Abstract

Objective:

To study the development of children conceived from non-IVF infertility treatments consisting of gonadotropins, clomiphene or letrozole.

Design:

Prospective cohort study

Setting:

U.S Academic Health Centers

Patients:

Children of women with PCOS who conceived with Letrozole(LTZ) or Clomiphene(CC) in PPCOS II study, or women with unexplained infertility(AMIGOS study) who conceived with LTZ, CC or gonadotropin(GN).

Interventions:

Longitudinal annual follow up from birth to Age 3 of the children.

Main Outcome measures:

Scores from Ages and Stages Developmental Questionnaire(ASQ), MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventor(MCDI) and annual growth.

Results:

185 children from 160 families participated in at least one follow-up evaluation from the two infertility trials. Most multiple gestation families in follow-up study resulted from GN treatment(N=14) followed by CC(N=6) followed by LTZ(N=3). There were no significant differences among the 3 groups at any time point with respect to abnormal scores on the ASQ. On the MCDI Words and Gestures, the LTZ group scored significantly higher than the GN group for all items(phrases p=0.02, words understood p=0.04, words produced p=0.04, early gestures p=0.01, later gestures p<.001 and total gestures p<.001). Children in the CC group scored significantly higher than the GN group for the later gestures and total gestures items(p=0.04 for both) and scored significantly lower than the LTZ group for those same 2 items(p=0.02 and 0.04, respectively).

Conclusions:

Differences in growth and cognitive developmental rates among children conceived with first line infertility therapies, including letrozole, are relatively minor and likely due to differences in multiple pregnancy rates.

Keywords: infertility, children; infant growth, cognitive development; ovulation induction

INTRODUCTION

Children conceived from infertility therapy are thought generally to develop normally. However, there have been reports to suggest increased rates of congenital and chromosomal anomalies(1) when using specific technologies (such as ICSI),(2) singleton babies born premature or small for gestational age(3) and concerns about developmental delays during infancy.(4) However most of these studies have focused on children conceived through in vitro fertilization (IVF) and related technologies and not through ovulation induction for anovulation infertility or ovarian stimulation for unexplained infertility. It is estimated that 3–7% of children in the U.S. are conceived through such technologies versus 1–2% through IVF. Thus, the long term developmental path of these children is of public health relevance.

Although smaller studies of children have shown some concerns about developmental delays in children conceived from non-IVF infertility treatments,(5) the largest prospective cohort study of over 5000 children (The UPSTATE KIDS study) including over 1800 conceived by infertility therapy found no differences in developmental delays between children conceived with non-assisted reproductive technology (ART) infertility therapy and control children.(6) Though reassuring, nonetheless the use of newer ovulation induction/ovarian stimulation agents such as letrozole has raised concerns about their potential effects on development.

We conducted through the NIH-supported Reproductive Medicine Network (RMN) two large randomized trials of ovarian stimulation agents in infertile women; Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II (PPCOS II)(7) which studied the use of clomiphene vs letrozole for ovulation induction in women with PCOS combined with timed intercourse with their partners, and Assessment of Multiple Intrauterine Gestations from Ovarian Stimulation (AMIGOS)(8) which studied the use of letrozole, clomiphene and gonadotropins for ovarian stimulation in women with unexplained infertility combined with intrauterine insemination from their partners.

We obtained a separate investigational new drug (IND) for the use of letrozole as an infertility agent from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for both studies. As part of the requirement for obtaining the IND, we were asked to report all fetal anomalies including those discovered by an exam from a developmental pediatrician or geneticist within the first 6 weeks of life and also to create a pregnancy registry to follow children whose parents consented to the additional protocol for up to 36 months after birth. This was done to track any medical issues which occurred after birth as well as to track development. We have previously reported in our primary outcome papers the anomalies we found among children conceived with these drugs (without any difference in rate or patterns by specific drugs).(7, 8) We report here the primary outcomes we captured on the children over their first 36 months of life: the comparative rates of development by group (i.e. conception based on the maternal infertility medication) based on the results of annual developmental surveys that were administered to the parents of the child. In addition, we collected as part of the registry the annual growth as well as any medical problems or hospitalizations that were abstracted from medical records.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

