Abstract

The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag precursor specifically selects the unspliced viral genomic RNA (gRNA) from the bulk of cellular and spliced viral RNAs via its nucleocapsid (NC) domain and drives gRNA encapsidation at the plasma membrane (PM). To further identify the determinants governing the intracellular trafficking of Gag-gRNA complexes and their accumulation at the PM, we compared, in living and fixed cells, the interactions between gRNA and wild-type Gag or Gag mutants carrying deletions in NC zinc fingers (ZFs) or a nonmyristoylated version of Gag. Our data showed that the deletion of both ZFs simultaneously or the complete NC domain completely abolished intracytoplasmic Gag-gRNA interactions. Deletion of either ZF delayed the delivery of gRNA to the PM but did not prevent Gag-gRNA interactions in the cytoplasm, indicating that the two ZFs display redundant roles in this respect. However, ZF2 played a more prominent role than ZF1 in the accumulation of the ribonucleoprotein complexes at the PM. Finally, the myristate group, which is mandatory for anchoring the complexes at the PM, was found to be dispensable for the association of Gag with the gRNA in the cytosol.

Significance

Formation of HIV-1 retroviral particles relies on specific interactions between the retroviral Gag precursor and the unspliced genomic RNA (gRNA). During the late phase of replication, Gag orchestrates the assembly of newly formed viruses at the plasma membrane (PM). It has been shown that the intracellular HIV-1 gRNA recognition is governed by the two zinc finger (ZF) motifs of the nucleocapsid domain in Gag. Here, we provided a clear picture of the role of ZFs in the cellular trafficking of Gag-gRNA complexes to the PM by showing that either ZF was sufficient to efficiently promote these interactions in the cytoplasm, whereas interestingly, ZF2 played a more prominent role in the relocation of these ribonucleoprotein complexes at the PM assembly sites.

Introduction

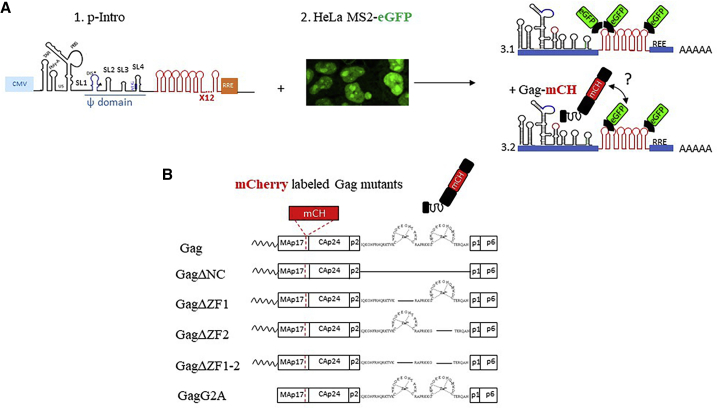

During the late phase of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication, the retroviral 55-kDa precursor (Pr55Gag or Gag) orchestrates the assembly of newly formed viruses at the plasma membrane (PM) (1, 2, 3). Gag specifically selects the HIV-1 unspliced genomic RNA (gRNA) from the bulk of cellular and spliced viral RNAs for encapsidation via its nucleocapsid domain (NC). This process involves specific interactions between Gag and the 5′ end of the gRNA, which contains the packaging signal (Psi) encompassing stem loop 1 (SL1) to SL4 (Fig. 1 A) (for reviews, see (4, 5, 6, 7)). SL1 corresponds to the Dimerization Initiation Site (DIS) as it contains a short palindromic sequence in its apical loop that drives dimerization of the HIV-1 gRNA (8, 9, 10, 11, 12), and our group previously showed that the SL1 internal purine-rich loop corresponds to a major Gag recognition signal (13, 14, 15). SL2 contains the major splice donor site, SL3 has been historically considered as the main packaging signal (Psi) (16,17), and SL4 contains the translation initiation codon of Gag.

Figure 1.

Fluorescent tools used for microscopy imaging. (A) (1) Schematic presentation of the HIV-1 reporter construct (pIntro) is shown. The RNA obtained from the cytomegalovirus-dependent (light blue square) transcription of this plasmid contains 12 copies of MS2 stem loops (SL) inserted between the Psi (ψ) domain and RRE element. (2) HeLa cells constitutively expressing MS2-eGFP are shown. The fluorescence was found to be localized in the nucleus and concentrated in the nucleoli in nontransfected cells (23). (3) Shown are schemes of the unspliced nascent HIV-1 mRNAs harboring the SL elements that can be recognized by dimers of the fluorescently labeled MS2 capsid (CA) proteins (MS2-eGFP) and interact with mCH-labeled Gag proteins. eGFP and m-Cherry constitute a donor-acceptor couple for FRET. (B) Shown is a schematic representation of the Gag proteins used in this study. Gag domains are represented: from N-terminus the myristoyl group, matrix (MA), capsid (CA), nucleocapsid (NC), including two zinc fingers (ZFs), the spacer peptides p1 and p2, and the C-terminal p6 domain. We deleted either the entire NC domain (GagΔNC), both ZFs (GagΔZF1-2), or only one ZF (GagΔZF1 and GagΔZF2). We also included in our study a nonmyristoylated version of Gag (GagG2A). The deletions were represented by a straight line linking the bordering amino acid residues. All the Gag proteins were fused to mCherry (mCH), which was inserted between the MA and CA domains (63). To see this figure in color, go online.

Using imaging techniques, several groups showed that gRNA dimerization precedes the budding of viral particles (18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24). Indeed, it was proposed that HIV-1 gRNA dimerizes at the PM (24), and the dimers would be stabilized at those sites thanks to the chaperone activity of Gag (18,19,25,26). Other studies showed that HIV-1 gRNA would migrate to the PM as a preformed dimer (18,23) in association with low-order Gag multimers (25, 26, 27), forming a viral ribonucleoprotein (vRNP) (for reviews, (6,28,29)). Although some aspects, including the cellular trafficking of the vRNP, remain to be precisely described, it was suggested that the viral core could be alternatively targeted to late endosomes (30, 31, 32, 33), and the dynein motor function could regulate the vRNP egress on endosomal membranes, thus impacting viral production (34).

The Gag precursor is composed of four main domains and two short spacers (for review, see (35)) (Fig. 1 B), starting from the N-terminus with the matrix (MA) domain, which mediates the association of Gag with the PM (36) via its N-terminal myristoylated glycine (G2) and a highly basic region, which associates with PI(4,5)P2 (37,38). The capsid (CA) domain drives Gag multimerization, leading to the formation of the structural viral core. Besides, recent MD simulation studies indicated that CA interacts with MA, stabilizing the compact conformation of the precursor (39). The NC domain flanked by two spacer peptides p2 and p1 contains two CCHC zinc finger (ZF) motifs and constitutes the major determinant for gRNA recognition (40, 41, 42). Importantly, the NC domain was also found to facilitate Gag multimerization and viral assembly (43, 44, 45, 46), and its fully matured form, NCp7, fulfills multiple functions in the early steps of the viral cycle by acting as a nucleic acid chaperone. As such, NCp7 is thought to mediate structural gRNA rearrangements (for reviews, see (47, 48, 49)). Finally, at the C-terminus, the p6 domain promotes the budding of nascent virions at the PM by interacting with host factors associated with the ESCRT (Endosomal Sorting Complex Required for Transport) machinery (for a review, see (50)). Our group recently showed that p6 is also a key determinant for specific Gag-gRNA interaction (51).

Both MA and NC possess nucleic acid binding properties. MA interacts with NAs in vitro (46) and in cells (27,52) via its highly basic region domain. In particular, its interaction with host transfer RNAs in the cytosol might regulate Gag interaction with the PM (27). On the other hand, interactions of NC with gRNA are mainly driven by the two highly conserved ZFs (40,53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58). However, these ZFs do not seem to be functionally equivalent, the N-terminal ZF (ZF1) playing a more prominent role in gRNA selection and packaging (57). Indeed, mutations in ZF1 and the NC N-terminal domain led to the formation of particles with abnormal core morphology and affected proviral DNA synthesis (59,60). Besides, specific in vitro binding of NCp7 to the Psi was also found to be dependent on the ZF1 and flanking basic amino acid residues (61). However, the exact contribution of each ZF remains controversial because a recent in vitro study showed that the distal C-terminal ZF (ZF2) would drive the first steps of association with NAs because of its larger accessibility compared to ZF1, which would contribute to stabilize the resulting complex (62).

