Abstract

Animal-assisted interventions (AAIs) can improve patients’ quality of life as complementary medical treatments. Part I of this 2-paper systematic review focused on the methods and results of cancer-related AAIs; Part II discusses the theories of the field’s investigators. Researchers cite animal personality, physical touch, physical movement, distraction, and increased human interaction as sources of observed positive outcomes. These mechanisms then group under theoretical frameworks such as the social support hypothesis or the human-animal bond concept to fully explain AAI in oncology. The cognitive activation theory of stress, the science of unitary human beings, and the self-object hypothesis are additional frameworks mentioned by some researchers. We also discuss concepts of neurobiological transduction connecting mechanisms to AAI benefits. Future researchers should base study design on theories with testable hypotheses and use consistent terminology to report results. This review aids progress toward a unified theoretical framework and toward more holistic cancer treatments.

Keywords: animal-assisted interventions, animal-assisted activities, animal-assisted therapy, oncology, cancer, human-animal bond, mechanisms, theoretical frameworks

Introduction

A cancer diagnosis presents a threat to a patient’s physical, psychological, and social well-being. Often, cancer patients experience deleterious health effects due to the significant stress of managing cancer and its treatments.1 This stress can lead to significant social isolation by affecting relationships with loved ones and medical staff.2,3 It also contributes to cancer-related symptoms, such as fatigue, which may negatively affect mood and, potentially, immune function.4,5 Providing a holistic treatment thus requires attending to the psychosocial aspects of cancer as well as the physical disease even though addressing these psychosocial aspects is complicated. For example, overt offers of assistance may hamper effective social support and threaten a patient’s self-esteem by forcing him or her to seem “helpless or dependent.”6,7 For pediatric populations, the physical and emotional harm caused by a cancer diagnosis increases a child’s “vulnerability to the development of psychological disorders, which may directly or indirectly affect their general clinical condition.”8 Complementary and alternative treatments offer potential solutions to meet these psychosocial needs. These treatments include medical products and practices that are not part of standard medical care but can still produce observable benefits for patients.9-11 Since 1961, researchers led by Boris Levinson began to explore the idea that certain positive interactions with domesticated animals can provide benefits to humans.12,13 Animal-assisted interactions (AAIs) make up a class of complementary medical treatments drawing on this concept, using sessions with animals to improve psychological and clinical outcomes. Researchers use AAI to ameliorate problems their subjects face while also investigating it as a broadly applicable treatment. In Part I of this systematic review series, we reviewed the literature on AAI in oncology with a special focus on study designs and quantitative results.14 Similar to the field limitations we highlighted in that article, several comprehensive and partial reviews have criticized the AAI field “for inadequate methodology, dubious analyses of results, and questionable conclusions.”15-17 While many issues for cancer-related AAI as a field stem from methodological and analytical inconsistencies, a general paucity of rigor in the theoretical underpinnings of these therapeutic interactions is also a significant hindrance to understanding what works during an interaction.18-20 This general problem extends to cancer-related AAI as well, and few research studies in this field propose testable hypotheses or are rooted in a theory of what may make AAI effective. This limits the value researchers can extract from their hard work or from results that are sometimes positive but often neutral.14 Overlooking theoretical considerations in the field of AAI perpetuates a lack of empirical evidence based on clear hypotheses and slows progress toward a general understanding of how best to employ this alternative treatment. Lexical inconsistencies further compound these problems when AAI is parsed into its subfields. Different definitions have been proffered in good faith, and many terms in the field (such as pet therapy or animal-facilitated therapy) have been used interchangeably despite calls for a more consistent use of terminology.19,21 However, it is generally understood that, under the broad umbrella of AAI, animal-assisted activities (AAAs) seek to improve patient quality of life broadly, while animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is targeted toward generating specific clinical outcomes (eg, lower blood pressure or reduced cancer-related fatigue).18,19,22-24 For the AAI studies lacking a solid theoretical basis, the meaningful distinction between AAA and AAT can often evaporate, becoming purely a matter of linguistic preference. Nevertheless, the research results laid out in Part I of this review series are still valid and useful moving forward.14 In the study by Haylock and Cantril,25 the authors note that they first use the qualitative methods available to determine the beneficial effects of cancer-related AAI. It then follows that, from this qualitative assessment, a theoretical framework can be extrapolated and its hypotheses tested both qualitatively and quantitatively. Thus, there are 2 research paths: starting with a testable hypothesis or extrapolating explanations after the fact. In either case, a “sound theoretical basis supported by scientifically measured physiological parameters is needed to gain medical support for animal-assisted therapy.”26 However, Hosey and Melfi,21 in their comprehensive review of the human-animal interaction field, noted that frameworks produced via either research path are often not concerned with theories outside of their own context even if certain themes can be seen throughout the field. This showed that there are several theories born of either research path that purport to explain the mechanisms and reasons why the human-animal bond is generally positive and why AAI may work in oncology. In this Part II of a 2-paper systematic literature review series, we discuss the theoretical frameworks and mechanisms directly invoked by the cancer-related AAI articles included in Part I, paying special attention to the theories authors provide to explain results. Our goals in exploring these and other explanations of the benefits of AAI are to further inform the discussion of the field’s results thus far and to aid progress toward a unified theoretical framework for animal-inclusive, holistic cancer treatments.

Systematic Review Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review focusing on various terms for both AAI (including animal facilitated interventions, pet therapy, or equine-assisted activities) and cancer (such as neoplasm or oncology). More details on the literature search methodology are provided in Part I of this systematic review. The full literature search gathered any document format up to July 31, 2018, by interrogating the PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, CAB abstracts, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and North Carolina State University, and University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill’s library databases. Full and partial readings of the results for specific relevance to our review’s topic sentence resulted in 32 relevant publications. In this context, relevance is defined as providing independent, novel data or summary information specifically dealing with the efficacy of AAI and its variants in oncology. The studies’ methods and results were summarized in Part I of this 2-paper series, and the discussed theoretical implications discussed by these 32 articles are summarized in this Part II review.14 A general survey of the AAI literature revealed other theories of interest not mentioned by articles included in this review of AAI in oncology, and these theories are also discussed in this article. A summary of the discussed theories’ postulates and the relevant cancer-related AAI articles are organized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Theoretical Concepts in AAI With Cancer-Related References.

| Concept | Main tenets | Cancer-related AAI reference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanisms | Compatible Animal Personality | ● Humans can respond to the natural attributes of therapy

animals. ● Both patient and animal temperaments affect the success of therapeutic interactions. |

● Chubak et al31

● Haylock and Cantril25 ● Ginex et al32 |

| Physical Touch | ● Physically touching a therapy animal comforts and benefits the patient directly.46-48 | ● Kaminski et al41

● Cerulli et al42 ● McCullough et al34 ● Schmitz et al36 ● Haylock and Cantril25 ● White et al72 |

|

| Movement | ● Movement motivated by physically interacting with the therapy animal provides exercise-like benefits.36-39 | ● Caprilli and Messeri40

● Kaminski et al41 ● Orlandi et al11 ● Haylock and Cantril25 ● Cerulli et al42 |

|

| Human Interaction | ● Therapy animals can both ease and increase the interactions

between patients and other humans: a “social catalyst”

effect.2,48,55,110

● Increased human interaction directly benefits patients and enhances their general health care environment.11 |

● Orlandi et al11

● Ginex et al32 |

|

| Distraction/Entertainment | ● The novelty of an entertaining AAI visit benefits patients by distracting them from the gravity of their diagnosis or the side effects of their medical treatment regimen.8,25 | ● Kaminski et al41

