Abstract

Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) is caused by a mutant biotype of the feline enteric coronavirus. The resulting FIP virus (FIPV) commonly causes central nervous system (CNS) and ocular pathology in cases of noneffusive disease. Over 95% of cats with FIP will succumb to disease in days to months after diagnosis despite a variety of historically used treatments. Recently developed antiviral drugs have shown promise in treatment of nonneurological FIP, but data from neurological FIP cases are limited. Four cases of naturally occurring FIP with CNS involvement were treated with the antiviral nucleoside analogue GS‐441524 (5‐10 mg/kg) for at least 12 weeks. Cats were monitored serially with physical, neurologic, and ophthalmic examinations. One cat had serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis (including feline coronavirus [FCoV]) titers and FCoV reverse transcriptase [RT]‐PCR) and serial ocular imaging using Fourier‐domain optical coherence tomography (FD‐OCT) and in vivo confocal microscopy (IVCM). All cats had a positive response to treatment. Three cats are alive off treatment (528, 516, and 354 days after treatment initiation) with normal physical and neurologic examinations. One cat was euthanized 216 days after treatment initiation following relapses after primary and secondary treatment. In 1 case, resolution of disease was defined based on normalization of MRI and CSF findings and resolution of cranial and caudal segment disease with ocular imaging. Treatment with GS‐441524 shows clinical efficacy and may result in clearance and long‐term resolution of neurological FIP. Dosages required for CNS disease may be higher than those used for nonneurological FIP.

Keywords: antiviral, cat, corona virus, ophthalmology

Abbreviations

- AG

albumin:globulin

- CNS

central nervous system

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- ELISA

enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay

- FCoV

feline coronavirus

- FD‐OCT

Fourier‐domain optical coherence tomography

- FeLV

feline leukemia virus

- FIP

feline infectious peritonitis

- FIPV

feline infectious peritonitis virus

- FIV

feline immunodeficiency virus

- HIV

human immunedeficiency virus

- IFA

indirect immunofluorescence assay

- IgG

immunoglobulin G

- IgM

immunoglobulin M

- IVCM

in vivo confocal microscopy

- LM

large mononuclear

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- OD

oculus dexter, right eye

- OS

oculus sinister, left eye

- OU

oculus uterque, both eyes

- PLR

pupillary light reflex

- RT‐PCR

reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- SM

small mononuclear

- TNCC

total nucleated cell count

- TP

total protein

1. INTRODUCTION

Experimental treatments were approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Clinical Trial Review Board of the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, UC Davis. GS‐441524 was provided by Gilead Sciences Inc. (Foster City, California) as previously described. 1 , 2 Clinical diagnosis of FIP was based on a combination of characteristic signalment, history, disease signs, laboratory test results including hyperglobulinemia, decreased albumin: globulin (AG) ratios and FCoV antibody titers (indirect immunofluorescence assay [IFA]), Fuller Laboratories, Fullerton, California) 3 and response to viral‐specific treatment. Feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodefficiency virus (FIV) status were determined for FeLV antigen and FIV antibody by ELISA (IDEXX, Westbrook, Maine). Repeated advanced diagnostic testing including MRI, CSF analysis, CSF FCoV RT‐PCR (Real‐time PCR Research and Diagnostics Core Facility, UC Davis, Davis, California) and serology, FD‐OCT and IVCM were performed in 1 case.

