Abstract

Background:

Several measures are available to assess childhood physical and sexual abuse, but few measures focus specifically on neglect and little psychometric research on measures exists. This paper aims to fill a gap in the field by describing a new instrument to measure childhood neglect retrospectively and providing information about construct, predictive, and discriminant validity using adults with documented histories of childhood neglect.

Methods:

Data are from a large prospective, longitudinal study of abused and neglected children and matched controls followed up and assessed in adulthood. The current sample (N =717) includes 370 individuals with histories of childhood neglect and 347 demographically matched controls without those histories. Self-reports of childhood neglect were collected in in-person interviews at approximate age 40. Participants responded to a pool of items representing neglect. Missing responses were treated as substantive information in analyses. An optimal set of items was selected using Support Vector Machine (SVM) – a machine leaning algorithm. Neglect severity, diversity and SVM-based propensity scores were tested for predictive, construct and discriminant validity.

Results:

The optimal item subset included 10 items. The propensity scale measured with this optimal subset passed all validity tests, showing high predictive validity for neglect, discrimination between documented cases of neglect and abuse, and significant correlation with violence in adulthood (construct validity). The simple severity and diversity scores failed in at least one of the validity tests.

Conclusions:

This new instrument shows promise in detecting experiences of childhood neglect retrospectively. Missing responses were found informative in recollections of childhood neglect.

Introduction

Neglect is the most common type of child maltreatment in the United States, accounting for the vast majority (more than 75%) of the 3.5 million children in 2017 who received a child protective service investigation (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019). In general, neglect is defined as the failure to provide a child with the basic needs of food, clothing, shelter, education, and medical attention. Definitions typically place responsibility for safeguarding children from neglect on all caregivers, including parents, relatives, teachers, babysitters, clergy, and coaches. However, there is considerable debate about appropriate definitions, given the heterogeneity of children’s needs (e.g., physical, emotional, safety, medical, educational, and environmental), the purpose of specific definitions and criteria (legal versus clinical versus research), and the recognition that definitions vary by state. Indeed, Dubowitz (2006) has suggested that there may never be a single definition of neglect, given the multiplicity of purposes it serves.

Barnett, Manly and Cicchetti (1993) provided an important contribution to the literature on child maltreatment through their taxonomy and detailed multidimensional coding system, making explicit that neglect is a heterogeneous phenomenon. This heterogeneity of neglect led some researchers to differentiate distinct types of neglect (e.g., physical, emotional, medical, supervisory, nutritional, educational, and environmental) and to consider a continuum of neglect ranging from optimal to grossly inadequate care (Dubowitz et al., 2005). Others consider it a single construct (Slack, Holl, Altenbernd, McDaniel, & Stevens, 2003). Child Protective Services workers treat childhood neglect as categorical (child neglect did or did not occur). Others believe that it is important to examine characteristics of the neglect experience, focusing on chronicity, duration, frequency and severity of the experience (Dubowitz, Black, Starr, & Zuravin, 1993; English, Bangdiwala, & Runyan, 2005). And, although some have argued that neglect requires the deliberate or “extraordinary inattentiveness” of the parent or caregiver (Polansky, Hally, & Polansky, 1975), others believe that the proper focus should be on the needs of the child without assigning responsibility and regardless of cause (Dubowitz et al., 1993). In sum, there remains considerable controversy about the specifics of defining and identifying child neglect.

Research has shown that neglected children are at increased risk for negative consequences in adolescence and adulthood (Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, & Janson, 2009), including worse cognitive and academic skills (Eckenrode, Laird, & Doris, 1993; Perez & Widom, 1994) and economic well-being (Currie & Widom, 2010), higher rates of mental health problems and psychiatric symptoms (Herrenkohl, Hong, Klika, Herrenkohl, & Russo, 2013; Johnson, Cohen, Brown, Smailes, & Bernstein, 1999; Johnson, Smailes, Cohen, Brown, & Bernstein, 2000; Widom, 1999; Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007; M. O. Wright, Crawford, & Del Castillo, 2009), physical health problems (Norman et al., 2012; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, 2012) and delinquency, crime, and violence (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Smith & Thornberry, 1995). However, despite calls for more research on child neglect (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council, 2014; National Research Council, 1993), child neglect continues to be an understudied type of child maltreatment (Stoltenborgh, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van Ijzendoorn, 2013). With the increasing evidence of the long-term impact of childhood neglect, there is also increased recognition of the need to be able to retrospectively identify children who have been neglected. Because there is no single “gold standard” for the identification of neglect and because there is typically no documentation or official records of the neglect, researchers often need to rely on responses to survey questions to assess neglect and clinicians need to rely on clients’ retrospective recollections.

Few assessment measures have focused specifically on neglect. Bernstein et al. (1994) included items for physical and emotional neglect in a widely used measure to assess child maltreatment. Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, and Runyan (1998) included five questions about childhood neglect as a supplement to the Conflict Tactics Scale. In a study of parenting practices, Zuravin and Fontanella (1999) developed a 5-item scale for physical neglect. More recently, there have been three studies of the prevalence of child maltreatment conducted at the national level (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005; Finkelhor, Turner, Shattuck, & Hamby, 2015; Finkelhor, Vanderminden, Turner, Hamby, & Shattuck, 2014) that have used different approaches to the measurement of neglect. In the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence (NatSCEV) studies, researchers used random digit dialing to conduct a national survey to estimate the incidence of neglect (past year and lifetime) with children ages 10-17 and parents as proxies for children under age 10. The criteria for neglect was whether the respondent endorsed any of six items: general neglect, neglect related to parents drug and alcohol use, being left alone, adults in the home the child was afraid of, unsafe home environment, or cleanliness/hygiene of child. Neglect was reported for 4.7% of the children in the past year and 11.6% over the lifetime.

A very different approach was adopted in the Longitudinal Studies of Child Abuse and Neglect (LONGSCAN), a multisite, longitudinal study exploring the antecedents and consequences of child maltreatment over time (Runyan et al., 1998). LONGSCAN began with children at 4 years of age or younger and has followed them at regularly scheduled intervals (ages 4, 6, 8, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20). Maltreatment reports were coded using three different methods: (1) a modified version of the Maltreatment Classification Scheme developed by Barnett et al. (1993); (2) the maltreatment classification scheme utilized in The National Incident Study (NIS-2), developed by Sedlak (1991); and (3) Child Protective Services (CPS) classification as assigned by the State CPS system. English et al. (2005) described similarities and differences between the CPS reports and research definitions and compared the ability of each of these three ways of classifying a child’s maltreatment experience to predict child outcomes.

Estimating the prevalence and incidence of childhood neglect has been challenging. In a recent review of measures of child maltreatment, Mathews et al. (2020) found that measurement instruments used in studies of neglect rarely included a clear operationalization, varied in the breadth of coverage from broad to very narrow and specific, sometimes included as few as one question but more often between five and 11 questions, often obtained data using proxies for children under 10 years old, and often did not report psychometric data. For all these reasons, the development of a validated instrument to retrospectively ascertain neglect would be highly useful and represent an important contribution to the existing body of measures.

