Abstract

Leaf growth and photosynthetic characteristics of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas var. Biru Putih) grown under different light quantities were studied in a tropical greenhouse. The stem cuttings of I. batataswith adventitious roots were grown hydroponically under (1) only natural sunlight (SL); (2) SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s–1 (SL + L-LED); and (3) SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s–1 (SL + H-LED). One week after emergence, all leaves had similar area and water content. However, leaf fresh weight and dry weight were significantly higher in plants grown under SL+L-LED and SL + H-LED than under SL due to their thicker leaves reflected by the lower specific leaf area. Plants grown under SL had significantly lower concentrations of total chlorophyll (Chl) and total carotenoids (Car) but higher Chl a/b ratio than under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED. However, all plants had similar Chl/Car ratios. Although midday Fv/Fm ratio was the lowest in leaves grown under SL+ H-LED followed by SL + L-LED and SL, predawn Fv/Fm ratios of all leaves were higher than 0.8. Increasing growth irradiance with supplemental LED resulted in higher electron transport rate and photochemical quenching but lower non-photochemical quenching compared to those of plants grown under SL. Measured under their respective growth irradiance in the greenhouse, attached leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL+H-LED had significantly higher photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate and stomatal conductance than under SL. However, measuring the detached leaves at 25 °C in the laboratory, there were no significant differences in PS II and Cyt b6f concentrations although light- and CO2-statured photosynthetic O2 evolution rates were slightly higher in leaves grown under SL+ H-LED than under SL. Impacts of supplemental LED on leaf growth and photosynthetic characteristics were discussed.

Abbreviations: A, Photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate; Car, carotenoids; Chl, Chlorophyll; Ci, Internal CO2 concentration; Cyt b6f, Cytochrome b6f complex; DW, Dry weight; ETR, Electron transport rate; FW, Fresh weight; gs, Stomatal conductance; LED, Light emitting diode; NPQ, Non-photochemical quenching; Pmax, Photosynthetic capacity PN Net photosynthetic O2 evolution rate; PPFD, Photosynthetic photon flux density; qP, Photochemical quenching; RuBP, ribulose-15-bisphosphate; Rubisco, ribulose 1.5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase; SL, natural sunlight; SL+L-LED, natural sunlight with supplemental LED lighting at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s–1; SL + H-LED, natural sunlight with supplemental LED lighting at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s–1; SLA, specific leaf area; Tr, Transpiration

Keywords: LED lighting, Leaf growth, Photosynthetic performance, Sweet potato leaves, Tropical greenhouse

1. Introduction

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) is widely grown in developing countries due to its low production cost and its high adaptability (Lin et al., 2007; Mekonen et al., 2015). Most people grow sweet potato as food and mainly consume their modified root tubers (Yoshimoto et al., 2002). Although the leaves of sweet potato have been neglected, they are consumed as fresh vegetables in tropical areas in Southeast Asia (Nwinyi, 1992) because both leaf blades and petioles are rich in protein, dietary fiber, vitamins, antioxidants, essential fatty acids and minerals (Ishida et al., 2000; Johnson and Pace, 2010). Several studies have demonstrated that sweet potato leaves inhibit mutagenicity, diabetes, leukemia and viruses and the growth of colon and stomach cancer cells (Yoshimoto et al., 2002; Kurata et al., 2007; Ludivik et al., 2008).

Due to limited land in Singapore, local farming currently accounts for only 10 per cent of the leafy vegetables consumed. The maintenance of food security, especially the supply of vegetable is an increasing challenge for Singapore where natural resources are limited. Furthermore, the disconnect between supply and demand is the result of the global food supply chains being disrupted in unprecedented ways due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Back to March 2019, the Environment and Water Resources Minister, Singapore announced the ambitious “30 by 30” goal to produce 30 per cent of Singapore's nutritional needs locally by 2030 (Ai-Lien, 2019). Sweet potato leaves are considered an indigenous and tropical leafy vegetable, which could play an important role in alleviating the shortage of leafy vegetables as they grow quickly in the tropics under warm temperature and humid conditions (An et al., 2003). They have much higher annual yield than that of other green vegetables and could be harvested several times a year. Sweet potato are mainly grown over a broad range of environment. In Singapore sweet potato leaves are commonly cultured in outdoor soil farms. It was reported that high light intensity enhanced growth of sweet potato plants and thus, shade conditions should be avoided (Oswald et al., 1994). The sweet potato plant is also considered to be a drought tolerant crop (Ghuman and Lal, 1983). However, drought is a major environmental constraint for sweet potato production in the tropical area as its growth and development are significantly influenced by soil moisture (Yooyongwecha et al., 2013).

Soilless cultures such as hydroponics and aeroponics are increasingly adopted as major technological components in the modern greenhouses to replace community gardens and traditional outdoor soil farms in Singapore (He, 2015). Today, in Singapore, all kinds of leafy vegetables are grown all year round in the greenhouse using soilless culture systems with adequate water and nutrient supplies, which is not affected by drought conditions. Apart from water, light intensity critically affects plant growth. In the past two decades, Singapore has been frequently experiencing increasingly unpredictable cloudy and hazy weather (Nobre et al., 2016), resulting in lowered light intensity which reduced crop productivity (Jones, 2006). We have previously reported that in Singapore, when lettuce (He et al., 2011) and Brassica alboglabra (Chinese broccoli) plants (He et al., 2019b) were grown under low light during the haze episodes in the greenhouse, lower photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance and productivity were measured. To circumvent the problem of insufficient sunlight, in another study with lettuce plants, light emitting diode (LED) lighting was supplemented to low sunlight intensity in the greenhouse (Choong et al., 2018; He et al., 2019a). Leaf expansion rate was faster in both heat resistant and heat sensitive recombinant inbred lines (RILs) of lettuce grown under natural sunlight with supplemental LED. However, impacts of supplementary LED lighting on shoot and root productivity and photosynthetic performance such as photosynthetic light use efficiency and maximal oxygen evolution rate seemed to be genotype-dependent due to their different sensitivities to heat (Choong et al., 2018). In the study with B. alboglabra (Chinese broccoli), we have found that plants grown under shade with supplemental LED lighting improved photosynthetic CO2 assimilation, stomatal conductance and productivity (He et al., 2019). As mentioned earlier, sweet potato leaves are tropical leafy vegetables and have fast growth rates in the tropics under warm and humid conditions (An et al., 2003). The nutrient-rich leaf blade and petiole make it as one of the suitable vegetable crops to achieve the Singapore’s goal to produce 30 per cent of nutritional needs locally by 2030. However, little is known about its photosynthetic characteristics when grown under different light intensities using soilless culture such as hydroponics. We hypothesize that plant growth should increase with increasing of growth irradiance, with leaf traits adjustment that enhance light capture and carbon fixation in the tropical greenhouse. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the effects of two different supplementary LED lightings with photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) of 150 and 300 μmol m−2 s–1 respectively on the leaf growth of sweet potato leaves, I. batatas (var. Biru Putih) in the tropical greenhouse. Impacts of supplementary LED quantity on photosynthetic light use efficiency measured by chlorophyll fluorescence, the functions of PS II and Cyt b6f, and photosynthetic gas exchanges were also studied.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials and experimental design