2. CASE 1

A domestic 8‐month‐old castrated male blue seal point Siamese cat obtained as a kitten from a rescue group was presented with a several‐month history of lethargy and decreased appetite and a 1‐month history of progressive pelvic limb ataxia that also was noted on neurological examination. The cat weighed 3.0 kg which was 1 kg less than a female sibling. Serum biochemistry abnormalities included an increased total protein concentration (8.9 g/dL; reference interval, 6.3‐8.8 g/dL) with an AG ratio of 0.53 (albumin, 3.1 g/dL; reference interval, 2.6‐3.9 g/dL; globulin, 5.8 g/dL; reference interval, 3.0‐5.9 g/dL). Tests for FeLV and FIV and Toxoplasma gondii IgM and IgG antibody titers (Protatek, Mesa, Arizona) were negative, and FCoV antibody titer was positive at 1:12 800. Ophthalmic examination identified chorioretinal scars in the tapetal fundus in both eyes (oculus uterque, OU). Abdominal ultrasound examination showed circumferential hyperechoic lines at the renal corticomedullary junctions, linear hyperechoic lines paralleling the luminal surface of the jejunum and ileum and enlarged colic and mesenteric lymph nodes. The cat was treated with 5 mg/kg GS‐441524 SC once daily for 14 weeks. Appetite and activity, including jumping onto elevated surfaces increased within 4 days. Serum total protein concentration at cessation of treatment was 7.8 g/dL with an AG ratio of 0.77. Neurological examination was normal and body weight was 5.1 kg. The cat remains clinically normal at the time of writing, 528 days after initiation of treatment.

3. CASE 2

A 1‐year‐old castrated male domestic shorthair cat born to a rescued feral cat presented with a 3‐month history of anterior uveitis and a 1‐week history of lethargy, altered behavior, twitching of the tail, generalized seizures, decreased appetite and dysphagia, and pelvic limb ataxia. The cat weighed 3.7 kg. On neurological examination, the cat was obtunded with generalized ataxia, decreased postural reactions in the left thoracic and right pelvic limbs, decreased physiological nystagmus OU and decreased nasal sensation on the right side. Menace response was decreased OU and anisocoria (mydriasis in the left eye [oculus sinister, OS]) with decreased direct and consensual pupillary light reflex (PLR) with illumination of OS was present. Ophthalmic examination disclosed anterior uveitis OU with retinal detachment OS and retinal vasculitis OU. The cat weighed 3.7 kg and serum biochemistry abnormalities included increased total protein concentration (8.6 g/dL; reference interval, 6.6‐8.4 g/dL) with an AG ratio of 0.48 (albumin, 2.8 g/dL; reference interval, 2.2‐4.6 g/dL; globulin, 5.8 g/dL; reference interval, 2.8‐5.4 g/dL), increased total bilirubin concentration (1.8 mg/dL; reference interval, 0.0‐0.2 mg/dL) and increased AST activity (128 IU/L; reference interval, 17‐58 IU/L). Feline leukemia virus, FIV and heartworm antigen testing (SNAP Feline Triple Test, IDEXX, Westbrook, Minnesota) was negative. Mesenteric lymph nodes were enlarged based on abdominal palpation. The cat was treated with 5 mg/kg GS‐441524 SC, once daily for 14 weeks. Body weight at cessation of treatment was 5.9 kg. Mentation level and activity were markedly improved 48 hours after initiation of treatment. After 3 weeks of treatment, neurological and ophthalmic examinations were unremarkable other than mild intermittent anisocoria and chorioretinal scars OU. Previously noted serum biochemistry abnormalities had resolved with a total serum protein concentration of 8.1 g/dL and an AG ratio of 0.77. Three weeks after cessation of treatment, the cat weighed 6.4 kg, physical and neurological examinations were unremarkable, and serum total protein concentration was 7.0 mg/dL with an AG ratio of 0.84. The cat remains clinically normal at the time of writing, 516 days after initiation of treatment.

