Abstract

In this study the thermal cyclotrimerization reactions of fluoro- and chloroacetylenes involving regioselectively stepwise {2 + 2} and stepwise {4 + 2} cycloadditions were studied using the topological analysis of the electron localization function (ELF), the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAIM) and natural bond orbital (NBO) analyses. These methodologies have shown that the electronic reorganization in the regioselectively stepwise {2 + 2} and stepwise {4 + 2} cycloadditions may be considered as {2n+2n} and {2π+2n} pseudodiradical process, respectively. Finally, the last phase of this thermal reaction can be understood as an electronic migration process under the pseudodiradical character in the thermal ring-opening reaction, with the subsequent formation of reaction products. In this sense, new insights are reported on the electronic behavior in the bond formation in the thermal cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene.

Keywords: Materials chemistry, Theoretical chemistry, Cyclotrimerization reactions: fluoro- and chloroacetylenes, Electron localization function (ELF), QTAIM, NBO analysis, {2 + 2}, {4 + 2} cycloadditions, {2n+2n} and {2π+2n} pseudodiradical process, Density functional theory (DFT)

Materials chemistry, Theoretical chemistry, Cyclotrimerization reactions: fluoro- and chloroacetylenes, Electron localization function (ELF), QTAIM, NBO analysis, {2 + 2}, {4 + 2} cycloadditions, {2n+2n} and {2π+2n} pseudodiradical process, Density functional theory (DFT).

1. Introduction

It is virtually impossible to understand the chemistry of alkyne cyclotrimerization without the structural and electronic theory of chemical bonding and knowledge of the chemical bonds formed and broken during chemical reactions [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]. However, the fundamental details of these rearrangements are a subject under discussion. Therefore, there are many questions remaining to be answered. For this reason, this study presents the little-studied thermal cyclotrimerization reactions of alkynes without a catalyst to give benzene [10, 11, 12, 13]. The discovery of the first uncatalyzed thermal cyclotrimerization of acetylene was approximately 80 years ago [4, 14]. In 1866, Berthelot reported the first example of the thermal transformation of acetylene to benzene. The reaction was conducted at 400 °C, giving a complex mixture of products [14].

Studies of the different phases at atomic level of the chemical reagents and the initial constituents exploring bond patterns are essential for the understanding at physicochemical atomic scale [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. The nature of the chemical bond has been studied by Silvi and co-workers through the bond evolution theory as a generalization of the Bader's work and other scalar fields associated to the electron localization function (ELF) [27, 28]. Using such studies has led to the postulation of electronic reorganizations through a pseudodiradical character and not the pericyclic reorganization postulated by Woodward-Hoffmann (WH) [29, 30] and showing to the Diels-Alder reactions as {2n + 2π} pseudodiradical cycloadditions [31, 32]. Moreover, in recent years our research group has studied electron reorganization using the ELF context, getting similar results about the pseudodiradical character [33a)]. Additionally, we used the quantum theory of atoms in molecules (QTAM), natural bond orbital frameworks, and electronic structure principles such as maximum hardness, minimum electrophilicity and minimum polarizability to seek new insights into the electronic reorganization process according to experimental data [(33c-d)].

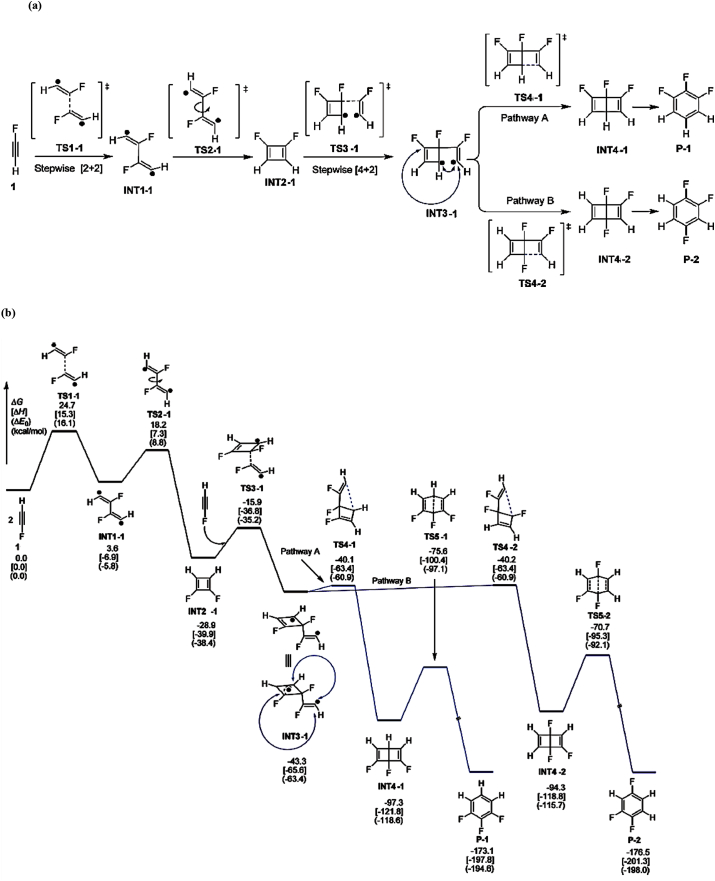

In the traditional WH rules, the {2 + 2} cycloaddition is a four-electron process that brings together two components. It is only allowed if the reaction is antarafacial with respect to exactly one component [29, 30]. This fact is taken into account to understand the cyclometrization in this study. In addition, fluoroacetylene derivatives are known to be highly reactive (sometimes explosive) and difficult to handle. In Figure 1, we can see the alkyne cyclotrimerization reported by Yao et al. [34].

Figure 1.

Mechanism of the cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene reported by Yao et al. [34].

Figure 1 shows the thermal cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene through {2 + 2} and {4 + 2} cycloaddition to produce the reaction products P-1 and P-2. The reaction will be studied to understand the electronic nature of its molecular arrangement and to determine the electronic considerations in which the electronic reorganization takes place (electronic stages). Based on these developments, we will focus on the interpretation of WH rules in the thermal cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene using the ELF, NBO analysis, and QTAIM framework. The ELF and NBO analysis will provide quantitative and qualitative information about the bond structure and the lone pairs. Finally, to obtain more quantitative information about the bond structure from a molecular point of view, we will use QTAIM analysis (the use of these methodologies is explained in detail in the following section.).

2. Computational details

The ELF was originally introduced by Becke and Edgecombe et al. [38] as a simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. The main feature of this formalism is that ELF represents a property of the same-spin pair probability density, this probability Pcond(r,s) was associated by Bader and coworkers with the spherically averaged conditional using the Taylor expansion as:

| (1) |

The expression in brackets is a proportionality factor for the mobility function in the Fermi Hole according to Luken et al. [39] and is related to the curvature at the position (r) as was demonstrated by Dobson et al. [40, 41].

