Abstract

Background

Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) targeting hepatitis C virus (HCV) have revolutionized outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection.

Methods

We examined early events in liver and plasma through A5335S, a substudy of trial A5329 (paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir, with ribavirin) that enrolled chronic genotype 1a HCV-infected persons coinfected with suppressed HIV: 5 of 6 treatment-naive enrollees completed A5335S.

Results

Mean baseline plasma HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) = 6.7 log10 IU/mL and changed by −4.1 log10 IU/mL by Day 7. In liver, laser capture microdissection was used to quantify HCV. At liver biopsy 1, mean %HCV-infected cells = 25.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4%–42.9%), correlating with plasma HCV RNA (Spearman rank correlation r = 0.9); at biopsy 2 (Day 7 in 4 of 5 participants), mean %HCV-infected cells = 1.0% (95% CI, 0.2%–1.7%) (P < .05 for change), and DAAs were detectable in liver. Plasma C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10) concentrations changed by mean = −160 pg/mL per day at 24 hours, but no further after Day 4.

Conclusions

We conclude that HCV infection is rapidly cleared from liver with DAA leaving <2% HCV-infected hepatocytes at Day 7. We extrapolate that HCV eradication could occur in these participants by 63 days, although immune activation might persist. Single-cell longitudinal estimates of HCV clearance from liver have never been reported previously and could be applied to estimating the minimum treatment duration required for HCV infection.

Keywords: DAA therapy, HIV/HCV coinfection, intrahepatic viral kinetics, single-cell laser capture microdissection

Intrahepatic study of hepatitis C treatment in HIV coinfection reveals rapid removal of HCV RNA but slower resolution of immune activation.

Seventy-one million people have hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and the majority of individuals develop chronic infection [1]. People with human immunodeficiency virus (PWH) are at risk for acquiring HCV due to shared routes of transmission, and they are at high risk of developing chronic infection and liver disease progression [2]. Historically, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/HCV-coinfected people were less likely to achieve sustained virological response (SVR) to HCV treatment; however, direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) are highly effective at clearing HCV. Despite these successes, early attempts to shorten DAA therapy in HIV/HCV coinfection resulted in more virologic relapses than in HCV monoinfection [3]: although 12 weeks of DAAs resulted in SVR in >95% of HIV/HCV-coinfected people, 8 weeks of daclatasvir and sofosbuvir therapy resulted in only a 75.6% SVR in coinfection [4]. Because the marker of treatment efficacy, plasma HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) concentration, becomes undetectable within 4 weeks of therapy initiation in most DAA-treated individuals, it is challenging to predict who might benefit from shortened treatment. Shortened treatment could facilitate HCV eradication among difficult-to-engage populations, such as persons with substance use disorders—this is a subgroup for which standard-duration DAA treatment has already been shown to be effective [5]. A better understanding of HCV decay is required to develop shorter treatments. As a first step, we hypothesized that the fundamental unit of cure is the HCV-infected hepatocyte: quantifying how quickly HCV-infected hepatocytes are lost during treatment might elucidate treatment duration to achieve SVR [6]. We estimated early intrahepatic HCV kinetics among HIV/HCV-coinfected persons initiating combination DAAs through a clinical trial, measuring intrahepatic DAA concentrations to confirm their penetration.

The liver comprises ~8 × 1010 hepatocytes, and only a minority of hepatocytes are infected [7, 8]. However, the rate of loss of HCV-infected hepatocytes during DAA is unknown. Some reports describe liver biopsy or liver fine-needle aspiration (FNA) to measure bulk HCV RNA decline as well as intrahepatic DAA concentrations [9–11]. Mathematical models of plasma HCV RNA kinetics after DAA initiation reveal 3 phases of decline. The rapid first phase represents clearance of viruses from plasma after replication is interrupted by DAAs [12]. The later phases reflect a composite of the loss/turnover of infected hepatocytes and the expulsion of HCV replication complexes from infected cells. We developed single-cell laser capture microdissection to estimate the burden of intrahepatic HCV infection by isolating hundreds of individual hepatocytes from liver biopsies and quantifying HCV RNA in each hepatocyte separately [8].

We conducted a substudy of AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG) A5329 (paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir, with or without ribavirin; paritaprevir identified by AbbVie and Enanta Pharmaceuticals) in HIV/HCV-coinfected persons taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (ART) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT02194998) called A5335S. This combined DAA regimen, when used for 12 or 24 weeks, exhibited high SVR rates among persons coinfected with HIV/HCV whose HIV is suppressed with ART [13]. In A5335S, participants were scheduled to have 2 core liver biopsies: one immediately before DAA treatment initiation and the second 1 week later. We used single-cell laser capture microdissection to estimate the early loss of HCV-infected hepatocytes. We performed plasma pharmacokinetic (PK) sampling and liver FNA at the time of biopsy 2 to confirm DAA penetration in liver. We also assessed whether immune activation that has been previously characterized in HIV/HCV coinfection [14, 15] is controlled after DAA initiation.