4. CASE 3

An 18‐month‐old spayed female domestic shorthair cat, obtained from an animal shelter, presented with a 3‐month history of ocular disease, a 3‐week progressive history of lethargy and inappetence and a several‐day history of progressive pelvic limb paresis. The cat was treated with prednisolone acetate 1% eye drops OU, q6h for 5 days before presentation. On neurological examination, the cat had inappropriate behavior and hypersensitivity to cranial palpation. The cat was nonambulatory paraparetic with decreased pelvic limb reflexes. Menace response was absent OU with anisocoria (mid‐range pupil in the right eye [oculus dexter, OD], mydriasis OS). Pupillary light reflexes were absent OD because of posterior synechiae, and absent OS with direct or indirect illumination. Dazzle reflexes and vision were present OU and the cat appeared to have vision under photopic conditions. Ophthalmic examination was consistent with uveitis and hyperviscosity syndrome OU. The cat weighed 2.6 kg. Serum biochemistry abnormalities included an increased total protein concentration (11.7 g/dL; reference interval, 6.3‐8.8 g/dL) with an AG ratio of 0.2 (albumin, 2.0 g/dL; reference interval, 2.6‐3.9 g/dL; globulin, 9.7 g/dL; reference interval, 3.0‐5.9 g/dL). Tests for FeLV and FIV were negative, and FCoV antibody titer was positive at 1:6400. Abdominal ultrasound examination showed hepatosplenomegaly, small kidneys with indistinct corticomedullary junctions and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes. The cat was treated with 5 mg/kg GS‐441524 SC, once daily for 15 weeks. After 1 month of treatment, uveitis was improved but still present, and the cat was ambulatory paraparetic with normal segmental reflexes. The cat weighed 3.3 kg and the AG ratio was 0.55. After 2 months of treatment, subtle signs of active anterior uveitis were present OD, but there was only moderate improvement in the ambulatory paraparesis. Body weight had increased to 3.7 kg and the AG ratio was 0.67. After 15 weeks of treatment, there was minimal evidence of uveitis OD and improvement in the ambulatory paraparesis that had been static for the preceding 4 weeks. The cat weighed 4.0 kg and AG ratio was 0.76. After cessation of treatment, lethargy, inappetence, and anisocoria recurred within 36 hours. Treatment was reinstituted with 5 mg/kg GS‐441524 SC, once daily and signs resolved within 24 hours. Signs remained static during the 12 weeks of the second round of treatment, but decreased activity recurred again after cessation of treatment. The cat was euthanized in part because of increased resistance to drug administration. Histopathological assessment after necropsy showed multifocal chronic nonsuppurative meningitis, encephalomyelitis and ventriculitis, lymphocytic, histiocytic uveitis and choroiditis OU and interstitial nephritis. Positive coronavirus immunohistochemical immunoreactivity (FIP‐V3‐70 antibody, Custom Monoclonals International, Sacramento, California) was identified within lesion‐associated histiocytes in the brain, kidney, and eye.