Sweet potato leaves, I. batatas (var. Biru Putih), were purchased from one of the local farms (KOK FAH Technology Farm Pte Ltd). Apical stems were cut into 15 cm pieces. Roots were induced from cuttings grown hydroponically under modified half strength Netherlands Standard Composition nutrient solution (details are given below) for 1 week. After root induction, the stem cuttings with adventitious roots were grown hydroponically in greenhouse under three different quantities of lights: (1) only natural sunlight (SL) with average maximum PPFD of 800 μmol m−2 s–1; (2) SL with supplemental LED lighting at a PPFD of 150 μmol m-2 s-1 (SL + L-LED); and (3) SL with supplemental LED lighting at a PPFD of 300 μmol m-2 s-1 (SL + H-LED). The photoperiod of supplemental LED lighting (Dissis LED Lighting Technology, Singapore) was 12-h (from 0700 h to 1900 h) provided by a combination of red- (633 nm and 656 nm) and blue-LED (463.5 nm) lightings in the ratio of 9:1. All the light intensities were measured by holding PAR quantum sensor with a reading unit (SKP 215 and 200, Skye Instruments Ltd, Llandrindod Wells, UK). All treatments were supplied with modified full strength Netherlands Standard Composition nutrient solution (Douglas, 1985) with 2.0 ± 0.2 mS cm-1 conductivity and pH 6.0 ± 0.2. The modified full strength Netherlands Standard Composition solution had the following composition: N, 191.89 ppm; P, 33.29 ppm; K, 309.00 ppm; Ca, 210.29 ppm; Mg, 60.04 ppm; S, 125.45 ppm; Fe, 9.36 ppm; B, 0.105 ppm; Mn, 0.238 ppm; Zn, 0.014 ppm; Cu, 0.015 ppm; Mo, 0.408 ppm; Na, 3.860 ppm. The fluctuating ambient temperatures of 24–43 °C and relative humidity of 26–96 % were recorded using DataHog2 (Skye Instruments Ltd, UK).

2.2. Measurements of leaf fresh weight (FW) and dry weight (DW), leaf area, specific leaf area (SLA) and leaf water content

The just-emerged leaves of I. batatas plants were labeled 27 days after transplanting and they were harvested one week after emergence from 0730 h to 0800 h. The cut leaves were kept in sealed plastic bags with sheets of damp paper towel and brought back to lab. The FW of leaf (blade only) was first recorded before measuring their areas using a leaf area meter (WinDIAS3 Image Analysis system). All leaves were then wrapped individually in pre-weighed aluminium foil, dried at 80 °C for at least four days, before re-weighing them to obtain DW. Specific leaf area (SLA) was determined as LA/LDW where LA = leaf area (cm2) and LDW = leaf DW(g) (Hunt et al., 2002). Leaf water content (LWC) was determined as (LFW − LDW)/LFW where LFW = leaf FW (g).

2.3. Measurements of Chl and carotenoids (Car) pigments

For each measurement, two leaf discs (1 cm in diameter) were cut from the youngest fully expanded leaves 15 days after transplanting and soaked in 2.5 ml of N,N-dimethylformamide (N,N-DMF, Sigma Chemical Co.) in darkness for 48 h at 4 °C. The absorption of pigments were measured using a spectrophotometer (UV-2550 Shimadzu, Japan) at 647 nm, 664 nm and 480 nm respectively. Chl a, Chl b and Car concentrations were calculated as described by Wellburn (1994).

2.4. Measurements of predawn and midday Fv/Fm ratio

The maximum photochemical efficiency of PS II was estimated in dark-adapted samples by the Fv/Fm ratio. Predawn and midday Fv/Fm ratios were measured from the attached youngest fully expanded leaves in the greenhouse before photoperiod and during mid-photoperiod on sunny days after transplanting for 34 days using the Plant Efficiency Analyser (Hansatech Instruments, UK) according to He et al. (2001).

2.5. Measurements of electron transport rate (ETR), photochemical quenching (qP) and non-photochemical quenching (NPQ)

After 30 days of transplanting, the youngest fully expanded leaves were harvested between 0900 h–1000 h and ETR, qP and NPQ were determined at 25 °C in the laboratory. Prior to measurements, the leaves were pre-darkened for 15 min. By using the IMAGING PAM MAXI (Walz, Effeltrich, Germany), images of fluorescence emission were digitized within the camera and transferred via ethernet interface (GigEVision®) to the PC for storage and analysis. Measurements and calculations of ETR, qP and NPQ were described previously (He et al., 2017b).

2.6. Measurements of light response curves of net photosynthetic O2 evolution rate (PN), PS II concentration and Cyt b6f concentration

These parameters were measured according to He and Chow (2003), and Zhu et al. (2017). O2 evolution from leaf discs was measured in a gas-phase oxygen electrode (Hansatech, King’s Lynn, UK) chamber maintained at 25 °C. Each leaf disc was 3.4 cm2 in area, punched from the similar part of the youngest fully expanded I. batatas leaves grown under different light conditions. The sample chamber contained 1% CO2 supplied by fabric matting moistened with 1 M NaHCO3/Na2CO3 (pH 9). Two illumination regimes were used: (1) repetitive flash illumination with saturating, single-turnover flashes, or (2) continuous white light from light emitting diodes. First, repetitive flash illumination of the leaf sample with saturating, single-turnover xenon flashes (at 10 Hz) was performed to obtain a net rate of O2 evolution on a leaf area basis. Following an initial dark equilibration for 10 min, the repetitive flash illumination was applied for 4 min, followed by 4 min darkness. This was followed by a second cycle of flashes and darkness. The average dark drift in the signal before and after repetitive-flash illumination was subtracted algebraically from the net rate of O2 evolution during flash illumination to obtain the gross rate of flash-induced O2 evolution. A small heating artefact signal due to flash illumination was obtained by substituting a green paper disc for a leaf disc, and was corrected for. The limitation of linear electron transport by PS I was minimized by the use of background far-red light. The ratio of the gross rate of O2 evolution to the flash frequency was used to derive the PS II concentration on a leaf area basis (p), assuming that after four flashes, each active PS II evolves one O2 molecule (Chow et al., 1991). Second, after repetitive-flash illumination, a light response curve of PN was measured under continuous white light. The leaf disc was illuminated at 15 different light intensities, starting from the lowest PPFD of 0–1870 μmol m−2 s–1. The leaf disc was illuminated at each PPFD over several minutes until steady-state of photosynthetic O2 evolution rate was obtained. The saturating, continuous irradiance (1870 μmol m− s–1) was used to determine the photosynthetic capacity (Pmax). The post-illumination drift was subtracted algebraically from the steady-state net O2 evolution rate at PPFD of 1870 μmol m−2 s–1 to yield the gross O2 evolution rate, Pmax. For calibration of the oxygen signals, 1 ml of air at 25 °C (taken to contain 8.584 μmol O2) was injected into the gas-phase O2 electrode chamber.

Calculation of the Cyt b6f concentration: After measurements of p and Pmax, the Cyt b6f concentration (f) was calculated from the equation, Pmax = 1/[(0.022/f)+(0.004/p)], all parameters being on a leaf area basis. The Cyt b6f concentration, calculated from the two activity measurements, represents the functional Cyt b6f concentration in leaves (Zhu et al., 2017)

2.7. Measurements of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate (A), stomatal conductance (gs), internal CO2 concentration (Ci) and transpiration (Tr)

A, gs, Ci and Tr were measured from the youngest fully expanded attached leaves under growth irradiances in the greenhouse using the LI-COR Portable Photosynthetic System (LI-6400. Bioscience, USA) from 1030 h to 1230 h. During the measurement, the average ambient CO2 concentration in the greenhouse was 383 ± 6 μmol mol−1, the relative humidity was 40 ± 10 % and the temperature was 39 ± 4 °C. The measurement was performed twice on both the 44th and 45th days after transplanting. The results presented were the means of data collected in these two days.

2.8. Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significant differences of variances crossed with the three different treatments. LSD multiple comparison tests were used to discriminate between means of the different treatments, where means with p < 0.05 has significant differences (IBM, SPSS Version 25).