Here, to decipher the role of the two ZFs in the cellular trafficking of Gag-gRNA complexes to the PM, we combined several quantitative approaches, including confocal microscopy, time-lapse microscopy, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM), and raster image correlation spectroscopy (RICS). To this aim, the MS2 bacteriophage coat protein was fused to eGFP to fluorescently label the gRNA (Fig. 1 A), whereas Gag proteins were fused to the fluorescent protein probe mCherry (mCH) (Fig. 1 B). This allowed us to compare in the cytoplasm and at the PM the interactions of gRNA with wild-type (WT) Gag and Gag mutants carrying deletions in NC ZFs and a nonmyristoylated version of Gag (GagG2A) (Fig. 1 B). As expected, the GagG2A mutation prevented colocalization of Gag with the gRNA at the PM but did not impair its gRNA binding. Importantly, we found that the simultaneous deletion of the two ZFs completely abolishes the Gag-gRNA interactions in the cytosol and at the PM. Either ZF was found to be sufficient to efficiently promote Gag-gRNA interactions in the cytoplasm, hence displaying redundant roles in this respect. Interestingly, ZF2 played a more prominent role than ZF1 in the relocation of these ribonucleoprotein complexes at the PM. Taken together, we show here that the intracellular HIV-1 gRNA recognition and Gag-gRNA trafficking to the PM are governed by ZF motifs within the NC domain.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids DNA

The constructs for Gag and Gag-mCH were previously described (44,63). The plasmid encoding human codon-optimized Gag was kindly provided by David E. Ott (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD). The deletion mutants (GagΔNC, GagΔZF1, GagΔZF2, and GagΔZF1-2) and the substitution mutant (GagG2A) were constructed by PCR-based mutagenesis on Gag and Gag-mCH following the supplier’s protocol (Stratagene, San Diego, CA). In addition, the pIntro plasmid was obtained from E. Bertrand (The Institute of Molecular Genetics of Montpellier, Montpellier, France (30)) and modified by EPIGEX (Strasbourg, France (pcDNA3.1 plasmid; CMV promotor)). Then, a TAG codon was introduced in the plasmid to stop the expression of peroxisome localization signal (eCFP-SKL) using Phusion site-directed mutagenesis kit (F-541; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and a set of primers (FW: 5′-GATATGGTGAGCTAGGGCGAGGAGCTG-3′ and Rev: 5′-GATACCGTCGAGATCCGTTCACTAATCG-3′). The plasmid pPOM21-mCH was obtained from Euroscarf (Oberursel, Germany) (64), whereas pRSV-Rev was obtained from Addgene (Watertown, MA) (plasmid # 12253). The integrity of all plasmids was assessed by DNA sequencing (GATC Eurofins Genomics, Konstanz, Germany).

Cell culture and plasmid transfection

HeLa cells stably expressing homogenous levels of MS2-GFP with a nuclear localization signal (NLS) (so called MS2-GFP) were obtained from Nolwenn Jouvenet (Institute Pasteur, Paris, France) (23) and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (11880-028; Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland), 1% antibiotic solution (penicillin streptomycin; Gibco, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and glutamine at 37°C in humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

To study the interaction between gRNA and Gag in cellula, MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were seeded onto a coverglass in 12-well plates (see confocal and super-resolution experiments) or onto an ibidi chambered coverglass (see FRET-FLIM experiments) at the density of 7.5 × 104 cells/mL/well or 1.5 × 105 cells/mL/well, respectively, 24 h before transfection. MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were then transfected using jetPRIME (Life Technologies) with a mixture of plasmids encoding for pIntro, Rev, unlabeled Gag, and Gag-mCH proteins at the following ratios depending on the material used: 12 well plate, 1; or 0.25; and 0.2 μg in IBIDI chamber, 1.6, 0.4, or 0.1 μg.

Immunolabeling

The MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were fixed 24 h post-transfection with 1.5–4% of paraformaldehyde (PFA)/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min and then rinsed three times for 5 min with PBS. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked in 3% (W/V) bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h, and subsequently incubated for 1 h at room temperature with rabbit polyclonal antibody directed against RNA polymerase II phosphoS2 (ab5095; Abcam, Cambridge, U.K.), followed by an incubation with fluorescent Alexa Fluor 568 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (A11011; Thermo Fisher Scientific). For nuclear staining, the medium was replaced by Hoechst 33258 (5 μg/mL; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) in PBS, and cells were incubated for 10 min. Coverslips were then washed and mounted on microscope slides with Fluoromount-G (00-4958-02; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were acquired with a Leica TCS SPE II confocal microscope equipped with a 63× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective (HCX PL APO 63×/1.40 OIL CS) and 405, 488, and 561 nm laser diodes.

Confocal microscopy

Fluorescence confocal images of tagged Gag proteins in fixed cells in the presence or absence of MS2-eGFP were taken 24 h post-transfection using a Leica SPE microscope equipped with a 63× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective (HCX PL APO 63×/1.40 OIL CS). The eGFP images were obtained by scanning the cells with a 488 nm laser line and using a 500–555 nm emission bandwidth. For the mCH images, a 561 nm laser line was used with a 570-625 nm bandwidth filter. To quantify the phenotypes, we first analyzed Gag proteins localized at the membrane (Red channel) and then checked if MS2-eGFP-labeled RNA localized at the membrane or in the cytoplasm (Green channel). We assessed 100 cells per experiment, and three independent experiments were performed.

FLIM

The experimental setup for FLIM measurements was previously described (44). Briefly, time-correlated single photon counting FLIM measurements were performed on a home-made two-photon excitation scanning microscope based on an Olympus IX70 inverted microscope with an Olympus 60× 1.2 NA water immersion objective operating in the scanned fluorescence collection mode. Two-photon excitation at 900 nm was provided by an InSight DeepSee Laser (Spectra-Physics, Santa Clara, CA). Photons were collected using a short pass filter with a cutoff wavelength of 680 nm (F75-680; AHF analysentechnik, Tübingen, Germany) and a band-pass filter of 520 ± 17 nm (F37-520; AHF analysentechnik). The fluorescence was directed to a fiber-coupled Avalanche photodiodes (SPCM-AQR-14-FC; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA), which was connected to a time-correlated single photon counting module (SPC830; Becker & Hickl, Berlin, Germany).

The time-resolved decays were analyzed using a one-component model pixel per pixel to obtain the fluorescence lifetime distribution all over the cell. Numerical values were converted into an arbitrary color scale, producing an image ranging from blue (presence of FRET) to yellow (absence of FRET).

For Förster Resonant Energy Transfer (FRET) experiments, the FRET efficiency (E) was calculated according to the equation:

| (1) |

where τDA and τD are the lifetime of the donor in the presence and in the absence of the acceptor.

To observe gRNA-Gag interactions in live cells, the seeded cells (on IBIDI chamber) were transfected as described above and washed once with PBS. A freshly prepared Leibovitz’s L15 Medium (21083-027; Gibco) with fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added before observation.

DNA plasmid microinjection and time-lapse microscopy

For time-lapse experiments, subconfluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells plated on glass coverslips (in a 12-well plate at 1.5 × 105 cells/mL the day before the experiment) were mounted in a Ludin Chamber (Life Imaging Services, Basel, Switzerland) following the protocol described in (44). The cells were then placed on a Leica DMIRE2 microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C with 5% CO2 (Life Imaging Services). A mixture of plasmids (72% pIntro, 17% Rev, 5.5% Gag, and 5.5% mCH-Gag or Gag mutants in the NC domain) were microinjected into the nucleus at 0.1 μg/μL with a fluorescent microinjection reporter solution (0.5 μg/μL rhodamine dextran; Invitrogen), using a Femtojet/InjectMan NI 2 microinjector (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized using a Märzhäuser (Wetzlar, Germany) automated stage piloted by the Leica FW4000 software. Images were then acquired with a 100× HCX PL APO (1.4 NA) objective every 5 min during 2–4 h using a Leica DC350FX CCD camera controlled by the FW4000 software. Time-lapse videos were then analyzed using the MetaMorph (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) software to determine at which time the GFP signal appears at the PM (fluorescently labeled gRNA) as well as when Gag multimers appear at the PM.

RICS

MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were transfected with specific plasmids (in IBIDI chamber) as described above, and living cells were imaged at 16 h post-transfection. RICS measurements were performed on a Leica SPE microscope equipped with a 63× oil immersion objective (HCX PL APO 63×/1.40 OIL CS; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). eGFP and mCH were excited with 488 nm and 561 nm laser lines, respectively. The emitted fluorescence was detected by a photo multiplier (PMT) with a detection window of 500–550 nm and 590–700 nm for eGFP and mCH, respectively. For each RICS measurement, a stack of 50 images (256 × 256 pixels with a pixel size of 50 nm) was acquired at 400 Hz (2.5 ms between the lines with a pixel dwell time of 2.8 μs). The RICS analysis was then performed using the SimFCS software developed by the Laboratory of Fluorescence Dynamics (http://www.lfd.uci.edu) or alternatively by a package of plugins running under ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). In the latter case, the used tools were an extension and improvement of the Stowers ICS Plugins developed by Jay Unruh (http://research.stowers.org/imagejplugins/ics_plugins.html), allowing us to generate RICS maps over several acquisitions in a fully automated and optimized way.

Before the autocorrelation of the image, the contribution of the slowly moving structures and cellular displacements were removed by subtracting the moving average. Then, the correlations of all frames were calculated, and the final averaged autocorrelation surface was fitted with the RICS correlation function given by

| (2) |

where G(x,y) represents the temporal correlation resulting from the diffusion of the fluorescent molecules, and S(x, y) takes into account the effect of beam displacement in the x and y directions. These two terms are defined as follows:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where x and y are the spatial lags in pixels, and δx and δy are the pixel size (50 nm). τP and τL are the pixel dwell time (2.8 μs) and the interline time (2.5 ms), respectively. w0 is the beam waist, and wz represents the z axis beam radius and is set to 3w0. γ is a shape factor due to uneven illumination across the focal volume and is 0.3535 for a three-dimensional (3D) Gaussian beam. N and D are the floating parameters that represent the number of fluorescent molecules in the focal volume and the diffusion coefficient, respectively. The waist of the beam w0 was measured before each experiment using 100 nM solutions of eGFP and mCH in water, assuming their diffusion coefficients are 90 μm2/s (65,66). Finally, the diffusion maps were obtained by calculating for each pixel of the image the average diffusion coefficient in a surrounding area of 64 × 64 pixels (10.24 μm2). In the resulting diffusion maps, the pixels are color coded by the average D value in the surrounding area.

