Abstract

Purpose

Improving access to care is an issue at the forefront of reproductive medicine. We sought to describe how one academic center, set in the background of a large and diverse metropolitan city, cares for patients with extremely limited access to reproductive specialists.

Methods

The NYU Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility (REI) Fellowship program provides a “fellow-run clinic” within Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital Center, which is led by the REI fellows and supervised by the REI attendings of the NYU Langone Health system. A description of the history of the hospital as well as the logistics of the fertility clinic is provided as a logistical template for implementation.

Results

The fellow-run fertility clinic at Bellevue hospital is held on two half days per month seeing approximately 150 new patients per year. The fertility workup, counseling, surgery, as well as ovulation induction, and early pregnancy management are offered within the construct of the fellowship and residency at NYU. Barriers to care and ways to circumvent those barriers are discussed in detail.

Conclusion

By utilizing the ambition and construct of the OB/GYN programs, we greatly improve care for an otherwise underserved patient population by offering an efficient and optimal infertility workup and treatment in a population that would otherwise be without care. We utilize the framework of graduate medical education to provide autonomy, experience, and mentorship to both residents and fellows in our programs in an effort to provide a solution to combating inequity in infertility care.

Keywords: Access to care, Infertility, Education, Public health

Introduction

In 2009, the World Health Organization recognized infertility as a disease. This designation revealed to a wider medical audience the reality that infertility, which affects 80–180 million people worldwide, is a major public health issue [1]. The USA alone has witnessed a 1% drop in the general fertility rate from 2014 to 2015—a new record low according to the CDC [1, 2]. In part, this shift is owing to a combination of societal shifts and changing ideals regarding family size. But there is no doubt that women are delaying childbearing and that age-related fertility decline is largely contributing to unintended childlessness [3]. While treatment and technology in the field of reproductive endocrinology and infertility and assisted reproduction continues to advance, access to this care can be limited or challenging. Results from the National Health Statistics Report that surveyed reproductive aged women between 2006 and 2010 showed that 7.3 million women had used fertility services, but that 62% of nulliparous women with fertility problems had never received care [4]. In this report, access to care was highest in older non-Hispanic white women, while minority groups were critically underserved. This disparity in access is reflected in the higher declines in general fertility rates seen between ethnic groups: general fertility rates declined < 1% among non-Hispanic white women, 1% for non-Hispanic black women, 1% for Hispanic women, 2% for American Indian or Alaskan Natives, and 4% for Asian or Pacific Islanders [2, 4]. While these declines are likely multifactorial, it is clear that ethnicity and socioeconomic status largely influence one’s ability to access fertility services [4].

Infertility is devastating for patients and families of all backgrounds, but it can have a particularly profound cultural impact in groups where childbearing is revered as the most important part of a relationship or as “one’s duty to God” [5]. Infertility carries a tremendous psychosocial burden, contributing to depression and anxiety with long-lasting effects on families and individuals. Women with infertility may perceive that they have a “loss of control over their life, a loss of identity or a feeling of defectiveness” [6], and stress from infertility has been associated with impaired marital function and decreased quality of life for both partners [7]. In fact, one study in China showed that divorce was twice as likely in couples with infertility [8] and that the effects of infertility exist across populations and cultures [9]. For these reasons and so many more, the psychosocial impacts of infertility are considerable.

Identifying barriers to treatment is a vital step in improving access to care. The cost of medical services and lack of insurance coverage represent an obvious and crushing barrier to care. A survey of patients performed in 2017 showed that most patients with infertility pay out of pocket and, at that time, only 15 states in the USA had state-based insurance coverage of fertility treatment [10]. Between 2006 and 2010, 5% of women with an income 400% above the poverty level received care compared with 1.9% of women below poverty level [4]. Education level similarly impacts one’s likelihood to seek care or one’s ability to navigate a complex medical system. In the same national survey of reproductive-aged women from 2006 to 2010, 5.8% of women with a Masters’ degree or higher received care compared with 0.8% of women who had less than a high school diploma or GED [4]. The survey did not consider the participant’s primary language, but we would expect that individuals who do not speak English as a first language would similarly have less access to care. Geographic barriers can make access to care physically difficult as most infertility services are located in large urban areas, limiting care for over 25 million women in the USA [11].

