Abstract

For mixture separations, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are of practical interest. Such separations are carried out in fixed bed adsorption devices that are commonly operated in a transient mode, utilizing the pressure swing adsorption (PSA) technology, consisting of adsorption and desorption cycles. The primary objective of this article is to provide an assessment of the variety of metrics that are appropriate for screening and ranking MOFs for use in fixed bed adsorbers. By detailed analysis of several mixture separations of industrial significance, it is demonstrated that besides the adsorption selectivity, the performance of a specific MOF in PSA separation technologies is also dictated by a number of factors that include uptake capacities, intracrystalline diffusion influences, and regenerability. Low uptake capacities often reduce the efficacy of separations of MOFs with high selectivities. A combined selectivity–capacity metric, Δq, termed as the separation potential and calculable from ideal adsorbed solution theory, quantifies the maximum productivity of a component that can be recovered in either the adsorption or desorption cycle of transient fixed bed operations. As a result of intracrystalline diffusion limitations, the transient breakthroughs have distended characteristics, leading to diminished productivities in a number of cases. This article also highlights the possibility of harnessing intracrystalline diffusion limitations to reverse the adsorption selectivity; this strategy is useful for selective capture of nitrogen from natural gas.

1. Introduction

During the last 2 decades, there has been a substantial increase in the development and synthesis of novel microporous crystalline materials for use as selective adsorbents in a variety of industrially important separation applications; examples of such materials include metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), porous organic cages, porous aromatic frameworks, covalent organic frameworks, and polymers with intrinsic microporosity. Such separations are normally carried out in fixed bed devices that are operated in a transient mode, consisting of adsorption and desorption cycles. In one class of applications, the motivation has been to afford energy-efficient and environmentally benign alternatives to conventional separations such as absorption, distillation, extraction, or crystallization. In other cases, there are incentives for enhancing the separation performance by replacing the currently used microporous adsorbents such as cation-exchanged zeolites and activated carbon (AC) with tailor-made MOFs. To set the scene and define the objectives of this article, we consider a number of mixture separations that may be targeted for the development of novel MOFs.

Arguably, the most important and successful industrial application of adsorption separations is for H2 purification. The catalytic reforming of natural gas, when combined with a water gas shift reaction step, yields a hydrogen-rich product stream containing a number of impurities such as H2O vapor, CO2, CH4, CO, and N2.1−3 These impurities must be removed in order to attain the 99.95%+ H2 purity that is normally demanded.1 In fuel cell applications, the purity demands are as high as 99.99%+.2,4 Large-scale production of hydrogen, with the desired purity, is carried out in pressure swing adsorption (PSA) units that are operated at pressures reaching about 7 MPa using the Skarstrom cycle, involving multiple steps or stages; see the schematic in Figure 1. In the simplest case, the four steps in the sequence are as follows.5−7

-

(a)

Pressurization (with the feed or raffinate product)

-

(b)

High-pressure adsorption separation with the feed, with withdrawal of the purified raffinate product

-

(c)

Depressurization, or “blowdown”, countercurrent to the feed

-

(d)

Desorption at the lower operating pressure. This is accomplished by evacuation or purging the bed with a portion of the purified raffinate product.

Figure 1.

Sequential steps in the operation of a fixed bed adsorber in the Skarstrom cycle for H2 purification.2,5−7

The use of layered beds, consisting of three different adsorbents, is an important characteristic of the currently employed PSA technology for H2 purification.2,8 In order to rationalize and understand the use of multilayer adsorbent beds, Figure 2a,b presents simulations of transient breakthroughs of 73/4/3/4/16 H2/N2/CO/CH4/CO2 mixture, typical of steam methane reformer off-gas,3 in fixed bed adsorbers packed with (a) AC and (b) LTA-5A zeolite8−10 operating at 2 MPa total pressure and temperature T = 313 K. Purified H2 can be recovered during the time intervals between the breakthroughs of H2 and N2, as indicated by the arrows. The stronger binding of N2 in LTA-5A, as compared to AC, is due to the contribution of the quadrupole moment of N2 and its interaction with the charges of extraframework cations Na+ and Ca2+.5,11 The quadrupole moment of CO2 also leads to stronger binding in LTA-5A, causing significantly higher CO2 capture capacity, as evidenced by the strongly delayed breakthrough of CO2 with LTA-5A as compared to AC.5,11 The strong binding of CO2 in LTA-5A is disadvantageous because deep vacuum will be required to reduce the CO2 loading to the desired level during the purge step (d) in Figure 1. Consequently, despite the superior separation performance of LTA-5A, resulting in higher productivity of pure H2 per kilogram of adsorbent, LTA-5A is not used on its own in the currently used PSA schemes.2,3 Commonly, the first layer is either alumina or silica that retains the water vapor. Then, an AC layer is used to selectively adsorb CO2. The main task of the alumina and AC layers is to prevent the H2O vapor and CO2 from reaching the zeolite layer.2 The last layer is a cation-exchanged zeolite [such as LTA-5A, and NaX (=13X),12 with Na+ cations] with enhanced capacity for CO and N2. For H2 purification applications,3,13−15 it is evident that CO2/H2 adsorption selectivity is not the “key” determinant of the achieved purity of H2.

Figure 2.

Transient breakthrough of 73/4/3/4/16 H2/N2/CO/CH4/CO2 mixtures in a fixed bed adsorber packed with (a) AC and (b) LTA-5A zeolite operating at a total pressure of 2 MPa and T = 313 K. For presenting the breakthrough simulation results, we use as x-axis the dimensionless time, τ = tv/L, where L is the length of the adsorber and v is the interstitial gas velocity.63,122 Further information on input data and simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

For CO2 capture from flue gases from power plants, and from natural gas streams, MOFs offer energy-efficient alternatives to conventionally used amine absorption technologies.16−21 In CO2/flue gas and CO2/natural gas separations, the process economics would demand high CO2 capture capacity and concomitant ease of regeneration.22

For the production of alkene feedstocks of 99.95%+ purity required for polymerization reactors, cryogenic distillation columns, operated at high pressures and high reflux ratios, are commonly employed for large-scale separations of C2H4/C2H6 and C3H6/C3H8 mixtures. Many MOF developments have targeted alkene/alkane separations with the objective of eventually supplanting the energy-intensive distillation technologies.23−29 Process economics would also demand high alkene productivities per kilogram adsorbent.

In steam cracking of ethane to produce ethene (C2H4), one of the byproducts is ethyne (C2H2). Typically, the C2H2 content of C2H2/C2H4 feed mixtures is 1%. Ethyne has a deleterious effect on the polymer products of ethene, such as polyethene. The impurity level of C2H2 in the C2H4 feed streams should be below 40 ppm in order to prevent the poisoning of catalysts used in the polymerization of C2H4. MOFs offer potential improvements to absorption technologies using dimethyl formamide as a solvent.23,30−37 For 1/99 C2H2/C2H4 mixture separations, we would require that the MOF would have high productivity of pure alkene (<40 ppm C2H2) per kilogram of adsorbent.

Ethyne (C2H2) is an important building block in industrial chemical synthesis and is also widely used as a fuel in welding equipment. C2H2 is commonly manufactured by the partial combustion of CH4 or comes from cracking of hydrocarbons. In the reactor product, C2H2 coexists with CO2 or C2H4. Because of the similarity of molecular sizes and shapes (C2H2: 3.32 × 3.34 × 5.7 Å3 and CO2: 3.18 × 3.33 × 5.36 Å3), the separation of C2H2/CO2 mixtures is particularly challenging.38,39 Because the boiling points of C2H2 (189.3 K) and CO2 (194.7 K) are close, distillation separations need to operate at cryogenic temperatures and high pressures. A number of recently developed MOFs offer the potential of use in adsorptive separations of C2H2/CO2 mixtures.40−53

The selective capture of CO2 from the reactor effluents from the process for oxidative coupling of methane essentially requires for CO2-selective separation of CO2/CH4/C2H4/C2H6 mixtures; the number of candidate adsorbent materials is surprisingly limited.54−56

Noble gases such as He, Ne, Ar, Kr, and Xe find a variety of applications.57 For example, heliox (a mixture of He and O2) is used for patients with respiratory difficulties and in deep-sea diving,58 Ne is used in the familiar “neon sign” for advertisements. Kr and Xe are used in flash bulbs and lasers. Ar is used in filament bulbs and in electric arc welding as a shielding gas. Based on the differences in the boiling points, Ne (27 K), Ar (87 K), Kr (120 K), and Xe (165 K) are commercially produced by liquefaction of air, followed by cryogenic distillation. Alternatively, adsorptive separations, relying essentially on the differences in polarizabilities (cf. Figure 3), are realizable with a number of MOFs.57,59,60

Figure 3.

Boiling points and polarizabilities of noble gases culled from web sources.

The process demands in each of the aforementioned examples of mixture separations are different. The primary objective of this article is to provide a comparative assessment of the variety of metrics that are appropriate for screening and ranking candidate MOFs that are appropriate for the specific separation task in hand. The Supporting Information provides detailed structural information on the MOFs investigated, along with a detailed description of the methodology used for transient breakthrough simulations. For each of the chosen mixtures, the comparisons of the separation performance of various MOFs are on the basis of experimental data on the unary isotherms from published sources; the data sources are provided in the Supporting Information.

2. Adsorption Selectivities, Uptake Capacities, and Transient Breakthroughs

2.1. Xe/Kr Separations

To develop an understanding of the various metrics that determine the effectiveness of separations, let us consider the separation of 20/80 Xe(1)/Kr(2) mixtures in a fixed bed packed with CoFormate (=Co3(HCOO)6); the objective is to produce Kr with less than say 1000 ppm Xe. Because of the commensurate positioning of Xe within its cages, CoFormate displays high Xe/Kr selectivity.61 The continuous solid lines in Figure 4 represent transient breakthrough simulation results for the dimensionless concentrations ci/ci0 at the exit of the fixed bed. The breakthroughs have distended characteristics that are caused by intracrystalline diffusional limitations. For subsequent discussions, it is useful to also consider the limiting scenario in which the concentration fronts traverse the fixed bed in the form of shock waves;62,63 the shock wave model approximation is shown by the dotted lines in Figure 4; further details of the shock wave model are provided in the Supporting Information. Because the shock wave model has sharp fronts, the separation performance is the maximum achievable, and this simplified model helps to derive simple expressions for the metrics that describe the performance of fixed bed adsorbers.

Figure 4.