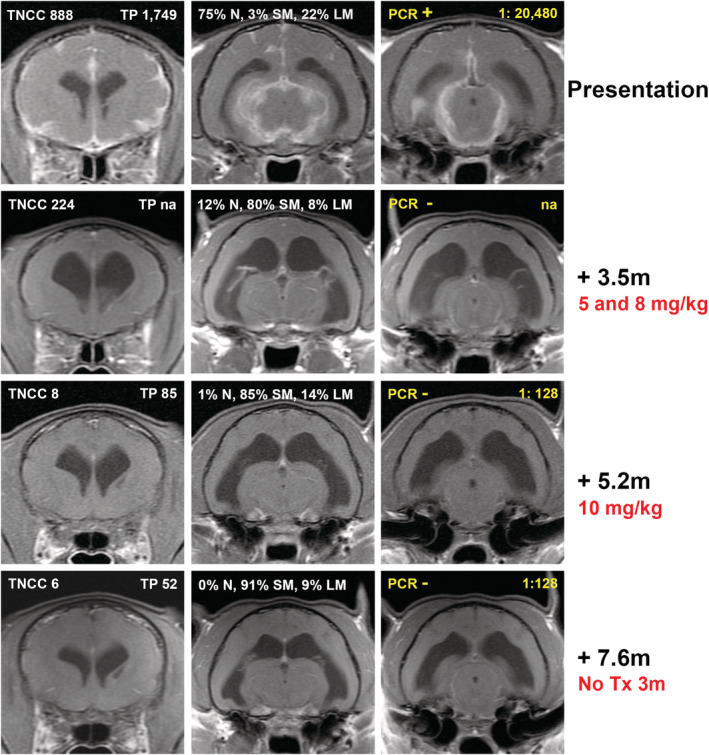

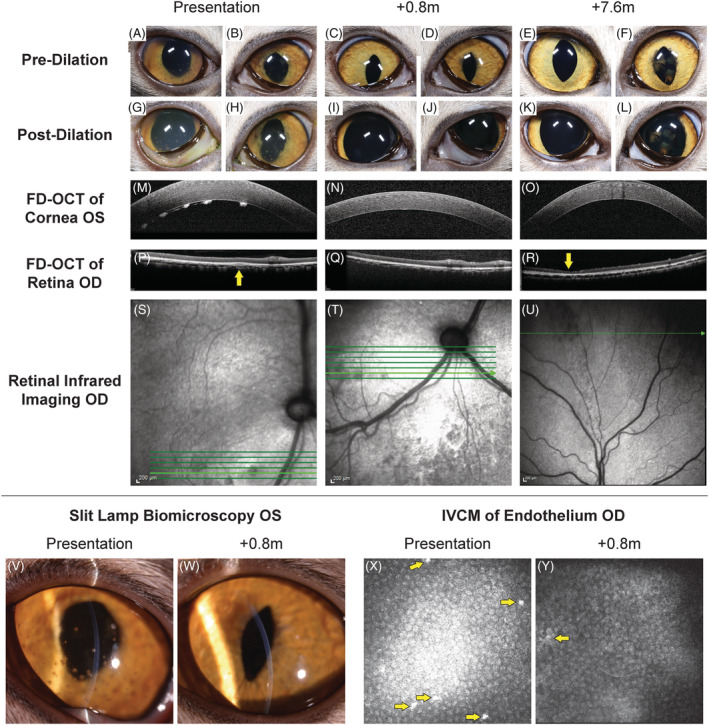

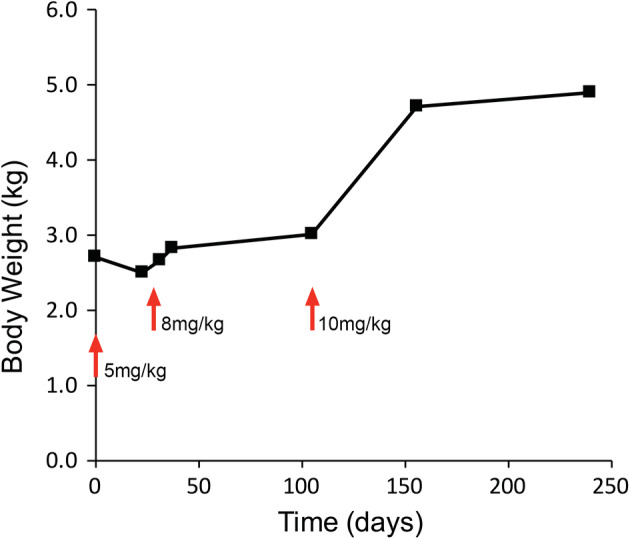

5. CASE 4

A 7‐month‐old spayed female domestic shorthair cat adopted from an animal shelter presented with a 3‐week history of lethargy and inappetence and a 2‐week history of ataxia and crouching gait. On neurological examination the cat had an ataxic gait which was worse in the pelvic limbs. Postural reactions were decreased in the pelvic limbs. Anisocoria (midrange OD, miotic OS) was present with incomplete PLRs OU. Menace responses, dazzle reflexes, and vision were present OU. The cat weighted 2.7 kg. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed multifocal T2‐weighted hyperintensities throughout the parenchyma, most severe in the midbrain and thalamus. Postcontrast T1‐weighted images showed diffuse thickening and enhancement of the meninges of the cerebrum and brainstem, with marked ventriculomegaly (Figure 1). Cerebrospinal fluid collected from the cerebellomedullary cistern was xanthochromic with a total nucleated cell count (TNCC) of 888/μL (reference interval, <3 cells/μL) and a CSF total protein concentration of 1790 mg/dL (reference interval, <25 mg/dL). Serum and CSF FCoV antibody titers both were positive at >1:20 480 and real‐time TaqMan RT‐PCR for FCoV in CSF was positive with a threshold cycle (Ct) value of 18.87. Tests for FeLV and FIV were negative. Serum biochemistry and CBC abnormalities included a total protein concentration of 8.5 g/dL (reference interval, 6.6‐8.4 g/dL), an AG ratio of 0.37 (albumin, 2.3 g/dL; reference interval, 2.2‐4.6 g/dL; globulin, 6.2 g/dL; reference interval, 2.8‐5.4 g/dL), a total bilirubin concentration of 0.5 mg/dL (reference interval, 0.0‐0.2 mg/dL), anemia (hematocrit, 25.8%; reference interval, 30‐50%) and lymphopenia (835/μL; reference interval, 1000‐7000/μL). Abdominal ultrasound examination showed hyperechoic kidneys and retroperitoneal fat, several enlarged lymph nodes and mild peritoneal effusion. On ophthalmic examination, FD‐OCT and IVCM, anterior uveitis was found with keratic precipitates and posterior synechiae present OU; ocular hypertension (25 mmHg OD, 11 mmHg OS) and chorioretinitis also were identified OD (Figure 2). The cat was treated with 5 mg/kg GS‐441524 SC, once daily for 4 weeks and with prednisolone acetate 1% eye drops OU q8h and dorzolamide 2% eye drops OD q8h for the first 3 weeks of GS‐441524 treatment. Activity and mentation improved within 24 hours of treatment. After 4 weeks, ophthalmic disease was markedly improved (Figure 2), but ataxia was still present, and the cat had lost 0.2 kg body weight (Figure 3). Serum total protein concentration was still increased (8.6 g/dL) with an improved AG ratio of 0.72; lymphopenia and anemia had resolved. Because of the lack of weight gain and continued neurological deficits, the GS‐441524 dosage was increased to 8 mg/kg SC, once daily for an additional 10 weeks (14 weeks in total). The cat also was given a 2‐week course of prednisolone 1 mg/kg PO q24h. Increased activity and willingness to jump onto