● Haylock and Cantril25 ● Moreira et al27 ● Yom33 ● Silva and Osório8 |

|

| Attentionis egens | ● Denotes the “need for attention on a normal, basic emotional

level as the prerequisite for successful social interaction.”26

● The success of AAI comes from bidirectional attention-seeking behaviors (where the therapy animal replaces another human). ● The therapy animal’s attention-seeking inspires prosocial behaviors that strengthen the human-animal bond. |

— | |

| Sensory Stimulation | ● Expands on the physical touch mechanism to cover all human senses (ie, canines can affect each of the senses to lower cortisol and engender “physical benefits including a decrease in blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate”).35,100,101 | — | |

| Responsibility/Task Completion | ● Successfully completing activities with a therapy animal can boost patient self-esteem and sense of accomplishment.16,105 | — | |

| Theoretical Frameworks | Biophilia Hypothesis | ● Humans have a natural attraction to other living things—both

flora and fauna.21,57

● Biophilic attraction can open the door to more complex human-animal interactions.31,61,62 |

● Chubak et al31

● Coakley and Mahoney61 ● Kumasaka et al62 |

| Social Support Hypothesis | ● Humans exist in support networks of varying complexity and

magnitude that can define how they react to stress.66-70

● The therapy animal is a special node in the patient’s support network as (a) it cannot judge the patient and (b) may benefit the patient in ways humans cannot.48 |

● Marcus et al71

● White et al72 ● Yom33 ● Petranek et al73 ● Muschel74 ● Silva and Osório8 ● Kumasaka et al62 ● Schmitz et al75 ● Bibbo76 |

|

| Human-Animal Bond | ● “The dynamic relationship between people and animals such that

each influences the psychological and physiological state of the

other.”21,77-80

● A positive human-animal relationship may precede the formation of a bond, but the human-animal bond refers to one patient’s mutual connection to a specific, non-interchangeable therapy animala.21,87,88 |

● Silva and Osório8

● Orlandi et al11 ● Chubak et al31 ● Ginex et al32 ● McCullough et al34 ● Cerulli et al42 ● Coakley and Mahoney61 ● Chubak et al81 ● Johnson et al82 ● Haylock and Cantril25 ● McCullough et al54 ● Fleishman et al83 |

|

| Self-Object Hypothesis | ● The therapy animal is viewed as an ideal object with which the

human forms a stable attachment.89

● Therapy dogs specifically improve a patient’s life as they are nonjudgmental and display joy when interacting with bonded persons.75,90-92 ● For a patient, positive AAI effects come from a better understanding of the self through interaction and bonding with the therapy animal. |

● Petranek et al73

● Johnson et al84 ● Schmitz et al75 |

|

| Cognitive Activation Theory of Stress | ● AAI is only useful to a patient in so much as it helps positively mediate patient responses to the stresses of cancer diagnosis and treatment.93,94 | ● Buettner et al93 | |

| Science of Unitary Humans | ● Organisms are considered as energy fields (consisting of body,

mind, emotions, and environment), and psychological variables

directly affect stress hormones, immune function, and thus

well-being.61,82,95,96

● In AAI, the human’s field interacts with the therapy animal’s field, reducing physiological stress and increasing positive affect for both parties. |

● Coakley and Mahoney61 | |

| Affection Exchange Theory | ● “Affectionate expressions often initiate and accelerate

relational development” and are thus “key to human

survival.”35,106

● The mutual exchange of affection between patient and therapy animal directly results in “enhanced physical and mental well-being experienced by AAI participants.”35 |

— | |

| Attachment Theory | ● Attachment is properly defined as an “an affectional bond with

the added experience of security and comfort obtained from the

relationship.”87,88

● The quality of the human-animal bond directly correlates with the psychological and physiological benefits either party derives from the relationship. |

— | |

| Transduction Mechanisms | Neurobiological transduction mechanism | ● Broadly refers to the neurological or biological pathways that

cause the observed physiological or psychological outcomes in

AAI. ● Though there is likely some overlap, each AAI mechanism may have its own neurobiological pathway.26,51,107-109 |

● Moreira et al27

● Johnson et al84 |

| Oxytocinergic System (in AAI) | ● The hypothesis (a) that all AAI mechanisms aim to release the affiliative chemical oxytocin, and (b) that the observed AAI benefits come from stimulating the oxytocinergic system.100,110-114 | — |

Abbreviation: AAI, animal-assisted interaction.

Though valid, the distinction between human-animal relationships and bonds is often unclear in the language used by AAI researchers.

Proposed Mechanisms of AAI Studies in Oncology

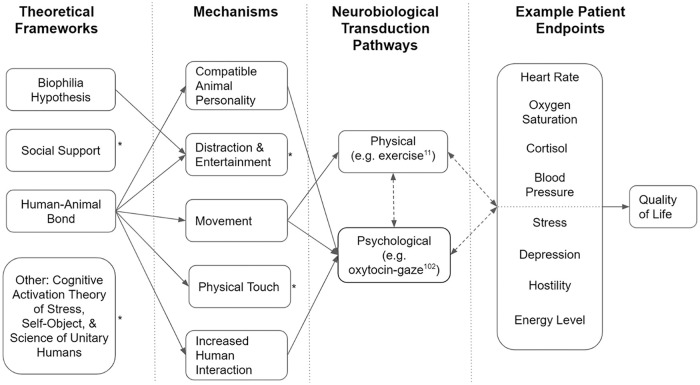

Part I of this systematic review series makes the case that AAI in oncology will greatly benefit from specific methodological improvements and further quantitative evaluation.14 However, more attention to the underlying reasons for the observed effects will also positively affect this work and better illuminate the path to AAI’s wider acceptance. Several articles included in Part I cite or support existing theories as potential explanations for their results. These individual mechanisms and theories are not mutually exclusive and can be grouped together under a “multilayered benefit hypothesis.”27 In other words, it is likely that multiple, overlapping mechanisms best explain how animal-assisted interventions result in the observed effects. We can then group these mechanisms under broader theoretical frameworks in order to define the entire AAI scenario from a high-level perspective and in order to predict certain experimental outcomes. Figure 1 is an example representation—moving from theoretical frameworks to patient endpoints—of how the multilayered benefit hypothesis may work in cancer-related AAI to improve patient quality of life.

Figure 1.

Diagram of multilayered benefit hypothesis example for animal-assisted interaction in oncology.

*Arrows for this concept removed for simplicity. Though not shown here, each framework could potentially extend to other mechanisms on further investigation by researchers.

**Solid, single arrows indicate potential directionality between concepts, while dashed, double arrows indicate interplay or feedback loops between concepts.

The most commonly cited and supported mechanisms of action are animal personality, novel distraction or entertainment, movement, physical touch, and increased human interaction. In this article, we define each mechanism and cite the studies that invoke them to explain results before discussing the implications to AAI in cancer care.

Compatible Animal Personality Mechanism

Compatible animal personality is less a stand-alone mechanism than a beneficial attribute partially described in Part I of this systematic review series but still warrants further discussion. This mechanism expresses the concepts that humans can respond to the natural attributes of the therapy animal and that there may actually exist a class or range of temperaments—for both the animal and the human—that are more ideal for AAI activities than others (ie, a calm vs aggressive personality).28-30 In the study by Chubak et al,31 8 of 18 (44%) inpatient youth participants with cancer reported some variation of the dog being calm or relaxing as what they liked most about AAI. Haylock and Cantril25 specifically sought out laid-back therapy animals, while Ginex et al32 recruited energetic characters. While the studies’ authors make a point to note these preferences, there is no substantive difference in the results of these articles that can be reasonably attributed to the animal’s personality. Regardless, this is certainly an area of interest for improving the prescription of AAI to individual patients with cancer. For example, some patients will benefit from relaxing interactions provided by calm pets, while others may prefer the movement and playful touching encouraged by a more energetic therapy animal. Moreover, the mechanism of compatible animal personality bolsters the case for incorporating other noncanine animals with different temperaments into AAI in oncology. This may not only alleviate infection concerns and transcend particular animal aversions but can also increase AAI’s fit to each patient. Some patients may prefer calming interaction with an AAI dog during chemotherapy, while others may benefit from active interaction with a trained horse to gain the most benefit.

