Abstract

There is an urgent need for vaccines against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) because of the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Among all approaches, a messenger RNA (mRNA)-based vaccine has emerged as a rapid and versatile platform to quickly respond to this challenge. Here, we developed a lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA (mRNA-LNP) encoding the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 as a vaccine candidate (called ARCoV). Intramuscular immunization of ARCoV mRNA-LNP elicited robust neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 as well as a Th1-biased cellular response in mice and non-human primates. Two doses of ARCoV immunization in mice conferred complete protection against the challenge of a SARS-CoV-2 mouse-adapted strain. Additionally, ARCoV is manufactured as a liquid formulation and can be stored at room temperature for at least 1 week. ARCoV is currently being evaluated in phase 1 clinical trials.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, mRNA vaccine, lipid nanoparticle, mouse-adapted strain, non-human primate, protection

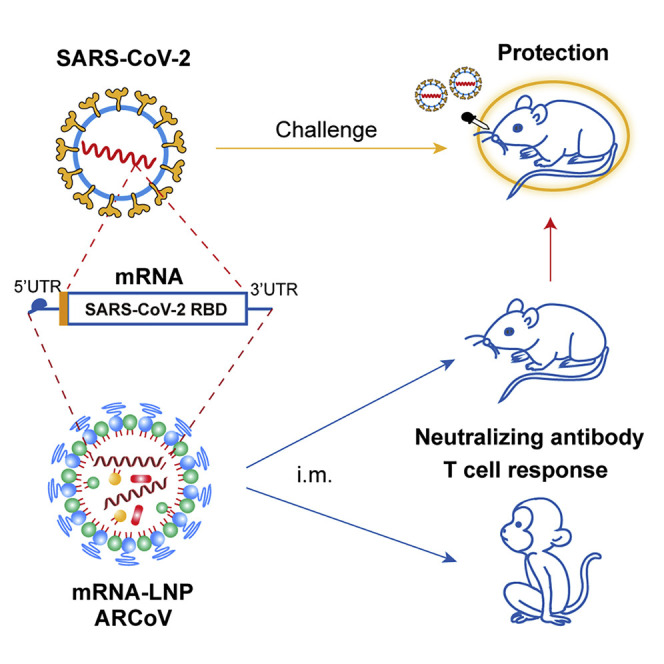

Graphical Abstract

ARCoV is an LNP-encapsulated mRNA vaccine platform that is highly immunogenic and safe in mice and non-human primates, conferring protection against challenge with a SARS-CoV-2 mouse-adapted strain.

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel human coronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV (Wu et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020b), has spread throughout the world and is causing global public health crises. The clinical manifestations caused by SARS-CoV-2 range from non-symptomatic infection to mild flu-like symptoms, pneumonia, severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, and even death (Huang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). To date, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has resulted in more than 3.5 million cases with over 250,000 deaths (World Health Organization). So far, no effective treatment is available. Therefore, development of a safe and effective vaccine against COVID-19 is urgently needed.

SARS-CoV-2, together with the other two highly pathogenic human coronaviruses, SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-CoV, belongs to the genus Betacoronavirus of the family Coronaviridae. Coronaviruses are enveloped positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses, and the virion is composed of a helical capsid formed by nucleocapsid (N) proteins bound to the RNA genome and an envelope made up of membrane (M) and envelope (E) proteins, coated with a “crown”-like trimeric spike (S) protein. Like other human coronaviruses, the full-length S protein of SARS-CoV-2 consists of S1 and S2 subunits. First, the S protein mediates viral entry into host cells by binding to its receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), through the receptor-binding domain (RBD) at the C terminus of the S1 subunit, which subsequently causes fusion between the viral envelope and the host cell membrane through the S2 subunit (Hoffmann et al., 2020). The full-length S protein, S1, and RBD are capable of inducing highly potent neutralizing antibodies and T cell-mediated immunity and, therefore, have been widely selected as promising targets for coronavirus vaccine development (Amanat and Krammer, 2020). Some recent studies also demonstrated that immunization with the recombinant RBD of SARS-CoV-2 induced high titers of neutralizing antibodies in the absence of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of infection (Quinlan et al., 2020; Tai et al., 2020). The structures of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD alone and the RBD-ACE2 and RBD-monoclonal antibody complexes were resolved in record time at high resolution (Lan et al., 2020; Shang et al., 2020; Walls et al., 2020), which further improves our understanding of this vaccine target.

Messenger RNA (mRNA)-based therapy recently emerged as an effective platform for treatment of infectious diseases and cancer (Jackson et al., 2020; Mascola and Fauci, 2020). In the past few years, with technological advances in mRNA modification and delivery tools (Ickenstein and Garidel, 2019; Maruggi et al., 2019; Pardi et al., 2020), the mRNA vaccine field has developed extremely rapidly in basic and clinical research. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that mRNA-based vaccines induce potent and broadly protective immune responses against various pathogens in small and large animals, with an acceptable safety profile (Maruggi et al., 2019). To date, clinical trials for mRNA vaccines against viral diseases, including Zika, Ebola, influenza, rabies, and cytomegalovirus infection, have been carried out in many countries (Alameh et al., 2020). One of the key advantages of the mRNA vaccine platform is its capability of scalable production within a very short period of time, which makes it very attractive for responding to the pandemic. mRNA manufacturing avoids the lengthy process of cell culture and purification and the stringent biosafety measures for traditional virus vaccine production. A clinical-scale mRNA vaccine can be designed and manufactured rapidly, within weeks, when the viral antigen sequence becomes available. In March 2020, it took only 42 days for Moderna’s mRNA-1273 to enter phase I clinical trials as the very first mRNA vaccine against COVID-19 in the United States (NCT04283461). Several other SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine candidates are currently in development worldwide, which further proves the high potential of the mRNA vaccine platform. However, none of these mRNA vaccines at the clinical stage have been evaluated in animal models; the mechanisms of mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 are unclear, and their effectiveness has yet to be proven (Jiang, 2020). In the present study, we demonstrate immunogenicity and protection of a novel mRNA vaccine candidate (called ARCoV) against SARS-CoV-2 in animal models, which supports further clinical development in humans.

Results

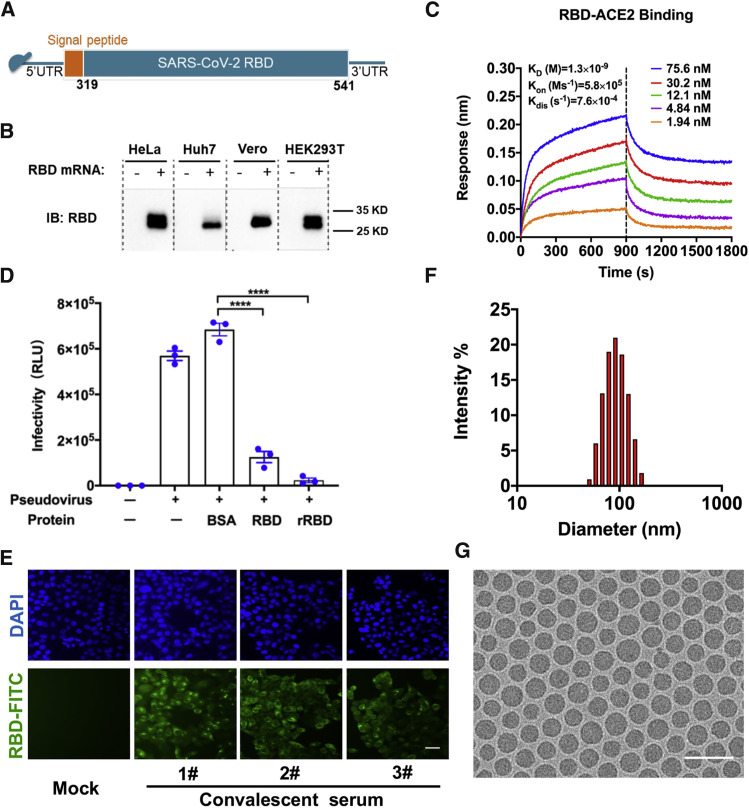

Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are one of the most appealing and commonly used mRNA delivery tools (Ickenstein and Garidel, 2019). Here we developed a vaccine platform based on modified mRNA encapsulated in LNPs for in vivo delivery. The RBD of SARS-CoV-2 (amino acids [aa] 319–541) was chosen as the target antigen for the mRNA coding sequence (Figure S1 ), as shown in Figure 1 A. Transfection of the RBD-encoding mRNA in multiple cell lines (HeLa, Huh7, HEK293T, and Vero) resulted in high expression of recombinant RBD in culture supernatants (Figure 1B), with up to 917.4 ng/mL of RBD in mRNA-transfected HEK293F cells (Figure S2 A). RBD protein expressed from mRNA retained high affinity for recombinant human ACE2, as demonstrated by kinetics analysis using ForteBio Octet (Figure 1C), and functionally inhibited entry of a vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-based pseudovirus expressing the SARS-CoV-2 S protein (Nie et al., 2020) in Huh7 cells (Figure 1D). Immunostaining further demonstrated that this RBD protein can be recognized by a panel of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against SARS-CoV-2 RBD (Figure S2B) as well as convalescent sera from three COVID-19 patients (Figure 1E).

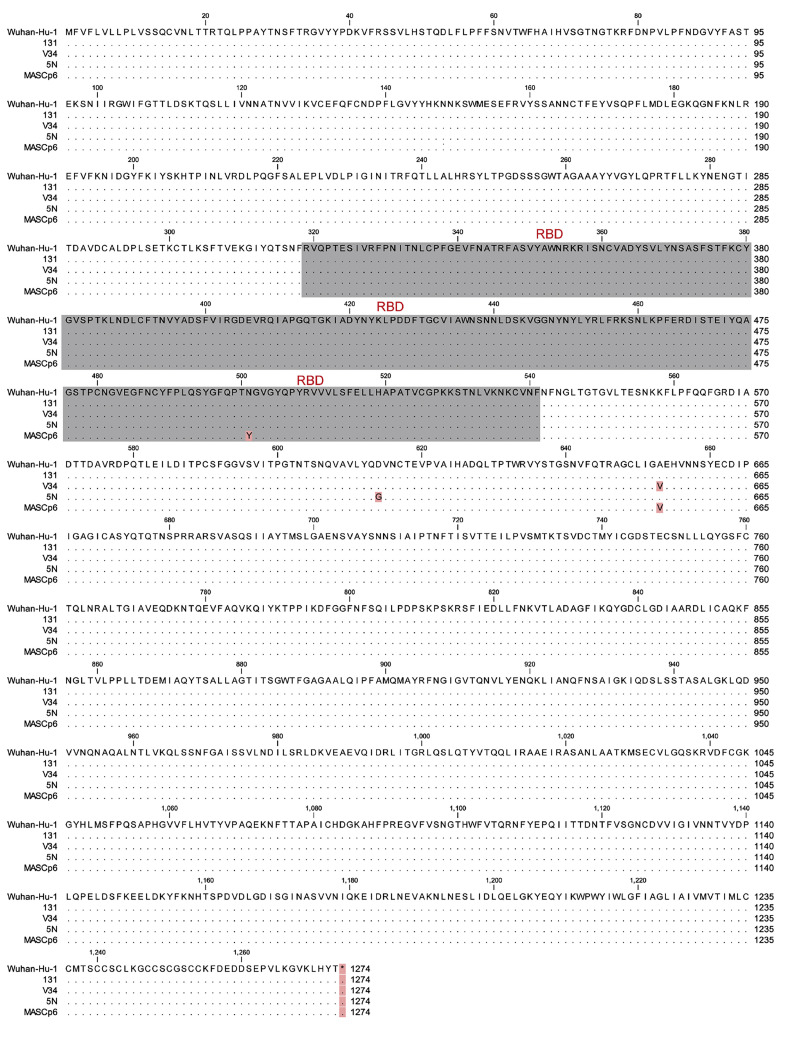

Figure S1.