The quantitative analysis performed by the integration of the electronic population of the basin (Ni) is:

| (2) |

In this sense, the Pauli repulsion principle between two electrons with the same spin may be described as the decrease in the D(r) term and is taken as a measure of the electron localization as:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where

| (5) |

Eq. (5) is for a uniform electron gas under the Fermi-Dirac statistics. Using this definition, the ELF may be defined in the interval (0, 1). In the topological interpretation of the ELF, a value close to 1 shows that the position of the same-spin electrons is more localized in the homogeneous electron gas and η(r) = 1/2 indicates that the Pauli effect in the studied system is equal to the homogeneous electron gas. This topological interpretation of the ELF is not ambiguous because the electron density gradient in an atom or molecule differs from zero in every location.

In the ELF framework, a core basin called A is written as V1 (A), a dysinaptic basin between two core basins A and B is denoted as V2 (A,B), and so on. In simple molecules, the monosynaptic basins can be related to “lone pairs” [42].

Natural bond orbitals (NBOs) [43] are orbitals with few localized centers ("few" typically means 1 or 2, but occasionally more) that describe the Lewis structure of electron pairs. NBOs are a set of localized molecular orbitals whose principal N/2 members provide the most accurate possible description of Lewis-like electron density. If we consider a closed shell determinant:

| (6) |

electronic density will be written as:

| (7) |

If are the canonical molecular orbitals. When the orbitals are natural bond orbitals (orthonormal orbitals) we obtain:

| (8) |

where the parameters are the NBO partial occupancies. This made it possible to study the contribution of each localized orbital to the electronic density of the molecule.

The donor-acceptor interactions [43] have been analysed via a second order perturbation theory. The delocalization energy E(2) related with donor NBO (i) → acceptor NBO (j) has been estimated as:

| (9) |

where qi is the occupancy of the i orbital, εi and εj are the energies of the orbitals i and j, and F(i,j) is the Fock matrix element. The results from these interactions can be considered corrections to the Lewis structure.

The NBO analysis provides qualitative information about the bond structure and lone pairs which is easy to interpret and allows comparisons between the transition states. To obtain a quantitative description of the molecular bond structure, we used the QTAIM analysis [44, 45, 46] and in particular ellipticity (calculated in the BCPs), which is the most appropriate parameter in this context. Ellipticities of electron density were defined as:

| (10) |

where and are eigenvalues of Hessian matrix of the density (the lowest and the second lowest). At a BCP, these parameters determine the curvature (perpendicular to the bond) of electron density.

The calculations of this study were performed with GAUSSIAN 09 program [47]. The structures were optimized using B3LYP functional (DFT exchange-correlation method) [48, 49] and the 6-31+G(d,p) basis set [50]. Frequency calculations have been performed in order to verify that the TSs have only one imaginary frequency. The intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) [19] paths were obtained to study the energy profiles that connect each TS to the two corresponding minima with the step of 0.1 [amu1/2 bohr]. ELF η(r) topological analysis [35] was performed with the TopMod program package [51, 52, 53] and a cubic grid distance between points of 0.1 bohr.

The QTAIM analysis was performed using the AIMAll program (http://aim.tkgristmill.com/index.html). The natural bond orbital analysis and the second order perturbation theory analysis were performed with the software NBO 3.0. [54], and the orbital images have been obtained with GaussView program [55].

3. Result and discussions

Recent studies have indicated that ELF analysis along the reaction path related with electrocyclic reactions is an excellent tool for determining the bond structure in the reaction process [33a),56,57]. In this contex, the valence basin populations of diverse geometries along the IRC have been obtained from the structure 1 to the INT3-1 (see Figure 2); Table 1 shows this electronic population. The numeration in Table 1 is from TS1-1 to INT2-1 and from TS3-1 to INT3-1, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Mechanism of the thermal cyclotrimerization reactions of fluoro- and chloroacetylenes. (b) Thermodynamic parameters: ΔG, ΔH, ΔE0(kcal/mol) profiles along the IRC, reported by Yao et al. using DFT calculations [34]. Note: Yao et al. [34]. proposed this mechanism using open shell calculations (UB3LYP/6-31G(d) level). However, in this study, these intermediates were re-calculated using close shell calculations (B3LYP/6-31+G(d,p) level).

Table 1.

ELF basin population of selected points from 1 to INT3-1 of the cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene.

| Basin | 1 | TS1-1 | INT1-1 | TS2-1 | INT2-1 | TS3-1 | INT3-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V(C1,C2) | 1.84 | - | 1.93 | 1.92 | 1.94 | 3.12 | 2.24 |

| V′(C1,C2) | 1.84 | - | - | - | 1.96 | - | - |

| V″(C1,C2) | 1.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| V(C1,C3) | - | 2.62 | 2.32 | 2.37 | - | 1.99 | 2.21 |

| V′(C1,C3) | - | 2.61 | 2.29 | 2.27 | - | - | - |

| V(C1,C5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.16 |

| V(C5,C6) | - | - | - | - | - | 2.43 | 1.53 |

| V′(C5,C6) | - | - | - | - | - | 2.50 | 2.08 |

| V(C2,C4) | - | 2.63 | 2.32 | 2.35 | - | 2.16 | 2.56 |

| V′(C2,C4) | - | 2.59 | 2.28 | 2.25 | - | - | - |

| V(C3,C4) | - | - | - | - | 1.94 | 1.79 | 3.12 |

| V′(C3,C4) | - | - | - | - | 1.96 | 1.97 | - |

| V(C1) | - | 0.56 | - | - | - | - | - |

| V(C2) | - | 0.55 | - | - | - | 0.63 | - |

| V(C3) | - | - | 0.26 | 0.23 | - | - | - |

| V(C4) | - | - | 0.26 | 0.26 | - | - | - |

| V(C6) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.63 | 1.84 |

Table 1 shows the first phase of the reaction shown in Figure 2, the {2 + 2} cycloaddition involved reagent 1 from three V(C1,C2): 1.84e, V′(C1,C2): 1.84e and V″(C1,C2): 1.85e basins, respectively. These electronic populations show the electronic nature of the triple bond. After this stage, we can see the {2n+2n} diradical cycloaddition forming the disynaptic V(C1,C3), V′(C1,C3) basins integrated for 2.62e and 2.61e, respectively. The V(C2,C4): 2.63e and V′(C2,C4): 2.59e basins show the first pseudodiradical state with the V(C1): 0.56e and V(C2):0.55e basins. The stage of INT1-1 has the basin V(C1,C2):1.93e and the double bonds are formed by the V(C1,C3):2.32e, V′(C1,C3):2.29e and V(C2,C4):2.32e, V′(C2,C4):2.28e basins respectively. The second pseudodiradical character is formed by the V(C3):0.26 and V(C4):0.26 basins. The TS2-1 retains the pseudodiradical character formed with a slight decrease in the V(C3) basin integrating to 0.23, and V(C4) maintains its electronic population with 0.26e. In INT2-1 phase, this pseudodiradical character disappears to form the double bonds in 1,2 difluoro-butadiene. In fact, it is shown by the symmetric electronic populations V(C1,C2):1.94e, V′(C1,C2):1.96e, V(C3,C4): 1.94e and V′(C3,C4):1.96e, respectively.