Improving access to care is an issue at the forefront of our field. In 2015, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) held an access to care summit as part of their strategic plan to tackle the issues and increase access [12]. States are actively working to pass legislation to improve insurance coverage for infertility services, but at this time, only 18 US states have infertility insurance laws [13]. Given the significant financial limitations experienced by patients, and particularly those who would not qualify for coverage even in states with mandated infertility coverage, a grass-roots approach may be necessary to provide care. One solution is the use of clinics designed specifically to provide affordable and effective care for infertile women from low-resource populations who would not otherwise have access. There are versions of clinics like these, often associated with academic institutions or universities across the USA that have been successful in providing such care [14]. Our fellowship program, situated in an academic center in New York City, has the unique perspective of caring for patients in both a private and public hospital setting. Our fellow-run clinic at Manhattan’s Bellevue Hospital provides care to a low-resource population in NYC, caring for a diverse population with extremely limited access to reproductive medicine care. Through a brief history of this clinic and a detailed explanation of how the clinic operates, we aim to provide a logistical template for others who may consider implementation of a similar system. We also show how these clinics provide not only necessary patient care but also critical educational opportunities for the resident and fellow physicians caring for patients.

Background on Bellevue Hospital

Bellevue Hospital has a storied past and is known as the “first” hospital in the USA with roots dating back to a small infirmary built in the 1660s [15]. Bellevue currently resides on the east side of Manhattan in a neighborhood known as Kips Bay, situated on a plot of land originally called Belle Vue Place bought in 1811. The hospital, officially named Bellevue Hospital in 1825, historically provided care to indigent populations and immigrants, and, by the time of the Civil War, it was the nation’s largest hospital [15, 16]. Bellevue Hospital has seen every disease and endured every outbreak, treating the influx of new pathogens brought by immigrants arriving in boats from distant countries. The dedicated healthcare teams provided care to more patients with AIDS than at any other hospital in the USA beginning during the AIDS crisis, and, more recently, treating New York’s only Ebola victim who was successfully cured at Bellevue Hospital [15]. Over the years, Bellevue has had many large New York medical institutions provide care, but since 1968, care has been solely provided by the doctors of the NYU Langone Health institution since 1968. Today, Bellevue ranks as the fourth largest hospital in America [12].

Bellevue is the referral center for the entire New York City Health and Hospitals (HHC) Corporation and has a 25-story patient care facility, 6 intensive care units, a world-renowned emergency and trauma service, and a six-story ambulatory care pavilion [17]. The patient population at Bellevue corresponds with the diversity of New York City. There are more than 100 languages spoken, the most common being Spanish, Mandarin, Cantonese, Polish, Bengali, French, and Haitian Creole, and there is an interpreter phone at every bedside and in every clinic room [15]. In part because most patients are immigrants, most of Bellevue’s patient population is not covered by insurance [15].

The Women’s Health ambulatory care clinic encompasses an entire floor of the ambulatory care pavilion and roughly, 30,000 patients are seen for Women’s health (OB and GYN) clinic visits every year. The clinic offers comprehensive care including prenatal care, ultrasound services, postpartum care, family planning/abortion/contraception care, gynecologic services, gynecologic oncology services, reproductive endocrinology and infertility, and high-risk maternal fetal medicine. The clinic is staffed by residents and fellows from the NYU School of Medicine and nurse practitioners, who practice under the supervision of attending physicians from NYU Langone Health. Bellevue hospital represents an important safety net for the larger NYC population, providing state-of-the-art care to patients with very limited resources.

The Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility clinic

The reproductive endocrinology and infertility (REI) clinic at Bellevue started seeing patients in the mid-1990s, seeing approximately 150 new patients per year. Half-day clinics are held bi-monthly, with 6–7 new and 3–4 follow-up patients seen per clinic. Patient demographics are overall representative of the HHC population itself, with an average age at first visit of 32 (range 20–46), an average time trying to conceive of 4.5 years (range 4 months–17 years) and the majority identifying as Hispanic [18]. The most common infertility diagnoses include diminished ovarian reserve, endometriosis, male factor, and ovulatory dysfunction including PCOS, tubal factor, uterine factor, and unexplained infertility [18].

Patients seeking access to infertility treatment experience many barriers to care within the HHC system. Given limitations in staffing, space, and allotted clinic time, the wait time to schedule a new patient visit is approximately 6 months. Patients who miss these appointments or need to reschedule have difficulty navigating the phone system, and language barriers make scheduling appointments over the phone challenging. New appointments are opened up every 6 months and fill up within a few days from the waiting list. Some patients unfortunately may eventually give up trying to get an appointment and are, therefore, never seen nor treated.