Amino Acid Sequence Alignment of the Full S Protein of SARS-CoV-2 Isolates Used in This Study, Related to Figures 1 and 3

Invariant residues are shown as black dots. RBD sequences are shown in gray. Variant mutations are marked in light red.

Figure 1.

Design and Encapsulation of mRNA Encoding the SARS-CoV-2 RBD

(A) The mRNA construct of ARCoV expressing the SARS-CoV-2 RBD.

(B) RBD protein expression from mRNA in HeLa, Huh7, Vero, or HEK293T cells. Cells were transfected with RBD-encoding mRNA (2 μg/mL), and immunoblotting was performed at 48 h after transfection. See also Figure S1.

(C) Real-time association and dissociation of the RBD protein with biotin-ACE2.

(D) Inhibition of cell entry of the SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus by the mRNA-encoded RBD protein. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; unpaired t test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(E) Immunofluorescence staining of the mRNA-encoded RBD protein with convalescent sera from three COVID-19 patients. Scale bar, 50 μm.

(F) Representative intensity-size graph of ARCoV measured by dynamic light-scattering method.

(G) Cryo-TEM image of ARCoV mRNA-LNP. Scale bar, 200 nm.

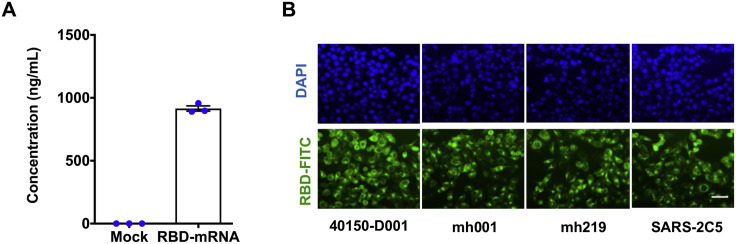

Figure S2.

Characterization of Expression of the RDB Encoding mRNA, Related to Figure 1

(A) RBD expression in transfected HEK293F cells determined by ELISA.

(B) Immunofluorescence analysis of RBD expression (FITC, green) in HeLa cells. HeLa cells were transfected with RBD mRNA (2 μg/ml), and RBD expression was detected with a panel of SARS-CoV-2 specific monoclonal antibodies at 24 hours post transfection. Nuclei was stained using Hhechst (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm.

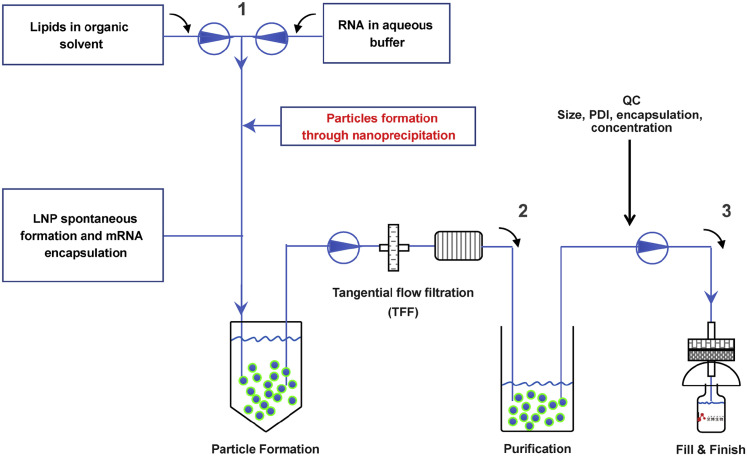

The mRNA-LNP formulations were prepared using a modified procedure, as described previously for small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Semple et al., 2010), followed by tangential flow filtration and purification before being filled into sterile glass vials (Figure S3 ). The characterization of representative batches of mRNA-LNP is shown in Table S1. The final stock of SARS-CoV-2 RBD encoding mRNA-LNP (ARCoV), manufactured under good manufacturing practice (GMP) conditions, showed an average particle size of 88.85 nm (Figure 1F) with more than 95% encapsulation. Cryo-transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis showed that ARCoV particles exhibit homogeneous morphologies of solid spheres that lack an aqueous core (Figure 1G), which demonstrates a key difference between RNA-loaded LNPs and conventional liposomes.

Figure S3.

Flow Sheet of mRNA-LNP Manufacture, Related to Figure 1

ARCoV is manufactured through rapid mixing of mRNA in aqueous solution and a mixture of lipids in ethanol. This process yields self-assembled LNPs with mRNA encapsulated inside. Tangential flow filtration was used to remove ethanol and to concentrate the solution. Following the Quality Control (QC) procedure, the final product was filtered into sterilized glass syringes or glass vials.

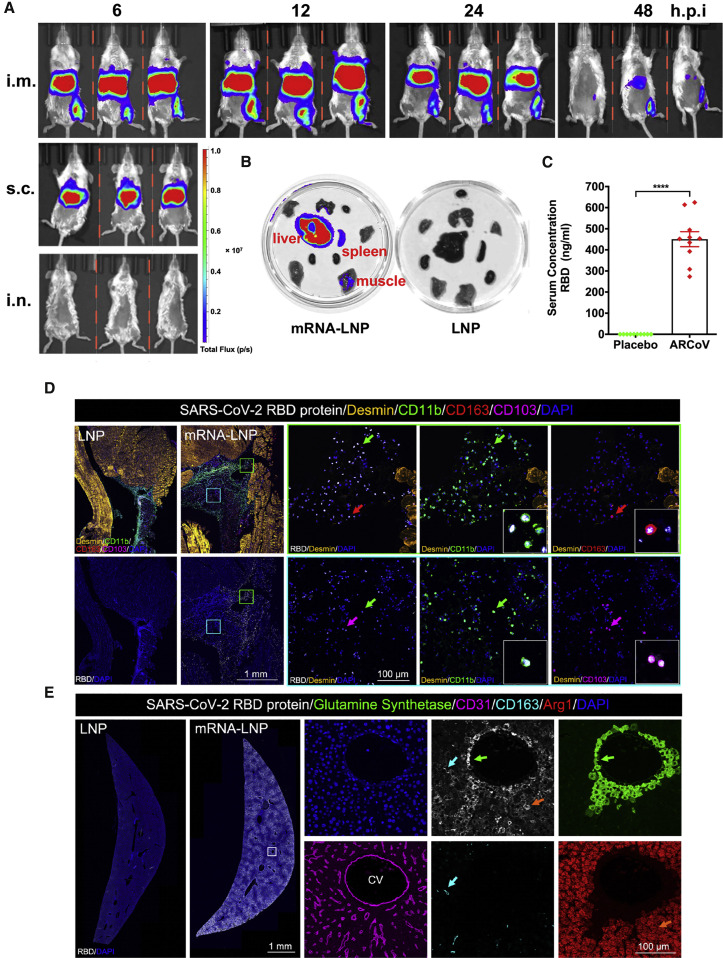

Next we evaluated the in vivo delivery capability of ARCoV in mice. To visualize the tissue distribution of our mRNA-LNP formulations, a firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporter encoding mRNA-LNP was prepared, using the same procedure as for ARCoV (Table S1), and subjected to bioluminescence imaging (BLI) analysis using different immunization routes. Following intramuscular (i.m.) injection, robust expression of FLuc was seen in the upper abdomen as well as at the injection site in BALB/c mice 6 h after injection (Figure 2 A). Subcutaneous (s.c.) injection also led to robust FLuc expression in the upper abdomen, whereas no signal was detected in mice receiving intranasal (i.n.) inoculation. Real-time monitoring of i.m. immunized mice showed that photon flux peaked 12 h after injection and faded to undetectable levels 48 h after injection in the upper abdomen and at the injection site. Further ex vivo imaging analysis of ARCoV-immunized BALB/c mice showed that the liver was the most abundant RBD-expressing tissue, and a slightly luminescent signal was also detected in the spleen and muscle tissues (Figure 2B). Additionally, following intravenous (i.v.) administration of ARCoV mRNA-LNP at 1 mg/kg, expression of the RBD was readily detectable by ELISA 6 h after injection, with an average concentration of 450.6 ng/mL in ICR mouse serum (Figure 2C). Furthermore, to identify the primary cell types in which the encapsulated mRNAs were translated into antigen, muscle from the injection site and liver were collected from ARCoV mRNA-LNP- and placebo LNP-immunized mice and subjected to multiplex immunofluorescence staining of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD and different immune cell markers. Robust expression of the SARS-CoV-2 RBD was detected in muscle samples collected from the i.m. injection site of ARCoV-inoculated mice, which were mostly colocalized with CD11b-positive monocytes as well as CD163-positive macrophages and CD103-positive dendritic cells in muscle samples from vaccine-immunized mice (Figure 2D). As expected, no RBD expression was seen in muscle tissue from placebo-LNP treated mice, and LNPs also stimulated massive infiltration of monocytes and macrophages, which functioned as adjuvants, as described previously (Maugeri et al., 2019). Furthermore, colocalization of SARS-CoV-2 RBD- and CD11b-positive monocytes was also detected within i.m. lymph nodes from ARCoV mRNA-LNP-inoculated mice (Figure S4 ). Abundant SARS-CoV-2 RBDs were also detected in livers from ARCoV-immunized mice (Figure 2E), which agreed with the in vivo and ex vivo luciferase expression profiles (Figures 2A and 2B). Further analyses also showed that the SARS-CoV-2 RBD fluorescence signal primarily overlapped with glutamine synthetase-positive pericentral hepatocytes surrounding the CD31-positive central vein (CV), Arg1-positive hepatocytes, as well as CD163-positive liver macrophages (Figure 2E). These results highlight the capability of our mRNA-LNP formulations to deliver mRNA in vivo and recruit antigen-presenting cells to process the expressed antigens.

Figure 2.

In Vivo Delivery of ARCoV mRNA-LNP Formulation

(A) In vivo BLI of reporter mRNA-LNP in mice. Female BALB/c mice were inoculated with 10 μg of FLuc-encoding reporter mRNA-LNP via different routes and subjected to IVIS Spectrum imaging at the indicated times after administration.

(B) Tissue distribution of reporter mRNA-LNP in mice. Empty LNP was employed as a control.

(C) Expression of the mRNA-encoded RBD in mice. The serum concentration of the RBD was measured by ELISA 6 h after inoculation. Data are shown as mean ± SEM and analyzed using unpaired t test. ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001.

(D) Multiplex immunostaining analysis for expression of LNP-delivered mRNA in mouse muscle tissues. Female BALB/c mice (n = 3) were immunized with 10 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP, and empty LNP was used as a control (n = 3). Muscle tissue at the injection site was collected 6 h after injection and subjected to multiplex immunofluorescent staining for SARS-CoV-2 RBD (white) as well as other cell markers, including Desmin (gold), CD11b (green), CD163 (red), and CD103 (magenta). Magnifications of the areas boxed in white are shown on the right. Arrows indicate double-positive-stained cells. See also Figure S4.

(E) The expression of LNP-delivered mRNA in mouse liver. Liver tissue collected 6 h after injection was stained for the SARS-CoV-2 RBD (white) and multiple cell markers for glutamine synthetase (green), CD31 (magenta), CD163 (cyan), and Arg1 (red). Magnifications of the areas boxed in white are shown on the right. Arrows indicate the double-positive-stained cells. CV, central vein.