Transient breakthrough simulations (indicated by the solid blue line) for separation of 20/80 Xe/Kr mixtures at 298 K and 100 kPa in a fixed bed packed with CoFormate; these simulations include intracrystalline diffusion limitations. The dotted lines represent the shock wave model approximation.63 The input data and calculation details are available in earlier works.57,63,121

In the shock wave model, the traversal velocity for the more strongly adsorbed Xe is significantly lower than that of the poorly adsorbed Kr.6,7 The Xe capture capacity of CoFormate, q1, expressed as moles captured per kilogram of adsorbent in the fixed bed can be calculated from a material balance

| 1 |

In eq 1, y10 is the mole fraction of Xe at the inlet to the bed, Q0 is the volumetric flow of the feed gas mixture with total molar concentration, ct = pt/RT, t1 is the breakthrough time for Xe, and mads is the mass of the adsorbent. We define the displacement time interval Δt = t1 – t2 as the difference between the breakthrough times of Xe(1) and Kr(2); during this interval, pure Kr can be recovered. The productivity of purified Kr, Δq, that is collected during the displacement interval can be determined from the shock wave model63

| 2 |

where q2 is the uptake of Kr in the bed

| 3 |

Because its derivation is based on the idealized shock wave model, the quantity Δq, dubbed the separation potential, represents the maximum productivity of the less strongly adsorbed component that can be recovered.

The adsorption selectivity, Sads, defined by

| 4 |

can be related to the breakthrough times by combining eqs 1–4

| 5 |

Increasing values of adsorption selectivities, Sads, results in an increase in the values of Δt/t1 and  . This implies that as the selectivity increases,

the breakthrough of Kr occurs increasingly earlier

. This implies that as the selectivity increases,

the breakthrough of Kr occurs increasingly earlier

| 6 |

Although

a high value of Sads is always

a desirable characteristic, this metric does not guarantee a high

productivity of pure Kr that is required of the “best”

MOF. The highest productivity of Kr will be offered by the MOF that

has the highest value of separation potential Δq = q1y20/y10 – q2,

which should be regarded as a combined selectivity–capacity

metric.63 In order to underscore this observation, Figure 5a,b presents the

ideal adsorbed solution theory64 (IAST)

calculations of (a) component loadings q2 versus q1 and (b) separation potential  versus adsorption selectivity Sads for

adsorption of 20/80 Xe(1)/Kr(2) mixtures in NiMOF-74,65,66 Ag@NiMOF-74,66 CuBTC,65,67 SBMOF-2,59 CoFormate,61 and SAPO-34.60 The MOF with

the highest value of Sads is CoFormate;

however, the highest Δq is achieved by Ag@NiMOF-74.

The presence of well-dispersed Ag nanoparticles in Ag@NiMOF-74 causes

stronger van der Waals interactions of the polarizable Xe atoms; this

results in the higher uptakes and the highest Δq.

versus adsorption selectivity Sads for

adsorption of 20/80 Xe(1)/Kr(2) mixtures in NiMOF-74,65,66 Ag@NiMOF-74,66 CuBTC,65,67 SBMOF-2,59 CoFormate,61 and SAPO-34.60 The MOF with

the highest value of Sads is CoFormate;

however, the highest Δq is achieved by Ag@NiMOF-74.

The presence of well-dispersed Ag nanoparticles in Ag@NiMOF-74 causes

stronger van der Waals interactions of the polarizable Xe atoms; this

results in the higher uptakes and the highest Δq.

Figure 5.

IAST calculations of (a) component loadings q2 vs q1 and (b) separation potential  vs adsorption selectivity Sads for 20/80

Xe(1)/Kr(2) mixture adsorption at 298 K

and 100 kPa in six different MOFs: NiMOF-7465,66 Ag@NiMOF-74,66 CuBTC,65,67 SBMOF-2,59 CoFormate61 (=Co3(HCOO)6), and SAPO-34.60 (c) Comparison of the transient breakthrough

simulations for separation of 20/80 Xe/Kr mixtures at 298 K and 100

kPa in fixed beds packed with CoFormate and Ag@NiMOF-74. The dimensionless

concentrations at the exit of the fixed bed are plotted as a function

of Q0t/mads, where Q0 is the volumetric

flow rate of the gas mixture at the inlet to the fixed bed, expressed

in L s–1, at STP conditions. (d) Plot of the productivity

of pure Kr, determined from breakthrough simulations, vs the IAST

calculations of

vs adsorption selectivity Sads for 20/80

Xe(1)/Kr(2) mixture adsorption at 298 K

and 100 kPa in six different MOFs: NiMOF-7465,66 Ag@NiMOF-74,66 CuBTC,65,67 SBMOF-2,59 CoFormate61 (=Co3(HCOO)6), and SAPO-34.60 (c) Comparison of the transient breakthrough

simulations for separation of 20/80 Xe/Kr mixtures at 298 K and 100

kPa in fixed beds packed with CoFormate and Ag@NiMOF-74. The dimensionless

concentrations at the exit of the fixed bed are plotted as a function

of Q0t/mads, where Q0 is the volumetric

flow rate of the gas mixture at the inlet to the fixed bed, expressed

in L s–1, at STP conditions. (d) Plot of the productivity

of pure Kr, determined from breakthrough simulations, vs the IAST

calculations of  for six different MOFs with y10 = 0.2; y20 = 0.8. Further

information on input data and simulation details are provided in earlier

works.57,63,121

for six different MOFs with y10 = 0.2; y20 = 0.8. Further

information on input data and simulation details are provided in earlier

works.57,63,121

Because the productivity of pure Kr, Δq, is proportional to the displacement time interval, Δt = t1 – t2, an alternative procedure for screening MOFs for Xe/Kr separations would be on the basis of the displacement intervals, determined by comparing transient breakthroughs in fixed beds, that are determined from experimental data or transient breakthrough simulations. Figure 5c compares the transient breakthrough simulations for Ag@NiMOF-74 and CoFormate on this basis. The transient breakthrough simulation methodology is described in detail in the Supporting Information. Briefly, the assumptions made in the simulations are as follows: (1) axial dispersion effects are considered to be negligible, (2) the mixture adsorption equilibrium can be described using IAST, (3) the column pressure drop is of negligible importance, and (4) the total pressure remains constant during the operation. Because the breakthrough times are dependent on the mass of the adsorbent, mads, and the volumetric flow rate, Q0, the appropriate comparison of transient breakthroughs for different MOFs is to use the parameter Q0t/mads as the x-axis in place of time; indeed, this parameter may be viewed as a “corrected” time. It is also a common practice to use the value of Q0 at STP conditions. Noteworthily, the breakthroughs of both Ag@NiMOF-74 and CoFormate have distended characteristics. Because of intracrystalline diffusion limitations, the breakthrough characteristics of CoFormate are more distended than that of Ag@NiMOF-74. In the industry, the process requirement would demand the production of Kr containing <1000 ppm Xe. During the displacement intervals indicated by the arrows, the industrial process requirements may be met.57 To determine the actual amount of Kr of desired purity that may be recovered, the total amount of Kr that exits the fixed bed during the displacement interval is determined by sampling of the exit gas from the fixed bed; from such sampling, the productivities of pure Kr are 125 L (STP) kg–1 for Ag@NiMOF-74 and 68 L (STP) kg–1 for CoFormate. Despite having the highest Sads value, the significantly poorer productivity of CoFormate is directly ascribable to its lower uptake capacity (cf. Figure 5a). Figure 5d plots the productivities of pure Kr from transient breakthroughs of six different MOFs as a function of the corresponding IAST calculations of Δq. The near-linear relation between the two sets confirms that IAST calculations of the separation potential Δq may be used for screening purposes. Also shown by the continuous solid line in Figure 5d is the parity line 22.4 × Δq for the productivities. Because of the distended nature of the transient breakthroughs in Figure 5c, the actual productivities are lower than 22.4 × Δq.

The MOF crystallites in the fixed bed at the end of the adsorption cycle are predominantly rich in the more strongly adsorbing Xe. Pure Xe can be recovered during the desorption cycle by the application of deep vacuum. The maximum productivity of pure Xe can also be derived from the use of the shock wave model63

| 7 |

Figure 6 plots the productivities of pure Xe, containing <1000 ppm Kr, from transient desorption simulations using six different MOFs, against the corresponding IAST calculations of Δq, calculated using eq 7 with y10 = 0.2; y20 = 0.8. The relation between the actual productivities (symbols) and Δq is not perfectly linear. For example, the Xe productivity of CoFormate is slightly lower than that of CuBTC, despite the fact that the separation potential Δq of CoFormate is higher than that of CuBTC. IAST calculations of the separation potential Δq, from eq 7, for screening of MOFs will be of inadequate accuracy in cases of strong diffusional influences.

Figure 6.

Plot of the productivity of pure Xe determined

from transient desorption

simulations for 20/80 Xe(1)/Kr(2) mixtures vs the IAST calculations

of separation potential  for six different MOFs with y10 = 0.2; y20 = 0.8. Further

information on input data and simulation details are provided in earlier

works.57,63,121

for six different MOFs with y10 = 0.2; y20 = 0.8. Further

information on input data and simulation details are provided in earlier

works.57,63,121

2.2. C2H2/CO2 Mixture Separations

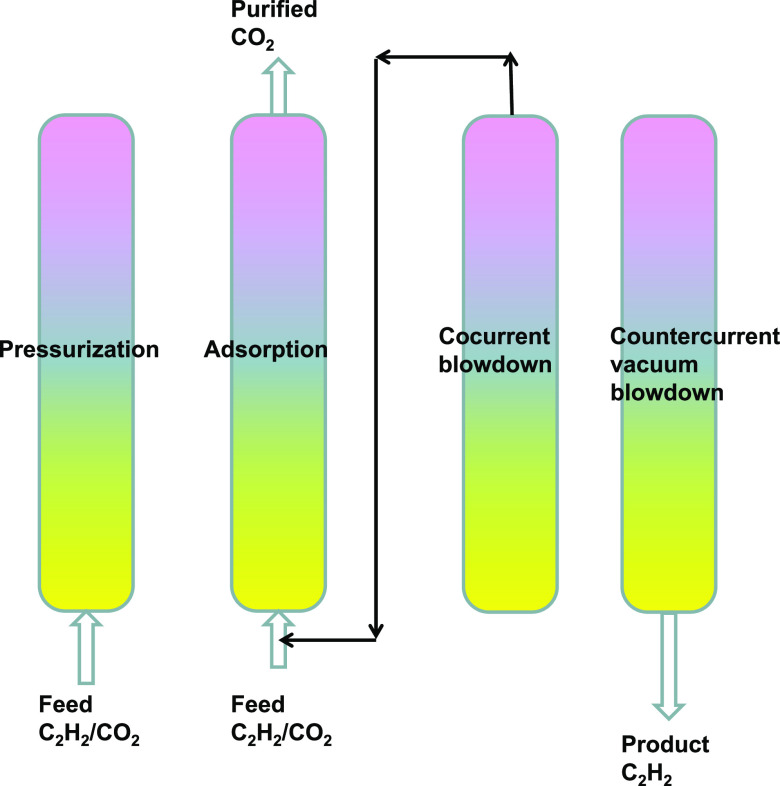

For separation of C2H2(1)/CO2(2) mixtures, most of the suggested MOFs such as PCP-33,47 HOF-3,48 TIFSIX-2-Cu-i,49 JCM-1,50 DICRO-4-Cu-i,51 MUF-17,52 UTSA-74,46 FJU-90,43 and FeNi-M′MOF41 are selective to C2H2. Consequently, the desired ethyne product is available in the blowdown phase of the Skarstrom cycle of fixed bed operations, as shown in the schematic in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Sequential steps in the operation of a fixed bed adsorber in the Skarstrom cycle for C2H2(1)/CO2(2) separation.