Distraction and Entertainment Mechanism

The distraction or entertainment mechanism holds that an animal visit can serve to break up the monotony of regular or hospital life for a patient and that many observed benefits come directly from the novelty of AAI in a given moment. Some authors mention novelty-type explanations in passing when explaining results.25,27,33 Silva and Osório8 go so far as to state that the distraction effects of canine-assisted interactions are notable. As with previous mechanisms, this distracting effect extends to equine-assisted therapy with patients regarding the AAI as a diversion from stressors related to a cancer diagnosis and treatment.25 If accurate as posited, this distraction mechanism may have an interesting corollary when isolated experimentally: longitudinal AAI studies would see a benefit in the beginning that tapers off with sufficient time after the novelty of pet therapy fades. McCullough et al34—who made every effort to pair individual subjects with the same therapy animal throughout their study—reported no significant changes in any tested parameter for patients before and after the full data collection period (eg, 4 months per patient). Bearing these and similar results in mind, researchers may have to choose between encouraging a bond with a particular animal, as in McCullough et al,34 and introducing a new therapy animal each session to maximize novelty—the latter proposition potentially being both unscalable and resource-intensive. Distraction mechanisms leave space for other complementary and alternative medicines to be similar to AAI in usefulness for oncology—provided that they are sufficiently novel and distracting (ie as entertaining as a dog rolling over or wagging its tail).35 Despite this, Moreira and colleagues27—and the authors of this literature review—suggest that there are deeper reasons (eg, the physical touch mechanism) beyond or in addition to mere distraction that result in the observed benefits of AAI. Additionally, constantly introducing new therapy animals to maintain this effect could be prohibitively taxing on the therapy teams, the patients, and the resources of the AAI program.

Movement Mechanism

The movement mechanism relies on physical exercise explicitly. As opposed to sitting quietly and stroking a therapy animal, this mechanism would provide an impetus for participants to move around with the therapy animals and experience the concomitant benefits of such exercise.36-39 Support for this mechanism within cancer-related AAI comes from the studies by Caprilli and Messeri40—who allowed sufficiently ambulatory patients to walk the therapy dog—and Kaminski et al41—who included the dogs in a child-life playroom. Orlandi et al11 also emphasized that the significant increase they observed in the AAI group’s oxygen saturation may be due to physically moving about and interacting with the therapy dog as opposed to only sitting while receiving chemotherapy. Both Haylock and Cantril,25 and Cerulli et al42 led studies that included participants’ walking and riding horses to positive effect, further supporting the physical movement idea. This physical activity mechanism necessarily excludes many patients who may not be sufficiently ambulatory from experiencing the benefits of AAI that are due to increased movement. The movement mechanism does not account for the vast majority of studies that prohibited vigorous activity but still observed benefits from AAI. Thus, it is likely that movement is an advantage to AAI but certainly not the sole—or even arguably the major—source of its benefits, though its prospective benefits similarly cannot be ignored.43-45

Physical Touch Mechanism

The physical touch mechanism explicitly refers to the stroking of the animal as the external mechanism for benefits seen in AAI.46 Stroking a dog’s fur provides tactile comfort, decreases tension, and allows patients to feel safe in their environment.47,48 Odendaal26 goes so far as to say that touching a therapy animal satiates a “skin hunger” or innate desire to be touched in patients and other isolated individuals. Support for these ideas comes from Kaminski and colleagues who contend that affiliative touching contributes more to AAI’s effects than cognitive factors, even though the experimental group in their work saw only mood and behavior changes compared with a control group.41,49 When explaining results, they also cite the work by Friedmann et al50 that shows contact comfort with a dog was significantly associated with a reduction of heart rate and blood pressure. In their discussion, Cerulli et al42 extend the importance of physical touch to equine-assisted therapy, noting that the physical contact of grooming and riding bolsters a rider’s relationship with a horse. In the study by McCullough et al,34 the activity most selected by children (92%) and parents (55%) alike was petting the therapy dog, making this result the rule rather than the exception in studies coding patient-animal interactions. Odendaal and Meintjes51 observed that physical touch between a human and an animal directly elicits certain biochemical effects such as increases in oxytocin and beta-endorphins. The work of Charnetski et al52 and Barker et al53 on the ability of stroking animals to increase immunoglobulin A is potentially relevant to decreasing certain risks of infections and illnesses in oncology. Despite this evidence supporting the benefits of affectionate touching between human and a therapy animal, there remains some doubt in the field. That is, some studies have shown similarly positive effects using stuffed animals—which are comparably pleasant to touch—as compared with live animals,28 while other work appears to contradict these findings.29 Additionally, certain forms of touching may be experienced as unpleasant for the therapy animal.30 However, for several of the studies included in this review, stroking the therapy animal was the most common affiliative behavior, accompanied by very few signs of high stress from the animals involved.34,41,54 These contrasting results can challenge the idea that a live animal is needed to experience beneficial effects similar to those of AAI. However, physical touch is only one of several mechanisms active during AAI, and the combination of several such mechanisms inherent to human-animal interaction may ultimately be what fully makes animal-assisted interventions beneficial.

Increased Human Interaction Mechanism

While seemingly misplaced in the sphere of animal-assisted interventions, increased human interaction as a mechanism speaks to the positive effects that occur when a therapy animal eases the interplay between humans.2,48 Simply, amiable social interactions with other humans can provide observable benefits to patients and therapy animals can serve both to facilitate these interactions and as a noncontentious topic of discussion.55,56 Orlandi et al11 suggest that even the additional care given by medical staff when distributing questionnaires and monitoring vital parameters during AAI could reduce patient anxiety. This assertion may explain the identical effects observed in both the control and experimental groups of Orlandi and colleagues’ study.11 Regarding AAI in an acute care setting, Ginex et al32 similarly posit that AAI-inspired collaboration between various medical services enhanced the healing environment. The essence of the human interaction mechanism would thus be that AAI—in addition to having direct positive effects on patients—also tangentially initiates a cascade of positive events or environments that improves patient outcomes. It follows from the formulation of this mechanism that the therapy animal promotes beneficial interactions with friendly animal handlers and with other patients in a group treatment setting. However, quality time and interactions with the therapy animal could be limited in a group setting due to increased human interaction, and direct benefits offered by the therapy animal must be appropriately balanced in these scenarios.

Proposed Theoretical Frameworks of AAI Studies in Oncology

The individual mechanisms of action for AAI discussed can be grouped under broader theoretical frameworks proposed by researchers. As previously noted, this is done in order to define the entire AAI scenario from a high-level, “multilayered benefit” perspective and in order to predict certain experimental outcomes.27 The overarching frameworks explicitly cited by AAI researchers in oncology include the biophilia hypothesis, the social support theory, the general human-animal bond theory, the cognitive activation theory of stress, self-object hypothesis, and the science of unitary humans. In this article, we discuss how the biophilia hypothesis opens the door for both the social support theory and the conceptualization of a human-animal bond before discussing other potential frameworks for understanding AAI’s effects.