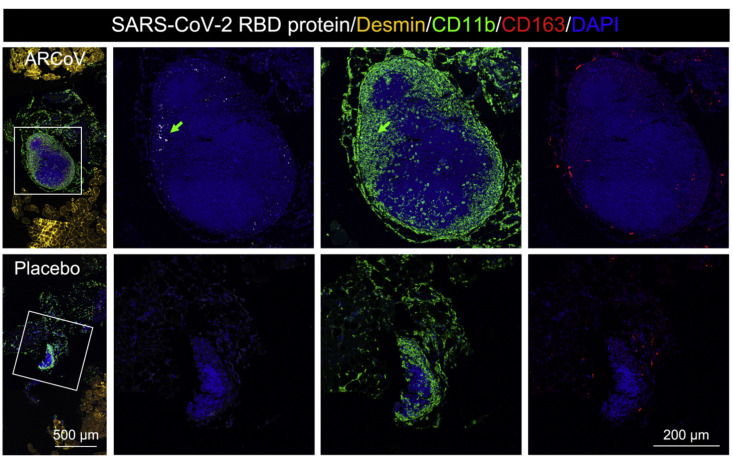

Figure S4.

SARS-CoV-2 RBD Expression Profile in Muscle Tissue of ARCoV-Immunized Mice, Related to Figure 2

Intramuscular injection of ARCoV induced local RBD expression in intramuscular lymph nodes. Multiplex immunofluorescent staining of intramuscular injection sites showed SARS-CoV-2 RBD and CD11b-positive monocytes expression in the intramuscular lymph nodes of the ARCoV mRNA-LNP -inoculated mice. Scale bar: 500 μm. Magnifications of the areas boxed in white are shown on the right. Colored arrows indicate the double-stained cells that are magnified beside. Scale bar: 200 μm.

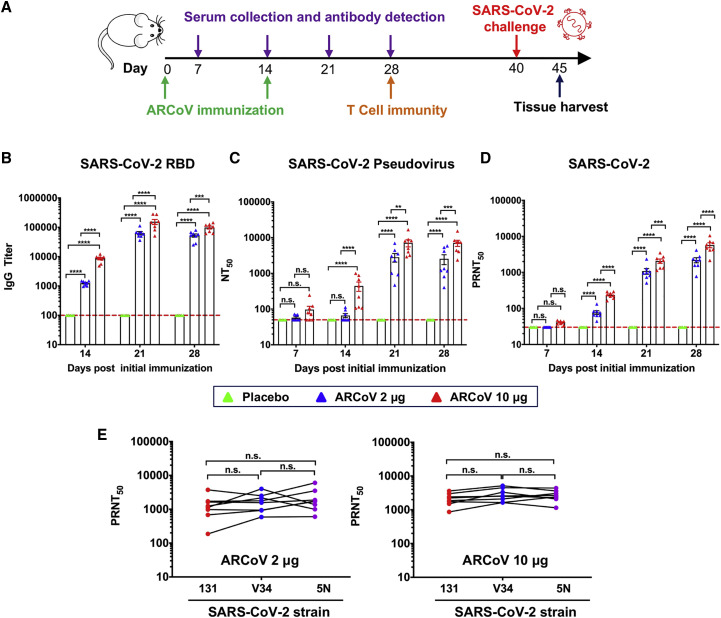

We also determined the immunogenicity and efficacy of ARCoV mRNA-LNP in animals. Initially, groups of immunocompetent female BALB/c mice were immunized with a single dose of ARCoV mRNA-LNP via i.m. administration; empty LNPs were used as a placebo. Following immunization, no local inflammation response at the injection site or other adverse effects were observed during the observation period. A single immunization with ARCoV mRNA-LNP (2 and 30 μg) induced production of SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific IgG antibodies (Figure S5 A) and neutralizing antibodies with 50% neutralization titer (NT50) approached ∼1/278 and ∼1/559 28 days after immunization (Figure S5B), which was lower than the neutralizing antibody levels in convalescent serum from selected COVID-19 patients (Ni et al., 2020). Next, groups of mice were immunized with 2 or 10 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP and boosted with the same dose on day 14, and sera were collected 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after initial vaccination and subjected to antibody assays (Figure 3 A). Remarkably, a second immunization with 2 or 10 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP resulted in rapid elevation of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and neutralizing antibodies in mice (Figures 3B–3D), whereas no SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies were detected in sera from mice vaccinated with empty LNPs. 28 days after initial immunization, the NT50 titers in mice immunized with 2 or 10 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP approached ∼1/2,540 and ∼1/7,079, respectively (Figure 3C), and the PRNT50 reached ∼1/2,194 and ∼1/5,704, respectively (Figure 3D). Recent genome surveillance recorded novel epidemic SARS-CoV-2 strains with specific mutations in the S protein, which was potentially associated with virus transmission and pathogenesis (Becerra-Flores and Cardozo, 2020; Korber et al., 2020). Thus, we further evaluated whether mouse serum after ARCoV mRNA-LNP vaccination could cross-neutralize different epidemic strains of SARS-CoV-2 (Table S2). All three epidemic strains used in this study shared the same RBD sequence as our mRNA vaccine, whereas 5N and V34 contained a unique D614G and A653V substitution in the S protein, respectively (Figure S1). As expected, sera from all ARCoV vaccinated mice showed a similar neutralizing capability against all three SARS-CoV-2 epidemic strains, and there was no significant difference in PRNT50 titers (Figure 3E). Together, our results demonstrate that two doses of immunization of ARCoV vaccine induce high levels of antibodies with broad neutralizing capabilities against SARS-CoV-2 in mice.

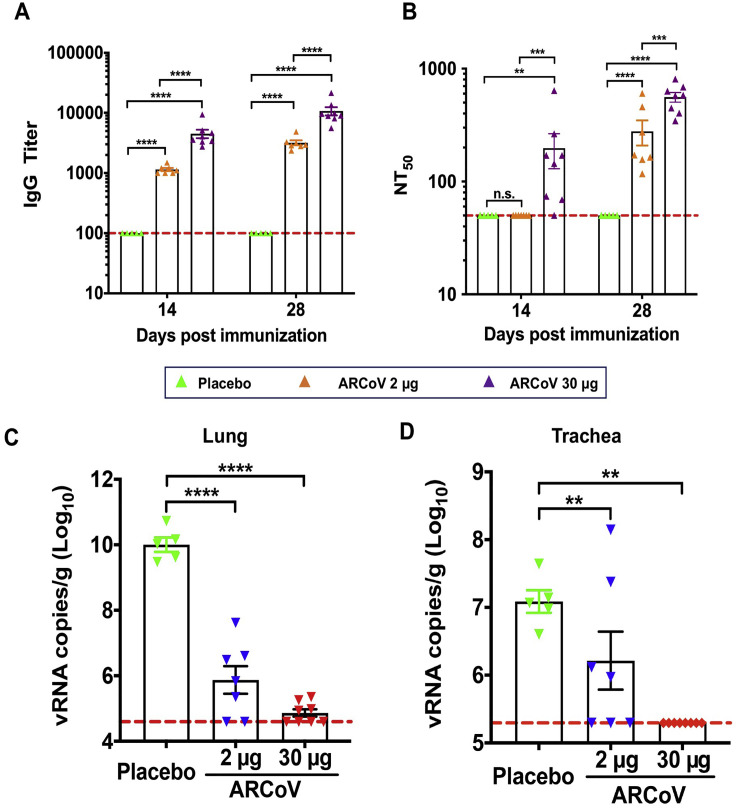

Figure S5.

Immunogenicity and Protection of a Single Dose of ARCoV in Mice, Related to Figure 3

BALB/c mice were intramuscularly immunized with 2 μg (n = 7) or 30 μg (n = 8) of the ARCoV vaccine or Placebo (n = 5). Serum was collected at 14, 28 days post immunization and analyzed by ELISA (A) and pseudovirus neutralization assay (B). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated using a two-way ANOVA with multiple comparison tests (n.s., not significant; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Six to eight weeks after immunization, all immunized mice were inoculated intranasally with the SARS-CoV-2 mouse-adapted strain MASCp6, and their lungs (C) and trachea (D) were collected for detection of viral RNA loads at 5 days post challenge. Data are shown as mean ± SEM; Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparison tests. (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Figure 3.

Humoral Immune Response in ARCoV-Vaccinated Mice

Female BALB/c mice were immunized i.m. with 2 μg (n = 8) or 10 μg (n = 8) of ARCoV or a placebo (n = 5) and boosted with an equivalent dose 14 days later. Serum was collected 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after initial vaccination.

(A) Schematic diagram of immunization, sample collection, and challenge schedule.

(B) The SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibody titer was determined by ELISA.

(C and D) NT50 and PRNT50 were determined using VSV-based pseudovirus and infectious SARS-CoV-2, respectively. The dashed lines indicate the detection limit of the assay. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated using a two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons tests (n.s., not significant; ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(E) Serum cross-neutralization against SARS-CoV-2 epidemic strains in ARCoV-immunized mice. A plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT) against the three SARS-CoV-2 epidemic strains was performed using mouse sera collected 28 days after initial immunization. Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons tests.

See also Figure S5.

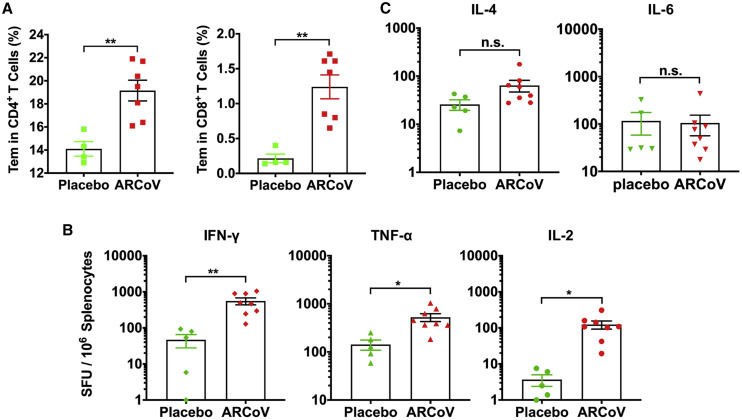

We further studied whether a SARS-CoV-2-specific T cell immune response was elicited by two doses of immunization of ARCoV mRNA-LNP in mice via i.m. administration. Flow cytometry results showed a significant increase in virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ effector memory T (Tem) cells in splenocytes from ARCoV-vaccinated mice in comparison with placebo LNPs (Figure 4 A) upon stimulation with peptide pools covering the SARS-CoV-2 RBD (Table S3). Furthermore, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assay showed that secretion of interferon γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin-2 (IL-2) in splenocytes from mRNA-LNP-immunized mice was significantly higher than in those that received the placebo vaccination (Figure 4B). There was no significant difference in IL-4 and IL-6 secretion between ARCoV-immunized animals and placebo-immunized ones (Figure 4C). Our results demonstrate that the mRNA-LNP vaccine successfully induces a Th1-biased, SARS-CoV-specific cellular immune response.

Figure 4.

SARS-CoV-2-Specific T Cell Immune Response in ARCoV-Vaccinated Mice

(A) SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific CD4+ and CD8+ Tem cells (CD44+CD62L−) in splenocytes were detected by flow cytometry.

(B and C) ELISPOT assay for IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, and IL-6 in splenocytes.

Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated using unpaired t test (n.s., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

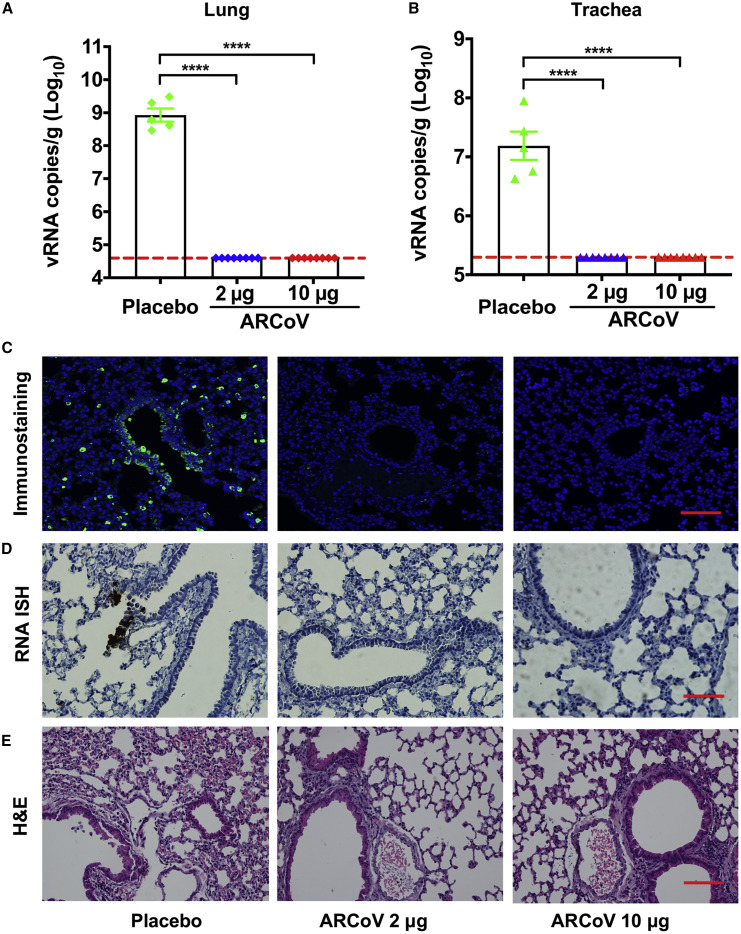

To further evaluate in vivo protection efficacy, we employed a newly developed SARS-CoV-2 mouse-adapted strain challenge model (Gu et al., 2020). Upon i.n. challenge with the mouse-adapted strain MASCp6, immunocompetent BALB/c mice showed robust viral replication in the lungs and trachea, resulting in moderate pneumonia and inflammatory responses. Deep sequencing revealed that MASCp6 contained a unique N501Y substitution at the S protein (Figure S1). To exclude a potential effect of the N501Y mutation on the antibody response, we also compared neutralizing antibody titers of mouse sera from ARCoV-immunized mice against MASCp6 and wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strain 131, respectively. As shown in Figure S6 , there was no significant difference in PRNT50 between the two strains. Then mice that received two doses of immunization of ARCoV mRNA-LNP at 2 or 10 μg were challenged i.n. with 6,000 plaque-forming units (PFUs) of SARS-CoV-2 MASCp6 40 days after initial vaccination (Figure 3A). On day 5 after challenge, mice were euthanized, the lungs and trachea were analyzed for viral RNA loads, and lung sections were subjected to immunostaining with in situ hybridization (ISH) and histopathological assays. Consistent with their high neutralizing antibody titers, all mice immunized with 2 or 10 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP showed full protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection, and no measurable viral RNA was detected in the lungs (Figure 5 A) and trachea (Figure 5B), whereas high levels of viral RNA were detected in the lungs and trachea (∼109 and 107 RNA copy equivalents per gram, respectively) of mice in the placebo group. An immunostaining assay showed abundant SARS-CoV-2 protein expression, mainly along the airway, in lung sections from mice receiving placebo LNP inoculation, whereas few positive cells were detected in lungs from ARCoV-vaccinated mice (Figure 5C). Similarly, an ISH assay by RNAScope also detected SARS-CoV-2-specific RNA in placebo mice but no viral RNA in lung sections from all ARCoV-vaccinated animals (Figure 5D). More importantly, mice vaccinated with empty LNPs developed typical lung lesions characterized by denatured epithelial tissues, thickened alveolar septa, and activated inflammatory cell infiltration, whereas no such pathological changes were seen in lung sections from all ARCoV-immunized animals (Figure 5E). These results demonstrate that two doses of ARCoV vaccination completely prevent SARS-CoV-2 replication in the lower respiratory tract and protect mice from lung lesions.

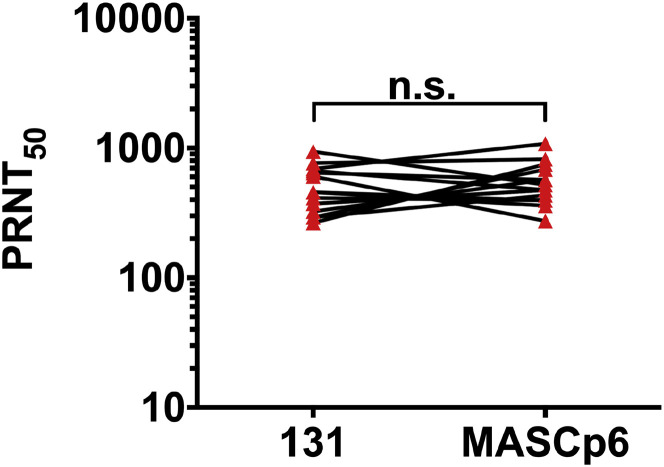

Figure S6.

Serum Neutralization Comparison between SARS-CoV-2 Clinical Isolate and the Mouse-Adapted Strain MASCp6, Related to Figure 5

Standard PRNT assay were performed with sera from ARCoV immunized mice (n = 15) using SARS-CoV-2 strains 131 and MASCp6, respectively. Data are analyzed by paired t test. (n.s., not significant).

Figure 5.

Protection of ARCoV against SARS-CoV-2 Challenge in Mice

Forty days after the initial immunization, mice were inoculated i.n. with the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 (MASCp6), and the indicated tissues were collected 5 days after challenge for detection of viral loads and lung pathology.

(A and B) Viral RNA loads in the lungs and trachea were determined by qRT-PCR. Data are shown as mean ± SEM (∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(C) Immunostaining of lung tissues with a SARS-CoV-2 S-specific mAb. Scale bar, 100 μm.

(D) ISH assay for SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Scale bar, 50 μm. Positive signals are shown in brown.

(E) H&E staining of lung pathology. Scale bar, 100 μm. Representative images from 4 or 5 mice are shown.

See also Figure S5.

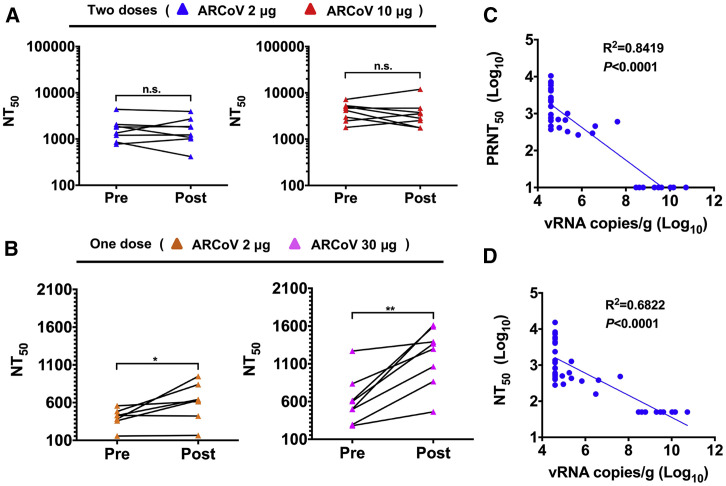

We also compared the serum neutralizing antibodie titers of ARCoV-vaccinated mice before and after SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Strikingly, all animals receiving 2 or 10 μg doses of ARCoV mRNA-LNP showed no significant increase in neutralizing titers after challenge with SARS-CoV-2 (Figure 6 A). The in vivo protection of a single immunization of ARCoV mRNA-LNP was also evaluated using the MASCp6 model. All mice vaccinated with 30 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP showed markedly reduced levels of viral RNAs in the lungs (>1,000-fold) and virtually no detectable viral RNA in the trachea (Figures S5C and S5D). Mice vaccinated with 2 μg of ARCoV showed partial protection; viral RNA levels in the trachea only had an approximately 10-fold reduction compared with mice immunized with placebo LNPs. These results were consistent with the level of neutralizing antibody titers (Figure S5). As expected, most animals that received a single immunization of 2 or 30 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNPs sustained an increase in NT50 after challenge (Figure 6B), indicating induction of an anamnestic immune response. We also evaluated whether antibody titer levels correlate with protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Viral RNA loads recovered from each individual mouse lung were compared with serum PRNT50 and NT50 titers from all mRNA-LNP-vaccinated mice, and the results showed an inverse correlation (R2 = 0.8419, p < 0.0001) between PRNT50 titers and the level of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in mouse lungs (Figure 6C). Similarly, NT50 titers were also inversely correlated with lung viral RNA loads (R2 = 0.6822, p < 0.0001) (Figure 6D). These data suggest that vaccine-elicited serum neutralizing antibody titers can be immune correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge.

Figure 6.

Immune Correlate of Protection against SARS-CoV-2 in ARCoV-Vaccinated Mice

(A and B) Paired sera were collected from animals receiving two doses (2 or 10 μg) or a single dose (2 or 30 μg) of vaccination before (Pre) and 5 days after (Post) SARS-CoV-2 challenge. The NT50 values were analyzed for differences using a paired t test (n.s., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01).

(C and D) Correlations of viral loads and protective efficacy by PRNT50 and NT50. Animals receiving a placebo (n = 10) and ARCoV (n = 31) vaccination were included in this analysis. The p values and R2 values reflect Spearman rank-correlation tests.

See also Figure S5.

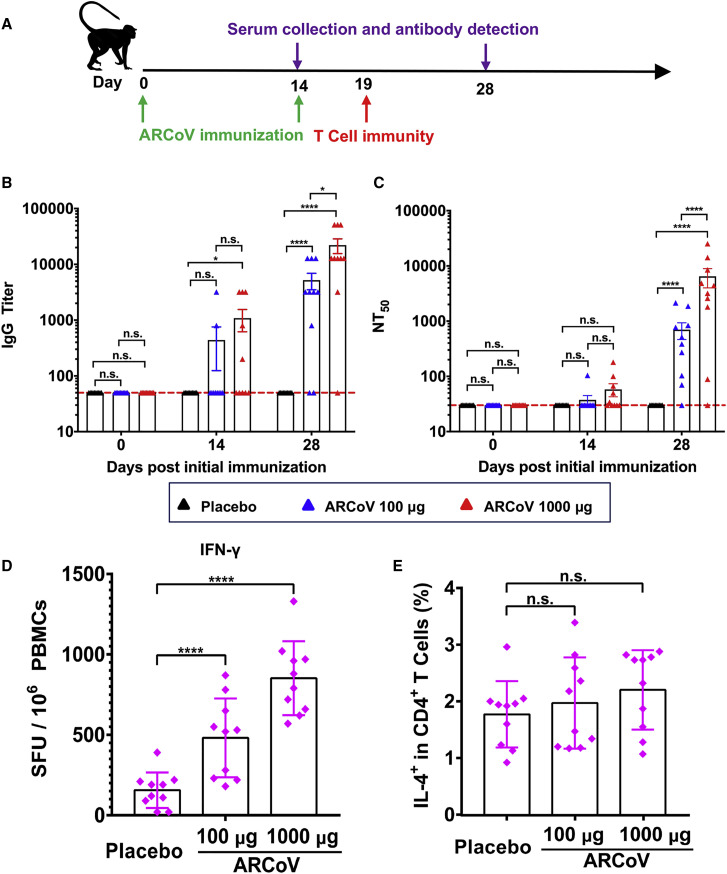

We next evaluated the immunogenicity of the ARCoV vaccine in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis), a non-human primate model susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection (Lu et al., 2020; Rockx et al., 2020). Two groups of macaques (n = 10/group) were immunized with 100 or 1,000 μg of ARCoV mRNA-LNP via i.m. administration and boosted with the same dose 14 days after initial immunization (Table S4). The same number of monkeys (n = 10) was vaccinated with PBS as a placebo (Figure 7 A). SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies were readily induced on day 14 after initial immunization, and the booster immunization resulted in a notable increase in IgG titers to ∼1/5,210 and ∼1/22,085 on day 28 after initial immunization (Figure 7B). Fifty percent of animals that received high-dose ARCoV immunization developed low-level neutralizing antibodies on day 14 after initial immunization, whereas the booster immunization resulted in a notable increase in NT50 to ∼1/699 and ∼1/6,482 in monkeys vaccinated with low- or high-dose ARCoV, respectively (Figure 7C). Additionally, there was no significant difference in serum neutralizing titers between male and female macaques (Figure S7 ). IFN-γ ELISPOT assays showed that SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific T cell responses were stimulated in peripheral blood monocytes (PBMCs) from monkeys vaccinated with a low or high dose of ARCoV on day 5 after booster immunization but not from animals receiving a placebo (Figure 7D); There was no significant difference in IL-4+/CD4+ cell response to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD between ARCoV- and placebo-treated animals (Figure 7E), suggesting induction of a Th1-biased cellular immune response by ARCoV immunization.