Results

Fluorescent labeling of HIV-1 gRNA and Gag proteins in cells

We transfected a stable HeLa cell line expressing MS2 fused to eGFP (here called HeLa MS2-eGFP) (23) with a plasmid encoding a modified HIV-1 gRNA (pIntro) containing a cassette of 12 MS2 SLs recognized by the MS2-eGFP protein (Fig. 1, A1 and A3). Of note, in our system, the eGFP contains a NLS that directs MS2-eGFP toward the nuclei and nucleoli (Fig. 1 A2). To fluorescently label Gag proteins, we fused the mCH probe upstream of the CA domain to minimize the impact of the tag on protein activities (Fig. 1 B; (44,63)).

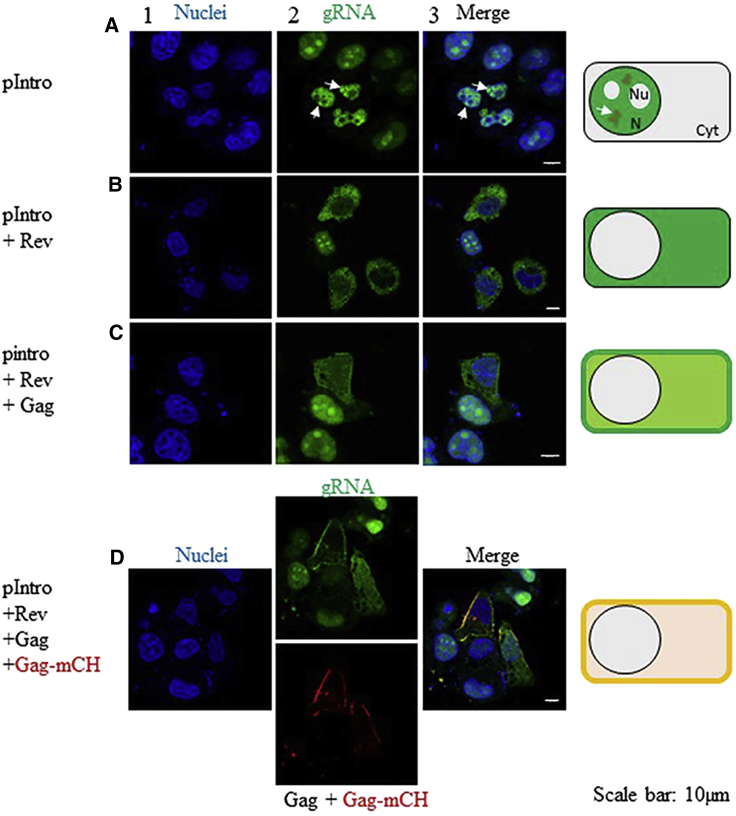

At first, we transfected the HeLa MS2-eGFP cells with the plasmids mentioned above and imaged them 24 h later. In cells transfected with pIntro, the phenotype observed was characterized with nonfluorescent nucleoli in contrast to nontransfected cells in which fluorescence was mainly concentrated at those sites (Figs. 1 A and 2 A). Moreover, by using immunofluorescence with an antibody directed against the RNA polymerase II phosphoS2 (Fig. S1), we observed that the bright green clusters in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 2 A, white arrows) corresponded to active transcription sites. In a further step, the cotransfection of pIntro with a Rev-encoding plasmid ensured the complete export of the MS2-eGFP-labeled gRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm because of the specific recognition of the Rev response element (RRE) sequence by Rev (Fig. 2 B). Finally, when unlabeled Gag was expressed alone (Fig. 2 C) or together with Gag-mCH (Fig. 2 D), the gRNA was relocalized to the PM. These observations indicated that the MS2-eGFP-based strategy is well suited to investigate the interactions between HIV-1 gRNA and Gag proteins by fluorescence-based techniques.

Figure 2.

Membrane relocalization of HIV-1-gRNA by Gag. (A) HeLa cells stably expressing MS2-eGFP were transfected with a construct encoding pIntro (see Materials and Methods). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst33258 (blue channel, column 1). Nontransfected cells showed GFP signal in the nuclei and nucleoli, whereas in cells transfected with pIntro, the MS2-eGFP fluorescence signal was only localized in the nuclei but no more in the nucleoli (green channel, column 2). The merge is in column 3. (B) The cells were then transfected with a plasmid encoding for Rev. This cotransfection ensured the complete export of the MS2-eGFP-labeled gRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm because of the specific recognition of the RRE. When Gag alone (C) or in mixture with Gag-mCH (D) was coexpressed, gRNA was relocalized to the PM. Confocal microscopy was performed 24 h post-transfection. Cartoons on the right illustrate the observed localizations of MS2-eGFP-RNA. Cyt, cytoplasm; N, nucleus; NU, nucleolus. To see this figure in color, go online.

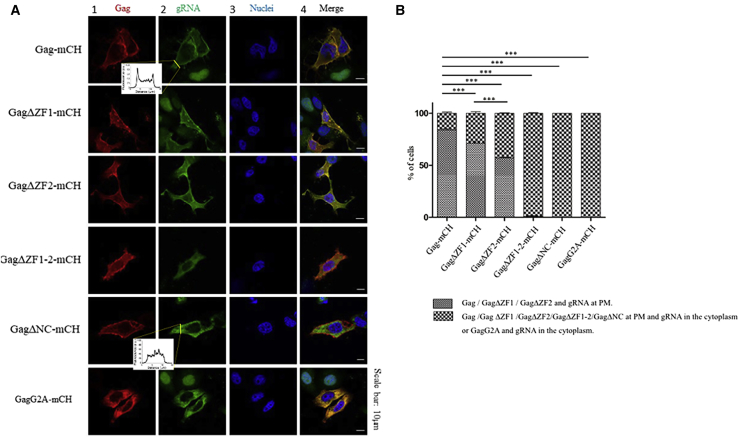

At least one ZF of Gag is required for gRNA enrichment at the PM

To investigate the impact of mutations in the NC domain of Gag on the cellular localization of gRNA, we used a Gag mutant in which the complete NC domain was deleted (GagΔNC) as well as Gag mutants carrying either a single (GagΔZF1 or GagΔZF2) or a double ZF deletion (ΔZF1-2) (Fig. 1 B). We also included a nonmyristoylated Gag protein in which the Gly at position 2 was substituted with an Ala residue (GagG2A), thus preventing the addition of a myristate group (Fig. 1 B). Globally, we observed 24 h post-transfection by confocal microscopy that all tested Gag proteins displayed a PM localization (Fig. 3 A, column 1), with the exception of the GagG2A mutant, which was found exclusively in the cytoplasm, as expected (Fig. 3 A, column 1; (67)). The intensity of MS2-eGFP-gRNA fluorescence was measured at PM and in the cytosol (Fig. 3 A, insets). In the case of Gag-mCH, we observed an accumulation of MS2-eGFP-gRNA at PM because the fluorescence at that site resulted to be two to three higher than in the cytoplasm. Conversely, in the presence of GagΔNC-mCH, MS2-eGFP-gRNA fluorescence was not found to increase at PM, suggesting that in this case, gRNA accumulated in the cytoplasm.

Figure 3.

Confocal microscopy of MS2-eGFP HeLa cells coexpressing Gag-mCH proteins and gRNA. (A) The localization of Gag-mCH proteins (column 1, red channel) and MS2-eGFP-gRNA (column 2, green channel) as well as the staining with Hoechst33258 as a fluorescent marker for the nucleus (column 3, blue channel) and the merge of these images (column 4) are shown. Each panel indicates the major observed phenotype. Fluorescence intensity of MS2-eGFP-gRNA was measured over 15 μm, including the PM and cytosol (yellow line), and the corresponding distributions are indicated in the insets. (B) Histograms show the percentage of cells in which gRNA was found to diffuse in the cytoplasm (large dots) or, alternatively, was localized at the PM (small dots) in the presence of the different Gag-mCH proteins. Cells were imaged 24 h post-transfection by confocal microscopy. We counted 100 cells per condition. The analysis was performed on four independent experiments, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistics was obtained with a χ2 test and revealed a significant difference (∗∗∗p < 0.001). Scale bar, 10 μm is indicated. To see this figure in color, go online.

In a further step, a careful quantification (see Materials and Methods) showed that WT Gag and gRNA colocalized at the PM in 84 ± 3% of cells, whereas this percentage dropped to 71 ± 3 and 57 ± 1% for GagΔZF1 and GagΔZF2, respectively (Fig. 3, A and B). Interestingly, in the presence of GagΔZF1-2 or GagΔNC, no colocalization of the proteins with gRNA was observed at the PM, and in these cases, gRNA was found to accumulate in the cytoplasm (Fig. 3, A and B). Altogether, these experiments show that the two ZFs of the NC domain of Gag are required for an optimal trafficking of gRNA to the PM. However, the presence of one ZF is sufficient to partially relocate gRNA from the cytoplasm to the PM.