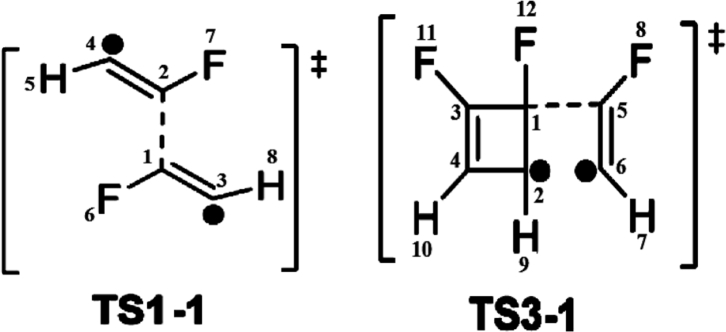

In the TS3-1 phase, the {2n+2π} cycloaddition reaction takes place producing the formation of the V(C1,C2): 3.12e and V(C1,C3): 1.99e basins for the single bonds, while the double bonds are evidenced by the presence of the V(C5,C6):2.43e, V′(C5,C6):2.50e, V(C3,C4):1.79e, and V′(C3,C4):1.97e basins. In this phase the pseudodiradical character is shown in the V(C2) and V(C6) basins, both integrated to 0.63e. Finally, in the INT3-1 phase, we can see the formation of the new V(C1,C5) basin integrated to 2.16e and the disappearance of pseudodiradical character to form the resonant system between the atoms (C3, C2 and C4); this system involves the V(C3,C4): 3.12e and a single basin of pseudodiradical character, V(C6):1.84e (see Figure 3). Figure 3 shows two reaction paths starting from INT3-1 and for the pathway A. The labels in the basins is with respect to TS3-1, while Table 2 shows the summary of the NBO energy diagram.

Figure 3.

Lewis structure and ELF picture for the resonant system formed by the C2, C3 and C4 atoms for the pseudodiradical character in the C6 atom in the INT3-1 state; the image corresponds to the isosurface 0.8599.

Table 2.

Summary of the NBO energy diagram for state INT3-1.

| NBO | Occupancy | Energy | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 0.09164 | 0.05260 | BD C5–C6 |

| 35 | 0.20784 | -0.04300 | BD C3–C4 |

| 34 | 0.37442 | -0.15980 | BD C2–C6 |

| 33 | 1.69159 | -0.16480 | BD C2–C6 |

| 32 | 1.94951 | -0.28540 | BD C5–C6 |

| 31 | 1.64568 | -0.32730 | BD C3–C4 |

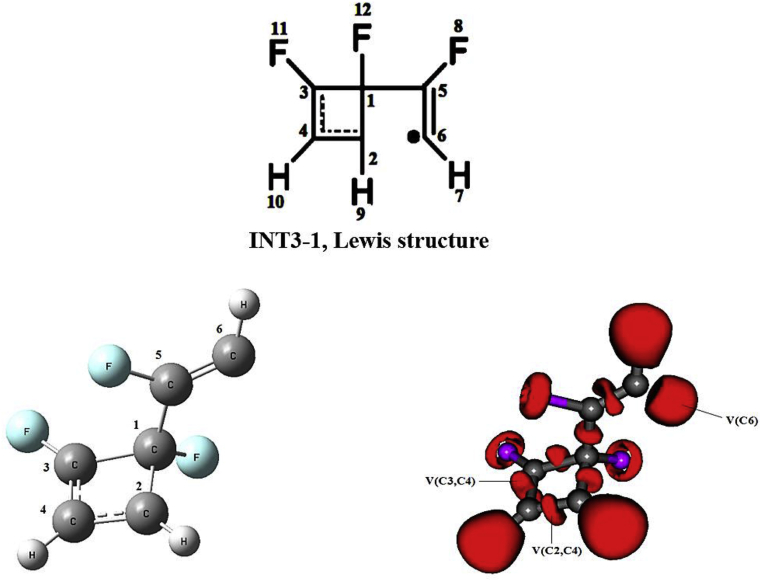

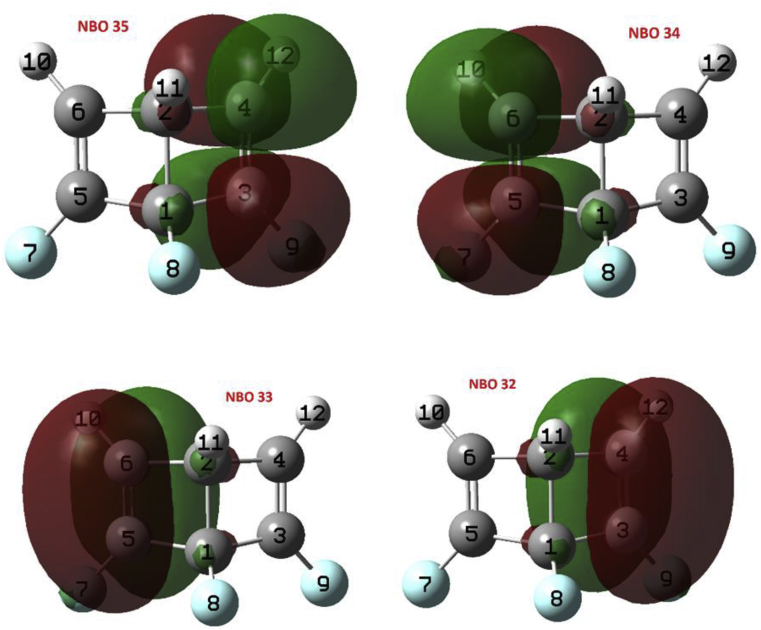

From the NBO analysis for INT3-1 state, the energy diagram of the NBOs was obtained (see Table 2). The π-bonding orbitals 33 (BD C2–C6) and π-antibonding 34 (BD C2–C6) correspond to the pseudodiradical in the C6 atom that can also be seen in Figure 3. Figure 4 shows the characteristic shape of the NBOs 33 and 34. The second order perturbation theory analysis shows that the most important interactions by delocalization correspond to donations NBO 31 - > NBO 34 (E(2) = 45.42 kcal/mol), NBO 33 - > NBO 35 (E(2) = 33.04 kcal/mol) and NBO 34 - > NBO 35 (E(2) = 12.84 kcal/mol) corresponding to the resonant system formed by the C2, C3 and C4 atoms, which was also described in the ELF analysis.

Figure 4.

Images of NBOs 31–35 of state INT3-1.