3. Results

3.1. Leaf growth, leaf productivity and leaf water content

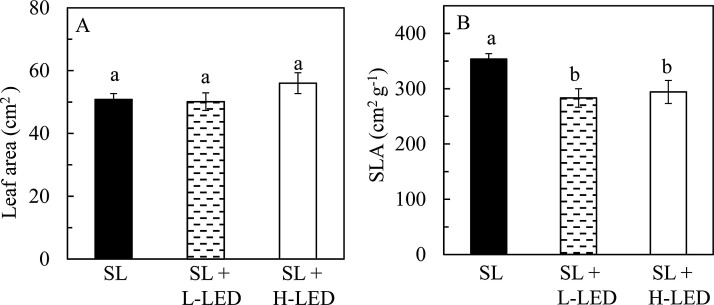

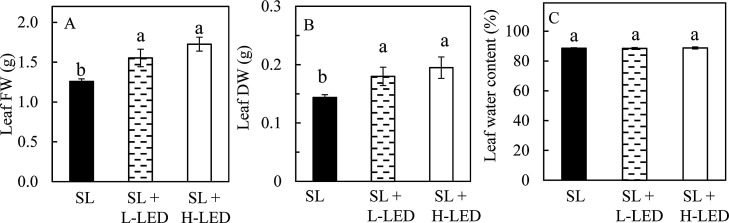

It was observed that all leaves were fully expanded after one week emergence regardless of growth irradiances. Fig. 1 shows an average leaf area and a SLA of fully-expanded leaves developed under different growth irradiances. Although the average leaf area of sweet potato leaves grown under SL + H-LED (56 cm2) was slightly larger than those grown under SL + L-LED (50 cm2) and SL (51 cm2), statistically, there were no significant differences in their values (Fig. 1A). However, sweet potato leaves grown under SL had significantly higher SLA compared to those grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED (Fig. 1B). For leaf FW and leaf DW, they were significantly higher in sweet potato plants grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED than under only natural SL (Fig. 2 A and B). However, all leaves had similar water content (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

Leaf area (A) and SLA (B) of the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 5) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

Fig. 2.

Leaf FW (A), leaf DW (B) and leaf water content of the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 5) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

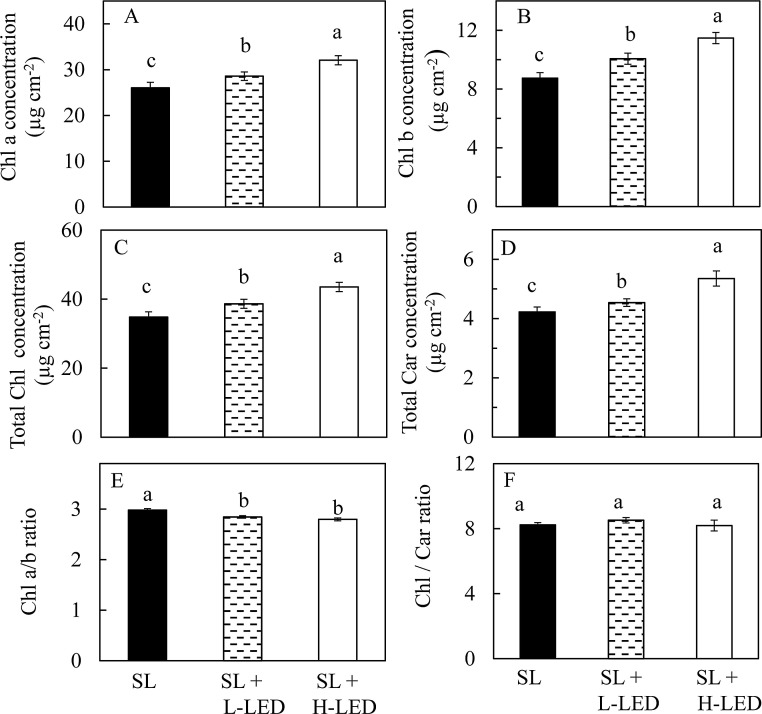

3.2. Photosynthetic pigments

Sweet potato leaves grown under SL + H-LED had the highest concentrations of Chl a, Chl b, total Chl and total Car followed by those grown under SL + L-LED. For plants grown under SL, their leaves had the lowest Chl a, Chl b, total Chl and total Car concentrations (Fig. 3 A–D). However, Chl a/b ratio of sweet potato leaves grown under SL was significantly higher than those grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED (Fig. 3E). There were no significant differences in Chl/Car ratios among the leaves grown under different light conditions (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Chl a concentration (A), Chl b concentration (B), total Chl concentration (C), total Car concentration (D), Chl a/b ratio (E) and Chl/Car ratio (F) of the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 6) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

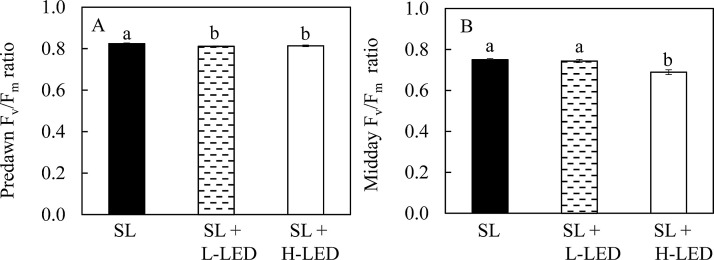

3.3. Photosynthetic light utilization efficiency measured by Fv/Fm ratio, ETR, qP and NPQ

Fig. 4 shows the predawn and midday Fv/Fm ratios measured from the attached leaves on the same sunny day in the greenhouse. The measurements were repeated once on another sunny day and similar results were obtained. All leaves had their predawn Fv/Fm ratios greater than 0.8 although leaves grown under SL had Fv/Fm ratio significantly higher than those grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED (Fig. 4A). Leaves grown under SL + H-LED had significantly lower midday Fv/Fm ratio (0.689) than those grown under SL (0.750) and SL + L-LED (0.744) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Pre-dawn (A) and midday (B) Fv/Fm ratios on a sunny day measured from the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 8) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