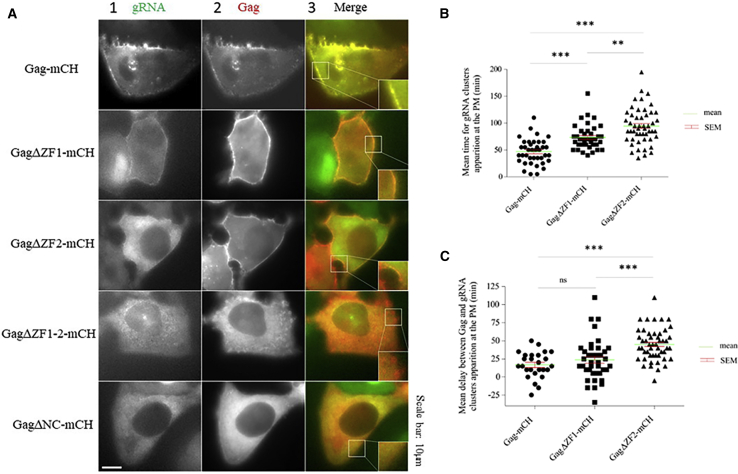

Real-time kinetics of gRNA coaccumulation with Gag at the PM

Next, we performed two-color time-lapse microscopy experiments to monitor in real time the events taking place between gRNA transcription and its localization at the PM in living cells. To this aim, HeLa MS2-eGFP-expressing cells were microinjected with a combination of plasmids expressing gRNA, Gag, and Rev and imaged every 5 min for 4 h. About 5 min after microinjection, the MS2-eGFP fluorescence accumulated as clusters in the nucleoplasm corresponding to active transcription sites (Fig. S1), although the nucleoli appeared nonfluorescent (Video S1). When the viral Rev factor was expressed, the MS2-eGFP-labeled gRNA was then found to accumulate at the nuclear envelope and to colocalize with the nuclear envelope marker POM121-mCH (Fig. S1 B; Video S1). The Rev-driven export of gRNA was subsequently observed through the green fluorescence signal accumulating in the cytoplasm. About 1 h after microinjection, Gag-mCH appeared in the cytoplasm, and we evaluated the average delay between the appearance of the Gag-mCH proteins in the cytoplasm and the appearance of the first MS2-eGFP clusters labeled gRNAs at the PM (Fig. 4, A and B). In agreement with the conclusions of the previous paragraph, we observed that the enrichment of the MS2-eGFP-labeled gRNA at the PM after 4 h was observable for less than 7% of cells expressing GagΔZF1-2 (Video S2) or GagΔNC (Video S3). For cells expressing GagΔZF1(Video S4) and GagΔZF2 (Video S5), we noticed gRNA accumulation to the PM but with a significant delay as compared to WT Gag proteins. Indeed, whereas gRNA accumulated at the PM within 47 ± 4 min (n = 39) in the presence of WT Gag, it took ∼73.5 ± 4 min (n = 39) and 94.5 ± 5 min (n = 50) in the case of GagΔZF1 and GagΔZF2, respectively (Fig. 4 B). In a further step, we monitored the mean delay between Gag-mCHclusters appearance at the PM and the accumulation of MS2-eGFP-labeled gRNAs at the same sites. Similarly, to our previous observation, GagΔZF2 showed a significantly increased delay 45 ± 3 min (n = 50) compared with WT Gag 17 ± 3 min (n = 26) or to GagΔZF1 23.5 ± 5 min (n = 39) (Fig. 4 C). These results suggest that deletion of the ZF motifs in Gag introduces a delay in the colocalization of gRNA at the PM and that the deletion of ZF2 was found to have a greater effect than ZF1 in the delayed gRNA accumulation at the PM.

Figure 4.

Kinetic analysis of gRNA localization at the PM induced by Gag proteins. (A) Shown is time-lapse microscopy on cells microinjected with a combination of plasmids expressing MS2-eGFP-gRNA (column 1, green channel), Gag-mCH (column 2, red channel), and Rev and imaged every 5 min for 4 h. In the merge colum 3, the insets correspond to a zoom of the PM region. Scale bar, 10 μm is indicated. (B) Shown is the quantification of the average delay separating the appearance of Gag-mCH (rounds), GagΔZF1-mCH, (squares), and GagΔZF2 (triangles) proteins in the cytoplasm and the detection of the first MS2-eGFP-gRNA clusters accumulating at the PM. (C) Shown is the quantification of the average delay separating the detection of Gag-mCH (rounds), GagΔZF1-mCH (squares), GagΔZF2 (triangles), and MS2-eGFP-gRNA clusters at the PM. Individual data points, corresponding mean values, and SEM are indicated. The statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA associated to Tukey’s multiple comparison tests and revealed significant differences (∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001) between Gag, GagΔZF1, and GagΔZF2 (26–50 cells analyzed per experiment). To see this figure in color, go online.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev, and Gag and Gag-mCH were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. Gag-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔZF1-2-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔZF1-2 were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔZF1-2-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔNC-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔNC were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔNC-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔZF1-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔZF1 were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔZF1-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔZF2-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔZF2 were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔZF2-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

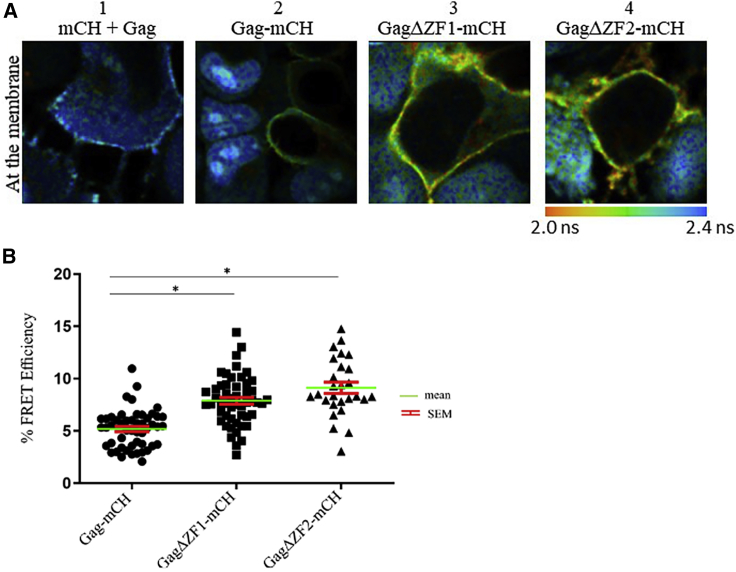

Monitoring the interactions between Gag proteins and gRNA at the PM

To further demonstrate the direct interaction between Gag and gRNA at the PM, we performed FRET-FLIM. FRET occurs when the FRET donor (eGFP linked to MS2) and acceptor (mCH bound to Gag) are less than 10 nm apart. The FLIM technique is based on the analysis of the donor lifetime at each pixel of the image. When FRET occurs, the donor lifetime decreases. Of note, the lifetime is independent of the local concentration of fluorophores and the instrumental setup. Typically, FLIM images are built up using a false color scale covering the range of donor lifetimes from 2 ns (red) to 2.4 ns (blue). This allows a direct description of each pixel in terms of FRET efficiency and thus provides information on the spatial distribution and proximity of the probes.

About 24 h after transfection of MS2-eGFP HeLa cells, the lifetime value of MS2-eGFP-gRNA in the presence of unlabeled Gag and free mCH was found to be similar to the lifetime of MS2-eGFP in the nuclei of nontransfected cells (∼2.3 ns). This analysis reflected the absence of FRET between the probes at PM under these conditions and indicated that the fluorescence lifetime of MS2-eGFP is not influenced by its binding to gRNA (Fig. 5 A1). In the presence of Gag-mCH proteins, we observed a decrease of the lifetime of the MS2-eGFP-gRNA complexes at the PM (Fig. 5 A2), demonstrating that FRET occurs between Gag and gRNA at those sites. According to Eq. 1 (see Materials and Methods), the corresponding value for FRET efficiency was 5 ± 0.5%. (Fig. 5 B). In cells transfected with the mCH-labeled GagΔZF1 or GagΔZF2, FRET efficiency was ∼8 ± 1 and 9 ± 2%, respectively (Fig. 5, A3, A4, and B). It is possible that the deletion of either ZF could modify the conformation of the protein or its binding mode to the gRNA. This could affect the orientation of the probes, which can impact FRET efficiency and result in unexpectedly higher values for GagΔZF1 or GagΔZF2 compared to the one obtained for WT Gag. On the other hand, FLIM-FRET analysis confirmed that Gag proteins and gRNA interact at PM, and the deletion of one ZF does not affect the interaction of Gag with gRNA at these sites.

Figure 5.

FRET-FLIM analysis of the interaction between gRNA and Gag at the PM. (A) MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were transfected with a combination of plasmids, and FLIM analysis in the cytoplasm was carried out 24 h post-transfection. The fluorescence lifetime of MS2-eGFP-gRNA was determined by using a single exponential model and was color coded, ranging from red (2.0 ns) to blue (2.4 ns). Shown are FLIM images of gRNA in the presence of unlabeled Gag and free mCH (1), Gag-mCH (2), GagΔZF1-mCH (3), or GagΔZF2-mCH (4). (B) Shown are corresponding plots representing FRET efficiencies for Gag-mCH (circles), GagΔZF1-mCH (squares), and GagΔZF2-mCH (triangles). We performed three independent experiments on at least 30 cells. Above the threshold value (5%), FRET efficiencies can be considered as corresponding to a direct interaction between fluorescently labeled gRNA and Gag proteins. (44) FRET efficiency values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods (Eq. 1). Individual data points, corresponding mean values, and SEM are indicated. The statistical analysis was realized by a Student’s t-test with significant differences represented by ∗p < 0.05. All images were acquired using a 50 × 50 μm scale and 128 pixels × 128 pixels. To see this figure in color, go online.