Figure 7.

Immunogenicity of ARCoV in Cynomolgus Macaques

Three- to six-year-old male or female cynomolgus macaques were immunized i.m. with 100 μg (n = 10) or 1,000 μg (n = 10) of ARCoV and boosted with the same dose at a 14-day interval. Serum was collected on days 0, 14, and 28 after initial immunization and subjected to antibody assays.

(A) Schematic diagram of ARCoV immunization, sample collection, and immunological assays.

(B and C) The IgG titers and NT50 values were determined by ELISA and SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus neutralization assay, respectively. Dotted lines indicate the limits of detection. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons tests (n.s., not significant, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

(D and E) Production of IFN-γ or IL-4 in PBMCs stimulated by the SARS-CoV-2 RBD was measured by ELISPOT assay or flow cytometry. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons tests (n.s., not significant, ∗∗∗∗, p < 0.0001).

See also Table S4.

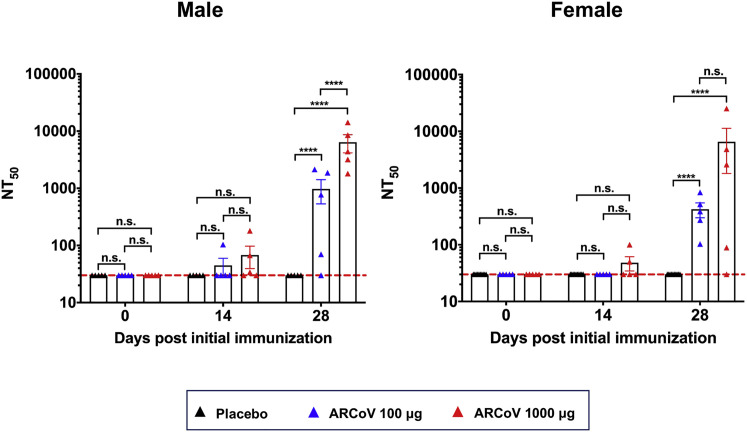

Figure S7.

Neutralizing Antibody Response in Male and Female Cynomolgus Monkeys, Related to Figure 7

Ten cynomolgus macaques were immunized intramuscularly with 100 μg or 1000 μg of ARCoV, respectively, and boosted with the same dose at a 14-day interval. The serum neutralizing antibody titers from male and female macaques were calculated respectively. Dotted lines indicate the limits of detection. Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparison tests. (n.s., not significant, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

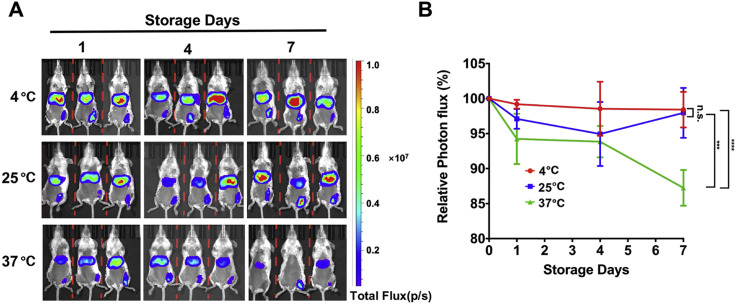

Finally, because cold chain transportation is not available in many COVID-19 epidemic areas, a vaccine that can be stored at room temperature is highly desirable. The thermal stability of the ARCoV mRNA-LNP vaccine was evaluated using the FLuc reporter mRNA-LNP formulation. After storage for 1, 4, and 7 days at different temperatures, the FLuc reporter mRNA-LNP was administered i.m. into BALB/c mice, and the mice were subjected to in vivo BLI imaging 6 h later. As shown in Figure S8 A, there was no reduction in FLuc expression between all groups, indicating that our mRNA-LNP formulation is stable at 4°C and 25°C for at least 7 days. Storage at 37°C for 7 days only resulted in an ∼13% reduction in relative photon flux (Figure S8B). These results indicate high thermostability of the ARCoV vaccine.

Figure S8.

Thermostability of mRNA-LNP Formulations under Different Temperatures, Related to Figure 2

(A) BLI of FLuc expression in mice. The FLuc encoding mRNA-LNPs were stored at 4°C, 25°C or 37°C for 1, 4, and 7 days before being dosed to BALB/c mice. IVIS imaging was performed 6 hours post inoculation.

(B) Photon flux was quantified from ROI analysis. The data are representative of at least three independent experiments, and error bars indicate the SEM. Significance was calculated using two-way ANOVA with multiple comparison tests. (n.s., not significant;∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001).

Discussion

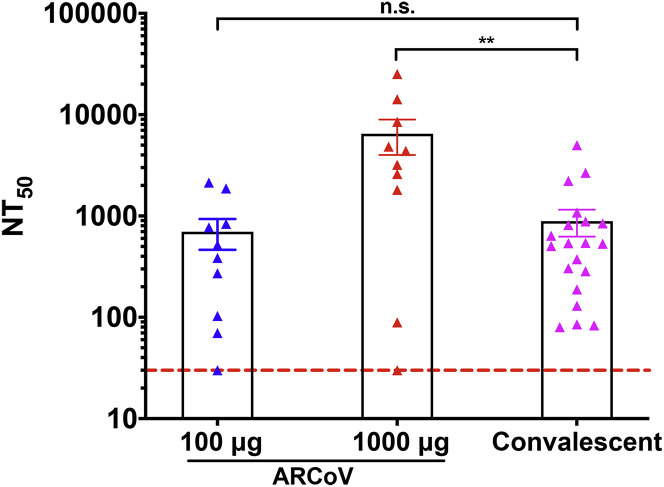

In the present study, we report the immunogenicity and efficacy of a novel COVID-19 mRNA vaccine candidate in various animal models. A single dose or two doses of immunization with ARCoV elicited robust antibody and T cell responses in mice and non-human primates against multiple epidemic SARS-CoV-2 strains. The NT50 in sera from non-human primates receiving low-dose (100 μg) ARCoV immunization was comparable with those from convalescent sera from 20 COVID-19 patients (Figure S9 ), whereas high-dose (1,000 μg) ARCoV immunization induced much higher titers of neutralizing antibodies compared with convalescent serum (Ni et al., 2020). It has been reported that two or three doses of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virus vaccine could induce neutralizing antibodies at levels of ∼1/50, which provides full protection against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus macaques (Gao et al., 2020). A recent report showed that two doses of immunization with a DNA vaccine candidate elicits mean neutralization titers between ∼1/70 and ∼1/170 in rhesus macaques (Yu et al., 2020). In the aforementioned studies, all animals exhibited anamnestic antibody responses following challenge, suggesting that vaccine protection was probably not sterilizing, which was consistent with relative lower neutralizing antibody titers. In our study, a single dose of ARCoV immunization induced an anamnestic antibody response, whereas animals receiving two doses of ARCoV immunization did not show enhancement of neutralizing antibody titers upon challenge, suggesting that sterilizing immunity may have been induced in mice (Figure 6A).

Figure S9.

Comparison of Neutralizing Antibody Titers in ARCoV-Immunized Cynomolgus Monkeys and Convalescent Sera from COVID-19 Patients, Related to Figure 6

The serum neutralizing antibody titers were calculated from cynomolgus macaques immunized with 100 μg (n = 10) and 1000 μg (n = 10) ARCoV and COVID-19 patients’ convalescent sera (n = 20), respectively. Dotted lines indicate the limits of detection. Significance was calculated using a one-way ANOVA with multiple comparison tests. (n.s., not significant; ∗∗p < 0.01).

Further challenge experiments with a SARS-CoV-2 mouse-adapted strain, MASCp6 (Gu et al., 2020), showed that two doses of immunization of ARCoV completely blocked viral replication in the lungs and trachea and prevented pulmonary pathology in mice (Figure 5). Although it still needs to be validated further in clinical settings, our results revealed that neutralizing antibody titer levels in mice correlate well with protection against SARS-CoV-2 challenge. Regression analysis revealed a cutoff value of ∼1:1,009 neutralizing antibody titers (PRNT50) as full protection from SARS-CoV-2 lung infection. To our knowledge, this is the first protection correlate identified in a mouse model. Considering the limited resource of non-human primates and strict requirement of biosafety facilities for SARS-CoV-2 challenge experiments, this protection correlate in a mouse model is a simple and useful benchmark for efficacy tests that will greatly facilitate and accelerate COVID-19 vaccine development. Because of biosafety facility limitations, at present we are not able to obtain protection efficacy data in non-human primates. However, based on the comparison of neutralizing antibody levels in macaques vaccinated with inactivated or DNA COVID-19 vaccine candidates (Gao et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020), protective immunity can be expected in most macaques immunized with two doses of ARCoV. ARCoV is highly immunogenic in male and female macaques (Figure S7). Of particular note is that, although 1 in 10 vaccinated macaques in each group failed to produce detectable (1:30) neutralizing antibodies, an IFN-γ ELISPOT assay showed virus-specific IFN-γ secretion in all vaccinated macaques (Table S4).

An ideal COVID-19 vaccine is supposed to avoid induction of non-neutralizing antibody and Th2-biased cellular immune responses because of safety concerns (Graham, 2020). Unlike the mRNA-1273 vaccine from Moderna (Corbett et al., 2020), our ARCoV vaccine chose the RBD as an antigen target. Compared with the full-length S protein, RBD antigen may induce fewer non-neutralizing antibodies, lowering the risk of potential ADE of SARS-CoV-2 infection; a similar phenomenon has been observed during other coronavirus infection experiments (Olsen et al., 1992). A recent in vitro study also suggests that antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 RBD at various concentrations did not induce ADE infection (Quinlan et al., 2020). S-specific IgG antibodies have been suggested to cause acute pulmonary injury in vaccine challenge animal models of SARS-CoV (Liu et al., 2019), although the exact S epitopes accounting for the lung pathology remain to be determined; use of the RBD may minimize this risk. Additionally, vaccine-associated enhanced respiratory disease has been linked to Th2-biased CD4+ T cell responses (Ruckwardt et al., 2019). As expected, our mRNA-based vaccine induced a Th1-prone T cell immune response to SARS-CoV-2 RBD in mice and macaques (Figures 4 and 7). Similar results have also been reported in DNA- and adenovirus-vectored COVID-19 vaccine candidates (van Doremalen et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020a). In our mouse challenge experiments, we did not observe enhanced viral replication or clinical disease in vaccinated animals, even those receiving a single dose of ARCoV vaccination.

