Abstract

Phthiocerol dimycocerosates (PDIMs) are a class of mycobacterial lipids that promote virulence in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium marinum. It has recently been shown that PDIMs work in concert with the M. tuberculosis Type VII secretion system ESX-1 to permeabilize the phagosomal membranes of infected macrophages. As the zebrafish-M. marinum model of infection has revealed the critical role of PDIM at the host-pathogen interface, we set to determine if PDIMs contributed to phagosomal permeabilization in M. marinum. Using an ΔmmpL7 mutant defective in PDIM transport, we find the PDIM-ESX-1 interaction to be conserved in an M. marinum macrophage infection model. However, we find PDIM and ESX-1 mutants differ in their degree of defect, with the PDIM mutant retaining more membrane damaging activity. Using an in vitro hemolysis assay—a common surrogate for cytolytic activity, we find that PDIM and ESX-1 differ in their contributions: the ESX-1 mutant loses hemolytic activity while PDIM retains it. Our observations confirm the involvement of PDIMs in phagosomal permeabilization in M. marinum infection and suggest that PDIM enhances the membrane disrupting activity of pathogenic mycobacteria and indicates that the role they play in damaging phagosomal and red blood cell membranes may differ.

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the causative agent of tuberculosis (TB), is an obligate human pathogen; its ability to survive and spread is dependent upon its ability to survive within its human host. During the early stages of infection, this requires manipulation of the innate immune system, allowing for survival of the pathogen within the microbicidal environment of host macrophages [1]. M. tuberculosis and the pathogenic M. marinum use their lipid coats and Type VII secretion systems to evade and co-opt ordinarily lethal host defenses within these monocytes.

The virulence lipid phthiocerol dimycocerosate (PDIM) is an outer membrane virulence lipid in both M. marinum and M. tuberculosis. PDIM-deficient mutants in M. marinum and M. tuberculosis are attenuated in animal models of infection [2–4] and membrane permeability [5, 6]. Contact between mycobacteria and host environment results in the transfer of surface PDIM into host membranes, suppressing toll-like receptor signaling (TLR) and preventing the recruitment of microbicidal monocytes during infection [4, 7, 8]. Consequently, PDIM mutants are rapidly phagocytosed and killed by microbicidal monocytes [4].

The ESX-1 Type VII secretion system was identified as essential for virulence when its loss was determined to be the primary cause of attenuation for the live BCG vaccine strain [9–12]. ESX-1 is crucial for survival within the macrophage during early infection, mediating evasion of bacterial killing and induction of growth-permissive responses. ESX-1 enhances recruitment of macrophages during infection, promoting granuloma formation [13–15]. Within the macrophage, ESX-1 mediates permeabilization of the mycobacterial phagosome [16, 17]. Permeabilization induces the cGAS/STING and AIM2/NLRP3 cytosolic signaling pathways, which promote production of cytokines that may enhance bacterial survival [18–22].

Incorporation of PDIM into host membranes has been proposed to rigidify them, enhancing lysis by ESX-1 [8]. Supporting this hypothesis, multiple groups have observed that loss of PDIM reduces phagosomal permeabilization in M. tuberculosis [23–26]. As the study of M. marinum has provided new insights into PDIM’s role in pathogenesis [4, 7], we set out to determine if this PDIM-ESX-1 interaction was conserved in M. marinum. In this paper, we confirm that as in M. tuberculosis, proper PDIM localization is required for M. marinum to effectively permeabilize macrophage phagosomes.