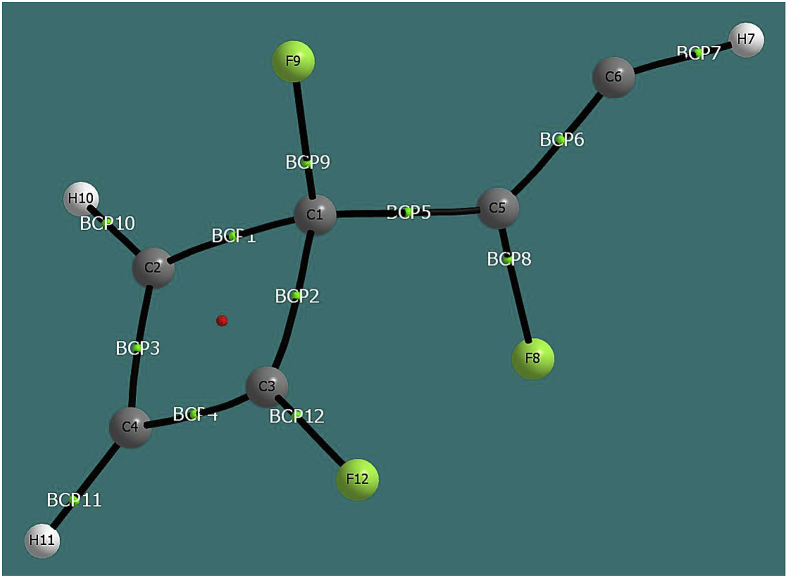

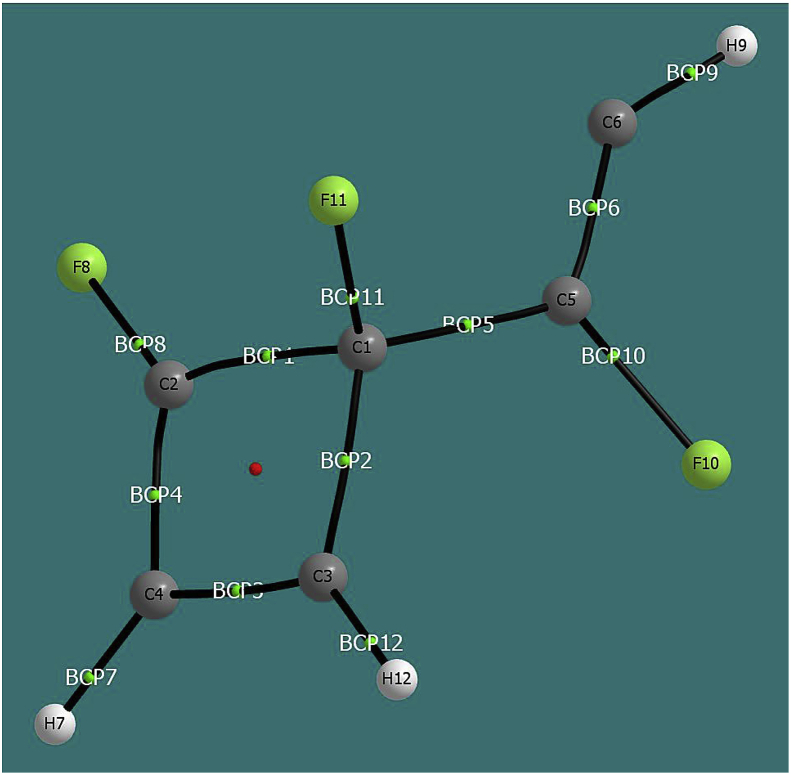

The QTAIM analysis was been performed on the INT3-1 state, and the ellipticities were calculated in the bond critical points (BCP, see Figure 5). The values obtained were ε(BCP1, C1–C2) = 0.067 (characteristic value of a single bond), ε(BCP2, C1–C3) = 0.031 (single bond), ε (BCP3, C2–C4) = 0.174 (single-double intermediate bond), ε(BCP4 C3–C4) = 0.310 (double bond), ε(BCP5; C1–C5) = 0.158 (single-double intermediate bond), ε(BCP6; C5–C6) = 0.325 (double bond). The description of the resonant system formed by the C2, C3 and C4 atoms is consistent with the interactions by delocalization obtained in the second order perturbational analysis and with the results obtained from the ELF analysis.

Figure 5.

Bond critical points obtained from QTAIM analysis for state INT3-1.

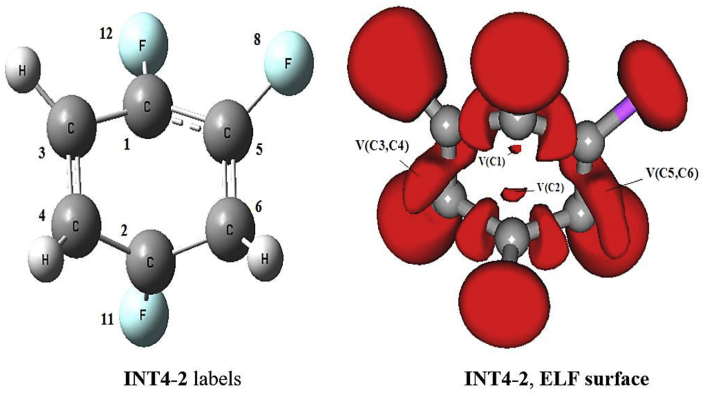

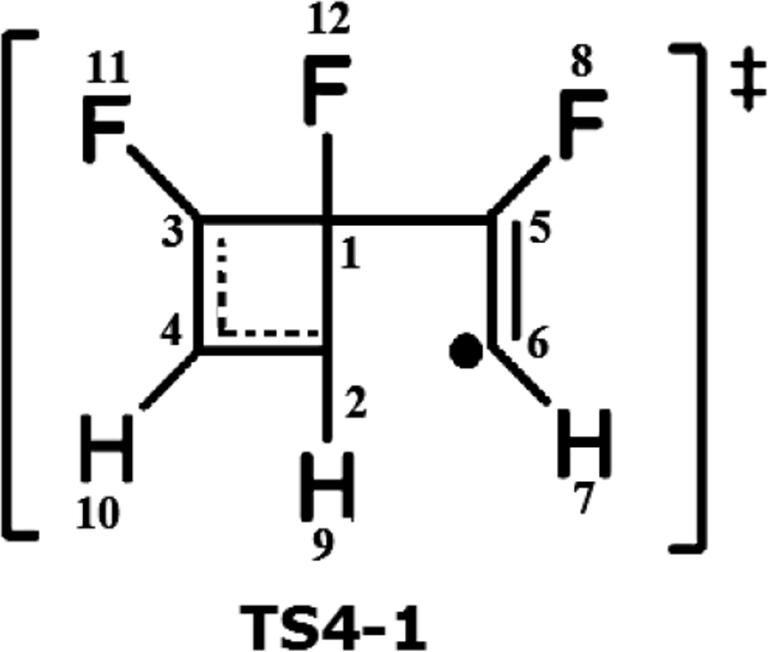

Table 3 shows the basins corresponding to pathway A of the cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene, the electronic population of the state TS4-1 associated with the resonant system (C2, C3 and C4) through the V(C3,C4): 2.64e, V(C2,C4):3.07e basins, and the electronic population associated with the pseudodiradical character shown by the V(C6):1.87e basin. In the INT4-1 phase, it shows the disappearance of the pseudodiradical character V(C6) to form the double bond between the C3–C4 carbon atoms formed by the V(C3,C4): 1.92e and V′(C3,C4): 1.83e basins, respectively.

Table 3.

