Reductive carboxylation supports redox homeostasis during anchorage-independent growth. Nature 532, 255–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jump DB, Tripathy S, and Depner CM (2013). Fatty Acid-Regulated Transcription Factors in the Liver. Annu. Rev. Nutr 33, 249–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG, and McKnight SL (2013). Influence of metabolism on epigenetics and disease. Cell. 153, 56–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalluri R (2016). The biology and function of fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 582–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedia-Mehta N, and Finlay DK (2019). Competition for nutrients and its role in controlling immune responses. Nat. Commun 10, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshet R, Szlosarek P, Carracedo A, and Erez A (2018). Rewiring urea cycle metabolism in cancer to support anabolism. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 634–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Harris AL, and Sivridis E (2006). Comparison of metabolic pathways between cancer cells and stromal cells in colorectal carcinomas: A metabolic survival role for tumor-associated stroma. Cancer Res. 66, 632–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cruz-López KG, Castro-Muñoz LJ, Reyes-Hernández DO, García-Carrancá A, and Manzo-Merino J (2019). Lactate in the Regulation of Tumor Microenvironment and Therapeutic Approaches. Front. Oncol 9, 1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labuschagne CF, Cheung EC, Blagih J, Domart MC, and Vousden KH (2019). Cell Clustering Promotes a Metabolic Switch that Supports Metastatic Colonization. Cell Metab. 30, 720–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladanyi A, Mukherjee A, Kenny HA, Johnson A, Mitra AK, Sundaresan S, Nieman KM, Pascual G, Benitah SA, Montag A, et al. (2018). Adipocyte-induced CD36 expression drives ovarian cancer progression and metastasis. Oncogene. 37, 2285–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamas B, Vergnaud-Gauduchon J, Goncalves-Mendes N, Perche O, Rossary A, Vasson MP, and Lebleu VS, O’Connell JT, Gonzalez Herrera KN, Wikman H, Pantel K, Haigis MC, De Carvalho FM, Damascena A, Domingos Chinen LT, Rocha RM, et al. (2014). PGC-1α mediates mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation in cancer cells to promote metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol 16, 992–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. kun, Jeong S. hwan, Jang C, Bae H, Kim YH, Park I, Kim SK, and Koh GY (2019). Tumor metastasis to lymph nodes requires YAP-dependent metabolic adaptation. Science. 363, 644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Sohn HA, Park ZY, Oh S, Kang YK, Lee KM, Kang M, Jang YJ, Yang SJ, Hong YK, et al. (2015). A lactate-induced response to hypoxia. Cell 161, 595–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Chandel NS, and Simon MC (2020a). Cellular adaptation to hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factors and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 21, 268–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P, Malik D, Perkons N, Huangyang P, Khare S, Rhoades S, Gong YY, Burrows M, Finan JM, Nissim I, et al. (2020b). Targeting glutamine metabolism slows soft tissue sarcoma growth. Nat. Commun 11, 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehúede C, Dupuy F, Rabinovitch R, Jones RG, and Siegel PM (2016). Metabolic plasticity as a determinant of tumor growth and metastasis. Cancer Res. 76, 5201–5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemma S, Di Pompo G, Porporato PE, Sboarina M, Russell S, Gillies RJ, Baldini N, Sonveaux P, and Avnet S (2017). MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells fuel osteoclast metabolism and activity: A new rationale for the pathogenesis of osteolytic bone metastases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Basis Dis 1863, 3254–3264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel E, Makowski L, DiGiovanni J, and Kolonin MG (2018). Cancer as a Matter of Fat: The Crosstalk between Adipose Tissue and Tumors. Trends in Cancer. 