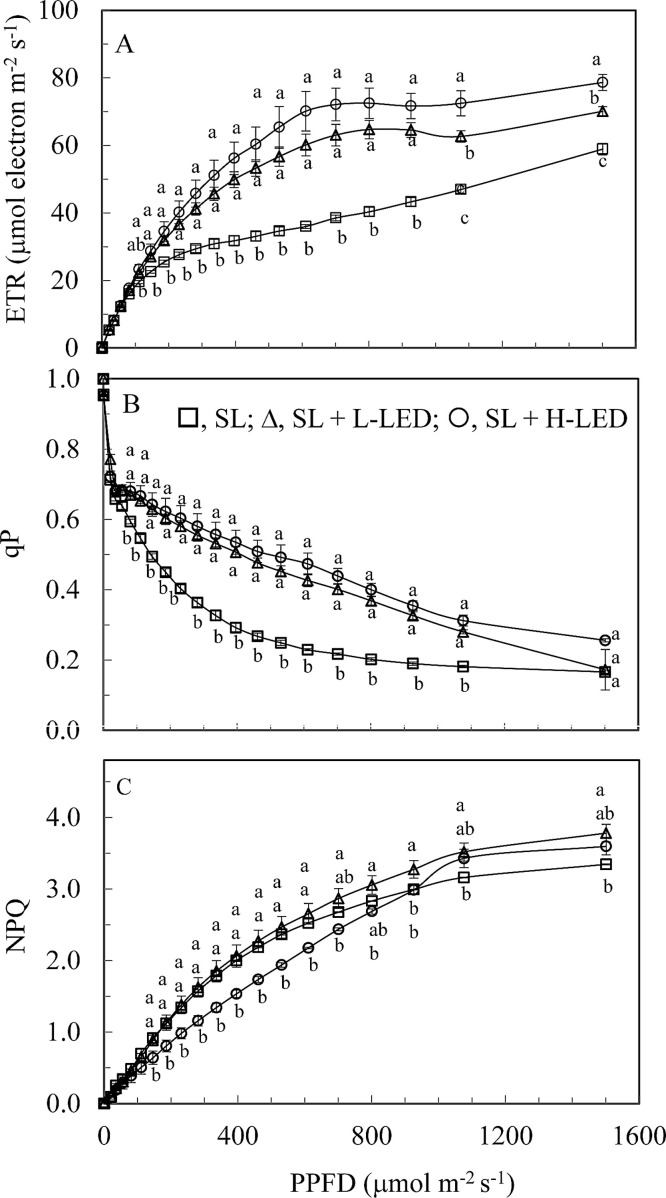

The youngest fully expanded leaves were also harvested to measure the light response curves of ETR, qP and NPQ, starting from the lowest PPFD of 0–1501 μmol m−2 s–1. The measurements were repeated once on a different day and similar results were obtained. The readings of ETR increased as PPFDs increased from 0–1501 μmol m–2 s–1 for all leaves (Fig. 5 A). All leaves had similar values of ETR when they were measured under PPFDs <111 μmol m−2 s–1. However, leaves grown under SL had significantly lower ETR compared to those grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED when they were measured under PPFDs from 146 to 1501 μmol m−2 s–1. Measured under the two highest PPFDs of 1076 and 1501 μmol m−2 s–1, leaves grown under SL + H-LED had the highest ETR, followed by those grown under SL + L-LED and the leaves grown under SL had the lowest ETR under these two PPFDs (Fig. 5A). The values of qP decreased with increasing PPFDs from 0–1501 μmol m−2 s-1 for all leaves (Fig. 5B). All leaves had similar decrease rates of qP when they were measured under PPFDs from 0 to 56 μmol m−2 s–1. However, decreases in qP were significantly faster in leaves grown under SL than under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED when measured under PPFDs above 81 μmol m−2 s–1 except for the higher PPFD of 1501 μmol m−2 s–1, under which all leaves had similar lowest level of qP (Fig. 5B). Similar to the changes of ETR, NPQ of all leaves increased with increasing PPFDs from 0–1501 μmol m−2 s–1 (Fig. 5C). When measured under PPFDs <146 μmol m−2 s–1, all leaves had similar levels of NPQ. Leaves grown under SL + H-LED had significantly lower NPQ compared to those grown under SL + L-LED and SL under PPFDs from 146 to 611 μmol m−2 s–1. However, under the two highest PPFDs of 1076 and 1501 μmol m−2 s–1, NPQ values were similarly higher in leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED than under SL (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Light response curves of ETR (A), qP (B) and NPQ (C) measured from the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 4) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

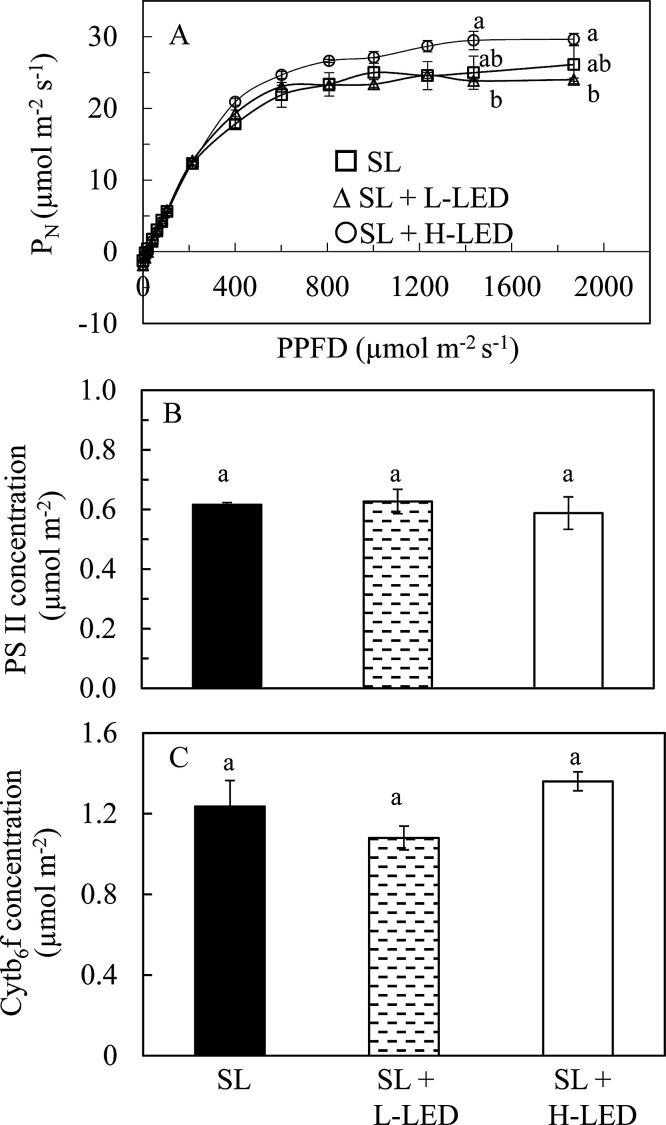

3.4. Light response curves of PN, PS II and Cyt b6f concentrations of detached leaves measured in the laboratory

Fig. 6 shows light response curves PN, PS II and Cyt b6f concentrations measured from the same detached leaves in the laboratory at 25 °C. PN increased with increasing PPFDs similarly in all leaves from 0 to 602 μmol m−2 s–1, and started to saturate between 602–808 μmol m−2 s–1 (Fig. 6A), after which, slow increases of PN were still observed from 808 to 1435 μmol m−2 s–1 in leaves grown under SL + H-LED. Thus, the light response curve of PN measured from leaves grown under SL + H-LED was above those grown under SL + L-LED and SL. Measured under the two highest PPFDs of 1435 and 1870 μmol m−2 s–1, leaves grown under SL + H-LED had significantly higher PN than those grown under SL + L-LED while leaves grown under SL + H-LED and SL had similar PN (Fig. 6A). However, there were no significantly differences in PS II (Fig. 6B) and Cyt b6f (Fig. 6C) concentrations among the sweet potato leaves grown under different light conditions.

Fig. 6.

Light response curves of photosynthetic O2 evolution (A), PS II concentration (B) and Cyt b6f concentration (C) measured from the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 3) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

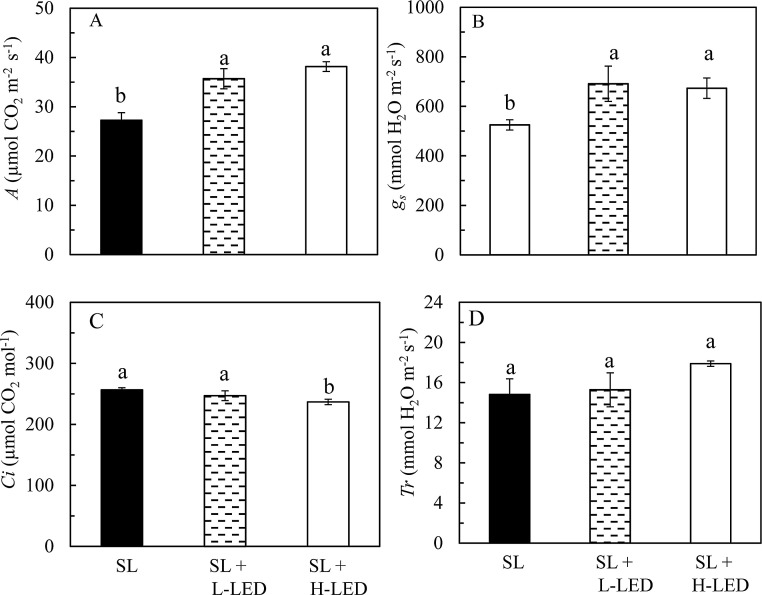

3.5. A, gs, Ci, Tr of attached leaves measured in the greenhouse

Fig. 7 A and B show the results of A and gs of sweet potato leaves measured under their respective growth irradiance with similar but much higher values obtained from leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED than under SL. The Ci was significantly lower in leaves grown under SL + H-LED compared to those grown under SL + L-LED and SL (Fig. 7C). However, all leaves had similar Tr (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate, A (A), stomatal conductance, gs (B), internal CO2 concentration, Ci (C) and transpiration, Tr (D) measured from the youngest fully expanded leaves of I. batatas grown under different light conditions. Means with different letters are statistically different (P < 0.05; n = 6) as determined by LSD multiple comparison test. SL, Sunlight; SL + L-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 150 μmol m−2 s−1; SL + H-LED, SL with supplemental LED at a PPFD of 300 μmol m−2 s−1.