Results & discussion

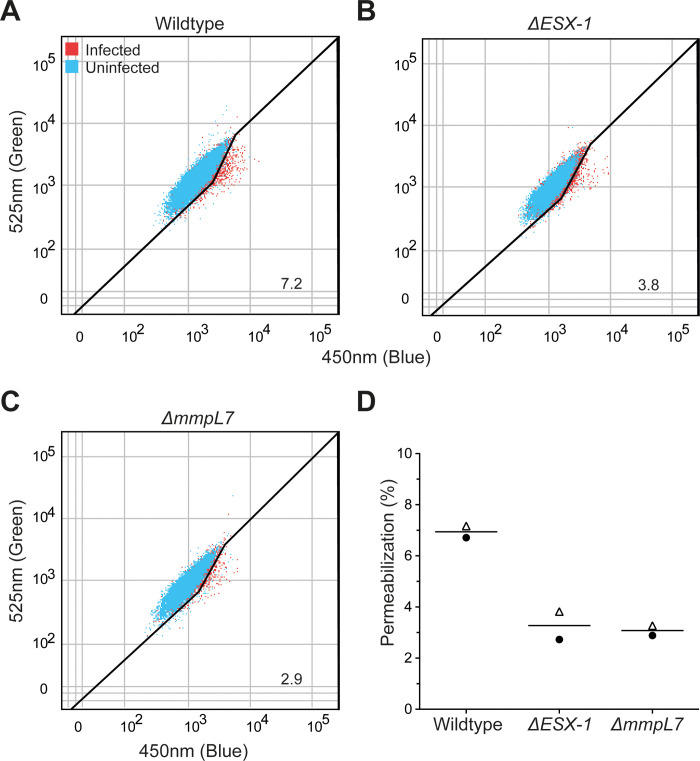

ESX-1 is required for M. marinum and M. tuberculosis to permeabilize macrophage phagosomes during infection [16, 17, 27]. Recent work has shown that ESX-1 and PDIM are both required for permeabilization in M. tuberculosis [23–26]. We set out to determine if phagosomal permeabilization requires PDIM in M. marinum by using an attenuated ΔmmpL7 M. marinum mutant defective in PDIM localization to the mycomembrane [4]. To measure phagosomal permeabilization, we used the fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based dye CCF4-AM as we have done previously [28]. Briefly, the lipophilic dye CCF4-AM is absorbed into the cytosol and is cleaved by cytosolic esterases. The resulting dye is retained in the cytosol and produces a green fluorescent signal (525 nm) upon excitation with a violet laser (405 nm) [17, 29]. When phagosomal permeabilization occurs, the dye becomes accessible to M. marinum. M. marinum is capable of cleaving the dye with its endogenous mycobacterial β-lactamase BlaC, which causes a loss of FRET and an increase in blue fluorescence (450 nm). We used this dye to determine the relative ability of wildtype, ΔESX-1, and ΔmmpL7 M. marinum to permeabilize their phagosomes (Fig 1A–1C). We found that both strains permeabilized their phagosomes less than wildtype M. marinum (Fig 1D). These results show that PDIM is required for M. marinum phagosomal permeabilization, as it is for M. tuberculosis.

Fig 1. PDIM transport to the outer mycomembrane is required for optimal phagosomal permeabilization by M. marinum.

Representative dot plots of (A) wildtype, (B) ΔESX-1, and (C) ΔmmpL7 infected THP-1 macrophages 24 hours post infection with overlays of uninfected (blue) and infected (red) cells within each sample. Gating outlined in black, % permeabilization is as labeled. Plots are representative of two independent experiments. (D) Quantification of permeabilization events. Each point represents an independent experiment, symbols indicate matched experiments.