METHODS

Study Design

A5335S was a nonrandomized substudy of ACTG-A5329 (NCT02194998), a multicenter clinical trial of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir, with or without ribavirin in genotype 1a or 1b chronic HCV-infected persons with ART-suppressed HIV coinfection. The substudy only enrolled treatment-naive participants without cirrhosis. Institutional Review Board permissions at participating sites were obtained. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment.

Study visits and evaluations for the 7-day study are described in detail (Supplemental Methods, Supplemental Figure 1). In brief, plasma was collected at structured intervals at baseline (Day 0) and after DAA initiation until Day 7: HCV RNA, C-X-C motif chemokine 10 (CXCL10), and PK testing was performed on plasma. Core liver biopsies were collected at baseline (Day 0) and Day 7: single-cell laser capture microdissection with measurement of HCV RNA and interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) was performed on hepatocytes obtained from liver biopsy 1 and liver biopsy 2 from each participant as we have done previously [8, 16]. Liver FNAs were performed on Day 7. Intrahepatic DAA concentrations were measured on FNA samples.

Statistical Methods

The A5335S study team estimated target enrollment of [10–12] individuals, but accrual was halted early due to waning enrollment. Participants included in the analyses completed liver biopsy 1 and liver biopsy 2; some analyses were repeated among participants with liver biopsy 2, Day 7. In addition to a summary of observed data at time of each biopsy, estimated changes and rates of change in plasma HCV RNA and CXCL10 levels were analyzed using the longitudinal method of linear splines. Study sample means and 95% confidence interval (CI) are described in detail (Supplemental Methods).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Six persons enrolled in A5335S from 2 participating sites: 5 individuals completed the study and had 2 core liver biopsies (liver biopsies 1 and 2) (Supplemental Figure 1). One person who enrolled in the study did not have liver biopsy 2 due to anemia and, per protocol, was discontinued from the study. Among the 5 enrollees (participants A-E) who completed A5335S, 4 had liver biopsy 2 on Day 7: participant E delayed liver biopsy 2 until Day 50 due to anemia and imperfect adherence to DAAs and antiretroviral drugs. Mean age was 53 (median, 54; range, 40–61) years, 2 of 5 were female, and 3 of 5 were black (Table 1). Three participants reported a history of injection drug use. All participants were METAVIR Stage 0 or 1. All had genotype 1a HCV infection. Mean baseline plasma HCV RNA was 6.74 log10 IU/mL (median, 6.88; range, 6.00–7.51). Mean baseline aspartate aminotransaminase and alanine aminotransaminase levels were 35 U/mL and 35 U/mL, respectively. Participants were treatment-naive. All participants had undetectable plasma HIV RNA levels (per A5329 protocol), and mean baseline CD4+ T-cell count was 646 cells/μL (median, 646; range, 288–1068). At enrollment, all participants were receiving tenofovir-containing ART regimens (3 of 5 received darunavir/ritonavir; 2 of 5 received integrase-strand transfer inhibitors).

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristicsa

| Characteristics | Total (N = 5) |

|---|---|

| ACTG Site, n (%) | |

| Johns Hopkins University | 3 (60%) |

| Puerto Rico AIDS CTU | 2 (40%) |

| Age (year), mean (range) | 53 (40–61) |

| Female, n (%) | 2 (40%) |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Black non-Hispanic | 3 (60%) |

| Hispanic (regardless of race) | 2 (40%) |

| Previous IV drug use reported, n (%) | 3 (60%) |

| CD4+ T cells (cells/mm3), mean (range) | 646 (288–1068) |

| ART regimen | |

| FTC + TAF + DTG | 1 (20%) |

| FTC + TAF + RAL | 1 (20%) |

| FTC + TAF (or TDF) + DRV/r | 3 (60%) |

| Plasma HCV RNA (log10 IU/mL), mean (range) | 6.7 (6.0–7.5) |

| Time from chronic HCV dx to study entry (years), mean (range) | 18 (11–25) |

| ALT (U/mL), mean (range) | 35 (13–71) |

| AST (U/mL), mean (range) | 35 (19–48) |

| Fibrosis stage, METAVIR, n (%) | |

| Stage 0 | 1 (20%) |

| Stage 1 | 4 (80%) |

| Calculated creatinine clearance (mL/min), mean (range) | 107.4 (70.3–163.0) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL), mean (range) | 14.2 (11.3–16.4) |

| Plasma CXCL10 (pg/mL), mean (range) | 426.8 (170.0–817.2) |

Abbreviations: ACTG, AIDS Clinical Trials Group; AIDS, acquired immunodefiecincy syndrome; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ART, antiretroviral therapy; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CTU, Clinical Trials Unit; DTG, dolutegravir; DRV/r, darunavir/ritonavir; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; IP-10, inducible protein-10; IV, intravenous; FTC, emtricitabine; RNA, ribonucleic acid; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir dispproxil fumarate.

aAll participants had genotype 1a HCV infection and were HCV treatment naive. All participants had plasma HIV RNA suppression <40 cp/mL at screening. Participants were considered to be noncirrhotic at screening whether the absence of cirrhosis was documented by a FibroScan result of <12.5 kPa (seen in 4 participants), or HCV FibroSURE score of <0.72 and AST to platelet ratio index (APRI) score <2 (seen in 1 participant).