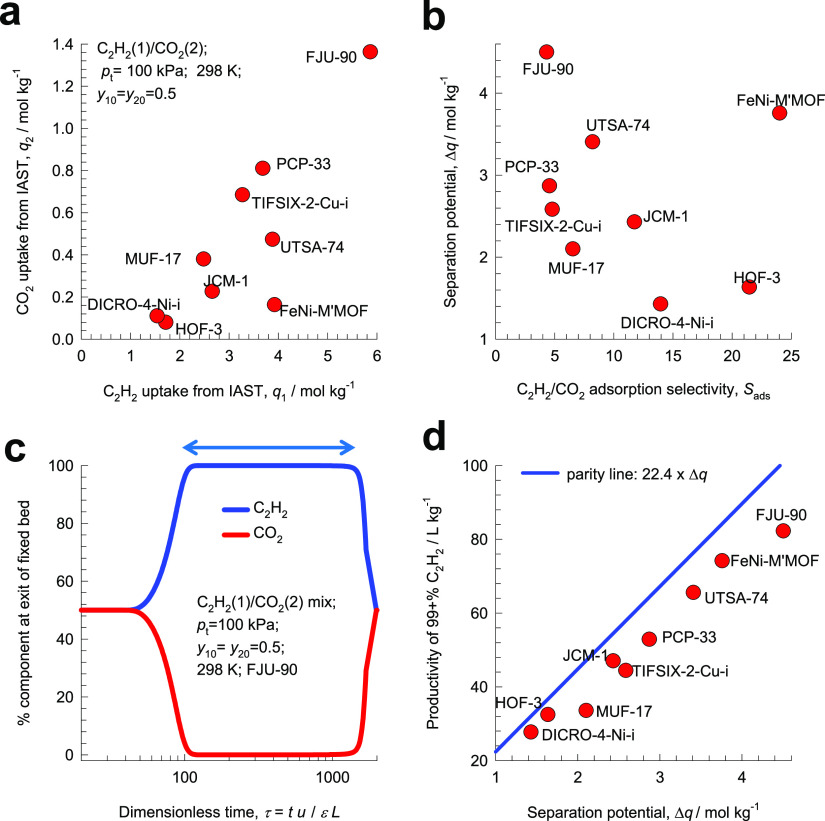

For the nine selected MOFs, Figure 8a,b presents the

IAST calculations of (a) component

loadings q2 versus q1 and (b) separation potential  versus adsorption selectivity Sads.

It is noteworthy that FJU-90 has the highest uptake

capacity for ethyne, whereas the highest selectivity is afforded by

FeNi-M′MOF. The separation performance in fixed bed adsorbers

is dictated by a combination of selectivity and uptake capacities. Figure 8c presents the simulations

of the vacuum blowdown cycle in which the equilibrated fixed bed of

FJU-90 crystallites at the end of the adsorption cycle is subject

to deep vacuum. During the time interval indicated by the arrow, C2H2 of the desired purity can be recovered from

the gas mixture exiting the fixed bed. For a desired purity of 99%+,

the amount of C2H2 that is recoverable can be

determined from a material balance on the adsorber. These productivity

values, expressed as L of the desired product (at

STP) per kilogram of adsorbent in the packed bed, for the nine different

MOFs are plotted in Figure 8d as the y-axis. The x-axis

in Figure 8d is the

separation potential, Δq, calculated using eq 7 with y10 = y20 = 0.5, which represents

the maximum C2H2 productivity that is achievable

if the concentration “fronts” traversed the column in

the form of shock waves during the desorption cycle. We note that

the productivities determined from the transient breakthrough simulations

(denoted as symbols) are near linearly related to Δq. Also shown by the continuous solid line in Figure 8d is the parity line 22.4 × Δq for the productivities. Because of the distended nature

of the transient desorption breakthroughs, the actual productivities

are lower than the parity values. The important conclusion to emerge

is that separation potential, Δq, is the appropriate

metric to use in the screening of MOFs for C2H2/CO2 mixture separations. The MOF with the highest C2H2 productivity is FJU-90, which does not possess

the highest selectivity but the highest Δq.

versus adsorption selectivity Sads.

It is noteworthy that FJU-90 has the highest uptake

capacity for ethyne, whereas the highest selectivity is afforded by

FeNi-M′MOF. The separation performance in fixed bed adsorbers

is dictated by a combination of selectivity and uptake capacities. Figure 8c presents the simulations

of the vacuum blowdown cycle in which the equilibrated fixed bed of

FJU-90 crystallites at the end of the adsorption cycle is subject

to deep vacuum. During the time interval indicated by the arrow, C2H2 of the desired purity can be recovered from

the gas mixture exiting the fixed bed. For a desired purity of 99%+,

the amount of C2H2 that is recoverable can be

determined from a material balance on the adsorber. These productivity

values, expressed as L of the desired product (at

STP) per kilogram of adsorbent in the packed bed, for the nine different

MOFs are plotted in Figure 8d as the y-axis. The x-axis

in Figure 8d is the

separation potential, Δq, calculated using eq 7 with y10 = y20 = 0.5, which represents

the maximum C2H2 productivity that is achievable

if the concentration “fronts” traversed the column in

the form of shock waves during the desorption cycle. We note that

the productivities determined from the transient breakthrough simulations

(denoted as symbols) are near linearly related to Δq. Also shown by the continuous solid line in Figure 8d is the parity line 22.4 × Δq for the productivities. Because of the distended nature

of the transient desorption breakthroughs, the actual productivities

are lower than the parity values. The important conclusion to emerge

is that separation potential, Δq, is the appropriate

metric to use in the screening of MOFs for C2H2/CO2 mixture separations. The MOF with the highest C2H2 productivity is FJU-90, which does not possess

the highest selectivity but the highest Δq.

Figure 8.

IAST calculations

of (a) component loadings q2 vs q1 and (b) separation potential  vs adsorption selectivity Sads for the

adsorption of C2H2(1)/CO2(2) mixtures

in nine different MOFs operating at 298 K and

100 kPa. (c) Simulations of transient desorption (blowdown) under

deep vacuum (0.2 Pa total pressure and 298 K). During the time interval

indicated by the arrow, the C2H2 product containing

<1% CO2 can be recovered. (d) Productivity of 99%+ pure

C2H2 product determined by transient desorption

simulations for PCP-33, HOF-3, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, JCM-1, DICRO-4-Cu-i,

MUF-17, UTSA-74, FJU-90, and FeNi-M′MOF at 298 K and 100 kPa,

plotted as a function of the separation potential

vs adsorption selectivity Sads for the

adsorption of C2H2(1)/CO2(2) mixtures

in nine different MOFs operating at 298 K and

100 kPa. (c) Simulations of transient desorption (blowdown) under

deep vacuum (0.2 Pa total pressure and 298 K). During the time interval

indicated by the arrow, the C2H2 product containing

<1% CO2 can be recovered. (d) Productivity of 99%+ pure

C2H2 product determined by transient desorption

simulations for PCP-33, HOF-3, TIFSIX-2-Cu-i, JCM-1, DICRO-4-Cu-i,

MUF-17, UTSA-74, FJU-90, and FeNi-M′MOF at 298 K and 100 kPa,

plotted as a function of the separation potential  with y10 = y20 = 0.5. Further information on input data

and simulation details are provided in earlier works.41,43,63,121

with y10 = y20 = 0.5. Further information on input data

and simulation details are provided in earlier works.41,43,63,121

2.3. C2H2/C2H4 Mixture Separations

With great potential for separation of C2H2/C2H4 mixtures are a series of three-dimensional (3D) coordination networks composed of inorganic anions of (SiF6)2– (hexafluorosilicate, SIFSIX).30 The pore sizes within this family of SIFSIX materials can be systematically tuned by changing the length of the organic (=pyridine) linkers, the metal (=Cu, Ni, or Zn) node, and/or the framework interpenetration. Figure 9a compares the transient breakthroughs for 1/99 C2H2(1)/C2H4(2) mixtures using SIFSIX-1-Cu, SIFSIX-2-Cu-i, SIFSIX-3-Zn, Mg2(dobdc), and NOTT-300; the ppm C2H2 in the gas mixture at the outlet of the fixed bed is plotted as a function of Q0t/mads, where Q0 is the volumetric flow rate of the gas mixture at the inlet to the fixed bed at STP conditions. From a material balance on the adsorber, we can determine the productivity of purified C2H4, containing less than 40 ppm. The productivity of pure C2H4 is found to be a near-linear function of the separation potential Δq determined from IAST; see Figure 9b. The highest productivity is obtained with SIFSIX-2-Cu-i (2 = 4,4′-dipyridylacetylene and i = interpenetrated);30 in this case, each C2H2 molecule is bound by two F atoms from different nets. The binding of C2H4 with the F atoms is weaker because it is far less acidic than C2H2. This confirms that the separation potential Δq is the appropriate metric for screening MOFs for C2H2/C2H4 mixture separations.

Figure 9.

(a) Transient breakthrough simulations

for 1/99 C2H2/C2H4 mixture

adsorption at 298 K and

100 kPa in a fixed bed packed with five different MOFs. The ppm C2H2 in the gas mixture at the outlet of the fixed

bed is plotted as a function of Q0t/mads, where Q0 is the volumetric flow rate of the gas mixture at the

inlet to the fixed bed, expressed in m3 s–1, at STP conditions. (b) Productivity of pure C2H4, containing less than 40 ppm C2H2,

plotted as a function of the separation potential  determined from IAST with y10 = 0.01; y20 = 0.99. (c)

Separation potential, Δq, of SIFSIX-2-Cu-i

and SIFSIX-1-Cu, plotted as a function of the % C2H2 in the feed mixture. Further information on input data and

simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

determined from IAST with y10 = 0.01; y20 = 0.99. (c)

Separation potential, Δq, of SIFSIX-2-Cu-i

and SIFSIX-1-Cu, plotted as a function of the % C2H2 in the feed mixture. Further information on input data and

simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Figure 9c compares the separation potentials of SIFSIX-2-Cu-i and SIFSIX-1-Cu as a function of the % C2H2 in the feed mixture. While the interpenetrated SIFSIX-2-Cu-i has the superior performance for feed compositions below 5% C2H2, SIFSIX-1-Cu, with a more open structure, has the better separation capability at higher % C2H2 in feed; this trend is verified in the experiments reported by Cui et al.30

2.4. CO2 Capture from Natural Gas

For CO2 capture from natural gas streams, the process economics would demand the high capture capacity, concomitant with high productivity of pure CH4. Li et al.68 report on the experimental results of transient breakthroughs for 40/60 CO2(1)/CH4(2) mixtures in a packed bed with Mg2(dobdc), Co2(dobdc), MIL-100(Cr), and AC at 298 K temperature and 100 kPa total pressure. The masses of the adsorbents in the packed tube are not the same for each MOF, and therefore, their experimental data have been replotted in Figure 10a using Q0t/mads as the x-axis. For each of the five materials, there is a displacement interval (indicated by the arrows) during which purified CH4 can be recovered. The CH4 productivities follow the hierarchy Mg2(dobdc) > Co2(dobdc) > MIL-100(Cr) > AC. Figure 10b presents a plot of productivity of 95%+ pure CH4 as a function of the separation potential Δq = q1y20/y10 – q2. The 95%+ pure CH4 productivities follow the same hierarchy as the Δq values, indicating that the separation potential can be used for screening purposes.