ELF basin population of selected points from TS4-1 to P-1 of the pathway A on the cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene.

| Basin | TS4-1 | INT4-1 | P-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| V(C1,C2) | 1.99 | 1.77 | - |

| V(C1,C3) | 2.47 | 1.98 | 3.15 |

| V(C1,C5) | 2.15 | 1.91 | 2.97 |

| V(C5,C6) | 2.04 | 1.92 | 2.93 |

| V′(C5,C6) | 1.58 | 1.83 | - |

| V(C2,C4) | 3.07 | 2.28 | 3.01 |

| V(C2,C6) | - | 2.20 | 2.85 |

| V(C3,C4) | 2.64 | 1.92 | 2.93 |

| V′(C3,C4) | - | 1.83 | - |

| V(C6) | 1.87 | - | - |

Finally, in the phase corresponding to product 1 (P-1), it is possible to demonstrate the disappearance of the monosynaptic basin V(C1,C2) and the resonant system formation between the atoms (C1 to C6) determined by the disynaptic V(C1,C3): 3.15e, V(C1,C5):2.97e, V(C5,C6):2.93e, V(C2,C4):3.01e, V(C2,C6):2.85e and V(C3,C4):2.93e basins, respectively. Figure 6 shows a migration reaction through an atom migration of fluorine 11 in the resonant system (C2, C3 and C4) from the carbon atom 3 to the position of carbon atom 2 to produce the corresponding product 2 (P-2) in pathway B.

Figure 6.

ELF picture of the system formed of atoms C2, C3 and C4 on the pseudodiradical character in the C6 atom of the TS4-1 state, corresponding to the isosurface 0,8599.

In this aromatic system, an electronic migration on the carbon atoms 3, 4 and 2 may be related to regions with small fluctuations in the quantum uncertainty, according to Savin et al [57]. It interpretation of the basins for such systems shows the pseudodiradical character in the migration reactions.

Table 4 shows a summary of the NBO energy diagram for state TS4-1. The π-bonding 34 (BD C2–C6) and π-antibonding 33 (BD C2–C6) orbitals correspond to the pseudodiradical in the C6 atom (see Figure 7). The second order perturbation theory analysis shows that the most important interactions by delocalization correspond to donations NBO 34 - > NBO 35 (E(2) = 33.45 kcal/mol), NBO 31 - > NBO 33 (E(2) = 60.39 kcal/mol) and NBO 33 - > NBO 35 (E(2) = 14.11 kcal/mol), which correspond to the resonant system formed by the C2, C3 and C4 atoms that were also observed in the ELF analysis.

Table 4.

Summary of the NBO energy diagram for state TS4-1.

| NBO | Occupancy | Energy | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 42 | 0.07961 | 0.36250 | BD C1–C5 |

| 41 | 0.03691 | 0.29790 | BD C1–C3 |

| 40 | 0.06327 | 0.29500 | BD C1–C2 |

| 39 | 0.14706 | 0.24050 | BD C5–F7 |

| 38 | 0.05068 | 0.21620 | BD C2–F9 |

| 37 | 0.08404 | 0.19040 | BD C1–F8 |

| 36 | 0.08452 | 0.05600 | BD C5–C6 |

| 35 | 0.19908 | -0.04300 | BD C3–C4 |

| 34 | 1.63899 | -0.17400 | BD C2–C6 |

| 33 | 0.46979 | -0.17460 | BD C2–C6 |

| 32 | 1.94095 | -0.28650 | BD C5–C6 |

| 31 | 1.63072 | -0.31700 | BD C3–C4 |

Figure 7.

Images of NBOs 31–36 of state TS4-1.

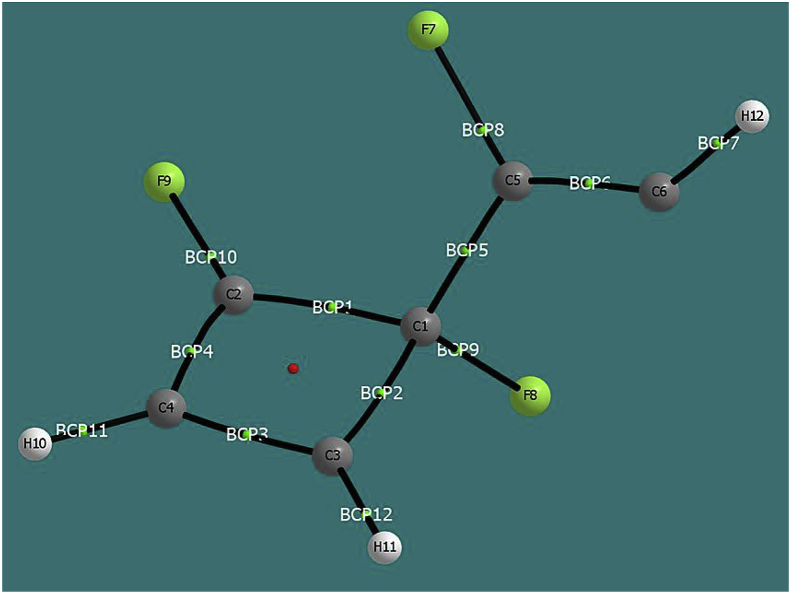

The QTAIM-based analysis of the TS4-1 state made it possible to obtain the following ellipticities in the BCPs shown in Figure 8: ε(BCP1; C1–C2) = 0.077 (value corresponding to approximately a single bond); ε(BCP2; C1 –C3) = 0.029 (single bond); ε(BCP3, C3–C4) = 0.221 (single-double intermediate bond); ε(BCP4 C2–C4) = 0.254 (single-double intermediate bond); ε(BCP5, C1–C5) = 0.079 (approximately simple bond); and ε(BCP6; C5–C6) = 0.316 (double bond). The results obtained are consistent with the interactions obtained in the second order perturbational analysis and the ELF analysis.

Figure 8.

Bond critical points obtained from QTAIM analysis for state TS4-1.

Table 5 shows an extract of the energy diagram of the NBOs obtained in the state analysis of INT4-1. The π-bonding 32 orbitals (BD C3–C4), π-bonding 33 (BD C5–C6), π-antibonding 34 (BD C5–C6) and π-antibonding 35 (BD C3–C4) correspond to double bonds of state INT4-1 (see Figure 9). The pseudiradical character disappeared and a double bond C3–C4 was formed. As seen in the ELF analysis.

Table 5.

Summary of the NBO energy diagram for state INT4-1.

| NBO | Occupancy | Energy | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | 0.10754 | 0.01500 | BD C3–C4 |

| 34 | 0.10754 | 0.01500 | BD C5–C6 |

| 33 | 1.93018 | -0.31500 | BD C5–C6 |

| 32 | 1.93018 | -0.31500 | BD C3–C4 |

Figure 9.

Images of NBOs 32–35 of state INT4-1.