We also characterized the in vitro and in vivo expression pattern of our mRNA-LNP formulation. Upon i.m. injection, robust protein expression was readily detected in the muscle tissue at the injection site, and the most predominant expression was seen in the liver (Figures 2A and 2B), which was similar to the results from other LNP formulations (Bahl et al., 2017; Pardi et al., 2015). Most importantly, a multiplex immune co-staining assay showed robust expression of SARS-CoV-2 RBD in multiple antigen-presenting cells, including monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells (DCs), in muscle and liver as well as lymph nodes from ARCoV-vaccinated mice (Figures 2D and 2E). A recent study has shown that a yellow fever mRNA vaccine delivered by LNP was mainly expressed at the injection site as well as in draining lymph nodes in cynomolgus macaques (Lindsay et al., 2019). Further biodistribution profiles of ARCoV in cynomolgus monkeys are being tested in a good laboratory practice (GLP) lab.

To date, limited results have been reported regarding the safety and stability of LNP-based mRNA vaccines (Jackson et al., 2020; Maruggi et al., 2019; Stitz et al., 2017). Our data from cynomolgus monkeys show that 100 μg of ARCoV is sufficient to induce high-level neutralizing antibodies and that 1,000 μg of ARCoV did not cause obvious adverse effects, highlighting the safety of our mRNA LNP formulation. Extrapolation of dose from animals to humans remains a huge challenge that requires careful consideration of safety and efficacy data. These preclinical data from mouse and non-human primate provide a critical reference for the starting dose of ARCoV in human trials. Last, accessibility and scalability of COVID-19 vaccines are major challenges to expediting delivery and massive immunization worldwide; therefore, a ready-to-use and thermostable vaccine is highly preferred. The final ARCoV mRNA-LNP vaccine is manufactured in a liquid formulation without the need of thawing or reconstitution before injection, and a single-dose vaccine is prepared in a prefilled syringe for quick self-administration. Stability test results showed that our formulation maintained in vivo delivery efficiency at 4°C and 25°C for at least 1 week (Figure S8); the long-term stability of the ARCoV vaccine is currently under evaluation. Additionally, ARCoV is administrated with the most commonly used i.m. vaccination route for human use. These unique features of ARCoV make it a promising COVID-19 vaccine candidate with universal availability and global accessibility.

In summary, we report a thermostable mRNA vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2 and provided first-line evidence of immunogenicity and efficacy in multiple animal models. Although two mRNA vaccine candidates from Moderna and BioNTech/Pfizer were tested in humans prior to our results, there is no report that an mRNA vaccine can protect animals from SARS-CoV-2 infection or the immune correlate of protection. During revision of our manuscript, immunogenicity and protection efficacy of mRNA-1273 in mice was also reported (Corbett et al., 2020). The robust protection observed in both studies highlights the power of the mRNA vaccine platform and paves the path for a successful COVID-19 vaccine in the near future. Our ARCoV mRNA vaccine was approved for phase I clinical trials (ChiCTR2000034112) on June 19, 2020.

Limitations

The challenge experiments in our study were based on a mouse-adapted strain of SARS-CoV-2; further challenge experiments with a wild-type SARS-CoV-2 strain in transgenic ACE2 mice or non-human primates will provide more data regarding protective efficacy. Another limitation of our study is that the duration of neutralizing antibodies induced by ARCoV has yet to be determined. Experience from other human coronaviruses has indicated the possibility of re-infection because of a waning antibody response (Callow et al., 1990; Wu et al., 2007). Future studies are needed to evaluate the long-term immune response in animal models and the effectiveness of ARCoV in humans. Additionally, long-term stability assays with a clinical-grade ARCoV vaccine are under investigation.

STAR★Methods

Key Resources Table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CD163 | Abcam | Cat#ab182422; RRID:AB_2753196 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CD11b | Abcam | Cat#ab133357; RRID:AB_2650514 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Glutamine Synthetase | Abcam | Cat#ab176562 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Liver Arginase (Arg1) | Abcam | Cat#ab233548 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Desmin | Abcam | Cat#ab32362; RRID:AB_731901 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-CD31 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#77699S; RRID:AB_2722705 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD3 (PE/Cyanine7) | BioLegend | Cat#100220; RRID:AB_1732057 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD4 (FITC) | BioLegend | Cat#100510; RRID:AB_312713 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD8 (APC) | BioLegend | Cat#100712; RRID:AB_312751 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD8 (FITC) | BioLegend | Cat#100706; RRID:AB_312745 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD44 (PE) | BioLegend | Cat#103023; RRID:AB_493686 |

| Rat monoclonal anti-CD62L (APC) | BD Biosciences | Cat#553152; RRID:AB_398533 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-SARS-CoV Spike | Sino Biological | Cat#40150-T52 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti SARS-CoV-2 Spike | Sino Biological | Cat#40150-R007 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-SARS-CoV Spike S1 subunit protein | Sino Biological | Cat#40150-RP01 |

| Chimeric monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV Spike | Sino Biological | Cat#40150-D001; RRID:AB_2827980 |

| Chimeric monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike mh001 | Sino Biological | N/A |

| Chimeric monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike mh219 | Sino Biological | N/A |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SARS-CoV Spike 2C5 | N/A | N/A |

| Goat polyclonal anti-rabbit IgG-Fc (HRP) | Sino Biological | Cat#SSA003; RRID:AB_2814815 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-mouse IgG (HRP) | ZSGB-BIO | Cat#ZB-2305; RRID:AB_2747415 |

| Virus Strains | ||

| BetaCoV/Beijing/IME-BJ01/2020 (131) | This paper | GWHACAX01000000 |

| BetaCoV/Beijing/IME-BJ05/2020 (V34) | This paper | GWHACBB01000000 |

| BetaCoV/Beijing/IME-BJ08/2020 (5N) | This paper | GWHAMKA01000000 |

| BetaCoV/Beijing/IME-BJ05-P6/2020 (MASCp6) | Gu et al., 2020 | GWHACFH01000000 |

| SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus | Nie et al., 2020 | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Biotin-ACE2 protein | Sino Cell Tech | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 RBD-His Recombinant Protein | Sino Biological | Cat#40592-V08B |

| Human ACE2 protein | Kactus Biosystems | Cat#ACE-HM401 |

| RBD peptide pools, see Table S3 | Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) | N/A |

| Absolute ethanol | Sinopharm | Cat#10009259 |

| Sodium Acetate | Thermo Scientific | Cat#AM9740 |

| Opti-MEM™ I Reduced Serum Medium | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#31985-070 |

| RPMI 1640 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#22400-089 |

| Penecillin Streptomycin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#15140-122 |

| HEPES | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#15630-080 |

| Abcracker retrieval/elution buffer | Histova Biotechnology | N/A |

| Lipofectamine™ 2000 Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#11668019 |

| Lipofectamine™ 3000 Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#2041107 |

| TurboFect Transfection Reagent | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#R0531 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#10099141C |

| Low-melting point agarose | Promega | Cat#V2111 |

| TMB substrate | Solarbio | Cat#PR1200 |

| Concanavalin A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C-2010 |

| Brefeldin A | MCE | Cat#20350-15-6 |

| Isoflurance anesthesia | RWD Life Science | N/A |

| Hind III restriction enzyme | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#FD0504 |

| EcoR I restriction enzyme | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#ER0271 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit | QIAGEN | Cat#74106 |

| One Step PrimeScript™ RT-PCR Kit | TaKaRa | Cat#RR064A |

| Vaccinia Capping System | Novoprotein | Cat#M062-YH01 |

| Mouse TNF-α ELISpot Kit | MabTech | Cat#3511-4APW |

| Mouse IFN-γ ELISpot Kit | MabTech | Cat#3321-4AST |

| Mouse IL-2 ELISpot Kit | MabTech | Cat#3441-4APW |

| Mouse IL-4 ELISpot Kit | MabTech | Cat#3311-4APW |

| Mouse IL-6 ELISpot Kit | MabTech | Cat#3361-4APW |

| Zombie NIR™ Fixable Viability Kit | BioLegend | Cat#423106 |

| Dendritic Cell Rapid Maturation Kit | Fcmacs Biotech | Cat#900015 |

| SARS-CoV-2 S-RBD IgG ELISA Kit | Beijing Wantai | N/A |

| NEON 7-color Allround Discovery Kit | Histova Biotechnology | N/A |

| Bright-GloTM Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat#0000413446 |

| RNAscope® 2.5 HD Reagent Kit-Brown | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat#322300 |

| RNAscope® Probe-V-nCoV2019-S | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat#848561 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| Monkey: Vero | ATCC | Cat#CCL-81 |

| Human: HeLa | ATCC | Cat#CCL-2 |

| Human: HEK293T | ATCC | Cat#CRL-11268 |

| Human: HEK293F | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

| Human: Huh7 | JCRB | Cat#0403 |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: BALB/c | Beijing Vital River | N/A |

| Mouse: ICR | Shanghai SLAC | N/A |

| Cynomolgus monkey | Guangzhou Xusheng | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCDNA3.1-sp-RBD-His | Beijing BioMed Gene Technology | N/A |

| ABOP-010 | GENEWIZ | N/A |

| ABOP-028 | GENEWIZ | N/A |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| GraphPad prism 8.0 | Graphpad | https://www.graphpad.com/ |

| Living Image 3.0. | PerkinElmer | https://www.perkinelmer.com/ |

| Zetasizer V7.13 | Malvern Panalytical | https://www.malvernpanalytical.com/en/ |

Resource Availability

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, qincf.@bmi.ac.cn (C.F.Q.)

Materials Availability

All unique/stable reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Material Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate any unique datasets or code.

Experimental Model and Subject Details

Ethics statement

All animal studies were performed in strict accordance with the guidelines set by the Chinese Regulations of Laboratory Animals and Laboratory Animal-Requirements of Environment and Housing Facilities. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Laboratory Animal Center, Academy of Military Medical Sciences (AMMS), China (Assurance Number: IACUC-DWZX-2020-001). Convalescent sera were collected from COVID-19 patients from the 5th Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital with written informed consent.

Cells and Viruses

African green monkey kidney cell Vero (ATCC, CCL-81), human cervical carcinoma cell HeLa (ATCC, CCL-2), human embryonic kidney cell HEK293T/F (ATCC, CRL-11268), and human hepatocarcinoma cell Huh7 (JCRB, 0403) were maintained in Dulbecco’s minimal essential medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and penicillin (100 U/ml)-streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Patient-derived SARS-CoV-2 isolates (listed in Table S2) were passaged in Vero cells and the virus stock was aliquoted and titrated to PFU/ml in Vero cells by plaque assay. The mouse adapted SARS-CoV-2 strain MASCp6 and the VSV-based SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus have been described previously (Gu et al., 2020; Nie et al., 2020). All experiments involving infectious SARS-CoV-2 were performed under Biosafety Level 3 facilities in AMMS.

Method Details

Sequence alignment of SARS-CoV-2 S protein

Amino acid sequence alignment of full S protein of SARS-CoV-2 isolates was performed using MAFFT (Katoh and Standley, 2013). Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank nos. MN908947.3) was used as the reference strain.

mRNA synthesis

The mRNA was produced in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase-mediated transcription from a linearized DNA template from plasmid ABOP-028 (GENEWIZ), which encodes codon-optimized RBD region of SARS-CoV-2 (Figure S1) and incorporates the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions and a poly-A tail. The FLuc-encoding mRNA (FLuc-mRNA) was prepared from plasmid ABOP-010 (GENWIZ) in the same procedure.

Lipid-nanoparticle encapsulation of the mRNA

Lipid-nanoparticle (LNP) formulations were prepared using a modified procedure of a method previously described for siRNA (Ickenstein and Garidel, 2019; Figure S3). Briefly, lipids were dissolved in ethanol containing an ionizable lipid, 1, 2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC), cholesterol and PEG-lipid (with molar ratios of 50:10:38.5:1.5). The lipid mixture was combined with 20 mM citrate buffer (pH4.0) containing mRNA at a ratio of 1:2 through a T-mixer. Formulations were then diafiltrated against 10 × volume of PBS (pH7.4) through a tangential-flow filtratio (TFF) membrane with 100 kD molecular weight cut-offs (Sartorius Stedim Biotech), and concentrated to desired concentrations, passed through a 0.22 μm filter, and stored at 2∼8°C until use. All formulations were tested for particle size, distribution, RNA concentration and encapsulation.