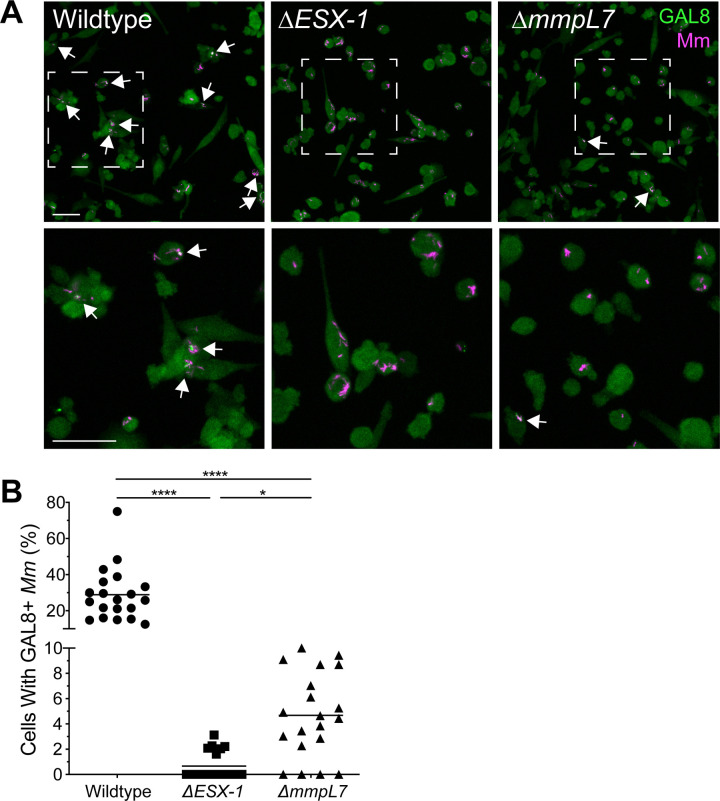

ESX-1-mediated phagosomal permeabilization is associated with membrane damage in both M. tuberculosis and M. marinum [16, 17, 27, 28, 30–32]. M. tuberculosis strains deficient in ESX-1 or PDIM synthesis show reduced galectin-3 or galectin-8 recruitment to intracellular sites of infection [23, 24, 33, 34]. If the endosomal membrane is damaged, cytosolic galectins bind to lumenal β-galactoside-containing glycans that become exposed on damaged vesicles, and can be visualized by immunofluorescence microscopy [23, 24, 33–36]. Differing from the role of ESX-1 in phagosomal permeabilization during M. tuberculosis and M. marinum infection, the involvement of M. marinum PDIM in this process has not been demonstrated.

We next asked if M. marinum PDIM is similarly associated with phagosomal membrane damage. As expected, galectin-8 was readily observed at sites of infection with wildtype M. marinum and was greatly reduced with ΔESX-1 M. marinum (98% lower in ΔESX-1) (Fig 2). ΔmmpL7 M. marinum infection revealed an intriguing result: galectin-8 staining was reduced as compared to wildtype (84% lower in ΔmmpL7), but higher than ΔESX-1. Highlighting its intermediate level of staining, galectin-8 staining was seven times greater in ΔmmpL7 than in ΔESX-1 infection, (Fig 2). These results suggest that like in M. tuberculosis, M. marinum PDIM cooperates with ESX-1 to induce maximum damage to host membranes, with PDIM surface localization as a requirement.

Fig 2. PDIM transport deficiency reduces M. marinum-induced phagosomal membrane damage.

(A) Maximum intensity projections of confocal micrographs showing galectin-8 labeling of PMA-differentiated THP-1 cells infected with tdTomato-expressing wildtype or mutant M. marinum strains 22 hours post infection. Arrows indicate co-localization of Galectin-8 (green) and M. marinum (magenta) fluorescence. Bottom panels show close-up views of the corresponding boxed regions in the top panels. Scale bars, 50μm. (B) Percent of infected cells that have mycobacterial foci labeled with galectin-8. Symbols represent individual imaging fields. Horizontal lines depict mean values. The respective means and 95% confidence intervals for wildtype, ΔESX-1 and ΔmmpL7 infections are 28.9 (22.0–35.8), 0.7 (0.2–1.2), and 4.7 (3.1–6.3). Statistical significance was determined using a Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric test with Dunn’s post-hoc test to control for multiple comparisons, **** p < 0.0001, * p < 0.05. Data are representative of two experiments.

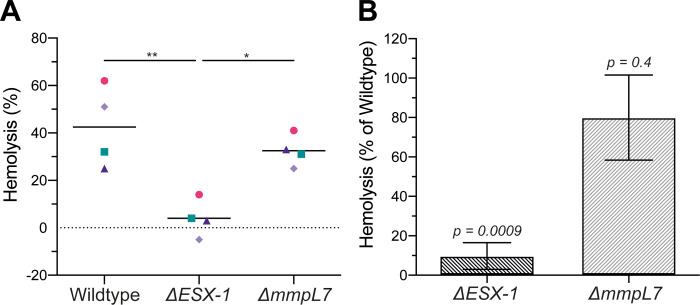

M. tuberculosis and M. marinum both show ESX-1 dependent hemolytic activity [37–39]. Furthermore, loss of hemolytic activity in an M. marinum ΔESX-1 mutant can be rescued by complementing with the M. tuberculosis ESX-1 locus [28]. Historically, hemolysis in M. marinum has been regarded as a correlate of ESX-1 mediated virulence, although recent work suggests that hemolysis can be lost with minimal effects on intramacrophage growth or virulence [28, 38, 40–43]. As phagosomal permeabilization and hemolysis both require host membrane lysis, we set out to determine if the permeabilization-deficient M. marinum ΔmmpL7 were defective in hemolysis as well. As expected, ΔESX-1 had reduced hemolytic activity as compared to wildtype. We saw that ΔmmpL7 had significantly more hemolytic activity than ΔESX-1 (Fig 3). Thus, PDIM does not contribute to hemolysis as much as ESX-1, mirroring its lesser contribution to phagosomal membrane damage as evidenced by galectin-8 staining. The difference between wildtype and ΔmmpL7 hemolysis was not statistically significant (Fig 3). However, the variation in ΔmmpL7 hemolysis across the four experiments precluded determination of whether the mutant had full wildtype levels of hemolytic activity.