Figure 10.

(a) Experimental breakthroughs for CO2/CH4 mixtures in a packed bed with Mg2(dobdc), Co2(dobdc), MIL-100(Cr), and AC at 298 K. The partial pressures at the inlet are p1 = 40 kPa, p2 = 60 kPa, and pt = 100 kPa. The experimental data, indicated by the symbols, are from Li et al.68 The % CO2 and % CH4 in the exit gas phase are plotted as a function of Q0t/mads. (b) Productivity of 95% pure CH4 plotted as a function of separation potential.

2.5. N2/CH4 Mixture Separations

Although natural gas reserves may contain N2 in concentrations ranging to about 20%,69 the nitrogen content must be reduced to below 4% in order to meet pipeline specifications.70 For large capacity wells, it is most economical to employ cryogenic distillation for nitrogen removal. However, for smaller natural gas reserves, PSA separations become more cost-effective, especially because the feed mixtures are available at high pressures.69,70 The adsorbent materials in the PSA units need to be selective to N2, which is present in smaller concentrations than CH4. For most known adsorbents, the adsorption selectivity for separation of N2/CH4 mixtures is in favor of CH4 because of its higher polarizability.

One practical solution is to rely on diffusion selectivities by using microporous materials, such as LTA-4A zeolite, ETS-4 (ETS = Engelhard Titano-Silicate; ETS-4 is also named as CTS-1 = Contracted Titano Silicate-1), and clinoptilolites, which have significantly higher diffusivities of N2 compared to that of CH4.5,70−73 The “spherical” CH4 (3.7 Å) is much more severely constrained inside the narrow pores of such materials, whereas the “pencil-like” nitrogen molecule (4.4 Å × 3.3 Å) hops lengthwise with higher diffusivity. By tuning the size of the microporous channels of cation-exchanged ETS-4, such as Ba-ETS-4, CH4 can be practically excluded from the pores.

Bhadra70,74 have developed a detailed mathematical model for a PSA scheme for purification of natural gas using Ba-ETS-4, using the steps shown in Figure 11. In this scheme, the inclusion of the cocurrent blowdown step (suggested by Jayaraman et al.72 for N2/CH4 mixture separations with clinoptilolites) increases the CH4 recovery. At the end of the countercurrent blowdown step, the bed contains both nitrogen (fast diffusing) and methane (slow diffusing). Thus, if the bed is simply closed at one end and left for a period of time, the nitrogen will diffuse out first, followed by methane, so the system is, in effect, self-purging (fifth step in the sequence).

Figure 11.

Different steps in the production of purified CH4 using an adsorbent such as LTA-4A zeolite, Ba-ETS-4, and clinoptilolites, which rely on kinetic selectivity. The scheme shows the sequence of processing of a single bed in a multibed PSA scheme. Adapted from Bhadra and Farooq70 and Jayaraman et al.72

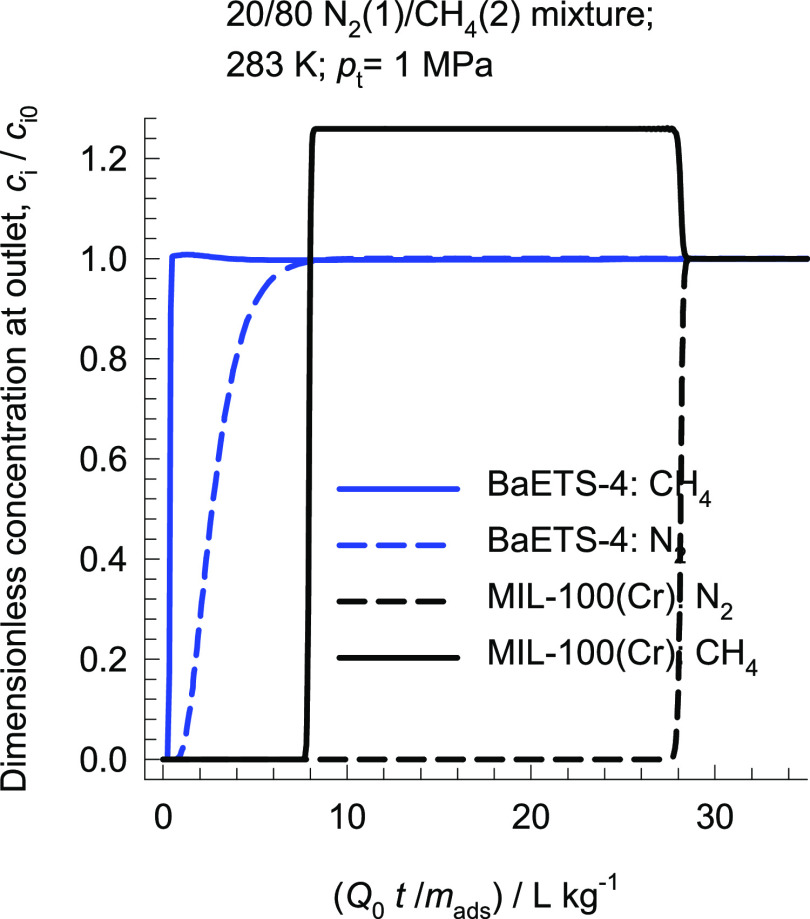

In a recent article, Yoon et al.75 have reported that MIL-100(Cr), activated at 523 K, shows adsorption selectivity in favor of N2. However, an important disadvantage of this material for use in natural gas purification is that CH4 is not completely excluded. Figure 12 compares the transient breakthrough of 20/80 N2(1)/CH4(2) mixtures in a fixed bed adsorber packed with MIL-100(Cr) and Ba-ETS-4, operating at 283 K and total pressure pt = 1 MPa. We note that the breakthrough of CH4 occurs significantly later than that with BaETS-4, implying that a significant amount of CH4 gets adsorbed. Consequently, even after cocurrent blowdown, a significant proportion of CH4 will remain in the void spaces of the fixed bed packed with MIL-100(Cr) and will be “lost” along with N2 in the final blowdown step; this implies that recovery of 96%+ pure CH4 is likely to be unacceptably low with MIL-100(Cr). Candidate adsorbents for N2/CH4 separations must disallow the ingress of CH4 inside the pores.

Figure 12.

Comparison of the transient breakthroughs of 20/80 N2(1)/CH4(2) mixtures in a fixed bed adsorber packed with MIL-100(Cr) and Ba-ETS-4 operating at 283 K and total pressure pt = 1 MPa. Further information on input data and simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

2.6. Separation of C2H4/C2H6 and C3H6/C3H8 Mixtures

Both ethene (C2H4) and propene (C3H6) are important precursors for the manufacture of a variety of polymers. Propene is a byproduct from the steam cracking of liquid feedstocks such as naphtha and liquefied petroleum gas, as well as off-gases produced in fluid catalytic cracking units in refineries. The key processing steps for preparing feedstocks for polymer production are the separations of C2H4/C2H6 and C3H6/C3H8 mixtures, which are traditionally carried out in distillation columns. Because of small differences in the boiling points, the relative volatilities of C2H4/C2H6 and C3H6/C3H8 separations are in the range 1.1–1.2. In order to satisfy the 99.95%+ purity requirement of alkene feedstocks to polymerization reactors, the distillation columns are tall (150–200 trays) and operate at cryogenic temperatures, high pressures, and high reflux ratios (≈15). Use of adsorptive separations may result in reduced energy consumption.

Each of the unsaturated alkenes C2H4 and C3H6 possesses a π-bond, and the preferential adsorption of alkene from the corresponding alkane with the same number of C atoms can be achieved by choosing zeolitic adsorbents with extraframework cations [e.g., LTA-4A zeolite76,77 and NaX (=13X) zeolite76,78] or MOFs with unsaturated “open” metal sites23,79 (e.g., M2(dobdc)23,79 [M = Mg, Mn, Co, Ni, Zn, and Fe; dobdc4– = 2,5-dioxido-1,4-benzenedicarboxylate] and CuBTC80). All of the atoms of C2H4 lie on the same plane, and its dipole moment is zero; however, it does possess a quadrupole moment. It is to be noted that the polarizability of the alkane (C2H6, C3H8) is slightly higher than that of the corresponding alkene (C2H4 and C3H6).