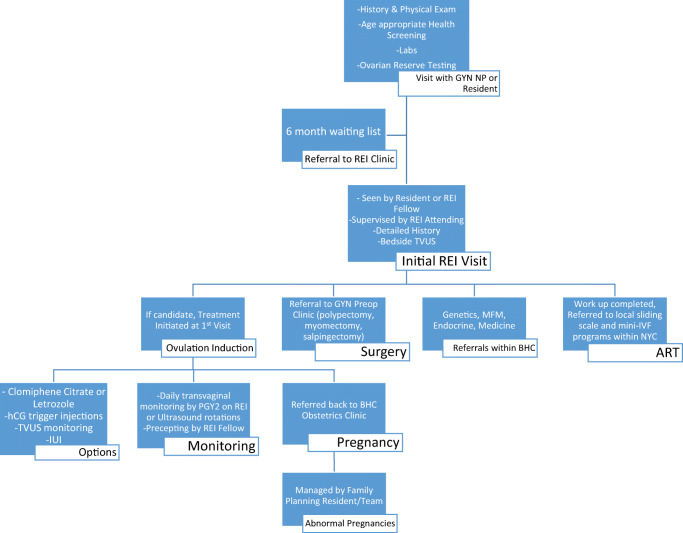

Patients who are able to schedule appointments through the system are typically seen within a few months by a midlevel provider in the gynecology clinic who takes a general history and performs a physical exam. Figure 1 depicts the overall general pathway through the Bellevue REI clinic. Providers make sure patients are up to date on age-appropriate general health screening such as cervical cancer screening, sexually transmitted infection testing, and mammograms. Routine baseline laboratory testing is obtained prior to the patient being seen by a specialist. This includes TSH, prolactin, day 2 estradiol and FSH, and AMH. At the first visit in REI clinic, a detailed fertility history is obtained as well as the partner’s history. A bedside transvaginal ultrasound is performed to determine the antral follicle count and note any gross uterine abnormalities such as fibroids. Additional testing is ordered as indicated.

Fig. 1.

Pathway of care in Bellevue REI Clinic

Treatments are often initiated at the first visit due to the scarcity of follow-up clinic appointments and resulting high loss to follow-up rate. Additionally, many patients are referred for in vitro fertilization (IVF) at the first visit due to diminished ovarian reserve or known tubal factor infertility. Most of these patients cannot afford IVF, and the vast majority of clinic patients are uninsured or underinsured. Information is given for many private centers throughout the city that offer payment plans or mini-IVF, which may be more affordable. Data on the rate of contact to these centers and/or the rate of cycle start or completion is not available. It is important to note that the New York State legislature passed a bill in March 2019 mandating coverage for fertility preservation as well as approved an expansion of IVF coverage in the 2020 NY state budget for all large group employers. To be sure, the mandate will improve coverage and impact many. However, it also specifically excludes those with Medicaid who will remain without fertility coverage. While most Bellevue patients will likely not qualify for coverage, should they be eligible, they would be referred for IVF with the pre-requisite testing completed at Bellevue. Patients also seek out options for IVF in other countries where ART may be more affordable. Adoption is also discussed. For many patients, this marks the end of a long road in their search for answers to their infertility and in their hopes to have children. Although the news may be devastating, patients appreciate having an explanation as to the cause of infertility and closure.

Navigating an infertility workup and treatment in a low-resource setting

The patients seen at the Bellevue REI clinic are among the most highly motivated patients in seeking infertility care for personal and often cultural reasons. Despite their dedication and perseverance, the barriers to care are often insurmountable. In Table 1, we demonstrate a list of some of the more common barriers often seen in a low-resource setting and how they are addressed or circumvented in Bellevue’s REI clinic. A few of the significant hurdles are discussed in more detail here.

Table 1.