Fig 3. PDIM-deficient M. marinum retain hemolytic activity.

(A) 2-hour hemolysis of sheep red blood cells following incubation with wildtype, ΔESX-1 and ΔmmpL7 M. marinum relative to a Triton X-100 control. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post-test. *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, otherwise, p > 0.05. Symbols represent matching experimental replicates. Pink circles, green squares, dark purple triangles and light purple diamonds are the first, second, third, and fourth replicates, respectively. (B) ΔESX-1 and ΔmmpL7 M. marinum hemolysis from (A) normalized to wildtype for each of four experiments. p-values, one-sample t-test against a hypothetical mean of 100% Error bars, mean +/- S.E.M.

In summary, we find that proper PDIM localization enhances ESX-1 dependent phagosomal permeabilization in M. marinum. This matches observations that M. tuberculosis mutants in PDIM localization or synthesis are deficient in phagosomal permeabilization [23–26]. While we have not been able to directly determine the effect of PDIM loss on M. marinum ESX-1 secretion, the finding that M. tuberculosis ΔmmpL7 retains its ESX-1 secretory activity [25] gives confidence that this is the case in M. marinum as well. Our finding that PDIM and ESX-1 contribute to the same extent to phagosomal membrane permeabilization when judged by the CCF4-AM assay, but differ in the galectin-8 phagosomal damage assay, suggests that the latter may be a more sensitive assay.

Finally, the finding that ΔmmpL7 is much more hemolytic than ΔESX-1 indicates that PDIMs contribute differently to M. marinum hemolysis and macrophage membrane damage than ESX-1, or potentially, that hemolysis and macrophage membrane damage have separable requirements. Supporting this hypothesis is the recent observation that the M. marinum ESX-1 substrate MMAR_2894 is required for hemolysis but not ESX-1 mediated cytotoxicity [43], which is associated with phagosomal damage in M. tuberculosis [16, 17]. Ultimately, additional study is required determine the exact contribution of PDIM versus ESX-1 for M. marinum hemolysis, and the degree to which in vitro hemolytic activity shares machinery with phagosomal damage.

Materials & methods

Bacterial strains

Strains are described in Table 1. All strains were derived from wildtype M. marinum purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (strain M, ATCC no. BAA-535). M. marinum ΔESX-1 and ΔmmpL7 were generated as described previously [4, 14]. tdTomato fluorescent strains were generated by transformation with pTEC27 (Addgene plasmid #30182).

Table 1. List of strains used in this study.

Infections, galectin-8 immunofluorescence, and microscopy

2.5 x 105 THP-1 cells were seeded on 24-well optical bottom tissue culture plates (Perkin Elmer, 1450–606), treated with 100nM phorbol 12-myrystate-13-acetate (PMA) (SIGMA, P1585) for two days. PMA-containing media was then removed and replaced with fresh media. Two days later, adherent cells were washed twice with PBS and infected with antibiotic-free media containing single-cell suspensions of tdTomato-expressing M. marinum at a multiplicity of infection of ~1.5 for 4 hours and maintained at 33°C, 5%CO2. 22 hours later, cells were fixed in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS at room temperature for at least 30 minutes.

Galectin-8 staining was based on the method described by Boyle and Randow [44]. Fixed cells were washed twice with PBS and then incubated in permeabilization/block (PB) solution (0.1% Triton-X 100, 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS) for 30 minutes at room temperature, and then stained with goat anti-human galectin-8 antibody (R&D Systems, AF1305) diluted in PB solution overnight at 4°C. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and stained with AlexaFluor488-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (ThermoFisher, A-11055) diluted in PB solution for one hour at room temperature. Cells were then washed three times and kept in PBS for imaging.

A Nikon A1R laser scanning confocal microscope fitted with a 20x Plan Apo 0.75 NA objective was used to generate 2048 x 2048 pixel 8μm z-stacks consisting of 1μm optical sections. Image acquisition was carried out using a galvano scanner, 488nm and 561nm lasers, and a GaAsP multi-detector unit. Maximum intensity projections were generated in NIS Elements (Nikon) and used to calculate the percentage of THP-1 cells containing mycobacterial foci labeled with galectin-8 per imaging field.