4. Discussion

Although sweet potato leaves have been consumed in Singapore as a high nutritional leafy vegetable, they are mainly cultivated in outdoor soil farms. The supply of sweet potato leaves to the vegetable markets is not secured due to the fact that its productivity is influenced by variation in sunlight availability and intensity. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first project to grow sweet potato leaves in the tropical greenhouse using hydroponic systems under supplemental LED lighting to prevailing natural sunlight. Light is the most crucial factor for plant growth and development as well as the efficiency of the photosynthesis (Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2017; Gommers, 2020). Plants can adjust their morphological and physiological traits such as leaf size, SLA, leaf mass and Chl content when they are subjected to changing light conditions (Liu et al., 2016; He et al., 2017a). This study was carried out in the tropical greenhouse from the middle of February to early April 2020, when the weather was warm and sunny. The average highest ambient temperature was about 34–36 °C under full sunlight and maximum PPFD in an open field on sunny days outside the greenhouse ranged from 1400 to 1600 μmol m−2 s–1 for at least 4 h from 1100 h to 1500 h. However, the average maximum PPFD inside the greenhouse was round 700–800 μmol m−2 s–1, which was 50 % of full sunlight but the average ambient temperature could be as high as 38–40 °C with the highest of 43 °C during midday for at least 4 h. It was a surprise to observe that inside the hot greenhouse, the leaves of all sweet potato plants grew very fast and were very healthy, especially those grown under SL supplemented with constant PPFDs of either 150 (SL + L-LED) or 300 μmol m−2 s-1 (SL + H-LED), for a 12 h photoperiod. These observations were supported by the results shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. Although there was no significant difference in leaf area of the youngest fully expanded leaves grown under different light conditions one week after emergence (Fig. 1A), leaf FW and DW were significantly higher in leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED than under SL alone (Fig. 2A and B). All leaves had similar water content (Fig. 2C) and thus, higher leaf FW and DW resulted from the greater thickness of those grown under supplemental LED lighting, which was supported by the lower SLA (Fig. 1B). Low SLA is associated with greater leaf thickness as SLA is measured as the ratio of leaf area to leaf dry mass (Hunt et al. 2002). It was previously reported by our studies that both light quantity and quality affected SLA of leafy vegetables within the species (Choong et al., 2018; He et al., 2019).

Grown under low-light conditions, plants usually develop leaves with higher SLA compared to those grown under high-light conditions (He et al., 2017a; Vialet-Chabrand et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019). According to Poorter et al. (2018), light-capture-related traits such as SLA and Chl content are strongly related to light, and therefore vary mostly within species. The higher SLA of sweet potato leaves grown under low-light conditions such as only SL (Fig. 1B) could be interpreted as a mechanism to optimize light harvesting. However, under high-light conditions such as SL + H-LED conditions, lower SLA (Fig. 1B) could help plants to increase the efficiency of light capture (Evans and Poorter, 2001; Liu et al., 2016). In the study with soybean, Fan et al. (2018) and Feng et al. (2019) reported that Chl a, Chl b, total Chl and Car contents increased with the increase in light intensity, which were directly associated with leaf thickness. The results of this study with potato leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED conditions having higher Chl a, Chl b, total Chl and Car concentrations on a per area basis (Fig. 3A–D) are consistent with those previous results (Fan et al., 2018; Feng et al., 2019). However, Anderson et al. (1988) demonstrated that it was not the Chl concentration per leaf area but the ratio of Chl a/b showed a close correlation to the growth irradiance. In this study, when growth irradiance was increased by supplementing LED lighting to SL, Chl a/b ratio of sweet potato leaves decreased (Fig. 3E). Increasing light intensity decreased Chl a/b ratio was also reported in soybean (Feng et al., 2019). These results are not in accordance with the usually increased Chl a/b ratio of plants grown under high-irradiance compared to those grown under low-irradiance (Evans and Poorter, 2001). Zivcak et al. (2014) suggested that effects of light intensity on Chl a/b ratio is not a universal phenomenon and the dependence of Chl a/b ratio on light intensity is strongly correlated to plant species. In this study, the supplemental LED-lighting was provided by a combination of red- and blue-LED lighting in the ratio of 9:1. The effects of light conditions on Chl a/b ratio could result from both the light intensity and light quality, which merits our further study. Car concentration of sweet potato leaves increased by 8 and 27 %, under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED respectively, compared to those grown under SL alone (Fig. 3D). Generally, Car concentration was higher for sun-acclimated leaves compared to that of shade-grown leaves (Demmig-Adams and Adam, 1996; Lichtenthaler, 2007). Carotenoids play important roles in photosynthesis (Pogson et al., 2005) and protect plants from the harmful effects of excess exposure to light by maintaining proper Chl/Car ratio (or Car/Chl ratio) for optimal photosynthesis and photoprotection (Hashimoto et al., 2016). All sweet potato leaves had similar Chl/Car ratios as those grown under higher growth irradiance increased the concentrations of both total Chl and total Car concentrations (Fig. 3C and D). In the study with barley leaves (Hordeum vulagare L.), Zivcak et al. (2014) also reported that no significant changes were observed in the Chl/Car ratio between sun and shade leaves.

Biosynthesis of Chl increases with increasing light intensity (Björkmann, 1981). However, under adverse environmental conditions such as high temperature, high light inhibits Chl formation due to photoinhibition (He et al., 1996). In this study, all leaves had predawn Fv/Fm ratio > 0.8 (Fig. 4A), indicating that no chronic photoinhibition occurred in any plants. However, dynamic photoinhibition occurred in all leaves during midday with Fv/Fm ratios < 0.8. The greatest decrease of midday Fv/Fm ratio was observed in leaves grown under SL + H-LED, which were exposed to the highest PPFD about 1150 μmol m−2 s−1. The midday Fv/Fm ratio remained higher for leaves of plants grown under SL with the lowest midday PPFD (700–800 μmol m−2 s-1). Grown under SL + L-LED subjected to a PPFD of 1000 μmol m−2 s-1, the decrease of midday Fv/Fm ratio was in-between (Fig. 4B). Similar to the results of this study, grown under natural conditions with dynamic fluctuations in light, high PPFDs coupled with high temperature during midday caused dynamic photoinhibtion but no sustained chronic photoinhibition were observed in certain native orchid species in Singapore (He et al., 2017a; Tay et al., 2019).

Chls are essential molecules that catch light energy to drive photosynthetic electron transfer (Fromme et al., 2003). Sweet potato leaves grown under high-irradiance had thicker leaves and higher Chl concentrations are associated with higher ETR compared to those grown under low-irradiance (Fig. 5A). When measurements were carried out from 801 to the highest 1501 μmol m−2 s-1, which were within the maximum ranges of PPFD under which all leaves were developed, the ETR readings were 80–98 % and 55–75 % respectively higher in SL + H-LED and SL + L-LED leaves than that in leaves grown under SL (Fig. 5A). Not only ETR but also qP was modified by the light conditions, with slower declines in qP in leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED compared to that in leaves grown under SL except for the measurements at the higher PPFD of 1501 μmol m−2 s-1 (Fig. 5B). The values of qP were significantly higher for the leaves grown under high-irradiance such as SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED than those under lower irradiance of SL inside the greenhouse, indicating that high-irradiance improve photosynthetic light use efficiency (Feng et al., 2019). It was reported that high growth irradiance increased ETR and qP while decreased the NPQ (Zivcak et al., 2014; Feng, 2019). These were also observed in this study with sweet potato leaves grown under SL + H-LED had low NPQ when measurements were made from 146 to 611 μmol m−2 s−1 compared to those grown under SL. However, decreased NPQ was not observed in leaves grown under SL + L-LED (Fig. 5C).