Several additional challenges have hindered the development of a validated neglect instrument. First, the most common psychometric information provided about neglect instruments is internal consistency (Bernstein, Ahluvalia, Pogge, & Handelsman, 1997; Bernstein et al., 1994; Bifulco, Bernazzani, Moran, & Jacobs, 2005; Grassi-Oliveira et al., 2014; Higgins & McCabe, 2001; Scher, Stein, Asmundson, McCreary, & Forde, 2001; Thombs, Bernstein, Lobbestael, & Arntz, 2009; K. D. Wright et al., 2001; Zolotor et al., 2009). Although it has been argued that internal consistency is necessary to provide evidence of the validity of a neglect measure as representing a cohesive type of child maltreatment, as noted above, neglect takes many forms, such as nutritional or medical insecurity or failure to protect a child (Barnett et al., 1993; English et al., 2005). Thus, a comprehensive assessment of childhood neglect might suffer from low internal consistency because components of neglect may not represent one internally consistent construct.

A second problem is related to the difficulty of obtaining samples of children who were neglected or adults who had known histories of neglect against whom one can compare self-report measures. This challenge makes it difficult to test the construct validity of instruments and has led some researchers to validate measures by using people who are expected to have histories of neglect (e.g., patients undergoing treatment for drug or alcohol problems). If these samples score high on the neglect measure, then it is assumed that this provides evidence of construct validity.

Third, recollections and reporting of childhood neglect have been considered unreliable (Baldwin, Reuben, Newbury, & Danese, 2019; Hardt & Rutter, 2004). This could be the result of inefficient encoding of episodic memory of events during childhood (Thorne, 2000) or difficulty to access those memories later in life (Rubin, Rahhal, & Poon, 1998). It is also possible that adults do not have memories of their early neglect experiences, particularly if they were very young at the time. This is important because long-term consequences may depend on the person’s awareness or memory of their earlier childhood experiences.

Victims of childhood neglect might not report (false negatives), perhaps because autobiographical memories of childhood neglect are detrimental to the person’s self-image and hurtful to recall and to report. Researchers have reported high levels of insecure attachments in maltreated children (Baer & Martinez, 2006; Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, 2006; see Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2010 for a meta-analysis). Dismissing individuals may not recall negative experiences from childhood (including neglect) in order to distance themselves from the negative emotions associated with those experiences.

In an attempt to identify false negatives in reports, Bernstein and colleagues (1994; 2003) introduced a three-item scale on the CTQ that was intended to measure minimization-denial and included statements about having experienced a perfect childhood and coming from a perfect family. Bernstein and Fink (1998) argued that strong agreement with any of those items might indicate false negative reporting. This was an important advance, but the minimization-denial scale is widely ignored in studies using the instrument (MacDonald et al., 2016). Another way to address this issue is to treat non-responses as meaningful information, rather than statistical noise.

Fourth, existing neglect measures are based on additive models, in which each item is considered separately and the sum of indicators for neglect is used to reflect the overall childhood experience. However, the seriousness of neglect might not be best represented by the simple sum of different types of neglect experienced, but rather by specific combinations. Scoring of neglect items typically assumes that responses are linked in a linear way, that is, the higher the reported frequency, the more severe the neglect experienced. Although this assumption is likely in many cases, some types of neglect might not follow this pattern. For example, when reporting on the frequency of doctor visitations during childhood, frequent visitations might be as indicative as never visiting a doctor, although both reports would be at opposite ends of the scale.

Fifth, developing a retrospective measure to assess neglect is also challenging because it is likely that if a child had experienced neglect serious enough to come to the attention of authorities, he/she would have a high likelihood of being removed from the home for at least some period of time. Neglect measures do not necessarily ask participants specifically about the time period the child lived with the parent and which parent. This is important information in grounding questions about who did what to whom and when.

Purpose

This paper describes a new instrument designed to retrospectively report childhood neglect and provides evidence of its predictive, discriminant, and construct validity. There are several advantages to the current study. The new instrument was developed using machine learning techniques and uses non-linear methods to maximize predictive validity and power to determine an optimal subset of items. The original set of included items reflected a wide array of neglect experiences that were behaviorally specific. Non-responses were coded and treated as relevant information that may reflect a desire to avoid reporting about one’s childhood experiences. We compared adults with documented histories of childhood neglect to a matched control group of individuals without neglect histories. Recollections were assessed in middle adulthood approximately 30 years after their childhood experiences. The assessments of retrospective reports of childhood neglect were undertaken with a relatively large non-clinical sample that includes both men and women and Blacks and Whites.

In addition to tests of predictive validity, we examined construct and discriminant validity. Childhood neglect has been shown to predict arrests for violent criminal behavior in adulthood (Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989b). To test for construct validity, we predicted that retrospective self-reports of neglect should also significantly predict risk of arrest for a violent crime. That is, individuals who self-report childhood neglect using retrospective measures should have higher rates of arrest for violence than individuals who do not self-report neglect. To test for discriminant validity, we examined whether the new measure would perform better in individuals with documented histories of childhood neglect compared to individuals with documented histories of childhood physical and sexual abuse. A measure with adequate discriminant validity is expected to have higher predictive power indicating neglect than indicating histories of sexual or physical abuse.

Methods

Participants

The data used here are from a large research project based on a prospective cohort design study in which abused and/or neglected children were matched with non-abused and non-neglected children and followed prospectively into adulthood. This study was begun in 1986 using archival records to define both child abuse and neglect and control groups in order to examine the extent to which these children had arrests for delinquency, crime, and violence — the “cycle of violence” (Widom, 1989c). The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court-substantiated cases were included. Cases were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971. To avoid potential problems with ambiguity in the direction of causality, and to ensure that temporal sequence was clear (that is, child neglect or abuse led to subsequent outcomes), neglect and abuse cases were restricted to those in which children were less than 12 years of age at the time of the abuse or neglect incident. Thus, these are cases of early childhood abuse and/or neglect. These design characteristics represent major strengths, but they also pose limitations about the generalizability of the findings.

A critical component of the design is the inclusion of a control group of children who did not have documented cases of abuse and/or neglect and who were matched on the basis of sex, age, race, and approximate family socio-economic status during the time period under study (1967 through 1971). Matching for social class is important because it is theoretically plausible that any relationship between child abuse or neglect and later outcomes is confounded or explained by social class differences (MacMillan et al., 2001; Widom, 1989a). It was difficult to match exactly for social class because higher income families could have lived in lower social class neighborhoods and vice versa. The matching procedure used here for socio-economic status was based on a broad definition of social class that includes neighborhoods in which children were reared and schools they attended. When random sampling is not possible, Shadish, Cook, and Campbell (2002) recommended using neighborhood and hospital controls to match on variables that are related to outcomes. Similar procedures, with neighborhood school matches as approximations of social class, have been used in studies of people with schizophrenia (Watt, 1972).

Children who were under school age at the time of the abuse and/or neglect were matched with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 1 week), and hospital of birth using county birth record information. For children of school age, records of more than 100 elementary schools for the same time period were used to find matches with children of the same sex, race, date of birth (+/− 6 months), class in elementary school during the years 1967 through 1971, and approximate home address. Overall, there were matches for 74% of the abused and neglected children.

The cohort design is based on the assumption that the major difference between the abused and neglected and comparison group is in the abuse or neglect experience. Since it is not possible to randomly assign subjects to groups, equivalency for the groups is approximated. Official records were checked and any candidate comparison group child who had an official record of abuse or neglect in their childhood (n = 11) was eliminated and a second matched subject was assigned to the comparison group to replace the individual excluded. Thus, the control group does not contain any known cases of child abuse or neglect. The number of participants in the comparison group who were actually abused or neglected, but not reported, is unknown. The control group may also differ from the abused and neglected individuals on other variables associated with abuse or neglect. [Further details of the study design and subject selection criteria are available in Widom (1989a)].

