Abstract

Many autistic people are motivated to have friends, relationships and close family bonds, despite the clinical characterisation of autism as a condition negatively affecting social interaction. Many first-hand accounts of autistic people describe feelings of comfort and ease specifically with other autistic people. This qualitative research explored and contrasted autistic experiences of spending social time with neurotypical and autistic friends and family. In total, 12 autistic adults (10 females, aged 21–51) completed semi-structured interviews focused on time spent with friends and family; positive and negative aspects of time spent with neurotypical and autistic friends and family; and feelings during and after spending time together. Three themes were identified: cross-neurotype understanding, minority status and belonging. Investigation of these themes reveals the benefits of autistic people creating and maintaining social relationships with other autistic people, in a more systematic way than previous individual reports. They highlight the need for autistic-led social opportunities and indicate benefits of informal peer support for autistic adults.

Lay abstract

Although autistic people may struggle to interact with others, many autistic people have said they find interacting with other autistic people more comfortable. To find out whether this was a common experience, we did hour-long interviews with 12 autistic adults. We asked them questions about how it feels when spending time with their friends and family, and whether it felt different depending on whether the friends and family were autistic or neurotypical. We analysed the interviews and found three common themes in what our participants said. First, they found spending with other autistic people easier and more comfortable than spending time with neurotypical people, and felt they were better understood by other autistic people. Second, autistic people often felt they were in a social minority, and in order to spend time with neurotypical friends and family, they had to conform with what the neurotypical people wanted and were used to. Third, autistic people felt like they belonged with other autistic people and that they could be themselves around them. These findings show that having time with autistic friends and family can be very beneficial for autistic people and played an important role in a happy social life.

Keywords: autism, mental health, neurodiversity, peer support, social interaction

Introduction

Despite differences in social interaction, autistic people do not necessarily differ from their neurotypical peers in their desire for social relationships (Bauminger & Kasari, 2000; Cresswell et al., 2019). Many autistic people are motivated to have friendships and sustain meaningful and lasting social relationships (Bargiela et al., 2016; Daniel & Billingsley, 2010; Sedgewick, Crane, Hill, & Pellicano, 2019; Sinclair, 2010). However, initiating, maintaining and navigating these relationships may be difficult for autistic people, due to differences in autistic social cognition. These social cognitive differences may include difficulties in interpreting social cues (Morrison et al., 2019) and social reciprocity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), understanding the mental states of others (Frith & Happé, 1994), identifying basic and complex facial emotions (Baron-Cohen et al., 1997) and identifying tone of voice (Rutherford et al., 2002), sarcasm (Persicke et al., 2013) and social faux pas (Baron-Cohen et al., 1999). Autistic people tend to have fewer friendships than their neurotypical peers, and autistic relationships may have less reciprocity, and centre around activities rather than emotional bonding (Orsmond et al., 2004, 2013; Petrina et al., 2014). Autistic people may also value more time either alone or in smaller social groups (Calder et al., 2013). Although some recent research has qualitatively explored autistic people’s friendships from their own perspective (e.g. Sedgewick, Crane et al., 2019; Sedgewick, Hill & Pellicano, 2019), little is known about whether autistic people experience self-reported differences in relationships with autistic and non-autistic people.

Relationships and social connectivity play an important role in physical and psychological well-being (Cohen, 2004; House et al., 1988; Kawachi & Berkman, 2001). Relationships are also important for autistic well-being; autistic loneliness is related to poor mental health, including increased depression and anxiety (Mazurek, 2014), self-harm (Hedley et al., 2018) and suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2018). Close relationships with others give autistic people a space to experience emotional reciprocity, to express their emotions, exchange ideas, collaborate and cooperate, and practise interpersonal skills (Cresswell et al., 2019).

However, time with others might not always be positive for autistic people. Recently, research has focused on how many autistic people use compensatory strategies to mask their overtly autistic behaviours when spending time with others, thus allowing them to fit into their social surroundings (Bargiela et al., 2016; Lai et al., 2017; Leedham et al., 2020; Livingston et al., 2019). This ‘camouflaging’ of autistic traits may be motivated by a desire to make friends (Tierney et al., 2016) and often involves the autistic person effortfully adopting a constructed, neurotypical persona in order to seem socially competent and confident around peers (Hull et al., 2017). The aim of camouflaging is to fit in with the neurotypical people around you, not raise concerns of peers, and can result in what appears at surface level to be ‘successful’ social functioning. Camouflaging requires a prolonged and fatiguing effort for autistic people (Bargiela et al., 2016; Hull et al., 2017). Sustained autistic camouflaging is related to significant mental distress, including depression (Cage et al., 2018), and increased suicidality (Cassidy et al., 2018), with particularly high associations to mental health difficulties when switching between camouflaging in multiple contexts (Cage & Troxell-Whitman, 2019). This significant relationship between camouflaging and mental distress is of particular importance given the high rates of mental illness in the autistic population, with studies finding 77% and 79% of autistic adults also having diagnosable mental health conditions (Eaves & Ho, 2008; Lever & Geurts, 2016).

