Abstract

Objective

An artificial liver support system (ALSS) is an effective therapy for patients with severe liver injury. A vasovagal reaction (VVR) is a common complication in various treatment settings but has not been reported previously in ALSS.

Methods

This study retrospectively evaluated patients who suffered an ALSS-related VRR between January 2018 and June 2019. We collected data from VVR episodes including onset time, duration, changes in heart rate (HR) and blood pressure (BP), and drug treatment.

Results

Among 637 patients who underwent ALSS treatment, 18 were included in the study. The incidence of VVR was approximately 2.82%. These patients were characterized by a rapid decrease in BP or HR with associated symptoms such as chest distress, nausea, and vomiting. The majority of patients (78%) suffered a VVR during their first ALSS treatment. Sixteen patients (89%) had associated symptoms after treatment began. Sixteen patients (89%) received human albumin or Ringer's solution. Atropine was used in 11 patients (61%). The symptoms were relieved within 20 min in 15 patients and over 20 min in 3 patients.

Conclusions

A VVR is a rare complication in patients with severe liver injury undergoing ALSS treatment. Low BP and HR are the main characteristics of a VVR.

1. Introduction

Liver failure is a severe clinical syndrome characterized by hepatic encephalopathy, jaundice, coagulopathy, and a high mortality rate. Hepatitis viruses, drugs, or toxins can precipitate acute liver failure in patients with or without chronic liver disease [1]. Unfortunately, liver transplantation currently remains the only definitive treatment option for irreversible liver failure [2]. Approximately 90% of patients are cured after liver transplantation [3, 4], but there is a serious shortfall of donors, especially in China, and costs are considerable for many families. Some patients recover spontaneously with standard medical therapy.

Artificial liver support systems (ALSSs) are a bridge to liver transplantation or recovery after liver failure and are useful means of improving biochemical parameters and clinical symptoms [5]. An ALSS is an external support system that can remove several types of harmful substances while supplementing essential substances, thereby improving the internal environment and create conditions for the regeneration of liver cells and restoration of liver function. There are various modalities connecting treatment units either in series or in parallel such as plasma exchange (PE) combined with hemofiltration (HF), molecular absorbent recirculatory systems, fractionated plasma separation and absorption (using the Prometheus system), and double plasma molecular absorption systems (DPMAS).

The safety of most ALSS devices has been well established by clinical studies [2]. Commonly reported side effects of ALSSs include filter clotting, leukocytosis, hypotension, bleeding, anaphylaxis, and thrombocytopenia [2]. A vasovagal reaction (VVR) is an abnormal autonomic imbalance precipitated by pain, hunger, heat, imagined or real exposure to bodily harm, certain medical and surgical procedures, cardiac spasm, distention of viscera, and pleural or peritoneal irritation, which is characterized by hypotension followed by paradoxical bradycardia [6]. More seriously, strong vagal stimulation may lead to arrhythmias, syncope, transient asystole, seizures, or death [7–10]. To the best of our knowledge, a VVR during ALSS treatment has not been reported previously. Here, we describe 18 patients who experienced a VVR during treatment with an ALSS.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of patients who underwent ALSS treatment for liver failure at our hospital and suffered an ALSS-related VVR from January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019.

A VVR was defined as the presence of at least one of the following criteria with associated symptoms: (1) bradycardic episode (heart rate (HR) < 60 beats/min (bpm)) and hypotension (systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 100 mmHg) in the supine position or (2) development of syncope [6, 11]. Common symptoms include pallor, faintness, dizziness, sweating, nausea, shivering, vomiting, heat intolerance, cold intolerance, and loss of consciousness [12]. Exclusion criteria were heart failure, myocardial infarction, or other severe liver diseases. A VVR was noted only if the reaction occurred following the entire procedure, including femoral vein catheter placement.

2.2. Data Collection

Data collected at the time of ALSS treatment included age, sex, body mass index, etiology of liver failure, serum total bilirubin (TB) level, alanine and aspartate aminotransferase (ALT, AST) levels, glucose level, and international normalized ratio (INR). The diastolic blood pressure (DBP), SBP, and HR after extracorporeal circulation were used as the baseline data. When a VVR occurred, the onset time, minimum BP and HR, symptoms, treatment measures, and recovery time were all recorded in detail.