In the initial phase of the study, the abused and neglected and matched control children were compared on juvenile and adult criminal arrest records (Widom, 1989c). A second phase involved locating and interviewing both groups during 1989-1995, approximately 22 years after the abuse or neglect (N = 1196). Subsequent follow-up interviews were conducted in 2000-2002 (N = 896) and again in 2003-2005 (N = 806). Although there was attrition associated with death, refusals, and inability to locate individuals over the various waves of the study, the composition of the sample at the four time points has remained about the same. There were no significant differences across the samples on these variables or in mean age across the phases of the study.

The data for the current study are based on individuals (N = 719) who completed the third interview (2003-2005). Participants were 370 individuals with documented histories of childhood neglect and 349 matched controls; mean age 41.1 (SD = 3.54, range = 32-49) at the time of the interview; 51% female; and 59% White, non-Hispanic. Black, non-Hispanic individuals represented the second-largest group (35.0%) and American Indians and participants of Hispanic origin were a small minority.

Procedures

Respondents were interviewed in person, usually in their homes, or, if the respondent preferred, another place appropriate for the interview. The interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study, to the inclusion of an abused and/or neglected group, and to the participants’ group membership. Similarly, the subjects were blind to the purpose of the study. Subjects were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals who grew up in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for the procedures involved in this study and subjects who participated signed a consent form acknowledging that they understood the conditions of their participation and that they were participating voluntarily. For those individuals with limited reading ability, the consent form was read to the person and, if necessary, explained verbally.

Variables and Measures

Official reports of neglect.

Documented cases of childhood neglect were based on examination of court records processed during the years 1967 to 1971 in a metropolitan county area in the Midwest part of the United States. Children were ages 0-11 at the time of the neglect experience. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents’ deficiencies in childcare were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time and represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children. In this study, having a documented history of neglect was coded as a binary variable.

Self-report of neglect.

In order to ensure the breadth and completeness of the measure, a pool of 70 items (questions about medical care, food, clothing, hygiene, housing, supervision, education, and emotional neglect) was compiled, based on the earlier work of Cicchetti and Barnett (1991), Zuravin and Fontanella (1999), Straus et al. (1998), Bernstein et al. (1994), and Sternberg et al. (1999) with additional items based on recommendations from child neglect expert consultants. The questionnaire was designed with particular awareness of the potential difficulty of obtaining information from subjects about sensitive topics. The goal was to achieve a balance between sensitivity on the part of the interviewer to elicit highly personal and potentially upsetting information and not being perceived as “leading” the subject into reporting perhaps questionable reminiscences.

In addition, we knew that many of the participants had only lived with a biological parent for a short period of time and, thus, might not be able to recall these experiences. Indeed, 81% of the neglected children in our study had been placed out of the home at some point in their childhoods. To address this concern, participants were first asked to identify the “person with whom they had lived when they were a child” to determine whether the child had lived with one, both, or neither of their parents. After establishing the identity of the person with whom they had lived, participants were then asked to report whether, and how often, they had experienced any of 70 examples of potential neglect in a typical year before the age of 12 (see Appendix A for the complete 71 item questionnaire).

Arrests for violence.

As a test of construct validity, we drew on the earlier literatures which showed that very young neglected children demonstrated higher rates of physical aggression than other children (Bousha & Twentyman, 1984) and studies showing that children with histories of neglect were at increased risk of arrest for a violent crime (English, Widom, & Brandford, 2002; Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989b; Zingraff, Leiter, Myers, & Johnsen, 1993). We used arrest records, rather than self-reports, because arrest records are widely used (Maxfield & Babbie, 2015), are relatively easy to locate, and it has been argued that more serious offenses are efficiently revealed with fairly little bias by some official data (Hindelang, Hirschi, & Weis, 1979; Maxfield, Weiler, & Widom, 2000). Information about violent arrests was based on official criminal histories collected for these individuals from three levels of law enforcement (local, state, and federal) in 1987-1988 and 1994. Violent criminal behavior included arrests for murder/attempted murder, manslaughter/involuntary manslaughter, reckless homicide, rape, sodomy, robbery/robbery with injury, assault, assault and battery, aggravated assault, and battery/battery with injury. For the purposes of construct validation, we used a dichotomous variable representing whether the person had any arrest for violence (yes =1; no = 0).

Childhood physical and sexual abuse.

To determine whether the new neglect instrument has discriminant validity, we used responses from individuals with documented cases of physical and sexual abuse from the same study and original sample (Widom, 1989a). Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, abrasions, lacerations, wounds, cuts, and bone and skull fractures. Sexual abuse cases included felony sexual assault, fondling or touching, rape, sodomy, and incest.

Analytic strategy

Item selection

Assuming some of the items reported by the participants would not be useful in differentiating between individuals with documented histories of neglect and controls, an optimal subset of items was first identified using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm. SVM is a classifying machine learning algorithm, designed to differentiate between categories by “training” the algorithm on a dataset using a known classification in order to develop a classifier that can be implemented on other data for which true classification is unknown (Hastie, Tibshirani, & Friedman, 2009). SVM approaches this computational problem by representing the data as a multi-dimensional space and calculating propensity of each item to belong to the neglect group based on the characteristics of borderline cases. The calculated score is designed to provide the most accurate separation between neglect and control participants. Machine learning algorithms generally require very large data sets, which are very difficult to collect in the context of child maltreatment. Yet, since SVM is not affected by cases that can be categorized with certainty, and since most cases in a group are not borderline, SVM is robust even when the data set includes only several hundreds of data points. To address the problem of nonlinearity of the effect of frequencies and possible importance of combinations of responses in identifying history of childhood neglect, we used a radial kernel, which yields a “region” of combinations of responses that identifies neglect, rather than a plane that would be the outcome of a linear SVM or logistic regression. One of the parameters of the SVM allows for errors of classification, if complete spatial separation of the classes is impossible. This cost parameter controls the tradeoff between classification errors and generalizability of the outcome. Tuning parameters that control the shape and the separation-error tradeoff were found using a grid search method (Hsu, Chang, & Lin, 2003). The parameters found to produce the best fit according to the cross-validated aggregate measure of the k-fold method were used to find the optimal SVM model.

Several issues with SVM computation were tackled in this study. First, since our goal was to identify a subset of items that most accurately identifies cases with a documented history of childhood neglect, the tuning parameters were also tested and the data was fitted with dozens of optional models. Choosing the best model between that many can result in severe overfitting that will not be generalizable in a new dataset (Varma & Simon, 2006). To avoid overfitting, we applied two separate cross-validation techniques, that in conjunction can remove this bias in model selection (Krstajic, Butorovic, Leahy, & Thomas, 2014). First, to avoid overconfidence in the results, a fifth of the cases was randomly selected, and was excluded from training the SVM classifier and was used only for testing the resulting model. Thus, model selection is not reliant on the test data, and predictive validity can be assessed without bias (Cawley & Talbot, 2010). Since model selection itself could also suffer from overfitting bias, accuracy of the models was compared using k-fold cross-validation.