There is an emerging literature highlighting feelings of ease and comfort with other autistic people (Sinclair, 2010), and a supporting theoretical model termed the ‘double-empathy problem’ (Milton, 2012; Milton et al., 2018). The double-empathy problem states that when people with very different experiences of the world (such as a neurotypical person and an autistic person) interact with each other, they will struggle to empathise with one another. Communication may break down due to differences in language and comprehension, but importantly, this is as a result of a bidirectional difficulty rather than a specific deficit on the part of the autistic person (Milton et al., 2018). Autistic people have written autobiographical accounts of feeling more comfortable with other autistic people than with non-autistic people (Sinclair, 2010). New empirical research that directly compares how autistic and neurotypical people exchange information using a diffusion chain paradigm demonstrates that autistic people transfer information more efficiently with other autistic people than with neurotypical people, and additionally experience higher interactional rapport when with other autistic people (Crompton & Fletcher-Watson, 2019). In addition, some emerging quantitative research has highlighted the role that a lack of understanding from neurotypical people plays in the social interaction experiences of autistic people; neurotypical people are less willing to interact with autistic people (Sasson et al., 2017), overestimate how helpful they are towards autistic people (Heasman & Gillespie, 2019) and struggle to interpret autistic people’s mental states and social cues (Edey et al., 2016; Sheppard et al., 2016). Autistic adults have reflected that during their school years, they felt significantly better understood by their autistic peers than their non-autistic classmates (Macmillan et al., 2019).

There is, however, a lack of research investigating autistic experiences of spending time with autistic friends and family members, and asking whether there are subjective differences compared with interactions with neurotypical friends and family. Given that camouflaging is driven by a desire to fit in with a neurotypical social world, it is also important to examine whether autistic people feel required to camouflage when around other autistic people, and how that may influence their experience of spending time with others. In this study, we use a qualitative methodology to explore the lived experience of autistic people, and improve understanding of behaviours by providing insight into the subjective ‘autistic experience’ (Robertson et al., 2018).

Methods

Methodological approach

This study adopted a qualitative design, using semi-structured interviews analysed thematically. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Edinburgh Psychology Research Ethics Committee.

Participants

Participants were 12 autistic adults (see Table 1 for demographic information), who met the following eligibility criteria: (1) aged over 18, (2) clinically diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder by a certified professional, (3) spoke fluent English, (4) without a diagnosis of Social Anxiety Disorder and (5) without an intellectual disability, as indicated by an IQ of below 70. Participants were recruited online through social media including Twitter, through our project website and through local autism organisations, and were all UK based. Participants had a mean age of 33.58 (standard deviation (SD) = 10.06), on average 18 years of education (SD = 2.15), had a mean IQ of 116.92 (SD = 15.51) and mean autism quotient (AQ) score of 33.58 (SD = 7.32). The large majority of participants were female. A number code was generated for each participant, and identifying details redacted from reported quotes.

Table 1.

Participant demographic information.

| Participant ID | Age | Gender | Age of autism diagnosis | IQa | AQb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 21 | Female | 16 | 103 | 25 |

| 2 | 24 | Female | 18 | 140 | 38 |

| 3 | 46 | Female | 46 | 111 | 46 |

| 4 | 42 | Male | 40 | 102 | 38 |

| 5 | 21 | Female | 6 | 99 | 25 |

| 6 | 26 | Female | 26 | 114 | 33 |

| 7 | 33 | Female | 31 | 139 | 47 |

| 8 | 34 | Female | 33 | 135 | 36 |

| 9 | 36 | Female | 32 | 123 | 42 |

| 10 | 42 | Female | 42 | 104 | 31 |

| 11 | 51 | Female | 49 | 129 | 29 |

| 12 | 27 | Male | 5 | 104 | 37 |

AQ: autism quotient; WASI-II: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence–II.

IQ as assessed by the WASI-II.

AQ score.

Procedure

All participants provided written informed consent before taking part in the study. Interviews were conducted by the first author either face-to-face, over the phone or via videoconferences depending on the preference of the participant. All participants completed measures of IQ and autistic traits with a research assistant in a prior research session approximately 1 week before their interview (Crompton & Fletcher-Watson, 2019).

Before starting the interview, participants were informed that (1) they could ask for a break at any time for any reason, (2) they did not have to talk about anything they did not want to talk about and (3) if they wanted to talk about something in more detail, they could ask to go back to a question or answer it in more detail.

Measures

Semi-structured interview

Data were collected using a semi-structured interview schedule specifically developed for this study by the research team in consultation with autistic collaborators. A semi-structured approach is designed to be used flexibly and allows the interviewer to explore a participant’s line of response, probing ambiguities and allowing researchers to validate the meaning of participants’ answers (Barriball & While, 1994). We scoped the literature and found no pre-existing schedules that were suitable for our questions. This research closely targeted the question of how autistic people experienced autistic and non-autistic interactions with both autistic and neurotypical people. Wording was designed to be neutral and not leading, and wording was reviewed with autistic people to make it accessible. The interview first explored autistic adults’ relationships and social experiences with important non-autistic people in their lives, before exploring their relationships with the important autistic people in their lives. In the final four questions, participants were shown a quote, taken from Savarese (2009) and Sinclair (2010), and asked for their thoughts about it. The purpose of this was to introduce more controversial ideas without asking leading questions and to embed autistic writing and perspectives into the interview (Tsai et al., 2018). By using published quotes, we separated the opinions in them from what the researcher thought, decreasing the chances that the respondent felt they ought to respond in a particular way. The interview schedule is in Table 2. In each case, ‘person X’ referred to in the interview was identified and defined by the participant in the initial introductory questions (Questions 1 and 9), and was either an individual person or a group of people who the participant spent a significant amount of time with on a regular basis.

Table 2.