Participant E had a decrease in hemoglobin from 11.3 g/mL at baseline to 9.7 g/dL at Day 6. No significant pulse or blood pressure changes were observed in the initial 4 hours immediately after biopsies, and postprocedural ultrasound did not reveal bleeding, suggesting that anemia was not due to intra-abdominal bleeding. No participants required blood transfusion after biopsies. Pain assessments during the 4 hours after biopsies ranged from none to moderate (3 participants).

Virological Measurements

Plasma HCV RNA levels were measured and showed rapid declines within 24 hours after DAA initiation, followed by slower declines from Day 1 through 7 (Figure 1). The observed (estimated) mean change in plasma HCV RNA from baseline was −3.0 (−3.0) log10 IU/mL at Day 1 and −4.1 (−4.2) log10 IU/mL at Day 7. Participant E had the highest baseline plasma HCV RNA levels and the smallest changes after DAA initiation.

Figure 1.

Plasma hepatitis C virus (HCV) ribonucleic acid (RNA) viral kinetics. Shown are plasma HCV RNA levels (log10 IU/mL) for each participant (depicted by a different color and with separate hashed lines) over the first 7 days of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy. The predicted plasma HCV RNA kinetics for the 5 participants is shown in solid black lines. LLOQ, lower limit of quantification.

We used single-cell laser capture microdissection to investigate intrahepatic HCV kinetics. As described previously [8, 17], we dissected individual hepatocytes from flash-frozen liver tissues: a median of 400 (range, 276–403) hepatocytes were isolated from liver biopsy 1 and 308 (range, 276–368) hepatocytes from liver biopsy 2, totaling 3359 hepatocytes. We excluded 116 and 123 hepatocytes from liver biopsy 1 and 2, respectively, because they did not meet internal quality control standards (Supplemental Methods), retaining 93% hepatocytes for analysis. We measured HCV RNA individually using quantitative polymerase chain reaction, compared with a characterized standard. For liver biopsy 1, estimated mean percentage of HCV-infected hepatocytes was 25.2% (95% CI, 7.4%–42.9%); for liver biopsy 2 (Day 7 for participants A–D and Day 50 for participant E), estimated mean percentage was 1.0% (95% CI, .2%–1.7%) for all participants and 1.2% (95% CI, 1%–2.2%) for participants A–D. Estimated mean change (absolute difference) in the percentage of HCV-infected hepatocytes among participants A–D was −19.4% points (95% CI, −33.2% points to −5.7% points) (Figure 2A), and among all 5 participants it was −24.6% points (95% CI, −41.4% points to −7.8% points). When compared with the proportion of infected cells in liver biopsy 1, the proportion of infected cells in liver biopsy 2 represented >90% loss of HCV-infected cells, even when restricted only to participants who had liver biopsy 2 performed on Day 7. We also quantified intracellular HCV RNA in infected hepatocytes (Figure 2B). Median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile) HCV RNA/cell in liver biopsy 1 was 8 (4.17) IU/cell; only 13 infected hepatocytes were found among liver biopsy 2 tissues, and the median (1st quartile, 3rd quartile) HCV RNA per hepatocyte in second biopsies was 12 (5.27) IU/cell.

Figure 2.

Intrahepatic burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) before and during direct-acting antivirals. (A) Absolute change in percentage of HCV+ hepatocytes: proportions of HCV+ hepatocytes at biopsies 1 and 2 are shown. In parentheses, the number of HCV+ hepatocytes and the total number of measured hepatocytes for each participant at each time point are shown. (B) Hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid (RNA) amounts per hepatocyte at biopsies 1 and 2 are shown. Each dot represents an HCV+ hepatocyte, and colors represent from which participant each dot derives. The median (1st quartile [Q1], 3rd quartile [Q3]) HCV RNA per infected hepatocyte are shown for biopsies 1 and 2 in the top left.