4, 374–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Han X, Li F, Wang R, Wang H, Gao Y, Wang X, Fang Z, Zhang W, Yao S, et al. (2015). LKB1 Inactivation Elicits a Redox Imbalance to Modulate Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Plasticity and Therapeutic Response. Cancer Cell. 27, 698–711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Huangyang P, Burrows M, Guo K, Riscal R, Godfrey J, Lee KE, Lin N, Lee P, Blair IA, et al. (2020). FBP1 loss disrupts liver metabolism and promotes tumorigenesis through a hepatic stellate cell senescence secretome. Nat. Cell Biol 22, 728–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wenes M, Romero P, Huang SCC, Fendt SM, and Ho PC (2019). Navigating metabolic pathways to enhance antitumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol 16, 425–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lignitto L, LeBoeuf SE, Homer H, Jiang S, Askenazi M, Karakousi TR, Pass HI, Bhutkar AJ, Tsirigos A, Ueberheide B, et al. (2019). Nrf2 Activation Promotes Lung Cancer Metastasis by Inhibiting the Degradation of Bach1. Cell. 178, 316–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissanu Deribe Y, Sun Y, Terranova C, Khan F, Martinez-Ledesma J, Gay J, Gao G, Mullinax RA, Khor T, Feng N, et al. (2018). Mutations in the SWI/SNF complex induce a targetable dependence on oxidative phosphorylation in lung cancer. Nat. Med 24, 1047–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JY, and Wellen KE (2020). Advances into understanding metabolites as signaling molecules in cancer progression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 63, 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Cooper DE, Cluntun AA, Warmoes MO, Zhao S, Reid MA, Liu J, Lund PJ, Lopes M, Garcia BA, et al. (2018a). Acetate Production from Glucose and Coupling to Mitochondrial Metabolism in Mammals. Cell. 175, 502–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liang X, Dong W, Fang Y, Lv J, Zhang T, Fiskesund R, Xie J, Liu J, Yin X, et al. (2018b). Tumor-Repopulating Cells Induce PD-1 Expression in CD8+ T Cells by Transferring Kynurenine and AhR Activation. Cancer Cell. 33, 480–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locasale JW (2013). Serine, glycine and one-carbon units: Cancer metabolism in full circle. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 572–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loo JM, Scherl A, Nguyen A, Man FY, Weinberg E, Zeng Z, Saltz L, Paty PB, and Tavazoie SF (2015). Extracellular metabolic energetics can promote cancer progression. Cell. 160, 393–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, and Thompson CB (2012). Metabolic regulation of epigenetics. Cell Metab. 16, 9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyssiotis CA, and Kimmelman AC (2017). Metabolic Interactions in the Tumor Microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 863–875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma EH, Bantug G, Griss T, Condotta S, Johnson RM, Samborska B, Mainolfi N, Suri V, Guak H, Balmer ML, et al. (2017). Serine Is an Essential Metabolite for Effector T Cell Expansion. Cell Metab. 25, 345–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashimo T, Pichumani K, Vemireddy V, Hatanpaa KJ, Singh DK, Sirasanagandla S, Nannepaga S, Piccirillo SG, Kovacs Z, Foong C, et al. (2014). Acetate is a bioenergetic substrate for human glioblastoma and brain metastases. Cell. 159, 1603–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattaini KR, Sullivan MR, and Vander Heiden MG (2016). The importance of serine metabolism in cancer. J. Cell Biol 214, 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayers JR, Torrence ME, Danai LV, Papagiannakopoulos T, Davidson SM, Bauer MR, Lau AN, Ji BW, Dixit PD, Hosios AM, et al. (2016). Tissue of origin dictates branched-chain amino acid metabolism in mutant Kras-driven cancers. Science. 353, 1161–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P, and Puisieux A (2006). Metastasis: A question of life or death. Nat. Rev. Cancer 6, 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, and Bradfield CA (2010). An Interaction between Kynurenine and the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Can Generate Regulatory T Cells. J. Immunol 185, 3190–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molina JR, Sun Y, Protopopova M, Gera S, Bandi M, Bristow C, McAfoos T, Morlacchi P, Ackroyd J, Agip ANA, et al. (2018). An inhibitor of oxidative phosphorylation exploits cancer vulnerability. Nat. Med 24, 1036–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondanelli G, Ugel S, Grohmann U, and Bronte V (2017). The immune regulation in cancer by the amino acid metabolizing enzymes ARG and IDO. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol 35, 30–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn DH, Shafizadeh E, Attwood JT, Bondarev I, Pashine A, and Mellor AL (1999). Inhibition of T cell proliferation by macrophage tryptophan catabolism. J. Exp. Med 189, 1363–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima EC, and Van Houten B (2013). Metabolic symbiosis in cancer: Refocusing the Warburg lens. Mol. Carcinog 52, 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa MS, Keith B, and Simon MC (2016). Oxygen availability and metabolic adaptations. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 663–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieman KM, Kenny HA, Penicka CV, Ladanyi A, Buell-Gutbrod R, Zillhardt MR, Romero IL, Carey MS, Mills GB, Hotamisligil GS, et al. (2011). Adipocytes promote ovarian cancer metastasis and provide energy for rapid tumor growth. Nat. Med 17, 1498–1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu Z, Shi Q, Zhang W, Shu Y, Yang N, Chen B, Wang Q, Zhao X, Chen J, Cheng N, et al. (2017). Caspase-1 cleaves PPARγ for potentiating the pro-tumor action of TAMs. Nat. Commun 8, 766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill LAJ, and Artyomov MN (2019). Itaconate: the poster child of metabolic reprogramming in macrophage function. Nat. Rev. Immunol 19, 273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochocki JD, Khare S, Hess M, Ackerman D, Qiu B, Daisak JI, Worth AJ, Lin N, Lee P, Xie H, et al. (2018). Arginase 2 Suppresses Renal Carcinoma Progression via Biosynthetic Cofactor Pyridoxal Phosphate Depletion and Increased Polyamine Toxicity. Cell Metab.27, 1263–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivares O, Mayers JR, Gouirand V, Torrence ME, Gicquel T, Borge L, Lac S, Roques J, Lavaut MN, Berthezène P, et al. (2017). Collagen-derived proline promotes pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cell survival under nutrient limited conditions. Nat. Commun 8 16031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz CA, Litzenburger UM, Sahm F, Ott M, Tritschler I, Trump S, Schumacher T, Jestaedt L, Schrenk D, Weller M, et al. (2011). An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature. 478, 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacold ME, Brimacombe KR, Chan SH, Rohde JM, Lewis CA, Swier LJYM, Possemato R, Pan M, Reid MA, Lowman XH, Kulkarni RP, Tran TQ, Liu X, Yang Y, Hernandez-Davies JE, Rosales KK, Li H, et al. (2016). Regional glutamine deficiency in tumours promotes dedifferentiation through inhibition of histone demethylation. Nat. Cell Biol 18, 1090–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil MD, Bhaumik J, Babykutty S, Banerjee UC, and Fukumura D (2016). Arginine dependence of tumor cells: Targeting a chink in cancer’s armor. Oncogene. 35, 4957–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, Wang C, Fortina P, Addya S, et al. (2009). The reverse Warburg effect: Aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell Cycle. 3984–3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlova NN, and Thompson CB (2016). The Emerging Hallmarks of Cancer Metabolism. Cell Metab. 23, 27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarsky L, Bill R, Fagiani E, Dimeloe S, Goosen RW, Hagmann J, Hess C, and Christofori G (2016). Targeting Metabolic Symbiosis to Overcome Resistance to Anti-angiogenic Therapy. Cell Rep.15, 1161–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piskounova E, Agathocleous M, Murphy MM, Hu Z, Huddlestun SE, Zhao Z, Leitch AM, Johnson TM, DeBerardinis RJ, and Morrison SJ (2015). Oxidative stress inhibits distant metastasis by human melanoma cells. Nature 527, 186–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platten M, Wick W, and Van Den Eynde BJ (2012). Tryptophan catabolism in cancer: Beyond IDO and tryptophan depletion. Cancer Res. 72, 5435–5440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu B, Ackerman D, Sanchez