Semi-structured interview schedule.

| Question number | Question |

|---|---|

| We are going to start by talking about the people you spend time with who are not autistic | |

| 1 | Who are the non-autistic people you spend time with? |

| 2a/b/c | How do you know them? When and how did you meet? |

| 3 | What kind of things do you do together? |

| 4 | Now, let’s focus on person X. Can you tell me some of the good things about spending time with this person? |

| 5 | Can you tell me about some of the difficult things or challenges about spending time with this person? |

| 6a/b | How do you feel when you are with them? Why do you think you feel like that? |

| 7a/b | How do you feel after spending time with them? Why do you think you feel like that? |

| 8 | Is there anything else you want to tell me about how you relate to the non-autistic people in your life? |

| Now, we’re going to talk about the autistic people in your life | |

| 9a/b | Do you know any autistic people? Who are the autistic people you spend time with? |

| 10a/b/c | How do you know them? When and how did you meet? |

| 11 | What kind of things do you do together? |

| 12 | Now, let’s focus on person X. Can you tell me some of the good things about spending time with this person? |

| 13 | Can you tell me about some of the difficult things or challenges about spending time with this person? |

| 14a/b | How do you feel when you are with them? Why do you think you feel like that? |

| 15a/b | How do you feel after spending time with them? Why do you think you feel like that? |

| 16 | Is there anything else you want to tell me about how you relate to the autistic people in your life? |

| I am now going to show and read you four statements, one at a time. I will ask you what you think about each statement and whether you agree or disagree with it according to your experiences. Please don’t feel obliged to agree! Some of the statements might really fit your experiences and some might not be true for you at all. | |

| 17 | ● ‘In autistic spaces, I am accepted for who I am’. |

| 18 | ● ‘Being autistic in shared autistic space may be easier than being autistic in neurotypical space – or it may be harder’. |

| 19 | ● ‘There are benefits that neurotypical people bring to social situations’. |

| 20 | ● ‘I notice that non-autistic people don’t understand autistic people any better than autistic people tend to understand non-autistic people’. |

| Thank you for sharing your experiences with me. Do you have anything else that you want to ask, or is there anything I didn’t ask you that you would like to talk about? | |

The AQ

The AQ is a 50-item, multiple-choice questionnaire, which provides an approximate measure of autistic traits (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001). Participants completed this individually, and a score over 32 indicates high levels of autistic traits.

The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence–II

The Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence–II (WASI-II) is a neuropsychological assessment tool, which provides a reliable and brief measure of intelligence (Wechsler, 2011). This was used to establish whether participants were able to verbalise their experiences of relationships with others and to ensure they met the inclusion criteria for no intellectual disability.

Data analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed and then checked for accuracy by the first author. Thematic analysis was applied using the six-phase framework of Braun and Clarke (2006) to identify key patterns in the data. This process involves familiarisation with the data through reading and re-reading the transcriptions (completed by the first author), generating initial codes relevant to interesting features in the data (completed by the first author), searching for themes (completed by first and second authors), reviewing the themes to ensure they relate back to the initial codes (completed by the final author), defining and naming themes (all authors) and relating the findings back to the research literature (all authors) (Braun & Clarke, 2006). This analysis was chosen for its inductive process, as it does not rely on an existing framework to interpret the data, allowing new knowledge to be created, as suitable for this emerging and under-researched area (Willig, 2013). The following example in Table 3 provides a snapshot of a piece of analysis to illustrate this process more clearly.

Table 3.

Illustrative analysis example, indicating the pathway from initial quotes to theme.

| Initial quotes | Codes | Sub-themes | Theme |

|---|---|---|---|

| ‘I have friends . . . who say ‘you should meet these people, they are great, lets all go out to a pub’ and I find it really hard, but also I want to be involved and . . . that is when I feel most upset’. (Participant 2) | Difficulties with neurotypical social activities | Majority social activities and contexts | Minority Experience |

| ‘The physical spaces we have to go to are extremely challenging’. (Participant 8) | Difficulties with the space during neurotypical social interactions | Majority social activities and contexts | |

| ‘I don’t know how to be formal, where I should look and when’. (Participant 7) | Not knowing social rules of neuro-majority | Majority social norms | |

| ‘I talk too much. I don’t know if you have managed to guess that. But I talk too much’. (Participant 4) | Feeling like your style/method of communication does not fit with others | Majority social norms | |

| ‘I feel really annoyed with myself because it is a really normal thing to go to the pub with your friends. But I find it really hard and I really don’t like it . . . but I wish I did’. (Participant 2) | Self-directed negative feelings around/after social events | Impact of being in a minority | |

| ‘My neurotypical family can say ‘you are difficult to be around’ if I don’t mask’. (Participant 2) | Pressure from others to behave in a more ‘neurotypical’ way | Impact of being in a minority |

The first and second authors led the analysis. The first author is a neurotypical researcher with a background and training in neuropsychology. They adopt participatory frameworks in all their autism research, and so this analysis is influenced by mainstream psychological theory and also the lived experience perspective of autistic collaborators. The second author is an autistic adult with a background in autistic advocacy and founder of an advocacy organisation, so they are able to bring in representative lived experiences of autistic adults.