High growth irradiance enhances ETR and qP that could increase photosynthetic rate by improving the energy transport from PSII to PSI in tobacco leaves (Yamori et al., 2010) and soybean leaves (Yang et al., 2018). It was also reported earlier that pea leaves grown under high-light had higher concentrations of PS II and Cyt b6f and thus a higher capacity for electron transport and photosynthetic oxygen evolution compared to those grown under low-light (Leong and Anderson, 1984; Chow and Anderson, 1987). Similar results were also reported in spinach (Chow and Hope, 1987), Alocasia macrorrhiza (Chow et al., 1988) and Hordeum vulgarae (De la Torre and Burkey, 1990). However, in this study, sweet potato leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED increased ETR and qP while the concentrations of PS II (Fig. 6B) and Cyt b6f (Fig. 6C) remained unchanged compared to those grown under SL. Higher ETR and qP observed in this study may be due to the tuning of the amount of active PSII reaction centres and regulating the electron transfer by the Cyt b6f complex (Tikkanen et al., 2012) rather than the modified concentrations. As all leaves in this study were developed under the maximum PPFDs about 700–800 μmol m−2 s-1 where PN started to saturate (Fig. 6A), they may have produced maximum amount of PS II and Cyt b6f complex. On the other hand, PN was measured at the temperature (25 °C) lower than the maximum growth temperature of sweet potato leaves, which may also be another factor affecting the values of PN (to be discussed in the next section). In our future study, corrections among ETR, qP, PS II, Cyt b6f and PN in sweet potato leaves should be carried out under different light intensity and different leaf temperatures.

Many studies have shown that PS II and Cyt b6f may be the site of the rate-limiting step in the electron transport (Heber et al., 1988; Eichelmann et al., 2000). The concentration of Cyt b6f is the main rate-limited factor that determines light and CO2-satuated photosynthetic capacity (Tikkanen et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2017). In this study, there was a slightly higher PN measured from leaves grown under SL + H-LED at the highest PPFD of 1870 μmol m−2 s-1 compared to that of leaves grown under SL (Fig. 6A), which could be due to the similar concentrations of Cyt b6f (Fig. 6B) among all leaves.

Although all detached leaves had similar PN measured at 25 °C in the laboratory under saturated CO2 (Fig. 6A), there were significant differences in A, gs, and Ci, measured from attached leaves under their respective growth irradiance in the greenhouse (Fig. 7). Generally, leaves developed under high-irradiance are thicker than those grown under low-irradiance and thus enhance light use efficiency for carbon fixation (Terashima et al., 2006). In their paper, Terashima et al. (2006) confirmed that there were sufficient mesophyll surfaces in the thicker sun leaves for CO2 dissolution and transport to the chloroplasts. Thicker sun leaves of C3 plants could maintain the CO2 concentration in the chloroplast as high as possible for ribulose 1.5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco) (Terashima et al., 2006). Furthermore, thicker leaves accumulated more photosynthetic enzymes on a leaf area basis and thus contributed to greater CO2 fixation capacity of high-light grown leaves (Evans and Poorter, 2001). The results of this study support those earlier studies as photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate, A was 31 and 40 % higher in SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED, respectively than that of SL (Fig. 7A). Generally, plants grown at higher temperature have a higher optimal temperature of photosynthetic rate (Yamasaki et al., 2002). In many species, the optimal temperature of photosynthetic rate increases with increasing growth temperature (Hikosaka et al., 2006). These earlier studies explain why the values of A (Fig. 7A) measured from the attached leaves in the greenhouse with their leaf temperatures as high as 38–43 °C under ambient CO2 were higher than those of PN (Fig. 6A) measured from detached leaves at 25 °C in the presence of a saturating CO2 concentration in the laboratory. It has been reported that gs is sensitive to temperature, humidity and light (Bunce, 2001; Lawson, 2009). Generally, high temperature promotes stomatal opening to facilitate leaf cooling. In this study, there were small variations in leaf temperature and humidity among sweet potato leaves as they were grown in the same area of the same greenhouse. However, the values of gs were significantly higher in sweet potato leaves grown under SL + L-LED and SL + H-LED than that of leaves grown under SL (Fig. 7B). Different light conditions could be the main factors resulting in different gs. Optimal combinations of blue- and red-LED used in this study could enhance gs, which have been previously reported in cucumber (Hernández and Kubota, 2016) and lettuce (Wang et al., 2016; Choong et al., 2018). It is well known that stomata are responsible for balancing photosynthetic CO2 uptake with water loss through transpiration. Although it was unable to measure the root biomass in this study, all sweet potato plants had well developed big root systems to ensure water and nutrient uptake (Poorter et al., 2012). Thus, all leaves had similar transpiration rate (Fig. 7D) although leaves grown under SL had significantly lower gs compared to those grown under SL supplemented with LED lighting.

In certain species, the greater A by plants grown under high-irradiance means that they have lower Ci than those grown under low-irradiance (Hanba et al., 2002; Yamori et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2014). For instance, Huang et al. (2014) reported that sun-grown tobacco leaves had greater A, leading to lower Ci. In this study, sweet potato leaves grown under the highest irradiance (SL + H-LED) also had the highest A which was as high as 38.1 μmol CO2 m−2 s−1 (Fig. 7A) and the lowest Ci of 236.8 μmol CO2 mol-1 compared to those grown under low-irradiance (Fig. 7C). Lower Ci could result in higher ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (RuBP) oxygenation rate in sun-grown-leaves than in shade-grown leaves and thus upregulate photorespiratory pathway. However, lower Ci of sun-grown leaves also increased RuBP regeneration resulting from higher electron transport capacity and thus RuBP oxygenation and regeneration were balanced (Foyer et al., 2012; Huang et al., 2014). In this study, sweet potato leaves grown under high-irradiance also had higher electron transport capacity (Fig. 5A). Instead of suppressing A, enhancement of photorespiratory pathway through enhanced RuBP regeneration potentially improved the A in Arabidopsis thaliana (Timm et al., 2012) and tobacco leaves (Huang et al., 2014). Sweet potato leaves grown in the tropical greenhouse under high-irradiance may also have higher photorespiration which enhanced photosynthetic CO2 assimilation and at the same time prevented them from suffering sustained chronic photoinhibition supported by their predawn Fv/Fm ratios of greater than 0.8 (Fig. 3A). Changes in the light dependence of photosynthesis may be ascribed to changes in not only CO2 concentration in the chloroplasts but also the activity and amount of photosynthetic components especially the activation and the amount of Rubisco (Simkin et al., 2015, 2019). Compared to sweet potato leaves grown under low-irradiance such as SL only, leaves grown under high-irradiance such as SL+ H-LED probably have increased synthesis of Rubisco. Supplemental LED lighting to SL increased total leaf soluble protein and Rubisco protein of Cos lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) grown in the same greenhouse (unpublished data). In this study, samples have been collected for the analysis of total leaf soluble protein and Rubisco protein. Unfortunately, we were unable to determine these parameters as we had to close our laboratory due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The effects of light on Rubisco protein would be studied in near future. We also hypothesize that supplementing LED to natural SL enhances not only leaf growth and photosynthetic characteristics of sweet potato leaves in a tropical greenhouse but also their nutritional quality, which also merits our further study.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study show that supplemental LED lighting to natural SL increased leaf fresh and dry weights of hydroponically grown sweet potato (I. batatas var. Biru Putih) in the hot tropical greenhouse. The enhancement of leaf biomass was due to the increased thickness of high-irradiance grown leaves, which improved electron transport capacity and photosynthetic CO2 assimilation rate of attached leaves under their growth temperature and irradiances. Corrections among ETR, qP, PS II, Cyt b6f, PN and Rubisco protein in sweet potato leaves under different light intensities and different leaf temperatures merit our further study.