2.3. ALSS Treatment

The indications for ALSS treatment were based on the Chinese Guideline for Diagnosis and Treatment of Liver Failure [13] and include (1) early- or intermediate-stage acute, subacute, and acute-on-chronic liver failure (prothrombin activity of 20–40%); (2) end-stage liver disease awaiting liver transplantation; (3) rejection after liver transplantation or a nonfunctional transplanted liver; and (4) severe cholestasis (TB > 10 mg/dL) due to ineffective medical treatment. PE combined with HF was administered to five patients. PE was performed for 2 h each time using the EC-40 W plasma separator (Asahi Kasei, Japan), and the replacement fluid contained 500–1,000 mL albumin plus 1,500–2,000 mL fresh frozen plasma, for a total exchange volume of 2,500–3,000 mL. Subsequently, HF was performed continuously for approximately 4–6 h using the BLS816G (SORIN Group, Italy) at a filtrate flow rate of 50 mL/kg/h. The entire procedure lasted 6–8 h. A DPMAS was used to treat 13 patients. The plasma was separated using the EC-40 W device (Asahi Kasei), purified by an anion exchange resin column (HA330-II, Jian Fan, China) and a bilirubin adsorption column (BS330, Jian Fan), and finally returned to the patient. ALSS treatment was administered using the IQ21 machine (Asahi Kasei). A double-lumen catheter was inserted into the femoral vein to obtain vascular access. Heparin was given to prevent coagulation, with the dosage adjusted based on the transmembrane pressure and activated partial thromboplastin time. A plasma allergy was prevented by administering 5 mg dexamethasone before ALSS treatment.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data were compared using Student's t-test conducted in Prism, version 8.0.0 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

3. Results

Among 637 patients who underwent ALSS treatment, a VVR occurred in 18 (2.82%), who were included in the study. The clinical features of the 18 patients (9 males and 9 females) are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 53.2 (range 22–74) years, and the mean body mass index was 21 (range 18–28) kg/m2; excluding patient 17 who was too weak to obtain height or weight data. The most common etiology of liver failure was hepatitis B virus (56%), followed by drugs (22%). The glucose levels in all patients were normal to high (range 6.7–16.8 mmol/L) at the time of the VVR. All patients exhibited increased aminotransferase levels: the ALT level ranged from 39 to 427 (mean 138) U/L and the AST level from 34 to 383 (mean 129) U/L. Jaundice was present in all 18 patients. The serum TB level ranged from 175 to 583 (mean 358) μmol/L. In five patients, coagulation dysfunction was present, with an INR level ≥ 1.5 (the peak INR level was 2.78 in patient 15).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 18 cases of ALSS-associated VVR.

| Variable | Age (years) | Sex | BMI (kg/m2) | Etiology of liver injury | Glu (mmol/L) | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | TBil (μmol/L) | INR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient 1 | 49 | Male | 23 | Hepatitis B virus | 9.7 | 57 | 135 | 583 | 2.15 |

| Patient 2 | 62 | Female | 24 | Hepatitis B virus | 13.4 | 53 | 69 | 529 | 1.47 |