Results

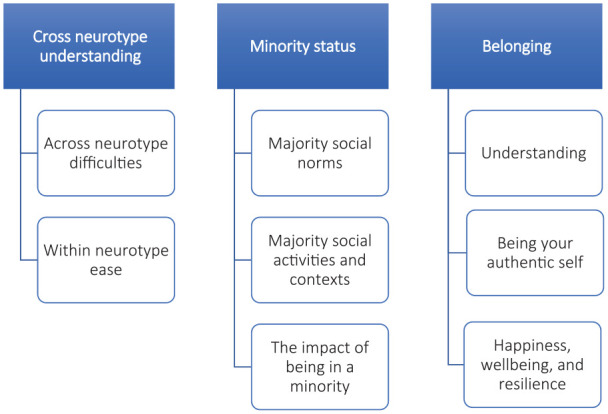

Participants discussed the time they spent with important autistic and non-autistic people in their lives, reflecting on their relationships and how they feel when they are together. Three main themes were identified from these interview data: cross-neurotype understanding, minority status and belonging, each comprising of several subthemes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structure of themes and subthemes.

Theme 1: Cross-neurotype understanding

Participants identified that they often felt they were better understood by other autistic people than non-autistic people, and that there were specific difficulties when spending time with non-autistic people.

Subtheme 1: Across-neurotype difficulties

Participants discussed their difficulties during interactions with non-autistic friends and family, saying that differences in verbal and non-verbal communication styles during social interactions required a high amount of energy and effort when spending time together. In particular, difficulties in reading non-autistic expressions and following the unspoken rules of social interaction made time spent with non-autistic friends and family difficult:

I wouldn’t spend time with people if I didn’t enjoy it, they wouldn’t be my friends . . . regardless of neurotype . . . but neurotypical people . . . are a lot harder to read, and I don’t feel relaxed. (Participant 9)

I’m tired afterwards. It’s not that it is bad, it is just tiring. It takes effort to be around them. I am always thinking ‘should I speak now, what should I say, has this moved on? Is this okay, is that appropriate, will that offend someone? And who is speaking, and what are they saying, and do they really mean that?’ (Participant 2)

These experiences were associated with increased feelings of anxiety in advance of and during spending time with neurotypical friends and family: ‘I get anxious because I have to behave well, to behave neurotypically, to do the right things’ (Participant 2). A recurring topic was feelings of exhaustion and emotional fatigue after spending time with neurotypical people: ‘I do like my neurotypical friends, but they make me tired, they don’t understand me. Even if it’s good it’s exhausting’ (Participant 8).

This exhaustion often affected the autistic persons’ ability to function in the period after the interaction, albeit to varying degrees:

After spending time with neurotypical people there will be a significant amount of time doing something to let my brain switch off a bit, sometimes afterwards it is a challenge to cook myself a meal or something like that. (Participant 12)

After spending time with neurotypical friends, I feel wiped out, completely exhausted. I need to lie in a darkened room for 3–4 hours and when I do, I don’t sleep, I just shut off. I can’t even move and the only way I can communicate is in humming noises. (Participant 3)

While overwhelmingly participants spoke of the various difficulties in interactions with neurotypical people, two participants also mentioned that neurotypical people could be beneficial in a social situation. In both cases, they mentioned the benefits of neurotypical people being able to explain to the autistic person in a 1:1 context what was happening in a group conversation, or wider social event: ‘I can be like “what is going on here?” and then tell them about something, and they can tell me “this is what is happening”’ (Participant 2).

Subtheme 2: Within-neurotype ease

Participants frequently described feelings of comfort and ease when spending time with autistic friends and family. Many stated that communication styles were similar between autistic people, and this made interactions more comfortable that it was easier to follow conversations and understand what people mean: ‘With autistic people, I have a much better idea of what people are doing, what they mean, and picking up on things’ (Participant 2).

Participants noted that there is flexibility with their autistic friends and family about what constitutes a ‘good’ interaction and that whether there is a problem during an interaction that their autistic family and friends will understand: ‘There is no pressure to talk. If there are silences it is not awkward because there is a shared understanding that silence is nice’ (Participant 1) and ‘It feels comfortable. It doesn’t matter if interactions go wrong, it is not stressful, it is nice’ (Participant 4). There was less of a need to mask or camouflage around other autistic people, because there was an assumed mutual understanding and acceptance of autistic behaviours and ways of interaction: ‘You can let your guard down, you can let your mask down. You don’t have to be a certain way with them, because they totally get it’ (Participant 10). Autistic people were also mindful of the potential difficulties that their autistic friends and family face in everyday interactions, and were proactive in making interactions supportive and inclusive:

With my autistic friends . . . people are very sensitised to people being or feeling left out . . . so many of them seem to make a really big effort to stop that from happening. So it’s a much more accessible community for me, because I don’t have to make all the effort, which is how I feel with neurotypical people. Autistic people are willing to meet halfway. (Participant 7)

In contrast to the feelings of fatigue reported after spending time with non-autistic family and friends, many autistic participants highlighted feeling less tired after spending time with their autistic family and friends: ‘It is tiring [interacting with neurotypicals], I have only realised this since I got autistic friends. It is so much easier . . . it is effortless’ (Participant 10).

Although the vast majority of reports described feelings of ease and comfort with other autistic people, two participants brought up difficulties in autistic–autistic relationships. One participant reported that honesty could be hurtful, though that they understood that it may be unintentional: ‘Autistic people . . . can kind of hurt my feelings . . . by being honest . . . but I also understand it. You are not being cruel, you are just kind of being pedantic, and I understand that’ (Participant 2). Another participant stated that they found being with unknown autistic people difficult as they may be unpredictable, though this was not the case with people they were familiar with: ‘Being with autistic people I don’t know, who may exhibit unpredictable behaviours, can be more difficult than being around neurotypicals that I already know. It’s about predictability, if I know what to expect then I find things easier’ (Participant 3).