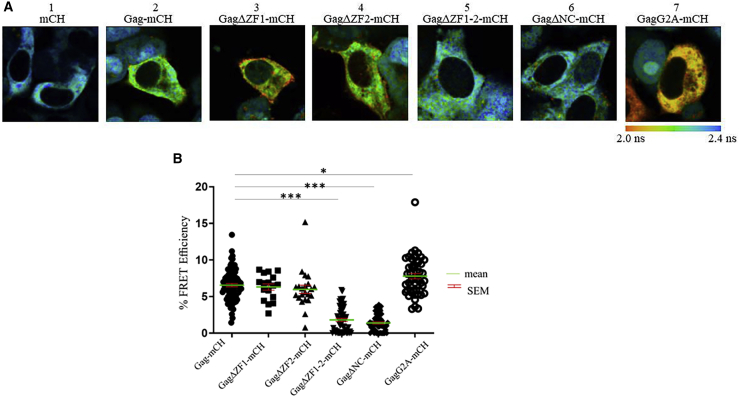

Monitoring the interaction between Gag proteins and gRNA in the cytoplasm

We then investigated the interaction between Gag and gRNA in the cytoplasm. We imaged by FRET-FLIM the cells 16 h after transfection when large quantities of Gag proteins are still present in the cytoplasm. Interestingly, the expression of Gag-, GagΔZF1-, and GagΔZF2-mCH proteins led to a decrease of MS2-eGFP/gRNA (the donor) lifetime in the cytoplasm as can be seen from the color change from blue (Fig. 6 A1) to green (Fig. 6 A2–A4). The corresponding FRET efficiency values were of 6.6 ± 0.8, 6.3 ± 0.2, and 6.4 ± 1%, respectively, indicating that these proteins interact with the gRNA in the cytosol. In contrast, FRET efficiencies for GagΔZF1-2-mCH and GagΔNC-mCH were only 1.3 ± 0.9 and 1.6 ± 1%, respectively, suggesting that one ZF motif is necessary and sufficient for the interaction between Gag and gRNA in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6 A5 and A6). Finally, the nonmyristoylated Gag mutant (GagG2A-mCH) was also found to interact with gRNA in the cytoplasm, with a FRET efficiency of 7.8 ± 0.1% (Fig. 6 A7), indicating that myristoylation is not necessary for Gag-gRNA interaction in the cytosol.

Figure 6.

FRET-FLIM analysis of the interaction between gRNA and Gag in the cytoplasm. (A) MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were transfected with our combination of plasmids, and FLIM analysis in the cytoplasm was carried out 16 h post-transfection. The fluorescence lifetime of MS2-eGFP was determined by using a single exponential model and was color coded, ranging from red (2.0 ns) to blue (2.4 ns). Shown are FLIM images of gRNA in the presence of unlabeled Gag and free mCH (1), Gag-mCH (2), GagΔZF1-mCH (3), GagΔZF2-mCH (4), GagΔZF1-2-mCH (5), GagΔNC-mCH (6), or GagG2A-mCH (7). (B) The corresponding plots represent FRET efficiencies for Gag-mCH (filled circles), GagΔZF1-mCH (squares), GagΔZF2-mCH (upward triangles), GagΔZF1-2-mCH (downward triangles), GagΔNC-mCH (diamonds), or GagG2A-mCH (empty circles). Individual data points, corresponding mean values, and SEM of three independent experiments on at least 30 cells are indicated. Above the threshold value (5%), FRET efficiencies can be considered as corresponding to a direct interaction between fluorescently labeled gRNA and Gag proteins (44). The statistical analysis was realized by a Student’s t-test with significant differences represented by ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. All images were acquired using a 50 × 50 μm scale and 128 × 128 pixels. To see this figure in color, go online.

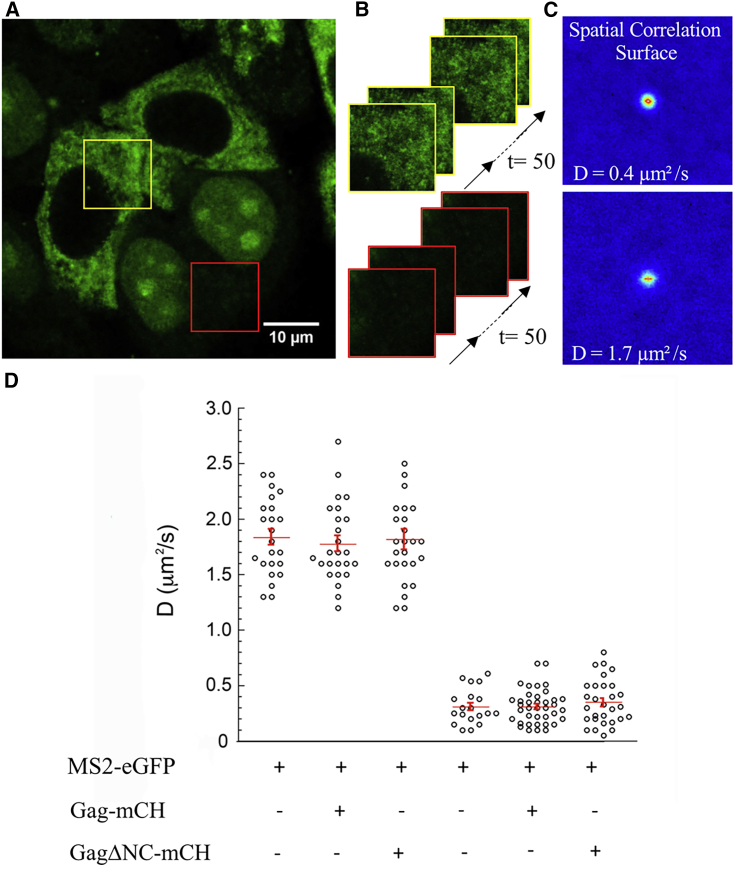

Next, the cytoplasmic diffusion of Gag and gRNA was investigated by RICS (65,68,69). This method is based on the analysis of the fluorescence intensity fluctuations between neighboring pixels by spatially autocorrelating the image in x and y directions. The resulting spatial correlation surface (SCS) is fitted with a 3D diffusion model to obtain the value of the diffusion coefficient (D) of the macromolecules in the scanned area. In a first experiment, we measured the cytoplasmic diffusion of MS2-eGFP. Stacks of 50 images were recorded in the cytoplasm of living cells (Fig. 7 A, red frame, and Fig. 7 B), and the mean SCS were calculated (Fig. 7 C). As a result of the presence of the NLS sequence, the majority of the MS2-eGFP molecules were located in the nucleus, (Fig. 7 A) even though a fraction of the MS2-eGFP molecules (∼25–30% based on RICS and intensity fluorescence measurements) was found to diffuse in the cytoplasm. The average diffusion coefficient of the cytoplasmic MS2-eGFP molecules was 1.8 μm2/s (Fig. 7 D, white bar), which is not consistent with the theoretical estimation based on the size of MS2-eGFP construct. Indeed, the hydrodynamic radius (Rh) of the MS2-eGFP protein rMS2-eGFP (calculated as described in (70)) is 3.35 nm, and this value is 1.12-fold larger than the Rh of eGFP alone (reGFP = 2.8 nm (71)). Because the diffusion coefficient is inversely proportional to the radius of the diffusing molecule, a D value of 16.7 μm2/s for the free MS2-eGFP is expected from the ratio of the reGFP/rMS2-eGFP and the previously determined DeGFP value (∼20 μm2/s (72)). The comparison between the expected and experimental D values strongly suggests that MS2 protein may bind to cellular factors, likely cellular RNAs in the cytoplasm. Besides, in the absence of pIntro, the expression of Gag-mCH or GagΔNC-mCH did not affect the diffusion of MS2-eGFP (Fig. 7 D). In contrast, the expression of pIntro and Rev led to a strong decrease in the D value, likely as the result of the binding of MS2-eGFP to viral gRNA and its subsequent relocation from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Fig. 7 A, yellow frame). The mean value of D for MS2-eGFP bound to gRNA was ∼0.3 μm2/s, in line with previous analysis on HIV-1 RNA diffusion by tracking assays (73). Furthermore, the interaction with Gag-mCH or GagΔNC-mCH proteins did not significantly affect the diffusion of HIV-1 gRNA, which is consistent with the binding of a limited number of Gag copies to gRNA (27).

Figure 7.

RICS analysis of MS2-eGFP diffusion in the cytoplasm. (A) Shown are confocal images of MS2-eGFP expressing cells transfected with plasmids expressing pIntro and Rev. For the RICS measurements, stacks of 50 images were recorded in the cytoplasm (B), and the average spatial correlation surfaces (SCS) were then calculated (C) and fitted with a 3D free diffusion model. (D) Shown are diffusion coefficient values of MS2-eGFP in cells expressing or not expressing pIntro and Rev, Gag-mCH, and GagΔNC-mCH. The presence of pIntro and Rev (right panel) induces a drastic decrease of the MS2-eGFP diffusion coefficient (left panel). For each condition, individual data points, corresponding mean values, and SEM of 50–60 measurements of three independent experiments (15–20 cells analyzed per experiment) are indicated. The statistical analysis was realized by a Student’s t-test with significant differences represented by ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. To see this figure in color, go online.