| Patient 3 | 71 | Male | 21 | Mixed | 16.8 | 427 | 243 | 283 | 2.71 |

| Patient 4 | 50 | Female | 19 | Drugs | 8.1 | 79 | 74 | 337 | 0.96 |

| Patient 5 | 53 | Male | 21 | Hepatitis B virus | 7.8 | 183 | 74 | 202 | 0.92 |

| Patient 6 | 59 | Female | 19 | Cholestasis | 10.2 | 425 | 383 | 366 | 1.19 |

| Patient 7 | 73 | Female | 18 | Drugs | 14.9 | 213 | 249 | 175 | 0.92 |

| Patient 8 | 54 | Male | 21 | Hepatitis B virus | 14.2 | 91 | 93 | 332 | 1.48 |

| Patient 9 | 59 | Female | 21 | Drugs | 8.9 | 124 | 214 | 254 | 1.64 |

| Patient 10 | 69 | Female | 22 | Drugs | 9.3 | 54 | 34 | 353 | 0.97 |

| Patient 11 | 27 | Male | 19 | Hepatitis B virus | 8.7 | 97 | 89 | 372 | 1.41 |

| Patient 12 | 62 | Female | 18 | Cholestasis | 12.4 | 151 | 69 | 333 | 1.12 |

| Patient 13 | 44 | Male | 21 | Hepatitis B virus | 9.7 | 39 | 58 | 322 | 1.16 |

| Patient 14 | 22 | Male | 23 | Hepatitis B virus | 6.7 | 77 | 94 | 401 | 1.3 |

| Patient 15 | 74 | Female | 21 | Hepatitis B virus | 10.8 | 60 | 59 | 322 | 2.78 |

| Patient 16 | 26 | Male | 28 | Hepatitis B virus | 9 | 113 | 165 | 548 | 1.49 |

| Patient 17 | 67 | Female | Unavailable | Mixed | 11.6 | 92 | 133 | 398 | 2.68 |

| Patient 18 | 37 | Male | 26 | Hepatitis B virus | 8.5 | 146 | 82 | 341 | 1.9 |

Note. ALSS: artificial liver support system; VVR: vasovagal reaction; BMI: body mass index; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; TBil: total bilirubin; INR: international normalized ratio; Glu: glucose.

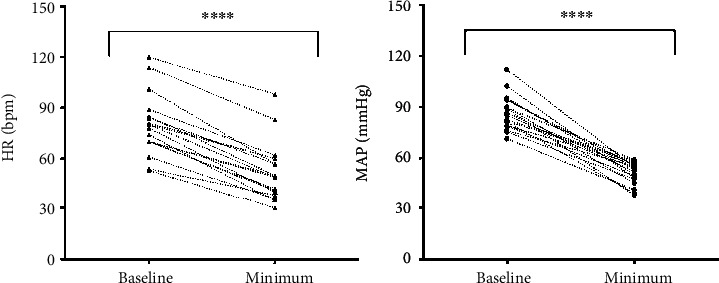

Detailed information on ALSS treatment and the VRRs, including modality of ALSS, VVR duration, changes in HR and BP, and treatment provided for the VVR, are listed in Table 2. Of the 18 patients, 13 (72%) were managed using a DPMAS, and the remaining 5 (28%) received PE combined with HF. The majority of patients (78%) suffered a VVR during their first ALSS treatment. Sixteen patients experienced the relevant symptoms after treatment commenced and the onset time of VVR ranged from 10 to 100 min. Only two patients experienced symptoms during femoral vein catheter placement. The VVR was associated with significant changes in BP and HR. The mean basal and minimum HR were 80 and 52 bpm, respectively, and the mean basal and minimum SBP were 119 and 72 mmHg, respectively. Trends in HR and mean arterial pressure are described in Figure 1. Dizziness, sweating, nausea, and chest distress were frequently reported by these patients.

Table 2.

Detailed procedural features of ALSS and VVR.

| Baseline | Minimum | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modality of ALSS | Treatment times of ALSS | Onset time of VVR (since the treatment began) | Time of duration | HR (bpm) | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | HR (bpm) | SBP (mmHg) | DBP (mmHg) | Symptoms | Drug treatment | |

| P1 | PE+CRRT | 1 | 30 minutes | 7 minutes | 81 | 100 | 64 | 60 | 78 | 44 | Chest distress, waist discomfort | Dopamine 0.8 mg, aramine 0.4 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P2 | DPMAS | 1 | 30 minutes | 10 minutes | 53 | 114 | 61 | 30 | 61 | 44 | Chest distress, nausea, dizziness, yawning | Adrenaline 0.04 mg, human albumin, Ringer's solution |

| P3 | PE+CRRT | 1 | 31 minutes | 7 minutes | 101 | 156 | 90 | 57 | 74 | 45 | Yawning, waist discomfort, defecation | Human albumin |