Theme 2: Minority status

When spending time with non-autistic friends and family, participants experienced feeling in a minority and often felt pressure to conform to the communicative styles and preferences of the non-autistic majority. This affected how they felt about being autistic, often in negative ways.

Subtheme 1: Majority social norms

The unspoken social rules of non-autistic people could make it hard for autistic people to navigate interactions with their non-autistic families and friends. Subtleties of interactions often presented a challenge to autistic people: ‘I often miss subtle things, when people are talking. I don’t always pick up on what they actually mean because they don’t say it. Until someone points it out later, I don’t get it’ (Participant 7).

Often, non-autistic friends and relatives were not accommodating of autistic people’s social needs and preferences, and as a result, autistic people felt obligated to minimise or mask their natural behaviours and preferences in social situations with neurotypical people. These comments were interpreted as examples of autistic people feeling that they were in a social minority and felt obliged to conform to the majority way of communicating in social interactions, or face being excluded. ‘My neurotypical family can say “you are difficult to be around” if I don’t mask’ (Participant 2) and ‘If I am surrounded by neurotypical people, I can’t let my autistic-ness out’ (Participant 12).

Some participants felt that while they tried hard to fit in with their non-autistic friends and family, that their non-autistic friends and family did not try to make the same accommodations for them:

I work very hard to pass as ‘normal’ with non-autistic people. I understand them and I see how they interact. But because they’ve never had to study autistic people in the same way I study them, they don’t understand me, or consider my needs. (Participant 3)

Neurotypical people do not get why certain things might be difficult or an issue for someone with autism. You try to explain it but they are constantly seeing it from a neurotypical perspective. (Participant 9)

Subtheme 2: Majority social activities and context

Often, neurotypical friends and family do not take autistic preferences into account when organising social events, which can compound anxiety and stress during these occasions: This was indicated by autistic participants’ comments that activities were inaccessible to them, or that they posed significant challenges due to the physical or sensory environment: ‘The physical spaces we go to are extremely challenging. They often want to go to places that are busy or noisy’ (Participant 8).

One of the most difficult things when your friends say ‘you should meet these people, they are great, let’s all go out to a pub’ and I find it really hard, but also I want to be involved and . . . that is when I feel most upset because . . . on the other hand I don’t want to, I want everybody to go somewhere that is not noisy. But I also don’t want to be the person that makes us all go to a library . . . and speak in hushed tones. (Participant 2)

Subtheme 3: Impact of being in a minority

As a result of being expected to behave neurotypically with their non-autistic friends and family, autistic people often noted that people developed neurotypical expectations of them. This sometimes led to increased feelings of frustration for the autistic person, both directed at the neurotypical people they were spending time with and directed internally at themselves for not being able to cope with ‘normal things’:

I feel awkward and ashamed [when interacting with neurotypical people . . . I still have a lot of internalised ableism about how I ‘should’ be able to do things that I find difficult. (Participant 9)

Sometimes my [neurotypical] friend, her [neurotypical] partner and my [neurotypical] partner get together for dinner. I’m the only autistic one and I find it very difficult to keep up with conversations and I lose words . . . the others think I’m drunk sometimes (although I’ve not been drinking), and I let them think that because I get embarrassed at mixing my words up. (Participant 3)

Theme 3: Belonging

Participants reported feeling a sense of belonging when around autistic family and friends. With other autistic people, participants described feeling understood and able to be their authentic autistic self. Maintaining relationships with other autistic people allowed autistic people to feel that they belong as part of a community, which for some was a new experience:

We can talk and laugh and challenge ideas and be philosophical, or we can sit together and draw and be silent. We simply allow each other to be and accept everything that we are. (Participant 3)

Subtheme 1: Understanding

When with autistic family and friends, participants said they felt understood and that they understood others. Some autistic participants reflected that this is how they imagine non-autistic people feel all the time:

As lovely as all my neurotypical friends are, I feel I belong there [with autistic people], and I am like everybody else. I have never had that before . . . I feel like I understand people and they understand me. (Participant 2)

Sometimes autistic people like me, you try really hard to be normal . . . and if I was in an autistic space I feel like there is no pressure really. (Participant 4)

Since getting autistic friends I think ‘this is how neurotypical people must feel all the time’ and that is quite sad actually. To realise that people have felt this their whole life, and at ease around people, and felt they belonged as much as I do now. It’s a shame it didn’t happen sooner. (Participant 2)

The autistic participants also said that they felt understanding and empathy for their autistic friends and family: more so than if they had been neurotypical:

I have got a lot more patience [with autistic people] . . . if somebody is going on and on about something and I am like, that is really boring but it’s fine, ’cause I do the same. Whereas I don’t have the same patience for neurotypical people who just go on about things. (Participant 2)

I know that they [an autistic person] might be telling me for 20 minutes about some bird that they saw, but I know how they are feeling, because I feel happy when I see things that I like and I will go on about it. So even though I have no interest in what you are saying I understand how you feel. (Participant 7)

Subtheme 2: Being your authentic autistic self

When with other autistic people, participants felt they did not have to conceal overtly autistic aspects of their behaviour or communication style as they would have around non-autistic friends and family. ‘I can be totally relaxed and totally myself. Anything goes’ (Participant 5). Behaviours such as stimming, rocking and communicating in autistic ways were implicitly accepted by their autistic family and friends. Participants felt they could be their authentic, autistic self in their company:

It’s fab when we get together, autistic space is so validating compared with the outside world, it’s wonderful to see people stimming away without feeling self-conscious. (Participant 9)

I feel free as a bird. No effort is needed. I don’t need to mask and I don’t feel stupid if I don’t understand something. I feel able just to ask. We’re all always getting our words mixed up or losing them and we lost the thread of our conversations but we laugh at it. We all do it and we all get it. (Participant 3)

The language above was echoed in many participant responses who used words like ‘genuine’ and ‘accepting’ to describe their experiences.