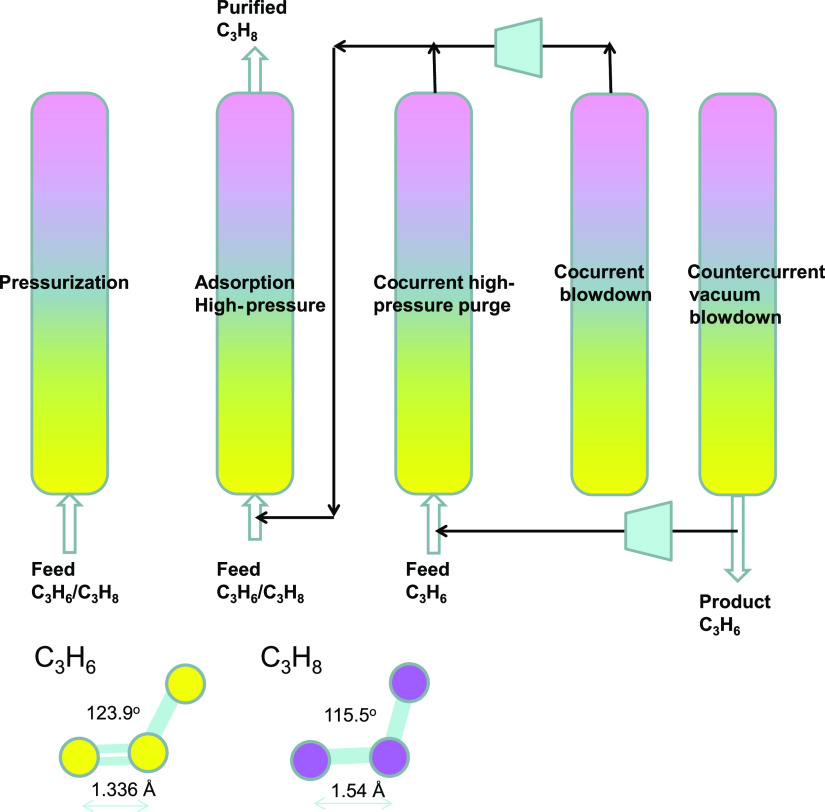

An important disadvantage of the alkene/alkane separations with the adsorbents listed above is that the desired alkene product, required for the production of polymer-grade feedstock, can only be recovered in the desorption phase. In practice, it becomes necessary to operate with multiple beds involving five different steps, as schematized in Figure 13; the C3H6 product of the desired purity is recovered in the final step by countercurrent vacuum blowdown.77,78,81 The recovery of high-purity C3H6 product in the final vacuum blowdown step is expected to be enhanced if C3H8 is (almost) excluded during the high-pressure adsorption cycle. Near-total exclusion of C3H8 is achievable by kinetically based separations using cage-type zeolites with eight-ring windows such as CHA and LTA-4A zeolites.81,82 An alternative is to employ a customized MOF such as NbOFFIVE-1-Ni (=KAUST-7) with pyrazine as the organic linker.24 The use of bulkier (NbOF5)2– pillars causes tilting of the pyrazine molecule on the linker, resulting in an effective aperture of 0.30 nm. This reduced aperture permits ingress of the smaller C3H6 molecules but practically excludes C3H8, relying on subtle differences in bond lengths and bond angles.

Figure 13.

Five-step PSA process for separating C3H6/C3H8 mixtures.77,78,81

Figure 14a,b presents the simulations of the transient breakthroughs for the (a) adsorption and (b) desorption cycles for separation of equimolar C3H6(1)/C3H8(2) mixtures in a fixed bed adsorber packed with KAUST-7 operating at 298 K and 100 kPa. During the time interval indicated by the arrow in Figure 14b, the C3H6 product of desired purity can be recovered. Because of the significantly lower diffusivity of C3H8, the desorption process is self-purging.7,83 In the last step shown in Figure 13, if the bed is simply closed at the one end and left for a period of time, C3H6 will diffuse out first, followed by C3H8. Figure 14c presents a comparison of the transient desorption using three different ratios of intracrystalline diffusivities Đ1/Đ2 = 1, 10, and 100. From a material balance on the adsorber, the productivities of 99%+ pure C3H6 can be determined; the values are, respectively, 15.7, 18.9, and 24.3 L kg–1 at STP for the three scenarios. Because of the sensitivity of the C3H6 productivity to the values of intracrystalline diffusivities, a detailed process design exercise, such as that reported by Khalighi et al.,81,82 will be required in order to compare the C3H6 productivities of KAUST-7, with other MOFs; simple IAST calculations of Δq and Sads are unlikely to be sufficiently accurate for reliable screening.

Figure 14.

Transient breakthrough simulations for (a) adsorption and (b,c) desorption cycles for the separation of C3H6/C3H8 mixtures in a fixed bed adsorber packed with KAUST-7 operating at 298 K and 100 kPa; the feed compositions are y10 = y20 = 0.5. (c) Three different scenarios for the ratios of diffusivities Đ1/Đ2 = 1, 10, and 100 are compared, while maintaining Đ1/rc2 = 1 × 10–3 s–1. Further information on input data and simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

For C2H4/C2H6 separations, near-total exclusion of C2H6 is achieved by use of ultramicroporous MOF [Ca(C4O4)(H2O)] that possesses rigid one-dimensional (1D) channels.25 The 1D channels are of similar size to C2H4 molecules (all atoms of which lie on the same plane), but owing to the size, shape, and rigidity of the pores, they practically exclude C2H6.

For C2H4/C2H6 separations, a number of microporous adsorbents such as Fe2(O2)(dobdc),28 Cu(Qc)2,84 MUF-15,85 PCN-250,86 ZIF-7,87,88 ZIF-8,89,90 IRMOF-8,91 Ni(bdc)(ted)0.5,92 MAF-49,91 CPM-233,26 and CPM-73326 adsorb the saturated alkane selectively exploiting the differences in van der Waals interactions, resulting from the higher polarizability of C2H6. Figure 15a presents the IAST calculations of the C2H6 uptake q2 versus the separation selectivity Sads of 90/10 C2H4/C2H6 mixture adsorption at 298 K and 100 kPa in four different MOFs. The hierarchy of separation selectivities is Cu(Qc)2 > CPM-733 ≈ MUF-15 > CPM-233. However, because of the higher C2H6 uptake capacity of CPM-733, the separation potential, Δq, follows the hierarchy CPM-733 > CPM-233 > MUF-15 > Cu(Qc)2. The separation potential of Cu(Qc)2 is the lowest because it has the smallest C2H6 uptake. In order to verify the hierarchy of Δq determined from IAST, transient breakthrough simulations were carried out for CPM-733, CPM-233, MUF-15, and Cu(Qc)2; see Figure 15b. The dimensionless concentrations at the exit of the packed bed are plotted as a function of Q0t/mads. During the interval indicated by the arrows, purified C2H4 can be recovered. The productivities follow the hierarchy CPM-733 > CPM-233 > MUF-15 > Cu(Qc)2, that is in line with the hierarchy of Δq values. From the transient breakthrough simulations, the amount of 99.95%+ pure C2H4 product recovered during the displacement intervals can be determined. The productivity values show a near-linear dependence on Δq; see Figure 15c. This implies that the IAST calculations of Δq = q1y20/y10 – q2 are appropriate metrics for screening and ranking MOFs.

Figure 15.

(a) IAST calculations of the C2H6 uptake q2 vs the separation selectivity Sads of 90/10 C2H4/C2H6 mixture adsorption at 298 K and 100 kPa in four different MOFs. (b) Transient breakthrough simulations for the separation of 90/10 C2H4/C2H6 mixture adsorption at 298 K and 100 kPa in fixed beds packed with Cu(Qc)2, MUF-15, CPM-233, and CPM-733. (c) Productivity of 99.95%+ pure C2H4 product recovered during the displacement intervals, plotted as function of the separation potential Δq. Further information on input data and simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

2.7. Separation of Hexane Isomers

The values of the research octane number (RON) of alkane isomers increase with the degree of branching. For hexane isomers, for example, the RON values are n-hexane (nC6) = 30; 2-methylpentane (2MP) = 74.5; 3-methylpentane (3MP) = 75.5; 2,2 dimethylbutane (22DMB) = 94; and 2,3 dimethylbutane (23DMB) = 105. Consequently, dibranched alkane isomers are preferred blending components in high-octane gasoline.90,93,94 As shown in the process scheme in Figure 16a, alkane isomers are currently separated on the basis of molecular sieving using LTA-5A zeolite. Linear alkanes can hop from one cage to the adjacent cage through the 4 Å windows of LTA-5A, but monobranched and dibranched alkanes are largely excluded. From an industrial perspective, it is desirable to adopt an alternative separation scheme (see Figure 16b) using an adsorbent that has the capability of separating the dibranched isomers from the linear and monobranched isomers that may be recycled back to the isomerization reactor.

Figure 16.

(a) Currently employed processing scheme for nC6 isomerization and a subsequent separation step using LTA-5A zeolite. (b) Improved processing scheme for the nC6 isomerization process. Further process background details are provided in the Supporting Information.