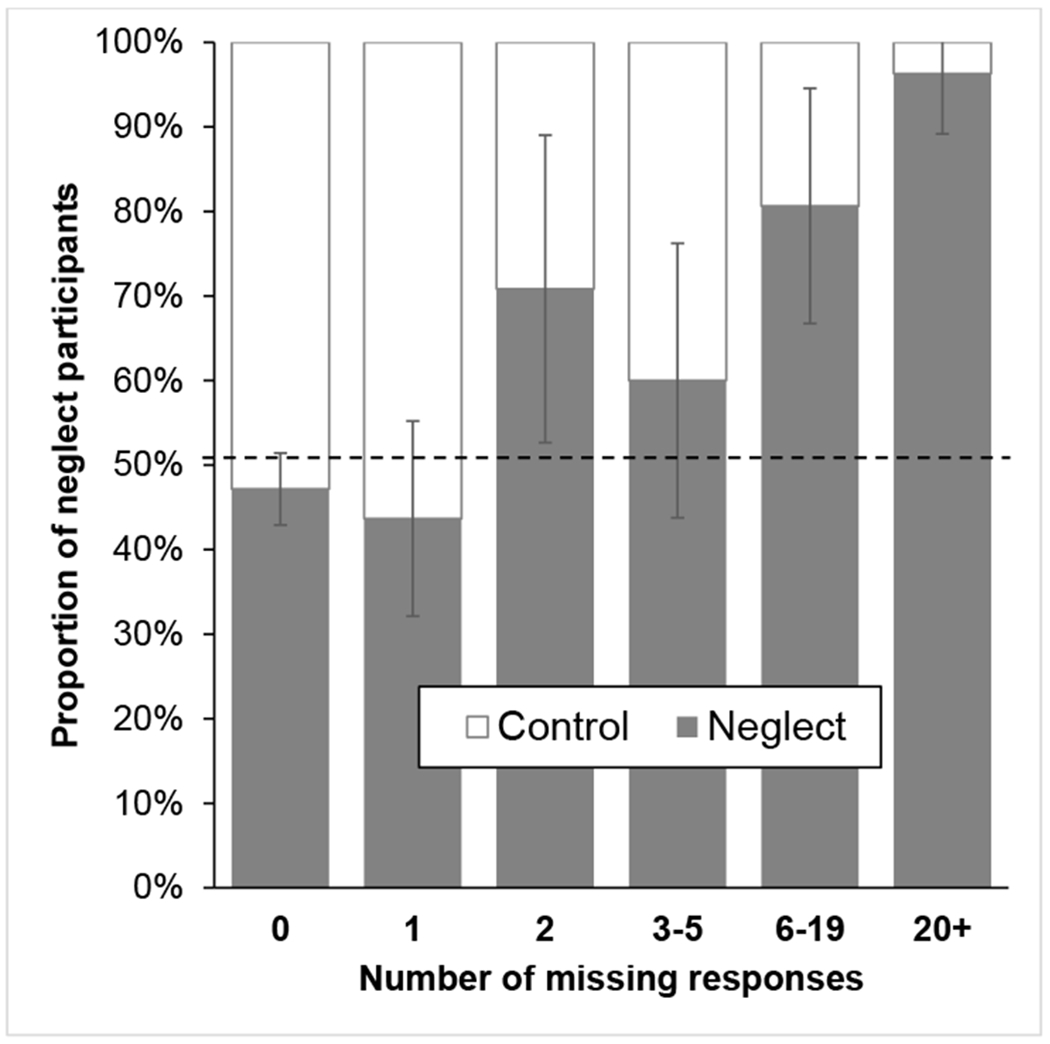

Similar to regression models, SVM requires no missing data. While almost three-quarters (73.7%) of the participants responded to all questions, the remainder did not. Participants did not respond to 2.83 items on average (SD = 10.9), with 13 participants reporting only with which parent they grew up with, and not answering any of the other 70 items (see Figure 1). To address this issue, the missing responses were encoded using item-specific binary indicators, in which missing responses of each participant to each item were tagged. After encoding missing responses separately from response encoding, each missing response was imputed by randomly selecting a valid response for the same item of another participant. This random selection prevented bias to the distribution of responses. Additionally, since imputation was independent of responses to other items, artificial correlations between items were not introduced, albeit random error was thus increased. The number of missing responses was also introduced as an additional indicator of childhood neglect.

Figure 1:

Percentage of neglect participants with missing responses. Dashed line represents the 51.4% of the sample with a documented history of neglect. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Categories of 3-5, 6-19 and 20+ represent missing responses grouped together due to low number of cases.

In order to find the most accurate combination of items, accuracy of all combinations has to be assessed using k-folds cross-validation method. Since there were 71 items in the original full questionnaire, fitting a classifier for all possible subsets was computationally infeasible. To approximate an optimal subset, nested subsets were used in two distinct processes: in the first stage of the introductive process, a classifier was fitted for each item individually, and the item producing the most accurate classifier was selected. Next, each of the remaining items was added to the item selected first. The two-item combination that was most accurate in classifying neglect and control was selected. The next best item yet to be selected was introduced to the subset in every subsequent iteration. Each item was introduced with its corresponding missing response indicator. Introduction of items was exhausted with the inclusion of all items. Next, a similar reductive iterative process was conducted. It started with all items included, and in each iteration the item which least benefited the model was excluded. The reduction process was exhausted when only one item remained selected. The test results of all iterations of both the introductive and reductive processes were compared for accuracy of classification of the test data.

Three measurements were tested in this study to reflect a history of childhood neglect, reflecting severity, diversity and propensity of neglect. According to the rationale underlying the scoring of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), the frequency of experiences of neglect of any kind reflects the severity of the neglect in the child’s life (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). Following this rationale, our severity scale was calculated as the mean of frequency ratings. Harm caused by maltreatment has also been associated with the number of different types of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), where the ACEs score is the number of items reported to have been experienced in childhood (Felitti et al., 1998). Following a similar rationale, we constructed the diversity scale, which is the percentage of items rated higher than “never or almost never” across all items. Since both severity and diversity scales used in other instruments are not sensitive to missing responses, in this study both scales were calculated based on the original data without imputation. Finally, the SVM algorithm produces a propensity score, which is used for classification and was used as the third measure of neglect.

Testing validity

Predictive validity was determined through comparison of the extent to which the measure differentiated between the neglect and control groups. Classification criteria for the severity and diversity scales were calculated using a logistic regression with the scale score predicting neglect using the training dataset only. Sensitivity and specificity of each measure were calculated using their receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Statistical comparisons between ROCs were done comparing area under the ROC curves (AUC) using Delong’s test (DeLong, DeLong, & Clarke-Pearson, 1988; Sun & Xu, 2014). The ROC curves were tested for significance of classification by comparison to a random classifier. The R package pROC (Robin et al., 2011) was used for these analyses. The points on the ROC closest to the ideal classification defined the indicators of optimal sensitivity and specificity for each measure.

To test for discriminant validity, ROCs of neglect, physical abuse, and sexual abuse were compared. It was expected that a scale with good discriminant validity should be significantly more sensitive to neglect than to abuse. Accordingly, the three scales were tested for discriminant validity individually.

Last, construct validity was assessed by the extent to which each measure predicted risk for arrests for violence in adulthood. Childhood neglect was previously found to be a risk factor for adult violence (English et al., 2002; Maxfield & Widom, 1996; Widom, 1989b). Thus, if the measure has construct validity, it should also predict increased risk for violence. Testing was conducted with logistic regressions, where each of the measures calculated was the predictor and any arrest for a violent crime was the dependent variable. Sex, age at the time of data collection, and race of the participants were included as control variables, since these factors are known to affect risk of being arrested for a violent crime.