Common barriers to care and solutions in place at Bellevue Hospital

| Barrier | Solution |

|---|---|

| Language | Language line offering telephone translation services in > 100 languages, 24 h day/7 days a week. Also includes American sign language and face-to-face interpretation |

| - > 100 number of languages spoken at Bellevue | |

| Cost | - Sliding scale pricing for HSG |

| - HSG cost $290–700 | - Patient-friendly management – HSG only performed in the context of unexplained infertility or 3 failed OI cycles among anovulatory patients |

| - Outside referral for competitively-priced HSG | |

| - IUI cost $100 | - IUI semen wash performed at reduced cost; first IUI wash often also utilized as initial SA |

| Ovulation induction monitoring | - Clinic Team Approach: Performed by OB/GYN residents and faculty either in clinic (weekdays) or on labor and delivery (weekends) |

| - New resident continuity approach: dedicated ultrasound room for daily drop in monitoring, 2 h daily (7 days/week), REI resident on rotation M-F, OBGYN call team on weekends. Remote REI fellow precepting | |

| - Same day endocrine monitoring reserved only for special circumstances | |

| No access to ART through Bellevue hospital | - Referral to local centers with sliding scale IVF programs or low-cost IVF |

| - Perform all bloodwork, imaging and testing required for ART at HHC prior to referral | |

| - Same options for fertility preservation patients | |

| Preconception carrier screening | - Limit testing to ACOG recommended testing |

The majority of new patients at Bellevue are treated initially with ovulation induction with either clomiphene citrate or letrozole. Our clinic has not seen any cases of ovarian hyperstimulation due to clomiphene citrate or letrozole and utilizes the residents to offer 7 days/week daily ultrasound monitoring. Prior to July 2018, ultrasound follicular monitoring was performed by residents during clinic hours as drop in visits and on the weekends in the hospital by the call team. Same-day endocrine labs are not available in this setting. Despite the lack of laboratory evaluation, follicular monitoring is important in order to identify the large subset of PCOS patients who do not respond to initial doses of medications. A large portion of patients are lost to follow-up due to lack of compliance, the time requirement for follicular monitoring, or the difficulties with scheduling follow-up appointments. Therefore, in July 2018, a new system was implemented where the 2nd year resident on alternating REI or ultrasound rotations holds a 2-h dedicated ultrasound monitoring session on M–F, and the call team maintains these same hours on labor and delivery on the weekends. Same day endocrine bloods are not routinely performed but can be sent from the hospital if needed in unique cases. The residents who perform the ultrasounds are precepted remotely by an REI fellow with attending supervision to maintain continuity within the clinic.

The cost of the infertility workup can also be prohibitive. At Bellevue, a hysterosalpingography (HSG) and semen analyses (SA) are ordered on every patient with unexplained infertility at the first visit. Treatment is initiated prior to obtaining these studies in most cases because appointments can take up to 3 months, and patients have difficulty paying for the testing. For patients with ovulatory dysfunction, a HSG is ordered only after three failed cycles of ovulation induction. At Bellevue, the cost of a HSG is on a sliding scale ranging from $290 to 700, but patients are often referred elsewhere in Manhattan for less expensive HSG testing. Intrauterine inseminations (IUI) are offered to patients with unexplained infertility at a cost of $100 for sperm wash at a private laboratory three blocks away. When IUI is indicated, patients bring post-wash specimens back to Bellevue from the outside private laboratory where IUI is performed by the PGY-2 resident doing monitoring during the week and by a member of the OBGYN call team on weekends. Patients must also pay for hCG trigger injections, which cost $80–100 per cycle. However, for those with Medicaid, an hCG trigger injection at Bellevue is $2. The expenses are burdensome and account for some of the patients lost to follow up.

Patients with uterine structural abnormalities such as polyps, fibroids, or unilateral hydrosalpinges may benefit greatly from surgical interventions. Patients can obtain a saline infusion sonogram within a month to identify submucosal lesions, and hysteroscopic resection is readily available. If surgery is indicated, coordination of care for additional interventions, such as laparoscopic chromoperturbation, are often planned concurrently as it is sometimes cheaper than a second procedure even for patients paying for surgery out of pocket. Each surgical patient is counseled by the REI provider team as well as a finance team member to confirm the optimal surgical plan.