Biophilia Hypothesis

A concept cited in several studies, the main ideas of the biophilia hypothesis were laid out by Stephen R. Kellert and Edward O. Wilson in 1993 and hold that humans have a natural attraction to other living things—both flora and fauna.21,57-60 For animal-assisted interventions, this idea provides for the initial impetus of the subject to interact with the animal. Thus, the biophilia hypothesis—specifically channeling the distraction mechanism—could also explain the benefit received from single session animal interventions of short duration where neither full integration into the patient’s support network nor the development of a bond has reasonably had time to occur. We also contend that the innate attraction insinuated by Kellert and Wilson’s hypothesis can open the door to and undergird any future bonds or networks formed with the therapy animal. Even though the quantitative data remain open to interpretation, results from single intervention and short-term studies show that most participants were very eager to see the pet enter the room and smiled throughout the intervention.31,61,62 If additional therapeutic benefits flow as a result, this lends credence to the idea that biophilic attraction can open the door to more complex human-animal interactions.

Social Support Hypothesis

The social support conception of AAI is closely related to general social support theory.63-65 The latter has several tenets and variations but essentially contends that humans exist in support networks of varying complexity and magnitude that can define how they react to stress.66-70 For AAI under this framework, the therapy animal is inserted as another useful node in a patient’s support network. However, the therapy animal inserted in a patient’s network avoids certain pitfalls and provides different benefits than traditional human interactions (eg, the therapy animal cannot judge the therapy recipient).48 Marcus et al71 specifically note that “kids and families need a support group” when discussing what AAI offers to patients in oncology. Similarly, White et al72 provide several anecdotal statements showing that the therapy animal adds to the counseling support network such as “I was more open to the [counselor] than I have been with other people [counselors] in the past” and “they’re just very comforting, I think, dogs are very not judgmental.” Other researchers also comment that a therapy animal can be a nonjudgmental listener33,62,72-74 or facilitate interactions with medical staff,8,72,74-76 both increasing a patient’s sense of perceived support during stressful treatment processes. This conception of patient support may also explain previously discussed mechanistic vehicles—such as compatible personalities, positive physical touch, and improved human interactions as well as their underlying neurobiological factor—seeing that therapy animals are specifically introduced to patients as part of the medical support staff as opposed to as someone’s pet. For the distraction and movement mechanisms, social support theories may only have explanatory power indirectly. In other words, providing distraction and impetus for movement can be, but are not necessarily, definitive functions of support groups. It is worth noting that the social support theory often cited by AAI researchers is extremely general by definition and thus lacking in predictive power.

Human-Animal Bond Hypothesis

The Center for the Human Animal Bond defines the human-animal bond as “the dynamic relationship between people and animals such that each influences the psychological and physiological state of the other.”21,77-80 The resulting hypothesis is that as the bond between a human and an animal matures, both parties benefit. Evidentiary support for the human-animal bond conception for AAI in oncology is mixed: some investigated endpoints displayed posttreatment effects8,11,31,32,34,42,61,81,82 while others have not.8,11,25,34,54,61,82,83 Complicating things further, methodological design is not consistent across studies, and studies are not yet directly geared toward elucidating the existence or effects of the human-animal bond.14 To date, the sole cancer-related study to maintain the same animal-handler team throughout—a true test of the bond idea—observed mediocre effects: no significant changes in the intervention group after the study period.34 Other studies that asked questions concerning patient attitudes toward pets largely found no significant correlation between these response measures and the treatment outcomes of interest.34,61,62,71,72,75,76,83,84 For prospective researchers, one troublesome aspect of this particular AAI conception is its necessitation of longitudinal studies that can allow a bond to fully develop, even though tools like the Monash Dog Owner Relationship Scale85 and the Lexington Attachment Scale can provide some indication of a bond’s strength.86 Additionally, the bond in question is a metaphysical phenomenon that cannot be interrogated directly and must be studied proximally through its effects. Fortunately, the human-animal bond is defined very broadly and in such a way as to account for most all of the aforementioned mechanisms implicated in causing cancer-related AAI’s effects. Similar to the social support theory, however, this broad definition diminishes the predictive capacity of the bond framework. Also, both Rehn and Keeling,87 and Hosey and Melfi21 raise an interesting point in their review of human-animal interactions work including everything from AAI to agricultural animals: there should be a fundamental, definitional distinction between human-animal bonds and human-animal relationships.88 A relationship suggests some unspecified interaction with similarly unspecified effects for either participant but, the authors maintain, a bond indicates that a connection with a particular individual has been formed.87,88 In other words, human-animal relationships would only refer to a patient’s positive interactions with therapy animals over the short or long term. The human-animal bond would define a patient’s mutual connection to a specific therapy animal—one that, for the patient, is not interchangeable with any other therapy animal in ways similar to the advanced relationship between an owner and his pet. However, as humans can form bonds with multiple humans, they can likely form relationships and bonds with multiple therapy animals. Although Hosey and Melfi21 raise excellent points, to avoid any potential confusion in the remainder of this review, we will continue to use the more common definition of human-animal bond set forth at the outset of this paragraph.

One should note that the human-animal bond and social support theories as defined by the researchers in cancer-related AAI are different in meaningful ways. Social support necessitates integration of the animal into an existing network that provides resilience to stress. Here, the therapy animal provides direct benefits to a subject while also improving that subject’s interaction with other support nodes (eg, nurses, doctors, and family members). On the other hand, the human-animal bond theory does not require network integration nor does it insinuate any concomitant benefits beyond the human and animal in question. Rather, it suggests that the beneficial effects of animal-assisted interventions extend beyond coping with specifically stressful situations (eg, cancer treatment) and that these same effects can persist in other contexts ad infinitum as the bond strengthens. As the 2 theories are most often cited by AAI researchers in oncology, the social support hypothesis and the human-animal bond framework are not mutually exclusive and are likely complementary in producing the observed positive results.

Other Theoretical Frameworks

In this treatment of the main explanations of AAI’s benefits in oncology, we must also mention the other ideas proffered by some researchers in the field: the self-object hypothesis, the cognitive activation theory of stress, and the science of the unitary human.

Self-Object Hypothesis

The self-object hypothesis regards the therapy animal as an ideal object with which the human forms a stable attachment.89 Furthermore, therapy dogs specifically improve a patient’s life as they are nonjudgmental and display joy when interacting with bonded persons.75,90-92 Taken together, the self-object hypothesis implies that any positive AAI effects experienced come from a better understanding of the self through interaction with the therapy animal. This is illustrated by Petranek et al73 who note that, before AAI sessions, patients can feel as if they are just their disease or as if they are passively waiting to be fixed by the attending medical staff. The authors thus argue that observed benefits come directly from patients’ perception that participating in the study may be “doing something constructive or good for others and not just themselves.” Johnson et al84 reiterate this point stating that AAT and complementary medicines in general help patients exert control of their illness and their quality of life, resulting in a sense of active participation that produces positive effects. Essentially, patients can conceptualize themselves as more than their illness through interaction with the self-object of the AAI therapy animal. The greatest strength of this hypothesis is that it makes a clear affirmative case for the importance of the animal as a complementary medical treatment. For example, neither a therapeutic massage, a stuffed animal, nor chatting with a friendly stranger will utilize the specific psychological pathways hypothesized by the self-object construction. Only a live therapy animal has all of the relevant characteristics to take on this role.