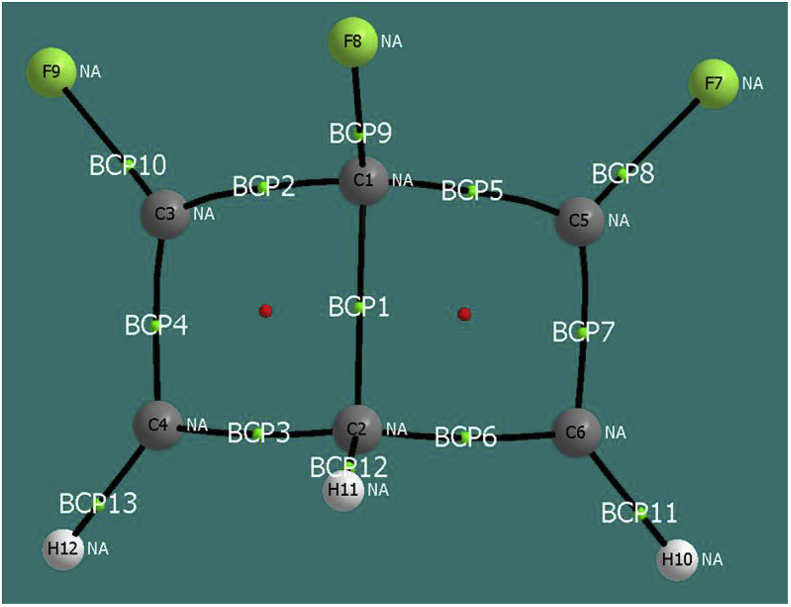

The QTAIM-based analysis of the INT4-1 state made it possible to calculate the ellipticities in the following BCPs shown in Figure 10: ε(BCP1; C1–C2) = 0.024 (this value approximately corresponds to a single bond); ε(BCP2; C1– C3) = 0.079 (single bond); ε(BCP3, C2–C4) = 0.023 (single bond); ε(BCP4 C3–C4) = 0.477 (double bond); ε(BCP5; C1–C5) = 0.079 (simple bond); ε(BCP6, C2–C6) = 0.023 (single bond); and ε(BCP7; C5–C6) = 0.477 (double bond). The results obtained are consistent with the ELF and NBO analyses, the pseudiradical character disappeared and a double bond C3–C4 was formed.

Figure 10.

Bond critical points obtained from QTAIM analysis for state INT4-1.

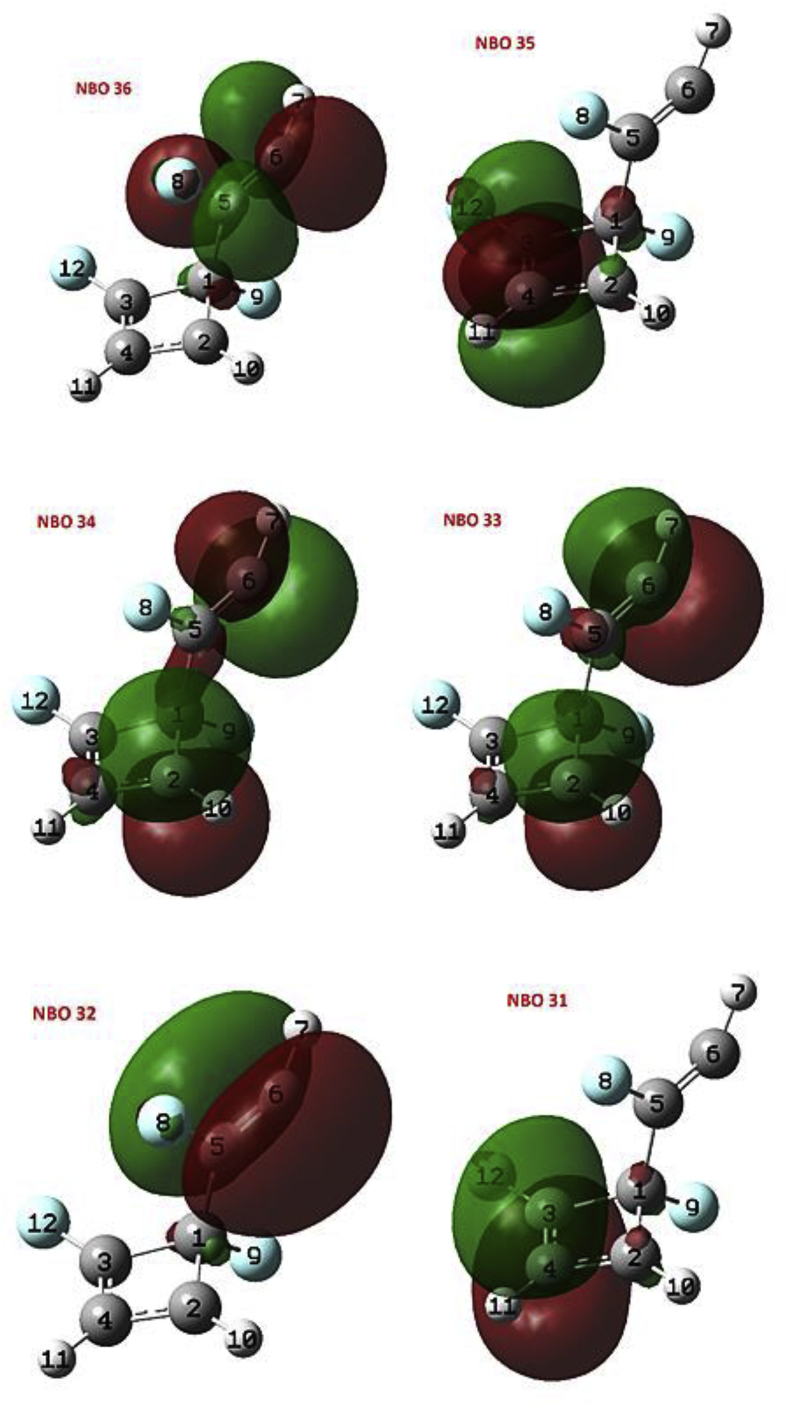

Table 6 shows a summary of the energy diagram of the NBOs obtained in the TS4-2 state. The π-bonding 33 (BD C3–C6) and π-antibonding 34 (BD C3–C6) orbitals correspond to the pseudodiradical in the C6 atom (see Figure 11). The second order perturbation theory analysis shows that the most important interactions by delocalization correspond to donations NBO 31 - > NBO 34 (E(2) = 46.13 kcal/mol) and NBO 33 - > NBO 35 (E(2) = 32.36 kcal/mol) corresponding to the resonant system formed by the C2, C3 and C4 atoms, which is consistent with the results of the ELF analysis (Table 7).

Table 6.

Summary of the NBO energy diagram for state TS4-2.

| NBO | Occupancy | Energy | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| 36 | 0.07980 | 0.05540 | BD C5–C6 |

| 35 | 0.23011 | -0.04470 | BD C2–C4 |

| 34 | 0.39391 | -0.15980 | BD C3–C6 |

| 33 | 1.68822 | -0.16490 | BD C3–C6 |

| 32 | 1.94482 | -0.28620 | BD C5–C6 |

| 31 | 1.62090 | -0.32980 | BD C2–C4 |

Figure 11.

Images of NBOs 31–36 of state TS4-2.

Table 7.