Author contributions

JH initiated and funded the expenses for the project, planned and carried out some parts of the experiments and wrote most part of the manuscript. LQ planned, carried out most experiments, analyzed the data and wrote some part of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jie He: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Lin Qin: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Singapore Millennium Foundation (SMF-Farming System) and National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore for providing us with the funding and facility support.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153239.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- Ai-Lien C. The Straits Times. Singapore Press Holdings; Singapore: 2019. Singapore sets 30% goal for home-grown food by 2030.https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spore-sets-30-goal-for-home-grown-food-by-2030 (Accessed 8 March 2019) [Google Scholar]

- An L.V., Frankow-Lindberg B.E., Lindberg J.E. Effect of harvesting interval and defoliation on yields and chemical composition of leaves, stems and tubers of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas l. (Lan.)) plant parts. Field Crops Res. 2003;82:49–58. doi: 10.1016/S0378-4290(03)00018-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J.M., Chow W.S., Goodchild D.J. Thylakoid membrane organisation in sun/shade acclimation. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1988;15:11–26. doi: 10.1071/PP9880011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Björkmann O. Responses to different quantum flux densities. In: Lange O.K., Nobel P.S., Osmond C.B., Ziegler H., editors. Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology, N.S., Vol. 12A, Physiological Plant Ecology I. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg, New York: 1981. pp. 57–107. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce J.A. Responses of stomatal conductance to light, humidity and temperature in winter wheat and barley grown at three concentrations of carbon dioxide in the field. Glob. Change Biol. 2001;6:371–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00314.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choong T.W., He J., Qin L., Lee S.K. Quality of supplementary LED lighting effects on growth and photosynthesis of two different Lactuca recombinant inbred lines (RILs) grown in a tropical greenhouse. Photosynthetica. 2018;56:1278–1286. doi: 10.1007/s11099-018-0828-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chow W.S., Anderson J.M. Photosynthetic responses of Pisum sativum to an increase in irradiance during growth. II. Thylakoid membrane components. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1987;14:9–19. doi: 10.1071/PP9870009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chow W.S., Hope A.B. The stoichiometries of supramolecular complexes in thylakoid membranes from spinach chloroplasts. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1987;14:21–28. doi: 10.1071/PP9870021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chow W.S., Qian L., Goodchild D.J., Anderson J.M. Photosynthetic acclimation of Alocasia macrorrhiza (L.) G. Don to growth irradiance: structure, function and composition of chloroplasts. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1988;15:107–122. doi: 10.1071/PP9880107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chow W.S., Hope A.B., Anderson J.M. Further studies on quantifying photosystem II in vivo by flash-induced oxygen yield from leaf discs. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 1991;18:397–410. doi: 10.1071/PP9910397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De la Torre W.R., Burkey K.O. Acclimation of barley to changes in light intensity: photosynthetic electron transport activity and components. Photosynth. Res. 1990;24:127–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00032593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demmig-Adams B., Adam W.W. The role of xanthophyll cycle carotenoids in the protection of photosynthesis. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:21–26. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(96)80019-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas J.S. Advanced guide to hydroponics. Pelham Books, London. 1985 [Google Scholar]