Results

Item selection

Two iterative processes were used independently: an introductive process, in which items were subsequently added to the machine learning model, and a reductive process, in which all items were included at first, and were removed from the model one by one. The outcome classifier of both iterations of the SVM algorithm achieved relatively similar error rates overall. The model producing minimal error rates included 10 questions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Final retrospective neglect self-report items identified by machine learning techniques

| Both your natural mother and father | Your natural mother only | Your natural father only | Other, neither your natural mother nor father | Don’t remember | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. With whom did you live when you were born? | |||||||

| Number of Days in a Typical Year | |||||||

| In a typical year, living with your PARENT… | Never or almost never | 1-2 days a year | 1-2 days a month | 1-2 days a week | 3-5 days a week | Every day or almost every day | Don’t know |

| 2. How many days did you have trouble with your teeth? | |||||||

| 3. How many days did someone make sure you took a bath or shower? | |||||||

| 4. How many days did you have lice? | |||||||

| 5. How many days did the place where you lived usually have moldy or spoiled food? | |||||||

| 6. How many days did the place where you lived usually have broken windows that weren’t fixed right away? | |||||||

| 7. How many days were you home alone when someone gave you a plan for what to do in an emergency? | |||||||

| 8. How many days were you home alone when you were not sure if your parent would come home at all? | |||||||

| 9. How many days were you home alone without an adult present (by adult we mean a teenager or older person)? | |||||||

| 10. How many days did you feel your parent cared about you? | |||||||

Predictive validity

Table 2 shows the results of mean scores of neglected and control participants for each scale measured, the area under the ROC curve (AUC), as well as optimal sensitivity and specificity, defined by the point on the ROC closest to ideal classification. The mean severity scale was significantly higher in the neglect group compared to the controls (0.66 vs. 0.38 for neglect and control, respectively, t(589)=6.56, p<0001), but testing the area under curve (AUC) indicated that the severity scale was not significantly more predictive of neglect than random (AUC=52.9%, D(140)=0.588, p=0.55). The severity scale achieved only 47.1% sensitivity and 56.2% specificity.

Table 2.

Predictive validity of the three neglect scores

| Mean score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity | Neglect | Control | p-value |

| Severity | 52.9% | 47.1% | 56.2% | 0.66 | 0.38 | <0.0001 |

| Diversity | 64.2% | 50.9% | 79.1% | 64.6% | 34.1% | <0.0001 |

| Propensity | 70.9% | 63.4% | 76.7% | -- | -- | -- |

Note. AUC = area under the ROC curve.

The diversity scale performed better than the severity scale, with significantly higher means for the neglect group compared to the controls (64.6% vs. 34.1%, respectively, t(678)=8.60, p<0001). It was found to be a significantly better predictor of neglect than random (AUC=64.2%, D(140)=3.01, p=.003), and reached 50.9% sensitivity and 79.1% specificity.

However, the propensity scale showed the highest area under the ROC curve, which was significantly higher than chance (AUC=70.9%, D(140)=4.82, p<0001), reaching 63.4% sensitivity and 76.7% specificity.

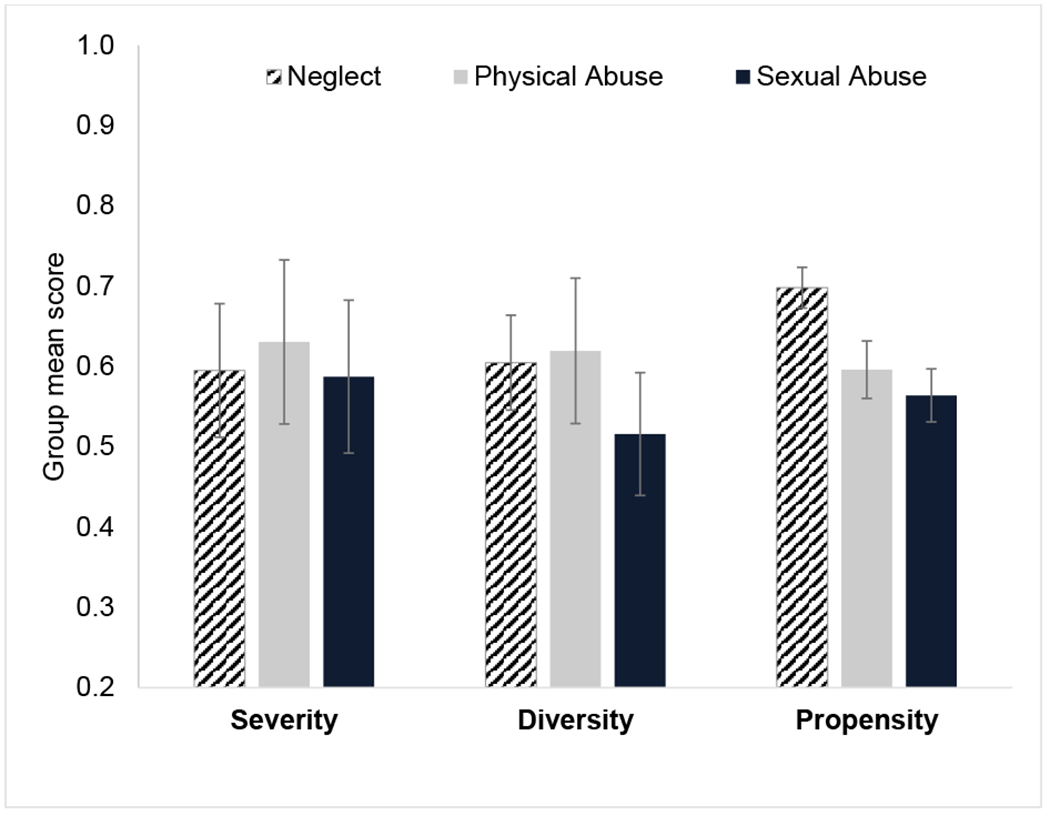

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity was assessed by determining how well each scale predicted neglect compared to how well each scale predicted physical and sexual abuse. For that purpose, the three neglect measures (severity, diversity, and propensity) were calculated for participants who had documented histories of either physical or sexual abuse in childhood but no known history of childhood neglect (see Figure 2). Area under curve and comparisons between ROC of neglect and physical and sexual abuse are presented in Table 3. Comparing the ROC curves for identifying neglect and abuse, only the propensity scale predicted neglect better than both physical and sexual abuse (D(484)=1.94, p=.026, and D(364)=2.13, p=.017 compared to physical and sexual abuse, respectively).

Figure 2:

Mean scores on the three scales for individuals with documented cases of neglect, physical abuse and sexual abuse. Error bars denote confidence intervals for the mean scores.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity: Area under curve (AUC) values for the scale scores predicting neglect, physical abuse and sexual abuse

| Neglect |

Physical Abuse |

Sexual Abuse |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | AUC | AUC | p | AUC | p |

| Propensity | 70.9% | 59.0% | 0.03 | 59.0% | 0.02 |

| Severity | 52.9% | 60.2% | 0.23 | 57.1% | 0.50 |

| Diversity | 64.2% | 59.8% | 0.45 | 56.5% | 0.20 |

Note: P values denote significance of pairwise comparisons between neglect and the other types of maltreatment and were calculated using DeLong et al.’s (1988) method.

Both simpler scales of neglect did not present adequate discriminant validity. The severity scale was found to be not significantly worse in identifying neglect than sexual abuse (D(315)=−0.68, p=.50) and in identifying physical abuse (D(305)=−1.20, p=.23). The diversity scale performed better than the severity scale, but was not significantly better at identifying neglect compared to sexual abuse (D(334)=1.29, p=.20) or physical abuse (D(322)=0.75, p=.45). In summary, the propensity scale was the only scale showing high discriminant validity.