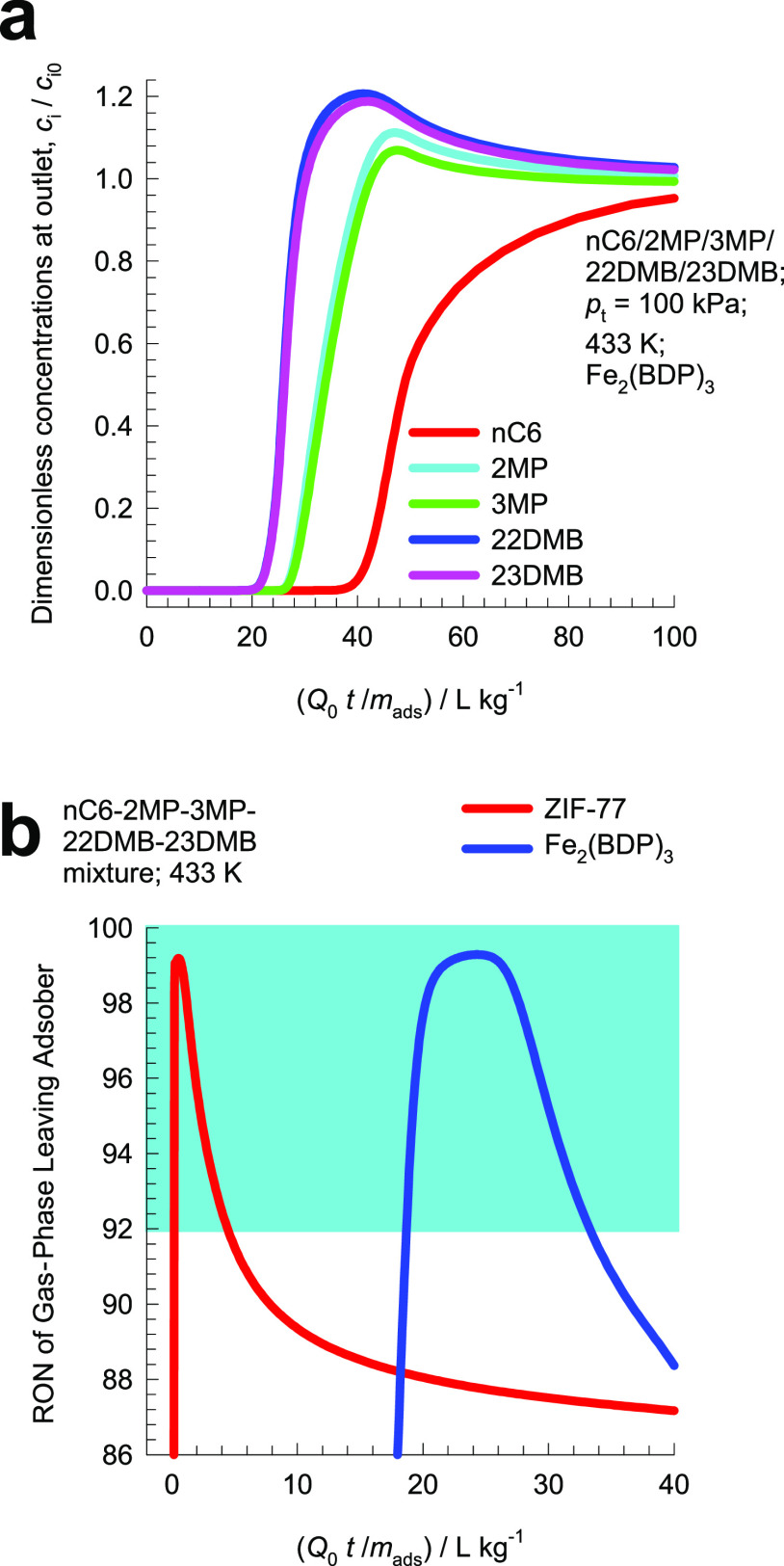

One candidate MOF that can be employed as an adsorbent in Figure 16b is Fe2(BDP)3 [BDP2– = benzenedipyrazolate] that possesses one-dimensional triangular shape channels of 4.9 Å.93 Simulations of transient breakthroughs of hexane isomers using Fe2(BDP)3 are shown in Figure 17a; the hierarchy of breakthroughs is dibranched, monobranched, and linear isomers; this hierarchy is dictated by a combination of adsorption strengths, dictated essentially by van der Waals interactions (nC6 ≫ 2MP ≈ 3MP ≫ 22DMB ≈ 23DMB), and diffusivities (nC6 > 2MP ≈ 3MP > 22DMB ≈ 23DMB). The RON of the product gas mixture exiting the adsorber is plotted in Figure 17b. During a certain time interval, the 92+ RON product can be recovered for incorporation into the gasoline pool. This requirement of 92+ RON implies that the product stream will contain predominantly the dibranched isomers 22DMB and 23DMB, while allowing a small proportion of 2MP and 3MP to be incorporated into the product stream. Also shown in Figure 17b, for comparison purposes, is the corresponding breakthrough simulation data for ZIF-7794 that has a characteristic pore dimension of 4.5 Å. Because of stronger diffusional limitations in ZIF-77, the 92+ RON productivity of ZIF-77 is significantly lower than that of Fe2(BDP)3; this is evidenced by the significantly shorter time interval during which 92+ RON product can be recovered.

Figure 17.

(a) Simulations of transient breakthrough characteristics for a five-component nC6/2MP/3MP/22DMB/23DMB mixture in a fixed bed adsorber packed with Fe2(BDP)3 operating at a total pressure of 100 kPa and 433 K. The partial pressures of the components in the bulk gas phase at the inlet are p1 = p2 = p3 = p4 = p5 = 20 kPa. (b) Plot of RON of product gas mixture exiting the fixed bed adsorber packed with ZIF-77 and Fe2(BDP)3, plotted as a function of Q0t/mads. Further information on input data and simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

2.8. Separation of C8 Aromatics

The xylene isomers, o-xylene, m-xylene, and in particular p-xylene, are important chemical intermediates. Xylenes, along with other aromatic hydrocarbons, are commonly obtained from catalytic reforming of naphtha, as illustrated in the process scheme in Figure 18.63,95,96 The products of catalytic reformer are fed to a distillation column called the reformate splitter. The bottom product of the reformate splitter, rich in xylenes, is further distilled in the xylene splitter, whose bottom product consists of C9+ aromatics. The recovery of p-xylene from the mixture of C8 aromatics (typically composition: 20% o-xylene, 44% m-xylene, 17% p-xylene, and 19% ethylbenzene) in the overhead product of the xylene splitter is the focus of attention in this section.

Figure 18.

Schematic showing the separations of the products from a catalytic reforming unit. Further process background details are provided in the Supporting Information.

Because of the very small differences in boiling points (cf. Figure 19), p-xylene recovery by use of distillation technology is not feasible. Two different technologies are currently in use for recovery of p-xylene: (a) fractional crystallization and (b) selective adsorption. Fractional crystallization relies on the differences in freezing points (cf. Figure 19). The freezing point of p-xylene is significantly higher than that of other C8 aromatics; on cooling, therefore, pure p-xylene crystals are the first to emerge from the solution. Selective adsorption of p-xylene from liquid-phase mixtures of C8 aromatics is achieved with cation-exchange FAU zeolite adsorbent, such as BaX, in a simulated moving bed (SMB) adsorption device.97−99 The hierarchy of adsorption strengths in BaX is dictated by molecular packing, or entropy, effects that prevail under pore saturation conditions in liquid-phase SMB separations.95,97−100 Unlike PSA technologies for gaseous separations, the SMB process operates continuously under steady-state conditions; see the schematic in Figure 20.

Figure 19.

Boiling points and freezing points of C8 hydrocarbons, along with molecular dimensions, culled from Torres-Knoop et al.107

Figure 20.

SMB adsorption technology for the separation of a feed mixture containing o-xylene/m-xylene/p-xylene/ethylbenzene. The SMB technology is depicted here with countercurrent contacting between the down-flowing adsorbent material and up-flowing desorbent (eluent) liquid. Also indicated are the liquid-phase concentrations of a mixture of o-xylene/m-xylene/p-xylene/ethylbenzene using the information presented by Minceva and Rodrigues.101

The C8 aromatic feed is introduced at a port near the middle of the SMB unit.101,102 The desorbent p-diethylbenzene (boiling point 450 K) is introduced at the bottom.103Figure 20 also indicates typical liquid phase concentrations of o-xylene, m-xylene, p-xylene, and ethylbenzene along the adsorber height. The extract phase, containing the more strongly adsorbed p-xylene, is recovered below the feed injection port in the bottom section of the column. The raffinate phase, containing the more weakly adsorbed o-xylene, m-xylene, and ethylbenzene, is tapped off above the feed injection port in the upper section of the column.

For realizing improvements in the SMB units, there is considerable scope for the development of MOFs that have both higher uptake capacity and selectivity to p-xylene as compared to BaX zeolite. Improved MOF adsorbents will result in lower recirculation flows of eluent, and microporous adsorbent in the SMB unit, and this will result in significant economic advantages. There are several MOFs such as DynaMOF-100,104,105 Co-CUK-1,106 MAF-X8,107 JUC-77,108 Co(BDP),21 and MIL-125109−111 that have the potential for use in SMB units.

For preferential adsorption of p-xylene, and rejection of o-xylene, m-xylene, and ethylbenzene, the appropriate metric for comparing these MOFs is the separation potential Δq that is derived using the shock wave model for fixed bed adsorbers63

| 8 |

In eq 8, the molar loadings of each of the four C8 aromatics, qi, expressed in mol per kilogram of crystalline adsorbent are calculated using the IAST for mixture adsorption equilibrium. Figure 21 presents the plot of Δq versus p-xylene uptake for a few selected MOFs. The highest value of the separation potential is offered by DynaMOF-100 that is a Zn(II)-based dynamic coordination framework that undergoes guest-induced structural changes so as to allow selective uptake of p-xylene within the cavities. A slightly lower separation potential is offered by Co-CUK-1 that is composed of cobalt(II) cations and the dianion of dicarboxylic acid; the 1D zigzag-shaped channels of Co-CUK-1 allow optimal vertical stacking of p-xylene. Both these MOFs offer separation potentials about three to four times that achievable by BaX; there is a need for experimental verification of this expectation.

Figure 21.

Plot of the separation potential, Δq, vs the gravimetric uptake of p-xylene. Further information on input data and simulation details are provided in the Supporting Information.

2.9. Influence of Thermodynamic Nonidealities in Mixture Adsorption

In many cases, the IAST fails to provide a quantitatively correct description of mixture adsorption equilibrium and thus thermodynamic nonidealities come into play. Thermodynamic nonidealities are evidenced for water/alcohol mixtures because of molecular clustering engendered by hydrogen bonding.112−117 Thermodynamic nonidealities also arise because of preferential location of CO2 molecules at the window regions of eight-ring zeolites such as DDR, CHA, ERI, LTA-4A, and LTA-5A.55,56,117−119 For CO2 capture with NaX zeolite, there is congregation of CO2 around the cations, resulting in failure of IAST.117,119 Thermodynamic nonidealities can be strong enough to cause selectivity reversals for CO2/hydrocarbon mixture adsorption in cation-exchanged zeolites.55,56,117 Framework flexibility and gate-opening behaviors may lead to failure of IAST.120 In all the aforementioned cases, we need to use the real adsorbed solution theory (RAST) for quantitative description of mixture adsorption in transient breakthrough simulations. RAST calculations of Δq may be used for screening purposes.116,119

3. Conclusions

The following major conclusions emerge from this study.

-

(1)

The separation performance in fixed bed devices is governed by a combination of adsorption selectivity, Sads, and uptake capacities, q1, q2; low uptake capacities diminish the separation performance of MOFs with high values of Sads.

-

(2)

The separation potential Δq, which is calculable on the basis of IAST, provides a simple and convenient metric to screen and rank the separation capability of MOFs. For a component that is recovered in pure form during the adsorption cycle, Δq can be calculated using eq 2, which is derived using the shock wave model. For a component that is recovered in pure form during the blowdown cycle, the separation potential Δq is defined by eq 7. The value of Δq defines the upper limit to the achievable separations in fixed bed units. The actual separations in fixed bed adsorbers will be lower than the IAST-calculated Δq values because of distended breakthroughs.

-

(3)

The composition of the feed mixture may have a significant influence on the separation potential of the MOF; this is illustrated in Figure 9c for C2H2/C2H4 mixtures.

-

(4)

Broadly speaking, high product purities are more difficult to achieve if the desired product is recovered in the blowdown cycle of PSA schemes, as presented in Figures 7, 11, and 13. In such cases, it is advantageous to have MOF adsorbents that virtually exclude the less strongly adsorbing component because this facilitates the achievement of high-purity products. The productivity calculations are very sensitive to intracrystalline diffusion limitations, as illustrated in Figure 14 for C3H6/C3H8 mixture separations using KAUST-7.

-

(5)

The concept of separation potential is particularly advantageous for multicomponent separations; several selectivities and uptake capacities are incorporated into one combined metric that quantifies the desired separation task. For example, eq 8 is the appropriate expression for Δq for separation of four-component mixture of C8 aromatics

-

(6)

As illustrated in Figures 5, 9, 10, 12, 15, and 17, transient breakthrough experiments or simulations can be directly used to compare the separation effectiveness of MOFs. In such cases, the appropriate x-axis for plotting purposes is Q0t/mads; this parameter may be viewed as “corrected” time. Such comparisons are indispensable for comparison and screening of MOFs that are subject to severe diffusion limitations,90,121

-

(7)

For situations in which the intracrystalline influences are strong, the separation performance will be significantly lowered and IAST calculations of Δq will not be adequate for screening purposes.

-

(8)

For kinetically driven separation, as used industrially for N2/CH4 and N2/O2 mixtures, some authors have suggested the use of

as a metric to quantify kinetic

influences.71,81 The concept of the separation

potential Δq is not of relevance in such cases.

as a metric to quantify kinetic

influences.71,81 The concept of the separation

potential Δq is not of relevance in such cases.