Subtheme 3: Happiness, well-being and resilience

Spending time with autistic friends and family was an important source of happiness for these participants: ‘Autistic people make me happy flap’ (Participant 9) and ‘If I know I am going to see one of my autistic friends, I get really excited and I am really happy because I know I am going to have a great time’ (Participant 10).

Spending time with autistic family and friends was also highlighted as an important factor in maintaining mental health and well-being, and in building resilience to manage everyday life in a majority non-autistic world:

It’s very important to have autistic space for people . . . sometimes people fear this is a form of self silo-ing or segregation and I’m not trying to say we don’t need to survive in the non-autistic world too . . . but it’s such a lifeline for many of us. (Participant 9)

There is so much emotional support that comes from spending time with autistic people, because sometimes, there is something that other people see as quite small and actually it can be soul destroying . . . they just get it, and they can help accordingly. (Participant 12)

Autistic people are better at giving advice about your mental health because they have a better idea of what your problem is. Neurotypical people don’t get it in the same way. (Participant 2)

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the experiences of autistic adults spending time with autistic and non-autistic family and friends using a thematic analysis framework. Social relationships are an important, though often complicated, part of autistic people’s lives. Previous research has tended to focus on autistic people’s relationships with (assumed) non-autistic friends and family. Here, we specifically contrasted relationships across and within neurotypes. The analysis revealed three themes: cross-neurotype understanding, minority status and belonging. The themes help us understand why relationships between autistic and non-autistic people might be so challenging, and how relationships between autistic people are different.

The results align with previous research on the challenges that autistic people face when interacting with non-autistic others, but highlight that interactions with other autistic people are fundamentally different. All participants reported that spending time with non-autistic family and friends involved specific difficulties, which were not experienced when interacting with other autistic friends and family. This aligns with the double-empathy theory of autism which suggests that autistic and non-autistic people have a mutual difficulty in understanding and empathising with one another due to differences in how each person understands and experiences the world, rather than because of a communicative deficit on the part of the autistic person (Milton, 2012). Neurotypical people have been shown to overestimate how ego-centric their autistic family members are (Heasman & Gillespie, 2018), and overestimate how helpful they are to autistic people (Heasman & Gillespie, 2019). Our findings suggest that this translates into real-world difficulties in interactions with neurotypical friends and family that may affect the mental health, well-being and self-esteem of autistic people.

One example of how interacting with non-autistic peers could have a negative impact was that it made them more acutely aware of their own minority status within a majority neurotypical society. Having to adapt to neurotypical ways of interacting and socialising caused feelings of inadequacy and shame. Similar findings have been described by Humphrey and Lewis (2008), who found that autistic adolescents surrounded by neurotypical pupils in mainstream secondary schools experienced negative self-image relating to autism. After time spent with majority neurotypical peers, autistic pupils often characterised their differences negatively, believing they had a ‘bad brain’ and wanted to ‘fit in’ with their peers (Humphrey & Lewis, 2008).

Living outside of any majority can cause additional stress. Minority stress is a phenomenon that has been explored in other stigmatised minority groups, including sexual, gender and ethnic minorities (Cokley et al., 2013; Meyer, 2003). It is related to poor social support, discrimination and interpersonal prejudice, all of which cause a stress response that may accrue over time, leading to poor mental and physical health (Clark et al., 1999; Dohrenwend, 2000; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009). While most research into autism and mental health has focused on direct links via co-occurring diagnoses or elevated symptom profiles, recent research has explored the effect that being in an identity-based-minority has on autistic people’s mental health (Botha & Frost, 2018). Botha and Frost (2018) found that for autistic people, minority stressors include everyday discrimination, internalised stigma and camouflaging, and that these factors significantly predicted poorer mental health. These factors are echoed in the words of participants in the current study. Given that the prevalence of both physical and mental illness is significantly higher in autistic populations (Dunn et al., 2019; Hirvikoski et al., 2016; Rydzewska et al., 2018), future research should focus on the experience of minority stress for autistic people, asking whether increasing public knowledge and understanding of autism can alleviate it, and what stress-reducing factors may be available to the autistic population (Botha & Frost, 2018).

Many autistic people felt a sense of comfort and belonging when spending time with their autistic family and friends. Being a part of an autistic community was important: it allowed them to be their authentic self and to be understood. Previous research has highlighted that, for autistic people, inclusion can be characterised by a sense of belonging, feeling valued and given the necessary support to thrive (Goodall, 2018). For autistic people, receiving a diagnosis can open up a new social world – encourage more self-compassion and a greater sense of agency and autonomy (Leedham et al., 2020). Our results indicate that spending time with autistic family and friends gives autistic people the opportunity to extend that compassion, understanding and agency to the autistic people around them.