Construct validity

A test of construct validity was conducted by examining whether the severity, diversity or propensity scores predicted risk of being arrested for violence – an objective observation that is known to relate to a history of childhood neglect. For this purpose, a series of logistic regressions evaluating the extent to which the neglect scale scores predict arrest for violence were computed, including control variables. As can be seen in Table 4, the propensity scale was the only significant predictor of arrest for violence (AOR = 2.46, CI = 1.05-5.88, p =.042). The severity and diversity scales did not predict arrest for violence (severity: AOR= 0.96, CI = 0.59-1.54, p=.85; diversity: AOR = 1.35, CI= 0.92-1.98, p=. 122).

Table 4.

Construct validity: Neglect scores predicting any arrest for violence

| Severity score |

Diversity score |

Propensity score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95 % CI) | p | AOR (95 % CI) | p | AOR (95 % CI) | p | |

| Neglect | 0.96 (0.59–1.54) | 0.854 | 1.35 (0.92–1.98) | 0.122 | 2.48 (1.05–5.88) | 0.039 |

| Sex | 0.17 (0.11–0.25) | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.11–0.26) | <0.001 | 0.17 (0.11–0.26) | <0.001 |

| Race | 0.28 (0.19–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.29 (0.19–0.42) | <0.001 | 0.27 (0.19–0.40) | <0.001 |

| Age at interview | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 0.293 | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | 0.276 | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | 0.302 |

Notes. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence. Sex = females compared to males. Race = non-Hispanic Whites compared to all others.

(AOR = 2.46, CI = 1.055.88, p = .042). The severity and diversity scales did not predict arrest for violence (severity: AOR = 0.96, CI= 0.59–1.54, p = .85; diversity: AOR = 1.35, CI = 0.92–1.98, p = .122).

Discussion

This research was undertaken to fill a major gap in the existing literature on childhood neglect by developing and validating a new instrument to retrospectively detect childhood neglect. To overcome one of the challenges of prior work, these findings are based on information from a large group of adults who had documented histories of neglect in childhood. In addition, these previously neglected children had been matched with children with similar demographic characteristics in childhood but without neglect histories. Both groups were interviewed in 2003-2005 and asked to retrospectively report about their childhood experiences.

Using machine learning techniques to identify a subset of items from a much larger initial pool, the results showed that the propensity scale scores for the 10 items selected through this machine learning technique had predictive validity and were significantly better at identifying neglect than either physical and sexual abuse (discriminant validity). As with any other machine learning algorithm, the approach used here was data-driven rather than theory-driven in selecting and weighting items. Neglect includes many different types of experiences that do not necessarily co-occur (Barnett et al., 1993). The 10 items selected for inclusion here appear to cover many dimensions, but not all possible dimensions. Medical neglect is represented by items that referred to dental problems and lacking hygiene; nutritional neglect is represented by the occurrence of untreated food spoilage; and lacking shelter is represented by failure to fix broken windows. Failure in guardianship is the most prominent aspect of neglect in the instrument, reflected in several items that represented versions of being left home alone.

This 10-item instrument has potential usefulness in both clinical and research settings. It is well established that substantiated cases constitute an underestimation of the prevalence of neglect. By identifying adults who suffered severe neglect but were not identified and treated at the time, this new instrument may help uncover clinical information that may have implications for treatment. Since the instrument is short, it is easy to implement in a clinical setting, although scoring is not easily done by hand due to the nature of the machine learning algorithm used. By identifying neglected children who were not earlier identified and treated, this new instrument may permit the identification of a research population that will permit future research on whether and how childhood neglect influences clinical outcomes.

A significant innovation in the new instrument is the introduction of non-responses that are useful and relevant in improving predictive power. Using the number of missing responses in estimating the propensity of a history of childhood neglect was found to improve the accuracy of the instrument. Although including missing responses or refusals has been considered good practice for avoiding bias (Mokkink et al., 2010), non-response has been seldom used as indicative of neglect. Having to recall information about past childhood trauma can be painful, and some victims might avoid responding to descriptions of their childhood experiences, or feel compelled to deny their experiences and provide a false report. Non-victims presumably do not have the same difficulty in responding. Indeed, our findings indicate that the controls in this study were significantly less likely to answer with “don’t remember”. These new findings suggest that non-responses should be treated as an important source of information, not only in clinical work but also as a formal part of retrospective self-reports of childhood neglect.

The tendency to avoid reporting bad memories that are difficult to handle might also shed light on why particular items were included among all the possible options for inclusion. For example, the item that refers to having a problem with a person’s teeth was selected rather than a more direct item reporting how frequently the respondent got medical attention. It is possible that indirect items are easier for recollection and reporting, as they are not as painful to the respondents and are less harmful to their self-perceptions. Neglect is often perceived as rejection and abandonment by the children (Gauthier, Stollak, Messé, & Aronoff, 1996). These self-harming perceptions are likely to develop into an insecure attachment style that may then lead to a greater tendency to avoid responding (more missing information) and provide an indirect (perhaps unobtrusive) measure of neglect. While the implications of these findings may very well have clinical significance, an examination of the role of insecure attachment is beyond the scope of the current study. However, future research might examine convergent validity using information about attachment styles and hypothesize that dismissing/avoidant approaches to relationships might explain the tendency of some people to falsely deny a history of neglect despite their objective autobiographical history.

High-risk populations are of concern for clinical and research purposes. However, it is especially important to design instruments that control for covariates of childhood neglect, such as poverty (Drake & Pandey, 1996; Lefebvre, Fallon, Van Wert, & Filippelli, 2017; Slack, Holl, McDaniel, & Bolger, 2004). Recognizing the importance of this consideration (Widom, 1988), the design of the original study ensured that the controls were matched to the neglected children on the basis of the approximate socio-economic status of their family origin, as well as age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Because the cases were brought to the attention of the courts and thus, represented families and children from lower socio-economic status backgrounds, both groups (neglected and controls) were heavily skewed toward the lower end of the socio-economic spectrum. Prior work with this sample of neglected children followed up into adulthood has shown that childhood neglect and childhood family poverty independently predicted outcomes (Nikulina, Widom, & Czaja, 2011). Although one might consider some of the items included in the new measure to indicate lack of resources and poverty, even without resources it is possible to maintain hygiene and unspoiled food. The items that discriminated between the previously neglected children and controls more likely reflect failures in parenting (i.e., instances of spoiled food not being thrown away, homes in disrepair, and neglect of hygiene and health) and experiences of loneliness and uncertainty, rather than items reflecting objective lack of resources reflecting poverty, such as lack of food and clothing. Nonetheless, since this is the first examination of this set of items, future research needs to further explore the appropriate interpretation of this particular set of items.

Despite the breadth of the items in the original questionnaire, only some aspects (lack of supervision, physical, environmental, and emotional) were included in the final set of items in the SVM-based instrument. It is possible that these characteristics reflected the dominant criteria for attention by child protection workers at the time. However, since this work is based on adults reporting on their childhood experiences, it is also possible that the emphasis on specific aspects of neglect stood out in their minds and were encoded and preserved in their memories.

When probing distant memories of life events during early childhood, forgetting is likely, as memories need more reconstruction at that point, even if these experiences have had a profound impact on a person’s psychological development (Hyman & Loftus, 1998; Rubin et al., 1998). Here, despite the fact that the participants were about 40 years old when they were asked to recall their childhood experiences of neglect, the accuracy of classification, as is evident in the Area Under Curve, was comparable to that of instruments validated with adolescents (Bernstein et al., 1997).