elevated surfaces was seen within 24 hours, and 1 week after cessation of GS‐441524 treatment, neurological examination was unremarkable and no active ophthalmic disease was detected. Body weight had increased to 3 kg and serum total protein concentration was normal (7.6 g/dL) with an AG ratio of 0.8. Repeat MRI (Figure 1) showed minimal meningeal contrast enhancement, but ventriculomegaly had increased. Repeat CSF RT‐PCR for FCoV RNA was negative, and CSF TNCC was decreased from the previous count, but still high at 224/μL. Because of CSF analysis evidence that the infection was still active, GS‐441524 dosage was further increased to 10 mg/kg SC, once daily for an additional 5 weeks (19 weeks in total). The cat remained clinically normal with increased activity over this period and body weight increased to 4.7 kg (Figure 3). Immediately after cessation of treatment, neurological and ophthalmologic examinations remained unchanged, and repeat MRI was unremarkable other than persistent ventriculomegaly. Repeat CSF analysis showed a continued decrease in TNCC (8 cells/μL) and total protein concentration (85 mg/dL), negative RT‐PCR for FCoV RNA and a decreased FCoV antibody titer of 1:128. Approximately 8 months after initiation of treatment, and 3 months after cessation of treatment, MRI was unchanged from the previous imaging other than less severe ventriculomegaly. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed a TNCC of 6 cells/μL, total protein concentration of 52 mg/dL, negative RT‐PCR for FCoV RNA and a static FCoV antibody titer of 1:128. Serum total protein concentration was 7.1 g/dL with an AG ratio of 0.97. On ophthalmic examination, no signs of active inflammation were observed although focal regions of retinal thinning were identified. The cat remains clinically normal at the time of writing, 354 days after initiation of treatment.

FIGURE 1.

Sequential magnetic resonance imaging from Case 4. Rows represent selected postcontrast (gadolinium) T1‐weighted transverse images of the brain acquired in a single imaging sequence. Routine analysis from cerebrospinal fluid analysis at the time of imaging is presented in white for each imaging time point: TNCC = CSF total nucleated cell count (cells/μL); TP = CSF total protein (mg/dL); N = neutrophils, SM = small mononuclear, LM = large mononuclear. Characteristic neutrophilic pleocytosis resolved over the course of the treatment. Additional CSF analyses relating to FCoV detection are presented in yellow for each time point: PCR = FCoV RT‐PCR result [positive (+) or negative (−)]; Dilution ratio = cerebrospinal fluid FCoV antibody titer. Time points and doses of GS‐1441524 delivered before imaging time points are described for each imaging sequence. Initial pronounced meningeal contrast enhancement resolves after GS‐144524 treatment and does not recur after cessation of treatment. Ventriculomegaly that is present after initial response to treatment, resolved slowly on subsequent imaging. Decreasing abnormalities in CSF analysis findings paralleled decreased abnormalities on MR imaging

FIGURE 2.