ELF basin population of the selected points from TS4-2 to P-2 in the pathway A of the cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene.

| Basin | TS4-2 | INT4-2 | P-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| V(C1,C2) | 2.21 | - | - |

| V(C1,C3) | 2.24 | 2.30 | 2.97 |

| V(C1,C5) | 2.16 | 2.33 | 3.00 |

| V(C5,C6) | 1.54 | 2.10 | 3.02 |

| V′(C5,C6) | 2.08 | 1.62 | - |

| V(C2,C4) | 3.12 | 2.33 | 2.84 |

| V(C2,C6) | - | 2.61 | 2.98 |

| V(C3,C4) | 2.56 | 1.92 | 2.96 |

| V′(C3,C4) | - | 1.58 | - |

| V(C1) | - | 0.32 | - |

| V(C2) | 0.61 | - | |

| V(C6) | 1.83 | - | - |

The QTAIM-based analysis of the TS4-2 state has given us the following ellipticities in the BCPs (see Figure 12): ε(BCP1; C1–C2) = 0.039 (approximately corresponding to a single bond); ε(BCP2; C1–C3) = 0.052 (single bond); ε(BCP3, C3–C4) = 0.186 (double bond); ε(BCP4 C2–C4) = 0.296 (double bond); ε(BCP5; C1–C5) = 0.082 (single bond); and ε(BCP6; C5–C6) = 0.315 (double bond). The results obtained are coherent with the interactions by delocalisation obtained in the second order perturbational analysis and with the results obtained from the ELF analysis (Table 7).

Figure 12.

Bond critical points obtained from QTAIM analysis for state TS4-2.

In Figure 13, it is possible see the pseudodiradical character of the C1 and C2 carbon atoms subsides to form the resonant system shown in the product P-2, forming the V(C1,C3): 2.97e, V(C1,C5):3.00e, V(C5,C6):3.02e, V(C2,C4): 2.84e, V(C2,C6):2.98e and V(C3,C4):2.96e basins (Table 7).

Figure 13.

ELF image of the pseudodiradical character of the C1 and C2 carbon atoms in the state INT4-2, corresponding to the isosurface 0.7988.

In this sense, these Diels-Alder cycloadditions are characterized by a pseudodiradical character and not the pericyclic process reported by the traditional WH rules. The {2n + 2π} cycloaddition in the second phase (see Figure 1) can be considered stepwise pseudodiradical dimeric (closed shell) and not a cycloaddition through radicals (open shell). This allows us understand the electronic reorganization and their molecular behavior as pseudodiradical intermediates. Moreover, the three phases of the mechanisms that correspond to the electronic migration reactions reported in this study are due to the migration of a fluorine atom in the pseudodiradical resonant system (C3, C4 and C2), see Table 3. In this sense, the lone electron in the carbon atom C2 migrates to the carbon atom C3, with the subsequent formation of the intermediary TS4-2, also with pseudodiradical reorganization and not a pericyclic process.

4. Conclusions

This paper presents the study of the cyclotrimerization of fluoro- and chloroacetylenes involving {2 + 2} and {4 + 2} cycloadditions by means of ELF topological, QTAIM analyses and Natural Bond Orbital analyses. These three methodologies have shown that the electronic reorganization in the {2 + 2}, {4 + 2} cycloadditions can be considered as {2n +2n} and {2π+2n} pseudodiradical process, respectively. The last phase of this thermal reaction involved an electronic migration from the spin α of the carbon atom C2 to the carbon atom C3 under the pseudodiradical character, with the subsequent formation of the reaction products (P1 and P2). These outcomes are consistent with the thermodynamic analysis reported by Yao et al. [34] In this framework, new insights are presented in the electronic behavior in the formation of bonds in the thermal cyclotrimerization of fluoroacetylene, showing the electronic nature to be pseudodiradical and not purely diradical. All the calculations using a closed shell were performed.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Alejandro Morales-Bayuelo: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Jesús Sánchez-Márquez: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Alejandro Morales-Bayuelo was supported by UNISINU-2020 (2020-I).