CCF-4 assay & flow cytometry

CCF-4 assay was conducted as previously described [28], with minor modifications. Briefly, 1 x 106 THP-1 cells were seeded on 12-well tissue culture plates and treated with 33 nM PMA for three days. Cells were then washed with media and then infected with single-cell suspensions of tdTomato-expressing wildtype, ΔESX-1, or ΔmmpL7 M. marinum at a MOI of 1 for 4 h at 33°C in EM medium. 24 hours post infection cells were stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor660 (eBioscience). Cells were then harvested and stained for 1h at room temperature with 8 μM CCF4-AM (Invitrogen) in EM medium supplemented with 2.5 μM probenecid. Finally, cells were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde. Cells were analyzed in an LSRFortessa II cytometer, using FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences). At least 40,000 events per sample were collected. Data were analyzed using FlowJo (Treestar). Permeabilization percentage among infected monocytes was calculated using a region defined by an increased 450 nm signal (indicating CCF4 dye cleavage and, therefore phagosomal permeabilization) relative to uninfected cells in the same sample. Events in this region were designated “permeabilized”. Percent permeabilization was then calculated as a ratio of events in the permeabilized field over total live and infected cells.

Hemolysis assay

Hemolysis assays were conducted as previously described [28]. Briefly, defibrinated sheep red blood cells (RBCs) (Fisher Scientific) were washed twice and diluted to 1% (vol/vol) in PBS. Mycobacteria were grown in complete 7H9 media at 33°C to OD600 ~1.5, washed twice with PBS, and resuspended to ~30 OD units/mL. 100 μL M. marinum were mixed with 100 μL 1% RBC in a micro-centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 5000 x g for 5 minutes, then incubated at 33°C for 2 hours. Pellets were then resuspended, centrifuged at 5000 x g for 5 minutes and the A405 measured of 100 μL supernatant. PBS treatment was used as a negative control (background lysis) and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) as a positive control (complete lysis). Hemolysis was calculated as percentage of detergent lysis after subtracting background lysis.

Supporting information

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keith Boyle for advice on galectin-8 staining, and T. Kaewen Dang for proofreading of the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