Within the Women’s Health clinic, there is also a prenatal genetics clinic held once a week. The clinic is optimized to see both (1) women with high-risk pregnancies requiring genetic counseling for pre/post amniocentesis and (2) referrals for recurrent pregnancy loss. In each visit, we discuss karyotype testing and the implications for future management are individualized for each patient. Often for financial reasons, only one patient, usually the female, has the karyotype drawn in the first instance. We then await results prior to testing the partner. The genetic counselors who run this clinic are immensely helpful and provide a continuity of care for those women who do get pregnant. Later in this process, successful early pregnancies are referred back to the prenatal care system within the Bellevue Women’s Health service. For those pregnancies of unknown location, abnormal intrauterine pregnancies and confirmed ectopic pregnancies are managed by the reproductive choice (RC) service. This service is run by the family planning faculty of the NYU OBGYN department in conjunction with the residents on rotation. Medical terminations, manual assisted evacuations, D&Cs, D&Es, and methotrexate are offered to appropriate patients with the associated counseling and follow-up.

Resident and fellow roles in provision of care

Expanding access to care must begin with resident and fellow education, as trainees must learn appropriate management in order to best care for future infertility patients. Unfortunately, clinical exposure to reproductive endocrinology is extremely limited in most OB/GYN residency programs. Most residents receive only 3–5 weeks on a single REI rotation within a 4-year residency. Nationwide, residents’ low CREOG scores on the REI portion highlight the disparity of training [19]. To address the paucity of exposure, we must develop unique and creative curriculums designed to engage the resident and promote active learning objectives to increase educational retention, such as with case-based learning or interactive simulation [20]. Given the prevalence of infertility, and the many barriers faced by patients requiring reproductive medicine care, all graduates of OB/GYN residencies (and particularly those practicing general OB/GYN) should develop comfort with conducting the initial workup and management of infertility. This includes learning how to manage an ovulation induction cycle, which is a core foundational skill learned by trainees managing OI cycles at Bellevue. This training, therefore, must occur as part of resident education and is best learned in a setting of supervised autonomy.

There is an important role for counseling in the prevention of infertility, particularly among patients who may have difficulty accessing ART in the future. This preventive care should be emphasized as part of resident and fellow education. It is well known that many women with ovulatory dysfunction or PCOS may have concomitant obesity and insulin resistance/diabetes. Dietary changes and weight loss can increase the chances of spontaneous ovulation and increase fecundity, while also decreasing the risk of obstetric co-morbidities including gestational diabetes, pregnancy induced hypertension, large for gestational age infants, and cesarean section. Reproductive age women undergoing routine well woman visits with their OB/GYN should be counseled about the impacts of obesity and diabetes on fertility, and these counseling skills are learned only through extensive counseling opportunities during training. Beyond diet and exercise counseling, screening for sexually transmitted infections and pelvic inflammatory disease should be routinely performed. Prompt detection and treatment of pelvic infections can prevent tubal disease and resultant infertility. Patients should be counseled about the prevention of pelvic infections and the risk of infertility. Women with a known history of pelvic infections should undergo a HSG as part of their initial infertility workup to identify tubal disease. Surgical options for lysis of adhesions or salpingectomy in the case of a hydrosalpinx may be available when IVF is not.

Residents and fellows learn a tremendous amount regarding prevention, workup, and management of infertility by autonomously caring for patients under direct supervision. There exists an age-old tension within graduate medical education between educating trainees and ensuring appropriate supervision, and this balance is well-achieved within the reproductive medicine clinic and throughout Bellevue hospital.

Additionally, fellowship programs across the country differ dramatically in training experience. Select programs have fellows see and manage patients autonomously, with indirect supervision, whereas others will graduate fellows without ever having managed a patient independently. Moreover, patient populations vary greatly between hospitals within the same city and even more so across the country meaning fellows also graduate with a wide discrepancy in exposure to infertility pathology and management. As a result of this inconsistency in exposure, fellows leave training with a wide range of experience and clinical skills. The ability to manage and have the responsibility for autonomous practice of patient care is critical to fellowship education. A clinic like Bellevue’s REI clinic has an optimal setup for exposure and autonomy for fellows as well as experience and education for residents side by side.