| P4 | DPMAS | 3 | 63 minutes | 17 minutes | 70 | 108 | 70 | 41 | 85 | 45 | Abdominal distension | Atropine 0.5 mg, dopamine 3 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P5 | DPMAS | 1 | During catheter placement, 20 minutes | 5 minutes, 70 minutes | 78 | 109 | 64 | 40 | 76 | 47 | Nervousness | Atropine 0.25 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P6 | DPMAS | 1 | 49 minutes | 10 minutes | 70 | 102 | 56 | 49 | 58 | 33 | Palpitation, sweating | Atropine 0.5 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P7 | DPMAS | 1 | 20 minutes | 10 minutes | 85 | 109 | 67 | 50 | 56 | 31 | Chest distress, nausea, dizziness | Dopamine 20 mg, human albumin |

| P8 | DPMAS | 1 | 34 minutes | 5 minutes | 61 | 124 | 79 | 36 | 79 | 42 | Chest distress | Atropine 0.5 mg |

| P9 | DPMAS | 1 | 30 minutes | 30 minutes | 74 | 120 | 68 | 35 | 67 | 45 | Chest distress, nausea, dizziness | Atropine 0.5 mg, dopamine 20 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P10 | DPMAS | 1 | 40 minutes | 3 minutes | 70 | 132 | 68 | 42 | 52 | 31 | Chest distress | Atropine 0.5 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P11 | DPMAS | 3 | 56 minutes | 5 minutes | 80 | 120 | 70 | 49 | 83 | 39 | Abdominal pain | Atropine 0.5 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P12 | DPMAS | 2 | 100 minutes | 5 minutes | 54 | 142 | 72 | 38 | 72 | 40 | Urination, abdominal distension | Atropine 0.5 mg, Ringer's solution, dopamine 20 mg, human albumin |

| P13 | DPMAS | 1 | 63 minutes | 9 minutes | 89 | 119 | 82 | 62 | 79 | 44 | Abdominal discomfort, nausea | Human albumin |

| P14 | DPMAS | 1 | 50 minutes | 15 minutes | 80 | 107 | 69 | 60 | 89 | 42 | Dizziness, tinnitus | Ringer's solution |

| P15 | PE+CRRT | 3 | 10 minutes | 10 minutes | 70 | 125 | 72 | 50 | 79 | 49 | Sore back | Human albumin, Ringer's solution |

| P16 | DPMAS | 1 | 10 minutes | 40 minutes | 114 | 114 | 78 | 83 | 63 | 36 | Chest distress, palpitation, nausea, vomiting | Dexamethasone 3 mg, atropine 0.5 mg, dopamine 6 mg, aramine 3 mg, Ringer's solution |

| P17 | PE+CRRT | 1 | 15 minutes | 11 minutes | 120 | 112 | 57 | 98 | 67 | 38 | Yawning, dry mouth | Atropine 0.25 mg |

| P18 | Li-ALS | 1 | During catheter placement | 8 minutes | 84 | 135 | 86 | 57 | 75 | 35 | Nervousness, chest distress, dizziness | Atropine 0.5 mg, Ringer's solution |

Note. ALSS: artificial liver support system; VVR: vasovagal reaction; PE: plasma exchange; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; DPMAS: double plasma molecular absorb system; Li-ALS: Li's artificial liver system; HR: heart rate; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure.

Figure 1.

A plot of the individual HR (a) and MAP (b) at baseline and minimum during VVR. Both HR and MAP decreased significantly between two periods of time. VVR: vasovagal reaction; MAP: mean blood pressure; HR: heart rate. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001.