Cognitive Activation Theory of Stress

Buettner et al93 make a case for the cognitive activation theory of stress as a way to understand AAI’s benefits in oncology. This conception is based on general arousal and activation theory and focuses on specific definitions of stress in order to characterize and evaluate the effectiveness of reactions to stress.93,94 Interestingly, Ursin and Eriksen94 note that “an essential element of cognitive activation theory of stress [is] that only when coping is defined as positive outcome expectancy does the concept predict relations to health and disease.” For AAI, the cognitive activation theory of stress forms a psychobiological foundation.93 Essentially, AAI is only useful to a patient under this framework in so much as AAI helps him mediate his response to the stresses of cancer diagnosis and treatment. Buettner and colleagues thus designed their study with the aim of reducing cognitive stress loads, while patients were in the cancer treatment waiting room.93 While this theory somewhat resembles the previously discussed social support networks idea, the cognitive activation theory of stress presents a clearer pathway from overarching concept through to biochemical mechanism of action under its framework. Rather than existing as a generalized node in a fluid support network, the therapy animal directly alters the patient’s stress response and the concomitant physiological correlates (like cortisol or heart rate) during a typical intervention.

Science of Unitary Humans

Coakley and Mahoney61 discuss both the science of unitary humans and psychoneuroimmunology as explanations of AAI’s effects in their study. Within this framework, organisms are considered as energy fields consisting of body, mind, emotions, and environment.61,95 The psychoneuroimmunology component holds that “psychological variables have a direct effect on ‘stress’ hormones and that these, in turn, can modulate immune function and psychosocial well-being,” somewhat similar to the cognitive activation theory of stress.82,96 Thus, in AAI, the human’s field interacts with and is altered by that of the therapy animal as the intervention proceeds. These interactions and energy alterations could then conceivably lead to reduced physiological stress and increased positive affect for both parties participating in the interaction. Although the science of unitary human beings has been met with some skepticism and valid critiques, this theory expands the conception of AAI beyond the physicality of the 2 actors (patient and animal) involved in the therapy.97,98 In other words, the main actors in AAI are not just bodies, but also minds and emotions interacting in a specific environment that also affects the 2 actors’ outcomes. Part I of this review series makes a similar case when contrasting the effects of group and individual therapies and when considering the impacts of private versus communal treatment locations for cancer patients.14 While the science of the unitary human concept is still compatible with both the human-animal bond and social support network frameworks, neither of the latter 2 theories explicitly accounts for how situational or environmental considerations may affect AAI outcomes.

Even though the aforementioned hypotheses have some explanatory power and predictive capacity for cancer-related AAI, no researcher claims these to be complete. Additionally, the theoretical frameworks cited thus far are somewhat overbroad and generally derived from tangentially related fields. While this can be an appropriate starting and comparison point, the cancer-related AAI field will surely benefit from a more detailed theoretical formulation unique to the constructs and idiosyncrasies of animal-assisted interventions.99 Alternatively, multiple theories and frameworks can be knit together to fully explain AAI’s range of effects. Noting the complex and potentially overlapping theories and mechanisms involved, it is possible that different hypotheses of action may be necessary for different subfields of AAI. For example, an autistic individual may receive general benefits from a therapy animal similar to those seen in patients with cancer but also in a few ways unique to that class of conditions. While this makes the theoretical underpinnings of cancer-related AAI slightly more complicated to parse, it does imply the future possibility of targeted prescription of animal therapies to specific individuals in order to maximize positive effect.

Other Explanatory Concepts

Although we have focused on the mechanisms and frameworks explicitly noted by AAI studies in oncology, other theories encountered throughout the human-animal and AAI fields should be briefly mentioned due to their relevance to the field.

Attentionis Egens

Humans and other species with advanced social systems evolved, among other things, “attention-need behaviors.”26 This fact leads Odendaal26 to put forth attentionis egens as a mechanism for understanding the human-animal interaction and its effects. Attentionis egens simply denotes the “need for attention on a normal, basic emotional level as the prerequisite for successful social interaction.” Odendaal26 holds that the success of AAI is largely based on bidirectional attention-seeking behaviors where the therapy animal effectively assumes a role normally held by another human. A strong need for attention from the human leads to increased social behaviors by the animal, which, in turn, leads to a stronger human-animal bond overall. Effective handling of the attention needs leads directly to physiological changes (ie, increases in typically affiliative neurochemicals) that mutually benefit humans and animals involved. This concept helps explain the successful inclusion of dogs into therapy environments such as cancer care. Dogs are highly social animals and can serve as an interspecies provider of attention and support for socially isolated or otherwise suffering individuals.2 Attentionis egens may also explain why “friendly human” controls often appear to supply the same benefits to oncology patients as AAI sessions.82,84 Attentionis egens is an interesting concept when juxtaposed with the increased human interaction mechanism. The latter holds that the therapy animal is a route to get more human attention, but attentionis egens says that the interaction with the therapy animal can, in itself, be a source of attention.

Sensory Stimulation

Physical touch and its benefits are conceivably just one of several sources of positive sensory stimulation provided by a therapy animal. In fact, some researchers argue that dogs can affect each of the senses to lower cortisol levels and engender “physical benefits including a decrease in blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate.”35,100,101 For example, Nagasawa et al102 found that owners merely looking at their dogs was enough to significantly increase urinary oxytocin concentrations in both species. Similarly, Rehn et al103 found that the “mere reappearance of a person can elicit oxytocin release in dogs” that can last for a significant duration with physical affirmation. Though physical touch is the most thoroughly studied sensory stimulation paradigm, it is very conceivable that patients could—and likely already do—gain some additional benefit from seeing, hearing, and smelling the therapy animal in an AAI session.100

Responsibility/Task Completion

The next concept does not have a formal label but holds that completing defined tasks and activities with an animal can lead to positive benefits for the involved human. For example, a therapy dog could help a patient find a toy item, or a therapy horse could work with the patient to traverse a riding course. In either scenario, the responsibility and cognitive burden for achieving the goal is shared by the patient and the therapy animal, either consciously or unconsciously. Another example simply includes the patient caring for and grooming the animal—a therapy component already included in many equine-assisted therapy programs.25,42,104 The additional benefits this responsibility concept offers—beyond the physical exercise or contact inherent to the AAI scenario—largely lie in the self-esteem boost inherent to taking on additional responsibility and the sense of accomplishment gained from successfully completing a task.16,105

Affection Exchange Theory

Affection exchange theory generally holds that “affectionate expressions often initiate and accelerate relational development” and are thus “key to human survival.”35,106 Briefly, there are 5 constituent postulates of affection exchange theory: (1) humans inherently desire affection; (2) feelings of affection are not always accompanied by expressions of affection; (3) affectionate expressions aid human reproduction long term; (4) individuals vary in affection need; and (5) violating an individual’s affection needs is deleterious.35 With the exception of the third, this theory’s tenets can be readily adapted to AAIs and, properly understood, many of these postulates even mirror other previously discussed concepts (eg, biophilia hypothesis).35 Thus, the mutual exchange of affection between patient and therapy animal would result directly in “enhanced physical and mental well-being experienced by AAI participants.”35 Affection exchange theory interacts well with the aforementioned social support hypothesis. Additionally, the fourth postulate is one of the few explanatory concepts that may shed light on how animals with differing personalities may affect AAIs, rooting this in patient preference (ie, preferring a calm therapy animal to an energetic one).

Attachment Theory

An attachment is properly defined as an “an affectional bond with the added experience of security and comfort obtained from the relationship.”87,88 Much like the variation seen in parent-child attachments, human-animal attachments vary widely and should be investigated at the “individual [animal] level, rather than talking about the ‘average’ [animal].”87 The testable prediction for AAI in oncology would be that the strength of the attachment and thus the quality of the overall bond correlates directly to the psychological and physiological benefits either party derives from the comforts of the relationship. However, so far and for various methodological reasons, the research conducted in cancer-related AAI that also interrogated pet attitudes, ownership, and attachments does not find a statistically significant correlation to results. Other work in noncancer human-animal interactions finds that closer relationships lead to stronger observed effects resulting from activation of the oxytocinergic system in both humans and dogs.26,107 By analyzing an individual therapy animal’s attachment and a specific patient’s caregiving behaviors, attachment theory can be used to differentiate the quality of bonds under the broad human-animal bond framework after they have been formed.