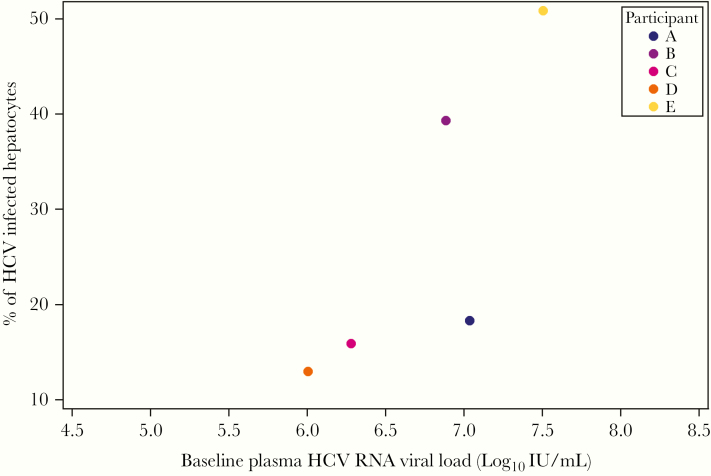

At baseline, plasma HCV RNA levels were positively correlated with the proportion of HCV-infected hepatocytes (Spearman correlation = 0.9; exact 95% CI, .58–1.00) (Figure 3) and not associated with median intracellular HCV RNA levels (Spearman correlation = −0.4; exact 95% CI, −1.00 to .64) (Supplemental Figure 2). Although we did not observe an association between the change in proportion of HCV-infected hepatocytes with the change in plasma HCV RNA concentration when including all participants (Spearman correlation = −0.1; exact 95% CI, −1.0 to 1.0), there was a suggestion of a positive correlation between changes in these 2 compartments among only participants A–D who had liver biopsy 2 on Day 7 (Spearman correlation = 0.8; exact 95% CI, .2–1.0) (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Proportion of hepatitis C virus (HCV)+ hepatocytes and plasma HCV ribonucleic acid (RNA) level. Plasma HCV RNA levels (x-axis) and the proportion of HCV+ hepatocytes at liver biopsy 1 (y-axis) are shown. Spearman correlation = 0.9; exact 95% confidence interval, .58–1.00.

Pharmacological Measurements

We confirmed that empiric measurements of loss of HCV-infected hepatocytes reflected potent antiviral effects in the liver by measuring intrahepatic concentrations of administered DAA (paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, dasabuvir, and dasabuvir metabolite [M1]) in liver FNAs (Supplemental Methods), followed by 12-hour plasma PK sampling. Median time between FNA and predose plasma trough sample collection was 0.9 (range, 0.6–1.3) hours. Self-reported adherence over 3-day recall was 89% before intensive PK sampling. More than 50% of all study drug dose administrations were observed by research staff over the 7-day substudy. All DAAs and metabolites were quantifiable in plasma and liver for all participants.

Plasma PKs were similar to what has been described previously for these agents: variability in plasma and liver concentrations differed by drug, consistent with previous findings (Table 2) [11]. We focus on paritaprevir and dasabuvir (Figure 4), which have been well characterized by our group [11, 18]. Paritaprevir was quantifiable in liver FNA at a geometric mean concentration (GMC) of 2047 ng/gram tissue (95% CI, 768–5461); geometric mean plasma C0 for paritaprevir was 30 ng/mL (95% CI, 6–145) and Cmax was 1137 ng/mL (95% CI, 273–4749). Dasabuvir was quantified in liver FNA at a GMC of 451 ng/gram tissue (95% CI, 323–629); geometric mean plasma C0 for dasabuvir was 233 ng/mL (95% CI, 92–589) and Cmax was 881 ng/mL (95% CI, 614–1262). We explored whether intrahepatic drug concentrations were associated with clearance of HCV-infected hepatocytes. Among 4 participants for whom liver FNA were available, the participant with highest intrahepatic drug concentrations at Day 7 also had slightly larger relative decreases in the proportion of HCV-infected hepatocytes at Day 7 compared with the other participants (Supplemental Figure 4), although there was no correlation between intrahepatic drug concentrations and the absolute change in proportion of infected hepatocytes.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics of Ombitasvir, Paritaprevir, Ritonavir, Dasabuvir, and Dasabuvir M1 Metabolite Pharmacokinetic Parameters and Hepatic Tissue Concentrations

| Pharmacokinetic parameter | Ombitasvir | Paritaprevir | Ritonavir | Dasabuvir | M1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C max, ng/mL | |||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 100 (57–177) | 1137 (273–4749) | 1038 (530–2033) | 881 (614–1262) | 307 (183–514) |

| Mean (SD) | 110 (54) | 1555 (805) | 1184 (758) | 911 (272) | 330 (145) |

| t max, hours | |||||

| Median [range] | 4 [4–6] | 4 [2–4] | 4 [2–4] | 2 [2–4] | 4 [4–6] |

| AUCτ, ng × h/mL | |||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 1367 (816–2291) | 8282 (2094–32 761) | 7943 (5776–10 922) | 6451 (4201–9907) | 2210 (1573–3105) |

| Mean (SD) | 1478 (732) | 11468 (7271) | 8169 (2305) | 6773 (2401) | 2280 (669) |

| C0, ng/mL | |||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 28 (14–54) | 30 (6–145) | 154 (42–565) | 233 (92–589) | 57 (31–104) |

| Mean (SD) | 32 (21) | 58 (78) | 230 (211) | 296 (248) | 62 (30) |

| C12, ng/mLb | -- | -- | |||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 297 (99–892) | 279 (109–714) | 82 (44–154) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 319 (153) | 344 (236) | 91 (45) | ||

| FNA concentration (n = 4)a, ng/g | |||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 76 (27–217) | 2047 (768–5461) | 2678 (1223–5865) | 451 (323–629) | 560 (272–1151) |

| Mean (SD) | 92 (73) | 2348 (1387) | 2922 (1339) | 458 (97) | 605 (270) |

| CNB concentration (n = 2)a, ng/g | |||||

| Minimum | 151 | 4798 | 612 | 904 | 434 |

| Maximum | 6634 | 18 259 | 1261 | 1586 |

Abbreviations: AUCτ, area under plasma-concentration time curve to infinity; C0, predose plasma concentration at time 0 hours; C12, postdose plasma concentration at time 12 hours; CI, confidence interval; CNB, core needle biopsy; Cmax, maximum observed plasma concentration; FNA, fine-needle aspiration; SD, standard deviation; tmax, time to maximum observed plasma concentration.

aPlasma pharmacokinetics includes data from 5 participants. Hepatic tissue concentrations collected via FNA and core needle biopsy includes data from 4 and 2 participants, respectively.

bC12 values are summarized for drugs administered twice daily. Three participants received ritonavir twice daily.