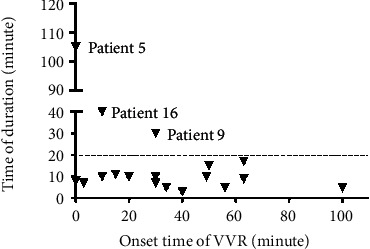

During treatment, most patients (89%) received human albumin or Ringer's solution to increase the circulating blood volume. Atropine, as an effective drug for blocking a VVR, was used in more than half of the patients (61%). Six patients received dopamine with or without aramine. The VVR duration was short (<20 min) in 15 patients and more than 20 min in 3 patients, ranging from 3 to 105 min. The VVR time of onset and duration in all 18 patients are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A plot of individual onset time and time of duration of VVR. VVR: vasovagal reaction.

4. Discussion

We detected an incidence of a VVR occurring during ALSS treatment of 2.82%. There are no previously published data on VVR incidence for comparison with our results. It is important differentiate VVR from hypoglycemia. VVR is a rare complication of ALSS treatment and is more frequently associated with spine procedures [14], blood donation [15], cerebral angiography via femoral catheterization [11], and percutaneous coronary intervention [16]. In the general blood donor population, the VVR rate was reported to be 1.4%. VVR during spinal injection was found to be a common adverse event, with a rate of 0–8.6. [14] As for PE treatments, it was reported that the VVR rate was about 0.5%, in which the patients were diagnosed with the Guillain-Barre syndrome, myasthenia gravis, and so on, but liver injury were not included [17]. Compared with other conditions, a VVR incidence of 2.82% may be considered moderate.

In the present study, all patients during the VVR experienced a remarkable decrease in BP or HR accompanied by symptoms such as dizziness and sweating. Symptoms and signs returned to normal within 3–105 min, which is similar to the duration (from several minutes to 2 h) reported in a study of VVR associated with cerebral angiography [11]. Sixteen (89%) instances of VVR occurred during normal ALSS treatment, ranging from 10 to 100 min after treatment commenced. The remaining two instances of VVR occurred during femoral vein catheter placement. In a study on VVR occurring during blood donation [18], 54.4% of VVR episodes occurred during blood collection, 28.6% after collection and 9.8% after entering the refreshment area; 1.4% occurred even later, after the donor had left the site. In addition, 5.9% of VVR incidents was associated with blood test procedures requiring venipuncture. In short, VVR occurred before, during, and after blood collection, whereas ALSS-related VVR occurred mainly before and during ALSS treatment.

The vagus nerve runs throughout the vascular endothelial system. Physiologically, a VVR is believed to be caused by the initial increase in BP and HR due to an adrenergic response, followed by overcompensation by a sudden withdrawal of sympathetic tone and increased parasympathetic tone, resulting in splanchnic vasodilation, bradycardia, and decreased cerebral blood flow [19]. Hypermetabolism in the adrenal gland responsible for synthesizing and secreting catecholamines is indicated by increased adrenal fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation on positron emission tomography/computed tomography [20]. Elements such as fear, pain, and a bad mood can be triggers, leading to a strong autonomic response [12]. Internal factors such as hyperventilation, hypotension, and stress may also precipitate a VVR in some cases [21]. Alcohol ingestion may predispose individuals to a VVR in the clinical setting [22].

Patients require femoral vein catheter placement before ALSS treatment. Two patients experienced a VVR during this procedure. As reported by other studies, patients who received a vascular interventional examination or therapy were more likely to develop a VVR, which was commonly seen at the time of sheath placement [11]. A poor response to intraoperative local anesthesia, which may increase the patient's pain sensitivity, and stimulation of the vascular intima by a guide wire or catheter both can cause enhanced excitability of the vascular vagus nerve. On the other hand, patient anxiety or even insomnia may stimulate the pressure transducers in the left ventricle and carotid artery, leading to enhanced vagus nerve excitability [11]. When treatment begins, a portion of the blood flows into the pipeline, which results in relative hypovolemia, similar in some respects to blood donation. In patients with liver failure, toxins typically accumulate in the blood vessels to cause an attenuated vasoconstrictor response. As a result, mobilization of the peripheral venous blood and net fluid absorption from tissues to blood decrease [23].