Electron microscopy of ARCoV mRNA-LNP

ARCoV sample (3 μl) was deposited on a holey carbon grid that was glow-discharged (Quantifoil R1.2/1.3) and vitrificated using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Fisher Scientific) instrument. Cryo-EM imaging was conducted on a Talos F200C Equipped with a Ceta 4k x 4k camera, operated at 200 kV accelerating voltage.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Size measurements were performed using dynamic light scattering (DLS) on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern). Samples were irradiated with red laser (λ = 632.8 nm) and scattered light were detected at a backscattering angle of 173°. Results were analyzed to obtain an autocorrelation function using the software (Zetasizer V7.13).

mRNA transfection

HeLa, HEK293T, Huh7 or Vero cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 200,000 cells/well. Eighteen hours later, the cells were transfected with RBD or control mRNA (2 μg/ml) using Lipofectamine 3000 Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Six hours later, the medium was replaced with Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The supernatant was collected at 48 hours after transfection, clarified by centrifugation at 1000 x g, and then mixed with 5 × SDS loading buffer (non-reducing). The samples were loaded for SDS-PAGE without heating. The secreted RBD protein was then detected by western blotting with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein (Sino Biological).

Recombinant RBD protein purification

A hexa-His tag was added to the C terminus of signal peptide-RBD to facilitate further purification processes. The optimized RBD gene was cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector (Beijing BioMed Gene Technology) with Hind III and EcoR I (Thermo Fisher Scientific) restriction sites, resulting in a pcDNA3.1-sp-RBD-His plasmid. 293T cells were seeded in 15 cm dishes at 5,000,000 cells/dish. Eighteen hours later, the cells were transfected with pcDNA3.1-sp-RBD-His (1 μg/ml) using TurboFect Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Six hours later, the medium was removed and cells were washed with PBS for 3 times, followed by addition of Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium. The supernatant was collected per 24 hours for 4 days. The collected supernatant was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 3 minutes before filtration using 0.45 μm Membrane Filter (Millipore), and purified using NI-NTA agarose beads (QIAGEN). The purified protein was concentrated using Pierce Protein Concentrator PES, 3K MWCO (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

RBD-ACE2 binding assay

The real-time RBD-ACE2 binding assay was performed by biolayer interferometry using ForteBio Octet RED96e. Briefly, Streptavidin (SA) Biosensor from ForteBio was used to capture 10 μg/ml biotin-ACE2 (Sino Cell) onto the surface of the SA biosensor. After reaching base line, sensors were subjected to the association step containing 75.6, 30.2, 12.1, 4.84 or 1.94 nM purified RBD-His proteins for 900 s and then dissociated for 100 s. The KD, Kon and Kdis were calculated by Data Analysis Octet.

Competitive inhibition assay

Competitive inhibition assay was performed using SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus as described previously (Nie et al., 2020). Briefly, Huh7 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 50,000 cells/well for 20 hours. The cells were incubated with 50 μg/ml of BSA, RBD (purified RBD-His protein), or recombinant RBD-His (rRBD, Sino Biological) for 1 hour at 37°C, followed by treatment with 650 TCID50/well of the pseudovirus for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were washed with DMEM medium for 3 times and cultured at 37°C for 22 hours. Luciferase substrate (PerkinElmer) was then added to plates followed by incubation in darkness at room temperature for 2 minutes. The lysate was transferred to white solid 96-well plates for the detection of luminescence using GloMax® 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega).

Recombinant RBD expression in vitro

HEK293F cells were seeded in a 24-well cell culture plate at 100,000 cells/well in opti-MEM™ I Reduced Serum Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Eighteen hours later, 1 mg of RBD-encoding mRNA and equal amount of LNP were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine™ 2000 Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The cells were further cultured with 5% CO2 at 37°C for 15 hours. Culture media were collected and analyzed by ELISA as described below.

RBD expression in vivo

Female ICR mice (4-6-week-old) were purchased from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Twenty mice were randomly divided into two groups (n = 10/group). mRNA-LNP or LNP was intravenously administrated at 1 mg/kg into animals. The orbital blood was collected at 6 hours after administration, centrifuged at 5,000 g at 4°C for 10 minutes. Sera were collected and stored at −80°C for further test. RBD expression level was determined by ELISA as described below.

ELISA for evaluation of RBD expression in vitro and in vivo

Evaluation of RBD expression in vitro and in vivo was performed by ELISA. Briefly, 96-well microtiter plates were coated with 5 μg/ml of human ACE2 (Kactus Biosystems) overnight at 4°C. The coated plates were washed once with PBS and blocked with 5% BSA at 4°C for 12 hours. Plates were then washed twice with PBS and incubated with serial dilutions of cell culture media or mouse sera at room temperature for 1 hour, prior to three further washes and subsequent 1 hour incubation with SARS-CoV-2 S rabbit mAb (Sino Biological) as primary antibody at room temperature. After three washes with PBS, plates were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG-Fc antibody as secondary antibody (Sino Biological), followed by incubation with TMB substrate (Solarbio). The absorbance at 450/620 nm was measured and accurate quantification were conducted using SpectraMax iD3 (Molecular Devices).

BLI for detection of in vivo distribution of FLuc mRNA-LNPs

For detection of in vivo distribution of FLuc mRNA-LNPs, female BALB/c mice aged 6-8 weeks (n = 18) were inoculated with 10 μg of the FLuc mRNA-LNP via intramuscular (i.m.), subcutaneous (s.c.) or intranasal (i.n.) routes, respectively. At indicated times post inoculation, animals were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with luciferase substrate (Promega). After reaction for 3 minutes, fluorescence signals were collected by IVIS Spectrum instrument (PerkinElmer) for 60 s. For in vitro imaging, female BALB/c mice of 6-8 weeks old (n = 2) were intramuscularly inoculated with 10 μg FLuc mRNA-LNP and LNP, respectively. Six hours later, animals were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with luciferase substrate (Promega) followed by reaction for 3 minutes. Tissues including brain, heart, liver, spleen, lung, kidney and muscle were collected immediately, and fluorescence signals of each tissue were collected by IVIS imager for 60 s. The fluorescence signals in regions of interest (ROIs) were quantified using Living Image 3.0.

BLI for evalution of thermostability of the FLuc mRNA-LNP

FLuc mRNA-LNP was incubated at 4, 25 or 37°C for 1, 4, and 7 days. Female BALB/c mice aged 6-8 weeks (n = 27) were inoculated with 10 μg of the incubated FLuc mRNA-LNP via intramuscular (i.m.) route. Six hours after administrations, animals were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with luciferase substrate (Promega), followed by reaction for 3 minutes. Fluorescence signals were collected by IVIS Spectrum instrument (PerkinElmer) for 60 s, and the fluorescence signals in regions of interest (ROIs) were quantified using Living Image 3.0.

Multiplex immunofluorescent assay

The expression of RBD in tissues from ARCoV or placebo vaccinated mice was detected by multiplex immunofluorescent assay. Mouse lung or muscle paraffin sections (4 μM) were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in a series of graded alcohols. Antigen retrievals were performed in citrate buffer (pH6.0) with a microwave (Sharp) for 20 minutes at 95°C followed by a 20 minutes cool down at room temperature. Multiplex fluorescence labeling was performed using TSA-dendron-fluorophores (NEON 7-color Allround Discovery Kit for FFPE (Histova Biotechnology). Briefly, endogenous peroxidase was quenched in 3% H2O2 for 20 minutes, followed by blocking reagent for 30 minutes at room temperature. Primary antibody was incubated for 2 to 4 hours in a humidified chamber at 37°C, followed by detection using the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and TSA-dendron-fluorophores. Afterward, the primary and secondary antibodies were thoroughly eliminated by heating the slides in retrieval/elution buffer (Abcracker®, Histova Biotechnology) for 10 s at 95°C using microwave. In a serial fashion, each antigen was labeled by distinct fluorophores. Multiplex antibody panels applied in this study are: SARS-CoV S1 subunit protein (1:1000, Sino Biological); Glutamine Synthetase (1:2000, Abcam), Liver Arginase (Arg1) (1:800, Abcam), CD31 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology), CD163 (1:500, Abcam), CD11b (1:1000, Abcam), Desmin (1:500, Abcam). After all the antibodies were detected sequentially, the slices were imaged using the confocal laser scanning microscopy platform Zeiss LSM880.

Mouse vaccination and challenge experiments

For single-dose immunization, groups of 6-8-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized intramuscularly with ARCoV mRNA-LNP (2 μg, n = 7; 30 μg, n = 8), or Placebo (n = 5) in 50 μL using a 3/10cc 29½G insulin syringe (BD Biosciences). Serum was collected at 1 day before immunization and 14 and 28 days post immunization for detection of SARS-CoV-2 -specific IgG and neutralizing antibody responses as described below. For two-dose immunization, groups of 6-8-week-old female BALB/c mice were immunized intramuscularly with ARCoV mRNA-LNP (2 μg, n = 8; 10 μg, n = 5) in 50 μL using a 3/10cc 29½G insulin syringe (BD Biosciences), and boosted with equal dose of ARCoV mRNA-LNP on day 14 post initial immunization. Sera were collected at 1 day before initial immunization and days 7, 14, 21 and 28 after initial immunization for detection of SARS-CoV-2 -specific IgG and neutralizing antibody responses as described below. Spleen tissues were collected at day 28 post initial immunization for evaluation of cellular immune responses by ELISPOT and flow cytometry as described below.

The SARS-CoV-2 challenge model based on the mouse adapted strain MASCp6 has been characterized in detail (Gu et al., 2020). BALB/c mice immunized with ARCoV were challenged intranasaly with MASCp6 (6,000 PFU/mouse) at the indicated times. On day 5 post challenge, all animals were sacrificed, and the lung and trachea tissues as well as sera were collected for subsequent antibody detection, viral RNA level determination, histopathology assay, immunofluorescence staining and RNA ISH assay as described below.

Cynomolgus monkey studies

A total of 30 adult cynomolgus monkeys (weighing 2.3-4.6 kg) were purchased from Guangzhou Xusheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd (See details in Table S4). Animals with similar age and weight were allocated to each group (male/female ratio = 1:1). All animals were immunized intramuscularly with 100 μg (n = 10) or 1000 μg (n = 10) of ARCoV mRNA-LNP, and boosted with the same dose of ARCoV mRNA-LNP on 14 days post initial immunization. Empty LNPs were set as placebo control (n = 10). Clinical signs were recorded during a 14-day observation period. Blood was collected before immunization and 14 and 28 days after initial immunization to detect SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG and neutralizing antibodies as described below. PBMCs were collected on day 19 after initial immunization for antigen specific T cell detection. IFN-γ and IL-4 levels were determined by ELISPOT and flow cytometry as previously described (Erhart et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Ruiz et al., 2018)

Sera antibody titer evaluation

Animal immune serum samples were heated at 56°C for 30 minutes before use. SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG antibody titers were determined by ELISA. Neutralizing antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 were determined by a pseudovirus-based neutralization assay and a standard plaque reduction neutralization test (PRNT), respectively.