Spending time with other autistic people was highlighted as important for building resilience to manage day-to-day life, improving well-being, and as a source of happiness. Participants felt validated by spending time with other autistic people as highlighted by their comments on not feeling wrong, broken or bad when around other autistic people. A recent systematic review found very limited support for the efficacy of social support interventions on the mental health or well-being of autistic adults without learning disability (Lorenc et al., 2018), and there have been calls for exploration of the effectiveness of support interventions such as peer support and mentoring (Iemmi et al., 2017; Lorenc et al., 2018). Our findings, in the context of these previous studies, suggest that future research should develop and evaluate peer support models, to provide improvements to autistic people’s mental health and quality of life.

Strengths and limitations

This research is the first examination of autistic people’s relationships with autistic and non-autistic people. While first-person accounts reflecting on these phenomena exist, this study aimed to explore the question in a more systematic way than previous individual accounts. Online messaging, phone and face-to-face options for interview enhanced the diversity of the participant sample. However, there were some limitations to the study. First, the study included 12 speaking, adult participants, all of whom had an IQ close to 100, or well above, and most of whom had been diagnosed in adulthood. Therefore, the study findings may not transfer to the wider autistic population, including children and young people, non-speaking autistic people, autistic people diagnosed in childhood and autistic people with a coexisting learning disability. Second, most of our sample were female, and therefore findings may not transfer to autistic men and non-binary people. In particular, studies have found higher rates of camouflage in autistic women (Lai et al., 2017), and social expectations vary by gender in the United Kingdom. Therefore, the social behaviour and social pressures on autistic males could produce a different experience of the topics examined here. Third, all participants were also based in the United Kingdom: their experiences of social interactions are based on UK social norms, and findings may not transfer to autistic people living outside the United Kingdom. In fact, cross-cultural explorations of autistic people’s experiences of navigating the social world are required.

Conclusion

Delineating precisely what makes interacting with non-autistic people difficult for autistic people may mean that non-autistic people can become more effective social interaction partners, when spending time with autistic family and friends. These results suggest that spending time with other autistic people and within autistic spaces may be beneficial to the mental health of autistic people. In the context of calls for better mental health interventions (Cusack & Sterry, 2016), it is important to develop evidence-based, feasible and acceptable models of autistic peer support and evaluate these for potential mental health benefits. These findings may also be helpful for autistic people in environments in which they are a social minority, such as in education and employment, by enhancing understanding of autistic communication. We hope that a greater understanding of the contexts in which autistic people can have comfortable, natural and easy social interactions will contribute to an evidence base that service providers can draw on to develop better healthcare and education for autistic people.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by a grant from the Templeton World Charity Foundation (grant number: TWCF0200).

ORCID iDs: Catherine J Crompton  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5280-1596

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5280-1596

Sue Fletcher-Watson  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2688-1734

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2688-1734

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bargiela S., Steward R., Mandy W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., Jolliffe T., Mortimore C., Robertson M. (1997). Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(7), 813–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., O’Riordan M., Stone V., Jones R., Plaisted K. (1999). Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 29(5), 407–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S., Wheelwright S., Skinner R., Martin J., Clubley E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barriball K. L., While A. (1994). Collecting data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(2), 328–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauminger N., Kasari C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71(2), 447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botha M., Frost D. M. (2018). Extending the minority stress model to understand mental health problems experienced by the autistic population. Society and Mental Health, 10, 20–34. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Di Monaco J., Newell V. (2018). Experiences of autism acceptance and mental health in autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cage E., Troxell-Whitman Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899–1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder L., Hill V., Pellicano E. (2013). ‘Sometimes I want to play by myself’: Understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism, 17(3), 296–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy S., Bradley L., Shaw R., Baron-Cohen S. (2018). Risk markers for suicidality in autistic adults. Molecular Autism, 9(1), Article 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark R., Anderson N. B., Clark V. R., Williams D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54(10), 805–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. (2004). Social relationships and health. American Psychologist, 59(8), 676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokley K., McClain S., Enciso A., Martinez M. (2013). An examination of the impact of minority status stress and impostor feelings on the mental health of diverse ethnic minority college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41(2), 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell L., Hinch R., Cage E. (2019). The experiences of peer relationships amongst autistic adolescents: A systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 61, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Crompton C. J., Fletcher-Watson S. (2019, May 2). Efficiency and interaction during information transfer between autistic and neurotypical people [Poster presentation]. International Society for Autism Research Annual Conference, Montreal, Ontario, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack J., Sterry R. (2016). Your questions: Shaping future autism research. Autistica. https://www.autistica.org.uk/downloads/files/Autism-Top-10-Your-Priorities-for-Autism-Research.pdf

- Daniel L. S., Billingsley B. S. (2010). What boys with an autism spectrum disorder say about establishing and maintaining friendships. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 25(4), 220–229. [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B. P. (2000). The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn K., Rydzewska E., MacIntyre C., Rintoul J., Cooper S.-A. (2019). The prevalence and general health status of people with intellectual disabilities and autism co-occurring together: A total population study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63(4), 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves L. C., Ho H. H. (2008). Young adult outcome of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(4), 739–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edey R., Cook J., Brewer R., Johnson M. H., Bird G., Press C. (2016). Interaction takes two: Typical adults exhibit mind-blindness towards those with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(7), 879–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U., Happé F. (1994). Autism: Beyond ‘theory of mind’. Cognition, 50(1), 115–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall C. (2018). Inclusion is a feeling, not a place: A qualitative study exploring autistic young people’s conceptualisations of inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 10.1080/13603116.2018.1523475 [DOI]