Figure 4.

Plasma and liver concentrations of direct-acting antivirals. The mean concentrations among all 5 participants in plasma (Cmax, C0) and from liver fine-needle aspirates (FNAs) are shown.

Immunological Measurements

Innate immune activation is well described in chronic HCV infection [19–21]: circulating levels of the chemokine CXCL10 and ISG expression in liver and in peripheral blood mononuclear cells have been associated with poor treatment responses to interferon [22–28]. We found that CXCL10 levels declined rapidly from baseline within the first 4 days of therapy, similar to plasma HCV RNA levels (Figure 5); however, the rate of decline of CXCL10 levels slowed considerably after Day 4, and Day 7 levels were not significantly different from Day 4. We tested for persistent hepatocyte ISG expression using single-cell laser capture microdissection, quantifying messenger RNAs for interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 (IFITM3), interferon alpha-inducible protein 6 (IFI6), interferon alpha-inducible protein 27 (IFI27), and interferon-stimulated gene 15 (ISG15), which have been described in HCV [29–32]. We probed ISGs in 1129 hepatocytes from all participants obtained in liver biopsy 1, and 860 hepatocytes in liver biopsy 2 (Supplemental Table 1). The %hepatocyte expression of ISGs covaried closely (Supplemental Table 2). The IFITM3 expression reduced modestly from 46.8% of hepatocytes in liver biopsy 1 to 36.2% in liver biopsy 2, changing by −10.7% points (95% CI, −18.1 points to −3.2 points) (Supplemental Table 3). The proportions of hepatocytes expressing IFI6, IFI27, and ISG15 did not show significant changes between first and second biopsies. Moreover, there was no clear relationship between HCV-infected hepatocytes and ISG expression (Supplemental Table 4). Taken together with CXCL10 levels, immune activation in these HIV/HCV-coinfected people persisted despite rapid loss of HCV-infected hepatocytes.

Figure 5.

Plasma CXCL10 kinetics. The CXCL10 levels for each participant (depicted by a different color and with separate hashed lines) are shown. Predicted CXCL10 kinetics are shown in solid black lines. Vertical hashed lines indicate different phases of decline: 24 hours (Day 1) and 96 hours (Day 4). DAA, direct-acting antiviral; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Discussion

In this paired biopsy study, the first of its kind, we observed that HCV-infected hepatocytes rapidly decreased with DAA treatment, representing loss of >90% of infected hepatocytes within 1 week. To our knowledge, this study is the first to quantify the loss of HCV-infected hepatocytes with treatment. These findings are supported by corresponding PK data showing that DAAs were abundant in liver by Day 7. In addition, we found evidence of persistent immune activation despite marked clearance of HCV in blood and liver: CXCL10 levels ceased to decline after the first 4 days of treatment, and hepatocyte ISG expression dissipated slowly.

Mathematical models of plasma viral kinetics during combination DAA therapy describe early and late phases of decline. The rapid first phase (24–48 hours) corresponds to inhibition of viral production, estimated as high as 1011–1012 virions/day [12, 33]. By interrupting viral production with DAAs, the rapid clearance rate of HCV virions is revealed, and it accounts for the ~3–4 log10 IU/mL decrease that occurs within 24–48 hours of treatment. The later phases result from loss of HCV-infected cells. We previously reported that initial declines in bulk liver HCV RNA were slower relative to plasma until Day 4, but it was comparable with plasma after Day 4 [10]. In this study, we provide the first empiric quantification of loss of infected cells during DAA therapy, confirming mathematical models [12].

Viral kinetics during DAA therapy have not consistently predicted SVR [34–36]: one group reported early plasma HCV RNA kinetics predicted treatment responses [37], but others described detectable plasma HCV RNA levels at the end of therapy in patients who ultimately achieved SVR [38, 39]. Early attempts to shorten therapy revealed that relapse was often with virions that lack resistance-associated substitutions [40–42]. Duration of DAA treatment depends on the rapidity of loss of HCV-infected hepatocytes. Using our data, we estimate that the number of infected hepatocytes at baseline ranged from 1.04 × 1010 to 4.07 × 1010 cells and declined on therapy to 3.04 × 108 to 1.36 × 109 cells by Day 7. From those estimates, and assuming 100% adherence, we extrapolate that HCV could be eradicated after 50–63 days of treatment. Our estimates are corroborated by high SVR rates (97%) reported in a trial of paritaprevir/ritonavir, ombitasvir, and dasabuvir for 8 weeks in which 77% of participants were HIV-infected [43].

A key assumption of mathematical models is full intrahepatic DAA penetration [44]. We demonstrated efficient delivery and sometimes higher exposure of DAAs in the liver compared with plasma. Likewise, in persons with HCV monoinfection, intrahepatic paritaprevir concentrations were up to 46-fold higher than in plasma [11]. Paritaprevir and vaniprevir are substrates of solute carrier organic anion transporters (OATP) that facilitate hepatic uptake of drug, and both demonstrated enhanced liver concentrations compared with plasma [9]. In contrast, DAAs with different drug transporter profiles, such as telaprevir (a substrate of the hepatocyte efflux transporter, P-glycoprotein), have shown less liver penetration [10, 11].