Sequential multimodal imaging of the cranial and caudal segments from Case 4. At presentation (A, B) predilatation and (G, H) postdilatation cranial segment photographs showing mild diffuse corneal edema, pigmented keratic precipitates, rubeosis iridis, obscured detail of the iris because of aqueous flare, and incomplete dilatation OU; dyscoria with incomplete pupillary dilatation because of caudal synechia OS (H) was also observed. Keratic precipitates were also visualized OS with slit lamp biomicroscopy (V), corneal FD‐OCT (M), and IVCM of the endothelium (X, arrows); increased corneal thickness was also observed with FD‐OCT (X). Imaging of the retina and choroid with FD‐OCT revealed cellular infiltrate in the choroid (P, arrow) that was visible as a hyporeflective lesion with infrared photography (S). At 0.8 months after initiation of GS‐441524 treatment, pre‐ (C,D) and postdilatation (I,J) cranial segment photographs demonstrated clear corneas and cranial chambers OU, isocoria, decreased rubeosis iridis, and complete pupillary dilatation OS. A marked decrease in pigmented keratic precipitates was noted with slit lamp biomicroscopy (W), corneal FD‐OCT (N), and IVCM of the endothelium (Y, arrow). Normal retinal and choroidal morphology is observed with FD‐OCT (Q) although the hyporeflective lesions remain with infrared imaging (T). At 7.6 months, pre‐ (E,F) and postdilatation (K, L) cranial segment photographs demonstrated clear corneas and cranial chambers OU, isocoria, normal iris morphology, and postinflammatory pigment on the cranial lens capsule OS. Keratic precipitates are absent with corneal FD‐OCT (O). With FD‐OCT and infrared imaging, thinning of the dorsal peripheral retina was present (R, arrow) with loss of the normal layering but no cellular infiltrate or retinal separation (U)

FIGURE 3.

Case 4 body weight plotted with respect to time postinitiation of GS‐1441524 treatment. Changes in drug dose are marked with red arrows. Increased body weight was seen after increases in drug dose beyond initial 5 mg/kg dose, and was accompanied by resolution of clinical signs