Acknowledgments

The simulation code for transient breakthroughs was developed by Dr. Richard Baur and Dr. Jasper van Baten; their assistance and help are gratefully acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c02218.

Methodology used for transient breakthrough simulations, analytic solutions to the shock wave model for fixed bed transient operations, structural information on the MOFs investigated, unary isotherm data sources for each guest/host combination, and data inputs of simulation results for each of the investigated mixture separations (PDF)

The author declares no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Sircar S.; Golden T. C. Purification of Hydrogen by Pressure Swing Adsorption. Separ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 35, 667–687. 10.1081/ss-100100183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro A. M.; Grande C. A.; Lopes F. V. S.; Loureiro J. M.; Rodrigues A. E. A parametric study of layered bed PSA for hydrogen purification. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2008, 63, 5258–5273. 10.1016/j.ces.2008.07.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banu A.-M.; Friedrich D.; Brandani S.; Düren T. A Multiscale Study of MOFs as Adsorbents in H2 PSA Purification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 9946–9957. 10.1021/ie4011035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majlan E. H.; Wan Daud W. R.; Iyuke S. E.; Mohamad A. B.; Kadhum A. A. H.; Mohammad A. W.; Takriff M. S.; Bahaman N. Hydrogen purification using compact pressure swing adsorption system for fuel cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 2771–2777. 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.12.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. T.Adsorbents: Fundamentals and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, New Jersey, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ruthven D. M.Principles of Adsorption and Adsorption Processes; John Wiley: New York, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ruthven D. M.; Farooq S.; Knaebel K. S.. Pressure Swing Adsorption; VCH Publishers: New York, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn S.; You Y.-W.; Lee D.-G.; Kim K.-H.; Oh M.; Lee C.-H. Layered Two- and Four-bed PSA Processes for H2 Recovery from Coal Gas. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 68, 413–423. 10.1016/j.ces.2011.09.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pakseresht S.; Kazemeini M.; Akbarnejad M. M. Equilibrium isotherms for CO, CO2, CH4 and C2H4 on the 5A molecular sieve by a simple volumetric apparatus. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2002, 28, 53–60. 10.1016/s1383-5866(02)00012-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sircar S. Basic research needs for design of adsorptive gas separation processes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 5435–5448. 10.1021/ie051056a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang R. T.Gas Separation by Adsorption Processes; Butterworth: Boston, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Belmabkhout Y.; Pirngruber G.; Jolimaitre E.; Methivier A. A complete experimental approach for synthesis gas separation studies using static gravimetric and column breakthrough experiments. Adsorption 2007, 13, 341–349. 10.1007/s10450-007-9032-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Yao K.; Zhu Y.; Li B.; Shi Z.; Krishna R.; Li J. Cu-TDPAT, an rht-type Dual-Functional Metal–Organic Framework Offering Significant Potential for Use in H2 and Natural Gas Purification Processes Operating at High Pressures. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 16609–16618. 10.1021/jp3046356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herm Z. R.; Krishna R.; Long J. R. CO2/CH4, CH4/H2 and CO2/CH4/H2 separations at high pressures using Mg2(dobdc). Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 151, 481–487. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.09.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herm Z. R.; Swisher J. A.; Smit B.; Krishna R.; Long J. R. Metal-Organic Frameworks as Adsorbents for Hydrogen Purification and Pre-Combustion Carbon Dioxide Capture. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5664–5667. 10.1021/ja111411q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason J. A.; Sumida K.; Herm Z. R.; Krishna R.; Long J. R. Evaluating Metal-Organic Frameworks for Post-Combustion Carbon Dioxide Capture via Temperature Swing Adsorption. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3030–3040. 10.1039/c1ee01720a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang S.; He Y.; Zhang Z.; Wu H.; Zhou W.; Krishna R.; Chen B. Microporous Metal-Organic Framework with Potential for Carbon Dioxide Capture at Ambient Conditions. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 954. 10.1038/ncomms1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgari M.; Semino R.; Schouwink P. A.; Kochetygov I.; Tarver J.; Trukhina O.; Krishna R.; Brown C. M.; Ceriotti M.; Queen W. L. Understanding how Ligand Functionalization influences CO2 and N2 Adsorption in a Sodalite MOF. Chem. Mater. 2020, 32, 1526–1536. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b04631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. A comparison of the CO2 capture characteristics of zeolites and metal-organic frameworks. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 87, 120–126. 10.1016/j.seppur.2011.11.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Adsorptive separation of CO2/CH4/CO gas mixtures at high pressures. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 156, 217–223. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.02.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. In silico screening of metal-organic frameworks in separation applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 10593–10616. 10.1039/c1cp20282k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan A. K.; Avila A. M.; Rajendran A. Do adsorbent screening metrics predict process performance? Aprocess optimisation based study for post-combustion capture of CO2. Int. J. Greenhouse Gas Control 2016, 46, 76–85. 10.1016/j.ijggc.2015.12.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch E. D.; Queen W. L.; Krishna R.; Zadrozny J. M.; Brown C. M.; Long J. R. Hydrocarbon Separations in a Metal-Organic Framework with Open Iron(II) Coordination Sites. Science 2012, 335, 1606–1610. 10.1126/science.1217544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadiau A.; Adil K.; Bhatt P. M.; Belmabkhout Y.; Eddaoudi M. A Metal-Organic Framework–Based Splitter for Separating Propylene from Propane. Science 2016, 353, 137–140. 10.1126/science.aaf6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R.-B.; Li L.; Zhou H.-L.; Wu H.; He C.; Li S.; Krishna R.; Li J.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Molecular Sieving of Ethylene from Ethane using a Rigid Metal-Organic Framework. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 1128–1133. 10.1038/s41563-018-0206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H.; Wang Y.; Krishna R.; Jia X.; Wang Y.; Hong A. N.; Dang C.; Castillo H. E.; Bu X.; Feng P. Pore-Space-Partition-Enabled Exceptional Ethane Uptake and Ethane-Selective Ethane–Ethylene Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2222–2227. 10.1021/jacs.9b12924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Z.; Wang J.; Zhang Z.; Xing H.; Yang Q.; Yang Y.; Wu H.; Krishna R.; Zhou W.; Chen B.; Ren Q. Molecular Sieving of Ethane from Ethylene through the molecular Cross-section Size Differentiation in Gallate-based Metal-Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 16020–16025. 10.1002/anie.201808716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Lin R.-B.; Krishna R.; Li H.; Xiang S.; Wu H.; Li J.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Ethane/ethylene Separation in a Metal-Organic Framework with Iron-Peroxo Sites. Science 2018, 362, 443–446. 10.1126/science.aat0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.; Li L.; Wang J.-X.; Wen H.-M.; Krishna R.; Wu H.; Zhou W.; Chen Z.-N.; Li B.; Qian G.; Chen B. Selective Ethane/Ethylene Separation in a Robust Microporous Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 633–640. 10.1021/jacs.9b12428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X.; Chen K.; Xing H.; Yang Q.; Krishna R.; Bao Z.; Wu H.; Zhou W.; Dong X.; Han Y.; Li B.; Ren Q.; Zaworotko M. J.; Chen B. Pore Chemistry and Size Control in Hybrid Porous Materials for Acetylene Capture from Ethylene. Science 2016, 353, 141–144. 10.1126/science.aaf2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y. L.; He C.; Pham T.; Wang T.; Li P.; Krishna R.; Forrest K. A.; Hogan A.; Suepaul S.; Space B.; Fang M.; Chen Y.; Zaworotko M. J.; Li J.; Li L.; Zhang Z.; Cheng P.; Chen B. Robust Microporous Metal-Organic Frameworks for Highly Efficient and Simultaneous Removal of Propyne and Propadiene from Propylene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 10209–10214. 10.1002/anie.201904312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y.; Krishna R.; Yang L. X.; Fan Y. L.; Wang L.; Gao Z.; Xiong J. B.; Sun L. J.; Luo F. Enhancing C2H2/C2H4 separation by incorporating low-content sodium in covalent organic framework. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2921–2926. 10.1039/c9qi00922a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Wen H. M.; He C.; Lin R. B.; Krishna R.; Wu H.; Zhou W.; Li J.; Li B.; Chen B. A Metal–Organic Framework with Suitable Pore Size and Specific Functional Site for Removal of Trace Propyne from Propylene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15183–15188. 10.1002/anie.201809869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Lin R.-B.; Krishna R.; Wang X.; Li B.; Wu H.; Li J.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Efficient Separation of Ethylene from Acetylene/Ethylene Mixtures by a Flexible-Robust Metal–Organic Framework. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 18984–18988. 10.1039/c7ta05598f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Lin R.-B.; Krishna R.; Wang X.; Li B.; Wu H.; Li J.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Flexible–Robust Metal–Organic Framework for Efficient Removal of Propyne from Propylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 7733–7736. 10.1021/jacs.7b04268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Krishna R.; Wang Y.; Wang X.; Yang J.; Li J. Flexible metal–organic frameworks with discriminatory gate-opening effect for separation of acetylene from ethylene/acetylene mixtures. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 4457–4462. 10.1002/ejic.201600182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen H.-M.; Li B.; Wang H.; Wu C.; Alfooty K.; Krishna R.; Chen B. A Microporous Metal–Organic Framework with Rare lvt Topology for Highly Selective C2H2/C2H4 Separation at Room Temperature. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 5610–5613. 10.1039/c4cc09999k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda R.; Kitaura R.; Kitagawa S.; Kubota Y.; Belosludov R. V.; Kobayashi T. C.; Sakamoto H.; Chiba T.; Takata M.; Kawazoe Y.; Mita Y. Highly controlled acetylene accommodation in a metal–organic microporous material. Nature 2005, 436, 238–241. 10.1038/nature03852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M.; Hoffmann F.; Fröba M. New Microporous Materials for Acetylene Storage and C2H2/CO2 Separation: Insights from Molecular Simulations. ChemPhysChem 2010, 11, 2220–2229. 10.1002/cphc.201000126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L.; Yang L.; Gong L.; Krishna R.; Gao Z.; Tao Y.; Yin W.; Xu Z.; Luo F. Constructing redox-active microporous hydrogen-bonded organic framework by imide-functionalization: photochromism, electrochromism, and selective adsorption of C2H2 over CO2. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123117. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.123117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J.; Qian X.; Lin R. B.; Krishna R.; Wu H.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Mixed Metal-Organic Framework with Multiple Binding Sites for Efficient C2H2/CO2 Separation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4396–4400. 10.1002/anie.202000323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R.; Liu Q.-Y.; Krishna R.; Wang W.; He C.