Neurobiological Transduction Mechanisms

The mechanisms discussed to this point suggest an observable cause for AAI’s effects but primarily focus on factors external to the human participant. Our understanding of how AAI generates positive emotions and effects would be incomplete without considering the neurobiological transduction mechanisms. This refers to the exact connections and pathways between proposed AAI mechanisms and the observed physiological or psychological outcomes, all following from the overarching frameworks (Figure 1). Previously, we mentioned Odendaal et al’s work elucidating the biochemicals released during affectionate contact between humans and animals.51,108 They found that affectionate human-dog interactions positively affect dopamine, cortisol, oxytocin, prolactin, endorphin, and phenylethylamine concentrations in both humans and dogs. Moreira et al27 also cite the release of endorphins and adrenaline in the bloodstream as a reason deeper than the distraction mechanism for AAI’s positive effects. They further maintain that these biochemicals are the actual physiological correlates and links to their observed result of decreased heart rate variability postintervention. Further supporting this idea, Johnson et al84 generally note that interacting with an animal has effects in the body that are psychological, but that also play into a feedback loop with the endocrine and immune systems.

Although much of the work on the biochemicals that actually produce the effects noted with cancer-related AAI has focused on the physical touch mechanism, the idea of neurobiological transduction extends to all of the other mechanisms as well.26,51,107-110 In other words, the tenets of each framework allow for the interplay of certain mechanisms, and these mechanisms, in turn, directly affect the neurobiology of the patient (Figure 1). For example, the physical touch mechanism requires recruitment of a sensory neural pathway—in this case, touch—before the conscious mind can process the positive physical stimulation and the situational context (ie, the AAI session). From here, the brain naturally responds by releasing dopamine, epinephrine, and other neurochemicals, resulting in a betterment of mood and a generally positive effect.26,51,108 This example transduction pathway would be significantly different than that employed when exercising with a therapy animal via the movement mechanism. Here, the factors impacting the patient’s positive affect would stem from the positive benefits of exercise and the neurochemicals it releases. Similar theoretical pathways can be postulated for each remaining mechanism—with the possible exception of compatible animal personality. The transduction pathways may ultimately end in the release of similar sets of neurochemicals, but the pathways to their release are slightly different for each mechanism. In the future, this conception of neurobiological transduction may be a potent way to differentiate the effects of certain mechanisms that make up a framework. Again, while both may lead to release of dopamine, physical touch versus therapy animal gaze must traverse different biochemical pathways to achieve the same positive effect. With properly constructed AAIs, diligent researchers could isolate each mechanism and its pathway, improving our understanding of certain frameworks and clarifying how the mechanisms interplay. Gee et al28 noted that different therapies may be effective for different kinds of stressors so the neurobiological transduction idea also opens the door for targeting types of AAI to the different needs of cancer patients. The concept of neurobiological transduction may also help differentiate which mechanisms provide direct psychological benefits without taking a detour through a certain physiological pathway. For example, some mechanisms, such as touch or exercise, clearly rely on physical transduction pathways, while others, such as therapy animal gaze, merely require the human to see the dog and psychologically recognize the positive benefits. However, it is likely that there is a complex regulation of biochemicals within a mechanism’s delineated neurobiological pathway and that the causality within the system is not straightforward.

This said, there is a viable candidate for a unifying AAI neurochemical, and Beetz et al110 make a compelling case that all of the beneficial effects of AAI are likely the products of stimulating the oxytocinergic system specifically. Johnson100 also supports this explanation, implicating cortisol as a major actor alongside oxytocin. For Beetz et al,110 all of the mechanisms and the related transduction pathways aim to release oxytocin, leading to every AAI benefit observed (eg, decreases in depression, increases in oxygen saturation, etc). This theory is eminently plausible as oxytocin is well understood to be the bonding or affiliative neurochemical peptide.111-114 Additionally, such releases of oxytocin can still affect outcomes in short-term positive interactions, explaining AAI’s efficacy in interventions with short durations, low frequencies, or both. Oxytocin as the neurochemical of final interest also explains certain observed gender-specific AAI effects (eg, women’s oxytocin increases after pet dog interaction whereas men’s oxytocin decreases).86 Furthermore, oxytocin is known to inhibit the release of cortisol and thus could play a significant, direct role in the patient stress reduction observed. Beyond postulates about the role of oxytocin, a precise biochemical pathway with clear neurological candidate peptides for AAI’s observed physiological effects in patients and therapy animals alike has not been fully delineated.

Conclusions

Discussion of Theoretical Limitations and Suggestions

To address many of the nonmethodological limitations of the AAI field in oncology, AAI in oncology and pet therapies generally require a more rigorous treatment of the theoretical aspects of the phenomenon and the concomitant explanations of results this can provide. Ideally, as a few researchers have noted,61,93 the norm would be starting from the highest theoretical level and then designing an experiment to evaluate one’s predictions. Researchers with various hypotheses in the AAI space would thus have clearer and, importantly, more connected experimental paths. This would also allow researchers to effectively tackle problems such as determining when a stable, human-animal bond has formed or identifying exactly which physiological or psychological parameters are most relevant to AAI in oncology. Additionally, deriving studies from a larger theoretical substrate can greatly improve control condition designs as the latter would necessarily depend on the intervention’s proposed mechanisms of action.

Most work in the AAI field has not yet considered the therapy animal’s perspective and the positive or negative effects (eg, increased animal stress due to rough handling) that AAI can have for them.21 As such, the field’s efforts could also benefit from the development of theoretical frameworks recognizing that the nature and outcomes of treatment for humans will likely vary directly with the state of the therapy animals involved. In fact, mechanisms of action that directly address how AAIs affect the therapy animal in the near or long term would be an additional boon to the field. With more data from this perspective in hand, researchers could also know whether or not AAI is a zero-sum game with 1-sided benefits for humans—an outcome in stark opposition to the human-animal bond hypothesis and many other proposed frameworks.

Our discussion of the theoretical frameworks focuses on hypotheses advanced by the AAI articles in oncology and includes a brief treatment of other relevant concepts in the human-animal interactions literature. From this, it is clear that there is tremendous overlap in the theoretical concepts put forth to account for human-animal interactions and AAIs’ effects. This overlap—coupled with patterns in observed psychological and physiological outcomes—strongly suggests that future work may evolve into a unified conception of AAI. At the moment, of the few researchers who even consider the theoretical implications of their work, many do not consider if their results have multiple mechanistic explanations or fit under multiple frameworks.21 Here, the aforementioned significant overlap of theory prescriptions in AAI means that some results can just as easily be described by a framework different from that implicated by a researcher. This is not a critical limitation for the field or for the prospect of a unified theory. When implicating certain explanatory concepts, special attention should be paid to results that either effectively support the named concept to the exclusion of all others or, when considered as a whole, closely reflect the named concept’s tenets.

Theories in the AAI field appear to implicitly account for the effect of the environment on patient outcomes, but this may not be sufficient. It is conceivable that many treatment environment decisions have observable effects on patient outcomes and animal welfare. For example, delivering AAI sessions in a patient’s hospital room may boost patient comfort levels—important to the attachment theory. However, AAI sessions in a designated therapy space may increase a patient’s ability to exercise and physically interact with the therapy animal—important to the movement mechanism. Other examples such as indoor versus outdoor treatment and one-on-one versus group animal therapy could have constructive or destructive impacts on various AAI mechanisms of action. Researchers rightly tailor their treatment strategies and protocols to the needs of their patients, but study design should also consider the implications for theoretical mechanisms and the related effects on clinical outcomes.