We have previously published the protocols,(9, 10) baseline data(11, 12) and primary outcome papers for the both the PPCOS II and AMIGOS studies. (7, 8) All women were age 18–40 years with no limitations on weight in either study and no other major infertility factors. In the PPCOS II study Women with PCOS had anovulation combined with either hyperandrogenism or polycystic ovaries on ultrasound with the exclusion of PCOS mimis. In the AMIGOS trial, women with unexplained infertility had normal menses (nine or more cycles per year). All women gave written informed consent and studies were IRB approved at each participating center and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (PPCOS II: NCT00902382 and AMIGOS: NCT00902382) In brief, in the PPCOS II study, 750 women with PCOS were randomized to either clomiphene or letrozole in a double blind study and received up to 5 cycles of ovulation induction with timed intercourse. In the AMIGOS study, 900 women with unexplained infertility were randomized to either clomiphene, letrozole or gonadotropins (clomiphene and letrozole were doubled blinded, gonadotropins were open label) for up to 4 cycles combined with single insemination after trigger with intramuscular human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).

Women who conceived in the PPCOS II and AMIGOS studies and had ongoing pregnancies were consented separately into our pregnancy registry study which was IRB approved at each site.

Protocol

Women who consented to the pregnancy registry protocol were contacted annually for three years (i.e. at 12, 24 and 36 months after birth). They were asked to provide medical records documenting growth (height and weight) of the child as tracked by their pediatrician on the growth chart as well as written records of illnesses, prescription drug use and hospitalizations. The parents were also administered by mail two developmental questionnaires on their child: The Ages and Stages Questionnaire and The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory, which were age appropriate to the 12, 24 and 36 month timepoints.

The Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ) is a parent-completed child evaluation tool that assesses the level of physical, social and emotional, and intellectual development. The ASQ meets federal mandates for early childhood developmental screening. (http://www.nncc.org/Child.Dev/ages.stages.new.one.html#anchor265293, accessed 5/21/2008; http://www.agesandstages.com/ accessed 5/21/2008). The Ages and Stages Questionnaire contains 19 questionnaires, each corresponding to a specific age between 4 months and 5 years, with 30 developmental items addressing five domains: communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem solving, and personal/social.(13) They have been used by the Maternal Fetal Medicine Network to follow up infants exposed to drugs in utero(14) as well as in the UPSTATE KIDS prospective cohort study.(6)

The Ages and Stages Questionnaires provide cutoffs, i.e. thresholds, below which the child may need further evaluation and early intervention services. The Ages and Stages Questionnaire has been validated against professionally administered tools such as the Bayley Scales of Infant Development and McCarthyScales of Children’s Abilities. The questionnaire comes with explicit instructions and has been demonstrated to be valid when administered by the child’s guardian.

The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (MCDI) is utilized to assess the child’s language development and general communication.(15, 16) The MCDI is a survey that is designed to be completed by the parent collecting measures such as early vocabulary, non-verbal communication, functional object use and play skills. The CDI: Words and Gestures (Infant form) is designed for use with 8- to 16- month old children. The CDI: Words and Sentences (Toddler form) is designed for use with 16- to 30-month old children. We utilized the one page short form versions of each of these instruments that have also been validated. The infant form is comprised of an 89-word vocabulary checklist with separate columns for comprehension and production. Two equivalent versions of the toddler form each contain a 100- word productive vocabulary checklist and a question about combining words. The short forms can serve as an alternative to the full versions when rapid assessment of a child’s language level is needed or when parental literacy is low. For analyses, we focused on percentile items from the MCDI.

Statistical Plan

The data from this registry are observational, and the sample sizes of the PPCOS II and AMIGOS trials were determined to reach adequate power for the primary outcome of live birth, not any infant outcomes tracked in the pregnancy registry. The fact that we established this registry reflects the reality that sparse information is published or available on the outcomes. Thus, we did not include a formal power analysis in the design of this protocol.