- Eichelmann H., Price D., Badger M., Laisk A. Photosynthetic parameters of wild-type and Cytb6/f deficient transgenic tobacco studied by CO2 uptake and transmittance at 800 nm. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000;41:432–439. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.4.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J.R., Poorter H. Photosynthetic acclimation of plants to growth irradiance: the relative importance of specific leaf area and nitrogen partitioning in maximizing carbon gain. Plant Cell Environ. 2001;24:755–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00724.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Chen J., Cheng Y., Raza M.A., Wu X., Wang Z. Effect of shading and light recovery on the growth, leaf structure, and photosynthetic performance of soybean in a maize-soybean relay-strip intercropping system. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L., Raza M.A., Li Z., Chen Y., Khalid M.H.B., Du J., Liu W., Wu X., Song C., Yu L., Zhang Z., Yuan S., Yang W., Yang F. The influence of light intensity and leaf. movement on photosynthesis characteristics and carbon balance of soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;9:1952. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer C.H., Neukermans J., Queval G., Noctor G., Harbinson J. Photosynthetic control of electron transport and the regulation of gene expression. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:1637–1661. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme P., Melkozernov A., Jordan P., Krauss N. Structure and function of photosystem I: interaction with its soluble electron carriers and external antenna systems. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:40–44. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(03)01124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghuman B.S., Lal R. Mulch and irrigation effects on plant-water relations and performance of cassava and sweet potato. Field Crops Res. 1983;7:13–29. doi: 10.1016/0378-4290(83)90003-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gommers C.M.M. Adapting to High Light: At a Different Time and Place? Plant Physiol. 2020;182:10–11. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.01445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanba Y.T., Kogami H., Terashima I. The effect of growth irradiance on leaf anatomy and photosynthesis in Acer species differing in light demand. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25:1021–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2002.00881.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto H., Uragami C., Cogdell R.J. Carotenoids and photosynthesis. Subcell. Biochem. 2016;79:111–139. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-39126-7_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J. 2015. Farming of Vegetables in Space-limited Environments; pp. 21–36. 2015 Cosmos 11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Chow W.S. The rate coefficient of repair of photosystem II after photoinactivation. Physiol. Plant. 2003;118:297–304. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00107.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Chee C.W., Goh C.J. “Photoinhibition” of Heliconia under natural tropical conditions- Importance of leaf orientation for light interception and leaf temperature. Plant Cell Environ. 1996;19:1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00002.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Cheok L., Qin L. Nitrate accumulation, productivity and photosynthesis of temperate butter head lettuce under different nitrate availabilities and growth irradiances. Open Hortic. J. 2011;4:17–24. doi: 10.2174/1874840601104010017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Lim R.M.P., Dass S.H.J., Yam T.W. Photosynthetic acclimation of Grammatophyllum speciosum to growth irradiance under natural conditions in Singapore. Bot. Stud. 2017;58:58. doi: 10.1186/s40529-017-0210-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Qin L., Chong E.L.C., Choong T.W., Lee S.K. Plant growth and photosynthetic characteristics of Mesembryanthemum crystallinum grown aeroponically under different blue- and red-LEDs. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:361. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Qin L., Chow W.S. Impacts of LED spectral quality on leafy vegetables: productivity closely linked to photosynthetic performance or associated with leaf traits? Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019;12:16–25. doi: 10.25165/j.ijabe.20191206.5178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Qin L., Teo L.J.L., Choong T.W. Nitrate accumulation, productivity and photosynthesis of Brassica alboglabra grown under low light with supplemental LED lighting in the tropical greenhouse. J. Plant Nutr. 2019;42:1740–1749. doi: 10.1080/01904167.2019.1643367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heber U., Neimanis S., Dietz K.J. Fractional control of photosynthesis by the QB protein, the cytochrome f/b6 complex and other components of the photosynthetic apparatus. Planta. 1988;173:267–274. doi: 10.1007/BF00403020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández R., Kubota C. Physiological responses of cucumber seedlings under different blue and red photon flux ratios using LEDs. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016;121:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.04.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka K., Ishikawa K., Borjigidai A., Muller O., Onoda Y. Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis: mechanisms involved in the changes in temperature dependence of photosynthetic rate. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:291–302. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Zhang S.B., Hu H. Sun leaves up-regulate the photorespiratory pathway to maintain a high rate of CO2 assimilation in tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 2014;5:688. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R., Causton D.R., Shipley B., Askew A.P. A modern tool for classical plant growth analysis. Ann. Bot. 2002;90:485–488. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H., Suzuno H., Sugiyama N., Innami S., Tadokoro T., Maekawa A. Nutritive evaluation on chemical components of leaves, stalks and stems of sweet potatoes (Ipomoea batatas poir) Food Chem. 2000;68:359–367. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00206-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M., Pace R.D. Sweet potato leaves: properties and synergistic interactions that promote health and prevent disease. Nutr. Rev. 2010;68:604–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.S. ASEAN and transbourndary haze pollution in Southeast Asia. Asia Eur. J. 2006;4:431–446. doi: 10.1007/s10308-006-0067-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurata R., Adachi M., Yamakawa O., Yoshimoto M. Growth suppression of human cancer cells by polyphenolics from sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas L) leaves. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007;55:185–190. doi: 10.1021/jf0620259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson T. Guard cell photosynthesis and stomatal function. New Phytol. 2009;181:13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong T.Y., Anderson J.M. Adaptation of the thylakoid membranes of pea chloroplasts to light intensities. II. Regulation of electron transport capacities, electron carriers, coupling factor (CF1) activity and rates of photosynthesis. Photosynth. Res. 1984;5:117–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00028525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthaler H.K. Biosynthesis, accumulation and emission of carotenoids, alpha-tocopherol, plastoquinone, and isoprene in leaves under high photosynthetic irradiance. Photosynth. Res. 2007;92:163–179. doi: 10.1007/s11120-007-9204-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K.H., Lai Y.C., Chang K.Y., Chen Y.F., Hwang S.Y., Lo H.F. Improving breeding efficiency for quality and yield of sweet potato. Bot. Stud. 2007;48:283–292. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Dawson W., Prati D., Haeuser E., Feng Y., van Kleunen M. Does greater specific leaf area plasticity help plants to maintain a high performance when shaded? Ann. Bot. 2016;118:1329–1336. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludivik B., Hanefeld M., Pacini M. Improved metabolic control by Ipomoea batatas (Caiapo) is associated with increased adiponectin and decreased fibrinogen levels in type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2008;10:586–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekonen B., Tulu S., Nego J. Orange fleshed sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) varieties evaluated with respect to growth parameters at Jimma in Southwestern Ethiopia. J. Agron. 2015;14:164–169. doi: 10.3923/ja.2015.164.169. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre A.M., Karthik S., Liu H., Yang D., Martins F.R., Pereira E.B., Rüther R., Reindl T., Peters I.M. On the impact of haze on the yield of photovoltaic systems in Singapore. Renew. Energy. 2016;89:389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2015.11.079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nwinyi S.C.O. Effect of age at short removal on tuber and shoot yields at harvest of five sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas (L) Lam) cultivars. Field Crops Res. 1992;29:47–54. doi: 10.1016/0378-4290(92)90075-K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald A., Alkäumper J., Midmore D.J. The effect of different shade levels on growth and tuber yield of sweet potato: I. Plant development. J. Agro. Crop Sci. 1994;173:41–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-037X.1994.tb00572.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pogson B.J., Rissler H.M., Frank H.A. The roles of carotenoids in photosystem II of higher plants. In: Wydrzynski T., Satoh K., editors. Photosystem II: the Light-Driven Water: Plastoquinone Oxidoreductase. Springer-Verlag; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2005. pp. 515–537. [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H., Niklas K.J., Reich P.B., Oleksyn J., Poot P., Mommer L. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 2012;193:30–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter L., Castilho C.V., Schietti J., Oliveira R.S., Costa F.R.C. Can traits predict individual growth performance? A test in a hyperdiverse tropical forest. New Phytol. 2018;219:109–121. doi: 10.1111/nph.15206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin A.J., McAusland L., Headland L.R., Lawson T., Raines C.A. Multigene manipulation of photosynthetic carbon assimilation increases CO2 fixation and biomass yield in tobacco. J. Exp. Bot. 2015;66:4075–4090. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin A.J., López-Calcagno P.E., Raines C.A. Feeding the world: improving photosynthetic efficiency for sustainable crop production. J. Exp. Bot. 2019;70:1119–1140. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ery445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tay S., He J., Yam T.W. CAM plasticity in epiphytic tropical orchid species responding to environmental stress. Bot. Stud. 2019;60:7. doi: 10.1186/s40529-019-0255-0. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I., Hanba Y.T., Tazoe Y., Vyas P., Yano S. Irradiance and phenotype: comparative eco-development of sun and shade leaves in relation to photosynthetic CO2 diffusion. J. Exp. Bot. 2006;57:343–354. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikkanen M., Grieco M., Nurmi M., Rantala M., Suorsa M., Aro E.M. Regulation of the photosynthetic apparatus under fluctuating growth light. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2012;367:3486–3493. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timm S., Florian A., Arrivault S., Stitt M., Fernie A.R. Glycine decarboxylase controls photosynthesis and plant growth. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:3692–3697. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vialet-Chabrand, Matthews J.S.A., Simkin A.J., Raines C.A., Lawson T. Importance of fluctuations in light on plant photosynthetic acclimation. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:2163–2179. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Lu W., Tong Y., Yang Q. Leaf morphology, photosynthetic performance, chlorophyll fluorescence, stomatal development of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) exposed to different ratios of red light to blue light. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:250. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellburn A.R. The spectral determination of chlorophylls a and b, as well as carotenoids, using various solvents with spectrophotometers of different resolution. J. Plant Physiol. 1994;144:307–313. doi: 10.1016/s0176-1617(11)81192-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamasaki T., Yamakawa T., Yamane Y., Koike H., Satoh K., Katoh S. Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis and related changes in photosystem II electron transport in winter wheat. Plant Physiol. 2002;128:1087–1097. doi: 10.1104/pp.010919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W., Evans J.R., Von Caemmerer S. Effects of growth and measurement light intensities on temperature dependence of CO2 assimilation rate in tobacco leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33:332–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F., Feng L., Liu Q., Wu X., Fan Y., Ali Raza M. Effect of interactions between light intensity and red-to- far-red ratio on the photosynthesis of soybean leaves under shade condition. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018;150:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yooyongwecha S., Theerawitayab C., Samphumphuangb T., Chaumb S. Water-deficit tolerant identification in sweet potato genotypes (Ipomoea batatas (L.) Lam.) in vegetative developmental stage using multivariate physiological indices. Sci. Hortic. 2013;162:242–251. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2013.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimoto M., Yahara S., Okuno S., Islam M.S., Ishiguro K., Yamakawa O. Antimutagenecity of mono-, di-, and tricaffeoylquinic acid derivatives isolated from sweet potato (Impomoae batatas L) leaf. Biosci. Biotech. Biochem. 2002;66:2336–2341. doi: 10.1271/bbb.66.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Yu T., Ma W., Tian C., Sha Z., Li J. Morphological and physiological response of Acer catalpifolium Rehd. Seedlings to water and light stresses. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019;19 doi: 10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H., Zeng L.D., Yi X.P., Peng C.L., Zhang W.F., Chow W.S. The half-life of the cytochrome bf complex in leaves of pea plants after transfer from moderately-high growth light to low light. Funct. Plant Biol. 2017;44:351–357. doi: 10.1071/FP16222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivcak M., Brestic M., Kalaji H.M., Govindjee Photosynthetic responses of sun- and shade-grown barley leaves to high light: is the lower PSII connectivity in shade leaves associated with protection against excess of light? Photosynth. Res. 2014;119:339–354. doi: 10.1007/s11120-014-9969-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.