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

A. M. B thanks to the Universidad del Sinú (grupo GIBACUS), seccional Cartagena.

References

- 1.McAlister D.R., Bercaw J.E., Bergman R.G. Parallel reaction pathways in the cobalt-catalyzed cyclotrimerization of acetylenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:1666. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vollhardt K.P.C. Transition-metal-catalyzed acetylene cyclizations in organic synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1977;10:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schore N.E. Transition metal-mediated cycloaddition reactions of alkynes in organic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:1081. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reppe W., Schlichting O., Klager K., Toepel T. Cyclisierende Polymerisation von Acetylen I Über Cyclooctatetraen. J Ann. Chem. 1948;560:1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao F., Schut D.M., Tyler D.R. Catalysis by 18 + δ compounds. Cyclooligomerization of acetylenes catalyzed by Co(CO)3L2 Organometallics. Organometallics. 1996;15:4770. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jhingan A.K., Maier W.F. Homogeneous catalysis with a heterogeneous palladium catalyst. An effective method for the cyclotrimerization of alkynes. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:1161. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gevorgyan V., Radhakrishnan U., Takeda A., Rubina M., Rubin M., Yamamoto Y. Palladium-catalyzed highly chemo- and regioselective formal [2 + 2 + 2] sequential cycloaddition of alkynes: a renaissance of the well known trimerization reaction? J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:2835. doi: 10.1021/jo0100392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kakeya M., Fujihara T., Kasaya T., Nagasawa A. Dinuclear niobium(III) complexes [{NbCl2(L)}2(μ-Cl)2(μ-L)] (L = tetrahydrothiophene, dimethyl sulfide): preparation, molecular structures, and the catalytic activity for the regioselective cyclotrimerization of alkynes. Organometallics. 2006;25:4131. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Orian L., van Stralen J.N.P., Bickelhaupt F.M. Cyclotrimerization reactions catalyzed by rRhodium(I) half-sandwich complexes: A mechanistic density functional study. Organometallics. 2007;26:3816. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viehe H.G., Mer-enyi D.-I.R., Oth J.F.M., Valange P. Formation of 1,2,3-tri-t-butyltrifluorobenzene by spontaneous trimerization of t-butylfluoroacetylene. Angew. Chem. 1964;3:746. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viehe H.G., Mer-enyi D.-I.R., Oth J.F.M., Senders J.R., Valange P. Valence-bond isomers of (substituted) benzene. Angew. Chem. 1964;3:755. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ballester M., Castaner J., Riera J., Tabernero I. Synthesis and chemical behavior of perchlorophenylacetylene. J. Org. Chem. 1986;51:1413. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hopf H., Witulski B. Cyanoalkynes: Magic wands for the preparation of novel aromatic compounds. Pure Appl. Chem. 1993;65:47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertholet M.C.R. Acetylene thermally cyclotrimerizes to benzene. Seances Acad. Sci. 1866;905:7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry R.S., Ricc S.A., Ross J. second ed. Oxford University Press; Oxford, U. K: 2000. Physical Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breslow R. Determining the geometries of transition states by use of antihydrophobic additives in water. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:471. doi: 10.1021/ar040001m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gessner O., Lee A.M.D., Shaffer J.P., Reister H., Levchenko S.V., Krylov A.I. Femtosecond multidimensional imaging of a molecular dissociation. Science. 2006;311:219. doi: 10.1126/science.1120779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutcliffe B.T. The idea of a potential energy surface. Mol. Phys. 2006;104:715. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fukui K. Formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 1970;74:4161. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mulliken R. Electronic population analysis on lcao–mo molecular wave functions. i. J. Chem. Phys. 1955;23:1833. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löwdin P.O. On the non-orthogonality problem connected with the use of atomic wave functions in the theory of molecules and crystals. J. Chem. Phys. 1950;18:365. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed A.E., Curtiss L.A. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:899. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bader R.F.W. Clarendron Press; Oxford: 1990. Atom in Molecules. A Quantum Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grimme S., Muck-Lichtenfeld C., Erker G., Kehr G., Wang H.D., Beeckers H., Willner H. When do interacting atoms form a chemical bond? Spectroscopic measurements and theoretical analyses of dideuteriophenanthrene. Angew. Chem. 2009;48:2592. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becke A.D., Edgecombe K.E.A. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:5397. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savin A., Jepsen O., Flad J., Andersen O.K., Preuss H., Von Schnering H.G. Electron localization in solid-state structures of the elements: the diamond structure. Angew. Chem. 1992;31:187. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krokidis X., Vuilleumier R., Borgis D., Silvi B. A topological analysis of the proton transfer in H5O+2. Mol. Phys. 1999;96:265. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li X.Y., Zeng Y.L., Meng L.P., Zheng S.J. Topological characterization of HXO2 (X = Cl, Br, I) isomerization. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2007;111:1530. doi: 10.1021/jp067526b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berski S., Andrés J., Silvi B., Domingo L. The joint use of catastrophe theory and electron localization function to characterize molecular mechanisms. a density functional study of the diels−alder reaction between ethylene and 1,3-butadiene. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:6014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domingo L., Aurell J.M., Pérez P., Contreras R. Origin of the synchronicity on the transition structures of polar diels−Alder Reactions. Are These Reactions [4 + 2] processes? J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:3884. doi: 10.1021/jo020714n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houk K., González J., Li Y. Pericyclic reaction transition states: passions and punctilios. Acc. Chem. Res. 1995;28:81. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Woodward R.B., Hoffmann R. The conservation of orbital symmetry. Angew. Chem. 1969;8:781. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fukui K. The role of frontier orbitals in chemical reactions. Angew. Chem. 1982;21:801. doi: 10.1126/science.218.4574.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.(a) Morales-Bayuelo A. Understanding the electronic reorganization in the thermal isomerization reaction of trans-3,4-dimethylcyclobutene. Origins of outward Pseudodiradical {2n + 2π} torquoselectivity. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 2013;113:1534. [Google Scholar]; (b) Morales-Bayuelo A., Pan S., Caballero J., Chattaraj P.K. Analyzing torquoselectivity in electrocyclic ring opening reactions of trans-3,4-dimethylcyclobutene and 3-formylcyclobutene through electronic structure principles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015;17:23104. doi: 10.1039/c5cp02647d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guo H., Morales-Bayuelo A., Xu T., Momen R., Wang L., Yang P., Kirk S.R., Samantha Jenkins S. Predicting competitive and non-competitive torquoselectivity in ring-opening reactions using QTAIM and the stress tensor. J. Comp. Chem. 2016;37:2722. doi: 10.1002/jcc.24499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Morales-Bayuelo A., Sánchez-Márquez J., Jana G., Chattaraj P.K. A conceptual DFT analysis of the plausible mechanism of some pericyclic reactions. Struct. Chem. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yao Z., Yu Z. Mechanisms of the thermal cyclotrimerizations of fluoro- and chloroacetylenes: density functional theory investigation and intermediate trapping experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:10864. doi: 10.1021/ja2021476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Ostlund N.S., Szabo A. Macmillan; 1982. Modern Quantum Chemistry: Introduction to Advanced Electronic Structure Theory. [Google Scholar]; (b) Horn A.H. Essentials of Computational Chemistry, Theories and Models by Christopher J. Cramer. Wiley: Chichester, England. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2003;43(1) 2002. 562 pp. 20-1720. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sommerfeld T. Lorentz trial function for the hydrogen atom: a simple, elegant exercise. J. Chem. Ed. 2011;88:1521–1524. [Google Scholar]; (d) Becke A.D., Edgecombe K.E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990;92:5397. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luken W.L., Culberson J.C. Mobility of the fermi hole in a single-determinant wavefunction. Int. J. Quant. Chem. Symposium. 1982;16:265. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dobson J.F. Interpretation of the Fermi hole curvature. J. Chem. Phys. 1991;94:4328. [Google Scholar]

- 40.(a) Savin A., Becke A.D., Flad J., Nesper R., Preuss H., Von Schnering H.G.A. A new look at electron localization. Angew. Chem. 1991;30:409. [Google Scholar]; (b) Deb B.M., Gosh S.K. New method for the direct calculation of electron density in many-electron systems. I. Application to closed-shell atoms. Int. J. Quant. Chem. 1983;23:1. [Google Scholar]

- 41.(a) Thom R. Interédition; París: 1977. Stabilité structurelle et morphogénèse. [Google Scholar]; (b) Savin A., Silvi B., Colonna F. Topological analysis of the electron localization function applied to delocalized bonds. J. Chem-Revue Canadienne de chimie. 1996 Canadian;74:1088. [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacWeeny R. second ed. Academic Press; London: 1989. Methods of Molecular Quantum Mechanics. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reed A.E., Curtiss L.A., Weinhold F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988;88:899–926. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bader R.F.W. Oxford University Press; 1990. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matta C.F., Boyd R.J., editors. The Quantum Theory of Atoms in Molecules: from Solid State to DNA and Drug Design. WILEY-VCH; Weinham: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bader R.F.W. The quantum mechanical basis of conceptual chemistry. Monatschefte fur Chemie. 2005;136:819. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Frisch M.J., Trucks W G., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery J.A., Jr., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Keith T., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J.M., Klene M., Knox J.E., Cross J.B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas O., Foresman J.B., Ortiz J.V., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2010. GAUSSIAN 09 Revision C.01. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beeke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishnan R., Binkley J.S., Seeger R., Pople J.A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:650. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noury S., Krokidis X., Fuster F., Silvi B. Computational tools for the electron localization function topological analysis. Comput. Chem. 1999;23:597. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Matito E., Silvi B., Duran M., Solà M. Electron localization function at the correlated level. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;125 doi: 10.1063/1.2210473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feixas F., Matito E., Duran M., Solá M., Silvi B. Electron localization function at the correlated level: a natural orbital formulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:2736. doi: 10.1021/ct1003548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dennington R., Keith T.A., Millam J.M. Gaussian, Inc; Wallingford, CT: 2008. GaussView 5.0. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.(a) Carpenter J., Weinhold F. Analysis of the geometry of the hydroxymethyl radical by the “different hybrids for different spins” natural bond orbital procedure. J. mol. Struc. 1988;169:41–62. [Google Scholar]; (b) Glendening E., Badenhoop J., Reed A., Carpenter J., Bohmann J., Morales C., Weinhold F. University of Wisconsin; Madison, WI, USA: 2001. Theoretical Chemistry Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alajarín M., Ortín M.M., Sánchez-Andrada P., Vidal Á. Tandem pseudopericyclic reactions: [1,5]-X sigmatropic shift/6pi-electrocyclic ring closure converting N-(2-X-carbonyl)phenyl ketenimines into 2-X-quinolin-4(3H)-ones. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:8126. doi: 10.1021/jo061286e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savin A. Ruthenium-catalysed aerobic oxidation of alcohols via multistep electron transfer. J. Chem. Sci. 2005;117:473. [Google Scholar]