Another theoretical limitation that is not easily resolved relates to the accepted definition of success in AAI. As many authors note, the AAI field does have methodological weaknesses that challenge the validity of certain claims or produce effects in clinical endpoints that are not statistically significant.15,18,19,115 However, these results may still be clinically significant and the general acceptance of anything that helps cancer patients even somewhat may also be valid. Turner et al115 specifically provide the analogy to drugs in medicine that “do not have a statistically significant effect on a given patient sample” but still “lower blood pressure, heart rate, or cholesterol”—without side effects—in a clinically significant way. The AAI field in oncology should certainly adopt various methodological best practices to provide for high-quality results. However, the field should potentially also take appropriate consideration of statistically insignificant results that, “on more critical review, may well be clinically significant.”115 While researchers in cancer-related AAI are not all pursuing the same treatment goals beyond improved patient quality of life, lenient and inclusive definitions of success provide for more combinatorial treatment paradigms.116 As an example, the same patient can benefit from therapy animals in waiting rooms before his radiation therapy sessions,83 during cancer-related counseling,72 as well as during the recovery period following cancer remission.42 To be useful, theoretical frameworks must be able to account for the known effects of a patient’s stage of cancer and clinical treatments when combined with AAIs.

Summary and Conclusion

In Part I of our 2-paper systematic literature review series, we presented the results of a systematic literature review evaluating the designs and efficacy of animal-assisted intervention studies in oncology through quantitative metrics.14 Here in Part II, we provided a discussion of the mechanisms of action proffered by researchers to explain the observed experimental results before briefly discussing a few other relevant ideas throughout the AAIs field. These mechanisms included compatible animal personalities, pleasant tactile contact, physical movement, novel distraction, and increased human-to-human interaction. These mechanisms overlap and interplay within overarching theoretical frameworks of which the social support network and human-animal bond concepts are the most prominent. Some researchers also invoked other ideas such as the self-object hypothesis, the cognitive activation theory of stress, and the science of the unitary human when discussing their work. We also attempted to connect frameworks and mechanisms to the observed psychological and physiological outcomes by discussing the known neurobiological transduction methods and the critical role of oxytocinergic systems in AAI.

While AAI work in general and in oncology has room to grow, the field has significant promise to positively affect patients’ quality of life. Future studies should actively incorporate and test solid theoretical frameworks based on quantitative observations to advance the field’s understanding of AAI in oncology. For cancer-related AAI specifically, researchers should also consider experimental outcomes achieved in related subfields (ie, AAI’s benefits in recovery from noncancer surgeries likely apply somewhat to recovery from oncological surgeries).32,117,118 The concepts discussed in this review can help researchers focus on elucidating the effects of one mechanism, to maximize benefits for patients by combining several mechanisms, and to attempt everything in between. All things considered, the AAI field is especially poised to make significant progress toward a unified theoretical framework and, more important, toward effectively treating cancer patients in a holistic way.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors acknowledge support from the United States National Science Foundation through CCSS-1554367, ECC-1160483, and IIS-1329738. This material is also based upon work supported by IBM Faculty Awards.

ORCID iD: Timothy Ricardo Nathaniel Holder  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6788-9970

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6788-9970

References

- 1. Spiegel D. Mind matters in cancer survival. Psychooncology. 2012;21:588-593. doi: 10.1002/pon.3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Friedmann E, Son H. The human-companion animal bond: how humans benefit. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2009;39:293-326. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2008.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Soothill K, Morris SM, Thomas C, Harman JC, Francis B, McIllmurray MB. The universal, situational, and personal needs of cancer patients and their main carers. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2003;7:5-13. doi: 10.1054/ejon.2002.0226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weber D, O’Brien K. Cancer and cancer-related fatigue and the interrelationships with depression, stress, and inflammation. J Evid Based Complement Altern Med. 2017;22:502-512. doi: 10.1177/2156587216676122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borneman T, Piper BF, Koczywas M, et al. A qualitative analysis of cancer-related fatigue in ambulatory oncology. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:E26-E32. doi: 10.1188/12.CJON.E26-E32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Perrine RM. On being supportive: the emotional consequences of listening to another’s distress. J Soc Pers Relat. 1993;10:371-384. doi: 10.1177/0265407593103005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Miczo N, Burgoon JK. Facework and nonverbal behavior in social support interactions within romantic dyads. In: Motley M. ed. Studies in Applied Interpersonal Communication. Sage; 2014:245-266. doi: 10.4135/9781412990301.n12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Silva NB, Osório FL. Impact of an animal-assisted therapy programme on physiological and psychosocial variables of paediatric oncology patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations. The IAHAIO definitions for animal assisted intervention and guidelines for wellness of animals involved. IAHAIO White Paper. Published 2014. Accessed January 21, 2019 http://iahaio.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/iahaio-white-paper-final-nov-24-2014.pdf

- 10. Pet Partners. Terminology. Accessed March 28, 2019 https://petpartners.org/learn/terminology/