Generalized linear mixed-effects models with a logit link were used to compare the 3 groups at each time point (12, 24, and 36 months) with respect to the proportion of children who fell below the cutoff of at least one of the 5 ASQ domains. The generalized linear mixed-effects models included a maternal-level random intercept to account for the correlation due to clustering of children (i.e., twins, triplets) within mother. For each item of the MCDI Words and Gestures questionnaire and Words and Sentences questionnaire, a general linear model with correlated errors to account for the clustering of children within mother was used to assess differences among the 3 groups. Quadratic random coefficients models were used to compare growth, i.e. weight, over time (0, 12, 24, and 36 months) between the 3 groups for males and females separately.

RESULTS

Participation in the annual pregnancy registry follow up is defined as receipt of either the pediatric records or parent-completed questionnaires. Overall 40.2% of eligible live birth families (160/398) participated in the registry follow up study from the two infertility trials (76 from PPCOS II, the study of women with PCOS, and 84 from AMIGOS, the study of women with unexplained infertility). However, a larger number were consented during their pregnancies (60.3%, 116 from PPCOS II and 124 from AMIGOS). The gonadotropin arm had the largest number of multiple pregnancies participating in the follow up study (N = 14) followed by the clomiphene arm (N = 6) followed by the letrozole arm (N = 3). A total of 185 children (80 from PPCOS II and 105 from AMIGOS) were included in the follow up study. The breakdown of participating children by treatment group, timepoint, sex of the child, and type of pregnancy is found in Supplemental Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of live birth parents who consented to the registry and live birth parents who did not consent to the registry are provided in Supplemental Table 2. Latina mothers as well as mothers with less education were significantly less likely to consent to participate. Characteristics of the parents of the children in the study by medication treatment group are found in Table 1. Birthweight, reported as mean (standard deviation), of the children participating in the follow up was 2767 (820) grams for the gonadotropin group, 3040 (507) grams for the clomiphene group, and 3325 (621) grams for the letrozole group. Of the children in the gonadotropin, clomiphene, and letrozole groups, respectively, 31 (49.2%), 22 (37.9%) and 29 (46.0%) were male.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of parents whose children participated in the follow up study

| Mothers | Fathers | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonadotropin N=47 |

Clomiphene N=52 |

Letrozole N=61 |

Gonadotropin N=47 |

Clomiphene N=52 |

Letrozole N=60* |

|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) |

|

| Age (yrs) | 32.0 (4.4) | 29.1 (3.9) | 29.1 (4.0) | 34.4 (5.3) | 30.5 (3.7) | 31.2 (4.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.1 (7.6) | 28.7 (8.1) | 30.4 (7.8) | 28.6 (4.8) | 28.1 (5.2) | 29.1 (5.8) |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Race/ethnicity$ | ||||||

| White | 40 (85.1) | 49 (94.2) | 50 (82.0) | 43 (91.5) | 47 (90.4) | 49 (81.7) |

| Black | 2 (4.3) | 1 (1.9) | 7 (11.5) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (5.8) | 9 (15.0) |

| Asian | 2 (4.3) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (3.3) | 2 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) |

| Mixed race | 3 (6.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3 (6.4) | 3 (5.8) | 4 (6.6) | 1 (2.1) | 9 (17.3) | 6 (10.0) |

| Education | ||||||

| High school graduate or less | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.8) | 9 (14.8) | 5 (10.6) | 8 (15.4) | 18 (30.0) |

| Some college/college degree | 32 (68.1) | 29 (55.8) | 41 (67.2) | 30 (63.8) | 33 (63.5) | 38 (63.3) |

|

Graduate degree |

15 (31.9) | 20 (38.5) | 11 (18.0) | 12 (25.5) | 11 (21.2) | 4 (6.7) |

| Prior live birth | 10 (21.3) | 12 (23.1) | 8 (13.1) | — | — | — |

One father was missing baseline characteristics data

Race/ethnicity was reported by the patients. Some patients chose more than one category, including Hispanic or Latino.