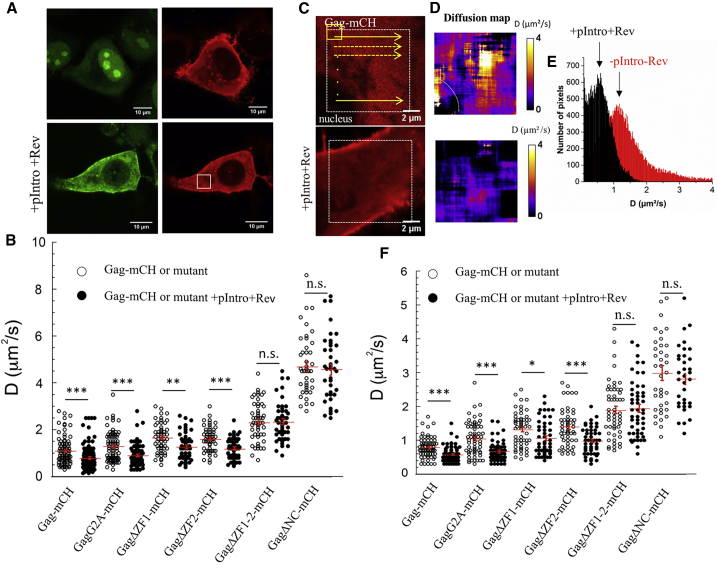

In a next step, we monitored by RICS the cytoplasmic diffusion of Gag-mCH. Because the size of Gag is significantly smaller than the size of gRNA, the association of Gag proteins with gRNA should produce a large decrease in the value of their diffusion coefficient. The measurements were performed in a cytoplasmic volume in the midplane of the cell (Fig. 8 A). The focal planes of the acquisition were chosen carefully to minimize possible artifacts due to Gag-mCH molecules bound to the PM. The mean D value for Gag in the absence of gRNA was 1.1 ± 0.6 μm2/s (Fig. 8 B), in reasonable agreement with previous reported D values of 2.4 ± 0.5 μm2/s (74,75). On the other hand, these values are considerably smaller than the theoretical value (13.8 μm2/s) calculated assuming that the molecular weight of Gag-mCH is ∼82 kDa and using an empirical formula relating the molecular weight to the Rh (70). Besides, our measured D value for the cytoplasmic diffusion of eGFP trimers (10.4 ± 2.1 μm2/s) is in good agreement with a previous estimation (9.5 μm2/s (74)). Importantly, eGFP trimers have also approximately the same size as Gag-mCH and are not supposed to bind to any cellular components (44,76,77). Moreover, previous ex vivo analysis also revealed that the cytosolic Gag proteins are likely not a monomer and possibly bind to larger cytosolic complexes (74,75). Accordingly, all these results suggested that the discrepancy between our theoretical and experimental values of Gag-mCH could be due to Gag-mCH capacity to multimerize as low order multimers, as previously suggested (26,27), and/or to interact with cellular factors (74,75).

Figure 8.

RICS analysis of Gag-mCH diffusion in the cytoplasm. (A) Shown are confocal images of MS2-eGFP and Gag-mCH expressing cells in the absence (top panels) and the presence (bottom panels) of pIntro and Rev. MS2-eGFP-gRNA was observed in the cell cytoplasm (green channel), and the RICS measurements were performed on the labeled Gag proteins in the red channel. (B) Shown are diffusion coefficient values of Gag proteins in the presence and the absence of pIntro and Rev. (C) Shown are confocal images and (D) corresponding diffusion maps of Gag-mCH in the absence (top panels) and the presence (bottom panels) of pIntro and Rev. (E) Shown is a histogram representation of the D values of the diffusion maps. The arrows show the positions of the most frequent D values, called Dmax. (F) Dmax values of Gag proteins in the presence and absence of pIntro and Rev are shown. In (B) and (D), the measured values, the mean values, and the corresponding SEM of 50–60 measurements in three independent experiments (15–20 cells analyzed per experiment) are indicated. The statistical analysis was realized by a Student’s t-test with significant differences represented by ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, and ∗∗∗p < 0.001. To see this figure in color, go online.

In line with a previous study (77), mutations affecting the myristoylation site do not affect Gag mobility (DGagG2A = 1.3 ± 0.6 μm2/s). Interestingly, D values of 1.7 ± 0.6 and 1.6 ± 0.5 μm2/s were obtained for GagΔZF1 and GagΔZF2, respectively, whereas deletion of the two ZFs or the complete NC domain resulted in increased D values of 2.3 ± 0.9 and 4.7 ± 1 μm2/s. These high D values (77) are likely related to the inability of GagΔZF1-2 and GagΔNC to multimerize and bind to cellular RNAs and proteins (44,76). We then performed the same analysis in cells expressing HIV-1 gRNA. The diffusion coefficients of Gag-mCH, GagG2A, GagΔZF1, and GagΔZF2 proteins decreased significantly (∼25–30%) in the presence of gRNA (Fig. 8 B), whereas no effect was observed for GagΔNC and GagΔZF1-2 mutants.

To further strengthen our analysis, we mapped the diffusion coefficients of the Gag proteins in a larger part of the cell. To this aim, a window of 64 × 64 pixels was shifted pixel by pixel along the images, and an average D value was calculated for each position (Fig. 8 C). A diffusion map was then generated by representing the D values obtained in each pixel. Examples of diffusion maps of Gag-mCH proteins in the presence and absence of gRNA are shown in Fig. 8 D. The histogram of the diffusion maps (Fig. 8 E) revealed that the D values are highly variable and significantly decreased in the presence of gRNA. Comparison of the D values at the maximum of the histograms (Dmax) indicated that, in good agreement with our analysis (Fig. 8 B), the Dmax value decreased by 20–35% for Gag-, GagG2A-, GagΔZF1-, and GagΔZF2-mCH proteins, whereas the Dmax value remained constant for GagΔZF1-2- and GagΔNC-mCH mutants (Fig. 8 F). Thus, the RICS data confirmed that Gag, GagG2A, and Gag mutants carrying only one ZF deletion bind to the gRNA, whereas GagΔZF1-2 and GagΔNC mutants do not, in agreement with our FRET/FLIM conclusions (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Previous biochemical and genetic studies have extensively investigated in vitro the role of the two ZFs of NCp7 (56,57,59, 60, 61, 62,78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83). In this study, we combined several imaging techniques to obtain a clear picture of the role of both ZFs in the NC domain of Gag in the intracellular trafficking of HIV-1 gRNA to the PM assembly sites. Even though cellular Gag-gRNA interactions were already described (18,74), our analysis focused on the comparison of the gRNA interactions with WT Gag and Gag mutants in which either one or both ZFs were deleted. Our analysis evidenced that at least one ZF is required for an efficient interaction between Gag and gRNA in the cytoplasm and at the PM. Although the two ZFs seem to be redundant for this interaction, ZF2 played a more important role than ZF1 in the trafficking of the ribonucleoprotein complexes to the PM (Figs. 5, 6, and 8).

By performing real-time analysis in the presence of Gag, we found that gRNA accumulated at the PM within 46.7 ± 3.7 min in the presence of Gag (Fig. 4, A and B). This result is in good agreement with previous studies showing an accumulation of gRNA dimers at the PM during virus assembly in ∼30 min (3,21,25). On the other hand, the deletion of a single ZF delayed the gRNA accumulation at the assembly sites, as it took ∼73.5 ± 3.7 and 94.5 ± 4.7 min to accumulate gRNA at the PM in the case of GagΔZF1 and GagΔZF2, respectively (Fig. 4 B). Data from the literature showed that the NC domain and the C-terminal p6 domain in Gag are both involved in the budding cellular machinery because deletions of the NC domain or its two ZFs were found to interfere with virus release by impairing the recruitment of Tsg101 ESCRT-I proteins and their co-factors, such as ALIX (44,84,85). Moreover, it was reported that the deletion of the distal ZF2 led not only to an abnormal uptake of Tsg101 but also to biogenesis defects during virion formation (83). Here, we observed that the delay of GagΔZF1 or GagΔZF2 to reach the PM (Fig. 4) is another consequence of ZF deletion. However, further analysis would be necessary to establish if those effects are related.

In a further step, the nonequivalence of the two ZFs in viral RNA recruitment to the PM was confirmed by the mean delay observed between Gag-mCH appearance at the PM and the accumulation of MS2-eGFP-labeled gRNAs at the same sites (Fig. 4 C). Indeed, GagΔZF2 showed a significantly increased delay 45 ± 3 min compared to WT Gag 17 ± 3 min or to GagΔZF1 23.5 ± 5 min (Fig. 4 C), confirming that ZF2 has a greater impact than ZF1 in the recruitment of gRNA to the PM. Thus, even though the two ZFs displayed redundant roles in the cytoplasmic context, we observed that ZF2 played a more prominent role in the trafficking of the gRNA/Gag complexes to the assembly sites at the PM. The idea that the two ZFs do not seem to be functionally equivalents was also supported by recent in vitro data showing that in the NCp7 context, ZF2 would initiate the association with NAs, whereas ZF1 would play a role in the stabilization of the resulting complex (62).

Our RICS analysis in the cytoplasm further showed that Gag proteins did not affect the diffusion of HIV-1 gRNA (Fig. 8), likely because of the limited size increase of the gRNA upon the binding of a few Gag proteins. This is fully consistent with the notion that Gag multimerization could be initiated in the cytoplasm and then triggered by RNA binding (26,75,76,86, 87, 88) and with our previous in vitro data showing that a limited number of Gag proteins (i.e., about two trimers) bind to gRNA fragments (14). Deletion of the NC domain induced a significant increase in diffusion compared to WT Gag (4.7 ± 1 μm2/s vs 1.1 ± 0.6 μm2/s), in line with previous data on Gag mutants in which all basic residues of the NC domain were replaced by Ala residues (77). This increased diffusion could be explained by the impacted capacity of Gag to multimerize and to bind to cellular factors when its NC domain is deleted (44,76).