We were surprised to observe that intracellular HCV RNA levels did not appreciably change in HCV+ hepatocytes despite high intrahepatic DAA concentrations. We speculate several possible reasons for the lack of difference in intracellular HCV RNA between biopsies: (1) although bulk intrahepatic DAA concentrations were high, individual hepatocytes may have heterogeneous drug penetration, allowing HCV RNA to persist in some hepatocytes; (2) some hepatocytes may harbor viral genomes with variants that confer partial resistance to 1 or more DAAs; and (3) HCV RNAs and viral nonstructural proteins may be partly secluded from cytoplasm (and hence, DAAs) in membranous webs. More research is required to determine whether these “hyper-persister” hepatocytes explain the small numbers of people who relapse during DAA treatment.

An unsettling finding was that abnormal peripheral and liver immune activation persisted after virus was cleared from liver. Immune activation in HCV monoinfection declines rapidly during DAA therapy [22–24, 26, 45–47]. Meissner et al [24] previously reported that intrahepatic ISG expression is decreased in all DAA-treated individuals at the end of treatment. In our study, median CXCL10 levels after 7 days of DAAs decreased to 127 pg/mL, which is greater than median levels reported among HIV/HCV-uninfected people who inject drugs by Veenhuis et al [48]. It is possible that CXCL10 release and intrahepatic ISG expression is more sensitive to residual intrahepatic HCV in HIV/HCV coinfection than in monoinfection. It is also possible that residual immune activation due to HIV is only partly controlled by HIV RNA suppression [49, 50]. In either case, residual residual immune activation in HIV/HCV-coinfected persons warrants further study.

This investigation had several limitations. Although we originally sought to enroll 10–12 individuals, the substudy was slow to enroll given the rapidly changing DAA treatment landscape and intensive nature of substudy participation. Thus, larger studies of intrahepatic viral kinetics during DAA treatment are required to generalize our results. However, it is reassuring that despite small numbers, the plasma HCV RNA level and the proportion of HCV+ hepatocytes were strongly correlated (Figure 3). As a related note, the substudy mainly enrolled people with minimal fibrosis and hence represented people who were unlikely to relapse. Therefore, future studies are needed to evaluate how our findings can be generalized to patients with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis. Furthermore, we only studied persons with genotype 1a HCV infection and HIV coinfection: it is possible that the intrahepatic clearance of HCV differs in persons with HCV monoinfection or in those infected with other HCV genotypes. Another limitation is that analyzing several hundred hepatocytes is subject to sampling bias, albeit less so in people with minimal fibrosis. Finally, whereas previously we and others have observed spatial clustering of HCV+ hepatocytes [7, 8, 17], there were so few remaining HCV+ hepatocytes after DAA treatment that there was limited power to comment on spatial clustering.

Conclusions

Combination DAA treatment for HCV is one of the most significant revolutions in biomedicine in the past 20 years. Our study is the first to characterize the role of these medications in the liver, the organ of interest, in HIV/HCV-coinfected people with genotype 1 HCV. We show that >90% of HCV-infected hepatocytes are lost within 7 days after initiating therapy. We estimated a lower bound for treatment duration: limiting DAA therapy to the minimum duration may have substantial benefits for difficult-to-engage individuals, such as substance users who remain a reservoir for the infection, and for healthcare systems.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Kenneth Bowden, Tony James, and Jaiprasath Sachithanandham for performing single-cell laser capture microdissection. We also thank the participants in this study.

Author contributions. A. B. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; L. M. S. contributed to planning, statistical analysis, and writing; J. Q. contributed to performed technical laboratory work; V. V. contributed to statistical analysis and writing; C. S. V. contributed to planning, analysis, interpretation, and writing; G. D. M. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; B. A.-S. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; D. E. C. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; J. L. S.-B. contributed to planning, recruitment, interpretation, and writing; D. D. A. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; M. S. S. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; D. L. W. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing; and A. H. T. contributed to planning, interpretation, and writing.

Disclaimer.The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This study was funded by AbbVie and the AIDS Clinical Trials Group. National Institutes of Health grants were awarded to A. B. (R01 AI116868), M. S. S. (K24 DA034621), C. S. V. (K23 AI108355), and the Johns Hopkins University Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI094189). Participant recruitment was conducted at the Johns Hopkins University Clinical Research Site (UM1 AI069465) and the University of Puerto Rico AIDS Clinical Trials Unit (UM1 AI069415). Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers UM1 AI068634, UM1 AI068636, and UM1 AI106701.