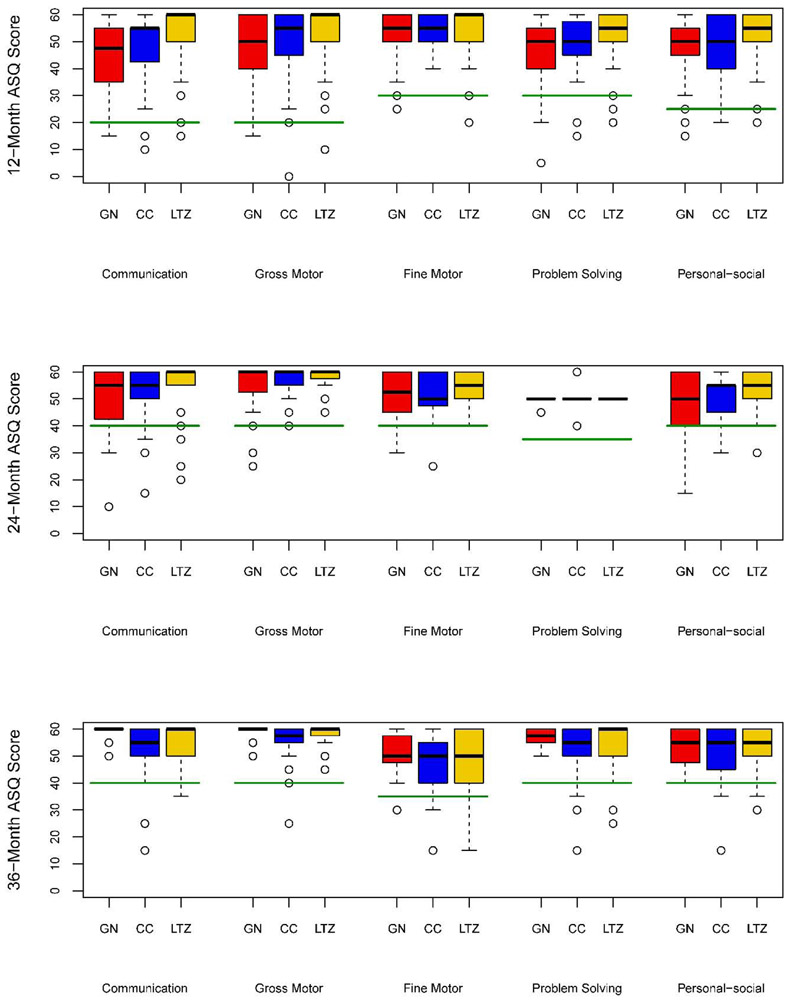

The Ages and Stages Questionnaire

Figure 1 shows the results of the ASQ by the conception drug used by the mother. The sample sizes for the gonadotropin, clomiphene, and letrozole groups, respectively, were 58, 56, and 52 children at 12 months, 40, 35, and 39 children at 24 months, and 12, 22, and 24 children at 36 months. At 12 months, we identified 8 (13.8%) children in the gonadotropin group, 5 (8.9%) in the clomiphene group and 7 (13.5%) in the letrozole group who scored below the cutoff for at least one of the 5 domains. At 24 months, 7 (17.5%) gonadotropin, 9 (25.7%) clomiphene, and 5 (12.8%) letrozole children scored below at least one cutoff, and at 36 months, 1 (8.3%) gonadotropin, 6 (27.3%) clomiphene, and 5 (20.8%) letrozole children scored below at least one cutoff. There were no significant differences among the 3 groups with respect to these proportions at any time point.

Figure 1:

Boxplots of Ages and Stages Questionnaire by treatment group and timepoint in the registry. Solid green line indicates cutoff for abnormal scores (below the cutoff).

The MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory

Figure 2 shows the results of the MCDI by the conception drug used by the mother. For the Words and Gestures Questionnaire (panel 2A), the sample sizes were 52 for gonadotropin, 52 for clomiphene, and 45 for letrozole. Children in the letrozole group scored significantly higher than gonadotropin group for all items (phrases p=0.02, words understood p=0.04, words produced p=0.04, early gestures p=0.01, later gestures p<.001 and total gestures p<.001). Children in the clomiphene group also scored significantly higher than gonadotropin for the later gestures and total gestures items (p=0.04 for both) and scored significantly lower than letrozole for those same 2 items (p=0.02 and p=0.04, respectively). For the Words and Sentences Questionnaire (panel 2B), the sample sizes were 32 for gonadotropin, 27 for clomiphene, and 32 for letrozole. There were no significant differences among the 3 groups for any of the Words and Sentences items.