Our data also included the G2A mutant, in which the absence of myristate does not only abolish the anchorage of Gag at the PM but also impacts Gag oligomerization (76,89). In good agreement with the literature (77), our findings showed that mutations affecting myristoylation did not affect Gag mobility nor cytosolic binding to gRNA. This definitely supports the conclusion that the binding of HIV-1 Gag to viral RNA and to PM are independent events governed by different domains (Figs. 3 and 6). However, how MA and NC domains are employed by retroviral Gag to interact with RNA is retrovirus specific because previous observations on deltaretrovirus showed that HTLV-2 MA has a more robust chaperone function than HTLV-2 NC and contributes importantly to the gRNA packaging (90).

Altogether, our findings show for, to our knowledge, the first time that the two ZFs in the NC domain of the HIV-1 Gag precursor are equivalent for the interaction with the gRNA in the cytoplasm, and ZF2 has a more important role than ZF1 for the intracellular trafficking of the ribonucleoprotein complex to the PM. Our data thus contribute to the current understanding and knowledge of the determinants governing the HIV-1 gRNA cellular trafficking to the assembly sites at the PM.

Author Contributions

S.B. and H.d.R. designed the project. E.B., S.B., and H.d.R. managed the project and drafted the manuscript with some assistance from the other co-authors. J.-C.P., R.M., and Y.M. contributed to scientific discussions and to revise the manuscript. M.B.N., E.B., P.D., and J.B. characterized the interactions between fluorescently labeled gRNA and Gag (confocal, FRET-FLIM, and statistics). E.R. performed cloning. D.D., R.C., and E.B. microinjected and imaged the dynamics of the interactions. H.A. performed RICS experiments. H.A. and P.C. performed the analysis of RICS experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Romain Vauchelles for assistance at the PIQ platform and Julien Godet and Frédéric Przybilla for help in statistical analysis.

The Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les hépatites virales supported S.B., J.B., and H.d.R.

Editor: Susan Schroeder.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.05.035.

Contributor Information

Emmanuel Boutant, Email: emmanuel.boutant@unistra.fr.

Hugues de Rocquigny, Email: hderocquigny@univ-tours.fr.