Although predictive, discriminant, and construct validity of the scale were tested, additional testing is needed to establish the scale’s general usefulness. The instrument was constructed using responses of children who had grown up in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the Midwest part of the United States and may raise concerns about applying these findings to the present society. The maltreatment cases studied here are quite similar to current cases being processed by the child protection system and the court. One difference is that the children studied here were not provided with extensive services or treatment options as are available today and, thus, the results of this study represent the natural history of the development of maltreated children whose cases have come to the attention of the courts. In addition, some items might have been affected by the location and time period of the study and might not be as sensitive to childhood neglect in other circumstances and cultures. For example, the item that describes “broken windows not being fixed promptly” might be more discriminating in identifying neglect in the Midwest part of the United States, where the weather can be very cold in the winter, compared to other regions of the world where broken windows may not exist or would not constitute a great danger for children’s health. More testing is required in other locations and populations in order to establish the generalizability of the new instrument.

The context of the administration of the instrument also requires more testing. As the final 10 items were selected from a larger pool of items in a lengthy questionnaire, the subset of items identified here was not administered by itself. Other items were not found to improve classification of childhood neglect, but their presentation might have affected the responses to the subset eventually included. Nonetheless, despite these caveats and the need for further testing, this new instrument to retrospectively identify childhood neglect in adults has many positive qualities that make it worthy of consideration for use by researchers and clinicians.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement:

This research was supported in part by grants to Dr. Widom from NIJ (86-IJ-CX-0033, 89-IJ-CX-0007, and 2011-WG-BX-0013), NIMH (MH49467 and MH58386), Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD (HD40774), NIDA (DA17842 and DA10060), NIAAA (AA09238 and AA11108), NIA (AG058683), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Dr. Carmel’s work was partially supported by a Haruv Institute post-doctoral fellowship grant. The opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the US Department of Justice. We express appreciation for the reviewers’ suggestions to improve an earlier version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baer JC, & Martinez CD (2006). Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 24(3), 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin JR, Reuben A, Newbury JB, & Danese A (2019). Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(6), 584–593. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett D, Manly JT, & Cicchetti D (1993). Defining child maltreatment: The interface between policy and research. In Child abuse, child development, and social policy. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DR, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, & Handelsman L (1997). Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(3), 340–348. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DR, & Fink L (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report: Manual:. Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DR, Fink L, Handelsman L, Foote J, Lovejoy M, Wenzel K, … Ruggiero J (1994). Initial reliability and validity of a new retrospective measure of child abuse and neglect. American Journal of Psychiatry, 757(8), 1132–1136. doi: 10.1176/ajp.l51.8.1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DR, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, … Zule W (2003). Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect, 27(2), 169–190. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco A, Bernazzani O, Moran PM, & Jacobs C (2005). The Childhood Experience of Care and Abuse Questionnaire (CECA.Q): Validation in a community series. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(A), 563–581. doi: 10.1348/014466505X35344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousha DM, & Twentyman CT (1984). Mother-child interactional style in abuse, neglect, and control groups: Naturalistic observations in the home. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 93(1), 106. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.93.1.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawley GC, & Talbot NLC (2010). On over-fitting in model selection and subsequent selection bias in performance evaluation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 77(Jul), 2079–2107. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Barnett D (1991). Attachment organization in maltreated preschoolers. Development and Psychopathology, 5(4), 397–411. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400007598 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, & Toth SL (2006). Fostering secure attachment in infants in maltreating families through preventive interventions. Development and Psychopathology, 73(3), 623–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie I, & Widom CS (2010). Long-term consequences of child abuse and neglect on adult economic well-being. Child Maltreatment, 75(2), 111–120. doi: 10.1177/1077559509355316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr C, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & Van Ijzendoom ΜH (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87–108. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong ER, DeLong DM, & Clarke-Pearson DL (1988). Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics, 44(3), 837–845. doi: 10.2307/2531595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, & Pandey S (1996). Understanding the relationship between neighborhood poverty and specific types of child maltreatment. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20(11), 1003–1018. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00091-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz Η (2006). Defining child neglect In Ferrick M, Knutson J, Trickett P, & Flanzer S (Eds.), Child Abuse and Neglect(pp. 107–127). Baltimore, MD: Brooks. [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Black M, Starr RH, & Zuravin SJ (1993). A conceptual definition of child neglect. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 20(1), 8–26. doi: 10.1177/0093854893020001003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Pitts SC, Litrownik AJ, Cox CE, Runyan D, & Black ΜM (2005). Defining child neglect based on child protective services data. Child Abuse and Neglect, 29(5), 493–511. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckenrode J, Laird M, & Doris J (1993). School performance and disciplinary problems among abused and neglected children. Developmental Psychology, 29(1), 53–62. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.29.1.53 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Bangdiwala SF, & Runyan DK (2005). The dimensions of maltreatment: Introduction. Child Abuse and Neglect, 29(5), 441–460. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Widom CS, & Brandford C (2002). Childhood Victimization and Delincpiency, Adult Criminality, and Violent Criminal Behavior: A Replication and Extension, Final Report. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffilesl/nij/grants/192291.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DE, Spitz AM, Edwards V, … Marks JS. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(A), 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA, & Hamby SL (2005). The victimization of children and youth: A comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment, 10(1), 5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, & Hamby SL (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 769(8), 746–754. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Vanderminden J, Turner H, Hamby S, & Shattuck A (2014). Child maltreatment rates assessed in a national household survey of caregivers and youth. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38(9), 1421–1435. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier L, Stollak G, Messe L, & Aronoff J (1996). Recall of childhood neglect and physical abuse as differential predictors of current psychological functioning. Child Abuse and Neglect, 20(1), 549–559. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(96)00043-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson DW,E, & Janson S (2009). Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet, 373, 68–81. doi: 10.1016/SO140-6736(08)61706-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi-Oliveira R, Cogo-Moreira H, Salum GA, Brietzke E, Viola TW, Manfiro GG, … Arteche AX (2014). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) in Brazilian samples of different age groups: Findings from confirmatory factor analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e87118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardt J, & Rutter M (2004). Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastie T, Tibshirani R, & Friedman J (2009). The elements of statistical learning (2nd ed.):Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TT, Hong S, Klika JB, Herrenkohl RC, & Russo MJ (2013). Developmental impacts of child abuse and neglect related to adult mental health, substance use, and physical health. Journal of Family Violence, 28(2), 191–199. doi: 10.1007/sl0896-012-9474-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins DJ, & McCabe ΜP (2001). The development of the Comprehensive Child Maltreatment Scale. Journal of Family Studies, 7(1), 7–28. doi: 10.5172/jfs.7.1.7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hindelang MJ, Hirschi T, & Weis JG (1979). Correlates of delinquency: The illusion of discrepancy between self-report and official measures. American Sociological Review, 44(6), 999–1014. doi:https://doi.org/l0.2307/2094722 [Google Scholar]