Figure 2:

Boxplots of percentiles for the 6 MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory Words and Gestures items (panel A) and 5 Words and Sentences items (panel B) by conception drug. Symbol (*) represents the model-based mean value.

Annual Growth

Figure 3 shows the annual growth of the children by conception drug and by sex (Female Panel A and Male Panel B). Given our limited growth data with weight being measured on an annual basis and diminishing rates of returned growth records over time (Supplemental Table 3), we provided these curves as a general growth guide but not as definitive growth curves for these populations. We found no significant differences in growth between the 3 groups at 12, 24, or 36 months for either gender.

Figure 3:

Growth curves calculated from the medical records plotted against the CDC mean, 25th and 75th percentile curves. Panel A are females, Panel B are males.

Hospitalizations and medical diagnoses of children participating in the Pregnancy Registry over the first 36 months are shown in Supplemental Table 4 and 5. Overall 11 children had hospitalizations for a variety of disorders, 2 of these children had multiple hospitalizations. Medical disorders were varied.

Effects of Multiple Pregnancy

In order to examine the possible confounding effects of multiple pregnancy, given the varying rates between treatments, we also performed the above analyses with singleton births only. As expected, multiples in each of the treatment groups had significantly lower birth weight than singletons (Supplemental Table 6). There were no significant differences with respect to abnormal ASQ scores on singletons only (data not shown but consistent with the full data). MCDI Words and Gestures showed significant differences for letrozole vs. gonadotropin singletons for just 3 items (early, late, and total gestures, data not shown) whereas with the full data as noted above, we found differences for all 6 items. There were no differences between clomiphene and gonadotropin singletons, or between clomiphene and letrozole singletons (data not shown), whereas there were a few differences noted on the full data as noted above. There were no differences in growth between the 3 groups when using singletons only (data not shown but consistent with the full data).

DISCUSSION

We report here the results of our pregnancy registry data collected from parents and their children conceived by commonly used medications for infertility treatment, i.e. clomiphene, letrozole and gonadotropins. This is one of the first pregnancy registries from multi-center randomized trials of infertility to report long term follow-up data on the children. This is primarily a descriptive study reporting data collected on a wide variety of developmental parameters as well as on growth and medical history of the children. Our findings generally are reassuring in that most children meet milestones, growth is normal with some catch up growth observed, serious medical disorders are relatively rare and common medical disorders, not surprisingly, common. Our findings are particularly novel in that there are very limited data on the potential effects of letrozole on child development.

Our study was limited by several factors. One is that we had a small starting sample size of live births and only a minority of potential children participated in the registry. As a comparator, the prospective cohort study UPSTATE Kids screened 5841 children, including 1830 conceived with infertility treatment and 2074 twins.(6) We studied only a tiny fraction in comparison. Although we consented a majority of subjects for the pregnancy registry, only 40% of eligible live-birth families actually participated in the follow up study. We did not survey patients who did not participate or who dropped out for other reasons, though when asked, it was both the burden of annual contacts combined with annual release of records that proved higher than we anticipated when designing the study. We were also limited by resources and personnel as the burden of following up on children went beyond the life cycle of the grant and coordinators and investigators had moved on to other positions. Thus, our results may not be generalizable to all subjects in our two infertility studies, let alone the larger population who conceive with these medications. Although we thought we designed it to have a low burden, the annual release of medical records and the administration of questionnaires did prove to be a hurdle for participation.