VVR is an unexpected high-risk condition that may cause irreversible harm including arrhythmias, syncope, myocardial infarction, transient asystole, and seizures even death to patients without timely treatment [7–10, 24]. Most patients who develop VVR could recover after timely and accurate treatment in previous study [6], the same as we have observed. In our 18 patients, therapy for symptomatic hypotension and bradycardia was administered according to the judgement of the clinician. The treatment measures included stopping the pump of the machine, change in position (supine position with the head turned to one side or the Trendelenburg position), and fluid infusion. The final measure was intravenous injection of atropine, dopamine, aramine, or adrenaline. All patients recovered after timely and appropriate treatment. According to our experience and a literature review, we devised a suggested treatment algorithm. First, operation of the ALSS device should be stopped to reduce stimulation and prevent a further reduction of the circulating blood volume. The patient's anxiety should be assuaged by reassurance and “talk-esthesia.” [12] Second, reclining the patient rapidly into the Trendelenburg position helps facilitate perfusion to the brain [25]. Hand holding will help increase peripheral resistance and venous return [26]. Third, sufficient fluid infusion is essential. Human albumin and Ringer's solution are optional. If these measures are ineffective, 0.5 mg atropine should be injected intravenously at an appropriate dosage to reverse vagal cardiac stimulation. If the BP drops markedly, dopamine and aramine should be used. If asystole occurs, the emergency activation system should be initiated.

In an ALSS treatment setting, these steps can be taken to minimize the risk of a VVR as much as possible. It has been reported that during blood donation, the fear of drawing blood was associated with an approximately threefold increase in the odds of experiencing a VVR [27]. Thus, humanistic concern and psychological counseling are beneficial. Before treatment, clinicians should explain the entire ALSS procedure and related complications to the patient in detail to eliminate their fear and anxiety. The support of a family member or trusted friend is integral [12]. Patients should be encouraged to eat regularly and drink adequate fluids while avoiding alcohol before treatment [12]. At the time of femoral vein catheter placement, sufficient local anesthesia may reduce pain stimulation [16]. During ALSS treatment, medical personnel can communicate with the patient to create a nonthreatening and relaxing environment. Furthermore, the BP, HR, and subjective symptoms of the patient should be closely monitored, since early discovery and treatment of VVR can prevent severe outcomes.

The present study has some limitations. In this retrospective analysis, the data were collected in a strict prospective manner utilizing electronic medical records. The number of cases was limited. Furthermore, data following catheter removal were unavailable. A larger-scale prospective study is required to validate our findings.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, a VVR is a rare complication that can occur before or during ALSS treatment for liver failure, including during catheter placement. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of a VVR and take the appropriate measures to prevent its occurrence.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Department of Science and Technology of Zhejiang Province (2017C03051) and Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81721091).

Contributor Information

Xiaowei Xu, Email: xxw69@zju.edu.cn.

Lanjuan Li, Email: ljli@zju.edu.cn.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital.

Consent

Informed consent from the patient was obtained.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors' Contributions