Dr. Osman, Dr. Pagán, and Dr. Shanahan were supported by both the NIH R37AI054503 and Wellcome Trust 103950/Z/14/Z awards to Prof. Ramakrishnan. In addition, Dr. Shanahan had his own Wellcome Trust Grant 105388/Z/14/Z. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Cambier CJ, Falkow S, Ramakrishnan L. Host Evasion and Exploitation Schemes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell. 2014;159: 1497–1509. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox JS, Chen B, McNeil M, Jacobs WR. Complex lipid determines tissue-specific replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in mice. Nature. 1999;402: 79–83. 10.1038/47042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camacho LR, Ensergueix D, Perez E, Gicquel B, Guilhot C. Identification of a virulence gene cluster of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by signature-tagged transposon mutagenesis. Molecular Microbiology. 1999;34: 257–267. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambier CJ, Takaki KK, Larson RP, Hernandez RE, Tobin DM, Urdahl KB, et al. Mycobacteria manipulate macrophage recruitment through coordinated use of membrane lipids. Nature. 2013;505: 218–222. 10.1038/nature12799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Lanéelle M-A, Triccas JA, Gicquel B, et al. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J Biol Chem. 2001;276: 19845–19854. 10.1074/jbc.M100662200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ates LS, Ummels R, Commandeur S, van de Weerd R, van der Weerd R, Sparrius M, et al. Essential Role of the ESX-5 Secretion System in Outer Membrane Permeability of Pathogenic Mycobacteria. Viollier PH, editor. PLoS genetics. 2015;11: e1005190 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cambier CJ, Banik S, Buonomo JA, Bertozzi C. Spreading of a virulence lipid into host membranes promotes mycobacterial pathogenesis. bioRxiv. 2019. [cited 13 Dec 2019]. 10.1101/845081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Augenstreich J, Haanappel E, Ferré G, Czaplicki G, Jolibois F, Destainville N, et al. The conical shape of DIM lipids promotes Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of macrophages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116: 25649–25658. 10.1073/pnas.1910368116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahairas GG, Sabo PJ, Hickey MJ, Singh DC, Stover CK. Molecular analysis of genetic differences between Mycobacterium bovis BCG and virulent M. bovis. Journal of bacteriology. 1996;178: 1274–82. 10.1128/jb.178.5.1274-1282.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Behr MA, Wilson MA, Gill WP, Salamon H, Schoolnik GK, Rane S, et al. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science (New York, NY). 1999;284: 1520–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis KN, Liao R, Guinn KM, Hickey MJ, Smith S, Behr MA, et al. Deletion of RD1 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mimics Bacille Calmette-Guérin Attenuation. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2003;187: 117–123. 10.1086/345862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pym AS, Brodin P, Brosch R, Huerre M, Cole ST. Loss of RD1 contributed to the attenuation of the live tuberculosis vaccines Mycobacterium bovis BCG and Mycobacterium microti. Molecular Microbiology. 2002;46: 709–717. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03237.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis JM, Ramakrishnan L. The Role of the Granuloma in Expansion and Dissemination of Early Tuberculous Infection. Cell. 2009;136: 37–49. 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volkman HE, Clay H, Beery D, Chang JCW, Sherman DR, Ramakrishnan L. Tuberculous granuloma formation is enhanced by a mycobacterium virulence determinant. PLoS biology. 2004;2: e367 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkman HE, Pozos TC, Zheng J, Davis JM, Rawls JF, Ramakrishnan L. Tuberculous Granuloma Induction via Interaction of a Bacterial Secreted Protein with Host Epithelium. Science. 2010;327: 466–469. 10.1126/science.1179663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Wel N, Hava D, Houben D, Fluitsma D, van Zon M, Pierson J, et al. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell. 2007;129: 1287–98. 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simeone R, Bobard A, Lippmann J, Bitter W, Majlessi L, Brosch R, et al. Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. Ehrt S, editor. PLoS pathogens. 2012;8: e1002507“. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lienard J, Nobs E, Lovins V, Movert E, Valfridsson C, Carlsson F. The Mycobacterium marinum ESX-1 system mediates phagosomal permeabilization and type I interferon production via separable mechanisms. PNAS. 2019. [cited 3 Jan 2020]. 10.1073/pnas.1911646117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wassermann R, Gulen MFF, Sala C, Perin SGG, Lou Y, Rybniker J, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Differentially Activates cGAS- and Inflammasome-Dependent Intracellular Immune Responses through ESX-1. Cell Host & Microbe. 2015;17: 799–810. 10.1016/j.chom.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen SB, Gern BH, Delahaye JL, Adams KN, Plumlee CR, Winkler JK, et al. Alveolar Macrophages Provide an Early Mycobacterium tuberculosis Niche and Initiate Dissemination. Cell Host & Microbe. 2018;24: 439-446.e4. 10.1016/j.chom.2018.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreira-Teixeira L, Mayer-Barber K, Sher A, O’Garra A. Type I interferons in tuberculosis: Foe and occasionally friend. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2018;215: 1273–1285. 10.1084/jem.20180325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stanley SA, Johndrow JE, Manzanillo P, Cox JS. The Type I IFN Response to Infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis Requires ESX-1-Mediated Secretion and Contributes to Pathogenesis. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178: 3143–3152. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Augenstreich J, Arbues A, Simeone R, Haanappel E, Wegener A, Sayes F, et al. ESX-1 and phthiocerol dimycocerosates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis act in concert to cause phagosomal rupture and host cell apoptosis. Cellular Microbiology. 