We report data from singleton and multiple pregnancies combined and do not correct the analysis for the adverse effects of multiple pregnancies and prematurity on our study’s collected outcomes. Prospective cohort studies such as the UPSTATE KIDS study corrected for this confounder in their analyses.(6) We did not perform similar corrections due to the small sample size of our cohort, the lack of a normal reference group, and because these data represent real life distributions that reflect the high number of multiple pregnancies and their associated sequelae attributable to gonadotropins. The higher rate of developmental delays noted in the gonadotropin arms on the ASQ arms versus for example the letrozole arms are likely directly related to the higher rate of multiple pregnancy and prematurity that occur in children conceived from gonadotropins compared with the lower rate of multiple pregnancies conceived with letrozole. Our combined studies as reflected in the published data and those who participated in the study shows multiples were highest with gonadotropin, followed by clomiphene followed by letrozole. Similarly, birthweight was lowest for similar reasons in the gonadotropin arms and children in this arm displayed catch up growth over the first three years. It is tempting to suppose that this pattern of catch up growth may predispose these children to later increased cardiovascular disease based on the developmental origins theories, i.e. the Barker hypothesis.(17) However we lack any data on cardiovascular risk factors and such suppositions are beyond the range of time and data collected. We also only had weight at birth plus the 3 yearly timepoints, with sparse data as time progressed, whereas the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) curves are based on continual monthly weights over the first 3 years. This is a limitation for our growth curves.

This registry was mandated by FDA and many of the parameters collected relate to concerns about the potential effects of letrozole on neurodevelopment. Specifically there were concerns that aromatase inhibition could potentially carry over and affect aromatase activity in the fetal brain during development.(18, 19) Our findings are reassuring in that language skills develop appropriately with no clear pattern of significance between treatment groups over time. Similarly, our rates for overall development as determined by the ASQ were comparable between groups as well as with the UPSTATE KIDS study.(6) That study did note higher failure and abnormal cutoff scores among children of multiple pregnancies, though there was no difference between twins conceived without treatment versus those with treatment. This study also had a formal clinical evaluation for developmental disorders of a subset of children at age 3 or 4 years and found the frequency of any disability did not differ by infertility treatment exposure (i.e. 18% of children without treatment had a disorder versus 13% of children conceived by infertility treatment). We did not have any formal evaluation of the children in our study.

Future lessons from this trial is the need to design pregnancy registries to increase enrollment and retention. One way would be to better justify the pregnancy registry to parents and design culturally appropriate study information. Another would be to incentivize patients to participate. Another would be to develop an infrastructure that can be maintained over time which may be more centrally located than at the individual institutions to allow continuity of contact over the infancy period. To increase comparability among studies developing a standardized protocol for infant screening similar to those that have been developed for infertility trials(20, 21) and pregnancy trials(22) would allow for synthesis and meta-analysis of results.

Supplementary Material

CAPSULE.

We report the 3 year developmental and neurodevelopmental data, growth and medical history data from a group of children conceived in two large infertility trials (PPCOS II and AMIGOS) with gonadotropin, clomiphene or letrozole.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCE

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Grants U10 HD27049 (to C.C.), U10 HD38992 (to R.S.L.), U10HD055925 (to H.Z.), U10 HD39005 (to M.P.D.), U10 HD38998 (to W.D.S), U10 HD055936 (to G.M.C.), U10 HD055942 (to R.G.B.), and U10 HD055944 (to P.R.C.); U54-HD29834 (to the University of Virginia Center for Research in Reproduction Ligand Assay and Analysis Core of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction and Infertility Research); General Clinical Research Center Grants MO1RR10732 and construction grant C06 RR016499 (to Pennsylvania State University). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Legro reports consulting fees from Ferring, Bayer, Abbvie and Fractyl and research sponsorship from Ferring and Guerbet. Dr. Schlaff reports research funding from Abbvie. Dr. Hansen reports research grants from Roche Diagnostics and Ferring outside of the submitted work. Dr. Diamond reports institutional grants/contracts from Bayer, ObsEva, and AbbVie; serving as a member of the Board of Directors and a stockholder of Advanced Reproductive Care; and serving as a Consultant for Seikagaku, Actamax, AEGEA, Temple Therapeutics, and ARC Medical Devices. Mr. Kunselman reports ownership of stock in Merck outside of the submitted work. Dr. Krawetz reports research grant from Merck outside of the submitted work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davies MJ, Moore VM, Willson KJ, Van Essen P, Priest K, Scott H, et al. Reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects. N Engl J Med 2012;366(19):1803–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonduelle M, Van Assche E, Joris H, Keymolen K, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem A, et al. Prenatal testing in ICSI pregnancies: incidence of chromosomal anomalies in 1586 karyotypes and relation to sperm parameters. Hum Reprod 2002;17(10):2600–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalra SK, Ratcliffe SJ, Coutifaris C, Molinaro T, Barnhart KT. Ovarian stimulation and low birth weight in newborns conceived through in vitro fertilization. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118(4): 863–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hediger ML, Bell EM, Druschel CM, Buck Louis GM. Assisted reproductive technologies and children’s neurodevelopmental outcomes. Fertil Steril 2013;99(2):311–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bay B, Mortensen EL, Hvidtjorn D, Kesmodel US. Fertility treatment and risk of childhood and adolescent mental disorders: register based cohort study. BMJ 2013;347:f3978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeung EH, Sundaram R, Bell EM, Druschel C, Kus C, Ghassabian A, et al. Examining Infertility Treatment and Early Childhood Development in the Upstate KIDS Study. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170(3):251–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, Coutifaris C, Schlaff W, Casson P, et al. Letrozole versus clomiphene for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014;371(2):119–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diamond MP, Legro RS, Coutifaris C, Alvero R, Robinson RD, Casson P, et al. Letrozole, Gonadotropin, or Clomiphene for Unexplained Infertility. N Engl J Med 2015;373(13):1230–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Legro RS, Kunselman AR, Brzyski RG, Casson PR, Diamond MP, Schlaff WD, et al. The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II (PPCOS II) trial: rationale and design of a double-blind randomized trial of clomiphene citrate and letrozole for the treatment of infertility in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Contemp Clin Trials 2012;33(3):470–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diamond MP, Mitwally M, Casper R, Ager J, Legro RS, Brzyski R, et al. Estimating rates of multiple gestation pregnancies: sample size calculation from the assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2011. ;32(6):902–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Legro RS, Brzyski RG, Diamond MP, Coutifaris C, Schlaff WD, Alvero R, et al. The Pregnancy in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome II study: baseline characteristics and effects of obesity from a multicenter randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril 2014;101(1):258–69 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diamond MP, Legro RS, Coutifaris C, Alvero R, Robinson RD, Casson P, et al. Assessment of multiple intrauterine gestations from ovarian stimulation (AMIGOS) trial: baseline characteristics. Fertil Steril 2015;103(4):962–73 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Squires J, Potter L, Bricker D. The ASQ User’s Guide. 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Northen AT, Norman GS, Anderson K, Moseley L, Divito M, Cotroneo M, et al. Follow-up of children exposed in utero to 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate compared with placebo. Obstet Gynecol 2007;110(4):865–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster-Cohen S, Edgin JO, Champion PR, Woodward LJ. Early delayed language development in very preterm infants: evidence from the MacArthur-Bates CDI. J Child Lang 2007;34(3):655–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heilmann J, Ellis Weismer S, Evans J, Hollar C. Utility of the MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventory in identifying language abilities of late-talking and typically developing toddlers. Am J Speech Lang Pathol 2005;14(1):40–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barker DJ, Gluckman PD, Godfrey KM, Harding JE, Owens JA, Robinson JS. Fetal nutrition and cardiovascular disease in adult life. Lancet 1993;341(8850):938–41. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morishima A, Grumbach MM, Simpson ER, Fisher C, Qin K. Aromatase deficiency in male and female siblings caused by a novel mutation and the physiological role of estrogens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80(12):3689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melcangi RC, Panzica G, Garcia-Segura LM. Neuroactive steroids: focus on human brain. Neuroscience 2011;191:1–5. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harbin Consensus Conference Workshop Group. Improving the Reporting of Clinical Trials of Infertility Treatments (IMPRINT): modifying the CONSORT statement. Fertil Steril 2014;102(4):952–59 e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harbin Consensus Conference Workshop Group. Legro RS, Wu X, Barnhart KT, Farquhar C, Fauser BC, Mol B, et al. Improving the reporting of clinical trials of infertility treatments (IMPRINT): modifying the CONSORT statement. Hum Reprod 2014;29(10):2075–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chauhan SP, Blackwell SC, Saade GR, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine Health Policy Committee. A suggested approach for implementing CONSORT guidelines specific to obstetric research. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122(5):952–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.