Discussion

It simply cannot be overstated; infertility is a major public health issue and now is the time for action and for finding creative means to increase access to care. The millions of people affected by infertility [1] span the globe, in both developed and developing countries alike [21]. The prohibitive patient factors, such as cost, religious influence, cultural, and/or legal regulations, may balance differently by location, but the sequelae of infertility, isolation, abandonment, and even violence or suicide remain the same for all those affected [22]. There is also a challenging balance that some centers may face when trying to optimize patients’ success rates while knowingly utilizing measures that may result in suboptimal outcomes within the constraints of what treatments are feasible. We applaud the innovative and low-cost solutions that are growing in number and in utilization. The REI fellowship program at the University of California—San Francisco implemented a low-cost IVF program at significantly reduced cost and provided safe and effective care in a low-resource setting with clinically significant pregnancy rates [23]. Numerous modifications to infertility care, and specifically assisted reproductive technology (ART), have been proposed to expand access to care [24, 25] which includes several technological advances with vaginal incubators [26] to help ease the cost of the embryology laboratory. In fact, organizations, such as the Walking Egg, have been founded with sole focus to develop and implement solutions to offer fertility and ART care in low resource settings across the world [27]. Each and every development that expands care and advances reproductive options is crucial to confronting the infertility access crisis.

However, increasing access to infertility care is a complex process balancing delicately on the ethical principle of justice. Offering limited or modified healthcare in places with nothing can be considered both just (something > nothing) and unjust (everything > something = nothing), leading to the concept of two standards of care [28]. Inequities are magnified when there is a treatment or option that exists but is not available simply due to location or resource. For those with no options and nowhere to turn, however, offering any alternative is certainly better than none. Furthermore, for some patients, this care may be the only medical attention that is sought out that may lead to overall better healthcare and diagnosis of underlying medical conditions, especially in men where even in resource-rich areas medical care is not often a priority [29]. So while increasing access to care may be a tricky process in low-resource areas and with vulnerable populations, it should not ethically preclude that care from being offered.

Unfortunately, despite these improvements, there is still an enormous percentage of the population without any access to care or with access to care riddled by long wait times, compliance issues, or limited treatment options. As mentioned, there are currently only 18 states with active mandates for insurance coverage for infertility [13]. Moreover, while these new mandates continue to improve care for some, the seemingly insurmountable barriers faced by the uninsured and the underinsured patients will persist. Table 2 lists the current pathways to access care and highlights how limited these options are. Although other states are actively working to pass legislation, there are still large numbers of patients without access to care even in presently mandated states. In fact, the USA has the highest cost for ART and the lowest utilization [30]. Even across the globe, it is estimated that only half of couples who meet criteria for primary infertility will seek medical care [31]. There are programs such as grant and scholarship programs, through public opportunities at the state and local level as well as private programs that help fund couples to gain access to ART to begin to address this gap. However, often the requirements for eligibility to even apply for these programs require established care with an REI, which many never be accomplished to begin with. The bottom line is that we need more solutions to address the problem with access to infertility care, but in the absence of the “perfect” answer, some is better than none.

Table 2.

Current pathways for access to infertility care

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Insurance coverage | -Trend towards increasing coverage among insurance plans | -State limitations |

| -Institution of state mandates increasing coverage | -Requirements and/or pre-authorizations before certain tests or treatment | |

| Public hospitals | -Offers workup and treatment to otherwise unserved population | -Often limited reimbursement to providers/clinic/hospital limiting feasibility |

| -Limited care | ||

| Foundation grants and scholarships | -Patient can access treatment for low/no cost | -Requires paperwork and navigation of submission system |

| -Many programs in place | -Not guaranteed, few of those who apply receive funds | |

| Fertility financing programs | -Often lower interest rates than other financing programs | -High cost of care remains unchanged |

| Sliding scale clinics, mini-IVF | -Lower cost treatment | -Not available at all centers |

| -Not all patients are candidates for mini-IVF | ||

| -Remains expensive |

Here, we describe our efforts to provide access to care for the underserved through the use of the Bellevue REI clinic. By utilizing the ambition and brain power of an OB/GYN residency and an REI fellowship, we greatly improve care for an otherwise underserved patient population. We provide efficient and optimal infertility workup and treatment, monitored ovulation induction with intrauterine insemination, and organized and effective referral for ART. Moreover, we utilize the framework of graduate medical education to provide autonomy, experience, and mentorship to both residents and fellows in our programs. These efforts are our solution to combating inequity in infertility care, and we offer our template for others seeking to do the same.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients and staff at the Bellevue Hospital Center.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution.