- 11. Orlandi M, Trangeled K, Mambrini A, et al. Pet therapy effects on oncological day hospital patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(6C):4301-4303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McCune S, Kruger KA, Griffin JA, et al. Evolution of research into the mutual benefits of human-animal interaction. Anim Front. 2014;4:49-58. doi: 10.2527/af.2014-0022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takashima GK, Day MJ. Setting the one health agenda and the human-companion animal bond. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:11110-11120. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111111110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holder TRN, Gruen ME, Roberts DL, Somers TJ, Bozkurt A. A systematic literature review of animal assisted interventions in oncology (part I): methods and results. Preprint. Posted online December 19, 2019. Integr Cancer Ther. doi: 10.20944/preprints201912.0242.v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herzog H. The research challenge: threats to the validity of animal-assisted therapy studies and suggestions for improvement. In: Fine AH. ed. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2015:402-407. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kazdin AE. Methodological standards and strategies for establishing the evidence base of animal-assisted therapies. In: Fine AH. ed. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Foundations and Guidelines for Animal-Assisted Interventions. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2015:377-390. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-801292-5.00027-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marino L. Construct validity of animal assisted therapy and activities: how important is the animal in AAT? Anthrozoos. 2012;25:s139-s151. doi: 10.2752/175303712X13353430377219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stern C, Chur-Hansen A. Methodological considerations in designing and evaluating animal-assisted interventions. Animals (Basel). 2013;3:127-141. doi: 10.3390/ani3010127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chur-Hansen A, McArthur M, Winefield H, Hanieh E, Hazel S. Animal-assisted interventions in children’s hospitals: a critical review of the literature. Anthrozoos. 2014;27:5-18. doi: 10.2752/175303714X13837396326251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cirulli F. Animal-assisted therapies and activities as innovative approaches to mental health interventions. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2011;47:339-340. doi: 10.4415/ANN_11_04_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hosey G, Melfi V. Human-animal interactions, relationships and bonds: a review and analysis of the literature. Int J Comp Psychol. 2014;27:117-142. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kruger KA, Serpell JA. Animal-assisted interventions in mental health: definitions and theoretical foundations. In: Fine AH. ed. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice. Elsevier; 2010:33-48. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-381453-1.10003-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gilmer MJ, Baudino MN, Tielsch Goddard A, Vickers DC, Akard TF. Animal-assisted therapy in pediatric palliative care. Nurs Clin North Am. 2016;51:381-395. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Palley LS, O’Rourke PP, Niemi SM. Mainstreaming animal-assisted therapy. ILAR J. 2010;51:199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haylock PJ, Cantril CA. Healing with horses: fostering recovery from cancer with horses as therapists. Explore (NY). 2006;2:264-268. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2006.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Odendaal JS. Animal-assisted therapy—magic or medicine? J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:275-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moreira RL, do Amamral Gubert F, de Sabino LMM, et al. Assisted therapy with dogs in pediatric oncology: relatives’ and nurses’ perceptions. Rev Bras Enferm. 2016;69:1188-1194. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gee NR, Friedmann E, Coglitore V, Fisk A, Stendahl M. Does physical contact with a dog or person affect performance of a working memory task? Anthrozoos. 2015;28:483-500. doi: 10.1080/08927936.2015.1052282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shiloh S, Sorek G, Terkel J. Reduction of state-anxiety by petting animals in a controlled laboratory experiment. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2003;16:387-395. doi: 10.1080/1061580031000091582 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuhne F, Hößler JC, Struwe R. Behavioral and cardiac responses by dogs to physical human-dog contact. J Vet Behav Clin Appl Res. 2014;9:93-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2014.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chubak J, Hawkes R, Dudzik C, et al. Pilot study of therapy dog visits for inpatient youth with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2017;34:331-341. doi: 10.1177/1043454217712983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ginex P, Montefusco M, Zecco G, et al. Animal-facilitated therapy program: outcomes from caring canines, a program for patients and staff on an inpatient surgical oncology unit. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22:193-198. doi: 10.1188/18.CJON.193-198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yom SS. The softer (and furrier) side of oncology. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6:285-286. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McCullough A, Ruehrdanz A, Jenkins MA, et al. Measuring the effects of an animal-assisted intervention for pediatric oncology patients and their parents: a multisite randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2018;35:159-177. doi: 10.1177/1043454217748586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McCullough A. Social Support and Affectionate Commu-nication in Animal-Assisted Interventions: Toward a Typology and Rating Scheme of Handler/Dog Messages [dissertation]. University of Denver; 2014. Accessed July 6, 2020 https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/417 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine Roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2010;42:1409-1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Barbaric M, Brooks E, Moore L, Cheifetz O. Effects of physical activity on cancer survival: a systematic review. Physiother Can. 2010;62:25-34. doi: 10.3138/physio.62.1.25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Beasley JM, Kwan ML, Chen WY, et al. Meeting the physical activity guidelines and survival after breast cancer: findings from the after breast cancer pooling project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131:637-643. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1770-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Caprilli S, Messeri A. Animal-assisted activity at A. Meyer Children’s Hospital: a pilot study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3:379-383. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kaminski M, Pellino T, Wish J. Play and pets: the physical and emotional impact of child-life and pet therapy on hospitalized children. Child Health Care. 2002;31:321-335. doi: 10.1207/S15326888CHC3104_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cerulli C, Minganti C, De Santis C, Tranchita E, Quaranta F, Parisi A. Therapeutic horseback riding in breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:623-629. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dembicki D, Anderson J. Pet ownership may be a factor in improved health of the elderly. J Nutr Elder. 1996;15:15-31. doi: 10.1300/J052v15n03_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bauman AE, Russell SJ, Furber SE, Dobson AJ. The epidemiology of dog walking: an unmet need for human and canine health. Med J Aust. 2001;175:632-634. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143757.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anderson WP, Reid CM, Jennings GL. Pet ownership and risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Med J Aust. 1992;157:298-301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kaiser L, Spence LJ, McGavin L, Struble L, Keilman L. A dog and a “happy person” visit nursing home residents. West J Nurs Res. 2002;24:671-683. doi: 10.1177/019394502320555412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Walsh F. Human-animal bonds II: the role of pets in family systems and family therapy. Fam Process. 2009;48:481-499. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2009.01297.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. McNicholas J, Collis G. Animals as social supports: insights for understanding animal-assisted therapy. In: Fine AH. ed. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2006:49-71. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vormbrock JK, Grossberg JM. Cardiovascular effects of human-pet dog interactions. J Behav Med. 1988;11:509-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Friedmann E, Katcher AH, Lynch JJ, Thomas SA. Animal companions and one-year survival of patients after discharge from a coronary care unit. Public Health Rep. 1980;95:307-312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Odendaal JSJ, Meintjes RA. Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs. Vet J. 2003;165:296-301. doi: 10.1016/S1090-0233(02)00237-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Charnetski CJ, Riggers S, Brennan FX. Effect of petting a dog on immune system function. Psychol Rep. 2004;95(3 pt 2):1087-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barker SB, Knisely JS, McCain NL, Best AM. Measuring stress and immune response in healthcare professionals following interaction with a therapy dog: a pilot study. Psychol Rep. 2005;96(3 pt 1):713-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. McCullough A, Jenkins MA, Ruehrdanz A, et al. Physiological and behavioral effects of animal-assisted interventions on therapy dogs in pediatric oncology settings. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2018;200:86-95. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2017.11.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wood L, Giles-Corti B, Bulsara M. The pet connection: pets as a conduit for social capital? Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:1159-1173. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rogers J, Hart LA, Boltz RP. The role of pet dogs in casual conversations of elderly adults. J Soc Psychol. 1993;133:265-277. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1993.9712145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kellert SR, Wilson EO. The Biophilia Hypothesis. Island Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yin J, Arfaei N, MacNaughton P, Catalano PJ, Allen JG, Spengler JD. Effects of biophilic interventions in office on stress reaction and cognitive function: a randomized crossover study in virtual reality. Indoor Air. 2019;29:1028-1039. doi: 10.1111/ina.12593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Chang CC, Cheng GJY, Nghiem TPL, et al. Social media, nature, and life satisfaction: global evidence of the biophilia hypothesis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4125. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60902-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fine AH. The role of therapy and service animals in the lives of persons with disabilities. Rev Sci Tech. 2018;37:141-149. doi: 10.20506/rst.37.1.2747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Coakley AB, Mahoney EK. Creating a therapeutic and healing environment with a pet therapy program. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2009;15:141-146. doi: 10.1016/J.CTCP.2009.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kumasaka T, Masu H, Kataoka M, Numao A. Changes in patient mood through animal-assisted activities in a palliative care unit. Int Med J. 2012;19:373-377. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310-357. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Helgeson VS. Social support and quality of life. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(suppl 1):25-31. doi: 10.1023/A:1023509117524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Ibarra-Rovillard MS, Kuiper NA. Social support and social negativity findings in depression: perceived responsiveness to basic psychological needs. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:342-352. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wells DL. The effects of animals on human health and well-being. J Soc Issues. 2009;65:523-543. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Beetz A, Kotrschal K, Turner DC, Hediger K, Uvnäs-Moberg K, Julius H. The effect of a real dog, toy dog and friendly person on insecurely attached children during a stressful task: an exploratory study. Anthrozoos. 2011;24:349-368. doi: 10.2752/175303711X13159027359746 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ritchie MA. Sources of emotional support for adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2001;18:105-110. doi: 10.1177/104345420101800303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Woodgate RL. The importance of being there: perspectives of social support by adolescents with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2006;23:122-134. doi: 10.1177/1043454206287396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Horowitz S. The human-animal bond: health implications across the lifespan. Altern Complement Ther. 2008;14:251-256. doi: 10.1089/act.2008.14505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Marcus DA, Blazek-O’Neill B, Kopar JL. Symptom reduction identified after offering animal-assisted activity at a cancer infusion center. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31:420-421. doi: 10.1177/1049909113492373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. White JH, Quinn M, Garland S, et al. Animal-assisted therapy and counseling support for women with breast cancer: an exploration of patient’s perceptions. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14:460-467. doi: 10.1177/1534735415580678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]