- Hsu C-W, Chang C-C, & Lin C-J (2003). APractical Guide to Support Vector Classification. Retrieved from https://www.csie.ntu.edu.tw/~cjlin/papers/guide/guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hyman IE, & Loftus EF. (1998). Errors in autobiographical memory. Clinical Psychology Review, 18(8), 933–947. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00041-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine and National Research Council (2014). New directions in child abuse and neglect research. National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brown J, Smailes EM, & Bernstein DP (1999). Childhood maltreatment increases risk for personality disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(1), 600–606. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Smailes EM, Cohen P, Brown J, & Bernstein DP (2000). Associations between four types of childhood neglect and personality disorder symptoms during adolescence and early adulthood: Findings of a community-based longitudinal study. Journal of Personality Disorders, 14(2), 171–187. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krstajic D, Butorovic LJ, Leahy DE, & Thomas S (2014). Cross-validation pitfalls when selecting and assessing regression and classification models. Journal of Cheminformatics, 6(1), 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/l0.1186/1758-2946-6-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre R, Fallon B, Van Wert M, & Filippelli J (2017). Examining the relationship between economic hardship and child maltreatment using data from the Ontario Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect-2013 (OIS-2013). Behavioral Sciences, 7(1). doi: 10.3390/bs7010006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K, Thomas ML, Sciolla AE, Schneider B, Pappas K, Bleijenberg G, …Wingenfeld K. (2016). Minimization of childhood maltreatment is common and consequential Results from a large, multinational sample using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 77(1), e0146058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Fleming JE, Streiner DL, Lin E, Boyle ΜH, Jamieson E, … Beardslee WR (2001). Childhood abuse and lifetime psychopathology in a community sample. American Journal of Psychiatry, 755(11), 1878–1883. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.l58.11.1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews B, Pacella RD, Μ P, Simunovic M, & Marston C (2020). Improving measurement of child abuse and neglect: A systematic review and analysis of national prevalence studies. PLoS ONE, 75(1), e0227884. doi: 10.1371/joumal.pone.0227884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, & Babbie ER (2015). Research methods for criminal justice and criminology (7th ed. ed.): Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, Weiler BL, & Widom CS (2000). Comparing self-reports and official records of arrests. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 76(1), 87–110. doi: 10.1023/A:1007577512038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield MG, & Widom CS (1996). The cycle of violence: Revisited 6 years later. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 750(4), 390–395. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290056009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, … de Vet HCW. (2010). The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research, 19(4), 539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. (1993). Understanding child abuse and neglect. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina V, Widom CS, & Czaja S (2011). The role of childhood neglect and childhood poverty in predicting mental health, academic achievement and crime in adulthood. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3–4), 309–321. doi: 10.1007/sl0464-010-9385-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, & Vos T (2012). The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoSMedicine, 9(11), el001349. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CM, & Widom CS (1994). Childhood victimization and long-term intellectual and academic outcomes. Child Abuse and Neglect, 75(8), 617–633. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polansky NA, Hally C, & Polansky NE (1975). Profile of neglect: A survey of the state of knowledge of child neglect. Washington, DC: U.S: Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. [Google Scholar]

- Robin X, Turck N, Hainard A, Tiberti N, Lisacek F, Sanchez J-C, & Muller M (2011). pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinformatics, 12(1), 77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DC, Rahhal TA, & Poon LW (1998). Things learned in early adulthood are remembered best. Memory & Cognition, 26(1), 3–19. doi: 10.3758/BF03211366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan DK, Curtis RA, Hunter WM, Black ΜM, Kotch JB, Bangdiwala S, …Landsverk J (1998). Longscan: A consortium for longitudinal studies of maltreatment and the life course of children. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 5(3), 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Stein ΜB, Asmundson GJG, McCreary DR, & Forde DR (2001). The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in a community sample: Psychometric properties and normative data. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 77(4), 843–857. doi: 10.1023/A:1013058625719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ (1991). National incidence and prevalence of child abuse and neglect: 1998 (revised report). Rockville, MD: Westat. [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, & Campbell DT (2002). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference: Vol. xxi: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Holl J, Altenbernd L, McDaniel M, & Stevens AB (2003). Improving the measurement of child neglect for survey research: Issues and recommendations. Child Maltreatment, 8(2), 98–111. doi: 10.1177/1077559502250827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slack KS, Holl JL, McDaniel ΜY,J, & Bolger K (2004). Understanding the risks of child neglect: An exploration of poverty and parenting characteristics. Child Maltreatment, 9(4), 395–408. doi:https://doi.org/l0.1177/1077559504269193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, & Thornberry TP (1995). The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology, 33(4), 451–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1995.tbO1186.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg KJ, Lamb ΜE, Esplin PW, & Baradaran LP (1999). Using a scripted protocol in investigative interviews: A pilot study. Applied Developmental Science, 3(2), 70–76. doi: 10.1207/sl532480xads0302_l [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, & van Ijzendoorn ΜH (2013). The neglect of child neglect: A meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(3), 345–355. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0549-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Finkelhor D, Moore DW, & Runyan D (1998). Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22(4), 249–270. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, & Xu W (2014). Fast implementation of DeLong’s algorithm for comparing the areas under correlated receiver operating characteristic curves. IEEE Signal Processing Letters, 27(11), 1389–1393. doi: 10.1109/LSP.2014.2337313 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs BD, Bernstein DR, Lobbestael J, & Arntz A (2009). A validation study of the Dutch Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form: Factor structure, reliability, and known-groups validity. Child Abuse and Neglect, 22(8), 518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorne A (2000). Personal memory telling and personality development. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 4(1), 45–56. doi: 10.1207/S15327957PSPR0401_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2019). Child Maltreatment 2017. Retrieved from Washington, DC: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/child-maltreatment-2017 [Google Scholar]

- Varma S, & Simon R (2006). Bias in error estimation when using cross-validation for model selection. BMC Bioinformatics, 7(1), 1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt NF (1972). Longitudinal changes in the social behavior of children hospitalized for schizophrenia as adults. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 755(1), 42–54. doi : 10.1097/00005053-197207000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1988). Sampling biases and implications for child abuse research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 55(2), 260–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1988.tb01587.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1989a). Child abuse, neglect, and adult behavior: Research design and findings on criminality, violence, and child abuse. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 59(3), 355–367. doi: 10.1111/j.l939-0025.1989.tb01671.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1989b). Child abuse, neglect, and violent criminal behavior. Criminology, 27(2), 251–271. doi: 10.1111/j.l745-9125.1989.tb01032.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1989c). The cycle of violence. Science, 244(4901), 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS (1999). Posttraumatic stress disorder in abused and neglected children grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 756(8), 1223–1229. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Czaja S, Bentley T, & Johnson MS (2012). A prospective investigation of physical health outcomes in abused and neglected children: New findings from a 30-year follow-up. American Journal of Public Health, 102(6), 1135–1144. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, DuMont K, & Czaja SJ (2007). A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64( 1), 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KD, Asmundson GJG, McCreary DR, Scher C, Hami S, & Stein ΜB (2001). Factorial validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in men and women. Depression and Anxiety, 13(4), 179–183. doi: 10.1002/da.1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright MO, Crawford E, & Del Castillo D (2009). Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse and Neglect, 55(1), 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zingraff ΜT, Leiter J, Myers KA, & Johnsen MC (1993). Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology, 57(2), 173–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.1993.tbO1127.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotor AJ, Runyan DK, Dunne MR, Jain D, Peturs HR, Ramirez C, … Isaeva O. (2009). ISPCAN Child Abuse Screening Tool Children’s Version (ICAST-C): Instrument development and multi-national pilot testing. Child Abuse and Neglect, 55(11), 833–841. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuravin SJ, & Fontanella C (1999). Parenting behaviors and perceived parenting competence of child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse and Neglect, 23(7), 623–632. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(99)00045-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.