2017; 1–19. 10.1111/cmi.12726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerner TR, Queval CJ, Fearns A, Repnik U, Griffiths G, Gutierrez MG. Phthiocerol dimycocerosates promote access to the cytosol and intracellular burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in lymphatic endothelial cells. BMC Biology. 2018;16: 1 10.1186/s12915-017-0471-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quigley J, Hughitt VK, Velikovsky CA, Mariuzza RA, El-Sayed NM, Briken V. The Cell Wall Lipid PDIM Contributes to Phagosomal Escape and Host Cell Exit of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. mBio. 2017;8: e00148–17. 10.1128/mBio.00148-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barczak AK, Avraham R, Singh S, Luo SS, Zhang WR, Bray M-A, et al. Systematic, multiparametric analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis intracellular infection offers insight into coordinated virulence. PLOS Pathogens. 2017;13: e1006363 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manzanillo PS, Shiloh MU, Portnoy DA, Cox JS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Activates the DNA-Dependent Cytosolic Surveillance Pathway within Macrophages. Cell Host & Microbe. 2012;11: 469–480. 10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conrad WH, Osman MM, Shanahan JK, Chu F, Takaki KK, Cameron J, et al. Mycobacterial ESX-1 secretion system mediates host cell lysis through bacterium contact-dependent gross membrane disruptions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114: 1371–1376. 10.1073/pnas.1620133114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller C, Mellouk N, Danckaert A, Simeone R, Brosch R, Enninga J, et al. Single cell measurements of vacuolar rupture caused by intracellular pathogens. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE. 2013; e50116 10.3791/50116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watson RO, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS. Extracellular M. tuberculosis DNA Targets Bacteria for Autophagy by Activating the Host DNA-Sensing Pathway. Cell. 2012;150: 803–815. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López-Jiménez AT, Cardenal-Muñoz E, Leuba F, Gerstenmaier L, Barisch C, Hagedorn M, et al. The ESCRT and autophagy machineries cooperate to repair ESX-1-dependent damage at the Mycobacterium-containing vacuole but have opposite impact on containing the infection. PLOS Pathogens. 2018;14: e1007501 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mittal E, Skowyra ML, Uwase G, Tinaztepe E, Mehra A, Köster S, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Type VII Secretion System Effectors Differentially Impact the ESCRT Endomembrane Damage Response. mBio. 2018;9 10.1128/mBio.01765-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wong K-W, Jacobs WR. Critical role for NLRP3 in necrotic death triggered by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cellular microbiology. 2011;13: 1371–84. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01625.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chauhan S, Kumar S, Jain A, Ponpuak M, Mudd MH, Kimura T, et al. TRIMs and Galectins Globally Cooperate and TRIM16 and Galectin-3 Co-direct Autophagy in Endomembrane Damage Homeostasis. Developmental Cell. 2016;39: 13–27. 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyle KB, Randow F. The role of ‘eat-me’ signals and autophagy cargo receptors in innate immunity. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2013;16: 339–348. 10.1016/j.mib.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jia J, Abudu YP, Claude-Taupin A, Gu Y, Kumar S, Choi SW, et al. Galectins Control mTOR in Response to Endomembrane Damage. Molecular Cell. 2018;70: 120-135.e8. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.King CH, Mundayoor S, Crawford JT, Shinnick TM. Expression of contact-dependent cytolytic activity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and isolation of the genomic locus that encodes the activity. Infection and Immunity. 1993;61: 2708–2712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao L-Y, Guo S, McLaughlin B, Morisaki H, Engel JN, Brown EJ. A mycobacterial virulence gene cluster extending RD1 is required for cytolysis, bacterial spreading and ESAT-6 secretion. Molecular microbiology. 2004;53: 1677–93. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04261.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speer A, Sun J, Danilchanka O, Meikle V, Rowland JL, Walter K, et al. Surface hydrolysis of sphingomyelin by the outer membrane protein Rv0888 supports replication of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages. Molecular microbiology. 2015;97: 881–97. 10.1111/mmi.13073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith J, Manoranjan J, Pan M, Bohsali A, Xu J, Liu J, et al. Evidence for Pore Formation in Host Cell Membranes by ESX-1-Secreted ESAT-6 and Its Role in Mycobacterium marinum Escape from the Vacuole. Infect Immun. 2008;76: 5478–5487. 10.1128/IAI.00614-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phan TH, Leeuwen LM van, Kuijl C, Ummels R, Stempvoort G van, Rubio-Canalejas A, et al. EspH is a hypervirulence factor for Mycobacterium marinum and essential for the secretion of the ESX-1 substrates EspE and EspF. PLOS Pathogens. 2018;14: e1007247 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kennedy GM, Hooley GC, Champion MM, Mba Medie F, Champion PAD. A novel ESX-1 locus reveals that surface-associated ESX-1 substrates mediate virulence in Mycobacterium marinum. Journal of bacteriology. 2014;196: 1877–88. 10.1128/JB.01502-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bosserman RE, Nicholson KR, Champion MM, Champion PA. A New ESX-1 Substrate in Mycobacterium marinum That Is Required for Hemolysis but Not Host Cell Lysis. Journal of Bacteriology. 2019;201: e00760–18. 10.1128/JB.00760-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boyle KB, Randow F. Measuring Antibacterial Autophagy. Autophagy. 2019; 679–690. 10.1007/978-1-4939-8873-0_45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(XLSX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.