Serena Bernacchi, Email: s.bernacchi@ibmc-cnrs.unistra.fr.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Finzi A., Orthwein A., Cohen E.A. Productive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly takes place at the plasma membrane. J. Virol. 2007;81:7476–7490. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00308-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jouvenet N., Neil S.J.D., Bieniasz P.D. Plasma membrane is the site of productive HIV-1 particle assembly. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivanchenko S., Godinez W.J., Lamb D.C. Dynamics of HIV-1 assembly and release. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000652. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lever A.M.L. HIV-1 RNA packaging. Adv. Pharmacol. 2007;55:1–32. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(07)55001-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuzembayeva M., Hayes M., Sugden B. Multiple functions are mediated by the miRNAs of Epstein-Barr virus. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2014;7:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mailler E., Bernacchi S., Smyth R.P. The life-cycle of the HIV-1 Gag-RNA complex. Viruses. 2016;8:248. doi: 10.3390/v8090248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comas-Garcia M., Davis S.R., Rein A. On the selective packaging of genomic RNA by HIV-1. Viruses. 2016;8:246. doi: 10.3390/v8090246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skripkin E., Paillart J.C., Ehresmann C. Identification of the primary site of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:4945–4949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.11.4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paillart J.C., Skripkin E., Marquet R. A loop-loop “kissing” complex is the essential part of the dimer linkage of genomic HIV-1 RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5572–5577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berkhout B., Ooms M., Verhoef K. In vitro evidence that the untranslated leader of the HIV-1 genome is an RNA checkpoint that regulates multiple functions through conformational changes. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:19967–19975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laughrea M., Jetté L., Wainberg M.A. Mutations in the kissing-loop hairpin of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reduce viral infectivity as well as genomic RNA packaging and dimerization. J. Virol. 1997;71:3397–3406. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3397-3406.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paillart J.C., Marquet R., Ehresmann C. Mutational analysis of the bipartite dimer linkage structure of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:27486–27493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abd El-Wahab E.W., Smyth R.P., Marquet R. Specific recognition of the HIV-1 genomic RNA by the Gag precursor. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4304. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernacchi S., Abd El-Wahab E.W., Paillart J.-C. HIV-1 Pr55Gag binds genomic and spliced RNAs with different affinity and stoichiometry. RNA Biol. 2017;14:90–103. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1256533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth R.P., Despons L., Marquet R. Mutational interference mapping experiment (MIME) for studying RNA structure and function. Nat. Methods. 2015;12:866–872. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clavel F., Orenstein J.M. A mutant of human immunodeficiency virus with reduced RNA packaging and abnormal particle morphology. J. Virol. 1990;64:5230–5234. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.5230-5234.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lever A., Gottlinger H., Sodroski J. Identification of a sequence required for efficient packaging of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA into virions. J. Virol. 1989;63:4085–4087. doi: 10.1128/jvi.63.9.4085-4087.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferrer M., Clerté C., Mougel M. Imaging HIV-1 RNA dimerization in cells by multicolor super-resolution and fluctuation microscopies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7922–7934. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore M.D., Nikolaitchik O.A., Hu W.-S. Probing the HIV-1 genomic RNA trafficking pathway and dimerization by genetic recombination and single virion analyses. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000627. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore M.D., Fu W., Hu W.-S. Suboptimal inhibition of protease activity in human immunodeficiency virus type 1: effects on virion morphogenesis and RNA maturation. Virology. 2008;379:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sardo L., Hatch S.C., Hu W.-S. Dynamics of HIV-1 RNA near the plasma membrane during virus assembly. J. Virol. 2015;89:10832–10840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01146-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dilley K.A., Nikolaitchik O.A., Hu W.-S. Interactions between HIV-1 Gag and viral RNA genome enhance virion assembly. J. Virol. 2017;91:e02319-16. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02319-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jouvenet N., Simon S.M., Bieniasz P.D. Imaging the interaction of HIV-1 genomes and Gag during assembly of individual viral particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:19114–19119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907364106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J., Rahman S.A., Hu W.-S. HIV-1 RNA genome dimerizes on the plasma membrane in the presence of Gag protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:E201–E208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518572113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jouvenet N., Bieniasz P.D., Simon S.M. Imaging the biogenesis of individual HIV-1 virions in live cells. Nature. 2008;454:236–240. doi: 10.1038/nature06998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kutluay S.B., Bieniasz P.D. Analysis of the initiating events in HIV-1 particle assembly and genome packaging. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kutluay S.B., Zang T., Bieniasz P.D. Global changes in the RNA binding specificity of HIV-1 gag regulate virion genesis. Cell. 2014;159:1096–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bieniasz P., Telesnitsky A. Multiple, switchable protein:RNA interactions regulate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 assembly. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2018;5:165–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-092917-043448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ferrer M., Henriet S., Mougel M. From cells to virus particles: quantitative methods to monitor RNA packaging. Viruses. 2016;8:239. doi: 10.3390/v8080239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Molle D., Segura-Morales C., Bertrand E. Endosomal trafficking of HIV-1 gag and genomic RNAs regulates viral egress. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:19727–19743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.019844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grigorov B., Arcanger F., Muriaux D. Assembly of infectious HIV-1 in human epithelial and T-lymphoblastic cell lines. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sherer N.M., Lehmann M.J., Mothes W. Visualization of retroviral replication in living cells reveals budding into multivesicular bodies. Traffic. 2003;4:785–801. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2003.00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nydegger S., Foti M., Thali M. HIV-1 egress is gated through late endosomal membranes. Traffic. 2003;4:902–910. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0854.2003.00145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lehmann M., Milev M.P., Mouland A.J. Intracellular transport of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomic RNA and viral production are dependent on dynein motor function and late endosome positioning. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:14572–14585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808531200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell N.M., Lever A.M.L. HIV Gag polyprotein: processing and early viral particle assembly. Trends Microbiol. 2013;21:136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vlach J., Saad J.S. Structural and molecular determinants of HIV-1 Gag binding to the plasma membrane. Front. Microbiol. 2015;6:232. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chukkapalli V., Ono A. Molecular determinants that regulate plasma membrane association of HIV-1 Gag. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;410:512–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inlora J., Collins D.R., Ono A. Membrane binding and subcellular localization of retroviral Gag proteins are differentially regulated by MA interactions with phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-bisphosphate and RNA. MBio. 2014;5:e02202–e02214. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02202-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin C., Mendoza-Espinosa P., Bruinsma R. Specific inter-domain interactions stabilize a compact HIV-1 Gag conformation. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aldovini A., Young R.A. Mutations of RNA and protein sequences involved in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 packaging result in production of noninfectious virus. J. Virol. 1990;64:1920–1926. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1920-1926.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rein A. Nucleic acid chaperone activity of retroviral Gag proteins. RNA Biol. 2010;7:700–705. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.6.13685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Webb J.A., Jones C.P., Musier-Forsyth K. Distinct binding interactions of HIV-1 Gag to Psi and non-Psi RNAs: implications for viral genomic RNA packaging. RNA. 2013;19:1078–1088. doi: 10.1261/rna.038869.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cimarelli A., Luban J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion density is not determined by nucleocapsid basic residues. J. Virol. 2000;74:6734–6740. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6734-6740.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Meshri S.E., Dujardin D., de Rocquigny H. Role of the nucleocapsid domain in HIV-1 Gag oligomerization and trafficking to the plasma membrane: a fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy investigation. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:1480–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Y., Qu N., Chen A.K. Roles of Gag-RNA interactions in HIV-1 virus assembly deciphered by single-molecule localization microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:6721–6726. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805728115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Olson E.D., Musier-Forsyth K. Retroviral Gag protein-RNA interactions: implications for specific genomic RNA packaging and virion assembly. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019;86:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godet J., Mély Y. Biophysical studies of the nucleic acid chaperone properties of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein. RNA Biol. 2010;7:687–699. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.6.13616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sleiman D., Goldschmidt V., Tisné C. Initiation of HIV-1 reverse transcription and functional role of nucleocapsid-mediated tRNA/viral genome interactions. Virus Res. 2012;169:324–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Darlix J.-L., de Rocquigny H., Mély Y. Retrospective on the all-in-one retroviral nucleocapsid protein. Virus Res. 2014;193:2–15. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sundquist W.I., Kräusslich H.-G. HIV-1 assembly, budding, and maturation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012;2:a006924. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dubois N., Khoo K.K., Bernacchi S. The C-terminal p6 domain of the HIV-1 Pr55Gag precursor is required for specific binding to the genomic RNA. RNA Biol. 2018;15:923–936. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2018.1481696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thornhill D., Olety B., Ono A. Relationships between MA-RNA binding in cells and suppression of HIV-1 Gag mislocalization to intracellular membranes. J. Virol. 2019;93:e00756-19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00756-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maki A.H., Ozarowski A., Casas-Finet J.R. Phosphorescence and optically detected magnetic resonance of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein complexes with stem-loop sequences of the genomic Psi-recognition element. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1403–1412. doi: 10.1021/bi002010i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amarasinghe G.K., De Guzman R.N., Summers M.F. NMR structure of the HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein bound to stem-loop SL2 of the psi-RNA packaging signal. Implications for genome recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;301:491–511. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Amarasinghe G.K., Zhou J., Summers M.F. Stem-loop SL4 of the HIV-1 psi RNA packaging signal exhibits weak affinity for the nucleocapsid protein. structural studies and implications for genome recognition. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:961–970. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gorelick R.J., Nigida S.M., Jr., Rein A. Noninfectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 mutants deficient in genomic RNA. J. Virol. 1990;64:3207–3211. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3207-3211.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gorelick R.J., Chabot D.J., Arthur L.O. The two zinc fingers in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein are not functionally equivalent. J. Virol. 1993;67:4027–4036. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4027-4036.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Greatorex J., Gallego J., Lever A. Structure and stability of wild-type and mutant RNA internal loops from the SL-1 domain of the HIV-1 packaging signal. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;322:543–557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00776-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tanchou V., Decimo D., Darlix J.L. Role of the N-terminal zinc finger of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein in virus structure and replication. J. Virol. 1998;72:4442–4447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.4442-4447.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berthoux L., Péchoux C., Darlix J.L. Mutations in the N-terminal domain of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein affect virion core structure and proviral DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 1997;71:6973–6981. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6973-6981.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dannull J., Surovoy A., Moelling K. Specific binding of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein to PSI RNA in vitro requires N-terminal zinc finger and flanking basic amino acid residues. EMBO J. 1994;13:1525–1533. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06414.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Retureau R., Oguey C., Hartmann B. Structural explorations of NCp7-nucleic acid complexes give keys to decipher the binding process. J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:1966–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Müller B., Daecke J., Kräusslich H.-G. Construction and characterization of a fluorescently labeled infectious human immunodeficiency virus type 1 derivative. J. Virol. 2004;78:10803–10813. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10803-10813.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dultz E., Ellenberg J. Live imaging of single nuclear pores reveals unique assembly kinetics and mechanism in interphase. J. Cell Biol. 2010;191:15–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201007076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rossow M.J., Sasaki J.M., Gratton E. Raster image correlation spectroscopy in live cells. Nat. Protoc. 2010;5:1761–1774. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vámosi G., Mücke N., Tóth K. EGFP oligomers as natural fluorescence and hydrodynamic standards. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:33022. doi: 10.1038/srep33022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Göttlinger H.G., Sodroski J.G., Haseltine W.A. Role of capsid precursor processing and myristoylation in morphogenesis and infectivity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:5781–5785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Digman M.A., Brown C.M., Gratton E. Measuring fast dynamics in solutions and cells with a laser scanning microscope. Biophys. J. 2005;89:1317–1327. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Digman M.A., Sengupta P., Gratton E. Fluctuation correlation spectroscopy with a laser-scanning microscope: exploiting the hidden time structure. Biophys. J. 2005;88:L33–L36. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.061788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dill K.A., Ghosh K., Schmit J.D. Physical limits of cells and proteomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:17876–17882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114477108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liarzi O., Epel B.L. Development of a quantitative tool for measuring changes in the coefficient of conductivity of plasmodesmata induced by developmental, biotic, and abiotic signals. Protoplasma. 2005;225:67–76. doi: 10.1007/s00709-004-0079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Anton H., Taha N., Mély Y. Investigating the cellular distribution and interactions of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein by quantitative fluorescence microscopy. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen J., Grunwald D., Hu W.-S. Cytoplasmic HIV-1 RNA is mainly transported by diffusion in the presence or absence of Gag protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E5205–E5213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413169111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hendrix J., Baumgärtel V., Lamb D.C. Live-cell observation of cytosolic HIV-1 assembly onset reveals RNA-interacting Gag oligomers. J. Cell Biol. 2015;210:629–646. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201504006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Larson D.R., Ma Y.M., Webb W.W. Direct measurement of Gag-Gag interaction during retrovirus assembly with FRET and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J. Cell Biol. 2003;162:1233–1244. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hogue I.B., Hoppe A., Ono A. Quantitative fluorescence resonance energy transfer microscopy analysis of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Gag-Gag interaction: relative contributions of the CA and NC domains and membrane binding. J. Virol. 2009;83:7322–7336. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02545-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prescher J., Baumgärtel V., Lamb D.C. Super-resolution imaging of ESCRT-proteins at HIV-1 assembly sites. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004677. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dorfman T., Luban J., Göttlinger H.G. Mapping of functionally important residues of a cysteine-histidine box in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein. J. Virol. 1993;67:6159–6169. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6159-6169.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mitra M., Wang W., Musier-Forsyth K. The N-terminal zinc finger and flanking basic domains represent the minimal region of the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 nucleocapsid protein for targeting chaperone function. Biochemistry. 2013;52:8226–8236. doi: 10.1021/bi401250a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Heath M.J., Derebail S.S., DeStefano J.J. Differing roles of the N- and C-terminal zinc fingers in human immunodeficiency virus nucleocapsid protein-enhanced nucleic acid annealing. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30755–30763. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beltz H., Clauss C., Mély Y. Structural determinants of HIV-1 nucleocapsid protein for cTAR DNA binding and destabilization, and correlation with inhibition of self-primed DNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;348:1113–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Narayanan N., Gorelick R.J., DeStefano J.J. Structure/function mapping of amino acids in the N-terminal zinc finger of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid protein: residues responsible for nucleic acid helix destabilizing activity. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12617–12628. doi: 10.1021/bi060925c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chamontin C., Rassam P., Mougel M. HIV-1 nucleocapsid and ESCRT-component Tsg101 interplay prevents HIV from turning into a DNA-containing virus. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:336–347. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Popov S., Popova E., Göttlinger H.G. Divergent Bro1 domains share the capacity to bind human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nucleocapsid and to enhance virus-like particle production. J. Virol. 2009;83:7185–7193. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dussupt V., Javid M.P., Bouamr F. The nucleocapsid region of HIV-1 Gag cooperates with the PTAP and LYPXnL late domains to recruit the cellular machinery necessary for viral budding. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000339. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Roldan A., Russell R.S., Wainberg M.A. In vitro identification and characterization of an early complex linking HIV-1 genomic RNA recognition and Pr55Gag multimerization. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:39886–39894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405632200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hübner W., Chen P., Chen B.K. Sequence of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Gag localization and oligomerization monitored with live confocal imaging of a replication-competent, fluorescently tagged HIV-1. J. Virol. 2007;81:12596–12607. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01088-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Datta S.A.K., Curtis J.E., Rein A. Conformation of the HIV-1 Gag protein in solution. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;365:812–824. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Derdowski A., Ding L., Spearman P. A novel fluorescence resonance energy transfer assay demonstrates that the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Pr55Gag I domain mediates Gag-Gag interactions. J. Virol. 2004;78:1230–1242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1230-1242.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sun M., Grigsby I.F., Musier-Forsyth K. Retrovirus-specific differences in matrix and nucleocapsid protein-nucleic acid interactions: implications for genomic RNA packaging. J. Virol. 2014;88:1271–1280. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02151-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev, and Gag and Gag-mCH were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. Gag-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔZF1-2-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔZF1-2 were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔZF1-2-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔNC-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔNC were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔNC-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔZF1-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔZF1 were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔZF1-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.

As described in Materials and Methods, sub confluent MS2-eGFP HeLa cells were placed on a microscope equipped with a chamber at 37°C, with 5% CO2. The plasmids expressing pIntro, Rev and GagΔZF2-mCH, and unlabeled GagΔZF2 were microinjected into the nucleus. The coordinates of several microinjected cells were memorized, and images were then acquired every 5 min during 2–4 h. GagΔZF2-mCH (red channel) were imaged in column 1, MS2-eGFP-gRNA (green channel) was imaged in column 2, and the merged image in column 3.