-T.; Wang Y.-L. Water-stable Europium-1,3,6,8-tetrakis(4-carboxylphenyl)pyrene Framework for Efficient C2H2/CO2 Separation. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5089–5095. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y.; Ma Z.; Lin R.-B.; Krishna R.; Zhou W.; Lin Q.; Zhang Z.; Xiang S.; Chen B. Pore Space Partition within a Metal-Organic Framework for Highly Efficient C2H2/CO2 Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 4130–4136. 10.1021/jacs.9b00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H. Q.; Yan C. S.; Luo F.; Krishna R. Beyond Crystal Engineering: Significant Enhancement of C2H2/CO2 Separation by Constructing Composite Material. Inorg. Chem. 2018, 57, 3679–3682. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo M. L.; Matsuda R.; Hijikata Y.; Krishna R.; Sato H.; Horike S.; Hori A.; Duan J.; Sato Y.; Kubota Y.; Takata M.; Kitagawa S. An Adsorbate Discriminatory Gate Effect in a Flexible Porous Coordination Polymer for Selective Adsorption of CO2 over C2H2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 3022–3030. 10.1021/jacs.5b10491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F.; Yan C.; Dang L.; Krishna R.; Zhou W.; Wu H.; Dong X.; Han Y.; Hu T.-L.; O’Keeffe M.; Wang L.; Luo M.; Lin R.-B.; Chen B. UTSA-74: A MOF-74 Isomer with Two Accessible Binding Sites per Metal Center for Highly Selective Gas Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5678–5684. 10.1021/jacs.6b02030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan J.; Jin W.; Krishna R. Natural Gas Purification Using a Porous Coordination Polymer with Water and Chemical Stability. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 4279–4284. 10.1021/ic5030058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P.; He Y.; Zhao Y.; Weng L.; Wang H.; Krishna R.; Wu H.; Zhou W.; O’Keeffe M.; Han Y.; Chen B. A Rod-Packing Microporous Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Framework for Highly Selective Separation of C2H2/CO2 at Room Temperature. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 574–577. 10.1002/anie.201410077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K.-J.; Scott H. S.; Madden D. G.; Pham T.; Kumar A.; Bajpai A.; Lusi M.; Forrest K. A.; Space B.; Perry J. J.; Zaworotko M. J. Benchmark C2H2/CO2 and CO2/C2H2 Separation by Two Closely Related Hybrid Ultramicroporous Materials. Chem 2016, 1, 753–765. 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.10.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.; Chuah C. Y.; Kim J.; Kim Y.; Ko N.; Seo Y.; Kim K.; Bae T. H.; Lee E. Separation of Acetylene from Carbon Dioxide and Ethylene by a Water-Stable Microporous Metal–Organic Framework with Aligned Imidazolium Groups inside the Channels. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2018, 130, 7995–7999. 10.1002/ange.201804442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott H. S.; Shivanna M.; Bajpai A.; Madden D. G.; Chen K.-J.; Pham T.; Forrest K. A.; Hogan A.; Space B.; Perry J. J. IV; Zaworotko M. J. Highly Selective Separation of C2H2 from CO2 by a New Dichromate-Based Hybrid Ultramicroporous Material. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 33395–33400. 10.1021/acsami.6b15250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qazvini O. T.; Babarao R.; Telfer S. G. Multipurpose Metal–Organic Framework for the Adsorption of Acetylene: Ethylene Purification and Carbon Dioxide Removal. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31, 4919–4926. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b01691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J.; Shao K.; Wang J. X.; Wen H. M.; Yang Y.; Cui Y.; Krishna R.; Li B.; Qian G. A Chemically Stable Hofmann-Type Metal–Organic Framework with Sandwich-Like Binding Sites for Benchmark Acetylene Capture. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1908275. 10.1002/adma.201908275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman J. E.; Reed D. A.; Kapelewski M. T.; Chachra G.; Jonnavittula D.; Radaelli G.; Long J. R. Enabling alternative ethylene production through its selective adsorption in the metal–organic framework Mn2(m-dobdc). Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2423–2431. 10.1039/c8ee01332b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Zandvoort I.; Ras E.-J.; Graaf R. d.; Krishna R. Using Transient Breakthrough Experiments for Screening of Adsorbents for Separation of C2H4/CO2 Mixtures. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 241, 116706. 10.1016/j.seppur.2020.116706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Zandvoort I.; van der Waal J. K.; Ras E.-J.; de Graaf R.; Krishna R. Highlighting non-idealities in C2H4/CO2 mixture adsorption in 5A zeolite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 227, 115730. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.115730. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee D.; Cairns A. J.; Liu J.; Motkuri R. K.; Nune S. K.; Fernandez C. A.; Krishna R.; Strachan D. M.; Thallapally P. K. Potential of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Capture of Noble Gases. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 211–219. 10.1021/ar5003126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Diffusing Uphill with James Clerk Maxwell and Josef Stefan. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2019, 195, 851–880. 10.1016/j.ces.2018.10.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.; Plonka A. M.; Banerjee D.; Krishna R.; Schaef H. T.; Ghose S.; Thallapally P. K.; Parise J. B. Direct Observation of Xe and Kr Adsorption in a Xe-selective Microporous Metal Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7007–7010. 10.1021/jacs.5b02556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X.; Zong Z.; Elsaidi S. K.; Jasinski J. B.; Krishna R.; Thallapally P. K.; Carreon M. A. Kr/Xe Separation over a Chabazite Zeolite Membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 9791–9794. 10.1021/jacs.6b06515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Yao K.; Zhang Z.; Jagiello J.; Gong Q.; Han Y.; Li J. The First Example of Commensurate Adsorption of Atomic Gas in a MOF and Effective Separation of Xenon from Other Noble Gases. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 620–624. 10.1039/c3sc52348a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge G.; Franke T.; Schöllner R.; Nagel G. Estimation of Component Loadings in Fixed-Bed Adsorption from Breakthrough Curves of Binary Gas Mixtures in Nontrace Systems. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1991, 46, 368–371. 10.1016/0009-2509(91)80146-p. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Screening Metal-Organic Frameworks for Mixture Separations in Fixed-Bed Adsorbers using a Combined Selectivity/Capacity Metric. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 35724–35737. 10.1039/c7ra07363a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. L.; Prausnitz J. M. Thermodynamics of Mixed Gas Adsorption. AIChE J. 1965, 11, 121–127. 10.1002/aic.690110125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Thallapally P. K.; Strachan D. Metal–Organic Frameworks for Removal of Xe and Kr from Nuclear Fuel Reprocessing Plants. Langmuir 2012, 28, 11584–11589. 10.1021/la301870n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Strachan D. M.; Thallapally P. K. Enhanced noble gas adsorption in Ag@MOF-74Ni. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 466–468. 10.1039/c3cc47777k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdal Y.; Keskin S. Atomically Detailed Modeling of Metal Organic Frameworks for Adsorption, Diffusion, and Separation of Noble Gas Mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 7373–7382. 10.1021/ie300766s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Yang J.; Li J.; Chen Y.; Li J. Separation of CO2/CH4 and CH4/N2 Mixtures by M/DOBDC: a Detailed Dynamic Comparison with MIL-100(Cr) and Activated Carbon. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 198, 236–246. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.07.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliabue M.; Farrusseng D.; Valencia S.; Aguado S.; Ravon U.; Rizzo C.; Corma A.; Mirodatos C. Natural gas treating by selective adsorption: Material science and chemical engineering interplay. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 155, 553–566. 10.1016/j.cej.2009.09.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra S. J.; Farooq S. Separation of MethaneNitrogen Mixture by Pressure Swing Adsorption for Natural Gas Upgrading. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 14030–14045. 10.1021/ie201237x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar B.; Bhadra S. J.; Marathe R. P.; Farooq S. Adsorption and Diffusion of Methane and Nitrogen in Barium Exchanged ETS-4. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 3021–3034. 10.1021/ie1014124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman A.; Hernandez-Maldonado A. J.; Yang R. T.; Chinn D.; Munson C. L.; Mohr D. H. Clinoptilolites for Nitrogen/Methane Separation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2004, 59, 2407–2417. 10.1016/j.ces.2003.10.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Habgood H. W. The Kinetics of Molecular Sieve Action. Sorption of Nitrogen-Methane Mixtures by Linde Molecular Sieve 4A. Can. J. Chem. 1958, 36, 1384–1397. 10.1139/v58-204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra S. J.Methane-Nitrogen Separation by Pressure Swing Adsorption. Ph.D. Dissertation, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J. W.; Chang H.; Lee S.-J.; Hwang Y. K.; Hong D.-Y.; Lee S.-K.; Lee J. S.; Jang S.; Yoon T.-U.; Kwac K.; Jung Y.; Pillai R. S.; Faucher F.; Vimont A.; Daturi M.; Férey G.; Serre C.; Maurin G.; Bae Y.-S.; Chang J.-S. Selective Nitrogen Capture by Porous Hybrid Materials Containing Accessible Transition Metal Ion Sites. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 526–531. 10.1038/nmat4825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva F. A.; Rodrigues A. E. Vacuum swing adsorption for propylene/propane separation with 4A zeolite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 5758–5774. 10.1021/ie0008732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grande C. A.; Poplow F.; Rodrigues A. E. Vacuum pressure swing adsorption to produce polymer-grade polypropylene. Separ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 1252–1259. 10.1080/01496391003652767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva F. A. D.; Rodrigues A. E. PropylenePropane Separation by Vacuum Swing Adsorption Using 13X Zeolite. AIChE J. 2001, 47, 341–357. 10.1002/aic.690470212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geier S. J.; Mason J. A.; Bloch E. D.; Queen W. L.; Hudson M. R.; Brown C. M.; Long J. R. Selective adsorption of ethylene over ethane and propylene over propane in the metal–organic frameworks M2(dobdc) (M = Mg, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn). Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 2054–2061. 10.1039/c3sc00032j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon J.-W.; Jang I.-T.; Lee K.-Y.; Hwang Y.-K.; Chang J.-S. Adsorptive Separation of Propylene and Propane on a Porous Metal-Organic Framework, Copper Trimesate. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2010, 31, 220–223. 10.5012/bkcs.2010.31.01.220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalighi M.; Karimi I. A.; Farooq S. Comparing SiCHA and 4A Zeolite for Propylene/Propane Separation using a Surrogate-Based Simulation/Optimization Approach. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 16973–16983. 10.1021/ie404392j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalighi M.; Chen Y. F.; Farooq S.; Karimi I. A.; Jiang J. W. Propylene/Propane Separation Using SiCHA. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 3877–3892. 10.1021/ie3026955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthven D. M.; Farooq S. Air Separation by Pressure Swing Adsorption. Gas Sep. Purif. 1990, 4, 141–148. 10.1016/0950-4214(90)80016-e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R.-B.; Wu H.; Li L.; Tang X.-L.; Li Z.; Gao J.; Cui H.; Zhou W.; Chen B. Boosting Ethane/Ethylene Separation within Isoreticular Ultramicroporous Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 12940–12946. 10.1021/jacs.8b07563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]