Informed consent

There were no human subjects as part of this manuscript and therefore no need for informed consent.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nachtigall RD. International disparities in access to infertility services. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:871–875. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK & Mathews TJ. Births: final data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2017; 66(1): 1–69. Accessed May 20th, 2018. [PubMed]

- 3.ASRM Committee Opinion #589 Female age-related fertility decline. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):633–634. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandra A, Copen CE, Stephen EH. Infertility service use in the United States: data from the national survey of family growth 1982–2010. National Health Statistics Report. 2014. [PubMed]

- 5.Becker G, Castrillo M, Jackson R, Nachtigall RD. Infertility among low-income Latinos. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deka P, Sarma S. Psychological aspects of infertility. Br J Med Pract. 2010;3:a336. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrew FM, Abbey A, Halman LJ. Is fertility-problem stress different? The dynamics of stress in fertile and infertile couples. Fertility and Sterility. 1992;57:1247–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)55082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luk BH, Loke AY. The impact of infertility on the psychological well-being, marital relationships, sexual relationships, quality of life of couples: a systematic review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;41(6):610–625. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2014.958789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Che Y, Cleland J. Infertility in Shanghai: prevalence, treatment seeking and impact. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;22:643–648. doi: 10.1080/0144361021000020457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reproductive Medicine Associate of New Jersey. Trends in infertility 2017: Survey and Report. Accessed June 6th, 2018.

- 11.Harris JA, Menke MN, Haefner JK, Moniz MH, Perumalswami CR. Geographic access to assisted reproductive technology health care in the United States: a population-based cross-sectional study. Fertil Steril. 2017;107(4):1023–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.02.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reindollar RH. Increasing access to infertility care – what will it take? Fertil Steril. 2017;108(4):600–601. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.https://www.reproductivefacts.org/resources/state-infertility-insurance-laws/?_ga=2.10876404.1736123632.1534617281-26038372.1532203552. Accessed January 19th, 2020.

- 14.Herndon CN, Anaya Y, Noel M, Cakmak H, Cedars MI. Outcomes from a university-based low-cost in vitro fertilization program providing access to care for a low-resource socioculturally diverse urban community. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(4):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oshinsky D. Bellevue: three centuries of medicine and mayhem at America’s most storied hospital: Doubleday Press; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Gold D. Bellevue: a documentary of a large metropolitan hospital. New York: Harper & Row. 1975; p. 409.

- 17.Nychealthandhospitals.org. Accessed May 20th, 2018.

- 18.Knopman JM, Talebian S, Fino ME, Kump L, Quagliarello J, Keegan DA. Fertility treatment in a public health care system in New York City: a description of Bellevue Hospital Center (BHC) reproductive endocrinology and infertility (REI) clinic. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:S153. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.07.293. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holzman GB, Downing SM, Power ML, Williams SB, Carpentieri A, Schulkin J. Resident performance on the council on resident education in obstetrics and gynecology (CREOG) in-training examinations: years 1996-2002. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:359–363. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman KN, Tiegs AW, Uquillas K, Nachtigall M, Fino ME, Winkel AF, Lerner V. Interactive case-based learning improves resident knowledge and confidence in reproductive endocrinology and infertility. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2017;33(6):496–499. doi: 10.1080/09513590.2017.1290075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ombelet W, Campo R. Affordable IVF for developing countries. Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;15(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/S1472-6483(10)60337-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ombelet W. Reproductive healthcare systems should include accessible infertility diagnosis and treatment: an important challenge for resource-poor countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2009;106(2):168–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herndon CN, Anaya Y, Noel M, Cakmak H, Cedars MI. Outcomes from a university-based low-cost in vitro fertilization program providing access to care for a low-resource socioculturally diverse urban community. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(4):642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paulson RJ, Fauser BCJM, Vuong LTN, Doody K. Can we modify assisted reproductive technology practice to broaden reproductive care access? Fertil Steril. 2016;105(5):1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Infertility care around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technolgoies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21(4):411–426. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doody KJ, Broome EJ, Doody KM. Comparing blastocyst quality and live birth rates of intravaginal culture using INVOcell to traditional in vitro incubation in a randomized open-label prospective controlled trial. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33(4):495–500. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0661-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ombelet W. Is global access to infertility care realistic? The walking egg project. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;28:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Inhorn MC, Patrizio P. Is lower quality clinical care ethically justifiable for patients residing in areas with infrastructure deficits? AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(3):228–237. doi: 10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.3.ecas1-1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inhorn MC. The new Arab man: emergent masculinities, technologies, and Islam in the Middle East. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chambers GM, Sullivan EA, Ishihara O, Chapman MG, Adamson GD. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2281–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boivin J, Buting L, Collins JA, et al. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(6):1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]