6. DISCUSSION

Feline infectious peritonitis is a major cause of mortality in young cats and a common cause of neurological disease. 3 , 4 Several experimental treatments have failed to show consistent efficacy against FIP, and cats are euthanized or die in days to months after development of clinical disease, particularly with FIP affecting the CNS. 4 Fortunately, drugs targeting RNA viral replication in important diseases of human such as human immunedeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis C, and Ebola have provided a model for treatment of viral diseases in other species such as FIP. GS‐441524 is a 1′‐cyano‐substituted adenine C‐nucleoside ribose analogue that inhibits viral RNA synthesis. 1 GS‐441524 and a previously reported 3C‐like antiviral protease inhibitor 5 have been shown to have efficacy against the FIPV in experimental and naturally acquired FIP. 1 , 2 , 5 , 6 However, preliminary studies suggested that treatment of ocular and CNS forms of FIP may be more difficult because of limited drug access through the blood‐ocular and blood‐brain barriers. 1 , 2 , 5 , 6 High rates of FIP disease relapse involving the CNS were reported with protease inhibitor‐based treatment, 5 whereas more hope was given to GS‐441524 treatment of ocular and neurological FIP. The initial field trial of GS‐441524 in naturally acquired, nonneurological FIP used doses of 2 mg/kg that appeared to be insufficient for cats that developed neurological signs during the course of treatment. 2 However, 2 cats that developed neurological disease at this dose appeared to respond to 4 mg/kg. Our study of 4 cases of neurological FIP were treated using a dose of 5 mg/kg, with treatment duration and subsequent dose increases based on clinical responses. A dosage of 5 mg/kg, SC, once daily for 12 to 14 weeks was sufficient to treat 2 less severely affected neurological FIP cases (Cases 1, 2), but repeated courses at a 5 mg/kg dose in the most severely clinically affected cat (Case 3) only resulted in amelioration of clinical signs, with rapid clinical regression once treatment was stopped. This therapeutic failure prompted stepwise dose escalation from 5 to 10 mg/kg in Case 4. In vitro 50% effective concentration (EC50) for GS‐441524 to prevent viral cytopathic effects was reported at 0.8 μM, with complete inhibition of viral replication at 10 μM and partial inhibition at 1 μM. 1 Limited pharmacokinetic studies in cats from the same study showed that concentrations of GS‐441524 in CSF were approximately 20% that of plasma, and a 10 mg/kg dose resulted in CSF concentrations of 0.8 to 2.7 μM. These data are consistent with the limited efficacy associated with the 5 mg/kg doses in Cases 3 and 4 and the apparent efficacy associated with dose escalation to 8 to 10 mg/kg in Case 4. Expanded pharmacokinetic studies in healthy and affected cats with intact and compromised blood‐brain barrier function will be necessary to further define the optimal dosage of GS‐441524 in cats with neurological FIP. Similar to previous reports, 1 , 2 adverse events associated with prolonged use of GS‐441524 were limited. Local skin reactions and discomfort after SC injection were the only clinically relevant adverse events, but this was a major factor influencing the decision to euthanize Case 3. Although treatment responses were measurable by MRI, CSF analysis, and ocular imaging, the clinical response to treatment when appropriate dosages were used was equally useful, with rapid improvement in mentation, appetite and activity generally observed within 24 to 36 hours. Increased body weight and ability to jump onto elevated objects and surfaces also were seen as consistent indicators of effective treatment. GS‐441524 is not available for routine clinical use, but the reported cases suggest that FIP affecting the CNS may be treatable using appropriate antiviral medications. Development of similar antiviral drugs for clinical application should be seen as a priority for this historically fatal disease.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DECLARATION

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

OFF‐LABEL ANTIMICROBIAL DECLARATION

Authors declare no off‐label use of antimicrobials.

INSTITUTIONAL ANIMAL CARE AND USE COMMITTEE (IACUC) OR OTHER APPROVAL DECLARATION

Experimental treatments were conducted under protocols 19336 and 19863 approved by the UC Davis Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Clinical Trial Review Board of the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, UC Davis.

HUMAN ETHICS APPROVAL DECLARATION

Authors declare human ethics approval was not needed for this study.

Dickinson PJ, Bannasch M, Thomasy SM, et al. Antiviral treatment using the adenosine nucleoside analogue GS‐441524 in cats with clinically diagnosed neurological feline infectious peritonitis. J Vet Intern Med. 2020;34:1587–1593. 10.1111/jvim.15780

[Correction added on 15 July 2020 after first online publication: the terminologies anterior uveitis and posterior synechiae were updated.]

Funding information Center for Companion Animal Health (CCAH), University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine; SOCK FIP

REFERENCES

- 1. Murphy BG, Perron M, Murakami E, et al. The nucleoside analog GS‐441524 strongly inhibits feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) virus in tissue culture and experimental cat infection studies. Vet Microbiol. 2018;219:226‐233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pedersen NC, Perron M, Bannasch M, et al. Efficacy and safety of the nucleoside analog GS‐441524 for treatment of cats with naturally occurring feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg. 2019;21:271‐281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pedersen NC. An update on feline infectious peritonitis: diagnostics and therapeutics. Vet J. 2014;201:133‐141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pedersen NC. A review of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection: 1963‐2008. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11:225‐258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pedersen NC, Kim Y, Liu H, et al. Efficacy of a 3C‐like protease inhibitor in treating various forms of acquired feline infectious peritonitis. J Feline Med Surg. 2018;20:378‐392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim Y, Liu H, Galasiti Kankanamalage AC, et al. Reversal of the progression of fatal coronavirus infection in cats by a broad‐Spectrum coronavirus protease inhibitor. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]