-

(a)

ELISA for SARS-CoV-2 specific IgG antibody. SARS-CoV-2 RBD specific IgG titers were determined by a commercial ELISA kit (Beijing Wantai Biological) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, serial 2-fold dilutions of inactivated serum, starting at 1:50 (monkey) or 1:100 (mouse), were added to blocked 96-well plates (50 μl/well) coated with recombinant SARS-CoV-2 RBD antigen and plates were incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. After three washes with wash buffer, plates were added with Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:5,000, ZSGB-BIO) or HRP-conjugated RBD and incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. Plates were then washed five times with wash buffer and added with chromogen solution followed by 15 minutes of incubation at 37°C. The absorbance (450/630 nm) was read using a microplate reader (Bio Tek). The endpoint titers were defined according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

-

(b)

Pseudovirus-based neutralization assay. The SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus based neutralization assay was performed as described previously (Nie et al., 2020). In brief, Huh7 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (200,000 cells/well) and incubated for approximately 24 hours until 90%–100% confluent. Serial 3-fold diluted serum, starting at 1:50, were incubated with 650 TCID50 of the pseudovirus for 1 hour at 37°C. DMEM was used as negative control. The supernatant was then removed and luciferase substrate was added to each well followed by incubation for 2 minutes in darkness at room temperature. Luciferase activity was then measured using GloMax® 96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega). The 50% neutralization titer (NT50) was defined as the serum dilution at which the relative light units (RLUs) were reduced by 50% compared with the virus control wells. The NT50 was determined by non-linear regression, i.e., log (inhibitor) v.s. normalized response (Variable slope), using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software).

-

(c)

PRNT assay. PRNT was performed as described previously (Li et al., 2018). Briefly, Vero cells were seeded in 24-well plates (200,000 cells/well) and incubated for approximately 16 hours until 90%–100% confluent. Serial 3-fold dilutions, starting at 1:30, of serum were prepared in DMEM containing 2% FBS. The diluted sera was then mixed with titerated virus in a 1:1 (vol/vol) ratio to generate a mixture containing ∼200 PFU/ml of viruses, followed by incubation at 37°C for 1 hour. The virus/serum mixtures were added to wells of 24-well plates of Vero cell monolayers in duplicate (250 μl/well). The plates were then incubated at 37°C for 1 hour with intermittent rocking of the plates every 20 minutes. The mixtures were removed and cells were overlaid with 1% low-melting point agarose (Promega) in DMEM containing 2% FBS. After further incubation at 37°C for 2 days, the cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde and stained with 0.2% crystal violet. Plaque numbers were recorded after rinsing the plates with deionized water. The 50% neutralization titer (PRNT50) was calculated by the method of Spearman-Karber (Hamilton et al., 1977).

Enzyme linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay

Cellular immune responses in the vaccinated mice were assessed using IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, or IL-6 precoated ELISPOT kits (MabTech), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the plates were blocked using RPMI 1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% FBS and incubated for 30 minutes. Immunized mouse splenocytes were then plated at 300,000 cells/well, with peptide pool for SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein (2 μg/ml of each peptide, see Table S3), Concanavalin A (ConA, Sigma) as positive control or RPMI 1640 media as negative control. After incubation at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 36 hours, plates were washed with wash buffer and biotinylated anti-mouse IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4 or IL-6 antibody was added to each well followed by incubation for 2 hours at room temperature. Following the addition of AEC substrate solution, the air-dried plates were read using the automated ELISPOT reader AID ELISPOT (AID). The numbers of spot-forming cells (SFC) per 1,000,000 cells were calculated.

Flow cytometry analyses for mouse splenocytes

T cell proliferation in immunized mice were evaluated using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Briefly, a total of 1,000,000 mouse splenocytes were stimulated with SARS-CoV-2 RBD peptide pool (2 μg/ml of each peptide, see Table S3) for 2 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2. Brefeldin A (1 μg/ml, MCE) was then added into splenocytes and incubated for 4 hours. Following two washes with PBS, splenocytes were permeabilized and stained with fluorescently conjugated antibodies to CD3 (PE/Cyanine7) (BioLegend), CD4 (FITC) (BioLegend), CD8 (APC/FITC) (BioLegend), CD44 (PE) (BioLegend) or CD62L (APC) (BD Biosciences). Dead cells were stained with Zombie UV3 fixable viability Kit (BioLegend). Data are analyzed with FlowJo software.

Quantification of viral RNA in challenged mouse tissues by RT-qPCR

Viral RNA in lung and trachea tissues from challenged mice was detected by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR). Briefly, tissue samples were weighed, homogenized with stainless steel beads in a Tissuelyser-24 (Shanghai jingxin Industrial Development CO., LTD) in 1 mL of DMEM. Viral RNA in tissues was then extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. SARS-CoV-2 RNA quantification was performed by RT-qPCR targeting the S gene of SARS-CoV-2 using One Step PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (Takara) with the following SARS-CoV-2 specific primers and probes: CoV-F3 (5’-TCCTGGTGATTCTTCTTCAGGT-3′), CoV-R3 (5’-TCTGAGAGAGGGTCAAGTGC-3′), and CoV-P3 (5’-FAM-AGCTGCAGCACCAGCTGTCCA-BHQ1-3′). Viral RNA load was expressed on a log10 scale as viral RNA equivalents per g after comparison with a standard curve produced using serial ten-fold dilutions of SARS-CoV-2 RNA.

Histopathology assay

For histopathology, lung tissues from mice were fixed in 4% neutral-buffered formaldehyde for 48 hours, embedded in paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Images were captured using Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a DP72 camera. Original magnification was 20 ×.

Immunofluorescence staining of lung tissues

For immunostaining, paraffin tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated through successive bathes of ethanol/water and incubated in 3% H2O2 at room temperature. The sections were then put in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer for 1 hour at 96°C for antigen retrieval and blocked with BSA at saturation for 20 minutes. Primary antibody against SARS-CoV S protein (Sino Biological) was incubated for 2 hours in a humidified chamber at 37°C, followed by detection using the TSA-dendronfluorophores. Original magnification was 20 ×.

RNA ISH assay

SARS-CoV-2 genome RNA ISH assay was performed with RNAscope® 2.5 HD Reagent Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Briefly, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue sections of 5 μm were deparaffinized by incubation for 60 minutes at 60°C. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched with hydrogen peroxide for 10 min at room temperature. Slides were then boiled for 15 minutes in RNAscope Target Retrieval Reagents and incubated for 30 minutes in RNAscope Protease Plus before probe hybridization. Tissues were counterstained with Gill’s hematoxylin and visualized with standard bright-field microscopy. Original magnification was 40 ×.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 software. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size, unless indicated. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment unless indicated (RT-qPCR). Unless specified, data are presented as mean ± SEM in all experiments. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) or t test was used to determine statistical significance among different groups (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; n.s., not significant).

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Chunyun Sun, Jing Ma, and Qiang Gao for critical materials and helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2020YFC0842200, 2020YFA0707801, and 2016YFD0500304) and a special grant from AMS (JK2020NC002). C.-F.Q. was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (81925025), the Innovative Research Group (81621005) from the NSFC, and the Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (2019-I2M-5-049) from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Author Contributions

C.-F.Q., Y.-Q.D., and B.Y. conceived the project. C.-F.Q. designed and supervised the study and wrote the paper. N.-N.Z., X.-F.L., Y.-Q.D., H.Z., Y.-J.H., and G.Y. performed the majority of the experiments and analyzed the data. C.Z., P.G., R.-R.Z., S.-L.Z., Q.C., Q.H., T.-S.C., H.-Y.Q., Y.G., Y.J., S.-H.S., H.F., H.-Y.Y., X.-Y.H., Q.Y., X.Z., Z.-Y.Z., J.-H.N., D.Z., D.Z., W.-J.H., Y.-C.W., and X.Y. contributed specific experiments and data analysis. All authors read and approved the contents of the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

C.-F.Q. and B.Y. are co-inventors on pending patent applications related to the ARCoV mRNA vaccine. B.Y., P.G., Y.J., H.-Y.Y., X.Z., X.-L.X., and Z.-Y.Z. are employees of Suzhou Abogen Biosciences.

Published: July 23, 2020

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.07.024.

Supplemental Information

References

- Alameh M.G., Weissman D., Pardi N. Messenger RNA-Based Vaccines Against Infectious Diseases. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/82_2020_202. Published online April 17, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amanat F., Krammer F. SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines: Status Report. Immunity. 2020;52:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahl K., Senn J.J., Yuzhakov O., Bulychev A., Brito L.A., Hassett K.J., Laska M.E., Smith M., Almarsson Ö., Thompson J. Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Mol. Ther. 2017;25:1316–1327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra-Flores M., Cardozo T. SARS-CoV-2 viral spike G614 mutation exhibits higher case fatality rate. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2020:e13525. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.13525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callow K.A., Parry H.F., Sergeant M., Tyrrell D.A. The time course of the immune response to experimental coronavirus infection of man. Epidemiol. Infect. 1990;105:435–446. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800048019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett K.S., Edwards D., Leist S.R., Abiona O.M., Boyoglu-Barnum S., Gillespie R.A., Himansu S., Schafer A., Ziwawo C.T., DiPiazza A.T. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccine Development Enabled by Prototype Pathogen Preparedness. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.11.145920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erhart F., Buchroithner J., Reitermaier R., Fischhuber K., Klingenbrunner S., Sloma I., Hibsh D., Kozol R., Efroni S., Ricken G. Immunological analysis of phase II glioblastoma dendritic cell vaccine (Audencel) trial: immune system characteristics influence outcome and Audencel up-regulates Th1-related immunovariables. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2018;6:135. doi: 10.1186/s40478-018-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q., Bao L., Mao H., Wang L., Xu K., Yang M., Li Y., Zhu L., Wang N., Lv Z. Development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369:77–81. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham B.S. Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development. Science. 2020;368:945–946. doi: 10.1126/science.abb8923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H., Chen Q., Yang G., He L., Fan H., Deng Y.-Q., Wang Y., Teng Y., Zhao Z., Cui Y. Rapid adaptation of SARS-CoV-2 in BALB/c mice: Novel mouse model for vaccine efficacy. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.02.073411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M.A., Russo R.C., Thurston R.V. Trimmed Spearman-Karber method for estimating median lethal concentrations in toxicity bioassays. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1977;11:714–719. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Kruger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickenstein L.M., Garidel P. Lipid-based nanoparticle formulations for small molecules and RNA drugs. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2019;16:1205–1226. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2019.1669558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson N.A.C., Kester K.E., Casimiro D., Gurunathan S., DeRosa F. The promise of mRNA vaccines: a biotech and industrial perspective. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:11. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-0159-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S. Don’t rush to deploy COVID-19 vaccines and drugs without sufficient safety guarantees. Nature. 2020;579:321. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00751-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K., Standley D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korber B., Fischer W.M., Gnanakaran S., Yoon H., Theiler J., Abfalterer W., Foley B., Giorgi E.E., Bhattacharya T., Parker M.D. Spike mutation pipeline reveals the emergence of a more transmissible form of SARS-CoV-2. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.29.069054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lan J., Ge J., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou H., Fan S., Zhang Q., Shi X., Wang Q., Zhang L., Wang X. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215–220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.F., Dong H.L., Wang H.J., Huang X.Y., Qiu Y.F., Ji X., Ye Q., Li C., Liu Y., Deng Y.Q. Development of a chimeric Zika vaccine using a licensed live-attenuated flavivirus vaccine as backbone. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:673. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02975-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay K.E., Bhosle S.M., Zurla C., Beyersdorf J., Rogers K.A., Vanover D., Xiao P., Araínga M., Shirreff L.M., Pitard B. Visualization of early events in mRNA vaccine delivery in non-human primates via PET-CT and near-infrared imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:371–380. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Wei Q., Lin Q., Fang J., Wang H., Kwok H., Tang H., Nishiura K., Peng J., Tan Z. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.123158. e123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S., Zhao Y., Yu W., Yang Y., Gao J., Wang J., Kuang D., Yang M., Yang J., Ma C. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 infections among 3 species of non-human primates. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.08.031807. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maruggi G., Zhang C., Li J., Ulmer J.B., Yu D. mRNA as a Transformative Technology for Vaccine Development to Control Infectious Diseases. Mol. Ther. 2019;27:757–772. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]