- Heasman B., Gillespie A. (2018). Perspective-taking is two-sided: Misunderstandings between people with Asperger’s syndrome and their family members. Autism, 22(6), 740–750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heasman B., Gillespie A. (2019). Participants over-estimate how helpful they are in a two-player game scenario toward an artificial confederate that discloses a diagnosis of autism. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley D., Uljarević M., Wilmot M., Richdale A., Dissanayake C. (2018). Understanding depression and thoughts of self-harm in autism: A potential mechanism involving loneliness. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 46, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvikoski T., Mittendorfer-Rutz E., Boman M., Larsson H., Lichtenstein P., Bolte S. (2016). Premature mortality in autism spectrum disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(3), 232–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House J. S., Landis K. R., Umberson D. (1988). Social relationships and health. Science, 241(4865), 540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull L., Petrides K. V., Allison C., Smith P., Baron-Cohen S., Lai M.-C., Mandy W. (2017). ‘Putting on my best normal’: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2519–2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey N., Lewis S. (2008). ‘Make me normal’: The views and experiences of pupils on the autistic spectrum in mainstream secondary schools. Autism, 12(1), 23–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iemmi V., Knapp M., Ragan I. (2017). The autism dividend: Reaping the rewards of better investment. National Autism Project. [Google Scholar]

- Kawachi I., Berkman L. F. (2001). Social ties and mental health. Journal of Urban Health, 78(3), 458–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. C., Lombardo M. V., Ruigrok A. N., Chakrabarti B., Auyeung B., Szatmari P., . . . MRC AIMS Consortium. (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism, 21(6), 690–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leedham A., Thompson A., Smith R., Freeth M. (2020). ‘I was exhausted trying to figure it out’: The experiences of females receiving an autism diagnosis in middle to late adulthood. Autism, 24, 135–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lever A. G., Geurts H. M. (2016). Psychiatric co-occurring symptoms and disorders in young, middle-aged, and older adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(6), 1916–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston L. A., Shah P., Happé F. (2019). Compensatory strategies below the behavioural surface in autism: A qualitative study. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(9), 766–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenc T., Rodgers M., Marshall D., Melton H., Rees R., Wright K., Sowden A. (2018). Support for adults with autism spectrum disorder without intellectual impairment: Systematic review. Autism, 22(6), 654–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan K., Goodall K., Fletcher-Watson S. (2019). Do autistic individuals experience understanding in school? 10.31219/osf.io/awzuk [DOI]

- Mazurek M. O. (2014). Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(3), 223–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milton D. E. M. (2012). On the ontological status of autism: The ‘double empathy problem’. Disability & Society, 27(6), 883–887. [Google Scholar]

- Milton D. E. M., Heasman B., Sheppard E. (2018). Double empathy. In Volkmar F. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of autism spectrum disorders (pp. 1–8). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison K. E., Pinkham A. E., Kelsven S., Ludwig K., Penn D. L., Sasson N. J. (2019). Psychometric evaluation of social cognitive measures for adults with autism. Autism Research, 12(5), 766–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G. I., Krauss M. W., Seltzer M. M. (2004). Peer relationships and social and recreational activities among adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(3), 245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond G. I., Shattuck P. T., Cooper B. P., Sterzing P. R., Anderson K. A. (2013). Social participation among young adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(11), 2710–2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe E. A., Smart Richman L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persicke A., Tarbox J., Ranick J., Clair M. S. (2013). Teaching children with autism to detect and respond to sarcasm. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(1), 193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Petrina N., Carter M., Stephenson J. (2014). The nature of friendship in children with autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(2), 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson A. E., Stanfield A. C., Watt J., Barry F., Day M., Cormack M., Melville C. (2018). The experience and impact of anxiety in autistic adults: A thematic analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 46, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford M. D., Baron-Cohen S., Wheelwright S. (2002). Reading the mind in the voice: A study with normal adults and adults with Asperger syndrome and high functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 32(3), 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydzewska E., Hughes-McCormack L. A., Gillberg C., Henderson A., MacIntyre C., Rintoul J., Cooper S.-A. (2018). Prevalence of long-term health conditions in adults with autism: Observational study of a whole country population. BMJ Open, 8(8), e023945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasson N. J., Faso D. J., Nugent J., Lovell S., Kennedy D. P., Grossman R. B. (2017). Neurotypical peers are less willing to interact with those with autism based on thin slice judgments. Scientific Reports, 7, 40700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savarese E. T. (2009). What we have to tell you: A roundtable with self-advocates from AutCom. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(1). http://dsq-sds.org/article/view/1073 [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F., Crane L., Hill V., Pellicano E. (2019). Friends and lovers: The relationships of autistic and neurotypical women. Autism in Adulthood, 1(2), 112–123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick F., Hill V., Pellicano E. (2019). ‘It’s different for girls’: Gender differences in the friendships and conflict of autistic and neurotypical adolescents. Autism, 23(5), 1119–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard E., Pillai D., Wong G. T., Ropar D., Mitchell P. (2016). How easy is it to read the minds of people with autism spectrum disorder? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(4), 1247–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair J. (2010). Being autistic together. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(1). http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/1075/1248 [Google Scholar]

- Tierney S., Burns J., Kilbey E. (2016). Looking behind the mask: Social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. W. J., Cebula K., Liang S. H., Fletcher-Watson S. (2018). Siblings’ experiences of growing up with children with autism in Taiwan and the United Kingdom. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 83, 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. (2011). WASI-II: Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence–Second edition. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Willig C. (2013). Introducing qualitative research in psychology. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]