Shanshan Ma and Zhongyang Xie contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Lee W. M. Acute liver failure. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329(25):1862–1872. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312163292508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aron J., Agarwal B., Davenport A. Extracorporeal support for patients with acute and acute on chronic liver failure. Expert Review of Medical Devices. 2016;13(4):367–380. doi: 10.1586/17434440.2016.1154455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen J. W., Hassanein T., Bhatia S. N. Advances in bioartificial liver devices. Hepatology. 2001;34(3):447–455. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Russell P. S. Understanding resource use in liver transplantation. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;281(15):1431–1432. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.15.1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpentier B., Gautier A., Legallais C. Artificial and bioartificial liver devices: present and future. Gut. 2009;58(12):1690–1702. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.175380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rama B. N., Mohiuddin S. M., Mooss A. N., et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled evaluation of atropine to prevent vasovagal reaction during removal of femoral arterial sheaths. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17(5):867–873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bourne J. G. Fainting and cerebral damage; a danger in patients kept upright during dental gas anaesthesia and after surgical operations. Lancet. 1957;270(6994):499–505. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(57)90820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engel G. L. Psychologic stress, vasodepressor (vasovagal) syncope, and sudden death. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1978;89(3):403–412. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-89-3-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlesinger Z., Barzilay J., Stryjer D., Almog C. H. Life-threatening "vagal reaction" to emotional stimuli. Israel Journal of Medical Sciences. 1977;13(1):59–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tizes R. Cardiac arrest following routine venipuncture. JAMA. 1976;236(16):1846–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.1976.03270170012013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y., Zhang Z., Li T., Gu Z., Sun Y. Risk factors for vasovagal reaction associated with cerebral angiography via femoral catheterisation. Interventional Neuroradiology. 2017;23(5):546–550. doi: 10.1177/1591019917717577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu W. J., Goldberg L. H., Rubenzik M. K., Zelickson B. R. Review of the evaluation and treatment of vasovagal reactions in outpatient procedures. Dermatologic Surgery. 2018;44(12):1483–1488. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Artificial, Liver Group, Liver Disease Severe, Liver Group Artificial, Chinese Medical Chinese Society of Hepatology and Medical Association. Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of liver failure. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2019;27(1):18–26. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy D. J., Schneider B., Smuck M., Plastaras C. T. The use of moderate sedation for the secondary prevention of adverse vasovagal reactions. Pain Medicine. 2015;16(4):673–679. doi: 10.1111/pme.12632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong H. K., Lee C. K., Leung J. N., Lee I. Y., Lin C. K. Reduction in vasovagal reaction rate in young first-time blood donors by collecting 350 mL rather than 450 mL. Transfusion. 2013;53(11):2763–2765. doi: 10.1111/trf.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiat Ang C., Leung D. Y. C., Lo S., French J. K., Juergens C. P. Effect of local anesthesia and intravenous sedation on pain perception and vasovagal reactions during femoral arterial sheath removal after percutaneous coronary intervention. International Journal of Cardiology. 2007;116(3):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Winters J. L. Plasma exchange: concepts, mechanisms, and an overview of the American Society for Apheresis guidelines. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2012;2012(1):7–12. doi: 10.1182/asheducation.V2012.1.7.3797920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takanashi M., Odajima T., Aota S., et al. Risk factor analysis of vasovagal reaction from blood donation. Transfusion and Apheresis Science. 2012;47(3):319–325. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Graham D. T., Kabler J. D., Lunsford L., Jr. Vasovagal fainting: a diphasic response. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1961;23(6):493–507. doi: 10.1097/00006842-196111000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Otomi Y., Shinya T., Otsuka H., et al. Increased (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose accumulation in bilateral adrenal glands of the patients suffering from vasovagal reaction due to blood vessel puncture. Annals of Nuclear Medicine. 2016;30(7):501–505. doi: 10.1007/s12149-016-1088-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alboni P. The different clinical presentations of vasovagal syncope. Heart. 2015;101(9):674–678. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-307096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viski S., Orosz M., Czuriga-Kovacs K. R., Magyar M. T., Csiba L., Olah L. The acute effects of alcohol on cerebral hemodynamic changes induced by the head-up tilt test in healthy subjects. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2016;368:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skoog J., Zachrisson H., Länne T., Lindenberger M. Reduced compensatory responses to maintain central blood volume during hypovolemic stress in women with vasovagal syncope. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2017;312(1):R55–r61. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00166.2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sreckovic M. J., Jagic N., Zdravkovic V., et al. Coronary spasm that caused non-ST elevation myocardial infarction appeared in cath lab due to vasovagal reaction. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2014;10(2):138–140. doi: 10.5114/pwki.2014.43525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pavlin D. J., Links S., Rapp S. E., Nessly M. L., Keyes H. J. Vaso-vagal reactions in an ambulatory surgery center. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 1993;76(5):931–935. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taddio A., Shah V., McMurtry C. M., et al. Procedural and physical interventions for vaccine injections: systematic review of randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2015;31(10 Suppl):S20–S37. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.France C. R., France J. L., Frame-Brown T. A., Venable G. A., Menitove J. E. Fear of blood draw and total draw time combine to predict vasovagal reactions among whole blood donors. Transfusion. 2016;56(1):179–185. doi: 10.1111/trf.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.