Potential conflicts of interest. A. B. has received funding for consultancy from Gilead Sciences, Inc., and Sanofi has provided research funding to the institution. D. E .C. is a paid employee of AbbVie, Inc. J. L. S.-B. has received speaker honoraria and has been on the Ad Board, Research for Gilead Sciences, ViiV, AbbVie, and Merck. D. D. A. consults for Cellular Technologies Limited. M. S. S. received research support and served as a scientific advisor for Gilead Sciences and AbbVie. D. L. W. received research funding from Gilead Sciences paid to his institution. A. H. T. received research support from Merck, Gilead Sciences, Abbott, AbbVie, Intercept, Conatus, Genfit, and Bristol-Meyers Squibb. He also served as scientific advisor for Merck, Abbott Diagnostics, AbbVie, and Gilead Sciences. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. DETECTION OF VIRAEMIC HCV INFECTION - to guide who to treat. WHO Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017:1–152. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, et al. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA 2000; 284:450–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luetkemeyer AF, McDonald C, Ramgopal M, Noviello S, Bhore R, Ackerman P. 12 weeks of daclatasvir in combination with sofosbuvir for HIV-HCV coinfection (ALLY-2 Study): efficacy and safety by HIV combination antiretroviral regimens. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62:1489–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wyles DL, Ruane PJ, Sulkowski MS, et al. ; ALLY-2 Investigators Daclatasvir plus sofosbuvir for HCV in patients coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med 2015; 373:714–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grebely J, Dalgard O, Conway B, et al. ; SIMPLIFY Study Group Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:153–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Goyal A, Lurie Y, Meissner EG, et al. Modeling HCV cure after an ultra-short duration of therapy with direct acting agents. Antiviral Res 2017; 144:281–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liang Y, Shilagard T, Xiao SY, et al. Visualizing hepatitis C virus infections in human liver by two-photon microscopy. Gastroenterology 2009; 137:1448–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kandathil AJ, Graw F, Quinn J, et al. Use of laser capture microdissection to map hepatitis C virus-positive hepatocytes in human liver. Gastroenterology 2013; 145:1404-13.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wright DH, Caro L, Cerra M, et al. Liver-to-plasma vaniprevir (MK-7009) concentration ratios in HCV-infected patients. Antivir Ther 2015; 20:843–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Talal AH, Dimova RB, Zhang EZ, et al. Telaprevir-based treatment effects on hepatitis C virus in liver and blood. Hepatology 2014; 60:1826–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Talal AH, Dumas EO, Bauer B, et al. Hepatic pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics with ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir treatment and variable ribavirin dosage. J Infect Dis 2018; 217:474–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Perelson AS, Guedj J. Modelling hepatitis C therapy–predicting effects of treatment. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12:437–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sulkowski MS, Eron JJ, Wyles D, et al. Ombitasvir, paritaprevir co-dosed with ritonavir, dasabuvir, and ribavirin for hepatitis C in patients co-infected with HIV-1: a randomized trial. JAMA 2015; 313:1223–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. López-Cortés LF, Trujillo-Rodríguez M, Báez-Palomo A, et al. Eradication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) reduces immune activation, microbial translocation, and the HIV DNA level in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. J Infect Dis 2018; 218:624–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shmagel KV, Saidakova EV, Shmagel NG, et al. Systemic inflammation and liver damage in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection. HIV Med 2016; 17:581–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Munshaw S, Hwang HS, Torbenson M, et al. Laser captured hepatocytes show association of butyrylcholinesterase gene loss and fibrosis progression in hepatitis C-infected drug users. Hepatology 2012; 56:544–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Graw F, Balagopal A, Kandathil AJ, et al. Inferring viral dynamics in chronically HCV infected patients from the spatial distribution of infected hepatocytes. PLoS Comput Biol 2014; 10:e1003934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Venuto CS, Markatou M, Woolwine-Cunningham Y, et al. Paritaprevir and ritonavir liver concentrations in rats as assessed by different liver sampling techniques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61:e02283–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zeremski M, Dimova R, Astemborski J, Thomas DL, Talal AH. CXCL9 and CXCL10 chemokines as predictors of liver fibrosis in a cohort of primarily African-American injection drug users with chronic hepatitis C. J Infect Dis 2011; 204:832–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zeremski M, Dimova R, Brown Q, Jacobson IM, Markatou M, Talal AH. Peripheral CXCR3-associated chemokines as biomarkers of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Infect Dis 2009; 200:1774–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zeremski M, Petrovic LM, Talal AH. The role of chemokines as inflammatory mediators in chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat 2007; 14:675–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meissner EG, Wu D, Osinusi A, et al. Endogenous intrahepatic IFNs and association with IFN-free HCV treatment outcome. J Clin Invest 2014; 124:3352–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Meissner EG, Decalf J, Casrouge A, et al. Dynamic changes of post-translationally modified forms of CXCL10 and soluble DPP4 in HCV subjects receiving interferon-free therapy. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0133236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Meissner EG, Kohli A, Virtaneva K, et al. Achieving sustained virologic response after interferon-free hepatitis C virus treatment correlates with hepatic interferon gene expression changes independent of cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat 2016; 23:496–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zeremski M, Dimova RB, Makeyeva J, et al. IL28B polymorphism, pretreatment CXCL10, and HCV RNA levels predict treatment response in racially diverse HIV/HCV coinfected and HCV monoinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013; 63:9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zeremski M, Dimova RB, Benjamin S, Penney MS, Botfield MC, Talal AH. Intrahepatic and peripheral CXCL10 expression in hepatitis C virus-infected patients treated with telaprevir, pegylated interferon, and ribavirin. J Infect Dis 2015; 211:1795–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sarasin-Filipowicz M, Oakeley EJ, Duong FH, et al. Interferon signaling and treatment outcome in chronic hepatitis C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105:7034–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zeremski M, Markatou M, Brown QB, Dorante G, Cunningham-Rundles S, Talal AH. Interferon gamma-inducible protein 10: a predictive marker of successful treatment response in hepatitis C virus/HIV-coinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007; 45:262–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Narayana SK, Helbig KJ, McCartney EM, et al. The interferon-induced transmembrane proteins, IFITM1, IFITM2, and IFITM3 inhibit hepatitis C virus entry. J Biol Chem 2015; 290:25946–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meyer K, Kwon YC, Liu S, Hagedorn CH, Ray RB, Ray R. Interferon-alpha inducible protein 6 impairs EGFR activation by CD81 and inhibits hepatitis C virus infection. Sci Rep 2015; 5:9012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bellecave P, Sarasin-Filipowicz M, Donze O, et al. Cleavage of mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein in the liver of patients with chronic hepatitis C correlates with a reduced activation of the endogenous interferon system. Hepatology 2010; 51:1127–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chua PK, McCown MF, Rajyaguru S, et al. Modulation of alpha interferon anti-hepatitis C virus activity by ISG15. J GenVirol 2009; 90:2929–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science 1998; 282:103–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kowdley KV, Nelson DR, Lalezari JP, et al. On-treatment HCV RNA as a predictor of sustained virological response in HCV genotype 3-infected patients treated with daclatasvir and sofosbuvir. Liver Int 2016; 36:1611–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dahari H, Canini L, Graw F, et al. HCV kinetic and modeling analyses indicate similar time to cure among sofosbuvir combination regimens with daclatasvir, simeprevir or ledipasvir. J Hepatol 2016; 64:1232–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garbuglia AR, Visco-Comandini U, Lionetti R, et al. Ultrasensitive HCV RNA quantification in antiviral triple therapy: new insight on viral clearance dynamics and treatment outcome predictors. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0158989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sarrazin C, Wedemeyer H, Cloherty G, et al. Importance of very early HCV RNA kinetics for prediction of treatment outcome of highly effective all oral direct acting antiviral combination therapy. J Virol Methods 2015; 214:29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sidharthan S, Kohli A, Sims Z, et al. Utility of hepatitis C viral load monitoring on direct-acting antiviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60:1743–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nguyen THT, Guedj J, Uprichard SL, Kohli A, Kottilil S, Perelson AS. The paradox of highly effective sofosbuvir-based combination therapy despite slow viral decline: can we still rely on viral kinetics? Sci Rep 2017; 7:10233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sulkowski MS, Flamm S, Kayali Z, et al. Short-duration treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus with daclatasvir, asunaprevir, beclabuvir and sofosbuvir (FOURward study). Liver Int 2017; 37:836–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sims KD, Lemm J, Eley T, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, single-ascending-dose study of BMS-791325, a hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5B polymerase inhibitor, in HCV genotype 1 infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:3496–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pasquinelli C, McPhee F, Eley T, et al. Single- and multiple-ascending-dose studies of the NS3 protease inhibitor asunaprevir in subjects with or without chronic hepatitis C. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:1838–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Martinello M, Bhagani S, Gane E, et al. Shortened therapy of eight weeks with paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir and dasabuvir is highly effective in people with recent HCV genotype 1 infection. J Viral Hepat 2018; 25:1180–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Talal AH, Ribeiro RM, Powers KA, et al. Pharmacodynamics of PEG-IFN alpha differentiate HIV/HCV coinfected sustained virological responders from nonresponders. Hepatology 2006; 43:943–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lin JC, Habersetzer F, Rodriguez-Torres M, et al. Interferon gamma-induced protein 10 kinetics in treatment-naive versus treatment-experienced patients receiving interferon-free therapy for hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the innate immune response. J Infect Dis 2014; 210:1881–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Carlin AF, Aristizabal P, Song Q, et al. Temporal dynamics of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines during sofosbuvir and ribavirin therapy for genotype 2 and 3 hepatitis C infection. Hepatology 2015; 62:1047–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Alao H, Cam M, Keembiyehetty C, et al. Baseline intrahepatic and peripheral innate immunity are associated with hepatitis C virus clearance during direct-acting antiviral therapy. Hepatology 2018; 68:2078–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Veenhuis RT, Astemborski J, Chattergoon MA, et al. Systemic elevation of proinflammatory interleukin 18 in HIV/HCV coinfection versus HIV or HCV monoinfection. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 64:589–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Balagopal A, Asmuth DM, Yang WT, et al. ; ACTG PEARLS and NWCS 319 Study team Pre-cART elevation of CRP and CD4+ T-cell immune activation associated with HIV clinical progression in a multinational case-cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015; 70:163–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Shivakoti R, Yang WT, Berendes S, et al. ; NWCS 319 and PEARLS Study Team Persistently elevated C-reactive protein level in the first year of antiretroviral therapy, despite virologic suppression, is associated with HIV disease progression in resource-constrained settings. J Infect Dis 2016; 213:1074–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.