DJ, Li B, Ochocki JD, Grazioli A, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Alan Diehl J, Keith B, and Celeste Simon M (2016). HIF2α-dependent lipid storage promotes endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 5, 652–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramani K, and Lu SC (2017). Methionine adenosyltransferases in liver health and diseases. Liver Res. 1, 103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rattigan YI, Patel BB, Ackerstaff E, Sukenick G, Koutcher JA, Glod JW, and Banerjee D (2012). Lactate is a mediator of metabolic cooperation between stromal carcinoma associated fibroblasts and glycolytic tumor cells in the tumor microenvironment. Exp. Cell Res 318, 326–335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recouvreux MV, and Commisso C (2017). Macropinocytosis: A metabolic adaptation to nutrient stress in cancer. Front. Endocrinol 8, 261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reina-Campos M, Moscat J, and Diaz-Meco M (2017). Metabolism shapes the tumor microenvironment. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 48, 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner K, Singer K, Koehl GE, Geissler EK, Peter K, Siska PJ, and Kreutz M (2017). Metabolic hallmarks of tumor and immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Front. Immunol 8, 248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards KE, Zeleniak AE, Fishel ML, Wu J, Littlepage LE, and Hill R (2017). Cancer-associated fibroblast exosomes regulate survival and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 36, 1770–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizi BS, Caneba C, Nowicka A, Nabiyar AW, Liu X, Chen K, Klopp A, and Nagrath D (2015). Nitric oxide mediates metabolic coupling of omentum-derived adipose stroma to ovarian and endometrial cancer cells. Cancer Res. 75, 456–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy DG, Chen J, Mamane V, Ma EH, Muhire BM, Sheldon RD, Shorstova T, Koning R, Johnson RM, Esaulova E, et al. (2020). Methionine Metabolism Shapes T Helper Cell Responses through Regulation of Epigenetic Reprogramming. Cell Metab. 31, 256–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton RA, and Sabatini DM (2017). mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell. 169, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild T, Low V, Blenis J, and Gomes AP (2018). Unique Metabolic Adaptations Dictate Distal Organ-Specific Metastatic Colonization. Cancer Cell 33, 347–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford DB, Abt E, Gerken L, Vasquez DS, Seki A, Leblanc M, Wei L, Fishbein MC, Czernin J, Mischel PS, et al. (2013). LKB1 Inactivation Dictates Therapeutic Response of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer to the Metabolism Drug Phenformin. Cancer Cell. 23, 143–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonveaux P, Végran F, Schroeder T, Wergin MC, Verrax J, Rabbani ZN, De Saedeleer CJ, Kennedy KM, Diepart C, Jordan BF, et al. (2008). Targeting lactate-fueled respiration selectively kills hypoxic tumor cells in mice. J. Clin. Invest 118, 3930–3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa CM, Biancur DE, Wang X, Halbrook CJ, Sherman MH, Zhang L, Kremer D, Hwang RF, Witkiewicz AK, Ying H, et al. (2016). Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature. 536, 479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spees JL, Olson SD, Whitney MJ, and Prockop DJ (2006). Mitochondrial transfer between cells can rescue aerobic respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 103, 1283–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli JB, Yoon H, Ringel AE, Jeanfavre S, Clish CB, and Haigis MC (2017). Metabolic recycling of ammonia via glutamate dehydrogenase supports breast cancer biomass. Science. 358, 941–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LB, and Chandel NS (2014). Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and cancer. Cancer Metab.2, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasdogan A, Faubert B, Ramesh V, Ubellacker JM, Shen B, Solmonson A, Murphy MM, Gu Z, Gu W, Martin M, et al. (2020). Metabolic heterogeneity confers differences in melanoma metastatic potential. Nature 577, 115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valastyan S, and Weinberg RA (2011). Tumor metastasis: Molecular insights and evolving paradigms. Cell. 147, 275–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinay DS, Ryan EP, Pawelec G, Talib WH, Stagg J, Elkord E, Lichtor T, Decker WK, Whelan RL, Kumara HMCS, et al. (2015). Immune evasion in cancer: Mechanistic basis and therapeutic strategies. Semin. Cancer Biol 35, S185–S198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Kryczek I, Dostál L, Lin H, Tan L, Zhao L, Lu F, Wei S, Maj T, Peng D, et al. (2016). Effector T Cells Abrogate Stroma-Mediated Chemoresistance in Ovarian Cancer. Cell. 165, 1092–1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss JM, Davies LC, Karwan M, Ileva L, Ozaki MK, Cheng RYS, Ridnour LA, Annunziata CM, Wink DA, and McVicar DW (2018). Itaconic acid mediates crosstalk between macrophage metabolism and peritoneal tumors. J. Clin. Invest 128, 3794–3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Weverwijk A, Koundouros N, Iravani M, Ashenden M, Gao Q, Poulogiannis G, Jungwirth U, and Isacke CM (2019). Metabolic adaptability in metastatic breast cancer by AKR1B10-dependent balancing of glycolysis and fatty acid oxidation. Nat. Commun 10 2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker-Menezes D, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Lin Z, Ertel A, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Birbe RC, Howell A, Pavlides S, Gandara R, et al. (2011). Evidence for a stromal-epithelial “lactate shuttle” in human tumors: MCT4 is a marker of oxidative stress in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Cell Cycle. 10, 1772–1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiel C, Le Gal K, Ibrahim MX, Jahangir CA, Kashif M, Yao H, Ziegler DV, Xu X, Ghosh T, Mondal T, et al. (2019). BACH1 Stabilization by Antioxidants Stimulates Lung Cancer Metastasis. Cell. 178, 330–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolthuis CM, Stranahan AW, Park CY, Minhajuddin M, Gasparetto M, Stevens B, Pei S, and Jordan CT (2016). Leukemic Stem Cells Evade Chemotherapy by Metabolic Adaptation to an Adipose Tissue Niche. Cell Stem Cell. 19, 23–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Huang TW, Hsieh YT, Wang YF, Yen CC, Lee GL, Yeh CC, Peng YJ, Kuo YY, Wen HT, et al. (2020). Cancer-Derived Succinate Promotes Macrophage Polarization and Cancer Metastasis via Succinate Receptor. Mol. Cell 77,213–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, and Vousden KH (2016). Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 16, 650–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Achreja A, Yeung TL, Mangala LS, Jiang D, Han C, Baddour J, Marini JC, Ni J, Nakahara R, et al. (2016). Targeting Stromal Glutamine Synthetase in Tumors Disrupts Tumor Microenvironment-Regulated Cancer Cell Growth. Cell Metab. 24, 685–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Garcia Canaveras JC, Chen Z, Wang L, Liang L, Jang C, Mayr JA, Zhang Z, Ghergurovich JM, Zhan L, et al. (2020). Serine Catabolism Feeds NADH when Respiration Is Impaired. Cell Metab. 31, 809–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Kumanova M, Hart LS, Sloane K, Zhang H, De Panis DN, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Ron D, and Koumenis C (2010). The GCN2-ATF4 pathway is critical for tumour cell survival and proliferation in response to nutrient deprivation. EMBO J. 29, 2082–2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye J, Fan J, Venneti S, Wan YW, Pawel BR, Zhang J, Finley LWS, Lu C, Lindsten T, Cross JR, et al. (2014). Serine catabolism regulates mitochondrial redox control during hypoxia. Cancer Discov. 4, 1406–1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RM, Ackerman D, Quinn ZL, Mancuso A, Gruber M, Liu L, Giannoukos DN, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Keith B, et al. (2013). Dysregulated mTORC1 renders cells critically dependent on desaturated lipids for survival under tumor-like stress. Genes Dev. 27, 1115–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Wang Y, Shi Z, Liu J, Sun P, Hou X, Zhang J, Zhao S, Zhou BP, and Mi J (2015). Metabolic Reprogramming of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts by IDH3α Downregulation. Cell Rep. 10, 1335–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]